- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Canada doesn’t give paid sick leave. Can small businesses change that?

- To help Venezuela, Biden is urged to put people before politics

- Biden to allies: Enduring values stand up in a changed world

- Eye in the sky: Did Baltimore’s aerial surveillance program go too far?

- In a first for Ecuador, victims of modern-day slavery find justice

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Where 911 calls aren’t always answered by police

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Denver had an idea: What if the city didn’t send police into situations for which they don’t have proper training? Sounds logical, right? Yet over the years, police have increasingly been required to respond to all manner of 911 calls, even the noncriminal ones. The result has been not only strain on the force, but also incidents that sometimes escalated violently.

So Denver created the Support Team Assistance Response (STAR) program. It grew out of last year’s protests calling for police reform. But rather than gravitating toward the polarized extremes of the issue, it sought the space in the middle where solutions often start.

The police handed over response to mental health calls, substance abuse calls, or other low-level issues. Instead of law enforcement officers, unarmed health care workers responded. A recent report found that STAR handled 748 incidents in six months. None resulted in arrests, jail time, or even required police assistance. Now, the police chief himself is looking to add more money to the program. “I want the police department to focus on police issues,” Chief Paul Pazen told the Denverite.

Added Matthew Lunn, an author of the report: “I think it shows how much officers are buying into this, realizing that these individuals need a focused level of care.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Canada doesn’t give paid sick leave. Can small businesses change that?

With paid sick leave, are small business owners always the “losers”? Some Canadian entrepreneurs are pushing for it because, they say, it is a benefit to everyone – employer and employee alike.

Carolina Jimenez says people are shocked to learn that, as a part-time nurse in Toronto, she doesn’t have paid sick days. “People audibly gasp,” she says. She could scrape by if sick, but workers depending on each hour of their paychecks have to make impossible choices.

Now, amid the pandemic, a growing chorus of Ontarians – including long-time advocates for workers’ rights and unions, but also doctors, public health officials, and Ontario mayors – are turning up the pressure on the province to provide paid time off when employees are ill.

Data shows many Ontario employees are going to work sick. In Peel, one of the worst-hit areas for COVID-19, the public health agency released a study showing that 25% of workers went to work with symptoms between August and January. Local mayors called on the provincial government to adopt sick days. So did a group representing 34 public health units of Ontario.

“Business interests are often touted as the main reason behind lack of action on measures like paid sick days,” says small-business owner Jessica Carpinone, who is part of a group pushing Ontario to legislate permanent paid sick leave. “But it is in our interest as business owners to employ a healthy workforce, period.”

Canada doesn’t give paid sick leave. Can small businesses change that?

Even before the pandemic, Ottawa bakery Bread by Us went beyond the number of paid sick days that Ontario requires. Not that it was hard to do – under province law, employers don’t have to provide any paid sick days at all to workers.

But when the bakery gradually re-opened after a pandemic shutdown last spring, co-owner Jessica Carpinone decided to go big, despite tight margins, and institute unlimited sick days for her dozen employees.

It’s not just the right thing to do, she says. It makes the best business sense.

She’s joined a growing chorus – including long-time advocates for workers’ rights and unions, but also doctors, public health officials, and Ontario mayors – who have turned up pressure on the province to mandate paid time off when employees are ill.

Among them, it’s the voice of small-business owners like Ms. Carpinone who may shift the debate away from the binary thinking that more employee benefits are employer losses. The long fight for workers’ rights has moved to the forefront due to a pandemic that has exposed glaring inequities, with low-paid, often essential workers most at risk of COVID-19 and the least likely to have days off. But that fight has also aligned with a public health message that essentially says that everyone benefits from a workforce with paid sick days – from employees to customers to companies that mitigate risk and maintain their reputations as safe places of business.

“Business interests are often touted as the main reason behind lack of action on measures like paid sick days,” says Ms. Carpinone, who is part of the Better Way Alliance, a group pushing Ontario to legislate permanent paid sick leave for all. “But it is in our interest as business owners to employ a healthy workforce, period. ... And I believe that if my friends, owners of ice cream shops, coffee shops, restaurants, can implement these measures, there is no excuse.”

“You’re not going to wait until it blows up”

“Stay home if sick” has been the dominating guideline across the globe since a pandemic was declared March 11, 2020. But nearly a year later, that principle remains out of reach for many.

In Canada, provinces are in charge of sick pay itself, and 58% of workers have no access. That number rises to 70% of workers who earn less than $25,000 annually, according to federal figures.

The federal government offers workers long-term sick leave, including time off for family caregiving that in many ways makes it a global model, says Jody Heymann, founding director of the WORLD Policy Analysis Center at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Fielding School of Public Health. That gives Canadians more security than many Americans: the U.S. is one of just 11 countries that, outside the pandemic, offers no policy at the federal level on sick leave.

“But Canada does have important gaps to fill,” she says.

Canada implemented a federal temporary program in the pandemic that offers income support, recently extended to four weeks, for COVID-19-related leave. But it doesn’t cover pay fully, and isn’t remitted immediately.

Critics also say too many workers fall through the cracks. The program applies to those who have missed at least 50% of their scheduled work week, so those who wake up feeling unwell for a day, for example, would not get a full, uninterrupted paycheck. “It disincentivizes people to follow public health advice,” says Carolina Jimenez, coordinator of the Decent Work and Health Network.

