- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Racial bias in voting laws? Supreme Court makes it harder to prove.

- Communist Party at 100: Will Chinese nationalism at home backfire abroad?

- Can an election mend a fractured nation? In Ethiopia, a stern test.

- Why free speech is under attack from right and left

- Protecting fur and fins: Bans on fashion in Israel and fishing in Jamaica

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The allure of mystery on Mars

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

When scientists use radio waves to peer under the ice cap at Mars’ south pole, they have no idea what they’re seeing. There is certainly something odd there. When the first images of the objects appeared three years ago, astronomers thought they were lakes – miles-long stretches of liquid water hiding beneath the Martian surface.

Now they’re not so sure. New data released this week by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory suggest the things are too near the surface to be liquid water. They sit at a depth where the temperature is minus 81 degrees Fahrenheit. Even salty water should be frozen in those conditions. Yet there they are, a tantalizing hint of a discovery that could hold alien life or otherwise reshape our understanding of Mars – or be nothing of consequence, really.

When Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli mapped Mars’ surface in 1877, he found curious formations he called “canals.” What were they? How did they form? The finding fascinated scientists and generations of science fiction writers in ways that still color our romance with the red planet. Discovery is science’s aim. But mystery is its allure.

Do lakes lie under the surface of the Martian south pole? Some day, surely, we will know. But for now, the only answers are left to the imagination.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Racial bias in voting laws? Supreme Court makes it harder to prove.

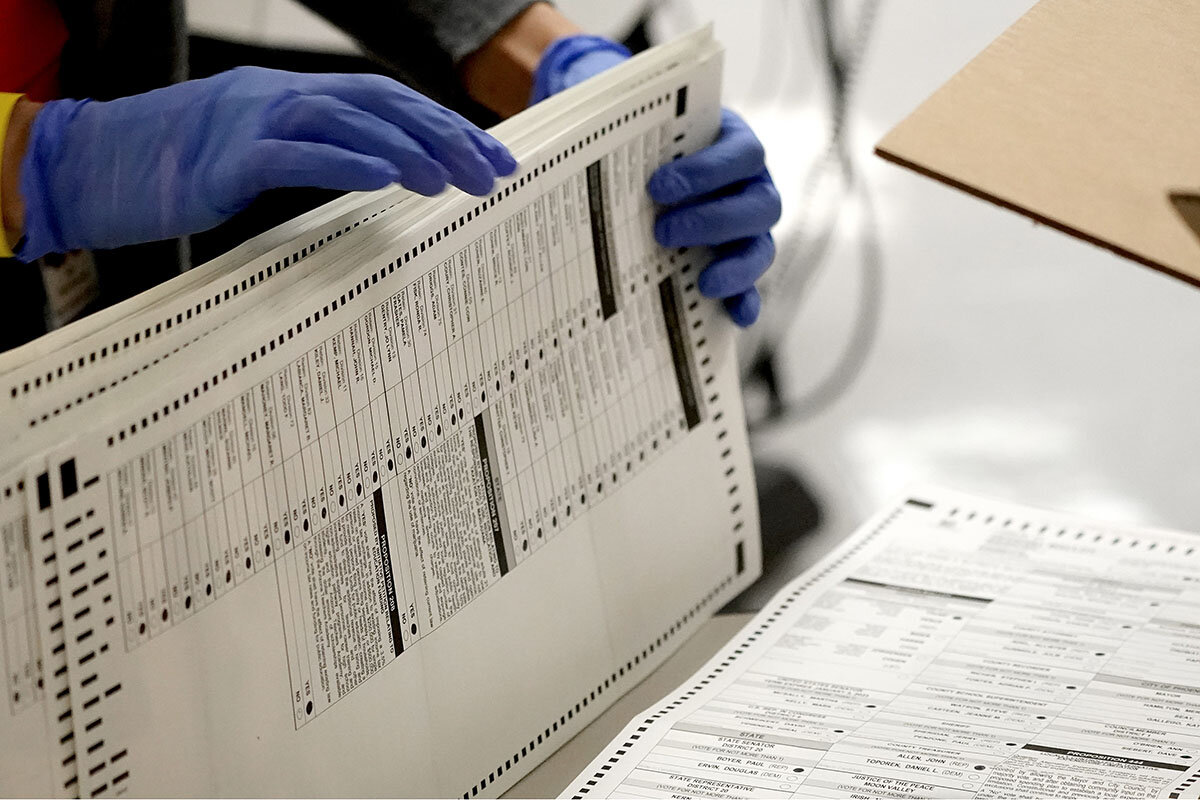

The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965 to protect minority voters. The Supreme Court ruled it was being too stringently enforced in one Arizona case, giving states freer rein to enact restrictive voting laws.

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

At a time when voting rights laws are at the forefront of American politics, today’s Supreme Court ruling was always going to be one of the biggest of the term. Could Arizona proceed with two provisions that, Democrats argued, would disproportionately hurt minority voters?

The landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed specifically to protect minority voters. But in this case, the Supreme Court – led by its six conservative justices – decided that Arizona’s provisions did not cause enough harm to invoke the protections of the Voting Rights Act.

The restrictions in question “are far from the most egregious voting rights violations,” noted one legal observer. Yet the case continued a trend. Under Chief Justice John Roberts, the court has chipped away at the the Voting Rights Act. This decision does not “write the Voting Rights Act out of law, but it comes close,” says Steven Schwinn, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law.

Along the way, it could also give momentum to Republican state lawmakers looking to tighten election regulations.

Racial bias in voting laws? Supreme Court makes it harder to prove.

At a time when voting rights disputes have become increasingly central to politics in the United States, the Supreme Court may be likely to support many of the current Republican state efforts to tighten election regulations.

That is one major takeaway from the court’s highly anticipated ruling, issued Thursday, that upheld two Arizona voting restrictions. A lower court had said the restrictions discriminated against minority voters.

Writing for the majority in the 6-3 ruling, Justice Samuel Alito said the restrictions were relatively small and need to be considered in the context of the overall ease of voting in Arizona. They did have some disproportionate effect on minorities, but that slight difference should not be “artificially magnified,” he said.

Critics of the decision said it rested on a narrow reading of the Voting Rights Act, a broad civil rights era law that bans racial discrimination in voting. Under Chief Justice John Roberts, the court has been chipping away at that act, says Steven Schwinn, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law.

In 2013, the court essentially invalidated the law’s requirement that some states get federal clearance before making election changes. Now it is making it harder to prove out-and-out racial discrimination, says Professor Schwinn.

