- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why can’t Biden be the next LBJ or FDR? It comes down to math.

- As Tunisia’s democracy wobbles, an unexpected gain: first woman premier

- Faith or politics? Trump supporters swell evangelical pews.

- Who’s a Daughter of the American Revolution? Answer grows more diverse.

- From beetles to clouds, finding happiness in nature’s surprises

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Roll over, Beethoven. AI tackles his 10th Symphony.

On Saturday, Ludwig van Beethoven’s new symphony will premiere in Bonn, Germany. Technically speaking, the German composer’s 10th Symphony is a co-write. His collaborator? A computer.

Beethoven left behind fragmentary sketches for the follow-up to Symphony No. 9. Almost 200 years later, a team of musicologists and computer scientists have taught artificial intelligence how to predict which notes Beethoven might have chosen for the missing pieces.

“When you write your email or text, your [computer] or phone suggests to you what words you would write next,” says team member Ahmed Elgammal, director of the Art & AI Lab at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. “This kind of predictive model is very similar.”

The 18-month project was an iterative process. Computer programs learned to recognize patterns in Beethoven’s creative process by examining his earlier symphonies. The AI also had to figure out which instruments to use for the arrangement, which will be performed by the Beethoven Orchestra Bonn.

Mr. Elgammal happily offers a preview by humming a few bars of the 25-minute piece. (Schroeder, the Peanuts pianist, will finally have something new to play by his hero.) The programmer knows that critics will question whether computers can replicate Beethoven’s genius. Yet he believes there’s plenty of joy in this ode to the beloved composer.

“It’s basically a way to show the world what AI can do,” says Mr. Elgammal, who believes it’s a tool akin to a creative assistant. “It has a major role in the way art will be created in the future.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

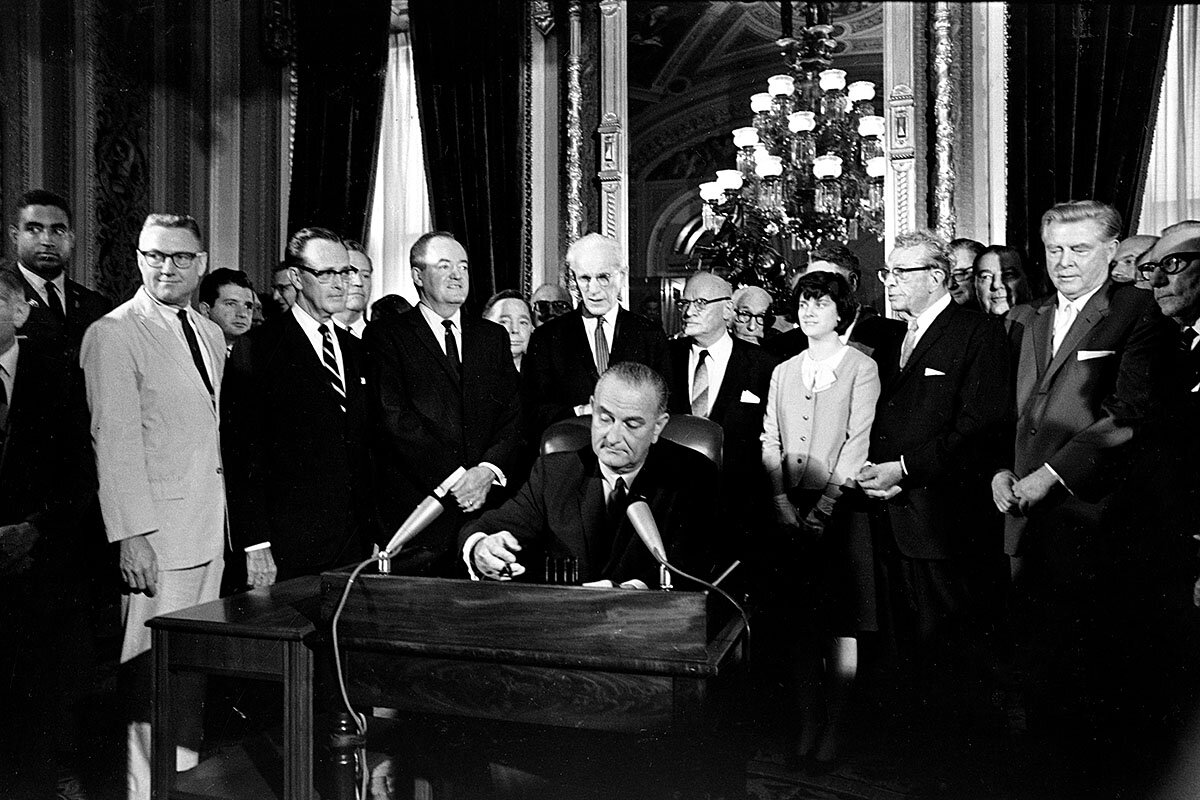

Why can’t Biden be the next LBJ or FDR? It comes down to math.

The president has a sweeping domestic agenda, and the slimmest possible Democratic majority with which to try to pass it. The difficulty in getting that done has been on vivid display lately.

-

Dwight Weingarten Staff writer

Any expectation that President Joe Biden could be the second coming of LBJ or FDR stops at a cold, hard fact: His congressional majorities are almost impossibly narrow.

“It’s hard to be a truly transformational president with zero-point-zero extra votes in the Senate, and virtually no extra votes in the House,” says veteran Democratic Rep. Brad Sherman of California.

In today’s 50-50 Senate, the Democratic “majority” comes only with the vice president’s ability to break ties. In the House, it’s a mere 220-212.

Democrats’ nominal control in Washington frees Republicans from responsibility to govern. That reality is seen most urgently in Congress’ need to avert a catastrophic default on the national debt later this month. Should a default occur, it would be the latest crisis to befall the administration, after missteps over the pandemic, the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the Southern border. The president’s job approval sank below 50% in August, and it has stayed there since.

But while Mr. Biden’s first term may not look like LBJ’s, Representative Sherman thinks he will ultimately get a good chunk of his domestic agenda passed. “Biden is realistic about what to get and is strategic about how to get the most he can,” he says.

Why can’t Biden be the next LBJ or FDR? It comes down to math.

He was a man of the Senate, a skilled legislator who rose to the vice presidency under a much younger, more charismatic president. Upon assuming the Oval Office in his own right, he knew that his time to accomplish big things was limited – and he swung for the fences.

