- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- What helps Haiti? ‘Working with’ versus ‘Doing for.’

- Gender-based murder stats differ starkly in France and Spain. Why?

- Gen Z writes its own rules for financial security

- For this performer, when all else fails? Reinvent yourself.

- ‘Roadrunner’ brings Chef Bourdain – and his wanderlust – to the big screen

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Inflation is up. Will confidence in a stable economy go down?

It’s an old ploy for inflationary times. When costs go up, don’t boost the price, shrink the package. It happened back in the 1970s when inflation seemed out of control. And it’s happening again.

An NPR story details how boxes of Cocoa Puffs and Cheerios are getting lighter – 18.1 ounces, down from 19.3 ounces – but the price is staying the same. When a colleague posted the story on an internal chat space, Monitor staffers had their own stories of “shrinkflation” over the years: Triscuits, orange juice, and Pepperidge Farm cookies. It’s not just food of course. Prices are rising across the board.

American consumers are starting to notice. Inflation in June surged 5.4% from a year earlier, the biggest rise in 13 years. Takeout food and energy prices, which jump around a lot, and so-called core inflation rose at a rate not seen in 30 years.

Inflation is becoming a top-of-mind public concern, some polls suggest. That raises what may be an important question of balance in the world’s largest economy. Federal Reserve policymakers have thought a bit more inflation is tolerable now because the economy spent a dozen years undershooting their target of about 2% a year. But public worries can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If people lose confidence in monetary stability, they will act in a way that reinforces inflation.

The 1970s are talking to us. From a cereal box.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Essay

What helps Haiti? ‘Working with’ versus ‘Doing for.’

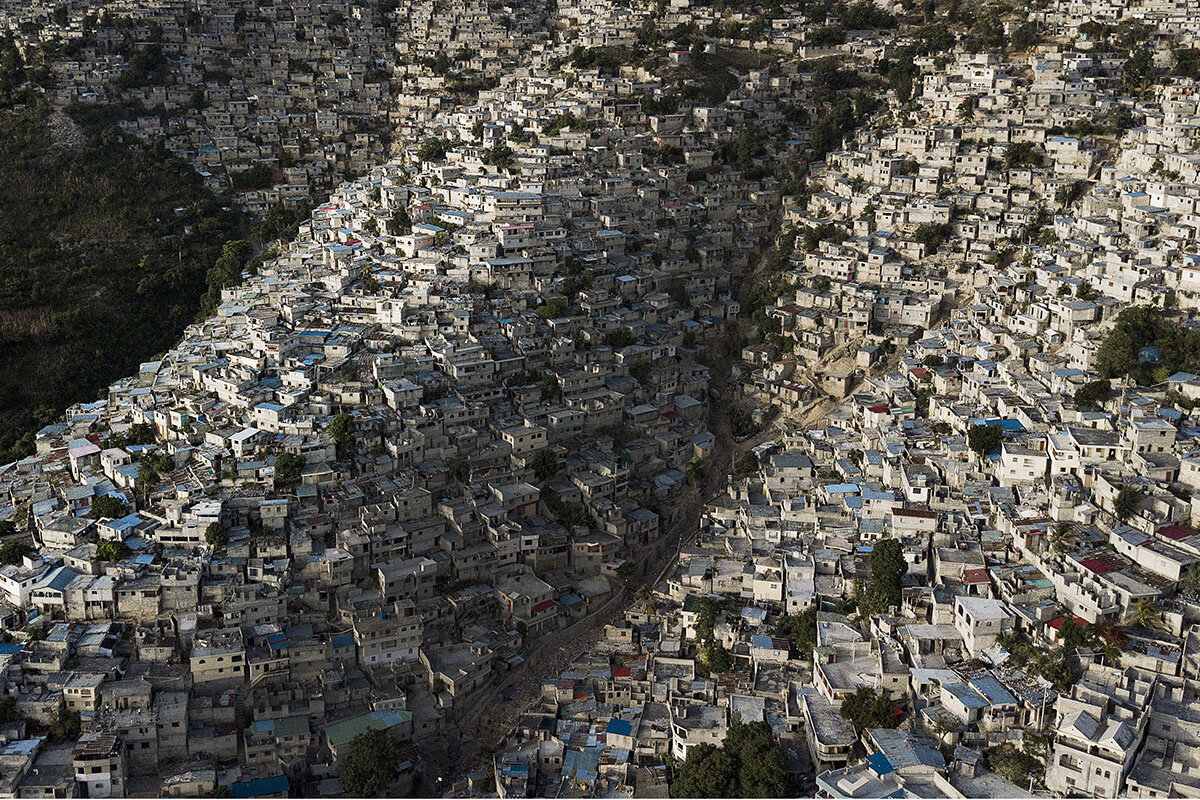

Have billions in aid left Haiti worse off? Some who know the country say when top-down assistance has been replaced with cooperation plumbing Haitians’ resilience and ingenuity, conditions have improved.

The motivations behind the assassination of Haiti’s president remain murky. But many Haitians say the corruption that intensified as billions of dollars coursed through the country after a devastating earthquake more than a decade ago was almost certainly a factor behind his demise.

Yet at the same time, Haiti specialists say lessons have been learned about foreign assistance. Perhaps the first among them is that Haitians' ingenuity and local knowledge are more helpful than top-down aid designed to serve a donor nation's interests.

