- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A costly winter looms. How much will the West be willing to sacrifice?

- Another year, another US border crisis. Could 2023 be different?

- Gulf leaders find new partner in China, challenging US dominance

- Margaret Sullivan: ‘There is a moral component to a life in journalism’

- Building Men teaches students what manhood can really mean

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A nuclear fusion breakthrough, six decades in the making

Headlines today hint at the dawn of a new energy age. But they also show the power of persistence.

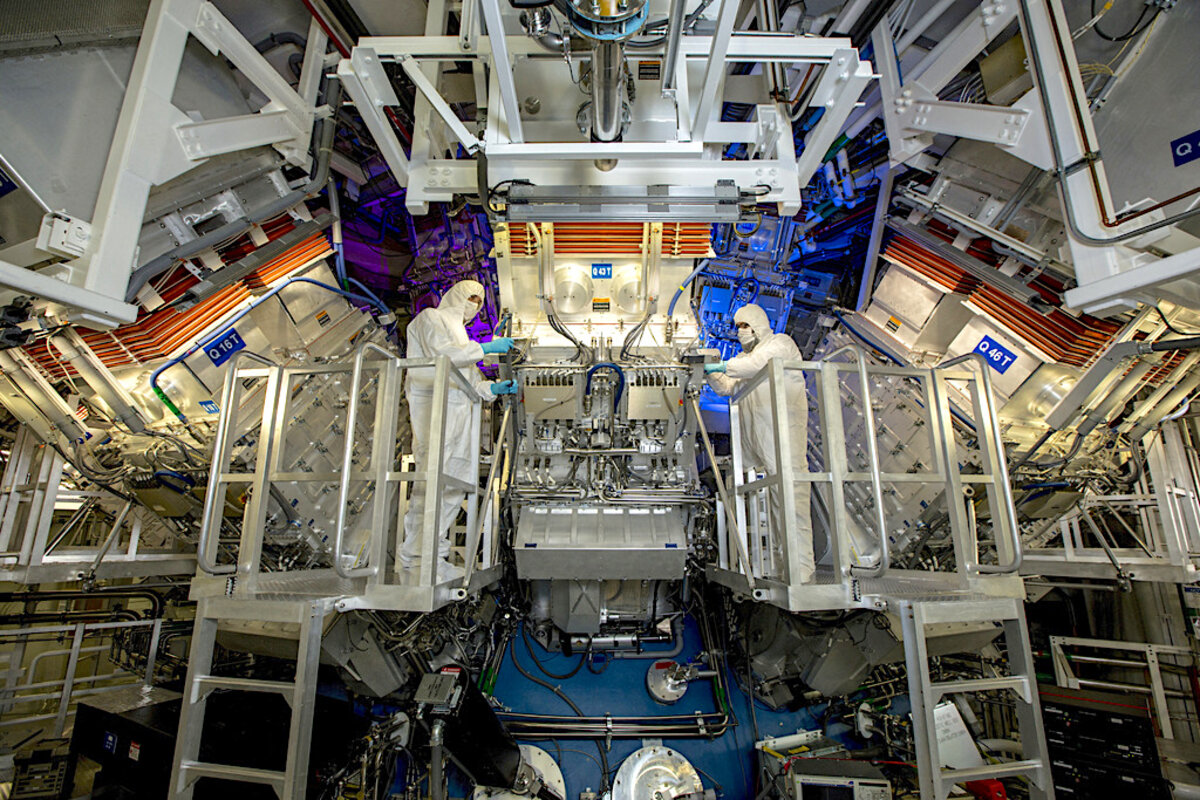

For the first time, a nuclear fusion experiment has produced more energy in a reaction than was used to ignite it, researchers at the Energy Department’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California said Tuesday.

The energy production, which happened in the wee hours of Dec. 5, lasted just a fraction of a nanosecond. Yet behind that was decades of envisioning and working toward this moment.

And it will take years more work if the technology is to move from the lab to the world’s power grids. Advances are also happening, of course, in other energy sources beyond fossil fuels, from geothermal to solar. But the quest for nuclear fusion is well worth watching.

“Each experiment we do is building on 60 years of work in this field,” Alex Zylstra, principal experimentalist on the project, said Tuesday at an announcement event livestreamed from Livermore.

One small example: This particular experiment came after seven months of labor to create the tiny capsule to contain the deuterium and tritium (hydrogen isotopes) that were bombarded in the lab by the world’s most powerful laser system.

In short, just as it takes a lot of energy to force the nuclei of two atoms to fuse (giving off energy in the process), it takes a lot of grit and commitment by teams of humans to make that happen.

The work is going on not just at the Livermore Lab but also – as the Monitor has reported – in Europe’s ITER facility, which is pursuing a different approach to harnessing fusion. Private companies also promise to play increasingly important roles.

Along the way, the participants are cheering one another along.

“We’re very supportive of each other in this community,” Tammy Ma, who leads Livermore’s Inertial Fusion Energy Institutional Initiative, said at the Tuesday event. “We really just want to see fusion energy happen” as an abundant and low-carbon resource.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

A costly winter looms. How much will the West be willing to sacrifice?

In Europe, a civic responsibility ethos is taking hold as residents dim lights and lower thermostats to confront brewing economic and energy crises. Across the Atlantic, Americans are taking a more individualistic approach to resilience.

-

Lenora Chu Special correspondent

-

Cole Sinanian Staff writer

-

Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned long-held assumptions about access to cheap energy upside down.

In Europe, inflation is squeezing consumers, who are already worried about a possible global recession, just as energy prices are skyrocketing with the looming arrival of winter. Governments scrambling to shore up energy supplies are asking individuals, companies, and communities for sacrifices that are unfamiliar to generations of Europeans.

A sense of common solidarity is driving many Europeans to turn down thermostats, don sweaters, or even take on the night shift so their companies can save on energy costs. In France, Strasbourg’s renowned Christmas market has fewer lights. Next door, Berlin has launched a series of ad campaigns encouraging the public to cut consumption.

In the United States, farther from the epicenter of the scarcity crisis, conservation is a tougher sell. But high energy prices are still hitting American pocketbooks, and the convergence of challenges is galvanizing people to rethink some habits as the larger climate crisis looms.

“Conflict, wars, rationing, things simply not being available – that’s something that’s essentially alien to the American historical experience,” says Ian Lesser, executive director of the Brussels office of the German Marshall Fund.

But, he adds, with the pandemic as well as the current challenge of energy insecurity and high inflation, “it may be that America and Europe actually converge in their approaches over time.”

A costly winter looms. How much will the West be willing to sacrifice?

This tiny hamlet of 1,400 in northern France is shrouded in silence by 9 p.m. on winter nights. At that hour, most residents are putting their children to bed or settling on the couch after a hard day’s work.

But not Rémi Pantalacci.

These days he is just clocking in, walking through the bamboo-lined entrance of Pocheco, an eco-friendly envelope manufacturer established here in 1928. In October, his boss asked production staffers if they would be willing to switch to the night shift in order to cut costs for the company, as energy prices have soared across Europe. Mr. Pantalacci immediately raised his hand.

Like the others who volunteered to make the change, he gets a bonus. He says he’s drawn to the personal growth inherent in working overnight, which requires more autonomy in problem-solving. But he is also responding to a deeper sense of civic responsibility to help confront the brewing economic and energy crises in Europe.

“In this current climate, we’re in a period of uncertainty. No one can say how long it’s going to last,” he says as he takes up his post, meticulously straightening each cardboard box of envelopes before sending them along a rhythmically clicking conveyor belt.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is presenting parts of the West with some of the biggest challenges since World War II. Long-held assumptions about access to cheap energy have been turned upside down.

Inflation is squeezing consumers, who are already worried about a possible global recession, just as energy prices are skyrocketing with the looming arrival of winter in Europe and North America. Governments scrambling to shore up energy supplies are asking individuals, companies, and communities for sacrifices – from shorter showers to revamped work schedules – that are unfamiliar to generations of Europeans.

In the United States, farther from the epicenter of the scarcity crisis, conservation is a much tougher sell. But high energy prices are still hitting American pocketbooks, and the convergence of challenges is galvanizing people to rethink driving habits and thermostat settings as a larger climate crisis looms in the background.

From northern France to the heart of Germany to a corner of New England, a new ethos around personal and civic responsibility is evolving as citizens brace for the onslaught of winter amid global shortages and a brutal war.

“Countries and individuals start to react in different ways under stress,” says Ian Lesser, executive director of the Brussels office of the German Marshall Fund.

The immediacy of the energy, inflation, and security crises is much more striking in Europe. It is drawing out values more closely aligned with environmental conservation than in America, where people default more to individual freedoms and risk-taking. But Americans are reacting, too, in ways that are both different from and similar to Europeans.

“Conflict, wars, rationing, things simply not being available – that’s something that’s essentially alien to the American historical experience,” says Dr. Lesser.

But, he adds, with the pandemic as well as the current challenge of energy insecurity and high inflation, “it may be that America and Europe actually converge in their approaches over time.”

In France, people will have to get used to not washing their hands with hot water in public restrooms. It simply won’t be available anymore.

The government of President Emmanuel Macron is calling for a series of “sobriety measures” as part of a plan to reduce the nation’s energy bill by 10% over two years. The strategy is multifaceted, depending on the actions of policymakers, politicians, and citizens alike.

