The meeting adjourned soon after the shouting started.

A dozen or so people had come to the city council meeting on a Monday night in late April 2016. And everyone was angry. Tony Goss, a councilman, had called the mayor a “dictator” for firing the city finance director. Mayor Charles Shaw said the director hadn’t done her job.

An audit firm, meanwhile, was discussing the city budget – which was really the problem. The city council was fighting about money because there wasn’t much money to fight about.

Alexander City – this rural town an hour outside Montgomery, Alabama – was collapsing.

There were the mounting lawsuits: for allegedly running a debtor’s prison, for a cop who shot and killed an unarmed Black man, for a police chief – also Black – who said he was unfairly fired.

Then there was the mill, the Russell Athletic mill, which for some 110 years had anchored the local economy. A century ago, its founder, Benjamin Russell, helped bring Tallapoosa County telephone lines, electricity, and its defining geographic feature – Lake Martin, a 64-square-mile reservoir filled by a 1926 dam. People at the time called Alexander City “Benjamin Russell’s town.”

But in 2013, after years of decline and the loss of thousands of jobs, the town’s mill closed. With it went the last few hundred Russell jobs, the core of the middle class, and much of what made Alexander City a town.

So now, in their downtown chambers, there wasn’t much for Mr. Goss, Mayor Shaw, and the city council to do but argue. And argue they did, until arguments became a shouting match, and the shouting match ended in a fight. As Mr. Shaw left, he says he heard a “cuss” at his wife from Mr. Goss.

And Mr. Shaw swung.

He landed several punches before being pulled away. A photo shows him being dragged back by the neck, over folding chairs and a blue carpet.

The next day, Mr. Shaw and his wife, Laverne, who had joined in the fight, turned themselves in to the police. The local paper ran their mugshots in jailhouse stripes, which became an image of the town’s decline. A few months later, the mayor was convicted of third-degree assault and given a year’s probation with a suspended 30-day jail sentence. His wife was acquitted on the same charge.

“I did what any real man would do after being called a dictator and a liar and someone talking to my wife that way,” says Mr. Shaw. “I grew up in the South and was taught to always, always take care of your family, your property, your people.”

Mr. Shaw isn’t a violent man. That night, he says, was the first time he’d thrown a punch in his life, then 72 years.

But he comes from a violent culture. Amid its chaos, Alexander City was the 18th-most violent small town in America in 2018, according to FBI statistics. Nearly every year, Alabama has one of the top three homicide rates in the country. The South is and almost always has been America’s most violent region.

That violence appears in seemingly random murders and brawls, like Mr. Shaw’s. It appears in regionwide organized crime. It shows up in the rural South and the urban South, the mid-South and the Deep South. Perhaps most importantly, it shows up across time.

Over 400 years, experts say, the South has reinvented itself more than any other region in America, from slavery to the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement. It’s gone from a lawless Colonial frontier to the country’s fastest-growing region. And yet, despite its constant change, the South has always stayed violent.

Think of it like an unchecked habit. The American South was built around an economy of violence in slavery, which then made it harder to develop the institutions that deter violence, such as strong schools and courts. Over time, a tendency toward violence became part of Southern culture, consistent even as the region changed.

America has a violence problem. There’s almost no better sign than its mass shootings, such as the recent ones in Nashville, Tennessee, and Dadeville, Alabama – just 15 miles from Alexander City. The repetition has left many Americans feeling resigned to the fact that America is a violent country. But it’s the South that shows how deep the roots of its violence go, and how hard it is to pull them out.

America is the most homicidal rich country in the world, and from its founding, the South has been America’s most violent region.

Colonial Virginia’s murder rates were often more than double those in New England, where homicides have always been rarest in the country. By the 1820s, the murder rate in many slaveholding states was more than twice that of the North’s most dangerous areas – cities like Boston and Philadelphia. Those distinctions survive.

