- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Will Minneapolis become the Selma of the North?

- How COVID-19, Floyd protests shape China’s crackdown in Hong Kong

- Life after COVID-19: Recovered New Yorkers find hope in helping others

- When college is online, where do international students go?

- ‘I’m Your Huckleberry’: Val Kilmer’s candid take on Hollywood and healing

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

#ShutDownSTEM: How scientists are joining the BLM fight

On Wednesday, thousands of scientists went on a 24-hour strike to join the Black Lives Matter movement. They stopped their experiments and calculations, canceled classes, and shifted their attention to educating themselves on the inequities perpetuated in STEM and academia. Some major research journals joined in, too, delaying the announcement and publication of papers (with exceptions for COVID-19 research).

“As members of the global academic and STEM communities, we have an enormous ethical obligation to stop doing ‘business as usual,’” says a statement by the organizers of #ShutDownSTEM. “In academia, our thoughts and words turn into new ways of knowing. Our research papers turn into media releases, books and legislation that reinforce anti-Black narratives. In STEM, we create technologies that affect every part of our society and are routinely weaponized against Black people.”

The strike was conceived of and coordinated by a diverse group of largely physicists and astronomers. Non-Black researchers were advised to use the strike day to educate themselves on systemic racism in their fields and institutions, and to draft plans to eliminate inequalities. Many took to social media to amplify the experiences of Black scientists and academics, using a hashtag #BlackintheIvory that began trending June 6.

“It seems like it finally gave people a voice,” Joy Melody Woods, a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, told Wired. Ms. Woods was the first to use the hashtag, which grew out of dialogue with her friend and colleague Shardé Davis. Both are Black women. “People who’ve felt gaslit by their experiences, people who live their working lives in isolation in all-white spaces, finally they had a place where they could see and hear other Black stories. And that’s been really powerful.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Will Minneapolis become the Selma of the North?

Law enforcement violence against peaceful demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 shocked the U.S. and sparked social change. Is George Floyd’s death at the hands of a police officer in Minneapolis a similar inflection point?

Will Minneapolis become the Selma of the North, a city whose tragedy produces important change? That’s what some residents hope as they look to the future.

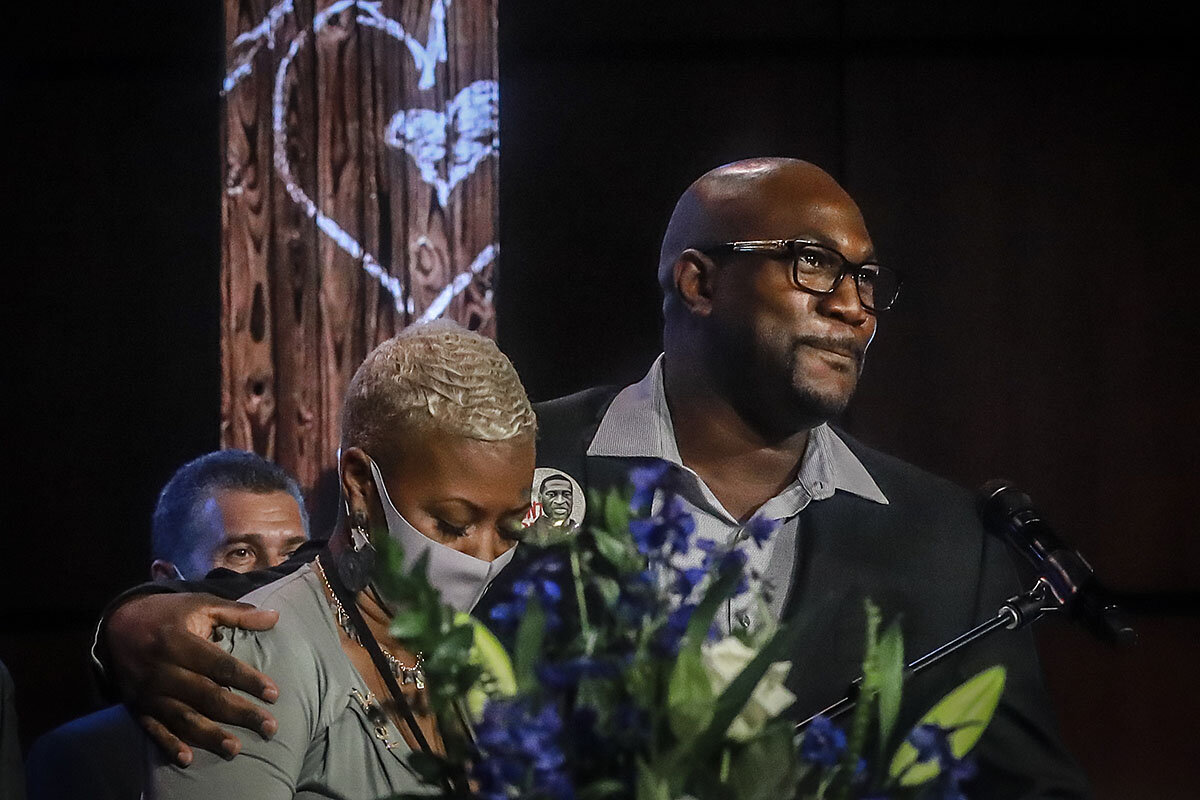

“What we’re seeing is a step forward,” says Martin Rogers, a church elder, as he leaves a private memorial service for George Floyd in Minneapolis on a recent afternoon. “Change takes time, and I’m not sure everybody is ready to change. Black people – we’re ready.”

In 1965, in Selma, Alabama, state troopers and sheriff’s deputies clubbed and tear-gassed peaceful civil rights demonstrators. The attack shocked the nation and prodded Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act.

In 2020, a viral video of Mr. Floyd’s death under the knee of a white police officer in Minneapolis has ignited outrage and massive protests across the nation.

The pressure has already begun to change the city in important ways, as the Minneapolis City Council has voted to replace the police department with a new public safety system.

Will Minneapolis really be the 21st-century Selma?

“I don’t know if we can ever reach that level,” says Cameron Kinghorn, who’s driven into the city to donate essential items. “But I think there’s a chance.”

Will Minneapolis become the Selma of the North?

The private memorial service for George Floyd had ended and Martin Rogers stepped out into the hazy afternoon light. He walked across the street and sat down on an empty park bench, and from that vantage point, he looked back and ahead, to the struggle then and now for racial justice in America.

