- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Jan. 6 committee just made history. How will history judge it?

- Kherson survived Russian occupation. Now winter tests liberation.

- Russia has its troops. But does it have the economy to supply them?

- ‘We are lying to ourselves’: Film ban sparks debate in Pakistan

- In the northern Rockies, winter snows bring a flurry of hope

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Tainted campaign cash: Where should it go now?

What do you do if you’re a politician, and Sam Bankman-Fried – aka SBF, the indicted cryptocurrency tycoon – donated to your campaign? Maxwell Frost, soon to be the first Gen Z member of Congress, made a show last week of giving his tainted SBF money to charity.

“I’m donating his contribution to @ZebraCoalition, which helps serve LGBTQ+ youth,” Representative-elect Frost, Democrat of Florida, tweeted.

Such a move may feel morally satisfying, but wait: Shouldn’t that money go back to Mr. Bankman-Fried’s bankrupt company, FTX, for eventual payment to creditors? That’s what Beto O’Rourke, the Democrat who ran unsuccessfully for governor of Texas, did with his SBF money. And that actually may be the safer decision, say experts on financial regulation.

“The bankruptcy estate may come calling,” Yesha Yadav, a law professor at Vanderbilt University, told USA Today.

Dan Weiner, director of the Elections and Government Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, says that what Representative-elect Frost did was fairly common.

“When a candidate wants to disassociate from a donor, and for whatever reason, refunding the donation is impractical or undesirable, they’ll give it to a charity,” Mr. Weiner says.

But if a donation is found to have been illegal, “it will need to be refunded or disgorged to the U.S. Treasury even if the campaign didn’t do anything wrong,” Mr. Weiner writes in a follow-up email. “That doesn’t mean they can’t make a donation now, but they will have to come up with the money later.”

Another option, experts on campaign finance say, is to put money aside in escrow for possible restitution payment to victims.

Mr. Bankman-Fried was the second-biggest donor to Democrats in the 2022 cycle, at almost $37 million, according to Open Secrets. Another former FTX executive, Ryan Salame, donated $24 million this cycle, mostly to Republicans.

Federal prosecutors are now reaching out to campaigns and committees, seeking information about the donations. The journey into the thicket has only begun.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Jan. 6 committee just made history. How will history judge it?

The Jan. 6 committee seems to have aimed its work at history, rather than the short-term political cycle. On Monday, it made some of its own, for the first time recommending that a former president be prosecuted on criminal charges.

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

The Jan. 6 committee’s unanimous vote Monday to refer Donald Trump to the Department of Justice for possible prosecution of inciting insurrection and other federal crimes was historic. For the first time, Congress has urged criminal prosecution against a former or current chief executive.

But the panel’s most lasting legacy may be its story. After all this time, it is still shocking to hear the details of the attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election, and its culmination in a mob smashing its way into the U.S. Capitol.

We don’t know what history will say about this period of American politics. But the Jan. 6 documentation appears to be the kind of evidence on which history is based.

In that sense the hearings were reminiscent of other noteworthy efforts, such as the Senate Watergate committee or the Army-McCarthy hearings of 1954, says Joanne Freeman, professor of American history at Yale University.

“What resonates again and again and again in these public moments ... [is] if there’s a way to get a broad sweep of the public to see what’s happening, to think about what’s happening, and to watch at least some people stand up and say, ‘That crossed the line,’ that’s really important,” says Professor Freeman.

Jan. 6 committee just made history. How will history judge it?

The congressional Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, which held its final public meeting Monday, was in many ways a pathbreaking legislative effort.

Its slick production raised the standard for hearing presentations. Its investigations produced volumes of evidence implicating former President Donald Trump and his allies. It kept the issue of culpability for the attacks in the media glare.

Its vote to refer Mr. Trump to the Department of Justice for possible prosecution of inciting insurrection and other federal crimes was historic: For the first time, Congress has urged criminal prosecution against a former or current U.S. chief executive.

But the panel’s most lasting legacy may be its story. After all this time, it is still shocking to hear the details of the attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election, and its culmination in a mob smashing its way into the U.S. Capitol.

Brick by brick, the Jan. 6 panel has constructed an epic tale, from the former president, seemingly off-the-cuff, claiming he had actually won on the night of the election, to shouting matches in the Oval Office over false claims of election fraud, to Mr. Trump’s nonresponsiveness as the Capitol riot commenced.

We don’t know what history will say about this period of American politics. But the Jan. 6 documentation appears to be the kind of evidence on which history is based.

In that sense the hearings were reminiscent of other noteworthy efforts, such as the Senate Watergate committee or the Army-McCarthy hearings of 1954, says Joanne Freeman, professor of American history at Yale University and author of “The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War.”

“What resonates again and again and again in these public moments ... [is] if there’s a way to get a broad sweep of the public to see what’s happening, to think about what’s happening, and to watch at least some people stand up and say, ‘That crossed the line,’ that’s really important,” says Professor Freeman.

“No one should get a pass”

Still, the vote to recommend that Attorney General Merrick Garland prosecute Mr. Trump was the emphatic ending point to the Jan. 6 committee’s work. Possible charges listed were inciting insurrection, conspiracy to defraud the United States, obstruction of Congress, and conspiracy to make a false statement.

The panel also referred for possible prosecution five allies of Mr. Trump: chief of staff Mark Meadows, and lawyers Rudolph Giuliani, John Eastman, Jeffrey Clark, and Kenneth Chesebro.

The committee believes there is evidence Mr. Trump committed serious crimes, and if the Justice Department concurs then he should be charged as other Americans would be, said Rep. Adam Schiff, Democrat of California, in a hallway interview with reporters following the hearing.

