- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A Monitor reporter’s own lessons from Jan. 6

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

In the United States, Jan. 6 has become a title as much as a date. It conjures up images of one of the most tumultuous days in American history. In today’s issue, Christa Case Bryant and Story Hinckley explore what that day means to different Americans.

But it means something personal to Christa, too. That was her first week as our new congressional correspondent, and rioters came within a flight of stairs of the press gallery where she initially sheltered. But the message she took from that day was not one of fear or anger. It was a deeper sense of purpose. “Some people might have thought it would make me regret my decision to take this job, but actually it underscored the vital importance of fair journalism at this moment in America,” says Christa.

The media has incredible power to shape national thoughts and narratives. It’s one reason Mary Baker Eddy founded the Monitor “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind.” Is that possible in a country that seems so divided?

Christa first started grappling with this question of fairness while posted in Jerusalem from 2012 to 2015. It begins with striving to avoid overly simplistic narratives and caricatures, she says. “I’ve found it’s a lot harder to do when you’re reporting on your own country.”

What has come into even sharper relief in the past year is the need for “an additional measure of self-knowledge, humility, and love,” she adds. Honing those qualities starts within the newsroom, though it holds larger lessons. Increasingly, Christa says, when an editor says something in a story draft feels out of balance, “I’m grateful for that. Together, we make the story stronger.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

A divided anniversary: Jan. 6 in the eyes of those who were there

In the year since Jan. 6, Americans have wrestled with what it means for the nation. The different views are key to understanding where America may be heading and how it can move forward.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

A year after the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol, those who were there that day are still grappling with what exactly happened, how, and why – and what it all says about the state of the republic.

The storming of the Capitol, to many, marked a low point of American democracy, an unthinkable act fomented by a presidential lie that came dangerously close to overriding the checks and balances that have safeguarded the United States for centuries.

For Trump supporters, however, the American citadel of democracy had been breached well before Jan. 6. They see the events of that day as a reaction to a yearslong effort by an elitist press corps and entrenched bureaucracy to undermine the legitimacy of Donald Trump’s presidency – an effort they see as continuing even now.

Understanding these views is key not only to putting together a fuller picture of that day, but also to discerning where America may be heading. In that sense, Jan. 6, 2022, is not just an anniversary but a flashing red marker on the path of a country that’s increasingly divided about how to move forward.

A divided anniversary: Jan. 6 in the eyes of those who were there

On the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, after pipe bombs were found on the outskirts of the U.S. Capitol complex, congressional staffer Anthony DeAngelo got word that a nearby office building had been evacuated and the building right next door was being evacuated, too. From a fourth-floor window, he could see police barricading the roads nearby.

He turned to his boss, Rep. Andy Kim of New Jersey. Did he want to make a run for it?

“No, I came here to vote today,” said Representative Kim, a Democrat who, along with the rest of Congress, was meeting that day to certify the states’ electoral votes.

Outside, Virginia state Rep. Dave LaRock was navigating through the throngs of Trump supporters who had come to hear the president speak at a Save America rally and then trekked up to the Capitol to register their deep distrust of the election results.

“I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard,” President Donald Trump had told the crowd, in a speech that also emphasized the importance of “fighting” for political victories and against a “corrupt” election. “We fight like hell – and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore,” he said.

As Mr. LaRock walked around the Capitol, he began hearing that something had gone “very, very wrong.” People had broken into the Capitol. Someone had been shot. He saw smoke wafting through the air – probably tear gas, he surmised, but he didn’t stick around long enough to find out.

Inside the House chamber, Rep. Bennie Thompson’s phone rang. It was his wife. “What’s going on?” she asked. “What do you mean?” asked the Mississippi Democrat, who had entered the Capitol through underground tunnels and hadn’t seen the huge crowds amassing outside.

“They have broken into the Capitol!” she told him.

As hundreds of protesters poured into the building through shattered windows and doors, rioters – some in military-style goggles and vests – assaulted Capitol Police, beating them with flagpoles and their own riot shields. Others stood on the steps of the Capitol chanting “hang Mike Pence,” who as vice president had been overseeing the vote certification before being whisked off the Senate floor.

On the House side, lawmakers donned escape respirators stored under the seats, removed the lapel pins identifying them as members of Congress, and prepared to evacuate. As protesters smashed the glass of one of the chamber doors, they came face to face with guns drawn by two protective officers. In a side corridor outside the chamber, Capitol Police officer Michael Byrd fatally shot unarmed Air Force veteran Ashli Babbitt as she tried to climb through a smashed glass door panel.

Sgt. Aquilino Gonell, a veteran and a Capitol Police officer, would testify months later that he was more afraid that day than he was patrolling IED-infested roads in Iraq. Rioters called him a traitor and shouted that he should be executed.

“All of them were telling us, ‘Trump sent us,’” said Sergeant Gonnell.

An hour after the initial breach, GOP Rep. Mike Gallagher took to Twitter with a video shot in his office. “Mr. President, you have got to stop this,” said Representative Gallagher, a former Marine officer who twice deployed to Iraq. “This is bigger than you; it’s bigger than any member of Congress. ... It’s about the United States of America.”

Democratic Rep. Ilhan Omar took it a step further.

“I am drawing up Articles of Impeachment,” she tweeted. “It’s a matter of preserving our Republic.”

One year on, former President Trump is living in Florida, hundreds of rioters are facing prosecution, and a congressional committee is uncovering critical information about the events of that day. But many who were at the Capitol on Jan. 6 are still grappling with what exactly happened, how, and why – and what it all says about the state of the republic.

The storming of the Capitol, to many, marked a low point of American democracy, an unthinkable act fomented by a presidential lie of a “rigged” election that came dangerously close to overriding the checks and balances that have safeguarded the United States for centuries.

In the eyes of many Trump supporters, however, the citadel of democracy had been breached before Jan. 6. They see the events of that day as an inevitable reaction to a yearslong effort by an elitist press corps and entrenched bureaucracy to undermine the legitimacy of Mr. Trump’s presidency – an effort they see as continuing even now.

