- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

An off-court milestone for LeBron James

Even when he’s not playing in the NBA finals, superstar LeBron James draws attention. And next month, his new movie – “Space Jam: A New Legacy” – comes out.

Less noticed is another milestone: 10 years ago the LeBron James Family Foundation offered free laptops and bicycles to more than 300 third graders in Akron, Ohio, the beginning of a commitment that has blossomed into the “I Promise” program for kids with low reading scores. This month, 169 of the original 327 students graduated from high school, and a third of the graduates, according to the Akron Beacon Journal, are headed to college.

OK. Local hero gives back to hometown is not a new idea. Are there deeper lessons here? One is that resources matter. The “I Promise” program and its partners are helping families with everything from food to housing for homeless students and education for parents. Partners Kent State University and the University of Akron are offering four years of free tuition to graduates of the program.

Another lesson is that resources aren’t enough. Students and parents (and Mr. James) make promises to each other and renew them daily. While parents pledge to be good role models and hold their children accountable, students promise to listen to their teachers, eat right and be active, and dream big. The program’s mottos? “We are family” and “Everything is earned, nothing is given.”

Jamil Wright, an “I Promise” student, used to write cards to Mr. James, like “Merry Christmas” or “Congratulations on a good game.” According to the Beacon Journal, he once asked the superstar if he got his cards or read them. Mr. James responded by quoting a recent one.

Call it respect, commitment, or love. That, too, is making a difference in Akron.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Biden wants infrastructure. Does America know how to do it anymore?

How the U.S. rebuilds its roadways, airports, and rails is a major topic in Washington. A tale from a Boston suburb shows why America has fallen behind other nations – and what it needs to fix.

In days gone by, America’s highways, bridges, tunnels, and dams were the envy of the industrialized world. Today, as President Joe Biden and lawmakers in Congress wrangle over a proposed $1.2 trillion bipartisan deal on infrastructure spending, tables have turned. The United States is better known for its maintenance backlog and for costs that far outstrip what other nations pay for projects that do roll forward.

Why? Consider the story of one rail-line expansion outside Boston. First proposed in the 1980s, this 5-mile stretch of above-ground track is set for a partial opening in December. Cost: more than $2 billion.

The challenges in Massachusetts mirror ones seen nationwide, from management shortcomings to stop-start funding and the risk of lawsuits. The project almost got canceled in 2015 as cost projections soared.

“We threw all the consultants out and started with a whole new team,” says Joseph Aiello, a former transportation official tapped to chair an independent review board.

To make the Boston-area project work, the new Union Square station in Somerville will be a bare-bones open-air stop with no plazas or elevators.

“This is what we were left with,” says William White, a city councilor and civil attorney. But “we’re getting the Green Line.”

Biden wants infrastructure. Does America know how to do it anymore?

From the bridge over the railroad, William White can trace the contours of the crowded city streets where he grew up, not far from the slaughterhouses and factories that abutted the tracks below. Those industries are long gone, and his working-class neighborhood is now a magnet for gourmet-doughnut browsing millennials.

More may be coming.

Below the bridge is a newly built station – construction still underway on the edges – that will link Somerville to Boston’s transit system, part of a long-promised extension. Private developers have already broken ground on an adjacent 25-story tower block aimed at biotech companies that cluster in nearby Cambridge. Dump trucks circle a dusty strip.

To Mr. White, a city councilor and civil attorney, the marvel is that the transit project is actually coming to fruition. He recalls how the troubled transit project was nearly scrapped in 2015 after massive cost overruns. To get it over the line, Somerville had to commit $50 million of its own money. Now service to this station on a spur line is due to start in December. “It all worked out. We’re getting the Green Line,” he says.

As President Joe Biden pushes for Congress to pass a new $1.2 trillion bipartisan deal on infrastructure spending, the odyssey of this project just outside Boston may serve as a cautionary example. Mr. Biden’s massive proposal addresses acknowledged needs that include railroads, highways, bridges, tunnels, and dams as well as mass transit. These American civic structures were once the envy of the industrialized world. Today the United States is better known for its dilapidated airports and crumbling bridges, and for political impasses in Washington over how to repair and update them.

A nationwide challenge

At a cost of $2.3 billion, the Green Line extension is more than twice as expensive as similar projects in Europe and Asia. And it’s not just Boston: Subway and light-rail projects in other U.S. cities also cost significantly more per mile. A 2015 review of projects planned or built in 44 countries found that four of the most expensive were in the U.S., led by New York City.

From Madrid and Paris to Istanbul and Seoul, politicians and engineers have figured out how to build subways and light rail faster and cheaper, giving their cities a competitive advantage in mobility and cutting auto emissions.

“We need to see a better return on investment,” says Eric Goldwyn, an assistant professor at New York University who studies transit construction costs.

