- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Wait, we’re arguing about the dress code?

As of this week, U.S. senators can wear whatever they want on the Senate floor, sparking an uproar.

Wait, the government is about to shut down, and we’re arguing about outfits?

But this is about something deeper than a dress code. It gets to standards, and tone, and trust.

So much of Congress is theater. There is a language, choreography, and, yes, costumes. The unwritten rules of congressional theater were being challenged well before Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer issued his edict Friday.

Flip-flops, wigs, and sweaty gym shirts had already made Senate appearances. Democratic Sen. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania has frequently sported hoodies and shorts since his return from being treated for clinical depression, though he would vote from the edge of the Senate floor so as not to break the unwritten rules. Congressional leaders sparked controversy this spring when all but one of them – Mr. Schumer – wore dress sneakers to the Oval Office. Journalists and staffers have happily followed suit.

For some, relaxing dress codes – which are expensive to follow, particularly for young staffers – is a step toward greater equity, enabling people from a wider range of socioeconomic backgrounds to work on the Hill. Many say such diversity makes for better policymaking, as we wrote about last year. (Though Mr. Schumer did not drop the dress code for staffers on the Senate floor, few enter the chamber and the standards in the hallways have already changed.)

But for others, there’s a feeling that from schools to churches to Congress, America is dropping the standards that cultivate – and earn – respect. The least lawmakers can do is look the part, they argue. That could stop the meltdown, if not the shutdown.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

New York’s openness tested by influx of asylum-seekers

New York has a rich history of welcoming newcomers. Faced with its largest migrant inflow since Ellis Island, the city finds itself grappling with how to provide funding and compassion.

-

By Hillary Chura Contributor

New York embodies the immigrant ethos. But buffeted by the most sudden major influx of migrants in modern history, the city finds itself in the position of suggesting that asylum-seekers look elsewhere.

Upward of 113,300 newcomers have arrived since April 2022, many with no place to stay. A unique state mandate requires that New York City supply a bed and essential services to anyone who asks, and city officials are scrambling to provide care. Costs are estimated to top $12 billion over three fiscal years.

New York City is the top destination in the United States for recent asylum-seekers. Many residents argue that New York cannot manage this influx on its own and are unhappy with the leadership of Mayor Eric Adams, Gov. Kathy Hochul, and President Joe Biden – all Democrats for whom this 17-month period has turned into a fiscal, logistical, and political quagmire.

Despite recent anti-migrant protests in Staten Island and Queens, and upstate, most New Yorkers statewide support efforts to house and expedite work permits for migrants, according to polling.

“New Yorkers aren’t anti-migrant; they’re anti-this-situation,” says Don Levy, director of the Siena College Research Institute.

New York’s openness tested by influx of asylum-seekers

Perhaps more than any other American city, New York embodies the immigrant ethos. Built by foreigners, it tends to be particularly accepting of those who want to make it in this country. But buffeted by the biggest, most sudden influx of migrants in decades, the city finds itself in the uncomfortable position of suggesting that asylum-seekers look elsewhere.

Upward of 113,300 newcomers have arrived since April 2022, many with no place to stay. Required by a unique state mandate that New York City supply a bed and essential services to anyone who asks, city officials are scrambling to provide education, medical treatment and more. With costs estimated to top $12 billion over three fiscal years, left-leaning New Yorkers are experiencing the tension that those in red border states have railed about for years.

New Yorkers are never ones to shy from an argument, and the arrival of so many migrants has sparked intense debate – from protests in Queens to vociferous discussions in neighborhood social media groups. Ten protesters were arrested Tuesday for blocking a bus of asylum-seekers on Staten Island. Residents have found themselves at odds over what local leaders should do, even as most New Yorkers statewide support efforts to house and expedite work permits for migrants, according to polling.

“New Yorkers aren’t anti-migrant; they’re anti-this-situation,” says Don Levy, director of the Siena College Research Institute, who polls state residents on politics, culture, and social sentiment.

Some city residents argue that as a self-declared sanctuary city – limiting cooperation with federal immigration authorities – New York is getting what it deserves for being so welcoming. Others lament that the city’s responsibilities toward asylum seekers mean less funding for city services and the Big Apple’s 50,000-strong homeless population.

Many residents argue that New York City cannot manage this influx on its own and are unhappy with the leadership of Mayor Eric Adams, Gov. Kathy Hochul, and President Joe Biden – all Democrats for whom this 17-month period has turned into a fiscal, logistical, and political quagmire.

Top destination for asylum-seekers

More than 60,000 men, women, and children, whom the city says are asylum-seekers, are currently in New York City government care, with another 10,000 arriving each month. Some have slept on midtown Manhattan sidewalks, awaiting placement in the city’s growing network of more than 200 housing sites, including homeless shelters, repurposed hotels, and 1,000-person tent cities.

