- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘You are not a burden’: Housing offers for Ukrainian refugees

Trudy Palmer

Trudy Palmer

The app Ukraine Take Shelter, created in record time by two Harvard University freshmen, connects Ukrainian refugees with people around the world ready to house them. As Avi Schiffmann, who came up with the idea, explained to The Washington Post, “What we’ve done is put out a super fast, stripped-down version of Airbnb.”

He and his classmate Marco Burstein worked around the clock to develop and launch the app in just a couple of days. A week after it went live on March 2, it had 4,000 people worldwide offering shelter, ranging from couches to spare bedrooms to vacation homes.

Now, there are roughly 7,000 hosts, the developers told the Monitor via email, adding that they have “received many messages and success stories from hosts and refugees.”

Obviously, Ukrainian refugees are more likely to seek housing in countries near them than in the United States. And lots of offers are coming from Europe. But when I typed my Midwestern U.S. city into the app, I found scores of people, rippling far out from the city center, eager to open their homes.

You could argue that it’s easy for Americans to offer shelter since they’re not likely to find takers 5,000 miles away. But the sincerity in the postings dispels that cynicism:

And those are just the headlines. Expand an entry to get details, and the sincerity often expands as well:

And that grandmother eager to share her home? She’s offering to help pay airfare too.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Sanctions start to get real for Russians

So far, the world’s sweeping economic backlash to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is primarily being felt by those Russians most engaged with the West. But everyone knows the bite will soon be felt more broadly.

Barely two weeks ago, most Russians enjoyed relatively prosperous, consumerist lives, with access to goods and services familiar to anyone in the West.

But Russia’s so-called special military operation in Ukraine has stirred up a blizzard of economic penalties in response. Amid that storm, Russians’ place in the interconnected global economy seems about to end.

It’s still early days. Grocery stores have well-stocked shelves and only minor price increases so far. There are lines in pharmacies, where supplies of imported medications are being snapped up, but no signs of panic-buying yet.

It is mostly those with Western connections such as family, business interests, or travel plans who have started to seriously notice the economic woes.

“I suppose we can get along without our favorite fast foods, games, and movies. It’s nothing compared to what those people in Ukraine are going through,” says Nadezhda, a TV producer. “But what about the future? Unemployment and social marginalization will lead to more crime.”

“I see bad times ahead. I feel sorry for the youth, who have no experience of the troubles we went through in Soviet times,” says Olga, a retired teacher. “They already breathed the air of freedom and tasted a new life. Poor kids!”

Sanctions start to get real for Russians

Virtually overnight, Russia has become the most sanctioned nation in at least a century, if not ever.

Barely two weeks ago, most Russians enjoyed relatively prosperous, consumerist lives, with access to goods and services familiar to anyone in the West. They were able to travel, use their Russia-based bank cards in just about every country, order services online, and, like billions of the world’s denizens, communicate on universal platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

But Russia’s so-called special military operation in Ukraine has stirred up a blizzard of economic and financial penalties in response. Amid that storm – which includes the decision of brands like McDonald’s, Ikea, and Coca-Cola, as well as 300 more, to leave or “pause” their activities in Russia – and Moscow’s retaliatory measures, Russians’ place in the interconnected global economy seems about to end, perhaps permanently.

The Monitor has talked to more than a dozen Russians to try to gauge their initial experiences, and attitudes, about what looks to be an onrushing long, drawn-out, and life-changing crisis. Several “average” people agreed to speak frankly on condition their surnames not be used. A few well-known analysts spoke on the record, provided no political opinions that might be illegal under a new law on “fake news” be attributed to them.

The emerging picture suggests that everyone is aware that an economic storm is about to hit their lives.

Editor’s note: This article was edited in order to conform with Russian legislation criminalizing references to Russia’s current action in Ukraine as anything other than a “special military operation.”

It’s still early days. A drive around Moscow finds mostly scenes of normality, and little resembling panic.

Grocery stores have well-stocked shelves and only minor price increases so far. Most important, customers are still able to pay with their domestic bank cards – even if they bear the logo of recently departed Visa or Mastercard – thanks to a Russian project begun at the dawn of the sanctions regime eight years ago to develop a self-sufficient Russian payment system, which is now up and running.

There are lines in pharmacies, where supplies of imported medications are being snapped up, but so far no signs of panic-buying of staple foods – even though legal limits have already been put in place on amounts that can be purchased.

It is mostly those with Western connections such as family, business interests, or travel plans who have started to seriously notice the economic woes. For some, it’s the feelings of universal censure and isolation that hit hardest.

Nadezhda, a 40-something TV producer, says the plunging ruble, ban on receiving foreign currency, and skyrocketing interest rates (now at an eye-watering 20%) are all sources of concern.

“But right now I am feeling terrible about my daughter, who had to cancel her birthday trip abroad because the skies are suddenly closed,” she says. “She lost her money, but much worse is how it made her feel. ... I suppose we can get along without our favorite fast foods, games, and movies. It’s nothing compared to what those people in Ukraine are going through. But what about the future? Unemployment and social marginalization will lead to more crime. That’s my biggest fear.”

Antonina, a middle-aged homemaker whose husband is Ukrainian, says she isn’t worried about shortages. “If worst comes to worst, we’ll eat beetroot, like we did before,” she says.

But her husband, Yevgeny, a businessperson from Odessa who is a member of Russia’s huge Ukrainian diaspora, says it’s far more complicated than that. “There is no work for me here anymore. I can’t receive payments from abroad. Transportation companies refuse to deliver containers, even if they hold permitted goods. Everyday life is collapsing. With growing repressions, I fear I will be labeled as a foreign agent if I continue working in an international firm. ... So, I have decided to emigrate.”

Some express resentment at being targeted for the perceived wrongs of Russian leaders.

“I hate the expression ‘collective responsibility.’ I never punished a whole class for the misbehavior of one pupil,” says Olga, a retired teacher. “I see bad times ahead. I feel sorry for the youth, who have no experience of the troubles we went through in Soviet times. They already breathed the air of freedom and tasted a new life. Poor kids!”

Closing doors

Ironically, those most immediately impacted appear to be people who have decided to leave Russia, out of dread for the future or opposition to Kremlin policies. Hundreds of journalists, information technology specialists, and other professionals have reportedly left Russia already, with many more scrambling to make that decision.