Inflation also stalks U.S. highways, says Leah Brooks, an economist at George Washington University who studies urban economies. She found that the cost of interstate highways tripled between the 1960s and 1980s, a rise that wasn’t explained by higher labor or materials costs. Simply put, the U.S. gets less bang for its buck when it builds roads and bridges.

“Because it’s so expensive, we get so much less of them and we serve fewer people,” she says. “You’re spending $10 billion on a project that could have cost $5 billion.”

Analysts say inflated U.S. prices stem from multiple factors, including political interference and patronage and the stop-start funding of projects. Public agencies hollowed out by budget cuts fail to oversee contractors and end up with expensive errors. “Buy America” provisions complicate procurement. Lawsuits and reviews lead to delays, add-ons, and cost overruns.

First proposed in the 1980s, Boston’s 4.7-mile Green Line extension, known as GLX, endured many of these problems. It will also open at a time of pandemic-induced low ridership on U.S. transit systems, though Mr. White and other supporters voice confidence that riders will return.

Like other cities, Boston has other transportation projects that also depend on federal funding. Mr. Biden’s bipartisan plan would invest $49 billion in public transit and $66 billion in passenger rail. Whether that money is spent effectively is another matter, says Fred Salvucci, an engineer and former Massachusetts secretary of transportation. He urges local leaders to learn from how other countries build.

“My hope is that with the incentive of all this federal money, at least some states will say, ‘Let’s make the best use of it and use the best techniques we can,’” he says.

Boston has the country’s oldest subway line (1897). And it shows: An unwieldy network of trolleys and subways run by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) has long struggled to keep pace with demand, even as rush-hour congestion snarls its narrow streets. Locals joke about whether to walk or take their time by taking the “T.”

Odyssey of an upgrade

The promise of extending service to new areas in Somerville and neighboring Medford originated in downtown Boston’s highway-and-tunnel boom of the 1990s, known as the Big Dig. It was the most expensive metro area highway project ever built. To offset the increase in car traffic and pollution, Massachusetts agreed to build the Green Line extension and other mass transit lines.

But the MBTA’s budget was later slashed as political support for transit projects fizzled, says Professor Salvucci, an engineer who helped plan the Big Dig. He notes that his boss, former Gov. Michael Dukakis, would ride the T to work and call him to report any delays.

“You need a chief executive who cares about this stuff and cares about getting it done well,” says Professor Salvucci, who now teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

It took a series of environmental lawsuits to force Massachusetts to finally start work on the GLX. In 2014, Gov. Deval Patrick, a Democrat, secured a $996 million federal grant to extend the line, with the promise of the first stations to be operational within three years.

But the project’s costs had begun to balloon so much that it quickly unraveled.

Scaling back amenities?

Take Union Square, the neighborhood in Somerville where Mr. White grew up. Its station design was a two-level 15,000-square-foot structure with two elevators, bathrooms, ticket machines, and bicycle storage, with connecting ramps and outdoor seating. Price tag: $40 million.

For the community, it was a no-brainer, a T station as public amenity, says Professor Goldwyn. But a fancy station means less money for building tracks, so lines may end up serving fewer people. This is one reason, he notes, that New York’s Second Avenue subway that opened in 2017 at a cost of $4.5 billion – the world’s most expensive per mile – only has three stations.

“It’s perfectly acceptable to say this is a transit project – and a community building project,” Professor Goldwyn says of the GLX. But residents have to understand the trade-offs that come with station plazas and bike paths and other amenities. “That discussion needs to be had.”

Cracking down on cost overruns

In 2015, newly elected Gov. Charlie Baker ordered a top-to-bottom review of GLX after the MBTA put the final cost at $3 billion, not the $2 billion it had forecast. Governor Baker, a Republican, said the project was a non-starter at that price.

Expensive stations were symptomatic of a deeper cost problem, says Joseph Aiello, a former transportation official whom Governor Baker tapped to chair an independent review board. To Mr. Aiello, who had worked on private funding of public infrastructure, the budget blowout was a major management failure. “Someone wasn’t minding the shop,” he says.

By then, the MBTA had already spent nearly $700 million of public money on GLX, mostly on consultants. Due to cuts and retirement, the agency only had a handful of managers to oversee the project and used a complex bidding formula that favored contractors with an inside track.

“We threw all the consultants out and started with a whole new team,” says Mr. Aiello.

As a result, Union Square station is now a bare-bones open-air stop with no plazas or elevators. “This is what we were left with, so clearly we’re not going to say no,” says Mr. White, the city councilor.

Even after its redesign, the project wasn’t hitting its $2.3 billion budget, so Somerville was asked to pay into a contingency fund. Some residents objected to being “shaken down” for a state-led project, says Mr. White. But he saw the risk of cancellation as a death knell for commercial redevelopment and backed the mayor’s request for a $50 million bond issue. (Cambridge, where the line currently ends, put in $25 million.)

At the time, Governor Baker was prepared to kill GLX, says Professor Salvucci. “The only reason the Green Line finally got moving is that the mayor of Somerville wouldn’t give up.”

