- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Supreme Court: Would Trump pick inevitably mean a sharp right turn?

- The Sudbury model: How one of the world’s major polluters went green

- For Tibetan refugees, the India-China border rift is personal

- ‘They want to be there’: More Estonian women go career military

- Black women learn homeownership – from tool belt to closing the deal

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How the ‘burnout generation’ can rekindle its flame

In recent years, a buzzy term has taken hold, particularly among millennials: self-care.

It’s a cry for help, says Anne Helen Petersen in her new book, “Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation.” Unlike earlier generations, who were able to earn more than their parents, millennials have been hit with two financial shocks a decade apart, on top of college debt that chains them to a punishing economic treadmill. Self-worth is measured by economic success and the identity that millennials present to others. What’s been lost, she argues, is a sense of true self.

“It really comes down to understanding ourselves as humans, with souls and minds, and not just as robots valued for our capacity to work,” says Ms. Petersen, a millennial herself, via email.

The author recommends activities divorced from career, screens, or pleasing peers. Go outside for aimless walks. Be your own companion. Her book borrows computer scientist Cal Newport’s definition of solitude as “the subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds.” We can’t listen to our inner voice if we’re constantly trying to keep up with the Joneses – or Kardashians – on Instagram.

As for self-care? Be careful it isn’t self-centered.

“Spiritual practice means finding meaning in the world around you – and meaning that doesn’t extend uniquely from work,” says Ms. Petersen. “Things that allow us to look away from ourselves and think about and serve others almost always make us feel better in some way.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

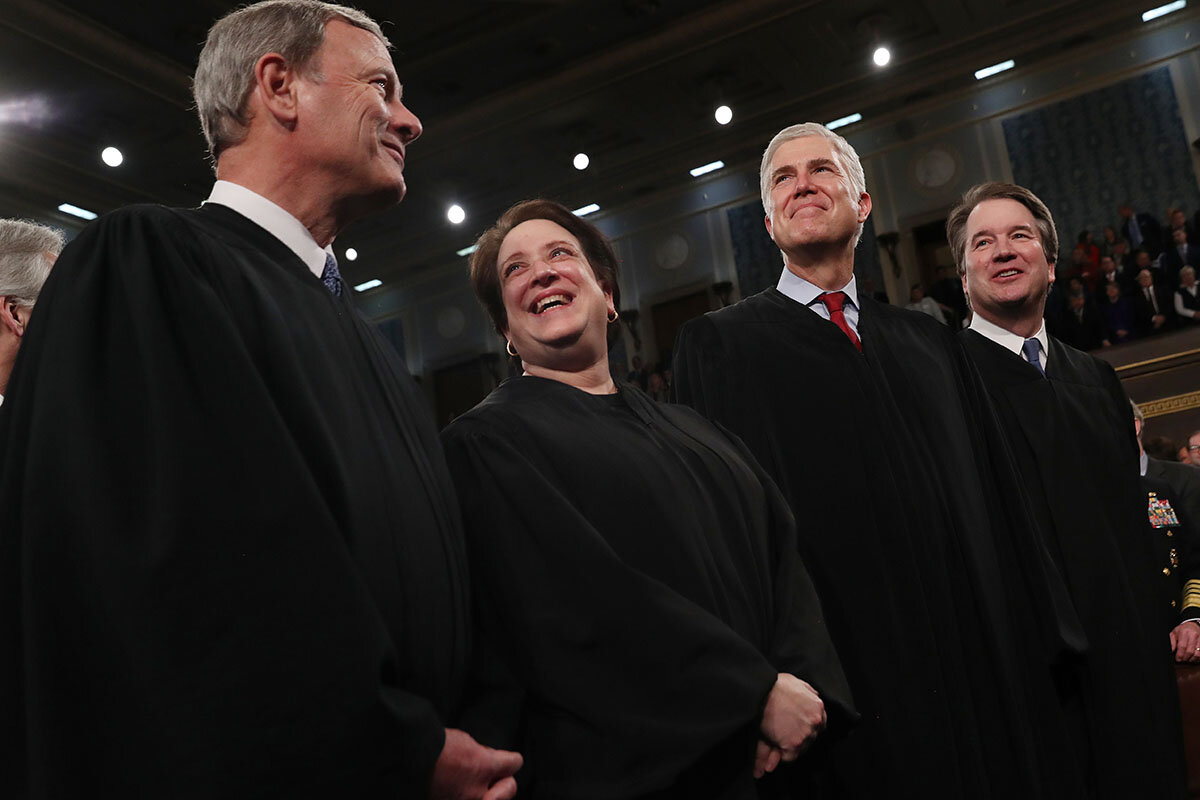

Supreme Court: Would Trump pick inevitably mean a sharp right turn?

If President Trump has his way, a reinforced conservative Supreme Court majority could work quick and radical change on everything from abortion and gun rights to federal regulations on the environment and finance.

President Donald Trump says he will, in a matter of days, announce his third nominee to the high court – a choice that, if confirmed, could transform the high court in a way perhaps not seen in close to a century.

The naming of a replacement for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died last week, is certain to provoke a fierce and partisan confirmation battle in the U.S. Senate. The president and other Republican Party leaders have made clear their intent to return the court to its full complement of nine justices as soon as possible.

A reinforced conservative, six-justice majority of jurists could shift influence away from Chief Justice John Roberts – who would cease to be the court’s ideological center – and advance conservative causes like regulating abortion, expanding gun rights, and reining in federal regulations. The only questions would be how radically, and how quickly, the court moves.

“It’s hard to know how uniformly more conservative the court would become until you know who is appointed,” says Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law. “But you can expect a more conservative court, and a more quick, or more radical, transformation of the court’s doctrinal views.”

Supreme Court: Would Trump pick inevitably mean a sharp right turn?

With a presidential election less than five weeks away, and a new term at the U.S. Supreme Court just over a week away, President Donald Trump says he will, in a matter of days, announce his third nominee to the high court.

The funeral for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose seat he would be filling after she died last week, is not scheduled until next week, but President Trump and other Republican Party leaders have made clear their intent to return the court to its full complement of nine justices as soon as possible.

The announcement is certain to provoke a fierce and partisan confirmation battle in the U.S. Senate. But if the nomination is successful, it could transform the high court in a way perhaps not seen in close to a century, securing a two-thirds majority of conservative jurists that could advance conservative causes like regulating abortion, expanding gun rights, and reining in federal regulations at a speed and scope of its choosing.

To date, President Trump’s two other appointments – Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh – have replaced other members of the court’s right wing. But replacing Justice Ginsburg, for decades a liberal stalwart of the court, would represent a much starker rightward turn.

It would likely see influence shift between the justices – namely away from Chief Justice John Roberts, who would cease to be the court’s ideological center. The conservative justices do not see eye to eye on every issue, a dynamic that could moderate decisions they reach in some areas of the law. But for the most part, it could be this reinforced conservative majority that would be shaping U.S. law for the next 15 or 20 years. The only questions would be how radically, and how quickly, the court moves.

“It’s hard to know how uniformly more conservative the court would become until you know who is appointed,” says Mary Ziegler, a professor at Florida State University College of Law. “But you can expect a more conservative court, and a more quick, or more radical, transformation of the court’s doctrinal views.”

Incremental vs. high-velocity change

Liberal justices have not held a majority on the Supreme Court since the Warren court of the 1960s. But since then, particularly in ideologically divisive cases, moderate conservatives like Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy have steered the court’s direction.

