- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A lesson in tornadoes’ wake: Warnings work, but human response is key

- Did deal ending Sudan coup leave Sudanese out of the picture?

- Time to be clear on Taiwan? ‘Strategic ambiguity’ faces test.

- Can expats be lured back? Why these Latvians are coming home.

- For designer William Morris, beauty was key to happiness

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Rethinking PTSD: Resilience is more common than we think

On a December night over a decade ago, a young New Yorker named Jed McGiffin was run over by a garbage truck. Prior to the first of many surgeries, including an amputation, Jed tried to calm his weeping girlfriend, Megan. “I’ll see you on the other side,” he reassured her, surprising himself with his own calm.

“He’s not a superhuman person. He wondered, ‘Why am I OK?’” says George Bonanno, who recounts Jed’s story in his new book, “The End of Trauma: How the New Science of Resilience Is Changing How We Think About PTSD.” “He had the same question we all did, ‘Why would I be resilient in this thing?’”

Trauma has become a modern buzzword. But decades of research incontrovertibly reveal that most people who experience violent and life-threatening events do not develop post-traumatic stress disorder, says the professor of clinical psychology at Teachers College, Columbia University. For example, New York City officials braced for widespread trauma following Sept. 11, 2001. But six months later, the number of Manhattanites who experienced PTSD was less than 1%. “The End of Trauma” features case studies of individuals who’ve endured horrific circumstances. Resilience isn’t a rare human trait, he says in a phone interview, but it helps to have a flexible mindset to adapt to challenges.

As for Jed? After obtaining a Ph.D. under Mr. Bonanno’s tutelage – and starting a family with his now-wife Megan – he still suffered great pain. Yet Jed gained insights into how a sense of optimism was key to his reinvention. Now he counsels other injury survivors.

“He had put his life back on track,” writes Mr. Bonanno in his book. “He knew, from that point forward, that whatever happened next, he would always be able to find a way to come out on the other side.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A lesson in tornadoes’ wake: Warnings work, but human response is key

Rare and unusually strong December tornadoes in Kentucky have put a focus on safety. Warning systems have improved greatly in recent years – partly due to heart-to-heart clarity in language.

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

Severe tornadoes killed at least 87 people on a path through four states Friday, but the destruction did not come without warning. At the National Weather Service office in Paducah, Kentucky, Michael York began sending out alerts midweek about the gathering of a powerful storm.

Increasingly well-targeted cellphone alerts, meanwhile, told people to shelter when they were in the storm’s possible path on Friday evening.

Such steps made a big difference. On Friday, Sarah Stewart and her staff at ClearView Health Care Management in Kentucky spent much of the day guiding preparations. One of the company’s seven facilities took a direct hit. There were close to 100 people, including 74 residents, in the building. Through steps such as moving people into hallways, and by what she calls a miracle, none were hurt.

What Ms. Stewart vividly remembers is the tone of the weather forecaster cutting through any question of false alarms.

“Twenty years ago, we thought the public was pretty ignorant [about weather risks], and what we have learned in the last five years is that they know way more than we expect,” says Stephen Strader, a hazards geographer at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. “People know that they’re not in a safe location, but they don’t know what to do about it.”

A lesson in tornadoes’ wake: Warnings work, but human response is key

As huge air masses began to collide last week over the central United States, Michael York, a veteran meteorologist, focused on the data swirling in front of him.

His face lit by screens at a cookie-cutter National Weather Service office in Paducah, Kentucky, Mr. York began sending out alerts midweek about the gathering of a powerful storm.

Finally, as the NWS radar caught the storm spinning off a twister on Friday, Mr. York’s office sent out a plain-spoken plea at 8:33 p.m. to take shelter: “Folks, this is as serious as it gets.”

Thirty miles to the south, in Mayfield, Kentucky, machine shop owner Phil Crowfoot’s weather radio had been blaring since 6 o’clock. He knew the NWS predictions weren’t always perfect. “They’re good about missing snowstorms and stuff. I was hoping this was going to be one of them, too,” says Mr. Crowfoot. Yet he made plans to shelter.

“When it started going off all the time, I thought maybe this was real. It was hitting everything around us. ... I was saying a prayer when it was going by.”

The rare December tornado – the strongest of several in the region Friday – spun up in Arkansas, raged through the Land Between the Lakes and across the rolling hills of western Kentucky on a 220-mile path. When the tornado reached Mayfield around 9:30 p.m., it leveled much of the town. In all, the storms killed at least 87 people in four states, and injured scores of others.

In its aftermath, questions are being raised about why a litany of warnings didn’t quell a still-building death toll. There are stark critiques of how companies like Amazon and a maker of votive candles handled safety concerns as the storms bore down. And, as President Joe Biden prepares to visit Kentucky Wednesday, the role of climate change is being discussed as a possible factor in the unusual weather conditions that contributed to the tornadoes’ severity.

But the connection between Mr. York and Mr. Crowfoot on Friday highlights hope as well. Warnings were abundant, and they were widely heeded. Even as the fatalities put a focus on how to improve public safety, advances in pre-storm communication likely saved many lives on Friday, hazard researchers say.

Beyond improvements in atmospheric science and the rise of cellphone-based alerts in recent decades, the shift also includes language itself – as forecasters employ phrasing shorn of jargon and pretense to help people understand urgent threats and what they can do in response.

“Weather forecasting in general is moving very strongly towards not just making the forecast, but making sure that those forecasts are actionable – that people are understanding the context,” says Paul Roebber, co-author of “Minding the Weather: How Expert Forecasters Think.”

In at least some ways, the tornadoes that ripped through Kentucky will be a measuring stick for that effort.

The deadliest tornado in the U.S. happened in 1925, when at least 695 people died in the Tri-State Tornado, which also affected Kentucky along with other Midwestern states.

Beyond technology: how to affect behavior

Advances in alerts since then, from cellphones to local news, have resulted in greater weather awareness among Americans. That is apparent even in news reports about how employers and workers argued about the need to protect themselves as the storms gathered.

Potential preparation missteps are the reason researchers say debates about technology and climate change are insufficient to safeguard Americans. In fact, forecasters are focusing increasingly on understanding human behavior to counter growing vulnerabilities from population growth in regions of turbulent weather.

“Twenty years ago, we thought the public was pretty ignorant [about weather risks], and what we have learned in the last five years is that they know way more than we expect,” says Stephen Strader, a hazards geographer at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. “People know that they’re not in a safe location, but they don’t know what to do about it, and that’s always scary. Where do we go? It’s fight or flight, and 9 times out of 10 they’re going to choose fight.”