John Dalton, GLX’s project manager, who joined the MBTA in 2016, says support from the community has been essential during the main construction phase. In Somerville, the most densely populated city in New England, road bridges had to be rebuilt along commuter-rail lines where new tracks are being laid in parallel.

“We’ve closed major roads. We’ve been working around the clock. And we’ve been in people’s backyards, literally,” says Mr. Dalton.

Way behind global peers

While the GLX is an extreme case of budget overruns and delayed delivery, it is typical of how most U.S. transit is built, says Professor Goldwyn. The Green Line’s per-mile costs are only slightly less than Boston’s Red Line extension that ended in 1985 and was entirely underground. (Street-level rail is far cheaper than tunneling.)

Professor Goldwyn’s research team is studying GLX and similar projects in the U.S. and Europe to understand how American cities could build more cheaply, for example by rethinking project design and management. “We want to see a better return on investment,” he says.

Professor Salvucci says greater federal oversight of transportation projects might help contain costs and promote best practices, though he cautions that lawmakers will resist such strictures.

International transit cost comparisons are complicated by variations in design, scope, and terrain. But researchers find that most fall within a range and that U.S. transit costs are much higher.

And what seems indisputable is how much longer it takes to build U.S. transit. In the late 1990s, Madrid built and opened 35 miles of metro lines, mostly underground. More recently, Istanbul tunneled a 12-mile line with 16 stations between 2011 and 2018. Over a similar period, Seattle built a downtown light-rail tunnel with two stations. Its length? Just over 3 miles.

The costs of litigiousness

One common obstacle for U.S. rail and highway builders is litigation, or the threat of it, particularly when landowners or politicians decide to stop or divert a project. Professor Brooks says “citizen voice,” whether grassroots organizing or an affluent sense of “not in my backyard,” took off in the 1970s. That is also when road construction costs began soaring. While other countries also have robust environmental and social review processes, a final go-ahead for a project is conclusive.

Mr. Dalton, who has managed transit projects in Chicago and Dubai, says the U.S. legal and political context shapes how project costs are evaluated. “I think contractors here make a lot of assumptions about risk in terms of sort of community pressure and public pressure and political pressure that they know they are going to be subject to,” he says.

Still, providing avenues for judicial review is important, particularly given the history of U.S. highway building through minority communities, says Professor Brooks. And in the case of GLX, lawsuits kept the project alive by forcing Massachusetts to keep its commitment.

One proposal is to put a time limit on the environmental review of large projects. A bipartisan Senate road-funding bill released in May would impose a two-year limit on such reviews. This spending would be part of the president’s $1.2 trillion infrastructure plan.

Professor Brooks says Congress should also insist on transparency for federally funded transportation projects so the public can see where its money is spent. The Federal Highway Administration knows how much it provides to states. “But they can’t tie that money to specific projects so they literally cannot calculate” the cost per mile, she says. “That suggests a lack of political will.”

Back in Somerville, service on the main branch of GLX is due to start next May. And although the costs have gone up over the course of the project, Mr. Dalton says he’s confident that GLX will come in under the current budget – despite pandemic disruption and higher materials costs. The MBTA has told Somerville that it will get its $50 million back in full.

The Explainer

South China Sea: A new US president confronts an old challenge

The Biden administration has high ambitions for building back relationships with Asian countries. Meeting that renewed goal may require tackling a not-new problem: the South China Sea.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

China is high on President Joe Biden’s list of priorities. The new administration has emphasized its desire to strengthen relations with Asia – in part, to counter top rival Beijing.

And one place that priority will be tested is the South China Sea, a vast body of water thought to contain huge oil and gas reserves. Beijing claims almost the entire sea, and has expanded its military presence there by transforming tiny islands and reefs into airstrips. Territorial disputes have long simmered between Brunei, China, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. And tensions have been dialing up since March, when Chinese vessels entered waters near Philippine islands.

In his first speech to Congress, President Biden said he had told Chinese leader Xi Jinping that the United States intends to maintain a strong military presence in the Indo-Pacific, “not to start conflict but to prevent one.” The line between those two can be thin in this always tense region, though. And with China-U.S. relations at their chilliest in decades, the South China Sea symbolizes a wider competition for influence between the world’s top two economies.

South China Sea: A new US president confronts an old challenge

Since coming into office, the Biden administration has made one of its top priorities strengthening relations with Asia – in part, to counter top rival China.

That priority will be tested in the South China Sea, where territorial disputes have long simmered between Brunei, China, Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Beijing claims almost the entire body of water, which stretches across more than 1 million square miles, and has expanded its military presence by transforming tiny islands and reefs into airstrips. Tensions have been dialing up since March, when more than 200 Chinese vessels entered waters near Philippine islands.

