- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Iran nuclear deal may be just what hard-line president-elect needs

- ‘The pope needs to apologize.’ Unmarked graves near schools roil Canada.

- How risky is virus ‘gain of function’ research? Congress eyes China.

- Nicaraguans sound alarm over declining democracy. Who’s listening?

- Beach-worthy books to savor in summer: Monitor staff picks

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘The poet’s bird,’ summer afternoons, and hope in a time of troubles

I heard a hermit thrush on the road down to the boat landing this week, and thought of summer.

In warmer months, hermit thrush song is one of the glories of the woodlands of northern America and Canada. The appearance of the birds themselves is drab and unremarkable. As the name implies, they are reclusive and difficult to spot. But their music! Soft, trilling, and ethereal, it spirals out from the trees, a haunting message from another world, or another time.

They’re common in our area of Maine, showing up in lowland forests in late spring. When they start singing, the leaves are out and there is dappled sunlight on the floor of the woods. Perhaps they’re not as well known as chickadees or loons, but to me they evoke the height of the year, the early afternoon of perfect weather days, with an undercurrent of melancholy, the knowledge the weather, and the season, won’t last.

“Ancient stories which can go on for long stretches of time,” an ornithologist I know says of their songs.

The hermit thrush has inspired a number of poets. Sometimes it’s even been called “the poet’s bird.” Perhaps its most famous literary appearance is in Walt Whitman’s great elegy for Abraham Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom’d.” Whitman used “a shy and hidden bird,” “the thrush,” “the hermit,” as nothing less than the collective musical expression of the grief and hope of the American people at a time of troubles.

Sing on! sing on, you gray-brown bird!

Sing from the swamps, the recesses – pour your chant from the bushes;

Limitless out of the dusk, out of the cedars and pines.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Iran nuclear deal may be just what hard-line president-elect needs

Why would Iran’s president-elect want a compromise with the U.S. to revive the nuclear deal? The answer lies in how hard-liners see their best way to satisfy, and pacify, a disgruntled, apathetic population.

For years in Iran, the one constant of hard-line politics has been punishment of President Hassan Rouhani over the landmark 2015 nuclear deal. Today antagonism toward the agreement and Washington has not changed, even as Iran prepares for new talks in Vienna to restore the deal.

So then why does Ebrahim Raisi, the hard-liner’s hard-liner, who was elected president a week ago, favor getting back to that same “flawed” deal? Perhaps the main reason, say analysts, is that his ascent to the presidency after a record-low voter turnout means that success for him will require sanctions to be lifted.

The hard-liners’ response to voter apathy is a bid to create a pragmatic new Iran “brand” that accommodates a lack of popular support, and dwindling inspiration drawn from religion, while emphasizing instead satisfying economic needs.

“What we may be seeing is simply a new social contract in the making,” says a well-connected Iranian analyst. “Given the trends that I see and sense among young people that I get to meet in Iran, people would say, ‘Just give me Wi-Fi, some sort of economic prosperity or safety, and then leave me alone with your politics. I don’t need that.’”

Iran nuclear deal may be just what hard-line president-elect needs

For years in Iran, the one constant of hard-line politics has been severe punishment of President Hassan Rouhani over the landmark 2015 nuclear deal with the United States and other world powers.

While negotiating with the American archenemy, hard-liners said, the centrist Mr. Rouhani had presided over a humiliating compromise and traitorous giveaway of Iran’s nuclear crown jewels, for little in return.

Final proof for the hard-liners – both of U.S. duplicity and Iranian foolishness – came when then-President Donald Trump withdrew from the nuclear deal in 2018 and imposed a new raft of suffocating “maximum pressure” sanctions.

Today hard-line antagonism toward the agreement and Washington has not changed, even as Iran prepares for a seventh round of talks in Vienna to restore the deal, officially titled the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

So then why does Ebrahim Raisi, the hard-liner’s hard-liner, who was elected president a week ago, favor getting back to that same “flawed” deal?

Perhaps the main reason, say analysts, is that Mr. Raisi’s ascent to the presidential seat, with little popular mandate after a record-low voter turnout, means that success for him in office will require sanctions to be lifted.

Hard-liners, too, need sanctions eased as they pursue a new social contract focused on economic fulfillment to replace the once-paramount democratic and Islamic criterion of legitimacy, espoused by Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The sooner the better

And lifting sanctions will require a return to the JCPOA, distasteful as a new compromise with the U.S. may be for hard-liners who now control all key levers of power in Iran.

Ideally, for Mr. Raisi, the nuclear deal would be restored even before he assumes office in August – so Mr. Rouhani could again be blamed for selling out, while the new president reaps the economic benefit.

“Raisi and even some of the hard-line forces behind him ... don’t necessarily favor a revival of the JCPOA, but they want sanctions to be lifted,” says Bijan Khajehpour, a veteran Iran analyst and managing partner at Eurasian Nexus Partners in Vienna.

“Two years ago, they wouldn’t understand that these two actually relate to each other, but now they fully understand that if they really want sanctions to be lifted, then they have to restore the JCPOA,” says Mr. Khajehpour. “They understand this is the only way to get rid of the banking sanctions, the oil and shipping sanctions. So the resolve is there to do it.”

During the election campaign Mr. Raisi indicated he would not oppose a return to the JCPOA, which has the imprimatur of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

But recent reporting that a return to the deal was all but agreed to weeks ago, and that Iran was dragging its feet until after the June 18 election, is overstated, a senior U.S. diplomat said Thursday.

“We still have serious differences that have not been bridged,” a senior State Department official, speaking without attribution, told journalists. “It remains possible ... but we’re not there yet, and I’m not going to speculate as to if or when we will get there.”

When asked if Iran will stick to the JCPOA, Mr. Raisi said Monday that “our foreign policy will not begin with the JCPOA and will not be limited to the JCPOA.” Hard-line media in Iran has shifted from noisily demanding that Mr. Rouhani pull out of the deal, to now claiming that “a strong and revolutionary government is able to claim Iran’s rights” – and that Mr. Raisi can be trusted not only to remove sanctions, but also to “neutralize” them.

Disillusioned voters

Mr. Raisi’s victory was hardly a landslide, and the result of an unprecedented series of moves by the establishment to pave the way for his victory. A veteran of the judiciary, he is tainted by his role in a four-man “death commission” that oversaw the execution of thousands of prisoners in 1988.

He was defeated by Mr. Rouhani at the polls in 2017, and this time faced a boycott by reformists and widespread apathy and voter disillusionment. Fewer than 50% of eligible voters turned out – the lowest ever in a presidential race. And while Mr. Raisi won with 62% of the votes cast, that represents just one-third of the electorate.

The number of spoiled ballots, some 12% of the total – a “protest” vote three times larger than in any previous election – was higher than that received by Mr. Raisi’s closest challenger.