New York City is the top destination in the United States for recent asylum-seekers, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. Other places led by Democrats also are seeing an increased number of asylum-seekers; the mayors of Chicago, El Paso, and Washington, and the governor of Massachusetts have all declared states of emergency.

Mayor Adams has come under particular criticism for his response. In August 2022, when a handful of busloads were arriving, the mayor welcomed migrants. Now, after rapid escalation in arrivals, he’s announced the issue will “destroy New York City” without more funding than the $1.5 billion promised from Albany and $104.6 million promised from Washington.

Mr. Adams says city agencies may need to cut spending by up to 15% over the next 10 months, reducing public services including sanitation, safety, and education. Meanwhile, he’s under scrutiny from the city comptroller for how he’s spending money, and from the Biden administration for not doing a better management job.

Ernest, a Ghanaian immigrant who works in Manhattan, is underwhelmed by the mayor’s actions. “He was like showing off his muscles – like ‘bring them here.’ Well, they brought them here, and now he’s complaining and saying he doesn’t have the money to deal with it,” says Ernest, who asked to be identified by his first name to protect his privacy. He came to the U.S. in 1997 and received a green card on his fourth try. Ernest disapproves of people who cross without official papers, but he says they should be allowed to work since they’re already here.

Equitable care for newcomers and New Yorkers

Critics say Mayor Adams is helping newcomers at the expense of his constituents. The mayor says he’s legally obligated to aid migrants because of the 1981 consent decree that guaranteed the right to shelter. The city wants a judge to modify the order – saying it was never intended to apply to so many people. Homeless advocates counter that beds should be provided for all.

Some who have experienced homelessness in New York City maintain that not everyone can be served well. Rosa Febo had been homeless on and off for a decade until a few years ago when The Partnership to End Homelessness found her and her daughter a Manhattan studio apartment. She says that she would like to move to a bigger place but immigrants are getting first picks along with services she didn’t receive, such as laundry.

Mayor Adams says forcing New York City to care for all asylum-seekers is inequitable. He wants Governor Hochul to allow the city to send more migrants upstate. So far, she has refused. Activists – upstate, in New York’s boroughs, and even at the mayoral residence in Manhattan – have bitterly protested against having shelters nearby. More than 30 of the state’s 57 counties outside of the five in New York City are trying to prevent Mayor Adams from sending migrants their way, according to the news outlet City & State New York.

Governor Hochul is in a tough spot. Regardless of what she does, she could lose votes should she run for reelection in 2026. Last year, she narrowly beat Republican Lee Zeldin, who campaigned on a tough-on-immigration platform. The implications could extend beyond the state’s borders to Congress, should any of the state’s 15 Democratic House seats flip in next year’s election.

National implications

Governor Hochul and Mayor Adams have joined with leaders of other Democratic cities where migrants have been arriving in calling this a national issue that requires a national solution. They are asking President Biden for financial assistance, the temporary use of federal land for housing, and expedited work authorizations.

The White House, however, cannot expedite work permits. Federal law bars people from receiving work authorization until 180 days after they have filed their asylum applications. Only Congress can change that law, which would be an uphill battle considering lawmakers remain deeply at odds.

What the president could do is issue an executive action that extends parole to more nationalities, says Stephen Yale-Loehr, an immigration law professor at Cornell University. Parole allows certain noncitizens to stay in the U.S. temporarily and apply for work authorization. President Biden expanded a parole process for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans earlier this year.

On Wednesday evening, the Biden administration announced it would allow about 472,000 Venezuelans already in the U.S. to live and work here legally for 18 months by extending them "temporary protected status." New York officials had lobbied for the action, which will allow Venezuelans who arrived in the country before July 31 to immediately apply for work authorization. Gov. Hochul told CNN that around 41% of migrants currently in New York shelters are from Venezuela.

While the Southern border states – and much of the rest of the world – have seen a crush of immigrants for years, it’s only been this past year that Democratic cities have confronted so many migrants, says Professor Yale-Loehr. Migrants are fleeing poverty, violence, and the effects of climate change and are coming from a variety of countries including Venezuela, Ecuador, Senegal, and Mauritania. Observers say that with these problems persisting, the flow to big U.S. cities will only increase.

In response, city and state leaders nationwide could jointly push for a White House conference on this issue as well as develop training programs so recent arrivals will be ready to work as soon as their work permits arrive, suggests Professor Yale-Loehr.

Much attention has focused on migrants who have been chartered to liberal states by the governors of Arizona and Texas to focus attention and political scrutiny on the Biden administration’s border policy. But the vast majority has come up on their own from the border, with migrants either using their own money or getting help from aid groups, Professor Yale-Loehr says.

