- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Little Free Libraries, putting down roots in communities

When San Francisco city officials tried to clamp down on a Little Free Library, a community rallied to defend the book repository.

The city recently informed Susan and Joe Meyers that their Little Free Library required a $1,402 “Minor Sidewalk Encroachment Permit,” reports The Wall Street Journal. The couple’s book box has been a fixture of the Lower Pacific Heights neighborhood for a decade. With the support of neighbors, the Meyerses protested the edict.

“[Ms. Meyers] is looking to help future Little Free Library stewards who want to put up a Little Free Library lending box, but might be scared to, or nervous to, because of the fines that could be incurred,” says Margret Aldrich, director of communications for Little Free Library, a nonprofit organization.

Since 2009, more than 150,000 Little Free Libraries have sprung up in 120 countries – most recently in Afghanistan. The concept behind them is simple: Take a free book, but, in turn, replace it with another. The miniature libraries typically abut sidewalks. They range from birdhouse-size cabinets, to decommissioned British phone booths, to a hollowed-out cottonwood tree in Idaho that is big enough to walk into. The number of new Little Free Libraries surged during the pandemic.

“Folks were looking for a way to connect with their neighbors,” says Ms. Aldrich in a phone call. “It’s kind of showing that we’re all in this together, even when we have to be apart.”

Some neighbors have also banded together to distribute books that their local libraries have boycotted. Last year, HarperCollins dispatched 1,000 banned books to Little Free Libraries.

Following an outcry about the costly permit for the Meyerses’ dollhouselike bookcase, several San Francisco city agencies promised to revise rules that impact Little Free Libraries.

Although some U.S. cities cracked down on the boxes when they started popping up, that’s rarer now. Observes Ms. Aldrich, “Enough people know what the concept is and the positive outcomes that can happen in a community because of the Little Free Library.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Six decades after civil rights, a new era of protest in Nashville

Protests in Nashville this week echo an earlier era of Black Americans speaking out. What began as a call for action on gun violence has broadened – and drawn national attention.

In many ways, the scene in Nashville today feels like a 1960s redux: A younger generation seeking racial equity is pushing for change and upsetting the status quo. At the same time, there are notable differences between the two movements, as well as the political and social context that surrounds them.

While ’60s civil rights activists followed a strict set of rules – dress well, don’t laugh, don’t strike back – a number of today’s activists are brash, using a megaphone in the legislative chamber. After being expelled from the state House of Representatives last week for leading a protest there, and then reinstated yesterday on a wave of public outrage, Rep. Justin Jones called for the Republican House speaker to resign.

Compared to the ’60s sit-ins, the policy goals of the Nashville protests aren’t as clearly defined. They began two weeks ago, focused on gun control. Now they’re also about democracy, civil rights, and restoring “power to the people.” Whether the leaders of Tennessee’s new “Good Trouble” caucus can score larger wins remains to be seen.

“We’re here to disrupt in every single way,” says state Sen. Charlane Oliver. “We know what’s at stake here. We have been beating down the door from the outside for years.”

Six decades after civil rights, a new era of protest in Nashville

The march started in North Nashville, near the home of Z. Alexander Looby, a Black lawyer and city councilman whose house had been bombed the day before. It began as 1,500 protesters, walking silently. By the time it reached its destination – the city courthouse – there were an estimated 3,000.

April 19, 1960 was a turning point for Nashville’s sit-in movement. Since February, students had been trying to integrate the city’s lunch counters. The bundle of dynamite thrown at Mr. Looby’s home convinced the public that the resistance had become more extreme than the protesters. Meeting the marchers outside the courthouse, Nashville’s mayor relented.

Yesterday, more than six decades later, another crowd marched through Nashville. It started as a small protest on the plaza of city hall. By the time it reached the statehouse, it also had surged to a similar size. This time, the marchers were rowdier. They held protest signs. They chanted “no justice, no peace.”

When they reached the statehouse steps, they too claimed a victory: Justin Jones, one of two state representatives who were expelled last Thursday after leading a disruptive protest in the House chambers, was reinstated to his old seat until a special election. The same is expected for Justin Pearson in Memphis tomorrow.

In many ways, the scene in Nashville today feels like a return to the 1960s: A younger generation is agitating the state’s power structure and seeking what they see as justice. At the same time, the movements differ in style and substance, and social context.

Nashville’s civil rights era activists followed a strict set of rules – dress well, don’t laugh, don’t strike back. Today some are willing to be more brash. After his second swearing in, Representative Jones again grabbed a megaphone and called for the Republican House speaker to resign. In the 1960s, segregation offered clear targets for long-term campaigns. The policy goals of today’s leaders in Nashville are less defined. Their protests began two weeks ago, focused on gun control. But they also speak of democracy, civil rights, and restoring “power to the people.”

The leaders of Tennessee’s “Good Trouble” caucus may both soon be back in office and emboldened. But whether they can turn their trouble – and their new national support – into more policy good remains to be seen.

“We're here to disrupt in every single way,” says state Sen. Charlane Oliver, aligned with Reps. Pearson and Jones. “We know what's at stake here. We have been beating down the door from the outside for years.”

Outrage over gun violence

The first protest began three days after a mass shooting at a private Christian school in the city’s Green Hills neighborhood. Around 1,000 demonstrators filled the statehouse lobby and the chamber galleries. That’s when Messrs. Jones and Pearson approached the speaker’s well with a megaphone, leading chants for gun control.

Session didn’t resume until almost an hour later, after the galleries were cleared.

For the two representatives – especially Mr. Jones – this is the rule, not the exception. Their style of politics welcomes disruption. After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Mr. Jones led a protest in the plaza outside the statehouse – for 62 days. The year before, he was charged after throwing a cup of tea at the then House speaker.

“All three of us come with this reputation of agitation and disruption, but also results,” says Ms. Oliver, who helped organize the city’s largest Black Lives Matter rally in 2020 and registered 91,000 Black voters in 2018. “They're threatened by that.”

A week after the recent gun-control protest, the Republican supermajority in the House voted to expel Mr. Jones, and by a lesser margin Mr. Pearson. Rep. Gloria Johnson, who had joined their protest, fell one vote shy of joining them.

Even some prominent Tennessee Republicans say the moves went too far.

“It didn’t even remotely rise to the level of expulsion,” says Victor Ashe, former Republican mayor of Knoxville and former aide to U.S. Sen. Howard Baker. “The consequences from a Republican standpoint were disastrous.”

