- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Classified documents seem to be everywhere. Is there a solution?

- The Georgia probe that may indict a president

- Is France finally paying respect to its aging African soldiers?

- In Valley of the Kings dig, an all-Egyptian team makes its mark

- Cold journey. Lasting joy. My trek to see the northern lights.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Mikaela Shiffrin’s triumph over bitter disappointment

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Earlier this month, on the cusp of skiing history, Mikaela Shiffrin opened up to The Associated Press. “The only thing I can really guarantee,” she said, “is that at some point it ends, and I’ll have to be the one who takes the defeat.”

That might sound remarkably dour from the best skier on the planet, perhaps ever. But it was also quintessential Mikaela Shiffrin.

The last time many Americans saw her, she was crying. After going medal-less and failing to finish three of her five individual races in the 2022 Beijing Olympics, Ms. Shiffrin was characteristically blunt. “Right now, I just feel like a joke,” she said on national television.

Yesterday, the emotions were so different. She became the winningest female skier ever, taking first place in a World Cup race for an 83rd time. The feat borders on incomprehensible. The previous record-holder, Lindsey Vonn, won her 82nd race at age 33. Ms. Shiffrin is 27. This season, she has nearly double the points of her closest competitor on the World Cup circuit, at one point winning five races in a row. Earlier today, she won her 84th race for good measure. The fact all this comes less than a year after the Beijing Games is no coincidence.

After the accidental death of her father in 2020 and the upheaval of the pandemic, there were questions of whether Ms. Shiffrin would ever regain her early career dominance. Beijing raised more questions. But what has always made Ms. Shiffrin extraordinary is not talent. It is that she takes nothing for granted. Her career is the apotheosis of preparation, the willingness to commit oneself body and soul to the tedium of process, trusting that results follow work in a direct line.

Speaking of Beijing, Ms. Shiffrin’s mother recently told The New York Times: “Those will be lifelong lessons.” Yesterday, the world saw what it looks like when such lessons become fuel for an honest and unrelenting heart.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Classified documents seem to be everywhere. Is there a solution?

Recent discoveries suggest that mishandled classified documents may not be that rare. One problem: a “tsunami” of government secrets, and a system that defaults to classifying everything.

“These are crazy times,” comedian Jimmy Fallon quipped last night. “Right now, Walgreens has deodorant behind a locked case, while classified documents are laying around like J. Crew catalogs all over the house.”

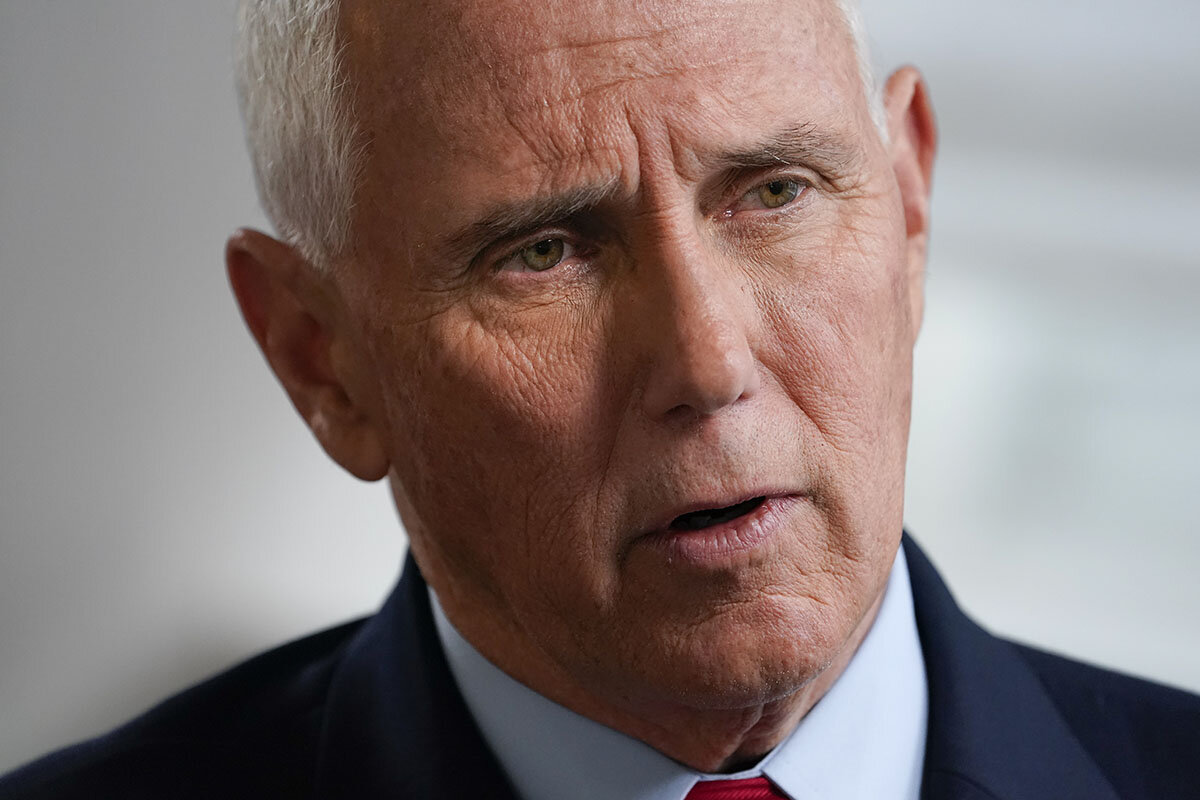

Indeed, the discovery of classified documents in the home of former Vice President Mike Pence, disclosed Tuesday, has launched countless jokes – and put a punctuation mark on the ongoing saga of such materials turning up in the private homes and offices of President Joe Biden and his predecessor, Donald Trump. Both the president and former president are now under investigation by special counsels.

But the news about Mr. Pence – who served under Mr. Trump and stated categorically in a November CNN interview that he “did not” take any classified documents from the White House – has made clear this is a more widespread problem. To many national security experts, it’s giving credence to the view that way too much information is marked “classified” and that the handling of such documents has long been fraught.

Says Elizabeth Goitein, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program: The Pence news “confirms what has become evident, which is that there’s a systemic problem here.”

Classified documents seem to be everywhere. Is there a solution?

