- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Democracy after 2020: ‘Beleaguered but not defeated’

“Democracy today is beleaguered but not defeated.”

That’s the bottom line of Freedom House’s just-released annual report on the state of democracy around the world.

In a pandemic year of economic and physical insecurity, democracy’s defenders faced many setbacks and defeats. From Algeria to Belarus to Hong Kong, authoritarians used force to stifle protest and settle scores, sometimes in the name of public health, according to Freedom House, a private group founded in the depths of World War II to fight fascism.

Countries where democracy deteriorated, a group that includes the United States, outnumbered those where it improved by a substantial margin.

But that is not all the story. Democracy is “remarkably resilient,” says the study, and “has proven time and again its ability to rebound from repeated blows.”

Take Malawi. Despite threats and offered bribes, Malawi’s constitutional court issued a landmark ruling in February 2020, ordering a new national election due to credible evidence of vote tampering. In June, opposition presidential candidate Lazarus Chakwera won the rerun by a comfortable margin.

In Taiwan officials suppressed the coronavirus effectively without resorting to coercive measures, in the face of ramped-up threats from an increasingly aggressive China. Taiwanese voters ignored a multipronged Chinese disinformation campaign to reelect incumbent President Tsai Ing-wen, who opposes reuniting with the mainland.

Despite the coronavirus, countries in all the regions held successful elections, including Montenegro and Bolivia.

Democracy’s “enduring popularity in a more hostile world and its perseverance after a devastating year are signals of resilience that bode well for the future of freedom,” concludes Freedom House.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Are Myanmar's generals open to persuasion? Depends who’s persuading.

Myanmar’s generals have cut short a fitful opening to the world that led to greater connectivity, which in turn offers potential leverage for foreign diplomats.

Foreign powers seeking to rein in Myanmar’s military junta that seized power on Feb. 1 are hoping to leverage the country’s increased connectivity with the rest of Asia. So too are the pro-democracy protesters who braved live gunfire this week to oppose the junta and have built ties with activists across the region.

For decades, Myanmar’s military rulers preferred isolation to outside engagement. Over the last decade, however, under a semi-civilian government, Myanmar slowly opened up its economy and society. This has created potential leverage points for diplomats who want to steer the country out of its current crisis.

At the same time, experts caution that Myanmar’s regional integration may be working to stall collective action in the form of economic sanctions on the regime. Instead, Asian capitals want to keep channels open for diplomacy and persuasion; the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, to which Myanmar belongs, has declined to take a proactive stance on the crisis.

Moreover, the mindset of Myanmar’s military may blunt the effectiveness of punitive measures by the Biden administration and its democratic allies. Targeted sanctions against the generals “can impose a little cost, but most of these guys have spent their entire lives as international pariahs. These are not cosmopolitan leaders,” says Gregory Poling at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Are Myanmar's generals open to persuasion? Depends who’s persuading.

As Myanmar’s pro-democracy protesters brave gunfire from security forces that killed scores of civilians this week alone, the international community is seeking ways to rein in the military junta that seized power last month.

Potential leverage points to help steer the Southeast Asian country out of the current crisis stem from 10 years of political, economic, and social opening under a semi-civilian government that abruptly ended on Feb 1. The decade of reform had begun to plug Myanmar and its 57 million people into Asia’s dynamic economies after decades of impoverished isolation.

But whether Myanmar’s new connectedness can translate into greater pressure on its military rulers remains an open question, experts say. In fact, resource-rich Myanmar’s regional integration may be working to prevent a tougher public stance toward the coup leaders, as Asian countries want to keep channels open for diplomacy and persuasion.

Regional powers in Southeast Asia, as well as China, Japan, and the United States, have widely differing levels of both influence and political will to persuade the military to return to the democratic path in Myanmar.

Equally if not more important are the ways in which Myanmar’s opening has created new connections between Myanmar’s people – especially the protest movement and civil society – and the rest of the world.

“The last 10 years have seen Myanmar open up to the outside world, and that’s created a boom both in incoming investment and trade,” says Gregory Poling, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“It’s also created a boom in information technology. Everybody now has internet-connected 4G phones; everybody’s on Facebook,” he says. “It’s certainly a different world in Myanmar than it was a decade ago, and the generals are finding that out the hard way as they try to clamp down on these protests, and find that they are much more adaptive and resilient.”

A young generation that came of age enjoying new freedoms and connectivity is now joining the ranks of protesters in Thailand, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, using social media to trade ideas and build solidarity.

A muted statement

The 10-nation Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which promotes regional integration and diplomacy, has a major stake in ending the crisis in Myanmar, a member state. Yet hampered by internal divisions and institutional paralysis, the regional bloc could only muster a muted statement this week that called for “all parties” in Myanmar to halt violence and begin dialogue.

“This is a huge headache for ASEAN,” says a Southeast Asia expert who spoke on condition of anonymity due to security concerns. “It’s very difficult for ASEAN to be in the driver’s seat [of the regional agenda] when one member is dragging it down.”

