- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Cosmic vision: What secrets NASA’s space telescope might reveal

- Climate worry meets gas-price anxiety. Can US really ditch fossil fuels?

- France’s textile capital tries eco-friendly fashion to get back in style

- As Bangladesh turns 50, the secret to its progress: Educate girls

- Capping off the year with the 10 best books of December

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Kentucky tornado relief: Generosity flavored by hickory smoke

What does barbecue taste like after a devastating tornado?

In Mayfield, Kentucky, it tastes like brotherly love, prepped with a dry rub of compassion and empathy.

On Sunday, first responders, residents, and volunteer cleanup crews took a break from sifting through the debris for a moment of savory solace. Jimmy Finch drove from Clarksville, Tennessee, early that morning, hauling a meat smoker behind his pickup truck. In a community still without power, Mr. Finch showed up to supply not just any free hot meal, but barbecued chicken, sausage, and burgers. That counts as fine dining amid the devastation.

We saw something similar last year when volunteers poured into Tennessee after it was ravaged by tornadoes. Kentucky and other states hit by storms this past weekend have also seen a flood of support. The Team Western Kentucky Relief Fund has received nearly $10 million in donations from 66,000 people, reported Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear on Tuesday.

Mr. Finch isn’t the only one cooking comfort food. Operation BBQ Relief, a disaster assistance group that touts “the healing power of BBQ,” arrived in Mayfield on Tuesday.

But Mr. Finch is a one-man pitmaster, paying out of his own pocket. “If it comes back to me, it comes back to me, if it don’t, it don’t,” he told The Washington Post. As his supplies ran low, folks started donating pork chops and breakfast sausages before the meat in their freezers spoiled. Neighbors helping neighbors.

In Mayfield, generosity smells like hickory smoke.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

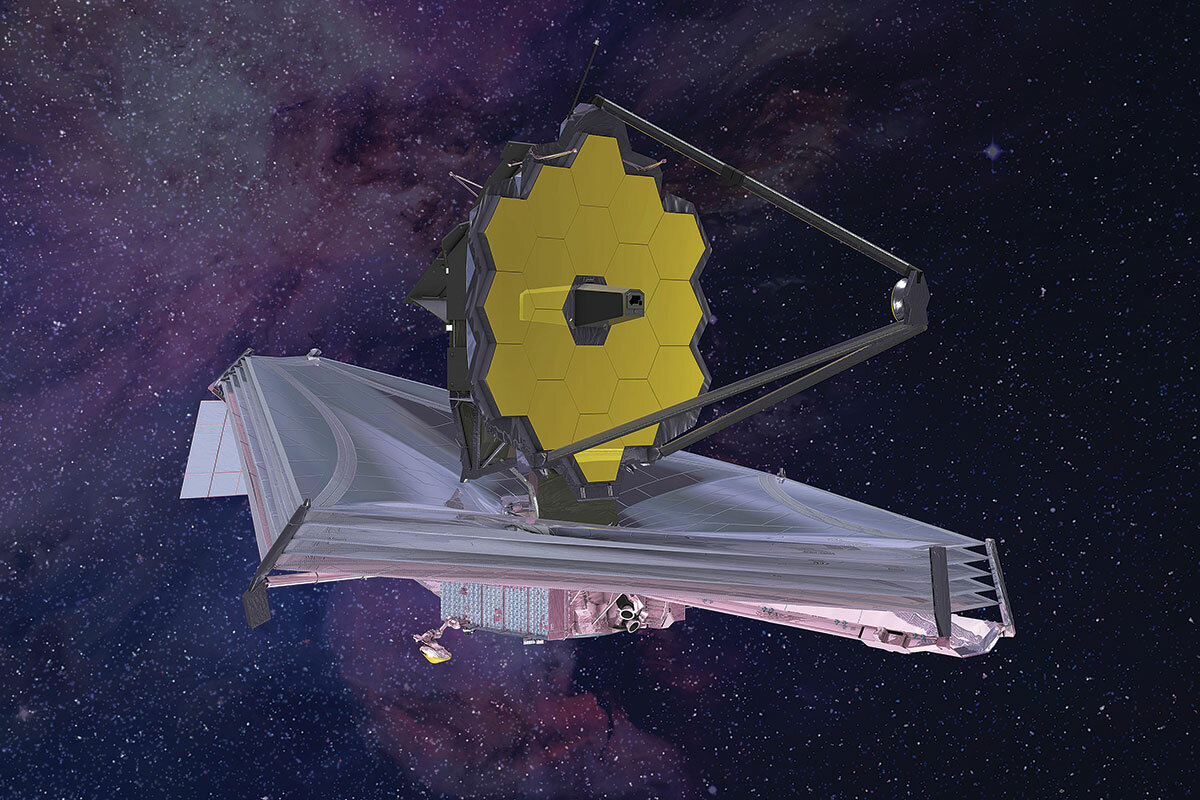

Cosmic vision: What secrets NASA’s space telescope might reveal

The James Webb Space Telescope promises a new window on the celestial past that could help explain everything from black holes to life on other planets. Our reporter also looks at lessons learned from doing an expensive, mega-science project.

-

By Adam Mann Correspondent

If all goes according to plan, the James Webb Space Telescope will start its journey a million miles into space later this month with a mandate to seek out the origins of the universe.

The origins of the JWST project go back to 1989, the year before the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope. Its mission was much humbler then, its cost estimates much cheaper. Now, after countless delays and nearly $11 billion in spending, NASA’s latest marvel is ready to redefine our understanding of the universe – and, perhaps, our understanding of how to feasibly pull off big space projects.

Scientists have high hopes for the JWST. Topping the list are insights into when the first stars appeared, how galaxies evolved, and the nature of dark energy.

But they know they can’t keep running projects the way they ran the JWST. The delays and cost overruns of the “telescope that ate astronomy” have altered astronomical research. New projects, based off information slated to come from the JWST, are coming in with rigorous – and honest – timelines and financial projections.

“The response [to the JWST] could have been, ‘We don’t know how to do big missions,’” says Bruce Macintosh, a Stanford astronomer. “And I’m proud that instead the response was, ‘What can we do to do a big mission without that happening again.’”

