- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Biden seeks return to Iran deal. Can he bring Americans with him?

- A woman’s death in Mexico fueled outrage. Can it fuel police reform?

- Move over, markets. Big government is back.

- Ice Out: How N.H.’s rite of spring has become a symbol of climate change

- From rabbits to seaweed, new laws protect animals and climate

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

South Dakota’s juvenile justice revolution

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Katie Buschbach was not happy about South Dakota’s juvenile justice reforms. It was her job as a probation agent to bring kids in and keep them in line. As South Dakota pivoted from punishment to rehabilitation in 2015, “I was thinking, ‘This is going to be terrible,’” she tells Reveal, an investigative journalism website. “Nobody is going to be held accountable.”

Today, she says, “It’s the complete opposite.”

For decades, South Dakota had one of the highest juvenile incarceration rates in the nation, the podcast notes. Within three years of the reforms, the number of kids locked up in state facilities dropped by half, as did the state budget for juvenile justice. Ms. Buschbach’s job was actually cut, but she’s reinvented herself as a director of Davison County’s diversion programs, such as after-school activities. “We all make poor choices at some point, and it’s going to take repetition to learn that,” she says. “We’re teaching them how to make better decisions next time.”

It’s a lesson in how fresh and constructive thinking can make a difference, not just in budgets but in young lives.

Ms. Buschbach has seen juvenile recidivism in her community drop to about 8% – from a statewide average of 50%. She says, “The kids are getting a chance to make dumb decisions because they are a kid, but not be a criminal.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Biden seeks return to Iran deal. Can he bring Americans with him?

The U.S. and Iran have embarked on a path back to the nuclear deal. But President Joe Biden will have to navigate a hardening of attitudes among Republicans and even Democrats.

Proponents of the Obama-era nuclear deal with Iran could find encouragement in the agreement this week by both the United States and Iran that they would enter into talks aimed at a return to compliance. But now the hard work begins.

For Iran, that means reversing steps it took after then-President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal in 2018 – from ramping up uranium enrichment and stockpiling to installing more sophisticated centrifuges. On the U.S. side, it will entail a substantial undoing of the maze of more than 1,500 sanctions and punitive designations that the Trump administration slapped on Iran.

Both countries have powerful political forces that oppose any steps that could be construed as appeasement.

“In many ways the political environments in Tehran and in Washington are the mirror images of each other, from hyperpartisanship in the United States to a murkier but very substantial power struggle going on in Tehran,” says Thomas Countryman, a former assistant secretary of state.

And though President Joe Biden, deep into pursuing his domestic agenda, does not require congressional approval to return to the deal, he is now seen as loath to stir up controversial issues that could sour his relations with Congress.

Biden seeks return to Iran deal. Can he bring Americans with him?

Now comes the hard part.

The United States and Iran agreed this week to enter into talks aimed at delivering a path by which both countries would return to compliance with the 2015 Iran nuclear deal.

Successfully reaching the “compliance for compliance” deal that both Washington and Tehran say they want requires some rigorous work. On the U.S. side it will entail a substantial undoing of the maze of more than 1,500 sanctions and punitive designations that the Trump administration slapped on Iran after then-President Donald Trump pulled out of the deal in 2018.

What Iran will be called on to do is more straightforward: reversing the steps it took after the U.S. withdrawal – from ramping up uranium enrichment and stockpiling enriched uranium to installing more sophisticated centrifuges – that put it in serious violation of the international accord.

But with attitudes in both countries toward the Obama-era deal having hardened, and the mistrust between the two longtime adversaries only stronger, even proponents of a full return to the Iran nuclear deal acknowledge that the road back to compliance won’t be easy.

“In many ways the political environments in Tehran and in Washington are the mirror images of each other, from hyperpartisanship in the United States to a murkier but very substantial power struggle going on in Tehran,” says Thomas Countryman, a former assistant secretary of state for international security and nonproliferation.

Both countries have powerful political forces that oppose not just a return to the deal, but also any steps that could be construed as appeasement.

Iran is in the midst of a presidential election campaign that analysts say is amplifying hard-line voices – and which could turn more sectors of public opinion against the deal over the weeks before the June 18 vote.

What honeymoon?

In the U.S., President Joe Biden might seem to be in a more favorable political situation for pursuing his oft-stated goal of a return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), since he is still in the first months of his presidency and is enjoying relatively high public approval.

But he hasn’t had much of a honeymoon in terms of foreign policy, analysts say, as he has faced a dressing-down from an increasingly assertive China over his “call to battle” to the world’s democracies, and pressure from thousands of migrants arriving at America’s southern border.

Mr. Biden’s return to diplomacy with Iran is not likely to be any easier than the other key foreign policy challenges he faces, given the hardened outlook toward Iran and the deal.

Most Republicans but even some Democrats have if anything become more adamant in their opposition to the JCPOA, which critics say provided Iran with a windfall of billions of dollars (mostly Iranian assets that had been held up in foreign coffers in line with international sanctions) while doing nothing to curb its provocative regional activities and ballistic missile development.

“The Biden administration unwisely has entered a diplomatic labyrinth designed by allies who seek an unconditional U.S. return to the flawed nuclear deal,” says James Phillips, senior research fellow for Middle Eastern affairs at Washington’s Heritage Foundation.

Reflecting recent assertions from congressional critics, he says returning to a deal will only embolden Iran, both in its nuclear program and in the region.