Understanding these views is key not only to putting together a fuller picture of that day, but also to discerning where America may be heading. In that sense, Jan. 6, 2022, is not just an anniversary but a flashing red marker on the path of a country that’s increasingly divided about how to move forward.

Ms. Omar got her articles of impeachment, but she’s impatient for the instigators to be held accountable. Sergeant Gonell, one of more than 145 Capitol Police officers injured that day, is still recovering.

Republicans who spoke out against Mr. Trump have mostly kept quiet since – or, if not, faced his wrath. Representative Gallagher voted to certify President Joe Biden’s win, but did not support Mr. Trump’s impeachment and voted against a bipartisan bill to establish a national commission to investigate Jan. 6.

Mr. Thompson is chairing a Jan. 6 select committee made up of Democrats and two GOP critics of Mr. Trump, which has so far interviewed 300 people and collected 30,000 records. Mr. LaRock won reelection to the Virginia statehouse by his largest margin yet.

And Mr. DeAngelo – whose boss was seen quietly sweeping up debris in the riot’s aftermath, an image that immediately went viral – quit his job and went to work with the National Democratic Institute. He now runs a program that pairs members of Congress with lawmakers in emerging democracies.

“When you see aspiring democracies around the world face challenges with disinformation and rising extremism within their own populations, you see that this truly isn’t just an American struggle right now,” says Mr. DeAngelo. “It’s something that a lot of governments, a lot of democratic institutions are facing – that loss of faith in those institutions, attacks on the basic functionalities of those institutions, and a drop in trust and faith in institutions that carried those democratic ideals.”

“Those old demons of bigotry”

Raphael Warnock was not in the Capitol on Jan. 6. It was only in the wee hours of the morning that he learned that he, a kid from public housing in Georgia, had become the first Black U.S. senator elected from the former Confederate state. Later that day, protesters launched a violent assault and strode through the halls of Congress carrying the Confederate flag in what he saw as an effort to disenfranchise voters of color, who disproportionately voted for Mr. Biden.

“Jan. 5 represents what’s possible in this country,” says Senator Warnock, a senior pastor at the Atlanta church where Martin Luther King Jr. preached. “Jan. 6 [brought out] folks driven by the mythologies of hate and division. In a real sense, that’s where we live – between the ideals, our highest ideals, and those old demons of bigotry.”

Indeed, many on the left see that day as a rebellion of mainly white men, fueled by resentment of their own declining status amid the country’s rapidly changing demographics. One University of Chicago study last spring found that of the people arrested so far in connection with the riot, 95% were white, 85% were male, and they hailed disproportionately from counties with the greatest decline in white population.

Those who showed up at the Capitol were also driven by a conviction that democracy had already been subverted. And with Mr. Trump still refusing to accept electoral defeat, Democrats say the GOP has abetted and exploited that false claim of a stolen election, passing a raft of laws that will restrict voting access for people of color and lower socioeconomic status.

“The big lie that motivated that attack is being repeated in state legislatures around the country,” says Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine, who was on the 2016 Democratic ticket as Hillary Rodham Clinton’s VP pick when Mr. Trump won. “The best response to that is to put up a vigorous protection of people’s rights to vote and to disable schemes and power grabs that undermine election integrity.”

Senate Democrats have tried to pass sweeping voting rights legislation several times over the past year, but they have been blocked by Republicans under current filibuster rules.

Representative Gallagher, the Wisconsin Republican who urged Mr. Trump to call off the rioters on Jan. 6, says if the federal government gets more involved in managing elections, the nation may become more susceptible to a power grab.

“There’s a good reason why elections are run by not just states but really localities – it creates a natural defense in depth against anyone who would try to meddle in our elections or commit fraud,” says Mr. Gallagher.

He argues that one reason America’s elections have become so existential, and the battles over election reform so toxic, is because the federal government has already become too powerful.

“Every four years we await the coming of some messianic presidential figure to do everything through executive fiat,” he says. “And that, in turn, exacerbates the dysfunction in [Congress]. And members then get disillusioned, because they’re sitting here in a feckless institution.”

An insurrection? Or something else?

There is still disagreement about what, exactly, Jan. 6 was. A coup? An insurrection? An angry mob that surprised not only the world but also many of its own participants by breaking into America’s premier symbol of democracy?

So far, of the more than 725 individuals arrested, none have been charged with insurrection, though more indictments may be coming.

One thing that’s clear is that the sentiments that precipitated the violence have not dissipated – if anything, they seem deeper and more widespread. According to a Yahoo News survey from last month, 74% of Republicans agree with the statement, “The election was rigged and stolen from Trump.” Moreover, 64% said they disapprove of the congressional committee investigating Jan. 6, and 54% said they thought the courts were treating those who attacked the Capitol “unfairly.”

In the weeks following the 2020 election, the Trump campaign challenged the results in dozens of court cases but failed to prove anything approaching the widespread fraud the president alleged. Then-Attorney General William Barr, appointed by Mr. Trump, said in December 2020 that the Department of Justice had not uncovered such evidence either. An Associated Press review published last month, which contacted hundreds of election offices in five battleground states, turned up only 475 instances of fraud – equivalent to 0.5% of Mr. Biden’s margin of victory.

Still, many Trump supporters remain unconvinced that Mr. Biden could have legitimately beaten their preferred candidate, when Mr. Trump got 11.2 million more votes than in 2016 – more than any presidential candidate in history, except his opponent. They argue that the rapid expansion of mail-in voting, which contributed to nearly 20 million more people voting than ever before in a presidential election, violated some states’ laws and that other pandemic-related changes loosened or eliminated procedures meant to ensure election integrity.

Mr. LaRock says it was distrust of the election results that brought him to the Capitol on Jan. 6. He points to a case brought by the Texas attorney general questioning the constitutionality of changes to voting practices in four key swing states. The suit argued, for example, that Pennsylvania usurped its own legislature’s authority when it eliminated a signature requirement for absentee ballots, while Wisconsin contravened its own state law by allowing drop boxes. The Supreme Court declined to examine the merits of the case, ruling that Texas didn’t have the legal standing to bring it.