“No one should get a pass. The day we start giving passes to presidents or former presidents or people in power ... is the day we can say that this was the beginning of the end of our democracy,” said Representative Schiff.

The referrals are purely advisory, however. The Department of Justice has been carrying out its own parallel investigation of the Jan. 6, 2021, events. Newly appointed special counsel Jack Smith has taken over that investigation as it relates to higher-level officials. His timeline is unknown – any indictment could be months away.

Stanley Brand, former general counsel to the U.S. House of Representatives and distinguished fellow in law and government at Pennsylvania State University, says he believes the committee’s actions Monday raise questions of impartiality. They could allow possible prosecutorial targets to request evidence they think is exculpatory from the panel, says Mr. Brand, whose law firm has represented Trump administration officials.

“From a separation of powers standpoint, the committee has pushed the envelope way beyond what have been previous limits to congressional power, especially by wading into this whole area of so-called criminal referrals, which have no legal binding effect and which, in my judgment, taint any subsequent Department of Justice action,” says Mr. Brand.

The question of political accountability

The focus on Mr. Trump at the final Jan. 6 panel public hearing has certainly fleshed out a committee-drawn portrait of the former president as the center of the so-called “Stop the Steal” effort, says Sarah Binder, a professor of political science at George Washington University.

But the purpose of the hearings has always seemed to be not just legal accountability, but political accountability as well, says Professor Binder. In that sense, its work can be seen more broadly as an attempt to understand the network that was involved in the attempt to overturn the 2020 vote.

The panel’s work is “also focused on the myriad ways in which he seemed to have been aided and abetted by members of Congress, by connections to these white nationalist groups and the connections of his campaign and insiders, [and] on the question of security at the Capitol and what went wrong there,” she says.

Still, the whole point of the broader effort was about getting a narrow result: blocking the peaceful transition of power.

“That is a core element of what it means to live in an electoral democracy. It’s still shocking to students, like myself, of our political system,” says Professor Binder.

No smoking gun

One thing the committee did not produce was a smoking gun – clear evidence of wrongdoing that summarized a conspiracy. In the Watergate investigation, for instance, the release of a White House tape that showed President Richard Nixon and his chief of staff admitting that they had tried to block the FBI’s investigation of the Watergate burglary proved that Nixon had long been lying to the American public.

But what the committee did do was amass a large amount of material from interviews, emails, texts, and documents, and present it in an easily understandable narrative.

“They revealed behind-the-scenes conversations and put those into the big picture,” says Barbara Perry, director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

For instance, the just-released executive summary of the Jan. 6 panel’s report contains a section that juxtaposes quotes from officials talking about debunking particular claims of voter fraud, against quotes from Mr. Trump continuing to use those same claims later in public.

On Dec. 15, 2020, then-Deputy Assistant Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen told Mr. Trump he had looked into allegations that “suitcases of ballots” had been delivered to polls in Georgia, and it hadn’t happened. “It was benign,” he said.

A week later, Mr. Trump said publicly that in Georgia officials were “pulling suitcases of ballots out from under the tables.”

Later, Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger spoke bluntly to the then-president about his continued Georgia claims.

“Well, Mr. President, the challenge you have is the data you have is wrong,” Mr. Raffensperger said.

Historical parallels

It’s not the norm in U.S. history for presidents or ex-presidents to be seriously linked to sedition charges. The closest might be John Tyler – but he had been out of office for years before he joined his native state of Virginia in seceding from the country he had once led.

Mr. Tyler served in a secession commission and was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives, but died before he could take his seat. (Coincidentally, he was also the first president against whom impeachment charges were brought.)

In the modern era, Watergate was “pretty bad – or at least that’s what we thought then,” says Manisha Sinha, professor of American history at the University of Connecticut.

But the number and seriousness of the offenses surrounding the aftermath of the 2020 election surpass even those of Watergate, says Professor Sinha.

They involved blocking the peaceful transfer of power, and included the storming of the Capitol.

“Even though we’ve had instances of political violence in this country, especially in the South after the Civil War ... [Jan. 6] was still, for many Americans, something they hadn’t seen in their lifetimes,” says Professor Sinha.

Many Republicans have criticized the Jan. 6 panel for being biased. While it included two GOP members, they were not authorized to participate by Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy.

Video clips of testimony were at times edited to manipulate conclusions, according to some Republican House members. The very smoothness of the presentations, edited as if they were a documentary, could cause some people to distrust the information, says Professor Freeman of Yale.

But she says the committee did establish a line by holding the hearings, holding them publicly, presenting evidence in an understandable narrative, and relying mostly on testimony from Republicans.

The line drawn is “not necessarily a wall against misinformation, but it’s at least a stumbling block. And for the historical record and for the present, I think that’s really important,” she says.

Senior congressional correspondent Christa Case Bryant contributed to this report.

Kherson survived Russian occupation. Now winter tests liberation.

In Kherson, freed last month from Russian occupation, jubilation has turned to determination as residents face winter without heat, light, or running water.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When Russian troops retreated last month from the southern Ukrainian city of Kherson, and Ukrainian forces marched in to liberate the regional capital, the mood among residents was jubilant.

Five weeks on, the harsh realities of life are testing Khersonians’ staying power: Russian artillery units are still bombarding the city, and before the Russians left they destroyed, and mined, as much infrastructure as they could.

That means electricity, water, and heat are all in short supply as winter sets in. Residents can generally get potable water from tankers that resupply them each day, but they have to go to the river, the Dnieper, for the water they use to wash in.

“This is not normal,” says one local resident. “Everyone is just trying to survive.”

Some residents find it all too much, and have gone to live elsewhere in Ukraine, often with relatives. Others are sticking with it, despite the artillery shells, the shortages, the high prices, and the cold.