He recalled a recent trip to Selma, Alabama, with his wife, who grew up there. They visited the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where in 1965 state troopers and sheriff’s deputies armed with tear gas and billy clubs attacked peaceful demonstrators marching in support of voting rights for African Americans. “Bloody Sunday,” as the confrontation became known, marked a seminal moment in the civil rights movement and prodded Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act that year.

“Walking onto that bridge – that was powerful,” says Mr. Rogers, a former grade-school teacher. “You could feel the history of what those marchers achieved.”

A Connecticut native who moved to Minneapolis in the early 1980s, he attended the memorial here for Mr. Floyd last week on behalf of the Christian church where he serves as an elder. He heard the Rev. Al Sharpton deliver a stirring eulogy for Mr. Floyd, the Black security guard who died on Memorial Day under the knee of a white police officer as other officers held him down.

“What happened to Floyd happens every day in this country – in education, in health services, and in every area of American life,” Mr. Sharpton told mourners, his voice rising. “It’s time for us to stand up in George’s name and say, ‘Get your knee off our necks!’”

The viral video of Mr. Floyd’s death ignited outrage and massive protests in Minneapolis that spread across the country, creating a groundswell that could represent the start of the nation’s largest grassroots movement since civil rights and the Vietnam War. The prospect inspires cautious hope among residents that their city might emerge from an uprising born of tragedy as the Selma of the North.

“What we’re seeing is a step forward,” Mr. Rogers says. “Change takes time, and I’m not sure everybody is ready to change. Black people – we’re ready. What we need is for everyone to stay involved and stay passionate.”

A different kind of movement

Civil rights luminaries, religious leaders, and politicians joined Mr. Floyd’s family for the memorial to commemorate his life and call for racial equality. Outside the sanctuary, a sound system carried the words of Mr. Sharpton and other speakers to hundreds of people gathered on the streets and in a nearby park. The demonstrators bore messages of solidarity – “Rest in Power George,” “Black Lives Matter,” “I Can’t Breathe” – on T-shirts, face masks, and cardboard signs.

The deep tensions between people of color and the city’s predominantly white police force exploded after a bystander’s video surfaced of Officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Mr. Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes. Shonda Henderson, who has raised her six children in Minneapolis, warns her two teenage sons to avoid cops whenever possible, a concern rooted in the department’s reputation for abusive behavior.

“I want to see the police violence against us stop and law enforcement start working for us,” says Ms. Henderson, a housekeeper at a downtown hotel. The demographics of the protesters – as much as the number and size of recent rallies – give her reason to think the emotion of the moment could evolve into a sustained movement.

“What’s different this time is I’m seeing everybody out here – Caucasians, Asians, Latinos. It’s not just African Americans,” she says. “We’re all sticking up for each other and realizing that these issues of equality affect every one of us.”

Millennials and Generation Z have supplied much of the energy and momentum behind the demand for racial justice in Minneapolis and elsewhere. Mariana Noyola, who will enter ninth grade this fall, convinced her parents to attend the gathering outside the memorial service.

“It’s scary to be African American in America. We’re looked at differently, we’re seen as dangerous, we feel more threatened,” she says. “Other people feel like our Blackness is some kind of weapon.”

The teenager sounded weary beyond her years as she recited the names of Black men killed by police in Minneapolis and other cities the past few years: Jamar Clark, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, Michael Brown.

“We don’t want this to keep happening,” she says. “So we’re making sure that we’re heard and we’re seen so that our future doesn’t look like the past.”

The looting and destruction of hundreds of businesses hindered the first days of protests. Along Lake Street in South Minneapolis, one of the most racially diverse and hardest-hit stretches in the city, many of the small-business owners are people of color and include immigrants from Somalia, Laos, and an array of other countries.

Marvin Applewhite launched a GoFundMe campaign that raised more than $53,000 to provide cleanup services for businesses in the area. He considers his multicultural, multiethnic team of volunteers reflective of the communal will to remedy racial friction.

“George Floyd’s death has brought people together who I’ve never seen coming together here,” he says. “And now they’re coming together across the country.”

Near the end of his eulogy for Mr. Floyd last week, Mr. Sharpton declaimed, “You changed the world, George. We going to keep marching, George. We going to keep fighting, George.”

Shae Noyola, Mariana’s mother, added a coda intended for the city and country alike. “Don’t want change,” she says. “Make change.”

Grief and catharsis

A shrine has bloomed at the intersection where George Floyd gasped his final breaths outside a corner grocery store. A mural of him adorns one of the shop’s exterior walls, his head encircled by a halo of names of people killed by police. Beneath the painting lies a welter of flower bouquets, handmade placards, photos, and other offerings of anguish, anger, and unity.

Around the corner, marking the spot of his death, a chalk drawing on the pavement shows a human figure with angel’s wings.

Visitors by the hundreds eddied through the site on the day of Mr. Floyd’s memorial as the mood drifted between block party and open-air wake. Smoke from barbecue grills swirled in the air while volunteers served free food and distributed donated goods. A series of speakers and musicians took to a stage erected in the middle of the street. Almost every one of them yelled out to the crowd, “What’s his name?” Each time the reply arrived like cracks of thunder: “George! Floyd!”

Here, at the junction of grief and catharsis, Lorraine Gurley felt at once downcast and uplifted. Thirty years ago, responding to a report of a neighborhood party turned unruly, a white Minneapolis cop fatally shot her unarmed brother in the back.

The case provoked racial animus and local protests. But unlike the four officers involved in Mr. Floyd’s death, the patrolman who killed Tycel Nelson neither faced criminal charges nor lost his job, ascending to the rank of lieutenant over the ensuing two decades.

Ms. Gurley, a pastor at a church on the city’s north side, wonders whether Mr. Floyd would be alive if the city had imposed reforms on the department after her brother’s shooting. She wants the next three decades of policing in Minneapolis and across the country to bear little semblance to the past three.

“There has been so much frustration, so much sorrow, so much loss and death in the Black community. We have to change the system,” she says. A message written in chalk on the pavement behind her read, “Together We Will Change The World.”

“All the things we wish could’ve happened when my baby brother died – that’s what we hope will happen now.”

“Good intentions aren’t enough”

The pressure exerted by the protests has begun to alter city policy. A veto-proof majority of the Minneapolis City Council vowed this week to replace the police department with a new public safety system, and the police chief announced the department’s withdrawal from contract negotiations with the officers union.

At the same time, the demands for reform in Minneapolis and other cities extend beyond revamping law enforcement. The surging movement encompasses a broader desire to redress racial inequality in employment and education, in housing and health care, in the culture of everyday American life.

