- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Learning From Lockdown

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

What will education look like in another year? Another five years?

If it seems too soon to be asking, consider this: The Colorado district I live in announced this week that instead of closing for a snow day following a blizzardy weekend, students would work remotely.

While not everyone with a sled and mittens might agree with that approach, it demonstrates the expanded thinking around the delivery of learning the past year has brought.

The Monitor has been exploring that new thinking with a group of journalists brought together and funded by the Solutions Journalism Network. Our reporting collaboration, “Learning From Lockdown,” debuts today and includes what we’re sharing in this Daily (on tutoring) and in tomorrow’s (on remote learning’s legacy).

Researchers and advocates see an immediate opportunity to think about what could change in education. Today’s story, for example, suggests that tutoring could not only get students back on track from pandemic learning loss, but also potentially make everyone a teacher or a learner. Understanding the link between knowledge acquisition and human interaction is essential to any forward-looking vision. As a former teacher, I can confirm that learning is strengthened by relationships.

“As we think about tutoring, it’s not just about accelerating academic performance,” says AJ Gutierrez, co-founder of Saga Education, a tutoring nonprofit featured in the story. “As a district, there is a lot of benefit from infusing schools and communities with human capital.”

Will that be achieved through online platforms? Or a national tutoring corps? Let’s see what a year brings.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In trip to China’s backyard, Biden team tests its ‘values’ policy

Talk of alliances and democratic values makes for inspiring rhetoric. But can the Biden administration’s new foreign policy stand up to the rigors of strategic competition with China?

The leaders of four countries that years ago provided disaster relief following the Indian Ocean tsunami met in a virtual summit Friday. President Joe Biden initiated the meeting of the United States, Japan, Australia, and India – now called the Quad – as a way to demonstrate a foreign policy of values focused on “addressing people’s needs at a very basic level,” as one senior administration official says.

The summit resulted in an ambitious plan to deliver 1 billion vaccines to Southeast Asia by the end of 2022. Other areas pegged for stepped-up cooperative action include climate change and infrastructure development.

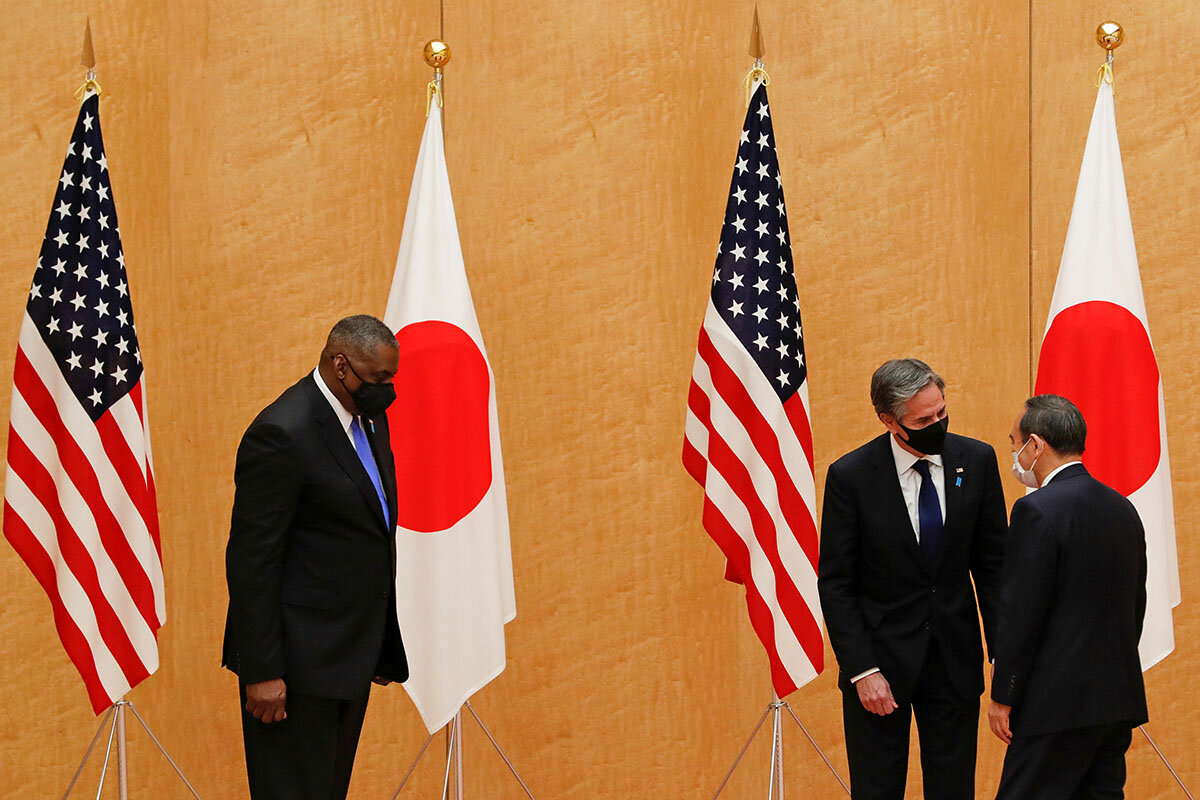

Now, by dispatching Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin together to Tokyo and Seoul this week, Mr. Biden aims to demonstrate that America’s alliances and cooperation with key democratic partners are back, aides say.

The trips also suggest the U.S. has some catching up to do in what is perhaps the 21st century’s most critical region.

“There was a clear recognition in the administration that the United States had lost ground in Asia ... and they needed to quickly build up a united front to deal with China,” says Michael Green at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

In trip to China’s backyard, Biden team tests its ‘values’ policy

When a catastrophic tsunami struck Indonesia’s Aceh Province in 2004, killing more than 200,000 people and uprooting hundreds of thousands more, the United States marshaled the forces of partners Japan, Australia, and India to launch one of the largest and most comprehensive disaster aid efforts ever undertaken.

The initiative saved lives and rebuilt communities across the affected Indian Ocean region. It demonstrated that alliances of nations could be as much about meeting human needs as about lofty hard-power defense strategies and big-power competition.

More broadly, it underscored that democracies working together from the basis of shared values offered a more comprehensive and equitable assistance and redevelopment model than the one proffered by an autocratic China.

In that sense, the U.S.-led assistance effort was an early stab at countering the regional ambitions of a rising China.

Now, as President Joe Biden launches his first major foreign policy initiative – focused on Asia’s Indo-Pacific region and aimed at countering an increasingly aggressive China – the Aceh relief effort is one of the administration’s guides, senior administration officials say.