Ms. Carpinone had to pay an employee for a week while their COVID-19 results were pending. Yes, it was a hassle. “I can’t sugarcoat it and say that it doesn’t cost anything, but it’s something that you budget in. It’s like saying, how much does it cost to repair an oven before it starts a fire? You’re not going to wait until it blows up.”

Doing right by employees

Ontario Premier Doug Ford, whose Conservative government got rid of the province’s two required sick days in 2018 after taking office, said reinstating them would duplicate the federal support, calling it a “waste of taxpayers’ money.”

Dan Kelly, president of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, says activists for paid sick leave have been seizing on the pandemic as an opportunity to push for permanent, employer-paid leave. While he says shortcomings in the federal program should be fixed, he finds the current debate disingenuous. “They have made the public believe that there is no paid sick leave in Canada, and that employees are forced to go to work sick,” he says.

But data shows many indeed are. In Peel, the region outside Toronto and one of the worst-hit areas for COVID-19, the public health agency released a study showing that 25% of workers went to work with symptoms between August and January. Mayors in the area wrote a joint letter calling on the Ford government to adopt sick days. So did a group representing 34 public health units of Ontario.

Ms. Jimenez says people are shocked to learn that, as a part-time nurse in Toronto, she doesn’t have paid sick days. “People audibly gasp,” she says. She could scrape by if sick, but workers depending on each hour of their paychecks have to make impossible choices. Often it’s women and minorities forced to make those choices, she says. “The pandemic has made the inequalities that we’ve had for a long, long time even more glaring.”

Helmi Ansari, CEO of Grosche International in Cambridge, Ontario, says that his own thinking evolved as a business owner – and he has hope that the pandemic will shift other employers’ minds on fair work.

When Mr. Ansari started his corporate career, he dreamed of one day being the boss with the corner office. When he and his wife started Grosche in their laundry room in 2006, selling tea and coffee craft brewing products, he thought paying over minimum wage made him a “good guy.” Then he learned how much workers struggled at those salaries. He joined the movement for a living wage and today is fighting with the Better Way Alliance for paid sick leave.

He offers five days to his 15 employees, a potential cost of 2%-3% of payroll, he says, but many never take it. “There is this common narrative that we hear that is doom and gloom … but this is an investment that does pay back,” he says. “More and more I see people in political circles talking about the importance of this, recognizing that the way we’re trying to attack this pandemic and future pandemics is really broken with the absence of paid sick leave.”

“We’re telling workers to either put food on the table or you come to work sick. In Canada, one of the most developed countries in the world, it’s a shame that workers have to make that choice,” he says. “And our economy is actually suffering more because we don’t have sick days.”

Editor's note: The headline was updated to clarify the scope of the story.

To help Venezuela, Biden is urged to put people before politics

How do you weigh toppling a rotten regime versus easing suffering? In Venezuela, there’s a sense that the mounting humanitarian crisis is more urgent – and that might call for a new U.S. approach.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Confronting the political and humanitarian crises in Venezuela, the Trump administration opted for broad sanctions, which appeared aimed at toppling the authoritarian government of President Nicolás Maduro but only deepened most Venezuelans’ misery.

Now, as the Biden administration weighs its own policy options, a growing chorus of Venezuelans and regional experts are calling on the United States to redirect its focus.

Instead of pressing for a quick return to democratic rule, they say, first address a humanitarian crisis that has slashed life expectancy, stunted children’s growth, fed spiraling levels of violence, and prompted more than 5 million Venezuelans to flee their homeland.

Feliciano Reyna, who runs a public-health organization in Caracas, says the U.S. should employ the “multilateralism” that President Joe Biden has invoked and work with other countries and international organizations, as well as Venezuela’s civil-society actors at the forefront of efforts to rescue crumbling lives.

“It’s not directly getting back to a governance that works,” says Michael Camilleri, a Venezuela expert at the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington, “but it injects a little pragmatism and energy into a political environment that has been exhausted in the last six months. It offers something for the Biden administration to work with and build on.”