A reputation for liberal politics and policies contrasts with wide economic disparities in Minneapolis between people of color and white residents, who make up about 60% of the population. The enduring inequities – magnified by the coronavirus pandemic – raise questions among some Black activists about the city’s potential to equal Selma’s legacy.

Shanene Herbert runs the healing justice program for the Minneapolis office of the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization that promotes social equality. Reacting to large corporations in Minnesota offering statements of support and pledges of funding for the cause of social justice, she says, “Why now? Do you need your name attached to it? Will you leave when the cameras go?”

Yet if experience informs her skepticism, the huge wave of young adults powering the protests here and nationwide gives her a sense of optimism. “Our younger generation doesn’t have the patience of the older generations,” Ms. Herbert says. “They’ve seen enough. They’ve been traumatized and they’re not willing to wait for change.”

The urgency cuts across racial lines. Ella Masters grew up attending Trinity Lutheran Church in South Minneapolis, where last week organizers set up a distribution site for donated goods in the parking lot. The area’s two grocery stores and largest department store were among several businesses damaged or destroyed by rioters.

Ms. Masters and her partner, Cameron Kinghorn, drove to the church from their home a few miles away to donate laundry detergent, diapers, and other essential items requested by organizers. Without ignoring the toll on businesses, they credit the scale and duration of the protests for forcing the city to reexamine its relationship with race.

“A human life is more important than property,” says Ms. Masters, who is white. “We need people to get out of their comfort zone and start acting to save lives. Good intentions aren’t enough.”

Mr. Kinghorn, who is biracial, related that the recent upheaval has nudged some of his friends and acquaintances to reevaluate their passive advocacy for equality. “They’re looking for ways they can actively help,” he says. He hopes more of his cohort will step forward to push Minneapolis in the direction of Selma as a historical symbol of racial justice.

“I don’t know if we can ever reach that level,” he says. “But I think there’s a chance, and I would not have said that a couple of weeks ago.”

Patterns

How COVID-19, Floyd protests shape China’s crackdown in Hong Kong

The killing of George Floyd and the ensuing protests in the U.S. appear to have made China more confident about shrugging off any criticism it might get over human rights issues.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The wave of protests since the killing of George Floyd has rattled a world political order already buffeted by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. And one consequence is being felt thousands of miles away: an increasing likelihood of a Chinese security crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong.

When Beijing first signaled its intentions last month, it was part of a political fightback by the Chinese leadership on the coronavirus, which began its spread in the Chinese city of Wuhan. While China had by then largely contained the virus, major Western countries were still struggling with large numbers of cases.

Still, there was strong international pushback, especially from the United States.

Now, Chinese statements following the killing of Mr. Floyd, and the Trump administration’s call for a tough response to the protests in U.S. cities, suggest that Beijing is feeling even more confident about going ahead with the crackdown.

The gist of the Chinese message is that any U.S. objections to a toughened “law and order” intervention in Hong Kong – given the administration’s response to the protests over Mr. Floyd’s killing – will be dismissed as hypocrisy.

How COVID-19, Floyd protests shape China’s crackdown in Hong Kong

A new jolt to world politics – the wave of protests since the killing of George Floyd – has added to the already seismic effects of COVID-19. And one important consequence, thousands of miles away, is an increasing likelihood China will soon crack down on political freedoms in Hong Kong.

There’s no direct tie between either upheaval and China’s threat to impose tough new security legislation in Hong Kong. That was made last month, and it prompted a strong public response from Western governments.

But the timing of the initial announcement was affected by the altered politics of the coronavirus, which began its spread from the Chinese city of Wuhan. It was part of an increasingly self-confident political fightback by China’s leadership, which had largely contained the virus while major Western countries were still struggling to deal with large numbers of cases.

Now, China’s response to the Floyd killing has suggested it will feel even more confident about going ahead with the crackdown and shrugging off overseas objections, especially from the United States.

A major outlier

In much of the world, the response to the protests in American cities has been to sympathize with their declared aim of rooting out racism. Solidarity marches have been held in dozens of overseas cities: Thousands of protesters took to the streets of London last Sunday, for instance, despite Britain’s continuing struggle with COVID-19.

China’s response to Mr. Floyd’s death, however, was a major outlier, and not just because there were no public demonstrations of solidarity there. That was unsurprising given the tight controls on independent expression under leader Xi Jinping. More striking, and directly relevant to Hong Kong, were China’s pointedly critical comments about the Floyd killing, and about the Trump administration’s support for strong police and military action to contain unrest.

China’s clear message to Washington was this: You are in no position to accuse us of human rights violations, given the killing of Mr. Floyd in police custody and the administration’s tough reply to the protests.

This link was made explicit in China’s response to a U.S. State Department spokeswoman’s tweet a few days after the Floyd killing. She urged “freedom-loving people” everywhere to stand up for the rule of law and oppose Beijing’s plan for Hong Kong. She accused China of breaking its promises – a reference to the 1997 agreement in which Britain handed back Hong Kong to China, guaranteeing its autonomy and distinct legal protections at least until 2047.

A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman tweeted a brief phrase in reply to the statement, “I can’t breathe,” the three words caught on video in the final minutes of Mr. Floyd’s life.

China’s official Xinhua news agency was similarly biting in commenting on incidents of violence in some of the early protests in Washington, D.C. Recalling a remark last year by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that the pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong were “a beautiful sight,” Xinhua described the Washington unrest as “Pelosi’s beautiful landscape.”

The editor of Global Times, the tabloid published by the Communist Party’s People’s Daily, taunted President Donald Trump personally while also drawing a parallel with Hong Kong. Rather than “hide behind the Secret Service,” the editor, Hu Xijin, urged the president to “negotiate” with the demonstrators, “just like you urged Beijing to talk to Hong Kong rioters.”

A dramatic intervention

Even at present, Hong Kong’s freedoms are constrained. During the enormous street protests that began there a year ago this week over a proposed new law that would have allowed extraditions to the mainland, one increasingly urgent demand was for directly elected local government.

Yet Hong Kong does have an independent judiciary. Hong Kongers have far greater economic freedom and civil liberties than do Chinese on the mainland, including freedom of expression. Even last week, thousands ignored a police ban to mark the anniversary of the June 4, 1989, massacre of pro-democracy protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square – a commemoration unthinkable in mainland China.

For months, until COVID-19 precautions largely ended public protests in Hong Kong, China was getting increasingly impatient with the local authorities’ inability to halt them. Yet with China also in negotiations with the U.S. to wind down their tariff war, there was no sign that Beijing was ready to intervene directly.

The new security law would represent a dramatic intervention. It would supersede Hong Kong’s post-1997 legal dispensation and criminalize a wide range of political expression, in effect bringing the city into line with the rest of China.