Chief Justice Roberts became the center of the court after Justice Kennedy retired in 2018, and he has regularly sided with his conservative colleagues since. Yet the chief justice, who has a strong belief in changing the law incrementally and keeping the court above the political fray, has unexpectedly joined his liberal colleagues in a few significant decisions as well. In 2019, for example, he wrote the plurality opinion blocking, on procedural grounds, the addition of a citizenship question to the 2020 census. And this past summer he voted to strike down a Louisiana law restricting abortion access.

Should President Trump replace Justice Ginsburg, then his past two appointments – Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh – would probably become the median justices on the court, experts say. And more conservative members like Justice Clarence Thomas, who have historically been on the fringes, could see their influence grow.

The president “will transform the 5-4 John Roberts court to the 6-3 Clarence Thomas court,” tweeted Mike Davis, head of the Article III Project and an advocate for President Trump’s judicial picks.

There might be no definitive “swing” justice, but the reinforced conservative majority would still have disagreements. How far and how fast the court moves to the right would be moderated, if it’s moderated, by the chief justice and, perhaps, Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh.

“For conservatives, there’s still a pathology to go to the middle,” says Josh Blackman, a professor at the South Texas College of Law. “Liberal justices do what they need to do, but conservative justices tend to want to play ball.”

There are some recent examples to the contrary, including liberal Justices Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer joining with conservatives in some religious liberty cases. But there have also been times when President Trump’s two appointees have defied some expectations. In the past term, Justice Gorsuch joined the liberals in voting to expand employment protections for LGBTQ Americans, and in another landmark case, both Trump appointees concurred with a ruling that President Trump can’t block access to his personal financial records.

And Justice Kavanaugh could prove to be a pivotal vote on one of the issues of most immediate concern to liberals: abortion rights.

Almost from the day it was decided, there have been arguments that Roe v. Wade – the 1973 ruling that established a constitutional right to abortion – was poorly reasoned and should be overturned, particularly from conservatives. (Some liberals, including Justice Ginsburg, said the ruling did too much too quickly.)

Whether a court with six conservative justices would directly overturn Roe is unclear, and would probably require Justice Kavanaugh’s vote. But abortion rights would almost certainly be restricted further, says Professor Ziegler, and restricted at a faster pace than the court has followed in recent decades.

“It would be a chipping away” of abortion rights, she adds. “Kavanaugh has shown more willingness to erode abortion rights more quickly.”

So if Roe does get overturned, “you certainly couldn’t say that it happened overnight,” says Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School.

Indeed, the speed and scope with which the judiciary shapes the law are determined by multiple factors. Judges don’t shape legal doctrine alone, Justice Ginsburg said in a 1992 speech, but also “participate in a dialogue with other organs of government, and with the people as well.”

Strengthening executive power and expanding the Second Amendment are other areas of the law that could change rapidly with a six-justice conservative majority on the court, experts say. The question would be if enough justices agree that the law needs to change quickly and broadly, despite what the public or other branches of government might think.

“If you think a precedent is really awful, then it’s entirely reasonable to think that it has to go, even if there are some risks involved,” says Professor Somin. “When it comes to other issues I think it depends on the issues, the magnitude of the risk, and so on.”

Heightened public approval of Roberts’ court

Whether or not the public agrees with the court is another question, and how the justices weigh that institutional risk would in large part define a six-justice conservative majority’s decision-making.

While some conservatives criticized the court’s rulings last term – including President Trump, as well as Vice President Mike Pence, who called Chief Justice Roberts “a disappointment to conservatives” – the court came out with its highest public approval rating since 2009.

Approval of the court rose sharply among Democrats in particular, likely due in part to the rulings on LGBTQ rights, the Louisiana abortion law, and the Obama-era deportation program. Some experts believe that, with a stronger conservative majority on the court, even those small liberal wins could disappear.

“Without that you have a court that’s pulling more towards a Clarence Thomas approach,” says Kimberly West-Faulcon, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. “And if you have five justices on that [approach] you get there faster.”

“It’s difficult to overstate the doctrinal significance of President Trump appointing a new justice to the court,” she adds.

Two historical eras have been referenced by court watchers since Justice Ginsburg’s death: the New Deal era of the 1930s and ’40s, and the 1850s. Both eras featured Supreme Court justices named in an earlier era and at odds with the beliefs and priorities of the current one, and in both the disconnect helped fuel some of the most turbulent periods in U.S. history.

If President Trump and the Republican-controlled Senate confirm his third Supreme Court justice, the United States could enter a similarly jarring and divisive period, some experts warn.

“A court chosen and confirmed by Republicans elected predominantly by White voters, a clear majority of them Christians, could write the rules for years while both of those groups are continually shrinking as a share of society,” wrote Ronald Brownstein, a senior editor at The Atlantic, for CNN.

“That could be a recipe for explosive conflict.”

Other experts aren’t as concerned.

“There’s good historical evidence [that] when the court does completely ignore public opinion, there’s a big backlash,” says Professor Ziegler. “And there’s nothing to suggest that’s changed.”

Regarding abortion, she believes that if Roe is overturned it would simply be “the beginning of a new cycle,” with the roles reversed and the abortion-rights movement looking to persuade the Supreme Court to reverse its precedents.

“You would expect the pace of change across doctrinal areas to accelerate; it would just be a little bit hard to know doctrinal area by doctrinal area,” she adds. “But any kind of setback in this context is temporary, not permanent.”

And when considering the speed and scope of doctrinal change, Justice Ginsburg’s thoughts on Roe v. Wade may be relevant.

“Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped,” the late justice said in 1992, “may prove unstable.”

A deeper look

The Sudbury model: How one of the world’s major polluters went green

In one Canadian industrial region, the most famous landmark is a towering smokestack. But efforts to beautify the once-polluted town reveal how industrialists and environmentalists can find common ground. And remove the chimney’s long shadow.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

When the Superstack was constructed in 1972, it was the tallest structure in Canada – and the tallest smokestack in the world. Built by a Canadian mining company, the Superstack has long stood as a reminder of the environmental devastation that mining wrought here in Sudbury, Ontario.

It also tells a powerful tale of renewal. The stack was built as part of an industrial complex that denuded the land here of any kind of vegetation, leaving blackened rocks and lakes without fish. The landscape drew comparisons to barren moonscapes. At one time the sulfide ore smelters in Sudbury were the world’s largest point source of sulfur dioxide.

It got so bad that stakeholders came together to halt the pollution, replant the trees, and restock the lakes. Today Sudbury enjoys some of the cleanest air quality in Ontario. Residents swim and fish in the 330 lakes inside the city’s boundaries. And those here say the community offers a lesson in how to break the cycle of conflict that the current climate crisis often creates, pitting industry against the environment.