The goal of the Vienna talks, to get all parties back into full compliance with the JCPOA, is “likely to pressure Washington into granting premature sanctions relief to Iran,” Mr. Phillips adds – a move he says “will empower and enable a predatory regime that has a long record of violating its nonproliferation obligations.”

Hawkish Europeans

The hostile environment for diplomacy with Iran does not stop at the United States. Even the three European powers that are signatories to the deal – France, Germany, and the United Kingdom – have turned more “hawkish” on Iran, European sources say, even though they still want the U.S. back inside the agreement.

Similar to some longtime U.S. proponents of the JCPOA, America’s transatlantic allies are disappointed that Iran did not modify its regional behavior as a result of entering into the international accord – so they want now to get to a broader agreement that reduces tensions in the Middle East.

Proponents of a return to the JCPOA say Iran’s resumption of proscribed nuclear activities since the U.S. pulled out of the accord is in fact a central argument for the U.S. to get back into the deal. They note that Iran’s estimated breakout time to nuclear weapon capability increased to well over a year under the JCPOA, whereas international experts now estimate that the time Iran would need to deliver a nuclear weapon with the materials it has assembled is down to about three months.

Many JCPOA proponents say it was a “mistake” for Mr. Biden to put off a quick return to the nuclear deal, along the lines of his Day 1 return to the Paris climate accords. After all, Mr. Biden had campaigned on a pledge to rejoin the accord quickly, touting it as the best way to head off a looming nuclear crisis.

But instead, Mr. Biden and his foreign policy team focused on the “longer and stronger” and more comprehensive deal they say they want with Iran (something President Trump also said he was aiming for) while they reassured members of Congress that any deal was a long way off. Sources close to the White House say the shift away from acting quickly reflects divisions in the Biden team over the wisdom of a quick JCPOA return.

Now Mr. Biden is deep into pursuit of his top-priority domestic agenda, and even though he does not require congressional approval to lift sanctions and return the U.S. to the deal, he is now seen as loath to stir up controversial issues that could sour his relations with Congress, and particularly with his own party.

Trump’s added obstacles

Moreover, Mr. Biden’s political path is made only more complicated by the myriad sanctions and other Iran-related measures the Trump administration imposed right up until its final days in office. Indeed, many of those actions were designed not so much to punish Iran, JCPOA advocates say, but to make Mr. Biden’s return to the deal as onerous as possible.

“What will be controversial is exactly what the Trump administration and the regime-change lobby intended to make controversial by ... [blurring] the line between nuclear-related sanctions, which must be lifted under the JCPOA, and all kinds of terrorism and human rights designations under other legislative authority,” says Mr. Countryman, who is now chairman of the Arms Control Association board of directors.

If Mr. Biden agrees to lift most of the measures the Trump administration imposed after leaving the deal, he adds, it will entail “lifting also designations the Trump administration labeled as terrorism and human rights, and that’s the point at which the president’s enemies will attack him.”

Those political attacks are likely to be all the louder given the hardening of positions in Iran and an accompanying rise in conflict with American allies and interests in the region as it has become clear that Mr. Biden would not return quickly to the nuclear deal.

“There has been a shift that actually has created more distrust in Tehran,” said Vali Nasr, former dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, speaking at a University of Maryland forum before the return to talks. “They don’t see a return to [JCPOA] anytime soon, so they are engaging in behavior that is going to make it even more difficult for the Biden administration to take the first step.”

Not to be outdone by the Iranians in terms of toughness, members of Congress are letting it be known they prefer the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure campaign” to any return to Iran diplomacy.

In a statement issued Friday in response to word the Biden administration would take part in this week’s Vienna talks, Republican Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma warned, “As a reminder: Members of Congress rejected the JCPOA on a bipartisan basis in 2015. If you repeat history next week by restoring that failed agreement,” he added, “we will work to reject it once again.”

A woman’s death in Mexico fueled outrage. Can it fuel police reform?

Police violence has prompted protests from Paris to Minnesota. Mexican police have made progress, but a new, high-profile killing is fueling a demand to push further.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Victoria Esperanza Salazar Arriaza was killed March 27 outside a convenience store in Mexico. A police officer knelt on her back to restrain her, breaking her neck – one of numerous high-profile incidents of police violence over the past year. Protests swarmed Tulum’s city hall in the days following Ms. Salazar’s death, and reignited over the weekend during her burial.

But with the spotlight on police violence not just in Mexico, but around the world, some hope the outrage could help build momentum for change. On paper, the country’s legislation around policing is advanced. The problem is enforcement, analysts say, not to mention budget cuts. Training is haphazard, corruption ever-present, and officers’ salaries low.

“Socially and culturally there’s more pressure today on Mexico police agencies than there was 20 years ago, to engage in these kind of systematic reforms,” says David Shirk, director of the Justice in Mexico project. “It might not feel like that, but the fact that we’re even talking about this case is a reflection of increased accountability. Society won’t stand by.”

A woman’s death in Mexico fueled outrage. Can it fuel police reform?

While the United States is focused on the Derek Chauvin trial, a reckoning with an eerily similar encounter is unfolding in Mexico.

On March 27, Victoria Esperanza Salazar Arriaza was killed outside a convenience store in Tulum, when a police officer knelt on her back to restrain her, breaking her neck. The encounter between Ms. Salazar, a Salvadoran living in Mexico on a humanitarian visa, and four police officers was videotaped by a bystander. Her death sparked nationwide protests – and has drawn international attention to police violence in a country that spent nearly a decade reforming its justice system, including the police.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador was quick to condemn the event as murder, and the officers were promptly jailed and charged with femicide. This is just one of a handful of high-profile deaths at the hands of police over the past year, which observers say could mark an important moment in pressuring institutions and the government to prioritize police reform.

