- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In a roiled Minneapolis, schools are testing new model for safety

- How one Chinatown curbs anti-Asian violence and unites a city

- Worse than the Cold War? US-Russia relations hit new low.

- In South African architecture, women build on social justice

- Jewish women spied, smuggled, and sabotaged under the Nazis’ noses

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Justice and rejuvenation

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

As the verdict in the Derek Chauvin trial was read out Tuesday afternoon, a tide of emotion swept through those gathered in front of the Minneapolis courthouse: relief, resolve, hope. But among them all, perhaps one was most conspicuous: rejuvenation.

Monitor photographer Ann Hermes is there, and as I talked to her amid honking car horns and shouts of solidarity, she noted that the mood was not happy. George Floyd is dead, and there is no joy in imprisoning the police officer now convicted of murdering him. Rather there was a sense that, at last, a historic moment of racial tension has resolved in justice for the Black community. And that only adds energy to a movement that now feels – just maybe – a nation might be truly listening.

Tomorrow, we’ll begin our coverage of what the verdict means for race relations in America. And among those pieces will be a photo essay by Ann in which she hopes to capture this rejuvenation. In years of covering such events, she has never before seen such a resolve among community groups to push on, to be heard. And today that cascaded through the streets of Minneapolis. “There were a lot of tears,” Ann says, “but it was energizing. A verdict finally went in a direction they were hoping for.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

In a roiled Minneapolis, schools are testing new model for safety

Students in Minneapolis are at the epicenter of the police-free schools movement. Amid high tensions, the model of moving toward a new culture of safety within schools is being tested and, some say, strengthened.

In Minneapolis, many students and teachers say they have felt on edge after the murder of George Floyd. On Tuesday, a Minneapolis jury found former police officer Derek Chauvin guilty on all counts. Students are among those who have been protesting in nearby Brooklyn Center. There, the night before high schools resumed in-person classes last week, Daunte Wright, a former Minneapolis Public Schools student who is Black, was shot and killed by a white police officer.

For the school district in the middle of this, the events of the past year have required a rethinking about safety. The MPS school board voted last year to end its contract with the police department, and has swapped school resource officers for a cadre of civilian safety specialists. It’s one model for keeping students safe and reflects the steps being taken by a shaken city as it seeks to embrace justice and fairness in its institutions.

“For a lot of people, what happened on May 25 is still in their head every minute of every day,” high school senior Nathaniel Genene says, referring to the day Mr. Floyd died.

In a roiled Minneapolis, schools are testing new model for safety

Update: A Minneapolis jury found Derek Chauvin guilty of all charges in the murder of George Floyd on Tuesday afternoon.

When Nathaniel Genene walked into his Minneapolis high school last week for the first time in over a year he quickly noticed that there was no uniformed police officer standing watch.

“Usually when you walk in SROs are the first thing you see and the last when you walk out,” he says, using the abbreviation for school resource officers.

Mr. Genene, a senior at Washburn High School, served as the citywide student representative on the Minneapolis school board last year. He helped push the board to cut ties with the city’s police department last June in the wake of the death of George Floyd in police custody. Other school systems, including in Portland, Oregon, and Denver followed suit, sparking a wave of districts reconsidering whether officers belong in schools.

In Minneapolis, where police department contracts with Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS) date back to the 1960s, a new cadre of civilian safety support specialists is now in place. And despite challenges here from events outside school doors – the trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin, the death of Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in nearby Brooklyn Center – some students and staff say that the security culture is slowly becoming strengthened by being more inclusive of students who have asked to remove officers for years.

It’s a window on one model for keeping students safe and reflects the steps being taken by a shaken city as it seeks to embrace justice and fairness in its institutions. It also comes with its own share of controversy, with several principals writing in an open letter that students had been placed in “grave danger” and that the school board had “burned a fragile bridge” by viewing the entire police department in a negative light.

MPS leaders are “responding to calls from students and community, which is really important,” says Katie Pekel, a former principal and director of the Minnesota Principals Academy at the University of Minnesota. She points to research indicating students, especially from historically marginalized groups, view SROs less favorably than administrators.

In Minneapolis in particular, the relationship between students and the police can be complicated. Many students and staff say they have felt on edge during the trial of Mr. Chauvin. On Tuesday afternoon, a jury found him guilty of all charges in the murder of Mr. Floyd.

Students are also among those who have been protesting in nearby Brooklyn Center, where the night before high school students returned to in-person classes last week, Mr. Wright, a former MPS student who is Black, was shot and killed by a white police officer. Monday, students across the city participated in a statewide teen-led walkout to protest racial injustice.

For the school district in the middle of this, the events of the past year have required a rethinking about safety. “We’re trying to change how we deliver education, how we meet our kids where they’re at, how we meet their parents where they’re at. That’s a whole systems change that has to happen,” says Jason Matlock, director of emergency management, safety, and security for MPS.

Undergirding the district’s approach is an attempt to better understand why security personnel were called on in the past and how conflicts can be resolved in ways other than bringing in police officers. “We still have to change that whole mindset and that whole feeling of when and why people ask for that type of intervention,” says Mr. Matlock, who notes that in previous years, SRO arrests were often based on staff, parents, or other students in the building requesting assistance in instances such as fights. In a nearby suburban system, arrests dropped after a similar shift from SROs to the use of “safety coaches.”

“For a school to send a message of distrust right at the doorway is now something that schools are trying to avoid; they don’t want to send that message. They want to send a message of welcome and belonging,” says Peter Demerath, associate professor in the College of Education and Human Development at the University of Minnesota, who studies school culture and school improvement.

Khulia Pringle, a Minneapolis resident and former teacher in St. Paul who served on the interview panel for the district’s new safety support specialist positions, says that the mindset around security should also shift away from emphasis on mass school shootings – which she believes are less of a threat in her community – and toward solving conflicts between individuals.

“For me, I’m coming from a Black perspective, and nine times out of 10 what’s unsafe has to do with interpersonal relationships and someone from the community can deter that,” says Ms. Pringle, who also advocates on behalf of parents as part of the National Parents Union. “Hire ex-convicts who’ve been in the system and can relate to people. Elders in the Black, Indigenous, Latinx communities are very, very important. If you want to create safety in the schools, all you have to do is bring in the grandmas.”

A new role

In the 2019-20 school year, MPS contracted with the Minneapolis Police Department for a $1.1 million annual contract for 14 SROs. Those officers were assigned to cover the district’s more than 32,000 students, across high schools, middle schools, and elementary schools.

After the contract was terminated last summer, the district hired 11 civilian safety specialists. Two individuals had been on staff previously in this role, bringing the total to 13 – close to the previous number of SROs. The district says the role is not intended to be a direct replacement of SROs.

“I wouldn’t say there are any similarities other than they do support our emergency management and security functions when necessary. But they are civilian. They are not armed, they don’t carry handcuffs or pepper spray or any of those tools, they’re not uniformed, and they have no power of arrest,” says Mr. Matlock, the district’s security director.