By dispatching Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin together to Tokyo and Seoul this week, Mr. Biden aims to demonstrate that America’s alliances and cooperation with key democratic partners are back, aides say.

The trips also are recognition, some regional analysts say, that the U.S. has some catching up to do in what is perhaps the 21st century’s most critical region.

“There was a clear recognition in the administration that the United States had lost ground in Asia … and they needed to quickly build up a united front to deal with China on a range of issues,” says Michael Green, former National Security Council senior director for Asia under President George W. Bush and now senior vice president for Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington.

On Thursday, Mr. Blinken will carry with him the message from his meetings with democratic partners in the region when he meets in Anchorage, Alaska, with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

Moreover, the two top national security officials’ Asia trip follows a first-of-its-kind summit last Friday of the leaders of the four countries of the Aceh effort – now more formally organized as the Quad. Mr. Biden initiated the summit as a way to demonstrate a foreign policy of values that is focused on “addressing people’s needs at a very basic level,” as one senior administration official says.

The 90-minute, four-leader forum resulted in an ambitious coronavirus vaccination distribution plan marshaling each country’s strengths to deliver 1 billion vaccines to Southeast Asia by the end of 2022. Other areas pegged for stepped-up cooperative action include climate-change mitigation, infrastructure development, and access to rare-earth metals.

“We are united by our democratic values and our commitment to a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific,” Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi told his counterparts at the opening of the virtual summit. “Our agenda today – covering areas like vaccines, climate change, and emerging technologies – make the Quad a force for global good.”

Yet if Mr. Biden chose the Indo-Pacific region for the inaugural run of his “values-based” foreign policy, it was to underscore how offering an alternative to China’s vision for the region has only grown in importance in the nearly two decades since the Indian Ocean tsunami.

“Vaccine diplomacy”

Underscoring the stakes of the Biden administration’s foray into what China increasingly considers its backyard are the divergent approaches to “vaccine diplomacy” being pursued by the U.S.-led Quad countries on the one hand and by China on the other.

The differences between the two approaches could hardly be more stark.

China is well ahead in terms of regional COVID-19 vaccine distribution, but its approach has invited criticism over what many see as an aggressive and nationalist diplomacy that puts Chinese interests first. As one example, the Chinese government this week announced that it would begin admitting vaccinated foreigners at airports and other ports of entry – but only those foreigners carrying proof of having been administered a Chinese-produced vaccine.

On the other hand, the Quad countries’ vaccine initiative calls for tapping into each country’s strengths: harnessing India’s production capabilities in conjunction with U.S. biotech expertise, Japanese funding, and Australia’s logistics prowess.

In many ways, Mr. Biden’s Quad summit and the Blinken-Austin visits to Tokyo and Seoul are stage-setters for Secretary Blinken’s meetings with Foreign Minister Wang – chief diplomat of the country the secretary of state has in recent weeks described as America’s and indeed the “free” and liberal world’s chief rival and adversary. (After Seoul, Secretary Austin heads to New Delhi for discussions on enhancing military-to-military cooperation between the U.S. and India.)

Mr. Blinken’s expected message to Mr. Wang: This past week demonstrates not just that we are back in Asia, but that we intend to build a secure, prosperous, and free Indo-Pacific through our alliances and partnerships with democracies in the region.

Calling China in a speech last week the one country able “to seriously challenge the stable and open international system,” the chief U.S. diplomat said managing the U.S.-China relationship was likely to be the “biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century.”

Agenda of concerns

Senior administration officials said Tuesday that Mr. Blinken – who will be joined in the Anchorage meetings by President Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan – does not expect to make any major announcements after meeting Chinese officials. Instead, the talks aim to set the tone and lay out the agenda of concerns – from China’s economic coercion of U.S. allies and partners to provocative military activities and human rights – for a “broader strategic conversation” going forward.

“We think it’s really important that each side understands where the other side stands,” says one senior administration official.

For regional analysts, the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific week also is demonstrating that the U.S. intends to compete with China by building with regional partners a model that is better than China’s at meeting people’s aspirations for freedom and prosperity.

Mr. Green at CSIS says wrapping up the administration’s Asia week with meetings with senior Chinese officials “is a very smart play.” America’s Indo-Pacific partners and the Quad countries in particular “do not want the containment of China; they don’t want complete decoupling,” he says. “They want the U.S. to compete but be able to cooperate with China where it’s in our interests.”

Mr. Blinken is expected to sprinkle a tough stance in Anchorage with hopes for cooperating with Beijing on issues of mutual interest, including climate change, Afghanistan, and, Mr. Green adds, perhaps even Myanmar.

Shift to hard power?

The question now for some regional analysts is whether the U.S. sticks to a comprehensive, values-driven diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific, or if a sense of the growing urgency to confront China prompts a shift to more hard-power initiatives like stepped-up joint military exercises and inter-military cooperation.

“The rhetoric from the Quad summit was reassuring and the emphasis on promoting the public good, with the vaccine initiative and climate change and infrastructure investment, was a very positive development,” says Sarang Shidore, a senior fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks in Washington.

“But China is the deeper reason the Quad was even born,” he adds, “and what I find worrying is that despite the recent attention to the values of the group, which include peace and inclusion, the military aspect has not really been pulled back.”

Pointing to Secretary Austin’s stop in New Delhi, Mr. Shidore says he sees the risk of a regional policy based on values and mutual interests shifting increasingly to an emphasis on China’s “compellence and containment,” something he says America’s regional partners don’t want.

And he says it is the U.S., as the Indo-Pacific regional powers’ “most powerful and consequential” partner, that will determine which course the region follows.

As border crisis intensifies, so does pressure on Biden to fix it

Democrats criticized Donald Trump’s immigration approach as needlessly harsh. Now, amid a surge in asylum-seekers, the Biden administration is scrambling to come up with a practical alternative.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Washington has been trying for decades to fix the U.S. immigration system. Former President Donald Trump’s border security policies cut down on migrant flows but stirred controversy, particularly his policy of separating children from their parents.

Now, as the United States grapples with a growing surge of migrants – with nearly 100,000 detained last month, including 9,300 unaccompanied minors – President Joe Biden is coming under increasing pressure to demonstrate that he has a solution. Many of these minors have been kept in detention facilities beyond the legal limit of 72 hours, prompting conservatives to ask why Democrats are not again decrying “kids in cages.”

Democrats, who are putting forward related legislation this week, call for a multifaceted approach that includes working with leaders in Central America, rebuilding the Obama-era program in which minors can apply for family reunification, and creating an orderly, humane process on the U.S. side and a path to citizenship for those already here. But they agree the current situation is unsustainable.

