- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Turmoil in D.C. and Georgia’s U.S. Senate results: A call for political grace?

Grace can be a hard quality to sustain, especially in American politics.

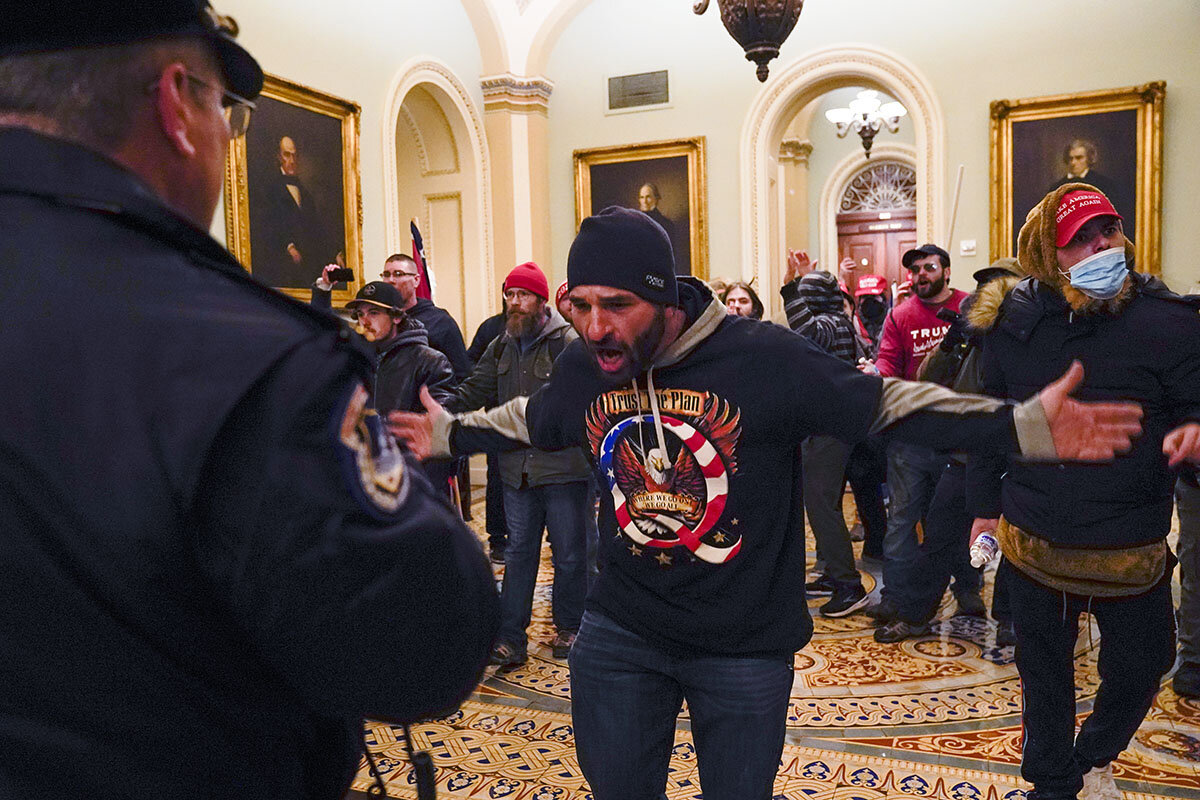

On the steps of the nation’s Capitol Wednesday, violent protesters battled police, storming the seat of representative government in a bid to disrupt the final step – counting electoral votes – before the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden.

Tear gas reportedly filled the Capitol rotunda, forcing members of Congress and the media to be evacuated just as members had begun discussing the Arizona vote in their chambers.

The Monitor’s Christa Case Bryant found herself next to Sen. John Hickenlooper of Colorado. “I asked him if he thought this crisis might help unify the Senate,” she told me by phone. “He said he’d just been discussing that with a colleague. As we all scurried out together, shoulder to shoulder, it struck me that a crisis of this magnitude might push the two parties to demonstrate some of the ideals of democracy they were just discussing in the chamber.”

Despite this violent protest, ultimately, effective governance, effective democracy, is about compromise. Arguably, Georgians just voted for their leaders to exercise restraint, respect, and inclusion.

When asked by NPR how he planned to serve all Georgians, not just those who voted for him, Democrat Raphael Warnock paraphrased Martin Luther King Jr.: “[King] said that we’re tied in a single garment of destiny, caught up in an inescapable network of mutuality, whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.” Senator-elect Warnock added that “we have to look out for one another.”

Grace in victory is easy. Grace in defeat is difficult. But even harder is grace in action. American voters expect that from their leadership. Stay tuned, we’ll have more coverage in tomorrow’s edition.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Is this America? A breach in peaceful transition of power.

Americans knew this would be a difficult day. But many were left to consider the state of the republic as they watched the violent climax of President Trump’s refusal to accept the election results play out on Capitol Hill.

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

The mob violence that rampaged through the U.S. Capitol Wednesday shattered stately doors and windows and trampled on the long-cherished national ideal that the United States of America is exceptional for its peaceful transition of governing power.

Rioters distinguished by red MAGA hats and waving Trump banners and Confederate battle flags swept past barricades and overwhelmed police in a sight some lawmakers said reminded them of war violence in distant lands, not Washington. The breach occurred just as the House and Senate had begun debating challenges to Electoral College votes, and forced both chambers into recess.

The U.S. has been riven by actual warfare in its past. But it is now 2021, not 1860, and the resurgence of some of the nation’s dark passions is a stark reminder that democracy and peaceful politics do not occur automatically, and must be cultivated and defended over and over again.

“It’s not that this is unprecedented, but for this generation, it feels new and like we’ve crossed the Rubicon,” says Theodore R. Johnson, a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Is this America? A breach in peaceful transition of power.

The mob violence that rampaged through the U.S. Capitol Wednesday shattered stately doors and windows and trampled on the long-cherished national ideal that the United States of America is exceptional for its peaceful transition of governing power.

Rioters distinguished by red MAGA hats and waving Trump banners and Confederate battle flags swept past barricades and overwhelmed police in a sight some lawmakers said reminded them of war violence in distant lands, not Washington. The breach occurred just as the House and Senate had begun debating challenges to Electoral College votes, and forced both chambers into recess.

The U.S. has been riven by actual warfare in its past. But it is now 2021, not 1860, and the resurgence of some of the nation’s dark passions is a stark reminder that democracy and peaceful politics do not occur automatically, and must be cultivated and defended over and over again.

“It’s not that this is unprecedented, but for this generation, it feels new and like we’ve crossed the Rubicon,” says Theodore R. Johnson, a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Gas masks and shots inside the Capitol

The incursion washed suddenly through a Capitol unprepared for an assault. Reporters and elected officials alike crawled under desks and hid in subterranean tunnels as law enforcement dispensed gas masks. Police fired tear gas in the Rotunda to try and force back the insurrection. Early reports indicated one person was shot in the melee, who was taken to a hospital and pronounced dead.

It was a shocking finale even for a presidency defined by the use of combustible rhetoric. President Donald Trump addressed supporters on the Ellipse prior to their explosion, continuing to falsely insist he had won the November election in a landslide and repeating baseless claims of Democratic voter fraud, which have been dismissed by his former attorney general, William Barr.