The result is a bid to create a pragmatic new Iran “brand” that accommodates a lack of popular support, and dwindling inspiration drawn from religion, while emphasizing instead satisfying economic needs.

“What we may be seeing is simply a new social contract in the making,” says a well-connected Iranian analyst who travels frequently to the country and asked not to be named.

“Given the trends that I see and sense among young people that I get to meet in Iran, people would say, ‘Just give me Wi-Fi, some sort of economic prosperity or safety, and then leave me alone with your politics. I don’t need that,’” says the analyst. “And in fact, you then have people OK with their livelihoods, who may simply forgo this whole idea of political participation.”

That trade-off marks a transformation from a revolutionary state to one in which popular political support is no longer necessary, says Mr. Khajehpour at Eurasian Nexus Partners.

“We have to accept that ... democracy is not a top priority. It’s economic growth, it’s power projection, it’s controlling the different regional and internal challenges. It’s a very different design of a state,” he says.

“Especially for hard-liners in Iran, it is a lot more inspired by the way [President Vladimir] Putin presents Russia: ‘We are strong,’” with a strong military and economy, says Mr. Khajehpour.

The new social contract

The planned pivot is ambitious, though some elements have fallen into place. Hard-line and conservative voices in Iran note that the Islamic Republic has survived Mr. Trump’s maximum-pressure campaign and Israel’s cyberattacks and assassinations, and has violently crushed widespread protests against corruption, mismanagement, and the struggling economy.

But providing some satisfaction to a disgruntled and increasingly impoverished population is key to such a vision – which makes sanctions relief therefore necessary.

The “new social contract” involves the government giving more power to local councils to resolve local needs, says Mr. Khajehpour. But it is coupled with a “national government that says, ‘I don’t want anyone to interfere in my defense and foreign and regional policy decisions; it’s none of your business. I know it’s not democratic.’”

“And society says, ‘As long as you make sure we have welfare, economic development, and jobs, we are not going to go on the street and protest for political freedoms and human rights,’” says Mr. Khajehpour.

The result is a bid to create a “new brand of Iran,” he adds. But it is a gamble, which in critical ways is dependent on a compromise with Washington – and the actions of your avowed enemy.

“It is true that Iran’s conservatives remain inherently hostile to the United States. ... Raisi has made no secret that this is his mantra,” writes Vali Nasr, an Iran and regional expert at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, in an analysis this week in Foreign Policy.

“Still, behind the veneer of ideological obduracy a new realism is setting in, one that comes with total victory,” writes Mr. Nasr. “In contrast with earlier times when conservatives torpedoed outreaches to the West to hamstring their moderate opponents, now they must seek stability in their relations with the world if they are to successfully consolidate power.

“For that, they must first deal with the United States.”

‘The pope needs to apologize.’ Unmarked graves near schools roil Canada.

As pressure builds for a papal apology over treatment of Indigenous children in Catholic-run residential schools, some survivors say the deep concern is to be heard – that the world “believes what was done to us.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

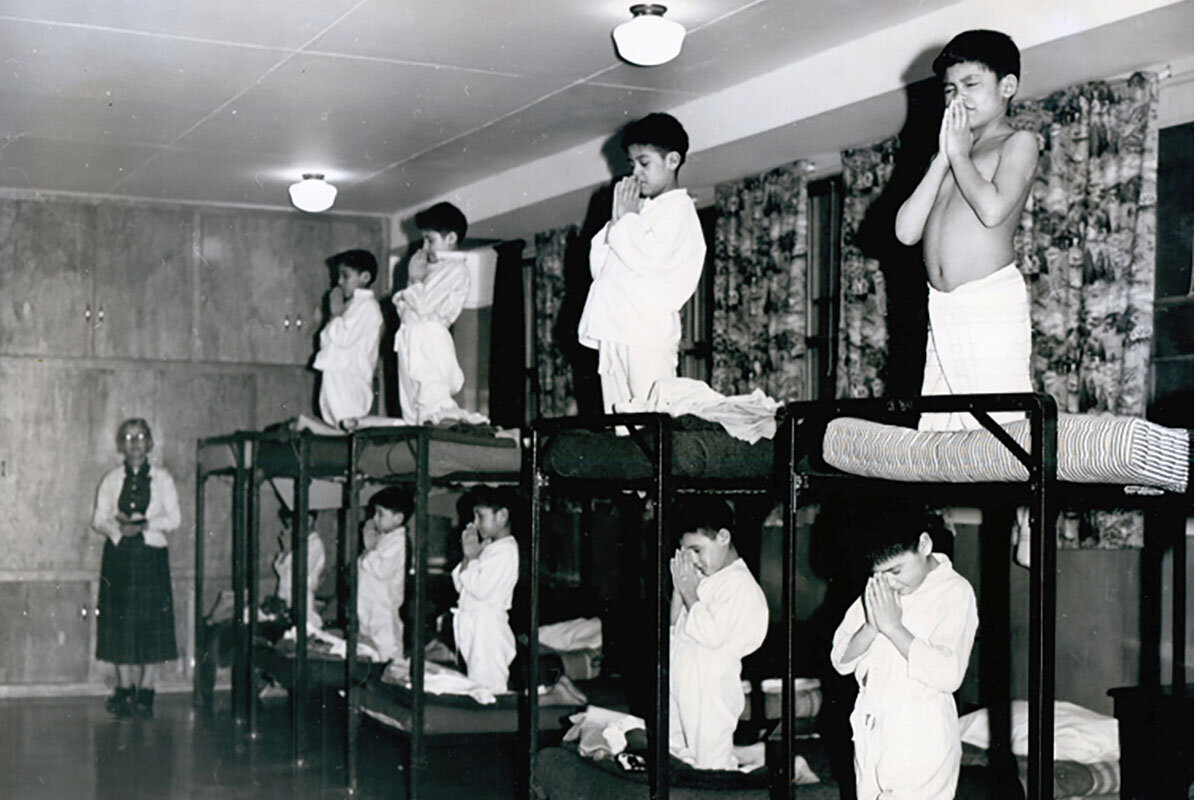

The discovery of the unmarked graves of 751 people, many children, near a Catholic-run residential school for Indigenous children has caused mounting anguish in Canada, coming as it does after the finding of a mass grave of 215 children near another Catholic-run residential school in the country.

Indigenous peoples are demanding an apology – and transparency – from the Roman Catholic Church for its participation in subjugating their cultures.

“If they are burying children in this way, not only is this a profound human rights abuse and moral question, it’s a legal question,” says Kathleen Mahoney, chief negotiator for the Assembly of First Nations during Indian residential school settlement talks. “This has become basically an existential issue, because I think now most Canadians are saying: What is going on? Who are we? … There’s a point at which the church can no longer remain silent on this.”

Wally Samuel, who attended a former residential school for seven years, says the most important part for him is the acknowledgment of the atrocity of forced assimilation. “We kept being told we’re no good,” he says, “that our languages and cultures are wrong.”