“The bottom line is – and this is something about which we all agree – the immigration system is broken, and it is in need of legislative reform,” said Mr. Biden’s Homeland Security chief, Alejandro Mayorkas.

As border crisis intensifies, so does pressure on Biden to fix it

President Joe Biden is under increasing pressure to address a growing border crisis, as a surge in migrants tests his campaign promise for a comprehensive, humane approach to immigration. Amid criticism that his softer stance was to blame for the surge, Mr. Biden yesterday said plainly in an interview with ABC News, “Don’t come over.”

Last month, the United States detained nearly 100,000 migrants trying to cross into the country illegally – almost triple the total in February 2020, and more than in any other February since 2006. Among those were 9,300 unaccompanied minors. As the administration struggles to process them in a timely way during a pandemic, many have been kept in detention facilities beyond the legal limit of 72 hours, prompting conservatives to ask why Democrats are not again decrying “kids in cages” as they did during the Trump era.

Mexican officials have said that organized crime groups are taking advantage of President Biden’s more tolerant stance on immigration, developing “‘unprecedented’ levels of sophistication” to smuggle migrants into the U.S. and increasingly taking them on more dangerous routes. Some minors fall prey to child sex trafficking schemes. Drug trafficking also appears to be on the rise, with nearly twice as many pounds of drugs seized in February as the previous month. Not even halfway into this fiscal year, U.S. border authorities have already seized more fentanyl – a main driver of America’s opioid crisis – than in any of the three previous fiscal years.

Rep. Maria Salazar, a Miami Republican who visited the border with a GOP congressional delegation on March 15, called on her community to pressure their representatives to act. “We – the Hispanic Americans in this country – have a problem, and we need to be part of the solution. We need to join forces and send a message that we cannot allow what’s happening on the border,” she said, speaking from El Paso, Texas. “We need to stop being pawns of the politicians in Washington and pawns of the traffickers who are trafficking with our children, our families, and our women.”

Many Democrats agree that the situation is unsustainable, but say the challenge requires a multifaceted response. Rep. Veronica Escobar, a Democrat who represents El Paso in Congress, said she sent a letter last week to Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California, offering to help connect the GOP delegation with migrants and advocates in addition to their meetings with Border Patrol, but never got a response.

“They want photo ops, and they use communities like mine as a prop,” says Representative Escobar, who says she can see a statue in Ciudad Juárez from her home in El Paso, and who feels the border is amply secure. “Here’s what makes us insecure: when we treat every human being arriving at our front door like they are a national security threat or a criminal. It takes law enforcement’s eyes off of the real security threats.”

A McCarthy spokesperson responded by saying that given the high numbers of migrants attempting to cross the border, including several individuals on the terrorist watchlist, and the threat of detained migrants spreading COVID-19 within the United States, the immediate priority must be to secure the border. “This is why Leader McCarthy led a congressional delegation down to the border this week – he wanted to assess the situation firsthand, including having discussions with migrants held at the facility, to gather the information needed to stop this crisis,” the spokesperson said. “He is ready to work with the president, or any Democrat, who wants to prioritize the security of our country.”

A decadeslong policy challenge

Democrats and Republicans have been trying for decades to develop an immigration policy that combines compassion and security – which both sides say are not contradictory ideals, though it often appears that way in political discourse. How to welcome those with bona fide asylum claims while upholding the laws of the land and preserving border security is a monumental challenge, one that former President Donald Trump tackled with aggressive measures that significantly reduced the number of migrants attempting to cross into the U.S. but also stirred controversy. In particular, he was criticized for his policy of separating children from their parents upon arrival, hundreds of whom still have not been reunited.

President Biden, who immediately halted or reversed some of those measures upon taking office, says it will take time for his administration to unwind the snarls of Mr. Trump’s approach. He has exempted minors from Title 42, a policy that immediately expels migrants due to the pandemic. And he has called for a review of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), a Trump initiative that requires migrants who are denied entry to the U.S. (including asylum-seekers) to wait in Mexico until they can appear in a U.S. court. Mr. Biden also abruptly stopped congressionally funded work on nearly completed sections of the border wall, leaving gaps wide enough to drive vehicles through, and ended the so-called safe third-country agreements (STCAs) with Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, which were designed to require asylum-seekers to first seek asylum in those Northern Triangle countries before applying to the U.S. Only the Guatemala agreement was implemented, and it has been suspended since the start of the pandemic.

“The bottom line is – and this is something about which we all agree – the immigration system is broken, and it is in need of legislative reform,” Mr. Biden’s homeland security chief, Alejandro Mayorkas, said in a March 17 hearing before the House Homeland Security Committee. “The president presented a bill, and there are bills pending before the House,” he added. “I am confident and optimistic that we will actually begin once and for all to fix this system.”

Though the current level of apprehensions is still below a summer 2019 peak, Mr. Mayorkas said in a statement that the U.S. is “on pace to encounter more individuals on the southwest border than we have in the last 20 years.” And while most adults are immediately deported, minors are not. The number of unaccompanied minors who were detained along the border increased by 63% from January to February of this year.

As these minors crowd into makeshift detention centers, awaiting transfer to the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services for placement with a sponsor, Mr. Biden and his Democratic allies have come under increasing pressure to demonstrate that they have a better solution to the same problem for which they lambasted Mr. Trump.

“These are the kids in cages who many of our Democratic colleagues were so outraged about a few years ago,” said Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa on the Senate floor. “Curiously, we’re not seeing nearly as much outrage now.”

The prospects for comprehensive immigration reform in Congress – always difficult – appear particularly bleak now, with Democrats holding only a narrow margin in the House and a single tiebreaking vote in the Senate.

“The asylum claims are going through the roof. You’ve got to turn that off,” Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina told reporters on Capitol Hill this week, as the House prepared legislation that would offer a path to citizenship for children previously brought here illegally, known as “Dreamers,” and another bill that would give agricultural workers an opportunity to apply for legal status. “You’re not going to get a bill on legalizing immigrants until you stop the flow.” Otherwise, he said, such a bill would act as an incentive for more to come.

Sen. Bob Menendez, a New Jersey Democrat and co-sponsor of a bill that would provide a path to citizenship for America’s 11 million unauthorized immigrants – a proposal Senator Graham called a “nonstarter” unless twinned with border security provisions – told reporters that there’s a constant effort to build a bipartisan coalition on the issue. But he added that Democrats are also looking at using the budget reconciliation process to fast-track some if not all of their immigration initiatives, which would bypass the need for getting 60 votes.

What’s compassionate?

