- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Fresh start for Libya? Hopes ride on new wheeler-dealer leader.

- The pandemic’s remote learning legacy: A lot worth keeping

- Come one, come all: US broadens foreign policy partnerships

- How to avoid world war? Use your imagination.

- In Pictures: Meet the Muslim caretakers of Turkey’s Christian cave churches

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Right whale baby boom: Glimmer of hope for an endangered species

A new mother arrived in my neighborhood recently, creating a buzz.

Millipede and her 3-month-old baby right whale swam into Cape Cod Bay earlier this month. Her calf was born off the coast of Florida in December, and when spotted off Massachusetts her offspring “appeared to be quite healthy and independent,” said Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) researcher Brigid McKenna.

The mom and calf are part of a baby boom. The endangered North Atlantic right whale population is having its best calving season since 2012. So far, 18 newborn whales have been spotted. Only a total of 22 were born over the previous four years.

That’s significant because there are about 356 North Atlantic right whales left on this planet, and perhaps 100 are females. In the last century, the species was nearly hunted to extinction. Today, the most frequent cause of death is collisions with ships or getting tangled in fishing nets. Already, one of the 18 newborns has died after being struck by a sport fishing boat off Florida. Last week, a CCS Provincetown team managed to remove 300 feet of rope from a 16-year-old female in Cape Cod Bay.

Millipede (named for the pattern of scars left on her flank by a propeller) and her calf are “the hope for the future” of this species, said Dr. Charles Mayo of CCS. And by making the 1,200-mile journey from Florida, dodging ships and fishing nets, the pair have already shown a promising instinct for survival and resilience.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Fresh start for Libya? Hopes ride on new wheeler-dealer leader.

Hope for progress has been in short supply in Libya. But after years of devastating civil war, we look at why local and outside forces may now be ready to unify around a single leader.

Is Abdul Hamid Dabaiba the right person to lead a united Libya? The wheeler-dealer’s selection as interim prime minister was tarnished by corruption claims, and he once built grand construction projects for dictator Muammar Qaddafi.

Still, Libyans, wearied by years of turmoil, seem ready to embrace someone who can cut deals. To build support, the Toronto-educated billionaire played up his extensive international business ties to put at ease the foreign powers with forces in Libya – Turkey, Russia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates – enabling him to form a coalition everyone could agree to.

His initial priorities are many: get Libya’s banking system back online, overhaul the electric grid before the sweltering summer months, unify government institutions set up by two rival regimes over the past seven years, and tackle a surge of COVID-19 cases.

To some, his glad-handing style elicits concerns. “This is a government of appeasement rather than a government of national unity,” says Tarek Megerisi at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

But he adds: “If we can exit the year with one unified government, with some basic improvements in daily life, that is progress. ... We should take these wins when we see them.”

Fresh start for Libya? Hopes ride on new wheeler-dealer leader.

After seven years of civil war, Libyans have finally found a leader to head a united government and end their country’s chaos.

He is not a man of principle, standing above the fray. Rather he is a wheeler-dealer billionaire businessman, tarnished by corruption claims and past ties to ousted dictator Muammar Qaddafi.

Still, Libyans – wearied by years of turmoil – are cautiously putting their hopes in him.

They are ready today to embrace someone who can cut deals and begin to rebuild. And their amenable, glad-handing new prime minister is set to offer Libyans something they have not seen for much of the past decade: modest progress.

That would be welcome. Since 2014 Libya has been ruled by two rival governments at war with one another, each backed by foreign powers. Its oil wealth has been plundered, its infrastructure wrecked.

Yet now, with local factions and their foreign patrons deadlocked and exhausted, there is hope for a shaky, eight-month-old cease-fire and a United Nations-led process to restore a stable government and pave the way for peaceful elections by December.

Winning campaign

The fact that Libya swore in its first united government in seven years on Monday was largely down to the freshly minted interim prime minister himself, Abdul Hamid Dabaiba.

He was the dark horse of a vote last month by 73 U.N.-selected Libyan electors – a poll marred by widespread allegations of vote-buying.

Since then Mr. Dabaiba has built broad support for his new government by capitalizing on his experience and name recognition. He has played many roles in his long and colorful career: builder of grand development projects for President Qaddafi, a revolutionary and power broker from his hometown of Misurata during the 2011 uprising that unseated Mr. Qaddafi, and later a funder of the Libyan fight against the Islamic State.

The Toronto-educated billionaire also played up his international business dealings to put at ease the foreign powers with troops on Libyan soil – Turkey, Russia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates – enabling him to cobble together a broad coalition government everyone could agree to.

“What Dabaiba is trying to do is please a maximum number of actors, avoid conflict, and ensure a flow of money, projects, and positions to appeal to as broad a constellation as possible,” says Jalel Harchaoui, senior fellow at the Geneva-based Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

“Dabaiba is basically saying, ‘Let’s avoid war, do what you want in your designated territory, and let’s get things done’” along the way, Mr. Harchaoui adds.

Mr. Dabaiba’s first tasks are to get Libya’s banking system unified and back online and to overhaul the electric grid to offer Libyans full days of power ahead of the sweltering summer months.