“If we were able to survive nine months of occupation, I’m quite sure we will be able to survive this,” says Oleksandr Popov, an IT specialist. “It’s much easier and simpler when our people, our army, are here.”

Kherson survived Russian occupation. Now winter tests liberation.

In Kherson’s central plaza, Oleksandr Popov and his wife Olha tiptoe gingerly back to their car, loaded with diapers and baby food.

Five weeks ago, thousands of Ukrainians celebrated their city’s liberation from Russian occupation in this same plaza, hugging soldiers and waving flags. Today the streets are covered with black ice, the city is largely without power, and the Popovs just picked up supplies from a van distributing humanitarian aid. Without it, they couldn’t provide for their 4-month-old son Yehor, layered in coats, asleep in his mother’s arms.

“Unfortunately, you can’t get this stuff here in the shops now,” says Ms. Popova.

The three of them reach their taxi, an old Ford driven by their neighbor, and ride the few miles home. On the way, they pass playgrounds, gardens, and swing sets. They point to broken windows and splotchy holes in the nearby buildings: shell damage, they say.

Eight floors up, their own apartment windows are covered in tarps; an artillery barrage last month blew the glass out. When the shells landed, Mr. Popov was outside with Yehor; he fled into a neighboring building, which he could only get into because there was no electricity to power the lock. Ms. Popova and their 16-year-old daughter ducked for cover outside their apartment. Artem, their 11-year-old son, jumped under a first-floor balcony. One of the shells cratered the pavement where he and a group of friends had just been playing soccer.

These are scenes from a liberated Kherson. On Nov. 11, Ukrainian soldiers arrived in triumph, ending almost nine months of Russian occupation. But the occupiers didn’t retreat quietly across the Dnieper River. On their way out, they cut power lines and destroyed infrastructure. Since they left they have launched regular artillery attacks on the city, particularly the areas closest to the river.

Residents now live without stable access to electricity, internet, water, or heat. As winter sets in, the utility crisis is an acute challenge for the regional military administration, tasked with governing and rebuilding a beleaguered city. Many Khersonians still feel the ecstasy of liberation, even amid the agony of life under Russian fire. But unless the Ukrainian army advances farther east, the conditions will test how long the city can live on liberation alone.

Despite the hardships, Mr. Popov is optimistic. “If we were able to survive nine months of occupation,” he says, “I’m quite sure we will be able to survive this.”

Jubilant last month, leaving town now

A port city in southern Ukraine, Kherson came under Russian occupation March 2, little more than a week after the invasion. It was the only regional capital to fall, which lent its recapture last month special importance. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy made a surprise visit, declaring “the beginning of the end of the war.” Residents greeted their army with spontaneous parades in the city center, where a fountain is now draped with the Ukrainian flag.

Serhii Mykhailiuk was there.

Because the internet went down in the days before the Russian retreat, Mr. Mykhailiuk was out of the loop and surprised to see cars flying Ukrainian flags one night in early November. Even more surprising were the cheers he heard from people watching them. “How brave,” he thought.

The next morning his neighbors told him the city had been liberated, and Mr. Mykhailiuk was jubilant. For months he had avoided main roads in the city, fearing arrest by the Russian police, who he said often detained passersby who didn’t have proper documents. One Sunday in June, he too had been stopped on his way back from church, taken to a police station and held for 12 hours.

Now he was free. “I was very happy,” and joined the celebratory crowds in the city center plaza, he remembers. “I was crying.”

Three weeks later, Mr. Mykhailiuk was back at that same plaza, this time sitting in a heated tent set up by the government for residents without electricity, water, and other utilities. A bus to Kryvyi Rih, a city 120 miles north, would leave in half an hour; Mr. Mykhailiuk was taking it to go live with his parents.

“Now you can see how [the Russians] liberated us,” he says ironically, referring to Russian propaganda that the city had been “liberated” from Ukrainian rule in March. “We have no jobs, no electricity, no heating. Nothing.”

Until last month, Kherson’s electricity supply came from lines running in four directions, says Oleksandr Tolokinnikov, chief of press services for the Kherson Regional Military Administration. When the Russians left, he says, they cut and mined all four – and they have since targeted the grid with repeated attacks.

Mr. Tolokinnikov says 85% of the power system had been restored by early December. But that claim is hard to square with the number of residents who speak of electricity as a rarity, and who often lack water and gas too.

“This is not normal”

The city’s military and civil crises, meanwhile, have become part of daily life for its citizens.

Every morning, Natalia Kuchinskaya keeps an eye out from her apartment window for people gathering at a giant water tank near the city’s theater. A crowd means that she needs to grab her own plastic containers – each holding more than a gallon – and go fill up before the water runs out.

She, her husband, her daughter, and her two grandchildren live together and use water to drink, cook, wash, and flush toilets. The tank in the city center provides potable water, she says. The family collects water for everything except drinking and cooking straight from the river, a 10-minute walk away.

“This is not normal,” says Ms. Kuchinskaya, whose apartment last enjoyed electricity and running water a month ago. “This is just a situation that we have to adapt to. Everyone is just trying to survive.”

For the Popovs, survival means buying formula for their baby. Its price rose fivefold during the occupation, and they could afford it only because relatives abroad sent them money.

The issue now isn’t just the price; it’s also availability. Only one supermarket in the city is open, and lines are always long. The Popovs follow channels on Telegram, a social media messaging app, to track sources of humanitarian aid. But Mr. Popov works six days a week, and his wife can’t leave the baby alone while picking up supplies.

Still, the family isn’t going anywhere. Mr. Popov has lived in his apartment since he was a child, he has a good job in IT, and the grandparents still all live in Kherson. “We were hoping for the best, but then the war happened,” he says. “We just got stuck here. And nobody needs us anywhere else.”