Most Democrats advocate for greater compassion for those fleeing poverty, gang violence, and corruption, which are rampant in the three Northern Triangle countries that have accounted for much of the illegal immigration to the U.S. in recent years. Former President Trump cut U.S. aid to these countries, which Democrats say exacerbated the problem, and also stopped a family reunification program that allowed minors to apply from their home country to join a parent in the U.S.

Republicans, for their part, tend to focus on the need to enforce U.S. law, for reasons of both ethics and safety. Allowing migrants to cross into and remain in the U.S. illegally simply incentivizes others to follow suit and undermines U.S. security, they say.

“If you let them in, more will come,” says Sen. Tom Cotton, an Arkansas Republican, calling the current situation on the border “a catastrophe.”

Many Republicans also push back on the criticism that they have no heart when it comes to foreigners seeking to flee desperate circumstances in their home countries. “It’s not compassionate to allow the illegal immigrants to cut in front of the line of millions of people around the world who are attempting to do it the right way – millions of people around the world that have valid asylum claims, that are being persecuted for their religion, for their gender, for their political beliefs, for their speech,” says Rep. Dan Crenshaw, a Texas Republican.

Fellow Texas Republican Sen. John Cornyn adds that allowing illegal immigration often exposes vulnerable migrants to dangerous situations. “Many of them die in the process [of trying to come to the U.S.]. Parents turn their children over to criminal organizations that treat them as a commodity,” he says. “So I would disagree vehemently that illegal immigration is compassionate. Legal immigration is compassionate.”

In a February executive order, President Biden laid out his own vision for achieving both compassion and security.

“Securing our borders does not require us to ignore the humanity of those who seek to cross them. The opposite is true,” he said. “We cannot solve the humanitarian crisis at our border without addressing the violence, instability, and lack of opportunity that compel so many people to flee their homes.”

Representative Escobar, the El Paso Democrat, says that will require working with leaders in the Northern Triangle, rebuilding the Obama-era program by which minors in those countries can apply for family reunification, and creating an orderly, humane process on the U.S. side.

“I believe that the Biden administration is going to be successful on all those fronts,” she says.

A deeper look

A tutoring revolution that could transform education

If tutoring is adopted broadly, some envision a world where school buildings will matter less in the future and everyone, young and old, can be both a teacher and a learner.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

As the United States and its schools enter the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers, educators, and families are struggling to address everything from learning loss among K-12 students to new pressures befalling the country’s nearly 7 million adult learners. Increasingly, they are narrowing in on an old, but potentially now groundbreaking, intervention: tutoring.

There is a bipartisan push for expanding tutoring in schools, whether through a new national “tutoring corps,” a constellation of innovative initiatives such as the free global platform schoolhouse.world, or some combination of both.

Tutoring can, advocates say, do far more than improve an individual’s test scores. It can create connections across age and place. It can build a global community and bridge socioeconomic divisions. Supporters say tutoring could not only aid pandemic recovery, but also fundamentally change the way we envision, and deliver, education. Everyone, regardless of age and background, could become both an instructor and student.

“We are having a moment of national enthusiasm about tutoring, motivated by the pandemic and the acute challenges it has presented for student learning,” says Matthew Kraft, an associate professor at Brown University. “But if we only see tutoring through the lens of COVID recovery, we will lose out on a fundamental opportunity.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network.

A tutoring revolution that could transform education

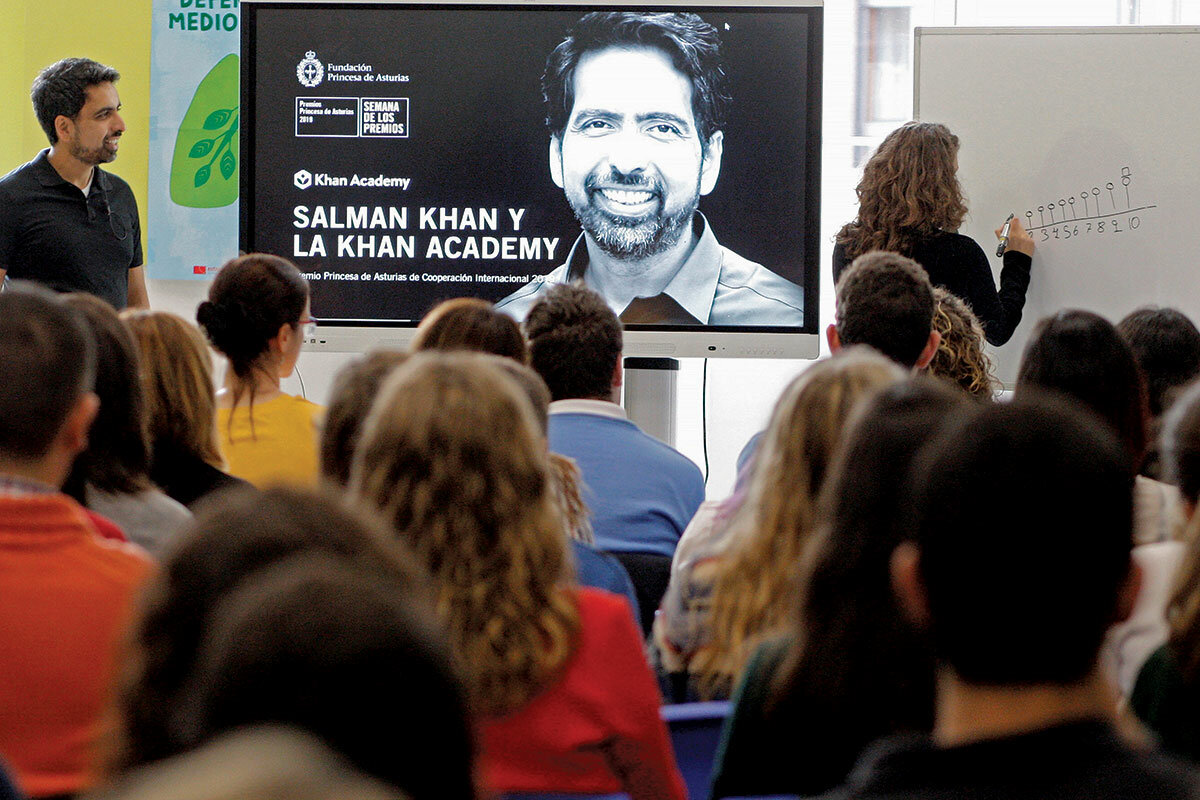

Raymond Jiang was scrolling through Instagram this past June – a way to pass time during a summer of no camps or social gatherings, after a high school freshman year that ended early – when he came across a post from education innovator Sal Khan.