Besides turning off the hot spigot in public bathrooms, the federal government has asked residents to keep their home thermostats at 19 degrees Celsius, or 66 degrees Fahrenheit. Gymnasiums will replace regular lighting with energy-efficient LED bulbs.

In Strasbourg, officials say they intend to reduce the electricity bill of their world-renowned annual Christmas market by 10% as well. They will take down some lighting, recycle natural waste, and close the market one hour early each night.

This partial blackout has alarmed French server Constance Ernwein. The restaurant where she works, tucked into a winding twist of cobblestone in Strasbourg, serves the Alsatian specialty tarte flambé, a pizzalike pastry drenched in ham and cream. She worries about walking home in the dark, now that public lighting is being reduced.

Like several cities in France, Strasbourg – the seat of the European Parliament – decided in late October to shut off most streetlights overnight to save energy. City officials hope that by limiting lighting from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m., they can reduce the energy bill by 10% in 2023.

“So there’s almost no light on my way home,” says Ms. Ernwein, as she rushes around wooden tables on a recent evening, a cream-colored headband keeping hair out of her face. “It’s lots of little streets.”

At least she can call her boyfriend to accompany her home. But that doesn’t solve her other worry: the home electricity bill.

Since working to pivot almost overnight from dependence on Russian fossil fuels, Europe has been scrambling to shore up alternative supplies and protect consumers from price hikes.

The good news is that, heading into winter, gas reserves across Europe are largely full, with governments reaching targets ahead of time, according to Gas Infrastructure Europe, an industry group. Analysts don’t expect the need for rationing as was once feared, in part because late fall weather across Europe was unseasonably warm.

Yet as the Northern Hemisphere heads into the coldest, darkest months, prices are likely to continue to rise, and it’s unclear government help will come quickly enough, much less last as long as it needs to.

Electricity prices in October compared with the year before have increased dramatically, ranging from double in Berlin to triple in Rome. Meanwhile, natural gas prices for households have gone up 300% in Vienna, Rome, and Berlin, according to the Household Energy Price Index. And with half of its nuclear power supply shut off, France is bracing itself for possible blackouts this winter.

Like many other European governments, including in Italy and Spain, President Macron’s administration announced caps on power and gas prices. Increases will be limited to 15% for households starting in January – a measure that will cost the state €16 billion ($16.7 billion) but will prevent individual energy bills from doubling.

“We are determined ... to act, adapt, and protect the French people and our economy,” French Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne said in September.

For households particularly hard-hit, government assistance is unlikely to offset the full cost of increases this winter. So Ms. Ernwein, for one, is taking shorter showers and throwing a duvet around her shoulders while keeping the thermostat low at home.

She isn’t alone. Philip Golub, a professor of political science at the American University of Paris, says that many French are being asked to make sacrifices. “A large number of people who represent the middle and lower classes are in a very vulnerable situation due to the energy crisis,” he says.

Class struggle has always been a central element of the modern French state. Yet after World War II and the institutionalization of state welfare, a greater sense of social cohesion and economic security took hold. The erosion of the welfare system over the past four decades, Dr. Golub says, is the main source of broad social grievances today. And the inflation and energy crises may exacerbate those tensions.

While Europe has rallied around Ukraine in the name of democracy and sovereignty, the solidarity might not be enough to stave off a sense of injustice at home over time, Dr. Golub says. Already, France was rocked by general strikes in October and November, with workers demanding higher wages. Purchasing power in the country also fell to its lowest level in 30 years in the first six months of 2022.

“Solidarity and social cohesiveness, the notion of a common struggle, depends and requires that there be justice in the distribution of the sacrifices and costs,” Dr. Golub says.

Germany, too, is trying to rally its citizens to help cope with a looming winter of discontent.

When planning began in Berlin for the city’s 2022 Festival of Lights and its 3 million visitors, energy was cheap and Russia hadn’t yet invaded Ukraine. But as the event approached its 18th annual go-round this October, it became clear that an immense public display of wintertime energy consumption would send the wrong signal.

“Business as usual is not the right thing to do,” says Birgit Zander, founder and CEO of the festival. “It was our responsibility to try something new. It was our duty to put everything into the effort to save energy.”

Festival organizers abandoned concepts that were months in the making. They connected with artists who incorporated LED lights in their works, cut an hour off opening times, and reduced the number of locations participating in activities. Instead of fully illuminating the ever-popular Berlin Cathedral, organizers flew lighted birdlike paragliders overhead. For 10 nights, the sky was transformed into an aerial aquarium and aviary. In all, the festival’s innovations slashed energy consumption 75% over 2021.

“It wasn’t easy, but in the end, it was possible,” says Ms. Zander. “This new edition is responsible, sustainable, and innovative. We brought something beautiful, enjoyable, and free to the people – but with a high level of responsibility.”

The German government, like the French, is trying to tap into a public sense of duty as winter arrives. Berlin has launched a series of ad campaigns encouraging the public to cut consumption. German economy and energy minister Robert Habeck has urged companies to allow employees to work from home one or two days a week to eliminate commutes.

“Every kilometer not driven is a contribution to making it easier to get away from Russian energy supplies,” said Mr. Habeck in October. No recommendation is too small: The energy minister has suggested people defrost their freezers to run more efficiently and install low-flow shower heads.

Governments are taking their own steps to curb energy use as well. Federal lawmakers passed a set of ordinances mandating energy-saving steps for public buildings and companies. The Berlin Senate, the executive body that oversees the city, is trying to cut public sector consumption by 10%. It is nudging libraries, courthouses, and government buildings to lower temperatures, idle hot water heaters, turn off outdoor lights, and switch to more efficient bulbs.

As the winter solstice nears, two of the city’s most iconic sites – the Berlin TV Tower, built by East Germany in the 1960s as a symbol of communist power, and the Brandenburg Gate – will remain unlit.

“It is a matter of credibility for politicians if they make a visible effort to set good examples in their own area,” says Bettina Jarasch, deputy mayor of Berlin and senator of environmental affairs. “This is the only way to appeal to a sense of personal responsibility for citizens.”

The conservation efforts appear to be working. Gas consumption in Germany in October was down by roughly half for households and small businesses over the same period a year ago.

At the same time, Germany, as the European Union’s wealthiest country, is using its massive borrowing power to subsidize its own industries and citizens to shield them from rising energy costs. The federal government will pick up the monthly gas bill in December for all households and most enterprises in the country, as well as offer further financial assistance over the next 14 to 16 months. The price tag to the state: roughly €91 billion ($95 billion).

Rising utility bills are threatening many of Germany’s small- to medium-sized enterprises, the backbone of the economy, with layoffs and bankruptcies. While the government aid will help, it could have a deleterious effect: It insulates people and businesses from the rising prices that might spur conservation.

“Conversations about energy are very uncomfortable because people want comfort and quality of life; they don’t want to think about coal,” says Marine Cornelis, an energy policy consultant based in Turin, Italy. “But when you do start thinking about energy as something you have to pay for, and it’s expensive, then you save energy. That’s not really happening with the subsidies.”

On the other hand, there are limits to how much people want to sacrifice. Some Germans are already chafing at a few conservation suggestions. In August, Winfried Kretschmann, a Green Party politician and president of the German state Baden-Württemberg, threw out this idea to cut energy usage: “You don’t have to shower all the time. The washcloth is also a useful invention.”

He was widely ridiculed online.

This was precisely the kind of tart response that hampered another Western leader in his conservation efforts in a different era. Two weeks after being sworn in as U.S. president in 1977, Jimmy Carter donned a beige cardigan in the White House during a wintertime fireside chat as a symbolic gesture to encourage a more parsimonious ethos.

He had plenty of rationale for making the plea, coming after the Arab oil embargo and a decade of rampant inflation.

But many Americans refused to hear the message – a cultural inclination that is as much a force today as it was 45 years ago.

Back then, the U.S. faced serious shortages. Today the country is a net energy exporter: It doesn’t face the tight supplies that Europe does, or the direct security threat posed by Russia.

Yet many of the American traits – a penchant for big cars, a sense of individualism, a reluctance to accept limits – remain, which helps explain why the conservation efforts in Europe may not be widely embraced here.

“To live in a colder house or to have less electricity or less enjoyment of life, to get into small cars or to drive at slower speeds, is politically unpopular,” says Kevin Book, co-founder of ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington, D.C.-based research firm that examines energy trends and comparative political outcomes. “We like using energy freely. It’s part of our national identity.”

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Marshall Plan, the U.S.-funded effort to help rebuild Western Europe after World War II. And while European society is far removed from an era of rationing and hardship, the experience generations ago still shapes its value systems today.

The EU tends to be more cautious and risk-averse than the U.S., says Dr. Lesser in Brussels. Its lack of a startup culture can hold the Continent back. But its embrace of a more collective approach and willingness to confront long-term problems have their benefits. Environmental concerns, for instance, have been part of mainstream discourse longer in Europe than they have been in the U.S. With inflation, energy concerns, and the pandemic, says Dr. Lesser, Europeans are asking more fundamental questions about how much growth is really necessary in society. Conversely, in the U.S., growth and prosperity are often taken for granted as a starting point, he says.

Yet Americans are hardly immune to sacrificing for the collective good in a time of hardship.