He must also unify government institutions set up by the two rival regimes in the country’s east and west that have held power for the past seven years, and tackle a surge of COVID-19 cases.

By promising local governments a flurry of construction projects in their regions with little oversight, the incoming prime minister has placated players in the east and west.

But observers warn this will lead to a rush on Libya’s treasury, which has been starved of oil revenues for a year, and may further empower and entrench militias and factions as they dole out contracts, cash, and jobs to their constituents.

“This is a government of appeasement rather than a government of national unity,” says Tarek Megerisi, policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“It’s great that we have one government rather than two. Let’s keep moving forward. But it is also embedding the deeper drivers of conflict through nepotism and corruption.”

Foreign powers

Mr. Dabaiba’s emergence also provides deadlocked foreign powers that are eager to cut deals with a transactional prime minister who can work with every side.

Mr. Dabaiba has ties with influential businessmen in Cairo, has done business in Turkey for decades, and has had dealings in the past with both Russia and the UAE.

The incoming prime minister has promised to rid the country of 20,000 foreign mercenaries he decries as a “stab in the back of Libya.” That may not be easy.

For the past six years, foreign powers have used such mercenaries, along with local factions and rival governments, to pursue their agendas. Backing Gen. Khalifa Haftar’s breakaway Libyan National Army in the east have been Egypt, the UAE, and Russia. Turkey intervened to back the U.N.-recognized Government of National Accord in Tripoli.

The two sides’ forces are currently in a stalemate around the city of Sirte, in a central oil-producing region. A cease-fire has held for the past eight months among the four outside powers, who currently seem satisfied with what they have gained.

“There is an opportunity as Cairo, Ankara, and Moscow may see Dabaiba as someone who can bring the balance they have been looking for and secure each of their interests,” says Libyan analyst Mohamed Eljarh. “He is a potential bridge between the different sides.”

The Tripoli government granted Turkey concessions to explore for oil off Libya’s coast, and Russian mercenaries fighting with General Haftar’s army are stationed at oil fields in the east. That leaves Ankara and Moscow happy with the status quo and unlikely to withdraw their forces soon.

Meanwhile, the U.N. process has not addressed other explosive issues dividing the country, kicking them down the road until after elections: power sharing, local governance, and institutional reform.

The most contentious outstanding point is who retains control over a united army, an issue that has sparked two civil wars since Mr. Qaddafi’s fall. Mr. Dabaiba has finessed that question by reserving the defense minister’s post for himself.

U.S. hope

Libyan observers say the United States could play a major role in supporting the unity government as it seeks to rebuild the country and cement the cease-fire into a durable peace.

Many believe that Washington could use its influence over NATO member Turkey, the UAE, and Egypt to dissuade them from destabilizing the country when the political process is so fragile.

“The U.S. is the only actor that has the clout, the capability, to rein in the influence of foreign actors to bring them to heel,” says Anas El Gomati, director of the Tripoli-based Sadeq Institute.

Hailing the Libyan government formation as “a welcome step,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken called on “foreign powers to leave now.”

Other observers are less ambitious. “If we can exit the year with one unified government, with some basic improvements in daily life, that is progress,” says Mr. Megerisi, the analyst.

“Although it is faced with so many flaws, this government represents a new opportunity,” he adds. “We should take these wins when we see them.”

