- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Trial by wildfire, and a verdict that offers redemption

As extreme heat and wildfires again test the western U.S., including the country’s northwest corner – where Portland hit an all-time record on Saturday, then broke it Sunday with 112 degrees F. – Oregon Gov. Kate Brown has cleared a path for redemption.

She moved last week to commute the sentences of 41 men and women who helped fight last year’s blazes, which burned more than a million acres in her state and took some 4,000 homes. There are terms of eligibility, including good conduct while incarcerated and a plan for housing after release. The candidates are assessed to ensure low community risk.

The personal risks taken by those on the front lines of wildfire containment are, of course, towering. Professional “hot shots” are venerated symbols of what has become a seasonal war.

For help, some states have long reached into prisons. California, which has more than 40 prison fire camps, has stirred controversy for decades with pay that amounts to just dollars a day. The acquired skills haven’t been easily transferable to life on the outside, either – though a track to professional firefighting did get some help from legislation passed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last September. (Colorado, too, is pushing on that front.)

In Oregon, where the first releases under Governor Brown’s plan could come next month, trial by wildfire has led to a kind of compensatory justice, and a chance to redefine people who’ve made mistakes as valued participants, too, in an effort to help.

“The governor recognizes that these adults in custody served our state in a time of crisis,” a spokeswoman said, “and she believes they should be rewarded and acknowledged” for that.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How Joe Biden is navigating a Catholic Church in conflict

Catholic voters, like the rest of the U.S., are increasingly polarized around issues like abortion – creating a challenge for Mr. Biden, the nation’s second Catholic president.

That a deep Catholic faith infuses President Joe Biden’s life is hardly a secret. His election in 2020 as only the second Catholic U.S. president was almost unremarkable – a stark contrast with John F. Kennedy, who had to fight hard in 1960 to overcome America’s history of anti-Catholicism.

Now President Biden’s faith is center stage. His Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, met with Pope Francis at the Vatican today.

In a burst of controversy, Mr. Biden’s stance on abortion rights – increasingly liberal over the years – returned to the headlines after the conservative-dominated U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops voted overwhelmingly to draft guidance on the Eucharist, or communion. The move was widely seen as an effort by conservatives to encourage exclusion of Mr. Biden from the ritual over his political posture on abortion.

According to the Pew Research Center, Catholic voters are split on the matter. Some 87% of Democratic Catholics side with Mr. Biden, while only 44% of Republican Catholics do – a disparity that mirrors the larger polarization of U.S. politics.

“In this country, the two-party system has created a two-party Catholic Church,” says Massimo Faggioli, a professor of theology at Villanova University in Philadelphia.

How Joe Biden is navigating a Catholic Church in conflict

Every weekend, almost without fail, President Joe Biden goes to church. If he’s in Washington, he attends Mass at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown. If he’s at home in Wilmington, Delaware, he goes to his family parish, St. Joseph on the Brandywine.

In his victory speech last November, President-elect Biden cited the popular Roman Catholic hymn “On Eagle’s Wings,” and in his inaugural address in January, he quoted St. Augustine. The president often carries a rosary that belonged to his late son, Beau.

That a deep Catholic faith infuses President Biden’s life is hardly a secret, his election as only the second Catholic president almost unremarkable. The contrast with John F. Kennedy’s election in 1960 is stark: The senator from Massachusetts had to fight hard to overcome America’s history of anti-Catholicism. For Mr. Biden, the strong Catholic identity may have been a plus in key Rust Belt states last November.

Now, the president’s faith is center stage. Today, his top diplomat – Secretary of State Antony Blinken – had a private audience with Pope Francis at the Vatican, in a reset of U.S.-Vatican ties after the uneasy Trump era. Mr. Biden himself is expected to meet with the pope in Rome in October.

And in a burst of controversy, Mr. Biden’s stance on abortion rights – increasingly liberal over the years – returned to the headlines after the conservative-dominated U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) voted overwhelmingly to draft guidance on the Eucharist, or communion.

The move was widely seen as an effort by conservatives to encourage exclusion of Mr. Biden from the ritual over his political posture on abortion, based on comments from prominent bishops. On June 21, the USCCB released a Q&A clarifying that the vote was not specific to any individuals. Notably, the word “abortion” does not appear in the one-page document.

A “two-party” church

Still, a larger conflict remains: Rank-and-file American Catholics, a shrinking congregation like most traditional faiths in the U.S., are increasingly at odds with church leadership.

Only one-third of U.S. Catholics believe the core teaching that the bread and wine during communion literally become the body and blood of Jesus Christ, according to a Pew Research Center poll. And two-thirds of American Catholics say Mr. Biden should be allowed to receive communion, despite his abortion politics.

The percentages vary widely by party. Some 87% of Democratic Catholics side with Mr. Biden, while only 44% of Republican Catholics do, Pew found. This disparity mirrors the larger polarization of U.S. politics as well as increasing polarization within the church, say experts on U.S. Catholicism.

“In this country, the two-party system has created a two-party Catholic Church,” says Massimo Faggioli, a professor of theology at Villanova University in Philadelphia and author of the new book “Joe Biden and Catholicism in the United States.” “The political divisions in this country have created a sectarian mentality within Catholicism.”

Professor Faggioli draws a parallel between the political behavior of increasingly conservative white Catholics in the U.S. and white evangelicals. About 6 in 10 non-Hispanic white Catholic voters are now Republican, up from 4 in 10 in 2008, according to Pew. Among non-Hispanic white evangelicals, a mainstay of the GOP, 8 in 10 voted for Donald Trump both in 2016 and 2020.

The Southern Baptist Convention – the nation’s largest Protestant denomination – has been going through its own cultural upheaval, in its case over race, gender, and politics. At the SBC’s recent annual meeting, the denomination narrowly averted an ultraconservative takeover.

“The situation is similar” but not identical, says Professor Faggioli. Catholics, he notes, are unlikely to split into two churches, as the Baptists did in the mid-1800s over slavery. “I believe there’s a sense of unity in the Catholic Church that we’re still holding, but I’m not sure about the future. I think what’s happening is a soft schism.”

LGBTQ rights are another point of contention. The pope made headlines last October when he endorsed same-sex civil unions. Mr. Biden is an even more liberal ally, endorsing same-sex marriage as vice president before President Barack Obama did. In 1960, when Mr. Kennedy was running for president, the concern over Catholicism centered on fear of Vatican influence in the U.S. government. The big political issue was prayer in schools, not abortion or gay rights.

Today, church politics and U.S. politics are intertwined. Before the U.S. bishops voted to draft communion guidance, the Vatican warned them against taking steps that could lead to denial of the sacrament to politicians who support abortion rights. The issue is relevant to other pro-abortion-rights Catholic politicians, including Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and former Secretary of State John Kerry, now Mr. Biden’s special climate envoy. Both have faced calls from bishops for denial of communion, including when Mr. Kerry was the Democratic presidential nominee in 2004.

Decisions to grant or deny communion are ultimately made by the local bishop. In 2019, as a presidential candidate, Mr. Biden was denied communion by a priest in South Carolina. But despite the conservative tilt of the USCCB, President Biden has not been in danger of losing access to communion either in Washington or Wilmington, where the relevant bishops lean liberal.