To help Venezuela, Biden is urged to put people before politics

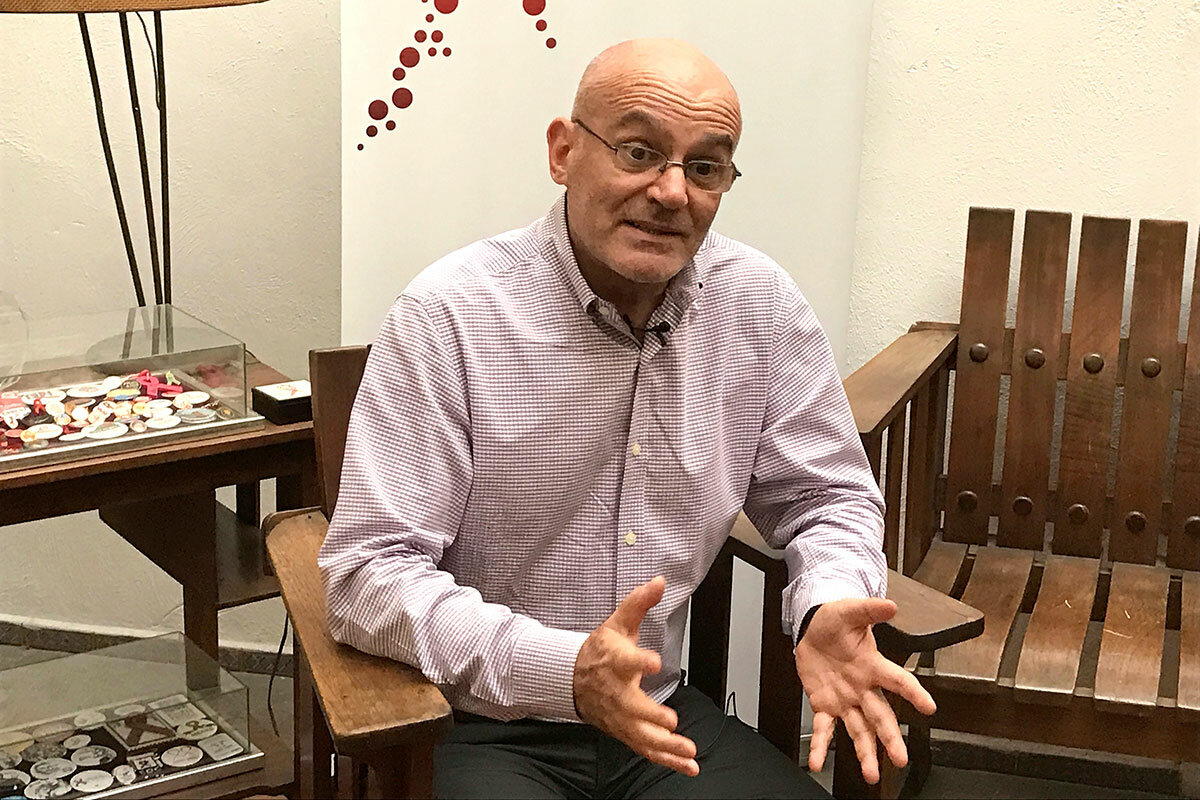

As the Biden administration considers how best to address the political and humanitarian crises in Venezuela – once Latin America’s wealthiest country, but now a shambles enduring the region’s worst human suffering – Feliciano Reyna has a few suggestions.

The prominent Venezuelan HIV/AIDS activist says the United States should shift away from the Trump administration’s broad sanctions, which appeared aimed at toppling the authoritarian government of President Nicolás Maduro but only deepened most Venezuelans’ misery.

Instead Mr. Reyna, who runs a nongovernmental public health organization in Caracas, recommends a “change of thinking” that puts off solving the political conflict to the medium to long term while concentrating immediate attention on addressing the humanitarian crisis wracking the country’s 30 million people.

To do that more effectively, he says, the new administration in Washington should employ the “multilateralism” that Joe Biden made a watchword of his quest for the White House.

And by that, Mr. Reyna says, he means both in terms of working with other countries and international organizations, as well as with a wider range of Venezuela’s civil-society actors at the forefront of efforts to rescue crumbling lives.

“I sincerely hope there is a revision by the Biden administration of how to think about contributing effectively to resolving [Venezuela’s] crisis,” he says.

“What is important now is to bring into the conversation our civil society,” he adds, “in all its diversity but also its unity behind improving and saving lives.”

Mr. Reyna is part of a growing chorus of Venezuelan voices and regional experts calling on the United States to redirect its focus from pressing for a quick return to democratic rule to addressing a humanitarian crisis that has slashed average life expectancy, stunted children’s growth, fed spiraling levels of violence, and prompted more than 5 million Venezuelans to flee their homeland.

Intimidation campaign

Since Mr. Maduro took office in 2013, the once high-flying oil-based economy has shrunk by two-thirds while the political opposition has been further marginalized.

And the Maduro government’s intimidation campaign against human rights activists, journalists, and even food and health providers who dare offer an alternative to meager government programs is “continuous and increasing,” according to a report last week by United Nations human rights experts.

An element of the emerging perspective is that while the political opposition the U.S. has traditionally worked with is weakened and deeply divided, Venezuela’s civil society – a panoply of nongovernmental organizations, unions, and business groups – is if anything stronger, more diverse, and more effective in addressing people’s needs than at the outset of the country’s downward spiral.

The thinking is not so much to abandon Venezuela’s political players as it is to work more closely with the groups that are most effective now at improving and indeed saving lives. The objective is a strengthened society that has the energy and awareness to join in delivering political change in the future.

“With the formal political space so stuck, it’s increasingly the various actors of civil society who are coming together to address people’s real problems and to consider the big questions like ‘How do we move forward from here?’” says Michael Camilleri, director of the rule of law program and a Venezuela expert at the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington.

“It’s not directly getting back to a governance that works,” he adds, “but it injects a little pragmatism and energy into a political environment that has been exhausted in the last six months. It offers something for the Biden administration to work with and build on.”

Sticking with Guaidó

In its first month the Biden administration has given few hints as to its approach to the Western hemisphere’s most acute and vexing crisis.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken has thrown cold water on speculation that the new administration could move to quickly enter talks with the Maduro government. At his Senate confirmation hearing in January, Mr. Blinken said the Biden administration would continue to recognize opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the country’s legitimate interim president.