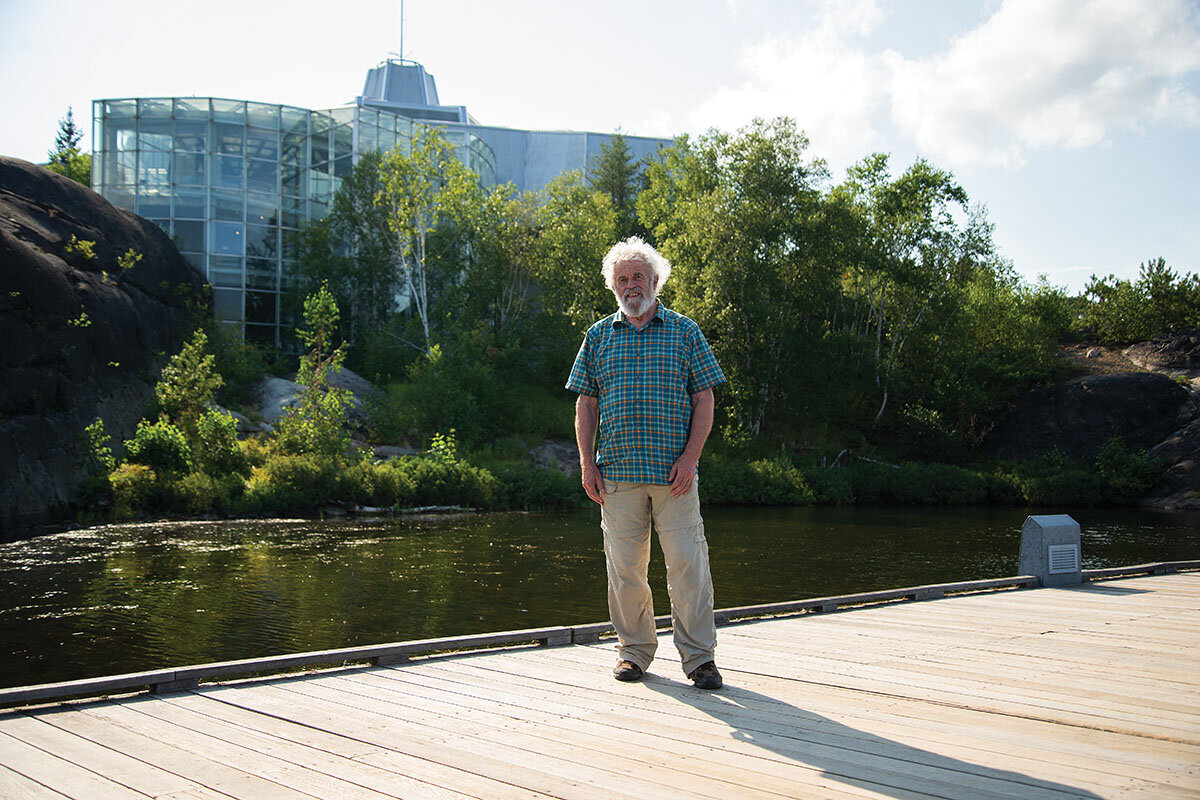

As David Pearson, a driving force behind Sudbury’s transformation says, “That’s what we need to take from the Sudbury story, and we need to apply it to today.”

The Sudbury model: How one of the world’s major polluters went green

When the Superstack was constructed in 1972, it was the tallest structure in Canada – and the tallest smokestack in the world. At 1,250 feet, it’s visible from every vantage point in the area. It can be seen from the bustling streets of downtown to the quiet cul-de-sacs of residential neighborhoods. It looms large in the distance from highways that feed into a city that is home to one of the largest mining complexes in the world.

Built by Canadian company Inco before it was purchased by Vale, the Superstack has long stood as a reminder of the environmental devastation that mining wrought here. But this year the chimney is being fully decommissioned.

Residents of Sudbury harbor mixed feelings about the Superstack. Some see it as a memorial to their rise as a center of nickel and copper mining globally. Others see it simply as a familiar landmark that signals they are home. Gisele Lavigne lives in the Copper Cliff neighborhood at the Superstack’s base. She spends her evenings looking at the towering structure from her yard, and likes it when the stack disappears behind a heavy fog. “And when it rains, you’ll see half a stack, depending on which way the wind blows,” says her partner, John Leach, who works in the mining industry doing sand and high-pressure water blasting.

Others see the Superstack as a relic of an era of polluting that doesn’t fit with the current ethos of Sudbury. One leading scientist here, John Gunn, believes the concrete shell should be “blown up.”

Whether or not the structure remains a fixture on the skyline when it’s taken out of operation, it tells a powerful tale of renewal. The stack was built as part of an industrial complex that denuded the land here of any kind of vegetation, leaving blackened rocks and lakes without fish. The landscape drew comparisons to moonscapes and barren Martian worlds. At one time the smelters in Sudbury were the largest point source of sulfur dioxide in the world.

It got so bad that scientists, politicians, industry officials, and the community finally came together to halt the pollution, replant the trees, and restock the lakes. It has been 40 years of toil and triumph, and the story is not over yet. But today Sudbury enjoys some of the cleanest air quality in Ontario. Residents swim and fish in the 330 lakes inside the city’s boundaries. And those here say the community of 165,000, at the gateway of northern Ontario, offers a lesson in how to break the cycle of conflict that the current climate crisis often creates, pitting industry against the environment.

“That’s what we need to take from the Sudbury story, and we need to apply it to today,” says David Pearson, an earth scientist and driving force in turning around Sudbury.

“When one speaks of the Sudbury story,” he says, “it somehow seems local and isolated, and it’s not local and isolated. It’s an example of what we need to modify in order to be able to live alongside a thriving environment.”

***

This area was once called Ste. Anne of the Pines for the old-growth forest that flourished here. Later, after the logging industry moved in, lumber harvested from the prized trees was shipped far and wide – including to Chicago to help rebuild after the Great Fire of 1871.

Environmental devastation accelerated after the 1880s when metal deposits were found along a crater formed by a prehistoric meteorite impact. The deposits, discovered during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, represented one of the largest concentrations of sulfide ore in the world. The metals forged in huge foundries here were used to build armaments during both world wars. Early methods of roasting the ore polluted the landscape locally, while later smelting techniques expanded the damage regionally. Dr. Pearson, who arrived from a coal mining town in northern England, remembers distinctly how bad the air smelled one day in 1969. “It was perhaps humid, and [the plume] came down to ground level,” he says. “And I parked in the parking lot, and I had to run in order to be able to hold my breath long enough to get into a building because the smell of the sulfur dioxide was so powerful even in my car. ... I had never experienced anything nearly as penetrating a pollution as this.”

For a child in Sudbury back then, fun didn’t involve climbing trees or playing hide-and-seek in the forest. Young people like Dave Courtemanche, who went on to become mayor, clambered over rocks. There was no greenery to be found in his neighborhood or at his school, which directly faced the mining slags. One day in 1975, a university professor came to Dave’s fifth grade class to propose an experiment: Let’s see if we can get grass to sprout in the barren landscape.

On a hillside, he and classmates carved out an acre of land and limed and fertilized it. As tufts of grass began to poke through, he recalls a feeling that might be comparable to children of the tropics seeing their first snowflakes. “Looking up and seeing a green patch emerging from the dead earth was nothing short of a miracle,” he says from that old school building today, which looks out onto woods and grassy fields. Mr. Courtemanche was unwittingly among the first volunteers in one of the largest regreening efforts in Canadian history.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, Sudbury was a company town. At its peak, 20,000 miners worked underground – the ebbs and flows of the city defined by worker shifts. No one dared speak out against the industry.

But then Laurentian University was established in 1960. “Nobody was going to say anything against the company, essentially,” says Peter Beckett, an ecologist at the university and chair of the city’s advisory panel on regreening. “And so the university was kind of the first independent thing in the town, and people started asking questions: ‘Can one do anything about the landscape?’”

