- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Can new boundaries create better neighbors? Secession picks up steam.

- With Russian hackers in mind, NATO takes hard look at cyber strategy

- Athletes go, Biden stays: Will the Olympics boycott carry weight?

- Cuban kids don’t care about grandpa’s revolution – they want jobs

- Storefront history: Amman museum celebrates lost art of signage

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When supply-chain holdups hit the dinner table

I coped with the toilet paper shortage, learned patience with the week-after-week no-show of Lysol disinfectant wipes, and put off buying a new laptop because of the global chip shortage.

But Chinese food? Really?

For the second time in three weeks, I’ve had to search high and low for hoisin sauce and water chestnuts – key ingredients for a favorite meal for our adopted Chinese daughters. My two go-to grocery stores had given up trying for that full-but-shallow look where the shelves are neatly stacked with goods exactly one bottle or can deep. Instead, almost-bare shelves have been strewn with a mishmash of Asian food products in no particular order, like a toddler’s bedroom floor after playtime.

Maybe it was just hoarders anxious they wouldn’t have enough for yesterday’s Lunar New Year celebrations. But for me, it’s a personal metaphor for the supply-chain fix we’re in. Yes, manufacturers and retailers have risen to the occasion to keep stores mostly filled. But the pandemic has stretched the infrastructure that connects them. Nearly two years into the pandemic, a labor shortage – based in part on fear of going back to work – means a backlog of container ships in U.S. ports, too few truck drivers to get the goods to stores, and a lack of retail employees to stock the shelves with those goods.

This was the year supply chains were supposed to get back to normal. But I’m not seeing it yet. Typically, a grocery store will be out of stock on 5% to 10% of its items, according to the Consumer Brands Association. As of Sunday, unavailability was averaging 15%. Now comes news that China’s COVID-related lockdowns, already causing food shortages for some Chinese, may trigger more supply-chain woes worldwide.

A happy Chinese New Year? I hope so.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Can new boundaries create better neighbors? Secession picks up steam.

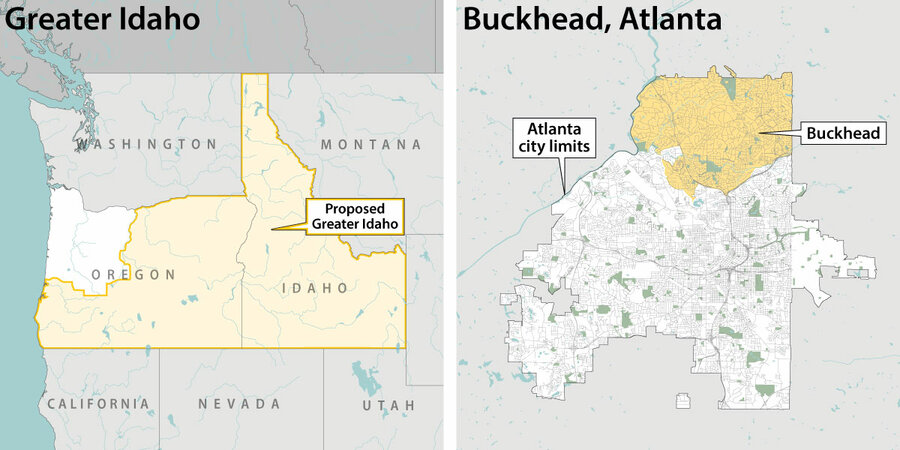

Values and identity are key to many of the movements motivated by America’s growing urban-rural divide. As cities have expanded, some in rural areas are feeling left behind – and looking to “move” without giving up their homes.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

A few years ago, Mike McCarter saw a flyer for a community meeting near his home in rural La Pine, Oregon. He found a group of Oregonians who shared his frustrations with the state’s direction. Their solution? Become Idaho.

“Rural Oregon’s values line up much better with Idaho’s values – traditional values of faith, family freedom, independence,” says Mr. McCarter.

He and the Greater Idaho movement propose shifting most of Eastern Oregon to its neighbor. Mr. McCarter, a born and raised Oregonian, says people like him need a Plan B.

From Maryland to Oregon to Atlanta, some residents who don’t feel represented by their city and state governments don’t only want new elected officials. They want entirely new cities and states. These new secession movements have different motives but share a sense of alienation with their governments. They agree with majority rule. They just want a different majority ruling.

Practical or not, these movements challenge core ideas of American community. Their supporters often feel ignored by elected leaders and fellow citizens. To an extent, they’ve given up trying to resolve differences with people who disagree.

“We don’t look at it necessarily as a political issue,” Mr. McCarter says. “It’s more ... value and cultural differences. There is a dramatic difference between urban and rural and the way people look at things.”

Can new boundaries create better neighbors? Secession picks up steam.

Since Bill White moved to Atlanta’s northern district of Buckhead in 2018, he and many of his neighbors have watched the city grow more violent and more tense.

The police shooting of Rayshard Brooks, soon after George Floyd’s murder in 2020, incited unrest and temporary riots. Homicides jumped 60% during the pandemic, from 99 in 2019 to nearly 160 in 2020 and 2021. Buckhead residents – whiter and wealthier than the median Atlantan – feel afraid, says Mr. White. Some of his neighbors leave the house armed.

As for Mr. White, he wants to leave Atlanta altogether. He just doesn’t want to move. Instead, Mr. White has spent the past year arguing that Buckhead should be its own city – the first in Georgia born of secession. Founding and chairing the Buckhead City Committee, Mr. White has built a team of allies in the district and the state Senate, though none of them represent Atlanta.

Experts are skeptical that cityhood would help the group’s pledged goals of lowering taxes and crime. Critics call the movement district-level white fright. Regardless of its success looking increasingly unlikely, the Buckhead City movement is an example of a political Hail Mary being tossed more often in America today.

From Maryland to Oregon to Atlanta, some residents who don’t feel represented by their city and state governments don’t only want new elected officials. They want entirely new cities and states. These new secession movements have different motives but share a sense of alienation with their governments. They agree with majority rule. They just want a different majority ruling.

Practical or not, these movements challenge core ideas of American community. Their supporters often feel ignored by elected leaders and fellow citizens. To an extent, they’ve given up trying to resolve differences with people who disagree. But reconciliation can be important, and creating a new community has its own complications. In a country with existing boundaries, forming a new one requires breaking up another.

“Because the idea of separation as a solution to political disputes is so deeply ingrained in American history, it’s not going to go away,” says Richard Kreitner, author of “Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union.” “It’s always going to be like a tool available for American discontents.”

America – a history of breakups

There have been few times in American history without some kind of active secession movement. The Pilgrims came to North America looking to separate from the Church of England. The Revolution was itself a kind of forced secession from Britain. Entire states, like Kentucky and Maine, split off from existing ones in the country’s early days. The Civil War began soon after Southern states began seceding.

Calls for separation today are often more fragmented. Sections of Northern California and Southern Oregon have proposed a new state of Jefferson. Down state Illinois and upstate New York occasionally float seceding from their state’s population centers. Texas has an old nationalist movement, dating back to its days of independence.

