- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As pandemic hits another pivot point, so do many Americans

- Mexico’s Mayan Train: Will it hurt those it’s meant to help?

- In a bid to live better, many Brits are breaking with booze

- Blue whales: An acoustic library helps us find what we can’t see

- New series showcases Black marching bands on and off field

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Connecting with history at the flea market

We’ve all heard about the big find at an estate sale or flea market – like the artwork a Massachusetts resident bought for $30 five years ago that experts now say is likely an Albrecht Dürer drawing worth millions.

But for Chelsey Brown, found treasure is something else entirely – as she discovered last year when an old, handwritten letter caught her eye at a New York City flea market, one of many she frequents for her budget interior design business. One dollar later, it was hers, along with a self-imposed challenge: Trace the name on the envelope. She quickly succeeded – transforming an everyday item into a delighted family’s priceless gem and giving herself a new mission.

“It would break my heart when I would be at the flea market ... and pass by a box of family mementos,” Ms. Brown explains via email. “I always knew they should be with their rightful family.”

Ms. Brown pores over genealogical databases and history books to identify the provenance of everything from baby albums to love lockets. She’s connected hundreds of items with owners’ descendants, footing the bill herself. One woman was dumbfounded to receive her grandfather’s World War II ration books. “It was like a present,” a thrilled Mary Jane Scott told The Washington Post. “We spent a lot of Christmases with my grandparents.”

Ms. Brown says such “over the moon” reactions are what keep her going: “These artifacts and heirlooms can tell us things about the past – the era, person, family dynamic, emotions – that documents and records cannot.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As pandemic hits another pivot point, so do many Americans

Amid the recent omicron surge, more people seem to be questioning the value of continued restrictions – and concluding they’re not worth the cost. Parents, in particular, are yearning for normalcy in their children’s lives.

As the pandemic approaches its third year, many weary Americans seem to have reached a mental turning point. While omicron has led to record cases and hospitalizations in recent weeks, putting strain on health care systems, much of the public does not appear to be reacting to this latest surge with high levels of fear. And many seem to be shedding their fear altogether.

Some of the shift is being driven by omicron’s relative mildness compared with other variants, and the fact that vaccines and treatments are now easier to get than ever. It’s also just pandemic fatigue, as patience for restrictions wears thin.

At the same time, there’s a growing awareness of the importance of in-person activities and social contacts – particularly in the lives of children.

Ileana Schinder, an architect in Washington, says she still would prefer to avoid getting COVID-19. But after watching their kids fall behind while shuttling between in-person and virtual school – and seeing things like insufficient testing hamstring the government’s response – she and her husband have concluded they can’t keep letting caution circumscribe their behavior.

“We cannot postpone life,” she says.

As pandemic hits another pivot point, so do many Americans

Ileana Schinder is done making sacrifices.

Since the pandemic began, she and her family have been careful. They’ve missed family celebrations, summer camps, in-person school, and time with friends. An architect in Washington, Ms. Schinder is grateful she’s stayed healthy and still has her job. But over two years, the costs have added up.

So when the omicron variant recently sent caseloads soaring, and she and her husband weighed whether she should stop going to the gym – the one thing she felt was keeping her “head above water” – they quickly agreed: no. Their family is vaccinated, and while they won’t abandon all precautions just yet, it’s time to move forward. They’ve planned a trip to New York in February.

“We cannot postpone life,” she says.

As the pandemic approaches its third year, many weary Americans seem to have reached a similar mental turning point. While omicron has led to record cases and hospitalizations in recent weeks, putting strain on health care systems, much of the public does not appear to be reacting to this latest surge with high levels of fear. And many seem to be shedding their fear altogether.

Some of the shift is being driven by omicron’s relative mildness compared with other variants, and the fact that vaccines and treatments are now easier to get than ever. It’s also just pandemic fatigue, as patience for restrictions wears thin. Paradoxically, the feeling that the virus is “everywhere” has led many to conclude that an overly restrictive approach is no longer worth it.

And in many ways, the pandemic has resulted in growing awareness of something wholly separate: the importance of in-person education and social contacts in the lives of kids. As restrictions since 2020 have taken a toll on children’s education and mental health, Ms. Schinder and others still would prefer to avoid getting COVID-19 – but they’ve concluded they can’t keep letting caution circumscribe their families’ lives, either.

It seems like the nation just got “comfortable with being afraid, and making decisions out of fear,” she says.

Of course, this shift in public attitudes doesn’t mean that letting go of precautions is easy – or that everyone agrees the time to begin doing so is now. For one thing, there’s still plenty of uncertainty about what the future might bring. And omicron itself has brought some of the biggest challenges of the pandemic to date.

Many people spent the holiday season foraging for scarce tests and upgrading their masks. Public health messaging – like the CDC’s revised guidance on isolation – left even the most conscientious citizens feeling awash in confusion. After two years of trying to avoid the virus, many felt a certain amount of whiplash when public health officials started saying that everyone would ultimately encounter it.

“It’s a balancing act between managing uncertainty yourself while maintaining some realistic optimism,” says Steven Taylor, a professor at the University of British Columbia, who studies the psychology of pandemics.

Some medical experts now feel little hope of vanquishing COVID-19 – but say that fact isn’t cause for more pessimism.

Bob Wachter, chair of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, lives in one of the most COVID-19-cautious cities in America, and has taken what he calls a “conservative” approach for most of the pandemic. Yet as soon as the omicron surge passes – and barring an unexpected new variant – he says he’s planning to resume a fairly normal life. That means traveling, dining indoors, only wearing a mask in special settings like airplanes, and visiting more freely with friends.