“They don’t write the Voting Rights Act out of law, but it comes close,” he says.

Understanding the case

The case at issue, Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, was one of the biggest cases of the term. Its 6-3 vote was split along ideological lines, with conservatives in the majority and the three liberal justices in dissent.

In the case, the Democratic National Committee challenged Arizona’s Republican secretary of state and the Republican National Committee regarding two election law provisions.

One is the “out of precinct” policy, which requires election officials to throw out the ballot of any voter who votes in a precinct other than their own, including their choices for statewide or national offices. The second is a state law making it a felony to collect and deliver another person’s absentee or mail ballot, with exceptions for family members and authorized caregivers.

Both these disproportionately hurt minority voters, the DNC argued in court. In the first case, minority voters are more likely to move often, live in urban areas with many precincts, and have jobs leaving them little time off to vote, according to the DNC. In the second, minority voters are more likely to need ballot collectors because they are more likely to be poor or homebound, lack reliable transportation, or need help understanding the voting process.

For the Democratic Party, bringing the case was something of a risk to begin with. The Arizona policies in question “are far from the most egregious voting rights violations,” wrote Richard Hasen, a professor at the University of California, Irvine School of Law, prior to oral arguments in the case. Challenging them all the way to the Supreme Court could give the conservative justices an opportunity to weaken the remaining key Voting Rights Act provisions.

Effect on new voting laws

In the end, the justices did not go as far as some critics worried they might. But they did narrow key aspects of the Voting Rights Act. That might make it more difficult for Democrats to challenge aspects of the many new Republican-pushed laws on voting and elections, which have passed in Georgia and Florida and are moving through other states.

In his majority opinion, Justice Alito wrote that while Arizona generally makes it very easy to vote, voting is an act that places some level of “burden” on everyone. “Mere inconvenience” in the voting process is not a violation of the law.

The presence of some disparities between groups of voters “does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open,” wrote Justice Alito. The provisions in question need to be seen in the context of how much more difficult it was to vote in 1982, he added, which was the last time the Voting Rights Act section on discriminatory laws was amended.

This perspective is a “cramped standard” that ignores legal and technological changes over the intervening time, said Debo Adegbile, a partner at the legal firm WilmerHale. He appeared at an American Constitution Society event following the close of the court’s term.

It’s clearer than ever there are two ways to win elections in the U.S., said Mr. Adegbile. One is by mobilizing voters and trying to win them over. The other is by narrowing – demobilizing voters who lean toward your opponent.

“These are both long traditions in American politics,” said Mr. Adegbile.

A divided court, for once

In the short term, the most important effect of the Brnovich decision may be its ramifications for the coming legal struggle over the many other new state voting provisions. The Department of Justice, for instance, has already filed suit challenging what it deems to be racially discriminatory provisions of Georgia’s new election law.

Narrowly speaking, the Department of Justice lawsuit should be unaffected by Thursday’s decision. It charges that some Georgia provisions are intentionally discriminatory, while the Arizona case involved provisions that the DNC claimed simply produced a discriminatory result.

But the Arizona ruling “is just going to make it a lot more difficult to lodge challenges to these practices,” says Professor Schwinn.

That’s significant in the current political climate, he says.

Professor Schwinn adds that in most major cases this term, the court has seemed to look for a minimalist approach, finding consensus around narrow issues, producing rulings not decided along predictable ideological lines.

That changed on Thursday, the court’s last day of issuing opinions. The Arizona case was decided via an ideological split that many experts predicted would develop after the conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett replaced the late liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“We expected to see more of these sharply divided 6-3 opinions that have a significant impact on the law,” says Professor Schwinn.

Communist Party at 100: Will Chinese nationalism at home backfire abroad?

When does love of country go too far, perhaps damaging its own country’s purposes? Beijing’s dialing up of extreme nationalism could risk unintended consequences.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

China’s Communist Party turns 100 Thursday, after months of buildup and fanfare. Officials have been hammering home messages about the superiority of socialism and the necessity of party control for China’s continued rise, stoking nationalist pride. Meanwhile, they are also playing up perceived threats to China, amplifying the narrative that “hostile foreign forces” are bent on keeping the country down.

Beijing’s combative diplomacy – executed by envoys who call themselves “wolf warriors,” after the title of a blockbuster film – has reached new extremes in recent months. And as leader Xi Jinping continues to consolidate power at the party’s helm, that “wolf warrior” approach will likely widen a gap, analysts say: the type of diplomatic messaging that would appeal to foreigners, on the one hand, and the sort demanded by an increasingly hawkish Chinese public, on the other.

That poses a danger to China, experts abroad say, of isolating the nation of 1.4 billion people at a time when it needs openness and innovation.

“Increasingly, ‘wolf warrior’ China is turning the world off in important ways to China as a global actor,” says Jude Blanchette, Freeman chair in China studies at the Center for International and Strategic Studies.

Communist Party at 100: Will Chinese nationalism at home backfire abroad?

As propaganda marking the 100th anniversary of China’s Communist Party hits fever pitch, party-controlled media outlets are gushing images of red flag-waving crowds and patriotic performances from across the country.

“I compare the party to my mother,” costumed folk singers and onlookers belted out from a plaza in Ulanhot in Inner Mongolia. “My mother only gave birth to me – the glory of the party shines in my heart,” they crooned, in what was billed as a serenade for the party in a recent segment on China Central Television’s evening news.

China’s leaders are using the party’s July 1 birthday to stoke nationalist pride and solidify their power, hammering home messages about the superiority of socialism and the necessity of party control for China’s continued rise. But they are also playing up perceived threats to China, amplifying the narrative that “hostile foreign forces” are bent on keeping China down.

Beijing’s combative diplomacy – executed by envoys who call themselves “wolf warriors,” after the title of a 2017 blockbuster action film – has reached new extremes in recent months. In June, for example, Chinese diplomat Zhang Heqing tweeted an image of a vulgar hand gesture (which now appears to have been deleted), saying it showed “the way we deal with enemies.” “We are wolf warriors,” wrote Mr. Zhang, a cultural counselor at the Chinese Embassy in Pakistan.

The danger to China, analysts abroad say, is that the nationalist playbook of Chinese leader Xi Jinping will isolate the nation of 1.4 billion people at a time when the country needs openness and innovation to tackle problems ranging from an aging population to slowing economic growth.

“The traditional connections ... that China has had with the outside world, and the outside world has had in China, are at risk if this general political direction continues, with a paranoid view of the world that’s disseminated within and a very ‘wolf warrior’ approach to the outside world,” says Jude Blanchette, Freeman chair in China studies at the Center for International and Strategic Studies in Washington.