Moments before the Capitol’s windows began rattling, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the claims were untrue and that for Congress to overturn the results of the vote would “damage our Republic forever.”

Many of the rioters were white. The Proud Boys, a male-chauvinist organization with ties to white nationalism, were present in force at Wednesday’s Trump rally.

White supremacy may have been a component of the motivation for many in the crowd, says Mr. Johnson, though the full nature of the insurrection is yet unknown. In that sense it may have been driven by a desire to protect the privileges of a certain sector of society.

Hyperpartisanship and political polarization could also have fueled the mob’s rage. Political opponents are today too easily seen as enemies, as “others” who are an existential threat to the country.

“Politicians have tapped into this fervor and used it for political expedience,” says Mr. Johnson. “And the lack of principled leadership to walk a fickle and easily swayed public away from the ledge and accept their fellow Americans as fellow Americans and not as enemies is the story of the last five years.”

“These kinds of words have consequences”

In some respects, racialized violence has bracketed President Trump’s time in power.

The Unite the Right white supremacist rally of 2017 ended with the death of a counterprotester. The president said afterward that you had “people who were very fine people on both sides.”

President Trump’s response Wednesday to the Capitol riot was initially similarly respectful to the instigators, and continued to promote his unfounded election claims. He released a recording late Wednesday afternoon that said the election had been “stolen” and was a “landslide,” and said to those who had stormed the national Capitol, “You have to go home now. We have to have peace. We love you. You’re very special.”

Those who made up the mob may have heard those words as a structure of permission for their acts, or absolution.

“These kinds of words have consequences,” says Eric Foner, a Columbia University professor of history and renowned expert on Abraham Lincoln and Reconstruction.

Professor Foner says many Black Americans are not surprised by political violence, having been the target of past efforts to chill voting and otherwise deny them the rights of citizenship.

The only real parallel might be 1860 and Lincoln’s fears that the government might be overthrown, dooming the nation even as he took office.

“Violence is built into our political experience, although lately we haven’t quite seen this kind of thing,” Professor Foner says.

On Wednesday the entire Washington, D.C., National Guard was activated to help deal with the situation. It was unclear whether Congress would resume counting Electoral College votes, perhaps in more defensible circumstances, but a number of lawmakers expressed a desire to resume.

“Whatever it takes. These thugs are not running us off,” said Sen. Joe Manchin, Democrat of West Virginia.

President-elect Joe Biden, in remarks from Wilmington, Delaware, called on rioters to end their occupation of the House and Senate’s halls.

“This is not dissent. It’s chaos,” said Mr. Biden.

Mr. Biden, due to be inaugurated Jan. 20, called on President Trump to appear in person himself and denounce the occupation and call for his supporters to stand down. President Trump’s own words had helped cause the crisis, Mr. Biden suggested.

“At their best, the words of a president can inspire,” said Mr. Biden. “At their worst, they can incite.”

Global report

Pandemic opportunity? Pumping new life into cities

A team of our reporters looks at how cities worldwide are deftly responding to the needs of residents. When we look back, will we see the pandemic as an accelerator of creative solutions to long-standing urban problems, such as inequality?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

-

Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

-

Dominique Soguel Special correspondent

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

From Boston and Barcelona to Bogotá and Seoul, cities around the world have been “taking back” the streets from cars and returning them to pedestrians and cyclists. Although some of these moves were declared to be temporary in response to the pandemic, the sense is that once the world’s cities reemerge from a new wave of lockdowns, many of the changes will be here to stay – forever altering urban landscapes and lifestyles.

Yet as cities continue to change in response to the virus, many people are worried that the new initiatives could benefit some residents over others, exacerbating social and economic inequalities. Questions swirl, for instance, about which populations will be served by the new bike lanes, pedestrian areas, and space for sidewalk cafes – the affluent or low-income? Yet others see opportunity to close the divide between the haves and have-nots in this moment of reimagining.

As Elihu Rubin, a professor of urbanism, puts it: The built environment “can be a driver of racism and segregation, but it can also be our savior as it begins to suggest new modes of urban living.”

Pandemic opportunity? Pumping new life into cities

In Tel Aviv’s Florentine neighborhood, young people snack on bourekas and paninis as they relax at cafe tables placed at prudent social distances, occupying the same asphalt where cars once sped by or created clouds of exhaust in their search for parking. Blocking vehicles from the road are gray metal bollards that now stand as inanimate guards.

In Paris, 31 miles of “coronavirus cycling lanes” have been introduced since COVID-19 hit, designed to relieve pressure on public transport as the city exited lockdown. Mayor Anne Hidalgo promises that the bike lanes will become permanent.

In Oakland, California, officials have launched a “slow streets” initiative that has designated 21 miles of urban roadway for residents to use for safe-distancing as they walk, jog, and use wheelchairs, as well as bike.

From Boston and Barcelona to Bogotá and Seoul, cities around the world have responded to the pandemic with an accelerated “taking back” of streets from cars and returning them to pedestrians and cyclists. Although some of these moves were declared to be temporary, they have faced little pushback, and the sense is that once the world’s cities reemerge from a new wave of pandemic lockdowns, many of the changes will be here to stay – forever altering urban landscapes and lifestyles.

Urban planners are exploring other innovations, too, that are more unconventional and far-reaching. Seizing on the moment to redesign how people use space, they are looking at such things as turning suddenly empty office buildings into badly needed residential spaces; rezoning so that work, leisure, and school can be within easy reach, creating self-contained neighborhoods that are their own “15-minute cities”; and reimagining park space to link long-isolated neighborhoods.

Some of these innovations are already changing people’s lives. In New York City, where 100 miles of road were made into open streets for pedestrians and cyclists to use, Alexandra Nye is reveling in her walks and bike commutes down 34th Avenue in her Queens neighborhood.

“This neighborhood has only one proper park, and for how densely populated we were, we were always on top of each other,” says Ms. Nye, a librarian. “But now I see kids learning how to ride bikes, people doing Zumba, yoga, and I’ve even seen a book club meet on the street.”

Yet as cities continue to change in response to the virus, many people are worried that the new initiatives could benefit some residents over others, exacerbating social and economic inequalities. Questions swirl, for instance, about which populations will be served by the new bike lanes, pedestrian areas, and space for sidewalk cafes – the affluent or low-income?

But here, too, the pandemic is leading to changes that could ease divides. In Oakland, for example, city officials and local residents are launching an initiative in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods called “essential places.” By slowing or diverting cars with cones and signs, it aims to help pedestrians in those communities safely reach places such as grocery stores and health clinics that are located along heavily trafficked roadways.

Throughout history cities have survived wars, natural disasters, and plagues and often come through better at the end of them. Now, planners say, the pandemic offers an opportunity for urban areas around the world to reinvent themselves in a way that transforms both the sociology and livability of cities.

“I say start taking cities back from cars, start developing a new set of expectations,” says Elihu Rubin, a professor of urbanism at Yale University’s School of Architecture in New Haven, Connecticut. “This is the power the built environment has to shape our expectations. It can be a driver of racism and segregation, but it can also be our savior as it begins to suggest new modes of urban living.”