“I compare the kind of aid that generally came into Haiti after the earthquake to a series of 'aftershocks’ that further hollowed out services and ministries, increased corruption, deteriorated security, and paradoxically even increased violence against women,” says Mark Schuller, a Haiti expert at the University of Northern Illinois.

“But that is not the full story,” adds Professor Schuller, the author of a 2012 study that chronicles how official development aid and NGO work has often undermined Haiti’s progress. “When the humanitarian impulse to do for has been replaced with a focus on working with,” he says, “and when the approach is one that emphasizes coordination and cooperation with Haitians, it has demonstrated that it can work.”

What helps Haiti? ‘Working with’ versus ‘Doing for.’

As Jeanne-Baptiste Vania stirred a huge bubbling pot of spaghetti in fish stock at her plot in a burgeoning homeless encampment in Port-au-Prince, she was already thinking beyond her own plight.

It was January 2010, and just days earlier the matriarch of a family of 17 had lost her home in the Haitian capital in a devastating earthquake that had gut-punched the Caribbean island nation when it was already down: The poorest country in the Western Hemisphere was long considered a failed state.

In a matter of seconds, as many as 2 million Haitians were displaced, and several millions more were left without essential services or a source of income.

But here was Ms. Vania in the homeless encampment that, before the earthquake, had been the private gardens of the prime minister’s residence. As she spiced her soup, she was set on not just feeding her own family, but imagining how she could ramp up to help nourish “many more desperate souls,” as she called the shellshocked humanity around her.

In the days since the July 7 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, I’ve thought of Ms. Vania, and the many resilient and determined Haitians I’d met covering the earthquake’s aftermath.

The assassination spawned many stories and much analysis of the decade since the earthquake, with the widespread conclusion that an outpouring of some $13.34 billion in international aid between 2010 and 2020 has left Haiti no better, and probably worse off, than before the horrendous temblor.

The motivations (and actors) behind the Moïse assassination remain murky. But many Haitians say the corruption that intensified as billions of dollars coursed through the country, and the way the earthquake assistance further concentrated power among a few antagonistic elites, were almost certainly factors behind the president’s violent demise.

Yet at the same time, Haiti specialists who are no Pollyannas say that while they agree that much of the foreign assistance has worked in insidious ways to make things worse, they also see where key advancements have been made.

Lessons have been learned, they say. Perhaps the first among them is that when top-down is replaced with “tap into,” conditions improved. In other words, international assistance was more effective when designed to cooperate with Haitians and plumb their ingenuity, know-how, and familiarity with the terrain than when provided from on high and designed to serve the donor nation’s interests.

Thinking back to Ms. Vania: If, instead of just feeding her and her big family, foreign aid agencies and nongovernmental organizations tapped into her resilience, desire to serve, and local knowledge, the mountains of aid had a better chance of actually doing good.

“I compare the kind of aid that generally came into Haiti after the earthquake to a series of ‘aftershocks’ that further hollowed out services and ministries, increased corruption, deteriorated security, and paradoxically even increased violence against women,” says Mark Schuller, an anthropologist and noted Haiti expert at the University of Northern Illinois who is also president of the international Haitian Studies Association.

“But that is not the full story,” adds the author of “Killing With Kindness,” a 2012 study that chronicles how official development aid and NGO work have often undermined Haiti’s progress.

“When the humanitarian impulse to do for has been replaced with a focus on working with,” Professor Schuller says, “and when the approach is one that emphasizes coordination and cooperation with Haitians, it has demonstrated that it can work.”

As examples of this kind of success, he cites the Spanish government aid agency working closely with local utilities and health activists to provide water and sanitation to large camps for displaced persons and to the capital’s Cite Soleil slum; and USAID collaboration with local health agencies and advocates to address the HIV/AIDS crisis and bring down infection rates.

Many experts underscore how it’s not just that foreign governments have deepened Haiti’s woes with top-down intervention, but that many large international NGOs took a similar approach that undervalued local expertise and contributed to deterioration of the Haitian state.

Studies revealed, for example, that only 1% of post-earthquake foreign assistance went to ministries or agencies of the Haitian government – while 99% went to NGOs. While some key ministries such as health were indeed initially knocked out of service by the earthquake, the heavy reliance on international NGOs only exacerbated Haiti’s deinstitutionalization, experts say.

“People can’t understand how Haiti deteriorated to such disastrous conditions, but it’s important to realize that the way foreign actors have interacted with Haiti has really lacked basic humanization,” says Ellie Happel, director of the Haiti Project and adjunct professor at New York University’s Global Justice Clinic.

What the last decade has taught some organizations is that foreign involvement ultimately only is a factor of progress if the guiding principle is collaboration, not “top-down, one-way streets,” she says.

In the Global Justice Clinic’s work with Haitian rights advocates supporting workers in the emerging mining industry, for example, Professor Happel says, “We start from the basis that the people closest to the problem are best placed to come up with the solutions."

Many Haiti specialists say the U.S. focus on working with Haiti’s ruling elites – supporting and propping up Mr. Moïse even as he turned increasingly dictatorial in the two years before his death and relied on the country’s violent gangs to stay in power – has further weakened Haiti.