Mr. Biden has said little publicly about the issue. When asked about the U.S. bishops’ vote to draft a communion statement and the potential for a rift in the Catholic Church, he said, “That’s a private matter, and I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Biden’s evolving abortion stance

Complicating matters is the return of abortion politics to the U.S. Supreme Court. Now with a 6-3 conservative majority, the high court has agreed to hear a Mississippi case this fall that could significantly pare back the right to abortion under the 1973 precedent, Roe v. Wade.

The case has energized activists on both sides ahead of the 2022 midterm elections, and shines a light on Mr. Biden’s increasingly liberal position on abortion.

As a senator, Mr. Biden used to emphasize that he personally opposed abortion while refusing to impose his views on others. Now he espouses the mainstream Democratic position emphasizing women’s rights. Two years ago, Mr. Biden abandoned his long-held opposition to a ban on federal funding for most abortions.

In American politics, Democrats who identify as “pro-life” are a vanishing breed, as the two parties become more homogeneous. Even defining the “Catholic vote” can be difficult. In the 2020 election, voters who self-identified as Catholic split nearly evenly between Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump. But one expert on Catholic voters says there’s a split between “practicing Catholics” – that is, those who attend Mass weekly and follow all church tenets, including on abortion and same-sex marriage – and others.

George Marlin, author of “American Catholic Voter: Two Hundred Years of Political Impact,” says that practicing Catholics helped Mr. Trump to victory in key 2016 battleground states, and President Trump won the “practicing Catholic vote” in 2020.

Mr. Marlin also defends the U.S. bishops in their decision to issue a statement on the Eucharist. “They have an obligation to spell out directly the teachings of the church,” he says. “No one forces people to be Roman Catholic. You can’t have your cake and eat it too.”

His comment hints at the past statement of a high-ranking U.S. cleric that a “smaller, lighter” church of purer belief would be preferable to one that is larger and less faithful to the full range of church teachings.

Conservative Catholics’ emphasis on abortion does put pressure on lay Catholics to choose sides, liberal church activists say. Sister Simone Campbell – head of the Network Lobby for Catholic Social Justice, who offered a prayer at the 2020 Democratic convention – said in January that the “political obsession” with the “criminalization of abortion” has broken the church apart.

When asked last year by the Catholic News Agency whether her organization opposes legal abortion, Sister Simone responded, “That is not our issue.”

U.S.-Vatican relations

In the U.S.-Vatican relationship, smoother sailing is expected under President Biden than under President Trump, both in style and substance – though perspectives still diverge at times. In Secretary Blinken’s meeting Monday with the pope and top Vatican officials, “there is a deep and long laundry list of issues to talk about,” including climate change, refugees, and China, says Shaun Casey, who served as U.S. special representative for religion and global affairs under President Obama.

The Vatican welcomed the U.S. return to the Paris climate accord, but the China question is trickier, following a 2018 deal allowing the Vatican to appoint bishops in China.

“In countries where the Catholic Church is a tiny, oppressed minority, the goal of their diplomacy is to make life easier for the faithful,” which differs from the U.S.’s much broader agenda with China, says Professor Casey, director of the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University.

Still, he adds, the Vatican is a “strong advocate for religious freedom for all people,” including China’s oppressed Uyghurs.

Back in the U.S., the larger controversy over Mr. Biden and communion has not only served to highlight intra-church conflicts – but could also engender sympathy for a president whose Catholic faith infuses his life and has provided comfort at times of personal tragedy.

“Catholicism is at his core,” says Bobby Juliano, a longtime Washington lobbyist who has known Mr. Biden and his family since 1973.

In a 2007 interview with the Monitor on his faith, then-Senator Biden said he was troubled by church sex-abuse scandals involving children, but his commitment to the church was unchanged.

“This is my church as much as it is the church of a cardinal, bishop, or janitor,” he said, “and I’m not going anywhere.”

A deeper look

How race shaped the South’s punitive approach to justice

Home to more than half of America’s Black population, the South has taken a severe approach to criminal justice. Understanding that link is key to breaking a cycle of poverty to prison.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