Cosmic vision: What secrets NASA’s space telescope might reveal

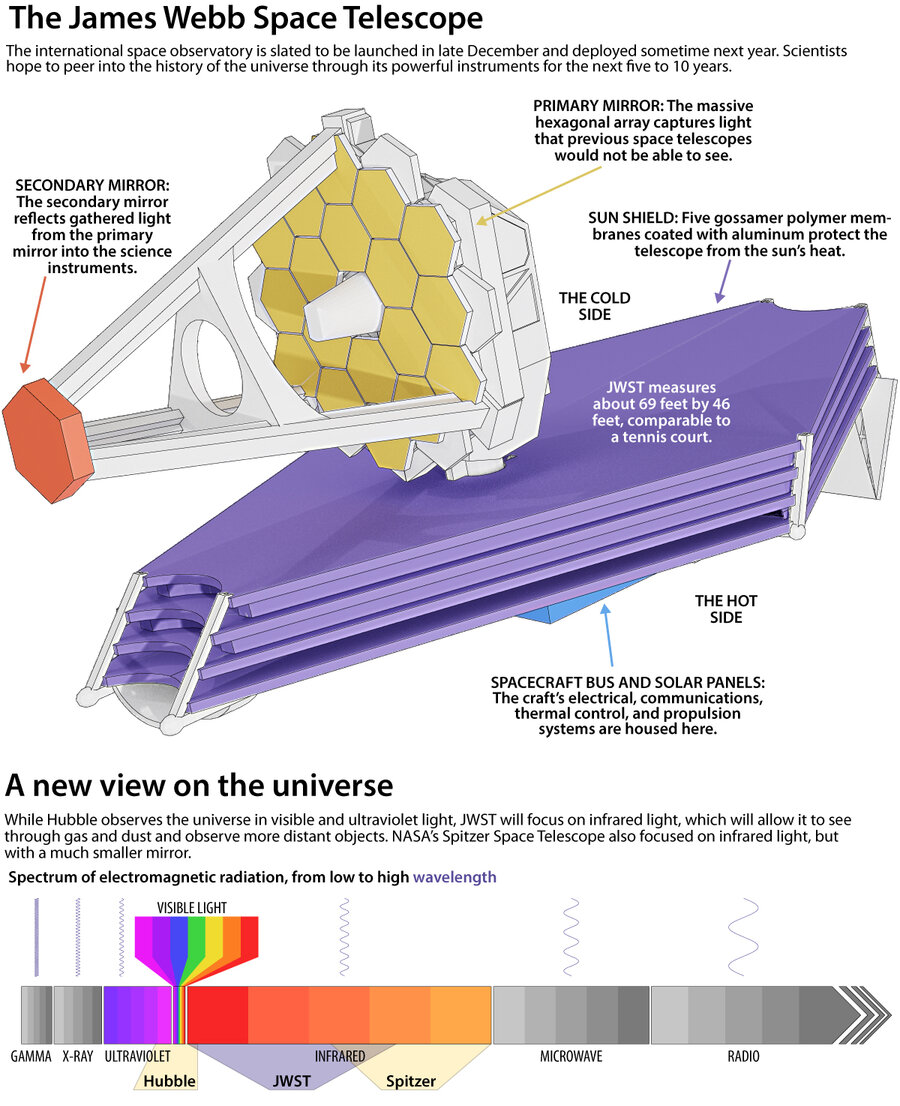

It will travel 1 million miles into space – five times the distance to the moon – and then unfurl a kite-shaped sunshade the size of a tennis court. This umbrella will deflect the sun’s powerful rays, allowing the instrument to operate at a cryogenic minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit, cold enough to see infrared wavelengths without interference.

It will carefully unfold a set of 18 hexagonal mirrors made of beryllium, a rare metal known for its strength and ability to withstand extreme temperatures, which are coated in a veneer of gold. These will bloom into a flowerlike configuration stretching 21 feet across, making it the largest mirror ever deployed in space.

It is this glistening marvel that scientists hope will usher in a new age of discovery about the cosmos.

If all goes as planned, the $9.7 billion James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scheduled to launch from French Guiana as early as Dec. 24, will provide humanity with the ability to peer farther into the heavens than ever before. The observatory could offer new insight into when stars first appeared, how galaxies evolved, and the nature of dark energy, as well as add knowledge to the question that most stirs the popular imagination – whether planets exist that can support life.

NASA

The performance of the telescope may also go a long way toward determining the future of big astronomy projects. Webb has cast a long pall over the field after suffering from a seemingly endless set of cost overruns and schedule slips. It prevented time and money from being spent on other priorities.

“It’s hard to believe it’s really happening,” says Laura Kreidberg, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, who will use the telescope to study the atmospheres of distant planets during its first year in space.

Astronomers are now looking ahead to determine how they will delve into the cosmic secrets of the future, including possibly sending aloft another giant observatory.

The negative experiences with JWST have already had at least one salutary effect: They have pushed scientists to offer more realistic financial estimates and timelines in their planning for upcoming projects and setting goals for space discovery. Further definition of and momentum for their plans, as well as the future of monumental science projects, will hinge on whether JWST can make it aloft safely – and what information it ultimately sends back to Earth.

Which is why astronomers are training their eyes so anxiously on a spaceport on the forested edge of South America, where a European Ariane 5 rocket will begin the observatory’s long journey toward the stars.

With its sharp nose and triangular shape, the new observatory looks a little like a Star Destroyer from George Lucas’ imagination. You almost expect Darth Vader to emerge from behind the yellow beryllium mirror to fire off an ion cannon at unsuspecting rebels on the planet Hoth.

The telescope’s actual origins are far less Hollywood. The first glimmers of the instrument that would become JWST appeared in 1989, a year before the Hubble Space Telescope launched, when researchers began to picture the famous observatory’s successor. Astronomers wanting to capture light from the universe’s earliest stars and galaxies knew they needed a large instrument placed far from our planet, whose bright glow would cause interference. Initial estimates proposed a price tag of between $500 million and $1 billion, though there was skepticism that it could be accomplished for so little, with a targeted launch date of 2007.

The telescope’s distance from Earth precluded the option of a repair mission, such as occurred with Hubble, meaning that the risk-averse engineers at NASA began rigorously testing every component during design and construction. As the project schedule lengthened, its science objectives expanded, especially as extrasolar planets became an increasing topic of interest in the field.

NASA, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, European Space Agency, CBS News, Nature, Space Politics, ScienceInsider, BBC, Scientific American

New instruments were added and anticipated costs went soaring. JWST eventually became one of the most expensive space projects in history, at nearly $10 billion. That figure doesn’t include the contributions from NASA’s two partners, the European Space Agency, which put up €700 million ($788 million) to launch the observatory and for instruments, and the Canadian Space Agency, which contributed $200 million (Canadian; U.S.$158 million) for sensors and other scientific tools.

After being labeled “the telescope that ate astronomy,” JWST survived a congressional cancellation attempt in 2011. NASA and private construction contractor Northrop Grumman put on a concerted effort to build public support and burnish its image. They even went so far as to display a full-size mock-up of the telescope at the 2017 Super Bowl in Houston, trying to turn a tortured science project into a rock star – the Bruce Springsteen of the cosmos. The ill-fated observatory’s problems continued the next year when it was discovered that screws and washers were falling off during vibration tests.

Yet backing from researchers has helped keep the project advancing through every delay and price increase. Scientists have stuck by the observatory because it will offer them exquisite and otherwise unobtainable views of the cosmos. For starters, its honeycomb mirror is nearly three times larger than Hubble’s and will have seven times the light-gathering power. And while Hubble sees in the same optical wavelength as our eyes as well as the ultraviolet portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, JWST’s instruments are geared toward the lower-frequency infrared. Because of the universe’s constant expansion, starlight emitted long ago has been stretched out toward such longer wavelengths.

Infrared light can also peer through obscuring dust. This means that only an infrared observatory can capture indispensable information about a long list of subjects – the origins of the first stars, the formation and development of galaxies, the compositions of both newborn and fully formed planets, and whether such planets contain the components necessary for life. Even as JWST helps solve some long-standing mysteries, it is sure to stumble across more.

NASA

“Anytime we have this new tool that allows us to get a different window onto our universe, we always seem to find something new and surprising,” says Lou Strolger, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore.