‘The pope needs to apologize.’ Unmarked graves near schools roil Canada.

In photos, it appears to be just any grassy field. But under the earth of the First Nation reserve in Saskatchewan are the plotted yet unmarked graves of an estimated 751 people, many of them children. And Indigenous leaders are demanding an apology from the Roman Catholic Church for it.

The remains were found near the former Catholic-run Marieval Indian Residential School, one of scores of government-sponsored religious institutions that forcibly removed Indigenous children from their homes to deal with what was once called the “Indian problem.”

Cadmus Delorme, the chief of the Cowessess First Nation, said at a press conference Thursday that they believe headstones were removed by a Catholic representative in the 1960s, which turns the field essentially into a “crime scene,” he said. “The pope needs to apologize.”

For over a century, an estimated 130 residential schools across Canada were operated by a variety of Christian denominations, but the Catholic Church was responsible for about two-thirds of them. And unlike the Protestant denominations, the Roman Catholic Church is the only one not to have issued a formal apology.

As Canadian anguish over the findings continues to mount, many here hope that the Catholic Church forges a more cooperative approach to addressing its role in subjugating Indigenous peoples. This discovery follows one last month of 215 children found near a Catholic-run residential school in Kamloops, British Columbia – putting pressure on Pope Francis to issue an apology and for local Catholic leaders to release all records that are available, says Kathleen Mahoney, an expert in reparations for mass human rights abuses at the University of Calgary.

“If they are burying children in this way, not only is this a profound human rights abuse and moral question, it’s a legal question,” says Ms. Mahoney, the chief negotiator for the Assembly of First Nations during Indian residential school settlement talks. “This has become basically an existential issue, because I think now most Canadians are saying, ‘What is going on? Who are we?’ … There’s a point at which the church can no longer remain silent on this.”

The news has resonated globally. This week U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet member, said the government would investigate its own legacy of boarding schools for Native Americans, including possible burial sites.

In a letter to Chief Delorme on Thursday, Archbishop Don Bolen of Regina, Saskatchewan’s capital, apologized for the “failures and sins of Church leaders and staff” and pledged to help identify the remains. “The incredible burden of the past is still with us, and the truth of that past needs to come out, however painful,” he wrote.

The letter also acknowledged their claim that headstones may have intentionally been removed by a priest.

Earlier, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops expressed the “deepest sorrow for the heartrending loss of the children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School on the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation.”

But many want a formal apology from Pope Francis, who declined to do so after being pressed by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, a Catholic, earlier this month. Instead he acknowledged the “pain” of the discovery in British Columbia.

The existence of remains has been known to Canadian society at large since at least 2015, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) concluded that Canada committed “cultural genocide” in removing 150,000 Indigenous children from their homes. An estimated 4,100 children died.

But Angela White, executive director of the Indian Residential School Survivors Society in British Columbia, says the discovery of unmarked graves has put the reality into sharp focus for Canadians.

“When you actually had [survivors] testifying at the TRC, you’re looking at the faces of those who are now 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 years of age,” she says, and people may not “comprehend that the stories they’re sharing were the memories of a child,” she says.

The government of Canada formally apologized to survivors in 2008. One of the Calls to Action from the TRC is an apology from the Catholic Church.

The recent findings have renewed pressure on the Vatican, from petitions among Catholic laypeople demanding a papal apology to health care workers asking Canadian bishops to invite Pope Francis to visit the nation and “make a public apology on behalf of the Church in Canada for our sins of commission and omission in the matter of Residential Schools.”

The controversy over a papal apology has rankled some Catholic representatives in Canada. One pastor in the Archdiocese of Kingston, Ontario, wrote in Canada’s Catholic Register that it obscures the reconciliation that has taken place between Rome and Indigenous leaders in Canada.

A priest in Mississauga, outside Toronto, came under fire for defending the “good done” by the Catholic Church in its residential schools in a sermon last Sunday.

The Rev. Michael Coren, an Anglican priest and author, has criticized the Roman Catholic Church for not apologizing, out of fear of financial repercussions and for ideology. “They’re very nervous about deconstructing the whole history of evangelism, and evangelism and colonization often went hand in hand,” says Mr. Coren. “It’s those two aspects: one purely selfish monetary and the other one philosophical and ideological.”

Ms. Mahoney says that even if there are legal implications for the allegations around unmarked graves at Catholic-run schools across Canada, in her work both in Northern Ireland (with child abuse victims in residential institutions) and with Indigenous residential school survivors, it is not reparations that survivors most seek.

“Their first desire is to tell their story and be believed ... to find out what happened to their loved ones,” she says. “The Catholic Church, for one thing, should make available all the records that they have. They haven’t done that so far.”

Wally Samuel, who lives in Port Alberni in British Columbia and attended the former residential school in that city for seven years, says the most important part for him is the acknowledgment of the atrocity of forced assimilation that is now top of mind for non-Indigenous society.

“Hopefully now the world believes our stories, believes what was done to us,” says Mr. Samuel in a phone interview. “The hardest part was trying to force Christianity on you, making you try to change and do what they believe. We kept being told we’re no good, that our languages and cultures are wrong.”

“A lot of our friends and family still practice Christianity. We don’t bother them about it. You have to respect everyone’s beliefs and religions. ... It’s important for the survivors that the church apologizes for what it did.”

A deeper look

How risky is virus ‘gain of function’ research? Congress eyes China.

If a type of scientific research could prevent another pandemic, but also risk causing one if something goes wrong, is it worth it? Questions of scientific freedom, ethics, and public health are in the balance.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Debate over so-called gain-of-function experiments – which can involve manipulating pathogens in ways that could make them more dangerous – was once largely confined to scientific journals and advisory boards.

But now, amid mounting questions about whether the COVID-19 outbreak could have started with a lab leak, it’s spilled over into the halls of Congress. At issue is whether the benefits of such research outweigh the risks, and if so, how scientific institutions and governments should best regulate it.

Lawmakers are pressing for answers about how grant proposals are evaluated by U.S. funding agencies. Specifically, they want to know whether taxpayer dollars were used to support gain of function research involving coronaviruses in Wuhan, China. The U.S. and Chinese scientists involved adamantly deny such claims.

After a three-year funding pause, the U.S. government issued new guidelines for such research in 2017. Concerns remain, however, that the review process is too subjective and lacks transparency.

“I’m worried that if we scientists ... don’t get out ahead of this, we’re going to have this legislated for us,” says David Relman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University. “The bottom line for me is that we haven’t pursued this sufficiently. Now would be a pretty good time to do this.”

How risky is virus ‘gain of function’ research? Congress eyes China.

As questions mount over whether the COVID-19 pandemic could have started with a Chinese lab leak, members of Congress are shining a bright spotlight on controversial virus research often referred to as “gain of function.”