The lawmakers had broken House rules, he says, but no Tennessee lawmaker had ever been expelled for breaching decorum. And expelling two young Black lawmakers while voting to keep the white woman? To many in Nashville and across the country, this was too extreme.

Filling the vacant seats until there’s a special election later fell to the city governments of the lawmakers’ districts. Nashville unanimously reinstated Mr. Jones yesterday. Shelby County is likely to do the same in Memphis tomorrow for Mr. Pearson. After the Nashville vote, thousands began their march toward the statehouse, carrying protest signs, and chanting “No justice, no peace.”

“Happy Easter Monday, because we are resurrecting a movement across the state,” Mr. Jones said at the rally.

The civil rights era model

When this type of movement took place in the 1960s, its defining quality was its discipline.

The students who led Nashville’s sit-ins trained in nonviolence and studied philosophy. Martin Luther King Jr. called it the best-organized effort in the country.

Their mission was simple and morally unimpeachable. Everyone, regardless of their skin color, should be able to get a sandwich in public. Their tactics too were designed to win public support. Protesters wore suits, so that if they were arrested they would look like they were going to church. They were quiet and polite, for even the white employees they challenged were surely also anxious.

And they were centrally organized. That’s why, after their first victory, they quickly moved on to other institutions: department stores, movie theaters, pools.

There are echoes of that civil rights era and its aftermath today.

To his reinstatement, Mr. Jones wore a light, tailored suit – reminiscent of the sit-in protesters’ Sunday best. He raised his fist in the Black Power salute, famously seen in the 1968 Olympics. Mr. Pearson sports an afro and speaks in the cadence of Civil Rights era speeches.

But at times their tactics – at least Mr. Jones’ – feel less policy focused and more provocative.

At a past protest, Mr. Jones shoved a traffic cone through a truck window when he felt the driver insulted him. At another demonstration, during which the city courthouse was partially set on fire, he climbed atop a police car.

“This has been building,” says Ms. Oliver. “The megaphone moment was the crescendo.”

Leaders with a track record

Ms. Oliver and her allies do care about policy, as well as being heard.

Ms. Oliver is a rare freshman senator with a bill that might become law. Her proposal to limit developers from harassing people to sell their homes advanced from committee with bipartisan support.

Back when he was a middle schooler, Mr. Pearson arranged to speak in front of the Shelby County Board of Education in Memphis. He called for the board to buy books the students needed. The board bought them. More than a decade later, he founded a group in Memphis that successfully fought an oil pipeline that would’ve run through poor, Black neighborhoods.

They’ve had clear policy success. But as state Democrats sense a moment to organize Tennessee’s major cities – even compete statewide again – yesterday’s march still doesn’t hint at how to turn activism into law.

Yesterday’s march rose out of opposition, opposition to Republican political overreach, opposition to loosened gun laws that many say have increased gun crime. For the movement to mature, it will need to find out what it’s for.

Their first policy push will likely be gun control, says Shelby County Commissioner Mickell Lowery. But it’s hard to see that passing in the statehouse – or changing the majority in Tennessee.

“It’s an uphill battle,” says Commissioner Lowery. “Obviously, nothing like that comes easy.”

But this movement doesn’t need to be the 1960s, when activism translated so clearly into success. To Ms. Oliver, challenging the state’s way of doing business is success alone.

“When you know that it is your divine calling to be here, to stand up to the forces that don’t want you here, then I’m okay with whatever the consequences are,” she says.

“As long as I’m standing on the right side.”

Secrets among friends? What leaks reveal about Ukraine-US ties.

Leaked U.S. intelligence documents indicate close coordination between Washington and Kyiv in the latter’s war with Russia, but there are limits. Experts point to Ukraine’s innate distrust of great powers, even friendly ones. The leaks won’t help.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The extraordinary cache of recent and highly sensitive U.S. intelligence documents leaked online offers a window into the U.S.-Ukraine relationship that has been forged by more than a year of war. And not just any war, but one that has morphed into the front lines of what the Biden administration portrays as a defining battle between democracy and autocracy.

Amid such high stakes, the leaks underscore significant cooperation – including how U.S. assistance has moved well beyond providing crucial weaponry to advising the Ukrainians on the optimal targeting of Russian forces.

But mixed in is also a fair dose of mutual wariness. Matthew Schmidt, an expert at the University of New Haven, says Kyiv “has never trusted the U.S.” with running the war for them.

The timing of the leaks is particularly problematic for Kyiv, which is preparing its crucial spring counteroffensive.

“So much is riding on the success of this offensive,” says Rajan Menon, a director at Defense Priorities, a Washington think tank. It should surprise no one, he says, that officials in Kyiv are probably even more secretive now.

“If I were in the Ukrainians’ place,” he adds, “I would be just as careful about revealing sensitive information, no matter who the recipient is.”

Secrets among friends? What leaks reveal about Ukraine-US ties.

The extraordinary cache of recent and highly sensitive U.S. intelligence documents that have appeared these last weeks on social media sites and gaming chatrooms – largely focused on military and diplomatic aspects of the war in Ukraine – includes revelations on friend and foe alike.

In the “foe” column, the leaks include precise and timely details of Russian war planning and suggest deep U.S. penetration into Russian decision-making centers, from the Kremlin to the mercenary Wagner Group.

But then there are the friends – and in particular, Ukraine.

The documents – about 100 pages of what appear to be photocopied (and sometimes altered) intelligence briefings and “secret” reports – also offer a window into the U.S.-Ukraine relationship that has been forged by more than a year of war.

And not just any war, but one that has morphed into the front lines of what President Joe Biden and his administration portray as a defining battle between democracy, national sovereignty, and the rule of international law on the one hand, and autocracy, outside domination, and the rule of the strongest on the other.

Amid such high international stakes, the leaked documents underscore a relationship of significant cooperation – especially notable considering the relatively short period of time over which the intense relations have developed.

For example, some of the leaked information suggests how U.S. assistance has moved well beyond simply providing crucial modern weaponry to advising the Ukrainians – sometimes on a daily basis based on sophisticated satellite imagery – on the optimal targeting of Russian forces and repositioning of Ukrainian forces to evade planned Russian attacks.

But mixed in with that impressive degree of cooperation is also a fair dose of mutual wariness – exemplified on the U.S. side by leaked revelations that Washington spies on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. That “news” drew grumblings and professions of disappointment from Kyiv, but analysts and some U.S. officials say no one should be surprised that the United States is managing its full-bore commitment to Ukraine on the basis of “trust but verify.”