Moreover, ASEAN members oppose broad economic sanctions on Myanmar, arguing they would only hurt ordinary people – and push the regime further toward China, Myanmar’s largest trading partner and its second biggest investor, after Singapore. Japan and Thailand are also major investors.

Despite growing connectivity, ASEAN “is between a rock and a hard place” on Myanmar, says Mr. Poling. “They worry that if it returns to full-on pariah status, it will become a weight around the neck of the organization,” he says.

The fear is that sanctions would “back the generals into a corner and make them even more violent and less susceptible to international cajoling,” he says. Instead, ASEAN now seeks to establish itself as a conduit for outside parties to talk to the generals and urge them toward compromise, he says.

Nevertheless, some investors may be reconsidering their ties to Myanmar. In Singapore, “investors … are beginning to re-evaluate their investments in Myanmar’s economy,” Singapore’s minister for foreign affairs, Vivian Balakrishnan, said in a statement.

Japan, another country with growing economic ties to Myanmar, is also a major aid donor. “Japan might be one of the few actors that has the economic incentives, the leverage on all sides, and the willingness to try to do something about the situation,” says a researcher in Thailand with extensive experience in Myanmar who requested anonymity for security reasons.

For example, Tokyo’s special envoy to Myanmar, Yohei Sasakawa, chairman of the Nippon Foundation, recently helped negotiate a cease-fire between the military and insurgents in the western state of Rakhine, even as political tensions built up after pro-democracy parties swept the November election.

This level of trust with Myanmar’s generals, including with coup leader Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, offers a potential opening for Mr. Sasakawa and other Japanese envoys to urge the military to restore civilian rule, the researcher says.

Analysts say Japan prefers mediation over punitive economic measures that could isolate Myanmar and push it toward China.

A Chinese sphere of influence?

For its part, Beijing’s sway in Myanmar is perhaps greater than that of any other country. But the historic mistrust of China among Myanmar’s military leaders and the public – as well as China’s doctrine of non-interference – make it unlikely that China will play a proactive role that goes beyond securing its strategic economic interests in Myanmar.

Beijing “is in a somewhat awkward position” as the result of the coup, said Derek Mitchell, president of the National Democratic Institute and former U.S. ambassador to Myanmar, in a recent podcast.

Above all, China seeks to maintain what it considers a privileged position and sphere of influence in Myanmar, while blunting the involvement of the United States and other Western countries, Ambassador Mitchell says.

Experts stress that a key source of leverage over Myanmar’s coup leaders are the financial interests of top generals who have profited from the country’s opening. “The leverage anyone has is around parochial issues of money and physical security,” says the Southeast Asia expert. “No one should lose sight of that.”

Toward that end, the United States, Britain, Canada, and the European Union have imposed new sanctions on Myanmar’s military leaders. U.S. officials last month blocked a move by Myanmar’s military rulers to move about $1 billion held at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and put a freeze on the funds, Reuters reported Thursday.

Ultimately, however, the biggest obstacle to military rule is popular support for democratic rule that has flourished over a decade of opening.

Protesters in Myanmar have learned from similar pro-democracy movements in Thailand and Hong Kong, and have built ties with fellow activists – the “Milk Tea Alliance” – to help sustain their effort.

Targeted sanctions against Myanmar’s military chiefs “can impose a little cost, but most of these guys have spent their entire lives as international pariahs. These are not cosmopolitan leaders,” says Mr. Poling.

“Any influence that the international community – whether it is the U.S. or Japan or Singapore – has is really going to be on the margins. If the protests in the streets get 99% of the way there, the U.S. and Europeans and Japanese can help push it the last 1%.”

Why Saudi Arabia (still) tests limits of US influence

Why did the U.S. shrink from stronger action with Saudi Arabia over the Khashoggi killing? One reason the kingdom is resistant to U.S. influence: It sees itself as an equal partner.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

When Saudi Arabia’s founder, Ibn Saud, and President Franklin Roosevelt entered an agreement in the waning days of World War II in 1945, they did so as equal partners forging an alliance of mutual interests. That equality explains a lot about the limits of U.S. influence experienced by American presidents since.

After releasing the U.S. intelligence report on the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, the Biden administration came under fire for not dealing more harshly with the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman.

State Department spokesman Ned Price addressed the fundamental tensions that exist in the relationship. “We seek to accomplish a great deal with the Saudis,” he said, “but we can only address these many important challenges in a partnership with Saudi Arabia that respects America’s values.”

But the U.S. has limited sway with a partner that sees itself as independent.

“The Saudis ... don’t expect to be talked down to,” says David Rundell, former chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Riyadh. “Saudi Arabia is a country where personal relationships matter a great deal. There are limits to how antagonistic you can be without severely damaging your own interests. We are approaching those limits.”

Why Saudi Arabia (still) tests limits of US influence

The Biden administration’s release of a report implicating Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi met with swift criticism in the United States.

The move was long on talk and lacking in penalties for the prince, said rights activists, a former CIA director, and members of Congress from both parties.

