- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A little shift in perspective

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

What do Russians think when they watch the new Marvel blockbuster “Black Widow”? That’s an obvious and a strange question. On one hand, it’s not something many media outlets are going to care about. On the other, the movie is, well, about Russians. Does any of it ring true?

In today’s issue, Fred Weir finds the answer is generally no. But in that answer, he offers a more nuanced view of Russians themselves, beyond the vodka-drinking, dastardly-KGB-agent stereotypes that maybe define not only Hollywood's portrayals, but also the wider West’s views of Russia.

Actually working with Russian actors and producers would be a start. Then, between the explosions, films like “Black Widow” could also offer a drop of authenticity and let Russians “see more accurate reflections of themselves and their country,” Fred says.

That idea of shifting our perspective runs through today’s issue. We know the tragedies of New York City during the pandemic. But Harry Bruinius finds that a different perspective yields new views. In the Bronx, one of the hardest-hit areas, those compiling an oral history found deep wells of resilience, too.

And Doug Struck tells the story of Valmeyer, Illinois – swept away by a 1993 flood but now born anew 2 miles away. What was destruction has become renewal and perhaps a model. When we shift the lens through which we see the world, we often see a different world, no less credible and with different and essential stories to tell.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

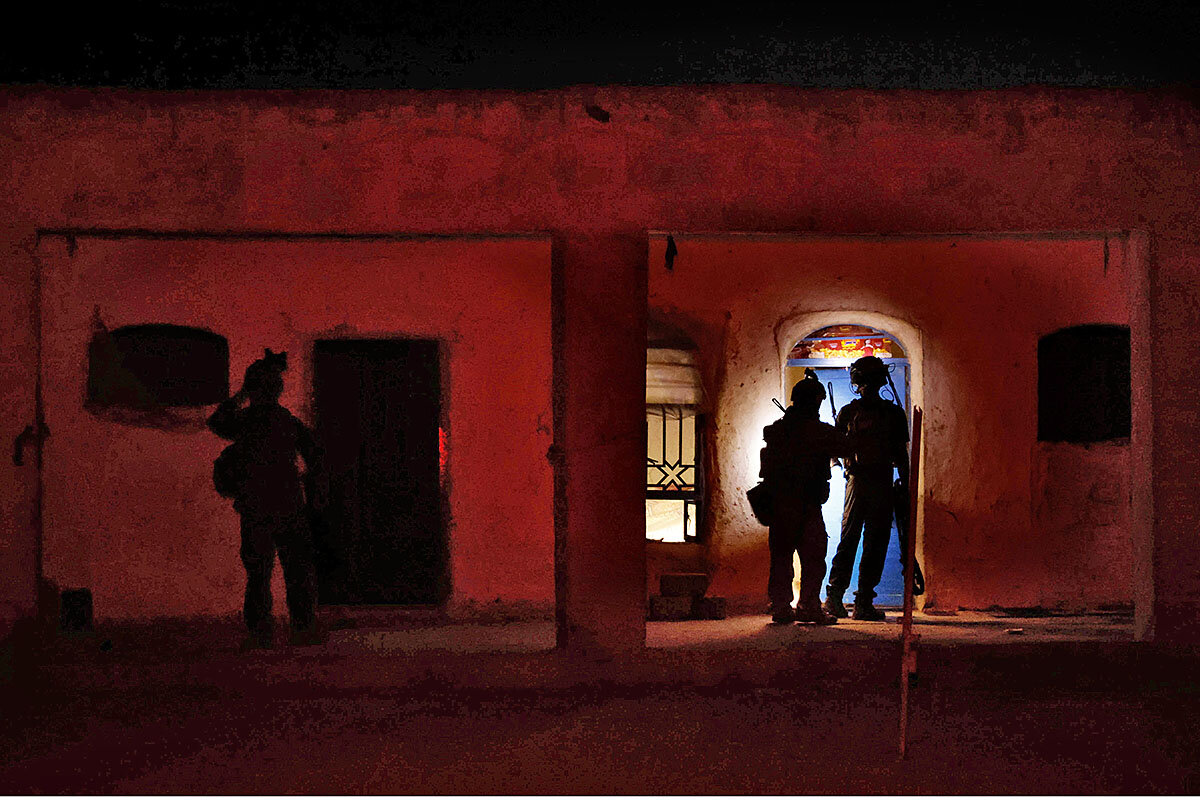

‘Back to the darkness’: Afghan women speak from Taliban territory

The Taliban have told the West they’ve changed their ways. But they’re not acting like it. Honestly taking stock of the Taliban is vital to one major Western success in Afghanistan: women’s rights.

-

Hidayatullah Noorzai Correspondent

From her roof, 18-year-old Khalida saw flames rising from her girls high school, with a new library full of books painstakingly collected by teachers. “The villagers tried to put out the fire,” she says, “but the Taliban shot at them and no one saved our school.”

In Afghanistan, a 20-year Western presence and tens of billions invested in rebuilding raised the expectations of many Afghans, especially women, of a freer future. And Taliban political leaders who negotiated with the United States had proclaimed a pragmatic evolution in their thinking since they imposed Islamist rule in the late 1990s.

Yet today, residents of areas that have fallen under Taliban control report little sign of reforms or accommodation by the jihadis. Instead, these residents confirm that the “old” Taliban is again seizing power.

“We thank the U.S. government for transforming our lives and giving us hope after the dark days of the Taliban; only in the last 20 years we realized that we are human beings and have the right to live,” says a women’s rights activist whose district fell to the Taliban a month ago.

“Unfortunately ... we are going back to the 1990s. It means we go back to the darkness.”

‘Back to the darkness’: Afghan women speak from Taliban territory

The Afghan student says she will never forget one of the Taliban’s first acts after seizing control of her district weeks ago, amid a military advance that has swiftly accelerated as American troops leave Afghanistan.

