- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘The Repair Shop’: Where fixing family memories is Job 1

April Austin

April Austin

Gentleness, empathy, kindness. How unexpectedly delightful to find them in a television show. I’ve started watching “The Repair Shop,” a British reality show streaming in the U.S. on Netflix, and it is a balm in troubled times.

In each episode, talented master craftspeople mend broken heirlooms and return them to thrilled and grateful owners. The objects may or may not be worth a great deal of money, but to their owners the memories they evoke are priceless. Families often become weepy describing how a beloved grandfather enjoyed the chiming of a clock, or how they’d like to hand down a wicker crib to their adult daughter who’s expecting a baby.

The master artisans receive these family stories like gifts, and humbly place their skills in the service of reviving those lost memories. It’s a profound act for one person to render to another human being: I honor your memories and the trust you place in me.

Aside from the sheer enjoyment of watching craftspeople who are incredibly skilled at what they do, the emotional payoff for me is seeing the owners reunited with their heirlooms. It’s as if a piece of their lives has been restored to them.

Now, some might argue that material things don’t deserve to be invested with this much power. Still, for the families, the items symbolize continuity, affection, and family ties. And for the artisans, pride of workmanship becomes subservient to making something – and someone – whole.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

After a ‘post truth’ presidency, can America make facts real again?

American discourse has gone from “you’re entitled to your own opinion, but you're not entitled to your own facts” to an embrace of falsehoods that one observer dubs a “national reality disorder.” Scientists say the journey back is difficult but possible.

When rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol, the assault hinted at the risks of politics unmoored from facts. That can threaten the very fabric of society.

That an incoming U.S. president devoted part of his inaugural address to insist that facts are, in fact, factual reveals just how much of a beating the truth has taken. Over the past five years, politics have motivated huge swaths of the American public to abandon not just facts, but also the system of logic and standards of evidence used to establish facts in the first place. This phenomenon is widely known as “post truth.”

“Post truth is the political subordination of reality,” says Lee McIntyre, author of a book on the subject. “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced ideologue," he says, paraphrasing Hannah Arendt. "It’s the person for whom true and false and right and wrong don’t exist.”

Solutions range from the institutional to the interpersonal. Overcoming the post-truth era will require a renewed public emphasis not just on science, but also on thinking scientifically or critically.

“There is no silver bullet here,” says Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. “Really, it’s a portfolio you need, a whole variety of approaches, none of which is going to solve all this by itself.”

One sign of hope: More than 8 in 10 Americans are concerned about the spread of false information.

After a ‘post truth’ presidency, can America make facts real again?

A common theme in U.S. inaugural addresses is for the newly sworn-in president to identify what he sees as the country’s biggest problem. For Ronald Reagan, it was government overreach. For Barack Obama, it was “our collective failure to make hard choices.” For Franklin Roosevelt, it was fear itself.

For Joe Biden, it was a breakdown of national cohesion, common purpose, and reality’s most fundamental distinction.

“There is truth, and there are lies,” said President Biden. “And each of us has a duty and responsibility ... to defend the truth and to defeat the lies.”

That an incoming U.S. president devoted part of his inaugural address to insist that facts are, in fact, factual reveals just how much of a beating the truth has taken. Over the past five years, politics have motivated huge swaths of the American public to abandon not just facts, but also the system of logic and standards of evidence used to establish facts in the first place. This phenomenon is widely known as “post truth.”

It didn’t start with Donald Trump and hasn’t ended with his departure. But his presidency pushed the boundaries. Notable falsehoods ranged from the seemingly petty, such as his inflation of inauguration attendance and his apparent altering of a National Weather Service map with a Sharpie, to the momentous, such as his claims that China was paying for U.S.-imposed tariffs or that the coronavirus pandemic was “very much under control.” Most damaging were his baseless claims that the 2020 presidential election was stolen. On Jan. 6, those claims culminated in a mob of Trump supporters storming the U.S. Capitol, an attack that cost the lives of five people.

Now, a new president has arrived with a stated priority on truth-telling. But as important as that can be, many experts on public discourse say solutions need to extend beyond the corridors of Washington into our news outlets, schools, and neighborhoods. They’ll range from the institutional to the interpersonal. Overcoming the post-truth era will require a renewed public emphasis not just on science, but also on thinking scientifically or critically.

“There is no silver bullet here,” says Anthony Leiserowitz, who, in his role as director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, has spent the bulk of his career thinking deeply about the truth and its opposite. “Really, it’s a portfolio you need, a whole variety of approaches, none of which is going to solve all this by itself.”

If a healthy democracy requires grassroots engagement, many observers also see a need for institutional change at the top.

President Biden has sent strong signals that he intends to push for just that. The scientific community has largely welcomed his selection of advisers with strong research backgrounds, particularly his elevation of a science adviser to a Cabinet-level position. His decision to rejoin the Paris Agreement on climate change showed his acceptance of a scientific consensus that Mr. Trump flouted.

President Biden’s “wartime” strategy to combat the pandemic has also drawn praise as a fact-grounded response. Speaking on NBC in late January, former FDA Associate Commissioner Peter Pitts praised his efforts to collaborate with states on the logistics of delivering the vaccine. “Science is back,” he said. “That’s really good news.”

That said, it remains to be seen how broadly Mr. Biden and his now-ascendant fellow Democrats in Congress will actually hew to scientific understanding.

Mr. Biden’s coronavirus policy, for instance, departs considerably from the scientific consensus that the most effective way to combat the virus’s spread is with a national stay-at-home order, a move that some of his own science advisers had called for, prior to walking back their comments.

Climate policy under Mr. Biden may similarly reveal an attempt to balance scientific understanding with political expediency. He calls for full-scale efforts to address climate change, yet has kept the door open to the process known as fracking – the injection of water, sand, and other chemicals into bedrock formations to extract fossil fuels. Fracking has consistently been shown to be a driver of global warming, but has also greatly contributed to the rise of the United States as a global exporter of fossil fuels.

A tool of authoritarians

The Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol illustrated how the unmooring of politics from facts can threaten the very foundations of democracy. During the Second World War and the years that followed, writers like George Orwell and Hannah Arendt memorably described how pervasive, bald-faced political lying serves the interests of totalitarianism, for example.

“Post truth is the political subordination of reality,” says Lee McIntyre, a research fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University and the author of the 2018 book, “Post Truth.” “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced ideologue," he says, paraphrasing Arendt. "It’s the person for whom true and false and right and wrong don’t exist.”

