- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Biden’s COVID-19 balancing act: Go big, but don’t overpromise

- A border runs through it: A tale of migration, separation, and reunification

- Can diplomacy deter Iranian nuclear ambitions a second time?

- Why California bill seeks to hire older police officers

- How The Weather Station draws inspiration from the outdoors

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Jeff Bezos: What are his after-Amazon ambitions?

You may have heard that one of the world’s wealthiest people is retiring. Well, sort of. Jeff Bezos is stepping down as CEO of Amazon.

But here’s what’s on his post-Amazon to-do list:

Any one of these challenges might be considered epic.

Yes, it could simply be that leading the world’s biggest online retailer isn’t as enjoyable for Mr. Bezos anymore. He and his company are a lightning rod for growing antitrust allegations and worker discontent.

But this isn’t retirement. If you take him at his word, it’s a next chapter. And it looks similar to the path taken by another tech multibillionaire, Bill Gates. He stepped down as CEO of Microsoft 20 years ago and gradually shifted his focus to philanthropic endeavors, spending more than $45 billion of his own money on global health, education, and climate initiatives.

In 2019, discussing his space ambitions and earthly projects, Mr. Bezos said he wants “a whole diversified portfolio of trying to do the right thing.”

One of the most successful entrepreneurs of our age is focusing his creativity and drive on some noble goals. The scale of the efforts suggest that we all might benefit if Mr. Bezos succeeds.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Biden’s COVID-19 balancing act: Go big, but don’t overpromise

Leadership in the U.S. today means managing public expectations while bringing an end to the greatest health crisis in a century. We look at how that’s going.

In the near term, after the chaotic Trump years, President Joe Biden’s bar for perceived success when it comes to the COVID-19 pandemic may be low. But in the long run, Mr. Biden – in promising to solve the biggest global health crisis in more than a century – faces a high bar. And his entire presidency will likely hinge on how he does.

In his first two days in office, the president signed 10 executive orders addressing the pandemic, including measures to accelerate vaccinations, improve testing, and safely reopen schools. Mr. Biden has brought in a team of seasoned government hands, including chief of staff Ron Klain and COVID-19 response coordinator Jeff Zients. He’s also ramped up public communication, with press secretary Jen Psaki briefing every weekday and the response team holding at least three televised briefings a week.

A major challenge is to square the public messaging with what people are seeing in their communities.

“Biden is talking about 100 million vaccinations in 100 days. Excellent,” says Marsha Vanderford, a consultant on global health communications. “But how does that unroll in conjunction with messages people are hearing that the vaccine clinics have been canceled in their county health department, because there’s no vaccine?”

Biden’s COVID-19 balancing act: Go big, but don’t overpromise

Two weeks into his term, President Joe Biden faces sky-high expectations in the battle against COVID-19.

He has brought in respected public health and logistics experts, stepped up the nationwide vaccination program, and put his $1.9 trillion relief package on a fast track to passage in Congress – aimed, too, at addressing the economic and educational hardships that have flowed from the pandemic.

In a blizzard of executive actions, President Biden has also moved urgently on immigration, climate change, and racial justice. But if Mr. Biden fails to get the pandemic under control, allowing for some semblance of a return to normal life in the United States, nothing else matters, analysts say.

“His presidency, at least for the first year, depends almost entirely on how he does on COVID,” says Paul Light, a professor of public service at New York University.

Part of Mr. Biden’s task is to manage public expectations. His initial goal of 100 million inoculations in 100 days might have a nice ring to it, but some public health experts called it too slow – and to “vaccine trackers,” that pace was already nearly being met by the end of the Trump administration. Six days after inauguration, in off-the-cuff remarks, Mr. Biden suggested going to 1.5 million shots a day. Aides quickly pointed out that that was more aspirational than a new, official goal.

A major challenge for the Biden administration is to square its public messaging with what people are seeing in their communities.

“Biden is talking about 100 million vaccinations in 100 days. Excellent,” says Marsha Vanderford, a former communications official at the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “But how does that unroll in conjunction with messages people are hearing that the vaccine clinics have been canceled in their county health department, because there’s no vaccine?”

That’s the kind of disconnect Mr. Biden’s 200-page national strategy on COVID-19 response is meant to ameliorate. Goal No. 1, the plan says, is to restore public trust. In his first two days in office, Mr. Biden signed 10 executive orders addressing the pandemic, including measures to accelerate vaccinations, ramp up testing, aid states with funds and coordination, and safely reopen schools.

Mr. Biden’s personnel choices are also key. Unlike former President Donald Trump, whose White House was marked by high turnover and dysfunction, Mr. Biden has brought in a team of seasoned government hands that he has long known and trusted. Top among them are chief of staff Ron Klain, who spearheaded the White House response to Ebola in 2014, and Jeff Zients, the COVID-19 response coordinator. It was Mr. Zients who led the “tech surge” that fixed HealthCare.gov after its disastrous rollout in 2013.

“By putting in people who are fully qualified to hit the ground running, President Biden can concentrate on that which he has promised the American people, which is to take care of the COVID crisis first, then deal with the economy and racial inequities and climate,” says epidemiologist Kenneth Bernard, who ran the White House office on global health threats under both Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

Mr. Biden, in fact, may owe his election to the pandemic. A 27-page report by Mr. Trump’s chief pollster found that in 10 key states, the coronavirus was the top voting issue, and among those voters, Mr. Biden won by an almost 3-to-1 margin. Mr. Biden also had a clear edge over Mr. Trump “on being seen as honest & trustworthy,” the pollster, Tony Fabrizio, wrote.

Mr. Biden begins his presidency in a bit of a honeymoon, with job approval averaging 55% in major polls and disapproval at 35%, according to Real Clear Politics. In Mr. Trump’s four years in office, his job approval never averaged above 50%.

But the new president can’t rest easy, and he seems to know that. “You have my word,” Mr. Biden declared the week before inauguration, in laying out his COVID-19 plan. “We will manage the hell out of this operation.”

Frequent public communication is essential, experts say. In the Biden era, that’s already in high gear. Press secretary Jen Psaki briefs every weekday, and the president’s COVID-19 response team holds at least three televised briefings a week, including Mr. Zients, chief medical adviser Anthony Fauci, and Rochelle Walensky, the new head of the CDC.

On Tuesday, Mr. Zients announced a plan to ship doses of vaccine directly to pharmacies beginning next week. That’s on top of the administration initiative to send 10.5 million doses a week for the next three weeks to state governments. Since taking office, the Biden administration has boosted the number of doses being sent to the states by 20%.

Mr. Biden “has made COVID-19 the centerpiece of his communication,” says Ms. Vanderford, a consultant on global health communications. “He ties everything else into it – the economic picture, support for workers. And his belief in science is front and center.”