Democrats, journalists, and election officials from both parties have pointed out the multitude of systems in place to guard against voter fraud. But many Trump supporters have little faith in those assurances, after what they see as years of biased media coverage and partisan efforts to undermine the former president.

GOP Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin says frustration over the “Russia hoax” and unfair media treatment “tormenting Trump and his supporters” for four years helped precipitate Jan. 6. The infamous dossier that helped spur the Russian collusion investigation into the Trump campaign, for example, turned out to be not only largely false but also funded by the Clinton campaign.

“It just kind of finally erupted,” says Senator Johnson, who has also faulted journalists for not acknowledging that the majority of protesters never entered the Capitol building and most committed no crimes. “How Jan. 6 has been covered by the mainstream media just completely reveals their grotesque bias. And truthfully, I would argue, their complicity in exacerbating the divide in this country.”

“The worst I’ve ever seen”

Democrats have sharply criticized Senator Johnson and other Republicans for trying to “whitewash” the Capitol attack in the weeks and months that followed, making it sound more like a peaceful gathering than an assault on democracy.

Some Trump supporters have even suggested that the unlawful behavior was perpetrated by leftist instigators, though FBI Director Christopher Wray testified to Congress that there was no evidence of that.

“When you see people wearing brand-new Trump hats, not talking to anybody, it really stands out,” explains Suzzanne Monk, a District of Columbia resident and Trump supporter who was at that Capitol that day. She claims that another Trump rally she attended, in Chicago, was turned into a “riot” by antifa, a movement of far-left-leaning militant groups. “This is not the first time that we in the Trump movement are infiltrated by people who are not on our side and trying to cause conflict.”

This effort to recast the day’s events as more benign has been especially difficult for police officers like Sergeant Gonell and Officer Harry Dunn, who was called a racial slur by a woman in a pink MAGA shirt who had broken into the Capitol.

“Jan. 6 was bad enough. The worst I’ve ever seen,” Officer Dunn told the Monitor, as he and Sergeant Gonell wound their way through one of the Capitol complex’s basement hallways after attending a Jan. 6 committee hearing in street clothes last month. “But the response is equally disheartening.”

Although many Republican lawmakers called on the rioters to stop the violence that afternoon and criticized Mr. Trump for egging them on, most have since softened their tone or gone silent.

“From Jan. 6 to now, they’re walking it back to saying, ‘Oh, they were just blowing off steam,’ or ‘Oh, it was just the equivalent of a Capitol tour,’” says Officer Dunn. “That’s not the case. What the world saw with their own eyes actually occurred.”

Four people died in the chaos of that day, though two of those deaths were officially ruled to be from natural causes and one from an overdose. Five police officers died in the days and weeks that followed, four of them by suicide.

Chairman Thompson, Mississippi’s longest-serving Black elected official, says he wasn’t afraid for his own safety that day, but was concerned that one of the bedrocks of the American system – the peaceful transfer of power – was being threatened. This was not the America he had been raised to believe in, or the America he took an oath as a member of Congress to defend.

“A lot of the people who took that same oath to defend the Constitution are now defending the people who broke into this institution, which is bizarre,” he says.

Republican Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas, who on Jan. 6 contested the election results in Arizona and Pennsylvania, has called what happened that day “a violent terrorist attack on the Capitol.” But he accuses Democrats of a double standard – harshly condemning the Jan. 6 riot while ignoring the “violent terrorist attacks from left-wing activists” that occurred at some Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020. A report from one police group found that 7% of those protests involved violence, with more than 2,000 officers sustaining injuries. The first two weeks alone resulted in an estimated $1 billion to $2 billion in property damage – the costliest civil disorder tab in America’s history.

Democrats counter that there’s no moral equivalence between the motivations of the social justice protests and Jan. 6.

“In Minneapolis, folks were protesting a police officer putting his knee on a Black man’s neck and literally killing him,” says Democratic Rep. Angie Craig of Minnesota. “Here, people were literally trying to overturn the results of a United States election.”

The People’s House

Marie March, a small-business owner from Christiansburg, Virginia, went to Mr. Trump’s Stop the Steal rally on Jan. 6 – her birthday – with her husband and father. None of them had ever attended a Trump rally in person before. “My husband was like, ‘Well, Marie’s birthday is Jan. 6, and we live three to four hours away from D.C.,’ so we hopped in a car a few days after Christmas,” she recalls.

They left early, she says, because it was freezing. They didn’t even know people had headed to the Capitol until they stopped at a Cracker Barrel on the way home and friends started texting, “The Capitol is getting overrun, are you there?”

In the aftermath, however, people back home started calling her an “insurrectionist.” She says it affected business at one of her family’s restaurants, Due South BBQ. Then, left-wing activists showed up at their other restaurant, Fatback Soul Shack, and cut down the American flag. The reaction prompted Ms. March to run for the statehouse this fall. She won by a margin of nearly 2 to 1.

But many Trump supporters may be too disillusioned to work within a system they see as corrupt. According to a November survey by the Public Religion Research Institute, nearly 1 in 5 Americans (18%) agreed with the statement, “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” Among those who believed the 2020 election was stolen, support for political violence doubled to 39%.

Much more than a lone wolf threat, a significant swath of Americans now appears to have lost trust in its country’s fundamental institutions – and may be prepared to act on that disillusionment. The deep divisions exposed and exacerbated by Jan. 6 will clearly require more than time or a single committee’s work to heal.

One modest way Congress can take a step toward rebuilding trust, some say, is by reopening to the public. Allowing citizens to see the inner workings of government for themselves – visiting lawmakers’ offices, or watching proceedings in the House and Senate chambers – can help them realize that they can participate in that system. But so far, the Capitol complex remains closed.

Before the pandemic, staffers used to bemoan the tourists forming long lines in the cafeteria, says Mr. DeAngelo, the former deputy chief of staff for Representative Kim. “But I always loved it because it meant that people were flying in from around the world, to come to where we work, to understand what we do, to see democracy in action,” he says.

Opening the Capitol’s doors to the public once more would be a good symbolic gesture toward restoring what was figuratively shattered on Jan. 6, he adds, just as his boss picking up the pieces of broken glass and trash on the night of Jan. 6 gave hope to those shaken by the physical breach.