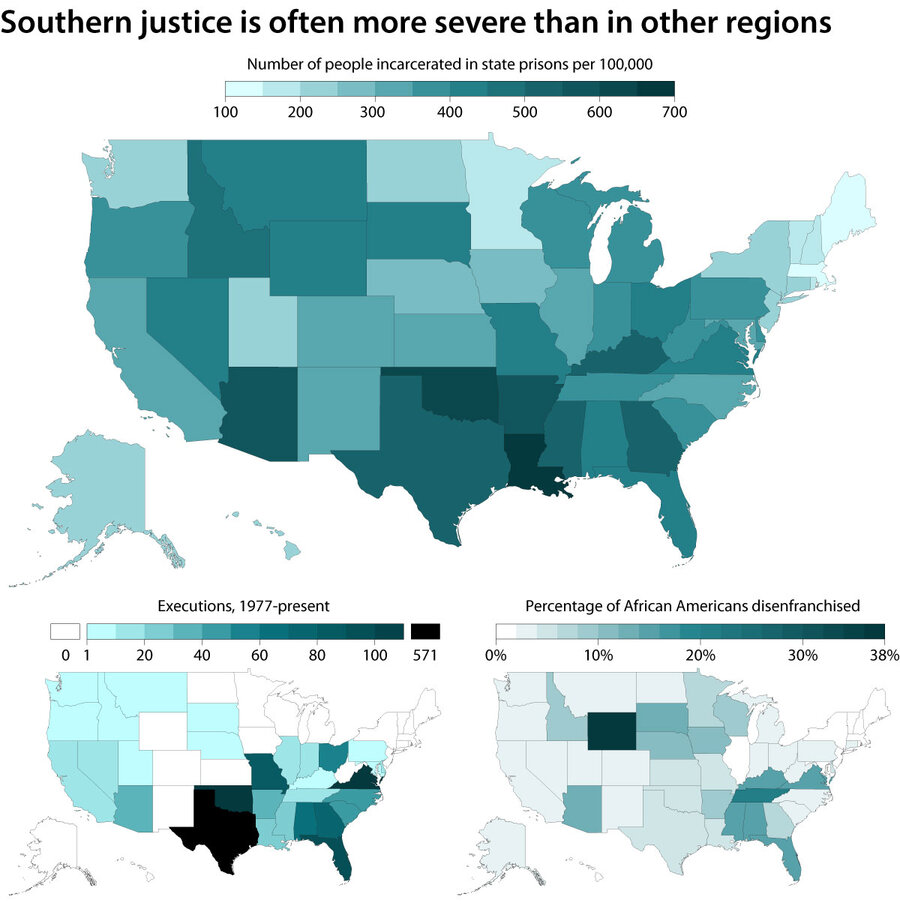

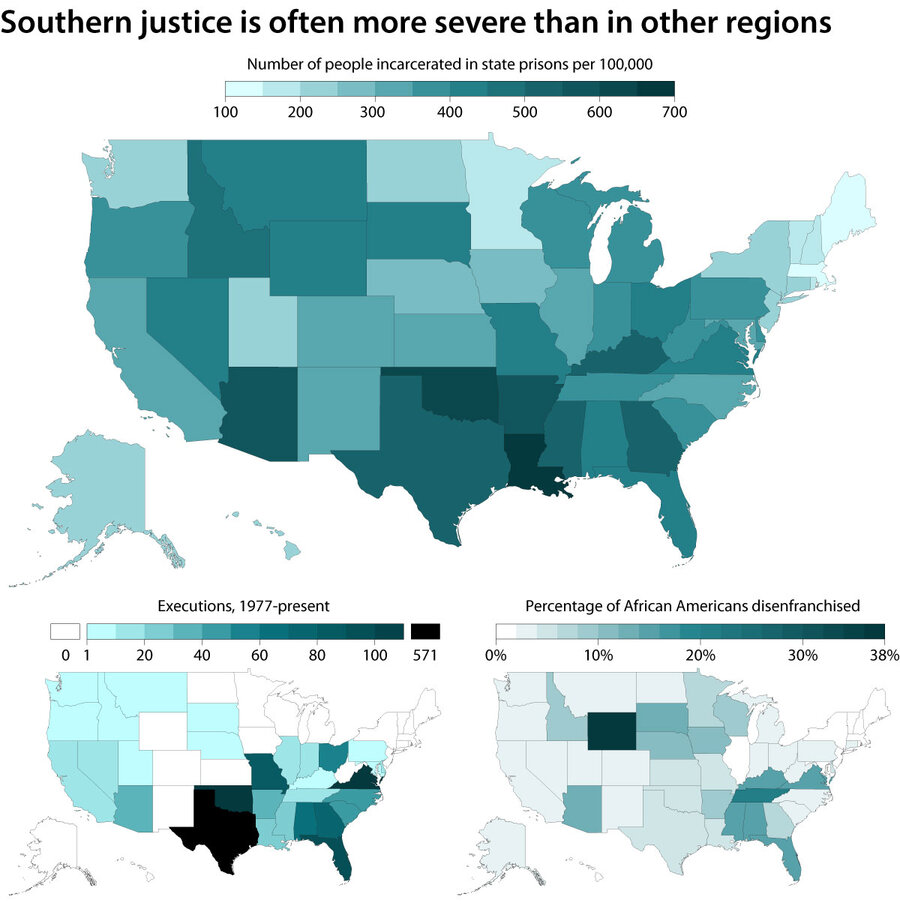

The portrait of criminal justice in the South is one of severity. Many states embrace get-tough sentencing laws. No other area of the country puts a greater share of defendants in detention before a trial starts. Alabama’s male prison system is being sued by the federal government over allegations that it is unconstitutionally inhumane. Since the 1970s, Southern states have used the death penalty more than the rest of the country combined.

Southern justice is strongly punitive across the board, but as home to some 55% of America’s Black population, the region has created a justice system inextricably intertwined with race. Racist origins continue to cast a shadow over the system, while deeply impoverished areas fuel a vicious cycle of poverty to prison.

The way forward is to unwind how race has shaped the system and to address it head-on, says Leah Nelson, research director at Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice. “We inherit the consequences. We can try to fix them.”

How race shaped the South’s punitive approach to justice

Champ Napier is the exception.

From his birth in Prichard, Alabama, the third-poorest city in America, he faced an uphill climb just to stay out of poverty and prison. Mr. Napier remembers the Ku Klux Klan burning crosses on his schoolyard, white residents yelling obscenities at his school bus. The site of the last recorded lynching in 1981 is in nearby Mobile.

As a teen, he quit high school to sell drugs, thinking it was the fastest way out of poverty. When a drug deal went wrong, he shot a man six times. At 18, he was sentenced to life in prison for first-degree murder.

But 15 years inside Alabama prisons bred a determination to find a new path. And in 2015, more than 10 years after his parole, he became the first-ever Alabamian convicted of murder to receive a complete pardon. Now he works as a client advocate for the Mobile County Public Defender’s Office to help others avoid a system he barely survived.

“Our rite of passage shouldn’t be from poverty to prison,” says Mr. Napier.

His story speaks to the challenges of breaking that vicious cycle, particularly in the South. Nationwide, that cycle has contributed to Black people being imprisoned at five times the rate of white people. Moreover, studies show that Black people are also routinely sentenced more harshly for the same crime.

But in the South, where more than half of all Black Americans live, these trends are amplified by historical racism, higher rates of poverty, and a more punitive justice system. The South includes 8 of America’s 10 most incarcerative states, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics data compiled by The Sentencing Project.

The path to addressing racial issues within the criminal justice system starts with understanding where those issues came from, says Leah Nelson, research director at Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice.

“It’s so important to look at those things and see the society that we live in now as a consequence of [decades] of structural racism that replaced slavery and Jim Crow,” says Ms. Nelson. “We inherit the consequences. We can try to fix them.”

A portrait of Southern justice

The general portrait of the justice system in the South is one of severity. What makes the region different is its support for harsh penalties, says Michael Jackson, district attorney for Dallas County in Alabama.

Florida requires everyone convicted of a crime to serve at least 85% of their sentence, producing one of the country’s oldest incarcerated populations. Louisiana, dubbed the incarceration capital of the world, is one of two states that mandates life without parole for even second-degree murder. Three-strike laws, like Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act, permit life sentences for low-level crimes if a defendant has multiple felonies on record.

The death penalty is legal in all but one Southern state, and since the 1970s the region has used it more than all other states combined.

In addition, many in detention have not been convicted.

Around 70% of people in U.S. jails are there because they can’t afford bail or were placed in preventive detention, says Jeremy Cherson, a senior policy adviser at The Bail Project. The South has the highest pretrial detention rate in the country.

And former prisoners who do reenter society often face greater hurdles in the South. Of the 10 states with the highest rate of disenfranchising those convicted of a felony, nine are in the South.

The Sentencing Project, Death Penalty Information Center

This creates a gravitational pull, making it hard for those in the system to get out. For Black Southerners, that includes the significant pull of history.

In 1704, the Carolinas enacted the Colonies’ first slave patrol, and its neighbors soon followed. By the century’s end, the U.S. Congress had passed a fugitive slave law, and every slave state had a slave patrol. Out of these grew the region’s police forces and criminal codes, regularly affirmed by a Southern-dominated Supreme Court.

Even after the Civil War, convict leasing permitted states to loan those incarcerated to farms and businesses seeking cheap, fungible labor. Black codes and Jim Crow laws barred Black Americans the right to sit on a jury, and set harsh penalties for offenses like minor theft and vagrancy (essentially unemployment).

After the civil rights movement, many Southern states coded once explicitly racist policies into laws that drove mass incarceration, says Talitha LeFlouria, professor of African American studies and an expert on mass incarceration at the University of Virginia. Law and order politics and the war on drugs produced wide racial sentencing disparities, many of which persist today. For example, despite equal usage, Black Alabamians are four times more likely than white Alabamians to be arrested for marijuana possession.

