- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- No more charm offensive: How China’s Olympics goals have shifted

- Seeking to counter China on chips, Congress gets stuck fighting itself

- The Russian public doesn’t want war, but is anyone listening?

- Black History Month: These writers’ messages still ring true

- What can a string ensemble do? Harmonize community, calm baby.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Kindness shines in ‘Come From Away’ actor’s onstage graduation

Emily Walton acts in a Broadway musical about positive things arising out of dark moments. The production is “Come From Away,” which tells the true story of how Gander, Newfoundland, rose to the moment when 38 airliners diverted there after the United States closed its airspace following the Sept. 11 attacks.

In real life, Gander opened its arms to 6,500 visitors. People welcomed strangers into their homes, gave them books and blankets, lent them cars, laughed and prayed with them, and baked lots of tea cakes. It was kindness that had a permanent effect on recipients and givers, as the Monitor’s Sara Miller Llana reported last year.

Ms. Walton plays “Janice,” a TV journalist, in “Come From Away.” But in March 2020, she – and everyone else on Broadway – faced unemployment as theaters closed due to the pandemic.

Ms. Walton decided to try to get something good out of the bad time, just as characters did in her show. She finished her college degree online at Southern New Hampshire University, 13 years after dropping out to follow her acting dream.

Broadway lights are back on now. On Jan. 21, the president of SNHU surprised Ms. Walton onstage at the end of the show with a cap, gown, and diploma. She cried as she realized she was finally graduating.

“It’s actually made me a better person to be part of this show because ... [it] makes you realize that being kind is so easy and celebrating each other’s accomplishments and joys is so rewarding, and I just kind of think it’s what life is about,” she said afterward.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

No more charm offensive: How China’s Olympics goals have shifted

China used the 2008 Olympics to reintroduce itself to the world, but this year’s Games are all about the domestic audience. Comparing the events offers insight into how Beijing’s goals and priorities have changed.

Fourteen years ago, China proudly showcased its sports talent and ancient civilization before a global audience at the Summer Olympics. An opening extravaganza celebrated Chinese inventions from gunpowder to printing, while thousands of synchronized drummers chanted a Confucian saying about the delights of “friends coming from afar.”

The 2008 Games were part of a broader diplomatic charm offensive by Beijing – one that included economic reforms and a softening of China’s stance on thorny issues from territorial disputes to human rights, says Peter Martin, author of “China’s Civilian Army,” a book about China’s growing power and diplomatic assertiveness. It was aimed at making Beijing’s Communist Party leadership “more palatable to the outside world,” he says.

But such exuberant outreach to the world has largely been missing during the lead-up to the 2022 Games. Under China’s zero-tolerance pandemic policy, experts say the Olympics will unfold in a tightly closed loop, as China’s leaders focus mainly on how the Games are viewed domestically.

“In terms of the image that China seeks to project, the main priority ... is the domestic audience, and showing people back in China that China is a respected country, that it’s seen as a leader,” says Mr. Martin.

No more charm offensive: How China’s Olympics goals have shifted

Fourteen years ago, China staged the 2008 Summer Olympics, proudly showcasing its sports talent and ancient civilization before a global audience eagerly courted by Beijing.

An opening extravaganza celebrated Chinese inventions from gunpowder to printing, while thousands of synchronized drummers chanted a Confucian saying about the delights of “friends coming from afar.”

“I can still remember the enthusiasm of Chinese at the time,” says Mu Yue, who navigated huge crowds of Chinese and foreigners as a photo assistant at the Games. Wild cheering and the glitter of flashing cameras filled stadiums, she recalls, along with endless renditions of the song “Beijing Welcomes You.”

But such exuberant outreach to the world has largely been missing during the lead-up to the 2022 Games. Under China’s zero-tolerance pandemic policy, experts say the Olympics will unfold in a tightly closed loop, as China’s leaders focus mainly on how the Games are viewed domestically.

“In terms of the image that China seeks to project, the main priority ... is the domestic audience, and showing people back in China that China is a respected country, that it’s seen as a leader,” says Peter Martin, author of “China’s Civilian Army,” a book about China’s growing power and diplomatic assertiveness.

Shift in strategy

In 2008, the Olympics were part of a broader diplomatic charm offensive by Beijing – one that included economic reforms and a softening of China’s stance on thorny issues from territorial disputes to human rights, says Mr. Martin. It was aimed at making Beijing’s Communist Party leadership “more palatable to the outside world,” he says.

Today, Beijing’s leaders project more confidence in China’s power and position, and feel they have less to prove to the world, analysts say. China’s gross domestic product has tripled since 2008, as the country rose to become the world’s top exporter and the second-largest economy.

In the past decade, China has adopted a more assertive foreign policy, pushed for territorial gains, and conducted a sometimes abrasive “wolf warrior” diplomacy – all factors that have hurt its image in the West, Japan, and other advanced economies. Beijing recently threatened countermeasures against countries that have imposed diplomatic boycotts of the Games to protest human rights violations in China. It has also warned that athletes will face punishment for speech that violates the “Olympic spirit.”

“In the first Olympic Games, Beijing tried to please the whole world, but now I think they really don’t care about world opinion,” says Xu Guoqi, a history professor at the University of Hong Kong and author of “Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008.”

Instead, China’s leaders increasingly present China as a model for other countries to emulate, citing, for example, successful pandemic control measures and smooth Olympic preparations as evidence of the effectiveness of Communist Party rule.

To be sure, hosting China’s first Winter Olympics, on schedule, during a global pandemic, is a massive undertaking and major accomplishment. “If China can deliver the Games ... on time, that’s a big success for everyone – for the host, for IOC [the International Olympic Committee], and especially for [Chinese leader] Xi Jinping,” says Dr. Xu.

Beijing’s message is clear: “This is a challenge implicitly that no other country could do, and therefore it shows the direction that Xi Jinping and his colleagues are setting is the best one for China,” says David Bachman, Henry M. Jackson professor of international studies at the University of Washington.