He says he started planning this return to normal in November, when the United States appeared to have hit a “steady state” with the virus. And while omicron temporarily derailed things, his sense of the bigger picture hasn’t changed.

“Am I going to hunker down for the next 10 years?” Dr. Wachter asks. His view is, “We probably – or at least me personally – will have to accept a mild level of risk.”

“I can’t let this ruin my life”

Anna Boustany, a consultant in Arlington, Virginia, has been diligent in maintaining safety protocols throughout the health crisis. She wears a mask, gets tested whenever exposed, stays careful about her contacts, and is happy to offer proof of vaccination whenever required. Lately, though, those tools have felt less effective.

“I feel like I’ve done everything right,” she says. “But also, my friends who have also done everything right are getting [COVID-19].”

The sheer number of people she knows who’ve been diagnosed recently has made her both less afraid of the virus and less willing to upend her life to avoid it.

“I can’t stress out about this anymore because I’ve spent a year stressing out about it and not being able to do anything, and that was just – to be frank – depressing and sad,” says Ms. Boustany. “I can’t let this ruin my life.”

Many parents in particular have undergone a shift. For the past two years, Ms. Schinder says, the message from officials in her area has been that parents who are willing to make sacrifices can keep their families safe. But after watching her children fall behind while shuttling between in-person and virtual school – and seeing things like insufficient COVID-19 testing hamstring the government’s response – she now feels like those sacrifices don’t make sense.

Public health experts acknowledge that every strategy to limit COVID-19 has a cost. And different people have different risk thresholds, which can change over time.

“We know that people are fatigued, and no one expected that this pandemic would linger on this long,” says Jerome Adams, U.S. surgeon general from 2017 to 2021.

Still, he would encourage people to find a path that balances minimizing harm while maintaining daily life. That’s true even for people who feel burned out after two years of safety measures.

“People really can make a more educated risk assessment about whether or not they want to go to a football game or go out to a restaurant,” says Dr. Adams. “But the challenge is that many of the people who are saying ‘I’m done with the pandemic’ haven’t shown themselves to be willing to do the things that will allow them to go out safely and interact in society with this virus still circulating.”

A new phase, especially for schools

Alex Sherlock follows a strict set of safety measures at work as an environmental planner in Cincinnati. He’s vaccinated, keeps his mask on around people, and keeps his distance. Per company policy, a positive contact cues an immediate 10-day quarantine.

But in his personal life, Mr. Sherlock is less careful. He goes to restaurants and bars and sees friends without much hesitation. Omicron has made him more aware of COVID-19’s spread, but it hasn’t made him feel anxious.

That was true even on Christmas Day last month, when he tested positive. Even though he had to cancel his holiday plans, contact the people he’d seen, and reschedule a lot of work, Mr. Sherlock stands by his approach. He says he’ll continue to follow safety rules whenever required, but he doesn’t feel afraid and doesn’t plan on changing his behavior.

“I would say I’m more or less done,” he says.

Yet others are finding it much harder to let go of caution, after two years of pandemic life.

Marc Gosselin works as school superintendent in Lenox, Massachusetts, where student cases have risen quickly since the holidays. That’s led some parents to keep their children at home – even when healthy.

So this month, Mr. Gosselin wrote an open letter to the community, asking that it trust the school system to take the right steps. Data have shown that almost all transmission, he says, happens outside the classroom. Their schools work to ensure students are socially distant, tested, and masked.

A parent himself, Mr. Gosselin knows how important it is for children to be in school. He also believes the pandemic is entering a new phase, and that families will need to be brought along. He was asked recently whether he would want to know if his child was exposed to the virus. At this point, he says, no.

“We need to just continue to assure parents that their schools are safe and ... to be able to listen to their fears,” he says. “We’re going to have to learn at some point how to live with it.”

Professor Taylor of the University of British Columbia says history shows there’s often a natural progression in pandemics, where governments and institutions begin easing up on restrictions as it becomes clear fewer people are willing to follow them.

“It’s a matter of finding ways that are personally meaningful of toughing out this situation,” he says. “The bottom line is, we need to remind ourselves this will end – pandemics always end.”

Nick Roll contributed to this report.

Mexico’s Mayan Train: Will it hurt those it’s meant to help?

Mexico’s president has a well-honed image of fighting for the little man. But a major infrastructure project in the Yucatan Peninsula offers a window on the competing ambitions of helping vulnerable populations and leaving a legacy of big works.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Levi Bridges Correspondent

Maria Moreno, a nurse in the Yucatan, always planned to move to her family’s home in Citilcum once she retired. But a new train line meant to bring prosperity to Mexico’s long underdeveloped and impoverished south may be pushing her plans off track. Last spring, the national tourism agency told her that her gleaming-white home surrounded by coconut trees would need to be demolished.

The Mayan Train is a pet project of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who won on a populist ticket to create jobs and improve the lives of Mexico’s rural poor and Indigenous populations. But how the project has been carried out – with complaints of limited community consultations, incomplete environmental studies, and threats to displace many of the president’s most vulnerable supporters – has soured some against him, including Ms. Moreno, who voted for Mr. López Obrador back in 2018.

The Mayan Train is meant to extend around the Yucatan Peninsula in a roughly 950-mile loop that links tourism centers like the colonial city of Mérida and the hipster paradise of Tulum. The government estimates it will increase tourism revenue by 20% and create more than 1 million jobs.

The president doesn’t seem swayed by the criticism and pushback on the project, convinced any resistance to the train won’t translate to a dip in support, says Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst. “Indigenous resistance to the project was never an issue [for this administration],” he says.

Mexico’s Mayan Train: Will it hurt those it’s meant to help?