But in recent years, misinformation – and its intentional sibling, disinformation – have come to play an outsize role in American politics, thanks in part to the rise of social media. A study published in October by the German Marshall Fund of the United States found that, from 2016 to 2020, Facebook interactions with news articles from sites that publish false or misleading content rose by 242%, with much of the increase happening in 2020.

“The structure of how we share information about the world has been radically decentralized,” says Dr. Leiserowitz. “We’ve entered a world in which anyone can be a journalist, a contributor to the discourse. But everyone is also expected to be an editor, to distinguish between what’s real and what’s not.”

Online misinformation is shifting Americans’ perceptions of reality. According to a December NPR/Ipsos poll, 17% of respondents aligned themselves with the QAnon conspiracy theory, saying they believe the statement that “a group of Satan-worshiping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media.” Fewer than half (47%) identified the statement as false.

None of this is to suggest that Americans don’t care about the truth. They clearly do: The same poll showed that more than 8 in 10 Americans are concerned about the spread of false information. As Nancy Rosenblum, a Harvard University professor emerita of Ethics in Politics and Government, points out, people don’t typically deny empirical reality when, say, calculating their grocery budgets. “We don’t do this outside of politics,” she says.

Near the end of Mr. Trump’s presidency, America’s institutional patience for misinformation and conspiracy theories seemed to begin wearing thin. Following the Capitol attack, Mr. Trump was banned by Twitter and Facebook. On Thursday, the U.S. House of Representatives voted largely along party lines to bar Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia from serving on committees, in light of her record of inflammatory and unfounded statements rooted in conspiracy theories.

“Somebody who’s suggested that perhaps no airplane hit the Pentagon on 9/11, that horrifying school shootings were pre-staged, and that the Clintons crashed JFK Jr.’s airplane is not living in reality,” said Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, in an uncharacteristically harsh rebuke of a fellow Republican.

Fighting lies with facts – and science

How can Americans more broadly elevate the place of facts in political discourse? The solution lies in education, says Mona Weissmark, an adjunct associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

“People are not, in high school or in college, trained to have any kind of scientific reasoning background,” says Dr. Weissmark. “They can’t make sense of the conflicting information.”

Dr. Weissmark says that scientific thinking – an approach that tests facts empirically, examines assumptions, considers alternative hypotheses, invites others to challenge conclusions, and whose findings always remain open to revision – can be taught.

“The good news is it’s easily fixable,” she says. “It’s totally possible. I’ve been seeing it for years.”

One simple, effective technique for combating falsehoods is called inoculation theory, says Dr. Leiserowitz. Research indicates that offering people gentle descriptions of misinformation and a counterargument in advance can help them ward off future lies.

For instance, you could say to someone, “You may hear that there is no scientific consensus on global warming. But, in fact, surveys have found that 97% of climate scientists agree that human-caused climate change is happening.”

“When you inform people of that ahead of time, you’re training them to become more critical consumers of information,” Dr. Leiserowitz says.

Such efforts to plant seeds of truth may not work with everyone, given human tendencies such as “motivated reasoning” (reaching the conclusions one desires) or “confirmation bias” (interpreting new information in a way that supports one’s prior viewpoints).

But faith in falsehoods is by no means irreversible. The political scientists Ethan Porter of George Washington University and Thomas J. Wood of Ohio State University have been testing the issue in survey research since 2016. “We found that when presented with factually accurate information, Americans – liberals, conservatives and everyone in between – generally respond by becoming more accurate,” they wrote in Politico last year.

From skeptic to realist

Public debate over climate change has been a forerunner of wider battles today. Investigative journalists have revealed that scientists at big fossil fuel companies knew about climate change decades ago but kept their findings secret. Instead of taking action, they bankrolled skeptics to spread doubt.

One of those skeptics was Jerry Taylor, who, from the late-1980s to the late-2000s was, in his words, a “superspreader of misinformation” about climate change.

Most of that time was spent as the head of the Cato Institute’s energy and environment program, where he would assail the claims of climate scientists on broadcast news segments, share convincing but scientifically skewed talking points with journalists, and generally do his best to persuade people that there was little cause for alarm over global warming.

Today, however, Mr. Taylor is president of the Niskanen Center, a Washington, D.C., think tank that advocates, among other things, a carbon tax.

What happened? As Mr. Taylor tells it, his journey from denialist to realist began in the mid-2000s, after he appeared on TV with a climate expert Joe Romm. Mr. Taylor says that, in the green room after the segment ended, Dr. Romm challenged him to go back and re-read the source material they were disputing.

He did, and he found that Dr. Romm was right. From there on, Mr. Taylor says that he took greater care with checking his sources and challenging the assertions of Cato’s scientific advisers. “I was absolutely incredulous and really angry over the fact that I was being used as a conduit for misinformation,” Mr. Taylor says.

Gradually, Mr. Taylor’s views came to align with those of mainstream scientists who said that humanity’s influence on the climate is significant, and, later on, with those of mainstream economists who said that the costs of inaction greatly outweigh the costs of action.

Mr. Taylor doubts, however, that his own conversion experience can be widely replicated. “I’m not really a microcosm of how to bring us into a truth-based world,” he says.

He offers two reasons for this. First, part of his job at Cato was to engage his opponents ideas, and doing so requires a degree of intellectual honesty. “If you’re a serious actor in the think tank community, it’s virtually impossible for you to sweepingly dismiss expertise,” he says. “It’s called a think tank, not a grunt tank.”

Second, Mr. Taylor found that he was becoming less ideologically libertarian and less resistant to the idea of collective action in some circumstances. “I began to lose faith in the broader libertarian catechism that I was swimming in,” he says.

Mr. Taylor’s willingness to examine the facts without ideological prejudice, alongside an openness to changing one’s mind, are key elements of the scientific method. But these elements are not being cultivated by today’s conservative elite, he says.

A “crisis of trust”

Even if U.S. schools were to begin emphasizing scientific reasoning above all else, change wouldn’t come overnight, says Dr. Weissmark at Northwestern.

One reason is that any post-truth reconciliation will need to address emotional pain as well as promote scientific reasoning, she says. Dr. Weissmark, who is notable for her groundbreaking research that brought children of Holocaust survivors face-to-face with children of Nazis, says that today’s ideological polarization is correlated with an increase in stress, anxiety, and interpersonal problems that are unlikely to go away by themselves.

“The divide is so deep, and it’s playing out in how people take in facts,” she says.