“There shouldn’t be anything shameful about reflecting on our laws and saying, ‘OK, maybe they don’t reflect who we are now. They don’t reflect who we want to be,’” says Ms. Nelson of the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice. “But nonetheless, there’s a real resistance to that.”

The shadows of these historical prejudices still linger in courtrooms themselves, too.

Across the South, there are few Black judges and prosecutors, says Mr. Jackson, the first Black president of the Alabama District Attorneys Association. And Black citizens are frequently excluded from jury duty, according to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative.

“Some of these issues we dealt with in the 1950s and 1960s, we’re still grappling with them today,” adds Mr. Jackson.

Prison conditions and the hope of reform

Southern states incarcerate all racial groups at such high rates that the ratio for Black incarceration compared with other racial groups is actually lower than in some other regions. Yet because of those high incarceration numbers, the proportion of Black people in jail in the South is still higher than the national average.

Poverty plays a key role. Due to racial income gaps, excessive cash bail and the bevy of fines and fees imposed by Southern states make Black defendants more likely to spend time in jail.

Pretrial detention makes defendants more likely to plead guilty, regardless of guilt. It also leads to more time in prison and a higher recidivism rate, according to research from the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute.

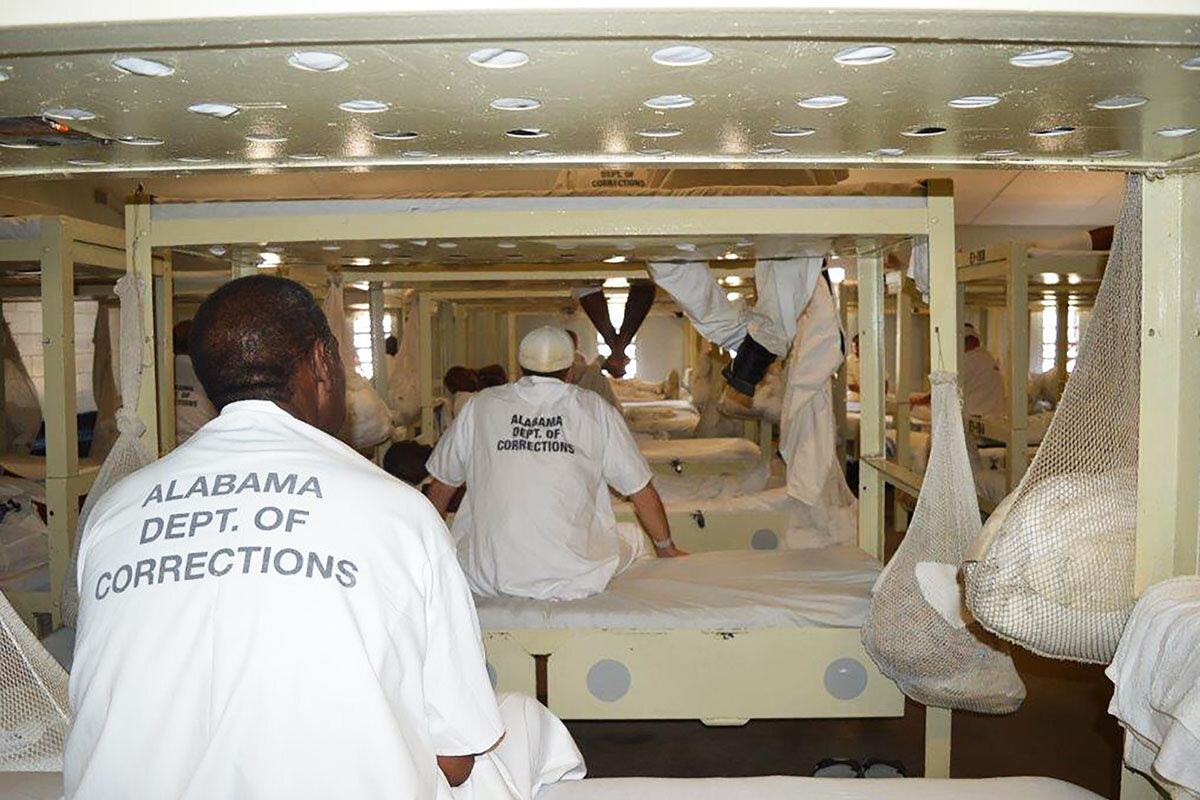

The conditions of many Southern detention facilities can make a stay in prison especially harmful. Last December, the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Alabama’s entire male prison system for violating Eighth Amendment rights, which include protection from cruel and unusual punishment.

Mr. Napier experienced these conditions firsthand. Fifteen years in state prisons included fights, weeks of solitary confinement, and long hours working on farms or performing menial labor for cents an hour.

“It’s the worst place to be while you’re still alive,” he says.

But criminal justice reform has recently become a more bipartisan issue, including in the South. In places, policymakers are seeking to reduce mass incarceration and strengthen the safety net for formerly incarcerated people.

- In 2016, Oklahoma reclassified some erstwhile felonies to misdemeanors. Three years later, the state parole board issued the largest single-day commutation in American history.

- Georgia has reduced its prison population in part by spending more on programs intended to reduce recidivism.

- South Carolina’s 2010 sentencing reforms lowered the state’s prison population and incarceration rate.

- This year, Virginia became the first Southern state to abolish the death penalty.

Yet attempts at reform often hit dead ends. In Savannah, Georgia, the district attorney recently asked for $280,000 to hire four new prosecutors. The goal was to speed up the cases of 63 inmates who have each been awaiting trial in jail for more than 1,000 days. One has spent 12 years in detention without a conviction. The county commission denied the request, suggesting a study.

Working for change

For those hoping for change, the wait can be long.

When Donchelle Jackson married her husband, Naserie Jackson, he was already in prison. He had been given a life sentence for accidentally killing a nearby boy when he pulled a gun on someone during a violent confrontation on his front lawn.

The couple had dated in high school but didn’t keep in contact until a friend told Ms. Jackson that Mr. Jackson was incarcerated. She wrote him a letter. He wrote back.

When they married, he had an “R” on his prison fatigues, indicating he was a restricted inmate and ineligible for work release or other programming. That letter has since been removed, and he’s in a halfway camp now, taking art classes and earning his commercial driver’s license.

Mr. Jackson is due for a parole hearing in the fall, and Ms. Jackson hopes he can come home to Mobile. She believes he’s changed. She hopes he has a chance to show the world.

In recent years, she’s become an advocate for criminal justice reform, completing a fellowship with Alabamians for Fair Justice in 2018. She feels like God called her to this work, she says, and that it won’t end if her husband is released.

“You do your part,” she tells him. “You keep that record clear.”

In two or three years, if she can’t make any progress toward getting him released, he’s told her, he’d understand if she needs to walk away.

“My response to him is if you’re giving me that kind of time, then I can walk away now,” Ms. Jackson says. “You don’t get to tell me [when to go]. I say you’re going to come home.”

The Sentencing Project, Death Penalty Information Center

A deeper look

The great outdoors has a diversity problem. Can it be fixed?

The country’s racial reckoning has shown that inequality often extends to nature: Some children grow up with access to wilderness, while others face barriers that keep them out. What’s being done to remedy that?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

-

By Jacob Baynham Correspondent

Public lands are perhaps America’s most democratic idea.