Late at night, Khalida was awakened by a deafening explosion. From her roof, the 18-year-old saw flames rising from her girls high school – her pride and joy, with a new library full of books painstakingly collected by teachers who traveled to gather them.

“I cried a lot. The villagers tried to put out the fire, but the Taliban shot at them and no one saved our school,” says Khalida, recalling an event that has become a regular feature of the Islamist militants’ conquests, as Afghan security forces collapse in district after district.

“In the morning, when I went to school, everything was burned and destroyed, even the school gates,” she says of the school built by Norway and the United States in northwestern Faryab province.

“When I saw the Taliban up close, I was very scared. They are wild people and they don’t respect women,” says the student, who gave only her first name and who planned to become a doctor. “No one is happy with the Taliban; everyone is sick of them. ... [But] no one is willing to stand up to the Taliban. [They] will kill you. They are very cruel.”

Top Taliban political leaders – who negotiated a withdrawal deal directly with the U.S. in 2019 and 2020, and then joined intra-Afghan peace talks last September – have proclaimed a pragmatic, moderate evolution in their thinking since the late 1990s, when their version of Islamist rule was marked by violence and strict enforcement of bans on girls’ education, women working outside the home, and even men shaving their beards.

Yet today, residents of areas that have fallen under Taliban control report little sign of change, reform, or inclusive accommodation by the jihadis of a society molded by 20 years of a Western presence and tens of billions spent on rebuilding. Those investments raised many Afghans’ expectations of a freer future.

Instead, these residents confirm it is the “old” Taliban – every bit as brutal, zealous, and vengeful as they were two decades ago – that are again seizing control, and through their oppressive actions providing a glimpse of the future under their archconservative sway.

The Taliban’s march across Afghanistan surged on multiple fronts since President Joe Biden vowed in April that U.S. and NATO troops would withdraw unconditionally, ending America’s longest-ever war. By Tuesday, the Taliban fully controlled 223 of Afghanistan’s roughly 400 districts, three times the number controlled by Afghan security forces, according to the Long War Journal.

“We thank the U.S. government for transforming our lives and giving us hope after the dark days of the Taliban; only in the last 20 years we realized that we are human beings and have the right to live,” says a women’s rights activist in Faryab province, who asked not to be named for her safety.

“Unfortunately, the current situation in the country is we are going back to the 1990s. It means we go back to the darkness,” says the activist, whose district of Shirin Tagab fell to the Taliban a month ago.

“All Afghans, especially women, are suffocated by the recent actions of the U.S. government,” she says. “The U.S. should have defeated this ominous phenomenon on the ground, or forced them to make peace. But they introduced the Taliban as a power to the world [through direct negotiations], and did not realize the Taliban are the savage Taliban, who know nothing but terror.”

She saw signs of Taliban intolerance last October, as she prepared for World Teachers’ Day at a local girls school. Money had been raised for a party, but a new computer lab at the school prompted local “radicals” to start a rumor that immoral films were being shown, and that “days of infidelity” were to be celebrated, she says.

The night before the event, Taliban fighters crept past guards and burned down the school.

“We wrote a letter to the Taliban and asked them to work together to build a peaceful Afghanistan, to provide education for the future ... to teach the young generation the lesson of self-confidence, mutual acceptance, and national unity,” says the activist. “But the Taliban threatened to kill me and my father in response.”

This month, American forces withdrew from their last base at Bagram in the dead of night, more than two months ahead of President Biden’s deadline.

As peace talks have stalled, signs from the battlefield indicate the Taliban are now pursuing “military victory” and that “provincial capitals are at risk,” Marine Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, the chief of U.S. Central Command, said this week.

“I don’t think the Taliban political leadership were expecting the kind of gains that they had over the last 1 1/2 months, which itself raises questions about differences between [them] and military commanders,” says Timor Sharan, a former deputy minister in the Afghan government.

“If they occupy more ground, and we increasingly see [local] commanders going back to the way they have known – which is limiting women, closing girls schools, wedding halls, and so forth – I think there is a serious gap here, within the Taliban itself,” says Mr. Sharan, director of the Afghanistan Policy Lab.

“My fear is that the Taliban political leadership is losing their control over events on the ground,” he says.

A longing for freedoms

That could impact how easily the Taliban can impose their will on a population that largely rejects their strict interpretation of Islam.

The Afghanistan Analysts Network said that research it published this month, for example, “challenged the idea that women in rural areas are satisfied by what is often portrayed as ‘normal’ by the Taliban or other Afghan conservatives.”

“Almost every woman we spoke to, regardless of the political stance and level of conservatism ... expressed a longing for greater freedom of movement, education for their children (and sometimes themselves),” the Kabul-based think tank said.

And yet, from their first days of control in each district they capture, the Taliban have instructed Afghans – often using mosque loudspeakers, printed instructions, and megaphones in marketplaces – that women must wear the all-enveloping burqa, and always be accompanied by a male guardian.

Some Taliban insist on payments of food or cash, or that each village produce 20 fighters for their cause. Others ordered that girls over 15 years old be provided as wives. Still others prohibit watching television, or using mobile phones.

Human Rights Watch last week documented mass forced expulsions and the burning of homes by Taliban fighters in northern Kunduz province. And everywhere, girls’ education and women’s rights are being rolled back.

“They swear to the people that all their restrictions and laws are in accordance with Islam, that whoever violates them is an infidel and their death is permissible,” says Sayed Hassan Hashemi, a civil society activist in Faryab, who has seen the aftermath of five Taliban school burnings.

“Taliban actions are different from their [leaders’] speech, as the ground is different from the sky,” says Mr. Hashemi, whose district is now under Taliban control. “The Taliban leaders in Qatar live in luxury homes, they and their families enjoy life, but they don’t know what injustices their fighters do on local people.”