As it turns out, they could. Biologists at both the university and at Inco had been experimenting with regreening, first potting plants and then moving to plots outside. By 1975, the “Sudbury recipe” was created – the basis for a massive liming project that would neutralize the soil and allow for replanting.

The effort coincided with a downturn in the nickel industry and worries on the part of local politicians that the town wasn’t going to survive unless it reinvented itself. Regreening became a communitywide endeavor. Unemployed miners and student volunteers alike wielded lime sacks and scattered seed. Dr. Beckett remembers the first year in 1978, when the community landscapers would scour their Garden of Eden for the first shoots. “After the Aug. 15 [heavy rains] that first year, every member of the committee was out every day looking constantly at the same area to see if any green fuzz was coming up,” he says. “And then one day, about a week later, everybody just shouted, ‘eureka,’ just like the Greeks.”

On a hillside overlooking Kelly Lake, Dr. Beckett and Graeme Spiers, another scientist from Laurentian University, show how the landscape would have looked if no replanting had taken place. They point to a sickly birch tree surrounded by a few mounds of metal-tolerant hair grass.

Nearby stands a lush forest. It’s one of the replanted parcels. Overall, locals have created a forest of about 10 million trees and shrubs. Since 2010 they have focused on replanting native species, about 80 different types, and they are working on measuring carbon capture that will help the city meet its goals to be carbon neutral by 2050. After 40 years and $33.5 million (Canadian; U.S.$25.4 million), they are about halfway through the recovery of 200,000 acres of land.

Yet the effort is about more than fixing a lost landscape. “If you improve the environment, you attract people and suddenly your community starts feeling better about itself,” says Dr. Spiers.

The two have traveled the world delivering that message – to Australia and South Africa, Peru and Poland, Chile and China. Their roadshow is called “Sudbury, 40+ Years of Healing.”

***

None of this would have been possible without tough regulations, though. When the Superstack was built, mining’s motto for the era was “Dilution is the solution to pollution.” New technology and evolving processes helped reduce emissions in Greater Sudbury, but the Superstack dispersed them further afield, to neighboring provinces, and as far as the United States and Greenland. It essentially turned a local problem into an international one.

Sudbury’s reputation was already suffering. In 1971 and 1972, NASA sent astronauts to the city ahead of the Apollo moon missions to study the geology of the crater basin. It was the second-largest impact crater in the world, and they wanted to prepare for similar sites they might see on the moon.

But instead of lauding Sudbury as a lunar training ground, the press came up with another moniker for the city: a moonscape. The city’s image took a severe hit.

It didn’t help that emissions from the Sudbury smelters had affected an estimated 7,000 lakes in the region. Declining populations of lake trout, which thrive in Canada’s cold, clear northern waters, became a symbol of the environmental degradation, similar to what the polar bear is today for a warming Arctic.

Dr. Gunn, director of the Vale Living With Lakes Centre in Sudbury, recalls attending his first international science conference in Ithaca, New York, in 1980 and learning that his peers were using the name Sudbury as a unit of pollution – “How many ‘Sudburys’ does your country represent?” He says he has since devoted his entire career to make the term Sudbury known as a “unit of restoration.”

Sudbury’s pollution even sullied relations between the U.S. and Canada, as acid rain emerged as a significant environmental issue. “I traveled to Washington, New York City, and a couple of other places in the United States and tried to persuade them to cut their emissions. And when I would go down to lecture them on their problems, the first word that would come out was Inco,” says Jim Bradley, who was Ontario’s environmental minister at the time and grew up in Sudbury. “Inco was the largest single emitter of sulfur dioxide in North America at the time.”

So the provincial government developed the Countdown Acid Rain program, which forced Inco and other major polluters in 1985 to cut emissions by more than 60% in under a decade. The companies balked at first. But Mr. Bradley remembers the exact moment he knew they had changed.

“Three years later, they came down to Toronto and had a press conference, with the word Inco in green,” he says. “And there they announced that they would not only be complying with the regulation that we were forcing on them, but that they would be exceeding the provisions of it and that they would be making a profit of 19% on one aspect of it and 6% on another aspect.”

Part of the shift was driven by the changing politics of the environment. The Superstack had become a rallying point for activists in both North America and Europe. “The [company] didn’t want a dirty reputation,” says Dr. Gunn. “Senior executives admitted that their kids gave them [trouble] at home.”

Today, Dr. Gunn stands at the edge of Silver Lake, which he once documented in a book as being one of the most acid- and metal-contaminated bodies of water in the world. Kids are jumping off rocks. A dog paddles furiously in the water.

The whole cleanup, local organizers say, is a testament to how the community came together. “There’s no question, of course there was finger-pointing, but it was not the dominant mood at the time,” says Dr. Pearson, the earth scientist. “You have to remember that the city was very defensive, very self-conscious. ... So when there were glimmers of an opportunity to repair the landscape and improve the image of the community, people got together without pointing fingers. It was a ‘let’s get on with this’ kind of attitude.”

Everyone, young and old, got involved. “It was such a powerful experience for our children because now they were part of the solution,” says Mr. Courtemanche. “I would argue that you can’t be part of the solution until you see yourself as part of the problem. So we were all part of the problem here. We let the landscape perpetuate the way it was until folks realized they could come together and effect phenomenal change.”

That, he believes, is a lesson urgently needed today. “This idea that you have to take sides, that these types of major issues are political and polarizing, I think is fundamentally wrong. People just need to show up and say, ‘I’m going to be part of the solution.’ And quite frankly, I think the world needs more Sudburys if we’re going to tackle some of these major issues facing society, whether we’re talking about climate change or COVID.”

***

Sudbury is still very much a mining town. There are 7 to 11 mines operating at any given time, says Jennifer Beaudry, the senior manager at Dynamic Earth, a mining museum. It’s just that mining looks very different than it once did.

The Superstack is part of that evolution. The mining company Vale finished the final steps to take it out of service in July, replacing the towering structure with two smaller stacks that require far less energy to operate and will reduce greenhouse gas emissions at the smelter by approximately 40%. The move is symbolic of how technology is advancing, and the city has become a research hub for new mining techniques.

“It’s not shovels and pickaxes [anymore],” says Ms. Beaudry.

The narrative is not unblemished, though. Some locals think the mining companies, for all the profits they dug out of the ground here, should have done more – earlier – to help both workers and the town.

Yet the overwhelming feeling seems to be one of pride in the city’s restoration. In 2015, Canada’s statistics agency polled urbanites nationwide and found Sudbury’s residents to be the happiest in the country. Tourists no longer come to see the slurry in the city’s big smelters run like hot lava. Instead they head to Dynamic Earth to go on an underground tour, or visit Science North, the city’s renowned science museum. More students are flocking here, too.

“No, this is not a mining town, at least not anymore,” says Vinay Balineni, a student from India who is working on a business degree.

Pride in the city’s new environmental ethos is even reflected in local art. Muralists paint building facades with scenes that celebrate natural resources. “There’s been not just transformation of the environment but transformation of the mentality of why it’s important to create opportunities for environmental consciousness and conservation,” says Johanna Westby, a muralist and graphic designer whose works depict lakes, trees, water, and birds.