Lawmakers are increasingly concerned that researchers who experiment with viruses in an effort to understand them and avert future pandemics could end up making them more lethal or transmissible to humans – potentially causing the types of outbreaks they were seeking to prevent. Members of Congress have especially focused on whether U.S. taxpayers funded such research in China.

At the center of the spotlight is Dr. Zhengli Shi at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, who collaborated on U.S.-funded grants that involved manipulating coronaviruses to understand their transmissibility to humans. She, her American colleagues, and National Institute of Health (NIH) officials have unequivocally rejected allegations that the work involved gain-of-function research or led to the outbreak of COVID-19, denouncing such claims as politicized misinformation.

Scientists don’t agree on how exactly to define gain-of-function research, but generally it involves enhancing a pathogen to make it more virulent or transmissible. Critics say the NIH is using a narrow interpretation of what counts as gain of function, and has not provided ample transparency into the grant review process for such research.

Debate over gain-of-function experiments involving viruses that could cause a pandemic was once largely confined to scientific journals, workshops, and advisory boards. But now, amid heightened concerns about biosafety, lawmakers see a need for greater oversight. A key ethical question is whether the benefits outweigh the risks, and if so, how scientific institutions and governments should best regulate it.

The issue came to a head last month when Republican senators led by Rand Paul of Kentucky grilled Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in a congressional hearing about the Wuhan lab’s U.S.-funded activities. Sen. Roger Marshall of Kansas compared a U.S.-China exchange of such knowledge, which could potentially be used for bioweapons, to working with the Soviet Union on nuclear technology. Two weeks later, Democrats joined Republicans in passing an amendment proposed by Senator Paul permanently banning U.S. funding of gain-of-function research in China, after which the Senate chamber erupted in cheers.

While the House and president would need to approve the measure for it to become law, the support in the Senate indicates lawmakers’ level of concern about such research and desire to establish guardrails. On June 22, Rep. Brad Wenstrup, an Ohio Republican, introduced a similar bill to ban U.S. funding of gain-of-function research in nations considered U.S. adversaries.

But scientists say it’s important for their community to take the lead so that the science is not left to Congress.

“You can’t expect a legislative aide in the middle of the night to define the technical features of the kinds of risks we’re talking about here,” says David Relman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University.

“I’m worried that if we scientists – together with the NIH – don’t get out ahead of this, we’re going to have this legislated for us,” he adds. “The bottom line for me is that we haven’t pursued this sufficiently. Now would be a pretty good time to do this.”

“One of the most dangerous viruses you can make”

In 2011, an NIH-funded researcher in the Netherlands set off alarm bells with a paper describing how he had made, in his words, “probably one of the most dangerous viruses you can make” by enhancing an avian flu virus in a way that made it more transmissible to mammals. Together with a similar NIH-funded study in Wisconsin, it triggered a debate about the risks of conducting such experiments and what could happen if that knowledge got into the wrong hands.

The work was eventually published, but a leaked letter from a member of the advisory board that reviewed it raised concerns that the NIH was more focused on extracting itself from controversy than resolving the underlying issues, a criticism the NIH rejected.

Several years later, a series of safety lapses involving avian flu, smallpox, and anthrax sparked fresh debate. In July 2014, the Cambridge Working Group, headed by Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch, called for experiments involving potential pandemic pathogens to be curtailed pending an assessment of the risks. A group calling themselves Scientists for Science pushed back with a statement of their own, arguing that such research was essential to preventing and treating disease, and noting that significant resources had already been devoted to ensuring safety, including special lab facilities.

Some scientists see additional restrictions as more of a hindrance than a protection, hampering academic freedom and potentially blocking scientific discoveries they say could save lives. Also, absent an international framework involving certification and inspections, any domestic limits could create a competitive disadvantage for the U.S., both intellectually and commercially.

“Whenever you talk about limiting scientific research or controlling scientific research, there are a lot of antibodies that come out,” says Andrew Weber, former assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical, and biological threats under the Obama administration.

But concerns were high enough that, several months later, the U.S. government put a moratorium on funding gain-of-function research involving influenza, MERS, and SARS, subject to a review period.

The moratorium was lifted in 2017, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued new guidelines for research involving “enhanced potential pandemic pathogens.” Under the guidelines, the funding agency is supposed to flag all grant proposals involving such research. Those flagged are then subject to an HHS-managed review process that must consider whether the project is ethically justifiable, whether there are any alternative methods that would be less risky but “equally efficacious,” and if not, whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks.

While oversight proponents see HHS’s 2017 framework as a step of progress, concerns remain.

Critics say funding agencies such as the NIH are essentially self-policing when deciding which proposals to flag for broader HHS review, and that the process is subjective and lacks transparency. Even some top experts don’t know the names and number of individuals on the HHS review committee, how they are appointed, or how they arrive at their decisions about whether proposed research could be “reasonably anticipated” to create, transfer, or enhance pathogens that could cause a pandemic. There is no independent biosafety authority outside the government departments overseeing the research, which increasingly include other departments besides HHS, as well as private-sector actors.

“The fact that we have no independent body that can say, ‘NIH, CDC, USDA – hey, don’t do this,’ is a problem,” says Rocco Casagrande, managing director of Gryphon Scientific, which produced a 2015 report at the NIH’s request on the risks and benefits of gain-of-function research involving influenza, MERS, and SARS in U.S. labs. “There’s no one that is without conflict of interest that can stop risky experiments.”

The Wuhan Institute of Virology

Now, the debate over gain-of-function research and lab safety has gained new urgency over questions about the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV).

Lawmakers and others are pressing for answers on the scope of WIV’s work with coronaviruses – particularly whether any of it could have enhanced their virulence or transmissibility, and if so, whether that work was funded by NIH. Growing circumstantial evidence, and particularly China’s unwillingness to release relevant information, has heightened suspicions that COVID-19 could have started with a leak from the Wuhan lab. So far, no evidence has emerged to definitively prove or disprove the lab leak hypothesis, but a wide array of scientists and government officials now say it warrants investigation.

A Trump State Department fact sheet said the WIV had a track record of conducting gain-of-function research and not being transparent about its work with viruses most similar to SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19. It added that the WIV “has engaged in classified research ... on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017.” The Biden administration has not walked back any of the fact sheet’s key assertions.

At the May 11 congressional hearing, Senator Paul questioned the wisdom of U.S. grant money funding collaboration with Chinese scientists on such research.

“You’re fooling with Mother Nature here. You’re allowing superviruses to be created,” said Senator Paul at the congressional hearing.

Dr. Fauci repeatedly and emphatically denied the senator’s assertions. “With all due respect, you are entirely incorrect,” he said. “The NIH has not ever and does not now fund gain-of-function research in that [Wuhan] institute.”

Members of Congress say he is parsing words. They have requested documents that could provide more insight into the kind of work WIV was doing, such as the original grant proposal, but so far the NIH has not released them.

