- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘He has not bowed’: Jimmy Lai and Hong Kong’s future

- Why Iran nuclear talks are moving ahead, despite Israeli attack

- She’s seen peacekeeping fail. Here’s her advice on getting it right.

- Slavery’s ‘lingering’ effects, reparations, and a hope of reconciliation

- Young Sufi women defy one tradition to preserve another

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Narrowing a respect gap that can make policing lethal

As the nation awaits a verdict in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin over the death last May of George Floyd, the list of police confrontations leading to citizen deaths in the United States grows – by three a day since that trial began March 29, reports The New York Times.

Often “lethal force incidents” involve a gun or the fear of one. That was the case in the March 29 police killing of Adam Toledo, a 13-year-old, in Chicago. Some share another characteristic.

“What I see sometimes is in these encounters with people of color, there is a different aggression,” Ron Johnson, a retired Missouri State Highway Patrol captain, told the Times. Mr. Johnson, who is Black, directed the police response in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 after an officer there killed Michael Brown.

“It’s because we don’t have these experiences and these understandings of each other. ... We don’t see them in the same human way that we see ourselves.”

Recasting encounters may help. Monitor special correspondent Martin Kuz wrote last week about the deployment of unarmed citizens as “violence interrupters” in Minneapolis. Stockton, California, has had success in easing tensions among residents with radically different backgrounds. While not immune to gun violence, Stockton has driven it down by 20% since 2018.

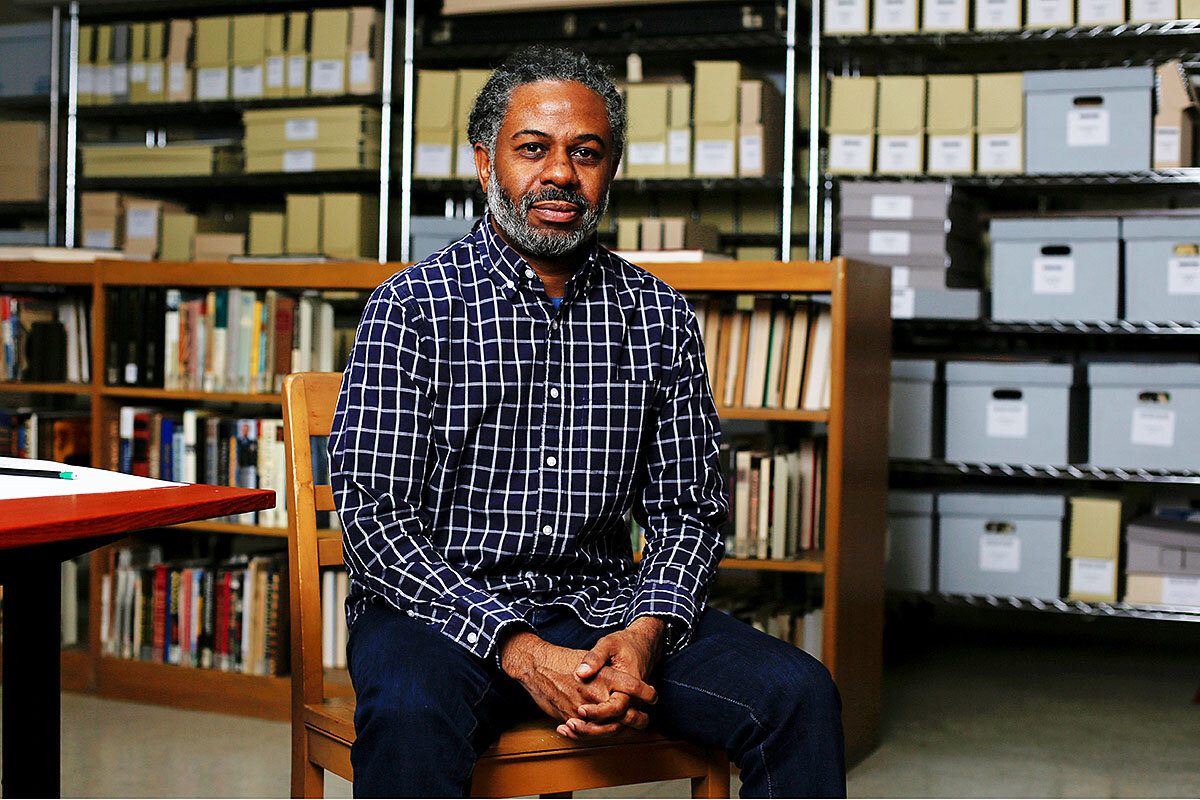

Khaalid Muttaqi is a leader of Advance Peace, a program that lets formerly incarcerated people build community relationships to help break the cycle that fuels both gun crime and the potential for deadly police encounters. His goal: to end the “othering” that breeds distrust.

“We see beyond the tattoos and saggy pants,” he told The Guardian, “to see humanity and potential in those deemed by law enforcement as being the most dangerous in the city.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

‘He has not bowed’: Jimmy Lai and Hong Kong’s future

The arc of a Hong Kong media magnate’s life parallels Hong Kong’s story. The power of his personal convictions may set up as a case study in how to face down an assertive global power – now and in the coming years.

Jimmy Lai has worn many hats in Hong Kong. As a preteen, he was a refugee fleeing the Communist mainland. He’s been an odd-job factory worker, a successful businessman, a media mogul, and one of Hong Kong’s loudest voices against encroaching control from Beijing. And now, he’s one of the highest-profile figures arrested under the new national security law – a bellwether for where China’s crackdown, and the pro-democracy movement, go from here.

But Mr. Lai himself isn’t going anywhere. A billionaire and British citizen, he could have left Hong Kong for a life in exile, friends and acquaintances say. He stayed. On Friday, he was sentenced to 14 months behind bars for taking part in two protests in 2019, during a mass movement to maintain and expand Hong Kong’s autonomy. The same day, his trial began for alleged violations of the sweeping national security law, which could see him jailed for life.