On top of which, “it’s much easier and simpler when our people, our army, are here,” Mr. Popov says, turning to climb the eight flights of stairs to his apartment. He is wearing a bright yellow synthetic puffer jacket. On the chest is embroidered one word: SUPERMAN.

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting for this article.

Russia has its troops. But does it have the economy to supply them?

The invasion of Ukraine is transforming Russia’s economy, as the costs of the war mount. But while Western sanctions are hampering it, Russian industry is still delivering the materiel needed.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Russia may have more men to throw into a coming winter offensive, thanks to its recently concluded mobilization of 300,000 troops. But the men now headed for the front will need the full gamut of provisions.

Hence, the most critical question of the moment in Russia, yet one of the most difficult to answer, is whether the country's industry will be able to support those forces in the field.

The results so far are murky, but experts insist that the Russian economy will prove far more capable of delivering the needed materiel than its detractors claim. Still, sanctions and three decades of peacetime economics have left bottlenecks and dependencies that it will struggle to overcome.

Officially, defense spending is set to grow by 50% next year, though it’s impossible to know the actual amount, or any details about its disbursement. Some civilian businesses, such as textiles, food catering, and body armor, report a big uptick in production, presumably fueled by state orders.

“Russia’s economy is in the throes of profound change, and it might take some time for it to reach its new level,” says Ivan Timofeev, an expert with the Russian International Affairs Council. “In some areas it may be less modernized, but it will be sustainable.”

Russia has its troops. But does it have the economy to supply them?

When Russia called up 300,000 reservists to fill out the army’s ranks for the ongoing Ukraine war, the bureaucratic chaos and public angst that erupted as men were dragged from their civilian lives into unexpected military service got a lot of media coverage.

But there is a parallel, economic mobilization that is still going on, to rapidly reallocate resources and labor from the civilian sector to war production. And it remains largely shrouded in secrecy and controversy.

Russia may have more men to throw into a coming winter offensive, but the thousands of fresh Russian troops now headed for the front will need the full gamut of provisions, from heavy weapons and ammunition to cold-weather gear, body armor, daily meals, and medical supplies. The Ukrainian military is being funded and supplied by a nearly united effort of powerful Western economies.

Hence, the most critical question of the moment in Russia, yet one of the most difficult to answer, is whether the country’s industry will be able to deliver matching support for its forces in the field. The results so far are murky, as most information is classified. But experts who are willing to talk about it insist that the Russian economy will prove far more capable of delivering the needed materiel than its detractors claim. That said, sanctions and three decades of peacetime economics have left severe bottlenecks and import dependencies that the economy will struggle to overcome.

“The past 10 months has shown that the Russian economy can adapt [to the near-total sanctions regime] faster than even we expected, but in some specific areas it will be hard to replace Western imports,” says Ivan Timofeev, an expert with the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “We should not underestimate Russia’s capacities.”

“We’re going to have a different economy”

No one ever doubted the ability of the former USSR to field huge mechanized armies, or the capacity of its military-industrial complex to churn out masses of weaponry, from ballistic missiles, tanks, and fighter planes to assault rifles, helmets, boots, and field hospitals. But after the superpower’s collapse, its war machine disintegrated. Many of the most advanced military industries, ironically, ended up in the territory of the newly minted Ukrainian state, including those in the areas of missiles, tanks, aviation, shipbuilding, and helicopters.

Post-Soviet Russia also made the political decision to build a Western-style consumer economy, and until recently, even Russian President Vladimir Putin was warning about the dangers of repeating the disastrous experience of waging an arms race with the West. After a brief war with Georgia in 2008 revealed the serious shortcomings of Russia’s Soviet-legacy armed forces, the Kremlin ordered sweeping military reforms including reduction of conscription, an increase of professional forces known as kontraktniki, and reequipping all services with modern weaponry.

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, amid growing discord with the West, Russia began working to sanctions-proof its defense sector.

Dr. Timofeev argues that much of the public discussion in Western media about the impact of sanctions assumes that once a blow is struck against the Russian economy, the damage will be incapacitating and irreparable. Less thought is given to the possibility of blowback, and the abilities of the targeted country to find alternatives and workarounds, or even generate its own substitutes for the lost capacities. Though Dr. Timofeev would not comment directly on military industry, he did say that the principles that allow Russia’s civilian industry to adapt to new conditions should apply equally to Russia’s military production sector.

“Russia is a dynamic society; it learns and adapts and rearranges its priorities,” he says. “Russia’s economy is in the throes of profound change, and it might take some time for it to reach its new level. Import substitution, especially things like advanced technologies, microchips, etc., will be difficult. We’re going to have a different economy. In some areas it may be less modernized, but it will be sustainable.”

“I was a member of the public council in 2014, and that was the time authorities started a large-scale program for import substitution,” says Iosif Diskin, an economics professor at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics. “The aim was to close windows of vulnerabilities, to create our own technologies, microchips, electronics, etc., to lead to the independent development of our armed forces.”

Dr. Diskin says the effort has been at least partially successful. The impact of sanctions has been far less acute than widely predicted: Russia’s economy is facing only a shallow recession next year, and industrial production actually hit a six-year high last month. Much of that is probably due to state orders for military goods.

“Many military factories are currently working around-the-clock with three shifts. That has not happened since the end of World War II,” he says. “State orders are a boon. Maybe some sectors, like insurance, banking, and tourism, have suffered. But the total volume of industrial production is increasing.”

A boom in defense spending

National security spending has increased massively this year, after actually declining somewhat in recent years. President Putin has appointed a high-level council to oversee the country’s first wartime economic mobilization since World War II. But he has also promised to avoid Soviet-style state controls, such as nationalization and subordination to central planning.