Hello Move is a Netherlands-based emigration service that offers end-to-end assistance for Russians seeking to relocate to Europe, including residency permits, legal advice, logistics help, and assistance in settling in. In the past two years the company aided about 250 Russians, mostly professionals, entrepreneurs, and students, to make that move. In the first few days of the “special military operation” that began on Feb. 24, it received 20,000 inquiries and signed as many new contracts as it usually does in a whole quarter.

The job is much harder now, says company CEO Yury Vilenskiy, because most European embassies and consulates in Russia have closed their doors. Meanwhile, almost all have closed their airspace to Russian planes, and Moscow has retaliated by closing Russian airspace to Western airlines.

“It’s more difficult since the change in the geopolitical situation, but we can still make these arrangements through countries whose doors are still open both ways, like Georgia, Armenia, Turkey, and a few others,” says Mr. Vilenskiy. He seems confident that solutions, or at least workarounds, will be found for most problems.

New currency rules in Russia and the ban on use of international bank cards are certainly an obstacle. “People are going to start using cash, the way they did in the 1990s,” he says. And, indeed, many people are recalling the cataclysmic ’90s, when Russia’s economy collapsed and people were forced to find innovative ways to survive.

One possible avenue of relief may be on the horizon. Russian banks are reportedly teaming up with the Chinese UnionPay system to issue cards based in Russian ruble accounts but usable in the 180 countries that accept UnionPay.

“Our own payment system is certainly an achievement. It enabled us to avoid panic in the first days,” says Ivan Timofeev, an expert with the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “Currently, all ruble transactions are working well. ... But in the longer run, the condition of Russia’s middle class will depend on resources. Sure, we can have a circulation system, but will people have money to pump into it?”

The government also appears to be attempting to mitigate the effects of the Western multinationals’ withdrawal from Russia by creating a means to nationalize the businesses left behind. Under the proposed law, any business shut down “in the absence of clear economic reasons” can be taken over by the state, which will keep it running, until it is sold as a new company to a domestic owner.

Time running out?

Andrei Kolesnikov, a veteran Moscow-based political analyst, says that so far most people seem to be coping with fast-changing circumstances, but not questioning their political convictions.

“People are going to shops, spending money that’s losing its value on goods that are fast disappearing. But it doesn’t yet affect their attitude to the conflict,” he says.

“I am a member of a small subset of people who could be persecuted politically” as a longtime Kremlin critic. “But I can’t access money. Visa and Mastercard did Putin a huge favor, because now we can’t use our cards abroad. I understand the logic, that we are all responsible for our president. But I am not responsible, nor are so many of my colleagues. Yet we are the first ones paying the price.”

Challenges of replacing Russian oil

The hunt for oil to replace banned Russian imports is forcing Washington into some difficult choices. But in one case, it might also lead to a happier outcome.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

When President Joe Biden declared a ban on Russian oil and other energy imports, he said he was striking a “powerful blow to Russia’s war machine” in Ukraine.

But the move means Washington must find alternative sources of crude elsewhere, and its search for new supplies, from Venezuela to Iran to Saudi Arabia, underscores the challenge of feeding the oil-dependent U.S. economy while preserving President Biden’s values-based foreign policy.

President Biden’s bid to revive the Iranian nuclear deal, and thus restart Iranian oil exports, had seemed on track until Russia – a key signatory of the accord – scuppered it last week. Now Western diplomats are seeking creative ways out of the impasse.

Washington’s hope of seeing more oil from Saudi Arabia has put Mr. Biden in a moral quandary. He had banned offensive weaponry sales to the kingdom and refused to deal with de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman over human rights concerns. Now Riyadh hopes it can escape such punishment by pumping more crude.

In Venezuela, though, the picture is brighter. A move to end U.S. sanctions against the biggest South American oil producer could help break a deadlock in talks between President Nicolás Maduro and the opposition, which could strengthen the rule of law and improve the country’s humanitarian situation.

Challenges of replacing Russian oil

When President Joe Biden announced a U.S. ban on Russian oil and other energy imports last week, he called the sanction a “powerful blow to Putin’s war machine” currently invading Ukraine.

But the move means Washington must find alternative sources of crude elsewhere, and its search for new supplies, from Venezuela to Iran to Saudi Arabia, underscores the challenge of feeding the oil-dependent U.S. economy while preserving President Biden’s values-based foreign policy.

“There is an energy crisis in the world. If you want to focus on values, you have to pay more,” says Umud Shokri, a Washington-based energy security adviser and expert in energy diplomacy.

That blunt fact, combined with the West’s need for oil, is leading U.S. diplomacy in novel directions.

In Venezuela, oil may turn out to be the lubricant for stalled negotiations between the government and opposition, and for an end to U.S. sanctions.

In Iran, the global thirst for oil could rewrite the rules governing nuclear negotiations with the government in Tehran.

And Washington appears ready now to deal with Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman, hitherto a pariah for the Biden administration over allegations that he ordered the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

“The international energy market has its own dynamics independent of values, or whether an energy-producing country is democratic or not,” Mr. Shokri points out.

Here’s a look at how the U.S. ban on Russian oil is creating new diplomatic dilemmas – and opportunities – elsewhere.

Iran nuclear deal still elusive

In Iran, Washington is rethinking multilateral diplomacy.

Diplomats had been hopeful in recent weeks that Tehran and the international community were on the brink of signing a deal that would have meant the end of sanctions on Iranian oil exports in return for a cap on Iranian uranium enrichment.

Russia threw a wrench into the negotiations in Vienna last week, however, by demanding that Russia-Iran trade be exempt from the sanctions imposed on Moscow in response to the Ukraine war.

Russia is a signatory to the original 2015 nuclear deal from which Washington withdrew under President Donald Trump in 2017 and is now trying to revive. Moscow’s agreement is required to resurrect the deal, and its demand has put the monthslong talks on pause.

Since Tehran has rejected any deal without Russia, U.S. and European diplomats have reportedly been mulling the idea of a stopgap, stripped-down accord that would enshrine the bare bones of an agreement to lift Western sanctions and limit uranium enrichment below weapons grade.