Last June, before the school board vote on SROs, Mr. Genene and other students put together an online survey for current and former students. Of more than 2,000 respondents, 88% of current MPS students supported removing SROs from schools and 97% of former MPS students approved.

“I’ve had students express this idea in the past that they walked down the hall and feel like they had a target on their back or sat in the lunch room and felt like the SRO was looking over their shoulder while they were eating,” Mr. Genene says.

Survey respondents said they instead wanted increased mental health services, restorative justice practices, and more school counselors, social workers, and teachers of color.

A few students were concerned about removing officers. “I feel very unsafe with everything going on and even before all of this I was scared that every day I stepped into school ... a school shooter would come to our school,” wrote one respondent.

For Dane McLain, a world history teacher at North Community High School, ending the contract with the Minneapolis Police Department made many students across the city feel more cared for and therefore safer, even though the SRO at North was individually popular and remains the school’s football coach.

“I think all schools should be representing love and care for students first and foremost. If a student isn’t feeling that way, and if an SRO isn’t contributing to that – and I heard and learned from students that most SROs do not – that pushed me to support the end of the contract.”

Some students interviewed said they didn’t notice the lack of an SRO last week. Others, like Lylian Vang, a freshman at Patrick Henry High School in north Minneapolis, says she did.

“I feel police officers don’t need to be in schools because we have our staff, counselors, principal,” she says walking home after school last week. “It makes students scared, like you did something wrong or something is wrong and it stresses you out.”

She appreciates how her class discussed the removal of police from schools and thinks a better model is for more counselors and mental health specialists. MPS hired some mental health and counseling staff prior to this school year. But Derek Francis, the district’s manager of counseling services, says there’s still a need for more staff. Counselors are being added to every middle school for the next school year, but there are none in elementary schools. Current counselors carry a caseload of 500-to-1 – a ratio twice that recommended by the American School Counselor Association.

A main focus has been on hiring the civilian safety specialists. Some local community activists have criticized the decision to include individuals that have some prior law enforcement experience. Mr. Matlock says more of the specialists have backgrounds in education or community programming, but having a team with some prior security experience was important since “at the end of the day, they do have a security role.”

The district is not allowing the new specialists to be interviewed, citing privacy concerns after their résumés were leaked over the summer to news outlets. But Mr. Matlock says that during remote schooling, specialists have taken security and bias training. They’re also reading books together such as Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns” about the mass migration of Black Americans away from the South, and literature by Black Lives Matters leaders. Specialists visited students disconnected from virtual learning, helped with food distribution, and evaluated school safety plans. Most students and teachers interviewed had not met the specialists assigned to their schools yet.

Police officers will still be called to school buildings in case of emergencies. “We continue to enjoy a strong relationship with our public schools as we all have the same goals in mind. We continue to support public safety in and around our schools,” wrote John Elder, spokesperson for the Minneapolis Police Department, in a statement to the Monitor.

Some community pushback

Still, the shift from SROs to safety specialists hasn’t been without criticism. Last October, three high school principals from north Minneapolis penned the open letter saying violence was rising in their community and said both the school board and police department leaders “exhibited over-generalization, surface-level problem solving and short-sightedness.”

“I don’t think a lot of students know about [the new safety specialists], but there has been some pushback from one group at my high school who are saying that we’re just replacing them with more police, which isn’t true,” Zigi Kaiser, a senior at South High School in Minneapolis and member of the CityWide Youth Leadership Council who advocated to remove police from schools.

Mr. Matlock says that the effort to shift school culture is much broader than the 13 individual specialists. Their positions fit with other district efforts to build trust and equity within schools, such as a plan for a district redesign, which – controversially – will reassign school boundaries for the 2021-22 school year to try and better distribute funding and programming to racially isolated schools.

For now, the thoughts of students are often on the safety of their broader community. Mr. Genene from Washburn High School says that being in school in person for the first time in months and having a conversation in his history class about the shooting of Mr. Wright was “comforting.” But he says that he and many of his friends wish more teachers had talked about current events during their first week back.

“For a lot of people what happened on May 25 is still in their head every minute of every day,” he says, referring to the day Mr. Floyd died. “And for many, events of the past week showed we’re far from resolving this problem.”

A deeper look

How one Chinatown curbs anti-Asian violence and unites a city

Volunteers from different racial backgrounds and ethnicities are walking the streets of Oakland’s Chinatown to help stem hate crimes. The effort is building racial unity and stirring an “awakening” in the Asian American community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Moved by security camera videos of older Asians being viciously attacked in the San Francisco Bay Area, Jacob Azevedo, a young Latino man, offered in an Instagram post to escort anyone in Oakland’s Chinatown who felt unsafe. Others saw the message and wanted to help him: Compassion in Oakland launched in February and has seen volunteer applications grow from hundreds to more than 2,000, and the organization is working to take the initiative to cities across the country.

“This [violence] is the worst we have ever seen, but it’s the best response I’ve ever seen myself, because when the worst came, we are seeing the best of humanity,” says Carl Chan, president of Oakland’s Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, who emigrated from Hong Kong in the 1970s.

He believes Chinatown is safer now, and says volunteers have prevented many incidents. They hand out air horns and teach merchants how to use them if they are robbed. Volunteers then race to the scene and alert police. The volunteers have become the eyes and ears of law enforcement.

One older gentleman, Yau Yuk Shek, reading a newspaper in Renaissance Plaza, says “of course, definitely” he feels more secure with all the patrols. But others still say: We’re scared.

How one Chinatown curbs anti-Asian violence and unites a city

It’s another sunny Saturday in Oakland’s Chinatown, and Jessica Owyoung is addressing a volunteer foot patrol. Pay special attention to people at banks and bus stops, she says, as well as elderly pedestrians who may be slowly crossing the street. They are easy targets. Watch for suspicious vehicles that may be circling. Talk to business owners. Remember to distribute the multilingual booklets on how to report a hate crime. And maybe buy a boba (bubble tea) or lunch to support Chinatown eateries.

She asks for a show of hands on various issues from the more than 20 young people outfitted with neon-yellow safety vests. About half of them, from different racial backgrounds and ethnicities, are first-time volunteers. Four speak Cantonese, the predominant language of this city’s Chinatown. Three speak Mandarin. That’s great – enough to cover each group as they split up and begin patrolling the streets.

“Asian culture doesn’t show a lot of external appreciation,” Ms. Owyoung, one of the co-founders of Compassion in Oakland, a new service to chaperone older adults – or anyone else who feels vulnerable in this enclave – tells them. “Even if you can’t communicate, know that you are appreciated.”