That president was Lyndon B. Johnson, a force of nature who has morphed from man to legend in the half century since he left office. And President Joe Biden is trying to follow the LBJ playbook in key ways. He knows time is short and he’s aiming high, attempting to pass a massive domestic agenda that aims to build on the legacies of both Presidents Johnson and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But any expectation that President Biden could be the second coming of LBJ or FDR stops at a cold, hard fact: His congressional majorities are almost impossibly narrow.

“It’s hard to be a truly transformational president with zero-point-zero extra votes in the Senate, and virtually no extra votes in the House,” says veteran Democratic Rep. Brad Sherman of California. “Look at what Franklin Roosevelt had. Look what Lyndon Johnson had.”

In today’s 50-50 Senate, the Democratic “majority” comes only with the vice president’s ability to break ties. In the House, the Democratic majority is a mere 220-212, with three vacancies. By contrast, the authors of the Depression-era New Deal and 1960s Great Society programs were operating with wide Democratic majorities, giving party leaders a true mandate from voters – and a cushion that allowed some Democratic lawmakers to vote no.

Still, Representative Sherman, a member of the 96-member Congressional Progressive Caucus, predicts a Biden success – albeit using a slightly different metric: “If you’re going to weight transformational accomplishments by legislative majorities, he’s going to be off the charts.”

Such an outcome is far from certain. After House Speaker Nancy Pelosi canceled a promised vote last Friday on a popular $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill at the urging of progressives – who insist that bill plus the larger package of climate and social spending must move in tandem – Democrats have been forced back to the drawing board to salvage the president’s agenda.

Looming deadlines

Democratic congressional leaders have moved their self-imposed deadline to Oct. 31, though Mr. Biden himself made clear last Friday that’s not hard and fast. Patience has become his watchword.

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s in six minutes, six days, or in six weeks,” the president said.

Trust between progressives and the Democratic Party’s smaller centrist bloc has been shaken. Mr. Biden – who lately appears to have cast his lot with the left, despite his history as a moderate – held video conferences the past two days with House members of both blocs, and on Tuesday afternoon, flew to Michigan to pitch his “Build Back Better” agenda. He appeared at a union training center in Democratic Rep. Elissa Slotkin’s district, which President Donald Trump narrowly won in 2020.

Next year’s midterm elections loom large, as do gubernatorial races – including a close governor’s race in Virginia next month. In modern times, the president’s party almost always loses seats in his first midterm election, and control of Congress is clearly on the line. The need to demonstrate competence and accomplishment only adds to the sense of urgency.

Mr. Biden appears to be in such a tight spot, some wonder if having Democratic congressional majorities is even a net benefit for him. In January, Johns Hopkins University political scientist Yascha Mounk suggested in The Atlantic that Mr. Biden might have been better off if his party had not narrowly won control of the Senate, since then it would have been “much simpler for Biden to manage the expectations of the party’s activist wing.” Professor Mounk also posited that Senate control could make it less likely for Mr. Biden to win reelection.

Today, Democrats’ nominal control in Washington frees Republicans from responsibility to govern. That reality is seen most urgently in Congress’ need to avert a catastrophic default on the national debt later this month. Should such a default occur or even come close enough to harm the nation’s credit, it would be only the latest crisis to befall the Biden administration – after missteps over the pandemic, the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the Southern border. The president’s job approval sank below 50% in August, and has stayed there since.

The myth of LBJ’s persuasiveness

As for Mr. Biden’s ability to win over members of Congress to pass his agenda, the LBJ comparison again comes into play. But the so-called Johnson treatment, in which the larger-than-life Texan used sheer size, force of personality, and intricate knowledge of detail to bend members to his will, is more myth than reality, says George Edwards III, a presidential scholar at Texas A&M University.

“LBJ had a lot more power as Senate majority leader than he had as president – the power to change senators’ minds, for example,” Professor Edwards says. “He knew that perfectly well.”

The effectiveness of presidential speechifying and travel to shape public opinion is also overrated, he adds.

“We should not expect the president to be changing a lot of minds, because they never do – including LBJ,” says Mr. Edwards, author of the book “On Deaf Ears: The Limits of the Bully Pulpit.” “They don’t change a lot of minds with the public and they don’t change a lot of minds with Congress. When presidents have success in Congress, it’s because they have clear majorities.”

Presidents’ ability to sway opinion has become even more difficult in recent times, given the proliferation of partisan media, social media, and political hyperpartisanship.

The fact that Mr. Johnson’s rise to power came after the 1963 assassination of President John Kennedy should also not be underestimated, says presidential historian Robert Dallek. The country was already in a mood for change and for progressive advancement, he says – both in addressing civil rights and in adding health care to the social safety net.

“LBJ in a sense had a united country, which came together in anger and resentment over the fact that Kennedy had been killed,” says Mr. Dallek, author of a two-volume Johnson biography.

Stylistically, he says, Mr. Biden is no LBJ. The current president is a “much less cutthroat politician than Johnson was.”

“I’ve met Biden, and found him to be a nice man,” Mr. Dallek says. “He knows how nasty politics can be, but he prefers to work through accommodation.”

Biden allies in Congress were hopeful last Friday after his meeting with the House Democratic Caucus.

Longtime Texas Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, a vice chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, told reporters that the president was “magnificent,” “factually grounded,” and “ready to offer respect for all views.”

Representative Sherman, for his part, pushed back on the idea that Mr. Biden might be better off without slim control of both houses of Congress.

“It’s easier to bridge the divide between one end of the Democratic Party and the other than to deal with the divide between the middle of the Democratic Party and a good chunk of the Republican Party,” he told the Monitor after leaving the Democratic caucus meeting with the president in a basement hallway of the Capitol. “Biden is realistic about what to get and is strategic about how to get the most he can.”

As Tunisia’s democracy wobbles, an unexpected gain: first woman premier

Is there ever an odd time for progress? The symbolic victory embodied by Tunisia’s naming of a woman as prime minister comes amid a deepening battle over the quality of the nation’s democracy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Ahmed Ellali Correspondent

Before being named last week as prime minister of Tunisia, the first woman in the Arab world to hold such a position, Najla Romdhane was a university lecturer in geology and manager of World Bank-funded projects at Tunisia’s Ministry of Higher Education.