In one sense, after the chaotic Trump years, the bar for perceived success by Mr. Biden is low. All he has to do, it may seem, is listen to his experts, stick to the science, and be straight with the public. But at the same time, Mr. Biden – in promising to solve the biggest global health crisis in more than a century – faces a high bar for success. And in these hyperpartisan times, politics are likely to color public assessments. With Mr. Trump’s second impeachment trial set to begin on Feb. 9, partisanship will ignite anew.

Mr. Biden, a centrist Democrat, is also walking a tightrope in his promises to unite the country – reaching out to Republicans, but also needing progressive Democrats to stick with him. After a two-hour Oval Office meeting Monday with moderate Republican senators, and hearing out their plan for a smaller, $618 billion COVID-19 relief plan, he urged Senate Democrats in a private call Tuesday to go big on pandemic relief, and pass his $1.9 trillion package via a legislative procedure that requires just a simple majority. Democrats control the 50-50 Senate only because Vice President Kamala Harris can break tie votes.

The relief package will be the first major legislative vote of the Biden era, and the new president is playing hardball. But Mr. Biden knows, based on history, that his time may be limited for doing big things. And with variants of the virus emerging in the U.S., there’s added urgency to step up vaccination.

The Biden team is doing all the right things on COVID-19, albeit “six months late, but they had no choice,” says Dr. Bernard. He calls the Trump administration’s vaccine development program, Operation Warp Speed, “brilliant.”

“Advance procurement of a vaccine before it was even proven to be effective was absolutely the right way to go,” Dr. Bernard says. But “in other respects, the Trump response was very bad, in terms of rolling out the vaccination plans at the local level.”

James Curran, a former longtime CDC official, says he’s optimistic about the public health response to COVID-19 going forward.

Under the Trump administration, “there was distrust of science and demeaning of people at the CDC and the FDA [Food and Drug Administration], and unnecessary political criticism of Dr. Fauci and others,” says Dr. Curran, dean of the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta. “But that’s over with now. It’s time to move on.”

A deeper look

A border runs through it: A tale of migration, separation, and reunification

This migration story, told through tears of pain and joy, reveals the human cost of a father’s search for safety with his young son in America.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

This is the story of Gabriel, a Honduran father forced by drug traffickers to flee his home for America, and Nicolás, the 4-year-old son he took with him.

It is a gut-wrenching tale that began with gang threats, continued through their dangerous trip to the U.S. border thousands of miles away, and spawned endless pangs of parental guilt when Gabriel was forcibly separated from his son by guards on that border in 2018 and deported.

Now they are together again, for the time being at least, as Gabriel waits, and waits, for his asylum case to be heard. He is fortunate; few of the 5,500 parents separated from their children have been reunited, and the U.S. government cannot even find nearly 600 of them.

President Joe Biden has announced a task force dedicated to reuniting separated families, and he has pledged an immigration overhaul. In the meantime, Nicolás still asks his father several times a day why he left him behind. “I always try to explain what happened with patience,” says Gabriel. “I just hope one day he will understand.”

A border runs through it: A tale of migration, separation, and reunification

Gabriel tiptoed into his son’s cozy bedroom in New York City, quietly but expectantly. Even though it was the middle of the night, after 2 a.m., he was desperate to take a peek anyway.

Gabriel had just flown in from Chicago and hadn’t been with his son for nearly two years. Now he just wanted to watch his 6-year-old boy breathe peacefully in his sleep, take in how much he had grown, see how his features had changed.

The bedroom reunion in January 2020 was the culmination of a gut-wrenching journey that began with gang threats against Gabriel and his family in Central America, extended through their dangerous trip thousands of miles to the United States, spanned a bewildering thicket of legal battles once they got there, and spawned endless pangs of parental guilt for Gabriel about the decisions he made along the way.

Gabriel was one of the thousands of parents separated from their children at the United States border with Mexico back in the spring of 2018. He’d traveled from central Honduras to the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, where he and his son Nicolás, then a slender 4-year-old with a ready grin, walked timidly toward a U.S. Border Patrol agent at a pedestrian bridge to ask for asylum.

More than 5,500 migrant parents who were taken into custody were separated from their children as part of the U.S. Justice Department’s crackdown on the southern border. A recent lawsuit disclosed that the federal government has been unable to locate nearly 600 parents whose children were taken away from them.

Many of the parents who were deported back to Central America at the time faced an impossible decision: whether to leave their children in the U.S. to pursue asylum on their own, or bring them back home to the very conditions the families risked their lives to escape. Gabriel chose to leave Nicolás in the U.S., where he lived in a children’s shelter for months and eventually moved in with an aunt he’d never met.

As the U.S. transitions to a new president, the legacy of the Trump administration’s immigration policies won’t be easily untangled. President Joe Biden has announced a task force dedicated to reuniting separated families, and has pledged an immigration overhaul that could legalize some 11 million unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S., the boldest amnesty program since 1986. But parents like Gabriel, fortunate enough to be in the U.S. with his son now, still face daunting challenges as they try to apply for asylum in a backlogged system further complicated by COVID-19 court closures.

And being together isn’t guaranteed to last: A recent analysis by the National Reunited Families Assistance Project, a legal cooperative, found that of 2,000 parents who were able to reunite with their children in the U.S., more than 250 currently face deportation orders, putting them at risk of being separated from their children once again.

Gabriel was able to return temporarily to the U.S. from Honduras after a lawyer successfully argued he was entitled to a “credible fear interview,” a legal right that immigration advocates say asylum-seekers were repeatedly denied over the past four years. While awaiting a decision on his claim, he was held in an immigration detention center in the Midwest for nearly three weeks. Authorities found that Gabriel did have legitimate reasons to fear for his life in Honduras, where he says local drug traffickers had killed several people he knew and were threatening him.

After the initial finding, Gabriel flew to New York for the much-anticipated reunion with Nicolás (all family members’ names have been changed at their request out of fear of reprisals). But it hardly went as he had hoped. Nicolás avoided being in the same room with his father for the first three months. Even now, a year later, the boy asks multiple times a day – often in tears – why Gabriel left him behind. Gabriel is concerned his relationship with his son will be forever shaped by their forced separation.

“We can be laughing, playing video games, or wrapping up virtual school and he asks. It’s a kick to the gut,” Gabriel says. “I always try to explain what happened with patience, even though this question regularly comes up two or three times a day.

“I just hope one day he will understand.”

Increasingly difficult choice

Family separation is an old narrative in Latin America, where migration has pulled apart parents and children for generations. Many adults have come to the U.S. seeking work and a better life, or fleeing danger, often leaving behind some or all of their family members for long periods. It is a choice they make – often risky, always emotional.