Even when coupled with the recent suspension of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, the release of the report was seen as falling short of President Joe Biden’s campaign pledge to treat the kingdom, a longtime U.S. ally, as a “pariah.”

But in Saudi Arabia, the actions were seen as going too far. By publicly “embarrassing” the crown prince, the kingdom’s supporters say, President Biden is explicitly undermining and interfering with the already-fraught Saudi line of succession.

With an independent Saudi Arabia that views itself as an equal partner – and which pursues social liberalization for its own internal reasons – a new White House is facing the limits of a values-based foreign policy and its ability to influence an ally’s behavior.

And with the administration’s clarification this week that it’s seeking a “recalibration” of the Saudi relationship to be in line with American values, it essentially admitted to the difficult balancing act every modern president has faced: to engage with a partner with vast shared strategic interests and few common values.

“Frank message”

The release of the Khashoggi report comes amid a series of moves meant to express the administration’s displeasure with Riyadh.

Last month President Biden stressed he would work only with King Salman, refusing to engage with the crown prince, the de facto ruler, as his predecessor did.

In addition to halting offensive weapons sales, the administration suspended existing arms sales to the kingdom for an intensive review, and an envoy was sent to facilitate talks to end Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen.

It also barred 76 Saudi individuals involved in anti-dissident operations from entering the U.S., and invoked the Magnitsky Act, which targets human rights offenders, to sanction members of the so-called Rapid Intervention Force, a unit of the Saudi royal guard engaged in counter-dissident operations.

The administration said the moves sent a “frank message” to Saudi leaders setting out new “expectations” for the relationship.

“We seek a partnership that reflects our important work together and our shared interests and priorities, but also one conducted with greater transparency, responsibility, and accord with America’s values,” State Department spokesman Ned Price said at a press conference.

“The choices that Riyadh makes will have outsized implications for countries in the region and countries beyond the region, including the United States,” he said. “We seek to accomplish a great deal with the Saudis, but we can only address these many important challenges in a partnership with Saudi Arabia that respects America’s values.”

Values and interests

Indeed, State Department and White House officials mentioned American “values” in that context nearly a dozen times.

Traditionally, values factored little in an alliance in which Saudi Arabia guaranteed oil supplies and supported regional U.S. initiatives in return for protection against external threats.

And the White House notes that the shared interests are many: regional stability, ending the war in Yemen, bringing Iran back to the negotiation table, achieving peace between Israel and the Palestinians and the wider Arab word.

Although the U.S. has largely weaned itself off Saudi oil, maintaining influence over the largest producer of fossil fuels and China’s largest supplier of oil remains a geostrategic interest for Washington.

Yet these strategic interests have done little to paper over the gap in values with an autocratic kingdom that has different views on individual rights, a vastly different legal system, and a male custodial system that for decades governed the lives of women.

According to a U.S. diplomatic source with experience in Saudi Arabia and knowledge of the policy debate in Washington, the administration weighed calls to penalize MBS, as the crown prince is known, against Saudi support for regional and global efforts, namely engaging Iran and countering China’s influence.

“To rebuild global leadership, you need partners in each region in the world; although there may be disagreements and we have different views of human rights, the Saudi relationship at the end of the day has been a strong partner,” said the source, who was not authorized to speak to the press on the record.

Independent kingdom

Observers and diplomats say the constraints on U.S. leverage with Saudi Arabia – and the reasons for inflated expectations in Congress and among the American public – are tied to misconceptions over the relationship itself.

Unlike the vast majority of Arab states, Saudi Arabia was never colonized by the West.

Saudi Arabia’s founder, Ibn Saud, came to power through conquest and alliances rather than being selected by European powers to rule a vassal state in their name.

When the king and President Franklin Roosevelt entered an agreement in the waning days of World War II in 1945, they did so as equal partners, two independent states forging an alliance of mutual interests.

Unlike Egypt or Jordan, Saudi Arabia does not receive U.S. financial aid or in-kind assistance; instead, it often funds U.S.-led ventures in the region. Saudi Arabia pays for American military armaments and protection.

Although the U.S. has long pushed Saudi Arabia on human rights, it is often done behind closed doors, for cultural and political reasons.

“The Saudis are a proud people who expect to be treated as an equal and they don’t expect to be talked down to,” says David Rundell, former chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Riyadh and author of the book “Vision or Mirage: Saudi Arabia at the Crossroads.”

“Saudi Arabia is a country where personal relationships matter a great deal. There are limits to how antagonistic you can be without severely damaging your own interests. We are approaching those limits.”

Social liberalization

The White House has noted recent positive steps from Riyadh: the release of women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul and two Saudi American nationals; improved access for humanitarian aid to Yemen; and cooperation with newly appointed U.S. envoy Tim Lenderking to end the Yemen war.

The administration says it seeks the release of other activists, institutional reform, and a continuation of Saudi Arabia’s far-reaching social reforms.

Yet the U.S. has had little influence over the dramatic women’s rights advancements and other social reforms taking root in the kingdom, born out of Saudi self-interest.