In theory.

But a closer look reveals America’s great outdoors – from rivers to mountains, national parks to community recreation centers – are marred by the same social and racial inequality present in other parts of American society.

“We’re a country built on the idea of having community parks, rec centers, state parks, county parks, national parks, and public lands,” says Lise Aangeenbrug, executive director of the Outdoor Industry Association. “They’re open to everyone. But just because it’s there, not everyone feels welcome. Not everyone has the resources to get there or to experience it in a fun or safe way.”

The causes are complex, and sometimes layered in decades or centuries of history, but the results are clear: Access to and use of America’s outdoors don’t reflect the diversity of the nation. But that doesn’t mean people aren’t trying to change that.

“We want kids, we want everybody to have those choices to find joy in the outdoors,” says Carolyn Finney, author of “Black Faces, White Spaces.”

And engaging new people now is a key to changing the outdoors tomorrow, Ms. Finney says: “Who we see, and what stories are told, that affects younger people.”

The great outdoors has a diversity problem. Can it be fixed?

Late one evening in October 2019, Don Baugh beached his kayak on the rocky shore of Pyne Poynt Park, a 15-acre postindustrial green space abutting a polluted backwater in Camden, New Jersey. Mr. Baugh runs an environmental nonprofit called Upstream Alliance, and he’d spent the day on the water pointing out sewage outflows to staff from New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection.

Now it was dusk, and Mr. Baugh wanted to load his boat and leave before dark. Across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, Camden is one of America’s poorest cities, and, until recently, one of its most murderous. This park in particular had a history of violent crime.

That’s why he was nervous when a boy of about 16 came zipping up the path on a dirt bike. The youth stopped near Mr. Baugh and watched him work.

“You’re a white guy,” said the boy, who was Latino. “White guys don’t come over to this side very much.”

The youth introduced himself as Angelo. He gestured to one of the kayaks. “How much is one of those things?”

Mr. Baugh looked at his kayak, a Current Designs touring model that retails for $3,000. Not wanting to deter the boy, he said: “Well, you can get a sit-on-top kayak for about $400. I’ll take you out sometime, if you want.”

“I’d like that,” Angelo said. “But $400 is too much.”

Mr. Baugh’s upper-middle-class childhood was a world apart from Angelo’s. Blessed with access and resources, Mr. Baugh spent his youth in nature, paddling his canoe up tributaries of Maryland’s Severn River. His mentors were environmentalists and engineers. He went to college, majored in conservation, and worked for 38 years at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Most days he commuted in a sea kayak – seven miles each way. For Mr. Baugh’s whole life, nature has mentally, physically, and financially enriched him.

Now in his 60s, Mr. Baugh lives aboard a 34-foot sailboat in a Philadelphia marina. He’s spending his life’s second act paddling the waterways around Angelo’s hometown, advocating for cleaner water with better public access, and designing free programs to get Camden’s children outside. He’s trying to break down economic, social, and environmental barriers to make people like Angelo feel as entitled to nature as he did.

“I didn’t worry about nature,” Mr. Baugh says. “Nature was inviting to me.”

That evening in the park, Mr. Baugh and Angelo were on the same side of the river. But they were also on two sides of a divide that threatens America’s public health and the future of its open spaces: Who finds belonging in nature, and who grows up estranged from it?

Last year, when the murder of George Floyd heightened awareness of the country’s racial inequities, protests erupted on the grounds of state capitols and in the commercial cores of America’s biggest cities.

At the same time, many Americans were seeking solace in the wilderness, which felt apart from both the pandemic and systemic racism. After all, wasn’t nature the one place where equality was guaranteed?

But generations of racism don’t end at a trailhead, just as they didn’t with the 13th Amendment. The country’s racial reckoning and the enduring pandemic have exposed an underlying truth in America’s outdoor community: that racial and social inequality extends into the wilderness because some children grow up with access to the outdoors, while others are shut out.

In theory, public lands are America’s most democratic idea. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, more than 726 million acres – a third of the nation – are protected from development for the benefit of all Americans. If that land were distributed equally, each American child would get more than 10 acres – roughly four city blocks.

But historically, America’s open spaces were founded by and for white people. Beginning with Yellowstone in 1872, many national parks were created by legislation with little regard to the historical territories of Native American tribes, or were negotiated from tribes via treaties that the U.S. government promptly breached. Until the middle of the last century, national parks still segregated people of color.

Today, childhood participation in outdoor recreation is declining, a disconnect most pronounced among marginalized communities and low-income families.

“We’re a country built on the idea of having community parks, rec centers, state parks, county parks, national parks, and public lands,” says Lise Aangeenbrug, executive director of the Outdoor Industry Association. “They’re open to everyone. But just because it’s there, not everyone feels welcome. Not everyone has the resources to get there or to experience it in a fun or safe way.”

To get exercise, stay healthy, or just escape the monotony of pandemic life, many Americans have recently taken up walking, biking, running, and hiking close to home, according to a report from the Outdoor Foundation. These new outdoor participants are slightly more diverse than pre-pandemic numbers, but they are still 66% white. And it’s unclear if these habits will stick.

What is clear is that the overall pool of people who recreate outdoors in America is small. According to a 2020 Outdoor Foundation report, half of Americans aren’t active outside even once a year. The people who are getting outside look a lot like they always have: mostly white, mostly male, and mostly living in households with above-average incomes.

“When you live in Boulder or Bozeman, everybody gets outside,” says Ms. Aangeenbrug. “That’s not true in the rest of the U.S. It’s not the norm anymore.”

Recent research has discovered myriad health benefits of time outside. A 2019 study from Denmark shows that simply growing up near green space accounts for a 55% lower risk of developing mental health disorders in adulthood.

Children especially benefit from nature. Studies show that time outside improves their grades, friendships, and behavior. Getting more kids outside more often could dramatically improve their health over a lifetime, because adults are twice as likely to get outside if they did so as children.

“Time outdoors peaks when you’re a child,” Ms. Aangeenbrug says. “It may have a resurgence in your 30s, but it drops off after 45. If we start with a lower number for children, eventually we won’t see the numbers of adults that come outside.”

Among lower-income and marginalized children, the barriers to getting outside are multiple and intersectional. They include the logistics of transportation, a lack of exposure to outdoor recreation and mentors to teach them, the perceived and real dangers of nature, and not seeing themselves reflected in outdoor media.

But among youth polled by the Outdoor Foundation in 2018, their main reason for not getting outside was the cost of outdoor recreation equipment.

Journeying into the woods didn’t use to be expensive. Half a century ago, people climbed mountains in tennis shoes, skied in jeans, and went backpacking with clunky aluminum-framed packs. They made do.

In the last few decades, however, outdoor recreation has grown into an $887 billion industry in which companies develop new products each year that help people get outside safer, faster, lighter, and with more comfort than ever before.

Much of this gear is pricey, of course, and it’s no accident that the most numerous and active participants in sports like skiing, mountain biking, rock climbing, and fly fishing are wealthier than the general population. Nor is it an accident that outdoor companies target their marketing toward this deep-pocketed demographic.