Some 70% of tornado warnings are false alarms – long an acceptable threshold for forecasters who want to give people as much lead time as possible.

That tactic took a turn in 2011. On April 27 that year, a tornado outbreak caused 316 deaths, primarily in Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. It was the costliest on record and deadliest since the 1925 Tri-State Tornado.

Partly due to concerns that residents didn’t take warnings seriously, average warning lead times have dropped from 15 to 11 minutes in the U.S. – a shift prompted by efforts to target warnings more accurately so that fewer false alarms go out.

“You could hear ... that he was scared”

Still, early and more general warnings also make a difference. On Friday, Sarah Stewart, regional director of operations for ClearView Health Care Management in Kentucky, discussed the coming storm at the staff Christmas party. She and her staff spent the rest of the day guiding preparations. One of the company’s seven facilities took a direct hit. There were close to 100 people, including 74 residents, in the building. Through steps such as moving people into hallways, and by what she calls a miracle, none were hurt.

What Ms. Stewart vividly remembers is the tone of the weather forecaster cutting through any question of false alarms.

“You could hear in his voice that he was scared, that he was nervous. He’s like, ‘If you are in Mayfield, you need to put a helmet on. You need to get wherever you can get and you need to pray.’ In the world that we live in right now ... when a weatherman is telling you to pray, he is concerned about your welfare.”

The sparsely populated West and Plains still see the bulk of the classic “Wizard of Oz” tornadoes – funnels dancing on the landscape.

The Kentucky tornadoes are part of an eastward shift in the threat, in which violent, fast-moving tornadoes tear through suburban subdivisions, often under the cover of night, cloaked in rain.

Reaching people amid stresses of life

Social and economic marginalization also plays a role in preparations in places like Mayfield, a town of 10,000 where 1 in 3 residents lives below the poverty line.

That dynamic highlights the “physical and societal elements that come together when violent tornadoes upend complete towns and kill dozens,” says Professor Strader.

That was the challenge that Mr. York faced. It began with a message on Friday morning.

“No graphics with this post. Just straight from the office,” the Paducah NWS office posted at 10:19 a.m. on Friday. “This could be a significant severe event with a strong tornado or two across our region. Think about what you would do now. Better to err on the safe side.”

In many ways, the natural cadences are an acknowledgement, disaster experts say, that meteorologists like Mr. York are learning unique skills on the job. The new federal infrastructure package includes funds to study the role of social science in saving lives during a natural disaster.

Part of that evolution is that forecasters, too, are themselves often in the path of danger.

After sending out the “tornado emergency” warnings, the Paducah office went dark as the storm knocked out power and a backup generator failed. The Springfield, Illinois, NWS office took over until power came back on

“Forecasters are human beings who are at risk and whose families are at risk as much as the people they are warning for,” says Dr. Roebber, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee meteorologist. “But they are professionals. ... They are not going to let their emotions get the better of them. They’re not going to panic. They’re going to try to figure out how to get this across to people to protect as many people as possible.”

Looking back on last week, Mr. York says that perceptions about their role varies among his colleagues.

“We all have different personalities, different ways of reacting, but for me it’s a very professional-type thing where I just focus more on the science and how [the weather] is going to impact people as far as potential damage or disruption to their lives,” says Mr. York. “I try to put that into nontechnical terms that they can understand.”

Some forecasters, he says, take solace in the knowledge that their work saves lives. Mr. York’s approach includes a hard look at how his office performed. The lives lost, for him, are a reminder of a distance still to go.

“I’m critical. I want to be perfect,” he says. “The problem is, we’re dealing with the weather.”

Reporting for this article was done by Patrik Jonsson in Savannah, Georgia, and Noah Robertson in Alexandria, Virginia.

Did deal ending Sudan coup leave Sudanese out of the picture?

Perspective matters. Viewed from outside, the peaceful restoration of a civilian prime minister in Sudan was a diplomatic triumph. But on Sudan’s streets, protesters say their voices still aren’t being heard.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For weeks Sudanese protesters demanded an end to a military coup and the release of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. Now, despite a coup-ending deal that was hailed as a victory by the international community, protesters have swiftly turned against Mr. Hamdok for conceding too much to the military.

It is part of a boiling over of frustration that the international community, in its pursuit of compromise and diplomacy, has shut average Sudanese out of the transition away from dictatorship, which they say is moving too slowly.

Since the overthrow of dictator Omar al-Bashir, the international community has worked with decades-old political parties, technocrats, and the military. However, critics say the West has overlooked the people who powered the revolution.

“At the root of all this is the fact that not the international community, nor the military, nor the political elites in Khartoum reach out to these youth groups, women’s groups, and resistance committees that have been the drivers of political change,” says Kholood Khair, manager of a Khartoum think tank that provides transition policy advice.

“There is a massive disconnect. The whole transition is predicated on a superficial analysis that doesn’t take into account where the real politics happen – on the ground.”

Did deal ending Sudan coup leave Sudanese out of the picture?

It was Ahmed’s sixth protest in six weeks.

Despite the risks from the military’s deadly crackdown on demonstrations, the unemployed Sudanese university graduate says he had nothing to lose.

“There is no going back,” the 20-something says from Khartoum, Sudan, while participating in nationwide protests Monday.

“No to negotiations, no to collaboration with the military, yes to revolution,” he adds. “Either we achieve a full, civilian democracy right now, or we die an oppressed people.”

The international community is hailing the Nov. 21 deal that ended a nearly monthlong military coup that threatened the country’s steps toward democracy. But Sudanese protesters like Ahmed who demanded the release of civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok now blame him for making too many concessions.

It is part of a boiling over of frustration on the Sudanese streets that the international community, in its pursuit of compromise and diplomacy, has shut average Sudanese out of Sudan’s transition away from dictatorship, which they say is moving too slowly.

Since the overthrow of dictator Omar al-Bashir, the international community has worked with decades-old political parties, technocrats, and the military. However, critics say the West has overlooked the grassroots activists and average Sudanese who powered the revolution.

These consist of loosely organized self-declared resistance committees, student unions, women’s groups, and networks of young activists organizing at the neighborhood level, whom observers say Sudanese politicians, the military, and the international community have struggled to communicate with and comprehend.