Ryan Griffiths, who studies secession at Syracuse University, says many of these groups are too small even for his database. That makes sense, since state boundaries have been set for decades. Even if many lines – like the near 90-degree angles in the Pacific Northwest – were drawn arbitrarily at first, they feel less fluid today. That makes any move to redraw them a long shot.

“Where they are particularly impractical that’s often a sign that there’s an alternative thing going on,” says Professor Griffiths. “It’s virtue signaling or maybe it’s identity signaling.”

Values and identity are key to many of the movements motivated by America’s growing urban-rural divide. In states like Virginia and Oregon, rural areas have watched from the sidelines as population centers expand and change voting numbers. That process has left many outside the city feeling left behind and a small minority looking for a new home.

Welcome to ... Greater Idaho?

A few years ago, Mike McCarter saw a flyer for a community meeting near his home in rural La Pine, Oregon. He attended, and found a group of Oregonians who shared his frustrations with the state’s direction and wanted an answer. Mr. McCarter stayed involved and later volunteered to become the group’s president. Their solution? Become Idaho.

“Rural Oregon’s values line up much better with Idaho’s values – traditional values of faith, family freedom, independence,” says Mr. McCarter.

He and the Greater Idaho movement propose shifting most of Eastern Oregon to its neighbor. About 10 counties have either voted in support of the idea or are voting on it this year. An Oregon state senator even said he’d consider introducing legislation on it.

That doesn’t mean it will succeed. But Mr. McCarter, a born and raised Oregonian, says people like him need a Plan B. The Willamette Valley, where Portland and Salem stand, has about 70% of the state’s population, and Mr. McCarter doesn’t think there are enough votes to change the state legislature.

GreaterIdaho.org

“We don’t look at it necessarily as a political issue,” he says. “It’s more ... value and cultural differences. There is a dramatic difference between urban and rural and the way people look at things.”

On climate, for example, folks in Portland might think of limiting diesel fuel as a necessary step to reduce carbon emissions. People in the country, though, see that as an affront to their lifestyle, which often requires machinery. Those lenses affect their views of homelessness, drugs, and crime, says Mr. McCarter.

Mr. White, of Atlanta, doesn’t share a rural identity but has similar views on policy. His first priority in a new Buckhead City would be hiring more than three times the current number of Atlanta police officers assigned to the neighborhood – from about 80 to 240 – and raising their pay.

“This is our new home,” says Mr. White. “So when my sister-in-law looks at me and tells me, ‘I’m leaving,’ I said, ‘The hell you are. We’re going to stay and we’re going to stand up for ourselves and we’re going to find a way to fix this.’”

“Leaving seems like giving up”

Most people don’t share the same plan to fix things.

Maurice Hobson, who lives in metro Atlanta and teaches at Georgia State University, sees an underlying message in a new city founded with “tough on crime” policies.

“As a big Black man – a 6-foot-1, 220-pound Black man who looks like I can still play football – I will be nervous to go to Buckhead if they broke away,” says Mr. Hobson, a former University of Alabama football player and author of “The Legend of the Black Mecca,” about Atlanta’s political history.

Buckhead City would be 72% white and 11% Black, leaving Atlanta 27% white and 61% Black, according to the Atlanta Regional Commission. If it left, it would take one-fifth of the city’s population and 40% of its tax base. Annexed in 1952, Buckhead is part of the vibrant, multiracial coalition that makes up Atlanta today.

“A city is about community,” says Carol Beard, a six-year Buckhead resident. “Leaving seems like giving up.”

City of Atlanta

In some ways, it is. Toni Foster, who owns an upholstery shop in Hines, Oregon, the sixth least populated county in the state, says she has given up since Kate Brown won a second term as Oregon’s governor. Ms. Foster volunteers for the Greater Idaho cause, collecting signatures, contacting friends, and helping set up public meetings.

“We pretty much feel forgotten,” says Ms. Foster.

The Portland area already feels like a different state, she says. Ms. Foster and others in her area feel more Idahoan than Oregonian. Why not make it official, she asks?

That could set a concerning precedent, says Mr. Kreitner, author of the book on secession. America’s divisions are hard to map. Even new cities and new states couldn’t separate people who agree and disagree. It might not even help.

“I don’t think that crumbling each of the states into a bunch of pieces is necessarily going to solve our issue,” he says.

Mr. McCarter doesn’t want to crumble all states – just split one. Yet even he, who spends his retirement years driving around rural Oregon asking people to help move the state border, sometimes feels a loss for the state he wants to leave behind.

“This year I’ll be 75 years old,” he says. “I’m born and raised in Oregon. The only time I haven’t lived here is during my military service during Vietnam, and I love Oregon, per se. But I have to balance on the scale of the name Oregon and the pride of being an Oregonian versus freedom, versus the American values.”

GreaterIdaho.org, City of Atlanta

With Russian hackers in mind, NATO takes hard look at cyber strategy

NATO has based its security policy on deterrence, via a mutual defense pact among members. But its strategists are rethinking that approach when it comes to the digital battlefield.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The core concept behind NATO is a simple one: attack one member of the bloc, and all will respond. But while that logic worked during the Cold War, does it make sense to rely exclusively on it in cyberspace?

Western strategists are increasingly saying no. Last year, the alliance quietly announced that a series of lower-level cyberattacks could, cumulatively, be a tripwire for the pact’s mutual self-defense. The move marked a sea change in NATO cyber strategy, and sparked questions about how best to bolster NATO cyber defenses – and if offense, of a sort, might be part of the solution, too.

In crafting NATO’s new cyber strategy, senior security and intelligence officials for the alliance say they were informed by a series of “increasingly destructive” cyberattacks by Russian and Chinese actors over the last few years.

What the incursions had in common was that, though damaging, they fell below the threshold of armed attack. It was increasingly evident, too, that the alliance needed to be more “proactive” in cyberspace, said NATO Assistant Secretary-General David van Weel.

That could mean using “hunt forward” teams of hackers like those the United States has, who defang threats before they have a chance to cause damage.

With Russian hackers in mind, NATO takes hard look at cyber strategy

Article 5 is the linchpin of the NATO pact, putting adversaries on notice that an attack against one is an attack against all. Founded on the Cold War logic of deterrence, the idea is that no aggressor will strike for fear of certain retaliation from combined NATO forces.