“I really hope that people get a chance to come and see that this wasn’t just a building where an attack took place, but it’s a building where progress can be made, where we can still do big and good things,” says Mr. DeAngelo. “And I hope that’s part of the healing process. Not just for people at the Capitol, but for the country as well.”

Graphic

By the numbers: The cost and consequences of the Jan. 6 riot

Amid the political rhetoric over the Jan. 6 riot, it can be easy to lose sight of what actually happened that day. Here are some of the hard facts around the attack and its fallout.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 1 Min. )

-

Nick Roll Correspondent

-

Jacob Turcotte Staff

When a mob stormed the United States Capitol last Jan. 6 – hoping to stop a lost election they claimed was stolen – they were only inside for a few hours. Security forces cleared the building by the early evening. After hours of debate in both houses of Congress, Joe Biden officially became president-elect the next morning.

The short insurrection failed, but it cast a long shadow. Nine people died during the attack or in its aftermath, including four Capitol Police officers who were present at the riot and died by suicide in the following months. Nearly $1.5 million was spent on repairs to the Capitol building.

In the past year, more than 725 defendants have been arrested for crimes connected to the Capitol riot, and approximately 165 have pleaded guilty. The longest sentence handed down so far has been 63 months in prison for “assaulting law enforcement with dangerous weapons.”

The congressional investigation into instigation of the Capitol riot is ongoing. Though a bipartisan effort to impeach President Donald Trump ultimately resulted in a Senate acquittal last February, a House select committee of seven Democrats and two Republicans is still calling witnesses on the riot.

By the numbers: The cost and consequences of the Jan. 6 riot

When a mob stormed the United States Capitol last Jan. 6 – hoping to stop a lost election they claimed was stolen – they were only inside for a few hours. Security forces cleared the building by the early evening.

After hours of debate in both houses of Congress, Joe Biden officially became president-elect the next morning.

The short insurrection failed, but it cast a long shadow. In the year since, the country’s politics have become more aggrieved. Voting rights have been restricted in some states and politicians have adjusted to death threats – which likely reached an all-time high in Congress in 2021.

The insurrection was short. But as a House select committee investigates that day from Washington, the malaise in American politics speaks to its influence. A year later, Jan. 6 is still with us.

The graphic below charts the quest to unravel details of that day.

George Washington University Program on Extremism, NPR, U.S. Justice Department, U.S. Congress, Pew Research Center, The New York Times, The Washington Post, CBS News, The Guardian, Ballotpedia, The Atlantic, Senate Committee on Appropriations Chairman Office

George Washington University Program on Extremism, NPR, U.S. Justice Department, U.S. Congress, Pew Research Center, The New York Times, The Washington Post, CBS News, The Guardian, Ballotpedia, The Atlantic, Senate Committee on Appropriations Chairman Office

Why Jan. 6 isn’t over

The Jan. 6 riot has rightfully gotten a lot of attention – but in some ways, what was happening behind the scenes, both before and after, may be more significant.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Jan. 6 isn’t just an event for the history books. It’s not even past. It’s still occurring.

In the months since pro-Trump protesters smashed their way into the halls of Congress with the apparent intent of attacking and disrupting the counting of Electoral College votes, it has become increasingly clear that the violence was just one part of a broader effort to overturn the 2020 presidential election. In the months since, that effort has focused on the nation’s electoral system, making changes that might favor former President Donald Trump and pro-Trump candidates in elections to come.

In that sense, Jan. 6 was a highly visible symbol of – and important piece of – systemic action to undermine the nature of American democracy. Since then, former Trump officials have revealed the surprising extent of planning to stop certification of President Joe Biden’s victory – including one alleged effort nicknamed the “Green Bay Sweep.”

Mr. Trump has continued to push Republican candidates at all levels to embrace his false claims of election fraud and pass new laws restricting voting. Violent threats have poured into the offices of state election officials, leading many to quit.

The good news is that American democracy stood up and passed its test in late 2020 and early 2021.

The question is, can it withstand further challenge?

Why Jan. 6 isn’t over

The mob is gone. The pepper spray has dissipated. The pounding on the door into the House of Representatives – a battering ram sound that still haunts some members – has stilled.

It has been a year since the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and in some ways American politics and government has returned to normal. Lawmakers are wrangling over bills and budgets. Party strategists are focused on redistricting and upcoming midterm elections.

But Jan. 6 isn’t just an event for the history books. It’s not even past. It’s still occurring.

In the months since pro-Trump protesters smashed their way into the halls of Congress with the apparent intent of attacking and disrupting the counting of Electoral College votes, it has become increasingly clear that the violence was just one part of a broader effort to overturn the 2020 presidential election. In the months since, that effort has focused on the nation’s electoral system, making changes that might favor former President Donald Trump and pro-Trump candidates in elections to come.

In that sense, Jan. 6 was a highly visible symbol of – and important piece of – systemic action to undermine the nature of American democracy. Since then, former Trump officials have revealed the surprising extent of planning to stop certification of President Joe Biden’s victory – including one alleged effort nicknamed the “Green Bay Sweep.”

Former President Trump has continued to push Republican candidates at all levels to embrace his false claims of election fraud and pass new laws restricting voting. Violent threats have poured into the offices of state election officials, leading many to quit.

The good news is that American democracy stood up and passed its test in late 2020 and early 2021. Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and other key GOP officials resisted Mr. Trump’s pressure to “find” votes to reverse the presidential outcome in key states.

The question is, can it withstand further challenge?

“People say, ‘Look, it held, the institution held,’” says Laura Thornton, director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy at the German Marshall Fund. “That’s true to an extent, but it’s not quite as strong as that indicates. It held because a few election officials had a moral compass. It should be a little stronger than that.”

“Green Bay Sweep” and other tactics

At the time, the Jan. 6 insurrection seemed a shocking, virtually unprecedented event. Five people died during or in the hours after the violence that day, and more than 145 police officers were injured. Crowds bludgeoned members of law enforcement with metal barriers, flagstaffs, fire extinguishers, and their own riot shields. Intruders broke into the Senate chamber and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office. A Confederate flag fluttered in the Rotunda.