In a written statement to the Monitor, the NIH said that pre-funding review of grant proposals is not made public “to preserve confidentiality and to allow for candid critique and discussion.”

“Viruses do not respect borders”

Critics such as Senator Paul have focused on Dr. Shi’s collaboration with two U.S. scientists: Ralph Baric of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), one of the world’s leading researchers on bat coronaviruses, and Peter Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance in New York, a nonprofit that seeks to prevent pandemics through its research.

In a U.S.-funded study published in 2015, Dr. Baric, using virus sequences provided by Dr. Shi, created a hybrid version of a bat coronavirus that showed the potential to infect humans. The NIH had approved the study, but it raised eyebrows among some scientists. UNC’s School of Public Health said in emails to the Monitor that there was no gain of function and the hybrid virus was not sent to China.

Dr. Shi also collaborated with Dr. Daszak’s nonprofit on an NIH-funded study published in 2017 that created hybrids between a virus which had previously been deemed as having the potential to infect humans – and others with unknown properties.

“To me, if you’re already starting with something that is poised for human emergence, you don’t go messing around with it – even if the chances of creating something bad are 1 in 100,” says Stanford’s Dr. Relman.

In written statements to the Monitor, EcoHealth Alliance and Dr. Baric defended their work as essential to preventing disease outbreaks and developing treatments and vaccines.

“There are many strains of viruses (including SARS-like betacoronaviruses) that exist in nature, and if we are to develop a drug that is broadly effective against all or most of these strains, we must be able to test such a drug against various strains in the laboratory setting,” said Dr. Baric. He says that his team’s early work enabled the U.S. to quickly find the first successful treatment for COVID-19 and contributed to the U.S. development of a vaccine.

Even with high safety standards in place, lab leaks involving viruses have led to outbreaks.

“In China, the last six known outbreaks of SARS-1 have been out of labs, including the last known outbreak, which was a pretty extensive outbreak that China initially wouldn’t disclose that it came out of lab,” said Scott Gottlieb, the former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, on CBS’s “Face the Nation.” He also noted that “mishaps” had occurred in U.S. labs.

From 2007-17, there were two dozen incidents and accidents at U.S. labs involving influenza, SARS, and MERS, according to documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act by Lynn Klotz, a senior science fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, and shared with the Monitor. Ten of those occurred at UNC Chapel Hill, all involving SARS and featuring a range of scenarios, including infected mice briefly escaping from a cabinet or a researcher’s hand.

In a statement to the Monitor, the School of Public Health said that the viruses were mouse-adapted strains that pose a lesser risk of infection to humans and that it notified the proper oversight agencies and took corrective action as needed.

“The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill takes its responsibility as a leading global research institution seriously,” the statement said. “Carolina’s researchers are committed to safety and operate under stringent biosafety and biosecurity procedures and practices.”

However imperfect the U.S. biosafety system may be, experts note, the fact that it requires such reporting and corrective actions sets it apart from China.

“That’s what we’re not seeing in China,” notes Gregory Koblentz, director of George Mason University’s Biodefense graduate program, who is working on developing an international architecture for biosafety standards, certification, and inspections. “And that legitimately feeds concerns about this type of research, because we don’t see the same kind of mechanisms for reporting and accountability in the Chinese biosafety system as we see in the U.S. and other countries.”

Amid criticism that U.S. scientists shouldn’t be cooperating on such risky research with scientists working in China, EcoHealth Alliance stressed the need for a global approach to preventing future pandemics.

“To isolate ourselves from the rest of the world would be shortsighted,” it said in its statement to the Monitor. “Viruses do not respect borders – truly effective research to identify and characterize them necessarily involves international collaboration. This is exactly the work EcoHealth Alliance does.”

Dr. Fauci also defended U.S. funding of WIV’s work on bat coronaviruses in a group Zoom call with reporters organized by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard, and said it would have been an abdication of responsibility for health officials not to study the place and animals where SARS originated.

“You need to study bat-human interface in the setting where it occurs. That’s China. ... You don’t want to study bats in Fairfax, Virginia,” he said on the June 8 call, while reiterating that the research NIH funded in the Wuhan lab had “nothing to do” with the outbreak of COVID-19.

“Having said that,” Dr. Fauci added, “we cannot account for everything that goes on in Chinese labs.”

Nicaraguans sound alarm over declining democracy. Who’s listening?

Nicaragua’s president has been shrinking space for opposition for years, but especially now, amid the pandemic. After looking away for so long, can the global community still step in?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Journalist Jairo Videa is 24 years old. But he’s already fled Nicaragua – twice.

“The persecution and attacks on my outlet have been constant,” says Mr. Videa, who continues to cover Nicaragua from exile in Spain.

Over the past month, Nicaraguan officials and police have intimidated, detained, and put under house arrest more than a dozen high-profile critics. It’s drastically deepened an already widespread chill on willingness to speak out against the authoritarian government of Daniel Ortega before November elections.

“What’s happening isn’t new; this has been going on for more than 10 years. But the global community hasn’t had its eyes fixed on Nicaragua” until this month, says Martha Patricia Molina, a lawyer who works with Nicaragua’s Pro-Transparency and Anti-Corruption Observatory, speaking to the Monitor from outside the country.

Many concerned countries have started paying attention. But others are taking notes, says Mateo Jarquín, an assistant professor at Chapman University. “The consolidation of a dictatorship in Nicaragua is both part of the Latin American erosion of democracy, but also one that really contributes to it,” he says.

Nicaraguans sound alarm over declining democracy. Who’s listening?

A former first lady. A leading independent journalist. Prominent business leaders. Five presidential hopefuls.

Over the past month, Nicaraguan officials and police have intimidated, detained, and put under house arrest more than a dozen high-profile critics. It’s drastically deepened an already widespread chill on willingness to speak out against the authoritarian government of Daniel Ortega, whose Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) is vying to extend its time in office in November presidential elections.

Observers agree there’s likely a combination of factors motivating the government to up the ante: upcoming elections; the possibility of a long-expected transition of power from Mr. Ortega to his wife, Rosario Murillo; and a pandemic that’s distracted much of the international community from human rights abuses and new laws that give the guise of legal cover to this crackdown.

“These have been days of terror. People are just glued to Twitter trying to figure out who has been arrested, who has been detained, and who might be next,” says Mateo Jarquín, an assistant professor focusing on Latin America at Chapman University in California. Homes have been ransacked, relatives of targets have been threatened, and powerful critics are leaving the country in anticipation that they might be next.

The international community is taking note. Last week, the Organization of American States condemned the government’s actions, calling for the immediate release of political prisoners. Argentina and Mexico recalled their ambassadors this week. Human Rights Watch put out a report Tuesday calling for increased pressure from the United Nations. Earlier this month, the United States enacted additional sanctions against Mr. Ortega’s daughter and a handful of top Sandinista party officials and said it will review trade relations if elections aren’t free and fair.