Professor Schuller has little positive to say about U.S. assistance to Haiti, noting that first and foremost it is aimed at promoting U.S. foreign policy interests: for example, he says, providing quick fixes that stabilize the population and avoid a mass migration by Haitians to America’s shores, but doing little to address Haiti’s long-term needs.

And many critics say the United States is compounding past mistakes by insisting Haiti move to elections before the end of the year to fill the political power vacuum left by Mr. Moïse’s assassination.

“Free and fair elections are just not possible in Haiti today, and the U.S. doubling down on elections is only going to perpetuate the problems that accumulated under Moïse,” says Professor Happel, who lived in Haiti for six years.

At a congressional hearing last year, she testified that three main factors make rushed elections more of a problem than a solution: insecurity and heightened gang control in recent years, an incomplete voter ID system rollout, and widespread distrust of election legitimacy.

Many Haitians and experts on the ground say elections anytime soon make little sense and could actually increase already high levels of violence, given several factors: the government’s branches are emptied, and there are deep divisions over how to fill them; before his death, Mr. Moïse had been ruling by decree; there is no functioning parliament; and the president of the Supreme Court died last month after being diagnosed with COVID-19.

Instead, many in Haiti’s civil society are calling for the creation of a transitional government to focus on immediate humanitarian needs and stabilizing Haitian society before holding national elections.

And Professor Happel advocates listening to the nascent Commission for a Haitian Solution, a group of more than 100 civil society, religious, and labor organizations calling for Haitian society to focus first on inclusive national dialogue aimed at finding solutions to the country’s big problems.

“It would be a real effort at consensus building,” she says, “bringing in all of Haiti’s actors and based on that idea that those closest to the problems are best suited to come up with the solutions.”

Gender-based murder stats differ starkly in France and Spain. Why?

Spain and France, two European neighbors, have both tried to tackle gender-based violence to varying degrees of success. The results show that there’s no one-size-fits-all strategy to confronting the issue.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Spain is one of the leaders in tackling gender-based violence, particularly by reducing gender-based murders over the past decade. But where Spain has succeeded, neighboring France has struggled.

Since the beginning of the year, France has counted 58 femicides, or murders of women based on their gender, one of the highest tallies in Western Europe. The stark difference in statistics – Spain has recorded 24 femicides so far this year, according to the government – is waking up French officials and activists to what needs to be done to respond to domestic violence calls, and what France might learn from its Iberian neighbor.

Training and raising awareness have been integral to Spain’s success and feature heavily in its law, which encourages educational institutions to train people of all ages on not just what domestic abuse is, but on values like respect, tolerance, and equality.

“In Spain, they’ve developed a complete system, from education to protection to legal punishment,” says Fatima Benomar of women’s rights group Les Effronté-es. “In France, the majority of cases are thrown out. Not enough people are educated about domestic violence from early on. But ... we’re starting to talk about it more and more.”

Gender-based murder stats differ starkly in France and Spain. Why?

Ana Bella Estévez had survived years of verbal, physical, and mental abuse at the hands of her husband when one night, he asked her to sign a document that said she wouldn’t divorce him even if he continued to hit her. That was when everything changed for her.

“I went to a center for women’s information just to see if I could get out of my marriage. A woman asked me questions like does your husband yell at you? Yes. Does he throw things at you? Yes,” says Ms. Estévez. “It’s incredible, surrealistic, but until then I never realized I was a victim of domestic violence.”

Ms. Estévez drove to a shelter in nearby Sevilla with her four children and never looked back. Now, 20 years later, she is fighting against domestic violence in Spain with her Fundación Ana Bella, a women’s network of 16,000 members around the world that connects survivors with those undergoing abuse. Her organization and others, alongside government initiatives, have helped make Spain one of the leaders in tackling gender-based violence, particularly by reducing gender-based murders over the past decade.

But where Spain has succeeded in decreasing gender-based murders, neighboring France has struggled. Since the beginning of the year, the country has counted 58 femicides, or murders of women based on their gender, one of the highest tallies in Western Europe. The stark difference in statistics – Spain has recorded 24 femicides so far this year, according to the government – is waking up French officials and activists to what needs to be done to respond to domestic violence calls, and what France might learn from its Iberian neighbor.

“In Spain, they’ve developed a complete system, from education to protection to legal punishment,” says Fatima Benomar, co-founder of French feminist group Les Effronté-es, which works to advance women’s rights. “In France, the majority of cases are thrown out. Not enough people are educated about domestic violence from early on. But at least the issue is no longer buried in the middle of the newspaper now. We’re starting to talk about it more and more.”

Different paths

Spain’s wake-up call to domestic violence came in 1997 when Ana Orantes, an Andalusian woman in her 60s, appeared on television to denounce the violence she’d endured at the hands of her husband for 40 years. Two weeks later, she was found murdered in her garden – set on fire by her husband.

The case shocked the nation, and in 2004, Spain adopted a comprehensive law on intimate partner violence that implemented a range of measures involving cooperation between law enforcement, health services, and legal counsel. It also created a special court dedicated to fast-track cases of domestic violence. It has helped bring down the number of women killed annually by their partners or ex-partners from a peak of 76 in 2007 to 45 in 2020.