Ukraine’s continuing wariness toward Washington – exemplified by what some U.S. officials describe as a frustrating opaqueness among some Ukrainian officials – has less to do with the U.S. specifically and more to do with a long and difficult national experience with outside powers, regional analysts say.

“It’s not about mistrusting the Americans; it has to do with Ukrainian history and a very strong sense that they cannot be dependent upon some outside hegemon – even a good hegemon,” says Matthew Schmidt, a political scientist with expertise in Russia and Ukraine at the University of New Haven in Connecticut.

What Dr. Schmidt says he’s learned from his time in Ukraine both before and during the war, including recently, is that “the Ukrainian government has never trusted the U.S.” with running the war and internal affairs for them, “and they are never going to,” he says.

“They’ve always been very careful to keep the final decisions – and the real questions they are asking themselves – to themselves,” he adds. “They say, ‘We need this and that weapons system from you to win this, but in the end we have to depend on our own counsel.’”

“Close to the vest”

That perspective is widely shared by analysts who have experience beyond the Ukraine-Russia theater to other conflicts pitting an expansionist regional power against a smaller state.

“Ukraine, like any country facing a mortal threat, is being very careful about the numbers they release and the planning they share beyond very tight circles,” says Rajan Menon, director of the Grand Strategy Program at Defense Priorities, a Washington think tank promoting realist principles and focusing on core U.S. national security interests. “They’re keeping quiet and playing very close to the vest.”

The leaked documents are particularly galling to Kyiv coming when they do – as Ukraine prepares its crucial spring counteroffensive against Russian positions inside the country. Moreover, they appear to reveal a significantly more depleted Ukrainian military than Kyiv has acknowledged.

Kyiv has been particularly tight-lipped on its own casualty figures. One document that appears to have been crudely altered to boost Western estimates of Ukrainian casualties and slash those suffered by Russia has been cited by both pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian bloggers as evidence of a disinformation campaign. Another document, from late February, projects the depletion of munitions for Ukraine’s air defense systems by early May – when a spring counteroffensive would presumably be well underway.

Officials in Kyiv have already altered plans for upcoming military operations as a result of the leaked information, according to some reports. And given the timing, that is not surprising, analysts say.

“So much is riding on the success of this offensive,” says Mr. Menon. “The West is looking for not just Russian failures but Ukrainian successes – and the Ukrainians are very well aware of this.”

Given the very high stakes involved, he says it should surprise no one – even or perhaps especially in Washington – that officials in Kyiv are probably even more secretive now about their plans.

“If I were in the Ukrainians’ place I would be just as careful about revealing sensitive information, no matter who the recipient is,” says Mr. Menon, who will have an essay on the implications of Ukraine’s counteroffensive in the upcoming edition of Foreign Affairs magazine. “It’s not a question of mistrust of the U.S. It’s a reflection of how defense planners operate.”

Pressures on Ukraine

Some worry, however, that officials in Kyiv will react to the leaks – and perhaps the fear that more damaging revelations could be coming – by acting precipitously. It’s just one reason the State Department has launched a global effort to reassure allies over the revelations, including what some officials say is Washington’s assessment that no more leaks are likely to be forthcoming.

“The Ukrainians are under a lot of pressure to finish the war this year,” says Dr. Schmidt, the political scientist, pointing to among other things the political pressures the Biden administration and other Western supporters are facing at home to ratchet down their military and economic support to Ukraine.

“That puts extra pressure on choosing the right time and place for the offensive,” he says. “But if the revelations of their risk points prompt them to be less methodical about their choices, that could be disastrous.”

Dr. Schmidt says that for all the pressure the Ukrainian government is feeling from Washington and other Western allies, of at least equal weight is the “public pressure” internally to move beyond what is perceived as the stalemate that set in with Russia over the winter – as exemplified by the battle for Bakhmut – to tide-turning gains soon.

Indeed, a leaked assessment of fighting in Ukraine’s Donbas region from late February concludes that a stalemate setting in there is likely to “thwart” Moscow’s goal “to capture the entire region in 2023.”

That assessment is now being born out, Dr. Schmidt says, adding that it may have been Ukraine’s aim beginning months ago.

“The strategy seems to be to fight Russia to a stalemate in the Donbas, fix their position there – commit them to that spot – and unleash a totally different style of warfare ... elsewhere,” he says.

What might that be? Dr. Schmidt points to the anticipated deployment of 10 or more fresh brigades coming off of what NATO refers to as “combined arms maneuver” training – or what he describes as “training to fight with more equipment, less manpower.”

An offensive with as many as 50,000 fresh and well-trained troops going up against the mostly poorly or untrained fighters on the other side could be decisive, he says.

And while the timing might remain a closely held secret by a country that has learned to depend most of all on its own counsel, the elements that will make up the offensive – the varied weaponry, the trained troops – will unavoidably be the result of deep cooperation with (and indeed material dependence on) the U.S. and other Western supporters.

How Thomas scandal threatens Supreme Court

Why does the highest court in the United States have the lowest ethical standards? That question has come to the fore after news that a GOP megadonor has been treating a Supreme Court justice to opulent vacations and loans of a private jet.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Once described by James Madison as the “least dangerous branch” of federal government, the Supreme Court is now arguably both the most powerful and the least accountable.

Supreme Court justices hold lifetime appointments. Unlike other judges and elected members of government, they mostly police themselves on ethical and financial issues.

A ProPublica story chronicling decades of lavish presents and vacations bestowed on Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife has dealt a major blow to the high court’s integrity. And it comes at a time when fewer than half of Americans trust the court.

That trust has been declining for years as the court has reshaped American law, often in a direction further to the right than a majority of Americans. Notable examples include expanding the interpretation of the Second Amendment, eroding the Voting Rights Act, and overturning Roe v. Wade. Public distrust and anger have typically focused on specific rulings, however. Now, attention is turning to the court’s overall ethics and transparency – or lack thereof.

“The Supreme Court faces a potential crisis of confidence,” says Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice. “This kind of scandal, unaddressed by the court, only makes its decisions more suspect to more people.”

How Thomas scandal threatens Supreme Court

About 7 in 10 Americans trusted the U.S. Supreme Court when, in 1997, Justice Clarence Thomas disclosed receiving a private jet trip from Harlan Crow.