The teams of chaperones are indeed making a difference, confirm merchants and residents, who are astounded at the unprecedented outpouring of help and media attention being shown the Asian American community after videos of violence went viral early in the year. No fewer than 14 groups are patrolling the city’s Chinatown district – residents and outsiders, Asian, Black, Latino, and white volunteers coming together to fight anti-Asian hate here and across the nation. It’s a show of unity in cities up and down California, which has the largest population of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the country. In the process, racial bridges are being built and a rising generation of AAPI are finding their voice in a movement – some say an awakening – unparalleled among Asians in America.

“This [violence] is the worst we have ever seen, but it’s the best response I’ve ever seen myself, because when the worst came, we are seeing the best of humanity,” says Carl Chan, president of Oakland’s Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, who emigrated from Hong Kong in the 1970s.

Not only volunteers – including the chamber’s blue-vest squads, who patrol seven days a week – but also fundraising. A GoFundMe effort pays for private, armed security guards on street corners and outside businesses. A campaign to buy security cameras is gathering momentum. The Oakland Police Department has reinstated Mae Phu as a community liaison officer after budget cuts eliminated her post. She speaks Cantonese and encourages a hesitant population to report crimes. “Goodness [is] coming out from everywhere,” says Mr. Chan.

But he cautions that it’s not enough to have TV cameras show up and everyone declare victory.

Indeed, there are other narratives. More nuanced ones. About Black and Asian communities, so often pitted against each other, now working together – but also exposing a split with Oakland’s mayor over police funding, a debate far from unique to this city. There’s the story about the complexities of hate crimes and incidents against the AAPI community, and how extensive they are. And there are personal accounts of what motivates this new generation of Asian activists and what they hope to achieve as part of one of America’s most diverse – and misunderstood – multicultural communities.

A community on edge

Chinatown here sprawls across a flat, eight-block area wedged between downtown Oakland and an elevated freeway. One of America’s oldest Chinese enclaves, it was forcibly relocated from another part of town in the 1870s and grew rapidly after the 1906 earthquake destroyed San Francisco’s Chinatown. Thousands resettled here.

Today, it is home to about 3,000 people, many of them older people who emigrated from places like Hong Kong and Vietnam, though more young people are moving in. Men play cards for money in the park, and grandmothers treat their grandchildren to custard buns. Boxes of bok choy and melon sit stacked on sidewalks, roast duck hangs in butcher shops, and seafood markets display orange rock fish on ice and razor clams in saltwater tanks.

But it’s a community on edge and bears the marks of a fraught year: businesses boarded up from last summer’s looting in the wake of the George Floyd killing in Minneapolis, many of the storefronts featuring striking murals of Asian and Black unity. Foot traffic is coming back to the commercial center but is sparse on side streets.

Compassion in Oakland was formed after Jacob Azevedo, a young Latino man, saw two videos of unprovoked attacks on older men in the Bay Area. One showed an 84-year-old Thai American being fatally shoved to the pavement across the bay in San Francisco.

Mr. Azevedo offered in an Instagram post to escort anyone in Oakland’s Chinatown who felt unsafe. Others saw the message and wanted to help – first hundreds and now more than 2,000 people. Among them were Ms. Owyoung and three others who now run the group, which launched in February. They didn’t know each other but had experience organizing volunteers and managing events. Now they’re working to take their initiative to cities across the country.

“I was devastated by what’s happening to elderly Asians in our community. It spoke to me,” says Ms. Owyoung, whose family has spanned 70 years in and around Oakland’s Chinatown. Standing at the entrance to the Pacific Renaissance Plaza, whose fountain is the focal point of Chinatown, she points toward where her grandparents used to operate a sewing factory and all the family helped, including the grandchildren.

She gestures across the street to Asian Health Services, a bedrock service for this community where the median household income is $26,353. It used to be a banquet hall. Her parents got married there. This neighborhood is where she came on weekends, to celebrate birthdays, and to usher in the Lunar New Year.

She, too, has been horrified by videos from security cameras of older Asians being viciously attacked. One in particular, of a 91-year-old man shoved to the sidewalk from behind just a few blocks from where Ms. Owyoung is standing, speaks to the complexity of ethnically based hate crimes. It has had millions of views. It prompted actors Daniel Wu and Daniel Dae Kim to offer a $25,000 reward for information that led to the arrest of the person who did it. As it turns out, the victim was Latino; the suspect who shoved him was a homeless man with a history of random assaults and mental health issues.

A hate crime is typically a violent act committed with a prejudiced motive, by a person who selects victims based on their identity – including race. But that’s not always easy to determine. At the time that activists and volunteers stepped up their mobilizing in Oakland’s Chinatown, the Lunar New Year was approaching. That’s when the older generation is known to carry cash gifts in red envelopes for the younger generation. Are assaults, robberies, and muggings of Asian residents in Chinatown at that time, or at any time, hate crimes? Or are they crimes of opportunity against vulnerable people in a neighborhood where 40% of the population is over age 65?

“It’s not just regular crime. This is hate crime for sure,” says Terin Coleman, a formidable-looking security guard and former police officer, standing on the corner of a boarded-up business. “You don’t see random targeting of the elderly in other neighborhoods.” He co-owns the Goliath Protection Group, which is on a three-month contract to bolster security in the neighborhood, paid for by the GoFundMe campaign. Most of the guards carry handguns, batons, pepper spray, and handcuffs. “Thankfully, it’s gotten a lot quieter here,” he says.

Statistics give an incomplete picture of hate crimes and incidents against Asians and Pacific Islanders. Early last year, activists and experts began to notice a spike in attacks. They attributed it to the pandemic originating in China and fueled by rhetoric from President Donald Trump and other politicians, who repeatedly referred to COVID-19 as the “China virus,” among other names. Mr. Chan explains that Asian residents who have experience with viruses from the region began masking up earlier than everyone else – and that this mistakenly set them apart. Others saw them as sick rather than as people just trying to protect themselves. It also made them an easy target for general outrage against China.

One group, Stop AAPI Hate, formed to collect reports of attacks and abuse against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders around the nation. Between March 19 of last year and Feb. 28, it recorded nearly 3,800 such incidents – about 11% of them physical assaults. Because this is a new collection effort, there is no way to compare it with previous years.

A large percentage increase, however, has been reported by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. Earlier this year it revealed that hate crimes against Asian Americans in 16 major cities shot up by nearly 150% in 2020, compared with the year before. But the actual number of incidents remains small: six cases in San Francisco increasing to nine; seven cases in Los Angeles rising to 15; and, in the greatest jump, three cases in New York increasing to 33.

Yet activists maintain that this tally of violence and harassment against Asian communities is just the “tip of the iceberg.” Indeed, Congress is moving toward passing bipartisan legislation to beef up the federal response to hate crimes against AAPI. Experts say the actual level of hate crimes and incidents is partly hidden by the “myth of the model minority,” the assumption that all Asians are successful, highly educated, and wealthy. In Oakland’s Chinatown, nearly a third of the population lives below the poverty line, according to the U.S. census. Only 30% have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and the vast majority speak a language other than English at home.

Ask if someone has encountered racism, and most everyone has a story to tell.