Since King Salman assumed the throne and elevated his son MBS, they have transformed the kingdom by pursing two at times contradictory goals to cement stability: power consolidation and social liberalization.

Women’s emancipation, opening up the social and entertainment spheres, and neutralizing and marginalizing the orthodox religious establishment, are all viewed by the Saudi rulers as critical to paving the way for the kingdom’s post-oil economy.

While women previously faced several barriers to the workforce, they now work as top newspaper editors and deputy government ministers, as well as in public-facing jobs such as hotel concierges. The right to drive and other legal freedoms were granted in recent years.

These freedoms, along with the opening up of entertainment, sporting events, and the arts, target the hundreds of thousands of Saudis who studied in the West and are making up a new middle and upper-middle class. They also make Saudi Arabia a more desirable destination for foreign investment.

“For years and years, America and the West pressured Saudi Arabia about issues such as women’s driving, about liberalization of society and religious education reform, but nothing happened. This pressure proved ineffective,” says Najah al-Otaibi, a London-based Saudi analyst. “These reforms only happened when Saudis decided it was time to implement them.”

“Saudi Arabia knows its society, its cultural legacy, and its social contract, and it had to decide what was right for their country, what suits their people and what time-frame. They have invited America to engage on certain reforms, but they will not be pressured.”

Power consolidation

The flip side to these changes has been the autocratic, and sometimes ruthless, centralization of power at odds with U.S. values.

King Salman has changed the line of succession and reduced the decision-making process from slow-moving consultations among hundreds of royals, putting that power into the hands of one man, MBS.

This centralization has seen the jailing and forced kidnapping of dissidents and rival princes.

With delicate diplomacy, not pressure, observers say Washington can hope to influence social reforms that are in line with American values. Yet the U.S. may struggle to push the Saudis to rein in the autocratic measures adopted to push through rapid changes.

“Rather than just penalize, you want to encourage the positive reforms which they have embarked on completely independent of us,” says Mr. Rundell. “We can influence the Saudis on women’s emancipation, tackling corruption, education reform, and religious freedoms. These areas are where our interests coincide and where they can change things.”

The Explainer

Zoom isn’t carbon-free. The climate costs of staying home.

When work, play, and school go virtual, we might assume that at least our lives have become greener. There’s some truth to that, but the pandemic is raising the question: What’s the carbon footprint of a stay-home lifestyle?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

With more activities homebound during the pandemic, one result has been fewer cars commuting to workplaces or schools. But that doesn’t mean our lives are suddenly carbon-free.

Every time you send a message on Slack or search something on Google, you’re relying on data centers. These information factories are packed with servers and other equipment that use anywhere from 2% to 5% of the world’s electricity, and produce as much carbon dioxide as the aviation industry. An hour of high-definition video streaming can create up to a pound of CO2 emissions, similar to driving a mile in an average car.

People can take steps to minimize their environmental footprint, and possibly save time and money as well. These include limiting social media and gaming time, or deleting unnecessary files stored on the cloud. Watching video in standard definition, or doing a voice-only teleconference, can cut emissions dramatically.

Companies and lawmakers must also have a significant role to play, energy experts say, starting with ensuring greater transparency about internet companies’ data usage.

Jess McLean, a senior lecturer in geography at Australia’s Macquarie University, says “we need to have the structures in place that make sure it’s easy to make those environmentally sound decisions.”

Zoom isn’t carbon-free. The climate costs of staying home.

The pandemic has changed the way we live, work, learn, and socialize. For many, it’s forced daily activities online, and when people do log off and go outside, some have seen a world healing – smog clearing over cities, stars looking brighter, and wildlife returning to old habitats.

These observations reinforced a common belief that a digital world is an eco-friendly world. Experts say the reality is far more complicated.

How does working from home affect the environment?

Every time you send a message on Slack or search something on Google, you’re relying on data centers. These information factories are packed with servers, routers, and other equipment that makes the internet possible. Estimates vary, but in general, data centers are thought to use anywhere from 2% to 5% of the world’s electricity, and produce as much carbon dioxide as the aviation industry.

On a user level, researchers found that an hour of high-definition video streaming – be it the latest episode of “Bridgerton” or a Monday morning meeting – can create up to a pound of CO2 emissions, similar to driving a mile in an average car. That’s a high-end estimate, drawing on data gathered by the International Energy Agency. While the carbon output will often be much lower, based on factors like electric power sources and the graphics quality of a video stream, the key point is that digital lifestyles come with a carbon footprint.

In fact, there are many hidden environmental costs beyond greenhouse gases. Personal devices regularly break or become outdated, generating electronic waste, and those massive data centers also need land and water to operate.

The journal Resources, Conservation & Recycling recently published a first-of-its-kind study looking at the internet’s land and water footprints in addition to its greenhouse gas emissions. Researchers from Purdue University, Yale University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that data centers used roughly 687 million gallons of water every year, and had an estimated land footprint of 1,300 square miles, nearly three times the size of Los Angeles. On emissions alone, the group found data centers push out 97 million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year.