Mr. Crow hasn’t appeared in any of Justice Thomas’ disclosures since then, but the trips and gifts never stopped, according to an explosive ProPublica investigation published last week.

Chronicling decades of lavish presents and vacations bestowed on Justice Thomas and his wife by the Crow family, the ProPublica story has dealt a major blow to the high court’s integrity. And it comes at a time when, unlike 1997, fewer than half of Americans trust the court.

That trust has been declining for years as the court has reshaped American law in significant ways, and often in a direction further to the right than a majority of Americans. Notable examples include expanding the interpretation of the Second Amendment, eroding the Voting Rights Act, and overturning Roe v. Wade. Public distrust and anger have typically focused on specific rulings, however. Now, attention is turning to the court’s overall ethics and transparency – or lack thereof.

Supreme Court justices hold lifetime appointments, but unlike members of other federal branches – and federal judges in lower courts – they mostly police themselves on ethical and financial issues. Once described by James Madison as the “least dangerous branch” of federal government, the court is now both the most powerful, some experts say, and the least transparent and accountable.

“This is not just a gift here or a gift there,” says Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice. “A right-wing billionaire has been subsidizing the lifestyle, secretly, of Justice Thomas for two decades.”

“The Supreme Court faces a potential crisis of confidence,” he adds. “This kind of scandal, unaddressed by the court, only makes its decisions more suspect to more people.”

The Abe Fortas question

Supreme Court justices are only required to make one financial disclosure each year. They aren’t subject to the code of conduct for federal judges mandating that they avoid “all impropriety and appearances of impropriety.” Recusal from a case where they might hold a conflict of interest is left entirely to their discretion.

In this context, Justice Thomas’ behavior “is very disappointing,” says Kermit Roosevelt, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School.

“But it’s indicative of a larger problem,” he adds. The Justices “are just not subject to any enforceable ethics guidelines, and they act like it.”

History is littered with stories of justices making ethically questionable trips or receiving ethically questionable gifts. Most notably, Justice Abe Fortas resigned in 1969 after a Justice Department investigation found he had accepted lucrative gifts from wealthy friends.

But compared to past controversies, the ProPublica revelations are “definitely worse, by several degrees,” says Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix The Court, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that advocates for transparency and accountability in the federal judiciary.

One 2019 vacation in Indonesia that Mr. Crow subsidized for the justice and his wife, for example, would have cost over $500,000, ProPublica reported. An associate justice of the Supreme Court has an annual salary of just over $285,000.

There are exceptions to the justices’ financial disclosure requirements. Gifts of “food, lodging, or entertainment received as personal hospitality” don’t have to be disclosed, according to the Ethics in Government Act. Justice Thomas and Mr. Crow nodded to the exceptions in statements last week.

“Early in my tenure at the court, I ... was advised that this sort of personal hospitality from close personal friends, who did not have business before the Court, was not reportable,” said Justice Thomas in a statement the day after ProPublica published its story.

In a statement to ProPublica, Mr. Crow said they treated Justice Thomas and his wife “no different” from their other “dear friends,” adding that they’ve “never asked about a pending or lower court case, and Justice Thomas has never discussed one.”

Innocent, if opulent, holidays with friends or not, the relationship has drawn attention to the almost complete absence of ethical scrutiny enjoyed by the nine most powerful jurists in America. Members of Congress, for example, need to disclose most trips they make within a month, according to ethics experts. They’re prohibited from accepting gifts worth over $50.

“The Supreme Court is operating with lower ethical standards than any other federal government institution,” says Virginia Canter, chief ethics counsel at the Center for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

“At the same time, there’s no question they’re absolutely one of the most important institutions in our government,” she adds.

The federal judiciary’s policymaking body updated reporting requirements for Supreme Court justices earlier this year to include stays at commercial properties – such as corporate hunting lodges and ski resorts – and travel by private jet.

And transportation, such as private jet and yacht travel, wasn’t exempted even before the new guidelines, ethics experts say. Those are still much softer than officials in other federal branches of government. And while in the past there may have been a desire to treat justices differently from politicians in this respect, that desire is beginning to fade.

Like many in the legal profession, “I was raised to hold the court in the highest esteem ... and thought that they held themselves to the highest standards,” says Ms. Canter.

“Maybe we were naive in thinking that,” she adds.

Can court’s legitimacy survive the status quo?

Not everyone agrees with this assessment. Indeed, the response to the Thomas scandal has underscored the partisan cloud that has surrounded the court.

Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican and member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, wrote a tweet suggesting the ProPublica story broke because “the Left is furious it lost control of the Supreme Court.”

Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee, meanwhile, wrote to Chief Justice John Roberts on Monday urging him to investigate Justice Thomas’ conduct and “take all needed action to prevent further misconduct.” If the court doesn’t resolve the issue of its ethical standards on its own, they added, “the Committee will consider legislation to resolve it.”

The high court has a track record of resisting calls for increased accountability and transparency.

The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg described a 2006 Senate proposal to create a judiciary inspector general’s office as “a really scary idea” akin to Soviet surveillance. In 2012, the same committee urged the justices to abide by the Judicial Conferences Code of Conduct that governs lower court judges. Chief Justice Roberts replied, “the Court has had no reason to” make that change. In 2018, the chief justice helped shut down a bipartisan judicial reform bill in Congress.

But the court has bowed to outside pressure in the past, as when Mr. Fortas resigned in 1969.

And Chief Justice Roberts does also have a track record of defending the judiciary’s institutional integrity, notes Mr. Waldman, author of the upcoming book “The Supermajority: How the Supreme Court Divided America.”

“Right now the status quo for the Supreme Court is collapsing faith and a catastrophic loss of legitimacy,” he adds. The chief justice’s response to this scandal “is as important as any ruling he’s voted on.”

Justice Thomas is unlikely to resign, and the Republican-controlled House is unlikely to impeach him.

It’s worth noting that, as perhaps the court’s most conservative member this century, it’s unlikely that the justice’s opinions were influenced to any great degree by Mr. Crow’s gifts, argues Professor Roosevelt, from the University of Pennsylvania.

But the effect of these gifts “may be to seal him off [from other] views,” he adds. “The ideological echo chamber you’re in affects your views.”

And all that said, even if the justices’ activities outside the high court aren’t influencing their behavior on the court, it’s becoming increasingly hard to argue that the most powerful court in the country should also have the weakest ethical requirements.

“People [are] waking up to the fact that there is no reason the justices have been exempt from basic accountability measures,” says Fix The Court’s Mr. Roth.