Safer, but still scared

At a rally in Renaissance Plaza, Wendy is in tears as she describes being robbed three times in one month and being called “China virus.” She is not a native English speaker and her comments are translated by Mr. Chan, who gently pats her back as she’s overcome with emotion. Now she volunteers with the blue vests.

Volunteers with Compassion in Oakland talk regularly with older residents, who tell of being harassed, particularly on buses. One woman’s phone was stolen after she got off a bus. Others say they won’t take mass transit to Chinatown at all anymore. They have their children drive them.

Even so, Finnie Phung, who runs the Green Fish Seafood Market with her husband, Eric, says she’s never seen the community pull together so strongly. People are communicating and sharing intelligence on the WeChat app. As she unloads crates of produce, she stops to say she’s happy to have the volunteers, but laments that it’s not possible to station them on every corner. She now looks over her shoulder when she’s on the street. And she emphatically answers “oh yeah” when asked if crime and racism have increased since the pandemic started.

She recounts one incident at a bank where a Black man yelled at her to go back to China and then went on a racist rant. Her teller explained that this customer does that a lot and that it’s OK. “I was shocked,” she says. At the man. At the teller. “It’s not OK.”

Ms. Phung has bought her employees personal alarms and asked them to walk in groups. They now wait for each other at quitting time. Two of her employees, she says, have been attacked with knives. The retired husband of one of her workers got pinned down and robbed. This is not new, she says. It happened to her mother 40 years ago, and to her aunt 20 years ago. What’s new are the media and videos from surveillance cameras bringing everything to light, she says.

Ms. Phu, the liaison officer with the police department, says that statistically the level of crime in Chinatown is about the same compared with before the pandemic. But the crimes, she says, have become more violent and more often target older adults. Both hate crimes and crimes of opportunity are occurring, she says, “but we also know that the Asian community doesn’t usually make a lot of police reports. ... That’s been a problem.”

Language barriers are an issue, but so is the culture. People share information with each other, but not with officials. Mr. Chan, also known as “the mayor of Chinatown,” says people come to him with reports of hate crimes and other abuse. He’s seen a real surge over the past year. He worked with the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office to make it easier for the community to report hate crimes. But when it comes to confirming names and addresses, most people decline, and their cases don’t make the official count or get acted on. “The number being [officially] reported is way less than 20%,” he says.

Still, he believes Chinatown is safer now, and says volunteers have prevented many incidents. They hand out air horns and teach merchants how to use them if they are robbed. Volunteers then race to the scene and alert police. The volunteers have become the eyes and ears of law enforcement.

Whether people actually feel safer is another matter. One older gentleman, Yau Yuk Shek, who is reading a newspaper in Renaissance Plaza, says that “of course, definitely” he feels more secure with all the patrols around. Indeed, a swarm of orange-vested volunteers hovers nearby. But others don’t feel so sanguine. They still say: We’re scared.

Asian-Black unity is not new

Kinyatta George is a frequent volunteer with Compassion in Oakland. The tall, young African American man is eager to help by waiting for people outside banks, sometimes engaging in long talks with merchants and just being a reassuring presence. He’s also an example of Black-Asian unity, which is helping to counter the narrative of enmity between the two communities.

“I can feel some of the old people being uncomfortable,” says Mr. George, who grew up in neighboring Berkeley and just started work as an X-ray technician at San Francisco Airport. “But once I show them a friendly persona, the prejudice drops.” Some of the highly publicized cases of assaults in the Bay Area and elsewhere have involved African American suspects, says David Lee, executive director of the Chinese American Voter Education Committee. “People are sensitive, myself included, of this being used as a wedge issue between African Americans and Asians.”

He cites the 1992 riots in the Los Angeles section of Koreatown after the acquittal of law enforcement officers in the beating of Rodney King, an African American. Tension and violence had been simmering between the two groups, and the media stoked those flames of rivalry and friction, he says.

What’s “remarkable about Oakland,” observes Mr. Lee, is that just after the incident of the man being shoved to the pavement, African American and Asian leaders organized a unity rally just blocks away. “Some of the loudest voices supporting Asian Americans have come from the Black community in Oakland,” he says.

That’s no surprise, says Carroll Fife, a longtime social justice advocate newly elected to the Oakland City Council. She describes this progressive city as one of the most diverse in America, with a long history of Black-Asian unity. She dates the cooperation back to the era of the Black Panther Party, which was founded in Oakland and included among its leaders a Japanese American activist, Richard Aoki. Decades of intercommunity work followed.

“We’ve had Asians for Black lives. It stands to reason we’d have Blacks for Asian lives,” she says.

And yet cracks have appeared: resentment from other neighborhoods that Chinatown has gotten so much attention; generational differences between Asian parents and their children over police funding and the role of police; and a political split.

Earlier this year, police funding caused a public rift between the mayor, and City Council members Fife and Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas, a representative for Chinatown. Since then, the City Council voted unanimously with the mayor to restore citywide funding to police and other community services that had been cut. Larger issues about policing, though, remain unresolved, with a task force on re-imagining public safety readying its final recommendations as the city nears a budget deadline for the next two years.

“A multicultural poster”

Ms. Owyoung of Compassion in Oakland steers clear of politics. She’s too concerned about making the most of the current momentum and building out the organization, even though the founders all have day jobs (hers is as a counselor of students with disabilities).

“Our No. 1 challenge is time,” she says. “We know that we have to move quickly because we don’t know how long this momentum is going to last.” While Black and Latino communities each have “solidarity,” she notes, “There’s never been this huge of a movement and focus only on Asian Americans.”

Up to now, Asians have been taught to just accept racist acts in order to move forward in America, the volunteer leader notes. Historically, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned Chinese laborers from coming to the United States. Although the act was repealed in 1943, Chinese immigrants were restricted until 1965, when the National Origins Formula was abolished. Japanese Americans were interned in camps during World War II.

Ms. Owyoung’s grandmother was not allowed to live outside Chinatown in San Francisco, and when the family moved to Oakland, it was prohibited from buying property in certain areas.

What’s most gratifying about her work now is seeing so many volunteers from so many backgrounds showing that they care. “I’m going to cry” – she pauses for a second – “just seeing them build relationships and getting to know each other.” The other day, she saw a white person, African American, and Asian in one of her volunteer pods exchange phone numbers after their shift and then grab something to eat. They were like “a multicultural poster.”

In the foot-patrol teams, the cross-pollination is evident. Walking along the streets, Christina Chen, a lawyer in San Francisco, acts almost as a docent to the other pod members: That parking lot is where she played as a child; that’s where her parents have their acupuncture practice (both have been robbed); the murals are to cover up graffiti. At the end of their shift, Justin Zerber, who is white, comments how much more aware he is now that he’s walked in a different community.

In another group two Asian Americans share their experiences. Hochi Manglapus, from behind round blue sunglasses, says he felt “a bit invisible” growing up in a white neighborhood. A first-time volunteer, he now feels like he’s part of an “awakening” of Asians who, instead of trying to fit in, are finding their own voice.

