- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why thieves only want part of your car – and what that says about value

Here’s a head-scratcher: Thieves don’t want to steal your car. They just want to saw off your tailpipe and grab the catalytic converter.

The phenomenon is common in Britain, and thousands of reports of catalytic converter heists are popping up in the United States, The Washington Post reports. The reason? Rhodium, a silver-white metal that serves as a cautionary tale about how economics and technology can make commodity prices suddenly soar – and plunge.

Rhodium, it turns out, is highly effective at filtering out a nasty pollutant from car emissions. And it’s in short supply.

In the past three years, prices have skyrocketed from $1,700 to $27,000 an ounce, more than 15 times pricier than gold. And we won’t see a surge in supply anytime soon because rhodium is a byproduct of platinum production, and there’s such a glut of platinum that even high rhodium prices won’t kick-start new production.

But don’t push the rhodium panic button just yet. A decade ago, Western nations fretted about China’s limited bans on exports of rare earth minerals. The doomsayers turned out to be wrong, in part because companies found substitutes. So this time car companies may find a way to retool catalytic converters – or they’ll just start selling more electric vehicles.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Cuomo, Democrats, and the politics of personal conduct

Where is the right place to draw the line when it comes to personal behavior for public officials? Allegations against Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a prominent Democrat, have renewed soul-searching within his party.

The politics of personal conduct has burst forth again. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo is facing calls for resignation over alleged sexual harassment of women. The scandal has been compounded by another embroiling Governor Cuomo – allegations that his administration purposely withheld data on COVID-19 deaths in New York nursing homes.

Yet some three years after the #MeToo movement swept the nation, bringing new scrutiny and standards to workplace behavior and power imbalances, the reports of Mr. Cuomo’s sexually charged language with young women are raising knotty political and ethical questions for Democrats. Some see a moral imperative to draw a bright line on such matters, remembering the damage of the Clinton era. Others are wondering if the party has been, at times, too quick to react – such as in the case of former Minnesota Sen. Al Franken. Indeed, after watching Republicans largely disregard sexual assault allegations against President Donald Trump for four years, some are asking: Why should Democrats be so much harder on their own?

GOP pollster Whit Ayres doesn’t see the Biden message on respect as necessarily having a partisan bent. “It’s clear that President Biden ran the campaign with an underlying theme that character is as important as policy,” Mr. Ayres says. “That is not a Republican or a Democratic message. It’s a message that has particular resonance throughout the ages.”

Cuomo, Democrats, and the politics of personal conduct

On Day One as president, Joe Biden laid down a marker for anyone working in his White House: Treat one another with respect, or “I will fire you on the spot.”

“We have to restore the soul of this country,” he added, a not-so-subtle dig at his predecessor.

Indeed, less than a month later, a senior member of the Biden press team was asked to resign over his use of sexually crude, threatening language toward a female reporter. But in a larger sense, the president’s plea for civility and decency also seemed aimed at the nation – including the Democratic Party he leads.

Now, the politics of personal conduct has burst forth yet again. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a prominent Democrat, is facing calls for resignation over alleged sexual harassment of women, two of whom worked for him at the time. The scandal has been compounded by another embroiling Governor Cuomo – allegations that his administration purposely withheld data on COVID-19 deaths in New York nursing homes.

Yet some three years after the #MeToo movement swept the nation, bringing new scrutiny and standards to workplace behavior and power imbalances, the reports of Mr. Cuomo’s sexually charged language with young women are raising knotty political and ethical questions for Democrats. Some see a moral imperative to draw a bright line on such matters, remembering the damage of the Clinton era. Others are wondering if the party has been, at times, too quick to react – such as in the case of former Minnesota Sen. Al Franken. Indeed, after watching Republicans largely disregard sexual assault allegations against President Donald Trump for four years, some are asking: Why should Democrats be so much harder on their own?

“We have no other choice if we’re going to stay true to our principles,” says Democratic strategist Jim Manley. “I’d rather see us leave the hypocrisy to the Republicans. I have no problem with Joe Biden setting a high standard.”

GOP pollster Whit Ayres doesn’t see the Biden message on respect as necessarily having a partisan bent. “It’s clear that President Biden ran the campaign with an underlying theme that character is as important as policy,” Mr. Ayres says. “That is not a Republican or a Democratic message. It’s a message that has particular resonance throughout the ages.”

Republicans disagree that they look the other way at bad behavior in their ranks. Plenty of party members paused over Donald Trump’s numerous alleged sexual misdeeds that came to light during his first campaign. But once he was elected president, the party effectively decided to live with his past. And while President Trump wasn’t accused of sexual misconduct while in office, as Mr. Cuomo has been, the former president’s mercurial style led to many high-level departures during his time in the White House; some former officials don’t hide their disdain for the ex-president, though he remains popular with the party’s base.

Bad optics for the GOP have continued, with two freshman congressmen facing harsh allegations this week about past behavior. In a Pentagon report, Rep. Ronny Jackson of Texas was accused of sexual harassment and drinking alcohol on the job while serving as White House physician. Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina also faces renewed allegations of past sexual misconduct. Both men have denied the charges, and it remains to be seen how their party caucus will handle the reports.

Of course, Democrats have their own history of looking the other way at prominent members who engage in sexual misconduct, including former President Bill Clinton. Some feminists played down reports of Mr. Clinton’s misbehavior when he was running for president – and stuck by him even after his impeachment for lying under oath about sexual misdeeds, arguing that his policies were good for women.