“At the root of all this is the fact that not the international community, nor the military, nor the political elites in Khartoum reach out to these youth groups, women’s groups, and resistance committees that have been the drivers of political change,” says Kholood Khair, manager of Insight Strategy Partners, a think-and-do-tank in Khartoum that provides transition policy advice.

“They just don’t speak to them; there is a massive disconnect. The whole transition is predicated on a superficial analysis that doesn’t take into account where the real politics happen – on the ground.”

Distrust of military

Amid alarm bells that authoritarian forces are slowly hijacking Sudan’s democracy before it even begins, grassroots pressure is building for an immediate end to military rule.

The armed forces, many Sudanese insist, cannot be trusted.

As part of a 2019 deal brokered by the United Nations and United States following Mr. Bashir’s ouster, civilian and military officials ruled Sudan jointly in an uneasy partnership.

Prime Minister Hamdok and Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, commander in chief of Sudan’s armed forces, governed under a civilian-military Sovereign Council to steer the country’s transition to democracy. That is, until an Oct. 25 coup by General Burhan, when the military placed Mr. Hamdok and his Cabinet under arrest.

After a month of nationwide protests, on Nov. 21, Mr. Hamdok signed an agreement with the military ending the coup and restoring the civilian Cabinet.

But in what many Sudanese describe as a “reward” for the coup, the deal also stripped away most of the civilians’ powers and increased the military’s authority.

Sudanese, including the Sudanese Professional Associations, unionists who helped mobilize the 2019 revolution, immediately protested what they described as a “betrayal” and a “legitimizing of the coup.”

Swift change in mood

As the deal was announced, protesters who moments earlier were singing songs in the streets demanding Mr. Hamdok’s freedom, immediately crossed out his photos and chanted against him.

“The Sudanese people refuse this political agreement because it solidifies the military’s powers it seized in the Oct. 25 coup and will not lead to a civilian democracy,” says Mohammed al-Noor, a resistance committee organizer.

“This is not a transition to democracy. From a legal and rights perspective, the situation today is much worse for the Sudanese people.”

The new agreement delays until 2023 General Burhan’s handing over the chair of the Sovereign Council to a civilian from the original date of Nov. 17, 2021.

Unlike the original post-revolution agreement, the new pact calls for elections but does not give a specified date for a handover to a full civilian government, a concession that critics say opens the door for the military to rule indefinitely.

“The nationwide protests after the coup were never for Hamdok as a person – they were hoping Hamdok would maintain his position refusing to negotiate with the military until protests succeeded in pressing Burhan and the military officers to resign,” says Jihad Mashamoun, a Sudanese political analyst.

“People’s protests were focused on encouraging a counter-coup against Burhan and the officers to establish a full civilian government, not for a return to the status quo. This is less than even that.”

Yet the international community has held up the agreement and the return of Mr. Hamdok from house arrest to the prime minister’s office as a success, urging Sudanese to accept the agreement.

“I think the calling into question this particular solution, even if I do understand why people are outraged, would be very dangerous for Sudan,” U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres cautioned in a joint U.N.-African Union press conference Dec. 1, calling on “the people of Sudan to support Prime Minister Hamdok over the next stages so we can have a peaceful transition towards a true democracy.”

Mr. Guterres and many Western diplomats fear that confrontation between the military, its allied militias, and civilians could ignite widespread violence that would unravel a year-old peace among warring groups and plunge the country into civil war. With neighboring Ethiopia embroiled in war, they worry further armed conflict could ignite the entire horn.

In response, dozens of Sudanese protested in front of the office of the U.N. Mission to Sudan in Khartoum last week, holding signs in English and Arabic reading “the Nov. 21 agreement is not a democratic transition” and “the military coup doesn’t represent our goals!”

Return of the regime?

Driving Sudanese rejection of the military’s role in their transition is what they describe as a creeping return of the Bashir regime, itself a military-Islamist dictatorship, through legitimate and illegitimate means.

General Burhan was appointed by Mr. Bashir as military commander in 2018, and several senior officers involved in the transition have ties to the deposed regime.

In the post-coup agreement with Mr. Hamdok, General Burhan appointed two figures from the former regime to the 11-member Sovereign Council.

While civilians serve as ministers, the military has spent months stacking the government bureaucracy, filling undersecretaries and senior positions with former regime figures in the ministries of justice, foreign affairs, education, regional governments, and state banks, sparking multiple protests this summer.

Activists say militias have killed hundreds of protesters with impunity since the 2019 revolution and 40 since the Oct. 25 coup.

They highlight the arrest of members of the Empowerment Removal Committee, a task force established to track down stolen assets and remove Bashir loyalists from state institutions.

Then there is the military conducting its own foreign policy, meeting frequently with officials from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel, sparking concerns it is forming regional alliances to cement its power.

“In Sudan, for 52 of the last 60 years we have lived under military dictatorships,” says Dalia Eltahir, a journalist and presenter for Omdurman TV network. “We know what it looks like, and we refuse to return back after we have paid such a heavy price.

“We Sudanese are convinced that foreigners always see working with the military as better than democracies, and that Africans can only be ruled by dictatorships,” she says. “Their recent actions support this, but we push on in spite of them.”

Adds Mr. Noor, the resistance organizer: “In reality, the continuation of military and militia rule will hurt stability, it will make people give up hope, lose their sense of security, migrate for alternatives.

“All we ask the international community is not to look only at short-term violence, but consider the long-term stability of a country where the democratic rights of the people are upheld.”

Time to be clear on Taiwan? ‘Strategic ambiguity’ faces test.

For 40 years, Washington’s policy of strategic ambiguity has helped deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. As Beijing ramps up its rhetoric, is that subtle diplomatic posture still fit for purpose?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

When President Joe Biden told a CNN town hall meeting in October that Washington had a commitment to defend Taiwan should China try to invade the island, it did not take long for the White House to issue a clarification. Official U.S. policy remains “strategic ambiguity,” which means uncertainty.

For 40 years that has meant Beijing has assumed Washington would fight for Taiwan, and thus concluded that using force would be unwise. And it has deterred Taiwan from declaring independence because the island state could not be sure of U.S. backing.

Now some in Congress think it’s time to come off the fence and make it clear to China that the United States would defend Taiwan, so as to present a more active deterrent. That’s because Chinese leader Xi Jinping has stepped up his rhetoric and said he would like to see “reunification” with Taiwan while he is in office.

But most China pundits disagree, seeing value in strategic ambiguity.