Some observers say that it’s this lack of trust – between individuals and between individuals and institutions – that will need to be overcome for America to return to a fact-based political culture.

“This crisis of truth is really also a crisis of trust (in the institutions and practices of democratic governance and the belief that more often than not these function in fair and reliable fashion),” writes Cynthia Hooper, an associate professor of history at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, in an email to the Monitor.

This crisis, she writes, is “making it difficult for people on either side of the political spectrum to embrace ideas of moderation or champion rhetoric about ‘coming together.’”

Lee McIntyre, the Boston University philosopher, agrees that rebuilding trust is “the only way forward. ... When we begin to talk to one another again, that’s when we grow some trust,” he says.

But how?

Harvard’s Dr. Rosenblum points to a concept as ancient as it is familiar: neighborliness.

“The sphere around home is absolutely vital, says Dr. Rosenblum, whose books include “Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America,” in 2016, and “A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy,” in 2019.

“Take COVID as an example,” she says. “When people would say ‘how are you feeling today,’ it becomes an intimate important question. It can be the last preserve of reciprocal and democratic relations.”

Dr. Rosenblum, who dislikes the phrase “post truth” and prefers “national reality disorder,” expects that it will linger in state and federal politics for perhaps another decade, but is ultimately optimistic that it will come to an end.

“The beating heart of democracy has always been civil society,” she says, citing how groups like 350.org have rallied public support for climate action over the past decade. Today, two-thirds of Americans say that the government is not doing enough to combat global warming, according to Pew Research Center. “The kind of opposition that changes the minds of the public has come from civil society.”

GameStop drama a win for the little guys? Yes and no.

Everyone invested their own meaning in the GameStop saga. But what on the surface appeared to be a David and Goliath story is a more complicated tale of Wall Street, morality, and who’s able to profit in 21st-century America.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

It’s an irresistible tale: Young investors linked by social media beat Wall Street pros at their own game. Hedge funds, betting on a retail chain called GameStop to plunge in price, instead see a barrage of small investors snap up shares and send the stock soaring, eventually forcing the funds to lose billions.

The reality is more mundane: Big hedge funds also helped propel the stock upward and the small investors’ moves, while noble-sounding, probably were illegal.

Now, regulators and Congress are preparing to investigate what happened: stock manipulation, the opaque moves of lightly regulated hedge funds, and perhaps how the power of social media can be corralled as a force for good and not an organizational tool for illegal activity.

While politicians will look to regulation, some of the young investors who beat the hedge funds think dollar activism might be the faster, more powerful harbinger of change. Says product designer Zack Ewing, “You as an individual have a lot more agency with your dollars than your vote.”

GameStop drama a win for the little guys? Yes and no.

Two weeks ago, famed short seller Andrew Left planned to appear live over the internet to explain why shares of GameStop, a retail chain selling video games and consoles, would drop dramatically.

The event never happened. Instead, hackers attacked his social media accounts, published personal information about him, used threatening and profane language, and reportedly even texted his children. A day later, GameStop stock jumped 50% and closed at $65.01 while Mr. Left signaled he would no longer be commenting on the company. That was Friday, Jan. 22, the first of five days that would shake the investment world.

The saga of GameStop is proving to be irresistible to investors and non-investors alike because on the surface at least it illustrates a rare phenomenon: individuals beating Wall Street pros. For months a band of small investors on an online Reddit forum called WallStreetBets had been buying up shares of GameStop while hedge funds kept selling them, sure that the price would nosedive. Instead, the share price climbed in six months from $4 to $347 a share. Last week, a high-profile hedge ended its short selling, declaring huge losses.

“Wall Street is rigged against the small guy and it’s been that way for 100 years,” says Andrew Stoltmann, an investment fraud lawyer based in Chicago. But “against a couple of hedge funds, David has finally beat Goliath and it’s absolutely hysterical. There’s a reason why so many people are cheering these guys on.”

The GameStop story is also focusing a bright light on the ethics of short selling hedge funds. They are so lightly regulated that their opaque methods of gambling on a company’s demise are perfectly legal while, in a Dickensian twist, the transparent efforts of hundreds of individuals to prop up a company probably are not.

And GameStop also illustrates, so quickly on the heels of the Capitol insurrection, the power of social media. It can not only quickly spread a compelling idea but easily organize hundreds or more around a plan of action that can stir political violence and push stock prices far beyond a reasonable level.

These are large issues that regulators and Congress are likely to delve into in the weeks ahead. But for Zack Ewing and many other of the 20- to 30-year-olds who piled into GameStop, it was also personal.

Day 2: Jan. 25 – GameStop closes at $76.79

Mr. Ewing, a product designer in Johnson City, Tennessee, had seen the GameStop chatter pop up on Reddit forums for months. The thrust of the posts on WallStreetBets was that Wall Street was undervaluing GameStop, seeing it as a tired old retailer in physical stores without a strong online strategy. By buying the stock, one could make money. But more recently, the tone of the Reddit posts had changed.

Mr. Ewing noticed that forum users began touting GameStop as a way to beat Wall Street, specifically hedge funds that had bet against the company.

GameStop holds a special place in the hearts of 20-somethings, he says, because that’s where many of them bought their video games as children. The idea of taking on Wall Street added special allure because the ravages of the financial crisis were still fresh in their minds.

“My parents had multiple properties, and in 2008 they had to downsize,” he recalls. It was tough for them. It was tough for my wife’s parents. People I knew who were near retirement age almost overnight saw a third of their retirement wiped out. Big banks and investment houses made reckless bets on sketchy mortgages. But no one was held accountable, he adds. “Not only was there not a slap on the wrist, you’re going to take my taxpayer money to bail these people out?”

Mr. Ewing, a conservative investor, wasn’t quite ready to jump in, but he was “excited that these funds were going to get a little taste of their own medicine.”

Hedge funds operate in the shadows of the investing world. They’re not allowed to advertise and can only work with wealthy people who typically have several million dollars to invest. In exchange for that low profile, they are only very lightly regulated. To justify their fees, they typically use complex strategies and sometimes exotic instruments to try to earn more than what they could from holding common stocks. They closely guard their investment strategies, usually not even informing their investors.

One of those strategies is short selling companies. Short selling involves borrowing stocks from a broker at a high price and purchasing the option to buy it at a lower price. In the simplest form, it would be borrowing a stock at $100, watching it plunge, and buying it at $50 to give back to the broker, pocketing $50 per share minus expenses.