Officially, defense spending is set to grow by 50% next year, though it’s impossible to know the actual amount, or any details about its disbursement. “Defense spending is a military secret. These are closed budget items, the disclosure of which is a criminal offense,” says Dr. Diskin. “If someone tells you a figure, it will either be a fiction or a direct path to prison.”

Some civilian businesses, such as textiles, food catering, and makers of drones, backpacks, and body armor, report a big uptick in production, which is presumably fueled by state orders.

Public sources indicate that deliveries of even the most sophisticated military hardware continue, and analysts privately scoff at any suggestion that the Kalashnikov Works in Kaluga can’t produce enough assault rifles, or the UralVagonZavod in Nizhni Tagil enough tanks, for the Russian army’s needs. Despite media predictions for months that Russia would likely “run out of ammunition,” there seems no letup of Russian artillery barrages in the Donbas, and a recent examination of the remains of Russian cruise missiles that have been raining down on Ukrainian infrastructure targets found that some of them have been made quite recently.

The baneful effects of war on public speech and freedoms in Russia have been well recorded. Analysts say that the impact of subordinating Russia’s fledgling market economy to state orders and military priorities is yet to be felt, but it is not likely to be healthy for the country’s long-term economic development.

“In order to get some short-term results, Putin is opening a Pandora’s box of economic consequences, including a reduction of economic efficiency,” says Nikolai Petrov, an expert on Russia with Chatham House in London. “Any kind of military mobilization leads to more pressure on private business, in the direction of a command economy. It will increasingly be the Kremlin, not the market, that decides what goods are to be produced, in what quantities and at what price.”

‘We are lying to ourselves’: Film ban sparks debate in Pakistan

Despite being banned in parts of Pakistan, the critically acclaimed film “Joyland” is exposing stories rarely seen on the big screen – and prompting honest conversations about how women and LGBTQ people fit into the conservative society.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Pakistani director Saim Sadiq’s feature debut “Joyland” follows an affair between Haider, a middle-class man trapped in a respectful but passionless marriage, and Biba, a transgender woman who dances in an erotic theater in Lahore. Critics have praised the film’s sensitive portrayal of queer characters and relationships, as well as its candid exploration of patriarchal gender norms.

Yet despite global acclaim, “Joyland” has struggled to find a home in Pakistan.

After the federal government overturned a nationwide ban in mid-November, officials in the country’s most populous province, Punjab, instituted their own. Opponents call the film an attack on the Muslim country’s social fabric, even a “call to arms” against the Islamic faith. But supporters say the movie’s only offense is taking a brutally honest look at Pakistani society.

Rasti Farooq, who plays Haider’s wife, describes “Joyland” as a sort of “unveiling,” and a chance to start crucial conversations about LGBTQ experiences in Pakistan.

“There are people in Pakistan who exist outside of this heteronormative identity, and they’ve existed since the beginning of time, so first and foremost we need to snap out of our denial,” she says. “I think we need to broaden the idea of what it means to be Pakistani.”

‘We are lying to ourselves’: Film ban sparks debate in Pakistan

It may be the most famous movie to come out of Pakistan this year, but you won’t find it in many of the country’s theaters.

“Joyland,” the feature debut of Pakistani director Saim Sadiq, won the independent Queer Palm award at the Cannes Film Festival – and a standing ovation – earlier this year for the way it deals with thorny issues of sexuality, gender conformity, and attraction. The movie follows an affair between Haider, a young, middle-class man who is trapped in a respectful but passionless marriage, and Biba, a transgender woman who dances in an erotic theater in Lahore. While their romance evolves, Haider’s wife, Mumtaz, is forced by her father-in-law’s decision to give up a job she loves and help care for the family’s home.

Throughout the film, shame, fear, and secrecy keep the protagonists from recognizing each other’s struggles, with devastating consequences.

The movie has received praise but also stirred controversy. Federal censorship authorities overturned their nationwide ban on the film in mid-November following a broad outcry, but a month on, “Joyland” remains banned in Punjab, the country’s most populous province. Still, the film has opened up a conversation about censorship, Islamic law, and LGBTQ experiences in Pakistan. Opponents say “Joyland” is an attack on the Muslim country’s social fabric, while supporters say the film’s only offense is taking a brutally honest look at the margins of Pakistani society.

“If we say that homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society, we are lying to ourselves, and if we say that such delicate relationships shouldn’t be depicted on screen, then we are lying as well,” says actor and director Usmaan Pirzada, an entertainment industry veteran. “Why shouldn’t we make movies about this?”

Call to arms or honest unveiling?

The precise nature of Haider’s attraction toward Biba – played by actor Alina Khan, who herself is trans – is one of several aspects that the filmmakers decided to leave ambiguous. Rasti Farooq, who plays Mumtaz, describes “Joyland” as an honest and brave exploration of “what happens to people when they can’t find answers within themselves, and when they’re also not allowed to express those queries and find those answers outside.”

Internationally, critics have appreciated the sensitive portrayal of queer characters and relationships, and have praised the film for its candid exploration of patriarchal gender norms. It’s even getting some early Oscars buzz.

Despite that acclaim, however, “Joyland” has struggled to find a home in the place it was filmed. The movie hit Pakistani theaters on Nov. 18, albeit with some scenes removed, including a couple of the film’s more sexually suggestive moments. But the provincial government of Punjab decided to ban even the censored version “in the wake of persistent complaints received from different quarters.”

Opposition to the film has centered around what right-wing activists have decried as a normalization of LGBTQ people and relationships. Sen. Mushtaq Ahmed, of the Jamaat-e-Islami (Party of Islam), has described “Joyland” as a “call to arms” against Islam, and wants it banned across the country.

“Obviously if it’s received the Queer Palm award,” said the senator, “what kind of film must it be?”