Even if that came to pass, though, Iran seems likely to press its advantage as an oil producer. On Sunday, a majority of Iranian lawmakers issued a petition urging the government to use the rising demand for its oil as leverage. “Now that the Ukraine crisis has increased the West’s need for the Iranian energy sector, the U.S. need for reduced oil prices must not be accommodated without considering Iran’s righteous demands,” the petition read.

“I am not optimistic that we will see a deal in the short-run,” says Umud Shokri, the energy expert. The West may be ready to lift sanctions on Iran that “have had no effect on changing regime behavior,” he believes. But Russia fears that open Iranian spigots would mean lower world prices.

U.S. ready to backtrack?

In Saudi Arabia, the U.S. relationship with its ally is pitting American energy needs against its values.

As one of the world’s largest oil producers, Saudi Arabia retains influence over OPEC’s output. It is also leading a war in Yemen that has killed more than 377,000 people, creating a historic humanitarian crisis.

The Biden administration has banned the sale of offensive weapons to Riyadh, and the U.S. president has refused to deal directly with Crown Prince Mohammed over his alleged role in Mr. Khashoggi’s death.

In pursuit of oil, however, Mr. Biden not only attempted to call the Saudi prince – a call the prince allegedly refused – but also is considering a visit to Saudi Arabia to publicly meet Crown Prince Mohammed.

“The crown prince has carried out repression and war because he thinks he is not going to be held accountable,” says Abdullah Alaoudh, research director for Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates at the Washington-based Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN) and son of a high-profile Saudi political detainee.

“Just imagine if he is fully embraced by the White House – what will he do then?”

The Saudi government has reportedly conditioned any increase in oil production on resumption of offensive weaponry supplies and legal immunity for the crown prince and his close advisers, who face multiple lawsuits implicating them in the murder of Mr. Khashoggi, including a lawsuit brought by DAWN, the organization Mr. Khashoggi founded.

U.S. officials refuse to comment on U.S.-Saudi talks. But by relaxing its stance toward Riyadh since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, “the Biden administration has given the crown prince the impression that they need him more than he needs them,” says Mr. Alaoudh.

A ray of hope for Venezuela

In Venezuela, home to the largest oil reserves in the world, U.S. efforts to ease its energy crisis could help jump-start a diplomatic deadlock.

U.S. sanctions on Venezuelan oil in 2019 sent a firm pro-democracy message, but observers say they also backed Washington into a corner. Caracas cozied up to Russia and further cracked down on political opponents; the sanctions worsened an already dire humanitarian situation that has forced millions of Venezuelans to flee their country; and there have been few opportunities to spark stalled negotiations between President Nicolás Maduro and the opposition.

“Ukraine changed the calculus,” says David Smilde, a senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America, offering the Biden administration a chance to “get out from under” the Trump-era sanctions. “Because oil and gas prices are so high and it’s now a national security issue, the U.S. may be more willing to negotiate sanctions with Maduro in order to help break the Venezuelan stalemate,” he says, though lifting sanctions would likely be a drawn-out process.

Even if it were fast, that would not make any immediate difference to U.S. oil supplies, points out Terry Lynn Karl, a professor at Stanford University and author of “The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States.” Production is low and could take a year or two to ramp up, she adds. “You don’t just turn a spigot and oil flows again and prices go down and everything is fine.”

But Venezuelan oil is attractive; transport costs are lower than they are from the Middle East, and refineries suited to Venezuelan heavy crude already exist on the Gulf Coast. The scent of an end to sanctions could bring Mr. Maduro back to the negotiating table in Mexico City, where talks with opposition leader Juan Guaidó stalled last fall.

Dr. Karl is cautious. “Right now, I don’t think this is an opportunity for democracy,” she says. “But it is a huge opportunity to create a negotiations road map with real benchmarks,” she adds, possibly improving the humanitarian situation and strengthening the rule of law.

“You don’t ever build democracy from the outside,” she says. “You can only assist.”

A deeper look

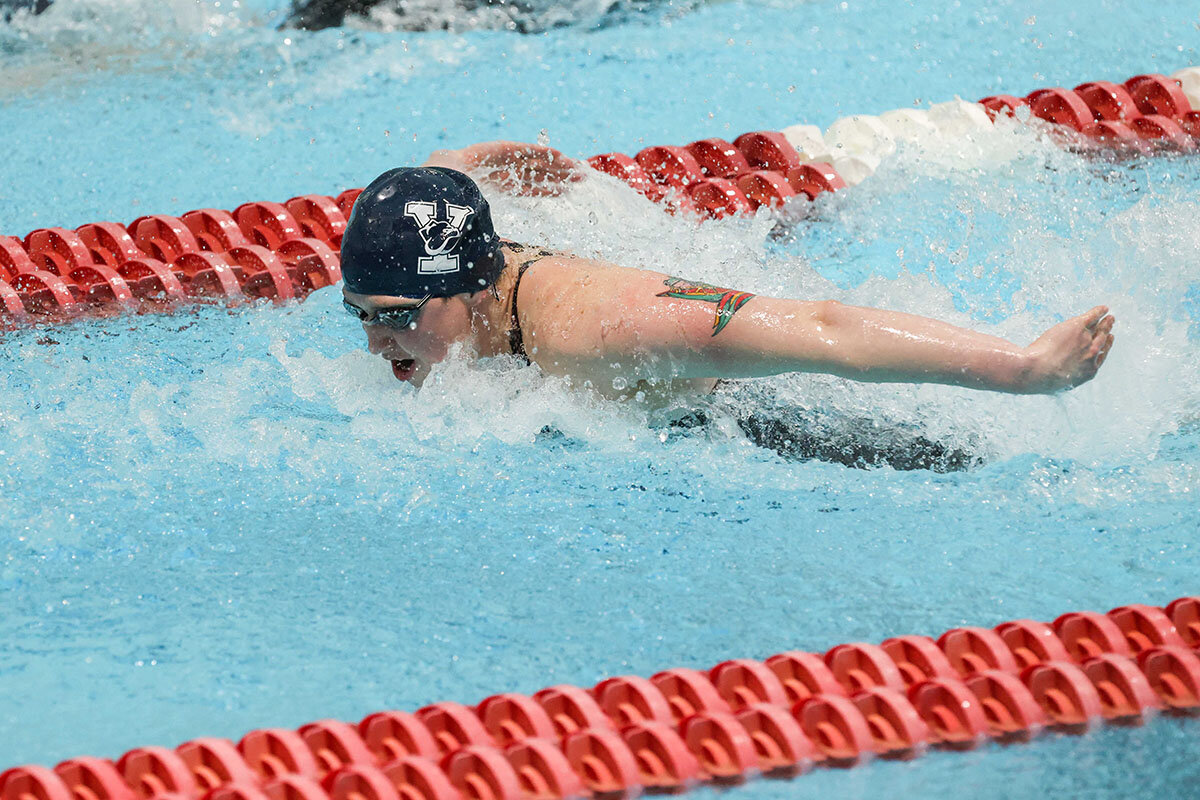

What’s fair for transgender athletes and their competitors?