Cami Louie, her dog tugging at a leash, says most of her friends are Black and Latino. The nursing student is now patrolling the streets that her grandparents walked. To her, it is more than a movement. It’s standing up for yourself. “I’ll be doing that as long as I live,” she says.

Still, she wonders what the impact of the volunteers will really be. “I don’t know if us being out there is doing anything. People still have their prejudices.”

True. But certainly not among the chaperones here.

• Halton Suen was an interpreter for this report.

Worse than the Cold War? US-Russia relations hit new low.

U.S.-Russia relations are, in some ways, now worse than they were during the Cold War. That has left some Russians wondering if engagement with the U.S. is even worthwhile anymore.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Russia’s relations with the West, and the United States in particular, appear to be plumbing depths of acrimony and mutual misunderstanding.

Events have cascaded over the past month. Russia’s treatment of imprisoned dissident Alexei Navalny, who has been sent to a prison hospital amid reports of failing health, underlines the differences between Russia and the West over matters of human rights. Meanwhile, a Russian military buildup near Ukraine has illustrated that the conflict might explode at any time.

Foreign policy experts agree that there is a long list of practical issues that could benefit from high-level discussion. With the U.S. preparing to exit Afghanistan, some coordination with regional countries, including Russia, might make the transition easier for everyone. One of President Joe Biden’s first acts in office was to extend the New START arms control agreement, but the former paradigm of strategic stability remains in tatters, experts say.

“If you are looking for opportunities to make the world a safer place through reason and compromise, there are quite a few,” says Andrey Kortunov, director of the Russian International Affairs Council. “There are also some areas where the best we could do is agree to disagree, such as Ukraine and human rights issues.”

Worse than the Cold War? US-Russia relations hit new low.

Russia’s relations with the West, and the United States in particular, appear to be plumbing depths of acrimony and mutual misunderstanding unseen even during the original Cold War.

After years of deteriorating relations, sanctions, tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions, and an escalating “information war,” some in Moscow are asking if there even is any point in seeking renewed dialogue with the U.S., if only out of concern that more talking might just make things worse.

Events have cascaded over the past month. Russia’s treatment of imprisoned dissident Alexei Navalny, who has been sent to a prison hospital amid reports of failing health, underlines the sharp perceived differences between Russia and the West over matters of human rights. Meanwhile, a Russian military buildup near Ukraine has illustrated that the conflict in the Donbass region might explode at any time, possibly even dragging Russia and NATO into direct confrontation.

President Joe Biden surprised the Kremlin by proposing a “personal summit” to discuss the growing list of U.S.-Russia disagreements in a phone conversation with Vladimir Putin last week. He later spoke of the need for “disengagement” in the escalating tensions around Ukraine, and postponed a planned visit of two U.S. warships to Russia-adjacent waters in the Black Sea.

But days later he also imposed a package of tough sanctions against Russia, for its alleged SolarWinds hacking and interference in the 2020 U.S. presidential elections, infuriating Moscow and drawing threats of retaliation. Last month, after Mr. Biden agreed with a journalist’s intimation that Mr. Putin is a “killer,” the Kremlin ordered Russia’s ambassador to the U.S. to return home for intensive consultations, an almost unprecedented peacetime move. Over the weekend, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov suggested that the acting U.S. ambassador to Moscow, John Sullivan, should likewise go back to Washington for a spell. On Tuesday, Mr. Sullivan announced he would do just that this week.

And there is a growing sense in Moscow that the downward spiral of East-West ties has reached a point of no return, and that Russia should consider abandoning hopes of reconciliation with the West and seek permanent alternatives: perhaps in an intensified compact with China, and targeted relationships with countries of Europe and other regions that are willing to do business with Moscow.

“Things are at rock bottom. This may not be structurally a cold war in the way the old one was, but mentally, in terms of atmosphere, it’s even worse,” says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of Russia in Global Affairs, a Moscow-based foreign policy journal. “The fact that Biden offered a summit meeting would have sounded a hopeful note anytime in the past. Now, nobody can be sure of that. A hypothetical Putin-Biden meeting might not prove to be a path to better relations, but just the opposite. It could just become a shouting match that would bring a hardening of differences, and make relations look like even more of a dead end.”

Room for discussion

Foreign policy experts agree that there is a long list of practical issues that could benefit from purposeful high-level discussion. With the U.S. preparing to finally exit Afghanistan, some coordination with regional countries, including Russia and its Central Asian allies, might make the transition easier for everyone. One of Mr. Biden’s first acts in office was to extend the New START arms control agreement, which the Trump administration had been threatening to abandon, but the former paradigm of strategic stability remains in tatters and requires urgent attention, experts say.

“If you are looking for opportunities to make the world a safer place through reason and compromise, there are quite a few,” says Andrey Kortunov, director of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “There are also some areas where the best we could do is agree to disagree, such as Ukraine and human rights issues.”

The plight of Mr. Navalny, which has evoked so much outrage in the West, seems unlikely to provide leverage in dealing with the Kremlin because – as Western moral authority fades – Russian public opinion appears indifferent, or even in agreement with its government’s actions. Recent surveys by the Levada Center in Moscow, Russia’s only independent pollster, found that fewer than a fifth of Russians approve of Mr. Navalny’s activities, while well over half disapprove. An April poll found that while 29% of Russians consider Mr. Navalny’s imprisonment unfair, 48% think it is fair.

Tensions around the Russian-backed rebel republics in eastern Ukraine have been much severer than usual, with a spike in violent incidents on the front line, a demonstrative Russian military buildup near the borders, and strong U.S. and NATO affirmations of support for Kyiv. The Russian narrative claims that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy triggered the crisis a month ago by signing a decree that makes retaking the Russian-annexed territory of Crimea official Ukrainian state policy. Mr. Zelenskiy has also appealed to the U.S. and Europe to expedite Ukraine’s membership in NATO, which Russia has long described as a “red line” that would lead to war.

But Russian leaders, who have been at pains to deny any direct involvement in Ukraine’s war for the past seven years, now say openly that they will fight to defend the two rebel republics. Top Kremlin official Dmitry Kozak even warned that if conflict erupts, it could be “the beginning of the end” for Ukraine.

“This is a very desperate situation,” says Vadim Karasyov, director of the independent Institute of Global Strategies in Kyiv. “We know the West is not going to help Ukraine militarily if it comes to war. So we need to find some kind of workable compromises, not more pretexts for war.”

Time to turn eastward?

In this increasingly vexed atmosphere, the Russians appear to be saying there is no point in Mr. Putin and Mr. Biden meeting unless an agenda has been prepared well in advance, setting out a few achievable goals and leaving aside areas where there can be no agreement.