“Increasingly, ‘wolf warrior’ China is turning the world off in important ways to China as a global actor,” he says. This, in turn, could constrict Chinese companies overseas, opportunities for China in multilateral institutions, and China’s ability to integrate with other economies, he suggests.

Growing gap

Indeed, a Pew Research Center survey of 17 advanced economies in Asia, Oceania, Europe, and North America released Wednesday showed broadly that views of China and confidence in Mr. Xi are at or near historic lows, with large majorities saying Beijing does not respect its people’s personal freedoms.

In Australia, for example, confidence in Beijing as a responsible world actor and economic partner has plummeted since 2018, when 52% of Australians said they trusted China. Nearly two-thirds of Australians now see China as a security threat to their country, according to an annual poll by the Lowy Institute released last week.

In Southeast Asia, China is viewed as the most important economic and political power in the region, but this also generates worries over Beijing’s growing clout, according to a February survey of experts in member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, conducted by the ASEAN Studies Center of the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. The majority polled said that if they had to take sides between the United States and China, they would choose the U.S, with the number choosing China dropping from 46.4% in 2020 to 38.5% this year.

“China’s reputation ... in large parts of the world, particularly in the more developed world, has been going steadily down,” says Rana Mitter, director of the University of Oxford China Center and author of “China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism.”

As Mr. Xi continues to consolidate power at the party’s helm, the gap is likely to widen further between the type of diplomatic messaging that would appeal to foreigners and the sort demanded by an increasingly hawkish public inside China, analysts say.

In May, for example, the CCP’s Political and Legal Affairs Commission posted images on Weibo, China’s Twitter, that contrasted the burning of mass funeral pyres amid India’s worst coronavirus wave with China’s recent rocket launch, under the words “China’s ignition vs India’s ignition.”

Inside China, online ultranationalists widely defended the post, which was later taken down, and criticized conservative commentators who expressed reservations as being too soft. Those attacked included even stalwart party backers such as Hu Xijin, editor of the jingoistic, party-affiliated newspaper Global Times.

Ultranationalists online have also labeled as “traitors” nearly 200 Chinese intellectuals who participated in Japanese government-funded exchange programs in Japan between 2008 and 2019. And in March, a Chinese official proposed that the government end the mandatory teaching of foreign languages, and drop English as a requirement for university entrance tests.

Shift in tone?

There are indications that the party recognizes the risk that stoking nationalism to bolster its legitimacy at home could isolate China and constrain its foreign policy options. The party’s Politburo recently held a study session on the need to “tell China’s story well,” at which Mr. Xi said the country faces a “public opinion struggle” and urged officials to build a “credible, lovable, and respectable” image of China.

“Our discourse ... lags behind the scale and speed of our country’s rise,” wrote Zhang Weiwei, who attended the study session, in Beijing Daily. He called for Chinese officials and scholars to “establish our own political narrative of China” and deconstruct the West’s.

Nevertheless, China’s diplomats continue to “fight back” in what they call a protracted war with the West, their messages amplified on Twitter and Facebook by real as well as fake accounts, according to a recent study of the social media accounts of some 300 Chinese diplomats by Philip Howard, director of the Oxford Internet Institute. Meanwhile, Beijing is less likely to make foreign policy concessions or adopt a softer tone that the public would view as weakness, because that could incite unrest and undermine the party’s claim to rule, observers say.

The party is trying to “ride a line between wanting to try and create a kind of social media public in China that has this very strong sense that ... China has been treated badly by the world and that it must rise and find its place, but at the same time not allow enough of that, that it would actually undermine the government of the CCP itself,” says Professor Mitter, an expert in the history and politics of modern China.

Over time, party-backed rhetoric painting the world as a hostile place bent on subverting China’s political system could stifle public discourse, Mr. Blanchette says.

“The very open attitude Chinese people have had to integration and importation of outside ideas ... has been really important for the past four decades to facilitate China’s rise,” he says.

Adding to the isolation, Beijing’s stance toward foreigners and imposition of sweeping new national security rules are leading foreign professionals with long-standing China ties to become more reluctant to travel to the country, according to a recent, informal survey by the blog China File, an online magazine published by the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society.

“What does China look like 10 years from now, when you have no pragmatic liberal voices in the discourse?” wonders Mr. Blanchette. With an ultranationalist leader in Mr. Xi, whose tightening grip on power, domestic repression, and certainty in his direction mean less room for course corrections, “it’s a really nasty echo chamber that I think will continue to drive China.”

Can an election mend a fractured nation? In Ethiopia, a stern test.

Elections are seen as a peaceful way to help resolve political disputes. But without real dialogue, Ethiopia’s vote could only deepen the diverse country’s conflict over national identity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is heading toward a landslide election victory. But the pivotal moment he envisioned is being overshadowed by his government’s stunning defeats in its war in the Tigray region.

Set to preside over a country beset by famine and armed insurgencies, Mr. Abiy is armed with an electoral mandate that some view as absolute, but which large segments of the population consider illegitimate.

“The field was not fair and it was not free because not everyone participated,” says Tsedale Lemma, editor of the English daily Addis Standard. The election “polarized Ethiopia between those who absolutely celebrated the election and those who have been disenfranchised. … From this standpoint, this election has done more harm to the country than good.”

With a contested history, rival views of national identity, historic grievances, and alternative facts, Ethiopians are learning that elections cannot be a cure-all. Some say they need something more: a forum where they can be heard – and listen to one another.

“What is the golden balance between the domineering state and regional autonomy? What is our common view of history? Who are we as Ethiopians?” wonders Yonas Ashine, a political scientist at Addis Ababa University. “Elections are a limited tool that cannot answer these questions.”

Can an election mend a fractured nation? In Ethiopia, a stern test.

The election in Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous yet deeply polarized country, was billed as historic.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who had long made democratic elections a main goal of his administration, is heading toward a landslide victory.

But with the election results soon to be announced, the pivotal moment that Mr. Abiy had envisioned is being overshadowed by his government’s stunning defeats in its war in the Tigray region.

Set to preside over a losing war and a country beset by famine and armed insurgencies, Mr. Abiy is armed with an electoral mandate that some view as absolute, but which large segments of the population consider illegitimate.

With a contested history, rival views of national identity, historic grievances, and alternative facts, Ethiopians are learning that elections cannot be a cure-all for a divided nation.