Today, Mr. Biden’s own stance on bad past behavior – if not sexual impropriety, at least the incivility he decried on Inauguration Day – hasn’t come without inconsistencies. He nominated Neera Tanden, a veteran of the Clinton and Obama administrations, to be his budget director, despite a history of “mean tweets” against prominent senators of both parties.

Her prospects collapsed last week after Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia announced he could not support her after concluding that her past statements would have a “toxic and detrimental impact” on her ability to work collaboratively with members of Congress. Still, when Ms. Tanden withdrew from consideration Tuesday, Mr. Biden said he looked forward to having her serve his administration in a position that doesn’t require confirmation.

Some political observers suggest that it is Ms. Tanden’s fighting spirit that led Mr. Biden to want her on his team in the first place. And adhering to standards of civility, they add, doesn’t mean his people will be patsies when confronting opposition to the Biden agenda.

But Ms. Tanden’s tweets were one thing. More problematic, legal experts say, is the episode of her pushing a journalist, which she acknowledges. Mr. Cuomo’s alleged pattern of conduct with now-former aides also suggests potential violations of law.

“There is a line,” says Margaret Johnson, co-director of the Center on Applied Feminism at the University of Baltimore. “The law says you can’t, in an employment setting or other settings, treat someone with unwelcome sexual advances or comments that are severe or pervasive, that affect the terms and conditions of their employment.”

New York Attorney General Letitia James has now launched an independent investigation into the charges against Mr. Cuomo. Numerous Democratic officials have called on him to resign, both over the alleged sexual harassment and the nursing home imbroglio, but at his press conference Wednesday, Mr. Cuomo seemed to buy time. He apologized for his behavior toward his three female accusers, and insisted he meant no harm, though he still seemed to put the onus on the women’s perceptions of his behavior and not on the behavior itself.

“If they were offended by it, then it was wrong,” Mr. Cuomo said. “If they were offended by it, I apologize.”

Commentators suggest that the #MeToo movement has moved into a new phase, in part because Mr. Trump – seen by some as the catalyst – is no longer in office.

“With Donald Trump out of the limelight, by definition, the entire movement stepped back a bit,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia.

“We’ve seen so many egregious examples of sexual harassment and sexual assault and just hostile working conditions for women that – and this is a terrible way to put it – the novelty has worn off,” Professor Lawless says. “In some ways, people have become almost inoculated against these kinds of charges.”

And, she adds, given the global pandemic and profound economic challenges some face, other issues fade in prominence.

Ms. Lawless points to the resignation of Senator Franken in January 2018, early in the #MeToo movement, as an example of how accused public figures were given much less opportunity to defend themselves than they are now. The sexual assault convictions of former Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein were one thing. The murkier charges leveled against Mr. Franken, beginning with the resurfacing of an old photo from his comedy days of him pretending to grope a female comedian, were something else.

Democratic Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, an advocate for women’s rights who led the charge against Mr. Franken, has been more cautious over her home state governor’s fate, and not called on him to resign.

“The importance of a full investigation has become really key,” says Ms. Lawless, noting that some investigations of accused men haven’t panned out. “Like with any movement, the pendulum swings back and forth until it hits the right point.”

The main thing, she says, is that women still need to feel they can come forward with accusations, and bring bad conduct to the forefront without being maligned in the process.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin, a founding editor of Ms. magazine, hails from the era of “second-wave feminism,” when women gained reproductive rights and other laws aimed at equality, but still struggled with the power dynamic in the workplace and in social settings.

Now, she looks at her 20-something granddaughters’ generation and sees that “it’s still hard to adjudicate a male superior who has power over you.”

“You’re trying to be taken seriously, but you still get reduced to how you look,” Ms. Pogrebin says.

As for Mr. Biden’s Day One edict, she says, “it’s a proclamation that norms are returning. Be prepared.”

Behind vaccine doubts in Africa, a deeper legacy of distrust

Vaccine hesitancy in Africa is often rooted in distrust, shaped by a long history of inequality. An effective pandemic response includes addressing those doubts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

For months, many African governments have struggled to secure vaccines in a system in which wealthy countries take the lion’s share, shining a spotlight on global inequalities. But as campaigns begin to roll out across the continent, a lingering issue of distrust is coming into sharp focus.

The reasons vary. In South Africa, distrust of the creaking, overburdened public health system and the government that manages it runs deep. So does skepticism that people’s lives here really matter to the foreign companies and countries behind most COVID-19 research – concerns rooted in a long history of inequality.

Some fears “have roots in colonialism, oppression, and exploitation that can easily be stirred up in situations like this, especially when you see the world’s vaccine inequity – where some countries have been able to buy up a disproportionate number of vaccines,” says Indira Govender, a doctor and health activist in South Africa.

Hesitancy could mean a longer road to herd immunity and slower economic recovery amid a second wave. But community health leaders say there is a window to help address concerns, offer information, and heal distrust.

“We have the tools. We just need to activate them,” says Tunji Funsho of Rotary International.

Behind vaccine doubts in Africa, a deeper legacy of distrust

Ahmad Mansur has made up his mind. Vaccines have not yet arrived in Nigeria, but Mr. Mansur has decided he won’t be getting one, nor will his three young children.

Word goes around in the northern Kano State that vaccines bring problems, and Mr. Mansur believes those rumors. “Instead of one to be cured of a disease, one will end up getting something else,” says the pedicab driver.

Nearly 4,000 miles south, pediatric nurse Rich Sicina is treating COVID-19 patients in a hospital near Johannesburg. He grew up in the shadow of one pandemic – HIV/AIDS – and is now fighting on the frontlines of another. But he, too, is suspicious. How can a vaccine developed in such a short time be safe or effective, he wonders – and how can South Africans be sure that Western pharmaceutical companies have their best interests at heart?