Perhaps more important for the future, a new generation of environmental activists is taking root in Sudbury. Jane Walker, Maggie Fu, and Sophia Mathur epitomize the trend. The three teens, who just started eighth grade, recently participated in virtual climate training with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore.

Sophia is often called Canada’s first climate striker, joining Swedish teen activist Greta Thunberg and youths around the world in skipping classes every Friday to demonstrate on behalf of the environment. She is also the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit against the Ontario provincial government for weakening its climate targets. The 13-year-old infuses her words with passion, eloquently talking about the intersection of social and climate justice.

“I think Sudbury’s regreening showed everyone [here], and the world, that with our community working together, we can make a difference,” she says.

It’s a story of inspiration the three teens hold close to them while they carry out their strikes, which they do virtually these days because of the pandemic. Says Jane: “If we can do all this [transformation] in the community, well, then we can do anything to try and help our environment.”

For Tibetan refugees, the India-China border rift is personal

As tensions rise between India and China, we visit a Tibetan community caught in the liminal border between the two nations to see how the conflict impacts individual lives. A testament to grace under pressure.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Choglamsar, India, is a cluster of one-story mud brick houses on the banks of the Indus River, surrounded by the Himalayas. It’s one of many Tibetan settlements scattered across India, and a Tibetan flag waves from atop the community center, where residents queue to get tested for COVID-19.

Late last month, the village lost resident Tenzin Nyima, who was killed in a mine blast near the Line of Actual Control. The line is the de facto, disputed border between India and China – which have been in a standoff since May.

The death of Mr. Nyima, a soldier whose covert unit is mostly Tibetan refugees, has drawn particular attention. He was given a grand public funeral attended by Indian officials, the first time a Tibetan had been recognized for military service. Tibetans hope the spotlight on the border could prompt more support for their cause.

One local hoping for change is Sonam Tsering, a former soldier whose parents fled to India. Today, he waits for customers behind a pile of jackets at the market – a headband that says “Free Tibet” to his side, below photographs of the Dalai Lama.

“It has been a long time here so India feels like my country, but my heart is in Tibet,” he says.

For Tibetan refugees, the India-China border rift is personal

In a tiny room of her brother’s house, surrounded by female relatives, Tsering Tsomo is pouring oil in dozens of brass lamps, keeping them alight in his memory. For 49 days after his death, the family will host monks and relatives here at his home in Choglamsar, India, lighting incense and offering prayers. Wearing trousers and a T-shirt, prayer beads hanging from her neck, Ms. Tsomo whispers Buddhist prayers for peace for her brother’s soul, sometimes shuffling her beads.

Tenzin Nyima was killed late last month in a mine blast more than 100 miles away, near the Line of Actual Control, the de facto border between India and China. The two nuclear-powered countries have been in a standoff since May over their disputed border in the western Himalayas. At least 20 Indian soldiers have been killed in clashes, and both armies have accused the other of incursions, with warning shots fired in early September.

But Mr. Nyima’s death, in particular, has brought attention. Like several Tibetans in Choglamsar, he had joined India’s Special Frontier Force (SFF), a covert unit composed mostly of Tibetan refugees. Some 90,000 Tibetans live in India today, after their families fled following a failed uprising against China’s rule. And after decades here, many say they deserve greater support from New Delhi. As the rest of the world eyes the border tension nervously, they hope the attention could prompt change for their homeland – though many analysts find that unlikely.

India has benefited immensely from Tibetans’ presence, says Dibyesh Anand, professor of international relations and an expert on Tibet at the University of Westminster in London: from rejuvenating monasteries, to improving India’s soft power as the adopted home of the Dalai Lama, and offering legitimacy to New Delhi’s border claims.

But “most Indians are not even aware of Tibetan contributions,” he says, reflecting India’s balancing act: how to support Tibetan refugees, without Beijing accusing New Delhi of meddling in internal affairs. The community’s low profile is “reflective of a conscious government policy to not highlight Tibetan presence, and avoid accusation of using the ‘Tibet card’ vis-à-vis China.”

Yet as Indian and Chinese forces prepare for the coming harsh winter, Tibetan residents of Choglamsar watch the Indian fighter jets flying above, still hoping for a “free Tibet.”

Caught in limbo

Choglamsar is a cluster of one-story mud brick houses, with a monastery atop its foothill. From the monastery, one can see the whole town on the banks of the Indus River – 11,000 feet up, surrounded by mountains. On one end of the hill, painted stones spell out “Save Tibet” near a community center, where residents queue to get tested for COVID-19. A Tibetan flag is waving on the top of the center.

A month before leaving for the border, Mr. Nyima had visited his older brother Tenzin Namdakh here, the town where they’d lived for 20 years. Sitting in the courtyard of his brother’s house, Mr. Namdakh recalls him saying, “I don’t know whether I will be back or not; you stay well. I’m being posted at the border, so take care of my family, because there is no guarantee.”

Mr. Nyima was given a grand public funeral in nearby Leh, attended by Indian officials. It was the first time a Tibetan in India had been recognized for military service, though the government did not issue a statement.

Many Tibetan residents say that silence makes them feel used – particularly young Tibetans, like Thinley Choedon. She studies journalism, and believes that it is time for India to strengthen its stance on Tibet.

“The Indian government has been playing with us,” she says. “Many generations have already passed and we have fought the Kargil War and Bangladesh War for India. The Indian government must realize how much they have used us.”

By some measures, India has shown long-standing support for Tibetans who fled across the border, and their descendants. The Dalai Lama and Tibet’s government in exile are based in Dharamsala, 400 miles south, and there are dozens of Tibetan settlements across the country.

But refugees lack full citizenship rights, and even those eligible to apply often prefer not to. Without citizenship, most cannot join government services except the army, and many rely on livestock or menial jobs. Just 10 years ago, there were 150,000 Tibetans living in India, but many have migrated further.

“The income of many families also depends on their children’s jobs; many have joined the Indian army. That helps the Tibetan community,” says Tseten Wangchuk, the Tibetan government in exile’s representative for some 7,000 Tibetans in the area. In India, “we have our identity and we need to preserve our own culture. We have enough space here to protect our culture and religion.”

In 2003, India recognized the Tibet Autonomous Region as part of China, and said it would not allow “anti-China political activities.” Some argue that India should press on the Tibet issue, but the government has held back, concerned about Chinese reprisals. In 2018, the government stopped officials from attending a public event held by the Tibetan government in exile, saying such participation “is not desirable and should be discouraged.”

“My heart is in Tibet”

Three miles from Choglamsar, in Leh, is a Tibetan Refugee Welfare Association market: a small area with makeshift shops lining each side of the aisles, with jackets, trousers, and Buddhist prayer flags hanging. At one end, in a corner, Sonam Tsering waits for customers behind a pile of jackets. A headband with “Free Tibet” written over it is hanging on his right side, just below the framed photographs of Tibet’s spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama.

Mr. Tsering, a former SFF soldier, still recalls his own time serving at the border, when “there was no war.” After migrating from Tibet, his parents settled in Karnataka, a southern Indian state. But for the past 20 years, he has been traveling to Leh to run his shop from March to December.

“It has been a long time here so India feels like my country, but my heart is in Tibet. Some Tibetans have taken Indian citizenship, but I didn’t because I won’t be part of the Tibet community then anymore. No one in my family has taken citizenship,” he says.