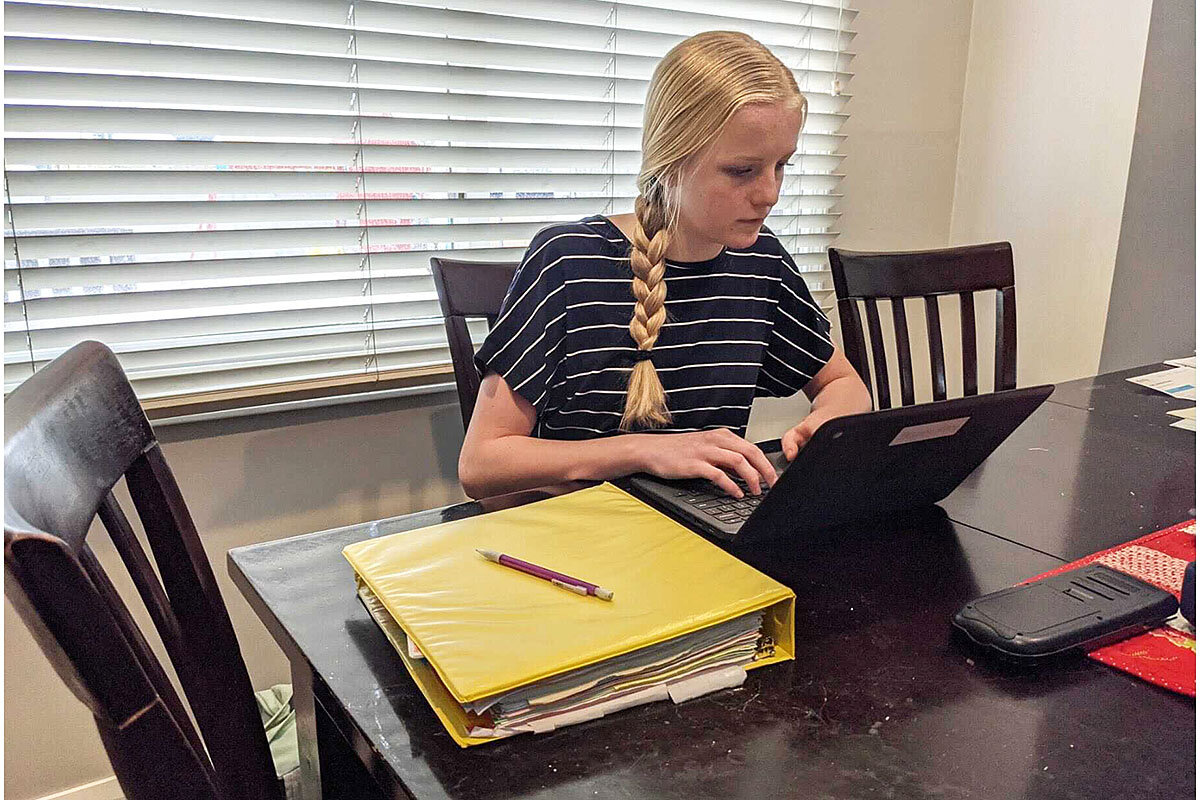

The pandemic’s remote learning legacy: A lot worth keeping

The pandemic has often spurred innovation, accelerated efforts to close digital gaps, fostered better communication, and opened new ways to address stubborn problems of school quality and equity. This story is part of the “Learning From Lockdown“ collaborative project.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

While the end of the pandemic is likely still months off, the White House has called for most K-8 schools to reopen by May, with in-person instruction at least one day a week, prolonging the possibility of distance learning.

Though virtual challenges remain – like teacher burnout and learning loss – some districts are pinpointing remote practices worth keeping. Sifting out solutions from the struggle may help solve chronic problems of quality and equity, say education experts.

“After a moment of disruption – of major disruption – the conditions are ripe for accelerating innovation,” says Richard Culatta, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education. “We are in that moment now in education.”

Hints of a remote learning legacy are emerging. The digital pivot made some districts solve preexisting tech gaps. Educators explored new social-emotional supports with heightened attention to mental health. And parents have transformed into stronger collaborators in their children’s learning.

The pandemic’s remote learning legacy: A lot worth keeping

As districts across the United States consider how to get student learning back on track and fortify parent interest in public schools, they’re asking the same question as Steve Joel: What should we keep after the pandemic?

The superintendent in Lincoln, Nebraska, says a district survey this past fall found that 10% of parents liked remote learning – pandemic or not. Nationally, nearly a third of parents say they are likely to choose virtual instruction indefinitely for their children, according to a February NPR/Ipsos poll.

While the end of the pandemic is likely still months off, the White House has called for most K-8 schools to reopen by May, with in-person instruction at least one day a week, prolonging the possibility of distance learning.

Though virtual challenges remain – like teacher burnout and learning loss – some districts are pinpointing remote practices worth keeping. Sifting out solutions from the struggle may help solve chronic problems of quality and equity, say education experts.

“After a moment of disruption – of major disruption – the conditions are ripe for accelerating innovation,” says Richard Culatta, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education. “We are in that moment now in education.”

Hints of a remote learning legacy are emerging. The digital pivot made some districts solve preexisting tech gaps. Educators explored new social-emotional supports with heightened attention to mental health. And parents have transformed into stronger collaborators in their children’s learning.

Leveraging such changes long term could be a matter of public school survival. Dr. Joel says his district, where a majority of K-12 learners are in person, is experiencing its first school-year enrollment decline in two decades.

“We really don’t want to do remote learning as a stand-alone [option],” says Dr. Joel, who has concerns about the instruction quality of remote learning. “But we don’t have any choice,” he adds, noting that because some parents like remote learning, they might seek alternatives to the district.

To navigate tough choices ahead, he joins district leaders nationwide analyzing what has worked.

Unexpected gains in equity

One school district in New York state is making inroads into inequities through a new notion of discipline. Remote learning has changed the approach to out-of-school suspension at Shenendehowa Central School District, where more than a fourth of students identify as nonwhite.

Grades K-5 in the district are in person, but middle and high schools are mostly hybrid. With the ability to log into lessons online, students at the secondary level won’t have to miss instruction even if they’re suspended, says Superintendent L. Oliver Robinson. It’s one way pandemic adjustments can address discipline inequities long-term.

During the 2015-16 school year, Black students in the district faced out-of-school suspension at 3.4 times the rate of white students, according to an analysis of federal data by the New York Civil Liberties Union. The disparity was slightly steeper on average (3.9 times) for districts across the New York Capital Region.

Before, out-of-school suspension risked academic setback for students, says Dr. Robinson, since it was sometimes logistically difficult to arrange tutors. Now with virtual options, suspended students can continue learning alongside their class. Though discipline issues declined during the pandemic, suspension remains a deterrent because too many infractions threaten student graduation.

“[Racial] disproportionality in things like suspension is real,” Dr. Robinson says. “Until that is completely addressed, the impact of the disproportionality can be significantly minimized or mitigated.”