“He stands out as being the only really high-profile businessperson who has been unwavering in his support” for democracy in Hong Kong, says fellow activist Samuel Chu, whose father helped Tiananmen activists flee through Hong Kong to safety. “He’s not flashy,” says Mr. Chu. “He’s just a regular guy, who’s ready to go to jail.”

‘He has not bowed’: Jimmy Lai and Hong Kong’s future

Confined in a cell in the maximum-security Stanley Prison, its high walls and watchtowers perched above the rocky coast of Hong Kong’s Tai Tam Bay on the South China Sea, media magnate and democratic activist Jimmy Lai has come full circle.

Six decades ago, as a penniless boy of 12, he stowed away in the hull of a fishing junk and sailed over these same waters seeking haven in Hong Kong. Scrambling ashore, he “touched base” in the then British colony and was taken on as an odd-job worker at a garment factory, joining a flood of refugees fleeing famine and persecution in Communist-ruled China.

Mr. Lai, now a billionaire, credits Hong Kong’s freewheeling system – its laissez-faire capitalism, small government, rule of law, and basic freedoms – for giving him the opportunity to succeed. “Hong Kong ... made me what I am today,” he said in a speech late last year. “I came here with one dollar and the freedom here has given me the opportunity to build myself up.”

But today, for Mr. Lai and many others, Hong Kong’s beacon of liberty has dimmed. With Hong Kong no longer a safe harbor for free speech, more residents are seeking to escape, as China swiftly imposes mainland systems of authoritarian control on the territory – curtailing basic rights, silencing the democratic opposition, and jailing critics.

On Friday, Mr. Lai, long one of Beijing’s most prominent and outspoken detractors, was sentenced to 14 months behind bars for taking part in two peaceful, pro-democracy protests in 2019, during a mass movement to maintain and expand Hong Kong’s autonomy from Beijing. The same day, his trial began for alleged violations of Hong Kong’s sweeping new national security law, charges that could see him jailed for life.

Beijing has labeled Mr. Lai a traitor, a “black hand” behind the protests, and an “extremely vile anti-China element” – singling him out for censure with a handful of others. In a Friday article in the Party-run Qiushi magazine, senior Chinese officials responsible for the territory denounced Mr. Lai as the “backbone” of “chaos” in Hong Kong. On Sunday, the party mouthpiece People’s Daily hailed the sentencing of Mr. Lai and others as “the embodiment of justice.”

Mr. Lai, a Roman Catholic, knew this day was coming. As a wealthy British citizen, he had ample means to flee China once again, friends and associates say – this time for a life in exile. But he stayed. “He’s a man of integrity and sincerity. He doesn’t have to be in jail right now. He could have left the country,” says the Rev. Robert Sirico, a friend of Mr. Lai and his family for decades, and president of the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty.

Indeed, Mr. Lai has made clear that his choice is the culmination of political and religious convictions forged throughout his lifetime – and his overriding certainty that fighting for freedom, democracy, and the rule of law is not only essential for Hong Kong, but also for the rest of the world, as it confronts an increasingly assertive Communist Party leadership in China.

“The remarkable thing about Jimmy Lai is that he has not bowed,” says Mark Clifford, a director at Mr. Lai’s media company, Next Digital. “It's remarkable that one person has the courage to not buckle in the face of this extraordinary pressure by ... certainly one of the most authoritarian and repressive governments in the world.”

On April 3, Mr. Lai picked up a pen in prison and wrote a letter to the staff of Hong Kong’s Apple Daily, the newspaper he founded. “The situation in Hong Kong is becoming more and more chilling,” Mr. Lai wrote in the letter, published last week just before his sentencing. “It is time for us to stand with our heads high.”

Hong Kong success story

As Mr. Lai tells it, he was first drawn to Hong Kong by a taste of chocolate. Born Lai Chee-ying in Guangzhou in 1947, his wealthy family lost everything after the 1949 Communist Revolution and his mother was sent to a labor camp. At the age of 9, he was famished and working as a porter at a train station when a man tipped him with a bar of chocolate. He immediately bit in. “It was so tasteful. It was amazing,” Mr. Lai recalled in a talk years later. The man, he learned, came from Hong Kong. “Hong Kong must be heaven,” he told himself, determined to make his way there.

China was in the throes of the Great Leap Forward, a human-made disaster that saw tens of millions perish from famine, when Mr. Lai’s mother reluctantly allowed him to leave for Hong Kong in 1960. His hard work, ingenuity, and risk-taking – along with a personality that’s down to earth and a bit gruff – saw Mr. Lai rise rapidly at the garment factory. In 1981 he founded Giordano, a clothing retailer that rapidly expanded into an international chain, paralleling an economic boom in Hong Kong and China.

“He’s an archetypal Hong Kong success story,” says Mr. Clifford. Like Hong Kong, he was gregarious and pragmatic. He had a taste for collecting modern Chinese art, but never lost his common touch, say friends and colleagues. (Mr. Lai’s legal team declined a request for an interview.)

Mr. Lai taught himself English and embraced the ideas of free-market economist and liberal philosopher Friedrich Hayek, agreeing with his critique of socialism as he grew ever more troubled by Communist policies in China. Then came the euphoric 1989 student-led democracy movement in China and the brutal military crackdown on protesters in and around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4 that year.

After years of distancing himself from China, Mr. Lai was jolted into becoming an activist for democracy – and harsh critic of China’s Communist Party (CCP) leaders. Ever since, he’s backed the push for greater autonomy and freedom in Hong Kong, joining street marches and donating to pro-democracy political parties.

“He stands out as being the only really high-profile businessperson who has been unwavering in his support” for democracy in Hong Kong, says fellow activist Samuel Chu, whose father helped Tiananmen activists flee through Hong Kong to safety. “He’s not flashy,” says Mr. Chu, managing director for the Hong Kong Democracy Council in Washington. “He’s just a regular guy, who’s ready to go to jail.”