“First we close the schools”

An official Taliban statement July 12 by spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid called the reports of abuse “enemy fabrications” and said statements attributed to the Taliban “that impose restrictions on locals, threatens them, specifies gender laws, regulates lives, beards, movements and even contains baseless claims about marriage of daughters” are not real.

Yet the Taliban on the ground are not shy about their aims.

“When we take a village, we sleep in the mosque, we don’t bother people in their homes,” a Taliban commander identified as Mollah Majid told France 24 this week, near the northwestern city of Herat.

“But the first thing we do is close down the government-run schools,” he said. “We destroy them [and] put in place our own religious schools, which follow our own curriculum, in order to train future Taliban.”

That is the concern of one teacher in northern Mazar-e-Sharif province, whose district recently fell to the Taliban, and who asked not to be named.

“In the beginning, when we saw the Taliban interviews on TV, we hoped for peace, as if the Taliban had changed,” says the teacher, who experienced their rule in the 1990s. “But when I saw the Taliban up close, the Taliban did not change at all.”

New rules “are not tolerable, because women get used to a free life for 20 years, so it is very difficult for them to live under the restrictions,” says the girls schoolteacher.

“When I see the Taliban, I feel that I see the enemy of my religion, culture, and traditions,” she says. “If we surrender to the Taliban, the future ... will also be dark. So my message to the whole new generation is to fight until the last moment.”

A deeper look

In Bronx and beyond, the pandemic revealed resilience

A project to tell the story of the Bronx – at the center of the American pandemic – emerged with a surprising takeaway that echoes worldwide: the strength of human resilience.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

When a handful of students at Fordham University embarked on the Bronx COVID-19 Oral History Project, they were expecting stories of hardship, loss, and trauma. But in some ways, what they found was the opposite.

“Despite one of the darkest eras of the city in recent memory, the light of community, family, and perseverance shone through in the voices of the Bronx COVID-19 Project,” wrote two of the co-founders in a campus newsletter.

During the past few decades, researchers have probed more deeply into what some scholars call a “psychological immune system” that enables many people to respond to even the worst of situations and to recover from their resulting traumas. Such findings do not minimize or marginalize trauma and suffering. But they suggest that from even the most traumatic experiences, people can emerge stronger.

Says the director of the Stress, Trauma and Resilience Program at The Ohio State University: “If there is a silver lining that could come out of this, it would be that people are understanding that while the negatives scream at you, the positives – the resilience you can always find in people – these are only whispers” that bear listening to.

In Bronx and beyond, the pandemic revealed resilience

When Bethany Fernandez first began to document oral histories in the Bronx during the pandemic, her own life was “chaotic,” she says – her familiar routines upended, her days confronted with fear and uncertainty.

But the past year and a half has become, almost in a strange way, a time of profound personal growth and self-discovery, says Ms. Fernandez, a lifelong resident of the Bronx, a borough of New York City.

The communities surrounding her were among the most afflicted in the country, and they were being documented relentlessly in the news. But when she decided to join a group of fellow students at Fordham University to launch the Bronx COVID-19 Oral History Project, she found a reality not fully captured in the news, she says.

“In moments like these, a cynical person might think, ‘Oh, people are going to be selfish’ – resources are scarce, survival of the fittest, or whatever,” says Ms. Fernandez. “But no, it was the complete opposite. People were willing to give, people willing to extend themselves, even if they may not have had that much to give or to extend.”

Far from tales of woe, in fact, she and the five others in the project found their subjects again and again using a particular word to describe their experiences: resilience.

Resilience in the face of hardship and trauma has always been a part of the human story. But during the past few decades, researchers have probed more deeply into what some scholars call a “psychological immune system” that enables many people to respond to even the worst of situations and to recover from their resulting traumas.

Such findings do not minimize or marginalize trauma and suffering. But just as science begins to understand and address post-traumatic stress, many researchers also find that human resilience can bring on what they call post-traumatic growth, a constructive and life-changing shift in their emotional lives. From even the most traumatic experiences, people can emerge stronger, gaining a deeper sense of their place in the world in a way that is positive and meaningful.

“If there is a silver lining that could come out of this, it would be that people are understanding that while the negatives scream at you, the positives – the resilience you can always find in people – these are only whispers,” says Ken Yeager, director of the Stress, Trauma and Resilience (STAR) Program at The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Human beings are wired to take particular note of the dangers that surround them and even focus on stories of trauma and fear. “The fight-or-flight response actually helps the species as a whole to survive, but it does nothing to make you happy,” Dr. Yeager says. “It does nothing to help you build resilience.”

“We always build resilience in groups, in core groups of people who are cooperating and caring for each other,” he says.

The Bronx COVID-19 Oral History Project tells this story.

Looking at the Bronx differently

Alison Rini, a senior from New Jersey studying English and Italian, had collected oral histories before – as a research assistant with Fordham’s Bronx African American History project and with the Bronx Italian American History Initiative. But there was something different about documenting stories during the pandemic.

“It was such a surprising experience, finding these examples of people describing their resilience in the midst of such hard times – in the Bronx, in particular,” Ms. Rini says. “I really liked being part of this project in that, in the news at the time you heard so much about these neighborhoods in New York City … that had all these high rates of hospitalization and death.”

“But with our project, we were able to talk to individual people … and just go in depth into their life and their story, and instead of looking at it broadly in this kind of horrified way, finding this sense of community – people coming together and standing up for each other.”

The Bronx wasn’t alone in this. A recent report by the British medical journal The Lancet analyzed numerous studies on mental health during the pandemic. The authors found that after an initial spike in overall levels of depression, anxiety, and distress at the outset, these began to fall to pre-pandemic levels in a relatively short amount of time. In some instances, measures of these experiences even declined.