But he also said the administration would review the myriad sanctions the Trump administration imposed on Venezuela and consider boosting humanitarian aid.

And when White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said at one of her first daily briefings last month that the new administration “will focus on addressing the humanitarian situation … and reinvigorating multilateral diplomacy to press for a democratic outcome,” it buoyed those Venezuelans who had concluded that former President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” approach only hardened Mr. Maduro’s repressive actions and worsened average Venezuelans’ lives.

Still, one problem for the Biden administration is that the youthful Mr. Guaidó is now just a shadow of the charismatic leader who two years ago captured the heart of a nation devastated after 20 years of the populist socialism introduced by Mr. Maduro’s late predecessor, Hugo Chávez.

After appearing in early 2019 to be on the verge of wresting power from Mr. Maduro, and then winning the support of more than 50 countries including the U.S. as Venezuela’s legitimate leader, Mr. Guaidó has seen his national and international support dwindle as Mr. Maduro has consolidated power.

Focus on empowerment

For some Venezuelan activists, the important question for the U.S. is not whether it sticks with Mr. Guaidó or abandons him, as some European and Latin American countries have, but how it can take a more holistic approach to addressing the country’s crisis.

“What people are talking about now is the idea of the ‘nexus,’ how international assistance can help to link humanitarian to development to peace-making efforts,” says Roberto Patiño, whose network of 240 soup kitchens in 15 Venezuelan states feeds thousands of children while building community skills.

“The U.S. should think more about how to support civil society in empowering the Venezuelan people and make that a strategic pillar of a new approach,” he adds. “That would be a key difference from the Trump administration.”

One example of how that might work: The Biden administration should lift the Trump sanctions on Venezuelan crude oil sales, many experts say, and instead allow for “swaps” of oil sales for imports of diesel – an essential fuel in Venezuela for public transport and food production. That could correct how sanctions designed to punish the government instead deepened average Venezuelans’ hardships.

Mr. Patiño knows that speaking of “empowering” people risks placing him in the government’s crosshairs. Already in November his Feed the Solidarity charity was raided and an arrest warrant for “political subversion” forced him into hiding for weeks.

Mr. Reyna, the HIV/AIDS activist, also had his Solidarity Action group raided last year and several workers detained. More recently, the public health organization Azul Positivo was a police target.

What earns these civil-society organizations the wrath of the government, they argue, is their model of empowerment that aims to build community skills, responsibility, and independence. “From my perspective that frightens the government,” Mr. Patiño says, “because the regime is all about social control and keeping people dependent on them.”

But this goal of empowering people is exactly why the Biden administration should shift policy to deepen its work with civil society, he says – because that would align the U.S. more closely with shared values of human rights, personal development, and democratic governance.

“What we in Venezuela and others outside wanting to help have to understand is that any resolution to this crisis must include agreement that all the factions inside the country have a future here,” Mr. Patiño says. “Any solution for Venezuela has to put both the problems and the dreams of the Venezuelan people at the heart of the discussion,” he adds, “and that means including all political factions and perspectives.”

Patterns

Biden to allies: Enduring values stand up in a changed world

Joe Biden is setting up his presidency as a test of one of his core ideals: that democracy is strong enough to weather the challenges of the 21st century.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

President Joe Biden has long supported a vision of the United States leading alliances of like-minded democracies. He made that clear in his first foreign policy address, delivered virtually last week at the Munich Security Conference. Even so, the meeting brought to the fore doubts over bedrock assumptions of numerous U.S. leaders: the robustness of their country’s alliances and leadership role, and the lure of democracy itself.

Despite support for his message that “America is back,” there was continued fallout from President Donald Trump’s downgrading of alliances, and doubt over the staying power of President Biden’s worldview.

Mr. Biden vowed “to earn back our position of trusted leadership.” But his most emotive words were reserved for a wider challenge: the struggle for the future of democratic governance against an argument that democracies can’t handle the economic, health, and security tasks of the 21st century. “I believe with every ounce of my being that democracy will and must prevail,” Mr. Biden said.

Of all the long-held values he referenced, none better defines his presidency’s worldview. His task will be to bring allies along with him.

Biden to allies: Enduring values stand up in a changed world

“You know me.” It’s been a refrain all across Joe Biden’s half-century in public life. And the consistency of his core policy beliefs was on full show last week, in his first foreign policy address from the Oval Office.

His remarks were delivered remotely to an annual European security meeting he’s long attended in person. And they highlighted a new challenge: applying his enduring values and priorities to a world changed beyond recognition since his last time in national office, as Barack Obama’s vice president.

Some of the changes have been building for years, above all the increasingly assertive and emboldened stance of China and Russia. Yet others are newer, and could prove even more daunting: the geopolitical after-effects of former President Donald Trump’s reshaping of America’s approach to the world.

Mr. Biden’s abiding vision has been of an America leading alliances of like-minded democracies, standing strong against rivals where necessary, yet cooperating with them where possible. Those alliances, in his view, ultimately win the hearts and minds of the wider world “not by the example of their power, but the power of their example.”

All of that, he made clear to the delegates, was what he still believed in.

But beyond the challenge of China and Russia, this year’s Munich Security Conference brought to the fore doubts over bedrock assumptions of a long line of U.S. leaders: the robustness of America’s alliances; the impact of its leadership role; and, for the rest of the world, the lure of democracy itself.