For months, many African governments have struggled to secure vaccines in a system where wealthy countries take the lion’s share, shining a spotlight on global inequalities. For most of the region, that challenge continues. But as campaigns finally begin to roll out across the continent, a lingering issue of distrust is coming into sharp focus.

The reasons vary. In South Africa, distrust of the creaking, overburdened public health system and the government that manages it runs deep. So does skepticism that people’s lives here really matter to the foreign companies and countries behind most COVID-19 research – concerns rooted in a long history of inequality. And the continent’s lower number of deaths, compared with many other regions, has given many Africans a false sense of immunity, doctors say.

As recently as December, around a quarter of Africans surveyed felt vaccines will not be safe, according to the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A recent Ipsos survey found that only 61% of South Africans would get a vaccine, lower than any of the other 14 countries surveyed, except for France and Russia.

Hesitancy could mean a longer road to herd immunity and slower economic recovery amid a second wave. But community health leaders say there is a window to help address concerns, offer information, and heal distrust. In particular, they argue, strong buy-in from local leaders is crucial to promoting acceptance.

Rumor has it

Across Africa, conspiracy theories about vaccines were popular even before COVID-19. Long-circulating gossip in parts of Nigeria, for example, claims that shots make people infertile, or that they contain surveillance chips. In Ghana, Ebola vaccine trials were halted in 2015 because of rumors that scientists planned to infect people with the disease.

With COVID-19, new conspiracy theories have reared their heads. At the beginning of the outbreak, many WhatsApp users forwarded with dizzying speed allegations that COVID-19 was manufactured in a Chinese lab, or that radiation from 5G internet towers caused the disease.

Some fears “have roots in colonialism, oppression, and exploitation that can easily be stirred up in situations like this, especially when you see the world’s vaccine inequity – where some countries have been able to buy up a disproportionate number of vaccines,” and others are left without, says Indira Govender, a doctor and health activist in South Africa. “That plays on people’s fears of Western colonialism and Western medicine.”

But rumors also have roots in recent trials that, on occasion, have seen African countries on the receiving end of unethical medical practices. In 2009, Pfizer reached an out-of-court settlement over a controversial meningitis drug trial in Kano State in the 1990s. Eleven children died, and others were paralyzed. The company argued the deaths were due to meningitis, not the drug, but parents alleged they had not given informed consent. In South Africa, many recall HIV vaccine trials in the mid-2000s that wrapped up hastily after authorities discovered that not only was the drug powerless against infection, it potentially made those who took it vulnerable.

On the back of the Pfizer episode, rumors prompted a politician-backed polio vaccine boycott in 2003 in parts of northern Nigeria, where low literacy levels and conservative Islamic principles often foster a doubtful eye toward Western interventions. The boycott was lifted more than a year later, but cases shot up, and the virus spread as far as Yemen.

Now with COVID-19, connectivity makes sharing misinformation happen much faster. Top politicians, including a sitting Nigerian governor and a top South African judge, have spread conspiracies, too. In east Africa, Tanzania’s president once declared COVID-19 a scam, and his government has refused vaccines.

Countering fear

Some concerns about vaccine safety stem from its quick development, spooked further by unverified claims of deaths following immunization in Europe.

But those worries can be countered with accurate, targeted information, experts say. For decades, groups like Rotary International worked to overcome polio vaccine rejection in Nigeria by working with local health workers and volunteers, known and trusted by their communities, who helped carry out the door-to-door immunization push across the country. The country was declared polio-free last year.

“We have the tools. We just need to activate them,” says Tunji Funsho, Rotary International’s polio program lead in Nigeria. “We need to learn to communicate with people in languages they understand,” and figure out where the communications gap is.

It’s the superstitions, long-believed, that could prove harder to fight.

In South Africa, “people are afraid because they need more information. They need help to understand the science – how vaccines work, how they’re tested,” says Narnia Bohler-Muller of South Africa’s Human Sciences Research Council. Professor Bohler-Muller co-wrote an earlier study on South Africans’ vaccine confidence, which found that the most common reasons for doubts were fear of side effects and concerns about effectiveness. “The good news is, that’s a fixable problem. If people have superstitions about a vaccine, it’s hard to counter. If they just need more information, that can be given.”

Targeting people with accurate information is especially important now, she says, after the South African government halted rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine, following findings that it offered low efficacy against mild and moderate cases caused by a new variant identified in the country.

“We find that information needs to come from trusted and local sources, like community leaders,” says Tian Johnson, who leads the African Alliance, a group that has done pro-vaccine advocacy in South Africa since the early 2000s. The organization has found that “scientists and researchers shouldn’t be responding to false claims, because for many people they’re seen as the problem,” says Mx. Johnson, who uses gender-neutral titles. Instead, people need to hear from leaders they respect.

Continent-wide, meanwhile, experts warn that information efforts have not been as robust as they need to be. Nigeria’s primary health care agency has launched social media campaigns, but public announcements aren’t yet flooding public radio and TV. In Ghana, where mass vaccinations launched this week, President Nana Akufo-Addo got the first shot to convince skeptics.

Activists argue that vaccine skepticism will decline as more Africans are vaccinated – seeing for themselves a safe and effective procedure that, when more broadly offered, could ease restrictions on movement and help reopen economies.