Police are some of the lowest paid public servants in the country. Training is haphazard, and corruption ever-present. In lieu of police unions are informal “brotherhoods,” which can perpetrate cronyism and abuse. On paper, Mexico’s legislation around policing is advanced, with lauded regulations, for example, around use of force. The problem is that enforcement has long been skirted, and the current administration has cut police budgets at state and municipal levels.

There have been numerous high-profile incidents this year alone. At least 12 police officers were implicated in the killing of a group of mostly Guatemalan migrants in January, and earlier this week seven officers in Jalisco were arrested for the kidnapping and disappearance of a family returning from Easter vacation.

Public attention has increased pressure, as has a more robust civil society. And the international atmosphere, with police violence generating mass protests from the U.S. to France to Colombia, also lends a sense of urgency.

“Often there are these critical junctures, these moments where something really bad happens and we have an opportunity to press for change, and this is hopefully one of those moments in Mexico,” says David Shirk, director of the Justice in Mexico project at the University of San Diego. “Unfortunately, we have a lot of these moments in Mexico,” he adds. “But I think this is something we’ll be talking about for more than just a couple weeks.”

Long-term change

Nearly two-thirds of people detained by the police in Mexico were beaten or hit during arrest, according to the most recent survey by Mexico’s statistical agency. In almost 50% of cases, the person carrying out the arrest didn’t identify themselves as law enforcement.

There’s been “substantial development in terms of both professional standards and use of force” among the police over the past two decades, says Juan Salgado, a researcher at the World Justice Project in Mexico City. Yet “there’s little consequence for police brutality in Mexico,” he says. That squares with Mexico’s sky-high impunity rates overall. About 1.3% of crimes are resolved, according to the nongovernmental organization Impunidad Cero.

It’s not just the lack of negative consequences that are the problem. “There are no positive consequences for good conduct,” says Elena Azaola Garrido, an anthropologist who studies prisons and security in Mexico. An estimated 450 officers are killed annually in Mexico, according to the nonprofit Causa en Común, making it one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a police officer. Many police report having to pay their superiors “dues” to hold on to their jobs, and promotions are often doled out based more on relationships than accomplishments or completed trainings, Dr. Azaola says.

Mexico passed sweeping judicial reforms in 2008, including more police training around collecting evidence and gathering testimony.

“Mexico has over the last decade or so been raising the bar for police conduct and prosecutorial conduct,” says Dr. Shirk. But reforms weren’t fully implemented until 2016, “and it takes a long time to see institutional change.”

These medium- to long-term changes require continuity from future governments, says Erubiel Tirado, a security specialist at Ibero-American University. He worries that the current administration’s move back toward militarized policing under the newly formed National Guard, paired with sizable federal budget cuts, could undermine progress. Federal funding for federal and local police has dropped consistently over the past 15 years, from 1.2% of gross domestic product to 0.8% today.

“There are no resources for training or professionalizing the police, especially at the municipal and state levels. The government has not just abandoned the police, they’ve pushed any progress backward,” says Dr. Tirado.

Pushing ahead

Protests swarmed Tulum’s city hall in the days following Ms. Salazar’s death, and reignited over the weekend during her burial. Those hit hardest by police violence tend to be the most vulnerable: migrants, people living in the streets, poor people, and often women. But rarely are abuses caught on tape or brought to national attention.

The case in Tulum, and the January murders of nearly 20 migrants near the border, hit on two flash points fueling outrage. Violence against women has received increasing attention over the past several years, with a diverse, increasingly powerful feminist movement spurring marches and protests against the government’s perceived inaction. And in some of these cases, foreign governments have called out Mexico’s violence against their citizens, shining an even harder-to-avoid light on the problem.

As a result, officers involved are often quickly charged and imprisoned, as was the case in Tulum. But that misses the bigger opportunity to do more than root out “bad apples” and dole out “performative punitism,” says Dr. Shirk. There needs to be institutional soul-searching and the tackling of structural issues.

“These protests are necessary and important, but they’re not enough,” says Dr. Azaola. Protests may put pressure on officials, but they often don’t lead to identifying what needs to change and how. The fact that the laws on the books are quite advanced means legislative action isn’t necessarily the end game. “It comes down to [changing] institutional inner-workings,” enforcement, and weeding out corruption.

But there are cases where street protests have forced the government’s hand, and that gives some people hope.

“Socially and culturally there’s more pressure today on Mexico police agencies than there was 20 years ago, to engage in these kind of systematic reforms,” Dr. Shirk says. “It might not feel like that, but the fact that we’re even talking about this case is a reflection of increased accountability. Society won’t stand by.”

Dr. Salgado points to a video that emerged in Jalisco last year, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests in the U.S. A bricklayer was detained by police, reportedly for not wearing a face mask. When his family went to collect him from the police department, they were directed to the morgue.

Street protests exploded, and in Guadalajara, young protesters began to be abducted. But the repeated, high-profile human rights violations led the state to form a working group of civil society representatives, victims of crime, scholars, and government officials to try and develop better accountability and human rights frameworks for police.

“It may be too early [to applaud this initiative],” Dr. Salgado says. “But this is unusual in Mexico.”

Patterns

Move over, markets. Big government is back.