Hubble helped uncover the existence of one such famous shocker, an unexpected and enigmatic substance known as dark energy, which is driving the cosmos to expand ever faster. Using information from dying stars observed with JWST, Dr. Strolger and his colleagues will be able to pin down the universe’s expansion rate with greater precision than ever before, potentially gleaning whether dark energy’s influence has changed during different epochs in our universe’s history.

Given its long gaze, JWST is set to revolutionize our understanding of supermassive black holes in the early cosmos. Such beasts – often weighing millions or billions of times the sun’s mass – have been spotted lurking in the centers of just about every galaxy, though nobody knows how they came into being. One theory is that, in the distant past, clouds of hydrogen and helium grew so large that they collapsed under their own weight into the ultradense specks that are supermassive black holes.

“James Webb is actually going to be able to observe if this is the method,” says Allison Kirkpatrick, an astronomer at the University of Kansas in Lawrence.

Supermassive black holes are thought to be potential anchors around which the first galaxies coalesced. Every time telescopes look further into the universe’s past, they see galaxies larger than should be possible, almost as if they snapped together in an inexplicably short timespan. JWST will give researchers unparalleled access to those ancient days, potentially explaining how such galaxies came about.

NASA, University of Texas at Austin astronomy department

Because of conditions back then, the earliest stars were able to grow far bigger than their modern counterparts, becoming some of the most luminous stars that ever existed. Scientists suspect their glow was partially responsible for a process called re-ionization, when photons of light tore neutral atoms of hydrogen into their constituent protons and electrons. Most of the matter in the universe today remains in such a fractured form, and JWST might help astronomers determine what initially caused it.

The telescope’s infrared eyes will capture many details lurking inside the dusty cocoons where stars form today. Young stars tend to have disks of material around them, out of which spring planets. The specific molecules located at different places in these disks become the building blocks for such planets. JWST will give researchers the ability to identify where materials like water vapor can be found around sunlike stars, potentially explaining whether Earth formed in the presence of water or if the water was delivered later by asteroid and comet crashes.

“We’ve just never had this capability before,” says Alexandra Lockwood, communication lead for JWST, who studies protoplanetary disks at STScI.

Astronomers will also be able to scan fully formed planets and sniff their atmospheric compositions. Since every molecule leaves a characteristic signature in the light from such planets, researchers will be able to identify what gases are present. Hubble has done this for a handful of worlds and even detected water in their atmospheres, but simply knowing that the life-sustaining liquid is around isn’t enough to say whether a planet is habitable. Researchers need important contextual clues from chemicals such as carbon dioxide and methane, whose signals can only be seen in the infrared spectrum, to get a fuller view of distant places.

“For exoplanet atmospheres, JWST is an absolute game changer,” says Dr. Kreidberg of the Max Planck Institute.

NASA

Yet even an observatory as mighty as Webb will leave many questions unanswered. Scientists are already looking forward to their next heavenly facility, an infrared Hubble-sized instrument called the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. It is slated to join JWST in its locale a million miles from Earth by 2027.

Proposed during the austerity measures of the early 2010s, Roman uses a secondhand mirror donated by the National Reconnaissance Office, an arm of the U.S. Department of Defense. It, too, has suffered from delays, cost overruns, and cancellation attempts. Though it will study the nature of dark energy and count exoplanets, the telescope will be blind to many wavelengths of light.

In November, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a long-awaited road map called the Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020 that outlines where the field should go next. Written by panels of experts, the report envisions the research topics of the future and endorses instruments that NASA and the National Science Foundation could build to study them. Its top-line recommendation for space-based observations is a telescope equal in size to JWST that would launch in the 2040s and cover the ultraviolet, optical, and near-infrared portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, allowing it to directly address two-thirds of the survey’s open science questions.

“The report is bold, visionary, and extremely thoughtful,” says Ken Sembach, STScI’s director who conducts science and flight operations for JWST. “It’s crafted in a way that brings the whole community along.”

JWST’s fingerprints can be found all over the Decadal, both in the research topics it is expected to push forward and in the proposals it makes regarding this future facility. The survey estimates the prospective telescope to cost around $11 billion – roughly the inflation-adjusted price of both JWST and Hubble. It recommends the field establish a Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation Program that would invest money in developing the necessary cutting-edge equipment for such an instrument, with regular check-ins to make sure the project still makes sense.

“The history of JWST – obviously everybody in the room has to find their response to it,” says Bruce Macintosh, an astronomer at Stanford University in California who was a member of the Decadal’s steering committee. “The response could have been, ‘We don’t know how to do big missions.’ And I’m proud that instead the response was, ‘What can we do to do a big mission without that happening again.’”

Many see the report as indicating that astronomers have learned at least some lessons from their past experiences. “The Decadal is making you offer real estimates of your telescopes,” says Dr. Kirkpatrick at the University of Kansas. “When James Webb was proposed, they weren’t as strict about that, and so the plan was basically just to lie. The Decadal has stopped that nonsense.”

Yet it remains to be seen if the field can get itself out of what feels like a repeated cycle of delays and overruns that have hampered telescopes as far back as Hubble. Many are hopeful that Decadal’s recommendations will at least be a step toward avoiding future problems of this kind.

“I think the bottom line is that it’s saying, ‘It’s too hard to get locked into a particular brand,’” says Dr. Strolger of STScI. “Let’s think more about the science you want to achieve and the technology you need to get there.”

Once JWST is launched and new discoveries are regularly flowing in, researchers should be emboldened about moving ahead. Perhaps it makes sense that the field, which investigates some of the grandest and most sublime mysteries in existence, continually makes such audacious proposals in order to push itself forward.

“I think one of things about astronomy is that we think big,” says Dr. Lockwood at STScI. “If we always thought safe, we wouldn’t get the discoveries that inspire the public.”

NASA

Climate worry meets gas-price anxiety. Can US really ditch fossil fuels?

Our reporter looks at how Big Oil, gas prices, politics, and consumers all influence the expected pace of transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

For oil companies, the future looks as murky as the bottom of a barrel of crude. Investor appetite for oil stocks is ebbing. Government policies increasingly favor clean energy. And state lawsuits signal the industry could be held liable for its role in human-caused climate change.

But then there’s the flip side: ongoing public reliance on those fuels for heating homes, running factories, and especially powering transportation.

“Right now, I will do what needs to be done to reduce the price you pay at the pump,” President Joe Biden said at the White House on Nov. 23, as he announced an unusual move to release stockpiles from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Opinion polls reflect the competing priorities. In a 2019 poll most Americans said they want less offshore oil drilling. Yet polls this year show high concern about gas-pump inflation. And worldwide, many see natural gas as an attractive energy source – it’s often called a “bridge fuel” for the transition toward cleaner energy.

Many energy experts say a successful pivot away from fossil fuels is possible over the next couple of decades. But it will require deep investments and sustained commitment by both government and the private sector.

Climate worry meets gas-price anxiety. Can US really ditch fossil fuels?

Michael Day has made a good life for himself as a laborer in the oil and gas industry. He’s just 25 years old, and he’s worked as an industrial mechanic in refineries since he was 18, fresh out of high school – a job that’s given Mr. Day, his wife, and their children a comfortable life so far.