The Department of Justice has moved deliberately since that day to identify and prosecute those who broke the law by intrusion or violent action. So far 725 people have been charged for their roles on Jan. 6, Attorney General Merrick Garland said Wednesday. Of those, 325 have been charged with felonies.

“Actions taken thus far will not be our last,” said Attorney General Garland.

No evidence has yet emerged that Trump White House officials or other political figures communicated with or controlled members of the mob as they assaulted the building. But over the past year plenty of evidence has emerged that ties Trump figures to plans to slow or block the counting of electoral votes scheduled for that day, on the pretext the votes were fraudulent and the “steal” needed to be stopped.

Conservative lawyer John Eastman, then working with President Trump’s legal team, drew up a memo that hinged on Vice President Mike Pence halting the count or throwing out the results. More recently, Bernard Kerik, former New York City police commissioner and another legal adviser to Mr. Trump, informed the House January 6 committee of the existence of a document titled “Draft Letter from POTUS to Seize Evidence in the Interest of National Security for the 2020 Elections.” (Mr. Kerik said he is withholding that letter on grounds of executive privilege.)

In his recent memoir, Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro wrote of the “Green Bay Sweep” plan, which involved not former Packer great Paul Hornung but an attempt by friendly members of Congress to delay an electoral count vote by 24 hours, allowing key state legislatures time to send new slates of electors to Washington.

The House January 6 committee has released numerous text messages to and from White House officials outlining different versions of this basic attempted Biden-blocking scheme. Former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, for instance, said “Yes. Have a team on it,” in a text to one unidentified GOP lawmaker.

On Jan. 6 itself, texts from Donald Trump Jr., Fox News personalities, and others poured into the White House imploring a silent President Trump to call off the rioters. Wrap all this together and the riot seems just one part of a larger ongoing effort.

“What we’re learning is the depths of that intention on the part of the White House,” says Robert Lieberman, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University.

America sharply divided over Jan. 6 meaning

Meanwhile, over the past year the U.S. has split along political lines over Jan. 6 memories. One side sees it as a stain on national history. The other, driven largely by false assertions of voter fraud and the efforts of some Republicans to downplay aspects of the day, see it as something else.

Ninety-three percent of Democrats, and about 60% of the nation as a whole, say they consider Jan. 6 an attack on the government, according to a Quinnipiac poll from last October. Only 29% of Republicans agree.

Ninety percent of Democrats, and about 66% of the nation as a whole, remember the day as being extremely or very violent, according to a recent Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research survey. Only 40% of Republicans say they remember the events of Jan. 6 as violent.

Behind this are conservative conspiracy theories spun by Fox News hosts and others who have asserted that the attack on the Capitol was a false-flag operation instigated by Antifa, or FBI informants, or some other sort of deep state government agents.

Last year Republican Rep. Andrew Clyde of Georgia compared the violent insurrection to a “normal tourist visit” by vacationers. Not every GOP official believes this. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell described the day as “horrendous” in an interview late last year. Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland said on Jan. 2 that comparing the struggle for the Capitol to tourism is “insane.”

The context for this is Mr. Trump’s grip on the Republican Party. Denial that he lost in 2020 has become a litmus test for winning his endorsement. He has pushed for revenge GOP candidates to compete in primaries against party figures who deny his false allegations of election fraud, such as Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, who voted to impeach President Trump and lost her leadership position in the GOP. Trump followers are pursuing election posts in many states. At least 15 Republicans running for secretary of state – a key election post – in states across the U.S. question the legitimacy of President Biden’s win, despite no evidence of widespread fraud.

“It’s one thing to see these types of attitudes, these anti-democratic attitudes, among the mass public. It’s another thing to see it taking such a hold among the elected elites, and I think that’s what is most troubling and worrying,” says Cornell Clayton, professor of government at Washington State University.

“Democracy was attacked”

President Biden spoke from the Capitol on Thursday trying to put the events of Jan. 6 in a larger context.

“For the first time in our history, a president not just lost an election, he tried to prevent the peaceful transfer of power as a violent mob breached the Capitol,” Mr. Biden said. “But they failed.

“Democracy was attacked,” he added. “We the people endure. We the people prevailed.”

Mr. Trump issued a statement in response attacking Mr. Biden on a range of issues from the border to the economy, and saying that Democrats were using Jan. 6 to divide the country.

That’s the divide the U.S. now faces.

Yet that’s also the new reality of American politics. The power of disinformation disseminated by partisan outlets and social media is such that it can deny evidence in front of our eyes, says Ms. Thornton of the Alliance for Securing Democracy.

“I think January 6th was a democracy-rocking event. To have people try to rewrite that script is shocking enough, but it’s also perplexing, because we can see the video evidence that it wasn’t peaceful,” she says.

That’s why it isn’t enough that democracy survived a troubled transfer of power in 2021, she adds. One political party is full of seething voters who think the presidency has already been stolen. Unless that can be defused, in a nation full of guns, Jan. 6 might just be a harbinger.

More civic education and more election transparency via trained observers are among the things that might help.

“What are the solutions? How do we fix it?” Ms. Thornton asks, adding that getting ahead of this problem should be a national focus in years ahead.

Staff writer Dwight Weingarten contributed to this report from Washington.

Patterns

Putin revives Soviet-sized ambitions in Europe

Vladimir Putin cannot restore the Soviet Union, but his recent moves show his goal: to reestablish Moscow’s sphere of influence in Europe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Thirty years ago, the Soviet Union collapsed at Christmastime. Vladimir Putin has called that moment in 1991 the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century.

And now, after three decades of what he feels has been humiliation by the West, Russian President Putin is trying to reverse some of the consequences of the dissolution of the USSR.

At home, he has been rehabilitating the image of Josef Stalin for the dictator’s decisive role in winning World War II. Abroad, he is challenging the European security arrangements that have grown up since 1991, seeking to roll back NATO’s growth and to reestablish a formal “sphere of influence” for Moscow. That is what seems to be behind the deployment of an estimated 100,000 Russian troops at the Ukrainian border, threatening a possible invasion.