“You’re taking a policy that has worked well, and deterred both sides from making trouble for decades, and you’re going to change that,” says Dennis V. Hickey, a professor emeritus at Missouri State University. “I think that’s pretty risky.”

Time to be clear on Taiwan? ‘Strategic ambiguity’ faces test.

At a CNN town hall in late October, President Joe Biden was asked whether the United States would defend Taiwan if China attempted an invasion. His answer was simple.

“Yes, we have a commitment to do that,” the president said.

But official U.S. policy is a good deal less clear, as the White House clarified immediately afterward. That’s deliberate. For more than 40 years, the U.S. has adopted a position of “strategic ambiguity” toward Taiwan. The stance has helped keep the peace so far, but as China grows more powerful and more aggressive, some in Congress wonder whether the policy is obsolete.

What is strategic ambiguity?

It’s a guessing game. Officially, the U.S. won’t commit to defending or discarding Taiwan during any invasion by China.

“We do not say that we will come to Taiwan’s defense, and we don’t say that we won’t come to Taiwan’s defense,” says David Sacks, a research fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

How did it become U.S. policy?

During the Chinese Civil War, the United States backed the losing side, the Nationalists, who fled to Taiwan and set up the Republic of China there.

Mao Zedong repeatedly threatened to “liberate” Taiwan and bombed islands off its coast. Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek wanted U.S. support to “rescue” the mainland.

Meanwhile, the U.S. wanted to avoid war, says Dennis V. Hickey, a professor emeritus* at Missouri State University. America didn’t help Chiang attack the mainland, but it did sign a mutual defense treaty with Taiwan in 1954.

That treaty lapsed in 1979, when the U.S. switched its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the Communist government in Beijing, and Congress enacted the Taiwan Relations Act. Strategic ambiguity was born.

The U.S. has two obligations to Taiwan under the Taiwan Relations Act: to sell it arms and to maintain the capacity to protect the island. In essence, it doesn’t have to defend Taiwan, but it can.

“The assumption is that China will continue to assume that the United States will come to Taiwan’s defense and it will plan accordingly. Given that variable, China will continue to decide that force is not its best bet,” says Mr. Sacks.

At the same time, the ambiguity deterred Taiwan from declaring independence, which would have angered China, and risked a war without U.S. support.

Why do some in Congress want it to end?

Strategic ambiguity has kept the peace so far, but a smattering of voices on both sides of the aisle on Capitol Hill, including Republican Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, think that a clearer U.S. commitment to Taiwan would work better in the future. “I think that removing the ambiguity would be good,” Senator Tillis said recently at Politico’s Defense Forum.

He and some of his colleagues believe U.S. policy should be a more active deterrent, given that an increasingly powerful China is running more and more military exercises in Taiwan’s airspace and has grown more aggressive in its rhetoric.

“In the past, Chinese leaders have said that they would engage in strategic patience, and they didn’t have a timeline for reuniting Taiwan with the mainland,” says Peter Mansoor, chair in military history at The Ohio State University.

But not Xi Jinping. The Chinese leader has said he wants reunification while he is in office, and China’s growing military prowess raises the chances he might try to achieve that.

The U.S. has three options, says Professor Mansoor. The least likely is that it could leave Taiwan on its own. Or Washington could officially commit to defending Taiwan, and risk involvement in a war. Or it could continue with strategic ambiguity.

Professors Mansoor and Hickey support the third path, increasing arms sales, cooperating with local allies, and training Taiwan’s military. The Taiwan Strait may be especially tense now, says Professor Hickey, but it’s been worse before. Relations there are fragile, he points out, and require careful management.

“You’re taking a policy that has worked well, and deterred both sides from making trouble for decades, and you’re going to change that,” says Professor Hickey. “I think that’s pretty risky.”

Editor's note: This article has been updated Dennis V. Hickey's current status at Missouri State University. He is a professor emeritus.

Can expats be lured back? Why these Latvians are coming home.

Like much of Eastern Europe, Latvia has seen many of its younger citizens leave to work abroad. A variety of reasons – including sentiment – are drawing some of them back to their homeland.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Latvia has a severe population decline problem, one of the worst in Europe. The country has seen its population decrease more than 20% since 2000, to 1.9 million today: the combined result of a rapidly aging population, too few births, and international migration.

So the government is trying to woo those who left back home. And whether it’s due to the pitch of remigration counselors, the promise of telecommuting from their motherland, or the simple lure of family and nostalgia, Latvian emigrants are coming back.

People are moving back for a variety of reasons, says Elita Gavele, the Latvian ambassador-at-large for diaspora affairs. “Some are returning because they want their children to study at Latvian schools. Others are coming back to buy an apartment or upgrade their living conditions.”

Sentiment is a major factor, if not the decisive one, among the latest wave of Latvian repatriates. Maija Hartmane moved to Britain with her parents in 2007 but returned in 2018. “It was never really about moving back, per se,” she says. “All my school summer holidays were spent here. My entire family lived in Latvia, and I felt that this was where I belonged.”

Can expats be lured back? Why these Latvians are coming home.

Elina Zelcha thought she was doing well when she moved from Baltinava, a small village near the Latvia-Russia border, to Hamburg, Germany, in 2018. But something nagged at her.

“Returning home was a call from within, a whisper in my ear,” says the tattoo artist, describing the epiphany she had later. “‘You were born in Latvia for a reason.’” She decided to listen and head home to Latgale, Latvia’s easternmost province.

Latvia is hoping that other emigrants will follow Ms. Zelcha’s lead. The small Baltic nation has a severe population decline problem, one of the worst in Europe. The country has seen its population decrease more than 20% since 2000, to 1.9 million today: the combined result of a rapidly aging population, too few births, and international migration.

So the government is stepping up its efforts to bring them back. And whether it’s due to the pitch of remigration counselors, the promise of telecommuting from their motherland, or the simple lure of family and nostalgia, Latvian emigrants are coming back home.

“We need our people,” says Elita Gavele, the Latvian ambassador-at-large for diaspora affairs. “We want them to come back.”

The lure of home

According to the government, nearly 3,000 people have returned to Latvia over the last three years, mainly from Scandinavia, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Ireland, while 650 other families have indicated that they are planning to do the same.

The returnees are coming back for a variety of reasons, according to Ms. Gavele. “Some are coming back because they want their children to study at Latvian schools. Others are coming back to buy an apartment or upgrade their living conditions.”

“Others are returning to start a new business based on an idea they developed and wish to try out in their homeland,” she says. “And of course then there are those who miss their family.”