Inside a white 18th-century church in Hanover, New Hampshire, Linda Gray bounces from station to station, monitoring teams of volunteers as they wrap wooden frames in double-sided tape.

She approaches the far corner of the reception room at the Church of Christ, where two sweater-clad women are heating sheets of plastic wrap with hair dryers as they’re stretched over the frames. They will be used as window inserts to help eliminate costly winter drafts.

“In the back room we have coffee and tea,” Ms. Gray tells them cheerfully.

As a member of a local energy committee in Norwich, Vermont, she, along with others, organized this event across the Connecticut River to help New Englanders with poorly insulated homes cut their utility bills.

Across the U.S., average costs for home heating are expected to rise 17% this winter, according to the National Energy Assistance Directors Association. New England is among the nation’s regions most vulnerable to global energy volatility because of its dependence on foreign imports. For the most destitute people, winter could represent more than an annoyance at the gas pump.

“I am concerned that, as we get deeper into the colder months, people may have to make a choice between buying groceries or heating their homes,” says Tracy Hutchins, executive director of the Upper Valley Business Alliance, a regional chamber of commerce in Hanover.

The workshop on this day dates back to a legacy put in place across New England nearly a half-century ago. In Vermont, local officials established municipal energy coordinators to help deal with the aftermath of the 1973 Arab oil embargo.

Today that network has evolved into hundreds of energy committees operating across New England.

Their work, now driven largely by the climate crisis, can feel small against the magnitude of the challenge. But Ms. Gray thinks of her role as a “modest multiplier.”

“In a house that hasn’t done any of this, this is a help, a way for us to start talking to them and start getting them interested in it,” she says.

Their solutions are in high demand today, since some New Englanders have already seen energy bills spike more than 50%. Local energy committees have been helping libraries install heat pumps and low-income families weatherize their homes.

The workshop today is a partnership between local energy leaders and the Maine-based nonprofit WindowDressers, which has distributed more than 48,000 inserts to New England homes since 2010.

For Geoff Martin, a regional energy coordinator in Vermont, the work is not just about utility bills or the coming winter.

“Climate change is one of the biggest issues that we’re facing, and ultimately is going to impact the poorest and most vulnerable the most. ... If towns are able to help their community members lower their energy use and lower their emissions, I think that just builds momentum, and hopefully it has an impact eventually on a global scale,” he says.

Building momentum is the aspiration back in Forest-sur-Marque.

Pocheco, the envelope company, normally spends around €100,000 annually on energy, but this year its utility bills could triple. Changing some work shifts to overnight, when electricity is cheaper, and shutting off machines completely for several days in January during annual price spikes will help trim costs.

Pocheco President Emmanuel Druon has said the overnights shifts are only temporary, but align with longer-term efforts. Mr. Druon, who took over from his father 25 years ago, has based his company on the principles of “ecolonomy”– the idea that being ecologically friendly actually makes companies more economically resilient.

Solar panels cover the top of the main building, which is constructed of larch – a wood that is naturally resistant to parasites and does not need to be treated with harsh products. A rooftop garden lines the annex and continuously collects rainwater, which is used in the bathrooms and to wash the machines and floors.

These efforts aren’t just a passion project, says Mr. Druon, but a way to stay ahead of potential challenges and future crises.

“I’m not optimistic or pessimistic [ahead of the energy crisis], but we are prepared. ... I can’t say we’re completely sheltered from the crisis, but with all of our knowledge, we’ve put together all possible measures to weather the storm.”

That wouldn’t be possible without the sacrifices taken by workers such as Mr. Pantalacci, who discussed the decision to change schedules at length with his wife before finally committing to the 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. shift.

“At first, it was a little strange,” he says. “It’s always a little weird to leave the house in the dark, but once I get here, I forget about it.”

His wife works a different schedule, starting at 6 a.m., so they only overlap during the late afternoon and early evening hours. “Each of us has had to find our footing. But we’ve found a balance,” says Mr. Pantalacci. “There’s always something we can do to help.”

The Explainer

Another year, another US border crisis. Could 2023 be different?

U.S. immigration reform has been needed for a generation. But amid rancor over the border, immigration experts point to Ukrainian refugees as an example of how policy can be successfully adapted for modern times. They point to it, right now, as an isolated example.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Border issues are increasingly complex, and the U.S. immigration system remains outdated and under-resourced.

More fundamental changes are possible – and needed – analysts say, pointing to recent programs focused on Ukrainian and Venezuelan migrants. But there needs to be popular and political will as well.

The Biden administration has been trying to bolster the asylum system.

This spring, the Department of Homeland Security began piloting a new asylum officer processing rule intended to resolve asylum requests within months instead of years. Last year, the Biden administration launched a new Dedicated Docket in immigration courts for families seeking asylum at the southwest border.

The program has sped up asylum cases, but fairness has suffered, according to a report from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University. Only about one-third of families had representation in their cases, while about two-thirds of families never filed asylum applications before their cases were closed.

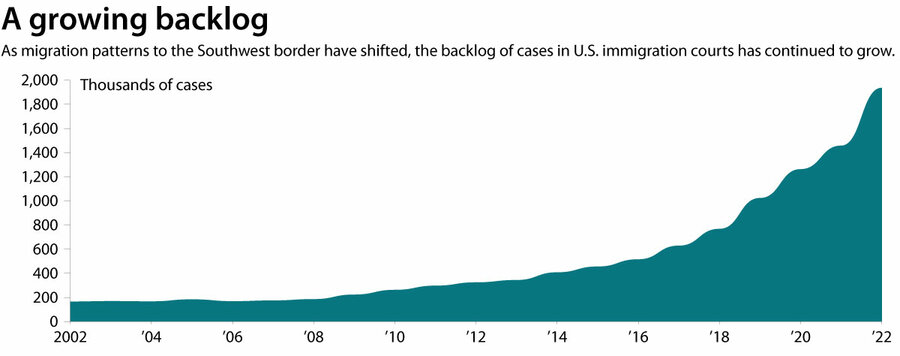

Meanwhile, the case backlog in immigration courts has continued to grow.

“There [is] no quick fix for the country’s asylum backlog,” said the TRAC report. “The evidence suggests that the United States can implement schemes to make asylum cases fast or make asylum cases fair, but not both.”

Another year, another US border crisis. Could 2023 be different?

Heading into the new year, the Biden administration’s actions at the southwest border have come under intense scrutiny.