“COVID has woken everyone up”

Donte Gibbs, a community activist from East Cleveland, a majority Black city that is one of Ohio’s poorest, is encouraged by the conversations he is taking part in.

“It’s overwhelming, and so much is happening at once, and light is being shined on all the inequity,” he says.

Mr. Gibbs is already beginning to see results, including cheaper bus fares, free Wi-Fi on buses, and the fast-tracking of funding for community philanthropic projects. He attributes all of them to the pandemic.

That’s because COVID-19 has laid bare that systemic inequalities in cities are not just immoral, but unhealthy for individuals and broader society, says Dr. Rubin.

Deborah Gray agrees. The retired secretary spends much of her time at City Council meetings and public bus hearings advocating for residents from her mostly Black neighborhood in Cleveland, where she sees up close the impact of rising unemployment, shabby housing, and the threat of evictions.

“The urban community has to be treated equally and get the financial help needed to rebuild our areas, to make these areas as comfortable as anywhere else,” says Ms. Gray. As essential needs, she cites better-maintained housing, newer and better buses, and more bus routes to help local residents.

When people, she says, “don’t see investment, they think they don’t have a voice.”

Conversely, Ms. Gray says, when her neighbors see the added bike lanes and widened sidewalks in their neighborhood, and increased support for disadvantaged people through newly available telemedicine and social services online, it galvanizes them to care more, too.

“COVID has woken everyone up,” she says. “It’s a call for everyone to move forward and figure out how we can work together and make it better for everyone – those in the urban community and those who are comfortable.”

Make way for bikes

Toronto, Canada’s largest city, has an extensive public transit system, but people here still love their cars. Megahighways feed into the city; multilane roads traverse it.

Advocates for safer streets for pedestrians and bicyclists have long fought for more space. But it took the pandemic to get officials to summon the political will to back them. Within weeks of the coronavirus hitting last spring, Toronto’s City Council approved an additional 25 miles of bike lanes across the city.

One of the most popular bicycle routes on summer and fall weekends was Lakeshore Boulevard, which traces the southern edge of the city, along Lake Ontario. But to really transform habits and help enable safe transportation, Jennifer Keesmaat, the city’s former chief planner, says a network of bike routes must be created across the city, connecting the most marginalized neighborhoods to the most upscale ones, as well as to the main business and cultural centers.

“There’s been this perception that cycling is somehow this elite activity, and it’s actually not. It’s the most accessible and equitable way for people to move around the city, but only if you put the safe cycling infrastructure in place,” she says. “What I’m interested in is mobility everywhere to everywhere. ... This is the future of cities, not retreating back into planning for cars and designing cities for cars.”

In Paris, advocates credit the emergence of a biking network there with the increase and diversification of bike users. “We had bikeable stretches, but we didn’t have a network,” says Louis Belenfant, president of Vélo Île-de-France, a bicycle activist group. “In the span of a few weeks, we saw the emergence of biking lanes that are visible, safe, and separate from car traffic.”

But access remains uneven across the metropolitan area, particularly in the less affluent suburbs. Many say the way forward must include “tactical urbanism” – creating light, adjustable, and low-cost infrastructure (like bike lanes or pedestrian streets) to test what concepts work, rather than spending a massive amount of money and committing to something that can’t be adapted.

Such changes can often be done relatively quickly and cheaply and usually don’t involve extensive permitting.

“One of the major hindrances to really ambitious policies in cities until now has been politicians being worried about the backlash of doing anything against cars,” says Audrey de Nazelle, an expert at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London.

Mayor Hidalgo, who was reelected in June, “has finally proven that really ambitious policies don’t necessarily mean that you get turned out by voters,” she says. “It pays off to be brave.”

Critics of the mayor argued that her anti-car policies were detrimental to suburban residents, but ultimately it was not an issue that gained huge traction. During her first term, Ms. Hidalgo added hundreds of miles of bicycle lanes to Paris, including along the iconic Champs-Élysées. The car lobby’s legal challenge against the pedestrianization of the Seine – another one of her projects – also ultimately failed.

In a sign of growing acceptance of getting around Paris by foot or on bike, the city declared a “car-free” day in September.

The promise of “slow streets”

Across the Atlantic, Latin America has historically been one of the most unequal regions in the world, and there are worries that economic progress made in recent decades could be wiped out because of the pandemic.

Yet in parts of the region, officials are taking steps to reclaim streets for residents as they are in other cities around the world. In Bogotá, Colombia, one of the world’s most congested cities, the urban planning response to COVID-19 has included adding temporary bike lanes, many of them taken from car lanes. That move has served as a reminder that “the streets and sidewalks are public space that belong to everyone,” says Guillermo Penalosa, a former commissioner of parks, sports, and recreation in Bogotá who now runs 8 80 Cities, a nongovernmental organization that encourages urban planning policies that benefit people of all ages.

“We gave up a huge part of our cities not even to moving cars, but prioritizing parked cars over people walking or sitting and chatting. That’s a big benefit of how cities are dealing with the crisis: They’re reclaiming public spaces.”

In many cases, the changes being implemented in cities aren’t all that radical. One example is the “slow streets” initiative in Oakland, California, part of a global movement in which city officials are setting aside streets for pedestrian-friendly uses.

Some of the innovations echo what happened in earlier eras, when cities were forced to adapt to crises. William Gilchrist, Oakland’s planning and building director, cites the introduction of closed sewage systems and green spaces such as New York City’s Central Park, which were created in response to the crowding of 19th-century cities and the diseases it helped spread.

But, he cautions, cities should not just institute reforms willy-nilly. He urges them to figure out what works – and fosters health and social equity.

One potential challenge to closing disparities among urban residents is that so many affluent people have decamped either temporarily or permanently to other locations. It’s the wealthier class that injects much of the capital and jobs, as well as philanthropic money, into local economies, which is more important than ever now that there is less largesse for government programs.

Driving this exodus is the population density that has been blamed for playing a role in the spread of COVID-19. But public health experts say density is not inherently problematic on its own, especially if mask wearing and social distancing are followed.

Similarly, mass transit systems have taken a major hit during the pandemic, as residents – many in lockdown, others worried about the dangers of crowding – have stopped taking buses, trains, and ferries. In some cases, public transit systems have been temporarily closed.

But here, too, many experts believe that the concerns are misplaced. They argue that public transportation systems, which are the only way for many residents to get around, are safe if proper precautions are taken.

Indeed, urban planners like Dr. Rubin believe that now is the time to take advantage of fewer commuters on the road to build the infrastructure needed to improve mass transit for urban residents. This might include seizing road space for dedicated bus lanes. It could mean putting in bus islands or raised sidewalks at bus stops.

Galvanizing the political will to pay for such changes, of course, will be a challenge – especially since many transit agencies are strapped for funds because of the drop in ridership.

But what is different now, some advocates say, is that the pandemic has reminded everyone how important public transportation is, especially to certain urban populations who rely on it to reach their jobs.