Mr. Xi has put his stamp on the Games – overseeing China’s winning 2015 bid to host the event, inspecting ski slopes and ice arenas, and announcing the opening of the Games on Friday. “These are Xi Jinping’s Games,” and will form part of his legacy as he prepares this year to gain a third term as China’s top leader, says Dr. Xu.

Focused on domestic opinion, Mr. Xi has cast the Games as boosting public faith in what he calls China’s inevitable progress toward a “great rejuvenation.” The administration’s goals include eradicating extreme poverty, which Mr. Xi declared accomplished in 2020, and transforming China into a fully developed nation by the country’s centennial in 2049.

“The successful hosting of Beijing 2022 will ... enhance our confidence in realizing the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” Mr. Xi said last month, according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

Audience apathy

Yet despite the Chinese leadership’s hopes that the Games will resonate at home, China’s public is showing little interest, citizens and experts say. “I have rarely seen any reports on social media about the Winter Olympics,” says Ms. Mu, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to protect her identity.

“The Olympic Games seem to not catch our eyes,” says Brandon Zhang, a graduate student from southern China who recently arrived in Seattle to begin a doctoral degree. Although he is an avid skier – a sport he picked up while studying in Beijing – Mr. Zhang won’t tune in to the Winter Games. “We would rather hang out with family members than watch the boring Games,” he says.

Winter sports such as skiing are not extremely popular in China, in part because of the landscape. “Snow is not a common thing for us, and skiing is kind of a luxurious activity for common people,” says Mr. Zhang, adding that many Chinese parents consider the sport dangerous.

In contrast, most Chinese people have opportunities to play pingpong or basketball or to run, he says, so they enjoy the Summer Games more.

Indeed, for many Chinese such as Ms. Mu and Mr. Zhang, there is no comparison between the subdued atmosphere surrounding the Winter Games and the heady optimism, euphoria, and cosmopolitan spirit that dominated the 2008 Olympics.

“It’s emotional” to reflect on those August days, even now, Mr. Zhang says. Then a high school student, he couldn’t afford tickets to attend any Olympic events, but he and his family watched them on television at home in Guangzhou for as many as 10 hours a day. The 2008 Olympics “are one of the most important events in China,” he says. “It’s a beautiful memory of my childhood.”

China captured 48 gold medals in the 2008 Summer Games, more than any other country. At the last Winter Olympics in South Korea, China won one gold medal.

“Now you can see, nobody gets excited at all; nobody even bothers to pay attention,” says Dr. Xu. “They know basically nothing extraordinary will come out of this Games compared to what happened 14 years ago.”

Seeking to counter China on chips, Congress gets stuck fighting itself

U.S. lawmakers are increasingly united in seeing China as a strategic adversary, and in wanting to revive homegrown chip manufacturing. Yet a trademark of the current Congress – partisan maneuvering – may play into Beijing’s hands.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

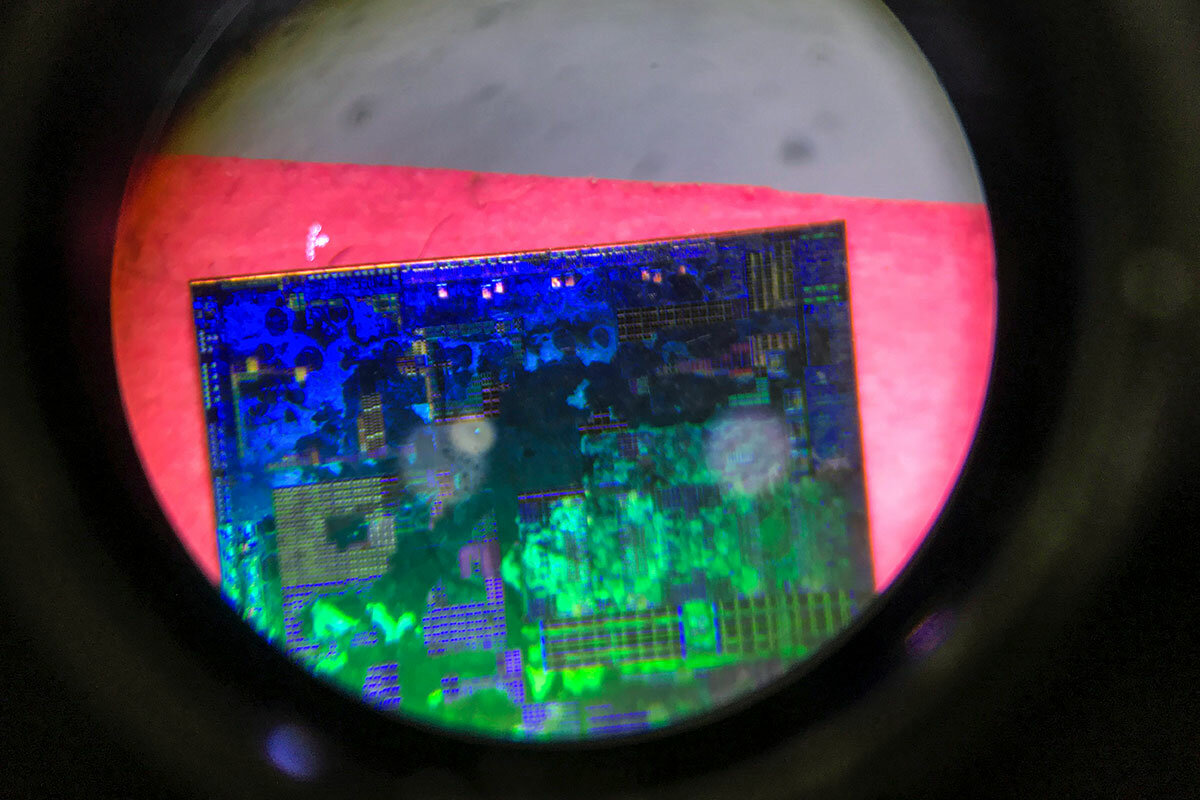

Everything Americans use with an on-off button, from dishwashers to iPhones to Teslas, likely includes a key component: computer chips.