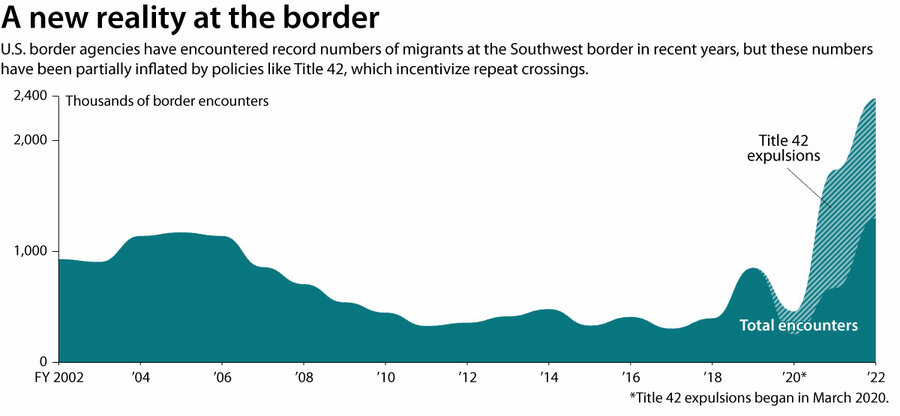

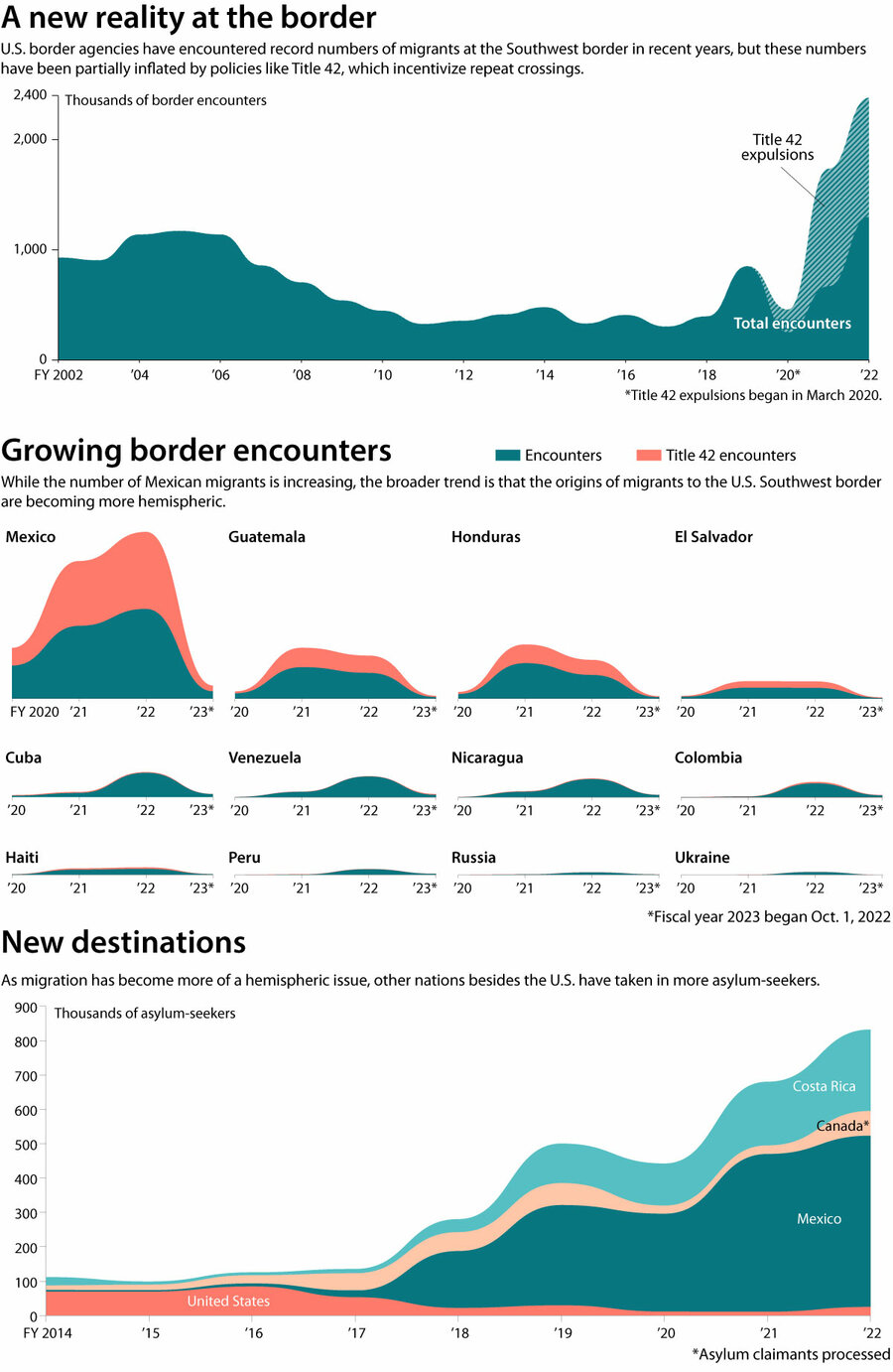

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has been reporting record numbers of encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border, as the COVID-19 pandemic and other global crises have compounded the challenges facing a U.S. immigration system ill-equipped to process large numbers of asylum-seekers.

After criticizing the Trump administration’s approach to these challenges as inhumane and ineffective – including the forced separation of families and the rapid expulsion of migrants under a pandemic-era public health order – the Biden administration has only recently begun implementing a different approach. And critics say the approach has only been different in parts.

Court battles have drawn out some of these policy changes, and while some Trump-era programs have been ended, others have been maintained – and even expanded. Chronic issues, like the growing backlog of cases in immigration courts, persist. Partnerships, primarily between the United States and Mexico, are strengthening, while strained ties with other Latin American nations hamper cooperation.

In sum, the Biden administration is caught between migration patterns that are increasingly hemispheric and organized, and domestic political head winds focused on border security. As border issues grow more complex, the U.S. immigration system remains outdated and under-resourced.

More fundamental changes are possible – and needed – analysts say, pointing to recent programs focused on Ukrainian and Venezuelan migrants. But there needs to be popular and political will as well.

“The Biden administration is taking some steps to soften the harshest edges of the Trump administration’s southwest border policies. But at the end of the day, they’re doing so at a very slow pace,” says César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, a criminal and immigration law professor at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law.

The administration “has shown us they have the tools available, and have the capacity, to respond quickly and effectively,” he adds. “It is possible under existing immigration law and existing resources ... to respond to the many humanitarian crises that are raging throughout the hemisphere.”

Title 42 ends next week. What happens next?

The Biden administration has spent years working to reunite families separated at the U.S. border between 2017 and 2021. Since August – after a legal battle that went up to the U.S. Supreme Court – it has been winding down the “Remain in Mexico” program, which required asylum-seekers to stay outside the country while their cases were pending.

But the White House has retained – and expanded – another hallmark Trump policy: the Title 42 program, a public health order that allows officials to automatically expel unauthorized migrants from certain countries without immigration charges. The lack of charges has resulted in many migrants making repeated attempts to enter the country, analysts say – particularly among Mexican migrants – which has contributed to record numbers of “encounters” at the southwest border in the past two years.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Next week, however, Title 42 will also end after a federal judge struck down the policy in November. The Biden administration is appealing, but how it handles migrant flows in the aftermath will be closely scrutinized by its political opposition.

Republicans, who will take control of the House of Representatives in January, have said border security will be a top legislative priority in the new year. They criticize, in particular, Alejandro Mayorkas, head of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and his handling of border issues, and may attempt to impeach him next year. Secretary Mayorkas, meanwhile, forced out the head of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Chris Magnus, last month.

A bipartisan push for an immigration reform bill is underway in the U.S. Senate, meanwhile – a compromise bill that would reportedly include a pathway to citizenship for around 2 million “Dreamers,” or unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. as children – while beefing up border security and implementing a Title 42-style policy.

Conservatives have criticized the potential legislation as a continuation of the Biden administration’s insufficient handling of the border.

“The Biden Administration is responsible for the worst non-stop border crisis in American history and should not be rewarded with an inadequate and deeply flawed immigration deal from Congress,” said Greg Sindelar, CEO of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, in a press release last week.

“It is time to focus on making sure that all the needed asylum system fixes, enforcement capacity and mechanisms, including the still incomplete infrastructure and technology at and between ports of entry, are in place and fully functioning,” he added.

The political reality is that “there’s a need for the Biden administration to [show] they’re doing something at the border, even when that’s not tackling the root of what’s happening,” says Ariel Ruiz Soto, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute.

“Any or every change that’s perceived to increase numbers [of encounters] is perceived as the border being insecure,” he adds.

How have migration patterns to the U.S. changed?

As has been the case for decades, irregular migration to the U.S. continues to be driven by a combination of “pull factors” toward America and “push factors” away from native countries. And those factors continue to evolve.

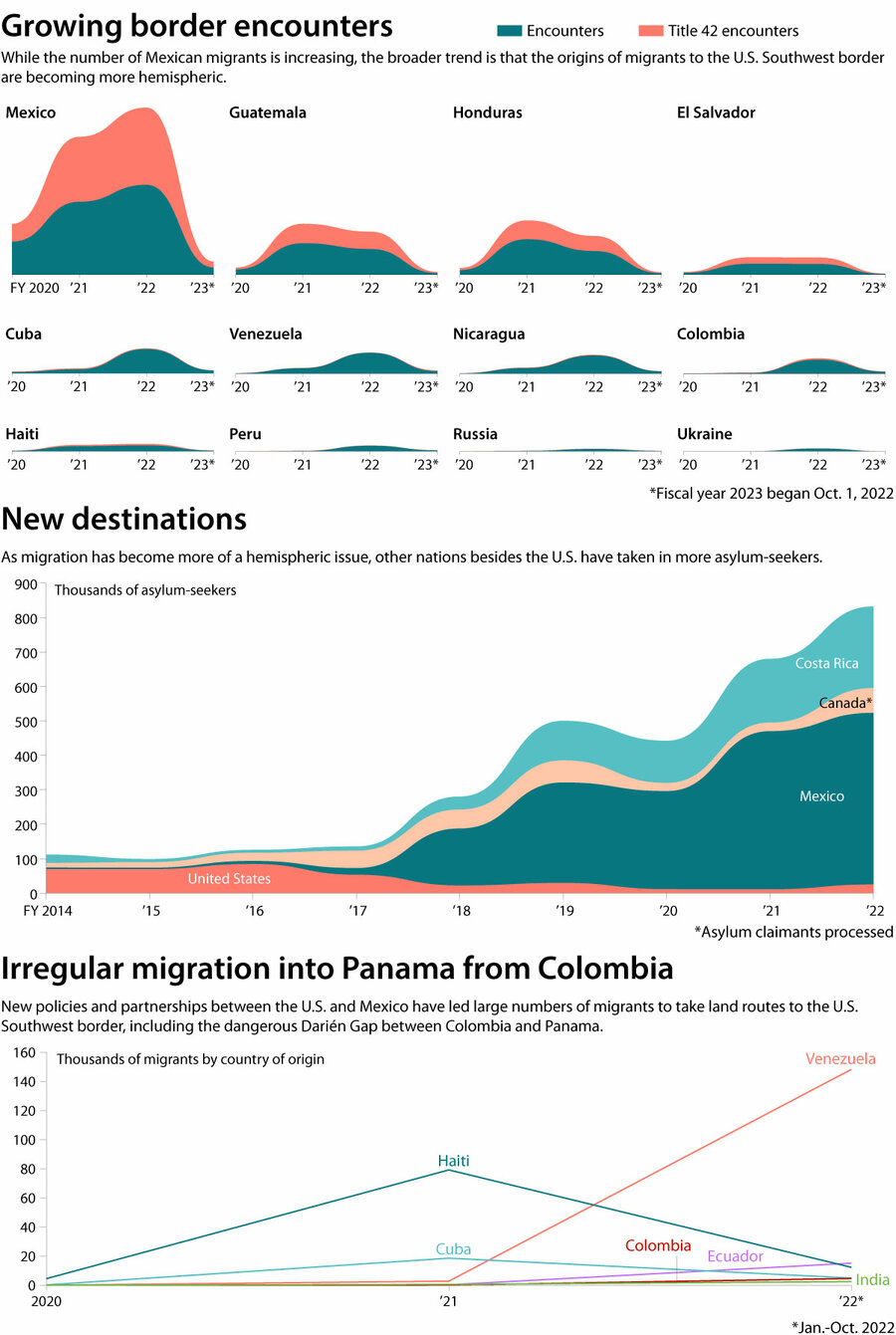

Whereas migrants were once predominantly adult men from Mexico entering unlawfully – the population that U.S. immigration infrastructure is arguably still best designed for – the mid-2010s brought larger numbers of unaccompanied children and families seeking asylum from Central America. Now, families and individuals from across the hemisphere are journeying to the U.S. to request asylum. International law requires that the U.S. take in asylum-seekers and adjudicate their claims.