Kamara, from Mauritania, has been living in a city trailer in Queens since the middle of August. After leaving home, he spent a month on buses traveling 2,000 miles through Central America and Texas before ending up in New York, which he chose because friends had said he would receive shelter here. He says he’s waiting for working papers but in the meantime is working under the table with a friend in Harlem, reselling $2 shirts for a profit.

New York’s immigrant stories

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of European immigrants came through Ellis Island, but they didn’t all stay. Historian Carl Bon Tempo, a co-author of “Immigration: An American History,” says today’s rate of arriving newcomers rivals – and very likely surpasses – those from the city’s past.

Migrants tend to cycle out of facilities once they have hooked up with people from home who can help them get settled, says Dave Giffen, executive director at the Coalition for the Homeless.

“They’re not coming here because they want to live in a shelter. They want to work and live and establish lives for themselves and become part of the community,” he says.

Steven Carpio is a first-generation American whose parents came here illegally from Ecuador 45 years ago, worked hard, and now have pensions. He has been working in city shelters and elsewhere to help unauthorized residents set up bank accounts. He says that he’s not sure if the city can afford to pay for the migrants but that they will be a great asset to this country from a labor perspective.

“You look at who cuts the grass – Spanish[-speaking] people, who does the labor for building homes – Spanish[-speaking] people,” Mr. Carpio says.

Observers say that anti-immigrant rhetoric may be more fierce than it is widespread.

“The vast majority of New Yorkers remember the immigration story of their own family. So when we ask, ‘Should we continue to live by the words on the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor,”’ overwhelmingly New Yorkers say, ‘Yes, yes we should,’” says Mr. Levy, the pollster.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to include the Biden administration's announcement late on September 20 of a temporary legal status for Venezuelans who arrived in the U.S. prior to July 31.

Could four-day weeks lead to more progress for students?

What role does time play in student success? Educators are expanding and contracting school days and weeks, looking for a mix that allows instruction and young people to thrive.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

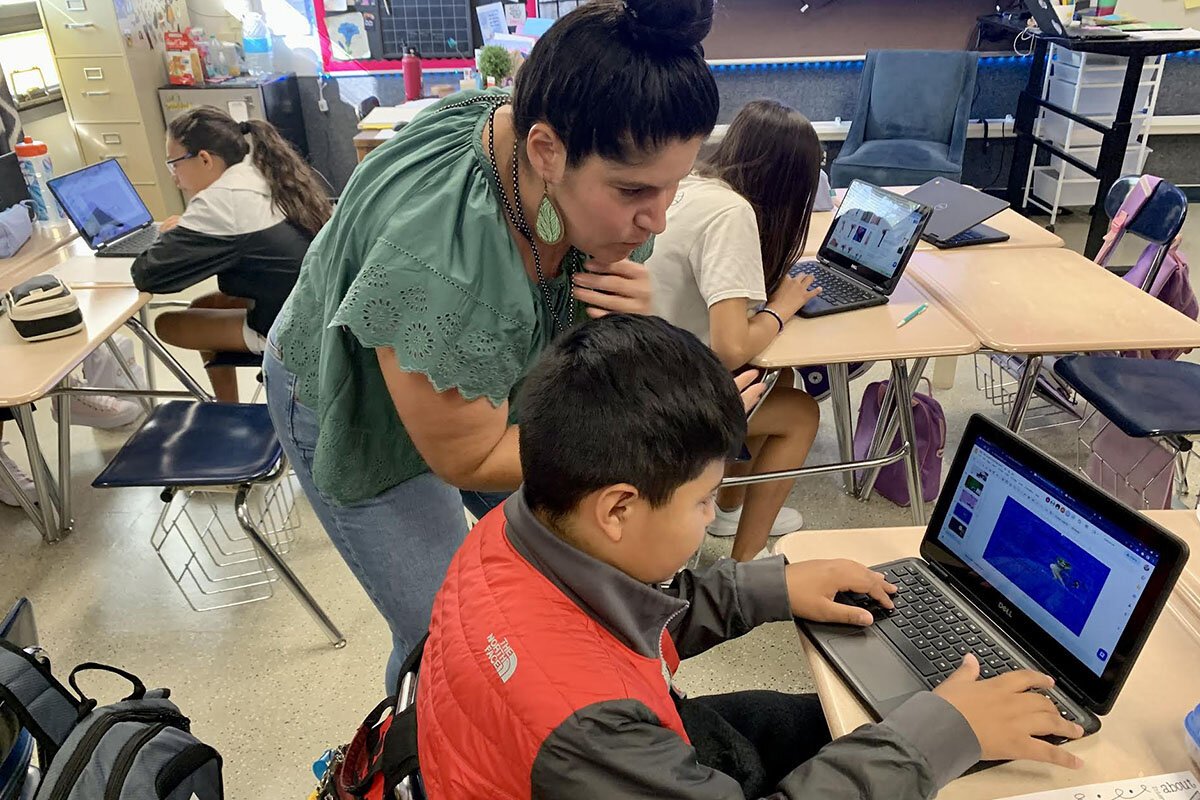

Inside her classroom in Elko, Nevada, Sarah Blois reads her sixth grade students’ responses to a writing prompt about their weekend plans. They range from playing Fortnite to traveling for softball games.