But many countries face uncertainty about when, and whether, they’ll receive a significant number of doses. Most of the region is depending partially on the World Health Organization-led COVAX program, which promises fair distribution for vulnerable countries. As wealthier countries buy up supplies, that arrangement is leaving others waiting for crumbs. Nigeria, with 200 million people, has had its deliveries shifted back several times and only received its first 3.94 million doses this week. Only a dozen African countries have launched vaccinations, with about 4.5 million doses dispersed. In contrast, more than 150 million vaccines have been administered in the United States, China, and the United Kingdom alone, with millions more doses secured.

“Our challenge right now is [knowing] if the vaccines are coming at a particular time, so we don’t go advocating and the vaccines don’t come,” says Dr. Funsho.

An Atlanta neighborhood tries to preserve ‘a sense of place’

Repeated failures in the U.S. to mitigate the downsides of gentrification may indicate that a different approach is needed – one that depends on a common understanding of what it means to be a neighborhood.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The telltale signs of gentrification aren’t hard to spot: real estate investors buying houses, rents soaring, housing prices skyrocketing, longtime residents getting displaced. And they’re all evident in the Grove Park neighborhood of Atlanta, making it part of a national pattern long mired in race, class, and not-in-my-backyard policies.

Debra Edelson, executive director of the Grove Park Foundation, describes the process as “white money pushing out Black people.”

Zoning, rent control, property-tax breaks, and taxpayer-funded affordable housing have long been used to manage growth and keep neighborhoods diverse. But new research shows the long-term failure of such tools to temper change.

Many wonder if, ultimately, the struggle comes down to how to define a neighborhood. Is it a loose assemblage of groups and alliances working to improve property values, or a distinct place with a history that prizes people over profit?

For Cynthia Poe, a Grove Park resident, the problem isn’t gentrification per se. After all, a new YMCA has opened, an old community theater is being renovated, and more services and stores are all coming.

The point, she says, isn’t to keep the neighborhood Black, but to keep it culturally vibrant – and to safeguard a communal hearth.

An Atlanta neighborhood tries to preserve ‘a sense of place’

Cynthia Poe worries about getting squeezed out again.

Originally from Durham, North Carolina, Ms. Poe, a human resource manager, watched as a white developer bought up that city’s historic “Black Wall Street,” part of a gentrification wave that saw long-overdue investment in disadvantaged neighborhoods ironically result in massive displacement of poorer, mostly Black residents.

She fled her no-longer-familiar neighborhood with its rising taxes late last year, only to land in the same situation in her new home: the majority-Black, working-class neighborhood of Grove Park in Atlanta. Once a thriving white community, Grove Park saw white flight in the 1960s. Redlining by banks and other financial institutions limited investment as Black people moved in. There are no major grocery store chains and no pharmacies. Some houses remain set on dirt roads.

But interest among white Atlantans is on the rebound. From her stoop, Ms. Poe watches a familiar ritual as real estate investors walk the streets, pointing and buying. Debra Edelson, executive director of the Grove Park Foundation, describes the process as “white money pushing out Black people.”

That could once again include Ms. Poe. Rents have doubled, and property values are putting houses out of reach of her budget. A newly built, three-bedroom house is on the market for $409,000 – in a neighborhood where the average annual income is $23,000. “It goes so fast,” says Ms. Poe. “And it’s not as if you can lose something. You will lose something.”

The phenomenon of “gentry” moving into working-class areas is hardly new. Neither is the displacement caused by what could be termed the “brew pubification” of a neighborhood. Indeed, more than a decade after the housing crash of 2008 – and with millions of Americans now at risk of losing their homes due to the pandemic – the transformation of Grove Park is part of a national pattern long mired in race, class, and not-in-my-backyard policies.

Despite decades of efforts to break this pattern, fundamental questions remain unanswered: What makes a place a neighborhood? And what does that term really mean?

The need for answers is particularly dramatic in Atlanta, where many residents wear hoodies that say “Atlanta influences everything.” Yes, the city helped tip a national election and put a focus on racial reckoning. But struggles to provide affordable housing and social mobility for Black residents has the city itself at a demographic tipping point. Predictions indicate that in 30 years, the Black population of Atlanta could go from just over half to only one-third – with white residents making up a third and Asian and Hispanic Atlantans making up the rest.

“Cities need to think more strategically about the mix of population, because as the working-class population is displaced and scattered, you have changing social relations, longer commutes – social fragmentation that changes the identity of place,” says Euan Hague, a geographer at DePaul University in Chicago.