“The pandemic has been a test of the global psychological immune system, which appears more robust than we would have guessed,” wrote scholars Lara Aknin, Jamil Zaki, and Elizabeth Dunn in The Atlantic. “In order to make sense of these patterns, we looked back to a classic psychology finding: People are more resilient than they themselves realize.”

The authors emphasize that such broad trends should not erase “the immense pain, overwhelming loss, and financial hardships” so many have faced over the past year and a half, especially disadvantaged populations and those whose suffering was made even worse by COVID-19.

“But the astonishing resilience that most people have exhibited in the face of the sudden changes brought on by the pandemic holds its own lessons,” they wrote. “Human beings are not passive victims of change but active stewards of our own well-being.”

The stories in the Bronx COVID-19 Oral History Project illustrate these findings.

“What was discovered through our research was a dedicated, authentic, and human picture of the Bronx unlike any project has seen before,” wrote two of the student co-founders of the project, Veronica Quiroga and Carlos Rico, in a campus newsletter. “Despite one of the darkest eras of the city in recent memory, the light of community, family, and perseverance shone through in the voices of the Bronx COVID-19 Project.”

“You’re stronger than you thought”

In what Ms. Fernandez calls one of her most memorable interviews, the owner of a Bronx restaurant described how she lost nearly 85% of her business and struggled to stay afloat after laying off most of her employees.

Though the restaurant specializes in Puerto Rican and American cuisine, the owner, Maribel Gonzalez, kept the original name of the restaurant she bought 16 years ago, South of France. She said it is an homage to the love story of the first owners, who constructed a replica of the restaurant where they met and fell in love in France before moving to New York.

Describing herself as a person of faith, Ms. Gonzalez said she had always offered her local community a free buffet every Wednesday. During the pandemic, as she and one or two employees struggled to keep the restaurant open, she kept that tradition alive, providing a free buffet at the height of the shutdown, even if only for an hour or two a week.

“You know, in all of this devastation, there are also a lot of blessings, because you find that you’re more resilient, that you’re stronger than you may have thought,” Ms. Gonzalez told the project. She said her restaurant provided hundreds of meals for front-line health workers in partnership with others, supported by donations from a GoFundMe page.

“When you need to lug that 50 pound bag because you have to make whatever money you can, because maybe some of it can go to feed families that can’t afford it, you find the strength, you get the stamina, you find the chutzpah, if you will, to lift that bag, because there are so many depending on it – myself, my business, my future, the future of my employees, and those of my community.”

“So I take a little better care of myself, and I’ve developed a couple muscles in the interim!” Ms. Gonzalez told the project with a chuckle.

Learning how to be adaptable

In an interview with Ms. Rini, the executive director of the South Bronx education center described a similar experience.

“The Bronx, as much as it has been through, continues to be resilient,” said Derek Smith, whose A House on Beekman struggled to serve its lower-income clientele.

“There needs to just be an understanding that everything isn’t equitable, and everything isn’t equal and fair,” he told the project. Yet “people will continue to figure it out, to show up. … That’s one reason why I love working in this community, is that no matter what is given to us, we will figure it out.”

During the shutdown, many of A House on Beekman’s clients found themselves without adequate internet connections or computers. New York’s Department of Education had been supplying lower-income households with a computer, but this wasn’t enough for those with multiple children who needed to attend remote classes at the same time.

So the organization started providing their own devices, about 20 or so, to families with these needs, Mr. Smith said. And in many instances, their role became listening to those who just needed to talk about what they were going through.

“I want to look at it in a positive sense in that … we’ve had to learn how to be adaptable,” he said. “We’ve had to learn how to adjust on the fly. And I think that if any organization is able to do that, that is going to set them apart in the future, and then only make them stronger as well.”

In two dozen interviews with Bronx teachers, families, artists, and community leaders, people described a similar sense of energy, positivity, and resilience, says Mark Naison, professor of history and African and African American studies at Fordham, who advised the students.

“You know, we found all these people who were doing amazing things to help keep the community alive during this time,” he says.

The project had a profound effect on Ms. Fernandez as she wrestled with the challenges in her own life.

“It was the one thing that stood out to me, the generosity that was shown all over, even throughout the time of the pandemic,” she says. “Because when you see how resources are limited, when you’re being stretched out by work, by family obligations, by life and all of that, even with all the suffering going on, people were willing to give, people were willing to offer compassion and kindness.”

How a river town relocated, with climate lessons for today

This Illinois town up and moved after devastating floods. Now perched 400 feet higher, it's a model of perseverance – but with cautionary lessons – for a world wrestling with climate change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Doug Struck Correspondent

When floods overtopped the levees in August 1993, half of Valmeyer was plunged under 14 feet of water. The other half on sloped terrain left houses holding a foot to 8 feet of water.

As residents of this small Illinois town waited and the receding river revealed its damage, the concept of moving the whole town took shape. Nearly 70% of the people said yes. “They didn’t want to see the town go away,” says Dennis Knobloch, an investment and insurance broker who was mayor at the time.

Just a few years later, with help from state and federal funds, the residents were living on higher ground about 2 miles away. The new Valmeyer is neat and orderly, yet there are only a few retail businesses and no recognizable “heart” of the place – a challenge that’s typical in such relocations.

Increasingly, say researchers, the lessons here are relevant as many communities around the world face existential threats of climate change: higher seas, floods from supercharged storms, or furnace heat waves. Experts call the expected pullbacks “managed retreat.”

“I’ll never forget it,” resident Susie Dillenberger says of the smell of rotting debris after the flood. But “we never lost hope.”