But neighboring France has seen its own numbers stagnate over the same period – 166 women were killed by their partners in 2012 and 146 in 2019. That prompted the government to hold a national forum on domestic violence at the end of 2019, which led to a series of measures including electronic bracelets to alert women when abusers are nearby and expulsion orders to force violent partners out of the home.

Last month, France’s gender and equality minister announced extended operating hours for its national domestic abuse hotline, and the creation of 12 holding centers for abusers.

Government efforts have started to pay off – last year, femicide numbers in France dropped to 90. At the end of June, Frenchwoman Valérie Bacot was freed from police custody after facing life imprisonment for murdering the ex-husband who had sexually abused her for decades. But experts say a disconnect remains between the legal structures in place and what happens in practice.

“It’s still extremely difficult for cases to make it beyond a first police complaint. Around 80% of cases are thrown out,” says Janine Bonaggiunta, a lawyer in Paris who specializes in domestic violence. “Even when cases are accepted, there is so much paperwork and the wait time is interminable. It can be very discouraging for clients.”

Judges want to see medical certificates of abuse, which can be difficult to obtain for women who see the same general practitioner as their abusers. And French doctors tend to treat physical injuries without inquiring further about their possible causes, like abuse.

Police relearning how to respond to abuse

But the biggest hindrance to progress, say campaigners, is at police stations, where officers lack training in how to respond to domestic abuse survivors.

“Police have a stereotype of what a victim of abuse looks like,” says Ms. Benomar of Les Effronté-es. “Unless a woman comes in with a black eye and three teeth missing, they don’t give credibility to what she says.”

The Yvelines police department in the Paris region is hoping to change its handling of domestic violence complaints. It has created a QR code that can be discreetly distributed to sufferers of abuse during routine police interventions. It’s working on creating alternative welcome desks where people can report abuse confidentially. And every new officer who enters the department is required to undergo domestic violence training, which includes learning how to identify what PTSD looks like.

“For a long time we didn’t understand how to identify trauma or the cycle of violence, why a victim can’t remember what happened to her, or why she returns to her aggressor days after making a complaint,” says Maj. Fabienne Boulard, who has been leading the Yvelines trainings for a decade. “After the training, many officers tell me they probably didn’t act correctly during past interventions. So we’re starting to change our ways little by little.”

“Gender-based violence is a man’s problem”

Training and raising awareness have been integral to Spain’s success and feature heavily in its 2004 law, which encourages educational institutions to train people of all ages on not just what domestic abuse is, but on values like respect, tolerance, and equality.

That includes making men part of the equation, says the Men’s Gender Equality Association (AHIGE), a Spanish feminist organization led by men that goes to schools, workplaces, and health services to train men on positive masculinity.

“Gender-based violence is a man’s problem, in that it’s men who harass and kill women, and benefit from gender inequality,” says Miguel Lázaro, an activist with AHIGE in Madrid. “We’ve been taught as men that if we talk about our feelings, it’s not manly. We try to challenge those ideas and encourage men to make emotional development. ... We need to hold ourselves accountable.”

Despite their efforts, the issue remains a work in progress. Spain has seen a spike in femicides since its pandemic state of emergency was lifted in May. Activists hope the country’s strong combination of prevention and legal structures will get violence back under control. Ms. Estévez, with her Fundación Ana Bella, is doubling down on efforts to educate school-age children about abuse, and provide survivors with shelter, support, and jobs training.

“If you can overcome abuse, it means you are strong and resilient, you’re able to work under pressure, you’re perseverant,” she says. “We want to help women transform the pain they’ve experienced into empathy and expertise ... so they can become change-makers themselves.”

Gen Z writes its own rules for financial security

As millennials play financial catch-up – a struggle that we explored yesterday – the newest generation of young workers also faces economic instability. Here’s how Gen Z is upending traditional paths to security and paving new roads to justice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

America’s Gen Z – born after 1995 – now makes up 20% of the population and a fast-rising share of the workforce. These young people are emerging from school and into adulthood with $115.5 billion in student debt, and a cost of living that outpaces wages in many areas, on the heels of a pandemic that brought economic insecurities into sharp focus.

But many Gen Zers are determined to establish financial stability – and they’re doing it on their own terms, with a strong commitment to social justice. This twin focus on financial security and a change-the-world mission may be, in part, the logical outcome of current uncertainties – whether Social Security benefits will endure or whether projections of a lean era ahead for stock market returns will come true.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a group of young people is developing a youth economic bill of rights to build a more inclusive playing field. They are part of an organization called MyPath, which supports low-income young adults, and especially people of color, on paths of economic mobility and wealth creation.

“They just need a seat at the table,” says MyPath CEO Margaret Libby, “so they can be part of defining what the needs are – and what the right solutions are.”

Gen Z writes its own rules for financial security

Lian Zhang is only 22, but she’s already nervous about how she’s going to afford a house or her future children’s college education.

Ms. Zhang did everything “right.” Growing up in a low-income immigrant family on the outskirts of Los Angeles, she was able to graduate from a four-year college last year, thanks to hard work and federal aid. Her dream was to help other underserved students navigate the education system.

“I want to serve lower-income communities or marginalized groups,” says Ms. Zhang, who works as an admissions counselor at an online university earning $43,000 a year. But she also hopes to support her own family, including buying a house for her mother. She worries that a middle-class salary won’t be enough. “Maybe it’s better that I make more money now and retire early or save up so that I can donate or help that group later on, when I’m more well-off.”