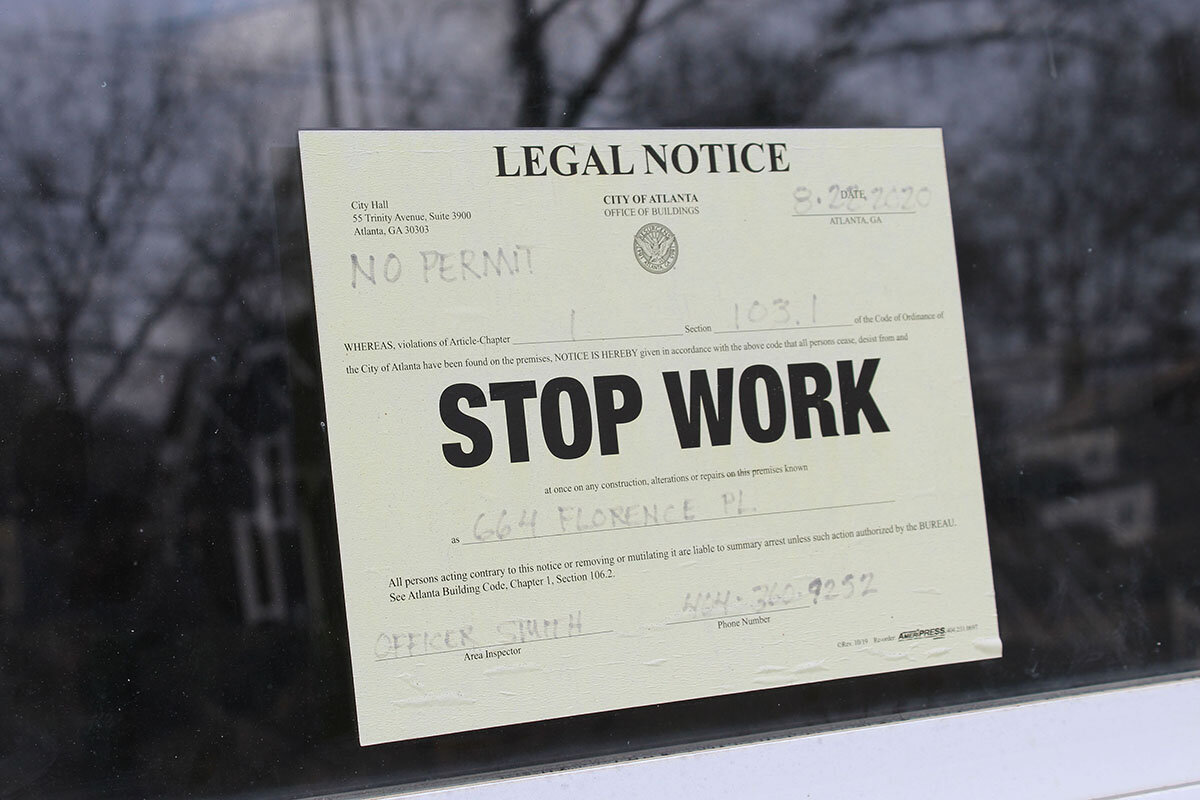

Facing rapid gentrification, Atlanta pushed the pause button, placing a building moratorium on Grove Park and several other neighborhoods. Such stoppages are blunt tools that may ultimately exacerbate housing problems, given that the root cause of skyrocketing prices and rents is a limited supply. Yet they can also give some breathing room to address evolving values that may hold the answer – and outline the challenges – to building diverse and vibrant neighborhoods, rooted in history.

A tug of war over a “community fridge”

“When white people move in, they need to differentiate themselves, sometimes by renaming entire neighborhoods,” says Kathryn Rice, an Atlanta housing activist. “We don’t like to think of racism in liberal, progressive Atlanta, but it’s still true. The city is still very, very segregated. And in gentrifying areas, you’re getting a clash between what values are there versus new ones, which leads to power struggles.”

Those struggles play out in small, but illuminating ways.

In the gentrifying neighborhood of Pittsburgh, about six miles from Grove Park, a group of residents placed a “community fridge” in a city park to help struggling neighbors during the pandemic. But four households – three white, one Black – complained. Though there had been no incidents involving the fridge, the neighbors worried about crime and the impact on their property values. A few days later, the fridge was moved to a new location.

For many, the struggle comes down to how to define a neighborhood. Is it a loose assemblage of groups and alliances working to improve property values, or a distinct place with a history that prizes people over profit?

“A neighborhood is a culture of reliance on different people: You know who you can borrow money from, who can watch your kids,” says Kamau Franklin, a Pittsburgh resident. “It’s a community and a culture. But people don’t think of it like that. They see poor folks who can be disposed of.”

As Atlanta demonstrates, that feeling of being disposable is not necessarily attached to race. In this majority-Black city, those displaced and those with the authority to help them tend to be the same race.

Despite nearly 50 years of Black leadership, the city has fallen far short of promises to replace thousands of razed public housing units with affordable housing. Lack of economic mobility for poorer Black residents is more pronounced in Atlanta than almost anywhere else in the U.S., with the median household income of white families almost three times that of Black families.

That state of affairs, at least in part, is the result of Black mayors looking forward more than looking back, says Ms. Edelson of the Grove Park Foundation.

Ron Daniels, founder and president of the Institute of the Black World 21st Century, has urged cities like Atlanta to view the impact of gentrification as an existential and immediate threat to Black culture.

“Many of these mayors were not equipped to deal with the phenomena of gentrification and may even be complicit,” says Mr. Daniels, who convened a 2019 National Emergency Summit on Gentrification. “If you do certain kinds of development without understanding the nature of market forces, then you are contributing to the displacement of Black people and culture without being aware of it. And some may be aware of it.”

Balancing progress and “a sense of place”

After the city invested tens of millions in a new park-and-trail system near Grove Park, Microsoft announced last month the purchase of a large parcel in the middle of the neighborhood for a new corporate campus.

To be sure, Microsoft President Brad Smith has vowed not only to hire from Atlanta’s Black educated class, but also to work to keep the neighborhood diverse. The problem, says Ms. Edelson, is that the speed of change will profoundly reorder the neighborhood long before Microsoft opens its doors.

But there are signs of progress. About a decade ago, a collaborative effort succeeded in revitalizing East Lake, a neighborhood on the other side of the city. The nonprofit Purpose Built Communities, which makes affordable housing a top priority for redevelopment, grew out of that effort and now supports revitalization not only in Atlanta but around the country.

In the last three years, Atlanta has added 5,600 affordable housing units, and the mayor recently signed an executive order investing $50 million in bond funding for affordable housing.

Efforts that other cities are exploring might help Atlanta as well – such as policies that set aside a percentage of tax revenues from rising property values to be reinvested as low-income housing. Addressing not-in-my-backyard policies that restrict affordable multifamily housing could help too.