Yet rather than a celebration of breaking the glass ceiling, the academic’s sudden rise to the prime minister’s office has taken on new meaning in the Arab world's only democracy. Her appointment has illustrated Tunisia’s uncertainty since President Kais Saied’s assumption of emergency powers in late July: teetering between hope for positive change and fears of a disastrous backslide into authoritarianism.

Polls show the populist president still has strong support, including for his suspension of the constitution. But frustration with the economy is building, and his political foes are joining forces.

“Right now, all that matters is whether you are with or against Kais Saied, and that is not good for Tunisia itself. The whole political process has become Saied-centered,” says Eya Jrad, assistant professor of security studies at the Tunis-based South Mediterranean University.

“Even the first woman prime minister is being scrutinized because she took on the task from Saied in a not-normal state of affairs.”

As Tunisia’s democracy wobbles, an unexpected gain: first woman premier

It was always going to be an uphill climb for the Arab world’s first woman prime minister.

If a failing economy and a pandemic weren’t challenge enough, Tunisian Prime Minister Najla Romdhane has been appointed just as the Arab world’s lone democracy is at a critical crossroads: a broken political system and a constitutional crisis precipitated by an aloof president wielding near-absolute power.

Rather than a celebration of breaking the glass ceiling, Ms. Romdhane's unexpected political ascent has taken on new meaning.

Her appointment has illustrated Tunisia’s uncertainty since President Kais Saied’s assumption of emergency powers in late July, teetering between hope for positive change and fears of a disastrous backslide into authoritarianism.

“Right now, all that matters is whether you are with or against Kais Saied, and that is not good for Tunisia itself. The whole political process has become Saied-centered,” says Eya Jrad, assistant professor of security studies at the Tunis-based South Mediterranean University.

“Even the first woman prime minister is being scrutinized because she took on the task from Saied in a not-normal state of affairs.”

A university lecturer in geology and manager of World Bank-funded projects at the Ministry of Higher Education, Ms. Romdhane was plucked from relative obscurity to head the government just last week.

Calling her appointment, “an honor for Tunisia and a homage to Tunisian women,” Mr. Saied said her government’s main task will be to “put an end to the corruption and chaos that have spread throughout many state institutions.”

The move came weeks after the United States, EU, and France pressured the populist elected president, who seized extra powers in an emergency measure on July 25, to name a government, reinstate parliament, and return Tunisia to a democracy. On Sept. 22, Mr. Saied suspended the constitution, and all executive and legislative powers now lie with the president, who rules by decree and is “assisted by the head of the government.”

Friendly face?

Yet it remains to be seen what, if any, influence Ms. Romdhane will have.

Some fear she will be little more than a friendly face for the West.

Ms. Romdhane has yet to give a speech or press interview, with Mr. Saied still dominating Tunisia’s airwaves – and garnering rave reviews.

Mr. Saied is continuing his outsider, rail-against-the-system campaign to crack down on corruption and bring political parties to account that catapulted him from obscurity to the presidency in the 2019 elections.

Citing the COVID-19 pandemic, Mr. Saied on July 25 triggered an article in the constitution allowing for 30-day emergency rule. He shuttered parliament with tanks and dismissed the government.

When he finally suspended the constitution altogether last month, he unraveled a post-revolution political system the political system adopted after the fall of Tunisia's dictator in 2011, a pivotal event in the Arab Spring. Under this system, the president and a prime minister appointed by lawmakers shared executive powers.

Yet widespread frustration among Tunisians with partisan deadlock, corruption, and leaders’ failure to improve their daily lives have translated into an outpouring of support for his consolidation of power.

For many Tunisians, Mr. Saied is the savior of the country, not the destroyer of democracy.

“I’m happy with what the President has done so far, at least I can trust him,” says Jihane Rahali, an administrative assistant in Tunis, who says she grew tired of bickering MPs, political nepotism, and parties “looking after their own interests.”

“Kais Saied will improve the country step-by-step. I’m for the president to rule alone.” She pauses, adding, “but he should also be democratic.”

Popular mandate

Such expressions of support is why Mr. Saied has repeatedly told U.S. and EU officials that he has a popular mandate, if not a constitutional one, to push through reforms and combat corruption.

His claim is backed up by polling.

In late September, Tunis-based EMRHOD Consulting found that 79% of Tunisians approved of President Saied’s performance, slightly down from 82% in August.

A resounding 87% of those polled still support his July emergency measure; more than two-thirds, 69%, support his suspension of the constitution; and 68% considered Ms. Romdhane’s appointment a positive development.

In response to the question, “If presidential elections were held tomorrow, who would you vote for?” 71.2% named Kais Saied. The runner-up, at 21.5%, was, “I don’t know.”

But, cautions Columbia Global Centers Tunis director Youssef Cherif, “it is not clear whether this reflects Saied’s popularity or the unpopularity of his opponents.”

With the much-maligned parliament gone and his polarizing foil, the Islamist Ennahda party, neutralized, Mr. Saied is taking center-stage as the only actor in Tunisia – and with it, the responsibility to deliver.

Expectations are high.

Already this week, unemployed youths protested in Kaiouran and Tunis, calling on the president to give them jobs.

Should the president stumble or be slow to improve Tunisians’ daily lives going into winter, observers say the wave of frustration he has so expertly channeled may turn against him.

Economic pressures, too, are mounting.

Tunisia’s economy contracted 8.5% in 2020, and the private sector is only slowly re-opening after a devastating COVID-19 wave this summer. The Tunisian dinar is weakening, inflation is rising, and public debt has climbed to 88% of GDP raising fears Tunisia is rapidly approaching default.

Yet Mr. Saied has not given the economy urgency or focus, nor has he appointed economic advisers or hinted at a plan to get the country back on track. Negotiations have stalled with the IMF for a $4 billion bailout package designed to help Tunisia with its budget deficit and upcoming loan repayments.

Instead, he preaches that only a new constitution that jettisons the parliamentary system for a strong presidency can allow Tunisians to bypass political deadlock, root out corruption, and transform the country for the better.

United in opposition

It is unclear how long Tunisians’ patience will last.

“The constitution is not the Koran, it can be amended at any time, but now is not the right time to do it,” says Hassib Abidi, an unemployed law school graduate and a Saied supporter who is optimistic, but increasingly “concerned.”

“The president hasn’t even started working on the economy,” says Mr. Abidi. “In the last two months, the economy didn’t take a single step forward. I am not satisfied because the real [issues] are not being addressed.”