During the peak tourist season in Leh, Mr. Tsering typically earns at least $800 a month. The pandemic and the clashes have kept tourists away, and this year he hasn’t even made half that. Yet if tensions continue, he hopes “it can help get Tibet freedom.”

Currently, India’s diplomacy does not stress either human rights in Tibet or Tibetans’ demands for self-determination, Professor Anand says. But given their existential crisis as a community, as the years in India go by, “they have to engage with whatever opportunity they have for their identity to be recognized.”

Ms. Choedon, the journalism student, expresses a similar view. The first thing for New Delhi is to “accept that [the border tension] is not an India and China problem but an Indo-Tibet border issue. This is a chance; people of Tibet have got their own image now.”

‘They want to be there’: More Estonian women go career military

Following a sharp rise in the number of women enlisting in Estonia's Defence Forces, the small nation is saluting the qualities that they bring to their service.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

An increasing number of young women are voluntarily enrolling in Estonia's conscription service, which is required for men, and then choosing to enter military service professionally. And with the world’s spotlight on the volatile situation in nearby Belarus, and the continuing fraught relations between the Balts and Moscow, the Estonian military appears to be embracing this shift in mindset.

The Estonian military is built around a reserve army model where conscripts are trained for eight or 11 months, whereupon they become part of the reserve force. Active armed forces number around 6,000 troops, roughly half of whom are conscripts.

This summer 46 Estonian women volunteered for the conscription service as part of the July “intake,” the most ever at one time. Also, this year over 50% of the women conscripts decided to join the regular army. At present there are 336 women serving in active service – about 10% of the 3,508 soldiers.

“In my experience, Estonian women are very independent and perform their duties very well. The women who join the military are much more motivated than their male colleagues,” Petty Officer 3rd Class Maria Tõkke says. “After all, they want to be there.”

‘They want to be there’: More Estonian women go career military

When Petty Officer 3rd Class Maria Tõkke first volunteered to join the Estonian Defence Forces (EDF) in January 2019, she got an earful from some of her male friends.

“[They] were very surprised by my decision and said that I was crazy to do such a thing because they felt that women do not belong in the army,” she says. However, “they quickly changed their opinion once they saw how well I was doing.”

“Most of my girl friends,” she adds, “think it is very cool.”

Petty Officer Tõkke is one of an increasing number of young women who are voluntarily enrolling in Estonia’s conscription service, which is required for men, and then choosing to enter military service professionally.

With the world’s spotlight on the volatile situation in nearby Belarus, and the continuing fraught relations between the Balts and Moscow, the Estonian military appears to be embracing the shift in mindset among Estonia’s young women.

“Desire to contribute to the national defense” is the principal motive impelling the increasing number of women who are joining the Estonian defense forces, says Laura Toodu, a former conscript who now works for the Ministry of Defense, where she helps recruit female conscripts.

“They want to be there”

The Estonian military is built around a reserve army model where conscripts are trained for eight or 11 months, whereupon they become part of the reserve force that is called up in case of a national emergency. Active armed forces number around 6,000 troops, roughly half of whom are conscripts.

Conscription service is compulsory for Estonian men between the ages of 18 and 27. However women can also enlist if they wish. And an increasing number of young Estonian women do. This summer 46 Estonian women volunteered for the conscription service as part of the July “intake,” the most ever at one time. Not many, perhaps, for one of Estonia’s large NATO peers, but quite a few for a country of 1.3 million.

Also, this year over 50% of the women conscripts decided to join the regular army. At present there are 336 women serving in the active service of the EDF – about 10% of the 3,508 members. The Ministry of Defense would like to see more.

So would Sgt. 1st Class Kristo Pals of EDF’s Cyber Command. Sergeant Pals is also a national defense instructor at Tabasalu High School, outside Tallinn. Military education is offered in 75% of Estonian high schools.

Sergeant Pals makes no bones about the fact that he likes working with – as well as teaching – women as much as, if not more than, men. “I often find that the women, particularly the women I teach and serve with, are more responsible and mature than the men. What they lack in physical strength they make up in morale.”

Petty Officer Tõkke, who currently serves as a public affairs officer, agrees. “In my experience, Estonian women are very independent and perform their duties very well. The women who join the military are much more motivated than their male colleagues,” she says. “After all, they want to be there.”

Estonia is playing catch-up with some of its other NATO partners where women have been serving in front-line units for some time.

Although women have been allowed to join the conscription service since 2013, it was only in 2018 that a bill, signed by then-Defense Minister Jüri Luik, allowed women to apply for service in any branch.

At the same time the ministry undertook an accelerated recruitment program in order to draw more women to join the conscription service.

Now that effort is paying off in a wave of female conscripts, alongside a parallel one of female noncommissioned officers.

A changing society

Estonian society is also catching up with the female-friendly EDF. According to a survey of the general Estonian public taken in 2018, 50% of the respondents agreed that “women are not suited to fighting a war due to their nature and that national defense should remain a field for men.”

“There is definitely more work to be done educating the public that females are suitable for military service and that they are capable of serving alongside men,” concedes Helmuth Martin Reisner, a spokesman for the ministry. “Since the mainstreaming of women into the conscription service only began in earnest in 2018, this idea has not yet fully translated to the general population.”

Another factor in the changing complexion and morale of the EDF has been Russia’s aggressive moves, particularly its invasion of Georgia in 2008 and its recent involvement in the civil war between the Ukrainian government and separatist forces, which have boosted Estonia’s defense-mindedness.

According to a report last year nearly 79% of the general population, which includes a large Russian-speaking minority, would be in favor of “armed resistance if Estonia is attacked by any country,” the same percentage as the Estonians’ martial-minded cousins, the Finns. The Finns resisted the Soviet Union when it invaded in 1939.

“Georgia and the Ukraine were definitely a wake-up call for us,” says Ms. Toodu, who works closely with the new wave of female conscripts.

The reasons why women are interested in joining the military service are various. Some see it as a chance for self-development. “Others view it as a chance to get out of their comfort zone,” Ms. Toodu says. But the main reason is the desire to contribute to Estonia’s defense.

Sergeant Pals, the instructor, has no doubts about the combat-readiness of both the female conscripts and regular army soldiers – as well as the female high school students – he teaches and works with. “I hope one day to see a whole unit of women,” he says.

So would Sgt. Geitlin Täht, an infantry instructor with an all-male company. However, she insists, “Character is more important than gender.”

Difference-maker

Black women learn homeownership – from tool belt to closing the deal

This next story oughta be picked up as a TV show by the HGTV channel. A Baltimore nonprofit isn’t just teaching Black women DIY skills. It’s offering them the chance to buy derelict houses after they renovate them. I’d watch that over “House Hunters.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Buying your first house is a milestone for anyone. Quanshay Henderson not only worked through the financial part of the process, but also restored the house herself – all with the help of the nonprofit Black Women Build-Baltimore. The group trains women in the skilled trades and guides them to supportive resources to enable homeownership.

In a city of 16,000 vacant homes – the result of decades of job losses and population declines – founder Shelley Halstead says, “The cost to stabilize these houses is basically the same cost to tear them down. So let’s get into preservation instead of demolition.”

As with other communities in the United States, Black homeownership in Baltimore has a history of being suppressed by law and practice. Ms. Henderson, a graduate student working toward her second master’s degree, has examined old redlining maps and finds not much has changed. She says it can be heartbreaking to hear stories of disenfranchisement, asking, “What have we done collectively to address that? I see [Black Women Build] as a form of resistance to what has been … happening for generations in a neighborhood.”