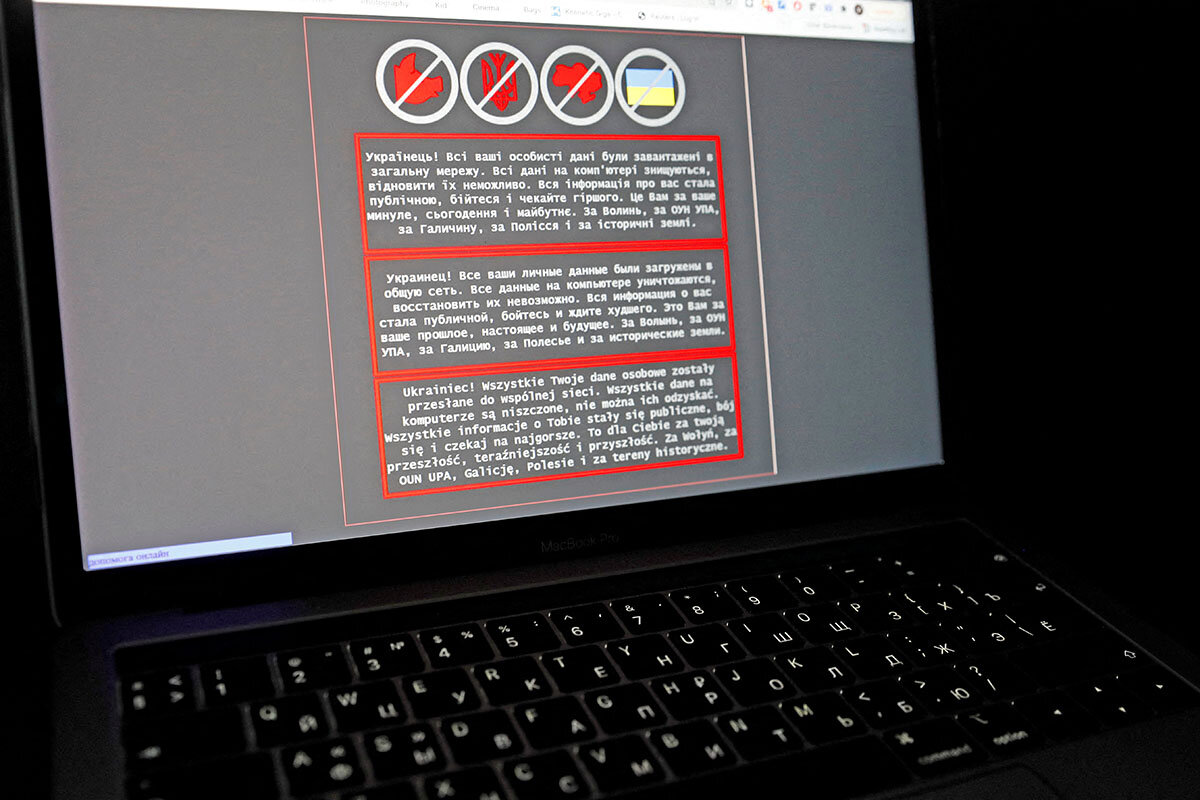

But with modern warfare expanding to virtual battlefields, NATO strategists are overhauling their cyber tactics. That means rethinking the concept of deterrence, as well as what constitutes a cyberattack that triggers Article 5: a crucial issue amid tensions between Russia and NATO-supported (though nonmember) Ukraine.

Since 2019 it has been clear that a large-scale cyberattack on a member could trigger Article 5. But last year, the alliance quietly announced that a series of lower-level cyberattacks could, cumulatively, be a tripwire for the article as well. The move marked a sea change in NATO cyber strategy, and sparked questions about how best to bolster NATO cyber defenses – and if offense, of a sort, might be part of the solution, too.

“It’s a total change in how NATO views Article 5, and it actually could be perceived as escalatory and spiral out of control,” says Stefan Soesanto, senior researcher in the Cyberdefense Project with the Risk and Resilience Team at the Center for Security Studies in Zurich. “No one is really sure whether and when Article 5 will apply.”

NATO officials acknowledge that the opaqueness is part of the point. “Up until now, the idea [among cyber adversaries] was, if we don’t completely disable a full country’s infrastructure, it’ll probably be OK. With the new policy we’re saying, well, that’s not necessarily true,” David van Weel, NATO’s assistant secretary-general for emerging security challenges, said at a discussion with journalists in Brussels in December. “I’m making it less defined. Sorry for that.”

Are enemies deterred?

For the alliance, this ambiguity was a “sorry, not sorry” moment.

That’s because among NATO’s security planners, there has been a growing belief that the military strategy of deterrence – so apt during the Cold War nuclear era – simply hasn’t worked in cyberspace.

“I would feel pretty confident in telling you that there is probably a scale of cyberattack that is deterred: absolute destruction. Clearly attacks like that don’t happen every day. But the scale of cyberespionage and the scale of cyberattacks is growing, and the frequency is very high,” said David Cattler, NATO’s assistant secretary-general for joint intelligence and security, at the December discussion in Brussels. “I’d say on balance, except for probably some really big efforts, [adversaries] are not deterred.”

Reassessing the relevance of deterrence in cyberspace marks a major shift in military strategic thinking, says Richard Harknett, U.S. Cyber Command’s 2016 scholar-in-residence.

A holdover from the Cold War, the idea behind deterrence and escalation, too, is that since there’s no defending against a nuclear attack, the key is convincing an opponent that launching one is too costly in the first place. Until recently, there’s been a belief in cyber that “we’re not threatening enough. We don’t have the punishment right,” Mr. Harknett says. Strategy as it’s currently being pioneered is less about trying to arrest all hacking operations – an unrealistic prospect given the interconnectedness of the internet – as it is to understand and shape them so allies can better protect themselves.

After historically taking “a very defensive approach” to cyber operations, officials are now mulling whether there is “anything from an offensive perspective that this alliance wants to have in its tool kit,” Ambassador Julianne Smith, U.S. permanent representative to NATO, said at a discussion sponsored by the German Marshall Fund of the United States last month in Brussels.

The limits of Article 5

In crafting NATO’s new cyber strategy, senior security and intelligence officials for the alliance say they were informed by a series of “increasingly destructive” cyberattacks by Russian and Chinese actors over the last few years.

When Ukraine was hit by a spate of strikes on its government computer systems in January, as Russian troops massed on its border, NATO officials were watching closely. They had been working “for years,” they noted, to shore up the embattled nation’s cyber defenses, though it’s not a NATO member entitled to Article 5 protections.

What the incursions had in common was that, though damaging, they fell below the threshold of armed attack. It was increasingly evident, too, that the alliance needed to be more “proactive” in cyberspace, Mr. van Weel said. “It’s about not limiting our options to just waiting for a massive attack. It’s about recognizing that what happens below that threshold of a massive attack is worthy of our attention.”

But NATO doesn’t want to be too clear about what the new threshold is, Mr. van Weel added. “The key to the policy is that there is no set bar, and there is a deterrent effect that will go from that.”

Behind the scenes, as cyberattacks were playing out, the U.S. was doing some heavy lobbying for a shift in the alliance’s strategic thinking, says Max Smeets, director of the European Cyber Conflict Research Initiative. This was driven in large part by the Russian meddling in Western elections, and the dawning understanding that a series of cyberattacks can cumulatively tear away at the fabric of democratic society.

In response, U.S. Central Command quietly began deploying proactive expert U.S. military hackers, known as “hunt forward” teams, to operate “outside the United States against our adversaries, before they could do harm to us,” as the group’s head, Gen. Paul Nakasone, explained at the Reagan National Defense Forum in December.