Commentary

Finding hope in early efforts to educate the formerly enslaved

After the Civil War, efforts to educate the formerly enslaved were wide ranging. Remnants of that move toward equality are still evident today, despite debates over which parts of Black history ought to be taught.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When Black people in the South sought education after the Civil War, they found refuge in Freedmen’s Schools, established by the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Decades later, after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Freedom Schools educated Black children in states that defied the desegregation law.

“Free” is the operative word, and this history is startlingly close. The remnants of freedmen’s formal education lie just below the surface of daily life in the South today.

Take Immanuel Institute in Aiken, South Carolina, a shining example of the influence of religious conscience operating on behalf of Black people. The school was founded in 1890 by the Reverend William R. Coles, who came to Aiken with the approval of the Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen. Enrollment hit 300 in 1906.

In neighboring Edgefield County, Bettis Academy and Junior College opened in 1881. It was named after once-enslaved Alexander Bettis, who joined other freedmen to start a Baptist church and then founded the school.

The short, three-year history of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the longer stretch of others’ efforts to educate those recently freed from slavery represents the best of us – government and/or religious institutions collaborating with everyday people in the spirit of civil rights and good conscience.

Finding hope in early efforts to educate the formerly enslaved

Black people in America have long correlated learning with liberation, largely because of the difficulty endured acquiring an education and the opportunity it promised. Even today, the very act of teaching Black children is radical, not just because it often exposes racism, but because it presumes that education is a civil right.

When Black people in the South sought schooling during Reconstruction, right after the Civil War, they found refuge in Freedmen’s Schools, established by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. Commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, it was founded on March 3, 1865, when Congress passed an act to provide resources, including education, to the formerly enslaved. In July of 1866, another bill extended the bureau’s life for two years.

Decades later, after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Freedom Schools educated Black children in states that defied the desegregation law.

“Free” is the operative word, and this history is startlingly – and in my case, personally – close. The remnants of freedmen’s formal education lie just below the surface of daily life in parts of the South today.

As a preteen, I attended Schofield Middle School in Aiken, South Carolina, which was founded in 1871 as the Schofield Normal and Industrial School by Martha Schofield, a Quaker from Pennsylvania seeking to educate formerly enslaved people. It later became a public high school for African Americans and joined the local school system a year before the Brown v. Board of Education decision. It has served as a public middle school since the 1960s.

There’s another building originally created as a school for freedmen only minutes away from Schofield. The Immanuel Institute, which now functions as a cultural center, is a shining example of the influence of religious conscience operating on behalf of Black people.

The school was founded in 1890 by the Reverend William R. Coles, who came to Aiken with the approval of the Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen. Enrollment hit its height in 1906, as 300 students attended, with some living on campus during the week because of challenges in transportation.

And just across the county line in Edgefield stand three buildings that used to belong to Bettis Academy and Junior College, named after Alexander Bettis. Once enslaved, he later joined other freedmen to start a Baptist church and then founded the school. Begun in 1881 to educate Black children, it closed in 1952 and has been listed on the state’s National Register since 1998. One of my early mentors, Abelle Nivens, studied there before starting the Minnie Palmore House, a preschool named after her mother, which I attended.

The short, three-year history of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the longer stretch of others’ efforts to educate those recently freed from slavery represents the best of us – government and/or religious institutions collaborating with everyday people in the spirit of civil rights and good conscience.

Juanita Campbell, the executive director of Immanuel Institute’s modern-day incarnation, the Center for African American History, Art and Culture, remarked upon the importance of the school’s aptly-named legacy.

“Religious organizations, schools, and Congress were making efforts to support African Americans who wanted to get educated,” Ms. Campbell writes in an email. “Immanuel Institute is one of 36 schools funded by Presbyterian missionaries in southern South Carolina. This was an important step towards equality, independence, and prosperity.”

I often hear prominent and successful Black people remark about “standing on the shoulders of giants,” a statement that honors the achievements and sacrifices of our ancestors. I can’t help but think about how many Americans, myself included, owe a debt of gratitude to the mothers and fathers of radical and progressive education.

Of course, this history flies in the face of the current national discussion about the relevance of Black studies and whether we should teach about racism and Reconstruction in schools. Proposals to whitewash history aren’t just dangerous; they recall generations of oppression.

“The landmarks are reminders of a time not so long ago when it was illegal for an entire people to know how to read and write,” Ms. Campbell writes. “They also are evidence of a time in history when African Americans were no longer denied access to education. Denying these rights was just another form of slavery that would have set African Americans back even further.”

The notion of radical and alternative education still prevails, she added – if not in public schools, in cultural centers and community groups.

“While the public schools may be forced to adhere to certain legislative decisions that potentially threaten the future of Black History education, organizations within the community are not bound by those policies,” Ms. Campbell says. “Our future generations have a right to know what their ancestors endured so that they could experience and thrive in freedom.”

Difference-maker

This library quenches the thirst for verse

National Poetry Month comes once a year, but Hiram Sims has created an everyday space for verse: bringing access to joy in his diverse South Los Angeles community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dua Anjum Contributor

From Hiram Sims’ earliest memory, poetry defined his inner world – from songs of praise at his church choir, rap lyrics, Edgar Allan Poe, to – even – Hallmark card verse.

Poetry became his favorite form of expression and, as he matured, he wrote about the Black experience and the struggles of being young and broke. In turn, poetry became his vocation – he writes it, teaches it at as a college professor, and publishes his and others’ work.

Yet he had an anchorless feeling: Poetry sections of libraries were rare, and the poetry scene was borrowed spaces in restaurants, cafes, and bars. It felt like “poetry is homeless because it’s constantly couch surfing,” says Mr. Sims.