Driven by political, social, and economic crises, and facilitated by sophisticated trafficking networks, migration in 2022 is breaking records across the continent – from the U.S.-Mexico border to the Darién Gap jungle separating Colombia and Panama.

“It’s not that political repression just happened in 2021, but that people began to see it wasn’t going to change,” says Mr. Ruiz Soto.

“People began to lose hope that in these countries [things were] going to change.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, UNHCR, Migración Panamá

As irregular migration becomes more hemispheric, experts say, government management of migration needs to become more hemispheric. Countries like Mexico, Canada, and Costa Rica have been accepting more asylum-seekers in recent years (the U.S., with a strict refugee admissions cap, is lagging in this regard).

But the hemisphere lacks the infrastructure and resources to handle this volume of migration – at least in the way it’s traditionally approached the issue.

“Our priorities for so long have been control, deportation, and containment,” says Mr. Ruiz Soto. “Until we make that more balanced, we’re going to continue to see that these countries – including the U.S. – don’t have enough capacity to meet the demand.”

In other words, the hemisphere can’t police its way out of migration like this, experts say. Partnerships must be formed, and a regular, legal migration system created.

That shift has already begun, but the results have been mixed.

Frosty diplomatic ties with countries like Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua make it difficult for DHS to deport migrants from those countries. So the U.S. and Mexican governments have worked especially closely together to manage the northward flow of Venezuelan migrants.

In January, at the request of the U.S. government, Mexico imposed a new visa requirement on Venezuelans entering the country. And in October, the two countries reached an agreement to expand Title 42 – allowing the U.S. to expel Venezuelans into Mexico – and create a new parole program allowing up to 24,000 Venezuelans temporary legal status in the U.S.

Judging by the continued flow of migrants, particularly Venezuelans, crossing the Darién Gap and America’s southwest border this year, these policies don’t seem to have had the desired effect.

“Today, U.S. border policy isn’t just playing out at the U.S. border; it’s playing out across the hemisphere,” says Professor García Hernández.

“We’ve [not] stopped migration out of South America, but we have made it more dangerous,” he adds. “That’s the future if policies emanating from Washington don’t change.”

Can U.S. slow down traffic, or process it faster?

Illegal – and thus dangerous – migration can be limited, conservatives argue, with tougher border policies.

“The key is always reducing the incentives for illegal immigrants,” says Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a nonprofit think tank that advocates for limited immigration.

“There’s a limit to what the U.S. can do to address root causes of immigration, which is why we need more muscular immigration enforcement,” he adds. “Once they do that, the flow will start abating, because you’ll be sending the message that the risk will not be worth it.”

The Biden administration has been focusing its reforms elsewhere, in particular bolstering an under-resourced asylum system.

This spring, DHS began piloting a new asylum officer processing rule intended to resolve asylum requests within months instead of years. Last year, the Biden administration launched a new Dedicated Docket in immigration courts for families seeking asylum at the southwest border, the goal being “to decide cases expeditiously, [while] fairness will not be compromised.”

The program has helped speed up asylum cases, but fairness has suffered, according to a report from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University. Only about one-third of families had representation in their cases, while about two-thirds of families never filed asylum applications before their cases were closed.

Meanwhile, the case backlog in immigration courts has continued to grow.

“There [is] no quick fix for the country’s asylum backlog,” said the TRAC report. “The evidence suggests that the United States can implement schemes to make asylum cases fast or make asylum cases fair, but not both.”

Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University

What about the Ukrainians?

Where the Biden administration has had success, experts say, is in how it quickly adapted the U.S. immigration system in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Within months, DHS announced the Uniting for Ukraine program: a “streamlined process” with “no numerical limits,” in which Ukrainians, with the help of private citizen sponsors, can apply for humanitarian parole into the U.S.

Over 100,000 Ukrainians have entered or been approved to enter the U.S. through the program so far, according to an August report from the Niskanen Center. (Through its official refugee resettlement program, the U.S. admitted just over 2,500 refugees in fiscal year 2022.)

“They’ve dealt with a community that was in dire need,” says Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, an associate professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

“That’s exactly what they can do [with other communities] if there is a commitment to do that,” she adds.

Indeed, immigration experts point to Uniting for Ukraine as an example of how U.S. immigration policy can be successfully adapted for modern times. They point to it, right now, as an isolated example.

“That’s evidence that when the administration takes seriously the humanitarian call that President Biden issued to immigration officials, it does actually have the ability, the resources, and the legal wiggle room to adopt a very humanitarian approach,” says Professor García Hernández.

“The question then becomes, why limit it to that crisis?”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, UNHCR

Gulf leaders find new partner in China, challenging US dominance

For decades Washington has been the unquestioned patron and protector of its allies in the Gulf. Now the Gulf states want to diversify their ties: Enter China.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The United States is no longer the only superpower active in the Arab Gulf.

That was the message from a weekend summit in Saudi Arabia between Arab leaders and Chinese President Xi Jinping. Participants called it a “milestone,” cementing political ties and paving the way for a larger Chinese role in Arab economies and security.

This will not go down well in Washington. A senior U.S. official warned at a regional meeting last month that “raising the ceiling too much with Beijing will lower the ceiling with the U.S.”

But Saudi Arabia and other Gulf leaders are worried that the United States cannot offer a reliable partnership; Washington is engaged in a “pivot to Asia” and has a habit of raising human rights concerns. China’s one-party system and autocratic rule seem to offer the kind of constancy and predictability that Gulf sheikhs prefer.

They are not replacing the United States as the region’s strategic partner or exchanging their commitment to a U.S.-led international order for loyalty to China. But Beijing, they say, can fill gaps that Washington is leaving.

“With China you know where you stand,” says one Saudi official. “Not four years of being allies and then four years of being called a pariah.”

Gulf leaders find new partner in China, challenging US dominance

The United States is no longer the sole superpower active in the Arab Gulf.

This was the message from a weekend summit in Saudi Arabia between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Arab leaders. Participants called it a “milestone,” cementing political ties and paving the way for a larger Chinese role in Arab economies and security.

The Arab embrace of a more assertive China is a response both to criticism from U.S. President Biden’s administration and to Washington’s strategic pivot away from the Middle East toward Asia and Europe. More than that, what some observers are calling an “Arab-China renaissance” represents a bid by Gulf leaders for something they say the United States is failing to provide: a reliable partnership that won’t waver with the political winds.

“With China you know where you stand,” says one Saudi official who preferred to remain anonymous. “Not four years of being allies then four years of being called a pariah.”

Saudi Arabia’s very public welcome of President Xi, offering pomp, pageantry, and three regional summits, is likely to spark unease in Washington. Only last month, U.S. Undersecretary for Defense Colin Kahl warned in an address to regional policymakers that cooperation with China, “once it crosses a certain threshold … creates security threats for us.”

“Raising the ceiling too much with Beijing will lower the ceiling with the U.S.,” he cautioned at the Manama Dialogue conference in Bahrain, “not for punitive reasons but because of our interests.”

“Unprecedented” expansion of ties

In a sign of warming ties that have been years in the making, Saudi Arabia and China signed 34 agreements, including a “comprehensive strategic partnership agreement,” in which Beijing and Riyadh pledged support and solidarity for each other’s core national interests, opening the door to security cooperation.

Individually, Gulf states have been quietly building economic and diplomatic ties with China for the past two decades. China is Saudi Arabia’s largest trade partner and oil market, for example. But they have been careful not to upset their strategic balance with Washington.

Now, after enjoying a purely economic relationship, Saudi Arabia has accelerated strategic cooperation between China, the Gulf, and the wider Arab region, using its sway as the only country that can gather all Arab leaders on two weeks’ notice.

Though the summits did not go so far as to replace the United States as the region’s strategic partner, nor exchange Arab leaders’ commitment to a U.S.-led international order for a Chinese one, “this was an expansion of ties with China in every direction. It was unprecedented,” says Mohammed Alyahya, a Saudi analyst at Harvard University’s Belfer Center.

Underlying the shift is a sense, gaining ground in Riyadh, that the United States is a “sometimes partner,” friendly only when it needs more oil or Saudi political support in a crisis.

China, with its one-party system and autocratic rule, seems to offer the kind of constancy and predictability that Gulf sheikhs prefer. It is a constancy, they feel, that stands in stark contrast to America’s shifting foreign policy over the past decade.

Gulf and Saudi officials point to Washington’s multiple “pivots” away from the region – deepening a sense that America’s security umbrella is unreliable.