While students ultimately may go back to in-person learning, remote learning will remain a possibility for suspended students “whenever feasible,” he says.

The pandemic also made it clearer that students can connect to coursework offered beyond their buildings. To soften the blow of class cancellations, Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) collaborated with dual enrollment partners to offer high schoolers online college-credit classes last summer. Flexible Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding meant the college could offer the program tuition-free.

JumpStart was a way to “give back” to students potentially impacted by learning loss and prepare them for college in the fall, says NOVA’s dual enrollment director Amy Nearman. Nearly 3,000 students enrolled, mostly graduating seniors.

The college benefited, too. JumpStart provided a pipeline to NOVA as more than a third of students enrolled in the fall (while community college enrollment fell by around 10% at the start of the school year compared with 2019, NOVA enrollment increased by 2%). The program also bolstered access to learning opportunities at times limited by availability and affordability. With JumpStart, says Ms. Nearman, “all of our students could have the same access to programming and not have to worry about, well, my parents can’t afford it.”

Federal funds help narrow the digital divide

Millions of students still face access issues. But between the start of the pandemic and December 2020, up to 12% of K-12 public school students gained internet connectivity who lacked it previously, and a similar share of students got access to digital devices, estimates Titilayo Tinubu Ali, senior director of research and policy at the Southern Education Foundation.

“We’re really excited” about districts taking this seriously, says Ms. Ali, co-author of a report on the tech gap. “The benefits of digital equity go far beyond education. ... They have an implication for how students and their parents’ quality of life will be.”

The researchers found that most of these solutions are short term, however, and will require more funding.

In Utah, the Murray City School District had been slowly developing a broadband network for students for two years when funding from the CARES Act helped the district speed up the rollout. In January, the district activated stronger radio towers that have allowed around 90 students in primarily low-income areas to log on. The district hopes to expand access to all 6,000 students by mid-April.

Now, though five of Jeannette Bowen’s children are back at Murray schools in person, the whole crew can log in simultaneously to the district network to do homework without disrupting their household internet. And the district network is useful when a child needs to stay home from school.

“It’s a reassurance as a parent to know they can get on and they can learn just like their peers in person,” says Ms. Bowen.

“This will be part of our Murray culture now,” says Superintendent Jennifer Covington.

There’s nothing new about trying to equip students with tech devices, but the pandemic spur to prioritize, fund, and accelerate that process will help students for years to come – especially as districts maintain online offerings. One in 5 school systems report that they have already adopted a fully virtual school option, or are considering adopting this in the future, according to the Rand Corp.

Educators in the suburban Chicago North Shore School District 112 retooled after determining that many of the available tech devices weren’t good enough to handle constant use during distance learning, says Superintendent Michael Lubelfeld.

“This was a real awakening,” he says. “We were trying hard, but there were some things that just didn’t work.”

The district put $1.6 million toward new iPads for every student in K-5 and all staff pre-K-8. A standardized inventory shared by all learners “equalizes the playing field,” says Dr. Lubelfeld.

Heightened focus on communication

How schools communicate with parents and how they check on the well-being of students have improved.

Tweaks to services for students, for example, resulted from a more empathetic understanding of individual student needs, says Dr. Robinson in New York.

“The question became: How much do we really know our students?” he says.

Based on input from students and parents, educators in his district relaxed rigid deadlines and grades. And teachers were forced to develop more methodical lesson plans that allow both virtual and in-person students to keep up. In some cases, the slowed instruction enhanced student understanding, says Dr. Robinson.

Remote options give students better access to school services like tutoring – something that, by nature, was limited and complex in the past because parents had to schedule pickups and drop-offs, he says. Now, he adds, students have more control than ever over their “academic destiny.”

Offering virtual tutoring followed the district’s realization, he says, about “how much young people were hostages, if you will, to the availability of adults in their lives.”

This expanded sense of possibilities, says Dr. Robinson, could have benefited students even before the pandemic, and is likely to outlast it.

The pandemic has increased mental health awareness, says Dr. Lubelfeld in Illinois. His district began one-on-one check-ins between students and mental health professionals last summer over Zoom, as well as home visits as needed. He expects the practice to continue beyond the pandemic.

“Everybody needs a check-in. And if someone hasn’t been heard of in a day or two, we need to have a triage,” says Dr. Lubelfeld, whose district will transition from hybrid to full in-person learning next month.

That kind of change in mental health awareness is also happening educator by educator. In St. Louis, a seventh-grade language arts teacher adapted her own classroom check-ins.

Before the pandemic, Adia Turner asked her Long International Middle School students to place sticky notes with their name on a “mental health wall” within categories that spelled out different feelings. Sometimes the exercise prompted her to follow up with individual concerns.

With the shift to digital learning, she collects that data through private weekly Microsoft Forms – using memes to illustrate moods – and has expanded her questions to include what they’re grateful for. One student expressed thanks for the “clothes on my back and food in my house.”

Ms. Turner has kept up this “necessary part of our day” even though two of her three classes are back in school.

“The ones who do participate, you can tell they gain a lot from it just by how intentional and thoughtful their answers are,” she says.