Amid the waiting, Mr. Saied is amassing a growing list of enemies among Tunisia's political elite. These include leftists, secularists, civil society advocates, Islamists, former supporters of the deposed dictatorship, the business community, and unionists.

“We remain confused because we have been waiting so long for the next steps and are concerned that the country can’t stand in a political vacuum and survive without a parliament or public institutions,” says Mounir Charfi of the Tunisian Observatory to Defend the Civil State.

The powerful trade unions, which helped oust Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali a decade ago, reversed their initial support of Mr. Saied’s measures, calling his suspension of the constitution a “danger to democracy.” Once-bickering parties are uniting to pressure the president.

“We thought that by triggering Article 80 of the constitution, the president would hold accountable everyone who committed wrongdoings and acts of corruption,” says Iheb Ghariani, co-founder of the Democratic Current, a liberal political bloc that backed Mr. Saied before allying with three other opposition groups last week.

“Instead, the president wants to impose his vision onto the political system. ... He is wielding absolute power and he is rejecting dialogue with everyone.”

Tweaking democracy

Mr. Saied appears set on drafting a new constitution largely by himself and putting it up for a national referendum while his popularity is still sky-high.

Yet the prospect of another new constitution, and a struggle over a more centralized political system, may, observers say, be a positive opportunity for Tunisians to make democracy work better for the people.

“Rather than the saving of Tunisia’s democracy or the end of it, this may be something in between,” says Mr. Cherif.

“This may be a case where democracy has revealed where it doesn’t work and if this is a real democracy – then it will correct itself through street movements, through civil society, through dialogue, and economic and political actors expressing their voices on and off the street.”

Mr. Saied, meanwhile, is boasting about the size of his rallies. He said 1.8 million supporters turned out in Tunis and outlying towns last Sunday (15% of the population), while Reuters reported it was more like 8,000.

On Tuesday he released a video of himself and Ms. Romdhane in which he touted the turnout. She didn’t get a word in.

Faith or politics? Trump supporters swell evangelical pews.

Many white Evangelicals think about their Christian identity as being explicitly tied to ideas of national identity. “Preserving or strengthening a commitment to religion is a way to strengthen an overall identity,” says a professor of modern Protestant theology.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

After years of stagnancy, the number of white Evangelicals surged from 25% of the adult U.S. population in 2016 to 29% in 2020, according to a Pew Research survey.

But this growth was fueled almost entirely by white supporters of former President Donald Trump, who began to embrace an evangelical identity after he was elected and accounted for the subgroup’s 6-point increase nationwide. Those who dropped the label, including the online movement of “#exvangelicals,” accounted for only a 2-point decrease.

“We can’t impute causality as to why the people who became evangelicals became evangelicals,” Gregory Smith, associate director of research at Pew, told the Deseret News. “But we can say, among Trump opponents, almost no one became evangelicals.”

Some evangelical leaders have decried the enthusiasm with which white Evangelicals have embraced the former president, wondering if the term itself has already come to simply refer to the Republican Party’s largest and most critical voting bloc. But others say the recent surge cannot be ascribed solely to party politics or the popularity of Mr. Trump.

“I think it’s pivotal that, no matter what your political affiliations are, not to approach this blindly, but to ask deep, resounding questions about morality and truth and justice,” says Dr. Corné Bekker, a theologian and pastor.

Faith or politics? Trump supporters swell evangelical pews.

As a theologian within the richly varied subcultures that make up evangelical Protestantism, Corné Bekker devotes much of his thinking to the theme of Christian renewal.

It’s the primary lens through which he helps train a new generation of evangelical theologians and ministers, says Dr. Bekker, the dean of the School of Divinity at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia. The school’s doctoral programs employ a methodology that aims to “renew and revitalize” evangelical congregations across the country, while a “renewal theology” provides the primary context in which they study church history and the tenets of orthodox Christian faith.

“In my work with pastors these days, there seems to be a true reawakening happening,” he says. “And within the evangelical movement as a whole, there is this kind of desire for God to break into our world and empower Christians to share the good news, which we believe would facilitate not only personal transformation, but societal transformation towards a more just, compassionate world.”

So he wasn’t necessarily surprised when a much-discussed survey found the number of white evangelical Protestants has once again begun to grow. After years of stagnancy or even, as with most of the country’s religious groups, outright decline, the number of white Evangelicals surged from 25% of the adult U.S. population in 2016 to 29% in 2020, according to a Pew Research survey in September.

But this growth, the survey also found, was fueled almost entirely by white supporters of former President Donald Trump, who began to embrace an evangelical identity after he was elected. They accounted for the subgroup’s 6-point increase nationwide. Those who dropped the label – including the online movement of “#exvangelicals” who said they were troubled by the faith’s approach to politics and cultural issues – accounted for only a 2-point decrease.

“We can’t impute causality as to why the people who became evangelicals became evangelicals,” Gregory Smith, associate director of research at Pew, told the Deseret News. “But we can say, among Trump opponents, almost no one became evangelicals.”

Some evangelical leaders have decried the overwhelming enthusiasm with which white Evangelicals have embraced the former president, wondering, too, if the term itself has already come to simply refer to the Republican Party’s largest and most critical voting bloc.

“[What] seems to be happening at scale isn’t so much the growth of white Evangelicalism as a religious movement, but rather the near-culmination of the decades-long transformation of white Evangelicalism from a mainly religious movement into a Republican political cause,” wrote the evangelical thinker David French in a recent essay titled “Did Donald Trump Make the Church Great Again?”

“What holds us together are our core beliefs”

But Dr. Bekker and others say the recent surge in white Evangelicals cannot be ascribed solely to party politics or the popularity of Mr. Trump.

At its spiritual core, he says, evangelicalism has long been rooted in four self-defining commitments: devotion to Scripture as God’s word, the centrality of Jesus Christ as the only true path to salvation, the necessity of a conversion experience, and a personal commitment to bear witness to the Gospel and support the most vulnerable people in society.

These traditions of American evangelicalism include a wide array of cultural groups, in fact. Most Black Protestant congregations maintain this conservative self-understanding, and the fastest-growing group of American Evangelicals today are Latinos who converted from Roman Catholicism, according to surveys.

“Many churches that I know ... have set time aside for prayer and fasting and self reflection and indeed asking the question, what does it truly, really mean to be a Christian?” Dr. Bekker says. “And amongst many evangelical churches we’ve seen promotion and adoption of multiethnic worship.”