As violence intensifies in both the north and south, some Ethiopians are finding they need something more than a ballot box to piece together their fraying social fabric: a forum where they can be heard – and listen to one another.

One election, two Ethiopias

At the heart of Ethiopia’s political divide are two different visions for the nation and its political system.

Mr. Abiy’s Prosperity Party, supportive Addis Ababa elites, and many Amhara communities want to reform Ethiopia’s ethno-national federal system. They say the 11 regional states set in the 1992 constitution have too much devolved power and are stalling the nation’s ascendance to become a regional powerhouse.

Conversely, regional communities and political movements say power has not been devolved enough, and that successive governments have failed to respect or implement the regional autonomy set out in the constitution.

In light of these dueling narratives – and even facts – Ethiopian observers say the elections failed to find common ground.

“What is the golden balance between the domineering state and regional autonomy? What is our common view of history? Who are we as Ethiopians?” asks Yonas Ashine, an assistant professor of political science at Addis Ababa University.

“Elections are a limited tool that cannot answer these questions,” he says.

Mr. Abiy, a self-billed reformist who came to power in 2018 on the back of popular protests through a reshuffle within the then-ruling coalition, had long prioritized democratic elections.

The Nobel Prize-winner moved ahead with the elections last week even while his federal forces are at war with Tigray, one of the 11 regions that make up the country, a conflict that has pushed 900,000 people into what the United States has described as a “man-made famine.”

Election strengths and weaknesses

On paper, Ethiopia had many of the ingredients for historic democratic elections: the participation of 47 political parties, including several opposition groups; civil society observers at polling stations; and more than 37 million registered voters out of a population of 110 million.

The centerpiece of what was billed as the freest elections in Ethiopia’s history is the independent Ethiopia Electoral Board. It is chaired by Birtukan Mideksa, a democracy advocate and opposition leader who was jailed by the previous ruling party and was enticed back to Ethiopia from exile abroad by Mr. Abiy’s promises of a democratic transition, reform, and freedoms.

Last week the board carried out the vote in more than 400 of the country’s 550 districts across a land that is three times the size of Germany and home to dozens of languages and a diverse topography.

In towns and villages people lined up at polling stations before dawn and straight into the night.

Particularly energized were supporters of the Prosperity Party, which ran on a platform of “peace and unity.” They say the prime minister is the man to bring calm to the country and transform the nation.

Residents say the vote in Addis Ababa, the capital of five million people, was the first open and competitive election in the city’s history.

But if the elections were largely free, international and Ethiopian observers warn that the playing field was far from fair. Federal authorities jailed several leaders of key opposition parties months before the delayed vote.

In Oromia, Ethiopia’s largest region and home to protest and armed movements that fought years of marginalization, the two main political parties’ offices were shuttered and staff reportedly harassed by authorities, prompting them to boycott the polls.

Elections did not take place in war-torn and famine-hit Tigray as well as several other communities, leaving roughly 20% of eligible Ethiopians unable to take part in the polls.

“The field was not fair and it was not free because not everyone participated,” says Tsedale Lemma, chief editor of the English daily Addis Standard.

“This has polarized Ethiopia between those who absolutely celebrated the election and those who have been disenfranchised from taking part in their constitutionally-guaranteed right to vote.”

“From this standpoint, this election has done more harm to the country than good.”

Violence

With the political path closed to some disenfranchised groups, more are likely to resort to violence, observers warn.

Recent weeks have reportedly seen a spike in recruitment and activity by the Oromia Liberation Army, an armed insurgent group that rejects the political process and believes the only path to greater autonomy for their region is through armed conflict with the state. Violent attacks on federal forces forced some polling stations to close.

And in Tigray, as the ballots were still being counted Monday, federal forces were routed and the Tigrayans, who defend ethnic federalism and oppose Mr. Abiy’s reforms, seized back their regional capital Mekelle in the north.

Its stunning battlefield losses prompted the federal government to declare a unilateral cease-fire in Tigray Tuesday, citing humanitarian concerns and the farming season.

But Tigrayan fighters have rejected Mr. Abiy’s cease-fire, even threatening to march on to the neighboring Amhara state to the West and Eritrea to the north.

“The rival views regarding the history, current structure, and future of the Ethiopian state are underpinning this chronic violence,” says William Davison, Ethiopia analyst for the International Crisis Group.

“The election did not settle these core disputes; indeed, in some important ways, they may well have exacerbated them.”

Search for common ground

Some Ethiopian observers argue that a national dialogue is the balm needed to heal Ethiopians historic wounds and current differences.

Rather than a majority-takes-all competition at the ballot box, they say Ethiopians need an inclusive forum where there are no winners or losers.

“We’re not saying, ‘Don’t have elections.’ We are saying ‘yes’ to elections,” says Mr. Ashine at Addis Ababa University, “but we also need dialogue and reconciliation alongside elections to bring disenfranchised groups to the table.”

As a model, some Ethiopians point to Tunisia, where civil society leaders and political figures gathered for dialogue following a 2011 revolution to find a common vision of the country’s future, an arduous process that eventually produced a constitution.

Others look to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a potential path to acknowledging the crimes committed by the state in previous decades against various communities.

Such dialogue, they argue, could address historical grievances such as the territorial dispute between the Amhara and the Tigrayans, which this year erupted into violence and alleged ethnic cleansing.

“We need to experiment and try all these diverse political processes in Ethiopia beyond elections to address the complex, deeply-rooted problems in our society,” Mr. Ashine says.

The Oromo Liberation Front, one of two main Oromo political parties who boycotted the elections, called for an “all-inclusive political dialogue,” noting that the “aggressive move for the election cost the country a tremendous amount of resources and human life.”

“Dialogue means there is a give and take, historical compromises, and agreeing to a fair game for all, not a zero-sum game of domination imposed by one group or one party,” says Merera Gudina, chairman of the Oromo Federalist Congress party, which also boycotted the elections.

“If there is political will, we can negotiate and draw a common road map. That is what Ethiopia needs today,” says professor Gudina. “If we do not come together and listen to understand one another, we may face disintegration.”

It remains to be seen whether Mr. Abiy, with the electoral mandate he so badly wants nearly within his grasp, will be in a mood to reach out.

A deeper look

Why free speech is under attack from right and left

Free speech is seen by many as the bedrock of American democracy. But in a time of polarization, right and left are challenging once-traditional ideals in different ways.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Liberals use the power of societal pressure to rewrite the norms of acceptable speech, “canceling” those who express ideas they consider prejudiced or hateful. Republican lawmakers pass a raft of laws reining in protesters or even telling public school teachers and university professors what they can and can’t teach – all in the wake of agitation for racial justice.