They also resent what they see as U.S. opportunism. Though Mr. Biden had said while campaigning for the presidency that he would make Saudi Arabia “a pariah” because of its human rights record, he sought to mend fences in the face of an energy crisis last summer. Gulf officials also point to the United States’ lack of interest in the threat of Iranian drones striking critical Saudi Arabian oil facilities in 2018, compared to American concern now with Russia’s use of Iranian drones in Ukraine.

More mutual understanding

Beyond investment deals, the weekend summits saw Beijing and Arab states converge on geopolitical issues, feeding a desire by Gulf states to be seen as more than oil spigots and arms markets.

A summit of 20 Arab leaders and Mr. Xi, hosted by the Saudi crown prince on Friday, which Mr. Xi called a “defining event in the history of Chinese-Arab relations,” agreed on a 24-point declaration of commitment to intensify Arab-Chinese cooperation on each other’s “core interests.”

These included committing to “non-interference” in internal affairs, supporting China’s policies in Hong Kong, “strengthen[ing] cooperation to ensure the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear program,” ensuring Tehran adheres to “the principles of good neighborliness,” and “reject[ing] of independence for Taiwan in all its forms” from the Arab states.

The leaders also found common ground on an issue that divides Gulf states and the United States – human rights.

In their summit statement, China and Arab states insisted on “human rights based on equality and mutual respect” and stressed their strong “rejection of the politicization of human rights issues and their use as a tool to exercise pressure on countries and to interfere in their internal affairs.”

Policymakers in Washington have already flagged growing Chinese influence in the Arab Gulf as a security, cyber security, and surveillance threat to America’s military and defense; a deal between Saudi Arabia and Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei will deepen those concerns.

Amid U.S. worries, Saudi observers say Riyadh is determined to seize the opportunity of an assertive China’s interest in the region to cement long-term Chinese investment in Gulf infrastructure, robotics, and nuclear energy.

“Saudi Arabia and Arab states are trying to adapt and balance between these two superpowers and this will be no easy task,” says Saudi political scientist Hesham Alghannam.

“But, at the end of the day, you need to work with China. Needs on both sides are driving increased cooperation, and it is serious this time,” he adds.

Q&A

Margaret Sullivan: ‘There is a moral component to a life in journalism’

As guardians of democracy, journalists have a constitutionally protected role to play in society, says veteran journalist Margaret Sullivan. She urges news organizations to recommit to their core purpose: serving the public.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Margaret Sullivan began her storied career in journalism in the late 1970s, 7 in 10 Americans said they trusted the news, she reports. Coming of age just after the era of Watergate, she describes how exciting it was to work in a newsroom, a job that was not only enjoyable but also a vital part of civic life.

In her new memoir, “Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life,” Ms. Sullivan tells a very personal story about watching as her profession lost the public’s trust – today only 1 in 3 Americans say they trust the news. She draws on her experiences to trace some of the missteps that newspapers made as the digital age unfolded, disrupting both its business models and the flow of information.

Ms. Sullivan, one of the first women to lead a major regional newspaper, had a ringside seat from which to observe the news industry, first as the public editor at The New York Times and later as media columnist at The Washington Post. Now, she sees her role as “trying to call journalists to their higher purposes,” she says.

Despite the challenges facing the media, Ms. Sullivan still encourages people to go into the profession. “There is a moral component to a life in journalism,” she says. “I still think it’s a great way to spend your life.”

Margaret Sullivan: ‘There is a moral component to a life in journalism’

When Margaret Sullivan began her storied career in journalism in the late 1970s, 7 in 10 Americans said they trusted the news, she reports. Coming of age just after the era of Watergate, she describes how exciting it was to work in a newsroom, a job that was not only enjoyable but also a vital part of civic life, especially on a local level. Local newspapers were financially successful then, and journalism offered a viable career path. “As a bonus, it struck me as exceedingly cool,” she says.

In her new memoir, “Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life,” Ms. Sullivan tells a very personal story about watching as her profession lost the public’s trust – today only 1 in 3 Americans say they trust the news. She draws on her experiences to trace some of the missteps that newspapers made as the digital age unfolded, disrupting both its business models and the flow of information.

Covering the nitty-gritty of local civic life for over three decades at The Buffalo News, she became one of the first women to lead a major regional newspaper. As the public editor at The New York Times, she was tasked to investigate and critique the organization’s reporting from the inside. And more recently, Ms. Sullivan was the media columnist for The Washington Post, where she continued to think and write about the broader issues confronting journalism.

“Much as I love and value my craft, I’m worried,” she writes at the outset. “I am sickened at the damage done by hyperpartisan media and distressed about the failures of the reality-based press. We’re in deep trouble. How did we Americans become trapped in this thicket of lies, mistrust, and division? Can we slash our way out?”

A manifesto as much as a memoir, Ms. Sullivan’s book has some suggestions. A major theme is her call to press forward with a renewed focus on journalism’s role in a free society. “The reality-based press has to reorient itself, framing its core purpose as serving democracy,” she writes.

She spoke recently with the Monitor; the conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

What have been some of the major challenges confronting journalism over the course of your career?

I would say there are a couple different things. In the digital age – and certainly before that, although in a different way – we’ve become very oriented toward what gets the most traffic, what gets the most engagement, what gets the most clicks. A lot of it is driven by the profit motive, since most news organizations are owned by corporations, and they are profit-making entities, and so they do have to think about that stuff.

But that should not be the first thing we think about. The first thing we think about should be: “How do we serve the public?” and “How do we best play our constitutionally protected role in society?” I have seen my role in recent years as trying to call journalists to their higher purposes. We’re not here to generate clicks. We’re here to serve the public, and we’re here to play an important role in the workings of democracy.

But one of the distressing parts is the fact that it’s harder to do this. Local newspapers, which had been the engine of local news in most regions, have taken a huge hit as their business models, based on print advertising, completely disintegrated. Newsrooms have shrunk so shockingly in size. At one time, a typical regional newspaper may have had 200 or 300 people in the newsroom. And now the much more typical number is 50, 60 people. And then maybe there was a second newspaper in town, ... but it’s gone now. So you just can’t do the same job covering all the important things that are happening.

You also explore one of the traditional values of journalism, objectivity. Do you think the idea of objectivity has distorted the way many news organizations cover the news?

I would say that there’s also a couple of different ways to think about objectivity. One is that all it means is approaching a story with impartiality and with an open mind. And who can argue with that? I think that’s exactly what we should be doing.

But there’s a kind of performative “both-sides-ing” of political content, which is always really disappointing to see. So I think where objectivity gets more problematic is the way it has come to be understood by some journalists, where it often means to just report everything down the middle, and to be sort of neutral – not just impartial, but actually neutral, no matter what the subject matter is.

I don’t think that actually works well at a time when democracy itself is threatened. You can’t really cover people who oppose democratic norms and people who support democratic norms and then treat them equally. I mean, we’re just not doing our jobs if we do that.

One of the things I’ve started doing is not using the word objectivity so much, but rather trying to use words that are less argument-inducing, such as impartiality, fairness, accuracy, public spiritedness. Objectivity for a number of people, and I think particularly younger journalists, journalists of color, anybody who might find the old idea of objectivity as “the view from nowhere” – they find that very problematic because they think that we should actually stand for something.

I’ve come around to thinking that we should actually stand for something, too. And among the things we should stand for are equality under the law, press rights, decency, democratic norms. I think it’s actually remiss if we don’t stand for and stand up for these things.

You quoted the Nobel Peace Prize recipient Maria Ressa, the Filipina journalist, who said, “In the battle for facts, in a battle for truth, journalism is activism.” Do you see reporting the news as a form of activism?

When I quote her in the book, I don’t think she means, and I certainly don’t mean, carrying a picket sign or going to bat for a candidate. I don’t believe in that. But at a time when the very purpose of journalism is on the line, and when journalists are threatened and they’re disparaged and all of that, I think it makes quite a bit of sense to stand up for our craft and not be afraid to do that. So it’s not traditional activism as I see it. It’s just an awareness that we can’t be passive, and that we need to have some ideals and live by them.

What has encouraged you about the future of journalism?

If you define local news very broadly, there are some good things happening. There’s the rise of relatively new nonprofit newsrooms that are digital only. There’s growing philanthropic support for local journalism. I also think there’s more awareness now on the part of government officials, and even on part of the public, that local news, and news in general, need public support. All of these things are good and relatively new.

The workforce has also become much more diverse. You see so many talented young people of diverse backgrounds who are entering the field and bringing their own skills and knowledge and experiences to what they’re doing. I’m always very heartened by spending time with young journalists.

There is a moral component to a life in journalism, and we can embrace that. I encourage people to go into journalism. I still think it’s a great way to spend your life. And, you know, it really is a life commitment in so many ways. It’s not just a job. It’s a calling, and it’s imperfect, and we’ve screwed it up a lot. But I still think that it’s an absolute necessity that journalists be at their best.

Difference-maker

Building Men teaches students what manhood can really mean

Joe Horan felt that society’s definition of masculinity was leading him down the wrong path. So he built a positive vision of manhood not just for himself, but also for the teenagers he mentors.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ashley Kang Contributor

When Joe Horan went through a divorce he came to a startling personal realization. He had been chasing a definition of manhood that was prized by society but that felt superficial and misguided.