Maria Moreno promised her mother she would always take care of their family home. After her parents died, Ms. Moreno and her husband painted the house’s walls gleaming white and planted a shady grove of coconut trees in the yard.

But the care that went into the home didn’t seem to matter to Mexico’s national tourism agency, Fonatur, when a representative told her last spring that it would need to be demolished. The government is making way for a massive infrastructure project called the Mayan Train, which it wants to build along the power lines that rise beside Ms. Moreno’s home in this steamy village about 170 miles west of Cancún.

The Mayan Train is a pet project of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who won the presidency on a populist ticket to create jobs and improve the lives of Mexico’s rural poor and Indigenous populations. But how the project has been carried out so far – with complaints of limited community consultations, incomplete environmental studies, and threats to displace many of the president’s most vulnerable supporters – has soured some voters against the president, including Ms. Moreno, who voted for him back in 2018.

“He has really deceived us,” says Ms. Moreno, who works as a nurse. “We were excited about change, but now things are going from bad to worse.” Ms. Moreno currently lives in nearby Campeche, but always planned to move back to her family’s home in retirement.

The Mayan Train is meant to extend around the Yucatan Peninsula in a roughly 950-mile loop that links tourism centers like the colonial city of Mérida and the hipster paradise of Tulum. Mr. López Obrador promotes the train as a way to reduce poverty in the Yucatan: The government estimates it will increase tourism revenue by 20% and create more than 1 million jobs.

Most of the train will run on existing tracks that need modernizing. The government plans to construct the rest on public and private land, which means eviction for some in Mexico’s Yucatan. The government, which broke ground on the project in 2020, would not provide specific numbers on how many households it will relocate, saying the estimate of homes that could be affected is constantly changing. But Kalycho Escoffié, a lawyer who assists families facing displacement, estimates more than 2,000 homes will be demolished to clear space for the train.

That’s hit at the hope some in Mexico felt in voting for Mr. López Obrador, who has built his personal brand on fighting for the little man and rejecting corruption. But Mr. López Obrador is convinced any resistance to the train won’t translate into a significant dip in support at the polls, says Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst whose podcast “Un Poco de Contexto” featured an episode about the Mayan Train.

“Construction started without securing the buy-in of Indigenous communities,” says Mr. Bravo. “Indigenous resistance to the project was never an issue [for this administration].”

Divided communities

The Mayan Train has become so contentious it’s divided some friends and family over how to address Mexico’s stark inequality.

The largely rural south has historically experienced higher rates of poverty and unemployment than the more industrialized north. And some take issue with the project’s very name, calling it an act of cultural appropriation, commercializing Mayan culture without including Indigenous communities in the plans.

Francisco Colle, a member of the Mayan community in the town of Hóctun, likens the president’s ambitious focus on infrastructure to the United States’ New Deal. He foresees construction jobs that will allow disadvantaged communities to put food on the table.

“Now a lot of rich people [in Mexico] are mad because they’re no longer getting a piece of the cake,” says Mr. Colle.

But others say it’s just another project dreamed up by the powerful, who will reap all the benefits. The train has backing from Mexican scion Carlos Slim, one of the richest people in the world.

“We’re living in the modern colonial era,” says Juan, who is Mayan and declined to give his last name because he fears retaliation for his opposition to the train. He calls it a continuation of the Spanish conquest, in which outsiders plunder Indigenous lands. “None of the profits from the Mayan Train will stay in our communities.”

The government is obligated to consult Indigenous communities prior to building new projects on their land, according to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, which Mexico has ratified. Fonatur has repeatedly come under fire for not holding these consultations.

Javier Velázquez Moctezuma, Fonatur’s scientific coordinator for the Mayan Train, says the government complied with their obligations, organizing meetings in 15 regions along the train’s route with interpreters who translated into Indigenous languages.

“Many people [told us] they wanted the train, they wanted development, they wanted to have opportunities,” Mr. Velázquez says, acknowledging the government hasn’t held consultations in every town where the train will operate.

With the end of Mr. López Obrador’s term looming in 2024, Mr. Velázquez says Fonatur must work to finish the train quickly. The train is expected to cost nearly $10 billion. He maintains any disadvantages of speeding the project’s construction are overshadowed by benefits.

But the collapse of Line 12 of Mexico City’s metro last spring casts doubt on a rushed project. Mariano Sánchez-Talanquer, a political science professor at El Colegio de México, says authorities rushed to complete that metro line – and the project was carried out by a company owned by Mr. Slim that is also involved in constructing a section of the Mayan Train.

“You can’t help but think the same type of problems with the metro could be replicated,” Dr. Sánchez-Talanquer says.

Recently Mexico’s government took the bold step of passing a measure that would expedite infrastructure projects in the name of “public interest and national security.” Critics say the move undermines regulatory measures and makes public spending less transparent, while allowing AMLO, as the president is often referred, to steamroll into existence big projects like the Mayan Train or a new Mexico City airport. He has more than 60% approval.

“Despite some local disapproval of the train, I think the president is calculating that his popularity gives him no reason to change course,” says Dr. Sánchez-Talanquer.

Resisting the train

On a Sunday morning last summer, nearly two-dozen residents from the town of Kimbilá gathered in the shade of the municipal palace. They brainstormed ways to organize their community in order to gain greater say in the train’s construction. Locals sat in a circle across from an aging colonial church and shops selling the region’s colorful embroidery. Organizers say one strategy they’re using to appeal to AMLO supporters is to try and underscore that their discontent isn’t blanket opposition.

“I voted for López Obrador, and I’ll probably vote for [his party] Morena again, but that doesn’t mean that I agree with how they’re implementing the Mayan Train,” a software engineer named Juan Mex told the small crowd.