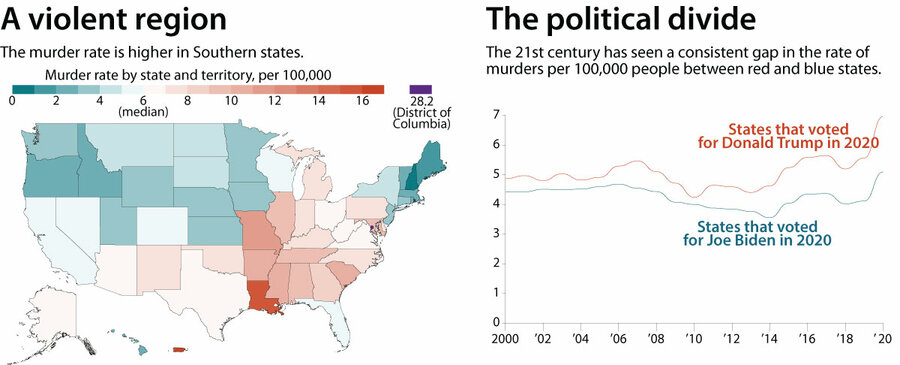

Of the country’s 10 most homicidal states per capita in 2021, six were in the former Confederacy. Four of those were in the top five, some with homicide rates more than 10 times some states in New England.

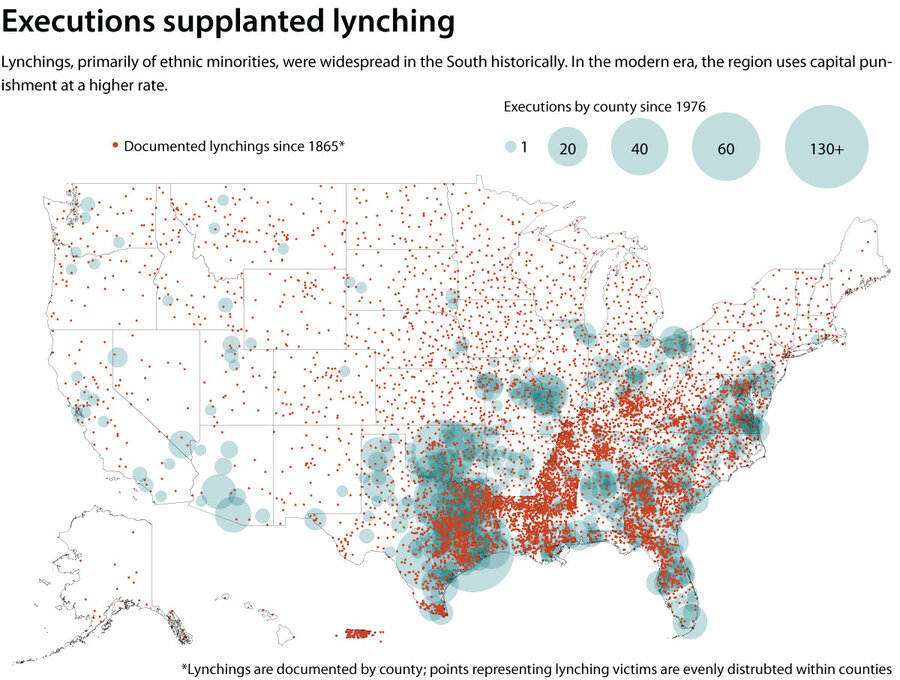

Nearly every Southern state has a stand-your-ground law, which allows people to legally use force – even deadly force – to defend themselves in public. All but one state in the region permits the death penalty. Seven of the 10 states with the highest execution rates between 1976 and 2020 were in the former Confederacy.

The South’s violence “extends across geography, class, race, and politics,” says Ed Ayers, a historian at the University of Richmond. “But it’s also extended across time to a remarkable extent.”