Over the past half-century, most Western governments have shrunk their ambitions and handed the economic initiative to private enterprise. But the pandemic has changed all that.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The pandemic has upended a lot of accepted wisdom. Its latest victim is a long-standing piece of Western economic orthodoxy – that governments should stay out of the economy as much as possible.

Today, big government is back, and with a vengeance. On both sides of the Atlantic, the authorities are drawing up ambitious post-pandemic recovery plans and pouring trillions of dollars into their implementation.

This is a far cry from Ronald Reagan’s famous declaration, in his 1981 inaugural address, that “government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem.” Such thinking has guided many countries since. But the new – or revived – approach holds that national governments still matter, and that there are some things that only they can do.

For the time being, the U.S. public seems to agree with President Joe Biden that this is the case. Voters also support higher taxes on businesses and wealthier Americans to raise the money to pay for ambitious new infrastructure schemes.

Whether that stays the case could be a key signal of whether big government is back for good.

Move over, markets. Big government is back.

Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, and Tony Blair make odd bedfellows in many respects. But they all rode, or embraced, the same powerful political wave that has swept major Western democracies for nearly half a century: distaste for the work of national governments.

Has that wave now passed, overtaken by the effects of the pandemic?

Big government is staging a dramatic comeback, and U.S. President Joe Biden’s $2.6 trillion infrastructure and investment plan is just the latest sign. After all, his predecessor, Donald Trump, signed off on nearly double that amount in pandemic spending.

Across the Atlantic, the government of British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has broken with the orthodoxies of Ms. Thatcher and his other Conservative predecessors to announce billions of dollars in new spending, along with higher taxes to pay for it all.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel – once the very embodiment of fiscal restraint – has signed off on stimulus and recovery plans to the tune of nearly $1.5 trillion. She’s also embraced the idea that an activist government should support and even buy into companies critical to Germany’s future economic strength.

Last year, governments spent money to relieve the immediate effects of an economic tsunami. But the new packages are longer-term, aiming to build modern post-pandemic economies with an emphasis on digital and low-carbon initiatives.

The world might, perhaps, return to the “old normal” once the pandemic has passed. Yet so far there’s been wide political and popular support for more muscular government.

And it’s hard to overstate the magnitude of the change.

The old orthodoxy took root in the 1980s, when American economist Milton Friedman helped convince President Reagan and Prime Minister Thatcher to challenge the prevailing Keynesian model, which had underpinned massive government intervention in national economies in the wake of World War II.

This approach was not just misguided, ran the new philosophy, but an affront to the way democracies should work: It elevated government’s role above the independence and initiative, the lives and interests, of the governed.

“Government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem,” Mr. Reagan declared in his first inaugural address, in January 1981. Ms. Thatcher lamented that too many people had been taught to think that when they faced a challenge, “it is the government’s job to cope with it.”

Their revolution has resonated ever since.

“The era of big government is over,” U.S. President Bill Clinton declared in the 1990s. Britain’s Labour government, under Prime Minister Blair, revived spending in some areas. But it generally followed the Thatcherite course of favoring private sector funding, or public-private partnerships, over old-style public sector projects that had to be financed by taxes or borrowing.

Just four years ago, French President Emmanuel Macron came to power vowing to pare back state subsidies of his country’s railways, and to reform the costly national pension system, policies Ms. Thatcher might have applauded.

And the political knock-on effects of the shift toward smaller government made a rethink more difficult and unlikely. Until the pandemic struck.

The better-off welcomed the lower taxes. Business people favored less regulation and fiscal policies that made their companies more competitive in a globalized economy.

Those who needed the government assistance that was being scaled back or eliminated felt resentful and angry. Yet the populist politicians who harnessed their anger directed it not so much against a particular government as against government itself. Many people lost their trust in presidents and prime ministers, of whichever party, to do anything to help.

The pandemic and the economic shutdowns that followed upended all of this.

The stark and sudden message was that national governments still mattered. Indeed, there were some things that only national governments could do.

President Biden’s calculation, as he pushes for a spending program bigger than anything America has seen since World War II, is that this new appreciation for the role of government will last. Prime Minister Johnson, Chancellor Merkel – and President Macron, too, whose government has unveiled a “France relaunch” plan of its own – are making a similar bet.

To judge from polling in America, where there’s been public support among both Democratic and Republican voters for the infrastructure plan proposed by Mr. Biden, they may prove to be right.

But it’s worth noting the main argument Republican politicians have been making to chip away at that support. They are not opposed to government investment in national infrastructure as such – and the plans rival the New Deal’s rural electrification and the postwar construction of interstate highways in their scope and ambition.

But they are taking aim at the way President Biden plans to pay for it, through tax increases on businesses and wealthier Americans.

For the moment, most voters don’t seem to have a problem with that. Whether such an attitude holds, however, could be a key signal of whether big government is back to stay.