Swimmer Lia Thomas’ participation in the NCAA’s national championships this week offers an opportunity to discuss the experience of transgender athletes and to consider what constitutes fairness when it comes to their inclusion in sports.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

Lia Thomas, a transgender swimmer at the University of Pennsylvania, is preparing to participate in the NCAA Division I championships this week after a record-setting season.

A number of people believe that Ms. Thomas should not be eligible to swim in the women’s category. They claim that she has an outsize advantage – not just in her considerable height, but also in physical strength having gone through male puberty. Others hail the athlete as a trailblazer for LGBTQ rights. The high-stakes controversy affects women’s sports, Title IX, and even the Olympics.

It’s a sensitive subject that many people are afraid to discuss publicly. But a good-faith debate is also underway. Sports figures, researchers, and observers are offering competing visions of how to preserve fair competition while also facilitating maximum inclusion within those parameters. Their conversations may ultimately influence how the public and sporting bodies think about these issues.

“There’s a really good debate among intellectuals with integrity right now about whether we should be trying to balance fairness and inclusion or continue to center fairness and allow as much of inclusion as possible within that structure,” says Doriane Coleman, a professor at Duke Law School.

What’s fair for transgender athletes and their competitors?

At a recent Ivy League swim meet, spectators were split over which side of the pool to look at.

At one end, several women jackknifed their bodies in flip turns for the final lap of the 500-meter freestyle. Their furious kicks churned the water and left white vapor trails in the sky-blue pool. On the other end, a swimmer named Lia Thomas had already finished and broken the Harvard pool record. In the 7.5 seconds it took for the second-place swimmer to arrive, Ms. Thomas adjusted her swimming cap, took off her goggles, and took in the scene around her. In an online video of the race, which has been viewed over 5 million times, a visible banner near Ms. Thomas’s lane bears the slogan “8 Against Hate.”

The sign, meant to oppose hatred of any kind by the eight Ivy League Universities, is a form of support for Ms. Thomas, a transgender woman. She’s made a splash not just in her sport but in the tempestuous culture wars. The fifth-year senior at the University of Pennsylvania has tallied record-setting wins in her first season competing in the women’s category. In a new and rare interview, Ms. Thomas told Sports Illustrated, “I want to swim and compete as who I am.”

A number of people believe that Ms. Thomas should not be eligible to swim in the women’s category at this week’s NCAA Division I championships in Atlanta. They claim that she has an outsize advantage – not just in her considerable height, but also in physical strength having gone through male puberty. Others hail the athlete as a trailblazer for LGBTQ rights. They believe that Ms. Thomas, as a transgender woman, should be allowed to swim in the women’s category. The high-stakes controversy – affecting women’s sports, Title IX, and even the Olympics – has spawned strident op-eds and social media posts by those who support and oppose Ms. Thomas’ participation.

It’s a sensitive subject that many people are afraid to discuss publicly. But a good-faith debate is also underway. Sports figures, researchers, and observers are offering competing visions of how to preserve fair competition while also facilitating maximum inclusion within those parameters. Their conversations may ultimately influence how the public and sporting bodies think about these issues.

“There’s a really good debate going on among intellectuals with integrity, about whether we should be trying to balance fairness and inclusion or continuing to center fairness and allowing as much of inclusion as possible within that structure,” says Doriane Coleman, a professor at Duke Law School who studies how evolving definitions of sex affect institutions such as sports.

A swimmer and a divided country

Those debates are taking place at a time when trans issues have become a prominent front in politics. In Florida, Republican Governor Ron DeSantis is expected to sign a bill into law that would, among other things, prohibit classroom instruction, especially in younger grades, “about sexual orientation or gender identity.” Legislators in Idaho are moving forward with a bill that would make it a felony for parents to help with gender-affirming health care – like hormone therapy – or to take their children to another state for medical procedures related to gender transitioning. In Texas, a new directive to investigate parents for child abuse who help their transgender children transition was temporarily stayed last week by a judge. Last month, South Dakota banned transgender girls and women from participating on female teams in school and college sports. It joins a growing number of states barring trans young people from school sports.

Ms. Thomas has become a proxy in these battles.

“I just want to show trans kids and younger trans athletes that they’re not alone,” the economics major told Sports Illustrated. “They don’t have to choose between who they are and the sport they love.”

Ms. Thomas, who is from Austin, Texas, started swimming at age 5 and swam competitively in high school. Some believe that this week she could break college records set by Olympic icons Katie Ledecky and Missy Franklin.

Sports Illustrated says that “the most controversial athlete in America” has become a “right-wing obsession.” Yet the controversy over Ms. Thomas doesn’t neatly fit into a right-versus-left culture war, says Cyd Zeigler, co-founder of Outsports, a publication that focuses on LGBTQ issues and competitors in sports.

“People who think that trans women should be treated as women in employment, in housing, in education, on their driver’s license, can all agree on that and supporting her – and, at the same time, say she doesn’t belong in women’s sports,” says Mr. Zeigler.

He has observed that many people in the LGBTQ community – including some who are transgender – do not believe Ms. Thomas should be competing in the women’s category.

Last year, a Gallup poll found that 62% of respondents believe that athletes in competitive sports should “play on teams that match birth gender.” Among Republicans, 83% agree with that statement, among Democrats, 41% agree, and among independents, 62% agree.

In the media and on social media, debates about Ms. Thomas often get nasty. In response, Lucas Draper, a transgender male athlete on the swimming and diving team at Oberlin college, penned a guest editorial in Swimming World Magazine. He called for civility and human decency in conversations about the athlete.