China and Russia, to be sure, pose tests for the new president.

A different world

When Mr. Biden spoke in Munich a dozen years ago, soon after he and President Obama had taken office, his focus was mostly on broad international challenges that read like today’s headlines: world economic crisis; climate change; cybersecurity; Iran’s nuclear program. Even the shared challenge of fighting “endemic disease.”

But back then, he made only a glancing, largely conciliatory, reference to Russia. He didn’t mention China at all.

Appearing in Munich four years later, at the start of the Obama administration’s second term, he did cite differences with Russia. Yet he remained largely upbeat about cooperation. He spoke about China, too. But again – citing talks with the man who would become China’s leader, Xi Jinping – he voiced optimism that “healthy competition from a growing, emerging China” would prove positive, and that the U.S. and China weren’t destined to be “enemies.”

Unsurprisingly, his tone toward both rivals at last week’s conference was far tougher. He still stressed the importance of seeking cooperation, citing a range of issues where he felt it was simply essential: the COVID-19 pandemic, arms control, climate change.

But referring to Russia’s leader only by his last name, he accused Putin of seeking to weaken democratic alliances, “bully” other states, and hack into vital European and U.S. computer networks.

On China, he said it was essential to “push back” against its “economic abuses and coercion,” and shape new rules for future technology to ensure it is used to “lift people up” rather than “pin them down.”

Yet that brought Mr. Biden back to his yearslong belief in the core importance of America’s democratic alliances. Now more than ever, he said, the U.S. needed to “work in lockstep” with them.

It was on that issue that Munich highlighted what may prove his trickiest diplomatic challenge.

A different United States

Despite the welcome for his overall message that “America is back,” there were signs of continuing tremors from Mr. Trump’s downgrading of alliances in favor of bilateral “America first” dealings with individual world leaders.

In their remarks to the conference, two of Europe’s most influential leaders signaled that truly rebuilding the trans-Atlantic partnership – certainly “in lockstep” – might not prove easy.

During the Trump years, both German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron publicly questioned whether Europe could still rely on America’s bedrock support. At the Munich conference, Mr. Macron did say he believed in NATO – the military alliance between the U.S. and Europe that, under President Trump, he’d pronounced no longer viable. But he reiterated a call for Europe to seek “strategic autonomy” from Washington. And Chancellor Merkel – whose country has important economic ties with both China and Russia – paired her endorsement of Mr. Biden’s emphasis on the alliance’s “shared values” with a practical caveat: “Our interests will not always converge.”

And there is a deeper source of European skepticism: over the staying power of Mr. Biden’s worldview, and whether a Trump-style nationalism might yet return in the future.

Mr. Biden was clearly aware of all this, speaking of the need “to earn back our position of trusted leadership.”

But his most emotive words were reserved for a far wider, longer-term challenge: the struggle for the very future of democratic governance against an argument being made by China, Russia, and a number of other countries that democracies simply aren’t up to the task of handling the economic, health, and security tasks of the 21st-century world. That “autocracy is the best way forward,” as Mr. Biden summed up their view.

That is wrong, Mr. Biden asserted. “I believe with every ounce of my being that democracy will and must prevail,” he told the conference.

Of all the long-held values he brought to his address, none better defines the worldview with which he has invested his presidency. Yet now his task, and clearly his hope, will be to bring America’s overseas allies along with him.

Eye in the sky: Did Baltimore’s aerial surveillance program go too far?

Baltimore used drones to track people’s movements earlier this year. The controversial program is in court and could help set the line between privacy and public safety.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

What are the limits to police surveillance of those suspected of no crime? A federal appeals court is set to weigh in on that question next month as it considers the constitutionality of an aerial surveillance pilot program conducted last year over Baltimore.

From May through October last year, the Aerial Investigation Research program deployed an airplane equipped with high-resolution, wide-angle cameras to capture footage of 32 square miles of the city. Software pairs this footage with data from ground-based security cameras, license-plate readers, and gunfire detectors to monitor people’s movements.

A preliminary report by the Rand Corp. found little evidence that the program was better at solving crimes than traditional policing methods, but proponents say it discourages crimes. “Our job is to deter people,” says Ross McNutt, founder and president of the Ohio-based Persistent Surveillance Systems, which operated the surveillance planes.

To opponents, the surveillance goes too far. Ashley Gorski, a senior staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, who has argued for the plaintiffs, says the program violated “a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

“If the courts allow this surveillance to go forward,” she says, “it will radically alter the relationship between the individual and the state.”

Eye in the sky: Did Baltimore’s aerial surveillance program go too far?

Can police legally surveil a huge swath of a city from the air, using software to track people’s movements?

This question is what The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit is set to consider next month, as it examines the constitutionality of the Aerial Investigation Research (AIR) program, a first-of-its-kind, police-sponsored surveillance program tested last year in Baltimore.

At issue is whether planes equipped with high-resolution cameras that flew over the city from May through October violated residents’ Fourth Amendment rights. Complicating matters is an antebellum law that limits the Baltimore City Council’s authority over its police.