Western diplomats have dismissed Mr. Putin’s initial list of negotiating demands as a non-starter. But the Russian leader has succeeded in grabbing Western attention, and in provoking a sense of urgency about dealing with the Kremlin unseen since the Cold War. The question now is how much more it will take to convince him to call off his military escalation.

Putin revives Soviet-sized ambitions in Europe

It’s the Ghost of Christmas Past: the echo of another yuletide, exactly thirty years ago, which saw the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

Yet as the new year begins, that memory is exerting an ever-stronger influence on the behavior of the president of post-Soviet Russia, Vladimir Putin.

Mr. Putin wishes the Soviet Union had never ended. He has said so openly, describing that Christmas in 1991 as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century.

He cannot realistically hope to turn back the clock. But both at home and beyond Russia’s borders, especially in the escalating standoff with the West over Ukraine, he is clearly trying to undo some of the key changes brought about by the collapse of the USSR.

More broadly, he wants to expunge what he has felt to be the past three decades of national humiliation, by asserting Russia’s renewed status as a major world power.

Can he do it?

At home – at least in the short term – there seems little prospect of effective pushback. There, alongside a Soviet-style clampdown on human-rights advocates, Mr. Putin has also been rehabilitating the World War II role of Josef Stalin as part of an overarching national narrative of Russian greatness.

Those two strands were intertwined in a court case against Memorial International, an organization set up with the support of the dissident Nobel Prize-winning physicist Andrei Sakharov in the waning years of the USSR to chronicle the stories of the millions of Soviet citizens Stalin sent to their deaths. A sister group monitors contemporary human-rights violations.

Last week, Russia’s Supreme Court revoked Memorial’s legal status. And in the run-up to the ruling, a state prosecutor explained why the authorities were muzzling the organization. “Why do we, the descendants of [World War II] victors have to repent and be embarrassed,” he asked, “instead of being proud of our glorious past?”

Abroad, however, Mr. Putin’s rehabilitation project is facing sterner opposition, as Western nations rally to deter an estimated 100,000 Russian troops now massed on their border with Ukraine from any plan to invade.

In the eyes of Ukraine’s government, and its allies in Europe and the U.S., the troop buildup is the most recent of Mr. Putin’s threats to the stability, independence, and territorial integrity of a neighboring state, following his 2014 intervention in the largely Russian-speaking eastern region of Ukraine and his forcible annexation of Crimea.

For Mr. Putin, though, something wider is at stake: the Ghost of Christmas Past.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, an array of former Soviet republics, along with former Warsaw Pact satellite allies in Eastern Europe, turned their backs on Moscow to forge close ties with the West. A number joined the NATO military alliance, among them Poland, on Ukraine’s western border, along with Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, the Baltic states, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia.

As far back as 2007, Mr. Putin was publicly insisting that NATO’s eastward “enlargement” had to stop. It has largely done so: Only the relatively small states of Albania, Croatia, and the former Yugoslav territories of Montenegro and North Macedonia have been welcomed in since then.

But two other countries, both former Soviet republics, have made no secret of their desire to enter NATO: Georgia, where Russian troops helped separatist regions Abkhazia and South Ossetia break away in 2008, and Ukraine.

Ukraine matters most. Historically entwined with Russia, it was – economically, politically, and militarily – a core component of the Soviet Union. Its border with Russia stretches nearly 1,500 miles.

For security reasons alone, Mr. Putin sees good reason to insist that Ukraine must not join NATO.

But his aim is broader: to restore to Russia – shrunken in both territory and power since Christmas 1991 – a measure of its former geopolitical clout in its dealings with the West.

In demands sent to Washington and NATO last month, Moscow insisted not only on a guarantee that neither Ukraine nor other former Soviet states would join NATO. It also demanded the alliance remove its military presence in East European member countries such as Poland, Romania, and the Baltic states, and forgo any deployment outside Western Europe that Russia deemed a threat to its security.

Western diplomats dismissed the menu of demands as a non-starter. If met, they would land the former Warsaw Pact countries back within a formally reestablished Russian “sphere of influence.” Neither they, nor NATO, are going to accept that, as President Putin almost certainly knows.

But with a trio of diplomatic meetings on the Ukraine crisis starting next week, he has already succeeded in grabbing Western attention, and in provoking a sense of urgency about dealing with the Kremlin not seen since the Cold War.

The question now? How much more it will take to convince President Putin to call off his military escalation.

Q&A

How one American Jew learned to see Israel in new light

In the view of many outsiders, Israel is synonymous with conflict. But author Ethan Michaeli found another side of Israeli society as well, a deeply rooted interdependence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Weary of the tired narratives about Israel that tend to percolate in the United States, author Ethan Michaeli introduces readers to the complexities – and humanity – of life there in his new book, “Twelve Tribes: Promise and Peril in the New Israel.” A deeper understanding won’t fix everything, he says, but it may help uplift the debate.

What most Americans know of Israel centers around cultural conflict. But it’s important to remember that “Israel for thousands of years was a place where everybody lived together – Jews, Muslims, Arabs, Europeans, and many others,” he says. “So it has to be a shared space, both physically and intellectually.”

His research into this book helped him to see coexistence as not just a possibility for the future, but as a current reality. “Palestinians, Haredim, and secular Jews are all integral parts of Israel,” he says. “They very much already work and live together and depend on each other, even when they don’t know it.”

He is careful not to minimize the extent of bitterness and conflict, but “with all the vitriol and with all the hyperbole,” he says, “there is a very strong impulse for people to live together.”

How one American Jew learned to see Israel in new light

Israel is often seen as a place of intractable divisions. But author Ethan Michaeli, the son of Israelis who moved to the United States, grew weary of hearing the same old narratives. So he set out on a journey to paint a more nuanced portrait. In “Twelve Tribes: Promise and Peril in the New Israel,” he brings readers along for the ride, introducing them to the complexities – and humanity – of life in modern Israel. A deeper understanding won’t fix everything, he says, but it may help uplift the debate. He spoke recently with the Monitor.

Why did you decide to write this book?