And any chance that Beijing might have reconsidered as a result of international pushback against the prospect of a Hong Kong security crackdown now seems to have vanished, given its bullishly defiant political response to the George Floyd protests.

Internal security has become an overriding priority under Mr. Xi. And while Hong Kong in 1997 was a major contributor to China’s gross domestic product, China's economy has since grown to become the world’s second-largest, with Hong Kong’s contribution far more negligible. Even the fact the initial U.S. response has involved not just words but action – a move to end the special economic and trade disposition extended to Hong Kong due to its special status inside China – seems unlikely to matter.

Life after COVID-19: Recovered New Yorkers find hope in helping others

Known survivors of COVID-19 greatly outnumber lives lost. As buds of resilience begin to grace the previous epicenter of the virus, those who have recovered are moved to serve.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Globally, more than 3 million people have recovered from known cases of COVID-19. Yet as medical uncertainty about the virus persists, survivors are defining recovery on their own terms.

Pain, frustration, and fear of the unknown are common, but so is transformation. Several New Yorkers have begun to pour their renewed energies into giving – from volunteerism to donating plasma. As healing continues, they say serving others also fortifies themselves.

“When you help, you feel much better,” says Nima Sherpa, a recovered nurse from Queens. “I felt like we got a new life, and we should try our best to participate.”

Their altruism underscores a growing body of research that suggests humans are hard-wired for generosity, and that giving benefits one’s health and well-being.

Diana Berrent from Long Island founded Survivor Corps, a grassroots movement offering solidarity and resources for survivors.

Survivor Corps, she says, is the “epicenter of hope.” “What we’re seeing on the Survivor Corps group is people who are in the thick of the illness literally counting down the days until they can be part of that solution.”

Life after COVID-19: Recovered New Yorkers find hope in helping others

On a drizzly May day in New York City, Jim Burke lugs a cart of groceries through his Jackson Heights neighborhood. He isn’t headed home. The goods are for neighbors.

He pauses on the sidewalk in his mask and gloves. “It’s almost kind of selfish,” he says, to get joy out of giving.

Earlier this spring, Mr. Burke spent 10 days struggling alone in his apartment with COVID-19. He’d muster all his might to get up and shave, then collapse back into bed for the rest of the day, feeling worse than ever before in his life.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Since mid-April, he’s found the strength to drop off bags of donated groceries for Covid Care Neighbor Network, a mutual aid group based in Queens. Used to busy days volunteering as a transportation and LGBTQ activist, he’d been itching to rejoin community service once he recovered.

“It made me feel good for the first time in a long time,” he says.

Globally, more than 3 million people have recovered from known cases of COVID-19, according to data tracked by Johns Hopkins University. In New York, more than 68,000 have recovered – more than double the lives lost. Home to the previous epicenter of the virus, the state reported its lowest daily count of hospitalizations and deaths last Friday, down to 35 deaths from a high of 800 reached one day in April. The Big Apple began Phase 1 of reopening on Monday.

Yet as medical uncertainty about the virus persists, survivors are defining recovery on their own terms. Pain, frustration, and fear of the unknown are common, but so is transformation. Several New Yorkers have begun to pour their renewed energies into giving, recognizing that their city’s road to recovery persists. As healing continues, they say serving others also fortifies themselves.

“When you help, you feel much better,” says Nima Sherpa, a recovered nurse. “I felt like we got a new life, and we should try our best to participate.”

Ms. Sherpa found herself in two places at once. Her mind often traipsed home to Nepal as she healed from symptoms of COVID-19. Eyes closed on her bed in Queens, she also stood on a Himalayan peak, lungs filled with azure air.

Unable to get tested as her health declined in early March, the nurse scrambled to find one for her husband, who fared much worse. It took three tries before he was diagnosed – a frustration shared by many New Yorkers who faced a testing shortage early on. Her sons, ages 10 and 16, also became sick.

“I would cry and then I would wipe my tears” in the bathroom, she says, before returning to her family’s side with medicine and soup.

Though not usually religious, she turned to Buddhist mantras she learned as a child. She coaxed her bedridden husband to recite them, too. “I felt like it was helping us to breathe,” she says.

Ms. Sherpa took particular comfort in a mantra that evokes Green Tara, goddess of compassionate action. She recalled the image of the goddess’ unique posture – one foot slightly forward, as if poised to rise.

“My grandmother used to say she’s like that because she’s ready for anyone who needs help,” says Ms. Sherpa.

Fittingly, the Mount Sinai nurse has become a helpline for her own Nepalese community in Queens. As she awaits a return to work, she has waded through a daily flood of texts, Facebook messages, and phone calls from people worried about exposure to the virus, often in her native Nepali and Sherpa languages. She tries her best to soothe the fear and anxiety on the other end of the line.

“That’s the most important part,” she says.

Though her outreach tapered off mid-May as her family escaped to Colorado, Ms. Sherpa says she remains in touch with several strangers in New York who have received her support. Some call back with news of their own recovery.

Others have found renewed purpose in returning to work. Jasoda Latchman, a recovered NYC Health + Hospitals nurse from Ozone Park, Queens, tested positive for COVID-19 in March. Now she’s back at her hospital in the Bronx, reaching patients via telehealth to respect social distancing.

“I love what I do, so I love to be back,” says Ms. Latchman on a lunch break call. “I would not [let] the COVID virus push me away.”

Mounting evidence suggests humans may be hard-wired for generosity. Giving to others benefits health, mood, and even overcoming adversity, research shows.

“There is a strong relationship between resilience and altruism,” says Steven Southwick, professor emeritus of psychiatry, post-traumatic stress disorder, and resilience at Yale University School of Medicine. “It’s very well known that giving support increases one’s social and emotional well-being, and decreases our stress responses.”

In the wake of World War II aerial bombardments, people who felt satisfied caring for the immediate needs of others developed fewer trauma-related symptoms than expected. This research introduced the phenomenon called “required helpfulness,” he notes in his book, “Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges.”

Research by behavioral scientist Carolyn Schwartz has found that helping others may benefit mental health even more than receiving help. For both medical patients and nonpatients alike, helping others can lead people to find meaning in their own life challenges, says Dr. Schwartz, president and chief scientist at DeltaQuest Foundation, a medical research nonprofit in Massachusetts.

“By being able to help other people, it can transform the experience of something that makes all of us a victim to something that gives us agency,” says Dr. Schwartz, who is seeking participants for a study on psychological resilience during the pandemic.