In his first speech to Congress, President Joe Biden said he had told Chinese leader Xi Jinping that the United States intends to maintain a strong military presence in the Indo-Pacific, “not to start conflict but to prevent one.” The line between those two can be thin in this always-tense region, though. And with China-U.S. relations at their chilliest in decades, the South China Sea symbolizes a wider competition for influence between the world’s top two economies.

Why is control of the sea so contested?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea formalizes countries’ rights and responsibilities on the world’s oceans. The convention established the idea of exclusive economic zones: the area stretching 200 nautical miles from a state’s coastline, where it has special rights to exploit resources. Where countries’ EEZs overlap, UNCLOS says they must negotiate.

“UNCLOS was supposed to stop conflict by creating clarity over who had the right to exploit resources in those EEZs,” says Ann Marie Murphy, a professor at Seton Hall University who is an expert on security in Southeast Asia. Instead, “countries began to extend their baselines, argue over continental shelves, realize they have overlapping EEZs ... these disputes go back decades.”

But China claims everything within the “nine-dash line,” stretching from Taiwan to Malaysia – a vaguely defined boundary purportedly based on old maps, according to James Chin, director of the Asia Institute Tasmania at the University of Tasmania.

In 2016, an international tribunal at The Hague ruled there was no legal basis for such a claim. China rejected the decision, and other countries have continued to complain about Chinese vessels in their waters. Other claimants are “essentially being bullied out of their own EEZs and out of what is supposed to be an area of freedom of passage,” says Joshua Kurlantzick of the Council on Foreign Relations.

What does this have to do with the U.S.?

The South China Sea is thought to contain huge oil and natural gas reserves, and around one-third of the world’s maritime trade is estimated to pass through it, worth more than $3 trillion every year. Washington sees free movement through the area as essential, and conducts “freedom of navigation” naval patrols to protect it. “From the U.S. perspective, the nine-dash line map is an attempt [by China] to privatize the global commons,” says Professor Murphy.

U.S. officials have framed China’s behavior as a challenge to the rule of law. Washington also has important allies in Southeast Asia, and aims to push back on China’s increasing dominance in the region. “It’s not only Southeast Asia, but the world has now woken up to the fact that they can’t live without China,” says Professor Chin.

In Beijing’s eyes, the South China Sea is its backyard and Southeast Asian countries are wary of alienating a key economic partner. “We’ve always lived under the dragon. The Southeast Asian attitude is that we cannot run away from the Chinese shadow,” Professor Chin adds.

What’s next?

Many regional economies took a beating during the pandemic. In the meantime, China has been pushing ahead, building more artificial islands and military bases. “It’s probably angered a lot of countries in the region because it makes it seem like China is not only continuing in a very assertive approach, this is actually taking advantage of their vulnerabilities,” says Mr. Kurlantzick.

So far, the Biden administration has maintained the Trump administration’s hard line on China, and continues to conduct “freedom of navigation” operations. Mr. Biden has also pressured other democracies to take a stronger stance against Beijing. But in the South China Sea, a unified Southeast Asian effort “has a better chance than the U.S. and China sitting down and trying to resolve it,” Mr. Kurlantzick says.

Recently, some countries have taken small steps toward resolving competing interests. In April, Malaysia and Brunei agreed to jointly develop oil and gas fields along their maritime boundary. Malaysia and Vietnam have also indicated they will sign an agreement in an attempt to settle their differences. And in June, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and China pledged to avoid escalating tensions.

‘Creation care’: How churches aim to save a warming planet

The cause of global warming is often framed heavily around science – notably the physics of Earth’s atmosphere. But in the U.S., Canada, and beyond, religious values play a rising role in what many are calling creation care.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The group stands in a circle at the edge of a forest of maple, aspen, poplar, and oak. As the dozen congregants of Three Rivers Forest Church gather near Toronto on a recent Sunday, the Rev. James Ravenscroft is bridging their spirituality with the natural world. By extension he is also fortifying the fight against global warming.

In political and national discourse, climate change activists and churches are often pitted against one another, but many Christians like those in a growing Wild Church Network see stewardship of the environment as part of their religious mission. They form an important, and often overlooked, base in one of the globe's most pressing issues.

Some public opinion polls suggest that Christians’ engagement on the issue has risen in the past few years. And in Canada, many faith communities are beginning to take more concrete political action on climate.

“My climate activism is not standing outside with a sign,” says Mr. Ravenscroft. “I think it is tapping into something that people are feeling. And partly it’s that we’re super disconnected, and that sense of disconnection is drawing them back into creation to reconnect.”

‘Creation care’: How churches aim to save a warming planet

The group stands in a circle at the edge of a forest of maple, aspen, poplar, and oak.

At this “wild church” north of Toronto, member Paula Windsor reads from Hermann Hesse’s “Ode to Trees.” “Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree,” she reads from the 20th-century work.