“These are crazy times,” comedian Jimmy Fallon quipped last night. “Right now, Walgreens has deodorant behind a locked case, while classified documents are laying around like J. Crew catalogs all over the house.”

Indeed, the discovery of classified documents in the home of former Vice President Mike Pence, disclosed Tuesday, has launched countless jokes – and put a punctuation mark on the ongoing saga of such materials turning up in the private homes and offices of President Joe Biden and his predecessor, Donald Trump. Both the president and former president are now under investigation by special counsels.

But the news about Mr. Pence – who served under Mr. Trump and stated in a November CNN interview that he “did not” take any classified documents from the White House – has made clear this is a more widespread problem. To many national security experts, it’s giving credence to the view that way too much information is marked “classified” and that the handling of such documents has long been fraught.

The Pence news “confirms what has become evident, which is that there’s a systemic problem here,” says Elizabeth Goitein, senior director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program.

Part of the problem, she says, is that “when there’s any uncertainty, officials default to classifying.” And when so much information is marked classified, “you are bound to run into situations where officials are either cutting corners or just making mistakes.”

Matthew Connelly, a historian at Columbia University, describes the dilemma of over-classification by paraphrasing former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart. “When everything is classified, nothing is classified,” says Professor Connelly, author of a forthcoming book, “The Declassification Engine.”

There’s even a term for classified documents leaving secure locations, accidentally or otherwise: “spillage.” Within the U.S. government, some 2,000 people are known as “original classifiers,” Ms. Goitein says – that is, allowed to determine what information should be classified. Then there are some 4 million government employees with security clearance, including more than 1 million with top-secret clearance.

In the vast majority of cases, such spillage is deemed inadvertent, and not prosecuted. In recent years, however, some high-profile officials have been prosecuted for mishandling classified information. Retired Gen. David Petraeus, a former CIA director, received probation and a fine after pleading guilty. Former National Security Adviser Sandy Berger faced similar punishment for unauthorized removal of classified information from the National Archives.

The cases of Mr. Trump, Mr. Biden, and Mr. Pence all appear largely centered on how documents are handled in the final stretch of an administration – in Mr. Biden’s case, most of the documents came from his days as vice president under President Barack Obama. Presidential transitions entail a certain level of frenzy, as an outgoing administration seeks to pack as much official activity as possible into its final days in office, even as it prepares to move out of the White House complex.

In the Trump administration’s case, there seemed to be an extra level of chaos, given Mr. Trump’s unwillingness to concede defeat and the ensuing turmoil around the Jan. 6, 2021, siege of the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters.

Much remains to be learned about all three cases of misappropriated classified documents. In the case of Mr. Biden, the fact that classified materials from his days as a U.S. senator turned up in his Wilmington, Delaware, home – along with more documents from his tenure as vice president – adds a new dimension to his case. That disclosure came last weekend from Mr. Biden’s private lawyer, following a 13-hour FBI search last Friday of the Wilmington house. In total, six more documents were found.

All three men are eyeing the 2024 presidential race, adding a political aspect to the documents situation. Mr. Trump is already a declared candidate, Mr. Biden is expected to announce his reelection campaign after the State of the Union address on Feb. 7, and Mr. Pence has taken steps toward a possible run. At least one Republican member of Congress has suggested that Mr. Pence should have a special counsel assigned to his case, in the name of fairness.

The recent drip, drip of information over classified documents has led to widespread speculation about what might be laying around at the homes or offices of other past presidents. Representatives of former Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama told CNN that classified records were handed over to the National Archives when they left office, and that the ex-presidents were not planning additional searches.

According to The Associated Press, former President Jimmy Carter once found classified documents at his home in Plains, Georgia, and returned them to the National Archives.

Professor Connelly, the historian, points to decadeslong, bipartisan efforts to improve the nation’s system of classification, seemingly to little avail.

In 1998, legislation spearheaded by liberal Democratic Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York and conservative Republican Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina resulted in the creation of an entity called the Public Interest Declassification Board.

“But if you haven’t heard of it, that’s your answer,” Professor Connelly says.

He points to a recent comment by Mark Bradley, director of the Information Security Oversight Office, who reported last July that his office had stopped trying to count annual production of government secrets: “We can no longer keep our heads above the tsunami.”

It’s a problem, Professor Connelly says, that is so acute, it supersedes partisanship. And with major figures from both parties in trouble over the handling of classified material – shining a spotlight on the issue – perhaps that will lead to a solution.

Political analysts note that there’s likely little Mr. Biden can do to reform the nation’s classification system while he’s under investigation, but looking down the road, some experts are hopeful.

Ms. Goitein of the Brennan Center proposes “tightening the substantive criteria for classifying documents in the first instance.” And she suggests that advances in machine learning be used to help limit what’s classified. That is, use computers to recognize phrases and patterns of words that lead to classification.

The addition of Mr. Pence into the discussion could also help build momentum toward solutions, she says.

“It’s no longer a Trump versus Biden narrative,” Ms. Goitein says. ”I think that distracted from some of the systemic issues we need to be looking at.”

The Explainer

The Georgia probe that may indict a president

The U.S. continues to edge toward a fraught moment of decision: Plotting to overturn an election is not the sort of thing a democracy can overlook, experts say. Others point to a need to think carefully before prosecuting a president for talking to an election official.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Noah Robertson Staff writer

On Jan. 2, 2021, President Donald Trump called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and asked him to “find 11,780 votes” to overturn the results of the state’s presidential election.

It was a call that may go down in history as the launching pad of a criminal inquiry. Atlanta-area prosecutors have conducted a wide-ranging investigation into whether the Trump campaign and its allies illegally interfered in Georgia’s 2020 vote and electoral certification.

Now that probe has reached a turning point. A special grand jury empaneled by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has wrapped up its work and written a final report. A judge is weighing whether to publicly release the document. On Tuesday, Ms. Willis said a decision on whether to indict the former president and his associates was “imminent.”

Thus, it is possible that Georgia will be the first place America might encounter the political and legal ramifications of court action against a former leader.

For Norm Eisen, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and co-author of a lengthy study of the case, “Probably the most important question for our democracy is whether there are charges against the former president, to the extent that the attempted coup intersected with Georgia.”