He worships at New Life Church in Virginia Beach, founded in 1999 by two graduates of the Regent divinity program, a Black pastor and white pastor who together forged an intentionally diverse congregation that “consciously reflects our eternity in heaven,” its website says. “New Life is not a church built on sustaining a certain culture or politics; it is built on sustaining the Kingdom of God.”

A congregation of 600 two decades ago, it has since grown to 6,000 members who meet on four separate campuses, the most recent established in 2017. Still, with congregations so diverse, there are frequent reminders that Black Protestants vote for Democrats in overwhelming numbers, while white Evangelicals remain the bedrock of the GOP.

“I will tell you, that’s a difficult thing to do at the end of every election cycle,” Dr. Bekker says. “We almost have to have a reconciliation meeting. But what holds us together are our core beliefs and our focus on transformation and renewal.”

At the same time, however, a significant number of Trump supporters who now identify as evangelical rarely if ever attend church services, suggesting different kinds of forces are at play, many observers say.

“White evangelicalism has always been tied to ideas of whiteness and white Christian nationalism,” says Kathryn Reklis, professor of modern Protestant theology at Fordham University in New York. “At different moments the racial nature of white evangelicalism has come into focus or receded.”

“A way to strengthen an overall identity”

But as the country has become increasingly less white and Christianity starts to recede as a dominant cultural force, many have felt embattled. “There are many more white Evangelicals who have been learning to think about their Christian identity as being explicitly tied to ideas of national and racial identity,” says Professor Reklis. “Now, preserving or strengthening a commitment to religion is a way to strengthen an overall identity.”

Evangelicalism’s theological exceptionalism, too, has long dovetailed with specific ideas of American exceptionalism, scholars say. In the 1970s, when white Evangelicals began to reemerge as a political and cultural force, they first organized not around efforts to oppose abortion or sexual revolution, but around efforts to preserve their segregated Christian academies after withdrawing from integrated public schools, historians say.

“Evangelicals pride themselves on not being conformed to the world but on being transformed through Christ, but so often they appear to conform to the predominant cultural norms around them – Southern Christian support for slavery and opposition to racial integration, for example,” says John Vile, professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro.

At the same time, white Evangelicals coalesced around the candidacy of Ronald Reagan, who, channeling their vision of a seamless religious and national exceptionalism with the Puritan image of “a city upon a hill,” began his campaign in the Mississippi county where three civil rights workers were murdered by white supremacists defending the old order.

“It makes sense that card-carrying Trump supporters might become card-carrying Evangelicals,” says John Schmalzbauer, professor of Protestant studies at Missouri State University in Springfield. “Rather than seeing it as a late-breaking development, it is important to put it in the context of previous efforts to take white Southern evangelicalism’s racial and political message outside of the Bible Belt to the Midwest and even to the outer boroughs of New York City.”

“By demonizing Black Lives Matter and critical race theory from a national bully pulpit, Donald Trump channeled themes once voiced by Dixiecrat George Wallace, long before Southern white Protestants and their Northern allies cared about abortion or the Republican Party,” Professor Schmalzbauer says. “The first effort to take Southern white politics national revolved around race, not abortion. Trump is its heir.”

Though from a much different perspective, Dr. Bekker thinks it makes sense that Trump supporters would become Evangelicals. The former president, perhaps more than any other, gave his constituency of white Evangelicals his full-throated support, especially on matters of religious liberty.

“But I think it’s pivotal that, no matter what your political affiliations are, not to approach this blindly, but to ask deep, resounding questions about morality and truth and justice,” he says.

Following Scripture, he says all Christians should “pray for those that are in leadership, honor them,” Dr. Bekker says. But the church should also “regain that prophetic role of speaking out and especially to those the most vulnerable in our society – and I would say starting with the unborn and going all the way up to the stranger amongst us.”

“And then, certainly, to do all this with kindness and gentleness and treating all people with dignity,” he says.

Who’s a Daughter of the American Revolution? Answer grows more diverse.

Mention of the Daughters of the American Revolution may conjure up images of white members holding tea parties in WASPy Connecticut. But the society has been expanding its diversity and, consequently, reexamining its perspective on history.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

At a time when American history is deeply politicized, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) seems committed not only to expanding the country’s understanding of those who participated in the Revolutionary War, but also to shedding the stereotype of being a white, Anglo-Saxon organization.

For decades after its founding in 1890, however, that stereotype seemed true. There was little, if any, acknowledgment that people of color could have ancestors who helped America achieve independence.

Then, the first Black member of the modern DAR joined in 1977, and in 1984, the organization explicitly banned discrimination on “the basis of race or creed” after a Black applicant named Lena S. Ferguson was denied membership by a Washington, D.C., chapter. The group now has approximately 190,000 members, and Black Daughters say it’s easy to find people who look like them at big DAR events.

Furthermore, members’ research keeps surfacing a diverse group of patriots. One woman is exploring potential patriots from Mexico, and new Daughters from Louisiana’s Cane River Creole community recently joined.

According to DAR President Denise Doring VanBuren, the organization has two important jobs today: to continue honoring known patriots and to do a better job finding patriots of color and sharing their stories.

Who’s a Daughter of the American Revolution? Answer grows more diverse.

When Michelle Wherry joined the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), she wasn’t trying to make a statement. She simply thought it was a perfect way to honor her mother, who always said that she and her sisters came from a free Black line.

In the decade since, Mrs. Wherry’s DAR activities have received national attention, in large part because she and many of her friends in the organization don’t fit a stereotype long associated with the 131-year-old society for people whose ancestors helped America achieve independence. “When you think about DAR, you think about white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants,” Mrs. Wherry says. “And here you have women who are ... not what you think of as DAR. But they very much are.”

That’s more true now than ever. DAR’s membership has grown every year since 2007; it now has approximately 190,000 members throughout the United States and around the world. DAR has never tracked data on members’ ethnicity, but Black Daughters say it’s easy to find people who look like them at the organization’s annual Continental Congress and state events.

At a time when American history is deeply politicized, DAR seems committed not only to shaking its WASPy reputation, but also to expanding the country’s understanding of those who participated in the Revolutionary War. In fact, DAR’s diverse membership and its ongoing historical preservation work may offer a template for rethinking America’s origin story, and ultimately reveal a different side of patriotism – one that values a variety of voices and is unafraid of digging deeper into the nation’s shared past.