When she finishes, the Rev. James Ravenscroft traces the ideas in the secular text to Scripture. “If we pay attention, we hear something similar in a sense when we hear Genesis 2:9,” he tells the dozen congregants of Three Rivers Forest Church on a recent Sunday. “‘Out of the ground, God made to spring up every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food. The tree of life was in the midst of the garden, as well as the tree of knowledge of good and evil.’”

There are more readings about trees and their place in cultures and histories around the world. Mr. Ravenscroft leads a meditation, and then he encourages all to walk into the forest of Twickenham Park in Richmond Hill and find a tree with which to connect. “Go with openness,” he says.

In doing so, he is bridging their spirituality with the natural world – and by extension fortifying the fight against global warming. In political and national discourse, climate change activists and churches are often pitted against one another, but many Christians like those in the Wild Church Network see stewardship of the environment as part of their religious mission. They form an important, and often overlooked, base in one of the globe’s most pressing issues.

“My climate activism is not standing outside with a sign,” says Mr. Ravenscroft. “I think it is tapping into something that people are feeling. And partly it’s that we’re super disconnected, and that sense of disconnection is drawing them back into creation to reconnect. And I think part of it is ecologically the crisis of climate change is drawing people. They just recognize that you’re not going to protect something you don’t love. And the best way to fall in love with creation is to spend time with her.”

People concerned about global warming come from all faith-based and secular traditions, of course. But engagement on the issue by people of Christian faith in the United States appears to have risen compared with prior years, across the board from Roman Catholic to evangelical and other denominations, according to a 2020 poll conducted by climate communication programs at Yale and George Mason universities.

In Canada, as the urgency around the climate has grown, many faith communities are beginning to take more concrete political action that goes well beyond their religious convictions, says Karri Munn-Venn, senior policy analyst at Citizens for Public Justice, a Canadian organization that fights for social and environmental justice through a lens of faith.

On a recent morning, the Christian conservation organization A Rocha is hosting a virtual festival to replace a biennial, in-person gathering of national leaders. It’s invited Katharine Hayhoe, a Canadian climate scientist and evangelical living in Texas, as a keynote speaker, and one of her plenary sessions addresses how to respond to climate change with a Christian framework in such a polarized and hostile atmosphere.

She lays out the climate emergency that she has spent her career as an atmospheric scientist studying. And then she reminds the group, which has gathered from around the world, that Christians are taught from Genesis 1 about their responsibility over every living creature. “Rather than dragging our heels at the end of the line, if we really take the Bible seriously, we would be out of the front of the line demanding climate action,” she tells them.

Yet religion and ideology have become so intertwined – a phenomenon largely emerging from the U.S. but affecting Christianity around the world – that often Christian leaders are heard calling climate science hype or a hoax, that scientists are godless, and climate action is a false religion of Earth worshipping.

That zero-sum framework is unrecognizable to many Christians who view protecting the natural world as an extension of their spirituality – and don’t wish to be placed in camps.

“Hope isn’t just twiddling our thumbs”

Leah Kostamo, who co-founded A Rocha Canada, eschews the label “environmentalist.” In the research, education, and sustainable agriculture that it carries out on a farm in British Columbia, it employs Christian language of stewardship and creation care. “There are over a thousand passages in the Bible that mention creation,” she says. “And just like Christians would be for justice, Christians would be for caring for the poor, Christians would be for building community, for helping neighbors – all the best parts of ‘civic’ Christianity – we would want people’s scope of imagination to widen a bit so that Earth stewardship is a normal, natural part of faith.”

Ms. Kostamo, who wrote the book “Planted: A Story of Creation, Calling, and Community,” says their work as Christians is not about throwing up one’s arms. She was inspired by Joanna Macy, an environmental activist, scholar of Buddhism, and author of “Active Hope,” which addresses climate change without despair or doom. “I would say that is a very Christian model of hope, too. Hope isn’t just twiddling our thumbs and saying ‘my hope is God will rescue us from all of this’ or that God is going to wave a magic wand over the climate or over the missing species,” she says. “Hope is more ... we work alongside God in God’s creation for that redemption, whatever that looks like.”

The United Church of Canada, the country’s largest Protestant denomination, has been one of the most progressive on climate change – aiming to reduce its carbon footprint by 80% by 2050 and voting to divest its holdings from the largest fossil fuel companies. But Ms. Munn-Venn says religious Canadians of all faiths are joining the fight.

Her group, along with Kairos Canada, an ecumenical justice organization, launched a faith-in-action campaign in February, targeting key Cabinet ministers in Canada to address the global climate emergency. It follows a campaign they launched with faith groups on Earth Day last year to help push Canada to transition to net zero by 2050.

“One of the things that I’ve observed is a real growth in terms of the number of faith communities in the Christian tradition, but in Muslim and other traditions as well, where creation care and climate action and climate justice are really central pillars,” says Ms. Munn-Venn. One key motivation, she says: “We would have greater potential to have a greater impact if we all came together.”

A renewal for religion?