Yet some recovered volunteers say they are still grappling with what they outlived. Surviving the virus in a community that is still grieving “takes a toll,” says Covid Care volunteer coordinator Dawn Falcone.

“I feel like it’s a good day if I don’t know anybody who passed away,” she told the Monitor in April.

Mr. Burke is also mourning the loss of several friends and acquaintances. “I’m going to be processing this for a while. ... Part of me feels like I cheated death,” he says.

Much about the new coronavirus still eludes scientists. There are no definitive answers yet on immunity and long-term effects of COVID-19. “So far, no studies have answered these important questions,” according to a World Health Organization statement sent to the Monitor.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers two definitions of recovery for symptomatic health care workers looking to return to work: one based on symptoms, the other on testing. Some doctors are pursuing experimental treatments that involve the blood plasma of those who have recovered – a century-old approach used to treat past viral outbreaks, including coronaviruses SARS and MERS.

Diana Berrent sums up recovery as a “bizarre, sort of liminal state.” She’s made the most of it by donating plasma six times and founding a grassroots movement, Survivor Corps.

She calls the virtual community the “epicenter of hope” that aims to hasten the pandemic’s end and help develop a cure. Survivor Corps’ website gathers research and how-to resources for mobilizing plasma donors, while its 54,000-member Facebook group offers a space for solidarity.

After testing positive for COVID-19 on Long Island in March, Ms. Berrent first envisioned organizing a global group akin to a COVID-19 Peace Corps, even offering hands for the dying to hold without adding risk to hospitals. But given the unsolved mystery of reinfection, she’s focused her efforts on donating her own antibody-rich plasma to science and calling on others to participate in the evolving research.

“To think that I’m actively contributing to the research that can bring about a cure to this is such an incredibly empowering idea and motivation,” she says. “What we’re seeing on the Survivor Corps group is people who are in the thick of the illness literally counting down the days until they can be part of that solution.”

Dean E. Williams Jr. joined Survivor Corps on Facebook and recently donated plasma. Having overcome the virus in isolation, he yearns to reunite with others.

Mr. Williams says he didn’t fear death. As he struggled to breathe alone in his Harlem apartment, his greatest fear was disappointing his 5-year-old daughter. He says he spent more than two months without seeing her as he quarantines in New York and she stays with family in another state. Online chess games and her reading of “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” over Skype has helped.

In her absence, the recovered Harlem Rotary Club president keeps busy with community outreach and organizing meal donations. He says his daughter joined him in community service as early as age 2, and hopes to bring her along volunteering when they’re reunited. In the meantime, a virtual sandwich-making party to benefit local food banks might soon be in order.

While they continue to live apart, a highlight came in mid-May as he was able to visit her for the first time in weeks – showering promptly after his arrival before they could embrace.

“It was the biggest hug she’s ever received from me,” he says. “She had the biggest smile on her face.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

When college is online, where do international students go?

Students from other countries come to the U.S. not just to study, but to take in a different culture. COVID-19 has changed the campus experience, leaving international collegegoers pondering, “Is it worth it?”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Asia London Palomba Correspondent

International students who study in the United States are navigating an unprecedented situation. Not only has the pandemic exacerbated existing challenges, such as securing visas, but it also has created a new set of concerns.

Rufaida Zareer Shams, from Bangladesh, plans to enroll as a freshman at the University of San Francisco, even if the fall semester is online. But she has reservations. “If a whole year is online, and it is the cost of a full year’s tuition, then no, I don’t think it’s worth it. But I guess students’ hands are kind of tied right now.”

Although a top destination, the U.S. has struggled to attract international students in recent years, with political tensions being a factor. On May 29, President Donald Trump issued an executive order suspending some Chinese graduate students from entering the country.

Students already attending school in the U.S. are still regrouping after the disruption caused by pandemic-related lockdowns.

“The crisis has made me appreciate my family and my loved ones,” says Sultan Aldabal, from Saudi Arabia, who attends Northeastern University in Boston. “I’ve learned how to adjust, how to adapt through the [fear], and it has given me a lot of time to think about my life.”

When college is online, where do international students go?

Marta Biino from Turin, Italy, was excited when she first got the news that she had been accepted to Columbia University’s master’s degree program in journalism. Living in New York City was a goal of hers and her acceptance into her dream school was an important accomplishment. But then the reality – that she might not be able to attend classes in the fall – settled in.

Now she is planning to defer her enrollment until January 2021, as uncertainty around campuses reopening continues in response to the pandemic. Although Columbia has given students the option to attend in-person in the fall, Ms. Biino is postponing to gain the time she needs to get settled financially and to secure a visa. She plans on working in Turin to help pay for her tuition.

“Since the virus has started, my parents have been working a lot less. ... If I get a loan, I’m not sure when and how we’ll be able to repay it,” she says. “I don’t know about paying $75,000 in tuition fees for a teaching quality which will obviously, despite best efforts, not be the same.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

International students who study in the United States are navigating an unprecedented situation. Not only has the pandemic exacerbated existing challenges, such as securing visas, but it also has created a new set of concerns. Besides weighing whether online classes justify expensive tuition, international students also don’t want to miss out on an integral part of the American university experience.

“It was always my goal to go abroad for higher education,” says Rufaida Zareer Shams, who lives in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and plans to enroll as a freshman at the University of San Francisco, even if the fall semester is online. “But if a whole year is online, and it is the cost of a full year’s tuition, then no, I don’t think it’s worth it. But I guess students’ hands are kind of tied right now.”

Anticipating a further decline

While international students are a sliver of the higher education population – 5.5%, or about 1 million – they spend more than $40 billion a year, according to advocacy group the Institute of International Education (IIE), citing Department of Commerce data.

In the past few years the number of international students has basically flatlined, after more than a decade of growth, as the Trump administration tightens visa and immigration requirements, says Terry Hartle, senior vice president at the American Council on Education, an association of higher ed institutions and groups. While the U.S. continues to attract the most students from other countries, more and more of them have begun to pick universities in Britain and Canada as hostilities mount and visas become increasingly harder to obtain.

“International students are an important part of American higher education,” says Mr. Hartle, noting that they bring funds and diversity to U.S. schools. “Based on conversations with college and university officials, we’re projecting a 20% to 25% decline in the number of international students who will come here this fall.”

The U.S. is typically a popular choice for students from China, accounting for 33.7% of the international student body, based on IIE figures. On May 29, U.S. President Donald Trump issued an executive order suspending some Chinese graduate students from entering the country. Officials are planning to revoke the visas of students and researchers affiliated with educational institutions linked to the People’s Liberation Army over concerns about intellectual property theft. The move comes in response to rising tensions between Washington and Beijing on matters concerning the pandemic, trade, and the status of Hong Kong.