But the separations under the Trump administration added a wrenching new wrinkle. Asylum-seekers were finding themselves suddenly and unexpectedly separated from the children that they had brought with them. In the past, those who came seeking refuge in the U.S. may have been put in family detention or placed directly into immigration court hearings as a family unit. But the Trump administration, as part of its “zero-tolerance policy,” was putting the children in foster care or government custody while the parents were detained or immediately sent home. The majority of the parents who were deported decided to leave their children in the U.S. rather than subject them to the dangers they initially fled.

It’s the most recent in a long line of difficult calls they’ve had to make as parents, particularly in Central America. Nations such as Honduras and El Salvador have seen organized criminal groups, from local gangs to international drug trafficking organizations, take control of communities and even entire regions. This, coupled with widespread government corruption and entrenched poverty, has forced many parents to make desperate decisions.

“It’s hard to find a safe space in this country,” says Scalabrinian Sister Lidia Mara Silva da Souza, national coordinator for Honduras’ Human Mobility Ministry. She says there are people in Honduras who judge parents for taking their children on the migrant trail – a dangerous journey that can lead to robbery, rape, and even death.

“You only take this route to save your life,” she says. “You only do it with a child if you know the difference between today and tomorrow is the difference between life and death.”

“The perfectly worst time”

The day Gabriel and Nicolás arrived on the U.S. border back in the spring of 2018 marked one year since Gabriel had buried his cousin. He had been killed, Gabriel says, after repeatedly refusing to work for a group of drug traffickers. For years, Gabriel had been hounded by the same men. It could have been his burial, he says.

It was also the day that Gabriel was sure would mark a new beginning. “I think I exhaled for the first time in my son’s life,” Gabriel recalls of his initial conversation with the U.S. Border Patrol agent. The officer asked for a visa, and when Gabriel told him he was seeking asylum, he was gently ushered away for what Gabriel expected to be an interview process.

Looking back, that spring day is when his nightmare began.

“I didn’t think about anything in the moment that I left,” says Gabriel of his decision to flee Honduras. But “I left at the perfectly worst time,” he says, referring to the tougher U.S. enforcement along the border.

Gabriel is from a village in a hilly department, or province, in central Honduras. Homicides in the region more than tripled between 2005 and 2014. Unlike many urban centers, his rural town isn’t overwhelmed by rival gangs charging extortion fees or controlling territories. It’s home to drug traffickers, who have been allegedly bolstered for years by powerful local politicians profiting from the illegal trade.

It’s been more than seven years since Gabriel was first approached by criminal elements in town: first invited, then cajoled, and finally threatened if he didn’t work for them, he says. They recruit residents to be “mules,” carrying drugs north, or to be lookouts. Gabriel always refused, but the implications of his resistance became more serious as he watched neighbors – and his cousin – murdered for the same reason, he says.

In early 2018, when a local family, including the children, was killed after the father declined to work with drug traffickers, Gabriel felt as if he was putting his own family at risk. He was living at the time with his parents, his girlfriend, and their two children. So he moved out of his father’s home to a small house a four-hour hike up the mountain.

Not long afterward, his father suggested he should do more than hide. He needed to leave.

Unexpected goodbye

It took Gabriel and Nicolás two weeks to cross through Guatemala and Mexico before arriving at the U.S. border in 2018.

Gabriel had decided he wasn’t going to risk staying with his son at any shelters along the way in Mexico, since migrants can be easy prey for thieves, and informants are rumored to share the identities of migrants with criminal elements in Central America. He saved up to pay for buses and small hotel rooms instead.

“[Nicolás] never went hungry. Everything I had I spent on feeding him and making sure he felt safe,” says Gabriel, who went days without food himself.

After their encounter with the Border Patrol agent, they spent two days together in a short-term processing center. Then agents came for Gabriel and his son. Nicolás clamped onto his father’s leg, crying. He seemed to be aware of something that Gabriel himself says he couldn’t see in that hectic moment: This was goodbye.

Gabriel was deported one week after crossing the border. It wasn’t his first deportation. He had tried applying for asylum in 2015, but was denied. Because he had a previous deportation order, U.S. authorities told him he wasn’t eligible this time around. But experts say he should have been issued a “withholding of removal” order, which can be given by an immigration judge when someone has demonstrated a high chance of persecution at home.

Nearly two frantic weeks passed before Gabriel could find out anything about his son: that he was safe, that he had been fed, and – most devastatingly – that he believed his father had intentionally left him behind. For several months, Nicolás was in a center for children in the Chicago area. But other than a few tear-filled phone calls, Gabriel says he was given little information on when his son would be released to his sister, who had agreed to be his guardian in the U.S. “I knew family members had been killed” over the years in Honduras, says his sister Veronica, who came to the U.S. in 2014 and applied for asylum, which is still pending.

“When something like that happened, I’d get a call or a message, but what could I do from the U.S.? Just brace myself for the pain of what my family was going through.”

She says it took nearly four months before she was allowed to take custody of Nicolás, despite showing that she could pay for a ticket to fly him to her home and providing birth certificates and other documentation proving they are related.

Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the Immigrants’ Rights Project for the American Civil Liberties Union, sees the U.S. government’s family separation policy in 2018 as a “historic moral stain” on the country. “Part of the immigrant experience is to have to make big sacrifices,” says Mr. Gelernt. “That’s what seems so unfair about what happened in the U.S. You already had one separation that was voluntary from the rest of your family, just to get here and have your kid taken away.”

Some U.S. officials and hard-line immigration reform groups believe this is as it should be. While many law enforcement officials recognize the difficult situations families and minors are fleeing in places such as Honduras, the U.S. simply can’t take in everyone who shows up on its doorstep.

“There have to be consequences to violating the law,” says Jerry Robinette, a former Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent in San Antonio.

The cost and logistics of handling families that show up at the border can be particularly difficult. It requires detaining, housing, and then coordinating the deportation of migrants with the countries from which they came, Mr. Robinette notes.

“Dealing with family units or whenever you encounter a juvenile ... it creates an added stress on the system,” because the rules and requirements for dealing with minors are more strict and involve more manpower, he says.

The number of families trying to enter the U.S. on the southern border initially continued to rise even after the implementation of the family separation policy. The U.S. Border Patrol apprehended more than 474,000 family units and nearly 76,000 unaccompanied youth along the southwest border in fiscal year 2019. These marked the highest numbers of apprehensions since the U.S. began keeping track in 2008. Those numbers fell dramatically in 2020, however, when borders across the region closed due to concerns about COVID-19.

Some advocates of a more secure border believe the flood of families seeking asylum was part of a deliberate calculation. As the U.S. stepped up immigration enforcement, more migrants were trying to come in legally by applying for asylum, they argue.