Over time, academics developed two broad theories. One is that Southern violence comes from Southern culture. That includes racism and “honor culture,” defending one’s reputation through violence – similar to Mr. Shaw’s fight. The other theory is that Southern violence comes from the region’s weak institutions, such as poor education, employment, or policing.

But there’s no separating the two theories. Culture shapes institutions. Institutions shape culture. In the South, both have always bordered violence.

Most clearly, these two forces collide in slavery. Some 12.5 million enslaved Africans traveled the Middle Passage to the New World. Around 4 million enslaved people lived in the South at the start of the Civil War. And there was no more violent, no more influential part of the South’s past than slavery.

In the Deep South, enslaved people worked crops that required sharp, heavy tools that could easily become weapons. Heavily outnumbered slave owners maintained their authority through violence: beatings, starvation, sexual violence, sometimes even execution.

After the Civil War and emancipation, white Southerners kept using violence to intimidate former slaves. Farm labor was restricted to the sharecropping system, which resembled slavery. Over decades, county sheriffs rounded up thousands of Black men with phony charges and trapped them in the convict leasing system – whose chain gangs were often run by former slave drivers.

“The violence that we see after slavery is an extension of the violence of slavery,” says Kidada Williams, a historian at Wayne State University.

Some 4,400 lynchings took place from 1877 to 1950, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, which includes in its count racial massacres. Those lynchings peak in the 1890s and fall after Southern states institute segregation and disenfranchisement.

“The people who create segregation are people at the top, and from their point of view, they are managing race relations by replacing violence with law,” says Professor Ayers.

The legacy of this violence can be measured today.

Areas of the South where lynchings were more common now have higher rates of capital punishment, white-on-Black homicide, and prison admission. States that permitted slavery in 1860 now execute more prisoners. Between 1977 and 2005, some 90% of all executions occurred in former slave states.

One of the things criminologists know about violence is that proximity is often prophecy. The more you grow up around it, the more likely you are to commit it. In some cities, three-fourths of all violent criminals have lengthy criminal backgrounds, says Richard Rosenfeld, an emeritus criminologist at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Call it the Southern cycle. The culture and weak institutions expose the region’s people to violence. A higher exposure to violence makes people – especially young men – more likely to commit it themselves.

On the cusp of the Deep South beside the Mississippi River, Memphis has always been violent. In 1866, it had one of the worst racial massacres in American history. Surrounding Shelby County had the highest rate of lynching in Tennessee. By the 1960s, the city had become known as the “murder capital of the world.”

This is where Ron Johnson grew up, the fifth of 10 boys, in a city housing project.

In 1968, at the age of 5, he watched tanks roll outside his window after the mayor declared martial law. When Martin Luther King Jr. was killed downtown, just a few miles away, he saw his father, who worked in law enforcement, come home and get a gun and leave without a word. He returned two days later to cry in his wife’s arms.

Senior year of high school, Mr. Johnson cradled his best friend as he died after being stabbed 15 times.

In moments like this, Mr. Johnson turned to his mother, nicknamed Duke – a gospel singer known to worship with such force that she would sometimes pass out on stage.

Duke knew how Memphis shaped her sons, especially Ron. He was a fighter. In pickup basketball games at the community center, if someone fouled him hard, he would swing back – kicking out their legs and punching so fast he started calling his hands “lightning.”

She stopped letting Mr. Johnson go there alone, making him bring a brother to supervise. She let him play sports, especially football, where as a free safety he could hit people within the rules of the game. She never let him see her angry.

His senior year, a girl signed his yearbook, “Most likely to be dead before he’s 25.” Mr. Johnson knew who it was by the handwriting – a classmate he’d bullied – and wanted to confront her. Duke told him the same thing as always.

“Don’t worry, baby. She don’t know you like that.”

Mr. Johnson let it go. Soon he left for college on a football scholarship to Tennessee State University, in Nashville. He knew that if he had his mom, everything would be all right.

Americans tend to tie violence to places like Memphis: urban, Democratic, often heavily Black, places where troubles rise to the point of cliché.