Plans upended by the pandemic

Students already attending school in the U.S. are still regrouping after the disruption caused by the pandemic-related lockdowns. According to the responses from 441 institutions to an IIE survey administered during April and early May, 92% of international students remained on campus or in the U.S. Universities worked to provide housing, health care support, and online tutoring to them.

Sultan Aldabal, a rising senior studying political science and economics at Northeastern University in Boston, was at first unable to fly home to Saudi Arabia in early March due to cancelled flights. He has recently returned after months of being stuck in his Boston apartment. Although happy to be home, he is concerned that he may not be able to secure a visa to return to campus for his final semester. Still, the situation has given him time to reflect.

“The crisis has made me appreciate my family and my loved ones. … It really makes you look at things in a different perspective,” he says. “I’ve learned how to adjust, how to adapt through the [fear], and it has given me a lot of time to think about my life.”

Takato Watabe was finishing his junior year at the University of California, Los Angeles when the school ended in-person classes. The economics major initially welcomed the news about transitioning to an online format, and he and his friends celebrated by playing Nintendo video games. But then reality hit. Mr. Watabe, who returned home to Yokohama, Japan, on March 30, says he quickly missed the flurry of activity on his sprawling campus.

“The coronavirus has taught me a lot of things, like the importance of spending time, physically, with my friends and how important my time studying abroad was,” he says.

Unmoored, but resilient

Some students say they felt the same sense of unmooring that American students did, missing their routines and social circles in the U.S.

“Being independent, that was the motivation behind going to college for me,” says Ushna Arshad Khan, a rising junior from Lahore, Pakistan, studying mathematical economics at the University of Richmond in Virginia. “As a girl in Pakistan, you can’t do whatever you want or go wherever you want. In the U.S., it’s a lot better because you can basically carve out your day and not have anyone influence that. Also, when you’re in college, you’re surrounded by people doing the same things as you, so it’s easier to keep on track.”

Those students who couldn’t return home found ways to build communities and support systems on their abandoned campuses – many of which helped them cope with the stress of the pandemic.

Atri Hassan, a rising senior from Bangladesh studying psychology at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, found comfort in the small cohort of students who stayed behind, and from professors and international student organizations.

“I think having friends and roommates who are international really helped because we could at least talk to one another and update each other on what was going on,” says Ms. Hassan.

For Grea Lee, who just finished her first year at Amherst College, also in Massachusetts, the pandemic was manageable because of the college’s decision to move all remaining students into three central dorms. Although in-person interactions were discouraged, the move helped build solidarity and a sense of normalcy.

“I think just the fact that we were living in these dorms just sort of made people feel some kind of unity,” says Ms. Lee, who recently returned home to Suwon, South Korea. “Even if we didn’t really see each other that often, just the fact that we were sharing a living space together still made us feel like we were part of a community.”

Mr. Watabe, who usually is busy with coursework and internships in the U.S., now is spending valuable time with his family in Japan and on activities that make him happy, such as reading books and hiking. He plans to return in the fall if he can get a visa; otherwise he will take classes online from Japan. The crisis has given him a new appreciation for his American experience.

“I was in the States for almost three years, and that life in America became kind of normal. But it wasn’t. It was very, very rare and a valuable experience and the coronavirus taught me this. … It taught me how important my life in America was.”

Staff writers Nusmila Lohani and Cassandre Coyer and correspondent Ryan Yu contributed to this report.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Book review

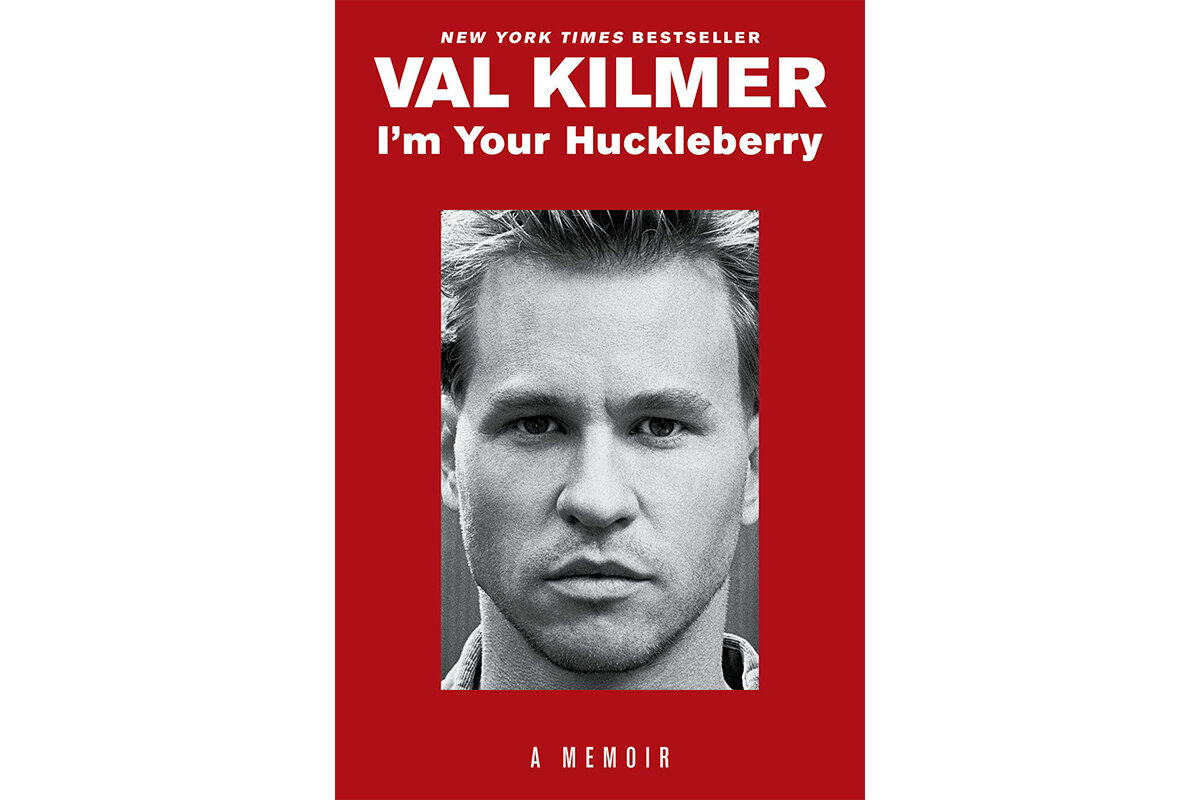

‘I’m Your Huckleberry’: Val Kilmer’s candid take on Hollywood and healing

Val Kilmer burst into movie stardom in 1986’s “Top Gun,” rose to leading-man status in the ‘90s, and then faced Hollywood oblivion before reinventing himself. His new memoir, “I’m Your Huckleberry,” chronicles his journey.