Whenever I see conversation among Americans about Israel, there’s no lack of care, there’s no lack of concern, there’s no lack of interest. But there’s a lack of currency. People are often arguing about things that in Israel are either not problems anymore or are problems that have multiplied twentyfold. So I thought that Israel is a very dynamic, very rapidly changing society, and a grassroots portrait of the country was necessary to really inform the conversation about it.

As you note in the opening chapter, former Israeli President Reuven Rivlin spoke in a 2015 speech of the need for a “shared Israeliness.” What does that mean to you?

When it comes to Israel, lots of people say, “Oh, the perfect Israel would be if X group was no longer here.” On the Israeli right, they wish the Palestinians would just disappear. On the Israeli left, many wish the Haredim, the ultra-Orthodox, would just vanish one day. That’s not going to happen. Palestinians, Haredim, and secular Jews are all integral parts of Israel. They very much already work and live together and depend on each other, even when they don’t know it. And I think it’s important to proceed with the thought that no one is going anywhere. That’s the principle I think Mr. Rivlin was enunciating. Israel for thousands of years was a place where everybody lived together – Jews, Muslims, Arabs, Europeans, and many others. Not always without tension, of course, not always without conflict, but Israel is important to everyone. So it has to be a shared space, both physically and intellectually.

Given your Jewish American background, how did you navigate your own bias in Israel?

I used my Hebrew skills to get access to lots of different Israelis, but as an American Jew, I had a kind of neutrality and, they would probably say, an ignorance of many issues. So I could ask questions that were very basic. And I used my journalism skills to really just listen. But you’re right that you always have to look out for your own bias. You always have to think about, am I shading the answers to the questions I am asking? And so what I did there was just to try to keep the conversation going until I was sure that I had gotten something that defied my expectations. That was how I knew that I was on the right path.

What progress has Israel made?

If you’d asked me six months ago, I probably would have given a different answer. Today, it looks a lot more hopeful. A lot of Americans see the same old right-wing Israel oppressing Palestinians. I’m not discounting those complaints. But there’s a lot going on under the surface that looks very different, interesting, and hopeful to those who want Israel to recognize its diversity and embrace it meaningfully. When a war breaks out, it’s a horrible experience. Nevertheless, it’s a very resilient society. ... The social fabric in Israel feels a lot stronger within and even between communities. With all the vitriol and with all the hyperbole, there is a very strong impulse for people to live together.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

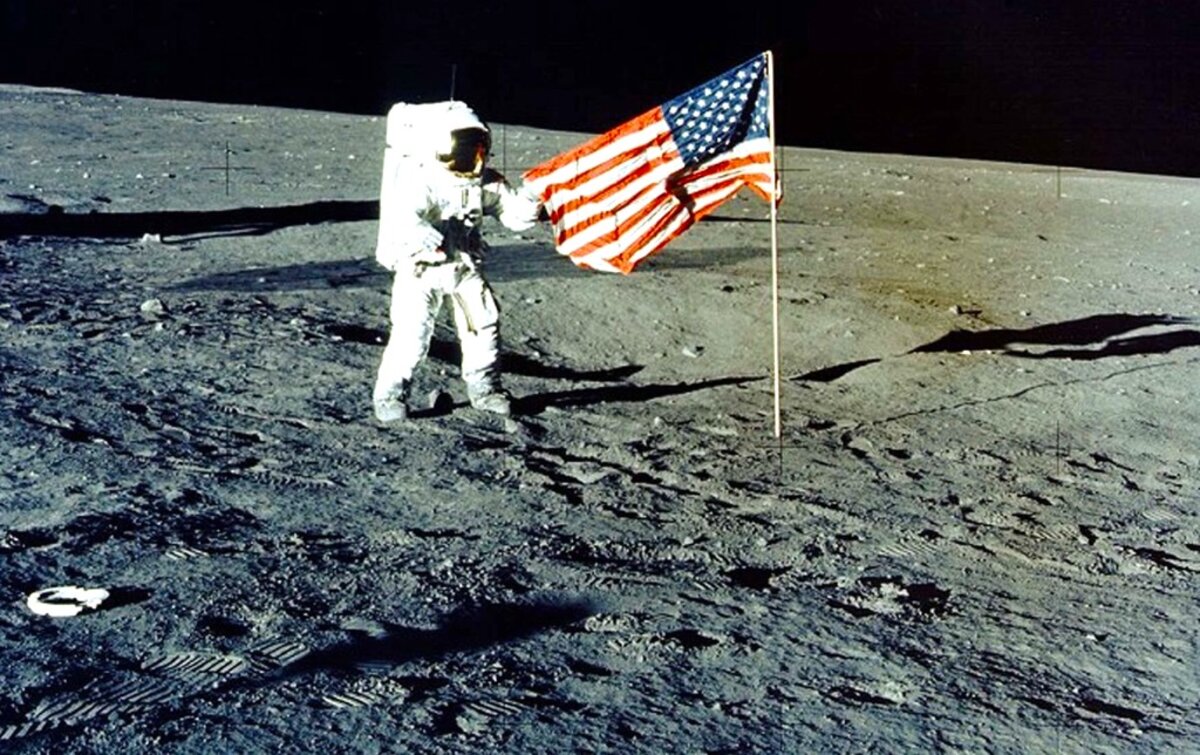

Space 2022: To the moon – and beyond

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Those venturing into space in 2022 have the moon in their eyes.

Why the moon? Haven’t humans been there already?

The truth is it’s an important steppingstone.

“Because the goal is Mars,” Bill Nelson, former U.S. senator and NASA’s new administrator, told The Guardian. “What we can do on the moon is learn how to exist and survive in that hostile environment and only be three or four days away from Earth before we venture out and are months and months from Earth.”

In 2022 Russia, India, Japan, and South Korea will join the United States in sending uncrewed missions to the lunar surface or into orbit around it. The Japanese lander will contain a rover built in the United Arab Emirates.

While it won’t happen this year, billionaire entrepreneurs already envision tourist trips to the moon. But a recent survey shows their clientele could be limited. Three out of 5 (61%) American adults would refuse a trip to the moon even if cost were not a factor, according to a new Axios/Momentive poll.