Sentiment is a major factor, if not the only one, propelling the latest wave of Latvian repatriates home. Such is the case for Maija Hartmane. She moved to the U.K., the most popular destination for Latvian emigrants, with her parents in 2007 at the beginning of the Great Recession, but returned in 2018.

“It was never really about moving back, per se,” says Ms. Hartmane, who now manages a guesthouse in Rāzna National Park near Rēzekne. “All my school summer holidays were spent here. My entire family lived in Latvia, and I felt that this was where I belonged.”

The young hospitality worker “always” intended to come back, she says. Besides, she adds, “I never really ‘fit’ into British culture, although I did make some very good friends there.”

Leeds, where her family settled in England, was too “big,” she says. So is the Latvian capital of Riga, for that matter. “I wanted to get back to the countryside and fresh air. So here I am.” Referring to the seclusion of Latgale and the park where she works and lives, she adds, ”This is where my soul belongs.”

Ms. Hartmane gives Astrida Lescinska, the remigration counselor for the Latgale planning region, considerable credit for helping her decide to return. A remigrant herself who had moved to the U.K. as a teenager in 2012, Ms. Lescinska now works to contact potential returnees and create a plan for them to move back to Latvia.

“One of the major challenges of my job is to tell them what Latvia is like today,” says Ms. Lescinska, who is based in Daugavpils, Latgale’s largest city. Many potential returnees are not familiar with how much Latvia has changed, or how much the economy has improved, she says.

“Most emigrants, I find, want to come home,” she says. “They just need a little push – and to know that there is someone there to assist them and to continue to make them feel at home after they do return.”

“Our regional coordinators are actively and relentlessly working in helping our citizens to move back to Latvia,” says Artūrs Toms Plešs, the minister for environmental protection and regional development, which oversees the accelerated remigration campaign. “I believe that the pandemic has played a role, too. Now that people know that they can work remotely, some see that as a productive way to return.”

“A complex decision”

Ms. Zelcha, the tattoo artist who returned to Baltinava in April of this year, works with Ms. Lescinska to encourage other potential remigrants. “I am glad that I moved away,” she says. “Moving away gave me a new understanding of my society and my village.”

“I saw the opportunities it offered, which I hadn’t seen before. Also, I received a lot of support for my hand-poke tattooing business, which is something that is very rare in our country.”

Latvia has changed, and for the better, she says, “but the biggest change for me was internal,” and the way she perceives and appreciates things she hadn’t necessarily appreciated before, like the sublime “calmness” of her village.

For all the remigrant success stories, there are those who feel that the Latvian government could do even more to ease their return.

“I think the government could also allow returnees not to pay taxes for the first year, the way that Canada and Portugal do,” says Liene Ozolina, a sociologist who returned to Latvia with her American husband and young son last year after living for 10 years in London. “I think that this would be a real way for Latvia to incentivize its citizens to return.”

“But,” she adds, “even that in itself would not be the driving force for someone to return.”

The process of re-acclimating to Latvia has not been without its bumps, says Dr. Ozolina, who now lives in Riga, where she teaches at the Latvian Academy of Culture. There have been shocks, particularly the difference between English and Latvian manners. She does not deny that she misses the former. “People are less kind and gracious in public,” she says. “That can hurt. In London, the form is that if you step on someone’s foot you automatically say ‘sorry.’ Not here, I am afraid.”

“The roughness and incivility of the Soviet days dies hard,” she adds, referring to the half-century-long Russian occupation of the Baltic nation, which ended 30 years ago. “You can still feel the trauma of that time.”

Nevertheless, she and her husband are happy with their decision to move back to Latvia. “Returning home is a complex decision with its own emotional and rational dimensions,” says Dr. Ozolina. “What matters is how it feels to be back in a place where you have your childhood friends and your relatives. These were the things which ultimately carried the most weight in my decision to return home.”

“In the end, it was the right decision for me.”

Book review

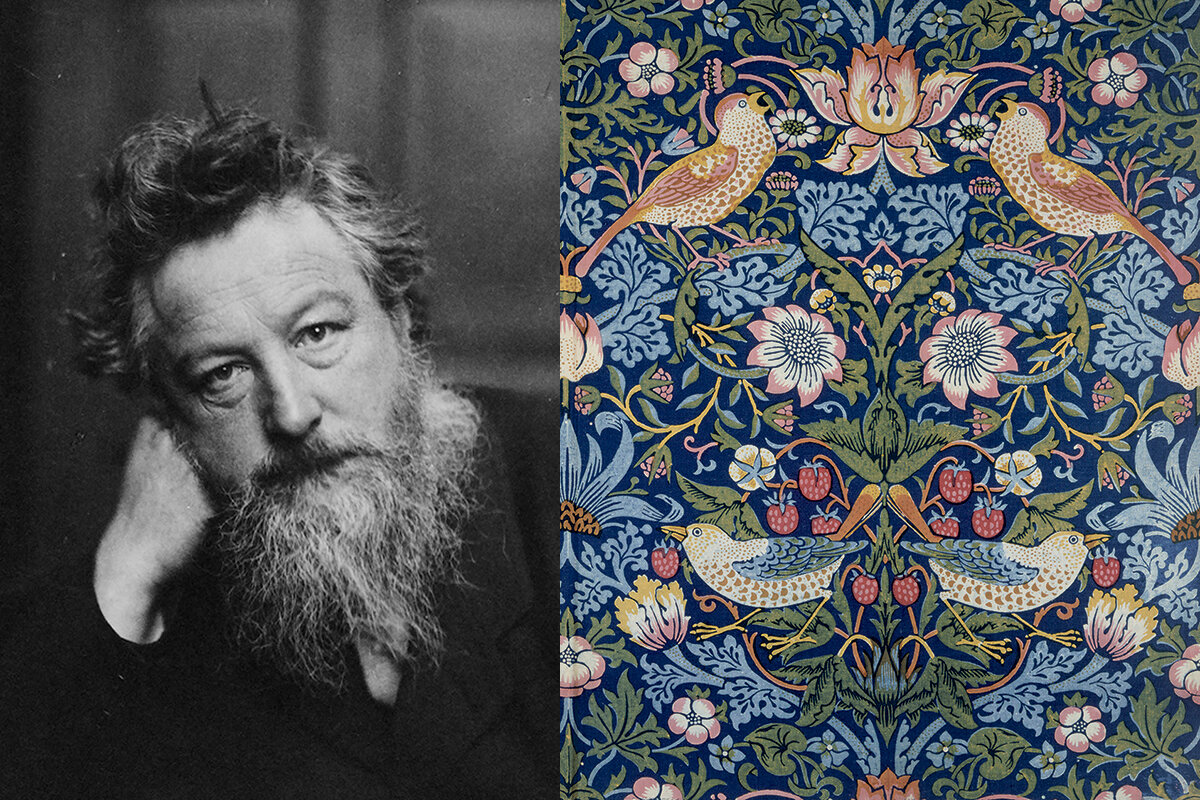

For designer William Morris, beauty was key to happiness

Luxury goods and social reform don’t often come from the same place. For textile artisan, tastemaker, and social reformer William Morris, his values were inseparable from his work.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