Take climbing, for example. Climbers spend $1,200 more on gear and apparel per year than the average outdoor consumer. According to a 2019 American Alpine Club report, more than 82% of climbers are white. The majority are men, and most fall within the $50,000 to $100,000 income range.

Outdoor Foundation research found that the same is true of most outdoor sports, except skateboarding and running, whose participants closely mirror the demographics of the country.

Skiing is perhaps the whitest and wealthiest outdoor sport of all. According to the National Ski Areas Association, 87% of ski resort visitors are white, and 59% are male. A majority of visitors have household incomes greater than $100,000. For a low-

income child of color scrolling Instagram, the conclusion is unavoidable: Outdoor sports are for rich white folks.

The industry is taking notice. In 2019, Vail Resorts Chief Executive Officer Rob Katz and his wife, Elana Amsterdam, announced they were donating $10 million to nonprofits helping get underserved children on the slopes. That altruism may be self-serving, too. By 2045, white people will be a minority in the U.S., so if people of color don’t take up skiing in larger numbers, the future of the industry is at risk.

“From the business side, there’s an opportunity to create the next generation of skiers and riders,” says Constance Beverley, CEO of the Share Winter Foundation. “But the industry has to stop thinking about their core customer as a kid from a dual-parent family where one isn’t working, with a lot of money to enroll them in ski school.”

The Share Winter Foundation offers around $1 million each year to get 45,000 youth on snow in 21 states – particularly kids who have lacked access to snow sports. Last winter these programs operated at 45% capacity, as the pandemic upended the ski industry. Many resorts were hampered by reduced public transportation, too, making it harder than ever for a disadvantaged youth to get on snow.

“COVID has shown a great divide in everything from access to health care to access to the mountains,” Ms. Beverley says. “The cost of skiing goes up.”

Even outside a pandemic, however, the cost of outdoor sports cannot fully explain the nature disparity in America. Millions of American children come from families who can afford a park pass, a beginner backpacking setup, or a pair of skis. So why do well-off white young men disproportionately benefit from America’s open spaces?

For that we can blame culture. And to understand how that culture affects children in nature differently, Carolyn Finney, author of “Black Faces, White Spaces,” suggests we start with history.

“This whole country was once a big, wide-open space,” Ms. Finney says. “There was all this land, and American Indians lived here and had a very particular relationship with the outdoors. Then people of European descent came over and started settling with their set of ideas. They killed and got rid of the people who lived here and enslaved a bunch of other people to work that land. Then they segregated things, even the outdoors. We’re still coming out of that.”

America’s relationship with the outdoors has been formed by the dominant white majority who valued nature first for its extractable resources and, second, for its recreation potential. Even the idea of “public lands” was a foreign concept before Europeans arrived with notions of what could be owned and by whom. Those ideas still shape America’s outdoor culture today.

“The question is, what gets normalized?” Ms. Finney says. “What do you have to look like? What do you have to wear? How much of your own self do you have to give up in order to be accepted into a space?”

Ms. Finney rejects the idea that people of color just aren’t interested in the outdoors. According to the Outdoor Foundation’s 2020 report, Asian Americans had the highest outdoor participation rates within ethnic groups, and Hispanics went on the most annual outings. The Natural Resources Defense Council has identified African Americans as a major environmental voting bloc.

And yet there’s a severe lack of representation of people of color in outdoor media. While writing her book, Ms. Finney reviewed 10 years of Outside magazine and found that just 2% of the photographs featured African Americans.

“I never saw myself in media,” Ms. Finney says. “Who we see, and what stories are told, that affects younger people.”

Family affects people’s relationship with nature, too. Ms. Finney grew up in New York, where she was a Girl Scout. She went to the meetings for two full years before her father let her attend the camping weekend. Her father, a Korean War veteran who tried to become a park ranger but couldn’t because of his color, was afraid to send his Black daughter into the woods with a bunch of white people.

That fear has roots. For generations, nature was a perilous place for African Americans, where racism could unfurl to its most ghastly extremes. In the wilderness, trees were used for lynchings, and dogs tracked people escaping slavery. Immigrant children who crossed the U.S. border from Mexico may have their own reasons to associate the outdoors with trauma. These narratives, either lived or inherited, help explain why more than half of nonwhite Americans consider the outdoors unsafe.

To counter this, advocacy groups have sprung up from within the communities facing the most barriers to getting outside. Ms. Finney credits the grassroots, nationwide work that Outdoor Afro has done to encourage Black people to enjoy nature. NativesOutdoors, Latino Outdoors, and GirlTrek are other groups started by and working for communities of color.

“We want kids, we want everybody to have those choices to find joy in the outdoors,” Ms. Finney says.

José González, the founder of Latino Outdoors, still remembers the first time he felt different than other youth in nature. Mr. González grew up in rural Mexico, where “the outdoors” was just “outside,” and a “hike” was a walk to his grandparents’ house. He was always in nature.

Then his family moved to suburban California, where getting into the wild required a car. In high school, his family drove up to see snow in the Sierra Nevada. He didn’t have any snow gear, so he stuffed his feet into plastic bags inside his shoes.

“It was freezing,” Mr. González recalls, “and slightly embarrassing. It didn’t stop us from having fun, but it made me aware of how we were enjoying it differently. The other kids had snow pants and snow boots. I thought, did they buy those things just for today?”

It was the first time Mr. González realized that there was a culture to America’s outdoors, an unwritten rulebook for what you should wear and how you should act. Implicitly, some things were permitted, and others were not.

Mr. González became an environmentalist and community organizer. In 2013, he started Latino Outdoors, a nationwide community that celebrates and cultivates Latinos’ relationships with nature. Mr. González now serves as founder emeritus for the group, and in his work as a consultant, educator, and artist, he envisions a future in which there is no need to advocate for outdoor diversity, because everyone can find equal access and belonging in America’s open spaces.

To achieve that will require broadening ideas of what is accepted in nature. Some people go into the outdoors to find silence and solitude, while others want a social cookout with music and laughter. It’s especially important to keep an open mind about how young people interact with the outdoors.

“If we’re not careful,” Mr. González says, “we frame nature as a fine arts museum: Don’t touch anything! Stay on the trail! Get off that tree! We’re not showing them how to engage with nature in a way that’s healthy and educational, but also builds their ethics and responsibility.”

Sometimes, inclusion even means reconsidering the sacrosanct. The practice of “leave no trace,” for example, is gospel in the outdoor community to minimize impacts on the wilderness. But how does it alienate a Native American child who leaves food in the forest as an offering to an ancestor? How does it create a codified culture that unintentionally excludes people of color?

Mr. González also thinks we should work to undo the perception that experiences in nature are hierarchical – that multiday backpacking trips are the most valuable, and a trip to the local park is the least. Smaller, shorter excursions require less gear, planning, and transportation, and are therefore accessible to more people.

“Who told us that is a better experience?” he says. “A one-mile walk or hike can be just as enriching, even more so, than a seven-

mile trek.”