The Trump administration sought to address this in a number of ways, including by requiring asylum-seekers to await their U.S. court hearings in Mexico. President Biden suspended new enrollment in this program, the Migrant Protection Protocols, during his first week in office, but there are still 67,000 asylum-seekers in the MPP, including families, many still languishing in Mexico.

Long-term trend

Many believe the demographics of migration are changing permanently. Gretchen Kuhner, director of the Institute for Women in Migration, a Mexican nongovernmental organization, says families will continue to be a substantial part of the migration north – and governments on both sides of the border need to focus on policies that address this reality, not wring their hands over the added challenges it presents.

“There have been so many complaints about families,” she says. “But the reality now seems to be if you’re going to [migrate], it’s best to travel as a family unit to avoid long-term separation.”

Too many families have watched loved ones make the trek north and disappear. Each May, the church that Rosa Nelly Santos attends in northern Honduras celebrates the “day of the family.” A few years ago, amid the festivities, she looked around the room and asked herself, “Who here doesn’t have someone missing or living abroad or outside of the home?” she recalls. “Our families and our communities aren’t complete. There’s always someone missing.”

Ms. Santos knows something about family separation. She’s president of the Family Committee for Disappeared Migrants of El Progreso, or Cofamipro, a 20-year-old group made up mostly of mothers who have lost loved ones on the trail north.

Leticia Martínez is one of them. Her daughter has been missing for 14 years. A single mother of three, she took off for the U.S. in search of employment, last making contact in October 2006. She told her mother she was being pursued by organized criminals while traveling through Mexico.

Ms. Martínez has raised her grandchildren as if they were her babies. “I’ll never let them leave,” she says. “I can’t manage to lose another child without knowing where or how or why.”

While the circumstances behind separations of members of Cofamipro may be different from families like Gabriel’s, both highlight the reasons Hondurans migrate and the anguish their decisions can engender.

“Children need to feel safe,” says Elizabeth Kennedy, a U.S. social scientist who has worked in the region for years doing research on why migrants leave Honduras and El Salvador. Even when a parent leaves for the purpose of keeping a child safe, it can backfire. “I have documented again and again that children view this like they’ve been abandoned, even though that’s the furthest thing from a parent’s intention.”

“I want to do this right”

Nicolás is now enrolled in second grade, fluent in English, and “really big,” says Gabriel. In many ways, his son’s life is exactly what he dreamed about all those years when he was consumed by concerns about Nicolás’ safety and his family’s future in Honduras.

“The best thing is that he’s healthy. He gets to be a kid, he’s in school, he’s learning so much,” says Gabriel, sounding like a proud father. “He’s just happy here.”

It took a while to get to this point. When they first reunited, “I thought he was going to be the same kid as always. But once he started talking more I could understand [our relationship] would never be the same. He asked why I left him behind. Why I didn’t love him. Why the police took me but left him,” he says.

Yet Gabriel insists it was the right decision to bring Nicolás with him in 2018, and to leave him in the U.S. alone. “Security is a beautiful thing,” he says.

Gabriel is still dealing with a lot of his own emotions. He tries to cobble together informal jobs while navigating the U.S. legal system. One day in October he left his sister’s house at 5 a.m. to make a 9 a.m. court appearance. When he arrived at the venue, he was told there were no hearings because of the pandemic. Would this jeopardize his status in the U.S.? Would there be any way to register he had shown up?

He called a handful of lawyers who said they’d need thousands of dollars in retainers to help him. Finally, in December, he received a message that he was scheduled for a new court date in May. It feels like a long time to wait.

“I want to be able to work in this country. I want to do this right,” he says. That’s one of his biggest takeaways – and frustrations – from the long saga his family has survived the past two years. He still has a 5-year-old daughter back in Honduras. He’d like his children to be together in one safe place.

“I don’t know what to do to bring her here. Besides the migratory path being incredibly dangerous, I understand it turns out better to do things legally from the start,” he says. “We just need to know how: What are the steps to take?”

Patterns

Can diplomacy deter Iranian nuclear ambitions a second time?

President Biden hopes to revive the 2015 Iran nuclear deal. But the challenge, our columnist notes, is to heal old wounds and rebuild trust before Tehran builds an A-bomb. Time is short.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ned Temko Correspondent

Joe Biden has long wanted to put the Iran nuclear deal back together. But now that he is in the White House, with a chance to do that, time seems to be running out.

Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the agreement – designed to curb Iran’s ability to build a nuclear bomb – almost three years ago. Tehran began ignoring the provisions of the deal a year later. Washington now says it will return, if Iran promises to abide by the agreement’s terms. Iran says it won’t do that until the U.S. rejoins.

And meanwhile, the nuclear clock is ticking. If the Iranians continue to disregard the 2015 agreement, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said this week, they could be only a matter of weeks away from having enough nuclear material to make a bomb.

The Israelis are getting itchy too. They may be bluffing, but Israel has announced publicly that it is updating plans for military action.

The new U.S. administration is working on plans to negotiate a new, and much broader, deal with Iran. But that will take time. For now Washington simply wants to revive the 2015 agreement. That will mean stopping the clock before Tehran can have the bomb.

Can diplomacy deter Iranian nuclear ambitions a second time?

It has the feel of high-pressure tournament chess, the players competing not just against each other, but the unforgiving tick of the clock. Only the Middle East’s current preoccupation is no game; it’s an international political face-off with major security implications for the region and beyond.

At issue is whether the Islamic Republic of Iran will complete its decadeslong quest to build a nuclear bomb – a security challenge the new administration in Washington is hoping to forestall in return for lifting the “maximum pressure” sanctions that former President Donald Trump put in place.

The reason why tensions have ratcheted up in recent days? Deeply discouraging signals about this U.S. strategy from both Iran and from Israel, Tehran’s most powerful regional rival.

The Iranians have so far rejected the idea of any quick diplomatic fix. They’re accelerating production of the material needed for a weapon. Israel, meanwhile, has taken the extraordinary step of saying publicly that it is updating plans for military action, and has reiterated its determination not to let Iran become a nuclear-weapons state.

The main problem, however, is the ticking of the clock.

Iran is now estimated by U.S. officials to be a few months away from “breakout point,” the moment at which it will have amassed enough weapons-grade fissile material for a bomb.

Mr. Biden’s foreign policy and security team is seeking urgently to stop the clock, giving Washington time to put together a diplomatic solution addressing concerns and objections on all sides. The two-stage package that Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan are working on will take many months, at the very least, to achieve.

That package would first revive the 2015 Iran nuclear deal under which Tehran accepted a series of limits and verification mechanisms on its nuclear program in return for relief from earlier sanctions. The Iranians were complying, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency, until Mr. Trump pulled the United States out of the agreement in May 2018 and imposed new sanctions.