The problem is, America’s supply is running short. The scarcity, fueled by pandemic-related supply disruptions, has driven up prices on items from cars to appliances. Inflation has become a top voter concern.

Lawmakers in Congress have a proposal for investments that would bring more chip manufacturing back to America. It’s called the CHIPS Act, and it passed the Senate 68-32 in June as part of a larger bill to increase U.S. competitiveness vis-à-vis China.

Today, the House passed its version of the legislation, the America Competes Act. But unlike with the Senate bill, Democrats were unable to win more than one vote from Republicans, who said they were caught off guard by the nearly 3,000-page bill, which includes an array of progressive priorities in addition to CHIPS.

Democratic Rep. Elissa Slotkin of Michigan is among those lamenting the half-year delay and the looming challenge of striking a compromise that can win bipartisan Senate support.

“Passing a bill just through the House will do nothing to get microchips to the auto plants I represent,” she said in a statement.

Seeking to counter China on chips, Congress gets stuck fighting itself

Everything Americans use with an on-off button, from dishwashers to iPhones to Teslas, likely includes a key component: computer chips.

And the problem is, America’s supply is running short. The scarcity, fueled by pandemic-related supply disruptions, has driven up prices and spurred inflation. As new cars became more expensive to make, for example, used-car prices spiked nearly 40% in the first year and a half of the pandemic.

Such economic troubles are at the top of voters’ concerns, according to polls. And the fact that the most sophisticated chips, including those needed for military equipment, are mainly made in Asia raises national security concerns.

Lawmakers in Congress have a proposal to address the problem by investing in facilities that would bring more chip manufacturing back to America. It’s called the CHIPS Act, and it passed the Senate with strong bipartisan support in June as part of a larger bill to increase U.S. competitiveness vis-à-vis China.

The irony is that in trying to increase America’s competitive edge, Congress has gotten stuck in partisan wrangling that plays right into Beijing’s hands.

Today, the House passed its version of the legislation 222-210. But apart from one GOP vote, Democrats were unable to win support from Republicans, who said they were caught off guard by the nearly 3,000-page bill, which includes an array of progressive priorities in addition to bipartisan measures like CHIPS.

Beijing “would love nothing more than to see us in a partisan battle over China,” says Rep. Michael McCaul of Texas, a leading GOP voice on the CHIPS Act. “What they would hate to see is if we came together and passed the CHIPS for America Act.”

Now the House and Senate will have to seek a compromise version that both chambers can support – all while companies and consumers continue to face the consequences of a chip shortage. Lawmakers who worked on the original CHIPS legislation are already frustrated it took this long to come to the House floor.

“It’s crazy that we’ve taken an extra six months while countries around the world are making decisions on these [chip] fabrication facilities that we’re not competitive with,” said Democratic Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia, speaking the day before the House vote. As a co-sponsor of the CHIPS Act in the Senate, he describes it as a “three-fer”: “It puts Americans to work, it sends a strong signal against China, and it helps with inflation because the supply chain on chips is what’s driving up the cost of cars. What part is not to like?”

Heavy reliance on Asia

America remains a leader in designing chips, semiconductors that have become increasingly ubiquitous with the development of everything from electric vehicles to thermostats connected to the internet.

But today, nearly 80% of global chip production takes place in Asia. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. has a near monopoly on producing the most advanced type of chips, which are used in smartphones, laptops, and military equipment. That is a vulnerability Beijing could exploit. Some see Taiwan, a self-governed island off the coast of mainland China, as increasingly susceptible to invasion. In addition, earthquakes could disrupt the island, which sits on the Pacific Ring of Fire.

“We have a very high level of dependency on a single potential failure point in Taiwan,” says Charles Wessner, a senior adviser for the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Renewing American Innovation initiative.

So Congress would like to inject federal funding through the $52 billion CHIPS Act, a long-term investment designed to boost chip manufacturing – including of the most sophisticated type – in the United States.

“I think everybody realizes that this is a national security issue for our country,” says Navy combat veteran and Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona, where Intel and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. are building new plants. “I’m not so concerned about the vacuum cleaner. It’s the fighter airplane. It’s the missile system.”

CHIPS, he says, “goes a long way toward addressing the problem.”

Senate versus House

The Senate included funding for the CHIPS Act in its U.S. Innovation and Competition Act (USICA), passing it 68-32 in June last year with support from 19 Republicans.

House Democrats say it took seven months to bring it to the floor because there was some dissatisfaction with USICA among both parties, and House committees were working on bipartisan solutions. When those efforts didn’t bear enough fruit, and it became clear that inflation was rising and likely to persist, Speaker Nancy Pelosi moved to bring a Democratic version to the floor.

“Everybody wants to get this done as soon as possible,” says a senior House Democratic aide.

On Jan. 25, Speaker Pelosi and Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, chairwoman of the House science committee, introduced the nearly 3,000-page America Competes Act, hailing its bipartisan development. A science committee staffer provided a list to the Monitor of dozens of bipartisan bills reflected in the act, many of which have already passed the House with strong Republican support.

“We know that we have done the homework openly and fairly,” said Chairwoman Johnson.

While Republicans acknowledge that their people on some committees, including science, had meaningful negotiations with their Democratic counterparts, they say those on many others did not. And even those who did were not included in drafting the massive legislation. Republicans have dubbed it the “Concedes” Act, because it strips out key provisions including export controls for countering Chinese military and industrial development. The legislation also adds an array of partisan priorities, among them protecting coral reefs, and incentivizing consumption of seafood from “well-managed but less known species.”

“Why did we take a focused, targeted act and subsume it into a close to 3,000-page piece of legislation that covers everything from wet suits to shark fins?” asks Nadia Schadlow, former deputy national security adviser for strategy and a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.

Representative McCaul says he told the administration it couldn’t use CHIPS as a carrot to get GOP support for such partisan policies. He says that in a phone call with Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo just days before Speaker Pelosi introduced the America Competes Act, the secretary had expressed support for bringing CHIPS to the House floor as a stand-alone bill.