He has plans for their future, too. Mr. Day intends to continue this work until perhaps his late 40s, when he plans to retire early. His earnings have recently allowed him to purchase a small plot of land near his home in Texas City, Texas, where he’s gradually building an RV park he’ll rent to travelers.

It’ll be his turn to kick back “and make money,” Mr. Day says.

Even as the threat posed by climate change has prompted insistent calls for the world to wean itself from fossil fuels, there’s little reason to think Mr. Day’s plan is implausible. The outlook – attested by recent global outcries over gasoline prices or natural gas shortages – is that the world remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels. Even with ambitious environmental policies, the weaning will take decades.

Yet for the industry itself, this isn’t exactly a kick-back-and-make-money scenario. Investor appetite for oil stocks is ebbing. Clean-energy incentives and other government policies are nudging Big Oil toward a smaller future. And from lawsuits to leaked documents, the industry faces the possibility of being held liable for its role in human-caused climate change.

Add it all up, and these opposing trends may signal a central challenge for the years ahead: To stabilize Earth’s temperatures will require concerted efforts not just to replace fossil fuels, but also to mitigate potential economic disruption during the transition.

For oil companies, it’s an era in which ongoing demand for their products belies a future that’s as murky as the bottom of a barrel of crude.

“The industry’s whole objective is to delay, and that’s what they’ve spent the past three or four years doing. They’re running out of delay tactics, but they’re the world’s greatest delay artist,” says Richard Wiles, executive director of the Center for Climate Integrity in Washington, D.C.

Rising pressure due to climate change

He is referring to how states such as Delaware, New York, and Minnesota, among others, have filed lawsuits against oil companies alleging they misled consumers and investors in the role their products have played in environmental degradation and the climate crisis.

Other flags of uncertainty:

- A recent divestment announcement by Harvard University signals a wider pullback by investors. U.S. oil stocks as a group have been sharply underperforming the broader stock market since 2014, down more than 40% in value while the S&P 500 index is up 150%.

- In Congress, several lawmakers likened a recent hearing – in which oil CEOs denied that their companies deceived the public on climate change – to the way tobacco executives said they didn’t believe nicotine was addictive in 1994. The House Oversight Committee followed up last month by issuing subpoenas for documents from the oil companies.

- At the close of a November climate summit in Scotland, parties to the Paris climate agreement issued a statement that for the first time named fossil fuels as a driver of global warming.

Inflation anxiety, starting at the gas pump

But then there’s the flip side of all this: ongoing public reliance on those fuels for heating homes, running factories, and especially powering transportation.

“Right now, I will do what needs to be done to reduce the price you pay at the pump,” President Joe Biden said at the White House on Nov. 23, as he announced an unusual move to release stockpiles from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Gasoline prices have surged this year as supply failed to keep pace with demand, contributing to wider inflation worries in a reviving economy.

The Biden administration said its temporary effort to ease pump prices needn’t conflict with the long-term goal of curbing greenhouse gas emissions. But at the very least, the current situation signals what could remain a difficult balancing act for years to come. Higher fuel prices are seen by many economists as a way to nudge consumers away from petroleum. Yet those same high prices can be a political millstone.

Gas prices have eased since Mr. Biden’s announcement last month, yet they remain nearly $1 per gallon higher than a year ago. And Mr. Biden’s favorability rating has sagged amid public concern about inflation and the pandemic, among other factors.

Ambivalence in public thought

Opinion polls reflect the tug and pull of competing priorities. Some 53% of Americans said they want less offshore oil drilling (versus 14% who wanted more, and 32% for no change), according to a 2019 opinion poll by The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Yet polls this year show high concern about gasoline prices. And worldwide, many see natural gas as an attractive energy source – it’s often called a “bridge fuel” for the transition toward cleaner energy. A 2020 Pew Research Center survey found that a median of 69% of adults in 20 nations favor expanding natural gas, compared with a median of 39% of adults in those countries who favor expanding oil.

Some experts say the era of decline for U.S. oil production has been underway for years.

“The real transition was in the 1970s,” says Tyler Priest, an associate professor at the University of Iowa who studies the history of oil and gas drilling. Since then, he says, the domestic oil industry “hasn’t been able to replace and add to their reserves in the way they had.”

It took the fracking boom since 2008, using hydraulic fracturing technology to reach hard-to-access reserves, to change that.

U.S. oil companies are “still in the technological vanguard,” Dr. Priest says. “They have the project management, the engineering, the geophysical expertise, and the long institutional history of doing major projects, like deep-water platforms. They still have the human resources and the technology that makes them important players.”

That, plus their installed base of production, suggests some staying power. Dr. Priest calculates that three large deep-water platforms in the Gulf of Mexico – Shell’s Appomattox and BP’s Thunder Horse and Atlantis – produce as much energy as 60,000 wind turbines covering 12,000 square miles.

Smooth energy transition? It’ll need investment.

As big as oil remains, many energy experts say a successful transition from the oil age toward clean energy is possible over the next couple of decades. But it will require deep investments and sustained commitment by both government and the private sector.

Already, one sign of the times is that renewable energy projects have much easier access to financing (a lower cost of capital) than oil projects, according to a recent report by Bloomberg Intelligence.

The Biden administration, meanwhile, has announced reforms that, while not banning oil leases on federal lands, would raise royalty rates to address what critics see as a tradition of hidden subsidies for drilling.

Even as the world underneath Big Oil shifts, Mr. Day sees little change in Texas City, where he recently joined a company as a full-time industrial mechanic. He’s not concerned about the industry’s future. He knows he’s proved his worth as a reliable, hardworking employee.

“You develop a general aspect of good work and good character, and people will call you back,” Mr. Day says of his faith in the industry. “It’s the drive and hard work ethic that keeps you working.”

France’s textile capital tries eco-friendly fashion to get back in style

Clothing choices can be a moral statement. Our reporter looks at the confluence of two consumer trends in France – buy local and reduce waste – which is spurring an eco-friendly textile revival.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For over a century, Hauts-de-France was the textile capital of France – until the jobs disappeared overseas. Today, it’s trying to reinvent itself as the country’s eco-friendly textile engine.

The push to reuse local materials and reduce waste is part of a larger phenomenon by French entrepreneurs to offer products that are made domestically. This past June, about 450 textile businesses joined forces to create the Textile Valley project, with the goal of bringing 1% of the country’s overall textile production back to Hauts-de-France, and with it, upwards of 4,000 jobs.

Their hope is to revitalize communities, boost the local economy, and help consumers think differently about how they shop.

And since September 2020, the French government has plugged 100 billion euros into relaunching the economy, with a third dedicated to relocating production back to France using more modern, sustainable practices.

“French people like these products because they’re original, but also because they make a positive impact and have a history,” says Hubert Motte, founder of upcycle clothier La Vie est Belt. “Especially since COVID, there’s a desire by French people to leave ‘fast fashion’ behind and buy products that are made locally.”