“It might be different if it was easier to build everywhere, where every neighborhood is changing at a gradual rate – so instead of a firehose on this one area, the whole city gets a gentle watering,” says Evan Mast, an urban economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a nonpartisan organization in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

For now, Ms. Edelson calls Grove Park a “grand social experiment.” But “everyone has to be rowing in the same direction, otherwise we just get run over,” she says.

The problem for Ms. Poe and others isn’t gentrification per se. After all, Grove Park saw the opening of a new YMCA, an old community theater is being renovated, and more services and stores are all coming.

The point, she says, isn’t to keep the neighborhood Black, but to keep it culturally vibrant – and to safeguard a communal hearth.

But without a common narrative about what it means to be a neighborhood – and the sense of belonging that comes with it – improvements may be temporary, she fears.

“Yes, people will come, but without a sense of place, they will leave just as fast.”

Editor's note: The story has been updated to indicate that the community fridge was moved to a new location.

Books

Where American women’s ambitions took wing at midcentury

American society in the mid-20th century placed strictures on women’s ambition. But some were able to gain independence in ways that helped change attitudes and laid the groundwork for greater numbers of women pursuing fulfilling careers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Barbara Spindel Correspondent

The young women who aspired to be writers, models, and stewardesses, as they were then called, predated the women’s liberation movement. “The rules were clear, and the expectations sky-high. ... Women should go to college, pursue a certain type of career, and then give it up to get married,” writes Paulina Bren in “The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free.” These were not merely conventions: Legally, stewardesses could be fired when they turned 32 or 35, depending on the airline, or when they got married.

The women who served on flights were able to see the world – while waiting until “the public position of women back home shifted enough to accommodate their ambition,” Julia Cooke writes in “Come Fly the World: The Jet-Age Story of the Women of Pan Am.” Eventually, of course, it did, as masses of women organized to challenge gender discrimination in all aspects of American life.

Where American women’s ambitions took wing at midcentury

“Stewardess wanted. Must want the world,” read a 1967 recruitment ad for Pan Am. Women had limited options in those days, but two terrific books show how some made the most of what was available. Julia Cooke’s “Come Fly the World: The Jet-Age Story of the Women of Pan Am” follows several stewardesses (as they were then known) who put up with weight checks and other indignities to live and travel independently. Paulina Bren’s “The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free” is a history of New York City’s premier women-only residential hotel, which, for decades after its 1928 opening, served as home base for thousands who came to the city to chase their dreams.

The Barbizon was known for housing a particular kind of woman: young, attractive, and middle- to upper-class. (For most of its history, white went without saying.) Men were forbidden from venturing beyond the lobby, though many tried. J.D. Salinger was among those who frequented the hotel’s coffee shop trying to meet women.

The Barbizon’s clientele included models, aspiring writers, and students at the Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School, which took up three floors in the building. For the “Gibbs girls,” a stint in the city as a secretary could provide an interlude between school and marriage. The hotel’s most storied relationship was with Mademoiselle magazine, whose prestigious guest editor program brought 20 college students from around the country to New York each June to shadow the magazine’s editors. During the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, the program was “the most sought-after launching pad for girls with literary and artistic ambitions,” writes Bren. Recipients of the coveted positions, all of whom stayed at the Barbizon, included Joan Didion, Ann Beattie, and Sylvia Plath, whose 1963 novel “The Bell Jar” is a fictionalized account of her 1953 summer in New York.

Bren elegantly weaves interviews with former residents and archival research with context on the social and political conditions that limited midcentury women. She devotes attention both to those glamorous residents who made it big, including Joan Crawford and Grace Kelly, and those who tried and failed to live autonomously. She finds evidence of a number of suicides that the hotel tried to keep under wraps.

Many of the traits Bren describes in the Barbizon residents – a yearning to do more, to see more, to be more – are apparent in the women that Cooke profiles in “Come Fly the World.” In the early days of air travel, their job had been done by men, but one 1933 article in The Atlantic Monthly approved of the shift from stewards to stewardesses, observing of nervous flyers, “The passengers relax. ... If a mere girl isn’t worried, why should they be?” The positions were competitive: The author notes that in the early 1960s, only 3%-5% of those who applied got the job. They were also held mostly by white women. Only 50 Black women were working as stewardesses across all airlines in the United States in 1965.

Much of Cooke’s engaging narrative focuses on the unheralded role of these women during the Vietnam War. Several of those she profiles – whose intelligence and bravery offer a corrective to the over-sexualized and subservient images then promoted in pop culture (and often by the airlines themselves) – regularly worked Pan Am flights that ferried soldiers to R&R trips in Hong Kong and other cities. The work was dangerous. The book culminates with a gripping account of the women’s involvement in Operation Babylift, which, at the war’s end, evacuated several thousand Vietnamese orphans from Saigon to the U.S.

What Bren says of the Barbizon residents who predated the women’s liberation movement is also true of Cooke’s subjects: “The rules were clear, and the expectations sky-high. ... Women should go to college, pursue a certain type of career, and then give it up to get married.” These were not merely conventions: legally, stewardesses could be fired when they turned 32 or 35, depending on the airline, or when they got married.

The women who served on flights were able to see the world – while waiting until “the public position of women back home shifted enough to accommodate their ambition,” Cooke writes. Eventually, of course, it did, as masses of women organized to challenge gender discrimination in all aspects of American life.

On Film

Oscar hopeful ‘The Truffle Hunters’ is a dog-lover’s delight

Tony foods and dogs don’t usually mix. But as this Oscar-shortlisted documentary endearingly depicts, you sometimes can’t have one without the other.