Ms. Zhang is part of Generation Z. These young Americans, born after 1995 and dubbed “Zoomers” during the pandemic, now make up 20% of the population and a fast-rising share of the workforce. They are the most racially diverse generation yet, and are generally known for their viral TikToks and hypersensitivity to social causes.

This generation is reaching adulthood with no shortage of difficult financial decisions and challenges on its plate. Having observed the Great Recession as children and now being young adults of the pandemic, Gen Zers understand financial stress. Many entered the workforce at a time of layoffs and pay cuts and vanishing jobs, and a high number have experienced poverty. Yet amid the financial insecurity, this generation is responding with a blend of hardheaded pragmatism and nontraditional efforts to make economic opportunity more inclusive.

“What [young] people are saying is, ‘Hey, this pandemic almost killed me. So I want to really think about what’s valuable ... and what’s important in life,’” says economist William Cunningham, who believes the current moment is proving to be a time of societal recalibration. “You can’t catch up. So what that means is that you’ve got to change the parameters, the environment, which you’re in.”

Stock market strategies

The job market is on the mend in comparison with the height of the pandemic a year ago – employers added 850,000 jobs in June alone. But the roots of financial anxiety among young adults may have sprouted long before the pandemic.

Gen Zers have seen the generation before them, millennials, struggle to pay back student debt, often delaying homeownership. Gen Z already holds $115.5 billion in student debt, and the cost of living continues to outpace wages in many urban areas. In 2020, some 30% of Gen Zers already had credit card debt. Not surprisingly, money is a “source of significant stress” for 81% of Gen Z survey respondents between the ages of 18 and 21, according to a study conducted by the American Psychological Association.

Rising costs of housing, health care, education, and child care have compelled these young people to pursue high-paying jobs in finance, business, and technology.

“What we’ve noticed is that Gen Z seems to take a much more functional, rational approach to their money overall, even with being younger,” says Kelly Lannan, vice president of young investors at Fidelity. “A lot of folks within Gen Z want to actually learn from the generation before them,” she says. “They are a bit more risk-averse.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has only solidified these patterns. Half of the oldest Gen Zers said they or another household member lost a job or took a pay cut as the pandemic began, according to a Pew Research survey from March 2020. That came as poverty rates were already higher among adults aged 18 to 24 – around 1 in 5 young adults – than for most other age groups, as individuals move out of their parents’ homes, earn low wages, and are less eligible for public benefits.

For a growing number of young Americans, investing early is a way to quell financial anxiety.

“[Investing] definitely seems beneficial,” says Bowen Popkin, a recent high school graduate from Massachusetts who started dabbling in the stock market during the pandemic. “In Finland, you can be poor and happy. Here, not so much,” he says. “That inspired me to build personal wealth and just take it upon myself.”

User-friendly apps such as Robinhood are making it easier for Gen Zers to try their hand at investing, and young people are turning to YouTube and Reddit to educate themselves in financial strategies. One survey found that 22% of Gen Zers began investing before they turned 18, as compared with only 8% of millennials. And the decentralized appeal of cryptocurrency and the GameStop saga earlier this year have pulled even more young investors into the fold.

Social impact investing

For many Gen Zers, investing is more than just a way to secure financial stability. Beyond profit alone, young adults are investing with specific values in mind: inclusion and social impact.

“When they have a little bit of freedom and disposable income to decide where to spend their money, it’s going to be in a way that doesn’t always maximize material return,” says Josh Packard, executive director of Springtide Research Institute. Instead, he says, they will spend “in a way that signals alignment with who they are and what they want to be in the world.”

The rise of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Dogecoin may actually be evidence of this generation’s eagerness to seek out innovative solutions to problems it is facing, such as distrust of financial institutions. By putting trust in a decentralized community of cryptocurrency, young adults have created an entire financial system that doesn’t depend on the whims of big banks, says Dr. Packard.

“We’re not necessarily investing like my parents were for the biggest return so that they could be financially comfortable,” says Vivek Pandit, a 23-year-old who works at a startup in Philadelphia that helps companies recruit underrepresented talent.

“That is a priority for us, but we’re investing with a mission. When we used Robinhood, it was to prop up GameStop and take down the hedge funds. When we’re investing in crypto, it’s to prove that this whole decentralized idea of currency can actually work.”

This twin focus on financial security and a change-the-world mission may be, in part, the logical outcome of current uncertainties – whether Social Security benefits will endure or whether projections of a lean era ahead for stock market returns will come true.

For many young people, social impact investing – not mere profit – is the future of the financial system. This shift isn’t taking place just because it’s the “moral” thing to do, says Mr. Pandit, but because social impact is the only business strategy that makes sense.

“Generation Z is the most ethnically diverse generation ever, and by the time we’re the mass consumers in the marketplace, companies that don’t look like us won’t know how to cater to us, and we’re not going to buy from them,” he says, referring to companies’ commitments to diversity and the environment.

Financial inclusion

In addition to investing and consuming more consciously, some Gen Zers are organizing to demand new rules for the economic game.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a group of young people from low-income backgrounds is developing a youth economic bill of rights to build a fairer, more inclusive playing field.