Victoria Loorz, a co-founder of the Wild Church Network that has its base in the U.S. and Canada, believes that wild churches not only form an environmental base, but are in turn helping to renew faith in religion.

The network has grown since its founding in 2016 to over 100 churches either in operation or in development. The pandemic, which closed so many church doors, spurred interest in not just holding services outside but in connecting with the natural world at a time when church attendance has been in decline. “I really see the wild church movement not just as a cool little ... side thing for people who love nature. I see it as a point of reformation,” she says. “It’s not just to get people involved in the environmental movement, but to restore a severance that we suffer spiritually from, we suffer emotionally from, and obviously we’re suffering ecologically from.”

In the middle of an afternoon in downtown Toronto, the Rev. Jason Meyers of the Metropolitan United Church stands on the church lawn. The church sits at a busy intersection of office space and hospitals, but Taddle Creek once ran through here. “Taddle Creek Wild Church” began gathering here this month, with a poem written by its poet-in-residence, Patricia Orr, to the lost river system.

“Nothing is wasted / Just as the clouds / return the water / that once flowed along Taddle Creek, creek turned rain on the roof of the grand old church,” the first lines read.

For many religious leaders, there is a role for the church in this issue just as there was in fighting against slavery in the 19th century or for the rights of refugees today. For Mr. Meyers, climate change is a top priority, whether that’s reflected in encouraging church members to engage politically, committing to energy efficiencies, or supporting the creation of a wild church.

“In a real way we’re reframing what church is, and pointing towards big issues that we face, like food insecurity, like climate change,” he says. “In the practicing of our spirituality we can engage with these big issues.”

Book review

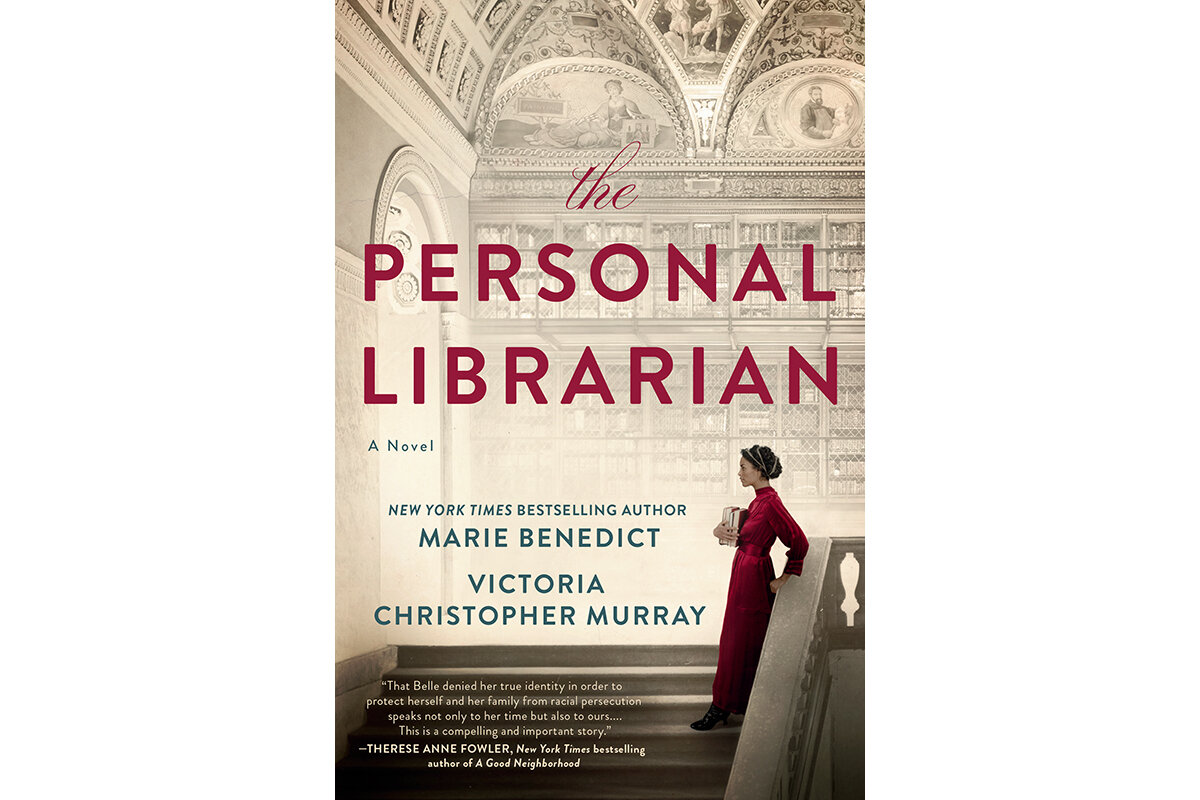

J.P. Morgan’s librarian hid her race. A novel imagines the toll on her.