The Georgia probe that may indict a president

On Jan. 2, 2021, President Donald Trump called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and asked him to “find 11,780 votes” to overturn the results of the state’s presidential election.

It was a call that may go down in history as the launching pad of a criminal inquiry. Since then, Atlanta-area prosecutors have conducted a wide-ranging investigation into whether the Trump campaign and its allies illegally interfered in Georgia’s 2020 vote and subsequent electoral certification activities.

Now that probe has reached a turning point. A special grand jury empaneled by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has wrapped up its work and written a final report. Following a Jan. 24 court hearing, a state judge is now weighing whether to publicly release the document.

Ms. Willis will then weigh whether to indict Mr. Trump and associates who helped try to influence the Georgia results. She appears to be nearing a fateful decision more quickly than the federal investigation overseen by special counsel Jack Smith – on Tuesday, she said a decision was “imminent.”

Thus, it is possible that Georgia will be the first place America might encounter the political and legal ramifications of court action against a former president. Some analysts believe the Georgia case has weaknesses and Ms. Willis may give it a pass. Others think it is strong and that an indictment is the most likely outcome.

“Probably the most important question for our democracy is whether there are charges against the former president, to the extent that the attempted coup intersected with Georgia,” says Norm Eisen, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and co-author of a lengthy study of the case.

Here are some answers to basic questions about the Georgia investigation:

What’s new in the case?

A special grand jury in Fulton County has heard months of testimony in the Georgia election case. Trump lawyers Rudy Giuliani and John Eastman and South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham are among the witnesses who have appeared before the panel.

Now the grand jury appears to have wrapped up its work. On Tuesday, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Robert McBurney held a court hearing to hear positions on whether the grand jury’s final report should be released to the public.

Ms. Willis argued that it should not, saying she was “mindful of protecting future defendants’ rights.” Disclosing the report now could complicate possible indictments stemming from the information, she said.

“Decisions are imminent,” the prosecutor told Judge McBurney.

No lawyer for Mr. Trump or his associates attended the hearing. An attorney representing a coalition of media groups argued that it is in the public interest to release the special grand jury’s work as soon as possible.

Under Georgia law, special grand juries cannot issue their own indictments. Prosecutors can use the information from their final report to seek indictments from a regular grand jury.

“People are rightfully putting a lot of emphasis on this report, perhaps not because of what we’ll find out ... but more so because it certainly demarcates a new iteration of this all coming to a close or just beginning in a very new and important way,” says Anthony Michael Kreis, professor of law at Georgia State University College of Law.

What did Georgia investigate?

Georgia was central to Mr. Trump’s efforts to overturn the election and stay in the Oval Office. A swing state, it gave Mr. Biden a narrow victory of 11,779 votes. The Trump team appears to have believed that if they could get state officials or legislators to throw a wrench in the election certification process, it was possible other states would halt or delay their own proceedings.

The January call from Mr. Trump to Mr. Raffensperger, in which the president made a litany of debunked and unsubstantiated claims about alleged election fraud in a number of states, is a crucial part of the Georgia investigation. Chief of staff Mark Meadows and several conservative lawyers were on the line for that call, as well.

But it wasn’t Mr. Trump’s first call to Georgia officials pressuring them to change numbers. Almost a month earlier he had called Gov. Brian Kemp and urged him to allow state legislators to award state electoral votes. Governor Kemp refused.

Later in December, Mr. Trump called Frances Watson, the lead investigator in Mr. Raffensperger’s Secretary of State office, who was conducting an audit of mail-in signatures. He urged her to find the “dishonesty” he alleged was rampant in the state’s absentee ballots.

“The people of Georgia are so angry at what happened to me,” Mr. Trump told Ms. Watson.

But phone calls are not the only Trump team actions now in the Fulton County prosecutor’s sights.

They are looking at alleged misstatements about election fraud made before state legislative committees by Mr. Trump’s lawyer, Mr. Giuliani. Last August, Fulton County prosecutors informed Mr. Giuliani that he is a “target” of their investigation.

And prosecutors revealed in court documents last year that 16 people who took part in the fake elector plan, which drew up a purported list of Electoral College voters allied with Mr. Trump, have also received letters telling them they are “targets.”

What is going to happen now?

Ms. Willis has said nothing directly about her intentions. It is possible that the work of the special grand jury has convinced her that bringing prosecutions in the election case may not result in convictions.

However, Ms. Willis – an elected prosecutor – has shown an affinity for big, difficult cases that invoke Georgia’s racketeering law, which is more sweeping than its federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) counterpart. Last August she filled a 220-count racketeering indictment against 26 people for allegedly conducting home invasions of Atlanta celebrities and social media influencers.

It is unlikely she will go after only high-level, or low-level, actors in the election case, say legal experts. She might wrap them all together in one large prosecution.

“I’d almost be surprised if it’s not structured as a RICO prosecution,” says Clark Cunningham, professor of law at Georgia State University College of Law.

Among the crimes that could be alleged are solicitation to commit election fraud or conspiracy to commit election fraud, harassing poll workers or interfering with the administration of an election, criminal solicitation, and false statements made in support of the fake electors plan.

The Brookings Institution has compiled a 304-page analysis of the reported facts and applicable laws of the Fulton County Trump investigation. Asked if he believes the probe will result in charges, co-author Mr. Eisen says, “Yes, I do.”

If Mr. Trump himself is charged, his most important factual defense will be that he was just pressing his strong good-faith belief that he had actually won the Georgia vote, according to the Brookings analysis.

But just because he thought he had won, that does not mean he could break laws in furtherance of that belief, says the analysis. And the record is “uniquely free” of any evidence that he did win, the report says. The existing outcome was affirmed and reaffirmed under a process overseen by GOP officials.

Still, some legal analysts are skeptical of the Georgia case.

It is possible prosecutors don’t have enough evidence of alleged crimes, said former federal prosecutor Renato Mariotti on a recent episode of his podcast, “It’s Complicated.” The recorded phone call between Mr. Trump and Mr. Raffensperger might not be enough to hang a prosecution on.

As an elected prosecutor who will face voters in 2024, Ms. Willis has a motive to bring a prosecution no matter what, Mr. Mariotti added. That may be especially true given Fulton County’s deep blue electorate. Mr. Trump’s lawyers are sure to make that a significant part of any defense.