In stage two, the administration would attempt something Iran has long rejected, but which Israel and many members of the U.S. Congress would like to see. That would be a wider agreement, going beyond Iran’s nuclear program, to set limits also on its ballistic missile program and to constrain its military interventions across the Arab world, from Yemen to Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon on the Mediterranean.

But the focus now is stage one, reviving the 2015 agreement, and even that is running into obstacles.

On the major substance, the Americans and Iranians actually agree: Iran’s return to the 2015 limits (which it began ignoring one year after the U.S. pulled out of the deal) in exchange for Mr. Biden lifting the Trump sanctions.

But Washington wants Iran verifiably to halt and reverse its violations of the 2015 limits – on the enrichment of uranium and addition of new centrifuges – before it lifts the sanctions. Iran is insisting that, since it was Washington and not Tehran that abandoned the agreement, the Americans should rejoin and end the sanctions first.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, for his part, has long opposed even the 2015 agreement as an insufficient guarantee against Iran going nuclear. Israel will, at a bare minimum, want to see evidence that the Iranians are reversing course before the Americans ease sanctions pressure.

And there are domestic political pressures to reckon with as well. Israelis are going to the polls in March, and the Iranians in June. In both countries, the prevailing political winds favor the foreign-policy hard-liners.

The Biden administration will hope cooler heads in both Iran and Israel prevail.

After all, the Iranian economy is suffering very badly from the Trump sanctions; and military action is not something Israel can embark on lightly.

Beyond the political costs of a military strike, including the certain opposition of Washington, Israel’s most important ally, it would also raise practical issues. Iran has dispersed its nuclear facilities and sought to protect them against bomb or missile attacks. And while a targeted attack could delay the Iranians’ breakout point, Iran could well retaliate through its Hezbollah militia allies in southern Lebanon, whose missile batteries are capable of hitting Israel’s main towns and cities.

In his first remarks as secretary of state, Mr. Blinken last week made no reference to Iranian or Israeli reticence about U.S. plans, simply reiterating that if Iran was verified as having returned to “full compliance” with the 2015 agreement, the U.S. would do the same. That, he made clear, was going to take time.

But in a television interview this week, he pointed to the more immediate challenge.

He warned that if the Iran nuclear deal remained a dead letter, with Washington outside and Tehran disregarding its provisions, Iran could come “within weeks” of breakout point.

In other words, the clock is ticking.

Graphic

Why California bill seeks to hire older police officers

How do you recruit for good judgment and wisdom? Improving public safety in America may hinge on the answers. We look at what research tells us about hiring better police officers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