Not long ago, much of America seemed united over the ideal that “I may disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” Today, that ideal is evolving or under threat – or both. On one hand, America’s expression of free speech has always been selective, with explicit exceptions made for public safety and implicit exceptions often made against people of color.

Yet most still agree that the underlying ideal is essential to the health of American democracy. The challenge of the moment is discovering how that ideal can survive and grow at a time when left and right are pulling it in different directions. Says one professor trying to change the nature of public conversation nationwide: “Free speech should be used in service of truth-seeking discourse; it should not be seen as permission for anyone to say absolutely anything in any context without repercussions.”

Why free speech is under attack from right and left

The civic value of freedom of speech, enshrined in the First Amendment and woven throughout American culture, is often called the bedrock of liberty, the first principle from which all other political rights derive.

The free exercise of religion, a free press, the right to peaceably assemble and express grievances to the government and petition change – the basic right to speak up and speak out without the government interfering is, in theory, the cornerstone of American democracy.

But the nation has long struggled with it. In many ways, the country’s First Amendment ideals have been defined as much by the exceptions as the affirmations. Throughout American history, state and federal governments – as well as cultural practices – have deemed some public speech too dangerous.

At this bitterly polarized moment, those lines are particularly fraught. People on both the political right and left have struggled to navigate ever-evolving interpretations that are sometimes unfamiliar, sometimes at odds with one another. But in general, both sides in their own ways have begun to emphasize why government authorities, private businesses, or college administrators should more tightly regulate, if not suppress, certain kinds of public speech.

The battle lines are asymmetrical, with Republicans aggressively using new state laws to curtail protests and courses of study. Liberals, meanwhile, have relied predominantly on societal pressure to cull speech they find offensive or hateful. The result is that the ideals of free speech are being simultaneously reshaped in profoundly different ways by both ends of the ideological spectrum, challenging notions of free speech that not long ago were widely considered bedrock.

“It appears that the commitment to free speech is increasingly endangered in contemporary American society,” says Anthony DiMaggio, a political scientist at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Views from left and right

On one hand, he says, most of the talk has been “about the intolerance of liberal ‘cancel culture’ or big tech social media platforms that are deplatforming right-wing politicians and public intellectuals.” But such talk largely concerns cultural issues within mostly private arenas. That’s outside the purview of First Amendment law.

The deeper free-speech issues on the left and right have centered around the nation’s deep-seated conflicts over race, including various campus speech codes and prohibitions against hate speech.

In the past few months, Republicans in dozens of states have passed regulations aimed at Black Lives Matter protests while also proposing government bans on the teaching of critical race theory in public classrooms or faculty applying it research projects.

On the left, organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union, which has long made defending free speech its signature issue, has in many ways retreated from its historic mission to defend even the most repugnant speech.

“The old guys who remember the flag of Skokie and other free speech battlegrounds like me, they’re dying off,” says Bruce Rosen, a “proud member” of the ACLU and a former board member of a local chapter in New Jersey.

In one of the organization’s most famous cases, in 1977 a Jewish lawyer named David Goldberger helped defend the right of a Nazi group to peaceably assemble in Skokie, Illinois, a Chicago suburb that was home to a Jewish population including dozens of Holocaust survivors. Even then, the case caused many ACLU members to resign.

The internal tensions between some of the younger attorneys at the organization and the older guard came to a head in 2017, after ACLU attorneys helped defend the right of white supremacists to march in Charlottesville, Virginia. Violence erupted at the event, and a neo-Nazi driver stuck and killed a young woman and injured 19 others.

“Younger lawyers nowadays are asking two questions,” says Justin Hansford, director of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center at Howard University in Washington. “If you have a limited pool of resources – and you do – why spend those resources on a point of pride as opposed to spending them in areas that will help bring about a reality closer to what your true vision is?”

The ACLU also raised record amounts of money during the Trump administration, he notes. “And those people who are supporting the ACLU, are they really eager to see you represent the Nazis simply to uphold a principle to ensure that speech you hate the most is also represented in American society?”

Speech and public safety

The value of free speech is often couched in cultural aphorisms such as the old saying said to date back to the French Enlightenment: “I may disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” But another cultural aphorism, taken loosely from a 1919 Supreme Court ruling, proclaims, “You can not yell, ‘Fire!’ In a crowded theater.”

Legal precedent holds that people can be held liable for certain kinds of speech, such as false statements injure others’ reputations or rhetoric that incites others to violence. As such, the government has the power to restrain political speech that presents “a clear and present danger” to the country, especially during times of war, the Supreme Court has said. Civil authorities charged with maintaining public safety have also been permitted to regulate the time, manner, and place of protected speech and lawful assemblies.

Republicans are now aggressively using that discretionary power. During the past year, Republicans in 20 states have enacted some 36 new restrictions on the right to peaceful assembly, with 58 new bills still pending in other states across the country, according to a tracker at The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law.

In Florida, for example, the GOP-led legislature passed sweeping new penalties in April against protesters who damage property or cause injuries, making it a felony, and expanded the definition of “riot.” The law also made municipal governments liable for failing to “respond appropriately to protect persons and property during a riot or unlawful assembly,” among other new restrictions. Republican Governor Ron DeSantis called it “the strongest anti-looting, anti-rioting, pro-law-enforcement piece of legislation in the country.”

Florida, along with Oklahoma and Iowa, have also passed new laws giving immunity to drivers who strike protesters. States including Arkansas, Tennessee, and Texas have added new penalties for protesting near pipelines and other critical infrastructure, among other new restrictions. Other states have increased the fees necessary to obtain permits to assemble for a protest.

Speech and race

Professor Hansford of Howard University says he is “a big fan of free speech.” But as a legal scholar who applies critical race theory to his research, he’s found that the high ideals of free speech and assembly have never been fully and equally applied to Black communities throughout American history. His research has found that federal and especially state governments have long used their discretionary powers to ensure order to suppress the First Amendment rights of communities of color.

But the high ideals of free speech have never been fully and equally applied in the United States. Governments have long used their discretionary power to suppress the First Amendment rights of Black communities.

“There’s never been a moment where there was even close to a level of parity when it comes to freedom of speech protections,” he says. And even though the vast majority of Black Lives Matter protests have been lawful and peaceful, these laws’ emphasis on the instances of “rioting” and “looting” are an example of how First Amendment restrictions are directed against communities of color.