Rethinking neighborhoods

Longer term, the pandemic could accelerate a more fundamental reshaping of cities around the world. Paris, for example, has been exploring the concept of the “15-minute city” where everything is within quick reach by bicycle or on foot.

This means moving away from the traditional divide of cities into residential versus professional and commercial areas. Instead, there would be shops, job-providing businesses, housing, and schools all within a commute-free radius.

It was one of the ideas on which Mayor Hidalgo won reelection. In light of the push COVID-19 gave to the trend of remote working, the concept is gaining interest in other parts of the globe, including in Toronto.

“It is really about ... changing how we use land in cities, precisely because we learned through COVID-19 that our neighborhoods are really powerful and important places for everyday life when we design them right,” says Ms. Keesmaat, Toronto’s former city planner.

As city economies slow down because of the pandemic, there’s an opportunity to pivot to community-based planning and away from a dependence on private developers, some planners say. This can give neighborhoods more of a voice in articulating what cities should do with public spaces, parks, transit, and affordable housing.

In Oakland, Mr. Gilchrist, the planning director, is discussing how buildings can have a range of uses over time – like making commercial space into housing given the dynamic of remote work. He credits the city’s tradition of community-civic partnership in helping think creatively now.

The Colombian city of Medellín may hold some secrets for moving ahead after the pandemic. In the early 1990s, it was the most dangerous city in the world, essentially ruled by drug traffickers. Citizens had all but abandoned the idea of communal, public space.

But by 2003, people outside government, such as former academics and members of civil society, started working closely with the new mayor’s office. For the first time in decades it led to partnerships between the government, businesses, think tanks, and the public. Creative ideas surfaced on how to bring the city together.

Among the results were urban planning projects like cable cars integrated into the metro system to connect poor, forgotten neighborhoods with the rest of the city. Social projects went hand-in-hand with architecture and city planning.

Alejandro Echeverri, director of the center for urban and environmental studies at EAFIT University in Medellín, played a central role in the city’s revitalization.

And he sees promise in this crisis, too. “There will be a lot of space for opportunity,” he says.

War in Afghanistan: What has NATO learned from 20 years of fighting?

The war in Afghanistan appears to be drawing to a close. Our reporter asks: What has NATO learned from this experience?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan reaches the two-decade mark this year, NATO officials have made clear that they have bigger fish to fry. In the alliance’s new Strategy 2030 report, Afghanistan is mentioned just six times.

Yet as NATO positions itself for the next decade, the alliance has been transformed by its experience in Afghanistan and the lessons it learned there.

The cooperation of the 50-plus nations involved was a growth experience for the alliance, says Ian Lesser, executive director of the German Marshall Fund in Brussels. The bloc “learned a lot ... in terms of habits of cooperation and interoperability that were tested everyday.” Member forces also made use of some high-tech systems that many nations wouldn’t have been exposed to in peacetime.

The alliance's lessons in Afghanistan may be in recognizing the corrosive effects of corruption – and the ways in which the U.S. and its NATO allies inadvertently encouraged it, says retired Col. John Agoglia.

The billions of dollars that flooded into Afghanistan after the invasion made graft commonplace. “We need to understand how we put money into an environment – who we’re giving it to, what are the oversight mechanisms?”

War in Afghanistan: What has NATO learned from 20 years of fighting?

As America’s longest war reaches the two-decade mark this year, one of President-elect Joe Biden’s first orders of business will be figuring out a way forward in Afghanistan – and, by extension, a roadmap for NATO’s mission in the country.

Neither the Taliban nor Al Qaeda is at the top of America’s national security threat list anymore, and NATO officials, too, have been clear about their belief that they have bigger fish to fry. In the alliance’s new Strategy 2030 report, Afghanistan is mentioned just six times in 40 densely-packed pages.

The war in Afghanistan is a mission on which the success or failure of NATO was once thought to hinge. In its early days, the war was billed as not only a post-Cold War rebirth of the alliance, but also its 21st-century evolution.

No longer. The new security agenda, according to the report, will be dominated by “competing great powers, in which assertive authoritarian states with revisionist foreign policy agendas” – in other words, China and Russia – “seek to expand their power and influence.”

Yet as NATO prepares for the next decade, its challenges will be tackled by an alliance transformed, for better or worse, by its experience in Afghanistan and the lessons it has learned there. The question, analysts say, will be whether it chooses to heed them.

“Habits of cooperation and interoperability”

Afghanistan became NATO’s marquee mission with the U.S. invasion in 2001, the first time in history that the alliance invoked Article V, which declares that an attack on one is an attack on all. The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was ultimately composed of allies from 50-plus countries, including non-NATO partners.

In the early years of the war, the running joke among U.S. forces, however, was that ISAF stood for “I saw Americans fight,” or “I sunbathed at FOBs” (forward operating bases, which are heavily fortified and largely safe). The underlying critique was that some allied governments used restrictions called “caveats” to prevent their troops from carrying out night missions, for example, or from deploying to certain more violent parts of the country – and, as a result, U.S. and other fighting forces carried a heavier load.

Still, the cooperation was a growth experience for the alliance, says Ian Lesser, executive director of the German Marshall Fund in Brussels. “These caveats did in some ways hinder the ISAF’s ability to operate, but it operated nonetheless, and learned a lot by that in terms of habits of cooperation and interoperability that were tested everyday.”

At the same time, the experience transformed the militaries of many NATO member nations. In Germany, some 90,000 troops have deployed to Afghanistan over the years. “There’s no German general today who doesn’t have military or even fighting experience there,” says Markus Kaim, senior fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. The same goes, too, for a generation of soldiers in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and Canada.

Member forces grew accustomed to collaborating on intelligence sharing and mission planning that made use of some high-tech systems that many nations wouldn’t have been exposed to in peacetime, says Anthony Cordesman, defense analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This in turn, led to a “much better appreciation for allied capabilities.”

And it led to an even greater appreciation for allies themselves – including non-NATO partners, many of whom, like Australia and South Korea, took part in the Afghanistan war.

“If we think about any military engagement of NATO going forward, we’ll conceptualize it not as 30 member countries of NATO, but as a loose platform” that includes other organizations and non-NATO partners as well, Dr. Kaim says. “NATO needs partners,” he says, because “NATO is aware that it can’t shy away from deep political changes we’re seeing.”

The NATO 2030 report emphasizes making the bloc a “more political alliance,” which means making it a “place where core security concerns of all sorts are discussed,” Dr. Lesser says. The Asia-Pacific region, especially China, is a case in point. “It’s a recognition that the definition of what bears on Euro-Atlantic security has expanded tremendously.”

“The right thing to do for NATO”

This focus on great power competition, coupled with the varying levels of disenchantment with missions that don’t end cleanly, means that the appetite for launching military operations again anytime soon will differ across the alliance.

It starts with the question of whether NATO members consider Afghanistan a success. “Was it worth all the effort, the blood? Most people would likely answer ‘not really,’” Dr. Kaim says. Militarily, an alliance with impressive weapons uprooted Al Qaeda but did not defeat the Taliban, which, though an effective guerrilla force, was never a highly sophisticated threat. On the nation-building front, “You spent an incredible amount of money to achieve remarkably little,” Dr. Cordesman says.