“Hunting forward”

Some military analysts believe that a greater motivation behind NATO’s Article 5 policy shift is to set legal groundwork for allies to work together proactively in a way that is difficult without invoking collective defense mandates under Article 5 – particularly given some NATO members’ reticence about intelligence-sharing.

A potential model for such operations was on display in 2018, when U.S. Cyber Command launched its first known cyber response to Russia for election meddling. In the run-up to the 2018 midterm vote, U.S. military cyber operators “popped up” on the screens of workers at the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Russian state-sponsored troll farm that carried out damaging online influence operations during the U.S. election.

“They just showed up on the system and said hello,” says Mr. Harknett, now a professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati and co-author of the forthcoming, “Cyber Persistence Theory: Redefining National Security in Cyber Space.” They also blocked the IRA’s internet access, a move calculated to put the Russians on the defensive and sow confusion. “They had to be thinking, ‘Americans couldn’t have done all this work just to show up on our screens and say hi. How did they get in?’”

The response among NATO adversaries to such operations remains to be seen, says Mr. Soesanto. “By the Russians, on Russian soil, it could definitely be perceived as escalatory.” At the same time, what U.S. Cyber Command did “was temporarily shut down IRA, but it didn’t stop them.”

Yet the impact of these operations may be less obvious, Mr. Harknett says. “‘Hunting forward’ means you actually have to be in the networks of your adversaries to understand malware development and the vulnerabilities they seek to exploit,” he notes. “A lot of criticism has been made that this is being aggressive, going on the offensive, that it could escalate.” But often, “they don’t even know we were in there.”

Deliberations about the efficacy, politics, and ethics of offensive cyberweapons are likely to be more challenging for the alliance than 20th-century discussions “about tanks rolling across the border, in which case we know how to respond and what to do,” said Ambassador Smith. “And there are still tough conversations to be had.”

The Explainer

Athletes go, Biden stays: Will the Olympics boycott carry weight?

The Olympics offers a unique opportunity for bridge-building among nations. So why are some countries pulling their government delegates from Beijing, and what does it mean for this year’s Games?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The United States’ decision not to send its usual slate of political officials to the Winter Olympics is a bank-shot response to political and human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong. It allows U.S. President Joe Biden to confront the Chinese Communist Party’s behavior, but without a direct, more controversial athlete boycott. About half a dozen other countries – including Australia, Britain, and Canada – have followed suit. Each announced its own diplomatic boycott soon after the U.S.

Questions remain over the impact of this strategy. Due to COVID-19 and the recent omicron variant, the Beijing Olympics is expected to be the most restricted in history. The U.S. delegation already would’ve been small, and the opportunities to see athletes or other diplomats would’ve been limited.

But gestures matter, and a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry warned the U.S. would face “resolute countermeasures,” though it’s not clear what that means.

“For the Chinese, obviously, they’re not happy,” says Lisa Neirotti, a professor of sport management at George Washington University. “They’d rather have no boycott, whether it’s diplomatic or not. But in the end ... it’s not really going to harm their Olympic Games.”

Athletes go, Biden stays: Will the Olympics boycott carry weight?

The United States has trimmed its roster for this year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing. But not of athletes – instead, the U.S. isn’t sending its usual slate of political officials to the Games.

This “diplomatic boycott” of the Beijing Olympics is a bank-shot response to political and human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong. It allows U.S. President Joe Biden to confront the Chinese Communist Party’s behavior, but without a direct, more controversial athlete boycott.

It’s not clear whether that shot will score the administration any points, but about half a dozen other countries – including Australia, Britain, and Canada – have followed suit. Each announced its own diplomatic boycotts soon after the U.S.

What is a diplomatic boycott?

It’s the choice to withdraw government representatives from the Beijing Games.

For the past 20 years or so, the U.S. has sent a small team of political officials to the Olympics. At last year’s Summer Games in Tokyo, first lady Jill Biden attended the opening ceremony, and a separate delegation led by United Nations Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield stayed for the closing ceremony. In between, they watched U.S. athletes compete and met with other diplomats.

“Traditionally the Games are an opportunity, a venue for all kinds of meet, greet, informal discussions, negotiations, mediations, and so on,” says Bruce Kidd, professor emeritus of sport and public policy at the University of Toronto.

The boycott means there won’t be any such hobnobbing in Beijing.

Why is it happening?

In the past four years, China has all but eliminated democratic government in Hong Kong, punished ethnic minorities in Tibet, and reportedly forced more than a million Uyghurs into internment camps in the northwest province of Xinjiang. The Communist Party denies each accusation, but multiple countries, including the U.S., have accused the government of genocide.

Tough-on-China policies are popular in Washington, and an Olympics in the Chinese capital inevitably invited a response from the Biden administration.

“U.S. diplomatic or official representation would treat these Games as business as usual in the face of the PRC’s [the People’s Republic of China’s] egregious human rights abuses and atrocities in Xinjiang,” said White House press secretary Jen Psaki. “And we simply can’t do that.”

Why not a full boycott?

The last time the U.S. tried a full boycott – athletes and all – it was a catastrophe.

In early 1980, the Carter administration wanted a response to the Soviet Union’s recent invasion of Afghanistan. The Summer Olympics were in Moscow that year, and The Washington Post ran an article calling for a boycott by U.S. athletes. Then-President Jimmy Carter liked the idea.

In mid-January, he announced an ultimatum to the Soviets: leave Afghanistan or the U.S. would skip the Games. Mr. Carter soon learned he didn’t have the authority to do that. The U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC), like most others around the world, is private. The U.S. government doesn’t fund it, and can’t control it.

“Essentially, Carter thinks you can just say, ‘We’re going to do a boycott,’ and we’re going to do a boycott,” says Nicholas

Sarantakes, author of “Dropping the Torch: Jimmy Carter, the Olympic Boycott, and the Cold War.” “Turns out he has to do a lot of lobbying.”

The Soviets ignored the ultimatum, and Mr. Carter’s lobbying began. For months, the administration pressured allies and American Olympic officials – threatening to revoke athletes’ passports and asking that sponsors freeze donations. Eventually it strong-armed the USOC into a vote, in which committee members begrudgingly decided to skip the Games.

Many U.S. athletes missed their only chance to compete in the Olympics, and the USOC (now renamed the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee) apologized for the decision 40 years later.

Although the number of competing countries in Moscow was the smallest at any Olympics since 1956, Dr. Sarantakes says the boycott didn’t include many of the U.S.’s most influential allies in the world of sports. Four years later, the USSR and more than a dozen Soviet allies retaliated with a boycott of their own at the Los Angeles Games.

Do diplomatic boycotts matter?

Practically, no. Symbolically, maybe.

Due to COVID-19 and the recent omicron variant, the Beijing Olympics is expected to be the most restricted in history. The U.S. delegation already would’ve been small, and the opportunities to see athletes or other diplomats would’ve been limited.

“I don’t know all of Mr. Biden’s calculations, but maybe he was making a ‘headlines point’ – giving up opportunities for diplomacy when COVID restrictions made them almost impossible,” says Dr. Kidd of the University of Toronto.