France’s textile capital tries eco-friendly fashion to get back in style

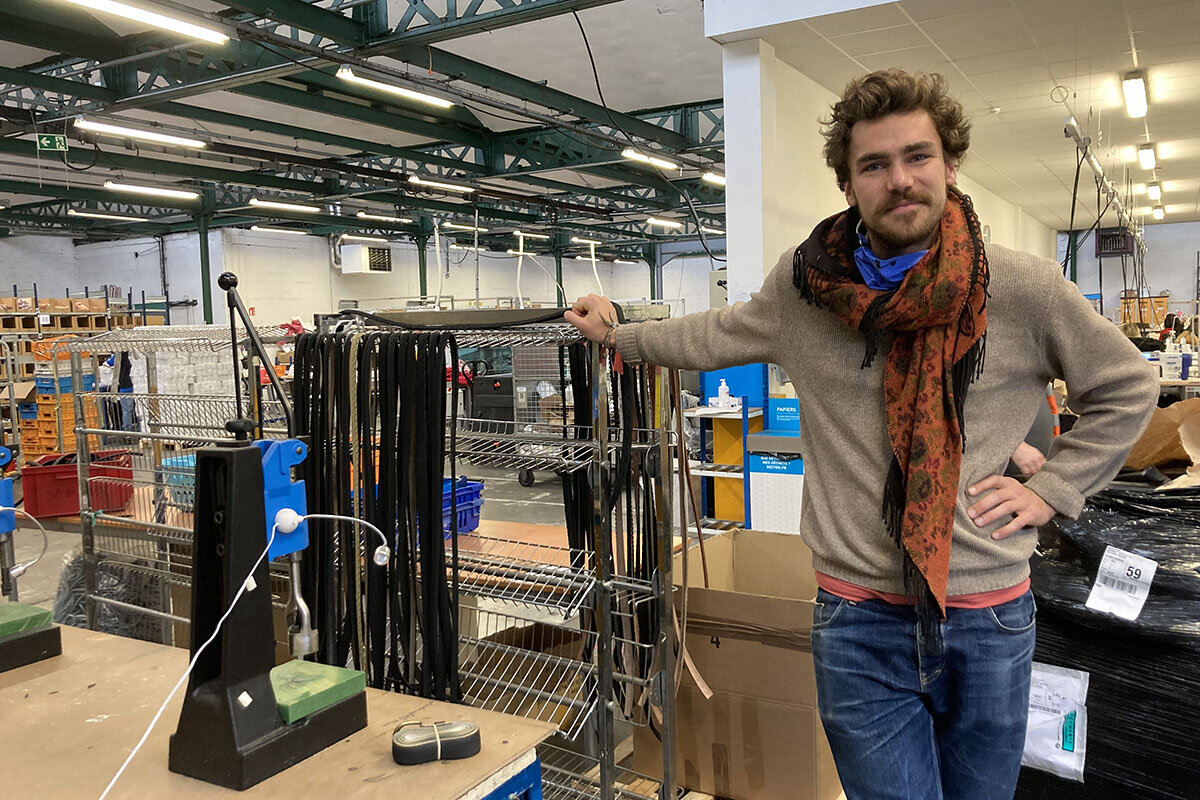

Strips of used, donated bicycle tires lie stacked in a pile on a flat work surface in a labyrinthine warehouse in this northern French town. Soon, the tires will be washed, perforated for buckles, and assembled into smart, sturdy belts.

They aren’t the only upcycled product created by La Vie est Belt. The textile company also takes used sheets to make men’s and women’s underwear, and even sells a DIY kit for customers to make their own undergarments.

“French people like these products because they’re original, but also because they make a positive impact and have a history,” says Hubert Motte, who founded La Vie est Belt in 2017 at the age of 23. “Especially since COVID, there’s a desire by French people to leave ‘fast fashion’ behind and buy products that are made locally.”

In doing so, Mr. Motte and his company are helping turn this region into a textile-recycling engine at a time when both eco-friendly clothes and buy local movements are growing – the latter by as much as 64%, according to recent polls. The effort draws on the local history of Hauts-de-France’s history, which for over a century was the textile capital of France.

The push to reuse local materials and reduce waste is part of a larger phenomenon by French entrepreneurs to offer products that are made domestically. This past June, around 450 textile businesses joined forces to create the Textile Valley project, with the goal of bringing 1% of the country’s overall textile production back to Hauts-de-France, and with it, upwards of 4,000 jobs.

In an industry that destroys between 10,000 and 20,000 tons of products each year in France, textile producers in Hauts-de-France are now leading the country in creating eco-friendly, locally made clothing and accessories. Their hope is to revitalize communities, boost the local economy, and help consumers think differently about how they shop.

“French consumers are transforming how they buy clothing, leaning towards zero waste and buying less,” says Annick Jéhanne, president of Fashion Green Hub, a community of 300 businesses and collectives dedicated to sustainable fashion based in neighboring Roubaix. “But major labels need to make their clothing more sustainable and provide eco-friendly alternatives so that, ultimately, the consumer can make better choices.”

“Using these leftover fabrics just made sense”

France’s textile industry can be traced as far back as the 14th century to northern towns like Tourcoing and Roubaix, known primarily for production of wool and lace. After taking a hit following World War I and II, the industry began to prosper by the early 1950s, becoming the largest economic driver for the region.

But as businesses began outsourcing production to plants overseas, the industry saw a steady decline by the 1960s. And by the 21st century, local textile production had almost completely disappeared. Today, Hauts-de-France suffers from a lack of skilled textile workers as well as one of the highest levels of unemployment in the country.

Charles-Henri Florin, the owner of Peucelle & Florin, a Roubaix-based wool business in operation for a century, had a front-row seat to the region’s change in fortunes. The company got its start producing high-end wool for major labels. But instead of following its competitors, which were outsourcing to Asia in the 1960s, Peucelle & Florin decided to change its business model – looking to Italy to import quality recycled wool.

“That allowed us to weather the storm, and also keep production in Europe,” says Mr. Florin from his sprawling stockroom, which houses thousands of fabric samples. “It’s important to be transparent. Everyone is thinking about their environmental footprint these days.”

Mr. Florin passed on his savoir-faire and appreciation for sustainability to his daughter, Héloïse Grimonprez, who founded her clothing label Edie Grim in 2015. The two are now in partnership, with Ms. Grimonprez buying up Peucelle & Florin’s unused fabrics to create chic, tailor-made coats and blazers.

“When I started the company, no one was using terms like ‘eco-friendly,’” says Ms. Grimonprez. “But using these leftover fabrics just made sense. They were just sitting there and I thought, ‘I need to do something with this.’”

The growing desire to know the source of clothing is not just for the upwardly mobile and looks to be more than a passing trend. Mainstream brands are looking for ways to make their labels more eco-friendly as well, handing over part of production to the region. And since September 2020, the French government has plugged 100 billion euros into relaunching the economy, with a third dedicated to relocating production back to France using more modern, sustainable practices.

Roubaix-based national retailers are increasingly committing to better practices. Clothier Camaïeu sends the entirety of its unsold women’s clothing to a local workshop to be upcycled by women facing joblessness, and fashion retailer La Redoute is creating a 100% eco-friendly men’s line and aiming to produce zero carbon emissions by 2030.

“It’s not a question of being trendy”

France’s next generation of designers looks set to carry the “made in France” concept beyond the trends, too. ESMOD, a private fashion school with branches across France, recently challenged students to create an eco-friendly clothing line to be produced by a local retailer. And degree programs in textile production, like the recently launched EPICC school – aimed at young people facing school difficulties – offer hope for the future of the industry here.