“Patriotism is taking an active role in making sure your country is portrayed in a truthful and honest and positive light,” says Nikki Williams Sebastian, a genealogist who joined DAR in 2014. “Being truthful is not a bad thing. ... History without documentation is mythology. And we have a lot of mythology in this country.”

In a move away from mythology, leaders created the E Pluribus Unum Education Initiative in 2020, which seeks to identify and promote patriots who’ve been left out of the popular historical narrative. The project includes a Patriots of Color database and exhibition titled “Remembrance of Noble Actions: African Americans and Native Americans in the Revolutionary War.”

Earning its reputation

The DAR was founded in 1890, after the Sons of the American Revolution refused to allow women to join its ranks. Initial recruits included more than 700 “Real Daughters” whose fathers had fought in the American Revolution, and members were eager to promote historical preservation, education, and patriotism.

In its early decades, DAR also served to distinguish members from the immigrant populations entering their communities.

“Those 1920s immigration restrictions had a real racist dimension to them,” says Francesca Morgan, author of “A Nation of Descendants” and an associate professor of history at Northeastern Illinois University. “So the ability to document yourself that far back and to claim a patriotic mantle at the same time had tremendous appeal.”

DAR “veered between civic and ethnic nationalism,” says Simon Wendt, an associate professor of American studies at Goethe University Frankfurt and author of “The Daughters of the American Revolution and Patriotic Memory in the Twentieth Century.” They were also an overtly political organization, he adds.

“They branded immigration a threat to the nation and rejected the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s,” says Professor Wendt. “These things are very much in line with mainstream conservative thinking in the 20th century.”

In the later half of the century, Congress tightened laws limiting the political activities of nonprofits. At the same time, some DAR members started challenging racism within the organization. The first Black member of the modern DAR joined in 1977, and in 1984, the organization had to rewrite its bylaws to explicitly ban discrimination on “the basis of race or creed” after a Black applicant named Lena S. Ferguson was denied membership by a Washington, D.C., chapter.

In recent years, the national organization has largely stayed out of conversations that could be deemed political, including debates over monuments of colonial figures or the 1619 Project.

Last summer, amid movements across the country promoting racial and socioeconomic justice, the National Society released a statement reaffirming the organization’s commitment to equality. The brief message reads in part, “We know that examining history helps us to better understand our nation’s long struggle to provide equality, justice and humanity for all Americans. … Bias, prejudice and intolerance have no place in the DAR or America.”

On a national level, President Denise Doring VanBuren says the DAR has two important jobs today: to continue honoring known patriots – “warts and all” – and to do a better job finding patriots of color and sharing their stories.

“We believe that as the descendants of these men and women, we have to be their voice, and we have to support and perpetuate the memory of what they achieved on behalf of our nation,” she says. “We’re kind of the human bridge between the patriots of the American Revolution and the generations that will follow.”

Family and country

Many DAR journeys begin with a desire to iron out a family tree. It’s not easy to get a stamp of approval from DAR’s genealogy board, but for some, that validation motivates them to get through hours upon hours of research.

Mrs. Wherry’s involvement with DAR has provided “great memories” of collaborating with her sisters, she says, one of whom died in 2019. But her participation also reflects a clear desire to set the historical record straight. When she had the opportunity to purchase a tree along a trail in Valley Forge National Historical Park as part of DAR’s Pathway of the Patriots campaign, she wanted it to stand for more than Ezekiel Gomer, her sixth great-grandfather who’d joined the rebellion in 1777. Instead, she dedicated her tree to all the “men, women and children of African heritage who were part of the American Revolution,” including individuals like Sally St. Clair, who disguised herself as a man to join the Continental Army.

Mrs. Sebastian, the genealogist, shares this sense of duty. More than 5,000 Black men, free and enslaved, served in the Continental Army, often for much longer periods than their white counterparts. “I want everyone to remember Black history is American history,” she says.

However, Mrs. Sebastian entered DAR through a white patriot, and like other Black Daughters, her story involves a forced relationship between an enslaved woman and the men who owned her.

Rethinking the Revolution

Edward Barrett, a plantation owner from North Carolina, was already in the DAR’s patriot database when Mrs. Sebastian started investigating her family’s history, she explains in an episode of the “Daughter Dialogues.” Mrs. Sebastian’s family used DNA testing to prove they were related to Barrett through Ellen Johnson-Mathews-Fisher, who was enslaved by Barrett’s grandson and bore his children during the 1860s.

Stories like Mrs. Sebastian’s highlight the importance of more inclusive membership policies. At one time, Mrs. Sebastian says, prospective members needed to have a legal marriage to prove descent. For families like hers, that was a difficult ask.

One of the most effective means of growing member diversity is simply studying the American Revolution, according to Yvonne Liser, DAR’s national membership chair. One Daughter, she says, is researching the expedition papers of Bernardo de Gálvez – who led the Gulf Coast Campaign against the British – and finding potential Daughters in Mexico. Louisiana recently welcomed a wave of new Daughters from the Cane River Creole community, all descended from French-born patriot Claude Thomas Pierre Métoyer and Marie Thérèse Coincoin, who was freed from slavery and became a powerful businesswoman in colonial Louisiana.

This research isn’t just about expanding membership or shedding any remnants of DAR’s ethnic nationalist roots. As one of the oldest and most popular lineage societies dedicated to preserving the Revolutionary War, members say DAR could help reshape the country’s understanding of its own origins.

“The leadership recognizes we do have a role to play in sharing these stories [with everyone],” says Mrs. Sebastian, “because it’s a more enriching story.”

Essay

From beetles to clouds, finding happiness in nature’s surprises

A guest essayist shares her observations about how the great outdoors has the ability to surprise and delight. Read on to discover why a lenticular cloud is more impressive than a Hollywood special effect.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Murr Brewster Corresondent

If you want to be joyful, you need to be surprised, often. To do this, you really need to go outside.

My husband and I like to give ourselves ample time to be surprised, so we spend a lot of time outside. We took off for Paradise Park on Mount Hood the other day. We sat down for lunch, expecting to be entertained by hawks riding the thermals at the mountaintop. We weren’t expecting to have a front-row seat to watch those thermals assemble lenticular clouds out of pure water and jazz, right above our heads.

Lenticular clouds are saucer-shaped drifts of perfection that form over large objects such as mountains. From a distance, it looks as though the mountain put on a cap. But close up, the water in the cloud is constantly renewing itself and trailing away – the very illustration of ephemera.