The trading on Jan. 25 was particularly volatile. Out of the gate, the stock jumped to nearly $120, almost double its Friday close, then shed most of that gain only to climb slowly back. If Reddit investors were suddenly going to try to stick it to hedge funds, then they would have to keep the faith and hold onto their stock no matter how dizzying the price swings. Entrepreneur Elon Musk, whose Tesla electric-car company was the target of short sellers for years, tweeted his encouragement, playing off GameStop’s name with an internet term for stock: “Gamestonk.”

Day 3: Jan. 26 – GameStop $147.98

After months of labor, Reddit investors had their day of triumph. Melvin Capital, one of the hedge funds known to be shorting GameStop and other stocks, including movie theater chain AMC, threw in the towel, losing a whopping 53% on its investments in January alone. Two other hedge funds advanced the firm nearly $3 billion to keep it afloat.

At the same time, the David-and-Goliath narrative begins to crumble. While Reddit individuals were buying GameStop, so were other big Wall Street firms. Senvest Management, another hedge fund, cashed in its holdings of GameStop and earned nearly $700 million. Blackrock, a huge asset management firm, revealed in a regulatory filing that it owned 13% of GameStop at the end of 2020, setting it up potentially for a $2.4 billion profit.

“The David and Goliath story is a false narrative,” says Sinan Aral, director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Initiative on the Digital Economy and author of “The Hype Machine: How Social Media Disrupts Our Elections, Our Economy, and Our Health – and How We Must Adapt.” The Reddit investors had plenty of help from big players, who moved the needle on the stock. How much help and whether there was any direction remains unknown.

Day 4: Jan. 27 – GameStop $347.51

Now that Reddit investors knew they had the short sellers on the ropes, they hoped to stick together for one last push to finalize the short squeeze.

Mr. Ewing jumped in, buying some shares for $1,000 “with the full expectation that they could absolutely go to zero,” he recalls. He loved the idea of some comeuppance for hedge funds.

Prices soared again, more than doubling and trading above $360. Then officialdom begins to act. The Nasdaq stock exchange briefly halts trading in GameStop, AMC, and one other stock – a normal occurrence when a stock’s price begins to swing wildly. TD Ameritrade limited some trades on both stocks, including others. After the trading day, the Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulates stock trading, said it was monitoring the situation.

Day 5: Jan. 28 – GameStop $193.60

Before the market opened, Robinhood – an online trading platform favored by many of the Reddit investors – announced it would no longer allow its customers to buy GameStop. They could only sell. The reaction was furious and immediate. While the company said it couldn’t continue to allow buying because of the huge amount of margin money the exchange was demanding for trading in such volatile stocks, the move seemed for many a blatant attempt by Wall Street powers to protect their own.

With few retail buyers – while the hedge funds were still allowed to sell – the share price plunged 44%. And Congress noticed.

“This is unacceptable,” Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York tweeted about Robinhood’s decision. Republican Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas chimed in with his support. The fact that politicians at opposite ends of the spectrum could agree on the right of individuals to invest suggests that Congress will begin to look into the GameStop saga to see who was behind the run-up in share prices, whether short sellers were aboveboard in their push to get the price down, and whether hedge funds in general need more scrutiny.

Congress has rarely even considered regulating hedge funds, says Charles Geisst, a historian and author of “Wall Street: A History.” But with the spotlight now on them, this might be a propitious time to begin to tackle the issue. “No one will ever feel sorry for short sellers,” he adds.

By casting a critical eye on companies, hedge funds play an important and useful role, some economists argue. They counter the hype that Wall Street sometimes generates around particular stocks. That skepticism helps the market offer more realistic pricing and adds liquidity to the market.

Still, it’s clearly not popular now. Six days after canceling his live event, Mr. Left announced he was walking away from 20 years of uncovering fraud in companies and short selling and would concentrate instead on good buying opportunities for investors. “When we started, Citron was supposed to be against the establishment,” he said in a YouTube video. “We’ve actually become the establishment.”

The irony is that short selling is legal, while, under current law, the Reddit investors who tried to pump up GameStop stock through coordinated trades probably broke laws against stock manipulation, says Mr. Stoltmann, an investment fraud lawyer based in Chicago. But there’s no way that they’ll be prosecuted, he adds. “The SEC would have a mutiny of near biblical proportions if they did this – a mutiny by the public, a mutiny by Congress, a mutiny by the press.”

“The $64,000 question is whether this is a one-time aberration or whether it’s a trend,” he adds. “If these little guys band together and they consistently engage in this behavior, then that’s a market destructor.”

In a note this week, RBC Capital Markets said they expected more such activity as retail investors plow money into other beaten-down stocks.

“We need a thorough investigation,” says Mr. Aral of MIT, given the recent high-profile instances of social media being used to organize illegal actions. “Do I think Congress has the stomach to regulate social media? I certainly think they have more than ever before.”

Mr. Ewing sees small investors as more powerful agents of change. “There’s this historical reference to Wall Street as ‘smart money.’ But it’s not smart money and dumb money anymore. It’s fast money vs. slow money,” he says. “I think that individual money is fast money and fast money is much quicker to embrace climate consciousness, personal LGBTQ+ [rights], racial equality. Those problems are much easier to solve with your dollar than [by] voting for a representative. ... You as an individual have a lot more agency with your dollars than your vote.”

On Thursday, Feb. 4, GameStop closed at $60.06 a share, down 83% from its peak close eight days ago.

How Orthodox defiance of pandemic lockdowns cleaves Israel

If a society is divided in the face of a common enemy, what does that say about its future cohesion? For Israelis, the unequal enforcement of pandemic lockdowns is creating a “watershed moment.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Even as Israel’s unparalleled vaccination program races ahead, the country’s third pandemic lockdown in a year has failed to curb deaths or the virus’s spread. Part of the failure stems from the poor enforcement of lockdowns in neighborhoods and cities that are home to the country’s ultra-Orthodox minority, or Haredim.

The growing community has long represented a looming challenge for the country because of its socioeconomic separatism. The rift dates back to Israel’s founding. In return for support in parliament, secular politicians have allowed the ultra-Orthodox to craft their own school curricula and have given young men exemptions from military conscription.

Their autonomy was on display Sunday, when tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox mourners, blatantly defying government orders and their community’s own losses from the pandemic, turned out at a tightly packed Jerusalem funeral for a prominent rabbi who had died from the coronavirus.