How a river town relocated, with climate lessons for today

It was 1:30 a.m. Dennis Knobloch stood at the top of a hillside cemetery – “that cemetery right there,” he says, pointing over his shoulder. The water was coming. He and others from the town had worked for weeks, sandbagging levees, bulldozing rock and rubble, to try to hold the swelling river. They had failed. His radio crackled: The last levee was gone.

“It’s your call, mayor,” the utility chief said.

Mr. Knobloch gave the order: Cut the power. He watched as the town below him – his town – flickered to dark, street by street, engulfed by the night and the Mississippi River.

“It was the hardest thing I did in my life,” the former mayor says now.

Hundreds of small Midwest towns like Valmeyer were caught in the Great Flood of 1993. Unlike most of the others, the survival of Valmeyer – born anew, 2 miles away in a cornfield about 400 feet higher – is getting renewed interest 28 years later.

Increasingly, say researchers, Valmeyer may be a model for communities facing existential threats of climate change: higher seas that flood coastal communities, more frequent floods from supercharged storms, or furnace heat waves that make their accustomed homes unlivable.

The planners look at the trends and say a pullback from vulnerable areas is inevitable. Call it “managed retreat.” Last year in the United States, 1.7 million people had to flee natural disasters, and many found they could not return to their homes. The trends are expected to accelerate.

“Valmeyer remains the poster child of managed retreat in the U.S. up to the present,” says Nicholas Pinter, a professor and associate director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at University of California, Davis.

There have been dozens of complete or partial relocations of towns in American history, Dr. Pinter writes in the journal Issues in Science and Technology. Many were of Native American or Alaskan Inuit communities that were in vulnerable locations to start. Other towns have repeatedly fled rivers – Niobrara, Nebraska, hauled its houses by horse and wagon away from flooding in the Missouri River in 1881 and moved again in 1971.

“We never lost hope”

But many proposed relocations did not succeed. Valmeyer did, with a few asterisks.

“They made it happen. It wasn’t a bunch of ivory tower or Washington, D.C., experts,” says Dr. Pinter.

When the floods overtopped the levees in August 1993, half of Valmeyer, 30 miles south of St. Louis, was plunged under 14 feet of water. The other half on the sloped terrain left houses holding a foot to 8 feet of water.

The town had flooded three times before in the 1940s, cleaned up, and survived. This was different. The floodwaters stayed long enough to become fetid, the houses full of rotting debris and mold. A second crest hit a month later.

“The smell. I can’t describe the smell. I’ll never forget it,” says Susie Dillenberger, who lived by one of the levees. She recalls barges bringing rock and rubble up the river to try to reinforce the barrier as the water rose. She worked with other volunteers to fill sandbags. She slept with her family in one room in case they had to flee suddenly.

“We never lost hope,” she recalls. Teams rushed to fill “sand boils,” wet spots where the river snuck under the levees. They labored until a mandatory evacuation was declared and the river rose in their vacated houses.

As the townsfolk waited they stayed with friends or relatives – and eventually in trailers provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, quickly nicknamed “FEMAville.” And they met in the school gyms of nearby towns to begin to think of what to do. As the receding river revealed its damage, the concept of moving the whole town took shape.

How to replant a town

“We took the idea to the residents,” recalls Mr. Knobloch, an investment and insurance broker who four months earlier had been reelected mayor. “We said we have no idea how to do this, and no idea if it’s going to work. We’re not even sure yet what’s involved. But if we try it, will you be willing to be a part of it?”

Nearly 70% of the people said yes. Many had grown up in Valmeyer, and had families there for two or three generations. “They didn’t want to see the town go away,” he says.

Soon they focused on a 500-acre cornfield on a bluff 2 miles away. Residents split into a bevy of committees to work with planners, engineers, and architects. Within two months, Mr. Knobloch went to Washington with printed plans drawn up by the townsfolk, and asked for money. The politicians were impressed.

Eventually, state and federal governments pledged about 80% of the $33 million cost. The town bought the land on the bluff, pulled numbers from a hat to lottery off lots, and began construction. Mr. Knobloch quit his job – his wife, a microbiologist, supported the family – and worked full time through all the permits, planning, and problems of creating a town from nothing. They dealt with 22 agencies, unexpected limestone sinkholes, protected bat species, and a hurried archaeological excavation when Native American artifacts were found.

“It was gruesome. You know, I don’t really know how my kids remembered what I looked like,” he recalls. “But looking back on it now, with what we were able to achieve, to keep the community together and keep the people together – definitely, it was well worth the time and effort.”

It took three to four years before 700 residents were in homes in the new Valmeyer. Government officials had predicted it would take 10 years.

Homes, but few businesses

“It’s a success,” says Lyle Schwarze. He had helped fill sandbags to try to save old Valmeyer. But he admits that moving has given the town more life. Because of the flood plain restrictions, he says, “You couldn’t grow in the old place.”

The town has slowly climbed to 1,300 residents. The new Valmeyer is neat and orderly, with manicured and still-new looking homes. The roads loop and curl into cul-de-sacs, with names like Falcon Pointe, Cedar Bluff Drive, and Hunter’s Ridge. There are cars in every driveway, and few people on the sidewalks. There is no Main Street, no grocery store, and only a few retail businesses – a gas station, a convenience store, a new Dollar General store. There is no recognizable “heart” of the place.

“It’s a bedroom community,” acknowledges Gertie Eshom, who grew up in Valmeyer and now lives in the new town. Other residents say it looks like a suburban housing development. Even the present mayor, Howard Heavner, acknowledges its flaws.

“The commercial part never developed like they hoped it would,” says Mr. Heavner, who taught in the Valmeyer high school for 33 years. “People just shop in St. Louis. They stop on their way back from work.”

The UC researcher, Dr. Pinter, says that is a common problem. Traditionally, FEMA has “pointedly neglected” giving money to businesses to relocate, he said.