Entire neighborhoods in Tourcoing and Roubaix are now dedicated to new textile designers and producers, and several initiatives are working to boost manufacturing while also fighting exclusion.

The Projet Resilience – a network of 60 textile producers – has worked with those facing social or economic marginalization since March 2020 to teach basic sewing. The Atelier Agile has similar goals but on a smaller scale, planning to train about 30 people starting in January to produce small clothing series for new labels and capsule collections. And La Vie est Belt employs those living with disabilities, in partnership with social inclusion group AlterEos.

“Professors are asking us more and more to think about sustainability in our creations,” says Dune Girardot, who started working at Edie Grim after graduating from ESMOD last year. “It’s not a question of being trendy. It’s because it’s important.”

There are obstacles yet to overcome. The textile industry here is still recovering from having sent production overseas – it lost 530,000 jobs between 2006 and 2015, according to The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. As the desire for products made in France increases, the region has struggled to meet demand – both in materials and manpower.

But that demand shows that things are improving.

“I’m on back order. I’m waiting for more donations to come in so I can make my belts,” says Mr. Motte of La Vie est Belt. “It shows that things are changing. There’s definitely an energy here.”

Commentary

As Bangladesh turns 50, the secret to its progress: Educate girls

On the anniversary of Bangladesh’s birth as a nation, our commentator shares personal anecdotes and national statistics to illustrate his country’s progress – achievements based in part on a commitment to gender equity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Rezaul Karim Reza Correspondent

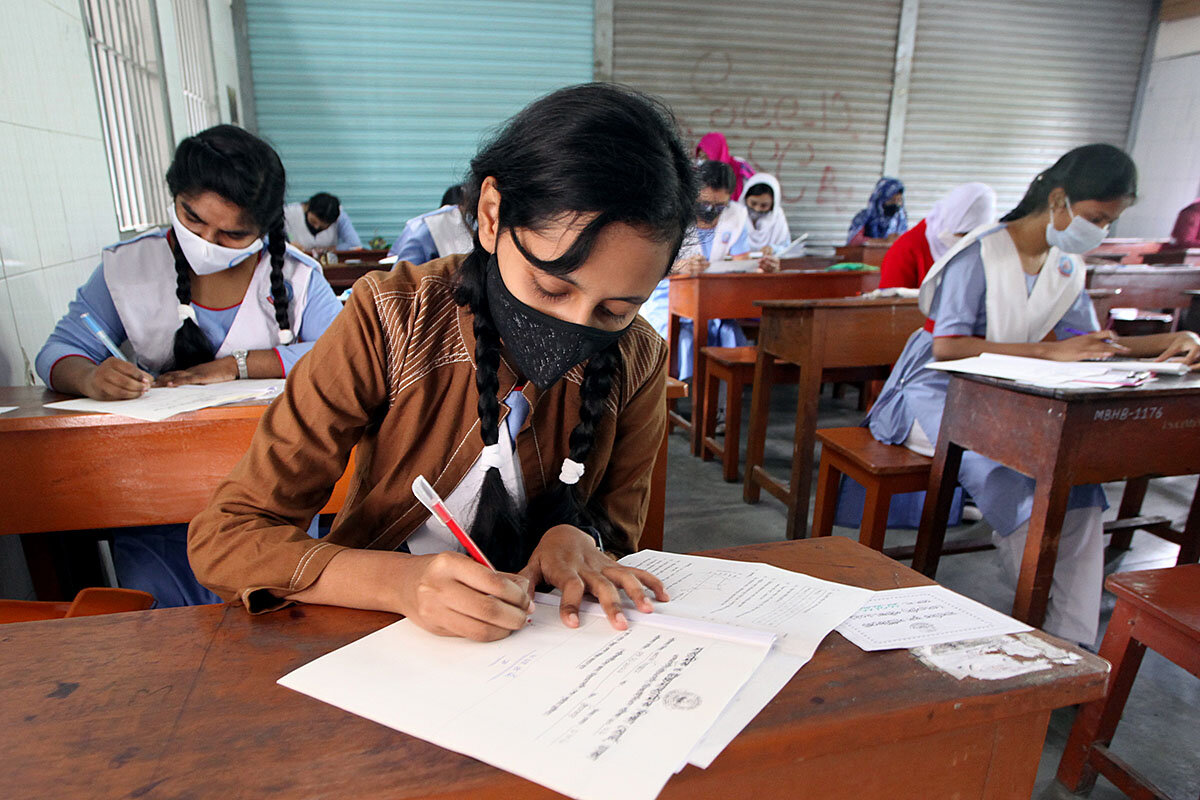

Brushing aside its critics, Bangladesh has emerged as an economic power in South Asia. Education has brought blessings to hundreds of thousands of people here. An emphasis on girls’ education has played an especially vital role.

As in developing countries around the world, so in Bangladesh, girls’ education has had a ripple effect, improving families, communities, and national economies.

In 1994, the country introduced the Female Secondary Stipend and Assistance Program to boost girls’ school attendance in rural areas. To receive the stipend and tuition subsidy, which supports more than 2 million girls a year, recipients must meet attendance and performance requirements and cannot marry before they finish secondary school. With the help of FSSAP, more girls than boys are now enrolled in secondary school. A next step is to increase girls’ grade-12 completion rate – which was only 59% in 2017 – so that higher education becomes an option for more of them.

I taught Jhorna, who asked that her last name not be used for cultural reasons, when she was in 10th grade. Now, she is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in English at Begum Rokeya University in Rangpur, with hopes of later studying abroad.

“I want to go to Canada for my master’s degree,” she told me recently.

As Bangladesh turns 50, the secret to its progress: Educate girls

Fifty years ago, President Richard Nixon was silent about the genocide of unarmed Bengali people at the hands of the Pakistani army. In the end, Bangladesh declared its independence. But the country was born into flood and famine, corruption and coups. Echoing another’s comment, Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s security adviser, called the country a “basket case.”

The situation was dire for decades. Twenty years ago, a pregnant woman from my village, struggling to reach the hospital, died in the middle of the journey because there were no vehicles or paved roads.

Today, it takes me only two minutes to get in an auto rickshaw and go to the nearby town from that same village. Apart from paved roads and motorized auto vans, we now have electricity and satellite connections. Residents can access the internet, schoolchildren have smartphones for taking online classes, and the community has a health care center right here in the village.

Brushing aside all the odds and criticism, Bangladesh has emerged as an economic power in South Asia. Education has brought blessings to hundreds of thousands of people here. An emphasis on girls’ education has played an especially vital role.

As in developing countries around the world, so in Bangladesh, girls’ education has had a ripple effect, improving families, communities, and national economies.

Shahana, who completed 10th grade, works in a garment factory. Her father is ill and unable to work much, so she is helping her family. In addition to sending money home, she’s building a brick house and plans to buy a piece of farmland in her village.

A reliable lever of progress

Bangladesh is not alone in reaping the rewards of educating girls, especially in secondary school (grades 6-12). Among the universal benefits, UNICEF notes lower child marriage and maternal mortality rates, healthier children, and “dramatically” increased lifetime earnings.

Measuring lost potential, the World Bank estimates that the “limited educational opportunities for girls and barriers to completing 12 years of education cost countries between [U.S.]$15 trillion and $30 trillion in lost lifetime productivity and earnings.”