Stronger parent-school partnerships

Virtual communication has offered an efficient replacement for in-school conferences, which were often derailed by parent work schedules and child care.

An online Parent Academy – a digital extension of an already-existing initiative – was launched in Georgia’s Clayton County Public Schools last spring. Supported by federal funds, it coaches parents on topics like constructive study routines, how to monitor student progress, and new vocabulary specific to the digital classroom. The frequent workshops also offer translation services for families whose first language isn’t English.

Parent involvement is “critical,” says Assistant Superintendent Ebony Lee. And the district, currently fully virtual, plans to continue the academy because of positive feedback from parents like Kimberly Brown-Mack, the mother of an 11th grade student.

The online option is “a lot better for most of us parents who are working,” says Ms. Brown-Mack, a student support specialist in another district. “It is vitally important that parents have access to being able to continue to do virtual workshops.”

New York City’s Success Academy, a public charter of 20,000 students studying virtually, has turned to Zoom for all parent meetings.

“We can much more easily gather parents, explain things, get their feedback when they’re unhappy or upset about something,” says CEO Eva Moskowitz, adding it has bolstered parent partnership.

Because all Success Academy students have school-issued laptops or tablets, that means all parents are equipped to attend remote meetings, which the charter operator plans to continue indefinitely.

“I wouldn’t want to go back to a world where we didn’t prioritize parental convenience,” says Dr. Moskowitz.

Sustaining lessons learned

Some learners thrive online, but sustaining the progress of all students has demanded flexibility from educators.

“I think we’ve learned how to more individualize and differentiate instruction,” says Dr. Joel in Nebraska. “I think we’ve always been good at that, but I think we became a lot better at it.”

That flexibility is emblematic of a spirit that Ms. Covington, in Utah, says must be embraced: “If we don’t come out of this pandemic learning new ways to do things, it will be our loss.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the honorific for Jennifer Covington. She is Ms. Covington.

Patterns

Come one, come all: US broadens foreign policy partnerships

One unusual test of collaboration: Can it be done by uniting with rivals or foes around a common problem? The U.S. is trying this approach in Afghanistan, and beyond.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When the United States invaded Afghanistan two decades ago, to overthrow the Taliban government, it did so on its own. But in today’s world, Washington can do much less on its own. And as the Biden administration negotiates a cease-fire and the departure of its last troops, it is seeking to involve an array of other players.

Call it the “diplomacy of strange bedfellows.” Washington is pulling in not only NATO allies but India, Pakistan, and Iran – Afghanistan’s neighbors – along with Turkey, China, and Russia. They all stand to gain from a peaceful transition to a power-sharing government in Kabul.

It’s an approach President Joe Biden is likely to adopt in other global flashpoints. In Syria, for example, ending the civil war will need input from Turkey, Iran, and Russia, the main players on that stage. And on the Iran nuclear issue, signatories to the 2015 deal included Russia and China.

The “strange bedfellows” policy is based on the idea that there are some international challenges on which cooperation even with rivals is possible. It is an approach that will likely prove especially relevant when it comes to curbing climate change.

Come one, come all: US broadens foreign policy partnerships

It’s an audacious idea that might be dubbed the “diplomacy of strange bedfellows.” And there is no guarantee it will work. But the Biden administration’s novel blueprint for ending the war in Afghanistan might provide a template for conflict resolution elsewhere too.

In a world where the United States can do less on its own than it once could, Washington is looking beyond its traditional allies and seeking to enlist some unlikely partners to help advance its foreign policy goals.

Much has changed in the world since U.S. troops overthrew the Taliban regime in Kabul 20 years ago. The United Nations is now weaker. China is enormously stronger and more assertive, rivaling the U.S. for influence. The rise of populist nationalism has turned many countries inward.

America itself embarked on a nationalistic retreat from international alliances and institutions under Donald Trump – a retreat President Joe Biden has vowed to reverse under the banner of “bringing America back.”

His Afghan initiative, though, is a sign of how different America’s global role is likely to be from the one it played two decades ago – probably less go it alone and more carefully calibrated. And Washington is almost certain to steer clear of other major military engagements unless faced with a clear national security challenge.

Former President Trump set May 1 as the deadline for a full withdrawal of the 2,500 U.S. troops remaining in Afghanistan. But a resurgence of violence has positioned the Taliban to reclaim power once the Americans leave.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is trying to negotiate a cease-fire, alongside a detailed power-sharing arrangement between the U.S.-backed government in Kabul and the Taliban, creating the conditions for the American troop withdrawal.

The key diplomatic departure, however, is this: The U.S. is seeking to involve an array of other players in the talks – not just NATO allies, but Afghanistan’s neighbors Pakistan, India, and Iran. Also Turkey, a NATO member that’s been at odds with Washington. Plus China, and even Russia, where a new round of talks on Afghan power-sharing got underway today.

Each of these countries has interests different from, or even opposed to, those of the Americans. None would shed tears over an inglorious U.S. retreat from Afghanistan.

But they don’t necessarily welcome the prospect of all-out civil war after a May 1 pullout. Each would stand to gain influence, and a sense of co-ownership, by taking part in the peace process envisaged by the Biden administration.