Ms. Blois supported her district’s recent move to a four-day school week, enabling Friday to essentially become a mental health day.

“I found in my class, a lot of kids were already taking Fridays for mental health and missing instruction,” she says.

Across the United States, school districts have been grappling with a surge in chronic absenteeism, the lingering academic fallout from the pandemic, and ongoing staffing shortages. In search of a solution, education officials have been tinkering with time schedules. Some are adding hours or days, creating a longer runway for learning. Others are rearranging hours to make a four-day week possible under the belief that it will yield higher-quality learning.

The time experiments will take just that – time – before educators can definitively say whether the changes improve classroom conditions and academic outcomes.

“Part of me was like, ‘Yay, I won’t be so far behind,’” says Bryleigh Cervantes, 17, who plays three sports and would often miss Fridays while traveling for games. “And then another part of me was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I have to be at school even longer now.’”

Could four-day weeks lead to more progress for students?

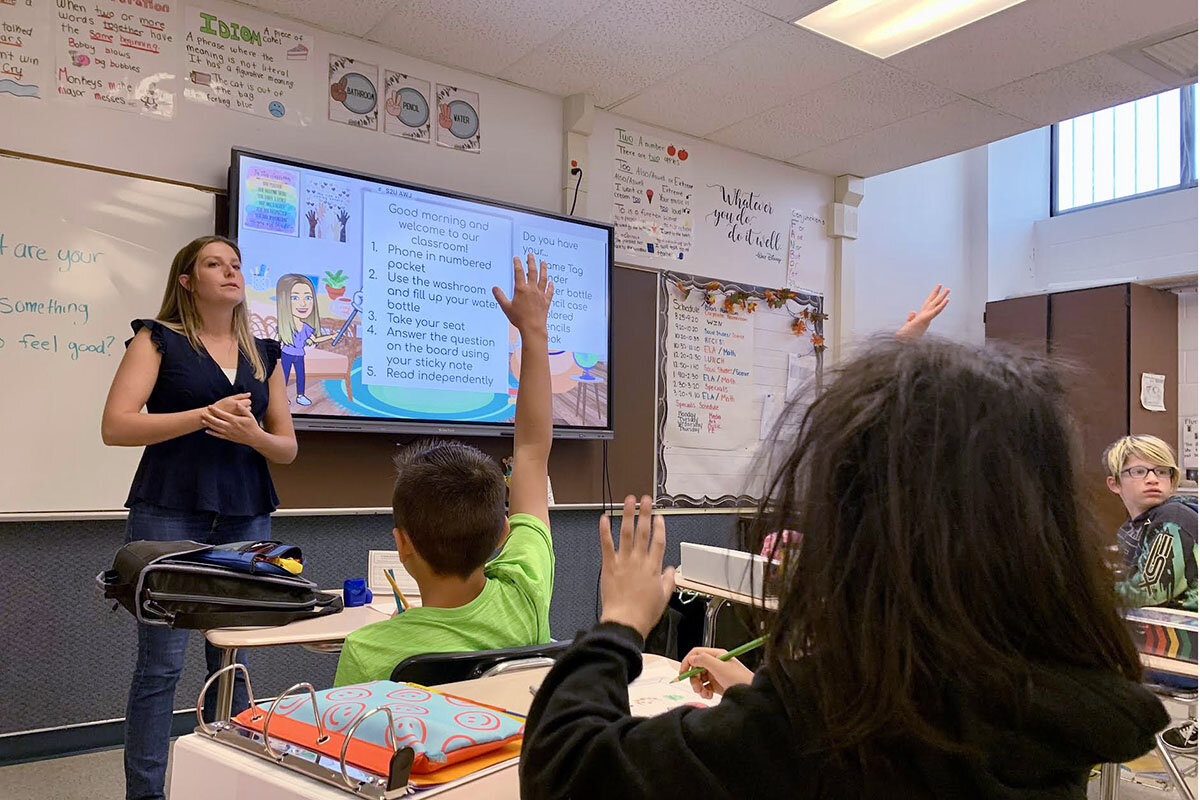

On a Thursday morning in late August, students shuffle into Flag View Intermediate School. Parents wave goodbye, buses rumble away, and the vice principal, Jeffrey Revier, offers a greeting laced with a reminder.

“Good morning. Have a nice last day of the school week.”