They are part of an organization called MyPath, which supports low-income young adults, and especially people of color, on paths of economic mobility and wealth creation. “We haven’t, as a country, really been as thoughtful as we could be about investing in this 16- to 24-year-old population,” says Margaret Libby, founder and CEO of the nonprofit.

Most of the young people the organization serves are simply trying to establish themselves in the workforce, navigate banking, and build up wealth from nothing – often on salaries that barely cover the bills. Even so, they aren’t focused only on themselves.

The youth economic bill of rights includes banking access, quality financial education, financial coaches, affordable higher education, a guaranteed income, and the right to participate in policymaking.

“They just need a seat at the table,” says Ms. Libby, “so they can be part of defining what the needs are – and what the right solutions are.”

Listen

For this performer, when all else fails? Reinvent yourself.

Christine Hudman Pardy had achieved the artist’s dream: a passion-filled career and financial stability. But when the pandemic hit and she lost it all, she turned inward to face her external circumstances. Episode 2 of our podcast “Stronger.”

Las Vegas prides itself on being the entertainment capital of the world. For performer Christine Hudman Pardy, this was the type of place where she could embrace her dream. As the lead female vocalist for “Le Reve,” a premier show at the Wynn Las Vegas, she provided an experience of escape and wonder to a global audience.

“You have these insane, chaotic days and then you come into the theater, and you’re still,” Ms. Hudman Pardy says. “And we get to take you on this magical ride for a couple of hours. And you leave changed.”

All that came to a halt in March 2020 when her show closed. Her husband, a drummer on Broadway, also lost his job. The two have been almost entirely without work for more than a year, surviving on savings and unemployment, trying to navigate pandemic life with their three teenagers. For Ms. Hudman Pardy, losing her dream job was made even more painful because of what came with it: a loss of her sense of self and artistic expression.

And yet even as she wrestles with the challenges of the year, her drive to grow pushes her to reinvent herself yet again.

“‘Le Reve’ was such a highlight of my career. But what do you do when the show closes?” she says. “There’s a reckoning within you. There has to be. What is the next dream? It’s not done for me.” – Jessica Mendoza and Samantha Laine Perfas

This story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears (audio player below), but we understand that is not an option for everybody. A transcript is available here.

The Artist

Film

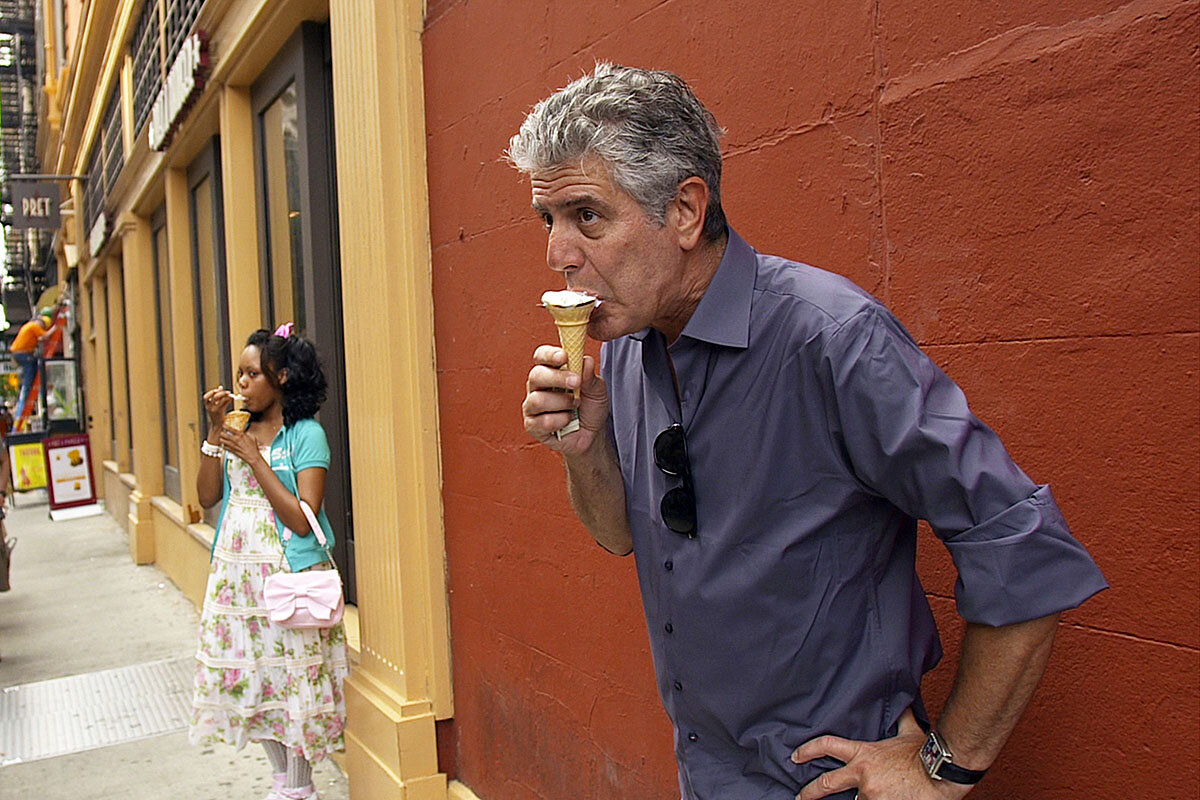

‘Roadrunner’ brings Chef Bourdain – and his wanderlust – to the big screen

Anthony Bourdain helped others see the world as he did. What motivated him? A new film sheds light on the late chef, who brought the public on all manner of adventures with his popular books and TV shows.