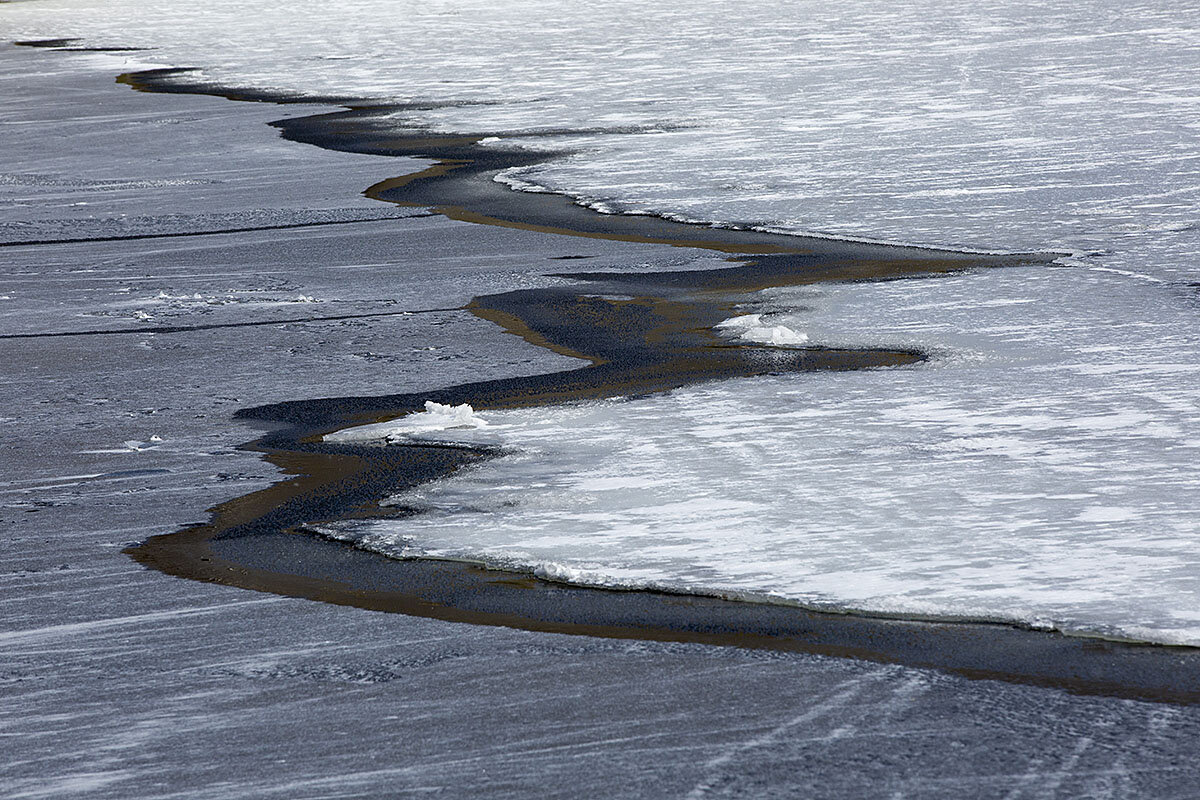

Ice Out: How N.H.’s rite of spring has become a symbol of climate change

Lake Winnipesaukee always celebrates the day the ice is gone and spring boating can begin. But when that day comes earlier and earlier, there can be ripple effects.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

There’s a lot riding on Ice Out – the day when New Hampshire’s Lake Winnipesaukee is sufficiently free of ice for the popular MS Mount Washington sightseeing vessel to reach all five of its ports. When that time comes, Ice Out celebrations can begin and spring is just around the corner.

But to those who study lake ecosystems, Ice Out means more than the start of boating season. In the Northeast’s lake ecosystems, ice is a determinant of everything from water temperature to aquatic food chains to water quality. And according to long-term climate data, ice-out has been moving earlier and earlier – a sign, scientists say, of warming winters in the Northeast as a whole.

Over the past century, New Hampshire has lost 21 days of snow cover, the average annual temperature has increased 3 degrees, and there are 18 fewer days when the nighttime temperature drops below freezing.

“For us in New England, winter is the fastest-changing season,” says ecosystem ecologist Alix Contosta. “We’re seeing the biggest changes in temperature in winter as compared to the rest of the year. ... We are losing the cold.”

Ice Out: How N.H.’s rite of spring has become a symbol of climate change

For the past few weeks, Dave Emerson has been taking off from his airstrip on the southern side of Lake Winnipesaukee, flying his Cessna across this largest lake in New Hampshire, and looking – very carefully – for ice.

As of last week, it was almost gone. But not quite. Not enough to call “Ice Out,” that magical moment when the MS Mount Washington, the 230-foot excursion vessel that’s been transporting tourists on this lake since the 1940s, is able to reach every one of its five ports. Center Harbor, the town on the northern fingers of the “Big Lake,” as people here call it, was still iced in. There were chunks still floating in the town of Wolfeboro’s harbor to the southeast. But it was only a matter of days that the lake would be clear, and Mr. Emerson, owner of Emerson Aviation, pledged to the many, many people following his updates that he would keep flying, multiple times a day, and would let them know as soon as the moment arrived – the way he has been doing since 1979.

Much, after all, is riding on Ice Out. Restaurants, rotary clubs, and town chambers of commerce distribute thousands of dollars to raffle contestants who most accurately guess its date and time. The New Hampshire Boat Museum holds an annual Ice Out Celebration (virtual, this year, scheduled for April 16). And for those who live here, Ice Out means that spring is actually around the corner – that it’s time to replace snowmobiles and bob houses with hiking boots and sailboats.

“It’s the changing of the seasons,” says Martha Cummings, executive director of the boat museum. “The ice is gone, boaters can get back on the water, spring is on its way, and we can all get out of our houses and go outside again.”

But to scientists who study lake ecosystems, Ice Out means something even more. Ice is a key player not only in the culture of the northern Northeast, but also in its unique lake ecosystems – a determinant of everything from water temperature to aquatic food chains to water quality. And according to long-term climate data, ice-out has been moving earlier and earlier – a sign, scientists say, of warming winters in New Hampshire and the Northeast as a whole.