In coming years, Mr. Lai turned his entrepreneurial skills to the media business. “You deliver information, then you deliver choice, and choice is freedom,” he told the Acton Institute years later. He launched the successful Next magazine and then, in 1995, the Apple Daily newspaper, which quickly emerged as Hong Kong’s second largest. Another paper followed in Taiwan, and he set his sights on mainland China.

The splashy Apple Daily tabloid has been criticized for a sensationalist bent. But its award-winning journalists also engaged in muckraking that shook up the Hong Kong establishment, while endorsing democratic political change and criticizing China’s leaders. “They did this with an aggressiveness that garnered him ... a lot of enemies way before the political stuff was so serious as it is now,” says Mr. Clifford.

Growing suspicion

From Beijing’s perspective, Hong Kong’s ongoing democratic activism made it a potential base for subversion against the mainland – with Mr. Lai one of the chief instigators. Hong Kong kept memories of Tiananmen alive with large annual vigils on June 4, while waging one protest movement after another against Beijing’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s autonomy, and against failures to grant more representative government as promised when China resumed sovereignty over the territory in 1997.

Beijing began shutting down mainland Giordano stores in the 1990s, and Mr. Lai sold his large stake. On the media front, his publications faced an advertising boycott by large sections of the Hong Kong business community worried about offending Beijing. Mr. Lai endured physical threats, ranging from an assassination attempt to firebombs hurled at his home; he was tailed constantly, and photographers posted outside his house documented every visitor.

But Mr. Lai and Hong Kongers refused to stop speaking out. Hong Kong’s mass protests saw millions take to the streets against a proposed China extradition bill in the summer of 2019. Pro-democracy candidates won a landslide victory in local elections that November, followed by a big turnout the following July in an unofficial primary for selecting pro-democracy legislative candidates.

In an op-ed in September 2019, Mr. Lai said Hong Kong was standing up to China’s authoritarianism and urged the United States to confidently promote individual liberty. “The world will never know genuine peace until the people of China are free,” he wrote in The Wall Street Journal, arguing against appeasement of the Asian economic giant. “In all your dealings with China ... remember we are fighting your battle.”

Then came the pandemic, and China’s crackdown on Hong Kong, which was swifter and more sweeping than Mr. Lai or many others expected. The national security law that Beijing imposed on Hong Kong was passed June 30, 2020, amid warnings from critics that it would severely erode the territory’s judicial independence. Pro-democracy legislators and activists were rounded up in waves of arrests. In August, Mr. Lai was led away in handcuffs as police raided Apple Daily. Other leading pro-democracy figures arrested and recently sentenced along with Mr. Lai include barrister Martin Lee, known as the “father of democracy” in Hong Kong, who helped draft its mini-constitution.

“These veterans have been sores in Beijing’s eyes for so long,” says Victoria Tin-bor Hui, associate professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame. “For Beijing, it’s mission accomplished. They are making Hong Kong safe for the CCP.” In March, Beijing approved an overhaul of Hong Kong’s legislative system to ensure only “patriots” could govern.

Mr. Lai’s case is setting precedents under the national security law, activists say. Charged with colluding with foreign forces – based in part on articles he wrote and interviews he gave – Mr. Lai applied for bail but was refused, in an unusual court decision for Hong Kong. “That is not by accident,” says Mr. Chu. “He is the one who said, ‘Let me be the tip of the spear.’”

“Jimmy Lai is clearly the victim of judicial harassment,” says Cédric Alviani, East Asia bureau head for Reporters Without Borders. “He’s become the symbol of Hong Kong press freedom that the Chinese regime has decided to take down,” sending a message “to all media professionals that you are not immune.”

“You cannot publish information that the Chinese regime doesn't want to be published,” he says. “This is a message that freedom of the press is not whole anymore in Hong Kong.”

Like other activists, he questions how long Apple Daily can survive, as “one of the last remaining voices of opposition to the Chinese regime.”

Hong Kong’s future

The crackdown has forced the Hong Kong democracy movement to adapt from one of vocal protest to quiet resistance, as most activists lie low, brainstorming new strategies, while a small number flee overseas to continue their struggle, says Willy Wo-Lap Lam, adjunct professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and an expert on Chinese politics.

Some analysts say while Mr. Lai’s choice to stay was admirable, he could have better aided the movement by escaping.

“One must admire and respect somebody like Jimmy Lai,” who’s lived under communism and knows “the party will be very harsh on him when it comes for him,” says Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London.

“I would also say from the other side, that it was really very unwise on his part,” he says. “He could have taken most of his money out of Hong Kong and ... enabled the resistance to last much longer.”

Still, Dr. Tsang concludes, “give the man the benefit of the doubt. Whatever he is ... he is not naive.”

Many activists believe Mr. Lai’s refusal to back down personifies to the world Hong Kong’s strong spirit in resisting Beijing’s repression. “Hong Kong belongs to the world and we are not going to let this die,” says Mr. Chu. “You make martyrs of people like Jimmy and Martin and Joshua [Wong] and Agnes [Chow] and they become even more relevant and powerful.”

Mr. Lai’s decisions underscore the steadfastness of Hong Kong’s opposition, experts say. “Beijing's ... strategy seems to be, beatings will continue until morale improves. I suspect Beijing will soon discover that many, many, many beatings later, morale has still not improved,” says Alvin Cheung, a Hong Kong barrister and university lecturer now at New York University. “There's a very real possibility that there will still be acts of underground resistance.”

In his recent letter from prison, Mr. Lai wrote that he is at peace and sustained by his faith, reading the Bible, praying, and exercising daily.

In a talk last fall with the Catholic Napa Institute, he said he could never renounce his values, even if it means years in prison. “I am what I believe; if I cannot change it, I have to accept my fate with grace.”