But with Nicaragua’s long track record of crackdowns on human rights and freedom of expression, few have a clear idea of who – or what – will help Nicaragua change course. The fragmented opposition has struggled to inspire hope. The country has suffered loss of life – and livelihoods – during the pandemic. And after the violent crackdown on largely youth-led protests in 2018, few see internal avenues to challenge the government.

“What’s happening isn’t new; this has been going on for more than 10 years. But the global community hasn’t had its eyes fixed on Nicaragua” until this month, says Martha Patricia Molina, a lawyer who works with Nicaragua’s Pro-Transparency and Anti-Corruption Observatory. “We’ve been documenting and denouncing the same kinds of human rights violations and arbitrary detentions among citizens for years. Now, the government’s touching people with more relevance at a national and international level, and the impact at the global level is stronger.”

“It’s what Ortega says”

Jairo Videa, co-founder of the independent news site Coyuntura, found himself fleeing Nicaragua for the second time earlier this year. He’s just 24 years old.

“The persecution and attacks on my outlet have been constant,” says Mr. Videa, who continues to cover Nicaragua from exile. In February, he was physically attacked and had his phone taken on the street. The next day his computer stopped working, possibly hacked. Within 24 hours he was planning his next departure – to Spain, where he was admitted to a writing program for journalists facing threats and persecution in their home countries.

“Working as an independent journalist in Nicaragua is like a game of Russian roulette. You don’t know when the police or paramilitaries will come knocking on your door,” he says.

Even leaving Nicaragua was a challenge – from the Health Ministry’s refusal to give him needed paperwork, to police and questioning at the international airport.

“Independent institutions don’t exist in Nicaragua,” says Ms. Molina. “There’s no division of power or checks and balances. ... It’s what Ortega says that goes.”

Mr. Ortega won office in 2007, after serving a separate presidential term from 1984 to 1990. Late last year, the National Assembly passed a series of laws restricting freedom of expression and giving his government greater control over the electoral process. One measure allows candidates to be barred from elections if they speak in favor of U.S. sanctions. Others make it easier to prosecute people for receiving foreign funding or leaking “false” information. Rights groups inside the country report that at least 124 people perceived as critics are under arbitrary detention.

The government succeeded in “formally criminalizing various forms of dissent and civil society activity, labeling it money laundering, treason, conspiracy,” says Dr. Jarquín. “Clearly we didn’t pay enough attention to that at the time [in the midst of the pandemic]. ... And now we see how efficient the state has been in using these laws to speed up detentions. It helps them communicate a narrative to their base. It’s a very cynical narrative, but it’s coherent: ‘These people are laundering money. They received it from the U.S. and they send it to all their friends and NGOs to make themselves rich. They go to the U.S. and ask for sanctions. They’re clearly treasonous.’”

Pressure from abroad?

Mr. Ortega’s party maintains about 25% popular support, according to a CID Gallup poll released in February. Dr. Jarquín says the opposition’s failure to propose a coherent alternative explains FSLN’s ongoing support – though he adds that it’s never too late to come together.

And although multilateral pressure on Nicaragua is important, he says, “if you’re going to pressure the regime, you need to create incentives for democratic opening,” which he doesn’t see amid the current barrage of sanctions and removing ambassadors.

Ms. Molina says the international community has a fundamental role to play, starting with sanctions – preferably against individuals, so that normal citizens are spared increased economic difficulties. Nicaraguans, she says, can no longer do much.

“As a Nicaraguan, if we raise our voice at this point, it means jail, it means torture, it means violations of our rights,” Ms. Molina says. She’s currently outside the country and says that’s the reason she feels comfortable speaking openly about the situation. Repeated interview requests by The Christian Science Monitor to analysts, academics, and journalists inside Nicaragua were declined due to the personal risks involved.

There are risks for the international community in not taking action: increased migration, for example (some 108,000 Nicaraguans have fled since the 2018 crackdown, according to the U.N. refugee agency), and a further weakening of democracy not only in Nicaragua, but also in the region.

“The consolidation of a dictatorship in Nicaragua is both part of the Latin American erosion of democracy, but also one that really contributes to it,” says Dr. Jarquín, who says neighboring countries like Honduras, Guatemala, and more recently El Salvador have been slow to condemn Mr. Ortega’s actions because they’re busy taking notes, condemning their own nations’ civil society groups as working against the state.

Nicaraguans are looking for glimmers of hope where they can find them. For Ms. Molina, it’s youth. “We’re coming at politics with a different mentality than our predecessors. We’re more informed. We aren’t passive citizens,” she says.

Mr. Videa, the young journalist, chuckles when he says it’s his own dreams that give him hope. “My hope is myself. I want a future, I want to be a professional, I want a home, and to build my team writing independent news stories.”

Dr. Jarquín says that, as an academic, he’s less inclined toward optimism. But “repression is expensive, and it creates problems and it creates resentment,” he adds. “You can’t do it forever.”

Books

Beach-worthy books to savor in summer: Monitor staff picks

What do reporters and editors read over their summers? We asked the staff to share their go-to books for laid-back days. They offered suggestions that span many genres and moods.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Staff

“Summer afternoon,” wrote Henry James, “to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language.” To that pairing, the Monitor staff might add a third: reading. It’s only natural that people concerned with writing and editing would be passionate about reading, and a glimpse into the preferences of the staff reveals a range of choices for summer book lists. From classics such as “The Great Gatsby” and “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” to the ever-popular Harry Potter books and essays by humorist David Sedaris, a rich variety of book suggestions awaits.

Beach-worthy books to savor in summer: Monitor staff picks

Summer afternoons are best spent in a comfy, shaded spot, a glass of lemonade at hand, engrossed in a book. We asked Monitor staff to share their summer favorites.

I spend a lot of time in upper Maine, and nearby is the Big Chicken Barn, one of those huge junk/antiques/old books barns that dot New England. Two summers ago I picked up a used copy of the first volume of “A Dance to the Music of Time” series by Anthony Powell for some reason. “A Question of Upbringing” is a novel that portrays a sort of social realism for upper-class England starting in the 1920s, going through World War II, and into the ’50s and ’60s. I could not put it down, and over a year and a half I tracked down the rest of the series (it’s a 12-volume set) and read the whole thing as a great antidote to the 2020 election chaos in Washington.

My wife even bought me a Powell biography that also identifies the real people behind all the characters.

Powell was probably better known back in the 1970s as a friend of Martin Amis and George Orwell, etc. I picked it up because I’d heard the book referenced in some class I took as an English major, lo, those many years ago.

I know this is a kind of weird summer read, but I found it immensely relaxing.