For him, the contrasting responses between the Black Lives Matter protest in Washington in June 2020 and the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6 speaks volumes. When Black people were protesting, fully armed National Guard troops in camouflage stood guard throughout Washington with police in riot gear. On Jan. 6, there was little security and no National Guard troops were deployed.

“And even more so now, if you take such restrictions out of the realm of protests and you look at this hullabaloo over critical race theory, we saw people who were, maybe just one year ago, really up in arms about violations of free speech on campus, and how we need more spaces for more people to say whatever they want. Now there’s literally laws being passed ... to stop people from thinking and expressing ideas about race and racial justice at these very same campuses,” Professor Hansford says.

Republicans in 26 states have introduced bills to restrict teaching critical race theory or limit discussions of race and social justice. Nine of these states, including Florida, Idaho, Tennessee, Texas, and New Hampshire have passed such legislation.

Last week, too, Florida Governor DeSantis signed a bill meant to stand against the “indoctrination” of students in public universities. It requires administrators to survey students and faculty about their viewpoints. The stated goal is to discover “the extent to which competing ideas and perspectives are presented” in public institutions and whether students and faculty “feel free to express beliefs and viewpoints on campus and in the classroom.”

Speech on campus

Such problems on American campuses are real, says Kenneth Lasson, a professor of civil liberties and international human rights at the University of Baltimore School of Law. “Those with opinions that might challenge campus orthodoxies are rarely invited, and often disinvited after having been scheduled, or shouted down or otherwise disrupted.”

“When protestors embroil visiting speakers, or break in on meetings to take them over and list demands, or even resort to violence, administrators often choose to look the other way,” he adds.

Many students do express they are increasingly “walking on eggshells” and experiencing what free speech advocates have long called the “chilling effects” of self-censorship, says Kyle Vitale, director of programs at Heterodox Academy (HxA), a nonpartisan collaborative of college professors and students committed to open inquiry and diverse viewpoints in higher education.

In a 2020 survey, HxA found that 62% of sampled college students agreed the climate on their campus prevents them from saying things they believe, up from 55% in 2019. And students across the political spectrum expressed reluctance to share their ideas and opinions on politics, with 31% of self-identified Democrats, 46% of Independents, and 48% of Republicans each reporting reluctance to speak their mind.

“Freedom of speech on college campuses is instrumental to the pursuit of knowledge and truth, though it is not an absolute good,” Mr. Vitale says. “Free speech should be used in service of truth-seeking discourse; it should not be seen as permission for anyone to say absolutely anything in any context without repercussions.”

“This is a subtle but important nuance that can help bridge the divide when it comes to the national conversation,” he says. Developing certain “habits of heart and mind” can foster diverse ideas and constructive disagreements. “Rigorous, open, and responsible engagement across lines of difference is essential in separating good ideas from bad, and making good ideas better.”

“Hearing, honoring, and respecting dissent, even when inconvenient, can sharpen one’s own position, expand one’s knowledge, and help us see that “conflicting doctrines share the truth between them.”

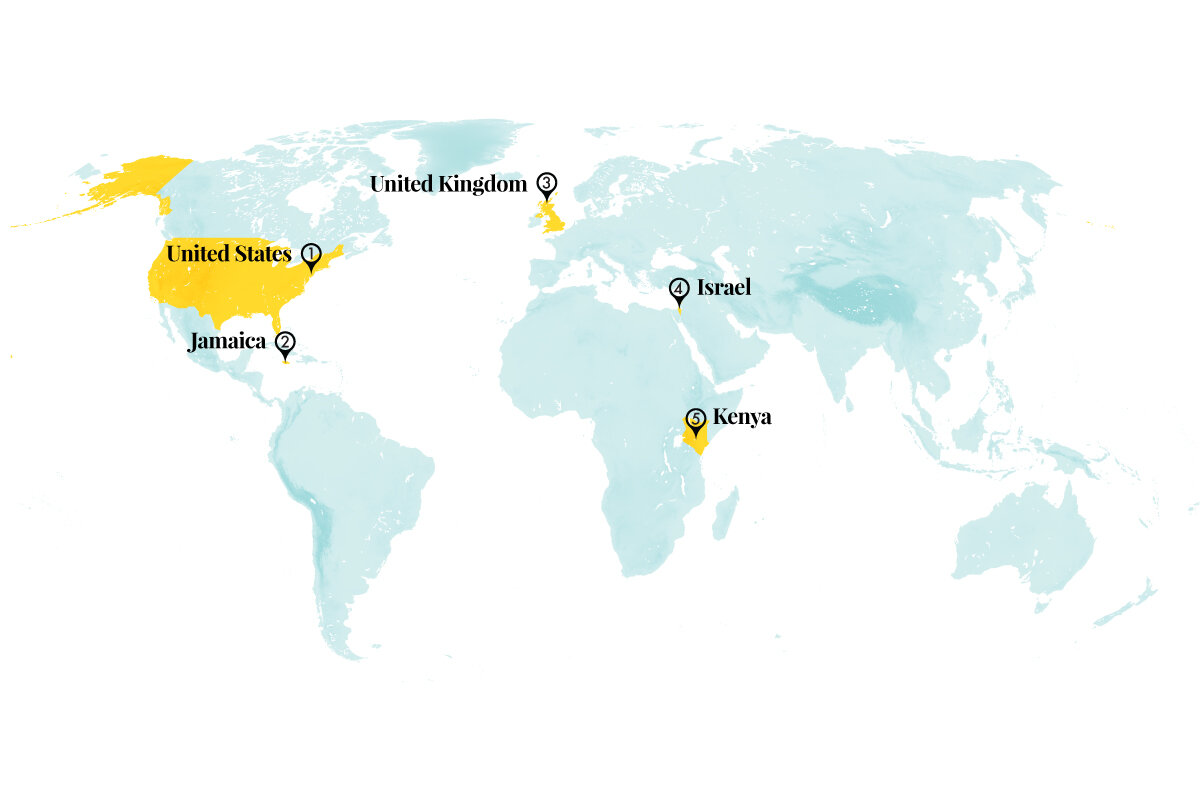

Protecting fur and fins: Bans on fashion in Israel and fishing in Jamaica

Our global roundup of progress this week includes both legal and cooperative means to an end. In Israel, fashion fur sales are prohibited by law. In Jamaica, fishers working with conservationists are key to the improving health of the ecosystem.

Protecting fur and fins: Bans on fashion in Israel and fishing in Jamaica

We highlight other firsts this week, including a new effort by a pair of online booksellers to help authors earn money from sales of their titles as used books.