For this 16-year-old son of Chinese immigrants living in the suburbs of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Mr. Khan was something of a rock star. Mr. Jiang had used Khan Academy, Mr. Khan’s nonprofit offering free online classes, to pass trigonometry and pre-calculus the summer prior. Now, he saw, Mr. Khan was looking for people to join his newest enterprise: schoolhouse.world, a free, global, online tutoring network.

Mr. Jiang loved calculus. He was thrilled by the idea of working with Mr. Khan himself. So he applied to be one of the organization’s first math teachers.

A few states away, Carl McGrone was also “driving around online just to have something to do,” as he puts it. A 52-year-old Mississippi native who works in a Waterloo, Iowa, pork processing plant, Mr. McGrone was studying to get his high school diploma when he came across Mr. Khan’s new venture.

Although he is not usually “a guy to get involved with something online,” Mr. McGrone signed up to be one of the first students with schoolhouse.world. He met Mr. Jiang in algebra class.

“Raymond – he took me to a whole new level,” Mr. McGrone says.

The teen just had a great way of explaining facts, he says. Mr. Jiang, for his part, says he bonded with the older man over their shared interest in wrestling.

“There are so many things I like about it,” says Mr. Jiang, who has tutored everyone from adults such as Mr. McGrone to teenagers worried about their grades. “It makes me feel good. I’m impacting someone’s life.”

As the United States and its schools enter the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers, educators, and families are struggling to address everything from learning loss among K-12 students to new pressures befalling the country’s nearly 7 million adult learners. Increasingly, they are narrowing in on an old, but potentially now groundbreaking, intervention: tutoring.

Research shows that tutoring can be hugely effective at closing academic achievement gaps. This has prompted a new, bipartisan push for expanding tutoring in schools, whether through a new national “tutoring corps,” a constellation of innovative initiatives such as schoolhouse.world, or some combination of both.

But as Mr. Jiang and Mr. McGrone are quick to attest, tutoring can do far more than improve an individual’s test scores. It can create connections across age and place. It can build a global community and bridge socioeconomic divisions. Indeed, supporters say that there is a chance in this moment to use tutoring not only for pandemic recovery, but also to fundamentally change the way we envision, and deliver, education. Implemented creatively and broadly, tutoring can create a world where grades and school buildings matter far less than they do now, and where everyone, young and old, can become both a teacher and a learner.

“We are having a moment of national enthusiasm about tutoring, motivated by the pandemic and the acute challenges it has presented for student learning,” says Matthew Kraft, an associate professor of education and economics at Brown University who has been at the forefront of the push for a national tutoring corps. “But if we only see tutoring through the lens of COVID recovery, we will lose out on a fundamental opportunity.”

A learning-loss fix

There is no clear consensus about how much learning children have lost from a year of remote and interrupted school. But some educational assessments have revealed substantial dips in both math and reading – and researchers worry that the impact is greater even than these tests show.

The nonprofit assessment group NWEA, for instance, found during its fall testing that children on average scored 5 to 10 percentile points lower in math than they did in 2019. But researchers also noticed that a large number of students hadn’t taken the assessment at all – and those who were absent were disproportionately low-income and students of color. In other words, those students most likely to be struggling anyhow were not taking the test, which meant that the results were likely skewed high.

“The biggest red flag for us is that the kids who are tested are not a representative sample,” says Karyn Lewis, a research scientist at NWEA.

Data released earlier this year from Ohio showed a similar pattern. There, a lower percentage of students scored above the state’s “proficient” level in reading than at any time in the past four years. Ohio has also reported a dramatic increase in chronic absenteeism, with nearly half of Black students recurringly out of school in sampled districts. This mirrors findings from the nonprofit Bellwether Education Partners, which estimated that 3 million students nationwide – mainly those most at-risk, such as children who are homeless – have stopped attending school altogether.

Although it is impossible to predict the long-term education impact of all this, statistical models show a clear connection between learning loss, absenteeism, lower college graduation rates, and a decline in lifetime earnings.

“We’re still really measuring it,” says Kristin Blagg, senior research associate at the Urban Institute’s Center on Education Data and Policy. “But it’s right to start thinking about interventions now, since the evidence we have is that there are gaps that are going to need to be mitigated.”

Tutoring is one way, researchers say, to effectively close those gaps. “We’ve done a review of research about summer school; we’ve used others to look at the outcomes of after-school programs and extended day – at adding time to the school day – all of which are the kinds of things people are talking about,” says Robert Slavin, director of the Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University. “All of these things, on average, produce positive results. But nothing compared to tutoring.”

When Dr. Slavin talks about tutoring, he means a particular kind of educational connection. He and others describe this as “high impact” or “high dosage” tutoring, where an instructor is matched with either one student or a small group of students, and where tutoring happens multiple times a week, integrated into the school day.

New research from the University of Chicago’s Education Lab found that Chicago public school students who received high-dosage math tutoring learned two to three times as much as their peers.

“It is one of the most positive results of any education innovation,” says Monica Bhatt, a senior research director with the Education Lab.

Politicians took note.

“As cities begin to rebuild from the pandemic, leaders across the country should act on these findings and make high-dosage tutoring a priority to support students,” said Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot in a press release.

Indeed, a number of educational experts and policymakers are calling for a national tutoring corps, which would leverage federal resources to get hundreds of thousands of new tutors inside schools. Using partners such as Saga Education, the nonprofit that ran the tutoring studied by the University of Chicago, and organizations such as AmeriCorps, which already has an infrastructure to connect young people with nonprofits doing the work, the government could dramatically improve education for students across the country, supporters say.

There is precedent for this sort of scaled-up initiative. Both England and the Netherlands have launched tutoring initiatives in hopes of counteracting the educational impact of the pandemic.

It is not only the K-12 students who would benefit from a national tutoring initiative, proponents say. Dr. Slavin, who has pushed for a national tutoring corps, says a federally funded initiative that dramatically expands tutoring programs could also help new college graduates, who are entering the workforce at a time of high unemployment.

“Part of the concerted effort here is to find good jobs for 100,000 people,” he says.

Neil Campbell, director of innovation for K-12 education policy at the Center for American Progress, says this sort of collaboration – evidence-backed tutoring plus a jobs initiative for college graduates – could end up bolstering the school workforce long term. “I would hope this would introduce thousands of young people to career opportunities in education,” he says.

There are also benefits for the tutors, says Jim Balfanz, chief executive officer of City Year, a nonprofit that partners with AmeriCorps to bring 3,000 young people into underserved school districts. These primarily 20-somethings, who come from a diversity of economic, religious, and racial backgrounds, quickly learn how to work together, for a cause bigger than themselves. And that, he argues, is profound.