The town’s proximity to St. Louis – it’s a half-hour drive – has both added to Valmeyer’s appeal and detracted from its rebirth as a self-sufficient town. It is drawing younger residents with its lower housing prices and a small school.

Preserving a sense of community

“Valmeyer is a good small-town community and I knew I wanted to stay here,” says Kyle Kipping, a 29-year-old financial broker who shunned the big city to stay in Valmeyer.

But if there’s no common place to stroll or chat, Valmeyer has found other ways to make a community. The Jaycees, Lions Club, Knights of Columbus, Chamber of Commerce, and school clubs are fervently ambitious. As in many small towns, school events are central to a civic agenda. There are three churches. The Jaycees organize an annual July Fourth Midsummer Celebration that draws thousands of people from the surrounding county.

The three-day event is not held in new Valmeyer; instead, townsfolk wind their way down the hill to return to a park and baseball field on the old town’s site.

“We’ve always chosen to keep this event as it was, as kind of a tribute to what we had here before,” says Mr. Knobloch.

They return to old roads that have faded to gravel beside tilting street signs and a rusted stop sign. Soy fields inch toward the ballpark. Trains still rumble past day and night, hauling chemicals and cars, cargo and cows, to and from St. Louis. The train engineers always salute ghosts of the former town with a loud whistle as they near the empty crossing.

“It’s peaceful down here,” says Kevin Dickineite, sitting with his wife, Betty, in the yard of their white frame home. They are among about a dozen families who chose not to move. They had just bought their house in Valmeyer before the flood, after living for 10 years in a double-wide trailer in a corn field, and they liked it.

“The house has four bedrooms, and each of our kids had their own room for the first time,” says Mr. Dickineite.

“I can understand some of the older people didn’t want to deal with the water again,” adds Betty Dickineite. “But there are younger people who said they wished they had not moved away.”

They watch as former neighbors set up blankets in front of the now-empty lots that once held their homes. The three-day event douses maudlin memories with an extravaganza: an 11-game baseball tourney of impressively skilled amateur teams, bands that crank out rock and country music until past midnight, a parade with fire trucks and tractors that follows the Main Street while clowns throw candy to the kids and pass out drinks. And the fireworks – a main fundraising effort of the Jaycees – light the July 4 night with a close-up sound and fury to rival any big-city show.

Bobbie Klinkhardt whose family owned the town’s largest business, Mar Graphics, watches the parade. Her family determinedly reopened the business in the new town – they only recently sold it to new owners – but she remains wistful for old Valmeyer. “I don’t know why we thought we could ever replace it the way that it was. Do I wish I had stayed? Yes.”

“It’s a community,” she concedes of the new Valmeyer. “It’s just not my community.”

Even Mr. Knobloch, the architect and indefatigable executor of the move, who has a street named after him in the new town in appreciation for his work, acknowledges what was lost in the relocation. He’s a precise, straightforward man, and his eyes rim red when he talks of his old home.

Does the new Valmeyer seem like home to him? “No,” he answers quickly, without hesitation. His family will sit on a blanket where they used to live.

“It’s home,” he says. “It’s home.”

Film

Russians say Marvel’s ‘Black Widow’ is ‘klyukva.’ That’s not flattering.

Marvel’s latest blockbuster is about former Soviet superheroes in Russia trying to deal with their past. But Russian filmgoers wonder: What if Hollywood actually showed the real Russia?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Russian moviegoers have a special term for films whose storyline or atmosphere just does not ring true. It’s klyukva, or “cranberry.” Reviews of the Russia-centric “Black Widow,” Marvel’s latest blockbuster, bristle with that term.

Film critics in the country have panned the movie, in part for what they describe as a hopelessly inept portrayal of Russia and Russians. But audiences are more forgiving; many just come for the action, and the film does not disappoint in that department.

“These Russians are just superficially created, mainly by giving them Russian names and putting them through stereotypical Russian rituals, like drinking vodka straight from the bottle in some remote Russian village,” says critic Roman Kovalyov. “By now this sort of thing triggers more smiles than irritation.”

Critics and fans alike appear to have enjoyed Red Guardian, the bearded and paunchy Soviet-era superhero played by David Harbour.

“Overall, this film was a sprawling klyukva,” writes blogger Alexey Litovchenko. “But Alexei Shostakov, the Red Guardian, is a real Russian hero. ... [Mr. Harbour] turns any scene into a holiday with his immense charisma alone.”

Russians say Marvel’s ‘Black Widow’ is ‘klyukva.’ That’s not flattering.

It’s not easy to be a Russian movie fan. Hollywood films, which dominate the cinematic fare available here, invariably depict the motherland in the bleakest of tones, while Russian characters tend to be pitiless, power-mad, morally vacuous villains whose chosen careers always involve some brand of evil-doing, be it mafia boss, KGB spy, seductress/assassin, cybercriminal, or just a brutish henchman.

But maybe there’s a little ray of hope in the new film, “Black Widow,” which weaves a backstory for the titular Russian character from wildly popular Marvel Cinematic Universe, aka Natasha Romanoff, played by Scarlett Johansson. It opened across Russia over the weekend, drawing half of all cinemagoers and earning about $3.3 million, which is pretty good considering that much of the country is still under tough pandemic-related restrictions.

In the MCU, Natasha, a former KGB-trained killer who redeemed herself by joining the Avengers, is already dead, having sacrificed herself for her friends in the recent blockbuster “Avengers: Endgame.” So this prequel is an attempt to delve into her origins, to illuminate the forces that created her. That inevitably leads to Russia, and her dysfunctional Russian pseudo-family, with whom she briefly reunites.

For Russian audiences, including vast legions of Marvel fans, that holds a special interest, and perhaps a touch of hope that in the future Russian characters may not be so unrelentingly bad. Reaction from critics and fans so far suggests that most are not much interested in the feminist overtones that have dominated Western commentary, but there are distinctly mixed opinions about how it portrays Russia and Russians.