Chief among Mr. Mex’s concerns is the fact that Fonatur has not held a local consultation with his community in Kimbilá. The government plans to build part of the train in the local ejido – collective farmland.

Representatives from Fonatur did come to Kimbilá, but Mr. Mex says the government only met with select members of the ejido in a series of closed-door sessions. Everyone else was excluded, even though the entire community would be potentially affected.

Mr. Mex and others decided to fight for their right to attend, spending the summer pressuring authorities to give them a seat at the table. Despite their efforts, they remained sidelined: The government paid the ejido members 5,000 pesos each – about $250 – for the right to construct the train, locals say.

“They’ll spend [that] in one month,” says Jorge Fernández Mendiburu, a lawyer with the human rights group Indignación, which has won several injunctions to stop construction on parts of the train. “It’s an insult for those who live in poverty.”

Still, the rollout has done little to dissuade Mr. López Obrador’s core supporters.

Mr. Colle, a former immigrant living in California, decided not to try to return to the U.S. after Mr. López Obrador became president. For the first time in his life, he says he feels he has a future here. He wants to open a business near the train and take advantage of the increased foot traffic he expects to come with the train line.

“If Mexico keeps going in the same direction,” Mr. Colle says, “then in 20 years, we’ll probably be like Canada.”

In a bid to live better, many Brits are breaking with booze

Drinking has long been interwoven with British culture. But in a major shift, many people are swearing off alcohol, no longer seeing it as a necessary tool for social acceptance and having fun.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Despite their reputation for excessive drinking, more Britons than ever are quitting alcohol altogether, with a third of people quitting since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is a sign of a major cultural shift, rooted in the urge for healthier lifestyles and “meaningful connections,” says Jo Ferbrache, a blogger and public speaker on sobriety.

While the pandemic spurred many to alter habits, Britain’s teetotal movement has risen steadily since the turn of the millennium. According to campaign group Alcohol Change UK, the overall amount of alcohol consumed in the United Kingdom, the proportion of people drinking, and the amount drinkers say they consume have all fallen since 2005.

This trend is especially high among younger drinkers. In 2001, about 10% of 16-to-24-year-olds classed themselves as alcohol-abstinent. By 2016, that had risen to nearly a quarter.

Much of that may be driven by young people’s better understanding of the importance of physical and mental health, says Andrew Misell, director for Wales at Alcohol Change UK.

“Young people have seen the boomer generation and Generation X rely on alcohol and have rebelled against that,” he says.

In a bid to live better, many Brits are breaking with booze

Whenever Katrina Cliffe reached for a glass of wine during Britain’s first lockdown in 2020, it was done as “a reward to get through or survive the day.” Running a business and caring for her two children at home meant she was always “looking for an excuse,” however small in quantity, to drink.

“I said to myself things need to change. I can’t just keep existing,” says the entrepreneur from Huddersfield, in northern England. Like many Britons, she decided to give up alcohol for “Dry January” last year. Quitting alcohol gave her another chance to enjoy her passion for ice skating without fatigue.

“It was about taking control of the situation rather than the situation taking control of me,” she says. Ms. Cliffe has since gone a whole year alcohol-free and now enjoys a new lease of energy.

Despite their reputation for excessive drinking, more Britons than ever are quitting alcohol altogether, with a third of people quitting since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is a sign of a major cultural shift, rooted in the urge for healthier lifestyles and “meaningful connections,” says Jo Ferbrache, a blogger and public speaker on sobriety, self-nicknamed Sober Jo.

“A movement is happening with more and more people standing up to say that they are proud not to drink alcohol, sharing the joys of sobriety or drinking mindfully, and slowly moving away from the stigma that not drinking means that you are boring,” she says.

A rebellion against alcohol?

While the pandemic spurred many, like Ms. Cliffe, to alter habits, Britain’s teetotal movement has risen steadily since the turn of the millennium. According to campaign group Alcohol Change UK, the overall amount of alcohol consumed in the United Kingdom, the proportion of people drinking, and the amount drinkers say they consume have all fallen since 2005.

This trend is especially high among younger drinkers. In 2001, about 10% of 16-to-24-year-olds classed themselves as alcohol-abstinent. By 2016, that had risen to nearly a quarter.

Much of that may be driven by young people’s better understanding, when compared to older generations, of the importance of physical and mental health, says Andrew Misell, director for Wales at Alcohol Change UK.

“Young people have seen the boomer generation and Generation X rely on alcohol and have rebelled against that,” he says. Multiculturalism, too, has opened up doors for people to socialize with nondrinkers from diverse communities such as Britain’s Muslim population.

Yet many face challenges of overcoming deep-rooted expectations and habits. London-born Victoria Kingsland, who quit drinking three years ago, says that it is widely accepted that people drink to “get drunk,” especially in the U.K.

In office spaces, there is often talk about needing a glass of wine at night to wind down.

“That mentality shows an unhealthy relationship with alcohol. ... You convince yourself it’s fine and that everyone does it,” she says.

The dry-drinking market

Nondrinking entrepreneurs are already aiming to redress the balance with alcohol-free alternatives, once the preserve of a niche industry.

Having quit alcohol to aid the chance of conceiving a child, Stuart Elkington saw his “month by month” sober life snowball into finding alcohol-free alternatives. Inspired by his time living in Spain, where drinking such alternatives are “commonplace,” he set up his own wholesale business, Drydrinker, in 2016, selling alternative premium drinks.

Mr. Elkington’s mission to encourage “dry drinks” as a “lifestyle choice as well as a consumer choice” has gained newfound momentum. At the start of the new year, he helped open one of London’s first alcohol-free off-licences (the British equivalent of a liquor store), one of two new independent shops that have sprung up at the start of 2022.