Mr. Trump can insist that he had a genuine belief that suitcases of ballots were illegally counted. “‘I’m president and I’m talking to a state official about my election’ – we need to be very careful about prosecuting that,” said Mr. Mariotti.

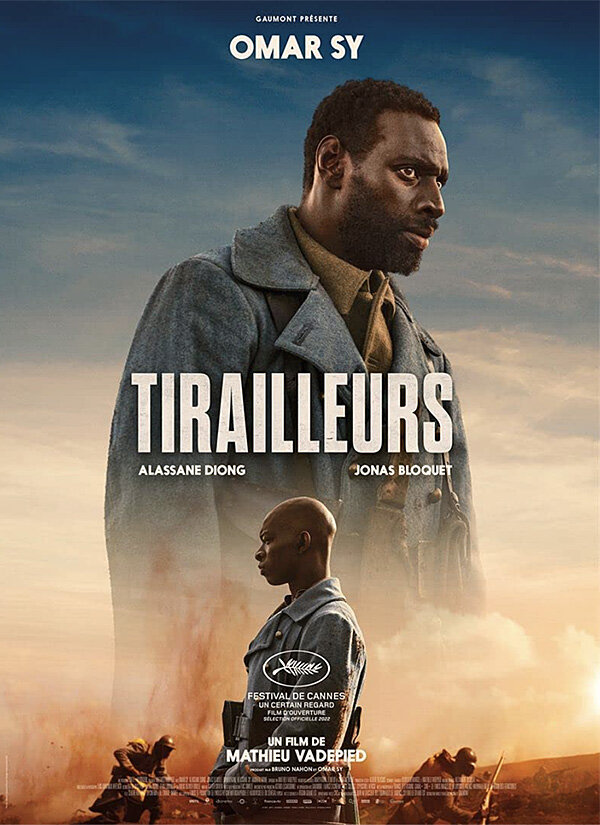

Is France finally paying respect to its aging African soldiers?

Tirailleurs sénégalais – Senegalese colonial infantry – fought wars for France, but have been treated like second-class soldiers. Now, with a blockbuster film and pension reform, they may be getting their due.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Born in Senegal in 1933, Gorgui M’Bodji fought as a tirailleur – colonial infantryman – in both the First Indochina War and the Algerian War. But today, the contributions of Mr. M’Bodji and his comrades in arms to French history are lost on a majority of the French public. Even if they represented around 200,000 troops in World War I and continued fighting for the French army until the end of the war in Algeria in 1962, their presence in school history books is slim.

Now, there are few tirailleurs remaining. But between a new blockbuster film and recent political gains – particularly the right to receive their French military pensions without meeting onerous residency requirements – there is hope that this will be a critical moment for France to revisit an important piece of its history.

That would provide an opportunity for dialogue about how the country can properly transmit the collective memory of its colonial past and do right by those who risked their lives to maintain French dominance.

“We’re in a place now where we can open that door, expose and challenge injustices,” says former Justice Minister Christiane Taubira. “France would not be what it is today without this story.”

Is France finally paying respect to its aging African soldiers?

For many in the cinema’s audience, “Tirailleurs,” a tale about African soldiers who fought for France during World War I, is familiar. After all, they are the grandchildren or great-grandchildren of tirailleurs sénégalais – Senegalese colonial infantry – and heard their war stories throughout their childhood.

But for Gorgui M’Bodji, it was more than just familiar. He lived it.

“Everything in the film – the trenches, the fortification walls – I saw that!” he says, bounding from his chair as a dozen military medals jingle against his chest.

Born in Senegal in 1933, Mr. M’Bodji fought as a tirailleur in both the First Indochina War and the Algerian War. But today, the contributions of Mr. M’Bodji and his comrades in arms to French history are lost on a majority of the French public. Even if they represented around 200,000 troops in World War I and continued fighting for the French army until the end of the war in Algeria in 1962, their presence in school history books is slim.

Today, only a few tirailleurs remain. But between a blockbuster film and recent political gains – in particular the right to receive their military pensions without meeting onerous residency requirements – there is hope that this will be a critical moment for France to revisit an important piece of its history. That would offer an opportunity for a multilayered dialogue about how the country can properly transmit the collective memory of its colonial past and do right by those who risked their lives to maintain French dominance.

“We’re in a place now where we can open that door, expose and challenge injustices,” says former Justice Minister Christiane Taubira, in Bondy. “France would not be what it is today without this story. [The film] is a pedagogical tool to teach the next generation. We can’t keep them away from history.”

France’s colonial troops

The tirailleurs sénégalais were formed in 1857 by Gen. Louis Faidherbe in an effort to strengthen France’s military. Known at the time as the “Black army,” the colonial soldiers were first recruited from Senegal, and later across all of French colonial sub-Saharan Africa.

As well as fighting during World War I – when 30,000 died – around 140,000 African soldiers fought under the French flag in World War II. During the First Indochina and Algerian wars, the tirailleurs represented 16% and 5% of the French army respectively, before their corps was dissolved in 1962 with the end of French colonial rule.

While the tirailleurs eventually lived and fought alongside French soldiers, they – like all Africans from the colonies – did not have the same rights as French citizens. In WWI and WWII, they wore a distinct uniform and were billeted in separate sleeping quarters. Considered “less intelligent” than French soldiers, they were most often sent to the front lines – accounting for their extraordinary loss of life in combat.

And yet, historians say it would be inaccurate to paint a picture of all tirailleurs as victims.

“Some tirailleurs were conscripted, at times violently, but others joined voluntarily,” says Claire Miot, a history professor at Sciences Po in Aix-en-Provence. “There was prestige in joining the army – you ate and lived relatively well. Certain tirailleurs wanted to save the homeland. All types of situations existed.”

“Still, the tirailleurs were colonized peoples, used for the purposes of colonizing and oppressing others,” says Dr. Miot. “That’s where the true paradox lies.”

Nonetheless, dissent within the ranks was relatively rare. Even during the Algerian War, when some questioned the tirailleurs’ allegiance to France, loyalty rarely wavered.

“There were fears that there would be a kind of Muslim solidarity between the tirailleurs and the Algerians, but this never happened,” says French historian Anthony Guyon. “They were fully integrated into the French army and fought to win French territory. But later, they weren’t given the same recognition.”