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

Oscar hopeful ‘The Truffle Hunters’ is a dog-lover’s delight

Being neither a gastronome nor a fan of foodie films – they make me hungry! – I was reluctant to see a documentary called “The Truffle Hunters.” On the other hand, it turns out that truffles – basically mushrooms with a really expensive price tag – are tracked in the woods by dogs specifically trained by their owners to sniff them out. Since I’m a dog lover, this was good news.

So is the movie, directed by Michael Dweck and Gregory Kershaw. Shortlisted for an Oscar, it focuses on a vanishing subculture of largely octogenarian male truffle hunters in the Piedmont forests in Northern Italy where the most prized specimens are to be found.

Among the cadre of codgers is Carlo who, much to the consternation of his hypernervous wife, still makes forays into the forest with his beloved dog Titina. He especially likes to go out at night because he loves hearing the hooting of the owls.

There’s also Aurelio, a bachelor whose piebald soul mate, Birba, with her renowned nose for truffles, is his greatest joy. He takes bubble baths with Birba, then blow-dries her. He shares meals, peeling pears for her. He sings to her. He confesses to her his fears about what will happen to her when he dies. He decides he needs to meet a “wild woman” who will take care of her. Birba takes it all in philosophically.

Aurelio is asked early on by a much younger truffle hunter if he wouldn’t mind divulging his secret spots in the forest. After all, the young man argues with apparent sincerity, why let all that hard-won knowledge be forever lost? Aurelio’s response is “Never!” He is as cranky with humans as he is loving with Birba.

Then there’s Angelo, who is so curmudgeonly that he makes Aurelio seem angelic by comparison. A master truffle hunter with a striking resemblance to Rasputin, he lives alone in the forest and no longer plies his trade because he believes, not entirely without cause, that it’s been overtaken by unscrupulous merchants and poachers, some of whom poison rival dogs. At one point we see him tapping out a screed on his ancient manual typewriter, looking like nothing so much as a chain-smoking mad monk. In one of his rare light moments, Angelo tells an acquaintance that he used to be a circus acrobat. He claims he turned down 50 marriage proposals. Part of his appeal, apparently, was his expertise in walking on stilts.

I would like to have learned more about the younger lives of these men. Doing so would have deepened the portraiture. As it is, what we are presented with is essentially a boisterous gallery of aging oddballs. But to their credit the filmmakers never make fun of them. Their eccentricity, because it is rooted in a passion for the natural world, has an innate dignity.

The men come off favorably compared with the merchants and auctioneers also featured in the film. One of the buyers is shown eating lunch with his young daughter as he explains to her that he never eats truffles because basically it’s all just a business to him. At various times we overhear him with hunters as he lowballs the price of their truffles. Then we see the hunters’ large, knobby, white bounties laid out for top dollar in tony auctions.

But I don’t wish to characterize the film as some kind of upper-class versus working-class indictment. It’s more complicated than that. What I ultimately took away from the documentary is the deep love that can exist between owners and their dogs. In “The Truffle Hunters,” both are shown to be the custodians of each other’s happiness. When Carlo, bucking his wife’s admonition, sneaks out through an open window with Titina to savor the night forest, the nutty bliss of the moment suffuses the screen.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “The Truffle Hunters” opens in select theaters March 5.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

What France can learn from US Black churches

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a new book about Black Christianity in America, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. offers a lively portrait of an institution that has done as much to shape the character of the United States as it has for Black people themselves. That history holds lessons not only for the U.S. of today but for Europe as well, especially in its relationship with Muslim minority communities.

While the U.S. has seen progress for its minorities over decades, France, which is host to Europe’s largest Muslim population, has only begun to deal with its challenging issues with that minority. Later this month the French Senate is expected to put the finishing touches on a bill that, while not explicitly mentioning Islam, is clearly designed to regulate its structure and practice in France.

Islam’s steady growth in Europe is forcing the Continent to adjust to the changing composition of its societies. Economic discrimination and racism against Muslims – one of the drivers of radicalization – require urgent remedies. As refuges for those who are marginalized, Europe’s mosques, like America’s Black churches, can be rich incubators for good – partners in the pursuit of a mutual accommodation and recognition of the dignity in everyone.

What France can learn from US Black churches

In a new book about Black Christianity in America, Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. offers a lively portrait of an institution that has done as much to shape the character of the United States as it has for Black people themselves. The Black Church, he writes, is a story in three parts: “of a people defining themselves in the presence of a higher power”; “of their journey to freedom and equality in a land where power itself – and even humanity – for so long was (and still is) denied them”; and of the secular contributions to American culture, justice, and knowledge that were forged in its pews.

“It’s the place where we made a way out of no way,” Dr. Gates writes in “The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song.”

That history holds lessons not only for the U.S. of today but for Europe as well, especially in its relationship with Muslim minority communities. Most of those Muslims have roots in former European colonies, both Arab and African, and are struggling to find their place in societies that are dominantly Christian or secular – and that are often less than welcoming.

While the U.S. has seen progress for its minorities over decades, France, which is host to Europe’s largest Muslim population, has only begun to deal with its challenging issues with that minority group. Later this month the French Senate is expected to put the finishing touches on a bill that, while not explicitly mentioning Islam, is clearly designed to regulate its structure and practice in France. It includes a ban on online hate speech, restrictions on foreign funding for mosques, added regulations for home schooling, and a certification program for Islamic imams in France.