Jacob Turcotte Staff

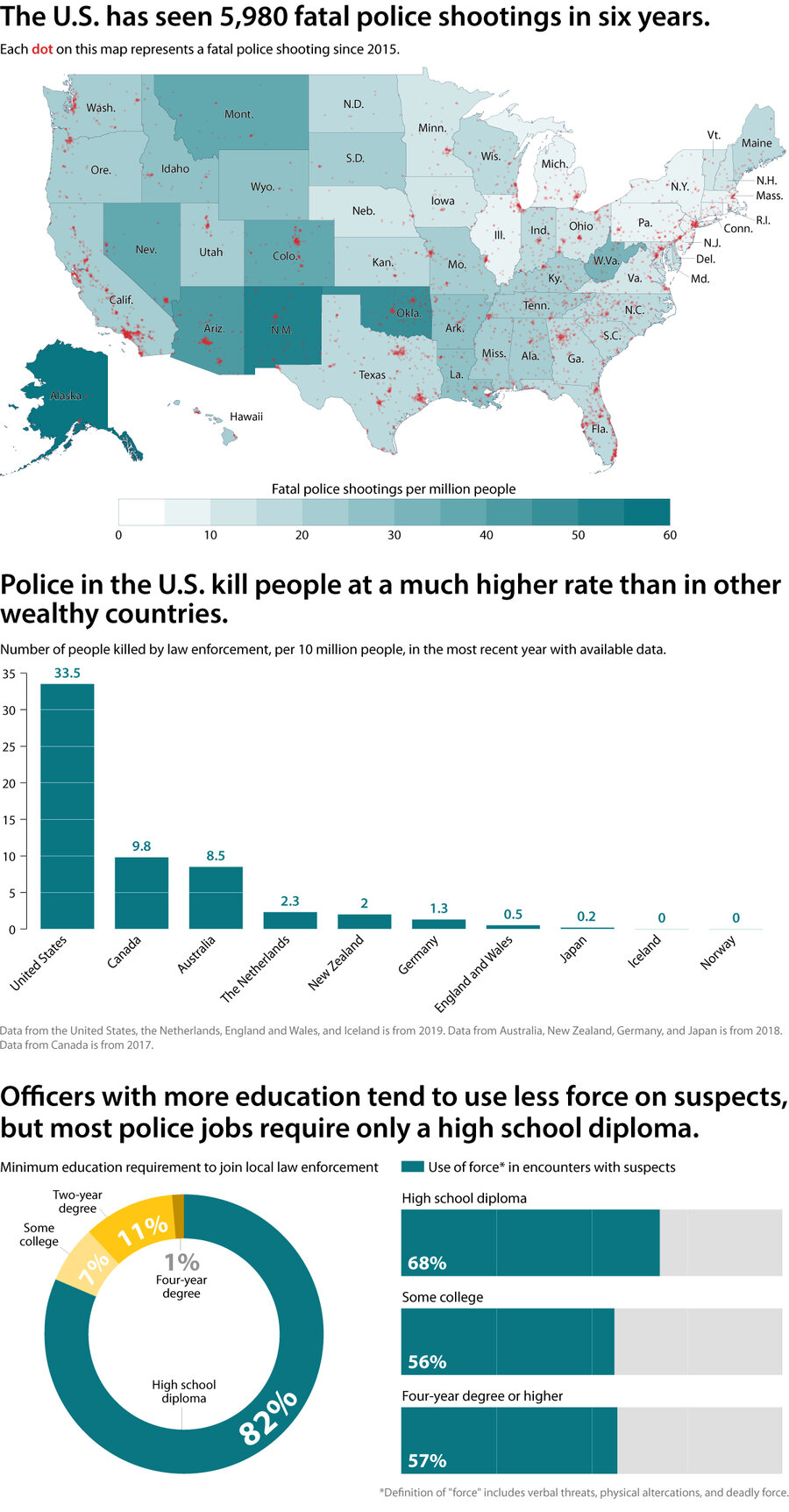

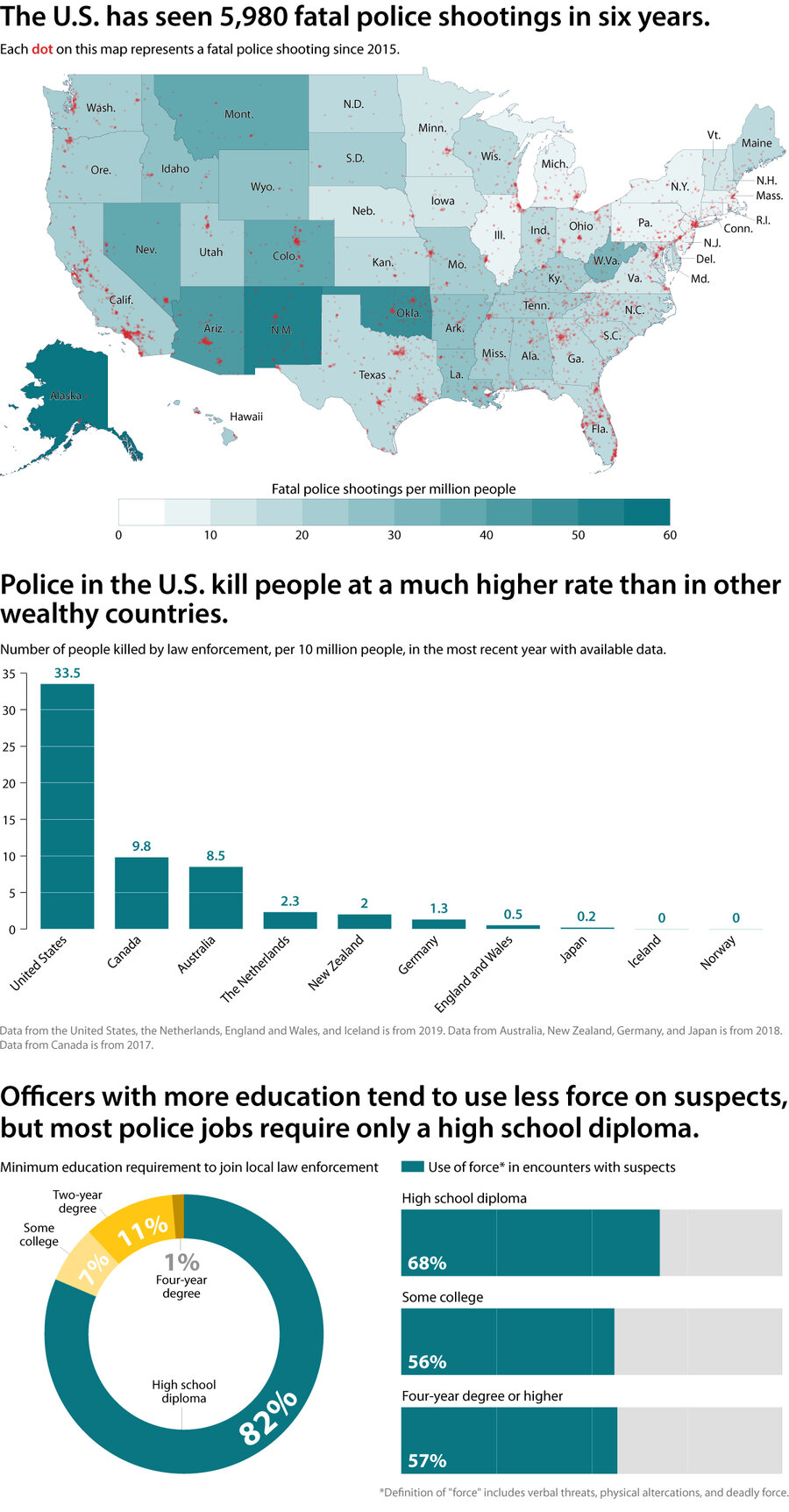

Few U.S. police agencies require rookie officers to hold a college degree. Yet college-educated officers use force less often and face fewer public complaints and disciplinary actions than those without a bachelor’s degree.

In California, where existing law allows an 18-year-old with a high school diploma to pursue a police career, a state lawmaker aims to raise the hiring bar. Assembly Member Reggie Jones-Sawyer has introduced a bill to require either a four-year degree or a minimum age of 25 in order for someone to carry a gun and badge.

The Democrat from Los Angeles, who leads the Assembly’s public safety committee, has called his measure an attempt to ensure the hiring of “only those officers capable of high-level decision-making and judgment in tense situations.” The bill refers to science showing that young adults’ cognitive development – including impulse control – is an ongoing process into the mid-20s.

Although no one argues such hiring rules alone would eliminate controversies over the use of force, research suggests it would reduce them. Studies have also shown that police officers with college degrees more readily embrace fresh approaches to the job – from community policing to procedural justice – that could further repair the profession’s image.

Why California bill seeks to hire older police officers

Few police agencies in the United States require rookie officers to hold a college degree to join the force. The status quo persists even as an ample body of research suggests that college-educated officers use force less often and face fewer public complaints and disciplinary actions than those without a bachelor’s degree.

In California, where existing law allows an 18-year-old with a high school diploma or its equivalent to pursue a police career, a state lawmaker aims to raise the hiring bar. Assembly Member Reggie Jones-Sawyer has introduced a bill that would require new officers to either earn a four-year degree or turn 25 years old before they could carry a gun and badge.

The Democrat from Los Angeles, who leads the Assembly’s public safety committee, has called his measure an attempt to ensure the hiring of “only those officers capable of high-level decision-making and judgment in tense situations.” The bill refers to neurological studies showing that young people’s cognitive development – including in the areas of the brain governing impulse control and working memory – continues into the mid-20s.

Most states set minimum ages from 18 to 21 for police eligibility, and four – Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, and North Dakota – require a bachelor’s degree or the equivalent based on education and experience. At least a dozen other states mandate some college education.

The Washington Post; Prison Policy Initiative; California State University, Fullerton Center for Public Policy; Police Quarterly

George Floyd’s death in May at the hands of Minneapolis officers has amplified criticism of police for using excessive force. California enacted a law in January that tightened its use-of-force standards. Mr. Jones-Sawyer has asserted that recruiting more college-educated or older rookie officers could save cities millions of dollars in payouts arising from excessive force lawsuits. In Los Angeles, police misconduct cases cost the city $190 million from 2005 to 2018.

California’s law enforcement organizations remain circumspect on the proposed hiring changes. Leaders with the state’s peace officers and police chiefs associations, while broadly supporting stronger educational standards for new officers, have voiced concerns that the bill would hinder recruiting efforts in low-income and minority communities.

A 2017 report on the effects of higher education on policing offers a different perspective on the bill’s potential value. The study surveyed more than 950 law enforcement agencies across the country that serve areas ranging in population from less than 2,500 to more than 1 million.

The research suggests that the lower rates of use of force among college-educated officers – and the smaller number of liability lawsuits filed against them – can enhance the reputation of police in disadvantaged and minority communities. Related studies have shown that police officers with college degrees more readily embrace new approaches to the job – including community policing and procedural justice – that could further repair the profession’s image.