Why Iran nuclear talks are moving ahead, despite Israeli attack

Retaliate or negotiate? After the bombing at its nuclear enrichment site, Iran seemed to have a tactical choice. Its decision, to do both, indicates a strategic commitment to diplomacy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The Israeli attack on an Iranian nuclear enrichment site came as diplomats signaled progress in talks to bring the United States and Iran back into compliance with a landmark nuclear deal. It presented Iran with a choice: retaliate for yet another act of sabotage against its program, or negotiate, in favor of a diplomatic solution that could bolster its regional standing and lower the risk of war.

Iran is pursuing both. It is raising uranium enrichment to the unprecedented level of 60% purity. And Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, overruled other hard-liners calling for Iran’s negotiators to “come home.” Talks in Vienna resumed Monday and reportedly reached a “drafting” stage.

The Natanz attack “was an attempt by Israel to sabotage not just Iran’s nuclear program but the nuclear talks in Vienna, or at least deprive Iran of its leverage at the table,” says Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group.

“Some in Israel could conclude that this was a cost-free blow to Iran’s nuclear program for Israel,” says Mr. Vaez. “The reality is that the strategic message that Iranians are sending with 60% enrichment is that the only thing that curtails Iran’s nuclear program is a win-win diplomatic outcome.”

Why Iran nuclear talks are moving ahead, despite Israeli attack

Even Iran’s scientists were impressed by the elegant effectiveness of the latest Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear program. An explosion in the underground tunnel carrying both primary and backup electricity cables at its Natanz enrichment site last week cut off power to thousands of centrifuge machines as they spun uranium gas at supersonic speeds.

“The enemy plotted the Natanz attack very beautifully, from the scientific point of view,” admitted Fereydoun Abbasi-Davani, the former head of Iran’s nuclear agency, and survivor of a 2010 Israeli assassination attempt.

The attack came as diplomats in Vienna signaled progress in talks to bring the United States and Iran back into compliance with a landmark nuclear deal, three years after then-President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the U.S. from it. Israel rejects that 2015 deal – and any return to it – which imposes strict limits on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for lifting harsh sanctions.

The Natanz attack presented Iran with a stark choice: To retaliate, in line with fiery rhetoric that has followed every high-profile incidence of sabotage against Iran’s nuclear program, nearly all attributed to Israel. Or to negotiate, in favor of a diplomatic solution that could bolster Iran’s regional standing and lower the risk of war.

Iran’s choice appears to be to pursue both pathways, simultaneously. It is fighting back by raising uranium enrichment to the unprecedented level of 60% purity – three times higher than its previous high point, and technically a short step from the 90% level necessary for fissile material to make an atomic bomb.

And Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, while denigrating U.S. diplomatic offers, last week overruled other hard-liners calling for Iran’s negotiators to “come home” and authorized talks to resurrect the deal to continue.

“The answer to your evilness,” said President Hassan Rouhani, is the boost in enrichment. “Even today, if we wish, we can enrich uranium at 90% purity. But we are not seeking a nuclear bomb,” he said Thursday. “If others return to full compliance with the deal ... we will stop 60% and 20% enrichment.”

Iran’s strategic message

Analysts said that, however much the Israeli attack slowed the Iranian production of enriched uranium, the benefits to Israel would be short-lived.

The Natanz attack “was an attempt by Israel to sabotage not just Iran’s nuclear program but the nuclear talks in Vienna, or at least deprive Iran of its leverage at the table,” says Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group.

“Because Iran is unable to retaliate in kind [inside Israel] right now, some in Israel could conclude that this was a cost-free blow to Iran’s nuclear program for Israel,” says Mr. Vaez. “The reality is that the strategic message that Iranians are sending with 60% enrichment is that the only thing that curtails Iran’s nuclear program is a win-win diplomatic outcome. Sanctions and sabotage would only result in Iran further ratcheting up its nuclear program.”

Meanwhile, signs of a modest kinetic reaction include five rockets fired Sunday at an Iraqi military base housing American contractors, a frequent tactic of Iran-backed militias. And an Israeli-owned cargo ship was struck by a missile last Tuesday off the coast of the United Arab Emirates – the latest in a series of tit-for-tat Iran-Israel attacks on each other’s ships.

Talks in Vienna resumed Monday and reportedly reached a “drafting” stage, despite a lingering dispute over who should move first. President Joe Biden has stated a desire to return to the nuclear deal, known as the JCPOA, as a starting point to address issues such as Iran’s expanding missile capability and the influence of Iran-backed militias. The U.S. insists that Iran take the first steps.

Iran says that, since it was Mr. Trump who departed the deal, the U.S. should act first to remove sanctions. Iran would then reverse its own breaches of the JCPOA by reducing its stockpile of low-enriched uranium, capping enrichment again at 3.67% purity, and ending work on advanced centrifuges.

Iran wants to signal it “still has a lot of options for strengthening its hand, and time is not on the U.S. side,” says Mr. Vaez. “That is the most important message they want to send to Washington. If the U.S. drags its feet and refuses to do what the Iranians believe is right – which is to lift all the sanctions – the Iranian nuclear program will grow exponentially.”

Exhibit A is, for the first time, the laboratory production of small quantities of 60% enriched uranium – measured in grams, not kilograms.

Diplomatic process

While decrying the result of the Israeli attack and its implications for Iran’s security, Alireza Zakani, a hard-line lawmaker, signaled that the cycle of move and countermove is also part of the diplomatic process.

The attack “destroyed a tremendous portion” of Iran’s enrichment capacity, caused lawmakers to “cry blood” over the loss of “thousands” of centrifuges, and is further proof the country has become a “paradise for spies,” he said.

“The Natanz sabotage is part and parcel of the negotiations,” he added. The U.S. and Israeli message is, “if you refuse to shut down your nuclear program, we will shut it down on our own.”