Introducing underprivileged youth to a wide spectrum of experiences is the work of many national nonprofits. In Denver, cityWILD is a 23-year-old program that has exposed thousands of urban kids to outdoor adventure. Colorado is rich with such programs, thanks to Great Outdoors Colorado, whose Generation Wild campaign is funded by proceeds from the state lottery. New Mexico, for its part, recently created a first-of-its-kind Outdoor Equity Fund to make outdoor recreation more available to all children.

In 2019, the Outdoor Foundation launched its Thrive Outside initiative to provide children with consistent, positive experiences in nature. The initiative has funded gear libraries in Michigan, taught paddle sports in Oklahoma City, and sponsored surfing clinics in San Diego.

Since 2011, the National Park Foundation’s Open OutDoors for Kids program has brought more than 1 million children to a national park, most of them for the first time. They aim to connect another 1 million youth to parks in the next four years.

A 2018 report from the George Wright Forum found that Asian Americans and Hispanics each account for just 5% of visitors to national parks, and just 2% of visitors are African American.

“There are so many barriers,” says LaTresse Snead, chief program officer for the National Park Foundation. “Most national parks don’t have public transportation. Even if you do have a car, there’s the cost of gas and the entrance fee. More than that, it’s also about personal relevancy, and people actually seeing the park as a space for them.”

By exposing kids to parks at a young age, and continuing to engage them in service corps, internships, and apprenticeships through college, Ms. Snead hopes the National Park Foundation can foster a diverse new generation of nature lovers, public land stewards, and park superintendents.

Connecting youth of color with careers in conservation is one of the primary ambitions of Angelou Ezeilo, founder and CEO of the Greening Youth Foundation (GYF) in Atlanta. “Our vision,” Ms. Ezeilo says, “is that the environmental sector reflects the demographics of the society that we live in.” Her 2019 book, “Engage, Connect, Protect: Empowering Diverse Youth as Environmental Leaders,” critiques the lack of diversity in the environmental movement and offers a blueprint to change it.

One of the foundation’s initiatives is a public-private partnership called The Bridge Project. It aims to create a hiring pathway to match qualified, diverse candidates with employers in conservation, natural resource management, and outdoor recreation.

Ms. Ezeilo grew up in concrete-bound Jersey City, New Jersey, but fell in love with the outdoors on family trips to upstate New York. In 2005, she left a law career and founded GYF “to debunk the myth that only wealthy white people should be recreating in the great outdoors.”

Ms. Ezeilo urges anyone who cares about diversity in nature to volunteer for or financially support environmental organizations, especially those led by people of color. “People have been complicit in this space for so long, particularly white people,” she says. “They see it happening, but they don’t step up and do anything about it. I would encourage people to step out. Be bold, even if it means you’ll be a little uncomfortable.”

In Pictures

Drive-ins, dusk, and dashboards

As moviegoers flocked to drive-in theaters in search of a pandemic distraction, they found something more – nostalgia and a reminder of just how good it feels to do something together, even when you’re in separate cars.

Drive-ins, dusk, and dashboards

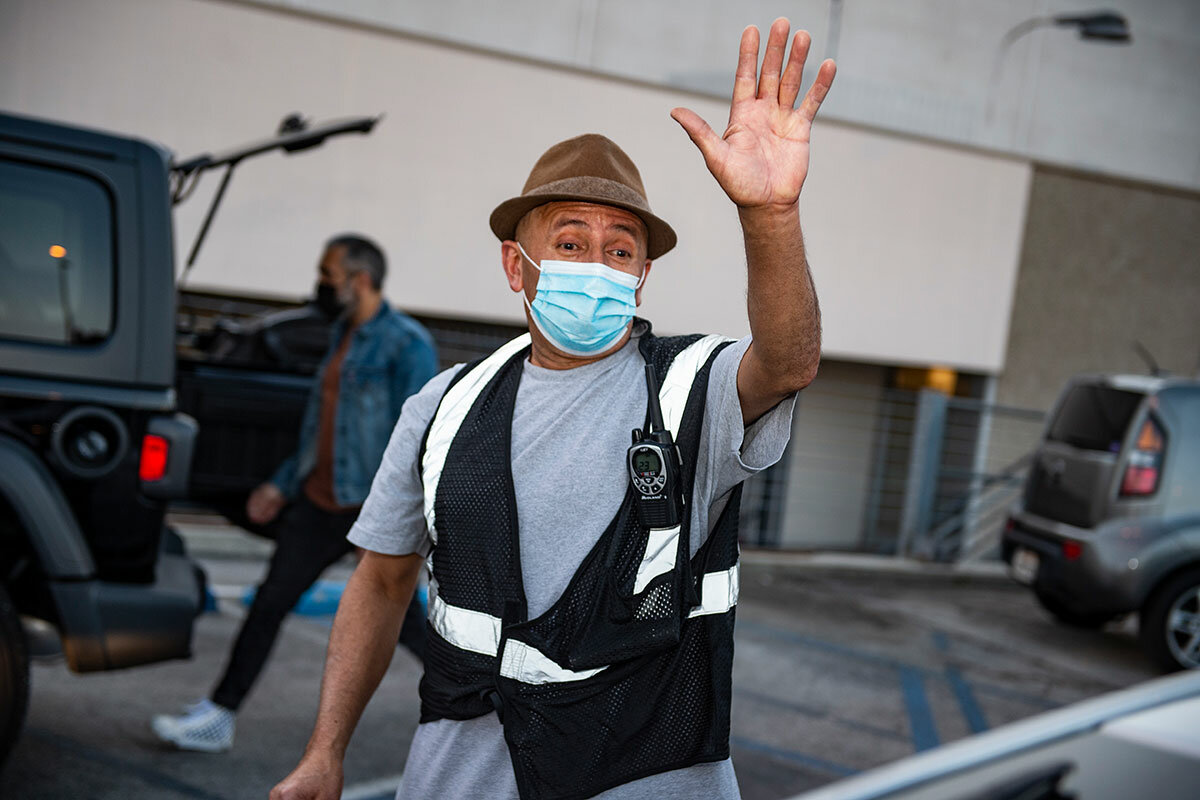

The Glendale parking lot is filling up quickly as Xavier Sanchez carefully directs another car into just the right spot.

It’s not the weekend, or even a new blockbuster release, but the cars keep lining up to see the pop-up double feature at the Electric Dusk Drive-In. Even as indoor theaters slowly begin to reopen, Los Angeles moviegoers still seem to be flocking to the reemerging drive-in movie scene. Is it just nostalgia or a trend that’s here to stay?

With its year-round temperate weather and deeply embedded car culture, a city like Los Angeles seems to be the perfect place for drive-in theaters. Before the pandemic, a slow and steady decline had settled in, leaving only a handful of viable theaters scattered around the area. Mission Tiki Drive-In Theatre in Montclair, which opened in 1956, had seen a decline in ticket sales and the site was sold.

The pandemic ended up being a bittersweet reprieve for Mission Tiki. As the developer delayed breaking ground, the drive-in saw an increase in ticket sales as moviegoers rediscovered the retro entertainment. The temporary reopening also gave local fans more time to say goodbye.