Ms. Farooq calls “Joyland” a sort of “unveiling,” and a chance to start crucial, nationwide conversations.

“There are people in Pakistan who exist outside of this heteronormative identity, and they’ve existed since the beginning of time, so first and foremost we need to snap out of our denial,” she says. “I think we need to broaden the idea of what it means to be Pakistani and … what it means to be people of faith, and to see if within these kinds of identities that are so dominant in Pakistan, we can even make space for [LGBTQ people].”

A political lightning rod

So far, attempts to make space for the LGBTQ community in Pakistan have had decidedly mixed results.

Sex between men is still criminalized under the country’s colonial-era penal code. Anti-sodomy laws are also on the books in the country’s Islamic Hudood Ordinances, though they have not been enforced since the 1980s. Same-sex couples often live in secret, due to stigma and fear of violence, and there are no anti-discrimination laws protecting people on the basis of sexuality.

Yet Pakistan was one of the first countries in the world to outlaw discrimination against transgender people, known in Urdu as Khawaja Sira. In 2018, the Pakistani parliament passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, legislation that gives every individual the right to be recognized as their “self-perceived gender identity,” with identity described as “a person’s innermost and individual sense of self as male, female, or a blend of both or neither.”

Though the bill passed largely without incident, experts say the trans community has since come increasingly under the microscope of religious and right-wing groups, which see the legislation as an attack on the Islamic way of life. “Joyland,” experts note, was released just as the campaign against the act was gathering momentum, and has therefore been even more politicized than it may have otherwise.

Writer and culture critic Jasir Shahbaz argues that the film has become the victim of a kind of mass hysteria.

“The issue with ‘Joyland’ is that people think that if a trans person is playing a trans character in a movie … then you are normalizing them,” he says. “I think it was made controversial by pressure groups because of their long-lasting campaign against trans people.”

Socialist politician Ammar Ali Jan agrees that at least part of the backlash comes down to timing, noting that Punjab is gearing up to be a political battleground in the 2023 general election.

“The economy is collapsing and without a cohesive plan for economic development, right-wing populists are falling back on culture wars,” he says. “This is a strategy being used all over the world, and it is being used in Punjab as one way of garnering support.

“It was very humbling”

On social media, viewers have been eager to discuss the film, frequently noting that the movie’s salaciousness has been exaggerated. One user wrote that “Joyland” is “a story of emotions, struggle, and everything wrong with middle class society in Pakistan.” Another called the ban “a disservice to the general public.”

Feminist organizer Zoya Rehman, who saw the film in Islamabad the day it was released, says that watching “Joyland” was a learning experience, exposing her to a side of Pakistan she wasn’t familiar with. She was particularly struck by Biba, the ambitious and self-possessed dancer.

“The kind of spaces that I’ve been in, or at least that my family wanted me to be in, were very decidedly middle class,” she explains. The only time they encountered Khawaja Siras – who, despite recent legal gains, tend to be poor and often work on the street – was when beggars would approach their car at traffic lights.

“It was very humbling and very subversive on the part of the filmmaker to show a trans woman trying to make it in showbiz,” she says.

Ms. Rehman thinks it’s that notion of middle-class respectability that’s been utilized to create controversy around the film.

“We’ve historically seen a lot of moral policing happen in Pakistan,” she says. “A lot of these are colonial ideas, but now they’re merged with very archaic religious expectations. … Every time affection is talked about, or romance is talked about or relationships outside the traditional cishet marriage are talked about, there’s always a hue and cry.”

In the end, the fact that the controversy around “Joyland” has not led to another nationwide ban is seen by some as a sign of progress. Karachi-based journalist Zebunnisa Burki found it heartening that her province, Sindh, and the federal government have allowed the film to play in theaters.

“I was convinced that everyone would buckle under this attack,” she says. “This is a state that’s obviously beholden to a lot of right-wing elements, so they could have easily said ‘we won’t release it.’ But they did release it and I think that is a big achievement in itself.”

Essay

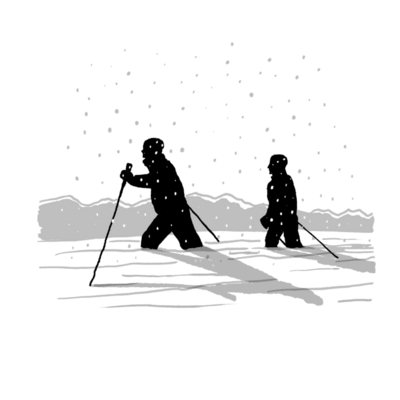

In the northern Rockies, winter snows bring a flurry of hope

The arrival of winter can be greeted with trepidation. But for this essayist, the darkening days and declining temperatures come with a promise.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Noah Davis Contributor

As the late-fall nights begin to stretch, I wake in the mornings to find the snow line on the mountain peaks has crept closer to the valley floor. The darkness seemingly gifting us water.

In the Intermountain West, life revolves around snowpack. A reservoir of high peaks catches the majority of the region’s precipitation in the form of snow. Months’ worth of freezing temperatures and darkness dam the moisture until the spring thaw releases water into creeks and rivers that swell with seasonal floods, leaving behind a green spring and early summer landscape.

So here, the first cold, dark nights of winter arrive with hope. Winters have grown shorter, snowpack across the Rocky Mountains has shrunk, and watersheds that rely on snowmelt have been reduced to a trickle. I imagine every hour of darkness, every hour of cold, every inch of snow buys more time.

It may be understandable to bemoan the gloom of early nightfall, the ice on the road. Yet these irritations are human concerns. When we expand the concept of our community to include the more-than-human world, we realize the need for darkness and the cold that accompanies it.