A Commerce Department spokesperson said in a statement to the Monitor that while Secretary Raimondo appreciates the congressman’s advocacy, she “has been clear in both public and private conversations that the best way to secure that funding is as part of a larger package that also spurs broader scientific innovation and secures supply chains that underpin our economic and national security.”

A year into President Joe Biden’s term, as his approval rating hovers just above 40%, some Democrats are frustrated by the party’s perceived overreach – striving to pass sweeping legislation rather than focusing on pragmatic solutions that will help voters.

Rep. Elissa Slotkin, a Michigan Democrat, supported the House bill but earlier this week voted against a related procedural measure as a “shot across the bow.”

“After letting the CHIPS Act lay dormant in the House for more than 6 months, the leadership rushed a new version in the past week, allowed Republicans to politicize what is a largely bipartisan bill, and elevated expectations on what will actually pass into law,” she said in a statement, calling on Democratic leadership to get serious about compromise. “Passing a bill just through the House will do nothing to get microchips to the auto plants I represent.”

China’s strategic goals

Some see China’s growing economic influence as part of a larger Chinese Communist Party strategy to undermine America’s model of government and its global leadership.

“Our nation must be united and unwavering in asserting our global leadership and holding the CCP accountable,” said GOP Rep. Young Kim, noting that the House bill came to the floor as China is opening the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and using that world stage to project its image as a rising power.

China consistently rejects U.S.-style democracy and perceived unfairness in U.S. policies, says Bret Schafer, who follows foreign messaging and disinformation at The German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy. So Mr. Schafer was surprised to see that Chinese state media and diplomats have had almost nothing to say about what is unquestionably an anti-Chinese bill.

“I think they may avoid touching this because I think it’s in China’s interest to not have this passed soon,” says Mr. Schafer. “For Chinese state media to show that this is a real sore point for China could be seen as a way of catalyzing both sides to come together and pass it.”

Staff writer Dwight A. Weingarten in Washington contributed to this article.

The Russian public doesn’t want war, but is anyone listening?

There seems to be little appetite for a war with Ukraine or NATO among Russians, be they peace activists or members of the general public. But many feel the choice for war isn’t theirs to shape.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As Russia faces off with NATO over Ukraine, the country’s beleaguered liberal intelligentsia are speaking out against the Kremlin policies which they say risk starting open conflict.

A tough anti-war statement signed by over 5,000 people warns that in the current crisis “the citizens of Russia are becoming hostages to criminal adventurism,” and urging authorities to step back from the brink of war.

But despite broad lack of enthusiasm for war among the Russian public, the petition has received little attention, and the people seem resigned to the possibility.

“It seems that, although society is afraid of war, people are internally prepared for it,” said Denis Volkov, director of the Levada Center independent pollster. “What people say most frequently is, ‘We don’t want war. We are scared of it, but it keeps coming closer and closer.’”

“The nonstop message in the media is that Putin is always right and NATO wants to attack Russia,” says Boris Vishnevsky, a St. Petersburg legislator and petition signatory. “A lot of people in the mass media don’t seem to believe that the danger of war is real, or perhaps they just don’t think they can do anything about it.”

The Russian public doesn’t want war, but is anyone listening?

Eight years ago, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the Kremlin’s confrontational policies brought out tens of thousands of peace marchers to the streets of Moscow, even as polls showed huge majorities of the public enthusiastically in favor of President Vladimir Putin’s defiance of the West.

Today, amid the Kremlin’s standoff with NATO over Ukraine, the mood is very different for both peace advocates and the public.

Russia’s beleaguered liberal intelligentsia are still speaking out in a tough statement signed by over 5,000 people, warning that in the current crisis “the citizens of Russia are becoming hostages to criminal adventurism,” and urging authorities to step back from the brink of war. The petition is signed by hundreds of rights activists, artists, filmmakers, musicians, journalists, scientists, and opposition politicians.

In the past, such a political challenge would have inspired open protests by like-minded members of the public, and at least be widely noticed in the Western media. But the anti-war petition, published on the website of the Ekho Moskvy radio station, appears to have garnered almost no attention.

Meanwhile, opinion polls and focus groups conducted by Russia’s only independent public opinion agency, the Levada Center, show that while majorities support the Kremlin and blame the West for the gathering war clouds, there is no appetite for a conflict in Ukraine, only pervasive fear and a sense of inevitability.

“The overwhelming mood today is despondency,” says Masha Lipman, senior associate at the PONARS Eurasia program at George Washington University. “This talk of war is something people hear about on the daily news. They are not unaware of it, and much of the public accepts the Kremlin narrative. But unlike the past, when people rejoiced at the annexation of Crimea, the mood now is very sour.”

“Russian public opinion is not a constraint”

A December survey by the Levada Center found that half of Russians believe the U.S. and NATO are to blame for the conflict in Ukraine, while 16% fault Ukraine and just 4% think Russia is responsible. In the same poll, 56% of Russians said they fear a big war could break out between Russia and NATO, slightly down from the 62% who feared a new world war a year ago.

Yet just two years ago, in another Levada poll, almost 80% of Russians said relations with the West should be defined by bonds of friendship, while 16% described the West as a rival, and just 3% as an enemy.

“It seems that, although society is afraid of war, people are internally prepared for it,” Denis Volkov, director of the Levada Center, said in a Radio Liberty discussion of focus groups with Russians about the crisis. “What people say most frequently is, ‘We don’t want war. We are scared of it, but it keeps coming closer and closer. We are being dragged into a war against our will.’”

“Russian public opinion is not a constraint for Russian authorities. It is taken into consideration, but it doesn’t restrain them,” he added.

For signatories to the anti-war statement, there is also a weary sense of hopelessness. Over the past year, as war fever has spiked, Russian authorities have cracked down on all manner of dissent, jailing anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny, shuttering human rights groups, marginalizing independent media, and even suppressing permitted opposition organizations like the Communist Party.