That, at least, is Washington’s hope, if tinged with the recognition that success is by no means certain.

And there are signs that a similar emphasis on team diplomacy, rather than the simple exercise of unilateral U.S. power, is guiding President Biden’s approach to other challenges.

The “strange bedfellows” approach may prove difficult to apply elsewhere. In Syria, for example, it’s true that a resolution of the brutal, decadelong war will require key regional players such as Turkey, Iran, and Russia. Yet the U.S., having decided against any major involvement in the conflict, lacks leverage in devising a diplomatic solution itself.

When it comes to curbing Iran’s nuclear program, Mr. Biden has already inherited a mixed bag of partners in the 2015 deal limiting Tehran’s nuclear ambitions, which was signed by Russia and China, along with Washington’s European allies. But Iran has made it clear that its price for accepting new constraints on its nuclear activity is one that only Washington can pay: an end to U.S. economic sanctions.

The new administration’s focus on collective action, however, is emerging as key to Mr. Biden’s main overall foreign policy goal, which is to act as a counterweight to the rising influence of China and rebuff Beijing’s argument that autocracy offers the world a more secure and prosperous political model than democracy.

Mr. Blinken made this explicit in an opinion piece this week, co-written with Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, ahead of their first overseas diplomatic mission since taking office. It’s a visit to Japan and South Korea to make common cause to ensure that the Indo-Pacific region – China’s neighborhood – is “free and open, anchored by respect for human rights, democracy and the rule of law.”

In Mr. Blinken’s words, such partnerships are necessary “force multipliers” of U.S. influence and, in the wider contest between autocracy and democracy, key to demonstrating that democracies “can deliver – for our people and for each other.”

And beyond its specific impact in Afghanistan or elsewhere, the “strange bedfellows” approach may prove equally important to another aspect of the Biden foreign policy vision – the idea that there are some challenges on which cooperation remains possible, and worth pursuing, even with rival states.

Nowhere is that more important than the issue on which concerted international action is essential, global warming. As the world prepares for a major summit on climate change in Glasgow, Scotland, later this year, Afghanistan could serve as a proving ground for a strategy Mr. Biden plans to adopt in the face of very different challenges.

#TeamUp

How to avoid world war? Use your imagination.

Going back to Athens and Sparta, history shows old and new powers often go to war. To break that cycle, two ex-military men encourage us to think more creatively in a geopolitical thriller about a U.S.-China conflict.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Jacqueline Adams Correspondent

Elliot Ackerman and Adm. James Stavridis – military officers and accomplished authors – teamed up to write the cautionary tale “2034: A Novel of the Next World War,” published earlier this month. They had three goals for the book: that it be character-driven, that it not be a “huge door-stopper,” and that the themes cover both America’s place in the world and the rise of India and China.

Yet despite the novel’s focus on China, Admiral Stavridis predicts that in 300 years, historians will be writing about two topics: not the rise of China, but the rise of India and the increasingly powerful role of women. Indeed, the most resilient character in the book is a woman, U.S. Navy Commodore Sarah Hunt.

If the authors had a piece of advice for the Pentagon and White House, they would urge more creative thinking. They note that Pearl Harbor, 9/11, the current pandemic, and 20 years of war in Afghanistan have all been called “failures of imagination.”

“We don’t put enough weight on thinking creatively about the future,” the admiral says. “In the novel, we reverse-engineered a war with China – how we got into war and how you could back out.”

How to avoid world war? Use your imagination.

Elliot Ackerman and Adm. James Stavridis have powerful crystal balls, the result of their extensive lived experiences in the U.S. military, academia, politics, and publishing. Who better to construct a cautionary tale of cyberwar, miscalculation, and terror? Published earlier this month, their “2034: A Novel of the Next World War” is billed as “a chillingly authentic geopolitical thriller” – and it is. The White House, Pentagon, and myriad foreign-policy think tanks should take note.

By way of background, Admiral Stavridis is a retired four-star admiral who served as the supreme allied commander of NATO. Mr. Ackerman is a former White House fellow and Marine, who served five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, for which he received a Silver Star, Bronze Star for Valor, and Purple Heart.

Their friendship became close in 2017, when Mr. Ackerman spent a semester as a writer-in-residence while the admiral was dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University. Admiral Stavridis has written 10 books, primarily about leadership and naval history. Mr. Ackerman has published five novels and a memoir. Their shared editor suggested they collaborate on a piece of cautionary fiction that was originally the admiral’s idea. When they started, they told me, they had three major goals for their novel: that it be character-driven, that it not be a “huge door-stopper,” and that the themes cover both America’s place in the world and the rise of India and China.

Both men are wiry and intense. You can sense their intelligence shimmering, like heat rising in the distance. They both seem to think and talk in well-organized, numbered points. It takes a Google search to realize that they are of different generations. Mr. Ackerman is just 40 and the admiral turned 66 in February.

Imagining national defense strategies

Neither man believes that American exceptionalism is an outdated concept, but they concede that the United States is at an inflection point and needs to evolve to hold its place in the world. The major domestic and international challenge facing America, they say, is political gridlock, the result of marked polarization. Neither believes that the U.S. can or should be the world’s policeman.