His life, he says, lacked substance and depth. Chasing money, women, and sports held outsize significance. He wanted to “find healing from the unhealthy messages I believed about masculinity.”

A physical education teacher at the time, Mr. Horan saw young boys around him embarking on a similar path and sought to offer a broader, more positive idea of manhood.

Through fellowship with male peers and mentors, his Building Men mentorship program has helped more than a thousand students gain perspective, work to restore self-worth, and learn to calm emotions. Kids participate in community service and mentor-led talks to help students navigate the stresses of adolescence.

A basketball component offers an accessible entry point for many students, but the program’s secret is how it dives into off-the-court issues through reinforced discussions on character.

“They sign up because they want to play basketball,” Mr. Horan says. “By the end of the year, they can better define their journey and a vision of their masculinity.”

Building Men teaches students what manhood can really mean

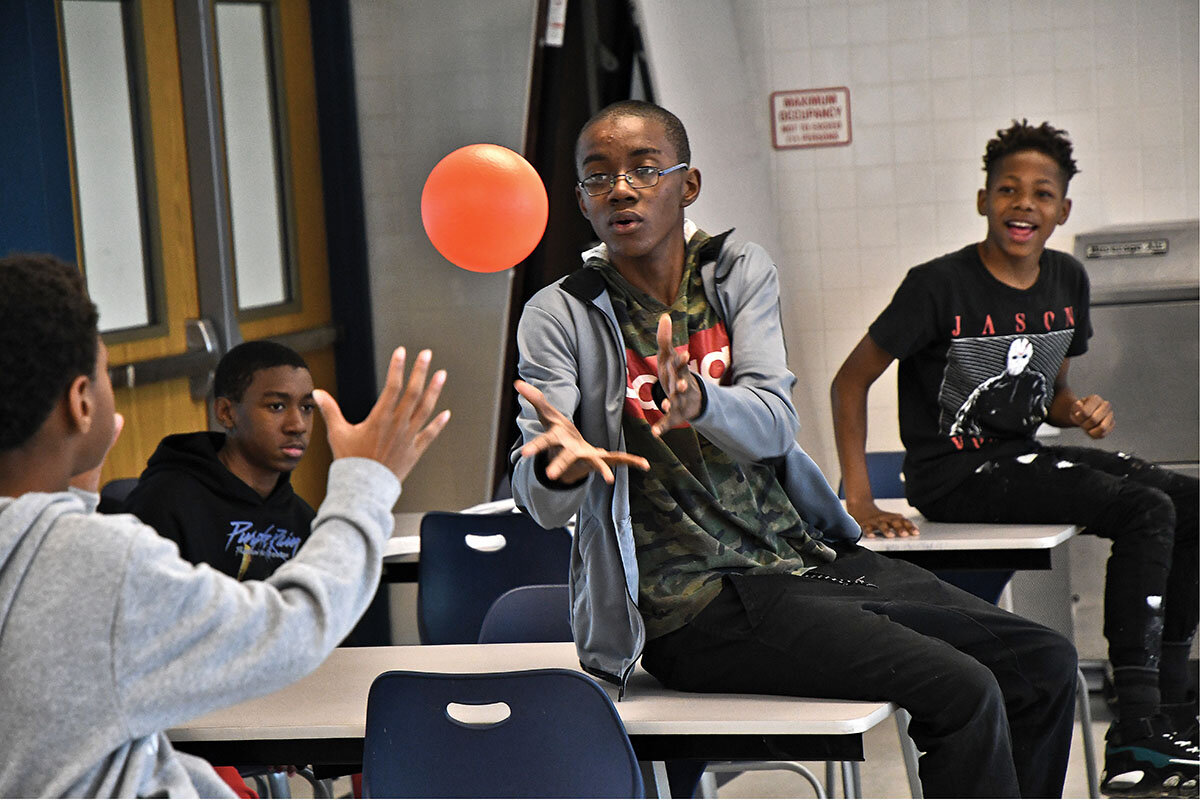

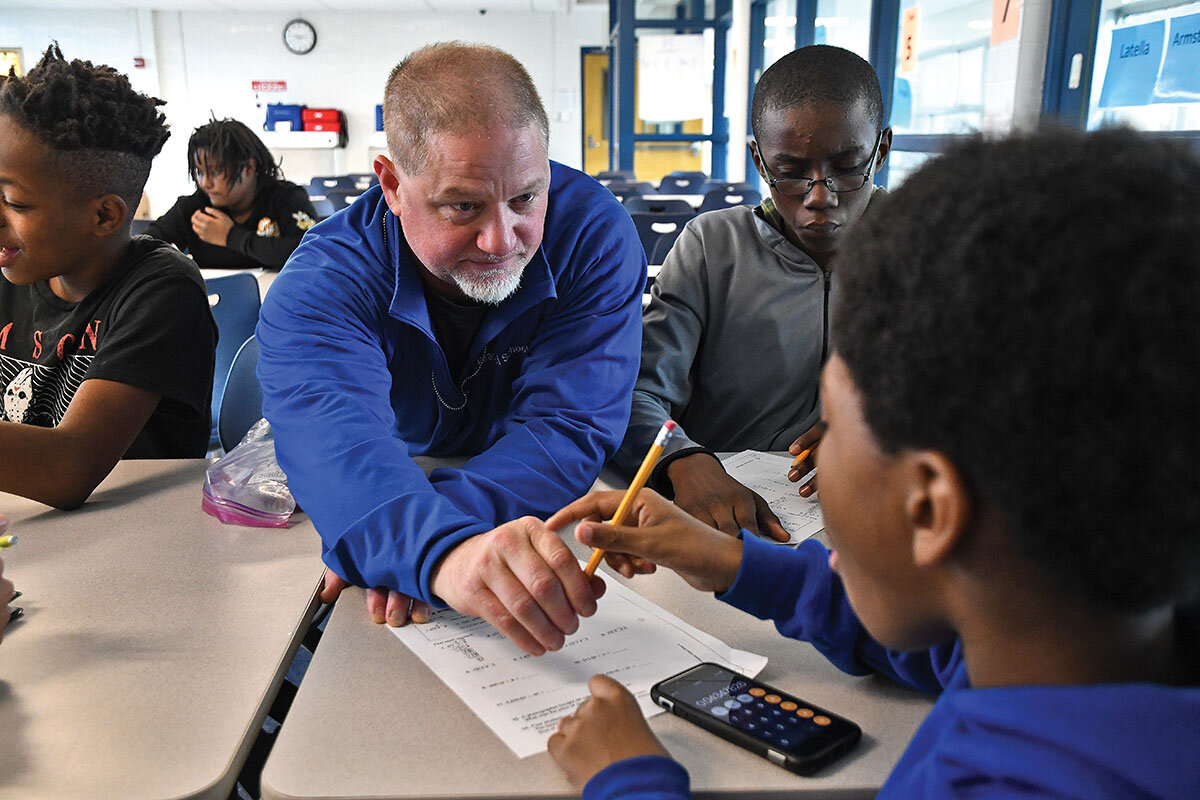

On a recent Tuesday, an after-school session for sixth- through eighth-grade boys starts in a second-floor cafeteria. Today’s lesson: attentive listening.

Samuel Colabufo, whom the young men call “Captain C,” asks the nine students to recite the Building Men creed. A few rattle it off with confidence, but many have just begun the program, an initiative of more than 15 years that has guided more than a thousand boys in the Syracuse City School District through a combination of mentorship, character building, and sports.

Eighth grader De’Kota White, who has been involved for two weeks, does not yet have the 16-line creed memorized. He learned about the program during an opening-year assembly where Building Men’s founder, Joe Horan, spoke. De’Kota wanted to join because it sounded fun.

“They do a lot and you get a chance to plays games at school,” he says. He looks forward to field trips, and by the end of the school year, attending the Rite of Passage – a culminating activity to prepare middle schoolers for their transition to high school.

Mr. Horan, who’s worked in the district for 30 years, says in an interview that the various elements of Building Men may seem small from the outside, “but aren’t small to the individuals involved.”

A personal journey

Looking back, Mr. Horan says his program evolved from a low point in his life. In 2004 as he went through a divorce, he realized he was chasing society’s definition of manhood. His life, he says, lacked substance and depth. “A desire became planted in my heart ... to find healing from the unhealthy messages I believed about masculinity,” he says.

These unhealthy messages, or what he calls the “lies of manhood,” crystallized after his sister recommended a book about Joe Ehrmann, a former NFL player and a motivational speaker. The book, “Season of Life” by Jeffrey Marx, delves into Mr. Ehrmann’s revelatory discovery of what being a man is all about. He identifies three myths: chasing money, having all the girls, and being a sports star. All three, Mr. Horan says, were also his sole sources of validation.

At that time, he worked as a middle school physical education teacher. During one class, he wondered how he could help his students avoid such traps. “These guys are going to have the same problems if someone doesn’t teach them another way,” he thought. “I asked myself, how can I challenge the boys’ thinking about the assumptions given to them by society on what a ‘real man’ should be?”

He took Mr. Ehrmann’s cue and started to implement life lessons into his class.

Building Men began at one middle school in the district in 2006 and grew on a shoestring budget, expanding school by school, year by year. For the first time this year, it’s being offered to fourth and fifth graders at seven different elementary schools. The program appeals to boys because of a basketball component, but its secret is how it dives into off-the-court issues through reinforced discussions on character.