– Peter Grier, senior Washington correspondent

Last year, books about race flew off bookstore shelves. “The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother,” a memoir by James McBride, fell into my lap, a castoff from a relative who was cleaning house. I was immediately hooked by McBride’s prose and the mysteries of his fierce Jewish mother, who raised 12 Black children without ever discussing race. Entangled in this rich, yet breezy memoir are threads of what it means to be an “other” that echo loudly 25 years after its original publication.

– Noelle Swan, Weekly editor

I bought Wayétu Moore’s “She Would Be King” in the early fall of 2018 at a book festival in St. Louis. The cover’s hues of serene blues and an illustration of a dark-skinned woman with fiery red hair caught my eye. Moore’s captivating prose weaves in and out of time and place from Virginia to Monrovia, Liberia, telling the story of warriors and heroes with supernatural abilities designed for liberation. And at the end, the tales of survival and rebirth made me, a person of Liberian heritage but estranged from that part of my identity, feel just as full of a resurrected hope as the characters Moore made.

– Ashley Lisenby, multimedia reporter and writer on race and equity

While renting a house in coastal Rhode Island years ago, I saw a worn copy of Pat Conroy’s “The Prince of Tides.” The fact that it had been made into a major motion picture almost discouraged me from reading it, but when I opened the first page, Conroy’s musical descriptions of the South Carolina coast pulled me in. I’ve been a fan of his ever since.

Something I’ll be reading this summer: I’m a big fan of the short story, and have had T.C. Boyle’s “Stories II: The Collected Stories of T. Coraghessan Boyle” in my bookcase for several years. I’ve been avoiding it because it’s 900 pages long, but I started this week and am enjoying it so much I ordered a used version of the preceding volume, “Stories: The Collected Stories of T. Coraghessan Boyle” from my favorite used book store – another 800 pages.

– Greg Fitzgerald, communication manager

The American coming-of-age story, “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” sat on the shelf in my childhood home, but I didn’t get to it until recently, when my book club decided to read a “classic” for a change. No wonder Betty Smith’s novel became an immediate bestseller when it was first published in 1943. Rich in detail and heart, it takes you to the tenements of Brooklyn in 1912, where 11-year-old Francie Nolan collects junk for pennies with her brother, their practical mother scrubs floors to keep a roof over their heads, and their charming, singing-waiter father battles drink. But Francie finds beauty among the ashes, resilience in hardship, and love in flawed people. Just like the tree that grows from cement outside her window, she thrives.

– Francine Kiefer, West Coast bureau chief

You know that old saying about how everyone wants to write a book? (I mean, I’m one of those wannabes myself.) Lily King’s “Writers & Lovers” cuts right through the cliché. The story follows a woman in her 30s navigating the anxieties and absurdities of life as an aspiring novelist. But despite its all-too-real portrayal of the agony of writing – not to mention trying to get published – the book somehow made me want to risk the attempt even more. Maybe it was the pleasant tinge of ’90s nostalgia throughout (the story is set in 1997), or the aching vulnerability of the main character, Casey. Either way, a great read for those who love to write – or want to understand people who do.

– Jessica Mendoza, multimedia reporter

“Harry Potter” is synonymous with summers in Maine for me. Our three sons were just the right age for the books as they arrived – in a brilliant bit of marketing – one by one every July, Harry’s birthday month. We’d often be visiting the boys’ grandparents then. We’d rush out to buy the latest volume and race home to start reading it aloud in the electronic media-free home. Even better was when the audio version arrived. Then we’d pile into the family van after dinner and go for “‘Harry Potter’ rides,” listening to the cassettes as the sun set and the moon rose through pine trees and across seascapes on the winding rural roads of Downeast Maine.

– Owen Thomas, The Home Forum editor

The feeling of summer starts in the first paragraph of “Beautiful Ruins,” when “shards of sunlight broke on the flickering waves.” But that’s not all that makes this a favorite vacation read. There’s the “dying actress” in her wide-brimmed hat, the scenes of the Italian coast, the love stories across time and place, the laugh-out-loud trials of a young Hollywood script reader – and above all, author Jess Walter’s glistening sense of satire and humanity.

– Stephanie Hanes, environment writer

One of my favorite books is set at Walden Pond, my favorite Massachusetts swimming spot. Little-known fact: Henry David Thoreau once accidentally burned 300 acres of the surrounding woods. The inferno also threatened the nearby town of Concord. This 1844 incident inspired John Pipkin’s literary novel “Woodsburner.” The tale follows Thoreau and several fictional characters as the encroaching blaze transforms their lives and their way of thinking. Since its 2009 release, this page-turner has largely been forgotten. But its story is indelible.

– Stephen Humphries, chief culture writer

I never knew comics could attain the power of great literature until I came upon the work of Yoshihiro Tatsumi. The Japanese artist pioneered a realistic, socially conscious style of manga, called gekiga, in the 1960s and ’70s. His two collections, “Abandon the Old in Tokyo” and “Good-Bye,” often explore the inner crisis of working-class men amid Japan’s postwar economic boom. Taut and cinematic, Tatsumi’s stories are about things people don’t want to admit to themselves, yet you can’t look away.

– Jingnan Peng, multimedia producer

If you are looking for a read that goes down as smoothly as green grapes on a hot beach, pick up Alexander McCall Smith’s series “The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency.” It follows the adventures of Precious Ramotswe, Botswana’s premier lady detective. Mma Ramotswe wants nothing more than to help people by solving their problems, er, mysteries. You won’t want to stop once you start. It’s a good thing you’ll have the summer to catch up and get ready for the 22nd installment, “The Joy and Light Bus Company,” which will be released this fall.

– Kendra Nordin Beato, staff editor and writer

David Sedaris’ essays impel me to read aloud and laugh communally – at the beach, on a road trip, and sometimes at the dinner table. “The Best of Me” is his umpteenth anthology, but his acid-eyed candor (sparing no one, including himself) and compassionate heart bring a fresh, absurdist lens to the unexpected – from sensible French health care to heady American real estate.

– Clara Germani, enterprise and development editor

As a novel that’s become emblematic of the original Roaring ’20s, “The Great Gatsby” may be suited to a summer that could herald the start of another age of excess, as the pandemic recedes. But F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel isn’t a paean to hedonism. Far from it: Jay Gatsby’s quest ends in failure and death. His gauzy parties are tragicomedies, seen through the eyes of narrator Nick Carraway. I read and reread “The Great Gatsby” for its deft storytelling and probing of the morality of its era, one both remote and recognizable a century on.

– Simon Montlake, senior writer

When genius architect-turned-recluse Bernadette Fox disappears, her teenage daughter must find out where she’s gone – and where she came from. Humor and warmth pervade Maria Semple’s second novel, which offers a sharp satire of the Seattle elite and a moving tale of a mother-daughter bond. Told in part through police reports, TED Talk transcripts, and private emails between PTA moms, “Where’d You Go, Bernadette” is tough to put down.