“Our energy systems in general are becoming less carbon intensive,” says Renee Obringer, a research fellow at the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center and lead author of the study. But especially as more countries embrace renewable forms of energy, she says it’s important to monitor those other environmental impacts.

Wait, so is it better to work from the office?

Not necessarily. Right now, videoconferencing is a necessity, and in many cases, there can be a net environmental gain to going digital, but experts want to push back on the assumption that online services are inherently green.

“We were originally sold this idea by corporations that having paperless offices would be an environmental benefit,” says Jess McLean, a senior lecturer in geography at Australia’s Macquarie University, who studies how digital technologies have become entrenched in modern life. “Thinking critically about whether digital tech is actually environmentally sustainable is not that convenient now.”

“It’s also the case that we don’t see a lot of the infrastructure that supports use of digital technology,” she adds, citing satellites in space, cables running underground, and servers stored in basements and windowless warehouses all around the world. “They are often not even understood as a part of our digital ecosystem.”

Digital companies can market themselves as “green alternatives” without reporting how much data, electricity, water, or land their products use. That kind of information would make it easier for scientists like Dr. Obringer to track the internet’s environmental footprint over time, and for consumers to educate themselves about their technology choices.

How can I make my online life greener?

There are several ways users can minimize their environmental footprint, and possibly save time and money as well. These include limiting social media and gaming time, deleting unnecessary emails and other files stored on the cloud, and downgrading streaming subscriptions.

“Reducing video quality can have a really big impact,” says Dr. Obringer. “Our study showed that by going from your 4k, Ultra HD Netflix plan and dropping that down to a standard definition, your personal footprint would be reduced by about 86%.”

This is true for Zoom, too. Based on researchers’ estimates, users can reduce their carbon footprint by 96% by turning off their camera during work meetings. For someone with daily meetings, using the voice-only option would also save 532 liters of water – roughly three bathtubs – and 1.7 square feet of land every month.

Pandemic or not, digital lifestyles have become ubiquitous. But a goal can be to rely increasingly on renewable sources of energy, while seeking to minimize other environmental impacts.

Both Dr. Obringer and Dr. McLean agree that companies and lawmakers have a significant role to play, starting with ensuring greater transparency about internet companies’ data usage.

“Individuals shouldn’t necessarily be held to account for the vast environmental costs of digital technologies,” says Dr. McLean. “In fact, we need to have the structures in place that make sure it’s easy to make those environmentally sound decisions.”

Commentary

Billie Holiday as activist: Can a movie change the singer’s image?

Honoring an individual’s humanity sometimes brings a nation’s progress to light. That’s what our commentator found in the new Billie Holiday film.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Nicole Duncan-Smith Correspondent

For most people, when they hear the name Billie Holiday, the civil rights movement isn’t what comes to mind. But her insistent performance of “Strange Fruit,” a haunting anti-lynching song, was her “I Have a Dream” offering to the world. This point comes through poignantly in the recent Hulu original movie “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” directed by Lee Daniels.

Suzan-Lori Parks’ screenplay and Andra Day’s performance in the starring role show Holiday not as someone who “disgraced her people” but as a complicated shero who tried with all her might to make a difference.

Inspired by a chapter in Johann Hari’s bestseller “Chasing the Scream,” Ms. Parks’ film dramatizes how Harry J. Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, brought Holiday down under the guise of the government’s war on drugs, all the while fearing that singing “Strange Fruit” would start a different war – a race war.

Without the overzealous policing of Anslinger’s federal department and with a society willing to provide help instead of punishment for her addiction, maybe the lady that sang the blues could have found a song of healing.

Hopefully, with this film, the world will listen to the melody of her life with new ears.

Billie Holiday as activist: Can a movie change the singer’s image?

History has been unkind to the memory of Eleanora Fagan, the jazz singer popularly known as Billie Holiday.

For years, her tragic demise was the subject of gossip columns, documentaries, and pop culture lore. But that could change now. More than 60 years after her death, the new Hulu original movie “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” directed by Lee Daniels, may have rescued and reshaped her legacy.

Throughout the critically acclaimed film, screenwriter Suzan-Lori Parks redeems the crackly voiced singer by bringing context to her pain and celebrating her valiant commitment to unveil the nasty national sin of lynching through the song “Strange Fruit.”

With this reframing by the Pulitzer Prize winner – coupled by the genius portrayal by ingénue Andra Day – the public has another way to see Holiday: not as someone who “disgraced her people,” as a character in the film puts it, but as a complicated shero who tried with all her might to make a difference. Together, the author and actor have crafted a forgiving narrative that positions the songstress in a fresh way. They show Holiday as one of the mothers of the civil rights movement, a voice of freedom-fighting compromised by an addiction that helped her numb the pain of poverty, exploitation, and Jim Crow. Though this is not the first film to note Holiday’s role as a civil rights activist, it does so especially effectively.

Unlike the 1972 “Lady Sings the Blues,” which earned five Academy Award nominations and won the most promising newcomer Golden Globe for Diana Ross, Ms. Parks’ film doesn’t use Holiday’s heroin addiction as a crippling catalyst to her demise. Instead, it presents a courageous, dignified, and talented character flawed by an extraordinary opioid addiction, a woman who warrants the viewers’ compassion and grace.