Yet the definition of success itself reflects the different strategic cultures within NATO. While America is deeply uncomfortable with the notion of not winning, for many NATO allies, analysts say, it was enough to show solidarity, to be present, and to make a contribution.

More broadly, Afghanistan was seen as “the price to pay, and the right thing to do for NATO in return for the reassurance those countries get from the alliance on the bigger existential threats they face,” Dr. Lesser says. “The fact that they’ve been present in Afghanistan is simply part of the insurance policy, and you have to pay these premiums over time.”

And even as most members came out of their Afghan experience “more cautious about exporting democracy,” the 2030 report acknowledges, it also argues that it’s nonetheless “vital” that NATO doesn’t allow democratic “erosion.”

The causes and costs of corruption

For this to happen, NATO must take some key lessons of Afghanistan, including the corrosive effects of corruption – and the ways in which the U.S. and its NATO allies may inadvertently encourage it, says retired Col. John Agoglia, former director of both the U.S. Army’s Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute and the Counterinsurgency Training Center-Afghanistan, both in Kabul.

The billions of free-flowing Western dollars that flooded into Afghanistan after the invasion made graft and fraud easy and commonplace. “We need to understand how we put money into an environment – who we’re giving it to, what are the oversight mechanisms? What could be the second and third order impacts?”

Corruption "undermined the legitimacy of the Afghan government, reduced its effectiveness, and created a source of resentment for its own population," which in turn drove Taliban recruitment and made it "much more difficult" for NATO to achieve its key mission goals, "from security to effective governance," Karolina MacLachlan, policy officer at Transparency International in London, wrote in NATO Review.

At the same time, in bolstering some former Soviet republics to help resist Russian democratic undercutting and influence, as in Afghanistan, “we may have to deal with some people who have blood on their hands, some who are corrupt, some who are trying to reform,” Colonel Agoglia says. “We’ve learned a lot about understanding the limits of power, how to shape it as best you can, and how to take what you can get – and it’s not always going to look pretty.”

“I get the great power competition, but it’s won and lost in the trenches doing these things – so that if you actually do have to go into combat,” he adds, “you own the day.”

Pandemic education: How Jordan’s tech platform bridges divisions

Here’s another story about how a creative response to the pandemic – in this case, remote learning – may help bridge the divide between haves and have-nots. Could Jordan be a model for other countries?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Last March, Jordan switched to distance learning for its 2.5 million K-12 students, using an online learning program developed by a local tech company. Its platform is the most extensive in the Arab world, where many countries have relied on televised lessons during the pandemic.

Since schools remain shut in Jordan, educators are expanding distance learning for the long haul, adding new features that include a chat interface. The platform allows smartphone users to log on without paying for data. It’s been supplemented by activity books and printed coursework distributed weekly at schools.

Jordan also airs daily lessons on local television channels that are taught by prominent teachers who most students would not otherwise encounter. This has had a leveling effect in an education system that spans deep divisions between urban and rural, and public and private. Some educators are hopeful that this outreach to less-advantaged students can continue post-pandemic.

“There is no way I would have access to these teachers in my life,” says Yazid, a teenager who credits one of these teachers’ televised lessons for helping him to finally crack the physics section in his university placement exam.

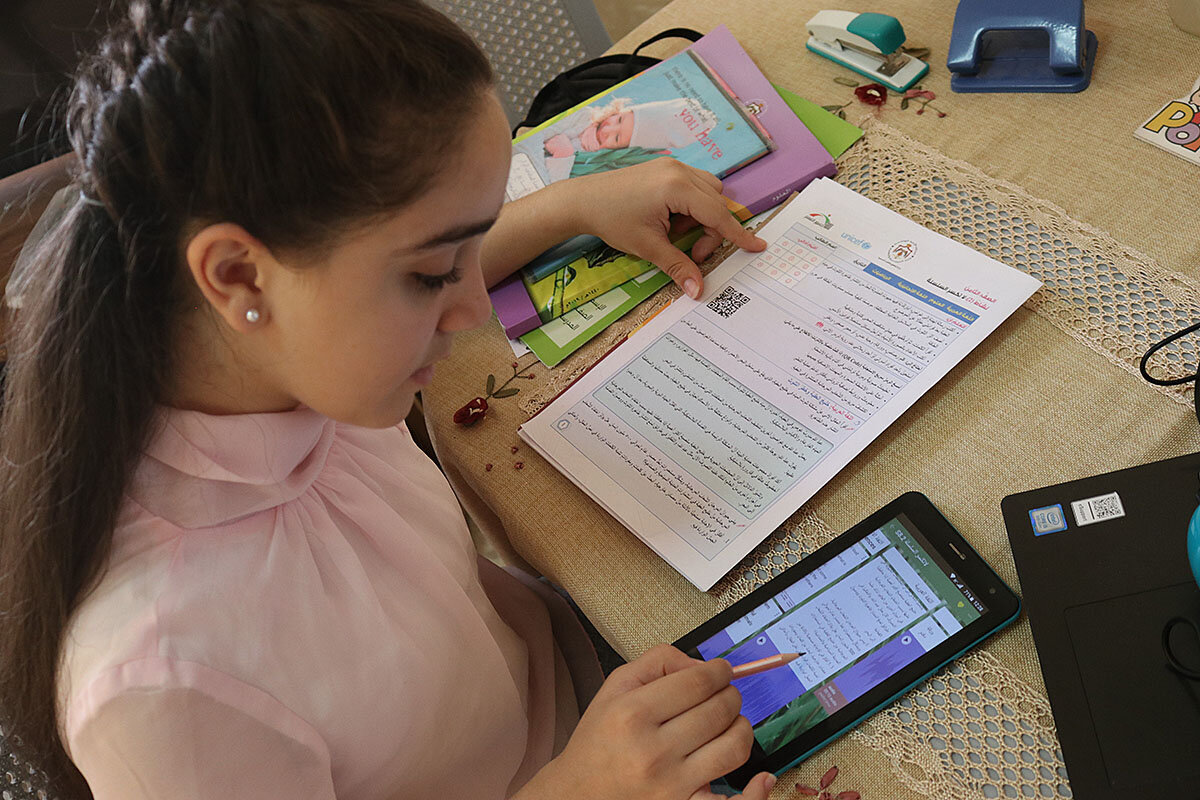

Pandemic education: How Jordan’s tech platform bridges divisions

Sama Abu Omar knows the drill.

At 8:00 a.m. sharp, the 13-year-old settles into the desk pushed against one wall in her family’s cramped living room which is plastered with her colored motivational notecards. She puts on her headphones, fires up her newly-purchased Chinese-made tablet and begins scribbling notes while watching a video lecture.

A few months ago, Sama didn’t have the internet at home; the tablet cost her two years of savings. “School is my entire life,” she says. Online learning “is the only way to keep the spirit of studying alive. For a while, without it, I was lost.”

Education has long been a priority in resource-poor Jordan. The country has near universal access to education in grades one through 12, the highest percentage of university-educated women in the region, a 99% literacy rate, and a highly skilled workforce. But its educational resources are spread unevenly: Schools in villages and camps often lack heating and basic materials. Now, Jordan is showing the region a path to bridging learning gaps without deep pockets or vast manpower.