“The idea of service as a shared experience, where you’re on a team working side by side with people from very different backgrounds, working for something larger than yourself – that creates an incredibly powerful developmental moment,” he says.

A national year of service could both close educational achievement gaps and enhance a sense of civic engagement. “It shows that being a citizen and being part of democracy is not just about your rights and participation in a political process, but participating as a citizen,” Dr. Balfanz says.

Concerns about scaling up

Dig into the talk about scaling up tutoring, though, and even supporters acknowledge that there is a worrisome background.

“I can think of very few interventions in the education sector that hold more promise,” says Dr. Kraft of Brown University. “That said, one of the truths of education reform and education research is that taking small-scale, effective programs and expanding them is universally difficult to do and often fails.”

Thinkers on the political right say this is reason to be skeptical about a large federal initiative. In an article for Education Next, Lisa Snell, director of K-12 education policy partnerships at the Charles Koch Institute, supported the idea of ramped-up tutoring in schools, but argued against a top-down tutoring “Marshall Plan.”

“A national, centralized tutoring program would create a slow response, where politics and process will stand in the way of students’ needs,” she wrote.

Many involved with today’s tutoring look back with concern at SES, the acronym for supplemental education services, a program that was part of the George W. Bush administration’s No Child Left Behind law.

Under that initiative, schools that failed to hit mandated achievement targets were required to offer students free tutoring programs. But there were few requirements for the tutoring groups that contracted with school districts.

“Every big company, every mom and pop company, people who had never done tutoring, they all came out of the woodwork,” Dr. Slavin recalls. Almost all offered their services during the summer or after school and struggled to keep students engaged. With profits tied to the number of students enrolled, some offered sign-up incentives like free iPods – only to see students collect a device and never return.

Few programs produced any meaningful academic gains, Dr. Slavin says. “The impact was near zero,” he says.

This is why both the type and the implementation of tutoring are going to be key, supporters say. And it is why David Hersh, the director of Proving Ground, an educational laboratory launched in 2015 that is connected to Harvard University, says that improving academic outcomes is going to have to be about more than just tutoring.

“Let’s say we knew that tutoring was the best hope in the world,” says Dr. Hersh. “We’d still need to get that tutoring model, that effective thing, into the hands of educators who needed it. They would need to identify the students [who would benefit from it]. It would need to be set up well to make sure that it could be implemented the way it was designed. And implementation is a huge, huge challenge in education.”

The focus of Proving Ground is to help with this step. It creates new processes for schools to test and make improvements, right down to the particular message that goes out to parents whose children have missed too many school days. With quick prototyping and adjustment, it distributes lessons learned to key decision-makers and districts, helping schools shift away from the slow, bureaucratic processes that many see as a hindrance to educational reform.

“We’re trying to use the lens that the pandemic has created to motivate people to realize that much more fundamental change is required,” says Dr. Hersh.

In other words, it’s not just adding tutors – it’s changing the way schools try new things and even how they understand “academic achievement.” Mike Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and executive editor of Education Next, agrees.

“Yes, we need high-dosage tutoring, we need more learning time, we need expanded mental health for kids,” he says. “But if all schools do is to add those services on what they usually do, and what they usually do is mediocre – that’s not going to get us there.”

“This is an opportunity”

That is exactly how Angélica Infante-Green, Rhode Island’s commissioner of education, sees it.

“What we need to do is to think outside the box,” she says. “We’ve always known that there’s been this dirty little secret in education, that we had these inequalities. COVID pulled it out from under the rug. Now this is an opportunity to reinvent what education can look like.”

In her state, this has taken a number of different forms. Rhode Island ran a summer program for students for the first time in 2020. It opened an All Course Network of virtual and in-person classes to any student in the state. And it partnered with schoolhouse.world to connect Rhode Island students with online tutoring – and maybe even with Raymond Jiang or one day Carl McGrone, who says he wants to be a tutor himself in the future.

Ms. Infante-Green admits that she was a bit skeptical when she first heard about the online tutoring site, but agreed to have her 13-year-old son try it out.

“He met a few times a week with a tutor. I was amazed at the progress,” she says.

And that, she says, along with the state’s relationship with Khan Academy, convinced her that Rhode Island should at least give it a try.

“We have a tendency of doing things in these steps that take a long time,” she says. “That’s part of the educational bureaucracy. COVID has blown that out of the water. We know we need to do things differently.”

Drew Bent, chief operating officer of schoolhouse.world, says that more state partnerships are in the works. Already New Hampshire and Mississippi are actively using schoolhouse.world to get tutoring to its students; soon other education departments across the country will follow suit.

“Tutoring fits into everyone’s model,” Mr. Bent says. “No matter what you believe about education, tutoring plays a part.”

This, after all, is how Mr. Khan got involved in education in the first place. Khan Academy grew out of Mr. Khan’s experience tutoring his cousins while he was still working as a hedge fund analyst.

The number of people using Khan Academy’s online video lessons skyrocketed during the pandemic. And it became clear, Mr. Khan says, that access to real-time learning was missing for a lot of young people.

He decided to test out a platform that would let volunteer tutors offer free small-group tutoring to anyone in the world. Skeptics wondered where the tutors would come from. But that didn’t end up being a problem – they had a flood of people going through the schoolhouse.world certification process to teach, from retired physics professors to “really incredible 14-year-olds,” Mr. Khan says.

It turned out that many people enjoy teaching – people, he says, “who would have loved to go into teaching but got sucked into finance or technology or law.”

As schoolhouse.world expanded, it started building partnerships with urban school districts and charter school networks. The idea, Mr. Bent says, was that teachers whose students needed extra help could put in a request for tutoring, and within days, dozens of high-qualified tutors would be ready to log on and help.

“The tutors love this,” Mr. Khan says. “When they see, here’s an urban school district that needs our help, these software engineers and professors in England, they say, ‘I want to do that.’”

Meanwhile, for the students, “you’re sitting in Long Beach, or some inner city, and your tutor is in upstate New York? Where’s that? Or they’re in England? Cool. There’s just something fun about that.”

Schoolhouse.world is geared for students age 13 and up. Younger students, education experts say, often do better person to person.

But that’s why educational leaders such as AJ Gutierrez, co-founder of Saga Education, the tutoring nonprofit that saw tremendous success is Chicago Public Schools, see benefit in a diverse system of high-quality tutoring innovations. “As we think about tutoring, it’s not just about accelerating academic performance,” he says. “As a district, there is a lot of benefit from infusing schools and communities with human capital.”