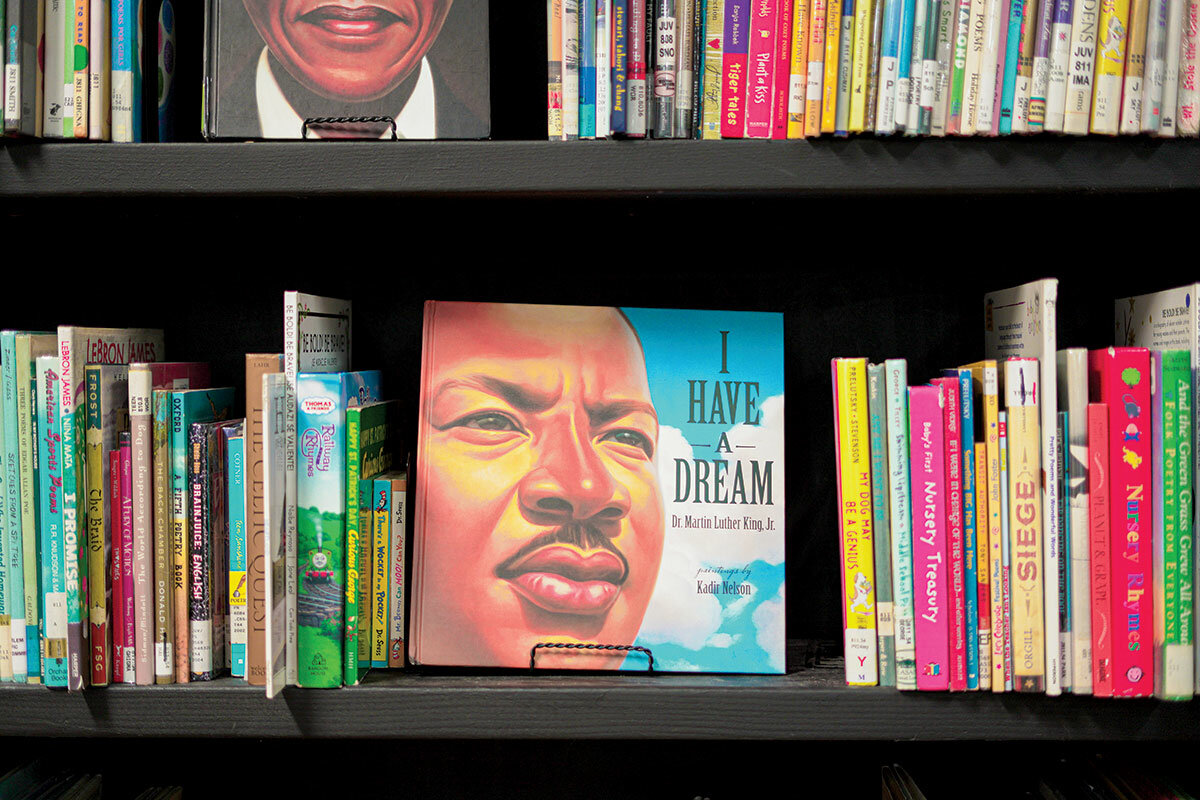

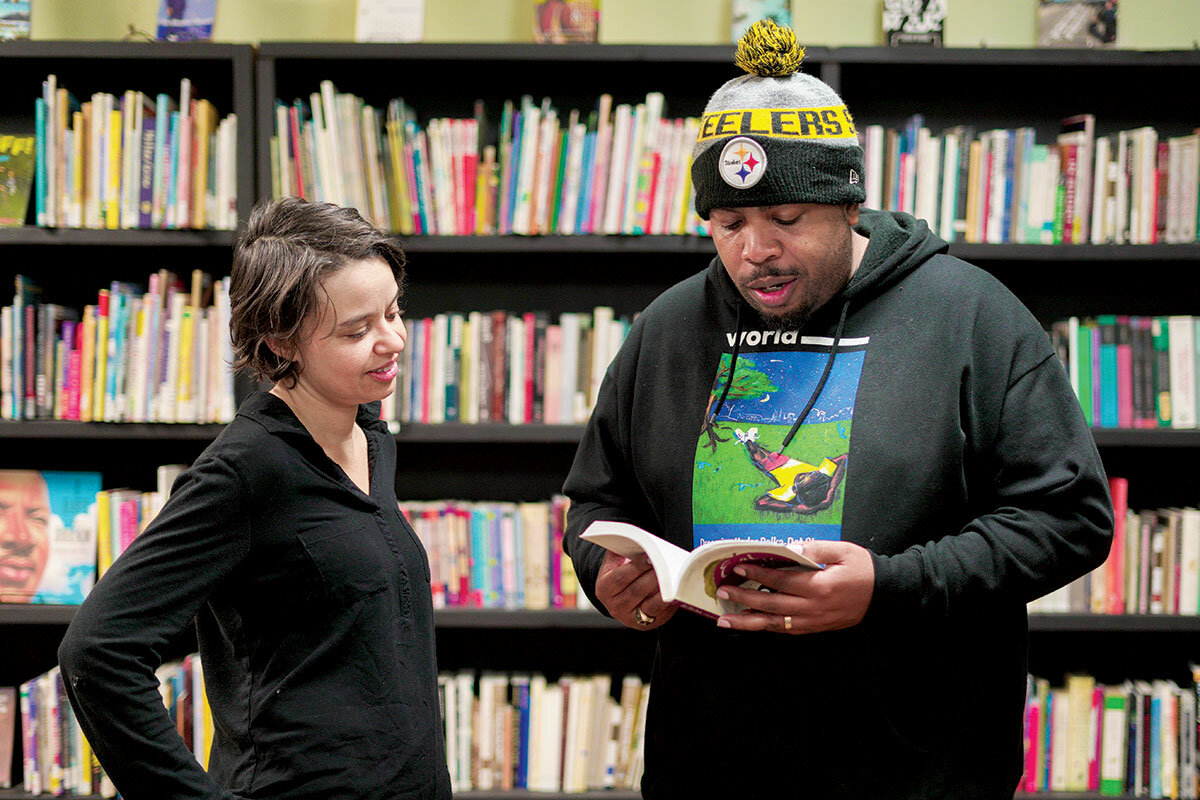

In 2020, he gave poetry a permanent home in his South Los Angeles neighborhood, founding the Sims Library of Poetry, for reading, writing, studying, and performing poetry. The building houses over 9,000 volumes and is busy with events, visitors, and inspiration.

The impact is powerful, says poet David St. John, who mentored Mr. Sims at the University of Southern California: “Young poets, young writers, older poets, older writers have felt seen and recognized in a way that they might not always feel walking into a conventional library.”

This library quenches the thirst for verse

From Hiram Sims’ earliest memory, poetry defined his inner world – songs of praise at his church choir; the rap lyrics of The Notorious B.I.G., Puff Daddy, and Mase’s “Mo Money Mo Problems”; Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” in seventh grade.

“Poetry’s like a frequency that I can hear above all other frequencies,” he says. “It’s like a dog whistle; you know, like other people, they just walk right past it. They can’t even hear it. But when I hear that sound, I pay attention.”