Most Americans seem content to explore space from an armchair while watching a video screen.

Space 2022: To the moon – and beyond

Those venturing into space in 2022 have the moon in their eyes.

Not that ferrying all sorts of people into orbit and suborbit will be abandoned. 2021 saw not only astronauts and scientists but also several tourists sent skyward for unmatched views of the big, blue marble that is Earth. They were young and old, women and men, various nationalities – even William Shatner, never a real spaceship captain but who played one on TV.

Why the moon? Haven’t humans been there already?

The truth is it’s an important steppingstone.

“Because the goal is Mars,” Bill Nelson, former U.S. senator and NASA’s new administrator, told The Guardian. “What we can do on the moon is learn how to exist and survive in that hostile environment and only be three or four days away from Earth before we venture out and are months and months from Earth.”

.In 2022 Russia, India, Japan, and South Korea will join the United States in sending uncrewed missions to the lunar surface or into orbit around it. The Japanese lander will contain a rover built in the United Arab Emirates.

China has big ambitions in space too, but right now they’re centered closer to Earth. An orbiting Chinese space station, Tiangong, may be finished and become fully operational this year, according to a U.S. intelligence report.

With so much new activity planned in orbital space, by both governments and private enterprise, a need grows to update the 1967 Outer Space Treaty to maintain cooperation. A United Nations resolution passed last November calls for a working group to research new agreements. It will meet twice in 2022.

The purely scientific effort to understand just what’s out there goes on as well. The European Space Agency plans a 2022 launch of an uncrewed probe to explore the moons of Jupiter, a journey that will take nearly eight years.

Christmas Day saw the James Webb Space Telescope flung into space. So far it has flawlessly completed a number of critical steps needed to make it operational later this year.

“This is unbelievable. We are now at a point where we’re about 600,000 miles from Earth, and we actually have a telescope,” said Bill Ochs, the project’s manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

An impressive piece of technology, it will give humanity its best look ever at deep space.

While it won’t happen this year, billionaire entrepreneurs already envision tourist trips to the moon. But a recent survey shows their clientele could be limited. Three out of 5 (61%) American adults would refuse a trip to the moon even if cost were not a factor, according to a new Axios/Momentive poll.

Most Americans seem content with exploring space from an armchair while watching a video screen.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

To pray for peace, I begin with me

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Madora Kibbe

Is it practical to pray for peace? How about starting with ourselves? Because peace has its source in God, it is available to all, and we can strive to express this God-given peace in our daily interactions with others.

To pray for peace, I begin with me

How do we pray for peace? Is prayer even practical in a world where it can seem as though peace is the exception, not the rule?

Praying for peace doesn’t mean asking for a specific result. And it’s never an I win / you lose sort of thing. Praying for peace means starting with God and our willingness to love God and our neighbor. As a result we know and feel that God’s will for everyone is good.

The one prayer Christ Jesus taught his followers, known as the Lord’s Prayer, includes the line, “Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10). And God’s will is always “on earth peace, good will toward men” (Luke 2:14).

At one time Mary Baker Eddy, who founded this news organization, asked her church to pray for peace between Russia and Japan. She wrote, “Dearly Beloved: – I request that every member of The Mother Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, pray each day for the amicable settlement of the war between Russia and Japan; and pray that God bless that great nation and those islands of the sea with peace and prosperity” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 279). Within a couple of months, negotiations began for a peace treaty between the two countries, and a few weeks later it was signed. Many felt Mrs. Eddy’s call to prayer had contributed to this outcome.

It’s noteworthy that Mrs. Eddy didn’t ask Christian Scientists to pray for a winner or a loser. Why would that be?

The answer might be found in that tiny little word “for.” From the perspective of Christian Science, when we pray for a quality of goodness such as peace, we aren’t so much asking or pleading for it, as acknowledging its presence. All that God has is ours, because we are each included in God’s beloved spiritual creation. So when we pray for peace, we are in fact reaching out to understand and evidence what is already present and available to everyone, since peace is an attribute of God, whom we spiritually express.

I find this to be a much more effective way to pray for peace – to persistently yield to the ever-presence and power of divine Love, and to prove this to be practical by starting small and working out from there. There’s a saying: “Think globally, act locally.” To me this means, in terms of prayer, that we include the world in our prayers, while striving to bring to light that ever-present spiritual peace in our daily interactions with others.

Once a family member whom I’d never had a good relationship with called me out of the blue. We had one of the best conversations we’d ever had. I was feeling happy about this, rejoicing that finally we might have a good relationship. But as the conversation ended, the real reason he had called came out: He wanted money, a lot of money, to pay for a storage unit he had filled with things of questionable worth. I was crestfallen. It was tempting to hang up the phone. But I didn’t. I prayed for peace.

Calmly and without reacting, I refused his request, but offered money for some necessities. The call ended on a harmonious note, with no yelling or pleading. But I still felt crushed, and a little bit angry.

v As I prayed more, the thought came to ponder the meaning of a prayer Mrs. Eddy wrote called the “Daily Prayer”: “‘Thy kingdom come;’ let the reign of divine Truth, Life, and Love be established in me, and rule out of me all sin; and may Thy Word enrich the affections of all mankind, and govern them!” (“Manual of The Mother Church,” p. 41).

I was struck by the fact that this prayer does not say, “rule out of her, him, or them all sin.” It says, “rule out of me all sin.” And it says to pray or affirm that God’s Word enriches the affections of everyone.

My relationship with this family member never became postcard perfect, but it did improve over the years, in proportion to my prayers not only for peace but to rule out of whom? – me! – all sin. This included – and still includes – seeing the spiritual nature of everyone, even this family member, as God sees us all: loving, lovable, and loved.

If we don’t pray to see the peace that truly exists, we have war – in our hearts, our homes, our country, our world. So it’s important to do this, letting peace begin with ourselves, as a well-known song encourages.

It may feel like a tough assignment, this prayer for peace, but we can rest in the assurance that the peace of God is always present to understand and prove – here, now, and always.

A message of love

Frost-laced beauty

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at the prominent role women are taking in the new German government. It’s a sea change – even for a society ruled by a female chancellor for 16 years.