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

‘Roadrunner’ brings Chef Bourdain – and his wanderlust – to the big screen

The subject of the new Morgan Neville documentary, “Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain,” was a singular character for our time: A celebrity chef and author, Anthony Bourdain became the globally renowned host of television shows, such as “A Cook’s Tour” and “Parts Unknown,” that focused on all manner of cuisine and travel. He was fearless in his tastes: Eating a cobra heart in a Saigon cafe was all in a day’s work.

Visiting practically every corner of the planet, logging many hundreds of thousands of miles, Bourdain was an all-around adventurer, our surrogate gallivanter. Companionable yet edgy, he had the charisma of a movie star and seemed to enjoy his mission to the utmost. When he took his own life in 2018, the shock waves were profound.

Told mostly chronologically, “Roadrunner” gets going around 1999, when Bourdain – having served time as a dishwasher and line cook before becoming executive chef at a tony New York brasserie – wrote an unputdownable tell-all piece for The New Yorker that led to his runaway bestseller, “Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly.” By 2002 he was a fixture on TV, first for the Food Network, then the Travel Channel, and, finally, CNN.

Over time, the shows became less about what he ate and more about the world as he saw it – everywhere from Congo to the war zone of Beirut – in all its fathomless mystery and awe. The opposite of a typical tourist, he especially connected with the downtrodden, never condescending to them as “exotic.” He was an advocate for social justice. At one point in the film he says, “I’m not a journalist. I’m not an educator. If anything, I like going to a place, picking one thing, and being completely wrong about it.”

Neville (“20 Feet From Stardom,” “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?”) had access to over 100,000 hours of video of Bourdain, an avid and intimate chronicler of his exploits on and off camera. (His language in this R-rated movie is often saltier than his meals.) Added to this are extensive interviews with many of his friends and colleagues, and his two ex-wives.

As a result, the film has an almost voyeuristic comprehensiveness. There’s even a scene near the end with Bourdain seeing a psychiatrist. He was for a time, in his youth, addicted to heroin; he says he kicked the habit when he looked into the mirror and saw “someone worth saving.” But it’s clear from the footage and the filmed commentaries that he lived in a constant state of frenzied extremes. He rejected normalcy and yet he craved it. During his second marriage, when he became a father to a doting daughter, we see him grilling burgers in the backyard while professing that “I’m never happier than when I’m a TV dad.” And yet for most of his public career, he was willingly on the road for around 250 days a year.

The director is smart enough and scrupulous enough to avoid any amateur psychologizing in this film. He implicitly dispels the notion that Bourdain’s suicide was in any way something to be romanticized, or that it was the inevitable result of achieving his wildest dreams. Although Neville obviously had the cooperation of many in Bourdain’s inner circle, the film never feels authorized or hagiographic. He allows for Bourdain’s inner darkness.

Neville isn’t trying to “solve” Bourdain, and so, in his own way, he proves himself as open to the vast complexities of experience as his subject was. Bourdain was a larger-than-life figure who, for whatever manifold reasons, was finally pulled down by his own life. For me, his legacy lives on here in those moments when he gasps at the sight of some far-flung landscape or enters ardently into a street scene thronged with humanity. He looks like a man lit up by his own rapture.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain” is available in theaters on July 16. It will air on CNN and stream on HBO Max later in 2021. It is rated R for language throughout.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How voters shook up Europe’s most corrupt state

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A poll of 40,000 people in the European Union last month found a third say corruption has gotten worse over the previous year. That does not speak well for EU attempts over decades to instill honest governance in its 27 member states. Oddly enough, the bloc can now take heart from its poorest and most corrupt member, Bulgaria.

Over the past year, starting with mass protests last July, Bulgarians have voted in two elections not only to oust a longtime prime minister perceived as corrupt, but also to choose an anti-corruption party as the largest vote-getter and the expected leader of a new government.

Before his victory in last Sunday’s election, Slavi Trifonov, leader of the winning party “There Is Such a People,” said that civil society over the past year has expressed “in an unequivocal way its intolerance of brutal corruption at all levels of government.”

Bulgarians may have lagged in the EU fight against corruption, political scientist Andrei Raichev told Deutsche Welle, “but now they are fomenting the change.” The rest of Europe can take note.

How voters shook up Europe’s most corrupt state

A poll of 40,000 people in the European Union last month found a third say corruption has gotten worse over the previous year. That does not speak well for EU attempts over decades to instill honest governance in its 27 member states. Oddly enough, the bloc can now take heart from its poorest and most corrupt member, Bulgaria.

Over the past year, starting with mass protests last July, Bulgarians have voted in two elections to not only oust a longtime prime minister perceived as corrupt but also to choose an anti-corruption party as the largest vote-getter and the expected leader of a new government.

“This is a sign that corruption ... can no longer be tolerated,” Vessela Tcherneva of the European Council on Foreign Relations think tank told a Bulgarian television station.