British designer William Morris is today best known for his lush, garden-inspired patterns for wall coverings, but his lifework encompassed far more than mere decoration. A gorgeously illustrated book, titled simply “William Morris,” edited by Anna Mason and released by the Victoria and Albert Museum, offers a detailed portrait of the man, his work, and the values that fueled both.

An outlier among his contemporaries, Morris was dismayed by the increased mechanization that he felt robbed workers of their dignity. He also believed that mass-produced goods were inherently inferior and that their shoddiness reflected poorly on the household for which they were purchased. His best-known dictum was “have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.”

He set out to address both worker alienation and consumer taste through a revival of the craft traditions that had flourished in medieval Europe from the time of the building of the great cathedrals. As one essayist in the book puts it: “For him, beauty was a ‘positive necessity,’ not a luxury but essential to human happiness.”

For designer William Morris, beauty was key to happiness

Behind the exquisite floral wallpaper lurks a social reformer. British designer William Morris (1834-96) is today best known for his lush, garden-inspired patterns for wall coverings, but his lifework encompassed far more than mere decoration. He sought nothing less than to overturn what he considered the deleterious effects of industrialization on Victorian society. And his artistic influence continues today, not only at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, an institution he helped shape, but also as inspiration to contemporary artists.

A gorgeously illustrated book, titled simply “William Morris,” edited by Anna Mason and released by the Victoria and Albert Museum, offers a detailed portrait of the man, his work, and the values that fueled both. Even the dust jacket is embellished with one of Morris’ elegant designs from the museum’s extensive archives of decorative art. The book, with essays by more than a dozen experts, lays out the varied aspects of Morris’ life as an artist, designer, poet, educator, entrepreneur, preservationist, and political activist. Each role fed the others, and nourished his restless and fertile mind.

Morris was considered an outlier by his contemporaries, who were busy either extolling Britain’s growing industrial might or profiting directly from it. Morris was dismayed by the increased mechanization that he felt robbed workers of their dignity and the potential for creativity in their work. He also believed that mass-produced goods were inherently inferior, that their manufacture led to waste and environmental degradation, and that their shoddiness reflected poorly on the household for which they were purchased. His best-known dictum was “have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.”

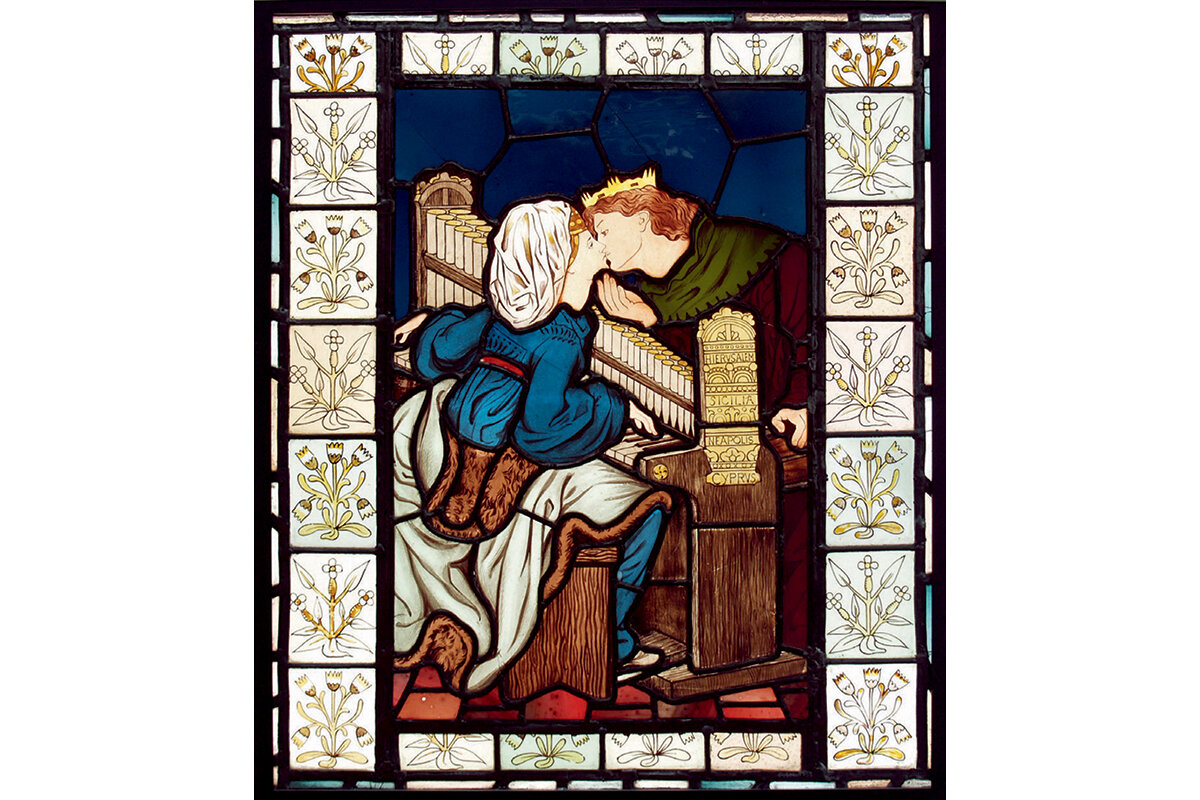

He set out to address both worker alienation and consumer taste through a revival of the craft traditions that had flourished in medieval Europe from the time of the building of the great cathedrals. These church edifices were complete works of art, and showcased the labor of hundreds of skilled workers, from stone carvers to stained-glass makers. Morris, who considered becoming an architect, visited cathedrals in France and Belgium as a young man, and was profoundly moved by the experience. He was inspired by how all the arts came together into a glorious whole, with each worker’s individuality still apparent and yet blended into the overall design. It filled him with hope.