Natasha’s “family” is rooted in a fiction created by Moscow spy masters, who had set them up as “sleeper” agents in the United States. The father, Alexei Shostakov (played by David Harbour), is now a bearded and paunchy Soviet-era superhero known as Red Guardian, the counterpart of Captain America. The mother, Melina Vostokoff (Rachel Weisz), is a scientist who lives in a remote Russian cottage with a bevy of trained pigs. And Yelena Belova (Florence Pugh) is the little sister who, like Natasha, was sent as a child to the Red Room, a former KGB outfit that brainwashes young girls and turns them into heartless assassins, known as “widows.”

Without giving much away, the movie intersperses action sequences among Natasha’s efforts to gather the family. A touching reunion ensues. Then chaos breaks loose.

In general, Russian film critics have panned the movie, in part for what they describe as a hopelessly inept portrayal of Russia and Russians. But going by viewer comments to some of the film reviews, audiences are more forgiving. Many people just come for the action, and the film does not disappoint in that department.

“These Russians are just superficially created, mainly by giving them Russian names and putting them through stereotypical Russian rituals, like drinking vodka straight from the bottle in some remote Russian village,” says Roman Kovalyov, a critic with the online film journal Posle Titrov. “By now this sort of thing triggers more smiles than irritation. These tropes are very well established.”

Alexander Polozhenko, a blogger in the Siberian city of Irkutsk, agrees. “I was glad to see Natasha driving around in a [Russian-made] Niva car, and getting her mail from the Russian Post,” he says. “But I would have liked to see more Russian spirit, more Russia. But it’s not there, not even in the prison scenes. I think the producers don’t know much about the cultural peculiarities of Russia, and didn’t make any effort to find out.”

But one pseudonymous fan on the KinoPoisk film review website offered a retort to those views. “I’ll say this: just turn off your brain and enjoy. Good humor, good fights, just awesome opening (perhaps the best in all Marvel films), and sometimes unusual directing. The film is perfect for this time. Overall, I liked it,” the viewer commented.

Cranberry cinema

The generally dismal image of Russians in Hollywood films has not escaped the notice of Russian politicians. Seven years ago a group of nationalist deputies of the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament, tried to introduce a bill restricting the number of American movies allowed to play in Russian cinemas. But after they met with leading Russian film distributors, who complained about a massive loss of revenue if the bill passed, the whole idea was dropped. (As of 2014, Russia was the world’s seventh-largest market for film distribution.)

Still, some politicians continue to complain. “Something needs to be done about films in which everything connected with Russia, with Russian culture, is openly demonized or vulgarized in stupefyingly primitive ways,” Batu Khasikov, a senator from the southern republic of Kalmykia, told the upper house of parliament recently.

“In China, there are cases where films get banned for allegedly offensive content, but that never happens in Russia,” says Alexey Naumov, a political analyst with the business daily Kommersant. “The Russians we see in Hollywood movies are clearly not real Russians. They are lazy stereotypes. That’s why most Russians don’t care. They don’t see themselves reflected in it. ... It probably helps that Russians are never shown as weak or pathetic. They are always strong, cunning, and agile. And they stand by their ideals, even if they are nasty ones.”

Russian moviegoers have a special term for films whose storyline or atmosphere just does not ring true. It’s klyukva, or “cranberry.” Reviews of “Black Widow” bristle with that term.

But some of them make a few intriguing exceptions, especially for the Red Guardian character, whom most viewers – professional critics and fans alike – appear to have genuinely enjoyed.

“Overall, this film was a sprawling klyukva, with huge plot holes and utter indifference to its own characters,” writes Alexey Litovchenko on Kinokratia, a website run by daily newspaper Rossiskaya Gazeta. “But Alexei Shostakov, the Red Guardian, is a real Russian hero. He’s a simple-minded, good-natured father who grumbles that the country has been destroyed, who tells tall tales, jokes inappropriately and likes to drink but, if necessary, will punish his enemies on behalf of his family – even if they are not real. ... David Harbour in this role is incredibly organic. He turns any scene into a holiday with his immense charisma alone. We’d really like to know more about him.”

Russian audiences also appear to have liked the mother, Melina, who trains pigs, drinks hard, engages in intimate conversation with her two fictitious daughters, and ultimately joins them in the effort to take down the wicked Red Room. Indeed, by pitting themselves against their evil Soviet origins, these Russian characters appear to redeem themselves. Unlike in the standard plot of Cold War-era films, the enslaved Russian women are not liberated by exposure to Western ideals – contemporary Russian audiences would probably greet that as pure klyukva – but rather with a dose of vaporous anti-mind-control elixir.

But now that Natasha is dead, it’s clear that one of the film’s central purposes is to set up Yelena to take her place in the MCU going forward. Just about everyone agrees that Russian audiences were really impressed by Yelena, who freed herself from the evil grip of the Red Room in the film, and would welcome her fresh incarnation as one of the good guys.

“We had a time when all villains in Hollywood movies were Russians. Then they were Muslims. Now they’re Russian again,” says Kirill Razlogov, a film historian. “Maybe we’ll get to a place where there’s more balance: some good Russians, some bad ones. But I am not at all sure that Russian audiences will prefer the good ones.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

South Africans’ resilient response to riots

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

After nearly a week of looting and mob violence in South Africa’s two most populous provinces, volunteers by the hundreds have begun to clean up their littered streets and help restore the shops they depend on. Others who guarded their communities against the looters have begun to work with the soldiers finally deployed to KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng by President Cyril Ramaphosa.

The volunteers, together with local charities, community leaders, and business groups that worked behind the scenes to quell the violence, have provided an inspiring counterpoint to the image of a lawless South Africa – and to those who triggered the riots after the imprisonment of former President Jacob Zuma for contempt of court.