Second-class soldiers

Once France’s African colonies gained their independence in the early 1960s, the tirailleurs were sent home and left in administrative limbo. While some stayed in their home countries, other settled in France; none of them received a pension more than half as big as their French comrades in arms.

It wasn’t until 2006, on the back of the film “Indigènes” – which recounts the story of North African soldiers who fought for France in WWI – that President Jacques Chirac rectified that.

But despite their service to the country, the tirailleurs were still not officially French. It took the persistent work of Bondy politician Aissata Seck, herself the granddaughter of a Senegalese tirailleur, to push for that right. In 2016, then-President François Hollande finally granted 28 former tirailleurs French nationality.

Even then, the former tirailleurs were required to live at least half the year in France to be eligible for their pensions. That put veterans like Mr. M’Bodji in a situation where he spends half the year in Senegal and the other half here in Bondy, a suburb of Paris, where he lives in a men’s hostel with a half-dozen other tirailleur veterans. They each have a 32-square-foot bedroom with a toilet and share a kitchen. “In Senegal, we have a big house, family to help cook and shop. ... Here we have to do everything ourselves,” says Mr. M’Bodji. “Everyone is very nice to us, but it’s difficult for us here. We’re old and tired.”

On Jan. 5, Mr. M’Bodji and his fellow veterans – of whom there are around 40 still living across France – won a victory. Just as “Tirailleurs” hit cinema screens, the French government announced that it would finally allow the former soldiers to receive their €950 ($1,030) a month French pensions even if they lived in their countries of origin.

“France has trouble dealing with this part of history because it brings up a lot of shame: men who were forced to fight – and died – for a territory that wasn’t theirs,” says Ms. Seck. “But this is part of our history and even though it’s tragic, we must commemorate these men and women. We need to constantly challenge politicians and remind them of the importance of their story.”

That has meant providing justice for the tirailleurs at both an administrative and a symbolic level. Though it has been slow, recognition is coming. Last year, a nonprofit in Paris staged a monthslong exhibition dedicated to the tirailleurs, and in March, the Porte de Clignancourt intersection will be named after them.

“Remember us”

Director Mathieu Vadepied says he hopes his film can help pull the tirailleurs’ story out of the shadows and serve as an educational tool for young people. In France, where questions of identity and a sense of belonging have been at the heart of turmoil in recent years among children from post-colonial Africa, “Tirailleurs” provides an opportunity to shift mainstream discourse.

“The tirailleurs‘ story might not be well known in France, but for most African families, we know someone who fought,” says Kinsi Agbangbe, in Bondy, whose great-grandfather left Benin to fight for France in WWI. “In Africa, our stories are shared orally; they’re not written down, so they get lost. What we read in history books should be written by those who lived the experiences, but this isn’t always the case.”

At the end of the film, star Omar Sy’s haunting voice resonates across a black screen: “Remember us.” It’s a message that the remaining tirailleurs, four of whom attended the film screening at the Bondy cinema, hope the French public will retain.

But for now, 95-year-old Yoro Diao is focused on the near future and spending his remaining years in his native Senegal.

“I have enjoyed living in France. I grew up feeling French,” says Mr. Diao, in a stiff black suit and white Kufi hat. “But I have my wife, 12 children, grandchildren, all back home. And there is some nostalgia for them to see their grandpa.”

In Valley of the Kings dig, an all-Egyptian team makes its mark

For decades, as the world’s leading archaeologists dug into the rich history buried in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, Egyptians were the laborers, never the discoverers. But not on this dig.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Traditionally, in digs in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, the role of ceramicist was filled by a foreign archaeologist with credentials from Cambridge or Princeton, not a South Valley University graduate from upper Egypt.

But today, at an excavation in Aten, the recently discovered city at the foot of the Valley of the Kings, Egyptian archaeologists and specialists are filling every role – from extracting and sorting soil to analysis and conservation.

“For once, Egyptians are the leading Egyptologists,” says Dr. Asmaa Ebrahim, painstakingly scribbling down notes about pottery shards. She is one of a new generation of Egyptian archaeologists trained and encouraged by Zahi Hawass, the colorful former director of Egypt’s department of antiquities.

One core team member at Aten is Siham El Bershawy, a Luxor native who preserves and restores everything from papyrus to mummies.

“That feeling when you take items out from the ground in your own site, in your own country, in your own community with your own two hands – you feel a sense of pride as an Egyptian,” Ms. El Bershawy says. “It is your ability and skill that unearthed this item, and now you are the responsible one to protect it for future generations. It is an awesome feeling.”

In Valley of the Kings dig, an all-Egyptian team makes its mark

On a mild, late November morning, almost completely hidden behind the 5-foot-high walls of a sprawling, yellow-gray mud-brick city rising from the ground, a dozen members of an archaeological team survey and brush away soil.

In a nearby tent, carefully holding jagged pottery shards in one gloved hand under a lens, Asmaa Ebrahim painstakingly scribbles down notes on the 3,000th piece of pottery.

Traditionally, in this valley, rich with ancient Egyptian history and the iconic archaeological sites to match, the role of ceramicist was filled by a foreign archaeologist with credentials from Cambridge or Princeton, not an Assiut University graduate from upper Egypt.

For decades here, Egyptians were the laborers, never the discoverers. But not on this dig.

“For once, Egyptians are the leading Egyptologists,” Dr. Ebrahim smiles.

As workers brush away dust and sand, a leather sandal pokes out from the ground, strap facing up, slightly sun-dried but looking as if it had fallen off the foot of its careless owner days – rather than 3,400 years – ago.

“This is one of several,” remarks a worker.

Today, in Aten, the recently discovered city at the foot of the Valley of the Kings, a new generation of Egyptian archaeologists and specialists is uncovering new details of daily life in ancient Egypt and with them, newfound feelings of professional pride and overdue respect.

A rare window

Aten, the so-called Golden City, was the residential, administrative, and industrial center of ancient Thebes, dating back to the 18th dynasty and the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III – the golden age of ancient Egypt.

Discovered by chance while this rare all-Egyptian team was searching for the mortuary temple of the boy king Tutankhamen in 2021, it is now providing an ever-widening window into the daily life of ancient Egyptians.