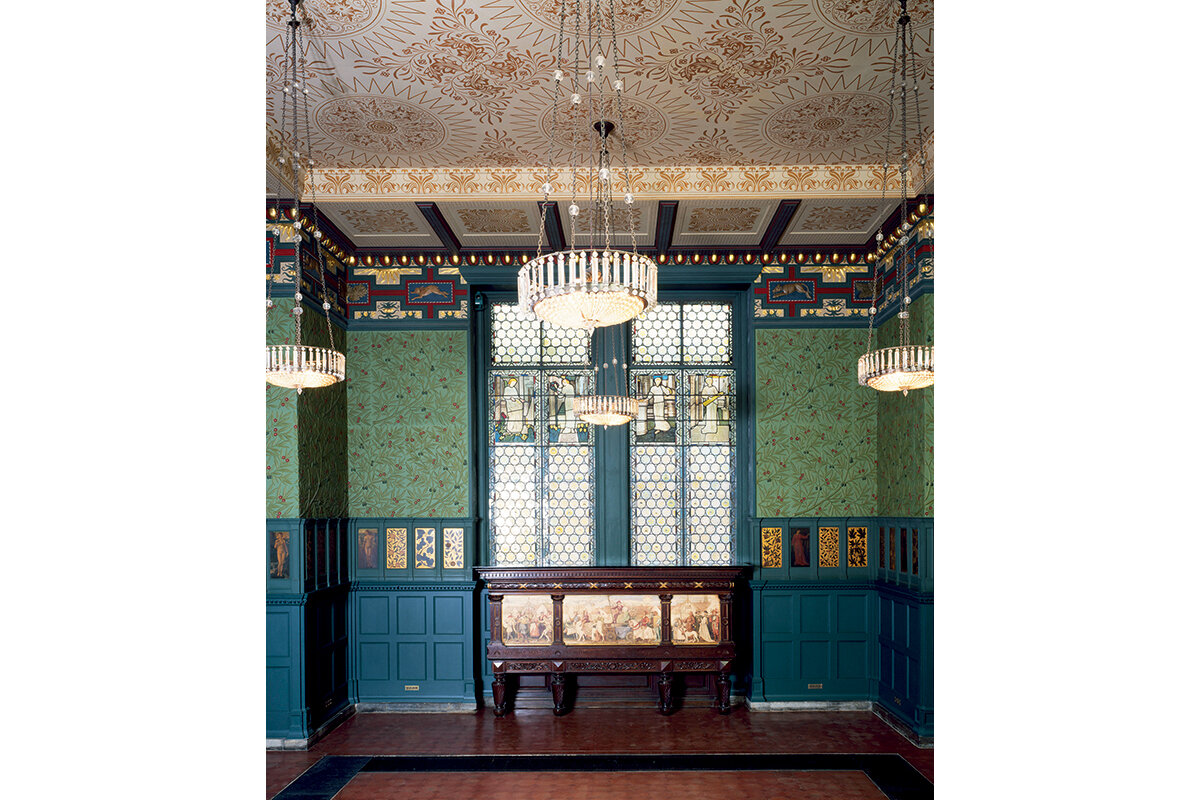

As part of replicating this medieval-artisan model in Victorian England, Morris decided to learn the skills involved. Over the years, he mastered painting and drawing, stained-glass making, textile making, weaving, and bookbinding. “He never designed anything he did not know how to produce with his own hands,” wrote an early biographer. In 1860, Morris and a group of influential artist friends formed a company that sold custom furnishings and a full range of decorating services.

The company’s painted cabinetry, stained glass, and wall hangings portrayed stories from Chaucer and King Arthur, along with characters from Greek mythology and the Bible. Morris and his cohorts chose strong, saturated colors, especially blues and reds, for their designs. The colors were inspired by those Morris had seen in the stained-glass windows of the cathedrals he visited. Before long, wealthy clients – from British nobles to American industrialists – began commissioning goods from the company.

With the success of his venture, Morris faced a conundrum. He was keenly aware that the furnishings were too expensive for ordinary people, and this did not sit well with his values. In the 1870s, he took a two-pronged approach: He became active in socialist causes on behalf of working-class people and also took control of the company, expanding it to include the training of workers and the selling of less expensive, but still high quality, merchandise. Morris oversaw all aspects from design to production, and from management to marketing. His London retail shop was likely one of the earliest interior design showrooms, with products arranged to demonstrate how pieces looked together. Morris & Co. became known for high-quality, well-made goods.

Morris’ political opinions did not seem to hurt his business. His designs conveyed a love of the natural world and a buoyancy that continued to appeal to clients – and still attracts admirers today. The patterns of flowers, vines, leaves, birds, and other animals suffuse his designs with joy. Many of Morris’ wallpaper and textile designs have never gone out of production, although now they are machine printed, rather than block printed by hand.

The name Arts and Crafts was given to the style of architecture and furnishings that Morris developed, and the movement spread to northern Europe and North America in the late 19th and early 20th century. It influenced architecture as well as interiors, although in greatly simplified form in the United States. Frank Lloyd Wright’s early prairie-style homes, with their stained glass and custom-designed furnishings, reflect an American variation on the style. In California, the architecture firm of Greene & Greene designed structures that became known as American Craftsman. In upstate New York, Gustav Stickley made furniture that became synonymous with Arts and Crafts.

The social and political component of Morris’ work, and especially his message of reform, did not make the jump to America, one of the book’s essayists explains, although Morris was a hero to at least two important social reformers, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, who founded Hull House in Chicago to offer community services, literacy classes, and arts and crafts workshops to newly arrived immigrants. The two women kept a portrait of Morris in a place of honor on the wall. Although he never traveled to the United States, his daughter, May, was able to visit Hull House.

Morris certainly inveighed against the social ills of his time, but he never lost his positive outlook. His critiques of injustice were “always balanced by an optimistic and inspiring vision of what a better future might look like,” according to another essayist. “For him, beauty was a ‘positive necessity’, not a luxury but essential to human happiness.”

April Austin is the Monitor’s books editor.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Given a chance, forests bounce back

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Could doing nothing help the environment?

Well, not really doing nothing. But in this case leaving land alone so that it can return to forest.