“No matter what your stance is on whether transgender athletes should be allowed to compete, it takes no real effort to at least identify them properly,” says Mr. Draper in a Zoom interview. “I didn’t think that it was fair that people were targeting Lia because she’s following the [NCAA] rules as they were set out.”

Requirements to swim

In elite sports, the rules governing transgender athletes are in flux at an international and national level. Various sports bodies have traditionally tested the testosterone levels in transgender athletes. (Similarly, many professional sports prohibit the use of anabolic steroids, which is a synthetic testosterone that boosts muscle mass and strength.)

The NCAA has historically required that transgender women undergo at least 12 months of testosterone suppression prior to competing in the women’s category. A longtime competitive swimmer, Ms. Thomas began hormone replacement therapy in 2019, two years prior to entering the women’s category, which met the NCAA’s requirements.

In January the NCAA announced it would leave requirements for transgender athletes to the national governing body of each sport. USA Swimming responded by setting new rules. It required a threshold of testosterone tests as well as a requirement that transgender athletes submit evidence to a panel that they do not possess an unfair biological advantage over non-transgender competitors. The NCAA subsequently decided that changing its rules midseason was unfair, which will make Ms. Thomas eligible to compete in this week’s tournament.

“There is a minority of extremely loud, extremely influential people who are pushing for no transition requirements,” says Mr. Zeigler. “Those people have a lot of influence in the NCAA.”

The NCAA did not respond to requests for comment.

The International Olympic Committee recently indicated that it is going to scrap its testosterone test requirement. That may be a boon for Ms. Thomas, who says that she’s aiming to qualify for the Olympics.

Those who oppose limiting the participation of transgender athletes contend that it’s not clearly established that testosterone confers an advantage for transgender athletes. Others in the academic community strenuously disagree, pointing to numerous primary research studies on muscle strength and muscle mass.

Joanna Harper, a Ph.D. student and researcher at the School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences at Loughborough University in the U.K., sits somewhere in the middle of those two views. Her first-ever case study? Herself. When she started her hormone therapy treatment in 2004, she began logging the rapid decline in her performance times as a competitive long-distance runner. Similarly, since Ms. Thomas started hormone therapy in May 2019, her performance times have slowed. But Ms. Harper says that even after testosterone suppression, transgender athletes are going to maintain some strength advantage.

“My initial paper was a study of distance runners,” says Ms. Harper, who has become a prominent voice in conversations about transgender participation in sports. “Strength doesn’t really matter for that sport, but strength does matter for swimming. So Lia will maintain both height and strength advantages over the cis women that she’s swimming against.”

Ms. Harper believes that eligibility shouldn’t just be purely determined by gender identity. She’s an advocate for factoring in testosterone levels. That stance has drawn the ire of some LGBTQ activists.

“I’ve been called ‘a traitor to trans people,’” she says.

Gregory Brown, a professor of exercise science at the University of Nebraska Kearney, believes that the focus on testosterone is ultimately too narrow. He says that those who’ve gone through male puberty tend to be taller and have larger wingspans, larger body mass, larger muscle fibers, larger hearts, and larger blood vessels.

“A trans woman still has XY chromosomes,” he says. “And there are effects of the Y chromosome that are very important to keep in mind as far as how the physiology works and administering hormones doesn’t necessarily negate those effects.”

Ms. Harper counters that the hormone therapy transition may actually create disadvantages for transgender women athletes, such as reduced muscle mass and a loss of aerobic capacity. The lower level of hemoglobin in blood also diminishes athletic performance. For her, any remaining biological advantages that Lia Thomas has are within a reasonable parameter.

“But the difference is not so large that it endangers women’s sports at all,” says Ms. Harper.

What would “fair” look like?

This year, Iszac Henig, a Yale swimmer who is a transgender man, has competed several times against Lia Thomas. Although he has had chest reconstruction surgery, he has not begun taking testosterone because he wanted to be able to continue competing on a women’s swim team.

To some, the coexistence of the two transgender swimmers in the same race brings into question the meaningful differences between men’s and women’s events.

“The same advocates who say Lia Thomas belongs in the women’s category, will also say that Iszac Henig belongs to the women’s category and belongs in the men’s category,” says Mr. Zeigler from Outsports. “How can somebody belong in both the men’s and the women’s category at the same time?”

Meanwhile, 16 of Ms. Thomas’s teammates sent an anonymous letter to their school and Ivy League officials contesting the swimmer’s right to swim in the category because of “an unfair advantage.” Several parents of swimmers on the team have also expressed their disquiet over the effect on the sport in anonymous interviews with the press.

To some, the biological debates over just how large or small an advantage transgender athletes may or may not have ultimately leaves too much margin for error. It would be fairer, they say, to simply draw the line between those who have and haven’t gone through male puberty.

Yet some sports thinkers have been mulling the question of whether it’s possible to preserve the women’s category – and at the same time facilitate opportunities for transgender athletes.

Nancy Hogshead-Makar, a former gold medal Olympic swimming champion and now a civil rights lawyer at the Women’s Sports Policy Working Group, opposes Ms. Thomas’s inclusion in the women’s competition. Instead, she proposes a Solomonic solution. She says transgender athletes such as Ms. Thomas could still compete in an exhibition race (in which her results would not count). It’s the swim meet equivalent of auditing a class.

But that idea doesn’t sit well with some.

“[I]n a way, what it does is put more focus on Lia Thomas, and I don’t think it’s great for them because it sort of ‘others’ them,” says Jon Pike, former Chair of the British Philosophy of Sport Association and a senior lecturer in Philosophy at The Open University in Milton Keynes, U.K. “If there’s eight lanes when you’re using one lane as an exhibition lane for Lia, then someone else could be in that lane, and you are, in fact, still excluding someone … for a result that won’t count.”

Mr. Pike has an alternate proposal. He recently co-authored a paper with Leslie Howe, a professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, and Emma Hilton, a biologist at the University of Manchester in the U.K., titled “Fair Game.” They believe it’s vital to exclude transgender women from the female category at elite levels of sports. Ms. Howe, a feminist philosopher, believes it isn’t fair to the other swimmers.

“I have a fair bit of experience in the past, as a lesbian, in participating in gay tournaments,” says Ms. Howe, who enjoys sports such as rowing. But, she adds, when it comes to mainstream sports, “it doesn’t matter what your sexuality is or your identity. When we get into playing, it’s about the bodies competing against each other, and we have to make those categories fair.”