Even in a normal year, these delegations don’t do much. The Olympics have encouraged political change before – thawing Soviet-South Korea relations at the 1988 Seoul Games or calling attention to the horrors of apartheid by banning South Africa’s Olympic committee. But for the most part the diplomatic teams aren’t responsible for those. Most of the time, says Dr. Sarantakes, their job is just to support the athletes.

But gestures matter, and a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry warned the U.S. would face “resolute countermeasures.” It’s not clear what that means, and it may have been posturing to keep other countries from initiating their own boycotts, says Lisa Neirotti, a professor of sport management at George Washington University.

“For the Chinese, obviously, they’re not happy,” she says. “They’d rather have no boycott, whether it’s diplomatic or not. But in the end ... it’s not really going to harm their Olympic Games.”

How will this affect political speech at the Games?

It adds pressure.

Ahead of last year’s Summer Games, the International Olympic Committee revised its Rule 50, which bans political speech during competition or on the podium. Athletes responded with demonstrations, some of which broke even the more relaxed, updated rules. For the most part, the IOC looked the other way.

But Beijing isn’t Tokyo. The Chinese government is more sensitive to political demonstrations, and the diplomatic boycotts may add scrutiny to athletes’ behavior.

“I’m hoping the IOC will have already persuaded or will persuade the Chinese to just simply shrug or take a deep breath and let things go on as happened in Tokyo,” says Dr. Kidd. But that’s hardly a guarantee, he says. If an athlete offends the Chinese government – say protesting the Uyghur internment on the podium – then no one knows what will happen.

“I think everybody’s going to be watching,” says Dr. Kidd.

Cuban kids don’t care about grandpa’s revolution – they want jobs

Cuba’s young people are no longer moved by their government’s revolutionary rhetoric. Harsh punishment of peaceful demonstrators is likely to backfire.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Rudy Cabrera Arcia Correspondent

Taken by surprise last July by a spate of protests against its economic policy, the Cuban government has cracked down hard. More than 1,300 people have been arrested – many of them young people – and the courts have recently handed down sentences for peaceful demonstrators as heavy as 30 years’ jail time on charges of sedition.

But the communist government’s familiar rhetoric about safeguarding the revolution carries little weight today with youths born more than 40 years after that revolution. They feel little emotional attachment to it, and look to the authorities to provide jobs, tame inflation, and broaden civil liberties.

That last demand seems destined for disappointment, to judge by President Miguel Díaz-Canel’s heavy-handed crackdown on last year’s protesters. The trials, however, and the draconian punishments that judges are meting out, are unlikely to cow the new generation.

Rather, says Manuel de la Cruz Pascual, a young writer in Havana, “the conditions have been created for another protest in the same vein as July” to break out in the future.

Cuban kids don’t care about grandpa’s revolution – they want jobs

Bárbara Farrat Guillén was hosting what she had expected to be an uneventful family gathering for her son Jonathan’s birthday last summer. But the young man happened to turn 17 on July 11, the day that historic protests erupted unexpectedly across Cuba – and the family is still dealing with the aftershocks.

The teen stepped out to look for his father, who had been surprised by the demonstrations on his way home. Six months later, Jonathan is still languishing in detention, suffering beatings, his mother says, and charged with inciting public disorder and attacking the authorities.

Scores of others have already been tried, and sentenced to as much as 30 years in jail on charges of sedition, for protesting peacefully against the government’s economic failings.

The harsh punishments meted out by the courts have crushed any hope that President Miguel Díaz-Canel – Cuba’s first non-Castro leader since the revolution – might usher in greater civil liberties. They also risk backfiring, suggests Manuel de la Cruz Pascual, a young writer and independent journalist in Havana.

“What Díaz-Canel is doing with his policies of repression and these mass trials of protesters is generating and empowering more dissidents,” he says.

Sebastian Arcos, associate director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University in Miami, agrees that in the long term the trials are unlikely to intimidate the young Cubans at the forefront of last July’s demonstrations.

“They want people to be very afraid ... but it’s a different world” from Fidel Castro’s Cuba, says Mr. Arcos, a former Cuban political prisoner. “There’s a chance they’re too late.”

Young people’s greater access to the internet, fewer personal ties to Mr. Castro’s revolution, and the sense that they have very little to lose are shifting the way they look at their government. July 11, suggests Mr. de la Cruz, marked a “big awakening.”

Revolution’s fading appeal

The countrywide July 11 protests, broadcast on social media, attracted many young people who blasted the streets with reggaeton beats.

They were motivated partly by economic grievances; inflation hit 70% last year, according to government figures, and the average monthly wage is the equivalent of $163. But protesters were also openly “demanding freedom and the resignation of the government,” recalls Mr. Arcos. “That’s a total breakdown of the regime’s rules.”

That may explain the government’s heavy-handed reaction, which has drawn criticism from the European Union, the United States, and international human rights organizations. Over 1,350 people are in jail or under house arrest for their roles in the July 11 protests, according to Laritza Diversent, director of Cubalex, a U.S.-based legal aid group tracking the detentions.

Some families have been assigned lawyers by the government, but Yudinela Caridad Castro Perez, whose son Rowland is facing a 23-year prison sentence for having joined the protests, does not expect much of his attorney. “It’s decorative, an attempt to legitimize these trials when the government is judge and jury,” she scoffs.

Economic uncertainty drew many of the demonstrators, believes Ms. Diversent. “You can’t plan your life. Not teens, not their parents, not their grandparents can navigate a path toward a dignified life. The economic conditions are horrendous,” she says.

And that mood won’t change, she predicts, “if there is no change in policies. The majority of protesters come from poverty. This won’t be resolved by ideology.”

Not that the government’s communist ideology has much appeal to young Cubans anymore, 60 years after Mr. Castro’s guerrillas overthrew a military dictatorship.

The revolution “is something that happened so long ago, and it’s a word that’s just completely overused in Cuba,” says Emily Telly, who is in her early 30s, unemployed, and living in Havana. “I don’t feel any connection to the revolution; it doesn’t make any sense anymore, especially to us” younger people.

“All of these measures are done to intimidate us,” she says of the trials, “but they are going too far. The government isn’t even following the constitution. But Cubans today, we don’t have much to lose.”

“All we want is change”

The government crackdown has sown seeds of dissent across older generations, too.

“It’s difficult for a mother to see her son behind bars for something that in any other country in the world – a peaceful protest – is considered normal,” says Teresa Rodríguez Simón, three of whose children were detained in the days following last summer’s protest, accused of ties to foreign powers.

“All we’re asking of the comandante [President Díaz-Canel] is to analyze this situation, reflect on what happened and why,” she says. “Look at what pushed so many people and so many youth to protest.”

Jonathan’s mother, meanwhile, has become a political activist for the first time in her life, marching in public with other “Ladies in White” – an opposition movement founded by female relatives of jailed and “disappeared” dissidents.