Things do look different from a distance.

From beetles to clouds, finding happiness in nature’s surprises

If you want to be joyful, you need to be surprised, often. And to do this, you really need to go outside. There’s only so much astonishment you can manufacture for yourself if you’re in your house – or, worse, in your head – all the time. You might come up with something unexpected in your refrigerator, but if you thought about it, you’d realize you should have seen it coming the moment you stuck that thing into the used yogurt container and shoved it toward the back. But if you’re outside, paying even a modicum of attention, something is bound to slap you happy.

It could be a bug. In fact, it’s likely to be a bug. You might see a beetle tripping along in the dirt, armored up in a metallic green you’ve seen only on a bridesmaid, and you’d catch your breath and say, “When did they start making those?”

Actually, they’re common, but you’re thrilled anyway because you didn’t know that. And it’s thrilling to come across something you don’t know, unless you’re the sort that has it all figured out all the time, in which case you might as well stay inside and mock people on the internet.

Or you could watch a spider wrapping a fly burrito. You knew they did that, but maybe it’s been a while since you had your nose that close to a spider, close enough to admire her eyes, her mastery. Maybe you didn’t remember just which legs she uses to spin the burrito.

Even people who actually do know a lot of stuff can be delighted at any moment, say, when they discover a rare violet peeking out of the duff. Nobody else knows it’s rare, or even there, but they do – they recognize it by its little nose hairs, or something – and they’re as tickled as you are with your green beetle. The power of surprise does not diminish with education. Education only improves your odds of being elated by something.

My husband, Dave, and I like to give ourselves as much time to be surprised as we can, so we spend a lot of time outside. We were hoping for beauty, at least, when we took off for Paradise Park on Mount Hood the other day. Beauty is a guarantee at Paradise Park, an alpine flower meadow just below the snowy peak of the mountain, and we had it to ourselves. We sat down for lunch, expecting to be entertained by hawks riding the thermals at the mountaintop. We weren’t expecting to have a front-row seat to watch those thermals assemble lenticular clouds out of pure water and jazz, right above our heads.

Lenticular clouds are surpassingly cool. They’re saucer-shaped drifts of perfection that form over large objects such as mountains. They are frequently misidentified as UFOs by people who are insufficiently awestruck by reality. Sometimes they lift off fully formed, one right after the other, and sail away in stacks. When you’re as close as we were, you can see there’s nothing static about them.

Lenticular clouds are a snapshot in water of the air currents over a peak. Water molecules coalesce as the air rises over the obstacle, and evaporate on the other side as the air current slides down again. When you see it from a distance, it looks like the mountain put on a cap. But the water in the cloud is constantly renewing itself and trailing away. It’s the very illustration of ephemera.

Things do look different from a distance. When I was a little girl, I thought there were two kinds of people, old ones and young ones, and they didn’t have much in common. Grown-ups had always been big; they started out that way. But I grew up. Surprise! Rejoice!

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

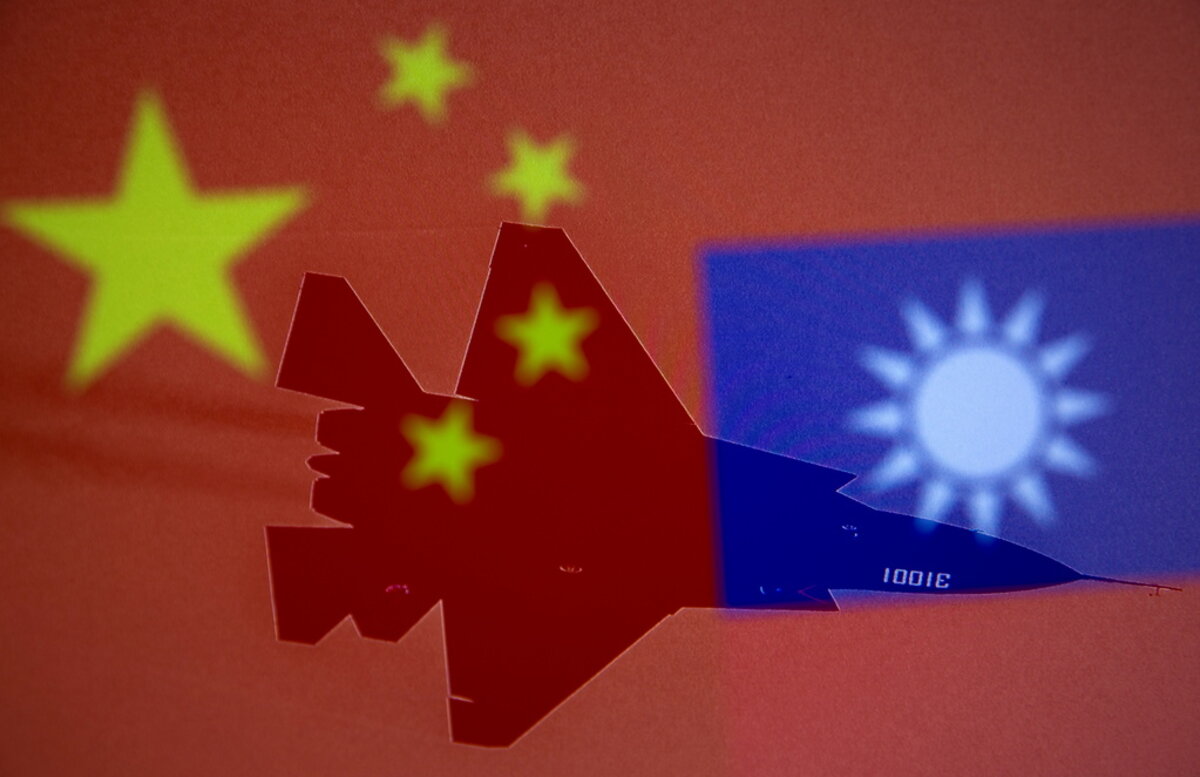

Inviting Taiwan to Biden’s democracy summit

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a speech last month, China’s new ambassador to the United States, Qin Gang, tried to make a case that his country – ruled by one party for 72 years – is a democracy. If that seems odd, consider the timing. In coming days, the Biden administration plans to send out invitations for a summit of “well-established and emerging democracies.” Taiwan, a thriving multiparty democracy for decades, is expected to be invited. In all likelihood, China will not.