“For us in New England, winter is the fastest-changing season,” says Alix Contosta, an ecosystem ecologist with the University of New Hampshire’s Earth Systems Research Center. “We’re seeing the biggest changes in temperature in winter as compared to the rest of the year. ... We are losing the cold.”

Over the past century, Dr. Contosta and other researchers have found, New Hampshire as a whole has lost 21 days of annual snow cover. The average annual temperature in the state has increased 3 degrees since the beginning of the 20th century, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and research shows that there are 18 fewer days now when the nighttime temperature drops below freezing than there were a century ago. Fewer places in the region have 30 days of continuous snow coverage.

Bigger extremes

“Rain on snow” events are far more common (as those who must plow their driveways can attest), as is intermittent melting, says Brenda Ekwurzel, senior climate scientist and director of climate science with the Union of Concerned Scientists. The warmer temperatures also lead to more moisture in the atmosphere, she says, which in turn creates heavier snows and rainfalls. Indeed, she says, the most extreme precipitation events – those big snow and rain storms – contain 50% more water volume now than they did in the 1950s.

“The characters of winter are changing,” Dr. Ekwurzel says.

And so, she and others say, are the lakes.

For more than 50 years, Gene Likens, founding director of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and special adviser on environmental affairs at the University of Connecticut, has recorded detailed observations about the ice cover on Mirror Lake, in the southern White Mountains of New Hampshire.

There, scientists call ice-out when less than 50% of the surface water is frozen, explains Tamera Wooster, a technical staffer who works with Dr. Likens at the Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study, a multidisciplinary, long-term ecological study that includes Mirror Lake.

She’s the one whose job it is to say when that happens, so this time of year she drives regularly to different points on the wind-swept shoreline and looks.

As of last week, the bob houses were gone – ice fishers have an astute sense of when their sport should end for the season, she says – but the lake’s surface was still almost all ice.

Still, that ice was thin.

“It would only take a couple of sunny days and a rainstorm and we’re out,” she says.

On average, Dr. Likens has found, the ice cover on Mirror Lake lasts for approximately 21 fewer days than when he started recording it in 1967. That is similar to what has happened at other lakes throughout the region, although the pattern is not linear.

Indeed, a graph on various lakes maintained by the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services shows a downward-sloping fan of ice-out dates, as the year moves from the 1860s, when ice-outs were first recorded, to the present. During the 1990s, some lakes lost their ice covers as early as the beginning of March, an unprecedentedly early ice-out. Other years saw the typical late April and early May melt.

Ecological effects

This erratic pattern is what scientists say they see regularly with climate change. There are new extremes, with the overall trend being a warming one.

And that, Dr. Likens says, has a slew of ecological impacts. An ice cover on a lake not only seals off the water from wind and circulation, but also creates a platform for snow, which then reflects the sun. Conversely, a dark surface, such as open water, or even a leaf resting on a piece of ice, will absorb much of the sun’s heat – a smaller version of what many climate scientists talk about when it comes to the accelerating heating cycle of the polar ice melts.

The northern lake ecology is tied to this balance of having a cold, reflective surface for part of the year, and a heat-absorbing one for the rest. When ice-outs come early, the water temperatures rise; this, in turn, creates better habitats for algae and, scientists believe, cyanobacteria – a type of single-celled organism that can harm other animals. Early ice-out can also affect the way a lake’s water mixes, and its oxygen levels.

“Ice, for a lake, is very, very important for setting the summer conditions,” says Dr. Ekwurzel. “What the fishing conditions are, what the oxygen levels are, the amount of nutrients that might be running off agricultural land.”

Some worry that early ice-outs could be changing winter culture in what’s known as New Hamsphire’s Lakes Region. The Alton Bay Ice Runway, which advertises itself as “the only plowed ice runway in the Continental US (that we know of!),” was only open for two weeks this year, after not being able to open at all in 2020. Ice boaters, whose sailing crafts on metal runners depend on solidly formed ice, have told Ms. Cummings, from the boat museum, that their seasons are shorter.

“Our boating community has noticed the difference,” she says.

“An opportunity to learn more”

But this difference, says James Haney, a professor of biological sciences at the University of New Hampshire, can be an invitation for curiosity as much as concern.

“I think the climate change and ice-off is generally looked at as a harbinger of bad news,” he says. “I look at it as an opportunity to learn more.”

To others, the ice fluctuations are just another example of the weather surprises that New Hampshire has always thrown at them.

“Tell me a time climate hasn’t been changing,” says Mr. Emerson, who was heading up one more time to see if he could make his call.

Based on what he saw, he expected ice-out on Winnipesaukee would come soon. And indeed, at 4:42 p.m. on Monday, he was able to make his call.

“It’s official!” he wrote on his Facebook post, which has since been shared more than 1,300 times. “Welcome to Spring in NH.”

Mr. Emerson would not enjoy any of the raffle winnings, though. He doesn’t make predictions about ice-out, even though he gets a lot of inquiries.

“Someone would be calling it fixed,” he says. “I stay away from all the contests.”

Mirror Lake was not far behind. Ms. Wooster called ice-out there on Tuesday – a week earlier than average.

Points of Progress

From rabbits to seaweed, new laws protect animals and climate

This week’s roundup of global progress includes two women who are “firsts” in their professions. Their rise spotlights both individual achievement and the work left to do for equity.

From rabbits to seaweed, new laws protect animals and climate

1. United States

Virginia has joined three other states in banning cosmetics testing on animals. Companies often test new cosmetics on rabbits, mice, and other animals to ensure they’re safe for human use. Animal advocates say these methods are cruel and unnecessary, considering all the alternative ways to test the effects of moisturizers, makeup, and other cosmetic items.