Ashley Gorski, a senior staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, who has argued for the plaintiffs, says the program violated “a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

But the District Court and the majority on a three-member panel of judges on the Fourth Circuit have disagreed, first denying the preliminary injunction and permitting the pilot program to operate before the panel’s November decision affirmed the lower court’s ruling. “The program has been carefully designed to impose a minimal burden on constitutional rights,” the majority wrote.

Though the program ended last October, and the city’s new mayor pledged the planes would not fly again, the reconsideration in March by the full, 15-member Fourth Circuit could determine whether the technology is permitted other places in the future, and, if allowed, under what conditions. Regardless of the court’s ruling, the larger question also remains: Did the program actually help to make Baltimore safer?

“If the courts allow this surveillance to go forward,” says Ms. Gorski, “it will radically alter the relationship between the individual and the state.”

Pixels and privacy

When demonstrations occurred last summer, the surveillance planes flew overhead in Baltimore, watching people, protests, and police from above. The planes captured footage of 32 square miles, with individuals represented as a single pixel. The ACLU’s Ms. Gorski says the technology is “capable of subjecting every square inch of the city to constant recording.”

But under the program detectives could request the aerial surveillance footage only after a crime had been committed. No distinguishing characteristics, like a person’s race or gender, can be identified from the footage, said Michael Harrison, the city’s police commissioner, last year. The moving dots are tracked to and from a crime scene and the footage is used in conjunction with other ground-based security cameras, license-plate readers, and gunfire locators as a tool to help solve crimes.

“Our job is to deter people,” says Ross McNutt, founder and president of the Ohio-based Persistent Surveillance Systems, which operated the surveillance planes and produced evidence packets for the Baltimore Police Department (BPD).

It’s not yet clear whether the program is more effective at solving crimes than policing methods that were already in place. The Baltimore police reported 390 armed robberies from May 1 to July 31 last year. According to the same report, confirmed by the Rand Corp., a nonpartisan research institution hired to evaluate the program, fewer than a fourth of those robberies were committed during the day, when the planes were operating. An even smaller number were actually recorded by the aerial cameras.

A Rand report published in January provided “no conclusions on the effectiveness of the AIR program,” but offered preliminary information showing slight increases in clearance rates for cases using AIR evidence. Rand is set to release its final report on the program in spring 2022.

Mr. McNutt’s company has a three-year contract pending in St. Louis that would allow the plane to fly day and night, but the contract has not yet been signed by the mayor. The organization, Arnold Ventures, headquartered in Houston, which financed the Baltimore operation and three program evaluations at a cost of roughly $3.7 million, said it will not fund the St. Louis program.

Who decides?

Complicating the issue is an 1860 law that places the Baltimore Police Department under the authority of the state legislature, even though the city’s tax revenue pays almost all the department’s expenses. Under this arrangement, the City Council lacked the opportunity to vote on whether to approve last year’s program, nor can it regulate its conditions.

“Democratic control, accountability, protection of civil rights and civil liberties ... all of those are important components of public safety,” says Farhang Heydari, the executive director of the Policing Project at New York University School of Law, which audited the program and filed a brief supporting neither party, but encouraging the Fourth Circuit to rehear the case.

During the pilot program, accountability and local democratic control were lacking, says Lawrence Grandpre, the director of research for Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, a grassroots Baltimore think tank, represented by the ACLU in the case.

Mr. Grandpre’s organization has been advocating returning control of the police department from the state legislature to the City Council since before Freddie Gray died while in police custody in 2015.

“The hope is that by returning legal authority to the city you can have a more democratically accountable relationship to the Police Department,” Mr. Grandpre says. “This returning of the BPD to the hands of the City Council, to the hands of the Baltimore City, would just be one further step toward creating what we hope is more grassroots, broad-based accountability in Baltimore.”

Brandon Scott, Baltimore’s mayor and previously the City Council president, sees the move as “essential” for the department and will be advocating for local control during the state’s legislative session, spokesperson Stefanie Mavronis said in an email.

With the court case scheduled to be reheard the second week of March, Mr. Grandpre says, “the legal victory that we hope to get is one piece,” but adds that another goal is reframing conversations around public safety.

“What we need to do is fundamentally rethink the reality of why people see violence as necessary,” he says, “and build an infrastructure that addresses those needs.”

Points of Progress

In a first for Ecuador, victims of modern-day slavery find justice

This week’s roundup from around the world includes several shattered glass ceilings, from the U.S. Cabinet to the Muslim Council of Britain to the World Trade Organization.

In a first for Ecuador, victims of modern-day slavery find justice

1. United States

The U.S. Senate confirmed the first openly gay Cabinet secretary. Former mayor and presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg is officially leading the Transportation Department following an 86-13 vote. He is tasked with managing the country’s aviation, highways, pipelines, and railroads. Mr. Buttigieg will play a key role in allocating government assistance to struggling transit systems and overseeing new technologies such as self-driving cars.