The pandemic’s heavy toll has spurred a sense that Haredi autonomy is something that politicians and Israeli society need to confront immediately. “We’re talking about life and death now,” says author Yossi Klein Halevi of the lockdown defiance. “This is a watershed moment for Israeli society.”

How Orthodox defiance of pandemic lockdowns cleaves Israel

The lockdown scenes midday Sunday in the two cities provided a COVID-19 split screen – a tale of two Israels.

In Jerusalem, tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox mourners turned out at a tightly packed funeral for a prominent rabbi who had died from the coronavirus. Their gathering was in blatant defiance of government restrictions that police said they were helpless to enforce.

In Tel Aviv, police patrolled public squares to scare away potential crowds and ensured the stalls in open-air markets remained shuttered by the lockdown.

The disparity was lost on no one, and points to a festering societal division that is far deeper and older than adherence to pandemic protocols.

The restrictions are “killing us. I can’t have one person come in here, or I’ll get a fine. It’s sad to see the market closed,” says Abed Ovadia, a normally boisterous fruit seller in Tel Aviv’s Carmel Market, standing in an empty stall usually brimming with apples and pears.

When the conversation turns to the large-scale disobedience among the ultra-Orthodox, Mr. Ovadia vents.

“They defy everything. They exploit the fact that they have power in the Knesset. If they didn’t have that power, they wouldn’t behave like that. That’s why people are suffering.”

Failure to curb virus

Mr. Ovadia’s frustration resonates far and wide. Even as Israel’s unparalleled vaccination program races ahead, the country’s third pandemic lockdown in a year has failed to curb deaths or the virus’s spread.

Part of the failure stems from the government’s poor enforcement of lockdowns in neighborhoods and cities that are home to the country’s ultra-Orthodox minority, known as Haredim – Hebrew for “God-fearing.”

The community, 12% of Israel’s population, has long represented a looming social and political challenge for the country because of its high birthrates and socioeconomic separatism. But the pandemic has spurred a sense that Haredi autonomy is something that politicians and Israeli society need to confront immediately.

In addition to footage of mass weddings and funerals, television news has been filled with images of riots, fires, rock throwing, and border police violently chasing down rebellious youths – scenes deeply troubling for Israelis because of their resemblance to clashes with Palestinians in the occupied West Bank.

“We’re talking about life and death now,” says Yossi Klein Halevi, an author and fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, of the lockdown confrontations. “This is a watershed moment for Israeli society.”

The secular-Haredi rift – and accommodations – date back to Israel’s founding. In return for support in parliament, secular politicians have allowed the ultra-Orthodox to craft their own school curricula and have given young men exemptions from military conscription.

But the pandemic’s heavy toll has thrown into relief that the Haredim operate as an autonomous entity and can leverage their political power to resist Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

What is seen as his government’s lax approach to Haredi defiance has secular Israelis boiling over.

“Enough! Who runs this country?” tweeted parliament opposition leader Yair Lapid, saying ultra-Orthodox elementary schools stayed open while students in the rest of the country remained at home. “Whoever doesn’t comply should have funding stopped. In a sane country, there is one law for everyone.”

Analysts say much of the problem is a question of political will. Mr. Netanyahu, running for reelection in March and in the midst of a corruption trial, is being criticized as overly deferential to ultra-Orthodox politicians and rabbis, whom he needs in his coalition.

“They have their own prime minister – their rabbi. They only listen to what their rabbi says,” says Arik Golan, the owner of a pet supply store in Tel Aviv. “And their rabbi doesn’t listen to our prime minister.”

Haredi soul-searching

Yet the crisis of leadership extends to within the Haredi community, as well.

The ultra-Orthodox minority – which mostly lives apart, in impoverished, densely populated neighborhoods – has suffered the worst fallout from the pandemic. Among Israelis older than 60, nearly four times as many Haredim have died per capita than the general Jewish population, according to Israel Health Ministry data.

Even amid the clashes challenging the government’s authority, there’s also been, for the first time, some public soul-searching within the Haredi community as well as criticism of the leadership.

“Guilty are we,” read a banner headline in the Haredi newspaper Mishpacha.

Last week, following rock-throwing clashes with police in Bnei Brak, a Haredi city outside Tel Aviv, one ultra-Orthodox commentator attacked leaders for making excuses and equivocating.

“I am pulling my hair out in anger and shame at people who are burying the Haredi public and explaining why they are right,” said Moshe Glesner, an ultra-Orthodox television host on a public affairs program. “We are paying with our lives.”

To be sure, the ultra-Orthodox defiance is not confined to Israel. Communities in New York and the United Kingdom have also held mass gatherings in defiance of local restrictions. Denying the severity of the pandemic and scorning science, they insist on keeping synagogues, schools, and religious seminaries open.

Political consequences

In Israel, however, where the Haredim reject the secular Jewish state on theological grounds, the politicization of the pandemic has more grave consequences.

“Israelis are beginning to realize that Haredi separatism – the Haredi state within a state – is not just offensive, but literally a life-and-death danger,” says Mr. Klein Halevi. “Israel will not be able to remain a cutting-edge society with 12% of its society living in the 19th century. We certainly can’t continue subsidizing this separatism.”

Israel battled the pandemic in January with mixed results. It led all countries by a wide margin in vaccinations per capita. But the presence of more potent variants of the virus and the lockdown failures have kept new infection rates among the highest in the world, pressuring hospitals and resulting in a per capita death rate twice the worldwide average.

Responding to the mass funeral Sunday, Dror Mevorach, the COVID-19 ward director at Jerusalem’s Hadassah Hospital-Ein Kerem, told Israel Army Radio: “When you see this, and you know for sure that dozens, if not hundreds, will become infected, and they will infect hundreds of others, and that will lead to people dying – it’s difficult to watch.”

Israel’s failure to enforce COVID-19 restrictions on the ultra-Orthodox “exposes a bitter truth about Israel’s resilience,” wrote Ben Caspit, a columnist in the Maariv newspaper. “There is no state here. There is a loose confederation of tribes, devoid of central authority, common values, or a common goal. Israel’s façade is disintegrating into fragments live on television.”

Self-interest vs. the state

The bitterness over the lack of unity may have a cost. A Jan. 26 survey by Channel 12 news found that 61% of Israelis want the next coalition to exclude ultra-Orthodox parties, reflecting how the pandemic has made the independence enjoyed by Israel’s Haredim a top issue, with broad implications.

In normal times, few Israelis focus on what’s necessary to end the ultra-Orthodox separation and integrate the community, says Gilad Malach, an expert on the Haredi community at the Israel Democracy Institute: teaching a general studies curriculum, ensuring young men get jobs rather than remain in yeshivot, and ending the exemption for military conscription.