Bringing hundreds of thousands of young people into schools, expanding learning communities to include professionals across the world, re-imagining the schoolhouse walls and even incorporating new technology, such as adaptive learning and artificial intelligence, into the tutoring process has the chance to fundamentally transform education, he says.

“The work that we have ahead of us is really figuring out how to incorporate this not as an add-on, but part and parcel of how education is delivered in the United States,” says Dr. Bhatt, the University of Chicago researcher.

Dr. Slavin agrees. “When everybody comes back to school ... there will be a sense of exhilaration, a ‘let’s get back to normal, let’s get back to what we used to do,’” he says. “That’s not going to do it. There have to be ways of using this tragedy to create something better than what would have happened without it.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reporting about responses to social problems.

‘That boy can see!’ How I found my way after losing my sight.

When our essay writer lost his sight, even his family doubted his ability to succeed. But he found within himself the grit, humility, and patience to prove them wrong.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

My aunt and uncle said it was too dangerous to go out on my own. I’d immigrated to the United States from Nigeria to live with my mother’s brother and his wife in Maryland in 2010, and one year after that, I lost my vision. I learned to get about with a cane and craved getting back on the highway of life.

I heard of a course at a public library on how to use a computer with screen-reading software. I needed the training, and I’d have to travel to the class on my own. My aunt and uncle reluctantly consented.

I learned to navigate unfamiliar spaces by using my imagination to create mental maps. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t lose my way many times. I’d have to swallow my pride to ask for help. Sometimes I’d go to bed feeling down. But my disdain for staying put was an overriding motivation. Since then, I’ve earned three academic degrees. I defied all the dire prognostications about my safety. Today, I’m a published journalist and audio producer.

Now, marveling at my progress, my uncle exclaims to my aunt, “That boy can see!”

‘That boy can see!’ How I found my way after losing my sight.

My aunt and uncle said it was much too dangerous for me to go out on my own. I’d immigrated to the United States from Nigeria to live with my mother’s brother and his wife in Maryland in 2010, and one year after that, I lost my vision. I had since learned to get about with a cane, and now I craved getting back on the highway of life, to pursue my dream of being a broadcaster.

No, they told me. I would get lost or robbed. What if I got hit by a car? I must stay in the house.

But I was dogged. I rejected their scenarios and suppositions. I believed I could regain my way if I lost it. I believed that even if I were robbed every day, it would get to the point where either I’d befriend my robbers or they would grow so tired of robbing me that they’d leave me alone. Either way, I would not be stopped. I told my aunt and uncle I would pay close attention, I would listen and be very careful when crossing streets. I believed I would succeed. I was determined to succeed. I nurtured my ardor. I looked for ways to put my resolve into action.

Then a neighbor told me that a public library in Washington, D.C., was offering a tuition-free course on how to use a computer with screen-reading software designed for blind and visually impaired people. This was an important opportunity for me, as I was not eligible for any government assistance with my rehabilitation. Here was my chance to kill two birds with one stone: I needed the training badly, and it would require me to commute to and from the library on my own. I could practice my getting-about skills on my way to learning critical adaptive technology. My aunt and uncle reluctantly consented.

But how would I chart my course? I knew that the American singer Ray Charles, who was also blind, got around on his own without a cane. If he could do it without a cane, I reasoned, surely I could do it with one. Ray’s secret was to count steps. But I couldn’t seem to do that the way he had. Instead I developed the power of my imagination, capturing the layout of places I visited and taking note of landmarks in my mind.

At first, I would consciously pause to impress the layout of a new space on my mind. The next time I visited that place, I’d conjure the mental map I’d drawn and use that in order to navigate. Today, I do this automatically, creating and memorizing my mental map as I encounter a new landscape. I do it without thinking. But that doesn’t mean I didn’t lose my way many times in the process of acquiring this skill. I’d have to ask a kind stranger to help me reorient myself. I’d have to swallow my pride to ask for help, and reaffirm that it does not matter what others think or say about me.

Still, whenever I lost my way and had to ask for help, it would wear on my pride, my self-esteem. I’d be tempted to entertain doubts. Could I truly succeed in getting around on my own?

Sometimes I’d be so discouraged that I’d contemplate giving up. Perhaps my uncle was right, I’d think. Maybe I should stay home and wait until someone could help me. On those days when I lost my way, I’d go to bed feeling down. And because I didn’t want my uncle to worry about me, I kept that to myself – including the time I had to walk home on my own late at night because the buses had stopped running. But my disdain for staying put and spinning my wheels, and even more so my desire to beat blindness and bounce back, were overriding motivations. That determination was usually enough to get me out of bed the next day and try again. Along the way I learned to be patient with myself and to recognize that asking for help does not diminish me in any way.

Since that time, I’ve pursued my education. I’ve earned three academic degrees, including a master’s, in face-to-face classrooms. That meant catching buses and trains to and from my home or dormitory. I defied all the dire prognostications about my safety and well-being. Today, I’m a published journalist and audio producer.

Yes, I’ve lost my way at times – and found it again. Yes, I have come close to being hit by a car more times than I’m eager to say – and never been hit by one. And when people ask me, “Aren’t you afraid to be out on your own?” the answer to me is clear: I’d rather flirt with danger and find happiness than cling to safety and be miserable.

Now, marveling at my progress, my uncle exclaims to my aunt, “That boy can see!”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A prize for humble architecture

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

By habit of their profession, most architects want to be famous for designing grand cultural icons. Yet given the winners of this year’s Pritzker Prize – considered the Nobel of architecture – the profession might be ready for a different blueprint, one that starts with humility.

The 2021 winners are Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, a team in France whose work, according to the Pritzker jury, is a “demonstration of strength in modesty.” They are well known for offering an alternative to a government plan to demolish an apartment block in Bordeaux. After talking to the residents, they instead were able to extend the size of each apartment, adding a covered balcony with a winter garden.

What impressed the Pritzker jury was the couple’s refusal to believe there can be any opposition between “architectural quality, environmental responsibility, and the quest for an ethical society.”

Their architecture has “democratic spirit” and is “as transparent in its aesthetic as in its ethics,” cites the Pritzker Prize.

Mr. Vassal puts it more humbly: “We don’t know what the final result will look like and we’re not going to pretend that we do.”

A prize for humble architecture

By habit of their profession, most architects want to be famous for designing grand cultural icons. Think of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Fallingwater” home or Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Spain. Yet given the winners of this year’s Pritzker Prize – considered the “Nobel” of architecture – the profession might be ready for a different blueprint, one that starts with humility.

The 2021 winners are Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, a team in France whose work, according to the Pritzker jury, is a “demonstration of strength in modesty.” An extreme example of their work was the couple’s response to a request for a redesign of a public square in Bordeaux. Except for suggesting a coat of gravel, they said to leave the plaza alone. “Embellishment has no place here,” they wrote. “Quality, charm, life [already] exist.”