“Russia isn’t going to take part in another circus like we had with Trump in Helsinki in 2018,” says Sergei Markedonov, an expert with MGIMO University in Moscow. “What is needed is a deeper dialogue. That could begin if we had a real old-fashioned summit between Biden and Putin, one that has been calculated to yield at least some positive results. We need to find a modus vivendi going forward, and the present course is not leading there.”

Alternatively, Russia may turn away from any hopes of even pragmatic rapprochement with the West, experts warn.

Mr. Lukyanov, who maintains close contact with his Chinese counterparts, says they felt blindsided at a summit with U.S. foreign policy chiefs in Alaska last month, when what they expected to be a practical discussion of how to overcome the acrimonious Trump-era legacy in their relations turned into what they saw as a U.S. lecture about how China needs to obey the “rules-based” international order.

“It was the Chinese, in the past, who were very cautious about participating” in anything that looked like an anti-Western alliance, says Mr. Lukyanov. “We are hearing a new tone from them now. Now our growing relationship with China isn’t just about compensating for a lack of relations with the U.S. It’s about the need to build up a group of countries that will resist the U.S., aimed at containing U.S. activities and policies that are harmful to our two countries.”

In South African architecture, women build on social justice

Architecture springs from more than imagination. Each building is shaped by the lives of the people who designed it – one reason that Black female architects are determined to blaze a trail for the next generation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In South Africa, the gap between who designs buildings and who actually lives in them is one of the widest in the world. About 4 in 5 architects are white, though white South Africans are only about 9% of the population. Less than one-third of architects are women, and just 4% women of color.

The push to change that is part of the country’s overall transformation since the end of apartheid. But it also ties into an international conversation about who gets to design the spaces we move through every day. From Austria to India, city planners have wrestled with how to better accommodate people traditionally left out of design. That can mean anything from widened sidewalks to better accommodate strollers to women-only train cars meant to deter harassment.

Althea Peacock and Tanzeem Razak, co-founders of Lemon Pebble Architects in Johannesburg, were part of the first generation of Black female architects here. At the time, South Africa was on the cusp of enormous change, and young architects saw potential to quite literally rebuild the country.

“We grew up in spaces that were cheap and often ugly by design – just sand and concrete,” says Ms. Razak. “We wanted to say, these places can also be beautiful too. There is dignity in that.”

In South African architecture, women build on social justice

When Ngillan Faal was growing up in Gambia, in West Africa, it was clear to her that her family’s colonial bungalow had not been designed by or for people like them.

It had a kitchen with a stove, but since the family preferred to prepare most meals over a fire, they had to do that outside. The rooms in the house, meanwhile, turned stuffy and hot in the tropical sun, and so the family spent most of their time socializing outdoors, in the shade of the trees.

“I remember being intrigued by how everything that happened in that house happened in opposition to the building itself,” she says. “That was when I first realized that spaces fundamentally affect the quality of our lives.”

Today, Ms. Faal is a practicing architect in South Africa, where the gap she observed in her childhood – between who designed buildings and who actually lived in them – is one of the widest in the world. About 4 in 5 architects here are white, although white South Africans make up only 9% of the population. Less than a third are women, and just 4% women of color, according to unpublished data from the South African Council for the Architectural Profession, obtained by the Monitor.

Since the end of apartheid, legislation, social pressure, and affirmative action programs have propelled massive change in many industries here. Black female journalists, for instance, lead a third of the country’s major publications, up from 6% in 2006. For many here, this kind of transformation is seen as a moral imperative – a way of rebuilding a society built to exclude people of color.

But for architecture and urban design in particular, diversity is also part of a wider international conversation about who gets to design the spaces we all move through every day. From Austria to India, city planners in recent years have wrestled with how to build spaces that better accommodate women and other people traditionally left out of design. That can mean anything from widened sidewalks to better accommodate strollers as Vienna did, to India’s women-only train cars, meant to deter harassment, and movements around the world to add more women’s bathrooms to public buildings and spaces.

Buildings are an important part of the equation as well, says Althea Peacock, co-founder of Lemon Pebble Architects in Johannesburg, one of South Africa’s only architecture firms fully run by women of color. For instance, female architects tend to design buildings that are “more empathetic to the ways in which women are vulnerable,” she says. That can mean including more lights for safety, more bathrooms, and more places to breastfeed or change a diaper. In countries like South Africa, it can also include things like more space on streets and sidewalks for hawkers – many of whom are women – to sell goods. “There are many small ways you can shift design to accommodate women and the ways women move through the world differently than men,” she says.

Blazing a trail

Ms. Peacock and her co-founder, Tanzeem Razak, were part of the first generation of Black female architects in South Africa, who trained and began work during the country’s transition to democracy in the early 1990s. They were breaking a thick glass ceiling: Universities that trained architects during apartheid were almost exclusively reserved for white students, and most were men.

Karuni Naidoo, who comes from South Africa’s Indian community, remembers going to the Department of Indian Affairs in Durban, the coastal city where she grew up, to formally request permission to enroll in an architecture program at a white university there in the 1980s.

“You had to make a case for why it was worth letting you have a spot” that could have gone to a white student, says Ms. Naidoo, who now runs the transformation committee at the South African Institute of Architects – which works on questions of diversity – and CNN Architects, the practice she co-founded in Durban.

Once she enrolled, it felt like she straddled two worlds. Each morning, she woke up in the Indian township on the fringes of the city where her family had been confined by apartheid city planning, where most public buildings were drab and cheaply made. Then she took a bus across town to the white part of the city, with its art deco office blocks and ornate Edwardian houses, where she spent hours listening to lectures exclusively on European styles of architecture, before heading back out into apartheid South Africa.

“When I looked up in the profession, I didn’t see anyone who looked like me,” she says.

Form and function

But at the same time, South Africa was on the cusp of enormous change. And young Black architects saw potential in their own careers to quite literally rebuild the country.

“One of our philosophies is that people with low resources can still aspire to beautiful, functional spaces,” says Ms. Razak, Ms. Peacock’s co-founder at Lemon Pebble. “We grew up in spaces that were cheap and often ugly by design – just sand and concrete. We wanted to say, these places can also be beautiful too. There is dignity in that.”

She points to a preschool that the firm designed in Vosloorus, a township near Johannesburg. It’s filled with light-drenched courtyards and vivid colors, with maps of the township painted on the walls to help kids “be proud of where they come from,” Ms. Razak says.

Ms. Faal, the Gambian architect, recently worked on a Johannesburg law firm for Kate Otten Architects, South Africa’s most prominent woman-owned firm. The architects drew in part on advice from women working at the practice to create a space full of “places to sit and stop and chat, where life could happen.” That included a window seat designed specifically for pregnant women to rest in.

In South Africa, firms owned by Black female architects benefit from a government program called Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment (or BEE, as it’s known to most South Africans), which scores companies on diversity, particularly when it comes to the race and gender of their leadership. High BEE ratings help companies win government contracts.

But within the profession itself, many say not nearly enough has been done to either recruit or retain Black female architects (or architects who are either one or the other).