1. United States

The U.S. Senate has confirmed the first Muslim American federal judge in the country’s history. Zahid Quraishi was confirmed by a vote of 81-16 to the U.S. District Court for New Jersey on June 10. He was among President Joe Biden’s first wave of nominees to fill judicial vacancies, and is the son of Pakistani immigrants.

The Rutgers Law School graduate also served two tours in Iraq following 9/11, and later became the first Asian American to sit on the federal bench in New Jersey when he was appointed as a U.S. magistrate judge. “He is a model for the outstanding contributions that Pakistani and Muslim Americans make to this country every day,” said Dr. Ijaz Ahmad, chairman of the American Pakistani Public Affairs Committee. “We are grateful to President Biden for nominating him, and to members of the Senate for confirming him.”

Axios, NPR

2. Jamaica

A unique fishing sanctuary is improving Jamaica’s coastal health and proving that community partnership is key to marine conservation. Bottom feeders like the parrotfish help clean algae from coral reefs, and healthy reefs, in turn, offer shelter for fish, mitigate shoreline erosion, and help maintain healthy oceans. Overfishing these species creates a domino effect that threatens the island’s tourism industry and coastal communities, with fishers forced to dive and look farther out to sea to catch fish.

To address this dilemma, a group of fishers partnered with the GoldenEye Foundation in 2011 to create a no-fishing zone on Jamaica’s northern coast. Today, 18 people work for the Oracabessa Bay Fishing Sanctuary, and all decisions are made through the Oracabessa Bay Marine Trust, which is composed of 50% fishers and 50% GoldenEye Foundation board members. Herbivorous fish abundance reportedly reached 6,792g/100m2 in 2020, up from 1,192g/100m2 in 2013. The project is set to continue its work with protecting fish, while also replanting coral and releasing sea turtles into the ocean. Its success has inspired other conservation groups, and the Oracabessa Bay Fishing Sanctuary is currently working to bring its management model to four other coastal sites in Jamaica.

Mongabay

3. United Kingdom

Leaders in Glasgow, Scotland, have committed to planting 18 million trees across the city – roughly 10 trees for every resident – in one of the United Kingdom’s most ambitious reforestation initiatives. Reforestation is considered a key strategy to mitigate climate change, as healthy tree cover helps slow erosion, promote biodiversity, and absorb CO2 emissions. Today, Glasgow has about 71,000 acres of fragmented broad-leaved woodland. The Clyde Climate Forest project aims to expand and connect these areas, and boost overall urban woodland cover from 17% to 20%. The pledge comes as the city prepares to host the United Nations COP26 climate summit in November.

Eight local councils have agreed to the initiative, which is funded in part by a £400,000 ($560,000) grant from the Woodland Trust’s Emergency Tree Fund. Trees will be planted on vacant land, at former coal-mining sites, and along city streets and parks to help cool these neighborhoods. Organizers are calling on their communities to identify new sites or areas where trees have been lost and to participate in planting.

Glasgow Live, The Guardian

4. Israel

Israel has become the first country to ban the sale of fur in the fashion industry. Hailed as a historic milestone by animal rights groups, the amendment was signed into law in June and takes effect in December. “Using the skin and fur of wildlife for the fashion industry is immoral and is certainly unnecessary,” said Gila Gamliel, the environmental protection minister at the time, in a statement. “Signing these regulations will make the Israeli fashion market more environmentally friendly and far kinder to animals.”

Other governments have taken action to limit the fur industry. The United Kingdom became the first nation to ban fur farming in 2003, with many European countries following suit, though the sale of imported furs is still legal. In 2019, California banned fashion fur sales with some exceptions. Israel will allow the sale of fur for “scientific research, education or instruction, and for religious purposes or tradition.”

The Jerusalem Post, Jewish News Syndicate

5. Kenya

Rural counties in Kenya are improving sanitation by retrofitting latrines with safe toilets. A 2014 national survey found that 66% of rural Kenyans used either uncovered pit latrines or an open field or bush, a number that mirrors a worldwide estimate of some 6 out of 10 people for whom access to proper sanitation remains a challenge. Only 24% of Kenyan villages are certified as open defecation-free – a determinant of better sanitation. To improve hygiene, several counties are turning to SATO products, developed through nonprofit funding and supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The self-sealing plastic molds come in three varieties and can embed in a concrete base around any open latrine. They flush with just 1 to 4 cups of water, which opens a weighted flap at the bottom of the pan. SATO covers reduce odor, keep bugs from entering or exiting the pit, and improve safety for children and others using the bathroom at night. Distributed by community health volunteers, the toilets range in price from $6 to $12, plus the price of masonry for proper installation. Residents of Siayu County have purchased more than 60,000 SATO products to date, and the local director of health services says the county is working to install the toilets in early childhood development centers and health facilities.

Science Africa, Innovate4Health

World

For the first time, writers will be able to make money on used book sales thanks to a new collaboration between author organizations and online book retailers. Studies show the median income for full-time writers has been declining for years, and according to research from The Society of Authors, the pandemic has exacerbated the trend. Meanwhile, the used book market is growing.

A new program called AuthorSHARE seeks to address this disparity by ensuring writers receive royalties on the secondhand sale of their books at either World of Books or Bookbarn International. The retailers will track and share sales information with the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society, which has more than 112,000 members throughout 105 countries. The group will then match the sales with its member database and pay authors from a £200,000 ($280,000) royalty fund, which is expected to grow in future years. Author payments are currently capped at £1,000. “The value of a book goes beyond the value of the paper it is printed on, so it is great to see that original creators will see some benefit when their work finds a new reader,” said novelist Joanne Harris.

The Bookseller

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Systemic trust in buildings, pipelines, bridges

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On May 3, a bridge for a commuter train in Mexico City collapsed, killing 26 people. On May 7, cybercriminals seized physical control of the Colonial Pipeline, shutting down a large fuel supply in the eastern United States. And on June 24, a 12-story condominium tower in Surfside, Florida, collapsed with dozens of residents presumed dead.

These tragedies within just a few weeks of each other have renewed a focus on how to prevent failures of infrastructure. The solutions are not merely physical – stronger steel for bridges, for example. They also require a renewal of shared values that lie behind expectations of fail-safe structures in daily life.

“Trust is built not only in infrastructure but by humans,” said Anne Neuberger, deputy national security adviser for cyber and emerging technology in the Biden White House.