Inspired by a chapter in Johann Hari’s bestseller “Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs,” Ms. Parks’ film dramatizes how Harry J. Anslinger, the first head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, assigned a Black agent to go undercover to bring Holiday down for singing an anti-lynching song – under the guise of the government’s war on drugs. They believed “Strange Fruit” would start a different war – a race war.

Over and over, her managers and handlers, her husbands (one of whom set her up to be arrested), and those pushing dope into her body urged her to abandon her quest to perform the controversial song. But her calling to bring awareness to these “Southern trees [that] bear strange fruit” was greater than the payout of any cabaret, the high from her injections, or her fear of incarceration.

While the screenplay takes some creative license, there is no doubt that Holiday was targeted for speaking out – just as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Paul Robeson, Eartha Kitt, and members of the Black Panther Party were. (The Warner Bros. film “Judas and the Black Messiah” and the documentary “MLK/FBI” show the use of surveillance to bring down civil rights movement activists and supporters.)

The key difference was Holiday’s dependency.

Ms. Day’s Holiday is richly textured with a believable vulnerability, earning her a Golden Globe award for best performance by an actress in a motion picture – drama. Her portrayal packages the scars of the icon’s childhood (being raised in a brothel and working as a prostitute in her adolescence) with the longing to be deeply loved – and the perversion of settling for quick fixes. At the same time, it convincingly gives Holiday power in all of her brokenness.

Holiday is oftentimes dismissed as someone who died without honor and penniless. But in Ms. Day’s depiction, we see an entertainer – not unlike a defiant Bono from U2, Common, Aretha Franklin, or Kanye West (circa 2005) – break social norms with her interpretation of art juxtaposed with her social gaze. After all, “Strange Fruit’’ (written in 1937 by Abel Meeropol as the poem “Bitter Fruit”) was not just a cute, little ditty, but her “I Have a Dream” offering to the world.

Each painful break in her voice as she sang the song convicted the most shameful segregationist. Yet, to the likes of Anslinger, it was a confirmation of change bound to come to a progressing America.

The film may also point to another sign of progress by reminding viewers of the ungodly practice of criminalizing the disease of addiction.

In the scene before Holiday is sentenced to one year and a day in prison, she is stopped by the press on the stairway of the courthouse and asked about the possibility of incarceration. She flatly says, “I need help” – a revolutionary notion that law officials are now considering. Today, we are more compassionate about the opioid crisis plaguing the nation – offering support to those in the downward spiral of drug addiction and lobbying for laws that help instead of merely punish them.

Imagine if the media had not assisted in the degrading of Billie Holiday’s public image. Consider what her life would have been like if the overzealous policing of Anslinger’s federal department had not singled her out because of “Strange Fruit,” arresting her for drugs when it was the song that irked their sense of justice. Perhaps her life – and death – would have been completely different.

Maybe the lady who sang the blues could have found a song of healing, victory, and, ultimately, social salvation. Hopefully, with this film, the world will listen to the melody of her life with new ears.

The Rev. Nicole Duncan-Smith is a journalist, hip-hop enthusiast, wife, mom, preacher, and all-around cool kid.