His comment elicits smiles, nods, and a few startled glances. It’s the first week of the new academic year. For members of the Elko County School District, that means a major schedule change: a four-day school week.

The northeastern Nevada district, which serves 10,000 students in two time zones, slashed Fridays and lengthened the four school days after a teacher-initiated request gained community backing. It’s a gamble rooted in the theory that if students and staff have an extra day to rest, recharge, and take care of household chores, they will show up more eager to teach and learn.

Inside her English language arts classroom that morning, Sarah Blois reads her sixth grade students’ responses to a writing prompt about their weekend plans. They range from playing Fortnite and cuddling the family cat to sleeping in and traveling for softball games.

Ms. Blois supported the move to a four-day school week, enabling Friday to essentially become a mental health day.

“I found in my class, a lot of kids were already taking Fridays for mental health and missing instruction,” she says.

Across the United States, school districts big and small have been grappling with a surge in chronic absenteeism, the lingering academic fallout from the pandemic, and ongoing staffing shortages, among other challenges. With test scores showing that American students are still behind more than two years after the lockdown ended, and a mental health crisis affecting more than a third of high schoolers, the problems facing America’s education system are profound, if not existential. In search of solutions, education officials have begun rethinking the structure of the academic calendar itself. Some are adding hours or days, creating a longer runway for learning. Others are rearranging hours to make a four-day week possible under the belief that it will yield higher-quality learning.

The time experiments will take just that – time – before educators can definitively say whether the changes improve classroom conditions and academic outcomes. Even students are pondering the pros and cons.

“Part of me was like, ‘Yay, I won’t be so far behind,’” says Bryleigh Cervantes, 17, who plays three sports and would often miss Fridays while traveling for games. “And then another part of me was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I have to be at school even longer now.’”

Four-day buzz, and concerns

Gold mining powers the economy of Elko, a city of roughly 20,000 residents near the Ruby Mountains. It anchors a lonely stretch of Interstate 80, situated about three hours west of Salt Lake City and four hours east of Reno, Nevada. Many mining employees or contractors in related industries log four-day workweeks. The schools in the massive county’s more remote areas also operate on a four-day schedule. So it didn’t come as a surprise to district leaders when teachers from Elko and nearby Spring Creek started lobbying for the same schedule.

About 850 school districts nationwide operate on a four-day schedule, up 30% from 2020, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Most are smaller, rural districts, but in recent years, some larger districts have taken the plunge as well.

“You’re hearing more about the four-day models, not only just in education but in other professions across the country,” says Travis Monett, principal of Flag View Intermediate School.

Indeed, results from a ResumeBuilder.com survey created a buzz this summer after 20% of the 600 business leaders who responded said their company already has a four-day workweek. Furthermore, 41% indicated their companies plan to implement a shortened workweek.

But the corporate world is far removed from the classroom, where other factors weigh heavily in these decisions. For some districts, it’s about finances. A condensed school week can translate to less fuel needed for buses or lower utility bills, but cost savings generally don’t amount to more than a few percentage points of the entire budget. Other districts, Elko included, view it as an attractive recruiting tool at a time when teachers can be hard to come by, especially in rural areas.

Elko County Superintendent Clayton Anderson recommended against a districtwide four-day school week for a different reason. He worried about children with disabilities or those who rely on schools for food and support. How would one fewer day in their safe haven or a shake-up to their routine affect them?

“I was just trying to think of everybody across the board and how that might impact certain subpopulations that may not stand to benefit really much at all from this,” he says.

When Mr. Anderson moved to the Elko County School District from the Houston area in 2019, he initially served as a principal in Wells, which was already operating on the four-day model.

“I’ve got four little kiddos and I love spending time with my family, and so it’s good from that standpoint,” he says.

Last fall, the district surveyed students, parents, and staff about the proposed change. Less than a third of parents responded, but of those who did, 70% backed the four-day school week.

Sixty-seven percent of teachers and 74% of students also supported it. Some parents and community members opposed to the plan spoke at school board meetings, citing concerns such as child care.

A Valentine’s Day vote this year by the Elko County School Board sealed the deal. Five of the seven trustees cast supporting votes, approving a four-day week at every school for the 2023-24 academic year.

The change stretches the school day to seven hours and 45 minutes, keeping instructional minutes well above the state’s minimum requirement, Mr. Anderson says. Teacher and staff contracts saw an extension, too.

Additionally, the district will offer Friday meal programs and educational enrichment opportunities at select schools. And if a holiday falls on a Monday, the four-day school week will shift to Tuesday through Friday.

All the while, district officials say they will be keeping a close eye on the numbers: food need, enrichment participation, attendance, and student achievement. It’s a renewed commitment, after plans to track data in the outlying district schools that previously switched to a four-day week fell astray during the pandemic.