Supermarkets are keen too. Sainsbury’s, one of Britain’s biggest groceries, opened up an experimental “no-alcohol pub” in 2019. The number of products in its own no-beer alternative line has grown by 300% in the past year.

“There’s been a real gold rush,” says Mr. Elkington, now a father to two children and a self-professed dry drinker for eight years. “If you weren’t drinking 10 years ago, people assumed you were ill.”

A shift in normalizing, and redefining, sobriety is underway. Not so long ago, sobriety in the U.K. was “associated with people with addictions and serious problems,” says Mr. Misell. “Now it’s associated with people who just want a change in lifestyle, without experiencing life-changing difficulties.”

Challenges remain, with increasing concern that women in their late 20s and 30s, in particular, are drinking more frequently and heavily as a coping mechanism at home, as well as increasingly taking part in high-end professions with drinking cultures such as finance.

But for Sober Jo, even the alcohol-free alternatives are not needed so much anymore three years into her sobriety.

“They’re more of a treat now,” says Ms. Ferbrache. “Give me a cup of tea anytime.”

Blue whales: An acoustic library helps us find what we can’t see

Antarctic blue whales are hard to find, but easier to hear. Focusing on their sounds, researchers are using collaboration and artificial intelligence to learn about Earth’s largest mammals. Be sure to click on the deep read and scroll down to hear examples of the whales’ communications.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By W.S. Roberts Correspondent

Moored around Antarctica is a loose ring of passive acoustic monitoring devices, or PAMs, deployed by various academic institutions. Released by oceanographic research vessels, the devices sink to the seafloor where they record a remote and often hostile realm that is practically out of reach of scientists. After about a year, a returning ship plays a coded message that trips a wireless trigger and frees the PAM recording to the surface.

They’re listening for the Antarctic blue whale – the largest mammal on Earth, and critically endangered.

“There’s a small number of sightings of them, but they make really loud noises that can be detected over really large ranges,” says Brian Miller, a marine mammal acoustician at the Australian Antarctic Division in Kingston, Australia.

PAMs are an excellent method to get to know them better, and perhaps get new insight into their populations and migration. Dr. Miller says, “It seems like listening for these animals might be a better option for monitoring their recovery and their status ... than spending lots of money to send lots of ships with visual observers to look for them.”

Blue whales: An acoustic library helps us find what we can’t see

Reverberating through the ice shelves and gyres of the Southern Ocean are the undersongs of the largest animal that has ever lived on this planet, the Antarctic blue whale. Telling tales of the hunt for krill, of navigation and seduction, these tunes can carry for hundreds of miles.

And the world is listening: Moored around Antarctica is a loose ring of passive acoustic monitoring devices, or PAMs, deployed by various academic institutions. Released by oceanographic research vessels, the devices sink to the seafloor where they record a remote and often hostile realm that is practically out of reach of scientists. After about a year, a returning ship plays a coded message that trips a wireless trigger and frees the PAM recording to the surface.

“The idea here is that these animals are really rarely encountered on oceangoing voyages through visual surveys. There’s a small number of sightings of them, but they make really loud noises that can be detected over really large ranges,” says Brian Miller, a marine mammal acoustician at the Australian Antarctic Division in Kingston, Australia.

After industrial whaling annihilated 99% of the blue whale population during the 20th century, the International Whaling Commission banned hunting in 1966. The critically endangered Antarctic blue whale is the largest of the species, with some reaching 110 feet in length and 330,000 pounds. Scientists estimate that about 3,000 individuals remain. And although blue whales may be well known, they are not well understood.

PAMs are an excellent method to get to know them better, Dr. Miller says. “It seems like listening for these animals might be a better option for monitoring their recovery and their status ... than spending lots of money to send lots of ships with visual observers to look for them.”

Antarctic blue whale D-calls

Both sexes produce what researchers label “D” calls such as these, which are believed to be used for social contact, especially during foraging. The noises here are sped up eight times. Headphones are recommended. (Credit for this and subsequent audio: Brian Miller/Australian Antarctic Division)

When a PAM recording returns to its laboratory, analysts plumb its depths for sounds that can help determine the blue whale’s migratory paths and population, as well as new insights into its life. And yet, a year’s worth of sound also requires ... a year’s worth of listening.

To solve the prohibitive task of deciphering such a huge data set, cetologists have allied with computer scientists to develop custom software algorithms – instructions based on the patterns of previous whale sounds scripted into computer code – that can rapidly swim through oceans of data to home in on whale calls. Considering the constrained resources and diverse skills required for such work, these bespoke software packages may be only partially effective – or are poorly distributed among researchers.

So, to pool resources, unite international efforts, and present a broad range of recordings to test automated algorithms for the study of Antarctic blue whales (and fin whales, another species of concern), the scientific community has been broadening its efforts. The Acoustic Trends Working Group – funded through the International Whaling Commission’s Southern Ocean Research Partnership – has developed the online open-access Acoustic Trends Annotated Library.

Dr. Miller, who served as project coordinator and lead author of the paper announcing the library, worked with colleagues to gather 2,000 hours of acoustic data from five nations, representing five separate years and instruments in each of the four circumpolar Antarctic regions. Next, a coterie of highly skilled analysts with extensive experience in identifying whale calls made 105,161 annotations identifying sound types, durations, and frequencies. Divided into hourlong blocks, the recordings were converted into standard .wav audio format and coupled with annotated text files.

Fin whale FM downsweeps

Fin whale “downsweep” notes: These repeated sounds form a song produced only by males during the breeding season.