The 2017 analysis revealed that the average salary of officers with four-year degrees runs 2.5% to 5% higher than their counterparts, and 15% or higher in some cases. About one-third of the agencies surveyed cited an inability to afford bigger salaries as a reason for forgoing a college-degree requirement.

On the other hand, the report also found that officers who graduated college are more adept at writing reports. Underappreciated as a part of police work, the skill can improve the rigor of investigations, translating into fewer false confessions and wrongful convictions – and fewer lawsuits against officers.

The Washington Post; Prison Policy Initiative; California State University, Fullerton Center for Public Policy; Police Quarterly

Interview

How The Weather Station draws inspiration from the outdoors

Where does creativity come from? Songwriter Tamara Lindeman – aka The Weather Station – learned that the process can be as natural and easygoing as spending time in the forest as a child.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Staff writer

Tamara Lindeman started recording music at the end of a brief but successful acting career. Creating songs was intuitive, effortless. But the critical acclaim for her second album in 2011 had an effect on her that was akin to when a tightrope walker suddenly looks down midstep.

Because the songwriter didn’t understand how she’d come up with those compositions in the first place, she had no idea how to do it again. Ms. Lindeman eventually realized that the secret was to reproduce the carefree state she experienced in the forest during her childhood. Now she spends mornings with the guitar or piano, just singing whatever comes to mind.

“There is this beautiful thing that happens in playing an instrument where it just suddenly turns off your mind,” she explains. “I might sing a bunch of things that feel unrelated and not understand how they connect until months later.”

Recording as The Weather Station, Ms. Lindeman features the outdoors prominently on her fifth album, “Ignorance,” debuting on Feb. 5.

“The economy of her language reminds me of Joni Mitchell,” says music writer Grayson Haver Currin, adding that her precocious gift for lyric-writing was evident from the very start. “She’s a generational talent.”

How The Weather Station draws inspiration from the outdoors

Tamara Lindeman has been singing as long as she can remember. As a child, she liked to venture alone after school into the 25 acres of woods near her home in Shelburne, Ontario, and sing. She’d serenade the trees, plants, and barely glimpsed creatures. Her own secret garden, filled with song. Then the bittersweet peal of her mother’s bell would beckon her home for dinner.

“I could be a shy kid,” says Ms. Lindeman, who now lives in Toronto, in a phone interview. “The natural world was like a friend to me and it was a real relationship.”

It’s fitting that when she began her career as a songwriter, she adopted the moniker The Weather Station. The outdoors figure prominently on the fifth Weather Station album, “Ignorance,” debuting on Feb. 5. Ms. Lindeman’s writing was galvanized by a 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that suggested a 1.5 degree Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) increase in global temperature will affect sea levels, biodiversity, and ecosystems, which she found alarming.

Yet the artist eschews the preachiness of so many protest anthems in favor of a more personal outlook on the environment. The album exemplifies why Ms. Lindeman is revered by music critics as a lyricist. Whether she’s writing about friends, parents, lovers, or the natural world, she explores why those relationships are meaningful.

“She’s a generational talent,” says Grayson Haver Currin, a music writer for outlets including Pitchfork and NPR. “I’m always very drawn to songwriters who are very specific ... where the details can, instead of feeling specific just to the writer – which they are – make you feel as if the song is about you.”

Find a way to be carefree

Ms. Lindeman first started recording music at the end of a brief but successful acting career. (Her credits, using the stage name Tamara Hope, include playing the titular queen in HBO’s “The Royal Diaries: Elizabeth I – Red Rose of the House of Tudor” and starring alongside Tilda Swinton in “The Deep End.”) Creating songs was intuitive, effortless. But the critical acclaim for her second record, “All of It Was Mine” (2011), had an effect on her that was akin to when a tightrope walker suddenly looks down midstep. Because the songwriter didn’t understand how she’d come up with those compositions in the first place, she had no idea how to do it again. Ms. Lindeman eventually realized that the secret was to reproduce the carefree state she experienced in the forest during her childhood. Now she spends mornings with the guitar or piano, just singing whatever comes to mind.

“There is this beautiful thing that happens in playing an instrument where it just suddenly turns off your mind,” she explains. “I might sing a bunch of things that feel unrelated and not understand how they connect until months later.”

When she hits on something worthy, the work of honing the idea begins. The challenge is finding a narrative balance between telling a story and expressing thematic ideas. There’s also the tricky negotiation of folding a lyric into a melody.

“A lot of writers go for the sound of the word in the song over the meaning of the word,” says the artist. “I’ll go for the meaning of the word over the sound every time.”

Ms. Lindeman admits she isn’t a powerhouse vocalist – on karaoke night she’s not going to select Mariah Carey – but she has an appealing, naturalistic delivery that’s emotionally authentic.

“So much beauty in the world”

Weather Station albums, produced with a coterie of musicians, offer listeners the ability to eavesdrop on the songwriter’s most intimate thoughts. It’s one of the reasons Ms. Lindeman's work has been endlessly compared to that of another Canadian songwriter.

“The economy of her language reminds me of Joni Mitchell,” says Mr. Currin, adding that her precocious gift for lyric-writing was evident from the very start.

But Ms. Lindeman, who says she wasn't influenced by her iconic predecessor, sees herself charting her own course. On “Ignorance,” the Weather Station sound has been upgraded from lo-fi folk-rock to high-fidelity art rock. The musician complements her piano, organ, and guitar with saxophone, flute, strings, and percussionists playing propulsive patterns. That lush sonic palette augments the song “Atlantic” in which the songwriter watches a sunset near the ocean. Her thoughts keep returning to the doom-laden headlines about the environment. “I should get all this dying off my mind,” she sings.

“I felt this joy,” she recalls. “And I was like, ‘Why do I keep myself in such a dark place when there’s so much beauty in the world?’

“Facing the climate crisis and starting to become involved in some very modest measure of activism has allowed me to re-reconnect

a little bit.”

The search for connection crops up often in Ms. Lindeman’s conversation – it’s also an underlying theme on the album. “Subdivisions” describes leaving someone without telling them by embarking on a spontaneous road trip. On “Robber,” she compares capitalism to an impersonal relationship with a heist artist. “Parking Lot” finds the touring musician marveling at a bird singing the same song repeatedly when she’s dreading the prospect of baring her soul at yet another show that night. For her, writing these songs is cathartic.

“Sometimes I write songs without fully knowing what I need to say,” says Ms. Lindeman, adding that she’s had the experience of songs telling her things that she didn’t want to know.