On average, among the world’s least developed countries, the number of years girls spend in school has tripled over the last half-century, from 2.8 years in 1970 to 8.9 in 2017. The region making the most progress is South Asia, where girls went from spending 3.8 years in school to 12. Bangladesh is a big contributor to that progress.

In 1994, the country introduced the Female Secondary Stipend and Assistance Program to boost girls’ school attendance in rural areas. To receive the stipend and tuition subsidy, which supports more than 2 million girls a year, recipients must meet attendance and performance requirements and cannot marry before they finish secondary school. With the help of FSSAP, more girls than boys are now enrolled in secondary school. A next step is to increase girls’ grade-12 completion rate – which was only 59% in 2017 – so that higher education becomes an option for more of them.

“I want to go to Canada for my master’s degree,” Jhorna told me recently. (Both Shahana and Jhorna asked that their last names not be used for cultural reasons.) I taught Jhorna when she was in 10th grade. Now, she is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in English at Begum Rokeya University in Rangpur, with hopes of later studying abroad. There are thousands of other Jhornas, eager to receive higher education from foreign universities and then get respected work positions back home.

Other signs of advancement

Bangladesh’s economy also shows a strong upward trajectory. Per capita gross domestic product increased from $293 in 1991 to $1,968 in 2020, surpassing both India’s and Pakistan’s, according to World Bank data. That increase in GDP has significantly decreased the number of people living in poverty (based on the international poverty line), from 43.5% in 1991 to 18% in 2020.

That sharp decline in the poverty rate helped Bangladesh become a “lower middle-income” country in 2015, up from a “low-income” one. And the United Nations announced last month that Bangladesh will graduate from being a “least developed” country to a “developing” one in 2026.

I see evidence of that progress in my family and community. My father sold his labor for 10 hours a day, returning home with only 25 taka, which was less than 40 cents. Today, my brother sells the same amount of labor for about 500 taka, which is more than $5.

I know personally about a dozen families in northern Bangladesh who now have small farms and fisheries after receiving one of the millions of microcredit loans that Grameen Bank, a nongovernmental organization, has made to help lift people out of poverty.

“I have two cows now,” Rahim Badsha told me on an afternoon walk. Mr. Badsha is a peasant who once could not afford food for his family even twice a day. Now one of his cows is milking, after giving birth to a pretty little calf.

Bangladesh has plenty of work ahead to provide opportunity to people at all levels of society, but the country has made great progress in its 50 years of independence. We are not a basket case. We have much to celebrate on Dec. 16, Victory Day.

Rezaul Karim Reza is a substitute English teacher in Bangladesh and a freelance writer.

Books

Capping off the year with the 10 best books of December

Our 10 picks for this month include books that convey bravery in the midst of hardship, wonder at the beauty and fragility of nature, and curiosity over two enigmatic figures: screen star Greta Garbo and street photographer Vivian Maier.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Monitor reviewers

The mood in December can range from a festive holiday spirit to a quieter reflection as the year draws to a close. This month’s choices include evocative historical fiction set in Ecuador and Korea, a gentle fantasy about a cat who helps a young Japanese man save books, and a ricocheting novel with a choose-your-own-adventure ending.

Among the nonfiction titles are a collection of environmentalist Rachel Carson’s luminous writings, a riveting history of the thwarting of a post-9/11 terrorism plot, and a personal story about encountering the work of 17th-century poet John Milton.

Capping off the year with the 10 best books of December

The selections this month bring readers to armchair destinations and deeper insights. From sweeping historical novels to close-ups of colorful and sometimes prickly personalities, these are the books to keep you company this season.

1. Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim

Courtesans, opportunists, and occupiers cross paths in Juhea Kim’s rich sweep of a story. Set during the decades of Japan’s brutal takeover of Korea, the tale centers on best friends Jade and Lotus, as they grow up, apart, and into themselves amid dire circumstances. “People are brave in different ways,” affirms Jade’s lifelong admirer JungHo, a sentiment that infuses the book.

2. Where You Come From by Saša Stanišic

“Digression is my mode of writing,” declares the narrator of Saša Stanišic’s confident, careening novel. Bouncing between the present in the narrator’s adopted Germany and his recollections of childhood in pre-war Yugoslavia, the book packs in history, legend, and current events, plus a poignant choose-your-own-adventure ending.

3. The Cat Who Saved Books by Sosuke Natsukawa

This charming Japanese tale celebrates life and books through the transformation of a reclusive teenage boy named Rintaro. He’s been tasked with closing his grandfather’s bookshop, which has provided a refuge. When a talking tabby cat enlists Rintaro to help save books for humankind, the story highlights how courage, compassion, and connection to others brings rewards.

4. The Spanish Daughter by Lorena Hughes

Betrayal, secrets, and chocolate fuel this transporting page turner from Lorena Hughes. Puri, sporting a fake beard and her late husband’s suits, disembarks in Guayaquil, Ecuador, with sweaty palms and sundry purposes – disentangling an inheritance, tracking a murderer, and confronting siblings she’s never met. Set amid the early 20th-century cacao boom, the novel gently comments on the confines of gender, while asking if goodness is innate or learned.

5. Just Haven’t Met You Yet by Sophie Cousens

Sophie Cousens’ refreshingly kooky rom-com pokes mild fun at romantic daydreams. Laura, a lifestyle journalist in London, thinks she may have found The One in a handsome stranger who disappears with her suitcase on Jersey Island, where she’s researching her parents’ love story.

6. The Sea Trilogy by Rachel Carson

This gorgeous Library of America volume collects “Under the Sea-Wind,” “The Sea Around Us,” and “The Edge of the Sea,” in which the firebrand ecological whistleblower Rachel Carson shifts her narrative tone from warning to wonder, writing some of her most luminous prose about the strange, liminal space between the sea and the land – and the fragility of both.

7. Vivian Maier Developed by Ann Marks

Vivian Maier was posthumously hailed as one of the great 20th-century street photographers after her massive portfolio was discovered in an abandoned storage locker in Chicago. Ann Marks’ fascinating biography features Maier’s work and also explores why the enigmatic artist, who worked as a nanny for decades, never sought to share her photographs.

8. Garbo by Robert Gottlieb

In this entertaining biography, Robert Gottlieb assesses screen legend Greta Garbo’s film career with insight and wit while also exploring the enduring enigma of her early retirement and retreat from the public eye.

9. Disruption by Aki J. Peritz

During the summer of 2006, British security services, with the assistance of the CIA, foiled what would have been the most devastating terrorist attack since 9/11: an Al Qaeda plot to detonate bombs on seven commercial transatlantic flights. “Disruption” is Aki J. Peritz’s meticulous, riveting history of this plot, from the radicalization of the perpetrators to their sentencing in a British courtroom.

10. Making Darkness Light by Joe Moshenska

Oxford University professor Joe Moshenska traces the 17th-century English poet’s life but also reflects on the profound effect of Milton’s work on Moshenska’s own life as a reader and a scholar. This revelatory biography is inventive, erudite, and personal.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The right way to give away a fortune

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Pledging to give a fortune to charity should be seen as a noble endeavor. MacKenzie Scott wants to give away her entire wealth, estimated at $60 billion, as quickly as possible.