As acting director of National Intelligence for three months last year, Richard Grenell was the first openly gay Cabinet member. “Pete shattered a centuries-old political barrier with overwhelming bipartisan support and that paves the way for more LGBTQ Americans to pursue high-profile appointments,” said Annise Parker, head of the LGBTQ Victory Institute and a former Houston mayor. (Reuters)

2. Ecuador

A local judge has ruled that Furukawa Plantaciones C.A. violated the rights of 123 ex-laborers who went before the court in January, marking the first time the government has recognized modern-day slavery in agriculture. In an oral ruling, the judge declared the workers had suffered racial discrimination and were victims of servitude – a form of modern-day slavery – at the Japanese-owned abacá tree plantation. Ecuador is one of the world’s top exporters of abacá fiber, a durable material used in rope, currency, and other products, but the workers who harvest it have little to show for their work in the $17 million industry. For years, inspections of the plantation have noted child labor, work accidents, low wages, and poor living conditions. Many are hailing the decision as a legal milestone for the hundreds of Afro-Ecuadorian families who have lived in slavelike conditions since Furukawa was established in 1963. The decision is not definitive, as the case will likely move up to higher courts, but the plaintiffs’ lawyers say the historic ruling opens the way to compensation. (Thomson Reuters Foundation)

3. United Kingdom

The Muslim Council of Britain – the largest umbrella body serving the United Kingdom’s Muslim population – has elected its first female leader. Zara Mohammed has taken the reins as the organization’s secretary-general for a two-year term. More than 3.3 million Muslims live in the U.K., and the council’s member organizations include more than 500 mosques, charities, schools, and professional networks. Ms. Mohammed, who holds a master’s degree in human rights law and hails from Glasgow, Scotland, is also the youngest person to ever lead the organization. “My vision is to continue to build a truly inclusive, diverse, and representative body; one which is driven by the needs of British Muslims for the common good,” she said after the vote, adding that she hopes her victory helps “inspire more women and young people to come forward to take on leadership roles.” (Al Jazeera, Muslim Council of Britain)

4. South Africa

South Africa saw a 33% drop in rhino poaching in 2020 compared with the previous year, marking the sixth year that poaching has declined. Last year, 394 rhinos were reportedly killed for their horn in South Africa, down from 594 in 2019. “While the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the battle to beat the COVID-19 pandemic contributed in part to the decrease in rhino poaching in 2020, the role of rangers and security personnel who remained at their posts, and the additional steps taken by government to effectively deal with these and related offenses, also played a significant role,” said Barbara Creecy, the country’s environment, forestry and fisheries minister.

A total of 156 people were arrested for rhino poaching or horn trafficking across the country, and authorities engaged in more than 25 major investigations. The continued improvement comes after the government implemented new wildlife protection strategies, including public awareness campaigns and regional information sharing. Experts say remaining vigilant as lockdowns ease will be critical to maintaining the downward trend. (Political Analysis South Africa, South Africa News Agency)

5. New Zealand

New Zealand has made Matariki, the Māori new year celebration, the first public holiday that honors Māori culture. Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster, which rises in the Southern Hemisphere around midwinter. This historically marks the start of the new year for mainland New Zealand’s Indigenous people. Local councils have been organizing Matariki celebrations and raising awareness about the tradition since the early 2000s, but past efforts to recognize the constellation’s reappearance as an official holiday have failed. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the first official Matariki will be celebrated June 24, 2022, and future dates will be determined by the newly formed Matariki advisory group in compliance with the Māori lunar calendar. It will also advise on how to celebrate the event, considering regional differences in tribes’ traditions, and develop resources to educate the public about Matariki’s meaning, said chair Rangiānehu Matamua, a professor who specializes in Māori astronomy. (The Guardian, Stuff)

World

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is set to become the first African and the first woman to hold the top position at the World Trade Organization (WTO), and many see her appointment as a historic validation of African women’s competency and leadership. The Nigerian economist has a reputation as a strong international negotiator with a commitment to reducing poverty and improving transparency. She became an American citizen in 2019.

Selecting a new director-general requires approval by all WTO members, and Dr. Okonjo-Iweala’s path was cleared after President Joe Biden reversed the previous administration’s objection to her candidacy. Dr. Okonjo-Iweala is taking over the WTO during turbulent times marked by member infighting and the ongoing coronavirus crisis. (Deutsche Welle, CNN, Al Jazeera)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why China’s homeowners prefer universal rights

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Only in the past three decades has China’s ruling Communist Party allowed people to own a residence. Now about 96% of city dwellers own a home, usually in high-rises. Despite this leniency, the party ensures the state still owns the land under housing structures. Private ownership, contends party leader Xi Jinping, is a “Western” system. He dismisses the notion of “universal values,” such as a right to own a home and the land it sits on.

Yet millions of Chinese living in private residences seem to disagree. Since the 1990s, many have formed homeowner associations to demand a say in the management of their properties. To them, individual ownership requires individual freedom and other rights that are universal in nature.

While values like those embedded in a democracy may have roots in the West, they have been adapted widely over centuries. They are now bubbling up even in Beijing homes. All by themselves, homeowners in China are defining their shared social interests, organizing neighbors to insist on accountability and transparency in services for their properties. This awakening in thought about individual rights and liberties is as natural – and universal – as can be.

Why China’s homeowners prefer universal rights

Only in the past three decades has China’s ruling Communist Party allowed people to own a residence. Now about 96% of city dwellers own a home, usually in high-rises. Despite this leniency, the party ensures the state still owns the land under housing structures. Private ownership, contends party leader Xi Jinping, is a “Western” system. He dismisses the notion of “universal values,” such as a right to own a home and the land it sits on. Only the party, he says, can define China’s particular “core values.”