Black women learn homeownership – from tool belt to closing the deal

Quanshay Henderson purchased a home in March – the first person in her family to do so. She’d been hesitant until then because it seemed like a financial trap.

But not only does Ms. Henderson now own her home; she’s also learned the practical skills to care for it and can help guide her eight siblings through financing, should any of them wish to buy a house. “I know a lot about it now,” she says, particularly since her closing was complicated by issues with the appraisal and the title company.

Ms. Henderson is the first “graduate” of Black Women Build-Baltimore, a homeownership and wealth-building nonprofit that trains women in the skilled trades through the process of restoring vacant houses. Founded in 2017 by Shelley Halstead, Black Women Build instructs trainees in the carpentry, electrical, and plumbing trades, while they work on homes they may later purchase. Financing can come through lenders that have established relationships with Black Women Build. Trainees don’t finish the program with a license in a trade, but they are equipped with skills that they can parlay into a construction job.

The organization is on schedule to complete three homes with its trainees this year. It’s a seemingly incremental but deliberate step to address the problem of empty buildings in the city. “In Baltimore they really love to demolish houses,” says Ms. Halstead, explaining that vast areas are being gutted, and much of it is historic architecture. Decades of job losses and population declines have left 16,000 vacant homes here. “There’s so much beauty being lost,” says Ms. Halstead.

“Critical” to urban regeneration

In Baltimore, as with other communities in the United States, Black homeownership has a history of being suppressed by law and practice. Yet “housing is seen as a platform for every other kind of programmatic path forward,” says Robert Fischer, co-director of the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development at Case Western Reserve University.

Where old homes are not torn down, a common strategy for neighborhoods with a high proportion of unused buildings has been to redevelop them for new people to move in, says Professor Fischer. “That has further disenfranchised the people that have been the long-standing residents of these neighborhoods.”

As a result, there’s a growing interest in redeveloping neighborhoods in such a way that the current residents can remain and thrive, he says.

Urban renewal has played an important – and at times, controversial – role in the U.S., explains Marc Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League. But “replacement housing – particularly in the form of high-rise housing for low-income tenants – has not been successful.” These “structures might in themselves be dehumanizing,” he writes in an email.

More promising, he says, are adaptive reuse strategies – like Black Women Build-Baltimore – that “bring life back to an area, financial resources back to the local marketplace, and safety back to the neighborhood.” Such strategies allow old homes “to become critical components of urban regeneration.”

Black Women Build was the culmination of Ms. Halstead’s winding path through a childhood in Iowa, to fighting wildfires in Oregon, to living in a commune in Belgium and on an ashram in India. She found her way back to the U.S., wanting to create communal living space for her friends, but she didn’t know how to build.

So she took a carpentry class at a community college, and then got a job as an electrician’s apprentice in Antarctica. After more than a decade as a union carpenter back in the U.S., she went to law school and had a brief stint working for a nonprofit in Washington, D.C. Ms. Halstead still found herself seeking ways to feel fulfilled.

She finally landed in Baltimore. “I really just found it a perfect place to put my skills together and begin Black Women Build,” she says. ”All those various experiences I’ve had really shaped how I think about building community, and the way that I wanted to do it.”

Spending time with people, sharing space, and learning together are integral to the Black Women Build approach. It “deepens a sense of community and common understanding of things,” she says. This begins with conversations as she works with trainees. As they discuss life experiences and challenges they’re working through, Ms. Halstead might share a referral to behavioral health therapists, for example, or encourage bringing a lunch from home as a healthier and cheaper option than buying it from the corner store.

But building homes isn’t all there is to the work in the neighborhood. Making the existing buildings livable and available to people already in the community is the other half, says Ms. Henderson.

In the Old West Baltimore Historic District, that means facing its history as a redlined neighborhood. A student at the University of Maryland School of Social Work earning her second master’s degree, Ms. Henderson has examined redlining maps, and she finds that not much has changed in the area. She says it can be heartbreaking to hear stories of disenfranchisement, asking, “What have we done collectively to address that? I see [Black Women Build] as a form of resistance to what has been ... happening for generations.”

Programs like Black Women Build-Baltimore, many with social justice in their platforms, point a path forward, says Dr. Fischer of Case Western Reserve. “The idea of finding a way to turn these properties and bring back homeownership in some of these neighborhoods is an antidote to an illness that we created in the 1930s for many distressed neighborhoods.”

Although potential funders always want to know how Black Women Build-Baltimore can be scaled, Ms. Halstead says that’s not her focus. “That’s not what I ever wanted to create. I want to ensure that the person I’m working with understands the house, understands how to take care of it, knows their neighbors, feels a part of ... the community in which they live, and [knows] what they want to bring to it.”

By interacting on a personal level with someone, you can find their strengths, she says, and help them channel those strengths into the work at hand. From learning trades, to modeling healthy eating, to talking about overcoming challenges, to financial literacy – Ms. Halstead works alongside each woman in the program, each step of the way. “It’s ... about [learning] how we came to be” through conversation, but it’s not prescribed, she says. “It’s really organic.”

Trainees work about 32 hours a week, for which Black Women Build provides an hourly stipend. Most women in the program are wage earners elsewhere; one leaves an hour early at 3 p.m. to work her job from 4 to 9 p.m.

It’s important that the women feel valued for taking the time to learn new skills, showing up, and “believing in a future where they’re going to be a part of something that’s actually bigger than themselves,” says Ms. Halstead. “Black women have more to offer ... than our sweat.”

Preservation vs. demolition

Her own convictions aside, persuading the city to hand over several abandoned houses to begin with rather than razing them was no small feat. To Ms. Halstead, it’s a no-brainer: “The cost to stabilize these houses is basically the same cost to tear them down. So let’s get into preservation instead of demolition.” It helped her credibility that she had received a Baltimore fellowship available to people seeking to use their professional and life skills to aid marginalized communities.

It may be difficult to fathom how people could one day want to live in abandoned neighborhoods again, but Ms. Halstead sees the potential. “These aren’t just wasted houses and wasted memories,” she says.

Even today, as the founder of a nonprofit with decades of experience in the trades, Ms. Halstead still faces bias and hostility. One tradesman told her she “needs a man around” the job site because men might not want to listen to her.

She remains unfazed. If someone doesn’t want to listen, she says, then it’s not the right job for them. But the concept of women’s empowerment is overused, Ms. Halstead says. It’s a matter of practicality. “I’m just like, ‘Why not? Why can’t she swing a hammer? Why can’t she tile the bathroom?’” Being skilled in the trades makes sense for women, she says. The pay is high, and learning the skills is a way to become self-sufficient. “I didn’t take a vow of poverty,” she says, “just because I am a Black woman.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct Ms. Halstead’s apprenticeship and the spelling of Ms. Robertson’s name.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Finding justice for Breonna Taylor

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Six months after Breonna Taylor was killed in a hail of police gunfire, a grand jury in Louisville, Kentucky, has issued indictments against one of the officers involved. The jury’s decision and the protests that followed in Louisville underscore an important point. While incidents of race-based injustice occur nationally, local solutions need to be found where each tragic incident occurs.

The inherent desire in communities to find trust, empathy, and respect for each other can drive demands for individual justice or structural reforms. Building deeper connections within the community is an essential step forward to lessen distrust and violence.