The Humane Cosmetics Act, which goes into effect Jan. 1, 2022, prohibits cosmetics companies from testing on animals and bans the sale of products tested elsewhere on animals. California, Nevada, and Illinois have similar legislation. Animal testing of cosmetics and the sale of such products are also banned in the European Union, Iceland, India, Israel, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

ABC News, The Hill, Humane Society

2. United States

The Senate confirmed Rep. Deb Haaland as secretary of the interior, making her the first Native American to lead a Cabinet agency. The Interior Department manages more than 450 million acres of public land, federal waters off the coast, and a massive system of dams and reservoirs in the Western United States. It also has a contentious history with the country’s Indigenous population, housing both the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Indian Education, which have a long track record of neglect and abuse toward Native American communities.

Ms. Haaland, who describes herself as a 35th-generation New Mexican and is an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, is expected to make climate change and racial justice central to her leadership of the agency. “A voice like mine has never been a Cabinet secretary or at the head of the Department of Interior,” she said on Twitter. “Growing up in my mother’s Pueblo household made me fierce. I’ll be fierce for all of us, our planet, and all of our protected land.”

The New York Times, Department of the Interior

3. United Kingdom

A new bylaw banning trawl fishing off the Sussex coastline will help protect 117 square miles of seabed and give kelp forests the chance to recover from recent degradation. At one time, these dense swaths of long seaweeds created a nursery for seahorses, lobsters, and other commercially important wildlife, and sequestered large amounts of carbon dioxide. Over the past few decades, storms, trawling, and dredging boats have nearly eliminated these vital habitats, advocates say.

Following a campaign by the Help Our Kelp partnership, with support from natural historian Sir David Attenborough and the Sussex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority, the U.K. government has approved a year-round trawling ban to relieve that pressure on the ecosystem. Ocean advocates are calling the new law a win for marine conservation. “We welcome the signing of the Sussex bylaw,” said Charles Clover, executive director of the Blue Marine Foundation, “as it is a recognition by government that rewilding the sea is a way to protect marine biodiversity, invest in inshore fisheries, and store carbon at a single stroke.”

The Guardian

4. Russia

Public transit officials in Moscow have announced plans to replace all gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles with environmentally friendly alternatives in the next decade. The road map set forth by Mosgortrans, which runs Moscow’s vast bus and tram network, will nearly quadruple the city’s electric bus fleet well ahead of that deadline.

The Russian capital began replacing old buses with green models in 2018, and Moscow says it now has the largest fleet of any European city with roughly 600 electric buses in operation. Under the new plan, authorities say they will only be purchasing electric vehicles, expanding the fleet by 400 vehicles this year, another 420 next year, and then by 855, bringing the city’s e-bus count to more than 2,000. Swapping a diesel-powered bus with an electric model removes an average 60.7 tons of CO2 emissions from the environment every year, according to Green Car Congress. Mosgortrans is also investing in more power-efficient trams.

Reuters, Green Car Congress

5. Indonesia

Small-scale fishers are increasingly utilizing digital tools to protect their livelihoods. About 90% of workers involved in capture fishing – when commercial fish are caught in a natural environment – are from household-sized operations, and about half are in developing countries, according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization. These workers face “many challenges – from multiple marine uses, declining fish stocks, threats from overfishing – and climate change is just going to exacerbate those challenges,” said Alexis Rife of the Environmental Defense Fund. Launched by EDF in January, the Small-Scale Fisheries Resource and Collaboration Hub is a multilingual website designed to help fishers, coastal communities, and advocacy groups develop solutions together.

Fishers already use social media platforms for pricing, but the website’s low data requirements serve areas with patchy internet. One pilot project in Indonesia uses artificial intelligence to track fishing vessels and estimate catches. In Sumatra, fishers are testing an EDF app that records catches to enable them to be more sustainable.

Thomson Reuters Foundation, Food and Agriculture Organization

6. Congo

Congo has hired its first female soccer coach. Maguy Safi has been appointed to head the new women’s team of Tout Puissant Mazembe, one of the largest and most popular soccer clubs in Africa. Despite being a champion athlete and holding a degree in physical education and sports management, Ms. Safi often faced overt discrimination and sexist remarks when applying for coaching positions. But she knew from experience that the field was changing and continued to work toward her professional goals.

TP Mazembe established its women’s club to meet new requirements from FIFA and the Confederation of African Football. Although women’s soccer tournaments aren’t as developed in Congo as in other African countries, there is growing interest in the sport among young women and lots of talent, according to professionals who engage with their teams. Ms. Safi hopes to continue breaking down stereotypes about women in soccer, and eventually coach a national team.

Radio France Internationale

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A page-turner peace narrative for India, Pakistan

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

India and Pakistan have viewed each other as an enemy for so long that they are struggling with a potential new narrative: peace. Since February, their two militaries have honored a cease-fire agreement in disputed Kashmir. Their officials have held talks over a treaty on sharing the Indus River. India offered COVID-19 vaccines to Pakistan. In March, Pakistan’s army chief, Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa, called upon both countries to “bury the past and move forward.” The countries’ prime ministers exchanged letters of greetings and gratitude. In his letter, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said relations must now move toward an “environment of trust.”

Like past warm spells, India and Pakistan could again revert to hostility. Each has powerful domestic players with a stake in maintaining an enemy narrative. Resolving their differences in Kashmir will be difficult. But India and Pakistan are now addressing many of their points of friction with careful overtures, motivated by a mix of domestic and foreign pressures. Yet just as important is to project a new narrative of peace. It might actually devise real peace.