But after a year of the pandemic, Israelis recognize the immediate consequences of allowing the ultra-Orthodox to persist as a state within a state.

“Ultra-Orthodox society is very clear that it sees itself as having full autonomy whether to comply or not with the orders of the state,” Mr. Malach says. “If you don’t comply regarding issues of life and death, will you comply with the orders of education?

“When there’s a contradiction between their self-interest and the needs of the state, they prefer their self-interest – their community wins. This is the challenge of the state.”

Commentary

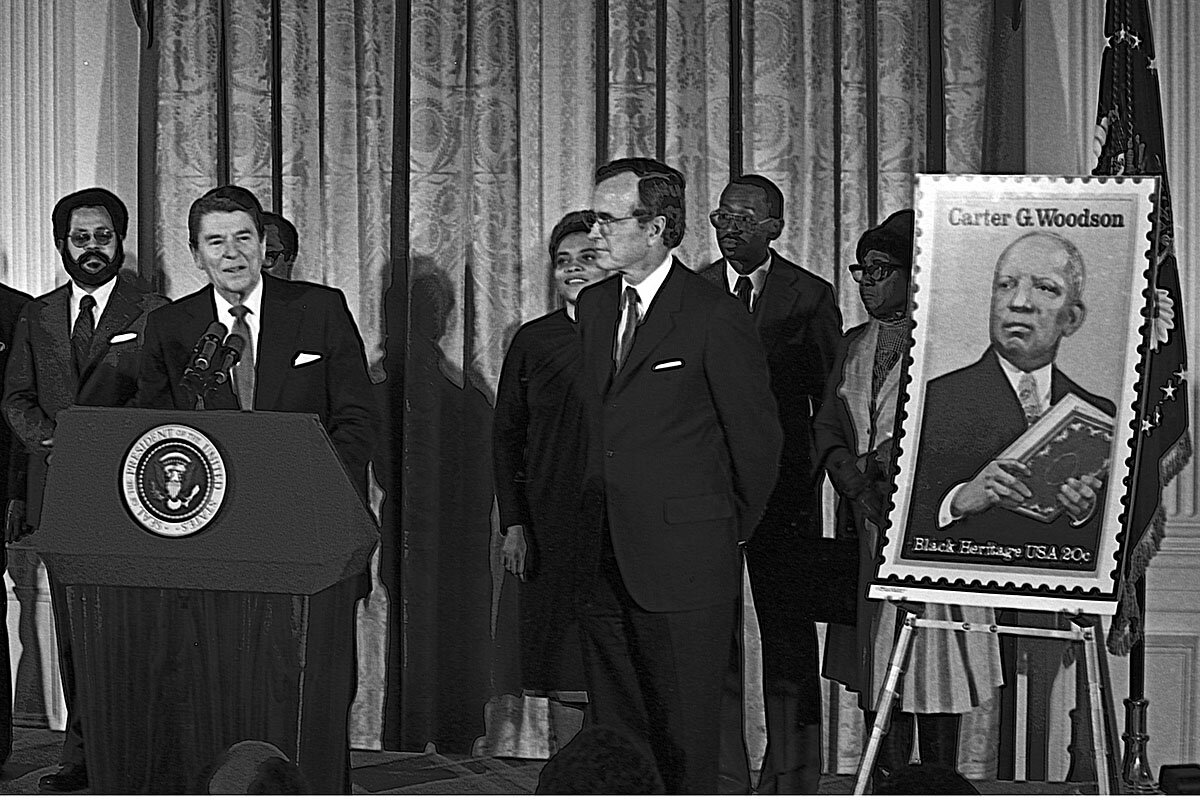

Can Black History Month live up to its founder’s vision?

Confining the study of Black history to February, our commentator argues, leads Americans to misunderstand their past – and present. When it comes to history, the whole is far greater than the sum of its parts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Though he founded Negro History Week, Dr. Carter G. Woodson never intended for what we now recognize as Black History Month to be a decadeslong endeavor.

“It is not so much a Negro History Week as it is a History Week,” he wrote. “The case of the Negro is well taken care of when it is shown how he has influenced the development of civilization.”

Yet nearly a century later, the decision to treat Black history like a piece of apparel to be worn and then discarded on March 1 leaves us at a crossroads.

The willful omission of the achievements and adversity of Black folk has stunted Americans’ growth. It has affected how we understand capital and storming the Capitol. Our country is still reeling from an attack on a government building by individuals who, ironically, felt they were victims of voter suppression and election fraud – yet they brandished symbols recalling the poll taxes and intimidation that for decades prevented African Americans from voting.

As young Americans, we learn reading, ’riting, and ’rithmetic. My urgent suggestion is that we embrace the four R’s of rich Black history – revolution, Reconstruction, rights, and right now.

That will bring us closer to Woodson’s vision.

Can Black History Month live up to its founder’s vision?

A few years ago, I was awestruck when NBA guard Jarrett Jack wore a T-shirt to commemorate the study of Black history during the month of February. The shirt read, “Black History [Month] Years” – with “Month” crossed out. The wording resonated with me.

It still does.

The history of Black people in America and abroad can’t be adequately taught – if taught at all – in 28 or 29 days. Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the “father of Black history,” knew that full well. That’s why he never intended for what we now recognize as Black History Month to be a decadeslong endeavor.

A year after founding Negro History Week in 1926, Woodson offered this explanation in The Journal of Negro History, which he also founded:

This is the meaning of Negro History Week. It is not so much a Negro History Week as it is a History Week. We should emphasize not Negro History, but the Negro in history. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hate, and religious prejudice. There should be no indulgence in undue eulogy of the Negro. The case of the Negro is well taken care of when it is shown how he has influenced the development of civilization.

The idea of carving out a path for Black history – even being the “father” of Black history – doesn’t do Woodson justice. He not only cut a path, a gateway, into Black achievement; he also had to cut through the horrors committed against Black people in the United States. Those horrors separated Black people not only from their native land but also from hard-won freedoms during Reconstruction.

A short-lived renaissance

The result of Woodson’s quest, at least in the short term, was a renaissance: “The demand for the literature [related to Negro History Week] was not restricted to those sections of the country in which Negro schools are established,” he wrote. Rather, the demand was “unprecedented,” a national newspaper noted.

Yet nearly a century later, the decision to treat Black history like a piece of apparel to be worn and then discarded on March 1 leaves us at a crossroads.