National calls for social justice are needed. Yet these days, with cellphones enabling bystanders to capture violent police encounters, those incidents can provoke raw emotions. Such perspectives often overlook the unique details of an incident.

In other cities dealing with recent police violence, reforms are either being sought or in place. This year’s nationwide pursuit of social justice has set many cities on a steep learning curve.

Finding justice for Breonna Taylor

Six months after Breonna Taylor was killed in a hail of police gunfire, a grand jury in Louisville, Kentucky, has issued indictments against one of the officers at the scene. The jury’s decision and the protests that followed in Louisville underscore an important point. While incidents of race-based injustice occur nationally, local solutions need to be found where each tragic incident occurs.

The inherent desire in communities to find trust, empathy, and respect for each other can drive demands for individual justice or structural reforms. Building deeper connections within the community is an essential step forward to lessen distrust and violence.

National calls for social justice are needed. Yet these days, with cellphones enabling bystanders to capture violent police encounters, those incidents can provoke raw emotions nationwide. Such outsider perspectives often overlook the unique details of an incident. Protest slogans haven’t always squared with what happened. Local communities are left to decide how to restore social harmony and pursue further justice.

In addition, what’s often overlooked is how people in cities like Louisville; Minneapolis; and Sacramento, California, are working closely together after a violent incident to close the gap between facts and perceptions, however difficult. They are trying to turn division into unity.

For many in Louisville, the indictments did not satisfy a desire to find justice for Ms. Taylor’s death. She was asleep when three officers broke through the door of her apartment shortly after midnight on March 13 to serve a “no knock” warrant on suspicion of drug dealing. Her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, fired a single shot from a gun he was licensed to own, wounding one of the officers in the leg. The police responded with more than 25 shots. Ten of those came from the gun of Detective Brett Hankison from a blind location in violation of department policy.

The grand jury indicted Mr. Hankison on three counts of wanton endangerment – not for firing into Ms. Taylor’s home, but because some of his bullets passed through walls into an adjacent apartment where a woman and her child were sleeping. Although Ms. Taylor was shot five times, the findings of three separate investigations showed the officers acted within the law.

In working with the grand jury, Kentucky’s attorney general, Daniel Cameron, said he tried to satisfy a demand for justice as best he could within the law because the boyfriend fired first. “The decision before my office as the special prosecutor in this case was not to decide if the loss of Ms. Taylor’s life was a tragedy. The answer to that question is unequivocally yes,” Mr. Cameron said. “My job as the special prosecutor in this case was to put emotions aside and investigate the facts to determine if criminal violations of state law [resulted] in the loss of Ms. Taylor’s life.”

As a result, Louisville is seeking other aspects of justice. The city's $12 million wrongful death settlement with Ms. Taylor’s family points to other potential avenues for longer-term change. That agreement was tied to police reforms meant to improve officers’ relationships with the communities they patrol. These include an early action warning system to identify officers who violate department regulations, a ban on “no knock” warrants like the one issued for the raid on Ms. Taylor’s residence, mandatory review of all warrants by a commanding officer, and use of body cameras.

In other cities dealing with recent police violence, similar reforms are either being sought or in place. In Minneapolis after the killing of George Floyd in May, five City Council members have proposed replacing the Police Department with a “Department of Community Safety & Violence Prevention.” In Aurora, Colorado, local leaders plan to ban police from lobbying governments. In Vermont, the Burlington Police Department adopted a community proposal to require officers to intervene to stop unprofessional conduct by a fellow officer. This year’s nationwide pursuit of social justice has set many cities on a steep learning curve.

In the sequence of events that killed Ms. Taylor, both the police and Mr. Walker used guns in a way that follows the conditioned responses of an increasingly armed society. Such impulses need new restraints, best nurtured within a local community where finding common ground is a strong instinct.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The ‘divine Us’ – a basis for unity

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kim Crooks Korinek

A sincere desire for greater unity and love among humanity is a natural expression of our spiritual nature. Seeing each other as brothers and sisters in God inspires in us the compassion and humility that can help bring this about.

The ‘divine Us’ – a basis for unity

Deep in thought on my porch, I hear wind chimes blending with the bells from a local church just blocks away. I’m feeling a fresh breeze, literally and figuratively.

Reading the news in the last few years, it’s seemed to me as if there are tectonic plates of thought moving and impacting every angle of the human experience. More recently, protests have ripped through our neighborhoods in regard to one of these issues, race. They have mostly been peaceful but sometimes violent.

But there’s a shift happening, and I’ve been looking for higher reference points of a diviner truth needed to secure a justice, equality, and peace that benefit one and all. Ibram X. Kendi – author, historian, and director and founder of Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research – hits on one such reference point, posting on Twitter: “I love. And because I love I resist. There have been many theories on what’s fueling the growing demonstrations against racism all over America, from small towns to large cities. Let me offer another one: Love. We love.”

Of course, people’s motives can vary widely, even within the same protest movement. But the Love that is God is a spiritual basis for a unity that brings lasting reform and progress. This infinite Love, whose nature is expressed in all of God’s children, instills hope and feeds us with courage to step up to a higher ideal, even when that means leaving our comfort zone.

As we learn more of God as Love, a clearer sense of everyone’s unity in the form of our common good, whose source is that divine Love, comes forth. Christian Science explains that God is infinite, and describes the nature of God through several Bible-based synonyms. Love is one of these synonyms; another is Mind, which the textbook of Christian Science defines as “the only I, or Us; ... the divine Principle, or God, of whom man is the full and perfect expression;...” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 591).

We are each the reflection, the very evidence, of divine Love. As we mentally rise to see ourselves spiritually in this way, we draw closer to the fulfillment of the two commandments Jesus reiterated: to love God and to love one another as ourselves. This points to the universal Principle of Love that Jesus demonstrated, in which we are all one with God and therefore with one another. We each reflect God, Love, Mind, the divine Us.

Recognizing the divine, healing Principle empowers us to uncover and denounce whatever isn’t rooted in Love, including prejudice and bigotry. It gives momentum to humility, compassion, and forgiveness. Such qualities are inherently ours as sons and daughters of “our Father which art in heaven,” as God is described in the Lord’s Prayer.

In the spiritual interpretation of this prayer found in Science and Health, the opening line is rendered as “Our Father-Mother God, all-harmonious” (p. 16). The one all-harmonious Father-Mother presents the timeless framework of our spiritual reality – we are all one, and we all share the same divine Parent.

This is a radical oneness. It does not mean mindless conformity to a religious or political dogma, nor a loss of individual identity. Instead, it urges an even wider acceptance of the diversity of Love’s infinite expression. The reflection of Love, divine light, has infinite facets. And we can delight in one another as the infinitely rich and varied children of God, finding in one another a greater sense of purpose and a deeper solidarity.

Unselfish prayer is never an isolated effort. One’s tireless desire for peace and yielding to divine Love contribute to a movement of thought that lets go of the weights of ignorance, hatred, and prejudice.

As our view of each other shifts from a limited material basis to a spiritual one, we see more tangibly the colorful, holy, and harmonious diversity of what we all represent: the unified reflection of the one God, Mind, the divine Us.

A message of love

Pandemic anthem

A look ahead

Thanks for reading our stories today. Check back in tomorrow for a story about birdsong. When urban streets were quieted by the pandemic, birds changed their tune.