Yet millions of Chinese living in private residences seem to disagree. Since the 1990s, many have formed homeowner associations (HOAs) to demand a say in the management of their properties. To them, individual ownership requires individual freedom and other rights that are universal in nature. In Beijing, officials are one step ahead of this movement. They have started to introduce HOAs in city neighborhoods, according to the Financial Times. They understand that proper governance of local residences builds trust.

But there’s been a hitch. Who chooses the candidates to run in elections for leaders of the HOAs? Many urban homeowners demand a full say in selecting candidates rather than the party imposing its preferred candidates. They want the local bodies to be self-governing and responsive to issues such as trash collection and utility fees. In a taste of democracy, residents are fighting for free and fair elections.

Yet the party is pushing back. “If you allow people to vote for HOA president out of their own will, they may one day expect to do the same for national leaders,” says a community governance scholar in Beijing, according to the Financial Times.

Many world leaders have challenged Mr. Xi in his dismissal of universal values. In a phone call with him on Feb. 10, President Joe Biden shared his “concerns” about China’s leaders trammeling on rule of law in Hong Kong, threatening Taiwan’s democracy, and abusing the freedoms of minority Muslims in western Xinjiang province. Yet the real challenge for China’s rulers is more local, as witnessed in HOA elections as well as in cases of Chinese workers demanding unions and farmers seeking to elect village leaders.

In speeches, Mr. Xi criticizes the idea that values such as equality before the law are universal to humanity. Yet while values like those embedded in a democracy may have roots in the West, they have been adapted widely over centuries. They are now bubbling up even in Beijing homes. All by themselves, homeowners in China are defining their shared social interests, organizing neighbors to insist on accountability and transparency in services for their properties. This awakening in thought about individual rights and liberties is as natural – and universal – as can be.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The ‘perfect’ that heals

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Dilshad Khambatta Eames

Our lives can seem far from perfect sometimes. But a spiritual understanding of ourselves and others opens the door to healing and peace – as a woman found when she began studying Christian Science.

The ‘perfect’ that heals

When I first walked into a Church of Christ, Scientist, I sensed an atmosphere of joyful dignity and togetherness. Since then, I’ve come to realize that this comes from something deeper than a group of happy people coming together, as lovely as that can be. It comes from a quiet acknowledgment of the “man” of God’s creating, a foundational concept in Christian Science.

Here I use the word “man” as the Bible sometimes uses it, which includes all of us. The Bible verse that best describes what I felt is this: “Mark the perfect man, and behold the upright: for the end of that man is peace” (Psalms 37:37).

Something I learned that’s key to “marking,” or recognizing and honoring, the “perfect man” is seeing things through a spiritual lens. That is, looking at others from the standpoint of what we all are as the sons and daughters of divine Spirit, God. This is at first a choice we may consciously need to make, but then we find that it becomes quite natural. That’s because as God’s children, we all innately have spiritual sense. Willingness to accept this fact and look to spiritual sense in the way we view the world helps us move forward and progress in every realm of life.

What is spiritual sense? Mary Baker Eddy, who founded The Christian Science Monitor, explains, “Spiritual sense is a conscious, constant capacity to understand God” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 209). Those two words “conscious” and “constant” point to mental activity – a firm, steadfast faithfulness and a diligent, awakened perseverance, which enable us to know God as infinite good, Life, and Love.

Our capacity to understand divine Life, God, stems from the fact that God, good, is infinite and omnipotent, the only legitimate cause there is. God’s creation is spiritual, the expression and manifestation of the divine Spirit.

Each of us in our true nature, therefore, is not a personal creator but the creation, or effect, of the one infinite God. We cannot be separated from the Life that expresses, renews, and regenerates us.

Attending a Christian Science church has helped me see this more and more. It’s become more natural for me to know myself in this spiritual light and honor others just as Christ Jesus did – to see and to love the “perfect man.”

This doesn’t mean ignoring problems or saying that things are physically perfect. Certainly, there have been times when I’ve been confronted with illness and other difficulties. But the idea that God, infinite good, is the only legitimate cause and created each of us as spiritual and pure, kept me faithful in persevering – in actively turning to spiritual sense to inform my perspective on things. And with the clearer glimpses of spiritual reality this brought, healing and solutions came.

For instance, I’ve become much less fearful in general. And symptoms of asthma simply faded away, and haven’t returned. I’ve had other physical healings too, some that required more diligent prayer and study of the weekly Christian Science Bible Lesson. What I learned through this prayer and study helped me better know myself – my true, spiritual self. This brought with it a new sense of life, trust, and love for humanity that made me a better person in every way.

Jesus gave us the Lord’s Prayer, which begins and ends with God, acknowledging the power and presence of the Divine. In the middle is a request for “daily bread,” or a heart filled with grace, forgiveness, and love. As we more consistently let God’s standard of the “perfect man” inspire how we think and act, this heals and regenerates the heart, mind, and body.

We are all able to “mark” – to acknowledge, honor, uphold, and love – God’s “perfect man.” What could be more important than that today? Beholding the true, spiritual nature of ourselves and others opens doors to more lasting reconciliation, health, equality, and peace.

A message of love

Perseverance pays off

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Harry Bruinius looks at the controversies surrounding New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the changing landscape around old-school politics of intimidation and humiliation.