That sound became his favorite form of expression. As a kid, he wrote about candy, his thoughts about God, and a lot of verses for girls at school. In college, while he progressed to mature writing around the Black experience in America and the struggles of being young and broke, witty comic poems remained key to his repertoire. He chuckles recalling a poem comparing Ugg boots to rhinoceros feet. Now, he has published three collections of poetry and frequently writes love poems for his wife.

While it was clear early that his calling was poetry, Mr. Sims remembers having an anchorless feeling: Poetry sections of libraries were rare, and the poetry scene was a series of countless borrowed spaces in restaurants, cafes, and bars. It felt like “poetry is homeless because it’s constantly couch surfing,” says Mr. Sims, who became a creative writing and composition professor at colleges in the area, including his alma mater, the University of Southern California.

In 2020, he gave poetry a permanent home in his South Los Angeles neighborhood, founding the Sims Library of Poetry, for reading, writing, studying, and performing poetry.

The space has evolved into an indispensable gathering place for anyone looking for inspiration, say poets who live nearby. It whimsically invites the public in: “Poetry Lives Here” is painted on a low concrete boundary. A mural pays homage to the dragon fire that poets spit in words. A “Poet Parking Only” sign peeks from a patch of grass.

The spiritual foundation for this landmark came from what Mr. Sims considers a personal triumph: the Community Literature Initiative (CLI), through which he helps poets produce manuscripts ready for publication and connect to presses.

“I was at an open mic and I heard all of these amazing poets. After the show, I said, ‘I’d like to buy a copy of your book,’ and none of them had books,” says Mr. Sims, who has coached poets in publishing now for 10 years in space provided by USC. “And so I felt like it was about filling a void.”

A vision in a suitcase

The Sims Library origin story goes back to a $29.99 suitcase. After assigning his CLI students to read one book of poetry a week, he realized: They couldn’t afford them, and libraries had slim poetry offerings.

So, he fit 80 books from his collection into the purple-brown suitcase, carted it around in his car, unzipped it, and let students borrow poetry collections by living authors, especially local LA poets.

“One of my students said, ‘This is the little Sims library of poetry right here.’ And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s an ... incredible concept,’” Mr. Sims says. “After that, I put all my energy into building that microcosm of the library that I had in my head.”

The idea came to life in his garage at a birthday party-turned-library-launch where Mr. Sims invited every poet he knew, including Kamau Daáood, Lynne Thompson, and Conney Williams. Several poets read their own verse. And people brought boxes full of books: The party started with 300 and ended with 2,000.

Mr. Sims’ mother, Gwendolyn, who remembers her young son loved to read greeting card stanzas at the Rite Aid, was one of the first to donate money. The library continued to thrive with family, community, and foundation contributions of books, cash, and grants. And CLI class tuition also helped.

It was peak pandemic, and the preschool run by his wife, Charisse, closed. The family decided to take over the building as the next iteration of the library. Mr. Sims’ father, Edward, who is a contractor, and his brother Job helped with shelves. Word of another donation drive reached further and book donations came from across the country.

The azure landmark on Florence Avenue boasts an enclosed outdoor space with sofas, tables, and a piano. Inside, there is a cozy room with black velvet couches on three sides and full black bookshelves. Visitors have use of three laptop computers and a printer. There is also a writing room with heartening words from local poets adorning the walls. Stacks of books sit in the librarian’s office because shelf space has run out.

The nonprofit offers more than 9,000 volumes of poetry, says Mr. Sims. “So many of these books are people that live in LA, you know, people in this community.”

Poetry spills out

Open until 8 on Saturday nights, the thrum of activity – from book launches, workshops, and open mics – spills into the neighborhood with singing voices, fingers snapping, and the rhythm of rhyme.

People come “to listen and perform,” Mr. Sims says. “I think the library represents value for a part of people they don’t often share. So people often bring poems from their shoeboxes and folders. It’s so personal with people, so they find joy in having a place for eloquent expression.”

And the library exists only because of community contribution.

“When the first volunteers came in, they expected to come to a library, but then realized, we have to build one,” says Karo Ska, library manager and a CLI writer. For them, the best part is that the library has books that can’t be found elsewhere – pre-1950s special collections, self-published collections, periodicals, local literary journals, and handmade chapbooks.

“The idea of giving back to the community is a phrase that a lot of people use but isn’t always manifested,” says Lynne Thompson, 2021 Los Angeles poet laureate. “[Hiram] is as interested in the work of others and facilitating not only the writing of it but the publishing of it as he is in his own work. And that is quite impressive.”

Poet bridgette bianca, who grew up in the neighborhood without a public library nearby, says: “We are in an area that’s very much Black, very much brown, very much working class. And that somebody built a library here is just fantastic.”

Now, as a community college professor, she uses the library as a resource, encouraging students to explore the poetry collection and attend events for extra credit.

Another poet who held his book launch at the library in December 2022, Jeff Rogers, notes that at the library – surrounded by poetry and people who love poetry – he doesn’t have to compete with the loudness of a bar and “the sound of the espresso machine” while reading.

Permission to be whoever you are

Throughout his life, Mr. Sims says there has always been this unstated – though loud – message that you can’t make a living as a full-time poet. But, with community support – particularly from the poet David St. John, who mentored Mr. Sims at USC – Mr. Sims says he learned to, as poet Mary Oliver wrote, “Let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.”

“So,” he adds, “that’s what’s happened in my life. I like to write poetry. I publish poetry. I teach poetry. That’s how I buy Happy Meals for my children.”

That has a big impact on the poetry community, says Professor St. John: “Young poets, young writers, older poets, older writers have felt, seen, and recognized in a way that they might not always feel walking into a conventional library. I think they’ve experienced a really unusual sense of permission to be whoever they are.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Choices in forgiving debts

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Last year, a committee of international lenders, led by France and China, reached what was hailed as a groundbreaking agreement to ease the debt burden of Zambia. The deal was supposed to mark a new era of cooperation among creditors at a time when roughly 60% of low-income countries face debt crises.

The deal soon ran into delays, however, as Beijing has demanded that multilateral lenders like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) absorb more of the losses of debt restructuring. That’s a nonstarter for Washington and its European counterparts. They argue such an arrangement would simply enable debtor nations to use those savings to pay down their loans to Chinese creditors.

Resolving that impasse is a key focus this week in Washington for talks on reforming the World Bank and the IMF. On the surface, those talks are about creating new lending models to help poorer nations cope with global disruptions like climate change and pandemics.