“There are mothers like me who aren’t keeping quiet, who won’t let it drop that our children are in prison,” she says. Though afraid for her son, “the fear I have right now is not so much a fear of the government because they always do the same thing,” she explains. “I won’t let that scare me anymore.

“We no longer want the revolution they’re selling us,” she says. “All we want is change.”

For Mr. de la Cruz, the writer, Mr. Díaz-Canel’s invocation of revolutionary values is a smokescreen. “The president’s actions against the protesters have nothing to do with this utopian revolution, with the values of conserving the revolution, not only as an idea but as a social project,” he argues. “He’s simply hiding behind these trials trying to hold onto power.”

And the president can expect more challenges in the future, Mr. de la Cruz expects.

“The political and economic conditions on the island have not changed,” he says, “and with more government surveillance and no way to escape, the conditions have been created for another protest in the same vein as July.”

Storefront history: Amman museum celebrates lost art of signage

When computer designs replace handmade art, what is lost? In Jordan, a museum of old-time signs celebrates the artistry in which “each brushstroke is a line from our past to the present.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Jordanians once were completely reliant on calligraphers. Opening a grocery store? Decaling a truck? Writing a royal letter? From the farmer to the king, Jordanians turned to professional calligraphers, who drew from an armory of Arabic scripts.

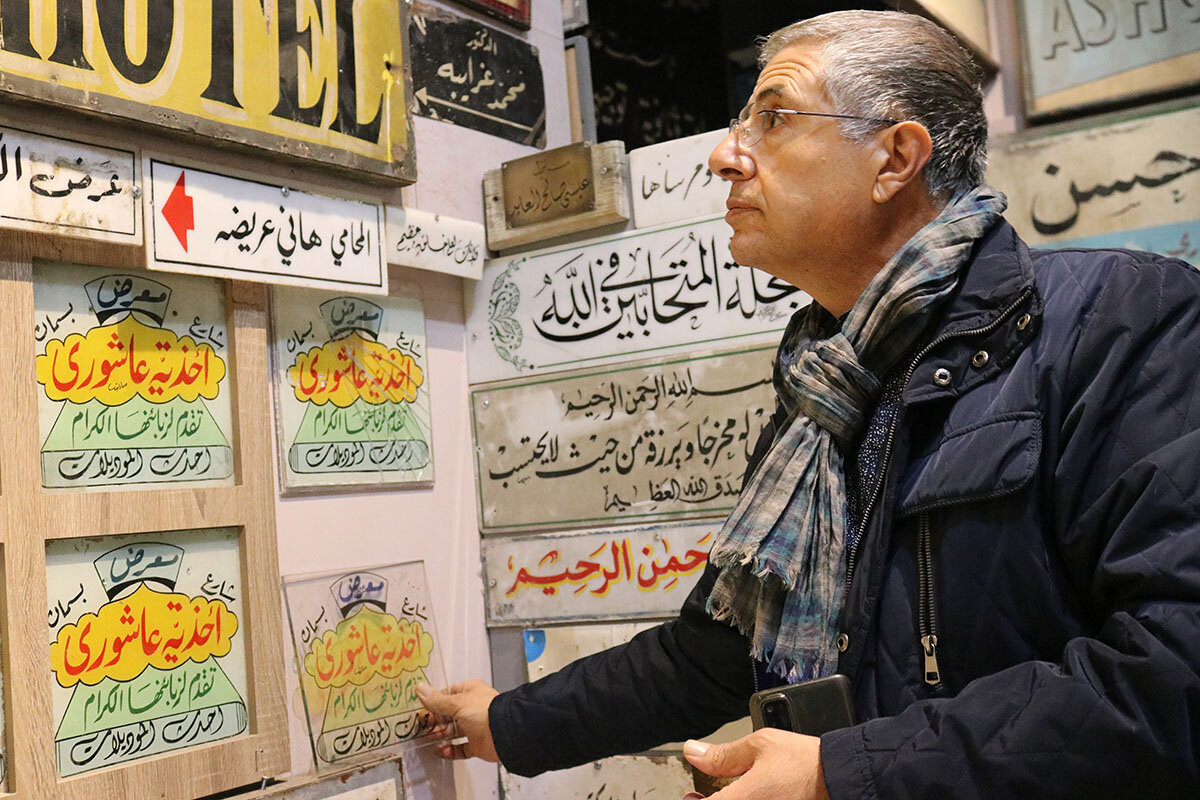

Amman’s cityscape was once filled with colorful signage, sources of pride to the calligraphers, who sought to outdo one another with their art. Showcasing their work today is The Old Signs of Amman Museum, which tells hundreds of stories about the capital and its shops, residents, and society as far back as the 1940s.

It is the brainchild of Ghazi Khattab, who as a child ogled the city’s hodgepodge of signs, the Arabic names twisting, curving, and ballooning in a mix between a sultan’s palace fresco and pop art. They inspired him to study graphic art, open a modern sign press in Amman, and collect the vintage signs he now displays.

“By introducing modern methods, I was benefiting business owners, because our work was fast, clean, and efficient, but I was hurting the art,” Mr. Khattab says sheepishly. “This is my way of giving back.

“I originally established the museum to preserve these signs as examples of Arabic calligraphy,” he says, “but it turns out these signs mean much more; they are people’s memories.”

Storefront history: Amman museum celebrates lost art of signage

From the flip of the calligrapher’s brushstroke to the choice of Arabic script applied to sheets of metal and glass, the works are more than advertisements; they are signs of the times.

The Old Signs of Amman Museum that showcases these works tells hundreds of stories about the Jordanian capital and its shops, residents, and society as far back as the 1940s.