“We are gathering signatures, and we’re lucky that Ekho Moskvy will publish” the statement, says Leonid Gozman, president of the Union of Right Forces, an opposition nongovernmental organization. “The state blocks our voice, and even if we get mentioned, there is no chance for us to speak. There is no dialog. ... I haven’t been arrested yet, but the risk is definitely there. I only do this to preserve my self-respect.”

Boris Vishnevsky, a member of the St. Petersburg legislature with the liberal Yabloko party, says that even independent Russian media has paid scant heed to their appeal for peace.

“The nonstop message in the media is that Putin is always right and NATO wants to attack Russia,” he says. “A lot of people in the mass media don’t seem to believe that the danger of war is real, or perhaps they just don’t think they can do anything about it. Everything depends on the mood of our leader.”

Liberation of Ukraine?

The Kremlin has consistently denied any intention to invade Ukraine, and insists all talk of Russian war preparations is a NATO fabrication.

But Sergei Markov, a former Putin adviser who often reflects the views of Russia’s security hard-liners, says that war is indeed coming.

“It will not be a war against Ukraine, but to liberate Ukraine” from the grip of the pro-Western government that took power after a street revolt in 2014, he says. “A military operation now would prevent a wider war in future. ... As for this small group of pro-Western [signatories of the anti-war petition], they are not liberal. They are a group of traitors.”

The strange ambiguity of the current Russian public mood would be deeply shaken should war actually erupt, says Ms. Lipman.

“It’s odd that Putin’s approval ratings haven’t been affected one way or another during the course of this crisis,” she says. “But if an actual war, with violence and real pain, should happen – God forbid – this complicated moment will be gone, and everything will change.”

Black History Month: These writers’ messages still ring true

For our commentator, looking back at her college literature anthology affirms how central all peoples’ experiences are to American history. She’s also reminded how current the past can be.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Maisie Sparks Correspondent

One of the books I’ve carried with me since college is an anthology filled with works by Black writers. I knew it would never grow old, and it hasn’t.

Excerpts from the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano introduced me to the resilience of an 11-year-old boy who was kidnapped from his home in modern-day Nigeria; introduced to slavery in Barbados and Virginia; and taken to England, where he learned to read and write, and later purchased his freedom.

Frances Watkins Harper’s poem “Bury Me in a Free Land” expresses a trauma so profound that she didn’t believe her weary soul could find rest in soil where slavery was sanctioned by the state.

Carter G. Woodson, who introduced the observance of Negro History Week in 1926 – the precursor to Black History Month – published the inalienable truth that Black lives matter nearly a century before it became a social media hashtag.

Should I have the desire to pick up and move for the 12th time since my college years, my coming-apart-at-the-seams anthology will travel along. I’ll call upon it as needed to help me find strength from a courageous past and the resolve to work for a more inclusive accounting of American history.

Black History Month: These writers’ messages still ring true

I have kept two books from my college years. One is about points, picas, and figuring out proportions. Little did I know that the copyfitting skills it covered were becoming obsolete at the very moment I was poring over that paperback. Graphic design software was gearing up during the 70s and would require a different set of skills to create printed materials. And the internet was about to determine whether the written word would be printed at all.

I don’t know why I’ve carried this book with me from house to house over the past 45 years. Perhaps I’ve feared tossing it out as much as I feared the professor who wrote it and was waging a personal war against grade inflation. Based on my experience, he was winning.

The second book is an anthology filled with works by Black writers. I know why I’ve kept this thick tome. I knew it would never grow old. I knew I’d need its words for the rest of my life, and I have. I’ve pulled it off the shelf every time I wanted to accurately recall a Langston Hughes poem or review Frederick Douglass’ 1852 Independence Day oration. I’ve borrowed inspiration from its pages to see how other writers turned a phrase, and I’ve sat with it, especially during the past few years, to see if racial discourse has changed over America’s centuries. Not so much.

Whether they were writing autobiographies, eulogies, speeches, poems, songs, or stories, Black writers captured a people’s history in the way only a people can capture their experiences, with feeling and diversity. There was and is no one way to gather up the life of a people into one narrative, so the anthology gave me a sampling of the myriad ways Black people tried to cope with an environment that fought their flourishing.

From autobiography to poetry

Excerpts from the autobiography of Olaudah Equiano introduced me to the resilience of an 11-year-old boy who was kidnapped from his home somewhere in modern-day Nigeria; introduced to slavery in Barbados and Virginia; and taken to England, where he learned to read and write, and later purchased his freedom. He then used his story as one of 12 million stories that could have testified to the need to end slavery and human trafficking.

I read Frances Watkins Harper’s poem “Bury Me in a Free Land,” which expresses a trauma so profound that she didn’t believe her bones or weary soul could find rest in soil where slavery was sanctioned by the state.

I came to respect the effort and skill needed to write in Negro dialect, and the hope that is hidden in the blues, and work and prison songs. Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask” confirmed the duplicity of spirit necessary for people to survive the cruel and unusual incarceration known as slavery. I read a speech by Robert Brown Elliott, a U.S. Representative from South Carolina, who on Jan. 6, 1874, gave a well-reasoned argument for the federal government to do its duty to protect the civil and political rights of all its citizens.

Black lives have always mattered

When Carter G. Woodson introduced the observance of Negro History Week in 1926, the precursor to Black History Month, it wasn’t to make Black history a sidebar to American history. As he explained, African American contributions “were overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them.”

When Black history – or the history of any people for that matter – is not given equitable footing in a nation’s historical or literary works, the silence says those individuals didn’t make a worthy contribution to their nation or their world. For Woodson, that was unthinkable.

It was and is critical that Black Americans as well as every American have a comprehensive grasp of the people, policies, and cultural philosophies that have shaped and continue to shape the lives of all Americans. Woodson published the inalienable truth that Black lives matter nearly a century before it became a social media hashtag.

Learning from the obsolete

How we communicate is always changing. Today, there’s a plethora of ways to get information that have nothing to do with points, picas, or figuring out proportions. What is still needed, however, is an inclusive and settled understanding of history, even history that is merely a year old.