When COVID-19 first began spreading, emptying classrooms around the world, Jordan was one of the first countries in this region to switch in March to distance learning for its 2.5 million K-12 students. Within a week, it had rolled out an online learning program by partnering with a local tech company. Its platform has become the most extensive in the Arab world, where many countries have relied on televised lessons for at-home learning.

Jordanian educators are now working to make blended online learning a permanent pillar of a more open educational system. Schools remain shut here, and it’s unclear when in-class learning can resume, so educators are expanding distance learning for the long haul, adding new features that include a chat interface and teacher-set quizzes and exams. The platform also offers non-core programs such as arts and music.

“We are trying to tailor the experience to each student’s individual learning pathway,” says Mohammad Jaber, founder of Mawdoo3, the Jordanian start-up that created Darsak (Arabic for “your lesson”). “We are going beyond simply making sure learning is not interrupted to re-creating a full classroom experience as much as we can.”

Education officials say the pandemic has helped them to “think differently, be creative, communicate, and collaborate.”

“We have gone from addressing connectivity issues to sustainability, because this is a new learning tool that will benefit our students in the long term after the pandemic,” says Raed Alawiya, an Education Ministry official who is overseeing distance learning.

No phone plan, no problem

When the government tasked Mawdoo3 to design an education platform in a matter of days, its stipulation was for it to be smartphone friendly and to use White Space, a technology that allows phone users to access the internet without the need for data or even a phone plan.

Crucially, Jordanian officials recorded and broadcast daily lessons on local television channels for families with no or limited devices. Each day prominent teachers and experts broadcast a lesson for each grade in the four core subjects: math, science, English, and Arabic.

The data-free access to remote classes was a godsend for many families like Sama’s, who would otherwise use up their monthly phone data package within days.

The benefits of this revamped online platform were unevenly distributed. Prior to COVID-19, 16% of students in Jordan reported not having internet access at home; one-third didn’t have a computer for schoolwork, according to the World Bank. Around 1 in 6 students never logged into Darsak during the spring semester, according to the Education Ministry.

The government is using log-in data to improve access for all students by using foreign funding to provide free devices and boost network connectivity. This has led to higher log-in rates: 70 million in September, compared to 20 million over the spring semester.

Samer Bashir, 11, and his family live in a village outside the southern town of Karak with an unreliable internet connection. COVID-19 lockdowns in the spring and summer prevented them from traveling to relatives’ homes with better connections. Today, they drive to a nearby village each early afternoon so that Samer can upload his homework.

“I never thought my son’s future would depend on a Wi-Fi signal,” says Abu Mohammed, Samer’s father.

Free-to-air lessons

With free internet access and TV broadcasts, students are accessing the same material and lessons as their peers in affluent private schools who were used to being taught by the country’s top teachers. Now those teachers are on air and online, free to watch.

As in many countries, Jordan’s education system features wide disparities in school facilities, resources, and class sizes between those in rich and poor urban districts, and between cities and remote villages, desert settlements, and Syrian and Palestinian refugee camps.

Saddam Dababseh, a 4th-grade science teacher at a West Amman public school, is one of dozens of educators who teaches his own students virtually while also recording lessons for television and online.

“I have learned to go at a deliberate pace and make the material accessible for students of different abilities and pace across the country,” says Mr. Dababseh. “Instead of a single class, I am teaching an entire country and I have to make sure no one gets left behind.”

Students, and even some parents, have latched on to charismatic K-12 teachers renowned in physics, math, and English, and are now following their lessons on YouTube.

“There is no way I would have access to these teachers in my life,” says Yazid, Sama’s 17-year-old brother, who credits one of these teachers’ televised lessons for helping him to finally crack the physics section in his university-placement exam.

Surra Hamadah, a 4th-grade Arabic teacher in a working-class Amman neighborhood and an online instructor, says educators have become more involved in students’ learning outside class. For example, she has helped several students obtain free smartphones and laptops from the Education Ministry.

“Before, when students left the classroom, our contact with them was cut until the next day,” she says. “Now we are connected to help students and their guardians overcome learning obstacles at home.”

Printed coursework closes a gap

Jordan’s distance learning has relied on videotaped lectures that aren’t always that engaging and can be hard for students with reading or listening comprehension difficulties to absorb.

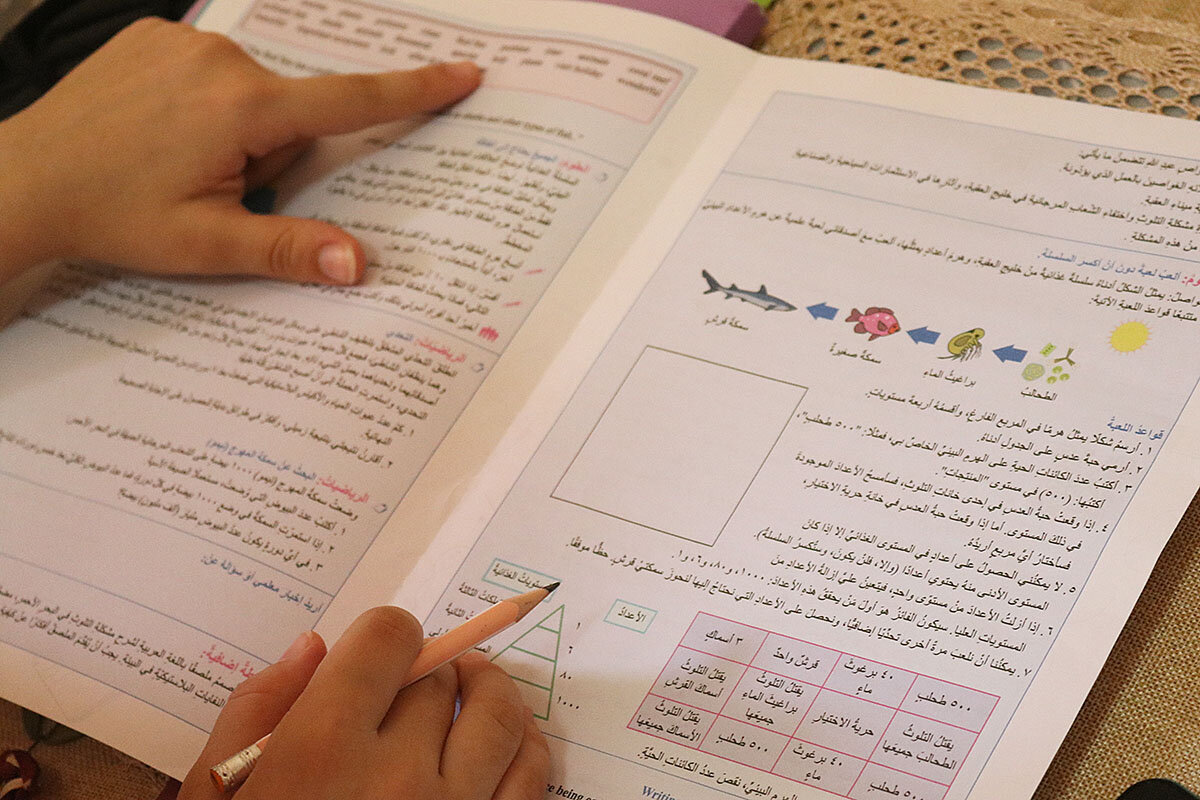

In order to reach students who struggle to engage with the Darsak platform, UNICEF and Jordanian educators have developed Learning Bridges, supplemental activity books and printed coursework distributed weekly at schools that provide an interactive experience for homebound students.