A study in the journal Science, published last week, showed the surprisingly quick return of land to a healthy forested state if simply left alone. Under the right conditions, forests reemerge from land that has been exploited by humans.

Tropical forests are disappearing around the world at an alarming rate. At the recent climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, world leaders promised to halt deforestation by the end of this decade.

Commitments to planting millions of trees have been made as part of the effort to absorb carbon from the atmosphere and provide greater biodiversity.

But these programs can be costly, and in some cases, a high percentage of the new seedlings die.

The study suggests that under the right conditions, tree planting could be greatly augmented by simply protecting land that has been cleared for agricultural or other human use and allowing it to return to forest. What surprises the researchers is how quickly such recovery can take place.

Sometimes just keeping hands off may be the best way to help.

Given a chance, forests bounce back

Could doing nothing help the environment?

Well, not really doing nothing. But in this case leaving land alone so that it can return to forest.

A study in the journal Science, published last week, showed the surprisingly quick return of land to a healthy forested state if simply left alone. Under the right conditions, forests can reemerge from land that has been exploited by humans.

Tropical forests are disappearing around the world at an alarming rate. At the recent climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, world leaders promised to halt deforestation by the end of this decade.

Commitments to planting millions of trees have been made as part of the effort to absorb carbon from the atmosphere and provide other beneficial environmental effects, including greater biodiversity.

But these efforts can be costly; in some cases, a high percentage of the new seedlings die.

This study suggests that under the right conditions, tree planting could be greatly augmented by simply protecting land that has been cleared of trees for agricultural or other human use and allowing it to return to a forested condition.

Forests are far more than collections of trees. They are complex networks of life that include a wide variety of plants, animals, and microbes.

Ideally, the abandoned land most suited to quick reforestation should have soil whose nutrients have not been totally exhausted, and should be located near other forested areas.

Allowing land to return to a forested condition on its own provides a “cheap, natural solution” to the urgent problems of diminishing biodiversity and climate change, says Lourens Poorter of Wageningen University in the Netherlands, who participated in the study. As trees grow, for example, they produce leaf litter, which in turn improves soil quality as it decomposes.

In the world’s tropics, forests are already rejuvenating themselves on about 3 million square miles of former farm or ranch land, the authors say. Protecting this process will be a critical part of regrowing forests.

The scientists’ research is also confirmed by the track record of forest regrowth that has been observed over long periods, they note, such as in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries and in the Northeastern U.S. in the early 20th century, where large tracts of land, once cleared for farming, have returned to healthy forest.

What surprises the researchers is how quickly such recovery can take place.

“My plea is to use natural regrowth where you can, and plant actively and restore actively where you need to,” Dr. Poorter says.

Sometimes just keeping hands off may be the best way to help.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Divine Love – our home base

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Lindsey Roder

When location and employment change or seem uncertain, recognizing God as our home base leads us forward with love and confidence.

Divine Love – our home base

For a military family, a home base is where the family lives and obtains needed supplies. It’s the central core of all operations, and it’s the starting and returning point for those who go out on operations. As I’ve considered a more spiritual concept of a home base, I’ve recognized God, divine Love, as my family’s home base.

In my husband’s naval career, we had a change of home base five times in eight years. With each move, I found myself alone in an unfamiliar place, without friends, family, home, church, or employment. It was tempting to think that I was lacking almost everything. To make things even harder, an unexpected terrorist attack on the United States changed my expectation of military service from adventure to uncertainty.

My husband’s schedule of deployment was top secret and often happened spontaneously, so I never knew exactly when he was coming or going. Weeks would pass without the ability to communicate with him. I found it vitally important to understand that my true home base – and his – is God, Love, the divine Principle of all action. This meant gaining a spiritual sense of where our good comes from.

In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy says of the Christian Science she discovered, “The effect of this Science is to stir the human mind to a change of base, on which it may yield to the harmony of the divine Mind” (p. 162).

This helped me realize that, despite the uncertainty, I was never alone, and that employment, supply, safety, communication, companionship, community, and Church are all spiritual ideas, unlimited and available to everyone at all times.

During one of our changes of home port from the Atlantic to the Pacific Coast of the US, I had a hard time finding employment. I spent weeks searching for jobs, but to no avail. I felt I had exhausted all of the resources that I could think of, and I still didn’t have a job. My husband was about to leave on his first deployment, and I felt uncertain about the future.

One day, I called my mom in tears, and she reminded me to “remember the dishwasher.” She was referring to a Christian Science audio program we’d both heard in which one of the speakers shared that he’d worked as a dishwasher, but disliked that job. However, if he couldn’t put the clean dishes away with a heart full of love, he would take them back down again and start over. As soon as he started doing each task with love, he started to see and feel the presence of God’s love all around him. This had a profound healing effect, and he even received several job offers. (See “God’s guidance in the workplace,” Sentinel Radio, May 31, 1998.)

The Bible says, “Let nothing be done through strife or vainglory; but in lowliness of mind let each esteem other better than themselves” (Philippians 2:3). I decided to follow this counsel. This mental “change of base” from a material to a spiritual perspective taught me that right employment is about humbly serving God and doing everything with a heart full of love – to the glory of God, not for any glory of my own.

As soon as I let unselfed love and service to God guide my job search, my fear and frustration subsided. Soon, I received a phone call from another Navy wife who had planned on quitting her job to go back to school, but felt bad about leaving her employer without an assistant. She asked me if I had any interest in being her replacement, and even though I didn’t have much experience in the field, I immediately accepted. The work was dynamic, flexible, and exciting, and I felt a fuller sense of God’s protecting power and guidance in my life.

The next Bible verse after the one quoted above continues, “Look not every man on his own things, but every man also on the things of others” (Philippians 2:4). This experience reflects that quote. My friend had been unselfish in not wanting to leave her employer to find a replacement and in thinking of me as a perfect candidate. Everyone had been blessed.

From this point on, I always found purposeful employment at each new duty station. This verse describes my experience beautifully:

Know, O child, thy full salvation;

Rise o’er sin and fear and care;

Joy to find, in every station,

Something still to do, or bear.

(Henry Francis Lyte, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 166, adapt. © CSBD)

When we’re facing uncertainty, where things seem as though they are constantly changing, or where fear seems to prevail, divine Love is guiding us to the home base of spiritual understanding, revealing the harmony of the divine Mind, and giving us a safe place to land.

A message of love

Time to trumpet

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. Looking for a good read for the holidays? Join us tomorrow when we’ll reveal our picks for the best new books of December.