That message has been sent multiple times, as the decadeslong covert war between Israel and the Islamic Republic has expanded. Israel all but claimed responsibility for the assassination in November of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, one of Iran’s top nuclear scientists, widely believed to be in charge of a clandestine Iranian weapons program until it was stopped in 2003.

In response to that killing, Iran boosted uranium enrichment to 20% purity.

A previous explosion at Natanz last July did extensive damage to buildings. And Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has trumpeted an August 2018 Mossad raid on a Tehran warehouse that spirited away an archive of tens of thousands of pages about Iran’s past nuclear efforts.

In Iran, the Natanz blackout sparked criticism of the intelligence and security community over “the Israel within,” which appears to flourish unchecked. Even the Revolutionary Guard, whose tasks include protecting nuclear sites, came under fire for producing a popular spy thriller TV series called “Gando” that takes jabs at Mr. Rouhani’s centrist government – at the expense, the critics said, of real counter-espionage prowess.

“How is it possible that we are never able to identify those infiltrators?” asked the pro-Rouhani Khabar Online news agency. “While we are preoccupied with making ‘Gando’ and imposing filtering on our internet users, the enemy is staying closer to us than we can imagine.”

An expanding program

Despite the chain of security lapses, Iran’s nuclear program has expanded, sometimes swiftly.

“Whatever has been done against Iran hasn’t worked, including blowing up Natanz,” says Mohammad Ali Shabani, editor of the Amwaj.media website. Nearly 20 years ago, he notes, Iran “begged” the European Union and Americans to permit laboratory enrichment, with just a few cascades of centrifuges. They refused.

And for years, enrichment above 20% purity was considered an Israeli red line likely to trigger an air assault, of the kind Israel launched to stop nuclear programs in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and in Syria.

Today Iran is “pushing to 60%, they are moving towards a clear virtual nuclear capability,” says Mr. Shabani. “The reality is, right now in Iran, it’s only a political decision [preventing Iran] from building a bomb.”

Such a political decision is meant to be reaffirmed at the nuclear talks in Vienna. But even if they fail, the successful attacks inside Iran carry their own lesson.

“There is no doubt that this program is deeply penetrated by Israeli intelligence,” says Mr. Vaez at the International Crisis Group.

The string of assassinations, cyberattacks, and explosions “clearly demonstrate that the option for Iran of dashing towards nuclear weapons is nonexistent because ... if Iran ever decides to move in that direction, it will probably be stopped way before it’s able to achieve critical capacity.”

Q&A

She’s seen peacekeeping fail. Here’s her advice on getting it right.

Peacekeeping missions are often driven by international agendas. We spoke with an author who suggests that they might work better if they focused more on local people and their concerns.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why do peacekeepers so often fail to keep the peace? That’s a question Séverine Autesserre has been exploring for years – first as a humanitarian worker, and later as a researcher.

But Dr. Autesserre’s new book changes tack. Where and why is peacekeeping succeeding? In “The Frontlines of Peace: An Insider’s Guide to Changing the World,” she writes that places avoiding conflict against all odds have something in common. They have peacekeeping efforts led by locals.

“There’s often a belief that only outsiders have the required skills and expertise to build peace,” she says. But from Colombia to Chicago, she found, peace succeeded when “everyone, truly everyone, was involved, including the poorest and the least powerful members of the community.”

That principle, she argues, should reshape the way international organizations do business. “They need to ask, not assume,” she explains. “They need to follow, not lead. They need to support, not rule.”

In this interview, the Monitor’s Ryan Lenora Brown speaks with Dr. Autesserre about conflict, peace, and, as she puts it, why “all of us can change the world.”

She’s seen peacekeeping fail. Here’s her advice on getting it right.

Every year, the world invests billions of dollars in peacekeeping. Peacekeepers patrol war zones. World leaders pledge an end to the fighting.

And yet, around the globe, violent conflict persists. More than a billion people live in a conflict zone. The past five years have witnessed the world’s worst refugee crisis since World War II. Wars cost the world about $10 trillion annually, or $4 a day, every single day, for every person on earth.

Séverine Autesserre, a professor at Barnard College, Columbia University, has spent much of her career trying to understand why. First as a humanitarian worker for organizations like Doctors Without Borders, and later as an academic researcher studying the peacekeeping industry, she watched as efforts to make lasting peace stumbled again and again, from Kosovo to Congo to Palestine.

In her new book, “The Frontlines of Peace: An Insider’s Guide to Changing the World,” Dr. Autesserre decided to ask a new question. Much was going wrong, that was clear. But what was going right? She discovered that around the world, from Medellín to Baltimore, peacekeeping tended to work best when it was led by locals and organized at the grassroots.

Q: You’ve written a lot in your career about how and why peacekeeping efforts in war zones keep failing. What made you decide to devote a whole book to what’s working?

What I set out to do was write a book about hope. It’s a book about how each and every one of us can change the world. I know, personally, intimately what violence does to an individual. I experienced that as a kid and it really shaped my whole being. So I’ve devoted my life to countering violence in all its forms. And the thing is that violence is widespread. Today, when you look at the number of people who live under the threat of violence, you see that it’s more than 1.5 billion, in more than 50 conflict situations around the world. And even when you look at countries that we think of as peaceful countries like the United States, we see that they face an increasing number of violent acts like hate crimes, gang fighting, and terror attacks. So to me, it’s really critical that we do something about it.

Q: In your experience, why do internationally led peacekeeping efforts so often fail?

Governments, diplomats, and peacekeepers often fail at improving the situations in war-torn countries, in gang-ridden neighborhoods, at sites of mass violence, because they use the conventional way to build peace. That relies on presidents, governments, rebel leaders, and foreign peace builders based in capital cities and headquarters, and usually it excludes local activists and ordinary people. It’s something we’ve seen all over the world, in Afghanistan, in Congo, in Colombia, in Iraq, many other places. There’s often a belief that only outsiders have the required skills and expertise to build peace.

Q: You write about how in your work in the humanitarian sector, you saw a wide variety of places where people were making peace work against the odds. What did those situations have in common?