“The songs,” she says, “are places of mystery.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How honesty helps heal during a pandemic

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One little-noticed news story during the pandemic has been a wave of protests by health workers in Africa. One good example of this upwelling for honesty and transparency in response to the coronavirus comes from Congo, where last year a group of health care workers went on strike after not being paid for three months – and after suspicious diversion of government money for fighting COVID-19.

“COVID-19 is not just a health and economic crisis. It is a corruption crisis,” says Delia Ferreira Rubio, chair of Transparency International. A study of pandemic-related graft by the Berlin-based watchdog found that “fighting corruption is key to ensuring better preparedness for crises responses.” Transparency in government is key to the fair and efficient management of emergencies, the study states, “as it helps ensure that the resources reach their intended beneficiaries.”

Often it is local health workers who best understand the link between health outcomes and the need for integrity in the health industry. The protests in Africa and elsewhere are signs of how the pandemic has shown that honesty is necessary for healing.

How honesty helps heal during a pandemic

One little-noticed news story during the pandemic has been a wave of protests by health workers in Africa. In Zimbabwe, nurses went on strike for more pay after reports of health care money being spent on expensive cars for officials. Doctors in Sierra Leone went on strike for similar misuse of health funds. In South Africa, health workers have staged rolling protests even as investigators probe massive corruption in the purchase of personal protective equipment.

One good example of this upwelling for honesty and transparency in response to the coronavirus comes from Congo, the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa.

Last year, a group of health care workers in Congo went on strike after not being paid for three months – soon after Prime Minister Sylvestre Ilunga Ilunkamba claimed he had spent $10.7 million in fighting the virus. His own frontman on COVID-19 said he had received only $1.2 million.

In addition, Denis Mukwege, the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize laureate and a doctor, resigned as head of a coronavirus task force in Congo, citing organizational problems. He later advocated a “break” with corruption and “the men who have compromised themselves in various crimes.” (Nearly 4 in 5 Congolese believe that all or most parliamentarians are involved in corruption, according to a recent poll by Transparency International.)

Last Friday, Prime Minister Ilunkamba was forced to resign, a day after the National Assembly censured him for incompetence. His ouster was seen as a victory for the anti-corruption efforts of President Félix Tshisekedi.

Africa is not the only place where the pandemic has pushed people to demand integrity in the management of the crisis. Even before COVID-19, for example, 28% of health-related corruption cases in the European Union were related to procurement of medical equipment. The continent has seen heightened pressure to prosecute those who siphon off money for the crisis or seek bribes in the delivery of health goods.

“COVID-19 is not just a health and economic crisis. It is a corruption crisis,” says Delia Ferreira Rubio, chair of Transparency International. “The past year has tested governments like no other in memory, and those with higher levels of corruption have been less able to meet the challenge.”

A study of pandemic-related graft by the Berlin-based watchdog found that “fighting corruption is key to ensuring better preparedness for crises responses.” Transparency in government is key to the fair and efficient management of emergencies, the study states, “as it helps ensure that the resources reach their intended beneficiaries.”

Often it is local health workers who best understand the link between health outcomes and the need for integrity in the health industry. The protests in Africa and elsewhere are signs of how the pandemic has shown that honesty is necessary for healing.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The power of Truth

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Blythe Evans

God’s truth is a powerful force for good, always present to light the path to solutions, healing, and harmony.

The power of Truth

Daniel Webster, a renowned statesman of the 19th century, said, “There is nothing so powerful as truth.” Some time later, his fellow citizen of New England and the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, took this idea to the next level when she wrote, “Truth is the power of God which heals the sick and the sinner, and is applicable to all the needs of man” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 259).

Divine Truth is the foundation of reality, and it annuls lies that obscure the path to justice, harmony, and goodwill. It enables us to find solutions.

Jesus Christ of Nazareth demonstrated this more powerfully than anyone who ever lived. When he was confronted with the evidence of God’s children being ill or lacking integrity, he saw it as a lie about them. He knew that everyone is the loved offspring of God, good, and therefore, in reality, is whole, pure, and upright. On that basis, he saw past the lie that God created His sons and daughters susceptible to disease or dishonesty. As he knew, spoke, and proved the power of divine Truth, this resulted in the healing of diseases and difficulties of every type.

Jesus also confronted the lie that jealousy and hatred could prevail over justice and compassion. His steadfast understanding that God, Truth, is supreme and thus overcomes and removes all unlike Himself, enabled him to triumph over the vitriol and violence aimed at him.

Jesus’ intent was that his followers should continue to use the power of Truth to overcome sickness and sin as he did (see John 14:12). And in her devotion to understanding his example, Mrs. Eddy discovered that the powerful truth that Christ Jesus taught and practiced is still applicable today. Mrs. Eddy wrote, “Truth casts out error now as surely as it did nineteen centuries ago” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 495).

I leaned on Truth when I was confronted by an outright lie some years ago following a real estate transaction. The contract stipulated that after the sale had closed, our family would continue to live in the house for an additional six weeks, paying rent to the new owner. However, even though he had agreed to this, the new owner started disruptive renovation work on the property. It seemed to us that his intent was to drive us out sooner than agreed upon.

Then, not long after this started, I got a call from an attorney warning me to stop interfering with the renovation work. Having in no way attempted to interfere with the work, I was outraged that the other party was not only disregarding the contract stipulations, but also lying about my activities. I could hardly contain myself.

But it was quickly evident that reacting angrily to the lies wasn’t going to bring progress. I realized that the only way to find an answer here was through prayer, turning to the power of divine Truth, as I had usually done in my life when solutions were needed.

So I affirmed that God, Truth, has an answer for every difficulty, and that nothing is outside the realm of Truth’s resolution. This calmed me, and I humbly asked God to show me how to handle this situation.

I realized I had to see this person’s true identity as the spiritual man of God’s creating, not a litigious, self-centered, and offensive mortal. As the likeness of God, everyone’s true nature is to express Truth, integrity, and justice, and overcome the pull to lie, cheat, or bully.

My prayers also helped me recognize that, spiritually speaking, I, my family, and this man and his family actually abode in the kingdom of heaven, defined in Science and Health in part as “the reign of harmony in divine Science” (p. 590). This reign of harmony is forever intact.

As these spiritual insights brought me a sense of peace, the idea came to write a factual and detailed correction to each accusation that was leveled at us. That quieted things down, and soon the matter was resolved and we all moved on, to my relief and gratitude.

No matter what lies spring up and confront us individually or collectively, we can find in Truth, God, a powerful force for good that is always available. As the biblical Psalmist said: “For the Lord is good. His unfailing love continues forever, and his faithfulness continues to each generation” (Psalms 100:5, New Living Translation).

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article in the weekly Christian Science Sentinel on the healing effect of acknowledging God’s existence and power titled “Everyday Spiritual Self-Defense,” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

When winter turns watery

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about the GameStop saga and what it says about American efforts to champion economic equality.