Should I have the desire to pick up and move for the 12th time since my college years, my coming-apart-at-the-seams anthology will travel along. I’ll place it on a convenient shelf in the new home and call upon it as needed to help me find strength from a courageous past and the resolve to work for a more inclusive accounting of American history. My anthology has been an invaluable asset – a counterbalance to narratives that would try to erase the tragedies and triumphs of the only people systematically enslaved in these united states.

As for my copyfitting paperback, I pondered selling it or tossing it, but decided to keep it. While I could get 15 bucks for it online, I’ve come to know its greater worth. It serves as a reminder always to be on the lookout for obsolete ideas, processes, procedures, and laws that are used to deny civil rights, political access, and human dignity to us all.

Maisie Sparks is the author of “Holy Shakespeare!” and other works.

Difference-maker

What can a string ensemble do? Harmonize community, calm baby.

Music can be a personal and social solvent. From helping parents compose lullabies to performing music that tackles social issues, Palaver Strings programs calm and connect community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Palaver Strings uses “music where words fall short” to calm and unite community, says Matthew Smith, a cellist and educator in the musician-led string ensemble and nonprofit organization.

The Portland, Maine-based organization addresses social issues, ranging from racial justice to coral reef conservation to family unity, with classical music. It engages with communities in concert halls, as well as in day cares and hospitals, and helps parents compose lullabies for their babies.

Creating music and programming that centers human connection is a sentiment so universal that it can resonate, for example, through a sorrowful piece about Emmett Till, a Black 14-year-old murdered in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of whistling at a white woman, as well as in the bountiful spirit of a childhood lullaby.

Caitlin Gillespie, an expecting mother putting a struggle with homelessness, excessive substance use, and incarceration behind her, was skeptical when a Boston Medical Center worker introduced her to the Palaver’s Lullaby Project in 2017. But, with the help of a Palaver musician, she crafted an original lullaby. When she played it on her phone for her newborn, she says, “it was a beautiful thing.”

That “beautiful thing” is Palaver’s medium for social change.

What can a string ensemble do? Harmonize community, calm baby.

Caitlin Gillespie, an expecting mother putting a struggle with homelessness, excessive substance use, and incarceration behind her, was skeptical when a Boston Medical Center worker introduced her to the Lullaby Project in 2017.

The songwriting collaboration with the Palaver Strings ensemble guides new and expecting parents to craft original lullabies for their children. What, she wondered, could crafting a song with classically trained violinists and cellists from premier music schools do for her and her unborn child?

That question goes to the core of Palaver Strings’ mission. The musician-led string ensemble and nonprofit organization based in Portland, Maine, uses classical music to address social issues, ranging from racial justice to coral reef conservation. It engages with communities in concert halls, as well as in day cares and hospitals.

It turns out, Ms. Gillespie did have something to gain from the Lullaby Project. She worked with two Palaver Strings musicians to craft the lullaby “Harper Rose.” Named for her now 4-year-old daughter, the heartfelt melody paints the promise of a good life and endless support. But it wasn’t until after the birth, one night in the hospital, that Ms. Gillespie felt its impact as she played the lullaby for her daughter the first time.

“It was just me and her,” she says. “I had it on my phone, and I played it. The nurse came in, and I was crying. Playing that song ... it was a beautiful thing.”

That “beautiful thing” is Palaver’s medium for social change. Though classical music is historically associated with the elite, ensemble members shared a desire to break away from the traditional trajectory of classical musicianship that included cutthroat competition, rigid style, and run-of-the-mill performances for the upper-class audiences that could afford to attend.

“Classical music has many, many benefits,” says Mine Doğantan-Dack, editor and contributor of a forthcoming book, “The Chamber Musician in the Twenty-First Century.” “For audiences to witness [classical music], it’s a very emotionally positive thing.”

Spirit of the “palaver hut”

Violinist Maya French and violist Brianna Fischler were students at Boston University when they started the ensemble in 2012.

“It was just a chance for our friends and colleagues that were in music school at that time ... to have more creative control of our artistic music-making, instead of just being in a school orchestra or a chamber group,” says Ms. French, now managing director of the group that includes 11 musicians.

Members share artistic and creative leadership in a model inspired by the “palaver hut” used in Liberia, a setting for discussion and conflict resolution. It was a concept Ms. French brought from a project she founded in high school to help Liberian youth.

By performing pieces from underrepresented composers, in urban auditoriums and rural community centers alike, Palaver commits to uplifting previously unheard voices and welcoming audiences that would otherwise have no invitation or inclination to engage with classical music.

The ensemble commissioned “Fear the Lamb,” a string orchestra piece by Akenya Seymour, a Black composer from Chicago. A recounting through music of the life and death of Emmett Till, a Black 14-year-old who was murdered in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of whistling at a white woman, “Fear the Lamb” had a timely performance this fall, given the trials of Kyle Rittenhouse and defendants in the Ahmaud Arbery case.

The audience in the 30-seat Somerville, Massachusetts, room was gradually pulled into the boy’s journey of racial injustice. The graceful melody crescendoed into a harsh cacophony that dissipated into an eerie whistle. Then a sharp silence symbolizing the boy’s death brought the audience and musicians together, bowing heads and closing their eyes.

This, says cellist Matthew Smith, managing director of education, is how Palaver “uses music when words sometimes fall short.”

Palaver prioritizes community outreach, registering as a nonprofit in 2015 and leading yearly initiatives such as the Lifesongs Project. Heralded by Mr. Smith in partnership with both Boston’s Ethos and the LGBTQIA+ Aging Project, it creates space for LGBTQ adults to share their stories through song. Since 2017, it has helped create 17 original compositions.

Boston resident Stanley Sayer participated in 2019. A retired market researcher with a little performance experience, the nonagenarian collaborated with violist Lysander Jaffe and violinist Kiyoshi Hayashi. His song “There Will Always Be Roses” is about a young love of his in a time when homosexuality was taboo.