While blue whale calls can exceed 180 decibels – louder than the roar of jet airplane – most of their sounds are infrasonic, meaning the frequency of their sound waves falls below the threshold of human hearing. So, to “hear” a blue whale, analysts watch for its sounds by feeding recordings into spectrogram software, which in turn renders sound signals into two-dimensional representations of waves across their computer screens.

“It is quite tricky,” says Emmanuelle Leroy, a bioacoustician who helped develop the digital library, about the annotating process. Variation in marking the boundaries and frequencies of calls is common between annotators and even for a single person when repeating work, she says. Improperly marking a sound can result in algorithms detecting false positives or missing whale sounds altogether.

Because the library aims to provide the “ground truth” data set for scientists the world over to test their algorithms against, the team developed strict annotation parameters. Dr. Leroy says she enjoys looking at acoustic data, but the time she spent was taxing. “Of course, you dream of [annotating] during the night,” she laughs. “You see .wav vocalizations everywhere.”

Background interference, such as the weird whining and cracking of polar ice, is common in the recordings but also important in training algorithms to cut through the clamor of the sea and identify targeted sounds. “It comes down to diversity. If you want to analyze diverse data sets, you’ve got to train your algorithms on diverse data sets,” says Dr. Miller.

The acoustic library is already being used by researchers at the University of Concepción in Chile to compare blue and fin whale vocalizations over time and at different sites. And Shyam Madhusudhana, a postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University’s Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics, is using the library in the development of a global baleen whale sound detector, whereby researchers can simply drop in their own data sets to rapidly identify calls. He is applying deep-learning computer software to construct the detector.

Already successful in automatic speech recognition, deep learning mimics the way humans learn. Employing layers of increasingly complex computing system nodes, called artificial neural networks, the technique synthesizes data in the form of continuous examples – as opposed to linear instruction – to arrive at an answer. This method, which should more accurately identify whale calls across distance and throughout turbulent soundscapes, requires huge caches of training data. Hence the whale acoustic library, which, Dr. Madhusudhana says, is “vital for this field.”

Unlike other cetaceans, such as the humpback whale with its assortment of higher-frequency moans, shrieks, and bellows – and which Dr. Miller calls “the jazz improv singers of the whale world” – blue whales produce sounds that are simpler and can be reduced to two classifications with a medley of underlying units and phrases. Only males sing, presumably to attract a mate, whereas both sexes produce downsweeping “D” calls, thought to be used for social contact. Dr. Miller refers to the blue whale sounds as the “rhythm section.”

Antarctic blue whale Z-call (8x speed)

The repetitive ”Z” call: There are only a few sounds in the Antarctic blue whale repertoire. This call (named “Z” for the look of its sound pattern rendered visually) rolls into a song sung only by males.

And yet for all its weight and sonance, the animal remains an enigma. “Blue whales are really mysterious,” says Dr. Miller. “Hundreds of thousands of them were killed during whaling, and we learned so little about them. ... We still, to this day, don’t know where the breeding grounds of the Antarctic blue whales are.”

Dr. Leroy, who is now on Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean researching the vocal repertoires of local cetaceans, agrees about the mystery. While she says that acoustics offer vital tools for understanding the seasonal and geographic movements of the Antarctic blue whale, there is still much to learn.

“We are blind,” says Dr. Leroy. “We see the songs, but we are blind.”

Television

New series showcases Black marching bands on and off field

Joining supportive groups in college can be crucial to making it to graduation. Docuseries “March” explores how being a band member at a historically Black university challenges and uplifts students.

-

By Candace McDuffie Correspondent

New series showcases Black marching bands on and off field

“March,” one of the CW’s newest shows, chronicles college students at Prairie View A&M University whose passion for music shapes how they navigate their lives. Viewers are privy to an up-close look at what it takes to participate in one of the top marching bands at a historically Black university.

We have had glimpses into this culture before, with movies like “Drumline” (2002) and “Stomp the Yard” (2007) bringing fictional versions to mainstream audiences. And for her 2018 Coachella performance, Beyoncé – the first Black woman to headline the festival – paid homage to the uniqueness of HBCU culture by having a full marching band and majorette dancers onstage with her.

“March” (TV-PG), with its classic reality show format, paints a fuller picture of the complexities of being a part of such a competitive and high-energy activity. The series also offers a window on the college experience, including the demographics of today’s students and how they are coping and supporting each other after months of pandemic disruptions.

In addition to the band’s sweaty, late-night rehearsals – showcasing the drive and determination of the team’s 300-plus members who go by the name The Marching Storm – we also observe the group confronting the struggles of adolescence together. The director of bands at the Prairie View, Texas, school, Dr. Tim Zachery, is a cornerstone of wisdom the students go to in times of confusion, sadness, and concern. Drum majors Aaron and Jalen, along with Kaylan, captain of the Black Foxes dance team, are among the experienced leaders who guide the younger members.

There is plenty of talk about becoming the No. 1 HBCU marching band in the nation. (A recent low ranking from ESPN’s website “The Undefeated” leaves a sour taste in everyone’s mouth.) But we also see how these young Black and Latino folks are coming into their own.

There’s Cardavian, a nonbinary euphonium player and entrepreneur who specializes in culinary treats and also sells hair, lashes, and durags. (“You should call me what I look like,” she says in an on-camera interview, referring to pronouns.) Not only is she charismatic, but she also brings a specific social issue to the forefront of the show.

Cardavian is convinced her friends are using her for home-cooked meals when it’s convenient, then ignoring her when it’s not. She is certain that gender plays a significant role in this dynamic – we see Cardavian dressed as both male and female in various photos. And she reveals that there was a bit of drama in The Marching Storm that led to her being dismissed from the group. Cardavian confides in a friend about wanting to be back in the band – and ultimately her community. Hopefully, we will see how this pans out as the season progresses. (Only the first episode was available for review.)