Aten was abruptly abandoned by Amenhotep III’s son Akhenaten, when he transformed ancient Egypt’s religion and moved the capital 240 miles north of Thebes. That means much of the city was left intact as if life was suddenly frozen three millennia ago – Egypt’s own Pompeii.

Bread remains in clay ovens, precious stones are scattered in the jewelry workshop, and sun-dried bricks are neatly stacked in a tiny pyramid waiting to be carted off to build a temple or a palace.

A wavy, zigzag serpentine wall that experts believed was designed to limit Nile floodwaters cuts through the north of the city; at its end in a tent, Dr. Ebrahim holds up a four-handle jug.

“We have bread in an oven; we have preserved meat, a sandal workshop. A complete residential life is depicted here in Aten,” she gushes with enthusiasm, “and it is not so different from our daily life today.”

“This is unique. You won’t find it at any site currently in Egypt.”

Already the team has uncovered seven districts containing homes, a bakery, kitchens, a tailor, a weaver’s loom, a leather tannery, a metalsmith, a sandal cobbler, and a butchery complete with dried meats in jars inscribed with the butcher’s name, “Luwy.”

The team is also uncovering technical clues as to how ancient Egyptians built and furnished some of the wonders of the ancient world.

Its discoveries have included preserved amulet molds, a jewelry workshop, a brick factory, and granite, basalt, and pottery workshops, all of which it believes were used to build and decorate Luxor’s lavish temples and palaces – and craft the ornate treasures that were buried in King Tut’s tomb.

New generation

The discoveries are thanks to a new generation of Egyptian archaeologists trained and encouraged by Zahi Hawass, who is leading the dig at Aten. The colorful and bombastic former director of Egypt’s department of antiquities used his public persona as “godfather” of Egyptian antiquities to help bring along 500 young specialists to staff all-Egyptian excavation teams.

Dr. Ebrahim is one of dozens who studied archaeology and Egyptology in Egypt and then, at Dr. Hawass’ urging, went abroad in the 2010s to work and train to gain technical expertise that Egypt lacked – in restoration, conservation, pottery analysis, carbon dating, and surveying.

Now they are back leading digs like this at Aten, grabbing headlines and changing the way the world looks at ancient Egypt.

“Our role as Egyptians cannot only be serving foreigners and bringing them coffee and tea while they write books and make films and we do nothing,” Dr. Hawass says as he walks along Aten’s serpentine wall. “We needed to gain the technical expertise that we relied on foreigners for.”

“As a young man entering a bookstore, I never found a single book on Egyptology written by an Egyptian. All our work depended on foreigners, and they took all the credit,” he says. “But now we are a complete scientific team.”

Although recent years have seen more joint international-Egyptian teams, this excavation is one where every role – from extracting and sorting soil to analysis to conservation – is done by an Egyptian, with eight experts overseeing two dozen workers.

One core team member is Siham El Bershawy, a Luxor native who grew up a few miles away from the Valley of the Kings and now preserves and restores everything from papyrus to mummies at Aten.

“That feeling when you take items out from the ground in your own site, in your own country, in your own community with your own two hands – you feel a sense of pride as an Egyptian,” Ms. El Bershawy says as she adjusts the humidifier on a child mummy encased in glass in a tomb-turned-storeroom.

“It is your ability and skill that unearthed this item, and now you are the responsible one to protect it for future generations. It is an awesome feeling.”

Earned respect

It is a recognition for Egyptian archaeologists that has been decades overdue.

Here in the Valley of the Kings, the names of foreign archaeologists still echo from history, such as Howard Carter, the Briton who excavated the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1922 and whose residence in Luxor is preserved as a top tourist destination.

In Aten, 2 miles west of the Carter House, this all-Egyptian team is expanding a discovery that many say rivals King Tut’s tomb, earning accolades from academics and listed as one of the top 10 discoveries of 2021 by Archaeology Magazine.

“The real mark we made in this city is to show for the first time the role of the young Egyptians who are leading in archaeology and Egyptology,” says Dr. Hawass.

Meanwhile Dr. Hawass’ second Egyptian team, working in Saqqara, south of Cairo, last November discovered the funerary temple of Queen Nearit and 50 ornate wooden sarcophagi dating back 3,000 years to the New Kingdom – the earliest tombs ever discovered in that region.

“Two decades ago, we couldn’t compete with international teams. But now foreigners look to us with respect. For the first time we are seen on the same level as Western archaeologists,” Dr. Hawass says.

Among the most recent discoveries in Aten are five undisturbed tombs and five 4-foot-tall sealed jars at the edge of their excavations.

Dr. Hawass is planning to open one of the tombs this February and is continuing fundraising to extend excavations west of the city, of which so far an estimated one-third has been excavated.

Search for a queen

The team has also uncovered a clue he believes may lead it to the lost tomb of Queen Nefertiti – a name.

“Smenkhkare,” the name of a mysterious pharaoh who ruled briefly between Aten and King Tut, was found on multiple inscriptions in Aten.

Egyptologists are divided on the figure; some believe Smenkhkare may have been a brother to Tutankhamen or a hitherto unknown co-regent with Akhenaten.

Dr. Hawass is of the camp that believes Smenkhare was a name assumed by Nefertiti after her husband Akhenaten’s death as she ruled briefly as pharaoh.

While a separate British-Egyptian team is guiding a search for the lost queen’s tomb farther west in the Valley of the Kings, Dr. Hawass’ team believes that by following this clue, they may find it one day near Aten.

Even if future excavations do not lead to major breakthroughs, Aten has already made a major contribution to Egyptology – and for Egyptian archaeologists to be seen as peers.

“We are uncovering and preserving these items for the entire world, just like Western experts do,” says Ms. El Bershawy, the conservationist. “This is more than a job. This is a calling. And we are answering this call and being recognized.”

Reporter’s notebook

Cold journey. Lasting joy. My trek to see the northern lights.

Our reporter treks through Alaska to see the aurora borealis. Her journey takes her though dark and cold, for a fleeting splendor of light that leaves a lasting joy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

It’s getting close to midnight, and close to my destination – mile marker 133 on Alaska’s Glenn Highway, where I’m on the road to fulfilling a lifelong dream. Tonight, if the forecast app and my guide are correct, I’m going to see the northern lights. The aurora borealis.