“Is attendance improving?” Mr. Anderson says as an example. “Because that was a big pitch from everybody. ‘Oh, we’re not going to miss as much school. We’re not going to take as many days off.’ And so is that a reality?”

More flexibility for staff

Elko High School Principal John Foss remembers a day last year when 23 of his roughly 70 staff members were absent. It kick-started a mad dash to find substitute teachers or other district employees who could cover the classes. Those situations occurred on Fridays, he says, when teachers needed to travel for their children’s sporting activities or schedule medical appointments.

The Elko County School District isn’t an anomaly. The leader of the North College Hill City School District in Ohio noticed a similar pattern last year.

Superintendent Eugene Blalock Jr. says teachers were constantly sacrificing their planning periods to serve as substitutes, and even members of the board office were jumping in to help. Now, the 1,400-student district outside Cincinnati has embarked on its own new schedule.

In North College Hill, students attend school in person Tuesday through Friday. Monday is considered a “blended learning” day, which means students work online at their own pace and teachers lesson-plan, collaborate with their teams, and do professional development.

The district’s support staff provides child care at schools on Monday for families that need the help.

Mr. Blalock says there’s not a rigid structure for online learning because they don’t want students sitting at a computer for hours. Instead, students have assignments to complete on digital reading and math programs. The district has also partnered with local companies and municipalities, he says, to provide older students with job shadowing and internship opportunities.

“Their coursework is basically completed during the four days, so anything that happens on Monday is a bonus,” he explains.

The operating theory is this: If teachers have more time to create high-quality, engaging lessons, students will excel academically as a result. And from a recruitment and retention standpoint, Mr. Blalock says he is hoping to see more teachers staying and coming to work in North College Hill, given the district’s re-imagined school week.

He acknowledges it’s an experiment, but not one he – a longtime North College Hill resident – has taken lightly. He has led the district for eight years and watched his daughters graduate from its schools. After seeing the level of burnout among his staff and its ripple effect on students, he decided it was time to innovate.

Doctors wouldn’t be asked to perform surgeries and lawyers wouldn’t be asked to argue court cases without adequate time to prepare, he says. Educators should be no different.

“I’m betting on my staff to show the professionalism that they have – and they are professionals and we need to treat them like professionals,” he says. “For so long, we haven’t treated educators” that way.

As more districts rethink schedules, Aaron Pallas, a professor of sociology and education at Teachers College, Columbia University, worries about the effects on the youngest learners, whose attention spans may not withstand longer days. On the flip side, he says the four-day model may prevent parents from pulling their children out of class for medical appointments or personal reasons, leading to fewer education disruptions.

He cautions against placing too much hope in shorter weeks until their effectiveness can be studied.

“We can speculate about these different possible outcomes,” Dr. Pallas says, “but we simply don’t have much evidence right now.”

More time, not less

Other districts are moving in the opposite direction, tacking on extra minutes or days to existing school schedules.

Richmond Public Schools in Virginia extended the academic year by 20 days at two elementary schools in a bid to reverse pandemic-related academic slides, according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch. New Mexico lawmakers, meanwhile, passed legislation increasing the number of hours required for student learning.

To meet that threshold, Santa Fe Public Schools added four school days to the year and extended the length of the day by 15 minutes. The district’s superintendent, Larry Chavez, says the magnitude of that change is apparent if measured over the long term: A kindergartner will receive an extra 2 1/2 years of learning over the course of elementary, middle, and high school.

But as far as Mr. Chavez is concerned, instruction doesn’t mean children should be anchored to their desks. Starting this year, every Santa Fe school will have four social-emotional learning days – one at the beginning of each quarter.

“It’s not always just about learning,” he says, referring to traditional academic subjects. “It’s about navigating real-world situations, building relationships, and we found that teachers and students formed a better connection through this type of day.”

When calculating the time schedule to meet the new state law, Mr. Chavez says the district preserved what it considers a crucial work window for staff – a two-hour early dismissal once a week for each grade level. It’s time that the teachers can dedicate to lesson planning or professional development.

What often gets overlooked in time debates, he says, is the instruction factor.

“If your quality of instruction within the classroom is high – it doesn’t matter if it’s fewer days and hours or more days and hours – that’s when you’ll really see the outcomes change,” he says.

“He’ll adjust”

At Northside Elementary School in Elko, the courtyard is filling up with parents and guardians at 3:45 p.m. Dismissal is 10 minutes away.

Elizabeth Gerber expects to encounter a happy but sleepy kindergartner. The nearly eight-hour days leave her daughter, who otherwise loves school, exhausted. Sean Caron’s fourth grade son, who has been diagnosed with Down syndrome, comes home wiped out, too.