“We needed to find ways to engage students who cannot connect to Darsak or weren’t engaged by Darsak,” says Gemma Wilson-Clark, chief of education at UNICEF Jordan. “Because, let’s be honest, recording a lecture for a student is not always going to excite an 11-year-old.”

Combining math, biology, reading comprehension, English, and Arabic, the extra materials include activities and puzzles. For students with access to smartphones, there are QR codes that open to a portal with videos, tips, graphics, and audio instructions for the week’s lesson.

“Having a piece of paper in between my hands allows me to take it to my parents and ask them questions, or take notes in the margins,” Sama says as she holds up her Learning Bridges workbook.

“I like having resources and videos, but I also miss the classroom,” she says. “I hope after the virus we can have both.”

Essay

Moments of stillness, in a city of millions

Mexico City is a place where you’re never alone – or it used to be, before social distancing set in. The stillness is jarring, our reporter writes, but maybe it’s what’s needed now.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

When I moved to Mexico City in 2014, my husband and I spent most of our free time exploring the megacity of 20 million. We squeezed our way through massive crowds of religious pilgrims. We spent hours in crowded fruit and vegetable markets, looking for the perfect mango milkshake. Once our two children were born, we spent more time at playgrounds. The idea of being alone was laughable.

Now our lives have moved increasingly indoors. We avoid the still-crowded restaurants and city plazas. Sometimes the walls of our home/office/preschool/zoo feel as though they’re closing in on us.

Except on weekends. On a recent morning, we drove about 30 minutes to Los Dinamos, a vast, mountainous, densely forested national park – officially within the capital’s city limits.

I listened to the sound of rushing water from the river below and the twittering of birds hidden in the pine branches above. I held the tiny hand of our excited toddler. And then I realized with a jolt: We’re alone.

I often tell people what I miss most about pre-pandemic life is the buzz of the city. I miss street food, and mariachi serenades at a busy cafe. But that may not be true: Yes, I miss the bustle, but I’m not sure it’s what I need right now. I need these walks on pine-needle-covered trails. I need to breathe truly fresh air. I need to be with my family – even as I miss my parents, siblings, and friends immensely – in the heart of a forest on the edge of a megacity. It reminds me that there’s life all around me, even if I can’t spend time mixing with others.

Moments of stillness, in a city of millions

A few weekends ago my family and I hopped in the car for an adventure. This has become our Sunday routine over the past several months of the pandemic, with our former weekend rituals nothing more than distant memories.

When I moved to Mexico City in 2014, my husband and I spent most of our free time exploring the megacity of 20 million. We squeezed our way through massive crowds that had traveled across the country to pray to the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s patron saint. We spent hours in crowded fruit and vegetable markets, looking for the perfect mango milkshake or vendors selling the most interesting-sounding mole mix.

Once our two children were born, we made more stops at nearby parks, catching up with friends on the playground or testing out new flavors of paletas, delicious artisanal popsicles.

The idea of being alone was laughable: I remember once looking out my office window, pre-pandemic, and not seeing a single person on the block. I recall it vividly because it seemed utterly apocalyptic – and it never happened again.

Over the past nine months, our lives have moved increasingly indoors. We avoid the still-crowded restaurants and city plazas. Sometimes the walls of our home/office/preschool/zoo feel as though they’re closing in on us.

Except on weekends. On a recent morning, we drove about 30 minutes to Los Dinamos, a vast, mountainous, densely forested national park – officially within the capital’s city limits. Despite Mexico City’s reputation as a crowded, bustling megalopolis, there are a handful of mountain refuges and hikes less than an hour away. This particular Sunday was a foggy, rainy day, but the sun peeked out every once in a while, and the cover of the tall pine trees kept us dry.

A few minutes into our walk, my eyes followed the muddy, rocky path until it turned a green corner in the distance. I listened to the sound of rushing water from the river below (the park used to be a series of hydroelectric plants) and the twittering of birds hidden in the branches above. I held the tiny hand of our excited toddler, eager to get a week’s worth of wiggles out. And then I realized with a jolt: We’re alone. In a city of millions where a quiet night is punctuated with sounds of tamale or sweet-potato vendors stalking the streets with their high-pitched whistles or recorded sales pitches, we had transported ourselves into another realm.

I often tell people what I miss most about pre-pandemic life is the buzz of the city. I miss street food, and mariachi serenades while I’m in a busy cafe sipping my morning coffee.

But I’ve come to realize that my sentiment’s not entirely true. Yes, I miss the hustle and bustle, but I’m not sure it’s what I need right now. I need these walks on pine-needle-covered trails with my young daughters, exploring the decomposing tree trunks or calling out the colors of the flowers we pass along the way. I need to breathe in truly fresh air; I need to lure my kids (and my husband) ahead with promises of snacks and perfect picnic spots.

I need to be with my family – even as I miss my parents, siblings, and friends immensely – in the heart of a forest on the edge of a megacity in the midst of a pandemic.

It’s a reminder that there’s life all around me, even if I can’t spend time mixing with others.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Responding to a cyber Pearl Harbor