The bill emerged after attacks by Islamist extremists last October, including the beheading of a teacher for using cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad during a lesson on free speech. Critics see the bill as political pandering and deeply discriminatory. Islamophobia is already shaping debates ahead of regional elections in June and next year’s presidential election. A poll in January showed right-wing populist Marine Le Pen, a persistent opponent of Islam, trailing President Emmanuel Macron by just a few points.

Mr. Macron argues that the purpose of the bill is to reinforce his country’s unique tradition of secularism. He appears to have an unlikely ally. In France, freedom of religion means freedom from another person’s public practice of their faith. That ideal enjoys broad support among Muslims.

An Ipsos survey last year found that 81% of French Muslims had a positive view of secularism, 82% said they were proud to be French, and 77% said they had no trouble practicing Islam.

Moderate Muslim leaders argue the bill’s ban on foreign financing and influence will help French Muslims practice Islam in ways that are consistent with France’s secular principles. The important point, they argue, is to support change from within the mosque.

“Islam must be reformed, no longer political. It has to assume that the laws of the 7th century sharia are not valid in the 21st century,” argues Razika Adnani, a member of the Foundation for Islam of France. “The state cannot enter religious affairs, but it demands that Muslims reform their religion.”

Islam’s steady growth in Europe is forcing the Continent to adjust to the changing composition of its societies. Economic discrimination and racism against Muslims – one of the drivers of radicalization – require urgent remedies. As refuges for those who are marginalized, Europe’s mosques, like America’s Black churches, can be rich incubators for good – partners in the pursuit of a mutual accommodation and recognition of the dignity in everyone.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Baptism and spiritual progress

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Christine J. Driessen

As we learn more of our nature as God’s children, it becomes easier to let go of unhelpful ways of thinking and acting – as a woman experienced after pride and self-righteousness led her down an undesirable path.

Baptism and spiritual progress

We hear of dancers, musicians, gymnasts, and others who have to repeat every step, note, or maneuver until it is absolutely perfect before that final performance or competition. And the process doesn’t stop there, but continues with every new opportunity to improve.

I’ve found this a helpful analogy for the concept of baptism. Christian Science illustrates that the idea behind baptism is relevant to everyone! It is a refining, purifying process similar to what silver or goldsmiths do when they refine their precious metal in a hot fire to prove its purity and make it shine more brightly. “Take the impurities out of silver,” the Good News Bible explains, “and the artist can produce a thing of beauty” (Proverbs 25:4).

So what does this have to do with us? The Old Testament prophesied repeatedly of the coming of the Christ to purify hearts (see, for instance, Malachi 3:1, 3). The Christ does this by chipping away, washing away, burning away whatever in our consciousness does not look like God’s creation – the beautiful, good, and pure. Our role is to be receptive to Christ, to let divine Truth transform our hearts.

This is the baptism that takes place naturally as we learn more of our true, spiritual nature as God’s children, the expression of God’s goodness. It is ongoing, moment by moment. The natural result is that our love for God – divine Love itself – and for God’s spiritual creation (all of us) is purified, and it becomes easier to let go of the errors – the selfishness, negative thinking, and destructive behavior – that cause suffering.

I had an experience like that many years ago. After having one success after another in various areas of my life, I felt that I knew it all and that the sky was the limit when it came to my talents and wisdom!

Then I had an important decision to make. As I often do when faced with some difficulty, I turned to God in prayer for guidance. The answer I received felt very clear and strong. However, my pride was pushing me in a different direction, so I argued with God. And I chose the path that self-righteousness and a willful attitude pushed me toward. What followed was several years of suffering as I tried to extricate myself from what was clearly a wrong path.

Then began the baptism and regeneration. In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, explains: “Self-love is more opaque than a solid body. In patient obedience to a patient God, let us labor to dissolve with the universal solvent of Love the adamant of error, – self-will, self-justification, and self-love, – which wars against spirituality and is the law of sin and death” (p. 242).

During that period, as I became more receptive to the “universal solvent” of divine Love, I experienced some awe-inspiring physical healings and resolution of financial difficulties. I began to realize that the real source of qualities that bring success is God, Spirit, not me or any person. In order to experience God’s infinite, uninterrupted goodness, we need to let go of our own agendas, follow God’s will, and purify our love.

I was experiencing something of the mental baptism Mrs. Eddy describes as taking place in three stages in “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896” (see pp. 203-207):

“First: The baptism of repentance is indeed a stricken state of human consciousness.... a mortal seems a monster, a dark, impenetrable cloud of error; and falling on the bended knee of prayer, humble before God, he cries, ‘Save, or I perish.’ Thus Truth, searching the heart, neutralizes and destroys error....

“Second: The baptism of the Holy Ghost is the spirit of Truth cleansing from all sin; giving mortals new motives, new purposes, new affections, all pointing upward....

“In mortal experience, the fire of repentance first separates the dross from the gold, and reformation brings the light which dispels darkness....

“Third: The baptism of Spirit, or final immersion of human consciousness in the infinite ocean of Love....”

The spiritual regeneration that took place in my thinking lifted me out of the darkness of self-righteousness, and I gained a heightened sense of God’s unfailing care. It turned my life around.

Rather than leading to suffering, spiritual baptism reveals God’s masterpiece – each one of us as a pure, spiritual expression of the Divine – which leads to more freedom, health, and an unshakable peace.

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article on spiritual ideas meeting daily needs, please click through to a recent article on www.JSH-Online.com titled “When we couldn’t afford to heat our home.” There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

Immersed in art

A look ahead

That’s all for today. Join us tomorrow when we look at the world’s leverage to counter Myanmar’s coup.