The willful omission of the achievements and adversity of Black folk has stunted Americans’ growth. It has affected how we understand capital and storming the Capitol. We see wealth disparities as individual successes or failures rather than as products of systemic racism. Our country is reeling from an attack on the Capitol by individuals who felt they were victims of voter suppression and election fraud – yet they brandished symbols recalling the poll taxes and intimidation that for decades prevented African Americans from voting.

The four R’s of Black history

American history as we know it is ahistorical. That needs to change – starting in our schools. Woodson touches on this urgent need in his provocative and profound “The Mis-Education of the Negro.” In the opening chapter, aptly titled “The Seat of the Trouble,” he wrote:

As another has well said, to handicap a student by teaching him that his black face is a curse and that his struggle to change his condition is hopeless is the worst sort of lynching. It kills one’s aspirations and dooms him to vagabondage and crime. It is strange, then, that the friends of truth and the promoters of freedom have not risen up against the present propaganda in the schools and crushed it. This crusade is much more important than the anti-lynching movement, because there would be no lynching if it did not start in the classroom. Why not exploit, enslave or exterminate a class that everybody is taught to regard as inferior?

As young Americans, we learn reading, ’riting, and ’rithmetic. My urgent suggestion to us now is that we embrace the four R’s of rich Black history – revolution, Reconstruction, rights, and right now.

That will bring us closer to Woodson’s vision.

Ken Makin is the host of the “Makin’ A Difference” podcast.

Essay

What tulips taught me about growing in the dark

Pandemic strictures may seem to limit opportunities, to stunt growth and careers. But this essayist looks to history and horticulture as proof that cold, dark times can be crucibles for greatness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Gail Russell Chaddock Correspondent

I should have grown vegetables, given my salary and prospects. Instead, I planted tulips.

I did so that fall – tulips need dark and cold. Without them, the blooms are malformed and weak.

Those tulips were glorious – probably. I don’t recall. What I do remember is looking out at that bleak frozen bed and imagining those bulbs growing. And, as I came to see it, so was I.

The cold, dark times when best plans crumble or prospects fade are a recurring theme in life stories.

Odette Lamolle’s hopes to become a translator were upended by the 1940 Nazi invasion of France. After the war, she took up the family business. But she never lost her love of English literature, especially the work of Joseph Conrad.

After she’d retired in 1980, her daughter complained about having to read “Lord Jim.” Lamolle read the translation, declared it wholly inadequate, began her own, and kept going. In 1997, a French publisher accepted all of her 24 translations of Conrad novels and novellas.

What tulips taught me about growing in the dark

After years of living in one-room rental somethings, the prospect of moving into the back of a house with a bit of land for a garden was thrilling. I could have grown food. With my salary (minimal) and prospects (remote), vegetables seemed a prudent move.

Instead, I planted tulips.

Blame it on reading too much period English fiction. The prospect of living in beauty trumped winter squash. I would find one of those baskets that Jane Austen heroines fill with flowers as they wait for the visit or letter that will change their lives. I would arrange the tulips in tall glass vases and fill the house with color.

I collected advice on planting tulips. Start in the fall, but before the ground freezes. Dig deep, loosen the soil, plant bulbs pointy end up. Water lightly, then wait. Tulips need dark and cold, they said. Without them, the blooms are malformed and weak.

Those tulips I planted decades ago were glorious – probably. I don’t recall. What I do remember is looking out at that bleak frozen bed, through all that a New England winter could throw at it, and imagining those bulbs growing in the dark. And, as I came to see it, so was I.

The cold, dark times when best plans crumble or prospects fade are a recurring theme in life stories across many fields. In some biographies, so-called wilderness periods are mere setbacks on a path to greatness. In others, they are a crucible for patience and new possibilities.

Here’s how one 17th-century student responded to a pandemic that derailed his education: Isaac Newton escaped a life tending pigs after an uncle and the local schoolmaster found him a place at Trinity College, the apex of English higher education. But just then the Great Plague of 1665 closed the college. Newton returned home to an obscure hamlet and uncertain prospects – and a resolve to direct his own education. He built bookshelves and set himself questions to answer and problems to solve. From the stepfather who had once denied him a home, he inherited a leather notebook with nearly 1,000 blank sheets of paper – a precious resource at the time. Over the next 20 months, he filled it with notes, computations, and questions that redefined mathematics, optics, mechanics, and eventually modern science.

“The plague year was his transfiguration,” writes biographer James Gleick. “Solitary and almost incommunicado, he became the world’s paramount mathematician.” As Newton explained his own process: “I keep the subject constantly before me and wait ‘till the first dawnings open slowly, by little and little, into a full and clear light.”

Wilderness experiences are a staple of political biography. Winston Churchill was ignored when he warned about Adolf Hitler’s rise. Ulysses S. Grant was derided as a loser and a drunk, until he started grinding out victories on Civil War battlefields. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s struggle with polio has been recast by recent biographers as a source of strength.

Some wilderness sojourns last nearly a lifetime. Odette Lamolle’s hopes to study to become a translator were upended when the Nazis invaded France in 1940. After the war, she took up the family’s hairdresser supply business. She didn’t become a translator until she retired in 1980. Like Newton, she never traveled far from her remote farmhouse. She never visited Paris or made contacts in the publishing world. But she never lost her love of English literature, especially the work of Joseph Conrad.

She spoke English haltingly but translated English into French with an authority and ease that astonished the publishing world once her work surfaced.

When I met her in 1997, a French publisher had just accepted her translations of all 24 Conrad novels and novellas. She’d begun when her daughter complained about having to read “Lord Jim.” Lamolle read the translation and declared it wholly inadequate.

She started out translating one novel for her daughter and wound up translating them all – an epic undertaking for any publishing career at any age.

“I never dreamed it would be published,” she said.

That’s truly growing in the dark.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Beethoven rolls over Russian police

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Russian police were quite surprised last week when they showed up at the Moscow apartment of Anastasia Vasilyeva to arrest her. Instead of offering angry resistance, the political dissident played them a recital of Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Für Elise” on her piano. A video of the performance has gone viral, perhaps giving a new flavor to the protests against the Putin regime to release the country’s most famous dissident, Alexei Navalny.

Artists and performers have long been able to shift political culture, offering aesthetic experiences that increase understanding or create a shared identity. Yet the digital age has expanded their reach and impact as well as endangered them. News of artists-as-dissidents is now almost the norm in world trouble spots.