“At the beginning, I had trepidation. I didn’t know what on earth this was going to be about,” says Mr. Sayer, echoing Ms. Gillespie’s hesitancy. “Then they gave you hints about how to go about finding things. ... They made it so simple. It was really collaborative.”

Mr. Sayer hoped that messages of acceptance would reach the listeners, piercing through differences and tying together human values. Palaver advocates music as a vehicle for social change, says Elizabeth Moore, programming director and violist with Palaver Strings.

“I feel like music and the arts tap into a side of us that opens us up to empathy in a way that arguments and words and essays and articles often maybe don’t,” says Ms. Moore. “There might be a window there to reach somebody who wouldn’t otherwise agree with you by creating more of just a human connection.”

Creating new doors to music

But Palaver didn’t want that feeling to be limited to the glamorous stages. The idea for the Palaver Music Center came about when the ensemble found that some of their most meaningful performances happened in classrooms and day care centers.

The center opened in 2019 in Portland and works with over 325 students of all ages per year, offering accessible and affordable music lessons and workshops.

“We thought it would be important for us to create an organization where both those things are honored equally, the things being performance and education,” says Mr. Smith.

A feasibility study found that Portland, given its growing eastern and Central African immigrant and refugee population, would benefit from the Palaver Music Center.

“One of our moms recently told me how she didn’t have access to music when she was younger [growing up] in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” says Mr. Smith. “She was saying how when the opportunity came for her son, who’s in second grade now, she was just really thrilled ... that a program like this exists.”

Creating music and programming that centers human connection is a sentiment so universal that it can resonate through a sorrowful three-movement piece about the murder of Emmett Till, as well the bountiful spirit of childhood. At least, that’s what Heather Lee Rose’s experience suggests.

As 2020 Lullaby Project participants, Ms. Rose and her wife, Darcy Rose, crafted “Tender Little Things,” first singing it to their son Camden when he was 5 months old. Now a toddler, he requests the song: “Cam’s lullaby, please.”

Ms. Rose says, “I thought there’s no better gift I can give to our baby than actually creating a song with him in mind.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Cities mix and match solutions to violence

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Two summers ago the streets of America’s cities swelled with protest over police violence against minorities. Demonstrators demanded that police budgets be slashed, with the money diverted to social programs. Then came a backlash. With murder rates rising – 30% in 2020 alone – voters favored mayoral candidates promising law and order.

Since then, these two national narratives have led to a possible healing moment. Cities across the country have become laboratories for fresh approaches to both public safety and community outreach.

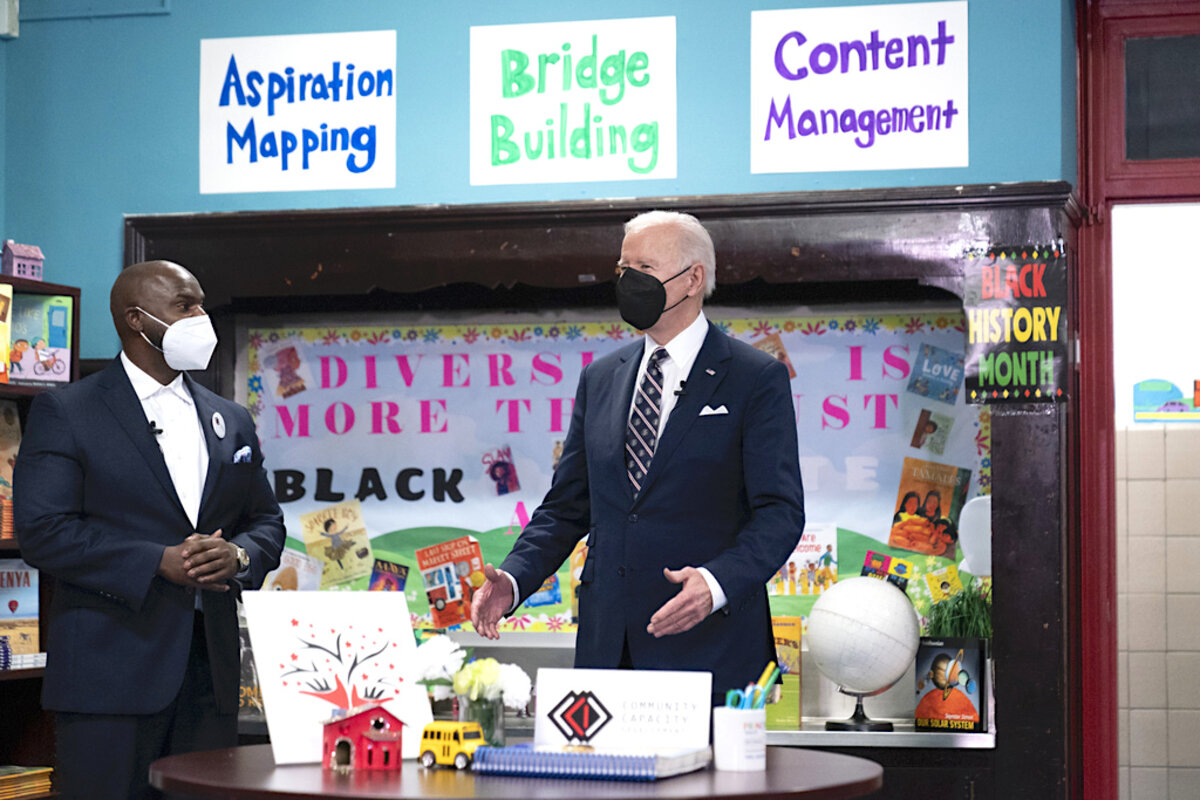

Their work has attracted federal attention. A good example was the Feb. 3 visit to New York City by President Joe Biden to back the reforms of a new mayor, Eric Adams, a former police officer and the second African American to lead the city. The mayor had just unveiled a plan for ending gun violence through a new collaboration between police and community stakeholders, including former gang members.