“The community has again – after the ravages of Covid-19 – dug deep to show resilience and bravery,” declared the news editors of City Press, The Witness, and News24.

On Wednesday, after he had sent troops into the troubled areas, President Ramaphosa told political leaders that the government was “intensifying its efforts and working in partnership with civil society to stem public violence.” It was a welcome acknowledgment that governance in South Africa relies first on the self-governance of its individual citizens.

South Africans’ resilient response to riots

After nearly a week of looting and mob violence in South Africa’s two most populous provinces, volunteers by the hundreds have begun to clean up their littered streets and help restore the shops they depend on. Hundreds of others who guarded their communities against the looters have begun to work with the soldiers finally deployed to KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng by President Cyril Ramaphosa.

The volunteers, together with local charities, community leaders, and business groups that worked behind the scenes to quell the violence, have provided an inspiring counterpoint to the image of a lawless South Africa – and to those who triggered the riots after the imprisonment of former President Jacob Zuma for contempt of court.

“The community has again – after the ravages of Covid-19 – dug deep to show resilience and bravery,” declared the news editors of City Press, The Witness, and News24.

The mayhem that began last Friday was on a scale rarely seen since the end of apartheid in 1994. At least 70 people have been killed. It also revealed deep divisions within the ruling African National Congress (ANC) and within South African society. In particular, the slow response by the president caused alarm. Yet it also forced nonstate actors and institutions to step up and reestablish rule of law on the streets.

So far, a key part of the social healing among South Africans has been gratitude.

“We are especially grateful to our loyal customers, many of whom have offered to help with cleanup operations,” stated the Shoprite supermarket group.

The ANC Veterans League, a group of senior party members who led the struggle against white rule, said it was grateful for the seven provinces that prevented and resisted the looting. “We would like to congratulate the law-abiding citizens and patriots for defending our constitutional democracy,” the veterans stated.

On Wednesday, after he had sent troops into the troubled areas, President Ramaphosa told political leaders that the government was “intensifying its efforts and working in partnership with civil society to stem public violence.” It was a welcome acknowledgment that governance in South Africa relies first on the self-governance of its individual citizens.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Safe in the storm

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Joyce Heard Hawes

A woman whose coastal community faced multiple hurricane threats explores the power of God, good, to bring safety and peace of mind even in frightening situations.

Safe in the storm

How can we feel God’s presence when a severe storm is predicted? The Bible offers some helpful ideas. A Psalm tells us, “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble” (Psalms 46:1). And Proverbs suggests that God has “gathered the wind in his fists” (30:4), showing that there is no force outside of God’s control.

As an example of understanding this, Christ Jesus remained calm when he was in a ship with his disciples during a storm. The disciples feared for their lives, but Jesus “rebuked the wind, and said unto the sea, Peace, be still. And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm” (Mark 4:39).

Jesus knew God as the only legitimate power. It was this realization that enabled him to not only silence the violent storm, but prove God’s loving control over many discordant conditions. And as we recognize the limitless power of God, good, we too can experience safety and protection more fully.

Years ago while living on the coast of Florida, a hurricane was approaching, threatening the millions of people in that area, many in high-rise apartment buildings. My husband and I prayed on the basis taught in Christian Science, and many others were also praying for safety. We were affirming that the power of God, who is completely good, is supreme, and that we could trust that power.

When the hurricane was just 10 miles offshore, it suddenly – some said miraculously – lifted up and never touched land. There was much talk in our area about how prayer had protected us all from danger.

Some time later a more dangerous hurricane (Category 5) was approaching, and many residents either decided to evacuate or were told to do so. We were not required to evacuate, and my husband felt we should stay. During his military career, he’d had many proofs of God’s protecting power through an understanding of Christian Science.

I agreed with him, so we stayed and devoted many hours to prayer and to study of the Bible and “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science. A couple of statements from Science and Health were especially helpful. The first was this passage, in which “Mind” is used as a synonym for God: “The real jurisdiction of the world is in Mind, controlling every effect and recognizing all causation as vested in divine Mind” (p. 379).

The second was the spiritual definition of the word “wind” given in the glossary of biblical terms found in Science and Health. It reads: “That which indicates the might of omnipotence and the movements of God’s spiritual government, encompassing all things” (p. 597).

We held to the spiritual fact that God is the only valid power, and that this omnipotence supersedes any material sense of an opposite power. Spending the night in the hallway of our home, we prayed with the 91st Psalm, affirming that we were safe “in the secret place of the most High” (verse 1) and cherishing this truth as the spiritual reality for everyone in the expected path of the storm.

At one point during the night a very tall tree was uprooted and fell just four inches from our home, which was completely protected except for a few tiles blown off the roof.

Later we learned that the winds had been clocked at 164 miles per hour a few blocks away at the National Hurricane Center and that a 17-foot-high storm surge had flooded many of the low-lying areas. There was much property damage, and unfortunately a few lives were lost, but we were very grateful for God’s protecting power manifested in the experience of so many in the area.

One of the blessings that came during the aftermath was a wonderful feeling of brotherhood among the many ethnicities in our community. Everywhere, residents seemed eager to help their neighbors and came together to rebuild the community. This spirit of cooperation and unity had not been so evident previously. Also, much gratitude was expressed for the outpouring of love and support which came in from all over our country and beyond. To me this reflected God’s universal love for all.

Truly, no matter what kinds of challenges we face, when we understand that God, divine Love and Mind, is infinite, we can experience Love’s ever-presence – comforting, protecting, and holding us all in its care.

A message of love

On a fire's front line

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for the next installment in our “Stronger” podcast, which looks at how a Las Vegas nurse strove to overcome the economic challenges that hit women nationwide during the pandemic.