“It’s tough on me. I don’t get to hardly ever see him,” says Mr. Caron, who says the schedule change came as a surprise, but he is hoping it gets easier over time. “He’ll adjust and I’ll adjust, too.”

It’s not just the students with yawns and fluttering eyelids.

Rosio Chavez, the registrar at Elko High School, starts her 10-hour workday at 6:30 a.m. She supported the new schedule, but the reality has been tougher than she imagined. Ms. Chavez says the days feel like a scramble to get everything done, especially with 100 new student enrollments and counting.

But the long workdays free up time for errands that, for Elko residents, amount to a day trip. Her plan for Fridays: “I’ll go to Salt Lake [City] and go do my grocery shopping there at Costco.”

The same principle applies for the students. School-free Fridays allow some children to help their ranching families. For others, it means missing fewer classes because of sports. Given the geographic remoteness of many Nevada towns, student-athletes face multihour car rides, often on Fridays, to compete against other districts.

And teachers say the lengthened school days provide extra time for project-based learning, in-depth discussions, and activities that previously got axed or trimmed down, such as silent reading.

“Homework shouldn’t go home because we should be able to finish it all within this class day,” says Veronica De Leon, who teaches English language arts and social studies at Flag View Intermediate School. “Then kids can go and do their sports. Kids can go home and spend time with their families.”

One week in, Bryleigh and her fellow senior classmate, Christian Felix, give an overall positive assessment. Lunch is shorter, but the days don’t feel as long as they thought they would. They’re also not bringing home tons of work.

Still, they wonder whether the four-day week will feel like a grind – as the five-day week did – come January.

“I can see it hitting hard midyear,” Bryleigh says.

How Haiti’s gang violence is reshaping the nation

Gang violence has forced some 195,000 Haitians to move to other parts of the country. It’s sowing fear and disrupting life plans, but for some rural zones and smaller cities, it could be a moment of big opportunity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Lesly Succés Contributor

For the past two years, Haiti has been steeped in alarming levels of violence, largely carried out by armed gangs in and around the capital, Port-au-Prince. The upsurge in kidnappings and killings has forced many to flee, with people sometimes bouncing between temporary shelters.

At least 39,000 Haitians have successfully applied for humanitarian parole in the United States, while nearly 195,000 Haitians have been displaced within their own country.

The broad exodus from Port-au-Prince has sparked fears among people in smaller cities and towns who feel stretched by new arrivals looking for housing or employment. But there are also signs of opportunity, with the reversal of a generations-old trend of brain drain from smaller cities and towns.

“When you have to flee, you don’t always have time to find the right arguments,” says Mirline Azor, an actress, of her split-second decision to leave home late last year for Gonaïves, a small city about 150 miles north of Port-au-Prince. She and her journalist boyfriend, Lord Byron, chose it on a whim, arriving without a home or a plan. Today, they’ve put down roots, found jobs, started mentoring young people, and hope their decision to leave their old home behind was the right one.

How Haiti’s gang violence is reshaping the nation

Lord Byron and Mirline Azor never expected to live anywhere but Port-au-Prince: The journalist and actress loved the Haitian capital’s cultural scene, abundant professional opportunities, and proximity to friends and family. But months of gunshots echoing outside their window and repeated incidents of neighbors being kidnapped were enough for them to uproot.

Moving away from the capital has been a big change, but it’s one that more and more Haitians are making. As violence goes unchecked in Port-au-Prince, displacement within the country is on the rise.

“When you have to flee, you don’t always have time to find the right arguments,” Ms. Azor says of their split-second decision to leave home late last year for Gonaïves, a small city about 150 miles north. They chose it on a whim, arriving without permanent housing or a plan.

The influx of newcomers to places like Gonaïves has meant big changes for local communities and governments. Across the country, public services and housing are stretched as outsiders move to small towns and cities. And locals can feel threatened by their new neighbors; could the violence they fled follow behind them?

But the broad exodus from the capital can also signal opportunity, reversing a generations-old trend of brain drain from smaller cities and towns. As political upheaval and gang violence persist in Port-au-Prince, and tens of thousands of Haitians leave for the United States, Haiti is undergoing a transformation that will impact its development, professional opportunities, and politics.

“Even though we can’t predict what the long-term impact this internal migration will have on Haiti’s future,” it will be important, says sociologist Léo Bien-Aimé, who studies migration.

The “right formula”

For the past two years, Haiti has been steeped in alarming levels of violence, largely carried out by armed gangs in and around the capital. The upsurge in kidnappings and killings has forced many to flee their homes, sometimes bouncing from one temporary shelter to another. At least 39,000 Haitians have successfully applied for humanitarian parole in the U.S., while an even larger portion of the population is moving within Haiti’s borders in search of safety.