“Here you are sitting in classes where your professors are telling you that they’re decolonizing the curriculum and decolonizing built spaces, and then they assign you projects that rely on expensive supplies, and if you don’t have them, you don’t succeed,” says Chinenye Chukwuka, a recent graduate of the University of Cape Town’s architecture school. “At a point I had to ask myself, who are the people ending up at the top of architecture school? Is it the people who are smarter, who will be better architects, or is it just the people who have more resources? And is it a coincidence that the people with the least resources tend to be Black?”

Book review

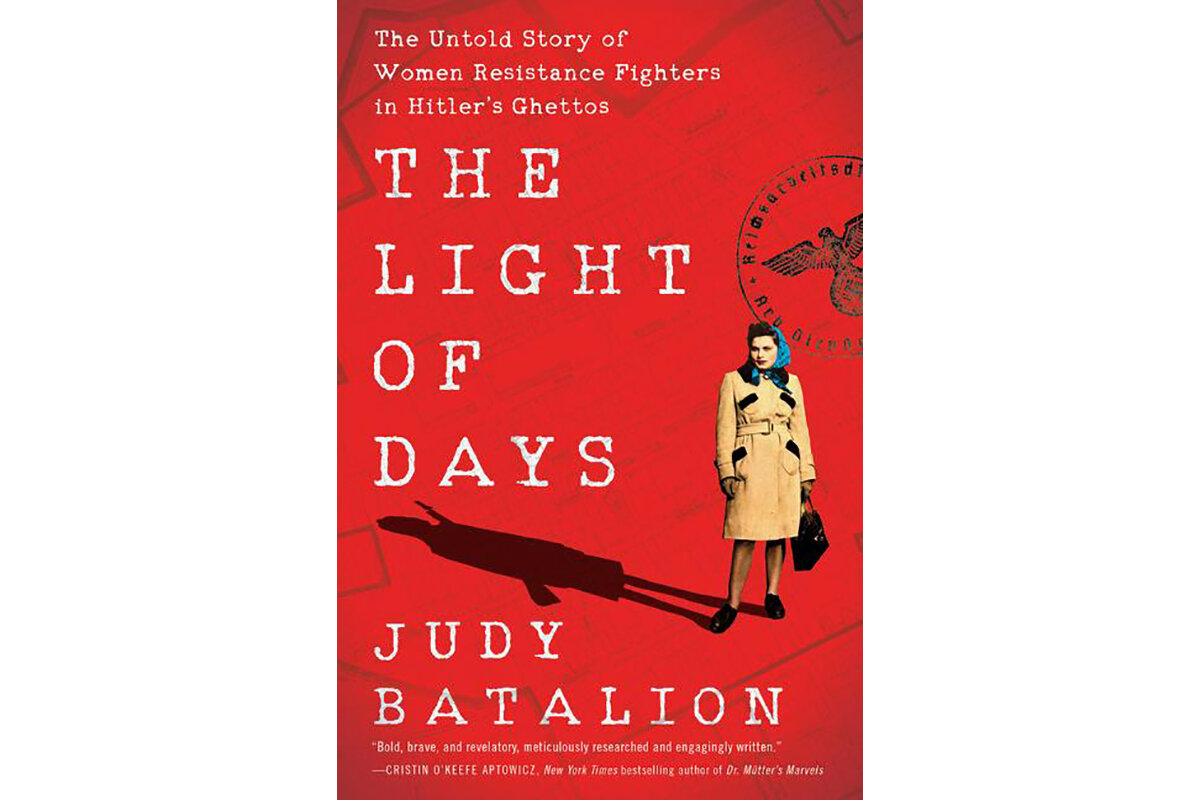

Jewish women spied, smuggled, and sabotaged under the Nazis’ noses

As more is learned about women in history, untold stories of courage and heroism emerge. These revelations challenge how women have been perceived, and cast them in a fuller light.

-

By Barbara Spindel Correspondent

Jewish women spied, smuggled, and sabotaged under the Nazis’ noses

In 1942, two years before his death at the hands of the Gestapo, Polish-Jewish historian Emanuel Ringelblum, in a diary entry written from the Warsaw Ghetto, praised the courage of female resistance fighters. “How many times have they looked death in the eyes? How many times have they been arrested and searched?” he marveled. “The story of the Jewish woman will be a glorious page in the history of Jewry during the present war.”

Alas, Ringelblum’s prediction did not come to pass. Instead, as Judy Batalion observes in her thrilling, devastating new book, “The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos,” the heroism of the female resisters has been largely forgotten.

Batalion embarked on the project after coming across a neglected Yiddish volume in the British Library called “Women in the Ghettos,” published in 1946. The stories of young women “smuggling, gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, and engaging in combat” astounded her, not least because the author, whose grandparents were Polish Jews who fled the Nazis, had grown up thinking of escape as the only means of resistance available to Europe's Jews during the Holocaust.

The successes of the Jewish resistance were minor relative to the scale of the Nazi genocide. (More than 90% of Poland’s Jewish population perished in the Holocaust.) Even so, reading about the intricate underground web of fighters and spies is revelatory. “The Light of Days” traces the experiences of roughly 20 Polish women, based on their own memoirs and testimony, archival material and other historical sources, and interviews with the family members of those who survived the war. In Batalion’s hands, their stories are taut and suspenseful, but the author also weaves in important context about prewar Poland, life in the ghettos, and the progression of the war.

Many resistance fighters, both female and male, came from a robust network of Jewish youth groups, often with Zionist and socialist leanings, that had been active before Germany invaded Poland in 1939. They remained operational at the start of the war, as the Germans isolated Poland’s Jewish population in hundreds of ghettos. They secretly created and distributed books on Jewish history and culture (books by Jewish authors had been banned) and taught classes to ghetto children. “They were preparing for a future they still believed in,” Batalion writes.

Once they came to the sickening realization that the Nazi plan was the liquidation of the ghettos and the annihilation of all Jews, the youth groups shifted to armed defense, amassing weapons, real and makeshift, and training members to fight. (Some joined the partisan units in the forests.) They were not unrealistic about what they could achieve; the goals of acts of resistance like the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising were to exact some small revenge and to die with honor.

Batalion explains why women were tasked with the dangerous work of sneaking into and out of the ghettos, passing along intelligence, cash, and supplies: unlike Jewish boys, who had often studied in yeshivas, girls had attended public schools and thus spoke Polish without a recognizably Yiddish accent. More importantly, a male’s Judaism could be easily confirmed by seeing if he was circumcised. Jewish women with Aryan features had a better chance of safely traveling throughout Poland, although their risks were still enormous. A woman with a pistol hidden in a loaf of bread might be recognized as Jewish by a former neighbor, or her documents might be discovered to be forgeries.

Most of the female resisters were in their teens and early 20s; most had already lost their families, and they formed intense bonds with their comrades. The teenaged Renia Kukielka, who wrote a detailed memoir right after the war, is one of the book’s central figures. Described by Batalion as “a savvy, middle-class girl who happened to find herself in a sudden and unrelenting nightmare,” Renia followed her sister into the resistance after their parents were killed.