In the northern Rockies, winter snows bring a flurry of hope

My father and I wade through knee-deep snow in December. Evening rushes into the ravine we climb, half the canyon cloaked in shade. The snow that softened in the sun is already freezing in the forest’s shadow.

Here, 500 feet above the Blackfoot River in western Montana, winter has arrived with long, dark nights, single-digit temperatures, and three feet of snow. The elk and deer have moved to south-facing slopes at lower elevations, and the only tracks we see in the silent woods were left by ruffed grouse, pine squirrels, and a lone bull moose heading for a heavily timbered ridge. The raspy croak of a raven splits the gray sky.

“This snow is so good,” Dad says as he catches his breath and looks up at the towering ponderosa pines. “And there’s so much winter ahead. It looks like next year will be a good one.”

Here in the Intermountain West, life revolves around snowpack. A reservoir of high peaks catches the majority of the region’s precipitation in the form of snow, while months’ worth of freezing temperatures and darkness dam the moisture until the spring thaw releases water into creeks and rivers that swell with seasonal floods, leaving behind a green spring and early summer landscape.

However, as Western winters truncate with climate change and snowpack across the Rocky Mountains shrinks, watersheds that rely on snowmelt have been reduced to a trickle. Dry drainages are littered with fire-susceptible timber. Nonnative invasive species like cheatgrass quickly spread across hillsides no longer blanketed for months in snow. European brown trout swim up creeks too warm for native cutthroat.

Even with this aggressive warming trend, one that many of us can recognize in our short lifetimes, the cold, dark nights arrive in the North with hope. Not hope for the reversal of such warming weather patterns, but a hope of the present moment – that the immediate winter will spare us some respite from the summer to follow. Maybe this winter will bring good storms that dump many feet of snow on the mountains. Maybe with the days growing shorter, the freeze will happen sooner. How much more time will that buy the arctic grayling? The ruffed grouse? The glacier lilies? The Alpine fescue? The Clark Fork River?

It’s understandable to bemoan the gloom of night that arrives at 4:30 in the afternoon, the ice on the road, yet these irritations are human concerns. When we expand the concept of our community to include the more-than-human world, we realize the need for darkness and the cold that accompanies it in places like northern Montana.

The hope for a cold winter often begins during fire season in the heat of summer – when the smoke from burning pines and firs chokes the air, and the sun is a red eye in the sky. If the smoke lingers into September and October, the first snowfall can feel like a gift.

What’s more, the hope of an early snow and growing dark means that a long winter might result in a good water year and fewer fires.

As the late-fall nights begin to stretch, I wake in the mornings to find the snow line on the mountain peaks has crept closer to the valley floor. The darkness seemingly gifting us water. And it’s here, during those hours we humans huddle in our lighted rooms, that I imagine every hour of darkness, every hour of cold, every inch of snow buys more time. That those minute measurements will mean the bull trout won’t feel baked in their own river, that the sandhill cranes won’t return to find their nesting grounds dry, that the fires won’t start in May. It gives me hope that maybe next year will be better than the last. Maybe not for the next decade, but maybe just next year. Irrational, yes, but what form of hope doesn’t step across the line realists draw?

And when I write the words us or we, I mean the community of the Northern Rockies, which touches another community, that touches yet another community, building outward, and, finally, touching yours. Hasn’t the smoke from the West reached the East Coast? Isn’t it all our air?

As we enter the heart of another winter, anticipation builds. Again, it’s somewhat strange to hope for something so immediate – just this winter – when one can hope far more extravagantly. Maybe this is because those who live here with acute awareness, who know what it means to have ash falling on them as they walk from their car to the grocery store, understand how precious a winter can be. How every hour of darkness might give us an hour more to enjoy the light.

Back on the mountain, the color of the forest has shifted to a gray-tinted blue. The last moment of day before darkness begins its long march toward morning. A storm has come down from the peak, and it’s as if night has become a cloud to chase Dad and me back to our vehicle. The fringes of a snow shower overtake us, and, with the flakes, a cold that causes me to shiver, even under the heft of my Woolrich coat.

“How many inches do you think will fall tonight?” I ask Dad.

“3 or 4,” he says as he unlocks the car.

“Maybe if we’re lucky, we’ll get 5.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Africa’s new era of humble leadership

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Thirty years ago, the African National Congress (ANC) represented a new African era shaped by justice, shared economic prosperity, and the rule of law. Now, South Africa’s ruling party offers a different measure of leadership on the continent – chastened by its shortcomings, tenuous in power.

That marks a transformation in what Africans expect from their leaders. Younger, better educated, and entrepreneurial, they are increasingly intolerant of graft and impatient for opportunity. There is a “reorientation of the mindset,” Abideen Olasupo, founder of YVote Naija, a Nigerian organization promoting youth participation in elections, told openDemocracy. “We have to carry our destiny in our hands.”

Few seem more aware of these changing expectations than South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who survived weeks of unresolved corruption allegations and a threat of impeachment to win reelection today as his party’s leader. “The ANC today is its weakest and most vulnerable since the advent of democracy,” he warned the party earlier this year. “Our weaknesses are evident in the distrust, the disillusionment, the frustration that is expressed by many people towards our movement and government.”

In Africa, one-man, one-party rule is giving way to a new era of leadership humbled by the popular demand for honest, effective government.

Africa’s new era of humble leadership

Thirty years ago, the African National Congress (ANC) represented a new African era shaped by justice, shared economic prosperity, and the rule of law. Now, South Africa’s ruling party offers a different measure of leadership on the continent – chastened by its shortcomings, tenuous in power.

That marks a transformation in how ordinary Africans view government and what they expect from their leaders. Younger, better educated, and entrepreneurial, they are increasingly intolerant of graft and impatient for opportunity. There is a “reorientation of the mindset,” Abideen Olasupo, founder of YVote Naija, a Nigerian organization promoting youth participation in elections, told openDemocracy. “We have to carry our destiny in our hands.”