– Lindsey McGinnis, junior editor

The sparkly, paint splotched cover of “Untamed” by Glennon Doyle called out to me when I was stranded in the Wi-Fi dead zone that was my new apartment. In this bestselling memoir, Doyle takes you through a journey of self-discovery and courage. Mundane snippets of everyday life – from airports to soccer practice to phone calls – are woven with the color of Doyle’s innermost thoughts on relationships, work, and family. “Untamed” reveals the hidden superpower in us all: “our Knowing.” The lessons on how to harness this superpower are shared, not in the demanding tone of a coach on the sidelines, but in the tender voice of a sister giving advice. I was left feeling empowered to examine my own social conditioning and with the weird desire to sit in silence with the whirlwind of my own thoughts.

– Tara Adhikari, intern

I have two history reads from last summer. My husband and I went on a cross-country road trip and one of our stops was Kansas City, Missouri, to see the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum, which are right next door to each other in the city’s historic district. As a result of that visit I picked up two books. The first was “The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant” by Robert C. Cottrell. Many baseball fans know about Satchel Paige and the great ball players from the Negro Leagues, but not as much about the founder of the league. The business guy behind it all has a story as well.

The second book was “Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era,” a collection of essays about the city in the years between the two world wars.

– Mary Ann Lomascolo, Project Management office manager

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A rise in refugees, a need for solutions

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Last year, the number of people who fled violence and persecution worldwide rose for the ninth year in a row, reaching 1 in every 95 people. The swell of migrants is now pushing many countries to both tighten their borders and try to solve the crises creating refugees. Are any of these efforts working?

Perhaps the best example in solving a refugee-producing crisis is in Libya, which has been largely unstable since a 2011 uprising against a dictator. A Germany-led effort to end an internal conflict in the North African country – and stop it from being a transit point for migration to Europe – has showed good success since an October cease-fire. In February, a transitional government was set up to unite contending factions. At a conference in Berlin on Wednesday, further progress was made in planning for the pullout of 20,000 foreign fighters backed by Russia and Turkey and for a crucial election in December.

On June 20, the world marked the 70th anniversary of an international treaty to prevent refugees from being forced back into a conflict zone. That treaty has largely worked. Now the world’s focus is on solving or preventing conflicts.

A rise in refugees, a need for solutions

Last year, the number of people who fled violence and persecution worldwide rose for the ninth year in a row, reaching 1 in every 95 people. The swell of migrants is now pushing many countries to both tighten their borders and try to solve the crises creating refugees. Are any of these efforts working?

In the United States, Vice President Kamala Harris visited the southern border Friday, her first visit as the federal official now in charge of curbing an upsurge of migrants into the U.S. Her work to improve conditions for people in Central America could take years and more money from Congress to lift up the region.

In Africa, 16 countries decided Wednesday to send troops to Mozambique, a hot spot of terrorist attacks, in order to prevent a flood of refugees into neighboring nations. More than 800,000 people have already been displaced there.

In Southeast Asia, neighboring countries of Myanmar are trying to prevent an influx of refugees fleeing a domestic conflict between armed pro-democracy rebels and a military that took power five months ago. So far, they have failed to persuade the ruling junta to share power.

In Afghanistan, the coming withdrawal of U.S. forces has forced President Joe Biden to plan for the evacuation of 18,000 Afghans who have worked with American forces. He and other world leaders are also trying to bolster the elected government in Kabul to prevent an exodus of Afghans fleeing the expected expansion of Taliban rule.

Perhaps the best example of progress in solving a refugee-producing crisis is in Libya, which has been largely unstable since a 2011 uprising against dictator Muammar Qaddafi.

A Germany-led effort to end an internal conflict in the North African country – and stop it from being a transit point for migration to Europe – has showed good success since an October cease-fire. In February, a transitional government was set up to unite contending factions. At an international conference in Berlin on Wednesday, further progress was made in planning for the pullout of 20,000 foreign fighters backed by Russia and Turkey and for a crucial election in December.

The next step for Libya’s unity government is to agree on a constitutional framework for the elections. “Libya’s fresh political leadership and the country’s energetic but beleaguered civil society, can make a difference,” one U.S. official said after the conference.

On June 20, the world marked the 70th anniversary of an international treaty, signed by most countries, to prevent refugees from being forced back into a conflict zone. That treaty has largely worked. Now the world’s focus is on solving or preventing conflicts. Libya’s progress shows what can be done.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Me? Beautiful?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kaily Johnson

Bullied for years because of her appearance, a teen disliked what she saw when she looked in the mirror. But the realization that true beauty is spiritual and God-given to everyone brought lasting peace and happiness with who she is.

Me? Beautiful?

From the time I was in second grade, I was bullied for my freckles and had a deep hatred of my skin. Other kids called my freckles ugly, and one boy told me that my face made him feel sick. Once I started middle school, the bullying morphed to judgment and gossip.

When I was in sixth grade, I discovered makeup could completely mask my freckles. Soon, I was completely relying on makeup to feel beautiful, and the more coverage I had, the more comfortable I felt.

A couple of years later, when my mom found out I’d been secretly covering up my freckles, it broke her heart. She explained to me that I could love and appreciate my individuality. I had never thought of being “different” in a positive light, so I was taken aback.

She reminded me of what I’d learned in the Christian Science Sunday school: that my identity is not a physical image in a mirror, but truly God’s perfect spiritual reflection, because God made each of us in His image. There is nothing ugly or gross about God, because God is completely good. So there couldn’t be anything ugly or gross about me, because I am the expression of God.

It was hard for me to see myself as a perfect reflection, because whenever I looked in the mirror, I hated what I saw. So I realized I had to make a choice about what I was going to believe. Either my identity was just what I saw on the surface, or my identity was God-based and completely spiritual. If my being is spiritual, then beauty must be included in my identity, because beauty is a quality of God. This beauty is not my hair, my clothes, or my skin. My beauty is my God-given individuality and being true to the way God made me.

The summer between eighth and ninth grades, I prayed regularly about beauty and identity. I tried to shift my focus away from myself by thinking more about God and about others. I spent a lot of time just being grateful. Soon, these thoughts outweighed the self-focused thinking that had dominated for so long, and I began to feel a lot more secure, peaceful, and happy.

The first day of freshman year, I came to school with a makeup-free face. At least one person from each of my classes complimented my skin, and I made friends that I was able to be unapologetically myself around.

Now it’s years later, and I almost never wear makeup. I embrace my freckles, because they’re a symbol of the way I’ve learned to love my individuality. I’ve discovered that what’s really important is learning more about, and being true to, my spiritual identity. After all, since I’m the image of God, why would I want to change that?

Adapted from an article published in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Oct. 9, 2018.

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Sign up for the free weekly newsletters for this column or the Christian Science Sentinel, a sister publication of the Monitor.

A message of love

Capturing the moment

A look ahead

Come back Monday, when we’ll have a story about inequality in nature – how some U.S. children grow up with access to wilderness but others face barriers that shut them out.