But there’s a deeper question at stake in the attempt to harmonize Western and Chinese lending practices: Are values such as individual dignity universal and, if so, should they determine global rules on topics like debt? Or are global rules simply a contest of the competitive material interests of rival nations?

Choices in forgiving debts

Last year, a committee of international lenders, led by France and China, reached what was hailed as a groundbreaking agreement to ease the debt burden of Zambia, the first African country to default on its loans during the pandemic. The deal was supposed to mark a new era of cooperation among creditors at a time when roughly 60% of low-income countries face debt crises.

The deal soon ran into delays, however, as Beijing has demanded that multilateral lenders like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) absorb more of the losses of debt restructuring. That’s a nonstarter for Washington and its European counterparts. They argue such an arrangement would simply enable debtor nations to use those savings to pay down their loans to Chinese creditors.

Resolving that impasse is a key focus for government officials and other stakeholders gathered this week in Washington for talks on reforming the World Bank and the IMF. On the surface, those talks are about creating new lending models to help poorer nations cope with global disruptions like climate change and pandemics.

But there’s a deeper question at stake in the attempt to harmonize Western and Chinese lending practices: Are values such as individual dignity universal and, if so, should they determine global rules on topics like debt? Or are global rules simply a contest of the competitive material interests of rival nations?

At a meeting of the Chinese Communist Party in February, leader Xi Jinping characterized his country’s development model as a “brand new form of human civilization” – a “path to modernization that [falls] on the shoulders” of the state.

In recent years, China has become the most prominent national lender of last resort to poorer countries in distress. By the end of 2021, a Harvard study found last week, China had issued 128 emergency loans – to 22 debtor countries – worth $240 billion, many on commercial terms. Only the IMF remains a larger creditor. As China has sought to export that development model through aggressive investment and lending, however, its practices have been shrouded in secrecy. Debtor nations must sign nondisclosure agreements.

The lack of transparency has complicated attempts to seek debt restructuring arrangements that share the costs equitably among lenders. It has also amplified distrust, prompting Samantha Power, head of the U.S. Agency for International Development, to observe recently in Foreign Affairs: “In contrast to the approach of autocratic governments, we showcase the potential benefits of our democratic system when we provide assistance in a fair, transparent, inclusive and participatory manner – strengthening local institutions, employing local workers, respecting the environment, and providing benefits equitably in a society.”

For decades, the goal of international development was poverty alleviation. Now in the context of climate change, argues the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “the challenge is increasingly one of insecurity.”

Ajay Banga, President Joe Biden’s nominee to head the World Bank, amplified that concern in a talk at the Center for Global Development last week. “The aspirations of people around the world, those are universal,” he said. “But we live in a world of greater polarization and extremes.” The imperative of development, he said, was protecting the dignity of all people, “particularly young people and women, who should be not only encouraged but ... empowered to reach for any opportunity that they desire.”

While the share of people living in poverty worldwide has fallen, the percentage of people facing food insecurity has risen. Disruptions like changing weather extremes and the war in Ukraine have underscored that global prosperity is increasingly a shared concern. Resolving the fundamental issues in debt relief is urgent.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What’s truly in control of us?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

We’re all empowered by God to resist unhelpful impulses that don’t reflect our true nature as the good and pure children of God.

What’s truly in control of us?

If we’re struggling with a thought we shouldn’t think that leads to doing something we shouldn’t be doing, it can feel as though our life is out of control.

But what if the real issue isn’t so much a lack of control as a mistaken sense of what it is that controls us? It certainly seems we’re at the mercy of impulses that determine our actions, but it’s worth pondering a thought-provoking idea that suggests that this might not be the case. According to “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, which articulates the Science of Christ that Jesus’ life and healings demonstrated, “All is under the control of the one Mind, even God” (p. 544).

The Mind that is God is, logically, the source of thoughts that are godly, therefore good. And the gospel record of Jesus’ healings illustrates the outcome of being controlled by such thinking. Health was restored even in those who had been chronically unwell. Jesus proved that God’s benign control was present right where sickness seemed to be. He saw in others what God sees in all: We are each made in the image of God, in whom there is no sickness to be imaged forth. It was Jesus’ clear sense of God being expressed only in the divine likeness that healed.

At all points, then, being God’s image is the reality of our identity. But still, can it possibly be true that God’s control is present even if we’re repeatedly entertaining and acting on impulses alien to our nature as Deity’s good and upright offspring?

It doesn’t feel that way when we’re embroiled in such thoughts and behavior, but there is a way forward to increasingly understand and demonstrate that this idea has validity. The Bible counsels, “Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 2:5). It’s in the human mind that those “thoughts we shouldn’t think” find their home, while the mind that was so clearly reflected by Christ Jesus is the divine Mind with its purely good thoughts. To let that Mind be in us is to increasingly yield up the belief of being governed by a human mind and better understand and accept that we are governed by the divine Mind.

This mental shift is an awakening of thought that comes through Christ, God’s communication to us of good thinking and good acting. Christ is continually urging and enabling us to relinquish the sense of being controlled by thinking that is independent of God for our true Christliness under God’s infinitely sweet control.

Meeting the ongoing spiritual demand for this regeneration is often easier said than done. The impulses, belief in inherited traits, and environmental forces that appear to govern our experience seem to argue aggressively that they determine who we are. But the scientific understanding of Christ enables us to submit to the things we recognize as being of God and to rebel against things not of God. Through this, we increasingly uncover the self-control that’s divinely natural to us as the expression of the divine Mind.

No matter how many moments of progress are needed amidst moments when we don’t successfully “maintain this position,” we can stand firm for our capacity to think and act rightly, and lean on God’s power to enable us to identify and refute opposite thinking. Be it slow or fast, each such step of spiritual growth is precious in itself. And this growth continues until we are disabused of the belief in the human mind’s ability to usurp Mind’s control over us – or, indeed, the conviction that there is a human mind to compete with the divine Mind. What Jesus was ultimately proving in each healing was that Mind controls all because it is All – the only Mind. “The divine understanding reigns, is all, and there is no other consciousness,” Science and Health says (p. 536).

As Christ-impelled regeneration leads to our demonstration that this divine understanding is our genuine thinking instead of any thought that has led to actions that have shackled us, the behavior itself will also fall away, for good.

Adapted from an editorial published in the March 6, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Spring forward

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow, when we look at the power of memory in Ukraine, and how the country is forging its own sense of independence.