Before his victory in last Sunday’s election, Slavi Trifonov, leader of the winning party “There Is Such a People,” said that civil society over the past year has expressed “in an unequivocal way its intolerance of brutal corruption at all levels of government.”

Mr. Trifonov, a popular talk-show host who has satirized corrupt leaders, promised total transparency in government. “It is time that everything happens right in front of your eyes, in parliament,” he wrote on Facebook. In coming days, he will try to form a ruling coalition in the 240-member chamber.

Bulgaria’s momentum against corruption gained speed in April after an election ousted Prime Minister Boyko Borisov. A caretaker government took over and quickly exposed favoritism in public procurement under Mr. Borisov. Then in June, the United States imposed sanctions on two Bulgarian oligarchs, a senior security official, and 64 companies. The U.S. described its move as “the single largest action targeting corruption to date” under the Magnitsky Act, a law that punishes foreign government officials implicated in corruption or human rights abuses.

But as Mr. Trifonov pointed out, “It is not the U.S. sanctions that will change our country, but the awakened civil society.” For the rest of Europe, that’s a useful reminder of where honest governance begins.

Bulgarians may have lagged in the EU fight against corruption, political scientist Andrei Raichev told Deutsche Welle, “but now they are fomenting the change.” The rest of Europe can take note.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Not just surviving but thriving!

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Schaefer

Have you ever thought about salvation as more than simply being protected or saved from harm, but as living in a fuller, more meaningful, God-inspired way?

Not just surviving but thriving!

Baking on the searing pavement under the Texas summer sun in the middle of a busy roadway was a red-eared slider turtle. Driving by, my husband saw it just in time, then safely stopped, scooped it up, and brought it home. We put it in our small patio pond, but after several days, the turtle hadn’t eaten, the shell was flaking off, its skin was peeling, and the outlook seemed dire.

So I prayed.

Of all the pressing concerns in the world, the situation with a turtle didn’t seem very consequential. Yet I’ve found that praying about the little things in life often ends up helping me see solutions to the bigger things. In this case, I learned something about the nature of salvation.

Salvation in its most basic sense means deliverance or preservation from harm, loss, or peril. As the world starts to emerge from a pandemic, there is a desire to get back to “business as usual.” Yet there’s also a longing to live life in a fuller, more meaningful way. We don’t want to just survive; we want to thrive.

The Bible offers a foundation for this more expansive view. It includes accounts of individuals who are not only delivered from impossible situations, but whose lives are also improved in the process. Characters are changed. Mistakes are rectified. Lives are healed. There’s a sense of being connected to something bigger than one’s self. A sense of being linked inseparably to the Divine, to God.

When I think of salvation in this fuller sense, I think of Christ Jesus. He healed sin and sickness and even overcame death. And yet, as wonderful and important as all this was in and of itself, Jesus taught that healing really points to something larger – a spiritual reality that he described as “the kingdom of God.” It’s a quality of life where God’s rule of harmony is supreme; and as citizens of this kingdom, we are spiritual, whole, and subject only to the government of divine and perfect Love, God.

Jesus spoke of this kingdom as “right at hand” and “within” each of us. Salvation, then, isn’t something that we have to wait for. The kingdom of God is already present within consciousness. We experience this kingdom more tangibly as we understand God better.

“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science and founder of The Christian Science Monitor, includes a glossary of spiritual definitions for biblical terms. It defines “salvation” as “Life, Truth, and Love understood and demonstrated as supreme over all; sin, sickness, and death destroyed” (p. 593).

Life, Truth, and Love are Bible-based names for God. They help us understand that God is not some mortal dispensing salvation as He sees fit. Instead, God is Life itself, expressing health, wholeness, and immortality throughout all creation. God is Truth, the basis for all that is true and right and good and pure. God is Love, expressing comfort and beauty and joy and overflowing love for each and every one of us.

The world can seem filled with violence, disease, injustice, and suffering. Yet Jesus turned perceptions of existence as matter-based upside down. Instead of judging things from the physical senses’ viewpoint, he started with God, Spirit. Whatever reflects the goodness of God, Truth, is the spiritual reality. And he called evil a lie and “the father of [lies]” (John 8:44). Jesus didn’t ignore bad things. He showed that for every threat of evil, including injury or illness, there is a spiritual fact that corrects and heals it.

This brings me back to my turtle story. I had been judging things by the material picture. It looked as if extended exposure to the sun had caused irreversible damage, but divine Love is the only legitimate power and cause throughout the entire universe. In my prayers, I considered these spiritual facts. It became clear to me that the physical picture had to be untrue when viewed from God’s perspective. Love is the eternal refuge for all.

That day the turtle began to eat and flourish. In fact, she recently outgrew our pond, and we found a bigger home for her nearby.

It’s a small example. But, like expanding ripples in a pond, our sense of salvation grows whenever we recognize and prove that the laws of God’s kingdom are fully in effect now. As I’ve opened my heart to this, I’ve experienced physical and mental healings and felt God’s saving presence over and over again.

That’s true salvation, in which we glimpse a larger sense of life – the Life that is Love, God, in whom everyone not only survives, but is guaranteed to thrive!

A message of love

Cuban solidarity

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. And we’ll see you again tomorrow, with a story on how Russians view Marvel’s latest blockbuster – which deals with former Soviet superheroes trying to reckon with their past.