Simply by arranging the Dec. 9-10 Summit for Democracy, President Joe Biden may have ignited a healthy competition between China and Taiwan to extol the virtues of their governing systems – even as Beijing increases its threats to take Taiwan by force. The mere possibility that Taiwan’s elected president might speak at the summit could be one reason China has escalated the number of fighter jets flying near the island.

China doesn’t make a good case for being a democracy by threatening Taiwan. Yet perhaps China should be invited to the summit – as an observer.

The world would benefit from a transparent debate over what is a democracy. The display of equality and freedom will be a good defense against China’s display of fighter jets.

Inviting Taiwan to Biden’s democracy summit

In a speech last month, China’s new ambassador to the United States, Qin Gang, tried to make a case that his country – ruled by one party for 72 years – is a democracy. If that seems odd, consider the timing. In coming days, the Biden administration plans to send out invitations for a summit of “well-established and emerging democracies.” Taiwan, a thriving multiparty democracy for decades, is expected to be invited. In all likelihood, China will not.

Simply by arranging the Dec. 9-10 Summit for Democracy, President Joe Biden may have ignited a healthy competition between China and Taiwan to extol the virtues of their governing systems – even as Beijing increases its threats to take Taiwan by force.

One of China’s governing virtues, according to Ambassador Qin, lies in the capability of Communist Party leader Xi Jinping to manage complexities and get things done. “He is loved, trusted, and supported by the people,” said Mr. Qin.

By comparison, Taiwan’s elected president, Tsai Ing-wen, admits that her island country’s free and open democracy has been imperfect. It has not always achieved consensus. Yet over time, its 23.5 million people have absorbed the values of democracy, which shapes their identity as Taiwanese.

President Tsai wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine this week that Taiwan “has an important part to play in strengthening global democracy.” Its experience with China’s threats makes it “part of the solution” for democratic countries struggling to find a balance between engaging authoritarian countries and defending democratic ideals.

The mere possibility that President Tsai might speak at the summit could be one reason China has escalated the number of fighter jets flying near the island. On Monday, a record 56 Chinese planes entered Taiwan’s air-defense zone. The aggressive action may be designed to prevent the world from recognizing Taiwan as an independent country or come to its defense.

President Biden says the U.S. will respond if Taiwan is invaded, as it would for allies Japan and South Korea. He set up the democracy summit “to tackle the greatest threats faced by democracies today through collective action.”

China doesn’t make a good case for being a democracy by threatening Taiwan for being a democracy that has made a choice for independence. Yet perhaps China should be invited to the summit – as an observer.

The whole world would benefit from a transparent debate over what is a democracy and how to defend it. The display of equality and freedom will be a good defense against China’s display of fighter jets.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Cured of cancer

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ursula B. Mueller

Informed by doctors that she was terminally ill, a woman turned wholeheartedly to God. Through prayer, her spiritual understanding deepened, and she was completely healed.

Cured of cancer

At one point in my life I became seriously ill. I wanted to rely on Christian Science, as I had experienced many proofs of God’s healing power in my life. However, in order to allay the fear of my friends, who were not Christian Scientists, I went to the hospital. I underwent numerous tests, and several doctors were consulted to assess the results. They told me there was nothing they could do to help me, because there was no known medical treatment that could cure this disease. They said that only a miracle could save me and that I was going to die. They mentioned a specific name for the disease, a particular type of cancer.

Later, on one occasion, when visiting a bookstore, I was tempted to look up the name in a medical reference book I came across. When I turned to the page, what I read was horrifying. However, I heard a very loud voice saying, “No! This is not true! You are the image and likeness of God!” This is how the Bible describes God’s children in its first book, Genesis.

Genesis also describes the life that God created as “very good” (1:31). When we’re receptive to this reality of our true nature as children of God, we experience that goodness more fully in our daily lives. The Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, explains in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” on page 392: “Admitting only such conclusions as you wish realized in bodily results, you will control yourself harmoniously.” However, by succumbing to the temptation to seek details about this illness, I had already admitted fear, devastation, and chaos into my thought. I had to throw these out of my thought by letting in divine Love, spiritual-mindedness, and purity.

The verdict that there was no medical treatment available made my friends accept my decision to rely entirely on Christian Science. I asked a Christian Science practitioner to pray with me. And I began to start reversing the devastating verdict by turning wholeheartedly to God.

During this period, the Lord’s Prayer with its spiritual interpretation by Mary Baker Eddy opened my eyes and took on new meaning for me – particularly this part about God: “Hallowed be Thy name. / Adorable One” (Science and Health, p. 16).

If God is the adorable One – the omnipotent and supreme – I cannot be impressed by any other name. I studied names for God, derived from the Bible and given in the Christian Science textbook: “Principle; Mind; Soul; Spirit; Life; Truth; Love; all substance; intelligence” (Science and Health, p. 587). I reasoned that if God is all substance, then there can be nothing, unlike Him that can claim to be substance or to have any effect. If God is Life, then I fully reflect Life. If God is Truth, I can attest to Truth as all-power. If God is Love, I am encircled by and filled with love. There is no space for fear. I felt God’s love for me, as His precious child. And all fear vanished.

In my spiritual studies and prayers I longed to better understand God and my relation to Him. The practitioner asked me to pray with “the scientific statement of being” given in the Christian Science textbook on page 468, which begins: “There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation, for God is All-in-all.”

I asked myself: What is true about my identity? God’s idea is pure and precious. Can there be anything that is so unlike God manifesting itself in me, and destroying my spiritual identity? If God is All-in-all, there is nothing that can exist outside His all-goodness – and I exist in His goodness.

The great truth in the Science of being is that we are, we were, and we always shall be perfect, as the image, and the full reflection, of God – painless, pure, and whole. The material sciences cannot inform me of my being; through prayer I deepened my spiritual understanding, and I found answers to the question, “What is my true being?” God is Life, and God is my life. Thus I express vitality, strength, and joy.

In about two weeks I was completely healed. This occurred more than 25 years ago, and the healing has been complete and permanent.

Christian Science is reliable, effective, and available to everyone. Indeed, God is omnipotent – the adorable One.

Adapted from a testimony published in the January 2021 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

Undaunted

A look ahead

You’ve reached the end of today’s package. Tomorrow’s fresh batch of stories includes a look at how a bottleneck of ships outside a port in California exemplifies worldwide supply chain problems.