The main common thread in all of the stories I tell in the book is that the residents have achieved peace thanks to grassroots, bottom-up efforts. Everyone, truly everyone, was involved, including the poorest and the least powerful members of the community. And they all built on their specific, unique local history, politics, and cultures and circumstances.

Q: Can you give us an example?

My favorite is the story of Idjwi, which is quite literally an island of peace in the Democratic Republic of Congo. For the past 20 years, one of deadliest conflicts since World War II has raged around Idjwi. Despite the fact that one of the largest and most expensive United Nations peacekeeping missions in the world is present and active in Congo, several million people have died. Hundreds continue to die every day. But for the past 20 years, Idjwi itself has avoided mass violence.

It’s located right at the border between Congo and Rwanda, two countries that have been at war regularly since the 1990s. It also has mineral resources, ethnic tensions, lack of state authority, extreme poverty, local conflict over land and traditional power, and many other features that have caused mass violence in neighboring provinces. But the island is peaceful because of the active, everyday involvement of all of its citizens, including the poorest and the least powerful ones. They do this by fostering what they call a culture of peace, by organizing in grassroots associations and local structures that help resolve conflicts. And by drawing on strong beliefs that have detoured violence by both insiders and outsiders, such as blood pacts – traditional promises between families not to hurt each other. And it works.

Q: You make the argument in the book that it’s not the case that international organizations need to get out of the way entirely. They just need to do their work differently. What do you think, ideally, would be the role of international institutions in peace building?

The short answer to this is: They need to ask, not assume. They need to follow, not lead. They need to support, not rule.

Q: A lot of the places you write about in this book might feel far away to its readers. But you argue that the same kinds of peace-building methods can be used in the United States. Can you talk a bit more about this?

There are three specific things that I think all of us in the United States can learn from the inhabitants of war-torn countries so that we can help combat extremism and violence in our own communities. To start, we can develop informal relationships with our opponents, whether these are political, religious, or cultural opponents.

The second big idea is that we can all use the elements of our own local cultures to help smooth out tensions. Do you know the story of the association called Mothers Against Senseless Killings in the South Side of Chicago? There was a group of women who were really fed up with seeing so much bloodshed around them. So they decided to just hang out on street corners. They brought folding chairs, and they sat on them for hours and hours. And the thing is that in Chicago, nobody wants to kill someone in front of their own mothers, so over time, the number of shootings in the community has decreased a lot.

The last crucial thing we can all do is support grassroots, bottom-up associations with time, money, effort, whatever we can spare. Of course, our new administration and Congress also have an important role to play because we all know that real peace lasts only when it’s built both from the top down and from the bottom up. But the important point is that all of us can help. All of us can change the world.

#TeamUp

Slavery’s ‘lingering’ effects, reparations, and a hope of reconciliation

Our commentator admits that she hadn’t given the idea of reparations much thought until discussions moved them into the national spotlight. Here, she wrestles with the distinctions between repair, remedy, and restitution.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Jacqueline Adams Correspondent

Although I have long known that I am a descendant of slaves, I never gave much thought to reparations. But recently my consciousness has been raised.

It started with a February talk by Nikole Hannah-Jones, whose 1619 Project won a Pulitzer Prize. She described reparations as “a societal debt owed because of the racial apartheid that has been practiced.”

Then she added, “We are obligated to fight for progress that we don’t think we are really going to see.”

That got my attention. I still don’t expect to see a reparations check in my mailbox, but I am no longer ignoring the issue.

And now that I’m paying attention, I’m seeing a number of important developments, from Jesuit priests pledging to raise $100 million for the descendants of people enslaved by the Roman Catholic order to the City Council in Evanston, Illinois, offering reparations to Black residents whose families faced discriminatory housing practices. Other cities, religious orders, and a few schools are looking at reparations, too.

At a minimum, a conversation has begun. I hope it leads to a national truth and reconciliation process on the impact and aftermath of slavery. Perhaps that could help us begin to bridge our bitterly partisan and demographic divides.

Slavery’s ‘lingering’ effects, reparations, and a hope of reconciliation

According to family historians on my mother’s side, my great-grandfather Louis Thompson was born into slavery in 1844. He was described as a mulatto, meaning that he was a product of the rape culture of the time. It was a common practice for slave owners to rape the women they owned. One result was the creation of additional wealth in the form of their own offspring. Yes, it is a horrific concept. And, no, there is no way to count how many times this particular crime of rape should be added to the crime against humanity named slavery.

After the Civil War, my great-grandfather acquired land in Louisiana where my grandmother was born. After college, she became a teacher. Her husband, my grandfather, earned his doctor of veterinary medicine degree at Ohio State University. Education, excellence, and hard work have been the hallmarks of my family through the generations.

Although I have long known that I am a descendant of slaves, I never gave much thought to reparations. African Americans never received the promised “40 acres and a mule” during Reconstruction. And although prominent thinkers, writers, and legislators have long promoted reparations, I considered the notion pie in the sky, so I didn’t waste time thinking about it.

But over the last few months, my consciousness has been raised.

“A societal debt”

At the end of February, I heard a talk by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her landmark 1619 Project in The New York Times. She set my mind whirring when she described the Founding Fathers as “liars who didn’t believe in the values they touted.”

Ms. Hannah-Jones prompted me to do some research. She said that 10 of the first 12 U.S. presidents had been slave owners. That’s true, but the full list is longer. Among the first 12, Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor were slave owners, eight of them while in office. The remaining two, John Adams and John Quincy Adams, never owned slaves. Among later presidents, Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant were also slave owners.

Decades later, President Woodrow Wilson instituted practices that made it much more difficult for Black workers to overcome the economic impact of slavery. Specifically, he oversaw the segregation of much of the federal workforce, including the Treasury Department and the U.S. Postal Service. The dismissal of Black civil servants, their reassignment to lower-paying positions, the separation of work areas and facilities according to race, and a decrease in the hiring of Black employees rolled back economic progress with lasting effects on the Black community.