Political protests do not always succeed because of their numbers but because of the messages they send, often in subtle ways. By itself, playing Beethoven for police and posting it on YouTube may not turn Russia into a democracy. But something has to keep lifting the thought of protesters in creative ways and perhaps change the thinking of their oppressors. It might as well be the music of someone who envisioned an alternative society two centuries ago.

Beethoven rolls over Russian police

Russian police were quite surprised last week when they showed up at the Moscow apartment of Anastasia Vasilyeva to arrest her. Instead of offering angry resistance, the political dissident played them a recital of Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Für Elise” on her piano. A video of the performance has gone viral, perhaps giving a new flavor to the protests against the Putin regime to release the country’s most famous dissident, Alexei Navalny.

Ms. Vasilyeva is better known as a doctor than an artist, but her lively rendition of the classical tune sent a subtle message. The Beethoven composition is calming – one reason it is also a popular cellphone ring tone. Its gentleness creates a receptivity in the listener. Its universal tone makes it hard not to feel a bond with others. In fact, a German group, the Beethoven Academy, gives awards each year to artists who live up to the composer’s reputation as “the visionary of an alternative society.”

Artists and performers have long been able to shift political culture, offering aesthetic experiences that increase understanding or create a shared identity. Yet the digital age has expanded their reach and impact as well as endangered them. The Institute of International Education, for example, offers an artist protection fund to support threatened artists. Since 2012, the Human Rights Foundation has offered a prize for “creative dissent,” named after the Czech playwright Václav Havel who helped fell the Soviet empire.

News of artists-as-dissidents is now almost the norm in world trouble spots. In Uganda, rapper Bobi Wine used his political lyrics to gain enough followers so he could run against dictator Yoweri Museveni in a recent election. An exiled Chinese dissident, Badiucao, uses satirical images to raise awareness of the persecution of the Uyghur minority. A group of artists in Cuba have lately stepped up their challenge to the government’s suppression of their work and dissent in general.

Because good art, whether a play or a painting, creates its own meaning and dignity, it allows viewers to experience meaning and dignity. For those living under authoritarian rule and unable to protest in public, art can carry the flag of freedom. A 2015 report by the United States Institute of Peace in Washington said arts and cultural practices aimed at peace building can “embody a kind of power that rests not on injury or domination, but rather on reciprocity, connectivity, and generativity.”

Political protests do not always succeed because of their numbers but because of the messages they send, often in subtle ways. By itself, playing Beethoven for police and posting it on YouTube may not turn Russia into a free and fair democracy. But something has to keep lifting the thought of protesters in creative ways and perhaps change the thinking of their oppressors. It might as well be the music of someone who envisioned an alternative society two centuries ago.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

To help undercut tyranny

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By David C. Kennedy

This week’s events in Myanmar, among others, may make cycles of oppression in the world seem inevitable. But through prayer inspired by the light of Christ, each of us can play a role in elevating human consciousness, contributing to an atmosphere that’s more consistently supportive of good.

To help undercut tyranny

After several years of working to transition into a democracy, this week the country of Myanmar was suddenly jolted back to authoritarian rule by a military coup. It’s a sad and ominous development for many in that country who had hoped that military rule was a thing of the past. And Myanmar isn’t the only country where authoritarianism is reasserting itself.

There are social and political explanations as to why tyranny keeps reappearing. But those are actually describing the surface effects of something taking place on a deeper level. “Where there is no vision, the people perish,” the Bible says (Proverbs 29:18). A clear understanding of the supremacy of God, who is infinite good, actually opens the door to freedom from suffering.

It’s not yet generally recognized that prevailing conceptions of God manifest themselves in humanity’s collective experience. In explaining the effects on society of materially based beliefs about God, the founder of the Monitor, Mary Baker Eddy, writes in the textbook of Christian Science, “Tyranny, intolerance, and bloodshed, wherever found, arise from the belief that the infinite is formed after the pattern of mortal personality, passion, and impulse” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 94).

If God is believed to be a magnified version of mortals – capable of both good and evil, love and hate – then evil seems to have a God-established place in creation for which there is no remedy, because creation emanates from the creator. Thankfully, there is a higher concept of God to turn to, one which Christ Jesus taught and proved in his healing ministry. He said, “God is a Spirit: and they that worship him must worship him in spirit and in truth” (John 4:24).

A growing understanding that God is infinite Spirit, forever harmonious and good, begins to replace the mistaken concepts of God that fuel tyranny. If God is infinite good, then the men and women of God’s creating innately partake of God’s goodness, expressing it in qualities such as wisdom, justice, unselfishness, and unity. And all are governed by God, the divine Principle of being, which governs justly and rightly.

Individuals today can and do pray to affirm this higher understanding of God, and prove through the healing of their own difficulties that what God has created is spiritual, harmonious, and good. This in turn brings the natural desire to look outward and benefit humanity more broadly, a development that the writer of First Timothy in the Bible strongly encourages: “I exhort therefore, that, first of all, supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks, be made for all men; for kings, and for all that are in authority; that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and honesty” (2:1, 2).

The spiritual light that fills one’s thought in prayer is the light of the Christ – the saving, healing Truth that Christ Jesus represented and embodied centuries ago. Because the Christ is eternal, it’s forever here to spiritually transform our sense of God, and to do the same for all those whom our prayers embrace.

The influence of the Christ in human consciousness brings the kind of change that Mrs. Eddy describes in another of her works, “The People’s Idea of God”: “Proportionately as the people’s belief of God, in every age, has been dematerialized and unfinited has their Deity become good; no longer a personal tyrant or a molten image, but the divine Life, Truth, and Love, – Life without beginning or ending, Truth without a lapse or error, and Love universal, infinite, eternal. This more perfect idea, held constantly before the people’s mind, must have a benign and elevating influence upon the character of nations as well as individuals, and will lift man ultimately to the understanding that our ideals form our characters, that as a man ‘thinketh in his heart, so is he’” (pp. 2-3).

We don’t know the times or the ways in which the light of Truth will find quiet access to human hearts and the societies and nations they inhabit. But our persistent, prayerful acknowledgment of God as supreme, infinite good will help cleanse human consciousness of its destructive elements, making it more supportive and productive of good in society and in government, and making it harder for tyranny to gain a foothold.

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article on overcoming superstition, please click through to a recent article on www.JSH-Online.com titled “Governed by God, not the planets.” There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

Back to school

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow: We’ll be looking at how small, nimble organizations are improving pandemic response.