Many sports – with the exception of, say, shooting and sailing – already factor what types of bodies are competing with each other, adds Mr. Pike. It’s the reason why adults don’t compete against kids or the reason why there are senior categories in golf and marathons. Weightlifting and boxing each have weight classes. Other games, such as the Special Olympics, include impairment categories.

To maximize inclusion, the trio proposes that the men’s category of sports be replaced by an “open” category that would include transgender athletes.

“You do not have to declare yourself to be a man in order to compete here,” says Mr. Pike. “We are not going to say, ‘You’re in the men’s competition.’ We’re going to say you’re in the open competition.”

Ms. Harper’s response to the idea is unequivocal: “No, I just can’t go along with that,” she says.

“Trans women are not men who think they’re women,” she adds. “Our gender identity is such a fundamental part of who we are.”

These different perspectives seem, perhaps, fundamentally irreconcilable. But Mr. Brown believes that, as Ms. Thomas’s story becomes more of a talking point in society, it will spur calls for various sporting bodies to institute compatible rules and a stable framework. He’s optimistic that if such debates continue in good faith, and if there’s willingness to make concessions, then it may be possible to agree upon an optimal solution.

“It’s to a certain extent like compromise in marriage,” he says. “If you’re saying you’re compromising in your marriage and you’re happy with the way things turn out every time, you’re not compromising. So that’s what we’ve got to have here - is that people are going to be willing to say, ‘OK, I’m not going to be 100% happy, but I’m going to get a compromise that I can live with happily enough.’”

A push against book bans

Banning books can have unintended consequences. In the United States, one result has been a redoubled effort to ensure those books – and the ideas they express – are freely available.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As school boards across the United States increasingly vote to remove books from library shelves and classroom curricula, community members are countering by amplifying awareness of those very books. These grassroots efforts range from free book drives to book clubs to lawsuits.

A month after the Wentzville School District, in a suburb of St. Louis, removed several books by or about people of color or members of the LGBTQ community, two Wentzville students, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri, filed a lawsuit.

Tony Rothert, director for integrated advocacy at the ACLU of Missouri and an attorney for the two students, says the lawsuit is the first of its kind to emerge out of the recent wave of book challenges in the U.S.

“We’re hoping to have a change in the [Wentzville School District’s] policy such that it’s more protective of students’ First Amendment rights,” he says.

In the meantime, the St. Louis bookstore EyeSeeMe is teaming up with In Purpose Educational Services on a donor-funded campaign that will send a free banned book each month to those who request one, as funding allows. The program has already received over $30,000 from people around the nation.

A push against book bans

As daylight turns to dusk and a closed sign dangles from the outside of EyeSeeMe, a St. Louis children’s bookstore, a glance through a side window reveals an after-hours banned books operation. Paper strips litter the floor. Books pass from hand to hand as eight volunteers package 600 copies of “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison to ship to kids and parents across the nation.

The bookstore is working in partnership with In Purpose Educational Services on the Banned Book Program, a donor-funded campaign that will send a free banned book each month to those who request one, as funding allows. Started just days after a school district in a suburb near St. Louis voted in January to remove copies of “The Bluest Eye” from its libraries, the program has already received over $30,000 from people around the nation. But Missouri residents aren’t the only ones taking action.

As school boards across the United States increasingly vote to remove books from library shelves and classroom curricula, community members are countering by amplifying awareness of those very books. These grassroots efforts – from free book drives to book clubs to lawsuits – differ in method but share a common mission to keep the world of books open for exploration.

“If the school doesn’t want to do it [provide challenged books], still push them to do it, but don’t wait for them to do it,” says Jeffrey Blair, co-owner with his wife Pamela Blair, of EyeSeeMe, the bookstore supplying banned books for free each month. “Let’s empower ourselves.”

The Banned Book Program and similar initiatives across the country show “not only how important people think books are, but what people are willing to do ... to highlight that book, to protect that book, to get more people to read that book,” says Kathy M. Newman, an associate professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania.

A First Amendment challenge

Written by Nobel- and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Toni Morrison and published in 1970, “The Bluest Eye” tells the story of a young African American girl growing up in Lorain, Ohio, who longs for blue eyes. It addresses a range of themes, including racism, beauty standards, and the girl’s abusive home life.

After a community member in the Wentzville School District challenged the book, objecting to it on the grounds that it includes pedophilia, incest, and rape, the district’s school board voted on Jan. 20 to remove the book from district libraries. Less than a month later, two Wentzville students, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri, filed a lawsuit saying the district’s removal of eight books, including “The Bluest Eye,” from school libraries violates their First Amendment rights.

Six of the other seven books the plaintiffs named have themes related to race or LGBTQ identity and were written by authors of color or LGBTQ authors. Their titles are “Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic,” by Alison Bechdel; “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” by George M. Johnson; “Heavy: An American Memoir,” by Kiese Laymon; “Lawn Boy,” by Jonathan Evison; “Gabi, A Girl in Pieces,” by Isabel Quintero; and “Modern Romance,” by Aziz Ansari and Eric Klinenberg. The seventh is “Invisible Girl” by Lisa Jewell, which explores a string of sexual assaults in a town and a teenage girl’s disappearance.

Brynne Cramer, chief communications officer for the Wentzville School District, confirmed via email that “The Bluest Eye,” “Gabi, A Girl in Pieces,” “Modern Romance,” and “Invisible Girl” have been returned to district libraries – the first two by school board votes in February and the second two because the challenges were dropped. The four other books named in the lawsuit have been removed from library shelves while they undergo review by a committee, said Ms. Cramer. The Wentzville School District declined to comment further.

Tony Rothert, director for integrated advocacy at the ACLU of Missouri and an attorney for the two Wentzville students, says the lawsuit is the first of its kind to emerge out of the recent wave of book challenges in the United States.

Despite the district’s partial reversal, the lawsuit is still ongoing.

“We’re hoping to have a change in the [Wentzville School District’s] policy such that it’s more protective of students’ First Amendment rights, that places some limits on how or why books can be challenged,” says Mr. Rothert.