A page-turner peace narrative for India, Pakistan

India and Pakistan have viewed each other as an enemy for so long that they are struggling with a potential new narrative: peace.

Since February, their two militaries have honored a cease-fire agreement in disputed Kashmir. Their officials have held talks over a treaty on sharing the Indus River. India offered COVID-19 vaccines to Pakistan. In March, Pakistan’s army chief, Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa, called upon both countries to “bury the past and move forward.” The countries’ prime ministers exchanged letters of greetings and gratitude. In his letter, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said relations must now move toward an “environment of trust.”

Further steps are possible, especially as the United Arab Emirates is reportedly providing back-channel diplomacy. Mr. Modi could meet with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan. The two countries might exchange ambassadors or hold a binational cricket match. If they open their closed border for commerce, trade could jump from about $2 billion to an estimated $37 billion. Pakistan’s prime minister, a former cricket star, said recently, “The only way the subcontinent can tackle poverty is by improving trade relations.”

Like past warm spells, India and Pakistan could again revert to hostility. Each has powerful domestic players with a stake in maintaining an enemy narrative. Resolving their differences in Kashmir will be difficult. While their governments are largely secular, each struggles over whether their nation should be anchored in a religious identity (Hinduism for India, Islam for Pakistan). Those internal debates make it easy to use the other as a convenient foe.

Each has compelling reasons for peace. Pakistan needs a peaceful neighborhood to boost a stagnant economy and reduce military spending. India lately worries about an aggressive China. Both foresee a new regional dynamic if the United States pulls out of Afghanistan.

The hardest part may be a mental one: moving beyond the enemy narrative to simply being friendly competitors. Real issues exist between them, many driven by previous conflicts. But as Nelson Mandela said after 27 years of prison in white-ruled South Africa, “Resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies.”

India and Pakistan are now addressing many of their points of friction with careful overtures, motivated by a mix of domestic and foreign pressures. Yet just as important is to project a new narrative of peace. It might actually devise real peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The path forward

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lisa Troseth

Sometimes it can seem tough to find and stay on the path toward progress. But as a young woman experienced when she found herself in an unhealthy relationship, God gives us the strength and wisdom we need to think and act in ways that bless ourselves and others.

The path forward

I got tangled up again in a bad relationship. I knew it was a step backward. My former boyfriend and I hadn’t seen each other for over a year, during which time I’d begun to really open my heart to God.

It was early in my study of Christian Science, and I was learning that God is infinite Love, and that as the children, or spiritual image, of God, we’re inseparable from Love. This was having a healing impact on my disposition, causing me to be more unselfish and kind.

I was awakening to what it says in the Bible’s book of Colossians: “You have taken off your old self with its practices and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator” (3:9, 10, New International Version). This is what Christ Jesus lived to show us, that our genuine nature and identity flow from God and are purely good.

But when I moved across the United States, far from familiar friends and places, it threw me for a loop, and I fell into a depression. My former boyfriend called one day, and we got ensnared again in the relationship. There were good moments, but more often than not we brought out the worst in each other.

At one point, I flew cross-country to see him, and on the return trip I broke down and sobbed. It felt as though the previous year’s progress had been derailed. I alternated between sleeping and crying for most of the flight.

Yet each time I awoke, the melody of a hymn played softly in thought, which buoyed me. It was a musical setting of a poem written by Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science. I didn’t remember the words beyond the first line: “It matters not what be thy lot, / So Love doth guide” (“Poems,” p. 79).

It felt as if God was saying: “No matter what, I won’t let you sink. I’ve got you, and I’m never letting go.” It was the Christ, or voice of divine Love. Christ is always communicating in whatever way we need to hear it (even singing to us!), assuring us we’re at one with God as the very expression of God’s goodness and love.

For a number of weeks after that, I put everything else on hold to pray and study the Bible and Mrs. Eddy’s writings. Passages in these books assured me that God leads our lives forward on a path of Christly transformation. For instance, in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy says: “Truth makes a new creature, in whom old things pass away and ‘all things are become new.’ Passions, selfishness, false appetites, hatred, fear, all sensuality, yield to spirituality, and the superabundance of being is on the side of God, good” (p. 201).

A fresh sense of joy emerged, along with the conviction that I could trust God to move both me and my boyfriend forward in our lives – to grow more fully in expressing our God-given goodness and love. The selfishness and immaturity that had dominated our relationship wasn’t part of what either of us really was.

This gave me the courage to simply end the relationship without any fuss. We both moved on in good ways, and there was no turning back.

Through all of this, I also learned that God gives us authority over whatever tries to pull our thought and behavior backward, in a direction contrary to God’s good intention for us. And through prayer, we come to find that God is constantly encouraging us forward on the path of expressing our true Godlike nature.

In these challenging and fluctuating times, we may be encountering all sorts of situations where it can feel tough to be loving and generous, as well as wise. Communities and nations are grappling with this, too, in areas where there’s been an unraveling of norms. But praying more consistently throughout each day attunes us to the voice of divine Love that calls us to be a healing force for good, by realizing that Love is what truly animates us all.

God’s goodness can’t be undone. God forever upholds our Christly goodness, and it’s God’s loving will for us to “put on [our] new self” and really live.

A message of love

Where winter meets spring

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at how voters in red states are viewing President Joe Biden’s pandemic relief plan.