With so few established drive-in theaters left, pop-ups have swept in. Using inflatable screens and rented parking lots, new companies are offering blockbuster releases and old films to audiences.

“We were locked in quarantine in 2020. I sat there and scratched my head. It’s like, what a great opportunity to make lemonade out of lemons,” says P. Ben Chou, founder of WE Drive-Ins, who used his new company to address the need for pandemic-safe entertainment in his community.

Mr. Chou decided that he could help not only cooped-up movie fans (by “restoring the hearts”) but also workers hit hardest by the pandemic (in the restaurant and theater sectors). Before going on hiatus recently, his pop-ups included food and films, so that he was “putting both sectors, to a small degree, back to work,” Mr. Chou says.

Despite the struggles of the older, established drive-ins, pop-up models that repurpose underused spaces seem to be thriving for now, even as indoor entertainment becomes more widely available.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Park it! Why the world is a bit greener.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A long list of environmental issues needs serious attention. But none may be more fundamental than preserving land and water to maintain biodiversity and help slow climate change. A recent report shows just how well humanity is doing on one of those goals. In the last decade, some 8.1 million square miles have been added as parks or conservation areas. That’s an area larger than Russia, a country that spans 11 time zones.

As of 2020, some 17% of the world’s landmass is protected from development. That meets a goal set in 2010 at the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in Japan. This October, new goals for protecting additional land will be negotiated at the U.N. Biodiversity Conference in Kunming, China.

After centuries of rapid human expansion on the planet, humanity may have turned a corner and decided to balance human development and the land that sustains it. A healthy resiliency for both depends on that task. The recent success in land conservation is a model for what can still be done.

Park it! Why the world is a bit greener.

A long list of environmental issues needs serious attention. But none may be more fundamental than preserving land and water to maintain biodiversity and help slow climate change. A recent report shows just how well humanity is doing on one of those goals. In the last decade, some 8.1 million square miles have been added as parks or conservation areas.

That’s an area larger than Russia, a country that spans 11 time zones.

To give that success a different perspective, of all the land ever protected and conserved by official action, 42% was in the past decade. That pace of problem-solving sets a good example of what can be done with other global challenges.

As of 2020, some 17% of the world’s landmass is protected from development. That meets a goal set in 2010 at the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in Japan. The convention also sought to protect 10% of the world’s oceans by 2020. That mark was missed; nonetheless, 7.74% of coastal and ocean waters are now protected, according to the 2020 Protected Planet Report.

This October, new goals for protecting additional land and water will be negotiated at the U.N. Biodiversity Conference in Kunming, China. Dr. Bruno Oberle, director general of the International Union for Conservation of Nature in Gland, Switzerland, is urging the conference to set a goal of protecting 30% of the world’s land, fresh water, and oceans by 2030. “And these areas must be placed optimally to protect the diversity of life on Earth and be effectively managed and equitably governed,” he adds. Britain already has committed to protecting 30% of its land by 2030 with new parks and protection of “areas of outstanding natural beauty.”

Land protection comes with its own challenges. The areas must be properly supervised. And local people living near them must not bear all the costs of protecting them when the benefits will be widely shared. Protected regions also will be more effective if they can be connected to other protected regions, allowing wildlife to migrate between them.

After centuries of rapid human expansion on the planet, humanity may have turned a corner and decided to balance human development and the land that sustains it. A healthy resiliency for both depends on that task. The recent success in land conservation is a model for what can still be done.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The life we’re meant to live

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Nancy Humphrey Case

Who doesn’t long for freedom from whatever may be constricting us? Realizing that we’re created to reflect God’s spiritual, flawless nature empowers us to more freely experience healing and harmony in our lives.

The life we’re meant to live

We lived near the end of a dead-end road, and I loved leading my horse into the woods on a trail that looped back toward our land. When we emerged from the woods into a neighbor’s big field, I’d take off his halter and send him galloping the half-mile back to his herd, his mane flying in the wind. I could only imagine how good it felt to him to run free like that – something horses were made to do.

Who doesn’t long for freedom, whether from an oppressive government, limiting fears, unhealthy relationships, debilitating mental or physical conditions, or grief? We may long not only to find freedom ourselves but also to help others break free from these and other problems.

How to do it is the million-dollar question. Reasoning based on input from the physical senses will always run up against a fence eventually, being limited in its very nature. King David in the Bible hinted at an answer when he prayed, “Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation; and uphold me with thy free spirit” (Psalms 51:12). And St. Paul found transformative freedom after learning to know himself spiritually through Christ. He said, “The law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus hath made me free from the law of sin and death” (Romans 8:2).

Doesn’t this imply that freedom from mortality itself is a law of Spirit, God? Christian Science explains how to experience this law of Spirit in our lives by understanding God as infinite Spirit, infinite good, and ourselves as expressing God’s nature – as spiritual and whole, not material and flawed.

I experienced something of this a few years ago when I was greatly in need of healing. I had taken a bad fall from my horse, and there was such pain in my back and rib cage that for a week I spent my nights sleeping in a chair. Yet I was very hopeful, even expectant, of healing because of all the previous healings I’d had and witnessed through Christian Science, and because I knew this painful condition was not authorized by God, divine Love.

I prayed every day to understand better what it means to be the spiritual image of God (see Genesis 1:26, 27). Not just to accept or declare it, but to really understand it deep down. I knew I was on the right track because I was gaining fresh insights into the truth that Christ Jesus promised would make us free if we followed his teachings (see John 8:31, 32). I did receive some relief, which was encouraging, but the pain worsened one day when I threw a Frisbee for our dog.

Then one morning I came across a talk by a member of the Christian Science Board of Lectureship posted on YouTube. The speaker talked about exchanging a mortal concept of who we are for our true, spiritual identity as the eternal likeness of God. Drawing on related texts from the Bible, he made it clear that troubles stem from holding on to or feeling bound by false, matter-based concepts of identity instead of recognizing our God-given, spiritual nature and heritage. As Spirit’s loved offspring, we possess all of God’s qualities and nothing else.

I drank in the message of that lecture, and by the end of it I felt as though I had awakened from a dream. What the physical senses said about the state of my being was no longer legitimate to me. I walked into the kitchen feeling so free! It was as if a sunburst of spiritual light had changed my whole perspective. I knew that fundamentally I was the spiritual child of God, free from mortality with all its discords and limitations.

With that, the pain in my rib cage completely left. It wasn’t long before the remaining discomfort in my back was gone as well.

In the textbook of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy writes: “The admission to one’s self that man is God’s own likeness sets man free to master the infinite idea” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 90). Whether this admission or recognition comes as a flash of inspiration, the result of perseverance in prayer, or some combination of both, we can be assured that the truth will indeed make us free.

Because each one of us is made to glorify God, infinite Spirit, it is so natural for us to live a life of holy freedom and joy.

Interested in hearing a public talk by a member of the international Christian Science Board of Lectureship that explores how the laws of God, good, can liberate us? Check out these online talks or find an in-person talk near you.

A message of love

Support for Surfside

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Come back tomorrow to meet people who’ve made a strong connection between their spirituality and the natural world, and who see stewardship of the environment as part of their religious mission.