T.K., a parent of one the plaintiffs who is using only initials in the lawsuit and interviews to protect the family’s anonymity, told the Monitor that books written by Black, brown, or LGBTQ authors can make students with similar backgrounds feel included. And banning them has the reverse effect. “If we’re not allowing kids to hear from people [through books] that may reflect or mimic some of the things that they’ve experienced, then we’re also telling them that you have to remain silent about things that you’ve experienced.”

Meanwhile, the Banned Book Program is working to ensure students retain access to books that highlight diverse experiences. The three books offered this month feature characters and/or authors of color.

“Literature should be a window and a mirror,” says Heather Fleming, founder and director of In Purpose Educational Services. “I’m tired of my experiences or my daughter’s experiences always being window experiences and not mirror experiences.”

“It seems a lot of African American books end up falling in that category of being banned,” adds Mr. Blair of the EyeSeeMe bookstore. “So, I think it’s important for us to be a part of this.”

Crossing state lines

Despite the increasing wave of book banning currently sweeping the United States, challenges and subsequent removals are nothing new. “Most of us don’t realize how often books are challenged,” says Dr. Newman, who started teaching a course on banned books over two decades ago.

But in the current period, book challenges are getting a brighter spotlight through social media. Consequently, interest is spreading across town and even state lines.

When Steve Ryan, an assistant professor of instruction at Temple University in Pennsylvania, heard that the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee removed “Maus” from its eighth-grade curriculum, he wanted to do something to push back.

Professor Ryan started a GoFundMe page to raise money for what he’s calling The Banned Wagon Project so that he can gift each graduating senior he teaches a banned book of their choice from a list of commonly banned or challenged books that he’ll compile.

He knows his actions won’t change policy in Tennessee, but “this is something that I can try to do ... to try to affect my little corner of the world,” he says. “And if one person takes away from it, you know, the inspiration to either stand up for people who are losing their voice, so to speak, or to take a stand against overreach ... then I call that a win. Even if somebody just carries that book around and remembers that words and ideas are important and they bring that forward into everything they do. That’s a win.”

Front-yard library

Around the same time, 700 miles away, at Savannah Arts Academy in Georgia, English teacher Rich Clifton engaged his students in a mock banned books debate. The next day, residents raised complaints at the district’s school board meeting about 10 books in school libraries containing content they viewed as inappropriate. Although the district confirmed on March 14 that no official book challenge has followed, Mr. Clifton, a teacher for 28 years, isn’t waiting to take action.

As a kid, Mr. Clifton spent hours in the public library, perusing the shelves and opening the cover of any book that caught his eye. Now, he’s replacing all the books in the little free library he built in his front yard with challenged books as a way of making sure they’re available. So far, former students, colleagues, and friends have contributed $1,400 to help purchase books for his library.

“It’s not so much [about] putting the books in the hands of students or children or anything like that,” he says.

“It’s making sure people don’t take it away.”

Editor’s note: All teachers and professors quoted in this article emphasized to the Monitor that they are speaking in their personal capacity and not on behalf of their school districts or universities.

In Pictures

Kenya’s forgotten Yaaku take back their language

In an increasingly connected world, many minority languages are in danger of disappearing. Native speakers seek their revival – not out of practicality, but dignity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Kang-Chun Cheng Contributor

And then there were two.

UNESCO declared the Yaakunte language extinct in 2020, though Juliana Lorisho and her grandfather speak the Kenyan language fluently. The problem is, they’re the only ones.

Undeterred by the odds stacked against her, Ms. Lorisho is working to build a school to revive the language. There are an estimated 4,000 ethnic Yaaku in Kenya, though the language took a hit a century ago when they were forced to integrate with the Maasai.

While formal education in Yaaku is still a long way off, Ms. Lorisho leads the “Revival of Yaaku Language” group chat on the messaging platform WhatsApp. Hovering around 33 participants, the group utilizes text and voice messages to learn new words. “It is a way for us to practice our culture and be differentiated from other communities we assimilated to,” she says.

In the meantime, she’ll keep strolling around Mukogodo, Kenya’s sole Indigenous-owned forest, and a place integral to the Yaaku identity. It’s there that Ms. Lorisho transcribes the stories of her grandfather, snacks on diiche fruit, and takes in the scenery of a land she’s quick to call “paradise.”

Click the “deep read” button above to view the full photo essay.

Kenya’s forgotten Yaaku take back their language

Grabbing the diiche, a prickly cactus bulb, away from my novice hands, Juliana Lorisho expertly uses a leafy branch to remove the spines before splitting the fruit open with her fingers. Unexpectedly bright juice splurts out, staining white fabric fuchsia. It tastes acerbic and fresh. The diiche is just one of the many edible fruits found within the Mukogodo, Kenya’s sole Indigenous-owned forest.

“It’s paradise, isn’t it,” Ms. Lorisho says, surveying the path lined with goldenrod-colored neeyna flowers.

This place is integral to Ms. Lorisho’s cultural identity. So are the words she uses to describe it. These are remnants of the Yaaku community, a tiny population of an estimated 4,000 in Kenya that was forced to assimilate with the Maasai ethnic group a century ago.

Ms. Lorisho and her grandfather are the two remaining fluent speakers of Yaakunte. In a last-ditch effort to save the language of her ancestors, Ms. Lorisho left a stable accounting position in urban Nanyuki and returned to the edge of the Mukogodo Forest with a dream of founding a school.

“I have a great mission towards reviving Yaakunte because many Yaaku are interested in speaking the language,” she says.

She was still seeking funds when UNESCO declared Yaakunte extinct in August 2020. With renewed urgency, she sought an interim solution. She launched a “Revival of Yaaku Language” group on the encrypted messaging application WhatsApp.

Hovering around 33 participants, the group utilizes text and voice messages to learn new words. “It is a way for us to practice our culture and be differentiated from other communities we assimilated to,” she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Land rights for Africa’s tillers

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Efforts to lift the world’s poor people have long focused on educating girls and empowering women. Yet achieving those goals has been slow in many regions. In Africa, for example, women contribute 70% of food production. Yet just 13% of women between the age of 20 and 49 have rights to land. The marginalization of African women in general costs the continent $60 billion a year, finds the United Nations, and most of that is caused by gender disparity in land ownership.