‘I’m Your Huckleberry’: Val Kilmer’s candid take on Hollywood and healing

It’s hard to resist an autobiography that begins with the words, “Dear Reader, I have a crush on you.” That charming opening seems to undermine Val Kilmer’s later claim that he has no game when it comes to pick-up lines. The iconic actor continues his introductory chapter by elaborating that he isn’t attempting to woo us. He’s expressing gratitude for the wave of love he’s been feeling from fans of late.

Mr. Kilmer is having a moment. It’s his first in a while. The actor’s colorful career spans a climb to Hollywood’s A-list, a banishment to its blacklist, and now a resurrection on the nonfiction bestseller list. Though Mr. Kilmer’s professional life dominates “I’m Your Huckleberry,” the underlying narrative arc of his autobiography is his spiritual journey. When a movie star loses everything – wealth, status, famous girlfriends, physical abilities – what does he learn about the essence of his identity?

To hear him tell it, Mr. Kilmer was never completely comfortable with the trappings of stardom. As a child growing up in the suburban fringes of Los Angeles, he was suspicious of the snobbery of the Hollywood area. Yet he was also drawn to that cultural mecca just beyond the isolation of the San Fernando Valley.

“Even back then I wanted to scream my declaration of freedom, though I was painfully shy,” he writes.

At age 16, Mr. Kilmer dropped out of high school to become the youngest person accepted to the drama school at Juilliard in New York. A career on Broadway was in the offing. But when he started dating the actress Cher, the world of Hollywood movies beckoned. Mr. Kilmer rues choosing film over theater by invoking an idiom: “God wants us to walk but the devil sends a limo.” He adds that treading the boards “would have been such a meaningful life, though a far less glittery one.”

Even so, Mr. Kilmer was reluctant to play Iceman, the cocky pilot with pincushion hair and a jawline as angular as the sharp end of an F-14 fighter jet in “Top Gun.” He thought the script was shallow. Yet the movie’s most memorable scene is arguably when the insouciant Iceman ends a face-to-face confrontation with Tom Cruise’s character by snapping his teeth shut like a Hungry Hungry Hippo. Mr. Kilmer reveals it was an improvised moment. The role – which Mr. Kilmer will reprise in the upcoming sequel “Top Gun: Maverick” – made him a star.

Mr. Kilmer observes that he made it just under the wire before the “death of film.” To paraphrase Mark Twain, news of the death of film is greatly exaggerated. But cineastes may well be right that cinema is past its apex as an art form. There was once a time when the Hollywood hills loomed like Mount Olympus in popular culture, its mysterious inhabitants worshipped like gods when they descended to wander among mere mortals. And in an age in which anyone with 500,000 Instagram followers is now considered a celebrity, audiences are less invested in who’s wearing the spandex and the capes on the big screen – the character, rather than the actor, is the main draw. (For the record, Mr. Kilmer arguably boasts the most distinctive chin ever to jut from the Batman cowl.) The allure of Mr. Kilmer’s artfully written and engaging book is that it’s a glimpse into that old world, receding in the rear view, of the classic Hollywood star system. He dutifully shares behind-the-scenes anecdotes of his most beloved movies, indulges in boastful name-dropping, and offers sweet encomiums to the many famous women in his life.

Though Mr. Kilmer trafficked in the currency of fame and fortune afforded him, the artists that he felt the deepest connection to were limelight-wary misfits such as Bob Dylan, Sam Shepard, and Marlon Brando. Mr. Kilmer’s quest for artistry often entailed clashing with directors over artistic decisions as well as practicing full-immersion method acting. He’d embody often-difficult and ugly characters for months on end. It cost him private and professional relationships.

“I had been deemed difficult and alienated the head of every major studio. I looked at the industry from the inside out, and from the outside in, and in a conscious and deeply satisfying act of authenticity, I hung up my hat,” he says.

The actor found his own escape from Tinseltown in New Mexico. He purchased a ranch that he intended to turn into an artists’ colony, but he ended up selling the property at a loss during the 2008 financial crisis. By that point, most of his acting work in direct-to-video releases might have been contenders for Razzie Awards had anyone actually seen them. Or as he puts it, “work that I’d describe as less than lofty.” Worse circumstances were still to come. Mr. Kilmer was diagnosed with throat cancer, and he later had two emergency tracheotomies to help him breathe.

Mr. Kilmer’s autobiography is often astonishingly candid – he’s the rare A-list actor who’s unafraid to reveal his eccentricities – but he’s just as often opaque about some aspects of his life. You won’t find out too much, for example, about his son and daughter, nor Mr. Kilmer’s older brother who all but disappears after an account of their childhood years. It’s his prerogative, of course, to keep some things for himself. However, Mr. Kilmer truly opens up about how his fall from grace has forced a great measure of introspection. As he puts it, he’s begun looking outside himself in an effort to deflate his ego. “Clearly I’m vain, but I’m workin’ on it, baby, I’m workin’ on it. In fact, I’ve never met anyone who has worked so hard on their vanity. LOL,” he writes.

He’s found succor in the writings of two figures of the 19th century: Mark Twain and Mary Baker Eddy. A few years ago, Mr. Kilmer wrote and starred in a solo stage show about Mr. Twain. The title of Mr. Kilmer’s autobiography, a quote from the movie “Tombstone,” is also an allusion to “Huckleberry Finn.”

Mr. Kilmer’s primary inspiration is Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science and founded this publication. Mr. Kilmer’s parents were Christian Scientists. He writes, “I inherited their faith through hard-fought experimentation and proof.” He lays out his interpretation of the teachings of Christian Science and credits prayer to God, whom he frequently refers to as divine Love, for healing his cancer “much faster than any of the doctors predicted.”

The earlier tracheotomy procedures have limited his ability to speak. The most affecting part of the book is how Mr. Kilmer writes about the tribulation of being stripped of one of the primary tools of his craft – his voice. Now he’s expressing his creativity as a visual artist, and has founded an artist’s community center in Los Angeles called HelMel. He’s also finding new ways to tell stories as a writer.

“I made a decision that, rather than looking for Love, I would let Love be me. Let Love be my life. Let Love seep through the pages of this, my life story,” he writes.