When we at last pull over at the designated spot, we are on the edge of a giant meadow. Only scattered evergreens stand between us and the horizon. No light pollution. No mountains to block the view.

“I can’t tell you how much joy I get from seeing the smile on people’s faces,” says my guide, Scott Stansbury of SSP Studio & Gallery. “That’s the reason I do tours.”

Eventually, the lights appear, then grow more glorious each time I step outside. Finally, as if playing a visual symphonic encore, a giant streak of phosphorous green seems to swoop down to the treetops and dollop them with a curlicue swirl. I’m smiling inside and out.

Cold journey. Lasting joy. My trek to see the northern lights.

It’s getting close to midnight, and close to my destination – mile marker 133 on Alaska’s Glenn Highway, where I’m on the road to fulfilling a lifelong dream. Tonight, if the forecast app and my guide are correct, I’m going to see the northern lights. The aurora borealis.

More than two hours ago, aurora tour operator Scott Stansbury of SSP Studio & Gallery picked me up at the Hotel Captain Cook in Anchorage. We cleared the city’s exurbs, and then began a long, lonely, and careful drive in the dark, the headlights of his new Kia minivan cutting a tunnel through black forest, his studded snow tires gripping the icy road with assurance.

As we wind through mountains, a moose suddenly comes into view by the side of the road. Then two more! Later, Scott points to his dashboard thermometer. It’s minus 24 degrees outside. A microclimate. It won’t be that cold when we get there, he promises. Finally, up ahead, Christmas lights twinkle on the left. This is Eureka Roadhouse. Two gas pumps (closed in winter), a population of two dozen, and just a few miles from marker 133.

When we at last pull over at the designated spot, we are on the edge of a giant meadow. Only scattered evergreens stand between us and the horizon. No light pollution. No mountains to block the view. I am Scott’s only client tonight, but whether it’s one person or a bridal party from Japan, the professional photographer and videographer loves to come out here to witness one of nature’s most spectacular shows – and to share it with others.

“I can’t tell you how much joy I get from seeing the smile on people’s faces. That’s worth it right there. That’s the reason I do tours,” he says in his upbeat Texas tones. They seem incongruous this far north, until you remember that most Alaskans come from somewhere else.

I emerge from the van into minus 6 degrees, bundled like the Michelin Man. A bazillion stars sparkle, and the Milky Way pours overhead. What looks like a gray stream of cloud arcs low over the horizon. “That’s it!” says Scott.

Really? That’s it? I spent 13 hours in planes and airports, and then drove 2.5 hours to see a gray streak? “Patience,” he says, good-naturedly. It will get better. Wait till 2 a.m. That’s usually the best time.

He encourages me to get back into the toasty van, which he leaves running, and go to sleep (he provides blankets, pillows, and tilt-back seats). With a Wi-Fi hot spot in his vehicle, he’s got plenty of work to do from his phone. “I’ll wake you when something happens.”

Dog sledding and aurora

Aurora tourism is a growing niche industry in arctic climes. Often it’s combined with winter activities like mushing, ice fishing, snow machine rides, and hot springs. Every year, thousands of tourists stream to Alaska in search of night skies dancing with neon green and other colors caused when electrically charged particles from solar wind collide with molecules and atoms of gas in Earth’s atmosphere.

The heavenly ballet can be seen at Earth’s magnetic poles when it’s dark and skies are clear. Some of the best viewing spots include Fairbanks, Alaska (the area’s viewing season runs Aug. 21-April 21); Canada’s Dawson City, Yellowknife, and Gillam; the southern tip of Greenland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Tromsø, Norway; and the northern coast of Siberia, according to the Geophysical Institute at University of Alaska Fairbanks. The institute’s “aurora forecast” webpage is a great place to learn more about the science of the northern lights and when and how to see them.

Pandemic travel restrictions put aurora tourism in a deep freeze for two years. While business is not yet back to pre-pandemic levels, it’s “going well,” says Kathy Hedges, marketing coordinator for Northern Alaska Tour Co. in Fairbanks, which she describes as the longest-running tour operator in Alaska’s Arctic. The company operates year-round, though the aurora is the main draw in winter.

As aurora guides and scientists will tell you, there’s no guarantee of a sighting. But Fairbanks is a statistically good bet because of its northern location and freedom from coastal clouds, which can be a challenge for Anchorage. Ms. Hedges and others recommend putting aside at least three nights to improve your chances of viewing, with the idea that you’ll be up much of the night each time.

“On its surface, looking for aurora is boring,” she admits. “You stand there, waiting, waiting, waiting.” That’s why companies offer additional activities and packages. Hers includes visiting the Alaska pipeline and dog sledding with a local musher. You can book a one-day drive to a homestead called Joy, or a multinight stay at Coldfoot, above the Arctic Circle.

“About to bust loose”

Scott is proud of his aurora record. He’ll cancel when it’s bad weather or a poor aurora forecast, but on his go nights, he says, “I’ve only been skunked twice in five years.”

He’s got three preferred spots far from Anchorage, and he researches aurora conditions before confirming a trip – including checking with locals to see what they’re observing. He came recommended by the Cook Hotel’s concierge, and his services include photographs of your experience as part of the package.

On the way up, he was checking an aurora app on his phone. “It’s about to explode on us!” he exults. “It’s about to bust loose!”

And eventually, it does. Each time he wakes me and I step outside, it appears more glorious. At first, a honeydew fuzz skitters along the horizon. Another time, a broad green stripe stretches across the sky, anchored by a short tail. “Do you see the red?” Scott asks. He has me look through his camera. It can see more color than the naked eye. When we watch aurora spikes that resemble a picket fence, he tells me those are called “STEVEs.”

Finally, as if playing a visual symphonic encore, a giant streak of phosphorous green seems to swoop down to the treetops and dollop them with a curlicue swirl. I’m smiling inside and out. We can go now.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Ukraine’s other war front wins a few battles

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Ukraine has scored a few battlefield victories – and not only in the war against Russia. Rather, they were on a front just as vital to its independence: a war on corruption.

On Sunday, the deputy minister of infrastructure was arrested on charges of taking $400,000 in facilitating contracts for power generators. The deputy defense minister resigned Tuesday after a news report found the military was paying for food at prices two to three times higher than those in stores. And the deputy head of the president’s office also resigned after he was seen driving a Porsche owned by a businessman. Then President Volodymyr Zelenskyy launched the biggest government reshuffle since the start of the war nearly a year ago.