How much would you be willing to sacrifice in order to advance? At the turn of the 20th century, some Black people chose to “pass” as white in a bid to circumvent racism and segregation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Heller McAlpin Correspondent

At the turn of the 20th century, light-skinned Black people sometimes chose to “pass” as white to enhance their prospects in the face of legally sanctioned racial discrimination in America.

In the case of Belle da Costa Greene, her mother was willing to break ties with extended family and even become estranged from her husband so that her children could advance. Although often mistaken for a white man, he believed that all Black people should unite to fight against prejudice rather than “trying to cross the color line.”

Told from Greene’s perspective, “The Personal Librarian” deftly conveys her deep knowledge of medieval illuminated manuscripts; her skill in handling her mercurial, overbearing boss, J.P. Morgan; and her prowess in navigating the rarefied circles of art dealers and Gilded Age society. But the book never loses sight of the cost incurred by her family secret through all these professional triumphs.

Although Greene has been written about before, “The Personal Librarian” introduces her story to a wider audience.

J.P. Morgan’s librarian hid her race. A novel imagines the toll on her.

Some books leave you wondering why the author has chosen to tell this particular story, and why now. This is emphatically not the case with “The Personal Librarian,” a novel about the woman who helped shape the Morgan Library’s spectacular collection of rare books and art more than a century ago. It quickly becomes clear why two popular authors, Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray, have teamed up to tell this important, inspirational story.

Belle da Costa Greene’s success in the almost exclusively male world of art and rare book dealers was an unusual feat for a woman in the early 20th century. But what makes it even more extraordinary – and such rich material for historical fiction – is the secret she harbored throughout her long career: She hailed from a prominent, light-skinned Black family, many of whose members had chosen to pass as white.

“The Personal Librarian” reminds readers that this decision was not made lightly. After the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act in 1883 – a ruling that ushered in Jim Crow segregation and gave white supremacy and racial discrimination legal cover, the ramifications of which are felt to this day – few opportunities were open to anyone classified as nonwhite.

For Greene’s pragmatic mother, Genevieve Fleet Greener, passing as white became the best option to enhance her children’s prospects in an increasingly segregated, racist America – even though it meant breaking ties with her close-knit family in Washington. Worse, it meant estrangement from her husband, Richard Greener – a professor of law and prominent advocate for civil rights who was the first Black graduate of Harvard University. Although often mistaken for a white man, he believed that all Black people should unite to fight against prejudice rather than “trying to cross the color line.”

To explain her olive complexion, “da Costa” was added to Greene’s altered surname to represent an invented Portuguese grandmother. She was still in her 20s when J. Pierpont Morgan – imposing business magnate, passionate bibliophile, and known philanderer – hired her away from Princeton University’s rare books collection in 1905 to curate his new library in Manhattan.

Told from Greene’s perspective, “The Personal Librarian” deftly conveys her deep knowledge of medieval illuminated manuscripts, her skill in handling her mercurial, overbearing boss, and her prowess in navigating the rarefied circles of art dealers and Gilded Age society. But the book never loses sight of the cost incurred by her family secret through all these professional triumphs.

Stories about racial passing have long been fixtures of American literature, including Nella Larsen’s novel “Passing” (1929), Philip Roth’s “The Human Stain” (2000), and Brit Bennett’s “The Vanishing Half” (2020). These books, along with Bliss Broyard’s memoir, “One Drop” (2007) – which grew from her discovery that her father, literary critic Anatole Broyard, had a hidden multiracial history – underscore the high stakes for people who dare to cross the color line. More importantly, they highlight both the outrage and absurdity of racial prejudice.

The authors of “The Personal Librarian” make it clear that many Black people like Greene and her family owe their light skin to the sexual violence inflicted on enslaved Black women by white men. Yet later in life, and despite past and present trauma, their tenacious, accomplished heroine assesses her remarkable career, declaring, “I presented proof of the heights that colored folks could fly if untethered from racist bindings.”

In this telling, even Greene’s father, the author of a prescient essay titled “The White Problem,” comes to respect the “life of meaning” his daughter has forged for herself. But he also holds out hope for a better future when he says, “One day, Belle, we will be able to reach back through the decades and claim you as one of our own.”

And here we are, in 2021, a year after George Floyd’s murder and the ensuing outrage and Black Lives Matter demonstrations it provoked, reading about the true heritage of J.P. Morgan’s personal librarian.

The backstory behind “The Personal Librarian” adds another intriguing dimension. Historical novelist Benedict, whose previous subjects include Lady Clementine Churchill and Hedy Lamarr, learned about Greene many years ago from a docent in the Morgan Library. But she felt she needed a collaborator, particularly for the Black perspective. She chose Victoria Christopher Murray, author of a fiction series, “The Seven Deadly Sins,” as well as “Stand Your Ground,” a sensitive contemporary novel about the shooting of a Black teenager by a white police officer. In an author’s note, Murray writes that her own light-skinned grandmother occasionally passed as white.