Then there is the story of Tre, a bass drummer who is working hard to balance fatherhood with an academic schedule. Despite the difficulty he has acclimating to this new lifestyle, he remains adamant about being a good father to his daughter, since he didn’t have a dad growing up. Breaking generational patterns in Black families is not easy, but Tre feels confident he can do so with the support of his peers. His good friend Martayvia, who plays piccolo, has become a sister figure to him, despite some initial tension. Not only does she serve as a shoulder to cry on, but she also offers to help take care of his child whenever he needs her to. It’s one of the most touching moments of the debut episode, the first of eight.

Nehemiah, a mellophone player and aspiring leader, offers another of the show’s strong personalities. His inherent intensity makes him both a creative force and a natural antagonist. Drum major Jalen offers him tips for motivating his peers. Will he adapt?

The fact that this cultural ritual of music and dance bonds these groups of people, who come from various backgrounds and upbringings, really drives home the importance of community. Excellence on the field may be the team’s goal, but what makes members of The Marching Storm winners already is their innate ability to be there for one another.

“March” airs Mondays on the CW starting Jan. 24. The program moves to Sundays on Feb. 27. Check local listings for times.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

In Honduras, a promise kept

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On the eve of her inauguration as president of Honduras, Xiomara Castro has given a glimpse of what integrity in government might look like. To form a majority in the Congress, Ms. Castro promised the leadership of the legislature to a smaller party. A faction within her party broke ranks on Friday and tried to install one of their own instead. To do so, they joined sides with the outgoing ruling party. “The Lady,” as Ms. Castro is known, said no. A scuffle ensued on the floor, and she expelled the rebellious members from her party.

The incoming president is standing up to the kind of political pacts that have enabled corruption to thrive, says Roberto Herrera Cáceres, former state commissioner for human rights.

A former first lady whose husband, former President Manuel Zelaya, was ousted in a military coup in 2009, Ms. Castro has promised “a government of reconciliation” following years of violent repression under the outgoing president, Juan Orlando Hernandez.

“I extend my hand to my opponents because I have no enemies,” she said after winning the election. “I will call for a dialogue ... with all sectors.”

In Honduras, a promise kept

Since Xiomara Castro was elected president of Honduras last November, one persistent question has been whether she will be able to govern once she takes office. Honduras is one of the most violent and corrupt places on earth. For the past eight years it has been run by a president with deep family ties to cocaine trafficking. “Impunity,” according to Human Rights Watch, “remains the norm.”

Ms. Castro vowed during her campaign to change that. Now, on the eve of her inauguration on Thursday, citizens in this Central American country are getting a glimpse of what integrity in government might look like under their first female president.

To form a majority alliance in the Congress, Ms. Castro promised the leadership of the legislature to a smaller party. A faction within her party broke ranks on Friday and tried to install one of their own instead. To do so, they joined sides with the outgoing ruling party. “The Lady,” as Ms. Castro is known, said no. A scuffle ensued on the floor, and she expelled the rebellious members from her party.

The split has caused a constitutional crisis. With lawmakers backing two different leaders of Congress, neither legitimately installed, Ms. Castro’s reform agenda faces stiff head winds. But observers see an upside. The incoming president is standing up to the kind of political pacts that have enabled corruption to thrive, says Roberto Herrera Cáceres, former state commissioner for human rights. That offers hope that “we will return to constitutional norms so we can realize the common goal of dignity, common welfare, and social justice,” he told reporters Sunday.

A former first lady whose husband, former President Manuel Zelaya, was ousted in a military coup in 2009, Ms. Castro has promised “a government of reconciliation” following years of violent repression under the outgoing president, Juan Orlando Hernandez.

“I extend my hand to my opponents because I have no enemies,” she said after winning the election. “I will call for a dialogue … with all sectors.”

She vowed to abolish the military police and restore judicial independence and has invited the United Nations to set up an independent anti-graft unit. Her social priorities include protecting the rights of women, the LGBTQ community, and Indigenous groups.

Those intentions have endeared Ms. Castro to the Biden administration, which seeks a more stable partner in addressing the root causes of emigration from Central America. From 2015 to 2020, according to the United Nations, emigration from Honduras increased by 530%. Between 2012 and 2021, food insecurity in Honduras rose 35% – the fastest in Central America.

The latest AmericasBarometer report from Vanderbilt University found that people in the region say the motives of migration include violence, corruption, and a lack of economic opportunity and education. But the 2021 report also found a silver lining: a resiliency in public support of democracy.

“The public strongly asserts its desire to have a voice in politics. Yet, people are skeptical of electoral democracy’s capacity to deliver,” the study said. “What would it take to increase confidence in electoral democracy? ... Clean governance.”

In a country where people are accustomed to distrusting politicians, Ms. Castro’s refusal to renege on a promise may help shift a culture of corruption and impunity. To those worried that she may have put her presidency at risk before it even starts, she has a response: Without integrity there is no governance.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

When we walk into the room

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By T. Michael Fish

At times we may find ourselves dreading an impending discussion about a tough topic, or doubtful that a meeting will yield a harmonious resolution. Recognizing everybody’s God-given ability to express kindness, integrity, and intelligence offers a solid starting point for peace and progress.

When we walk into the room

When I was employed by the United States Naval Air Systems Command years ago, I worked with the military. Many tough decisions had to be made, and at times in meetings the room could be filled with fear, self-righteousness, jealousy, and anger.