But like everyone else, wealthy people must make difficult decisions about which charities to support and why. Their choices can have outsize effects on the organizations they support as well as influence other potential donors.

Ms. Scott received a large chunk of Amazon stock as part of her divorce from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. In the last 18 months or so, she’s given away a remarkable $8.6 billion. Early on, she had been disclosing the recipients. But in a recent blog post, she announced she would no longer do that out of concern that it drew unnecessary attention to her, rather than the charities.

Critics say such disclosures represent necessary transparency and accountability. Mega-donors should explain why they make the decisions they make. In a subsequent blog post Ms. Scott seemed to have heard her critics, saying she’d post updates about her giving in the coming year.

Her apparent willingness to listen and grow can only increase the likelihood that those dollars will do the most possible good.

The right way to give away a fortune

Pledging to give a fortune to charity should be seen as a noble endeavor. MacKenzie Scott wants to give away her entire wealth, estimated at $60 billion or so, as quickly as possible.

Problems can arise when a mega-giver gets into the weeds of actually doing it. Like everyone else, wealthy people must make

difficult decisions about which charities to support and why. But their choices can have outsize effects on the financial health of the organizations they support as well as influence how other potential donors view those organizations.

Ms. Scott received a large chunk of Amazon stock as part of her divorce from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. In the last 18 months or so, she’s given away a remarkable $8.6 billion to a variety of charities.

She’s become one of the most generous billionaire philanthropists in history. She’s also signed the Giving Pledge, in which the ultrarich promise to give away most or all of their fortunes during their lifetimes. That group recently grew to 231 of the wealthiest people around the world.

Now her sudden emergence at or near the top of that list has raised questions about how philanthropy (Ms. Scott prefers to call it simply “giving”) should be done. Instead of setting up an official organization to oversee her gifts, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, she relies on an anonymous group of advisers.

Charities learn that they have received their unexpected windfall (sometimes the largest gift they’ve ever received) in a simple phone call. Spend the money any way you think best, they are told. No strings. No demands. We trust you.

Early on, Ms. Scott had been disclosing the recipients of her giving. But in a recent blog post, she announced she would no longer do that out of concern that it drew unnecessary attention to her, rather than the charities. She’d leave them to make their own announcements.

To her, it probably felt like a self-effacing move – perhaps showing modesty about giving away money she’d not earned herself.

But many who follow the world of big-time philanthropy have been troubled. Because Ms. Scott has set up no foundation, she’s not required by law to disclose her giving.

What is lost, these critics say, is the kind of transparency and accountability needed to assess what big donors are doing. Her high profile makes her a model for others.

Some donors might be interested in keeping their giving private but “without her noble intent,” Benjamin Soskis, who studies the history of philanthropy at the Urban Institute in Washington, told MarketWatch. Donations are tax deductible and thus of legitimate interest to other taxpayers. Like judges or lawmakers, critics say, mega-donors should explain why they made the decisions they made.

In a subsequent blog post Ms. Scott seemed to have heard her critics, saying she never intended to maintain a policy of total secrecy. She said she’d post updates about her giving in the coming year, along with a searchable database of the grants she has made. “My commitment to sharing information about my own giving has never wavered,” she wrote.

Ms. Scott’s apparent willingness to listen and grow as she learns how to best distribute her fortune can only increase the likelihood that those dollars will do the most possible good.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What’s filling your Christmas?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Stark

Whatever our plans at Christmastime may be, letting the spirit of Christ impel our thoughts and actions brings about greater patience, grace, strength, love, and joy.

What’s filling your Christmas?

Maybe you feel your Christmas is too full of activities or expectations after a scaled-down Christmas last year, or too full of questions about celebrating in the shadow of continued uncertainty. Or perhaps your holiday is not full enough, because you are waiting for an invitation to join friends or family.

Whatever the case, don’t we mostly need Christmas to be full of joy, full of the “on earth peace, good will toward men” (Luke 2:14) that was present at the birth of Christ Jesus? Without the grace that accompanies Christ, we aren’t really celebrating Christmas, and may be left feeling empty.

When I was a college student traveling abroad, I spent Christmas in a small city in the Andes. Christmas Day without family and familiar celebrations was lonely. As I walked the streets, I sang a hymn titled “Christmas Morn” to keep myself company. It’s about the birth of Jesus, and about the eternal Christ he embodied. The hymn is a setting of a poem by Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered and founded Christian Science. This heartfelt petition at the end of the poem became my prayer:

Fill us today

With all thou art – be thou our saint,

Our stay, alway.

(“Poems,” p. 29)

“What would being filled with Christ feel like?” I wondered. Surely being filled with Christ would mean experiencing what Christ Jesus, the Son of God, experienced – joy, for example, and affection, and the certainty of being loved by God.

As I opened my heart to God’s gift of Christ to the world, the loneliness left me. Christ filled me with a warm assurance that we are all the beloved children of God, always near and dear to our divine Father-Mother. I felt the love God has for all creation, including me and all the people of that city. Walking in a light rain, I was ready to feel at home with either friends or strangers, or even by myself.

Jesus was unique in his fulfillment of the biblical prophecies regarding Christ. But the Bible also says that God is Love, and Love’s supreme power – which gave Jesus victory over aloneness and rejection – is with each of us. “Of his fulness have all we received” says one Gospel writer (John 1:16).

The spirit of Christ that we receive is our spiritual awakening to what Jesus taught about God, our creator, as ever-present Love and Life. To be full of Christ, then, is to be conscious of our oneness with God.

In a public address, Mrs. Eddy said, “Jesus’ personality in the flesh, so far as material sense could discern it, was like that of other men; but Science exchanges this human concept of Jesus for the divine ideal, his spiritual individuality that reflected the Immanuel, or ‘God with us’” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 103). Jesus knew himself as the spiritual reflection of his Father, God, and he showed us our real identity as God’s man, as the purely spiritual reflection or activity of Love.

It’s all too easy to allow the holiday season to fill with self-criticism or harsh judgment of others. But as the Christ-spirit – the consciousness of being God’s loved sons and daughters – pervades our thinking and impels our actions, we are free to practice brotherly and sisterly love. You could say Christmas is full of opportunities to treat ourselves and others as divine Love’s own children, safe and whole. By doing so, we are growing into “the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13).

Our God-given nature is not a physical mind and body but our individual reflection of the fullness of God – our Christlikeness or unique expression of divine qualities, reflecting and glorifying God. Patience, for example, can help eliminate irritation within a family. Unselfishness stops fear, resentment, and fatigue. Meekness responds with grace to a change of plans. These spiritual qualities, and so many others, constitute the fullness of what we truly are as the image and likeness of Spirit, God.

When we think and act with any of the beautiful qualities that Jesus so fully lived, we will have a Christmas full of Christ. Christ continually assures us that we truly are the loved of divine Love and can feel Love’s presence wherever we are. Infinite Love leaves no one out of its tender embrace. How wonderful to know this is true this holiday, for us and for everyone we meet.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Dec. 13 & 20, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

A scenic ride

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: Our film critic, Peter Rainer, shares his list of the 10 best films of 2021.

Before you go, we have a quick point of clarification. Yesterday's article on Taiwan incorrectly identified Dennis V. Hickey's current role at Missouri State University. He is a professor emeritus.