Renia smuggled weapons and cash and helped sneak Jews into hiding places. Her feats of bravery included jumping off a moving train and proceeding through Nazi checkpoints with fake passports and weapons strapped to her body. She was eventually imprisoned for traveling with a forged passport. Although she was starved and beaten brutally, she would have been killed had her captors known she was Jewish. Renia escaped the prison. Soon after, she was smuggled out of Poland and eventually reached Palestine. Her story is so remarkable, Batalion reports, that “in her sixties, Renia read her own book in disbelief: How had she possibly done those things?”

Batalion offers many reasons for the erasure of these women’s stories. For one, most did not live to tell of their experiences. Batalion further argues that scholars haven’t highlighted memoirs like Renia’s because “writing about fighters might give the impression that the Holocaust was ‘not that bad’ – a risk in a context where the genocide is fading from memory.” In addition, the author adds, the focus on resistance could lead to “judging those who did not take up arms, and ultimately blaming the victim.” Mindful of these hazards, Batalion has produced an overdue account that helps restore some of the young Polish victims of the Holocaust to their full complexity.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Military chaplains: Their new role as peacemakers

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

President Joe Biden’s decision to pull troops out of Afghanistan has raised profound questions. Yet it may take decades to know fully how a U.S. pullout in Afghanistan, and someday in Iraq, will play out. In at least one profound way, both wars have fundamentally changed how the U.S. fights wars and makes peace.

A recent U.S. mission in Burkina Faso shows how. The Special Operations Command Africa, whose primary focus is training African troops in counterterrorism tactics, sent an interfaith religious team to help build the African country’s first military chaplains corps. That effort reflects a recognition drawn from two decades of fighting insurgencies in countries largely shaped by religion.

The traditional role of chaplains is to provide spiritual care for troops in combat. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan changed that as commanders struggled to build bridges with local communities. Increasingly they turned to the chaplains. Over time a doctrine of faith-based peace building has been developed involving chaplains at all levels of military operations. It has honed a powerful idea – that religion, so often a spark of war, can be a military tool for peace. In the Sahel, that idea is spreading.

Military chaplains: Their new role as peacemakers

When the United States withdrew its troops from Vietnam in 1973, critics warned of long-term negative consequences. Some came true, yet within a generation, the West had won the Cold War and much of Asia was democratic. The U.S. and Vietnam are close friends. Similar warnings are now being made about President Joe Biden’s decision to exit Afghanistan, nearly two decades after ousting the Taliban and crushing Al Qaeda in response to 9/11. Yet as with Vietnam, it may take decades to know fully how a U.S. pullout in Afghanistan, and someday in Iraq, will play out. In at least one profound way, both wars have fundamentally changed how the U.S. fights wars and makes peace.

A recent brief U.S. mission in Burkina Faso shows how. The Special Operations Command Africa, whose primary focus is training African troops in counterterrorism tactics, sent a three-person interfaith religious team to help build the African country’s first military chaplains corps. That effort reflects a recognition drawn from two decades of fighting insurgencies in countries largely shaped by religion. As an unclassified “instruction” from the chairman of the Joint Chiefs stated last October: “Outside of Western Europe and North America, populations that hold to historic religious faiths continue to increase. This growth, coupled with shifting immigration trends, presents important issues for the Joint Force. It challenges our understanding of how religion motivates and influences allies, mission partners, adversaries, and indigenous populations and institutions.”

The traditional role of military chaplains is to provide spiritual care for troops in combat. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan changed that as commanders struggled to build bridges with local communities. Increasingly they turned to the chaplains in their units. Over time a doctrine of faith-based peace building in the field has been developed involving chaplains at all levels of military operations.

Burkina Faso is one of five countries in the Sahel region of Africa battling against an array of Islamist factions. Its new chaplain corps includes Muslims and Christians. The initial goal was to tend to troops demoralized by combat and the pandemic. After training with U.S. chaplains, they now see themselves as “force multipliers” uniquely suited to advancing peace mediation in military operations. Neighboring Mali has expressed interest in developing a similar model.

“The U.S. Military cannot overlook religious factors in conflict if it is to achieve peace,” argued Capt. Anna Page, a chaplain in the 414th Civil Affairs Battalion, in a recent essay in Eunomia Journal. “Religion can enable peace. The military, therefore, needs experts who adhere to its doctrines and speak the language of faith. These people are chaplains.”

The long war in Afghanistan may have shown the limits of building democracy in societies structured by different norms. Mr. Biden’s critics charge him with embracing defeat. But that conflict, like the one in Iraq, has honed a powerful idea – that religion, so often a spark of war, can be a military tool for peace. In the Sahel, that idea is spreading.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

My protest plans

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Trudy Palmer

How can we heal division and injustice, whether race-based or otherwise? A spiritual take on the concept of “protesting” offers a radical starting point.

My protest plans

Less than a year ago, I was trying to comprehend George Floyd’s death under the knee of a police officer. Now, the trial of that former officer, Derek Chauvin, has ended, and a verdict has been reached. But the need to fix the problems that led to George Floyd’s death and heal divisions and injustices in the United States and elsewhere persists. And that calls for protesting.

I’m talking about protesting in the way Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, describes it in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.” She says that Jesus’ “humble prayers were deep and conscientious protests of Truth, – of man’s likeness to God and of man’s unity with Truth and Love” (p. 12).

“Humble prayers.” Hmmm. Do I have the humility, I ask myself, to let go of my own opinions about the Derek Chauvin case and instead protest in favor of man’s likeness to God? What would that even look like? And would it change anything?

The first chapter of the Bible says that God made man, which refers to everyone, in His image. Everyone’s true identity is spiritual, the likeness of God, divine Spirit. And since we’re God’s likeness, we’re inseparable from God.

That’s where the unity part comes in. Jesus’ prayers were protests of our “unity with Truth and Love,” which are names for God. As God’s likeness, our unity with divine Truth and Love is already established. We don’t have to do anything to make it happen. Our job is to live it, to express our unity with Truth and Love in the way we think and act. As Science and Health puts it, “The scientific unity which exists between God and man must be wrought out in life-practice...” (p. 202).

That “life-practice” is my protest – striving, moment by moment, for all that I do and say to show my unity with Truth and Love. And to ensure that the way I think of others honors their unity with Truth and Love.

That might seem like a pretty quiet protest plan, but picture the power of us all putting our unity with God, with divine Truth and Love, into practice. That looks like justice to me.

A message of love

A decisive verdict

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look deeper at the Chauvin verdict’s implications. Where does America go from here in its reckoning on racism? Plus, how does the Minneapolis trial compare with other big cases where racial justice was at stake?

Editor’s note: Today’s audio differs from the text due to the late-breaking verdict in the trial of Derek Chauvin.