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

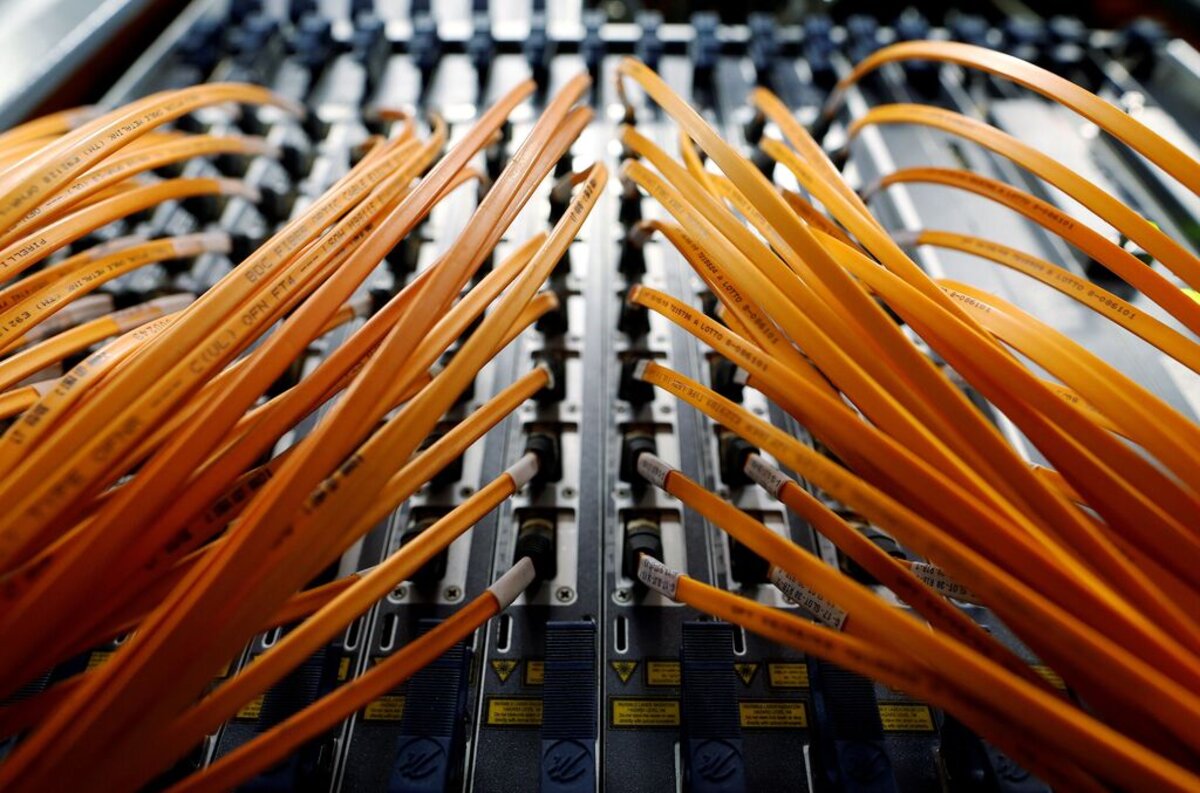

At least one close observer has called the hack of U.S. government computer systems first exposed last month as nothing short of a Pearl Harbor moment, a sneak attack of huge and lasting importance.

In December, Orion management software developed by the SolarWinds company was found to have been hacked, very likely by Russian agents. Orion is used by some 18,000 clients, mostly private corporations. But among the users penetrated were U.S. government agencies, including the Department of State, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Pentagon. Passwords, user IDs, source code, and financial records would have been exposed to view.

Solutions won’t be easy or inexpensive. Government agencies will have to cleanse their systems. Numerous questions will need answers, security experts say.

The software used by government often overlaps with that in use in the private sector. New security standards for software the government procures could increase security for products that all Americans use.

The incoming Biden administration will have to act quickly. President-elect Joe Biden faces a list of formidable challenges that need immediate attention, headed by the pandemic and its economic fallout. But cybersecurity now must be high on the list too.

Responding to a cyber Pearl Harbor

The drama of Washington politics, including the bumpy transfer of power between political parties, understandably has seized public attention now. And the ongoing pandemic fills nearly the rest of the news diet.

But if the United States weren’t experiencing such unusual times, the massive hacking of U.S. government computer systems might be dominating the news media. Granted, most people are pretty oblivious as to just what goes on behind the scenes as they type away on their laptops. Information flows, coming and going. They may know that internet privacy has been a concern for a while, but aren’t sure exactly what’s at stake or what can be done about it.

At least one close observer has called the hack of U.S. government computer systems first exposed last month as nothing short of a Pearl Harbor moment, a sneak attack of huge and lasting importance.

A quick review: In December, Orion management software developed by the SolarWinds company was found to have been hacked, very likely by Russian agents. Orion is used by some 18,000 clients, mostly private corporations. But among the users penetrated were U.S. government agencies, including the Department of State, the Department of Homeland Security, the Pentagon, the Department of the Treasury, and the National Nuclear Security Administration. Even Microsoft’s ubiquitous Windows and Office programs may be compromised.

The attack apparently was launched from within the U.S. enabling it to avoid sensors set up by the National Security Agency that look for threats originating abroad.

What does “hacked” mean? Passwords, user IDs, source code, and financial records would have been exposed to view. What’s not yet as clear is whether malware has been installed that could cause future vulnerabilities, such as corrupting databases or seizing control of power grids.

The world of software development has put a priority on rapid innovation, ease of use, and shiny new features. Security has lagged behind, the necessary killjoy. The biggest change coming out of the SolarWinds debacle is likely to be a new insistence that security take a top priority.

Solutions won’t be easy or inexpensive. Government agencies will have to cleanse their systems. Numerous questions will need answers, security experts say: What were the goals of the attacks? Why was such vulnerable software chosen in the first place? What new security standards need to be implemented? What assurances will vendors give that their systems are secure, and what penalties should be imposed for their failure?

The software used by government often overlaps with that in use in the private sector. New security standards for software the government procures could increase security for products that all Americans use.

The National Defense Authorization Act recently passed by Congress contains some provisions that address cybervulnerabilities. And this week the FBI, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and other agencies joined forces to try to get a handle on a problem so pervasive that no one agency can cope with it.

The incoming Biden administration will have to act quickly. President-elect Joe Biden faces a list of formidable challenges that need immediate attention, headed by the pandemic and its economic fallout. But cybersecurity now must be high on the list too.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Never separated from God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Kathryn Jones Dunton

Sometimes we may feel lost and alone. But recognizing that God is always with us – as are the love and joy God imparts to all of us as God’s children – helps us find the way forward.

Never separated from God

I felt lost. My friends and family were a thousand miles away as I began my college experience. I was very shy and didn’t understand how to create a new life for myself. At first, I felt hopeless.

But then I began to learn about my identity as God’s precious child. I discovered that God is always with me, no matter how the structure and focus of my life changes.

Fundamentally, it’s God – not human relationships, circumstances, or patterns – that defines our life. Our identity and stability aren’t dependent on where we are; they can’t be left back home. They’re found in God. Nothing can separate us from the love of God, who expresses that love to and through all of us as His children. Our relation to God is the constant in our lives.

In “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, refers to rising “above the oft-repeated inquiry, What am I? to the scientific response: I am able to impart truth, health, and happiness, and this is my rock of salvation and my reason for existing” (p. 165). This describes actions that are independent of specific locations or individuals. It’s about actively reflecting God’s nature, the qualities that God expresses in each of us, everywhere, always.

This reason for existing is constant even as the scenes of our lives change. We can trust that God’s plan for us is good, because God is infinitely good. Mrs. Eddy’s primary work on Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” says, “Each successive stage of experience unfolds new views of divine goodness and love” (p. 66).

When we are confronted by dizzying change, we can become very quiet inside and listen for God’s voice. God is always communicating to us the love and guidance we need. God is the Rock upon which we stand. Like a rock, God is steady, sure, dependable, and unmovable, unlike the shifting sands of human experience.

In college, I found that as I acted upon the inspiration of my prayers, wonderful new vistas opened up. Instead of passively waiting for things to happen, I learned to actively follow the direction of God, exemplified and articulated by Jesus, to love myself and others (see Matthew 22:36-40). This helped me break through my shell of shyness, make friends, and find happiness.

If we’re feeling lost, we can look to God to find the purpose of our life – to love God and to love others – and experience the blessings this brings to those around us and ourselves, too.

A message of love

An attack on democracy reaches into halls of Congress

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about how President-elect Joe Biden’s relationship-building in Congress may help him as president.