Essay

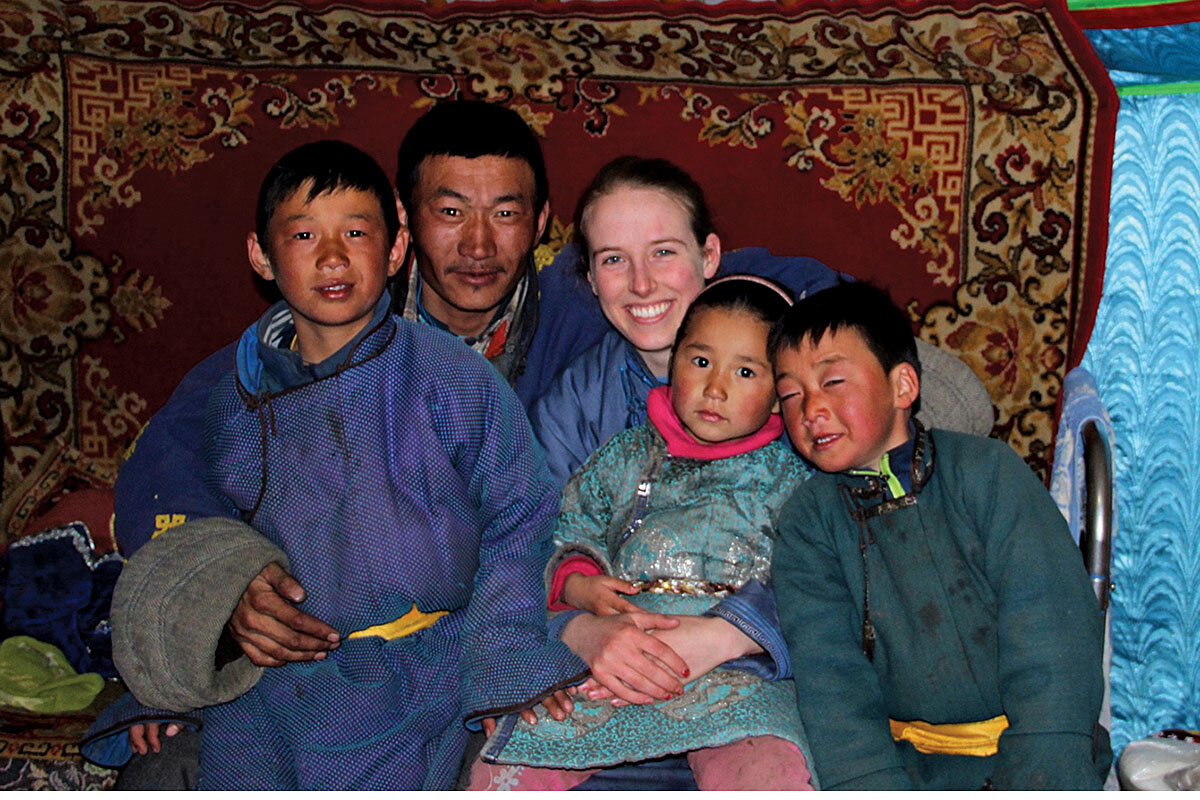

Kindness linked us on the Mongolian steppe

On a homestay with a family of nomadic herders, our essayist discovers that, when shared language is limited, caring and kindness communicate more deeply.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lucy Page Correspondent

My semester abroad in Mongolia included two weeks with a family of nomadic herders on the frozen steppe. Each morning, I’d trail behind my host mom, leading yaks to water. In the evenings, we clustered in the warmth of the ger to play cards or watch Mongolian music videos with my host parents and their two young sons and daughter.

I was studying Mongolian, but there was so much I couldn’t say or understand. We relied instead on short phrases and eager charades. This verbal obstacle was oddly freeing. In the crowded dining hall at home, meeting new people made me anxious. I’d stay quiet, measuring out my words. Here, I couldn’t fine-tune my speech. I could only smile and try out one of the phrases I’d mastered: “May I help?” “Where is the dog?” “Are you tired?” My host family guffawed at my pronunciation, but in their laughter, I felt safe, unembarrassed, at ease.

We were so different, they and I. Without shared social yardsticks, I wasted no time wondering how I was measuring up. Only real things – kindness, helpfulness – mattered.

Kindness linked us on the Mongolian steppe

I didn’t know quite what I was looking for when I flew to Mongolia for a semester abroad. I just needed something different, far from the late-night libraries of my college town. Most different, I hoped, would be my rural homestay: two weeks in central Mongolia with a family of nomadic herders.

My host family’s ger, a round white tent that Mongolians have carried across the steppe for centuries, nestled against the base of a rock outcropping. From the top of the rocks the steppe rolled to the horizon, a vast sheet striped with windblown snow. It was late March.

Each morning, my host mom cinched the sash of my Mongolian robe snug around my waist. Then I’d trail behind her, calling “shoo, shoo, shoo” to guide our yaks over moss-covered boulders. We’d smash rocks through ice to draw water from a nearby stream and collect dried dung in nylon sacks for fuel.

In the evenings, we clustered in the warmth of the ger. It was just tall enough for me to stand up in, with two beds crowding an iron stove in the center, a set of shelves holding bent silverware and faded dishcloths, and a painted altar where photos of my host grandparents were propped next to Buddhist icons. We’d squeeze onto wooden footstools around the altar to play cards or watch Mongolian music videos on the solar-powered TV, while my host mom diced mutton for dumplings. I’d lose at Connect Four to my host brothers, Dalai and Dawaana, and make faces at my host sister, Lhamsuren, who straddled my lap and kneaded my cheeks like dough.

I was studying Mongolian at the time, but still, there was so much I couldn’t say or understand. We relied instead on short phrases and eager charades. As we tramped through snow behind the goats, my host mom, Tuvshintogoh, would ask me if I was cold, then giggle and pantomime a big shiver to make sure I understood. In the evenings, she showed me how to fold dumplings with exaggerated pinches and twists of her fingers. My host siblings would chatter at me, speaking too fast for me to understand, as we explored the boulders around our ger; I’d listen and nod and then, suddenly, swing them off their feet by the armpits.

This verbal obstacle was oddly freeing. In the crowded dining hall at home, meeting new people made me anxious. I’d stay quiet, measuring out my words, scrambling for something to say that wouldn’t expose me as unfunny, weird, boring. In Mongolia, I couldn’t fine-tune my words. I could only smile, hold Lhamsuren’s hand, and try out one of the phrases I’d mastered: “May I help?” “Where is the dog?” “Are you tired?” My host family guffawed at my pronunciation, at the way I threw up my hands and eyebrows in a frequent gesture of confusion. But in their laughter, I felt safe, unembarrassed.