By the end of “I’m Your Huckleberry,” readers may well develop a crush on Val Kilmer.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The heart of police reforms

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The brother of George Floyd made a plea Wednesday about reforming police. “Teach them what it means to treat people with empathy and respect,” said Philonise Floyd. Indeed, cities are searching for fresh ideas in policing. In Dallas, for instance, when a police officer responds to a mental health call, a paramedic and a social worker go along in the car. The end result of such reforms, however, must fulfill that plea for empathy and respect. Examples can be found relatively easily. But if any city has shown how hard it is to achieve that goal, it is Camden, New Jersey.

Police in Camden are being taught to see dignity in residents, and in return, they are earning respect. That was made clear May 30 when the police chief, Joe Wysocki, was allowed to join a march protesting the George Floyd killing. Images went around the world of the chief chanting “Black lives matter” with his fist in the air.

The city is not yet a perfect model for how to teach police to treat people with respect and empathy. But the city knows what lies at the heart of any reforms.

The heart of police reforms

In his testimony to Congress Wednesday, the brother of George Floyd made a plea about reforming police departments in the United States. “Teach them what it means to treat people with empathy and respect,” said Philonise Floyd. For communities of color, he added, “make law enforcement the solution – and not the problem.”

Indeed, after the May 25 killing of George Floyd, cities across the U.S. are searching for fresh ideas in policing. In Minneapolis, the City Council took a radical step and voted to “defund” the Police Department. Other cities have been more modest, merely looking for successful examples to follow. In Dallas, for instance, when a police officer responds to a mental health call, a paramedic and a social worker go along in the car.

The end result of such reforms, however, must fulfill that plea for police empathy and respect toward a community. Examples can be found relatively easily. But if any city has shown how hard it is to achieve that goal, it is Camden, New Jersey.

In 2012, when Camden had a murder rate 17 times the national average, the entire Police Department was let go. The state built a new force under the wing of Camden County and appointed Scott Thomson as police chief. His No. 1 goal: Build a collaborative relationship with residents who at the time feared the police more than respected them.

If police learn to have greater empathy for the people they serve, said Chief Thomson, they will gain the trust of the community in preventing crime and catching criminals.

New recruits to the force were required to go door to door to meet the people on their beat. Police often held neighborhood cookouts or warmed up to teenagers by giving away ice cream from a truck. They were constantly trained on how to de-escalate a tense situation and to use deadly force only as a last option.

In the past seven years, violent crime in Camden has dropped 42%. In 2015, President Barack Obama visited the South Jersey city to praise its reforms. Much more work still needs to be done. Just over half of Camden’s police, for example, are people of color in a city of some 74,000 that is majority-minority. The state’s civil service exam remains a barrier to recruiting minorities.

Police reform can only go so far in a city that is one of the poorest in the U.S. Yet police in Camden are being taught to see dignity in the city’s residents, and in return, they are earning respect.

That was made clear May 30 when the current police chief, Joe Wysocki, was allowed to join a street march protesting the George Floyd killing. Images went around the world of the chief chanting “Black lives matter” with his fist in the air.

The protest organizers said they gained greater trust of Camden police that day. The city is not yet a perfect model for how to teach police to treat people with respect and empathy. But the city knows what lies at the heart of any reforms.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Never without our compass

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ralph W. Emerson

In life we so often find ourselves in need of guidance and direction. But above the waves of fear or pain or grief that we may face at one time or another, we can hear the Christ speaking – guiding, healing, and bringing us peace.

Never without our compass

Before the compass was invented, sailors on the ocean didn’t dare lose track of land or they could be left desolate. Now, those on a ship at sea take scrupulous care of the compass. It is protected by the binnacle that houses it. That amazing little needle on the compass always points toward the magnetic north pole, thus allowing the helmsman to orient himself on the globe. That needle is the sailor’s guide and protector.

How like our journey through life! We, too, have a guide and protector. It is Christ, the spirit of Truth and Love (synonyms for God), that steers us over the sea of life. Described by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, as “the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 332), Christ is our link to God, forever with us, revealing our true nature as God’s sons and daughters, made in His image and likeness.

Without Christ, we are like Job in the Bible, who lamented, “Oh that I knew where I might find him [God]! that I might come even to his seat!... Behold, I go forward, but he is not there; and backward, but I cannot perceive him” (Job 23:3, 8). We don’t really know what we are, where we are, or what we’re here for. But when we remember to check the compass, turn to the eternal Christ message, we orient ourselves aright, and find once again the spiritual understanding that leads us safely forward. Science and Health states: “Having no other gods, turning to no other but the one perfect Mind to guide him, man is the likeness of God, pure and eternal, having that Mind which was also in Christ” (p. 467).

I have often been lost at sea because I turned away from my compass. In the hubbub of a day’s activities, distractions pulled my thoughts aside, and I lost sight of land, the sense of God’s all-embracing love. But when I woke up and turned to my guide for help, my course straightened out.

At one time I felt a bad pain in my chest. It seemed like an inflammation inside my ribs. Breathing really hurt. It was frightening, for I thought it was a disease I had heard about that was potentially fatal. But I turned to my compass to feel God’s directing. I declared, “I won’t turn away from God for healing.” I knew that substance belongs to Spirit, and that matter has no real substance. Christ Jesus showed us that it’s natural to turn to Spirit, and not matter, for healing. And he has given us this sweet promise, “Nothing shall by any means hurt you” (Luke 10:19).

Science and Health states: “There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation, for God is All-in-all” (p. 468). Divine Mind is the real substance of existence, manifesting itself in its idea, perfect man. Christian Science teaches that the real man (which includes all of us) is perfect, because God is perfect. As that perfect man, I could express only comfort, wholeness, perfect health. So I put all my trust in God. This true Christlike understanding of God and man very quickly healed me. The disease vanished, and it has not returned after many years.

The word “binnacle” comes from the Latin for “dwelling place.” Our “binnacle,” our true dwelling place, is what the Bible refers to as “the secret place of the most High” (Psalms 91:1). The secret place is our consciousness of God’s love, which is always with us. It’s our real home, where all of God’s ideas, His spiritual offspring, dwell peacefully.

As Jesus tells us, “If a man love me, he will keep my words: and my Father will love him, and we will come unto him, and make our abode with him” (John 14:23). So not only can we say we are with Christ in God, but we can also say that he is here with us in our abode, our true consciousness. What a welcome presence! By listening to and heeding the Christ message, we can and will sail on safely.

A message of love

Back to school

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when columnist Ken Makin will explore the significance of capitalizing the word “Black.”