Noting that “anti-Blackness is foundational to the United States,” Ms. Hannah-Jones said, “Reparations from the U.S. government are a societal debt owed because of the racial apartheid that has been practiced.”

Then she added, “We are obligated to fight for progress that we don’t think we are really going to see.”

That got my attention. I still don’t expect to see a reparations check in my mailbox, but I am no longer ignoring the issue.

Reparations under discussion – and underway

Now that I’m paying attention, I’m seeing a number of important developments. Driven in part by Georgetown University’s history, Jesuit priests pledged in mid-March to raise $100 million for the descendants of people enslaved by the Roman Catholic order.

Also last month, the City Council in Evanston, Illinois, voted to offer reparations to Black residents whose families suffered from discriminatory housing practices. Evanston has committed $10 million over a decade to the effort, with the first $400,000 in payments going to a small number of eligible Black residents for home repairs, down payments, or mortgage payments.

Reuters reported on a plethora of initiatives in varying stages of consideration in cities ranging from Burlington, Vermont, to Asheville, North Carolina. A few Episcopal dioceses and a handful of universities have committed to reparations, too.

Critics have argued that, unlike the Evanston plan, the preponderance of reparations payments should go to individuals, not banks or contractors, to eliminate the racial wealth gap that descendants of slaves have endured. And we now have some sense of the size of that gap. Last summer, Citi Global Perspectives & Solutions calculated $16 trillion in lost gross domestic product over the past 20 years because of gaps between African Americans and whites in wages, education, housing, and investment.

But cash payments won’t correct the systems that perpetuate these gaps.

“Lingering negative effects”

My reading has made me wonder what reparations can and should repair. Are they a remedy for systemic racism? If so, they should target specific government programs and policies. Or are they a form of restitution for the crime of slavery? Many argue that the cost of the latter would be too many trillions to pay. However, we have two recent examples as precedents. Germany has paid some $91.9 billion to countries and people harmed by the Holocaust. And in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed legislation authorizing $1.25 billion to be paid to the survivors of the 120,000 Japanese Americans interned during World War II – $20,000 per person. Another suggestion that might be easier to implement would be exempting several generations of African Americans from paying federal income taxes.

On Wednesday, a House committee approved H.R. 40, which would create a Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans. The 25-17 vote fell along party lines, with Democrats in the majority; no time has been set to bring the legislation to the floor for a vote. The bill charges the commission with identifying the following:

- Federal and state governments’ role in supporting slavery

- Public and private discrimination against freed slaves and their descendants

- “Lingering negative effects of slavery” on Black people and society

On the one hand, President Joe Biden says he supports the idea of studying reparations. On the other, aren’t commissions the places where good ideas are sent to die?

There is no way to know yet how or whether any of the nascent reparations efforts will mature. What is beginning to happen, though, is real consideration of too-long-ignored realities. At a minimum, a conversation has begun in earnest. And I hope that conversation leads to something the U.S. has never had, a national truth and reconciliation process on the impact and aftermath of slavery.

That type of process has brought some measure of healing to South Africa and Northern Ireland. Perhaps it could help the United States begin to bridge our bitterly partisan and demographic divides.

Jacqueline Adams is co-author of “A Blessing: Women of Color Teaming Up to Lead, Empower and Thrive.”

In Pictures

Young Sufi women defy one tradition to preserve another

Sometimes a revival calls for reinvention. This photo essay shows where young women keep musical traditions alive by defying old cultural norms about who can perform.

-

By Adil Amin Akhoon Correspondent

-

Sharafat Ali Correspondent

Young Sufi women defy one tradition to preserve another

Every morning, a small house in northern Kashmir reverberates with traditional Sufi melodies. A small group of female musicians play their instruments soulfully – as if they were performing a hymn or a prayer.

In Sufism, a form of Islamic mysticism, this music is food for the soul. Its origins in Kashmir trace back to the 15th century. But today, with few traditional artists left in the valley, these players represent a ray of hope for Sufi music’s revival. While their peers may be more into rock and rap, these musicians are holding on to their roots.

For centuries, the tradition was passed down from one man to another. But sisters Irfana and Rihana Yousuf began to play with support from their father, Mohammad Yousuf. A musician himself, he sometimes had to sell household items to afford the costly instruments so they could keep their dream alive – and his.

The sisters created a group to teach other girls from the neighborhood. Some players stopped coming to practice, pressured by those who felt Sufi music belongs to men. But they’ve found their way back, drawing inspiration from each other as they juggle music, chores, and school.

Some are studying music at the University of Kashmir, and documenting Sufi compositions so that they’re easier for beginners to learn and preserve. And their doors are open to whoever shares their passion.

We’ve been experimenting with the presentation of our photo essays online and in the Monitor Daily. What do you think? Share feedback with the photo team at csmphotoeditors@csmonitor.com.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A bellwether on corruption in Latin America?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The pandemic has interrupted a remarkable streak in Latin America – a popular assault on corruption. Since 2015, an upwelling of demand for honest governance felled hundreds of the region’s corrupt elite. COVID-19 has put the focus elsewhere.

That streak, however, continues in at least one country. In Ecuador, a presidential election resulted in a victory for Guillermo Lasso, a former banker who promises independence for judges and prosecutors. His opponent in the April 11 election, Andrés Arauz, was easily tied to a former president, Rafael Correa, who was convicted of bribery last year and given an eight-year sentence.

“Lasso gives a sensation of tranquility, of stability, and of independence of branches and institutions that has allowed the prosecution to start to act almost immediately,” said Mauricio Alarcón, head of the transparency watchdog Citizenship and Development Foundation.

Mr. Lasso says he will seek international help to combat organized crime in Ecuador. “There will be no impunity,” he promised. With the end of the pandemic in sight, this small country of 17 million people may be showing that Latin America is not done yet with lifting up its standards and electing leaders with clean hands.