With my Mongolian family on the steppe, I found an ease I’d never felt before. The static in my head quieted. My fear of being judged – so long my nagging companion – began to wane.

We were so different, they and I, and not just in language. Their skin was hardened and darkened by sun; I’d been hidden under hats and sunscreen since birth. My host siblings grew up drawing water from frozen streams and jogging behind herds of sheep; I wiled away summers at tennis camp.

For me, these gaps made all the difference. Without shared social yardsticks, I wasted no time wondering how I was measuring up. Only real things – kindness, helpfulness – mattered. We were simply six humans, tiny against a vast Mongolian sky.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A welcoming that defines power in the Middle East

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

During a visit to Iraq this weekend, Pope Francis will meet with the most respected imam of Shiite Muslims, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. Their meeting is more than a historic first or a symbol of reconciliation. In a Middle East torn by violence among the offshoots of the three monotheistic Abrahamic faiths, it may help redefine power in the region.

Many of the Mideast’s conflicts are driven by hate among Muslims, Christians, and Jews. By meeting as equals, the pope and grand ayatollah hope to reverse that. Their recognition of each other is an act of humility, a respecting of human differences while honoring each other as made in God’s image.

“The central insight of monotheism – that God is the parent of humanity, then we are all members of a single human family – has become more real in its implication than ever before,” wrote Jonathan Sacks, the former chief rabbi of Britain, in one of his last books, “Not In God’s Name,” before his death last November.

These religions, he insisted, gain power by not accepting a dualism that claims a conflict between two realities, good and evil, rather than the one reality of good.

A welcoming that defines power in the Middle East

During a visit to Iraq this weekend, Pope Francis will meet one-on-one with the most respected imam of Shiite Muslims, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. Their meeting in the sacred city of Najaf – no doubt one of affection between two learned men who preach peace – is more than a historic first or a symbol of reconciliation. In a Middle East torn by violence among the offshoots of the three monotheistic Abrahamic faiths, it may help redefine power in the region.

Many of the Mideast’s conflicts are driven by hate – among Muslims, Christians, and Jews, and often within a faith, such as between Islam’s minority Shiites and majority Sunnis. By meeting as equals, the pope and grand ayatollah hope to reverse that. Their recognition of each other is an act of humility, a respecting of human differences while honoring each other as made in God’s image.

Grand Ayatollah Sistani is already well known for his calls to protect Iraqi Christians from terrorists and for them to be treated as equals. For his part, Pope Francis described his reason for the visit: “I come as a pilgrim, a penitent pilgrim to implore forgiveness and reconciliation from the Lord after years of war and terrorism.” In a subtle message to their followers, the meeting signals that each sees God (or Allah) in the other rather than insisting on a divinity in their own image.

That is the power in Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. “The central insight of monotheism – that God is the parent of humanity, then we are all members of a single human family – has become more real in its implication than ever before,” wrote Jonathan Sacks, the former chief rabbi of Britain, in one of his last books, “Not In God’s Name,” before his death last November.

These religions, he insisted, gain power by not accepting a dualism that claims a conflict between two realities, good and evil, rather than the one reality of good. That dualism “divides humanity into the unshakeably good and the irredeemably evil, giving rise to a long history of bloodshed and barbarism of the kind we see being enacted today,” he writes.

Until all human institutions take a stand against hate and the great religions base their power on love, all efforts of diplomacy and military intervention will fail, he said. Mr. Sacks also points out that the parent of the three faiths, Abraham, had no military. He welcomed strangers into his tent with blessings in the same way that the grand ayatollah and the pope are meeting.

The pope’s visit will include another meaningful moment. On Saturday, he will join an interfaith ceremony in the ancient city of Ur, the presumed birthplace of Abraham. History for the three faiths will come back to its origins of unity for all humanity.

“The meeting between the pope and Ayatollah Sistani would represent a very, very profound statement about moderation in religion,” says Iraqi President Barham Salih. The pope’s visit, he adds, is based on its potential to “heal” divisions between faiths. That power for healing will be seen in the shared welcome and appreciation between two men in a simple home in Najaf.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

All-presence

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Peter J. Henniker-Heaton

Wherever we may be, and whatever issues we may face, divine Love is present to guide, help, and heal, as this poem conveys.

All-presence

We cannot turn away from God

because, whichever way we face,

Spirit is there. In every place,

every direction, everywhere,

Spirit is there.Whether we turn to left or right,

to north or south or east or west,

we meet with Love – and we are blessed.

Upward or down, below, above,

we meet with Love.Whether we plunge to ocean trench

or plot our course for farthest space,

Love’s law controls. Whatever race

we enter toward whatever goals,

Love’s law controls.Whether we build for centuries hence

or let tomorrow bound our aim,

God sets the pace. Always the same,

with instant and eternal grace,

God sets the pace.Originally published in the Nov. 18, 1972, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel, this poem also appears as a hymn in the “Christian Science Hymnal: Hymns 430-603” (No. 591).

A message of love

Punching it up: Our photos of the week

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back Monday, when we’ll have a profile of attorney general nominee Merrick Garland.