Shared physical structures require shared ethical standards, such as integrity and transparency, which are essential in delegating responsibility for today’s complex infrastructure. Trust-based cultures should expect to have fewer failures because both regulations and private behavior are rooted in shared values. Renewing those values can lead to better train bridges, secure pipelines, and stable condo buildings. The invisible matters more than the visible.

Systemic trust in buildings, pipelines, bridges

On May 3, a bridge for a commuter train in Mexico City collapsed, killing 26 people. On May 7, cybercriminals seized physical control of the Colonial Pipeline, shutting down a large fuel supply in the eastern United States. And on June 24, a 12-story condominium tower in Surfside, Florida, collapsed with dozens of residents presumed dead.

These tragedies within just a few weeks of each other have renewed a focus on how to prevent failures of infrastructure, whether public or private, whether a transport grid or a digital choke point. The solutions are not merely physical – stronger steel for bridges, for example, or more secure computer networks. They also require a renewal of shared values that lie behind expectations of fail-safe structures in daily life.

“Trust is built not only in infrastructure but by humans,” said Anne Neuberger, deputy national security adviser for cyber and emerging technology in the Biden White House. In responding to the Colonial Pipeline shutdown, for example, she helped bring together public and private actors to find a common understanding on resilience in critical infrastructure. “We learned a great deal about the need to have standards for the security between, for example, the part of a company’s network that connects to the internet and a part of a company’s network that runs their operations,” she said.

Shared physical structures, in other words, require shared ethical standards, such as integrity and transparency, which are essential in delegating responsibility for today’s complex infrastructure and in reducing the risk of failure.

A similar process is now underway after the collapse of the Champlain Towers South condos.

Miami-Dade County has started an audit of older residential buildings. In Boca Raton, Mayor Scott Singer has reached out to condo associations to ensure the boards are using best practices to keep buildings safe. Nationwide, the Community Associations Institute, which advocates for homeowners associations, is focusing on a proposal that would require such groups to use expert advice in setting aside reserve funds for basic repairs of older buildings. (More than 73 million Americans live in community associations.) Such steps are necessary for creating systemic trust in, say, a city’s building codes or legal requirements that a condo buyer is given information on future repairs of a building.

Trust-based societies, according to scholar Francis Fukuyama, share “a set of moral values in such a way as to create regular expectations of regular and honest behavior.” One good example is the small Baltic state of Estonia. After suffering a massive cyberattack from Russia in 2007, it has built up civic resiliency in its citizens to safeguard infrastructure. Whether it is trains, cars, electricity, or digital networks, says Estonian President Kersti Kaljulaid, society needs to have trust “because we have standards which we can trust.”

In approving a new law in June that will set up a biometric identification system for Estonia, the president spoke about the basis for trusting such a system to work and not cause harm. “What are the principles on the basis of which we’re shaping our state?” she asked. “What are the rights and freedoms of our people and in which cases does the public good outweigh individual freedoms? All these issues are relevant in the case of this law.”

Trust-based cultures should expect to have fewer infrastructure failures because both regulations and private behavior are rooted in shared values. Renewing those values can lead to better train bridges, secure pipelines, and stable condo buildings. The invisible matters more than the visible.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A spiritual basis for fatherhood

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Sandy Sandberg

A longtime father shares how getting to know God as the divine Parent of everyone can empower one’s efforts to nurture, care for, and protect others, including one’s own children.

A spiritual basis for fatherhood

Undoubtedly, the most basic definition of “father” is a man who has begotten a child. But after 50 years with two sons of my own, I can say that this purely biological definition by no means approaches what it means to be a father.

There are so many other qualities of fatherhood – among the most significant are nurturing, caring, protecting, guiding, and loving. Christian Science reveals these qualities as originating not in ourselves, but in the one divine Father of us all, God, and boundlessly reflected in each of us. And it’s this spiritual fact that I have worked at demonstrating in my own life, to be the best dad I can be to my sons.

God, Spirit, is at every moment caring for, protecting, and expressing love in all of us, His spiritual offspring. In her seminal work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy writes: “In Science man is the offspring of Spirit. The beautiful, good, and pure constitute his ancestry. His origin is not, like that of mortals, in brute instinct, nor does he pass through material conditions prior to reaching intelligence. Spirit is his primitive and ultimate source of being; God is his Father, and Life is the law of his being” (p. 63).

For sure, praying from this basis helped me in supporting my own children’s potential, from their first steps to their first jobs; in being there for them when the going was tough; in encouraging them when things didn’t work out as hoped; in finding healing and comfort when they were sick or in trouble. Deeply cherishing and holding to the spiritual fact that God, divine Life itself, is our Father proved comforting, even life-saving, when each of my sons went through a life-threatening experience.

For instance, there was the time my college-age son called me from his cell phone early one morning with fear and panic in his voice, asking me to pray. He and a friend were taking a boat across Cape Cod Bay, and he explained that they were encountering strong headwinds and high waves that were threatening to swamp the boat. Then my son’s phone cut out and we couldn’t reconnect.

As I reached out to God in prayer, the initial feeling of utter helplessness was almost immediately replaced with a quiet assurance. I held on to the spiritual fact that my son and his friend truly dwelled in infinite Life, and could never be separated from this divine presence. God is always with us, always protecting us, because that’s what our heavenly Father does. I felt this reassurance deep in my heart, and trusted it.

Several hours later my son was able to call again. He thanked me for the prayers, and told me they’d been able to get the boat turned around and safely back to land. It was so gratifying to watch the power of infinite Spirit bring them safely through.

And fatherhood isn’t a role that stopped when my sons left home and started families of their own. It’s a role that has actually grown in significance to me as the years have gone by.

In fact, I’ve realized, it’s not even restricted to one’s own children. The more I’ve sought to understand God as my Father, I’ve come to realize God is the truest Father of us all. We can express divinely inspired fathering qualities toward virtually anyone in our path. The more I’ve studied and practiced Christian Science, the more I’ve discovered the capacity to express the nurturing care, intuitive wisdom, and understanding love that promote the very best in others. It’s led to relationships with people who have become like sons and daughters to me.

Much more could be shared about what it means to have gained a more spiritual sense of God’s fatherhood and its power to touch virtually every corner of our lives. As we look to God’s parenting – teaching us, nurturing us, comforting us, and in every sense of the word loving us – we realize more deeply what it truly means to be a father.

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Explore other recent content from the Monitor's daily Christian Science Perspective column.

A message of love

Ahhh ... relief!

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Harry Bruinius shares a portrait of the humanity he has seen reporting in Surfside, Florida, the community hit by the condominium collapse last week.