Then there are places like Alexander City – called Alex City by locals. The town of roughly 14,600 is rural and nearly two-thirds white. Just over 71% of Tallapoosa County voted for Donald Trump in 2020.

And yet, only two years before, the violent crime rate in Alex City had risen to a level about five times higher than the national average – including cities like Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.

“Here’s a small, rural, conservative town: What the [expletive] happened?” says Jay Shipp, who runs a local roofing firm.

Alex City is not as much of an outlier as it seems. Over the last 21 years, states that voted for Donald Trump in 2020 – mostly rural and almost all of the South – had far higher homicide rates than states that voted for Joe Biden, according to a report from Third Way, a center-left think tank.

Even when rural and urban areas have similar homicide rates, it’s easier to ignore violence when people are more spread out. In cities, one homicide in a neighborhood could make thousands of people feel unsafe. In the country, neighborhoods are far less dense and people often feel less connected to the violence that occurs.

That is, until it overwhelms a town, as it did with Alex City.

Crime began dominating local headlines: A man survived being shot in the head during a home invasion by three men wielding shotguns who stole $2, a resident was killed while mowing his lawn, a reality TV star shot someone after a pool game.

It became for many an identity crisis. In Alex City, strangers introduce themselves when you sit next to them at lunch. Downtown is small and quaint, where hunters come to sing karaoke on Wednesday nights and a yearly jazz fest makes the town feel like Bourbon Street.

To Mr. Shaw, the former mayor, Alex City had been the safest place he knew. At a certain point, he accepted that was no longer true.

“A way of life ended,” says Todd Ford, who grew up near the town’s old mill.

In fact, violence here goes back centuries. Four known lynchings took place in Alex City. Its namesake, Edward Porter Alexander, who brought rail service to the town, was a Confederate officer considered a hero at the Battle of Gettysburg.

That violence continues to appear in people’s lives.

Fifteen years ago, Cordero Robbins was at a convenience store when he was hit with crossfire during a shooting. It cost him a full college scholarship to play basketball and months of recovery.

After exiting the hospital and recovering at his mother’s house, Mr. Robbins was stopped by a sheriff’s deputy – apparently he fit the profile of an armed robber who had stolen from the sheriff’s daughter. It took five hearings for Mr. Robbins to be declared innocent.

“People see this violence and just shrug it off, like, ‘that’s crazy,’” says Mr. Robbins, now a local diesel mechanic in his mid-30s. “But it isn’t crazy. It’s reality.”

The too-common outcome of violence breeding violence hasn’t been Mr. Robbins’ reality, though. Sitting in jail after his arrest, he never felt so angry he wanted revenge, he says. But he did ask God, why me?

“It took some years,” he says, to figure out what really had happened. But in court when his assailant offered an embrace in apology, Mr. Robbins, though caught off guard, went ahead and accepted it.

In the South, violence is neither an urban problem nor a rural problem. It’s neither an old problem nor a new problem. It’s just a problem, in need of a solution.

Days after his family visited to watch him play football his junior year of college, Mr. Johnson was finishing drills on the field when his coach drove up nearby. “Spiderman,” the coach yelled out, using Mr. Johnson’s nickname. “I need you to ride down to the office with me.”

After fidgeting on the way over, Mr. Johnson picked up the office phone and heard his brother’s voice.

“She’s gone, man,” he heard. “She’s gone.”

His mother had just been shot and killed, an accidental target of a shooting near their home. “I just dropped the phone,” he says. Mr. Johnson walked laps in the gymnasium with a teammate who held him up. “I just talked to her,” he kept thinking.

Mr. Johnson fell into the drug trade, then prison, where he spent four years rebuilding his life. He later returned to Nashville and became a group counselor who urged young men away from gang violence. Two years ago, he became the city’s first community safety director.

In mid-March, he walks down the hallway, speckled like Fruity Pebbles cereal, in Napier Community Center, 2 miles south of downtown. Through a set of doors, he enters the building’s pool, the blue water made brighter by his clashing red suit.