Few seem more aware of these changing expectations than South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who survived weeks of unresolved corruption allegations and a threat of impeachment to win reelection today as his party’s leader. “The ANC today is its weakest and most vulnerable since the advent of democracy,” he warned the party earlier this year. “Our weaknesses are evident in the distrust, the disillusionment, the frustration that is expressed by many people towards our movement and government.”

Mr. Ramaphosa’s hold on power is no more assured than his party’s. In power since 1994, it has overseen the dramatic crumbling of Africa’s strongest industrial economy due largely to corruption. South Africans endure daily power cuts lasting as long as 11 hours. Mr. Ramaphosa has erected new government scaffolding to root out graft. So have other countries and regional blocs on the continent. But that has done little to boost the public’s confidence. A year ago, the ANC won just 46% of the vote in municipal elections.

That follows a trend across Africa. As The Economist noted last week, opposition victories are becoming normal: “25 of the 42 new African leaders to take office in the past 11 years were opposition candidates – the highest number in three decades.” Over the next two years, 30 African countries, including South Africa, will hold elections for head of state or parliament.

The African Development Bank estimates that $148 billion is lost to graft in Africa every year. More than half (56%) of Africans say corruption in their country has increased, according to the latest survey by Afrobarometer across 20 countries. Expectations of democracy have become deeply entrenched: Eighty-one percent reject one-man rule, 79% reject one-party rule, and 62% say government accountability is more important than effectiveness.

“The issue of good governance and transparency is more than just about wasted money – it is about the erosion of a social contract and the corrosion of the government’s ability to grow the economy in a way that benefits all citizens,” said Antoinette M. Sayeh, deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund, at an anti-corruption conference in Botswana in June. “Improving governance and accountability in Africa is not only possible; but it is actually happening.”

In Africa, one-man, one-party rule is giving way to a new era of leadership made humble by the popular demand for honest, effective government.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Hearts made whole at Christmas

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ginger Emden

Whatever our holiday plans may look like, we can experience the joy and love that come from welcoming the eternal Christ into our hearts.

Hearts made whole at Christmas

It’s the Christmas season again! Beyond the festivities and gift-giving, Christians around the world are again revisiting the nativity story and celebrating the legacy of Christ Jesus’ remarkable life and works.

At this time of year, I’ve frequently pondered something Mary Baker Eddy, a follower of Jesus who discovered Christian Science, said: “I love to observe Christmas in quietude, humility, benevolence, charity, letting good will towards man, eloquent silence, prayer, and praise express my conception of Truth’s appearing” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 262).

While Jesus’ appearance on earth was brief, the Christ – the healing and saving Truth that Jesus demonstrated – is incorporeal and eternal and appears to the receptive heart in every age.

In the Christmas story in the opening chapters of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, we find the story of Jesus’ birth. Obeying Caesar’s decree that citizens return to their ancestral homes in order to be counted in a census and pay their taxes, Jesus’ parents – a very pregnant Mary and a faithful Joseph – traveled from Nazareth to Bethlehem, where Joseph had been born.

But their trip served a higher purpose than the mere fulfillment of a civic duty – it was the fulfillment of prophecy. Their babe, Jesus, was in fact the promised Messiah, or Way-shower, who would bring to the world the good news that the Christ or divine Comforter is with us always. Nothing prevented them from reaching their destination and fulfilling their holy mission. Nor, it seems, was anything able to dampen their faith and trust in God’s loving care.

There’s something sacred, timeless, and relatable about the nativity story, and it brings to mind an experience our family had a couple of years ago. One night as my husband and I tucked our girls into bed, we shared with them the news that we couldn’t travel to visit family for Christmas because of another Covid-related lockdown in our area of the country.

“My heart is broken,” exclaimed our older daughter.

I was quiet. My heart ached as well.

But my husband spoke up. “You can’t cancel the Christ!” he said. I felt my heart soften in agreement. Christmas is a time to honor the Christ, to demonstrate that Christ is an eternal, healing presence. Every one of us, at any moment, can feel the living presence of Christ, Truth.

The Apostle Paul exemplified the spirit of the Christ despite the extreme adversity he faced. Throughout his wide-ranging healing ministry, he felt the presence and protection of God, divine Love. He said: “Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? ... I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:35, 38, 39).

Instead of being sucked in by sadness, I felt a growing conviction that this same divine Love was present to comfort all of us. This was surely evidence of the appearance of the Comforter.

That Christmas turned out to be a holiday like none other. We savored the time with our immediate family and found joy in discovering new ways to minister to friends and neighbors. Sure, the presents, food, and parties we associate with the holiday season can be so much fun. But we saw that the real gift of Christmas is the eternal, inextinguishable Christ, Truth – that unbridled, pure light of hope and healing that obliterates the darkness of mortal thought. Like a brilliant idea, that spiritual light is always there, and it is perceived when thought is ready to receive it.

Was it the holiday that we’d planned? No. Was it one that we ultimately needed and thoroughly enjoyed? Yes!

Like so many people around the world, what we’d most needed was the divine reassurance that our hearts were whole.

Any year can be a trying one. Thus, the Christmas story continues to be relevant – a reminder that Christ brings to us the tender, healing message of our Father-Mother God, Love, wherever we are. Christ’s appearing in consciousness is as certain as the dawning sun and breaks through the clouds of fear and hopelessness.

Whether we’re at home or traveling this Christmas, we can keep an eye out for Truth’s continual appearing. This will no doubt make for a holy day.

Adapted from an article published in the Dec. 12, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Light on the first night

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come again tomorrow, when I write about the political future of former President Donald Trump.