Their teamwork has yielded an engrossing, well-researched read, which the authors assure us is anchored in “the available facts.” Liberties have, of course, been taken, and it’s mostly in these imagined scenes of high drama – such as the physical tension between Greene and her possessive, much older boss – that the writing often feels overheated.

The prose turns positively purple when it comes to Greene’s affair with art historian Bernard Berenson, a Lithuanian-born Jew who passed himself off as a Boston Brahmin. (He does not come across well.) Air and voices grow “thick with emotion” to connote sexual desire. Other, smaller stumbling blocks include anachronistic expressions like “it came with the territory,” “I feel seen,” and “compartmentalizing my sadness.”

That said, Greene is an inspiring, compelling heroine. Although she has been written about before – most notably in Heidi Ardizzone’s biography, “An Illuminated Life: Belle Da Costa Greene’s Journey from Prejudice to Privilege” (2007) – one hopes that “The Personal Librarian” will introduce her story to a wider audience.

In addition to the Monitor, Heller McAlpin reviews books regularly for NPR, The Wall Street Journal, and the Los Angeles Times.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

South Africa’s step toward equality before law

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The main work of South Africa after white rule ended in 1994, the late Nelson Mandela often said, was the reconstruction and development of “the soul” of its people – of any color. That work took a big leap Tuesday when the country’s highest court ordered a former president, Jacob Zuma, to be imprisoned for 15 months over his defiance of the court in a corruption scandal.

The ruling against such a powerful figure in the African National Congress sends a message of accountability. Namely, the message is that the presumption of impunity can no longer be taken for granted. The court’s signal of equality before the law also resonates with a public eager for honest, clean, and effective public services.

The court did hint at Mr. Mandela’s call for “soul” work among South Africans. It said Mr. Zuma had insulted the country’s post-apartheid constitutional democracy “for which so many men and women have fought and lost their lives.” The principles of a democratic state cannot allow leaders to be a law unto themselves. If the court-defying former president does end up in prison, South Africans will see those principles in action.

South Africa’s step toward equality before law

The main work of South Africa after white rule ended in 1994, the late Nelson Mandela often said, was the reconstruction and development of “the soul” of its people – of any color. That work took a big leap Tuesday when the country’s highest court ordered a former president, Jacob Zuma, to be imprisoned for 15 months over his defiance of the court in a corruption scandal.

The ruling against such a powerful figure in the African National Congress (ANC) sends a message of accountability down through the ruling party and into elected officials and government workers. Namely, the message is that the presumption of impunity can no longer be taken for granted. The court’s signal of equality before the law also resonates with a public eager for honest, clean, and effective public services.

The ruling was necessary because Mr. Zuma had ignored an order to appear before a commission of inquiry into corruption. It remains to be seen if he will now show up for prison or whether his armed supporters will prevent police from implementing the court order. The ruling cannot be appealed.

The court was specific that it was setting an example for the authority of the judicial branch in being fair to all citizens. This will put some wind behind the efforts of the current president, Cyril Ramaphosa, in curbing corruption and patronage within the party. In 2018, he led the ouster of Mr. Zuma as corruption charges built up against him. Mr. Ramaphosa has since dismissed several high-ranking ANC officials over allegations of corruption.

“For the first time in South Africa, we are seeing a former head of state held directly accountable by way of a prison sentence,” said Karam Singh, head of legal and investigations at Corruption Watch, a watchdog on government. The symbolism of the ruling may also echo across the rest of Africa, where leaders often defy or manipulate courts to hold on to power or use corruption to garner support from the elite.

The court did hint at Mr. Mandela’s call for “soul” work among South Africans. It said Mr. Zuma had insulted the country’s post-apartheid constitutional democracy “for which so many men and women have fought and lost their lives.” The principles of a democratic state cannot allow leaders to be a law unto themselves. If the court-defying former president does end up in prison, South Africans will see those principles in action.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Where is our faith?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Everyone has a God-given ability to trust in and discern the healing goodness of the Divine, as this poem highlights.

Where is our faith?

We all have faith in something.

Is it faith that removes mountains

(whatever obstacles) – trust

in God, good, that won’t budge?

Or,

is it clinching unbelief that

obscures the doors to possibility?

Faith that all good is possible flows

from God, divine Love, to everyone.

It comes gently, unfalteringly to thought,

like morning light to a waking eye,

an unquenchable flame in darkness,

a cairn in a pathless land,

a bridge over torrents.

Faith catches the fresh reality of God’s

limitless love for us as sons and daughters,

tangible even in misted moments. Then,

like a river, faith merges into an ocean

of spiritual light and we grasp Love’s

tenderness and care – fathomless and

unquestionable – opening doors to healing.

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Explore other recent content from the Monitor's daily Christian Science Perspective column.

A message of love

Fun in the mud

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for today. Tune in tomorrow when we look at a program that turns boarded-up shops into ersatz art galleries.