“They sign up because they want to play basketball,” Mr. Horan says. “By the end of the year, they can better define their journey and a vision of their masculinity.”

A turning point for one student happened during the Rite of Passage camping trip. “When things wrapped up around 9:30 p.m.,” Mr. Horan recalls, “unbeknownst to me, one eighth grader had called our school’s ELA [English language arts] teacher.”

In that call, the student told her he needed to change. By the following Monday, the young man, who excelled as an athlete but put limited effort in class work, started to spend every lunch period with her for tutoring. “He went from 60s in all his classes, to passing with a 90 in ELA,” Mr. Horan says.

“Something happened on that Rite of Passage,” Mr. Horan says. “Something ... clicked for him that made him say, ‘I need to change my life.’”

Creating fellowship

Today, 33 lead coordinators, like Mr. Colabufo, work across 18 schools – more than half of those in the district – to lead sessions based on Mr. Horan’s curriculum.

This is Mr. Colabufo’s first year as a lead coordinator, a part-time position, though he taught in the district for 25 years. He’s known Mr. Horan for several of those years, noting many people are aware of the program’s success. “Joe’s a legend in this district,” Mr. Colabufo says.

By creating a fellowship of male peers and mentors, Building Men helps participants gain perspective, work to restore self-worth, and learn to calm emotions. The acronym SIR is a central component of lessons, standing for significance, integrity, and relationships.

Other key components include inspirational speakers, regular community service, and holding “chalk talks,” which Mr. Horan created to help students navigate adolescence. Humor and fun are also key.

The district’s interim Superintendent Anthony Davis says he’s told by teachers that students in Building Men “carry themselves differently” and engage adults with respect.

“They stand out,” Mr. Davis says, “because they have a positive impact. I want to spread that impact of this program across the district.”

In the 2021-2022 school year, Building Men reached 318 students with a self-reported attendance rate of 80%. The program’s participants have a 77% rate of graduation, according to data from that same year school year, compared with the district’s graduation rate of 71% overall.

Since 2017, Mr. Horan has served full-time as the program’s executive director, a role funded by the district. Some overtime is paid by Building Men. Other program costs, including staff salaries, are covered by outside grants and private donations. The school district offers space for the sessions free of charge. Mr. Horan says there is enough funding for most of this school year, but he is still raising more for end-of-year programming.

At a recent breakfast fundraiser, Shateek Nelson, a senior at Nottingham High School, shares his experience, having participated in Building Men since middle school.

He says he learned to see the bigger picture, rather than living in the moment. He also came to realize his actions affect others, and now he factors that into his decisions. “I would hate for my mom to cry at night because I was on the wrong path,” Shateek tells the audience.

Sustaining the program and ensuring its future is a daily priority for Mr. Horan.

“I have come to learn and experience that Building Men was created for a greater purpose,” he says. “I’ve learned I have to step out on faith.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Harnessing star power

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For the first time, an experiment in nuclear fusion has produced more power than it consumed in making it. That milestone holds huge potential for the world’s energy security beyond the era of fossil fuels.

But think of it in terms of the nonmaterial values that were at work in creating this scientific breakthrough: insight into the laws of the universe, precision in applying them, and faith in the progress of human knowledge. This historic success is about “seeing what was possible,” said Alex Zylstra, the lab’s principal experimentalist.

There are nearly 100 laboratories worldwide developing different models for fusion. Nearly 40 more are being planned or constructed. It’s not hard to see why interest is accelerating. The fuel inputs for fusion are abundant on Earth – enough to power humanity’s needs for at least 2,000 years. Significant scientific and engineering challenges remain. But the Biden administration has set a goal of making fusion commercially viable within a decade.

At a moment of profound concern about the future of life on Earth, a brief starburst in a bucket has given a new view of unprecedented potential. In a hundred-trillionth of a second, humanity has caught a new glimpse of thought unbound.

Harnessing star power

For the first time, an experiment in nuclear fusion has produced more power than it consumed in making it. That milestone holds huge potential for the world’s energy security beyond the era of fossil fuels.

The numbers for this achievement are daunting. Scientists at the National Ignition Facility in Livermore, California, shot 192 laser beams at a target smaller than a peppercorn, suspended in a chamber under temperatures 10 times hotter than the sun and twice the pressure at its core. The accuracy of the shot had to be within five-trillionths of a meter, its timing within 25-trillionths of a second. The whole event required less time than it takes light to travel an inch.

But think of it in terms of the nonmaterial values that were at work in creating this scientific breakthrough: insight into the laws of the universe, precision in applying them, and faith in the progress of human knowledge. This historic success is about “seeing what was possible,” said Alex Zylstra, the lab’s principal experimentalist.

Fusion is one of the most common physics processes in the universe, the core activity of every star, including the sun. But reproducing it has posed one of the greatest scientific challenges. There are nearly 100 laboratories worldwide developing different models for fusion. Nearly 40 more are being planned or constructed. Private enterprises have proliferated in the past five years.

It’s not hard to see why interest is accelerating. The fuel inputs for fusion are abundant on Earth – enough to power humanity’s needs for at least 2,000 years, perhaps indefinitely. It is carbon-free, and its radioactive byproduct dissipates quickly. It holds the potential of not just moving humanity beyond dependence on fossil fuels, but also removing carbon already emitted into the atmosphere. Significant scientific and engineering challenges remain. But the Biden administration has set a goal of making fusion commercially viable within a decade.

“We were in a position for a very long time where [commercialization] never got closer,” said Kim Budil, director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where the National Ignition Facility is based, “because we needed this first fundamental step. So we’re in a great position today to begin understanding just what it will take to make that next step."

At a moment of profound concern about the future of life on Earth, a brief starburst in a bucket has given a new view of unprecedented potential. In a hundred-trillionth of a second, humanity has caught a new glimpse of thought unbound.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

For improved interactions, be a learner

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Barbara Vining

Learning to let God’s pure love, rather than willfulness, guide our efforts to care for others opens the door to inspiration that blesses all involved.

For improved interactions, be a learner

Every human being makes mistakes now and then in the way we interact with others. The question is, How do we handle those mistakes?

I’ve found it wise to see our mistakes as learning opportunities. Then we can move forward instead of becoming mired in discouragement. The Bible counsels, “Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning” (Proverbs 9:9). And in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, points to the importance of learning from our experiences, writing, “Progress is born of experience” (p. 296).

The Christian Apostle Peter experienced this once when he was with others in a ship at sea, and the weather was stormy and turbulent. Christ Jesus, seeing from the shore that they were in trouble, was moved by God’s love to go to them. Jesus’ spiritual understanding enabled him to walk on the water toward the boat.

When Peter knew it was Jesus walking on the water toward them, he wanted to go to him. Peter started walking on the water as Jesus had bidden him, but he did so impetuously instead of conscientiously putting his trust in God. Consequently, the stormy conditions made him afraid, and he began to sink. “Immediately Jesus stretched forth his hand, and caught him, and said unto him, O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt?” (see Matthew 14:22-33).

Peter had to become humble and learn from experience to put his whole faith, his undoubting trust, in God. And his successful discipleship shows clearly that he made progress in this direction, even with a few missteps along the way.

It’s a good thing to become humble enough to learn from our experiences – to put our whole trust in God instead of resorting to human will. That’s not to say a blind trust, but a trust that comes from a growing understanding of God’s nature as good, and of everyone’s true identity as God’s loved children, spiritual and cared for at every moment.

I’ve had to learn, and am still learning, to understandingly trust God, instead of resorting to human will.

In raising my children, it wasn’t always easy to do this. As they grew up, sometimes it was tempting to judge them and to try to direct their thoughts and actions in ways that weren’t helpful or productive. But I found that taking a prayerful step back and affirming their identity as God’s pure, spiritual reflection resulted in more love and grace being expressed by us all. This approach has been helpful in other kinds of relationships, too, including in my interactions with patients in my public practice of Christian Science healing.

Our primary business, under all circumstances, is to let God – not willfulness – direct our thoughts. We can cherish the spiritual attitude captured in this verse from the Bible: “Teach me to do thy will; for thou art my God: thy spirit is good; lead me into the land of uprightness” (Psalms 143:10). When we are humbly leaning on God and trusting His care for all, then we and others around us are freer to feel God’s tender, caring love.

Trying to control others is a burdensome impossibility. Instead, we can realize and love the true identity of each individual as the spiritual and perfect image of divine Love, God. A great weight is lifted off of us when we turn to God with a humble, surrendering willingness to love Him with all our heart, and to love others enough to trust that God is caring for them, too.

Then, instead of feeling judged and discouraged, those we are caring for feel supported, loved, and willing to learn. And we feel the freedom of letting our own thoughts, including how we think about others, be inspired and directed by God, divine Love.

These words in a hymn I love speak to the prayerful, healing approach we can nurture and sing within ourselves:

Come we daily then, dear Father,

Open hearts and willing hands,

Eager ears, expectant, joyful,

Ready for Thy right commands.

(Elizabeth C. Adams, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 58, © CSBD)

A message of love

Holiday lights

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. See you again tomorrow, when our lineup will span from the World Cup to stories on how Ukrainians and Venezuelans are faring under differing forms of hardship.