“If you take time to observe, and look very precisely, sometimes the answer is to do nothing,” Mr. Vassal told The Guardian.

Their modesty goes deeper than to decline a commission. They are well known for offering an alternative to a government plan to demolish a modernist 1960s apartment block in Bordeaux called Cité du Grand Parc. After talking to the residents, they instead were able to extend the size of each apartment, adding a covered balcony with a winter garden – without needing to move out the tenants during construction. And for less money and less pollution.

“There is almost never a completely lost situation!” said Ms. Lacaton, who says she first looks for the life already happening in a place.

They call their architecture the “no architecture.” But their rallying cry is really more restorative: “Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform, and reuse!” They built a home in Lège, for example, around an existing forest. Trees grow inside the house.

What impressed the Pritzker jury was the couple’s refusal to believe there can be any opposition between “architectural quality, environmental responsibility, and the quest for an ethical society.” Their work has adjusted the definition of architecture, the jury said.

The couple learned from time working in Niger on the edge of the Sahara, where they were forced to listen to residents and rely on local materials to design homes. “Economy … is a tool of freedom,” they said. And adds Ms. Lacaton, “You just have to ... look at things with a little love.”

Their architecture has “democratic spirit” and is “as transparent in its aesthetic as in its ethics,” cites the Pritzker Prize. Mr. Vassal puts it more humbly: “We don’t know what the final result will look like and we’re not going to pretend that we do.”

Winston Churchill once said, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” If architects follow the Lacaton-Vassal method, more buildings would be shaped – or sometimes simply reshaped – by the people who would actually use them. Architects wouldn’t so much lead as follow.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What you can do about racism

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Christian Kongolo

Recent events have made it clear that continued progress in healing racism is needed. How can we address issues like racism in a way that brings lasting change? In this interview, a Black man living in Oslo, Norway, shares how his ideas have evolved on this issue through prayer and experience.

What you can do about racism

Christian, tell us about where you were on some of these race-related issues even six months ago.

As just one example, I’d heard people talk about wanting more representation of Black people in movies. I didn’t see the need for it, to be honest. Growing up as a Christian Scientist, I’ve always been more likely to focus on things other than people’s appearance or skin color, because I learned in Christian Science Sunday School that our identity – our spiritual identity as God, good, created it – goes beyond these physical characteristics. That’s not to say diversity doesn’t matter; it does. It just wasn’t something I thought about all that much.

But recently, as there’s been much more discussion about subtle forms of racism and how they lead to this lack of representation and even exclusion, I got it on a much deeper level that we can’t gloss over the ways in which certain people have been marginalized and stereotyped – and worse – because of their skin color.

Have you ever experienced that in your own life?

In my job search, I was talking to various groups within the organizations where I was applying and quickly became aware that everyone was white. Even in my current job, I’m one of just a handful of Black employees. And it’s so unusual to see Black people working in the financial industry here in Oslo, that a white man explicitly expressed his astonishment when he found out that I was working in finance.

I’ve also noticed that there are certain stereotypes about Black people that I’ve had to confront – such as Black people aren’t competent, or aren’t the best people to be in my particular industry.

That definitely brought home the importance of representation, because I can see how having more diversity helps break down stereotypes. We aren’t just cleaners, musicians, and athletes.

Now that you’ve seen the need to deal with this issue more directly, how are you praying about it?

One of the things I find helpful to reflect on is an article by the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, titled “The Way,” in which she explains why self-knowledge, humility, and love are requisite for effective healing (see “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” pp. 355-359). I think the combination of all three qualities is so important, because I’ve encountered a lot of people who want to go straight to love. But that love, or really, what’s actually just the appearance of love, can end up glossing over everything that’s wrong without really dealing with it.

I think of it like this: If you have a bottle that’s filled with dirty water, you have to empty it first before you can fill it with pure water. And self-knowledge and humility are part of “emptying the bottle.” First we have to see that the water is impure. Then we have to acknowledge, in humility, that we’re not willing to put up with the impure water anymore. We want to dump it out – all of it. And then, once we’ve done that, we can fill it to the brim with that pure water – with love.

We don’t address racism simply by throwing love at people, because that doesn’t allow for seriously considering our own thoughts and hearts and how we might need changing. How we might have biases, or feelings of privilege, or places where we’ve gone wrong.

Where are the subtle places where ungodlike thoughts about our brothers and sisters might be lurking? Can we, in humility, acknowledge that we all have room to grow? Are we willing to let in more of the light of divine Truth to expose the dark thoughts that seem like our own, but ultimately don’t belong to us because they aren’t from God?

This kind of prayer allows us to love much more effectively, because then we’re doing what Jesus asked us to in one of his teachings: to take the beam out of our own eye – to deal with our own blind spots (see Luke 6:42). Then we aren’t held back by limited or ugly thinking that would prevent us from radiating that pure love from God that heals.

How has this prayer changed your conversations about racism?

Here in Norway, when the word “racism” comes up, I’ve heard people say things like, “What’s the point of talking about this, because it will only divide us?” I’m not saying we have to talk about racism all the time; our prayer of self-knowledge, humility, and love is really what should be constant. But when I hear things like that now, I recognize that that kind of thinking is what the Bible calls “Peace, peace; when there is no peace” (Jeremiah 6:14).

We can’t pretend that we’re all living in equality and everyone’s united when that’s not the case. If you’re cleaning the house, you don’t sweep dirt under the carpet, because then things are just as dirty as before – even if you can’t see it.

I think a healing of racism in our world begins as we have the difficult conversations within ourselves and with others. But it’s important to keep in mind that these conversations are not about being accusatory.

That’s what I love about Christian Science: It teaches us how to expose the things that aren’t right without attaching them to ourselves or others. We do have to take responsibility for the thoughts we’re allowing in. But ultimately, if those thoughts aren’t from God, they aren’t part of us, and we can be free of them. Everyone can be free of them. And then we begin to find the equality and unity that are real and lasting.

Originally published in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Sept. 16, 2020.

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article in the weekly Christian Science Sentinel on overcoming fear titled “Uprooting the seedlings of fear,” please click through to www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

From a drug zone to a garden

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. As you leave today, remember to check out the ”First Look” page on our website, where we post other news. One of today’s items is on shooting deaths in Atlanta that are raising new concerns about violence against Asian Americans.

And come back tomorrow, when we’ll have the next of our “Learning From Lockdown” offerings: a roundup of innovations from the past year that educators say are worth keeping.