It is one of several blueprints redefining law enforcement in underserved communities following the heightened exposure of police killings in recent years. “We see evidence of a shift occurring,” said the Rev. Jeff Brown, who has spent decades addressing violence from within minority communities in Boston. “Love is an essential ingredient if we are going to be able to restore cities.”

Cities mix and match solutions to violence

Two summers ago the streets of America’s cities swelled with protest over police violence against minorities. Demonstrators demanded that police budgets be slashed, with the money diverted to social programs. Then came a backlash. With murder rates rising – 30% in 2020 alone – voters favored mayoral candidates promising law and order.

Since then, these two national narratives have led to a possible healing moment. Cities across the country have become laboratories for fresh approaches to both public safety and community outreach.

Their work has attracted federal attention. A good example was the Feb. 3 visit to New York City by President Joe Biden to back the reforms of a new mayor, Eric Adams, a former police officer and the second African American to lead the city. The mayor had just unveiled a plan for ending gun violence through a new collaboration between police and community stakeholders, including former gang members.

It is one of several blueprints redefining law enforcement in underserved communities following the heightened exposure of police killings in recent years. “We see evidence of a shift occurring,” said the Rev. Jeff Brown, who has spent decades addressing violence from within minority communities in Boston. “Love is an essential ingredient if we are going to be able to restore cities. We need love but also need justice. People are beginning to understand what that is, how difficult it is to achieve it, and they are anxious to get on with it and build it.”

Cities are combining hard and soft approaches. Some have increased police presence in the most violent neighborhoods while offering alternative activities to young people, such as summer camp. Former gang members are being deployed as “violence interrupters” to prevent disputes from escalating. Boston has focused on community renewal, such as boosting minority homeownership.

The Biden administration has pledged millions of dollars to city police departments to hire new officers, provide overtime pay, and stem the flow of illegal guns across state borders and on to urban streets. But as cities find a balance between law enforcement and civilian-based strategies, one model shows the value of tackling gun violence from the receiving end of it.

In recent years, hospitals in cities like Chicago and Boston have developed violence recovery programs that focus on helping victims of gun violence and their families heal. These initiatives combine physical and psychological care with access to other supportive resources like job-placement assistance and even relocation to avoid exposure to further violence. The idea behind those initiatives – that restoring individuals is a key element of violence reduction – has resonance for cities seeking to reduce violence by restoring communities.

“If you don’t understand the ‘why,’ we are never going to get to a real solution,” Christine Goggins, a violence recovery specialist at the University of Chicago Medical Center, told the Chicago Tribune. “The key to any type of change, reform, is understanding that culture. We have to get to those people, what leads them to committing violence?”

As cities grapple with gun violence and police reform in the wake of intense social justice protests, a new take on an enduring idea is finding practical expression: that justice, empathy, and compassion are cornerstones of stability and bulwarks of peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Olympic brilliance

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Whether we’re Olympic-caliber athletes or not, each of us can root for and strive to nurture God-given qualities of joy, strength, and grace – in any endeavor.

Olympic brilliance

Recently I was talking with someone who had competed for Mexico in the 1976 and 1980 Olympics. Now, more than 40 years later, he continues to work as a coach in his field. But those Games happened long enough ago that he wasn’t often asked, I could tell, about his experiences.

When I did inquire, a bright glow immediately came over him. We had a bit of a language barrier, but it was clear that his memories weren’t focused on what the judges or the audiences thought. As he spoke he was immersing himself once more in the great joy of the experience overall. And later, I didn’t even think to research how he had placed. What shone brighter than any shiny medals was his obvious love of participating!

Meeting him has changed how I am going to be watching the 2022 Winter Olympics. My perspective is going to be a little less medal-based and more quality-based. Our interaction has reminded me that what defines the substance of the Olympics – and, really, of life itself – is qualities more than medals.

What I’ve learned in applying the precepts of Christian Science in my life (including in athletics) is that what we each are as God’s individual, unique creation is what matters most. Jesus encouraged us to “judge righteous judgment” (John 7:24). I’ve found that the most effective way to approach this is grounded on a desire to discern the profoundly substantial spiritual qualities that God expresses in each of us, and that we can demonstrate in any endeavor.

This is because the infinitude of God is reflected in the infinitely capable nature of God’s creation. Mary Baker Eddy, the woman who founded the Monitor, states: “God fashions all things, after His own likeness.... Man and woman as coexistent and eternal with God forever reflect, in glorified quality, the infinite Father-Mother God” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 516).

Reflecting God’s nature is about more than simply being a decent person; it’s about the magnitude of good that God is constantly upwelling in each of us as His spiritual and pure children. It’s a joy to acknowledge this true, spiritual nature, and to be open to the ways in which God works in us. God’s brilliant qualities, such as unwavering devotion, grace, energy, joy, and goodness – aren’t at all short-lived. They remain active not just for a few hours, but permanently.

Such qualities are fully present in us all, waiting only to be acknowledged and expressed. Whether Olympians or not, each of us can experience for ourselves how invigorating and satisfying it is to nurture the reflection of God’s qualities within our hearts.

One of my favorite things to do is quietly pray for inspiration about nurturing a specific quality throughout the day. My most recent choice was calmness. It was something I had fun doing, just between me and God. In the many things I did that day, I started by acknowledging God’s presence, acknowledging the mighty power of God’s expression of peace in me and everyone. This shift in thought brought tangible progress in my work.

Many sports are timed. Some are measured. Others are judged. It may be, though, that whatever activities we’re involved in – athletic or otherwise – are first and foremost an opportunity for the supremely good nature of God to shine through. As the Bible puts it, “I also labour, striving according to his working, which worketh in me mightily” (Colossians 1:29). That’s what we can be rooting and striving for – God working in each of us, mightily and brilliantly.

A message of love

Celebrating US Olympians from a distance

A look ahead

Thanks for ending your week with us. Come back Monday, when we’ll take a look at the Biden administration’s policies on the southern border and get a better understanding of some American conservatives’ interest in the nation’s founding.