A bellwether on corruption in Latin America?

The pandemic has interrupted a remarkable streak in Latin America – a popular assault on corruption. Since 2015, an upwelling of demand for honest governance felled hundreds of the region’s corrupt political and business elite. COVID-19 has put the focus elsewhere.

That streak, however, continues in at least one country. In Ecuador last week, a presidential election resulted in a victory for Guillermo Lasso, a former banker who promises independence for judges and prosecutors when he takes office next month. His opponent in the April 11 election, Andrés Arauz, was easily tied to a former president, Rafael Correa, who was convicted of bribery last year and given an eight-year sentence. (Mr. Correa fled to Belgium to avoid prison.)

Mr. Lasso, who “believes in good ideas and not ideologies,” was able to tap into public anger at scandals over purchasing medical supplies during the pandemic. And voters were reminded again last week of the need to root out corruption with the arrest of a former boss of the state-owned oil company, Petroecuador.

“Lasso gives a sensation of tranquility, of stability, and of independence of branches and institutions that has allowed the prosecution to start to act almost immediately,” Mauricio Alarcón, head of the transparency watchdog Citizenship and Development Foundation, told Bloomberg News.

Compared with other countries in Latin America, Ecuador’s news media and watchdog groups are above-average in monitoring graft, according to the 2020 Capacity to Combat Corruption Index. In addition, Attorney General Diana Salazar is a model in the region for integrity and for going after graft in high places. Since 2012, the country has significantly improved its standing in a global corruption index.

Still, a 2019 survey by Transparency International found perceptions of corruption remain high. Nearly 1 out of 4 people say they were victims of corruption. Nearly two-thirds believe more than half of Ecuador’s politicians are corrupt. And in last week’s election, about 1 in 5 voters refused to vote despite laws that make voting mandatory.

Mr. Lasso says he will seek international help to combat organized crime in Ecuador. “There will be no impunity,” he promised. With the end of the pandemic in sight, this small country of 17 million people may be showing that Latin America is not done yet with lifting up its standards and electing leaders with clean hands.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A new view of normal

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Linda Kohler

Is there such a thing as a “normal” that is certain and consistently good? In a word, yes – and we find it in God.

A new view of normal

We long for constancy in our lives. So it’s not unusual to hear someone speak with trepidation about a “new normal.” Whether this comes from an impatience to get back to “normal” or a concern that there is no going back to the old “normal,” it begs the question, What really is “normal”? Can there ever be a “normal” that is certain and consistently good?

Mary Baker Eddy, in her pioneering works on spirituality and healing, put forward what some would consider a rather unconventional view of constancy. A search for the word “normal” in her extensive writings uncovers several concepts she apparently considered fundamental facts of existence: Health is normal. Harmony is normal. Good is normal. (See, for example, “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 200.)

Looking around and seeing the news, one might not necessarily reach the same conclusion. In fact, in her own life, Mrs. Eddy faced considerable illness, loss, and hardship. And yet, she grew to view these experiences not with resignation, but with a spiritual conviction that health, harmony, and good are in fact normal, natural, and inevitable. This conviction was based on an understanding of good as the very definition of God. She writes of God as divine Principle – consistent, universal, changeless good – and of the true identity of each of us as spiritual, made in God’s image, as the Bible says. It follows that illness, discord, accident, and injustice have no standing in this spiritual creation. Here is a “new normal” to be reckoned with!

Acknowledging and understanding God, and then living in obedience to divine Principle, changes us from the inside out. It brings hope and healing. Our sense of what’s normal shifts – not from moderate to extreme or from bad to worse, but from a view of good as uncertain to a perspective that good is real, secure, and dependable. We are made new every day, but this newness isn’t jarring or unsettling; it brings peace and stability to our lives.

Christ Jesus urged his listeners to adopt a new view of normal. Many of the people he healed, people who may have become resigned to living with pain or incapacity (a very unwelcome new normal), found that not only were they physically whole, but their hearts were awakened.

Jesus encouraged people to no longer be content just to live for themselves, just to grind out a living. In the words of one adherent of Jesus’ teachings, the Apostle Paul, “Don’t let the world around you squeeze you into its own mould” (Romans 12:2, J. B. Phillips, “The New Testament in Modern English”). Jesus’ words and example challenged his followers, including us, to “love one another as I have loved you,” and to “heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out demons. Freely you have received, freely give” (John 15:12; Matthew 10:8, New King James Version).

This love was put to the supreme test when Jesus willingly faced and overcame the crucifixion. His resurrection overturned the world’s concept of normal. It set his disciples on a new path. “His resurrection,” Mrs. Eddy writes, “was also their resurrection. It helped them to raise themselves and others from spiritual dulness and blind belief in God into the perception of infinite possibilities” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 34).

Jesus’ resurrection took three days. The disciples’ took longer. Jesus met with them several times over the course of many days after his resurrection. He comforted them, counseled them. And yet, Peter apparently still had reservations about whether he had what it took to carry on the work. He reverted to his old normal – he went fishing. But Christ would not let him settle for less than a full resurrection from “spiritual dulness and blind belief.” The risen Jesus continued to counsel Peter until he was prepared to accept a completely new view of life, a completely “new normal,” and his new role in sharing Christ-healing with the world.

As we awaken to the reality of Life and Love as God, we discover the continuity and stability of a true, God-created normal, right here with us, totally uninterrupted, no matter what seems to be going on around us. We understand more and more how we can experience normal – not the normal of “back to our regularly scheduled materiality” but the spiritual normal of experiencing and expressing ever-present, all-encompassing, unselfed divine Love.

Adapted from an editorial published in the April 19, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Sunrise silhouette

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow. President Joe Biden has made addressing climate change a major focus of his infrastructure plan, which puts workforce gains front and center. We’ll size up the green-job opportunities.