Yes, China has been ascendant as a global force over the last half-century. But they point out that the U.S. retains major advantages: its geography, protected by two vast oceans and benign neighbors; significant energy resources that make the country currently the world’s largest oil producer; tremendous creativity and technological innovation in Silicon Valley; and 45 of the top 50 research universities, by their count. “People still want to immigrate to the U.S.,” Admiral Stavridis says. “No one is emigrating to China or Russia.”

If the authors had a piece of advice for the Pentagon and White House, they would urge more creative thinking about the future. They note that Pearl Harbor, 9/11, the current pandemic, and 20 years of war in Afghanistan have all been called “failures of imagination.”

“We don’t put enough weight on thinking creatively about the future,” the admiral says. “In the novel, we reverse-engineered a war with China – how we got into war and how you could back out.” The authors would urge the White House to do some version of the same: to imagine war-game scenarios in which China has control of cyberspace; military assets in outer space, including highly advanced satellites; and deep hypersonic cruise missiles.

Race, gender, and the glass cliff

Despite the novel’s focus on China, Admiral Stravidis predicts that in 300 years, historians will be writing about two topics: not the rise of China, but the rise of India and the increasingly powerful role of women.

Even so, one question that seemed to stump the authors was about the glass cliff – the phenomenon in which female leaders are promoted into senior roles when men have failed. The new leaders are then expected to save the day. In response, Admiral Stavridis acknowledges that the most resilient character in the book was indeed a woman, U.S. Navy Commodore Sarah Hunt.

The admiral also admits that “2034” did not explore domestic or military racial issues but says, “The greater theme is how aspects of our national character come together.” Mr. Ackerman adds that the U.S. is “not a blood and soil country. We are unified around ideals. Sometimes we reach those ideals and sometimes we don’t. By 2034, we’ll still be striving. In some years, we’ll be doing better than others.”

“It ought to be a wake-up call”

Their book made me recall speeches and discussions at various think tanks over the last decade or so. I specifically recall former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger saying that his biggest fear was that overly tired American or Chinese sailors in the South China Sea might make a mistake and start a war. The premise of “2034” is based on just such a scenario. But the admiral says (somewhat huffily), “I don’t need Henry Kissinger. I was that exhausted sailor in the South China Sea!” And Mr. Ackerman adds that among his military colleagues, exhaustion is a result of “forever wars.” “The current officer class,” he says, “knows nothing but war.”

Regarding the book’s emphasis on cyberwar, I recalled hearing two analysts (one a former diplomat and one a retired computer hardware CEO) discount military cyberthreats and focus instead on corporate espionage by disgruntled employees as the source of most cyberthreats. The admiral disagrees. “All cyber reports will be darker in the future than they were five years ago,” he says, citing the recent SolarWinds hack – almost certainly by Russia – that affected software used by 400 of the Fortune 500 companies as well as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Treasury Department. “It ought to be a wake-up call for everyone!”

The think-tank regular who did influence the admiral’s thinking is Harvard scholar Graham Allison, author of “Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?” The ancient Greek historian Thucydides explained that “it was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.” Mr. Allison’s analysis is that in the past 500 years, there have been 16 cases in which a rising power threatened to displace a ruling one. Twelve of these ended in war. The question is whether China and the U.S. can avoid this fate.

“2034” would suggest that they cannot, unless American and Chinese leaders heed Thucydides’ warning – as well as that of Admiral Stavridis and Mr. Ackerman.

Jacqueline Adams is co-author of “A Blessing: Women of Color Teaming Up to Lead, Empower and Thrive.”

In Pictures: Meet the Muslim caretakers of Turkey’s Christian cave churches

When people of one faith appreciate and care for sites sacred to another religion, they’re going beyond tolerance. In this photo essay, we see them recognizing, and acting on, a sense of shared humanity.

-

By Ruwa Shah Correspondent

-

Ahmer Khan Correspondent

In Pictures: Meet the Muslim caretakers of Turkey’s Christian cave churches

In Cappadocia, a region in south-central Turkey, a river carved a deep cleft in the mountains and left behind a network of caves in the soft stone. Over centuries, people who dwelled here farmed the rich valley and built homes into the cliffs, which could be easily defended. Early Christians carved and hollowed out their own edifices, where they could worship unimpeded and hide in times of persecution from the Romans. Over the centuries, other Christian communities laid claim to the cave structures and often embellished them with frescoes.

Today, these beautiful, crumbling, rock-cut churches are looked after by local Muslim Turks, as seen in this photo essay. Some of them worked as cleaners and security guards in museums.

They are paid by the Turkish government to maintain the churches for the enjoyment of local and international visitors alike.

“It does not feel like a mere job,” says one of the caretakers, Mustafa, who did not wish to give his last name. “I come here and enjoy the prestige and history of this place. It is sacred to me,” he says.

“These are very ancient and sacred places,” says another caretaker, Ismail Genc. “Everything needs to be done with extreme diligence.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Britain reins in its company bonus culture

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One result of American business scandals over the past two decades is that more companies are careful about their pay incentives for executives. In the past, a shortsighted culture of cash bonuses in corporations encouraged reckless risk-taking and corruption. Now Britain wants to join the United States in finding the right balance for pay incentives. On Thursday, the U.K. business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, proposed rules to make it easier to claw back bonuses already paid to executives in failed companies as well as stop future payouts.