Like the remarkable fighting spirit of Ukrainians, the people themselves have shown a strong embrace of public integrity. A survey reveals the share of Ukrainians who believe corruption cannot be justified rose to 64% last year, up from 40% in the year before the invasion.

Perhaps no nation has seen such a swift and dramatic turnaround in seeking honest government.

Ukraine’s other war front wins a few battles

In the past week, Ukraine has scored a few battlefield victories – and not only in the war against Russia. Rather, they were on a front just as vital to its independence and hopes of joining the European Union: a war on corruption.

On Sunday, the deputy minister of infrastructure was arrested on charges of taking $400,000 in facilitating contracts for power generators. The deputy defense minister resigned Tuesday after a news report found the military was paying for food at prices two to three times higher than those in stores. And the deputy head of the president’s office also resigned after he was seen driving a Porsche owned by a businessman.

Then President Volodymyr Zelenskyy launched the biggest government reshuffle since the start of the war nearly a year ago. He ousted five governors and several top deputy ministers, many of them under suspicion of graft. “Any internal issues that hinder the state are being removed and will continue to be removed,” he said. “There will be no return to what used to be in the past.”

To keep receiving Western military aid and be ready for foreign help in postwar reconstruction, Ukraine’s leaders have stepped up progress in ensuring clean governance, such as appointing a chief anti-corruption prosecutor. The efforts really started after the protest-driven democratic revolutions of 2004 and 2013-2014. But they accelerated with the start of the war and then an EU decision last June to grant Ukraine candidate status to join the bloc – under tough conditions to curb the country’s historic culture of corruption.

Vigilance by news media and civil society have kept a flame under elected leaders. Yet like the remarkable fighting spirit of Ukrainians against Russian forces, the people themselves have shown a strong embrace of public integrity, accountability, and transparency.

A nationwide survey reveals the share of Ukrainians who believe corruption cannot be justified rose to 64% last year, up from 40% in the year before the invasion. The willingness of Ukrainians to report cases of corruption has increased to 84% from 44%.

Perhaps no nation has seen such a swift and dramatic turnaround in seeking honest government and building a culture of integrity. The reforms implemented so far, says Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, a leading expert on corruption in Europe, will help develop Ukraine as a rule-of-law state, “something the Ukrainians are fighting for against Russia on the front line at the moment.”

In a country that long regarded some people as more equal than others, the war with Russia and the war on corruption have created a new demand for equality. Or as Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser in the president’s office, tweeted, Mr. Zelenskyy’s actions this week against corruption respond “to a key public demand – justice for all.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Balanced government under God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kathy Chicoine

Rather than feeling overwhelmed by division, we can adjust our views and pray to see balanced government maintained by God.

Balanced government under God

A couple months ago, as I looked at the election results for the United States Congress, I found myself staring at the line across my computer screen dividing an almost equal amount of blue and red. The dividing line seemed to shout, “We are a divided nation with no hope!”

But as I studied the line, what I noticed reminded me of something on the playground where I played as a child – the seesaw! When I would sit on one end of it and a friend would take the other end, there was often a need to adjust our positions. One of us would move farther back while the other moved closer to the middle until we found a balance.

That is such an important quality. We need balance in our lives, in our relationships, our economy, and our government. And while finding balance in the government might sound difficult, I’ve found that it helps to identify balance and equality as St. Paul described it: “Of course, I don’t mean your giving should make life easy for others and hard for yourselves. I only mean that there should be some equality. Right now you have plenty and can help those who are in need. Later, they will have plenty and can share with you when you need it. In this way, things will be equal” (II Corinthians 8:13, 14, New Living Translation).

I’ve also thought about what’s most important in any election is getting a deeper understanding of the identity of its nation. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, wrote in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Identity is the reflection of Spirit, the reflection in multifarious forms of the living Principle, Love” (p. 477). Spirit, Principle, and Love are names for God. Knowing what God is and recognizing that we are His reflection, we can better understand how to govern ourselves and find a balance that respects and blesses all. We find the government of man through understanding that we all truly coexist in the kingdom of heaven, where the government of God produces and sustains harmony.

As we achieve this understanding of the real jurisdiction in which we coexist, we can’t help but participate in life in ways that build up, instead of tear apart, individually demonstrating wisdom, equality, compassion, generosity. This includes the willingness to forgive others on a daily basis.

As I prayed about government recently, I realized I could either agree with negative arguments of division, or I could continue to roll up my sleeves, both spiritually and practically, to take a stand for righteous government, informed by the sense of God’s universally just government, which gives freedom and opportunity to all His children.

As I began to identify my own nation through this more spiritual lens, I saw some similarity between working toward a balanced government, and the task set before the children of Israel when Moses encouraged them to enter their new country with wisdom and understanding. They weren’t there just to occupy the land – they were entrusted with obeying God’s laws and demonstrating their spiritual integrity so that neighboring nations would also learn of and appreciate this way of life. Moses said of these God-inspired laws: “Obey them completely, and you will display your wisdom and intelligence among the surrounding nations. When they hear all these decrees, they will exclaim, ‘How wise and prudent are the people of this great nation!’” (Deuteronomy 4:6, New Living Translation).

Not only were these moral laws the foundation for governing the children of Israel, but they have guided future governments throughout the centuries as well. They were established as a means of keeping all people working together and living in harmony, governed by God. These spiritual laws form an unbreakable bond between God and His creation. Our part is to acknowledge and trust this relationship, follow God’s guidance, and express His qualities in ways that promote balance, stability, and productivity, both individually and collectively.

Practicing this higher standard of living, we become more intuitive to recognize God’s all-inclusive, all-pervasive, spiritual peace, in which perfect balance is maintained. We recognize everyone as His creation, embraced in spiritual perfection. We discern God’s love for all humanity and acknowledge each individual’s ability to express the natural tendency toward God-given qualities such as compassion, equality, honesty, and justice.

Just as my friends and I found a balance on the seesaw, we can adjust our stance and agree to trust God to guide voters and those elected to act in ways that keep our country balanced and prosperous.

A message of love

A wrong righted

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at why Germany and Japan, long reluctant to build up their own militaries, are now reconsidering that core part of their modern identity.