Yet across Africa, a growing number of initiatives are finding ways to solve the imbalance of land ownership between men and women. In countries like Kenya and Tanzania, for instance, rural programs run by women’s groups are teaching women their legal rights. Just as important, they are helping men see the economic advantages of granting greater land security to their wives and daughters. Once taught, values like justice and equality sink in, helping village societies transcend entrenched traditions.

As more countries create more equitable societies, African countries are learning that outdated and harmful social norms may not be as entrenched as they seem. They are giving way to higher ideals of justice that benefit all.

Land rights for Africa’s tillers

Efforts to lift the world’s poor people have long focused on educating girls and empowering women. Yet achieving those goals has been slow in many regions. In Africa, for example, women contribute 70% of food production, according to the World Bank. Yet just 13% of women between the age of 20 and 49 have rights to land. The marginalization of African women in general costs the continent $60 billion a year, finds the United Nations, and most of that is caused by gender disparity in land ownership.

Yet across Africa, a growing number of initiatives are finding ways to solve the imbalance of land ownership between men and women. In countries like Kenya and Tanzania, for instance, rural programs run by women’s groups are teaching women their legal rights. Just as important, they are helping men see the economic advantages of granting greater land security to their wives and daughters. Once taught, values like justice and equality sink in, helping village societies transcend entrenched traditions.

“For women’s land rights to be realized, they must not only be legally recognized but also socially,” Jacqueline Ingutiah, a Kenyan human rights official, told Ms. Magazine.

Although nearly all sub-Saharan countries have constitutions recognizing gender equality, traditional styles of governance still control land rights. That leaves women particularly vulnerable. As Transparency International notes, corruption is rampant in rural areas where local chiefs determine land rights. Women often face sexual servitude in exchange for permission to stay on their farms if their husbands die. Daughters are almost never seen as legitimate heirs.

Groups like the International Land Coalition are working with African partners to teach traditional leaders and others how to apply legal standards of gender equality in new land policies. Educating men can have a profound effect. A study conducted in Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya by Lori Rolleri Consulting and local partners surveyed male participants before and after a 12-hour course. The results, published in December, showed a dramatic shift in attitudes. Prior to the training, most of the men said land should be passed on only to sons, and few had formal wills. Afterward, many participants had created joint land ownership with their wives and made legal provisions to leave their lands equally to sons and daughters.

The shift in attitudes had another effect, the study found. Landownership laws that are more gender-neutral help reduce “family tension over land matters which had often led to serious consequences” such as violence and cyclical poverty.

As more countries create more equitable societies, African countries are learning that outdated and harmful social norms may not be as entrenched as they seem. They are giving way to higher ideals of justice that benefit all.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayer’s immediate impact

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Josh Niles

Is prayer effective in the face of conflict? A military veteran explores how acknowledging everyone’s God-given ability to value and do good can make a real difference in hostile situations.

Prayer’s immediate impact

History has certainly included a lot of conflict and war. At the same time, there have also always been individuals, groups, and nations advocating for peace and diplomacy, as well as greater understanding and patience regarding national and international differences.

How can we pray effectively when we’re right in the middle of a conflict – be it as big as a war visible the world over or smaller and more personal?

Behind every human conflict are individuals with viewpoints that are at odds. But one idea I’ve found so helpful is that regardless of what side of a conflict anyone is on, everyone has an innate spiritual sense and an unbreakable unity with God, good.

Christian Science teaches that God is the Principle of all goodness. If we accept that, then we also will accept that the ideas of this divine Principle (meaning all of us as God’s children) are completely at one with it. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, states, “Principle and its idea is one, and this one is God, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent Being, and His reflection is man and the universe” (pp. 465-466). The idea is not the Principle, but it can never be separated from its source in thought or action. The Bible illustrates this point throughout. It also emphasizes that man, God’s idea, has a heritage that is spiritual and incorruptible (see I Peter 1:3, 4).

The influence of this divine Principle, Love, is reaching every consciousness. Because each of us has an innate spiritual sense, we have the capacity to discern what is right, real, and true. This awareness can have an immediate impact, transforming character and heart, sometimes in an instant. It can also inspire in someone’s thoughts a right decision and sudden action that bring safety and peace to that moment.

Prayer based on this premise isn’t about trying to bring someone into alignment with how we see things; instead, it recognizes that every heart is actually naturally receptive to and oriented toward God, good, because we are each the expression of God. This kind of prayer can specifically challenge and break down the false concept that a person or a group of people has fallen into mental darkness and cannot help but strike out. The light of Truth, divine Love, reaches every consciousness.

In the early 2000s, I was serving in the military in the midst of a tumultuous war. I know that many people around the world were praying in a powerful way for peace and for an end to all the turmoil. But I also personally know a handful of people (and I’m certain there were many more) who were tirelessly and specifically at their “prayer post” each day to support on-the-spot safety and well-being for everyone touched by the hostilities. Cherishing man’s uninterrupted capacity to discern and value good was at the core of those prayers.

During my time in that conflict, I was leading soldiers and often had to make quick and informed decisions. Each morning I’d acknowledge in prayer that my highest duty was to be receptive to the influence of divine Love, God, and to respond right away to that higher spiritual impulse.

In one instance, after we had come under a precise and acute surprise attack, my initial thoughts were impulsive, and I gave bad directions to my platoon. But a moment later, I felt a stillness and clarity wipe away the mental fog. I knew that that stillness came from God. I immediately gave a countermand that was measured and safe for all. Instead of the situation escalating, it quickly de-escalated, to the great benefit of bystanders as well as those directly involved.

I can recall many instances where a safe and more peaceful path appeared right in the midst of a tactical operation. And I think for many of us, there was a growing awareness of a higher way through what sometimes felt like “the valley of the shadow of death” (Psalms 23:4). To me, this higher way was what Christ Jesus pointed his followers to – a profound awareness of the omnipotence of Spirit, God, that could lift all above the waves of fear and conflict.

Your specific support of the spiritual sense of each individual – whether aggressor or victim – is a powerful and direct help. In this kind of prayer watch, no one is left out; it reaches every level of combatant from rank-and-file to leader as Christ brings every thought into conformity with Truth.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, March 9, 2022.

A message of love

Sandstorm hues

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, Washington Bureau Chief Linda Feldmann looks at how President Joe Biden is handling Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – and what Americans think of his performance.