One time we had an emergency meeting when one of our facilities came under alert. I dreaded going into the room, but before I entered, I remembered something the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote in her “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896”: “We should measure our love for God by our love for man; and our sense of Science will be measured by our obedience to God, – fulfilling the law of Love, doing good to all; imparting, so far as we reflect them, Truth, Life, and Love to all within the radius of our atmosphere of thought” (p. 12).

The Bible conveys that God is Truth, Life, and Love, and that we are made in God’s image. So we all have an innate ability to express qualities such as kindness, loveliness, honesty, and energy. We reflect these qualities, whose source is God.

It’s like if you look at a lake and see a reflection of a nearby mountain. The mountain is not really in the lake, but you’re glimpsing something of the mountain in the reflection. We are not God, but in our true, spiritual nature we reflect what God is.

I recognized right then that we can’t fulfill the law of divine Love by walking into a room clinging to fear or doubt, or with a mistaken view of the individuals there. To truly love our fellow men and women means seeing them not as unavoidably arrogant, afraid, willful, or angry, but in the way that Jesus taught. That is, identifying them as God’s creation, the intelligent, peaceful, and harmonious offspring of God, Spirit – recognizing and loving them in their true, spiritual light. Not just with human affection, but acknowledging the good they express as God’s children.

So that’s what I did. As I entered that meeting room, I held with conviction to the spiritual fact of everyone as God’s child. This made it easier to let go of my own willfulness about making something productive happen, and instead to let God show me what He saw in the people in that room: Love’s perfect man and woman.

This helped me be more alert to the intelligence being expressed by one individual, justice by another, sincerity by another, harmony by another, kindness by another. And it ended up being a very peaceful meeting, with every decision being made harmoniously. I truly felt God with us all in that room, uplifting the “atmosphere of thought.”

That experience years ago changed me. From that point on, I’ve started going into every meeting by first acknowledging that God is in the room (so to speak), and so Love is already there, peace is already there, Truth is already there, ready to be expressed and felt. I’ve found myself wondering less about what each outcome is going to be, and instead knowing that it can be reached harmoniously because all involved are capable of expressing trust, harmony, and love. It’s not about bringing a personal agenda into the room, but about recognizing what God already has in the room.

Every time we walk into a room, we can prayerfully rejoice that God is present. And each of us can bring into every room, each day, an honest effort to better reflect the Divine.

A message of love

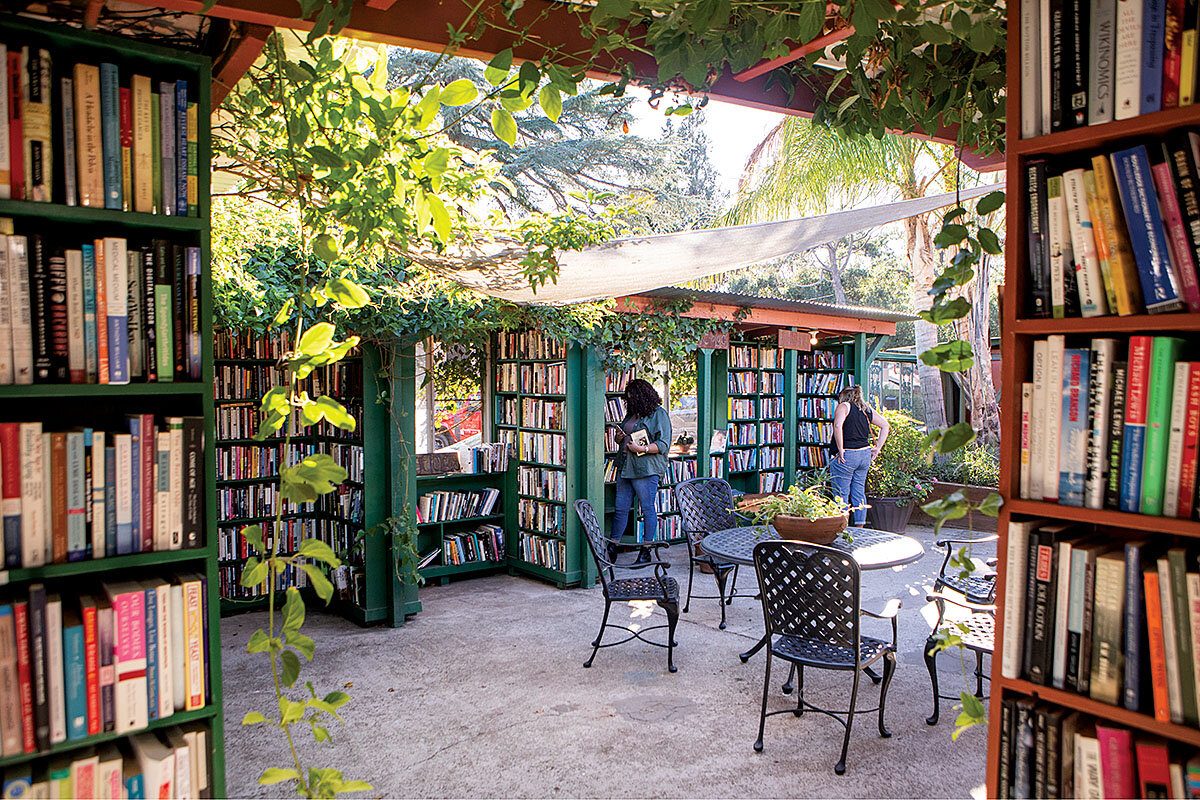

Where book lovers browse stacks under the sky

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, come back for the first of several stories from Afghanistan, where staff writer Scott Peterson has just spent nearly two weeks looking at everything from the humanitarian crisis to how daily life has changed under the Taliban.