Last year, the city paid to install a heater in this pool, allowing it to stay open year round. “Literally, without a doubt, I believe it will save lives,” he says.

This neighborhood is near two of the city’s largest housing projects – both hot spots for violence – where the median income can be as low as one-tenth that of the county average. A pool here, like any resource, keeps people from feeling ignored, says Mr. Johnson, who grabs a handful of mints. They’re Life Savers.

Nashville is a relatively safe city, but its murders are climbing. Since 2020, the city’s homicides have been above 100 each year – around double the yearly numbers 10 years ago. Among midsize counties, Davidson ranked 16th in the nation for gun-related deaths, according to a 2022 study.

The money spent to improve Napier’s pool is part of a $300,000 investment in the area, improving lighting, adding speed bumps to stop drag races, and funding the library.

“We’ve had that support, we’ve had that advocacy and it’s been great,” says Jemeka Usher, who lives nearby. “But we haven’t always had it.”

Mr. Johnson’s job is to help reduce violence, and also to convince people like Ms. Usher, whose two youngest children are in high school, that help is here to stay.

In 1961, Nashville closed all 22 of the city’s pools after an attempt to integrate one near Centennial Park. The others later reopened, but that one was filled with cement and covered with grass, as though it never existed. Now the same city is helping keep a pool open year-round in a mostly Black neighborhood. That’s a message, says Mr. Johnson.

“There’s roots, and you’ve got to dig the roots up,” he says.

After the 2016 fight, Alex City’s local government turned over. Many sitting members didn’t seek reelection. That November, an almost entirely new city council took office, along with a new mayor.

Scott Hardy is one of those members. He decided to run, like some of his other colleagues, after hearing about the fight.

“We had become a joke,” he says.

The new city council began diversifying the local economy, trying to prevent another case of economic free-fall. The town will likely benefit from a project to mine graphite, which sits plentifully underfoot and was recently declared a mineral of national importance for its role in batteries.

In the last several years, as locals began to trust their government again, violence has begun to fall – even as it rose elsewhere across the country during the pandemic.

“It’s been a struggle at times,” says Mr. Hardy. “But there’s been a conscious effort to raise the bar for what Alex City is going to be.”

An hour southwest, Bryan Stevenson hopes the same thing for the rest of the South.

Mr. Stevenson is executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a civil rights organization based in Montgomery. Among its projects, EJI places memorials for victims of lynching in the United States. Its goal is to put up a historical marker at every lynching site in the country. EJI has done so in 100 communities so far, including Memphis and Nashville. It’s an attempt at historical remembrance, similar to efforts in post-Nazi Germany and post-apartheid South Africa.

“Violence doesn’t seem unacceptable because it is part of this long history,” he says. “We entered the 21st century having never really reckoned with the ways in which we have become a violent society.”

Cue the reckoning, which in partnership with the EJI is taking place in the South from Nashville to New Orleans. This work is regional therapy for many scarred by the South’s unwillingness to investigate the region’s history.

But it’s hard for history alone to stop homicides.

Mr. Johnson’s work in Nashville and Alex City’s slouch toward recovery testify to other common causes of crime: joblessness, distrust, inequality, culture. The South still has deep pockets of rural poverty and, in some areas, inept government. Those require a reckoning of their own.

On an afternoon in April, Mr. Shaw is speaking to employees in his appliance shop, founded by his uncle 90 years ago and now covered in vines. Several men languor in the sun on makeshift stools outside a garage bay. The shop is only a short drive from the old city hall, the white office building where Mr. Shaw fought.

It’s been seven years now. And with distance, he concedes that the stress of managing Alexander City’s decline made him more hostile. But that’s not an apology. He doesn’t regret what he did.

“That’s a Southern thing, but it’s also an American thing,” he says. “Would I do it again? Yes, I would.”