The proposed regulations “would help to get more transparency and, frankly, honesty in the system,” Mr. Kwarteng told The Times. “When big companies go bust, the effects are felt far and wide with job losses and the British taxpayer picking up the tab.”

Corporations that claw back or suspend bonuses at a time of failure or scandal are helping to build a better company culture. Studies show such policies improve the quality of a company’s financial reports, providing better clarity and certainty. Honesty can be its own reward, far more than a yearly bonus.

Britain reins in its company bonus culture

One result of American business scandals over the past two decades is that more companies are careful about their pay incentives for executives. In the past, a shortsighted culture of cash bonuses in corporations encouraged reckless risk-taking and corruption. Recent reforms, however, either done voluntarily or by regulation, have held managers more accountable. They allow bonuses only for long-term results or recoup compensation in case of wrongdoing.

Case in point: On Wednesday, Starbucks shareholders rejected the company’s plan for millions of dollars in special executive pay. Critics said performance bonuses have been too frequent and unjustified.

Now Britain wants to join the United States in finding the right balance for pay incentives. On Thursday, the U.K. business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, proposed rules to make it easier to claw back bonuses already paid to executives in failed companies as well as stop future payouts. In addition, larger companies would need to file “resilience statements” that spell out risks to a business, such as climate change or potential fraud in external partners.

The proposed regulations “would help to get more transparency and, frankly, honesty in the system,” Mr. Kwarteng told The Times. “When big companies go bust, the effects are felt far and wide with job losses and the British taxpayer picking up the tab.”

The proposed rules would also “hit auditors and rogue directors who have been asleep at the wheel,” another minister said.

Britain feels burned by its own recent business scandals, especially the 2018 collapse of construction firm Carillion. The company paid record dividends and bonuses just weeks before warning it was in trouble. The new proposals, which may take effect in 18 months, are described as the biggest shake-up of British corporate governance rules in decades.

Corporations that claw back or suspend bonuses at a time of failure or scandal are helping to build a better company culture. Studies show such policies improve the quality of a company’s financial reports, providing better clarity and certainty. Honesty can be its own reward, far more than a yearly bonus.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

God’s kingdom, within reach

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

“Your kingdom come,” Jesus prayed. Those three words point to a spiritual reality with powerful, healing relevance.

God’s kingdom, within reach

One of the lines in the Lord’s Prayer, which Christ Jesus gave to humanity, says of God, “Your kingdom come” (Matthew 6:10, New King James Version).

Those three words contain deep meaning. For instance, let’s reason forward in this way: If God is divine Spirit, which is one of the Bible-based synonyms for God emphasized in the teachings of Christian Science, then God’s kingdom is spiritual. In fact, divine Spirit – including the goodness of its kingdom – is not even combined with anything material. God is Spirit, through and through.

The Bible also explains that we are God’s offspring. So it follows that we are permanently included in Spirit’s divine kingdom. So is everyone else. It’s not that we hold some kind of chit for a future spirituality in another stage of existence. Our spiritual nature is actually our present, God-given status.

These ideas were very encouraging during a period when I had a persistent pain in my ankle that made it hard to walk normally. Simply thinking about how God is always present brought me hope. Through prayer I began to realize that because divine Spirit is perfect and utterly whole, there just isn’t any injury or deterioration in Spirit’s kingdom. The ankle injury wasn’t somehow an element of God’s kingdom that needed to be repaired. It wasn’t ever a part of God’s kingdom in the first place! God’s kingdom is pure – purely good.

And, best of all, it is our present reality. Here and now. The Christian Science Monitor’s founder, Mary Baker Eddy, says in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “This kingdom of God ‘is within you,’ – is within reach of man’s consciousness here, and the spiritual idea reveals it” (p. 576).

I continued to base my prayers on the spiritual fact that I actually had been a flawless child of God all along. God, perfect Spirit, expresses divine purity and goodness throughout creation. Our identity as God’s children, dwelling in Spirit’s kingdom, is always intact.

I saw that it was not in physicality, but my thoughts, where change was needed. As I realized that nothing could make me believe that injury was somehow an element of Spirit’s kingdom, I felt God’s presence and assurance even more clearly. And as quickly as my thought changed, I was free – permanently healed.

Now, when praying, I often like to step back and examine the foundation on which I am basing everything. God’s kingdom, where Spirit constantly reigns supreme, is already here, actively within us all. This forever fact is a very firm foundation for prayer. God’s kingdom of spiritual perfection is what’s real, here and now.

When the truth of God and of us as God’s spiritual offspring gently and deeply permeates thought, it destroys the belief that illness or discord is part of that spiritual reality. Then we are practicing Christian healing. Doing this is such a joyful thing. It’s worth it to take some time to be glad for the spiritual fact that, truly, God’s kingdom is come. God is expressing healing goodness and love right there within you.

A message of love

Downtime at the pier

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’ve got an audio interview with astrophysicist Alan Lightman talking about how technology is fragmenting our sense of time.