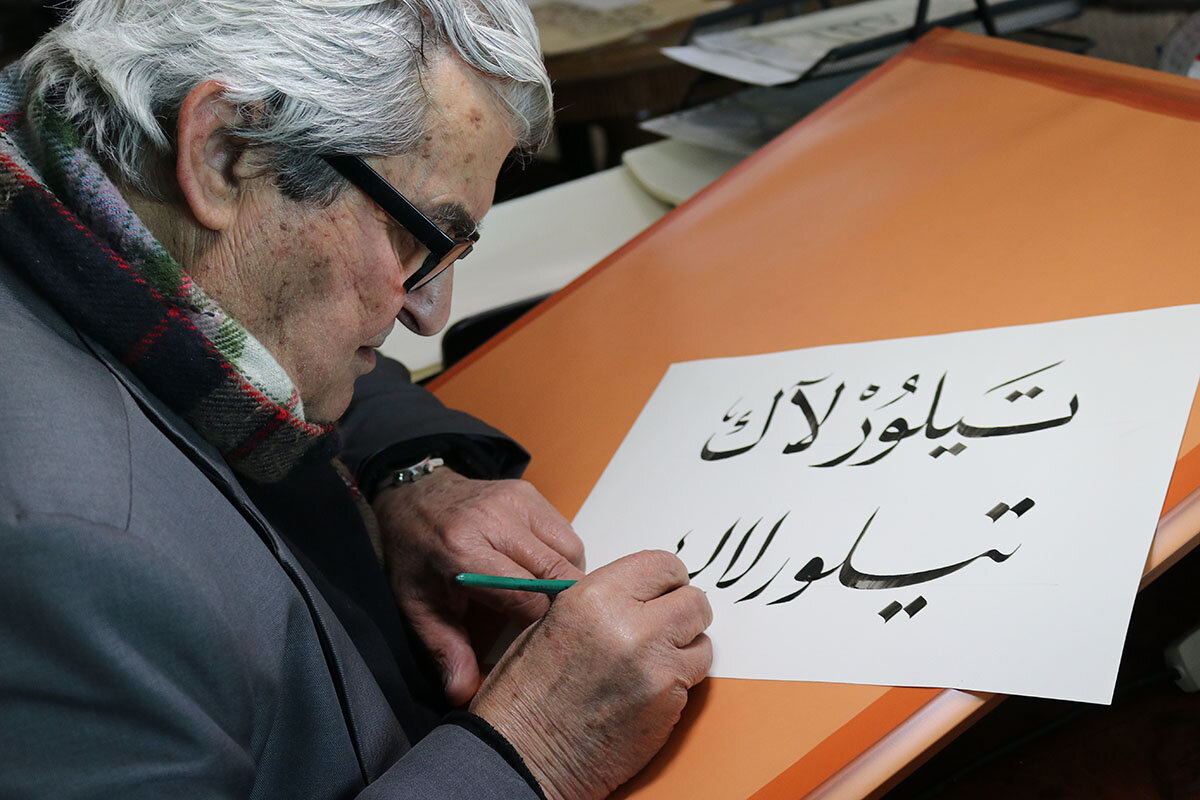

But perhaps the hand-painted signs’ most captivating story is that of the skill of the khattat, or professional calligrapher, who painted them.

Once upon a time, Jordanians were completely reliant on calligraphers.

Opening a grocery store? Decaling a truck? Wedding invitations? A royal letter? From the farmer to the king, Jordanians turned to a khattat.

The calligraphers drew from an armory of Arabic scripts, each taking years to master, such as the bold and simple Thuluth, the dainty and curvy Farsi, the blocky and thick Kufi scripts.

They would spend hours choosing the best font to fit the words and subject matter.

“You have to write in a way that is beautiful, readable, and suitable for the word and how the letters look together on a sign,” says Riad Tabbal, one of the last remaining khattats, who painted Amman’s cityscape with colorful Arabic calligraphy that Jordanians once relied on as landmarks.

Windows to the past

The unusual, free Old Signs of Amman Museum is the brainchild of Ghazi Khattab, a graphic designer whose love of Arabic calligraphy began when he was a child walking in downtown Amman in the 1970s.

He would ogle the colorful hodgepodge of signs that then dotted every building, the Arabic names twisting, curving, and ballooning in a mix between a sultan’s palace fresco and pop art.

The signs later inspired Mr. Khattab to study graphic art in Germany, open a modern sign press in Amman, and collect the vintage signs he now displays.

While vintage signs in the West were often produced in runs of 300 or more, Amman signs were custom-designed and painted by hand; like ink-blotted snowflakes, no two signs were alike.

“Each sign is a one-of-a-kind; you can see where the brushstroke started and stopped, where the brush was active, where it slowed, and where the understudy stepped in to finish the job,” Mr. Khattab tells visitors one Tuesday morning as he traces his first vintage sign with Sarsour, family name of the owners of a famous Amman garment shop, written in futuristic, blocky red-and-black letters.

The signs are also historical records, freeze frames of a lost Jordan.

They feature words that have disappeared from the Jordanian lexicon, including: nouveaut to mean new clothes, mobiliat for furniture, and couponat, unique sets of cloth sold by textile stores to customers wanting a bespoke suit no one could copy.

Other signs read “doctor is present,” from a time when receptionists were scarce.

One bold grocery shop billed itself as “The King’s Store,” advertising its royal certification by King Abdullah I as “By appointment to His Hashemite Majesty THE KING.”

Others were painted by Palestinian calligraphers from Jerusalem, carried by store owners when they were pushed into Jordan following the 1948 and 1967 wars with Israel, and eventually hung on their new shops, and new beginnings, in Amman.

A lost art

Months shy of his 80th birthday, Mr. Tabbal boasts a career including writing Royal Court letters and designing the logo for Royal Jordanian, the kingdom’s flagship airlines, which still adorns aircraft today.

His process for producing signs takes 10 to 15 days, starting with a coat of primer on a metal sheet, then a second coat of synthetic paint before painting the text, drying it again, and encasing the sign in a protective sheet of glass.

The most important step for Mr. Tabbal and his fellow calligraphers? The design.

Doctors’ and lawyers’ offices were given a simple, no-nonsense black-on-white Naskh script; a mosque would get a delicate, curvy Farsi script. A cafe or carbonated beverage? Calligraphers would splurge with curves, loops, and bubble lettering with extra shading to give the Arabic words an added 3D pop.

The finishing touch was the signature, a specially designed logo to tell the world – and rival calligraphers – this was their work.

Jordan’s self-taught calligraphers engaged each other in contests to see “who could write the most beautifully,” Mr. Tabbal says, spending extra hours and days to make the most intricate, complex, detailed Arabic script to one-up rivals – at no extra charge to the customer.

But with the rise of digitally printed calligraphy in the late 1990s, khattats lost 80% of their work, unable to compete with the machines that produced in hours what took them 10 days by hand.

Lost business is one thing; lost art is another.

“There is no spirit or originality in the text; it has taken an art form and turned it into something utilitarian and disgusting,” Mr. Tabbal says as he holds up an envelope with printed calligraphy, frowning, “and quite frankly, it just doesn’t look good.”

A way to give back

In the 1990s, as Jordanians and businesses traded in the colorful handmade artworks for cheaper, faster electronically produced calligraphy – like those Mr. Khattab himself printed – the graphic designer stepped in to rescue the retired works.

“By introducing modern methods, I was benefiting business owners, because our work was fast, clean, and efficient, but I was hurting the art,” Mr. Khattab says sheepishly. “It feels like I was betraying the Arabic language. This is my way of giving back.”

Mr. Khattab offered to take the vintage artwork from companies and factories that were upgrading in exchange for new signs free of charge, and intervened at businesses that were shuttering to prevent the masterpieces from ending up on the garbage heap.

Today, he restores vintage signs that the Amman municipality painted over in a uniform beige in 2006, and carefully glues together shattered signs.

Since Mr. Khattab opened the free museum in downtown Amman in December 2019, it has seen 6,000 visitors a month, sparking surprisingly personal connections.

Jordanians have discovered the sign of the school their father taught at, or that hung above their grandparents’ clinic.

A pair of older visitors huddle by the now-defunct Haifa Hotel sign, reminiscing about their youth. Others read their deceased father’s name emblazoned in ink on glass and, for a moment, sees him in their mind’s eye.

“I originally established the museum to preserve these signs as examples of Arabic calligraphy, but it turns out these signs mean much more; they are people’s memories, economy, politics, personal histories, and connections to loved ones,” Mr. Khattab says.

Says Mr. Tabbal, the calligrapher: “Each brushstroke is a line from our past to the present.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A day of silence sends a loud message in Myanmar

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Most cities in Myanmar were very quiet on Feb. 1. Shops were closed and millions of people stayed home. The day was billed as a “silent strike” to mark the first anniversary of a coup that ended a nascent democracy in the Southeast Asian nation. By silencing commercial activity – at least for a day – the strike served as a loud reminder for people in Myanmar to exercise their freedom from fear. It also enabled them to live the truth about the real source of power in shaping civic life.

“Law and order are still in the hands of the people,” said Thura Aung, a Mandalay-based organizer.

The strike also exposed the desperation of the military brass to stop a nonviolent action designed to show the emptiness of their lies about a legitimacy to rule. Dozens of shop owners were arrested before the strike.

Since 2010, when the military introduced some political freedoms in hopes of staying in power, young people have come to enjoy rights and liberties. They still want to practice those democratic values. On Feb. 1, they showed themselves, the military, and the world that they could.

A day of silence sends a loud message in Myanmar

Most cities in Myanmar were very quiet on Feb. 1. Shops were closed and millions of people stayed home. The day was billed as a “silent strike” to mark the first anniversary of a coup that ended a nascent democracy in the Southeast Asian nation. Over the past year, street protests have not ended the military’s violent rule. Nor has a small, civilian-led armed rebellion. By silencing commercial activity – at least for a day – the strike instead served as a loud reminder for people in Myanmar to exercise their freedom from fear. It also enabled them to live the truth about the real source of power in shaping civic life.

“It has been a year. The military council has not gained the control of the country,” Thura Aung, a Mandalay-based organizer, told Radio Free Asia. “The power is still in the hands of the people. Law and order are still in the hands of the people.”

The strike also exposed the desperation of the military brass to stop a nonviolent action designed to show the emptiness of their lies about a legitimacy to rule. Dozens of shop owners were arrested before the strike. Many more were threatened with imprisonment and confiscation of their businesses.

In addition, the ruling junta may have wanted to stem a reported decline in morale among the rank and file. In its brief silencing of public life, the strike sent a signal to foot soldiers that the people prefer rule by moral authority over physical force. When it ended at about 4 p.m., many videos were posted on Facebook showing people clapping at its success in attracting widespread – and peaceful – support.

Last year’s coup was a response to the tremendous loss of the military’s proxy political party in elections held in November 2020. The military, controlled by Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, ousted the clear winner of that election, Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party. The NLD’s popularity had grown since a democracy movement began against the country’s military rulers in 1988. Since the coup, many of the party’s leaders have either fled or, in the case of Aung San Suu Kyi, been imprisoned.

Since 2010, when the military introduced some political freedoms in hopes of staying in power, young people have come to enjoy rights and liberties. “The youth know what freedom, equality and respect are,” Zun Moe Thet Hlaing, a 24-year-old protester, told Nikkei Asia. Despite the military’s violent crackdown on dissent – more than 1,500 civilians have been killed in the past year – young people still want to practice those democratic values. On Feb. 1, they showed themselves, the military, and the world that they could.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Be the better man’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Tish

Choosing a better response than reacting or retaliation is acting in accord with our true nature as the children of an all-loving God.

‘Be the better man’

My friend Liz taught me a lot about parenting, and she always had a quick one-liner to explain a life lesson to her children.

One day when the kids and I were over for a play date, her son was aggrieved because a friend of his was behaving badly and had been mean to him. Her son wanted to retaliate with a similar unkindness, but Liz looked him square in the eye and said, “Be the better man.” She then left him to go think about what that meant, and I thought about it too.

She didn’t mean to say that her son was better than this other person, or that he should think or act as if he was better than someone else. But she meant that if you want someone to be better, then you should start by being better yourself! We will never find satisfaction by lowering our standard of behavior. On the other hand, behaving according to our highest sense of right, we not only feel better, but it is likely our good words or deeds will bless others as well.

Christ Jesus definitely showed what it means to “be the better man” in the face of hatred and persecution. The Gospels record instance after instance of Jesus remaining poised and gracious in his interactions with those who strongly opposed him and his ministry. His commitment to good words and deeds effectively rejected the hatred aimed at him and led to his own triumph over all evil, blessing all of humanity.

Christian Science explains that undergirding Jesus’ thoughts and actions was the deep-seated understanding that God is all-powerful and only good, and that each individual is made to spiritually express this divine nature – to be a shining example of God’s goodness and love. So when confronted with what seemed to be evil in others, Jesus never resigned himself to that sense of them. Seeing the pure spirituality and goodness that he knew constituted the real identity of each individual, Jesus unfailingly rose above the evidence presenting evil as real, understanding it as the falsity not the fact of existence.

Jesus’ example was given to lift all of humanity to this better model for thought and action. In the book of John he is recorded as saying, “Now shall the prince of this world be cast out. And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me” (12:31, 32). “The prince of this world” might be considered the pervasive belief that man can be evil, constituted of ungodlike qualities. In particular, Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of the Monitor, wrote, “The pride of place or power is the prince of this world that hath nothing in Christ” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 4).

Years ago, I was serving in a key role in our church, and there was another church member who appeared to strongly dislike me and my style of working. He was very critical of many things I did, and at one point even threatened to have me removed from the position I was serving in.

Roiling inside, I couldn’t stop ruminating about what he had said to me and what I might say back to him! Distressed at the way my thinking was headed, I began to pray about it. I knew I could be “lifted up” to a Christlike response in thought and deed.

Soon, I remembered a simple phrase written by Mrs. Eddy: “And Love is reflected in love” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 17). This is Mrs. Eddy’s spiritual interpretation of Jesus’ words in the Lord’s Prayer, “And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors” (Matthew 6:12). Or in other words, when we forgive others, reflecting that all-encompassing divine Love, love is expressed right back at us!

As I considered this idea, I was suddenly struck by how much this person and his family contributed to the operation of our church. He was so selfless in his devotion to our church, and his sincere love for Christian Science was evident. I spent some time just thinking about all the things he had ever done for church, and feeling grateful for each one. Slowly the anger faded away and it was replaced by a genuine love for this man. And I thought, “It’s OK if he doesn’t like me. I just love him!”

Well, Love was indeed reflected in love. Soon, he was treating me so much more kindly. A few weeks later he came up to me after church and apologized profusely for having been so unkind. In fact, he shared how much he appreciated the work I was doing and couldn’t imagine what caused him to say what he said.

So often we hope that someone else will behave better, do something better, or apologize for some offense they have committed. But we are each responsible only for our own behavior, for our own thoughts and deeds. What we are thinking, along with how we respond, makes all the difference. When we choose something better than negativity, hatred, or reacting in kind, we’re choosing our better nature – our only real nature – as God’s loving and kind and good creation.

A message of love

Honoring a comrade

A look ahead

That’s a wrap for today. Join us tomorrow when we look at how the pandemic is impacting schools – and prompting home schooling across racial and ethnic groups.