There are nearly 195,000 displaced Haitians in Haiti, according to the International Organization of Migration’s July 2023 Haiti Emergency Response Situation Report. The vast majority, some 94%, fled due to gang violence.

“Leaving Port-au-Prince has completely reoriented the direction of my life,” says Mr. Byron, who spent 20 years in the capital. Prior to moving to Gonaïves, the couple lived in Lilavois, a neighborhood known for its lush vegetation and for being peaceful.

Even with the rise of insecurity in Port-au-Prince at the beginning of 2021, Lilavois was still seen as a place of retreat.

Then, in the spring of 2022, two gangs eager to extend their territory began fighting each other across the northern neighborhoods of the capital. On top of the terror that accompanied the gunshots ringing out day and night, lifeless bodies started showing up on the streets near their home, the couple recounts.

“When you live in gang-controlled areas, danger comes from everywhere, from rival gangs and even from the police,” says Ms. Azor, who didn’t dare leave her home after 6 p.m.

After little more than a year in Gonaïves, Mr. Byron says he feels not only safer but also more professionally and personally fulfilled. He mentors aspiring journalists and participates in literary festivals. Ms. Azor was hired last fall to oversee the media library at a local cultural center.

Still, Gonaïves has its challenges. Hurricanes have brought the city to its knees repeatedly over the past 20 years, killing hundreds of people and destroying key infrastructure. And although it is known for its hospitality, Gonaïves struggles to keep up with its welcoming reputation, the couple says.

“Gonaïves is not immune to the troubles Haiti is facing. In terms of infrastructure, it lacks almost everything, and the job market is very limited,” says Mr. Byron.

“If they find the right formula, they will be able to take advantage” of this situation, with so many professionals fleeing the capital, and could possibly become a “credible alternative” to Port-au-Prince, he says.

History – and suspicions

While most Haitians express compassion for those displaced, there’s still a fear that movement out of the capital is simply spreading lawlessness further across the country. In March, gang clashes erupted in cities in the same department as Gonaïves, bolstering that sentiment.

Kersaint, a local academic who asked to use only his first name out of concern for his safety, counts himself among those worried about rising crime and other repercussions of such vast domestic migration.

“There is new pressure on the demand for housing,” he says. The lack of formal social integration programs for new arrivals in Gonaïves could spell “interpersonal and intergroup conflicts [that could tear] the social fabric apart,” he worries.

The mayor’s office is organizing a survey with support from the International Organization of Migration to identify displaced populations and their needs. It’s not a homogenous group, says Donald Diogène, mayor of Gonaïves. “There are those who return, having left the city for various reasons; those who ... planned extensively to settle here; and others who had to leave everything behind, running without knowing where or how they are going to survive.”

The local government is trying to reassure locals, but in doing so it may be unintentionally heightening fears. The police, mayor’s office, and public prosecutor’s office set up checkpoints around the city’s perimeter to prevent gang members from entering alongside those seeking safety. The government has instructed locals to pass on information about any strangers sighted near their homes.

But internal migration could affect more than just small-town demographics and security, says Hancy Pierre, a specialist in migration at the State University of Haiti. Activists and scholars have characterized the government’s lack of response to gang violence in the capital as intentional: The unrest bolsters largely unpopular arguments for foreign intervention, and the movement of people could affect electoral maps. If typically left-leaning urban populations are dispersed across the country, that could affect the outcome of long-awaited presidential and local elections, Professor Pierre says.

The legacy of previous migration within Haiti is top of mind, too. Mr. Bien-Aimé, the sociologist, points to policies implemented during the nearly 30-year dictatorship of father-son duo François and Jean-Claude Duvalier in the second half of the 20th century that would bus people into the capital from the countryside for political rallies and then strand them. They led to the creation of informal, underserved communities, like present-day Cité Soleil.

The context may be different, but looking back at history, “I don’t think this new wave of internal migration will have a positive long-term impact on the country,” says Mr. Bien-Aimé.

Reversing brain drain?

Focusing on the negatives misses the potential good that might come from this moment, argues local high school teacher Charlito Louissaint. There’s opportunity here, he says, especially when it comes to the influx of professionals like Mr. Byron and Ms. Azor, who bring with them experience and new ideas.

“We usually see the brightest brains from the countryside automatically flocking to the metropolitan area. It is the reverse today,” says Mr. Louissaint. “Unfortunately, these [small] cities do not have the capacity and resources required to receive them and keep them,” he says, pointing to constraints like the absence of many public services and limited professional and educational opportunities.

He’s reminded of the aftermath of Haiti’s devastating 2010 earthquake. “People came but quickly left because of a lack of opportunities. Thirteen years later, we are reliving the same scenario,” says Mr. Louissaint.

But, if there’s political will, that could all change, he says.

Displaced people have brought tangible innovation, such as more fleets of tap-taps, privately owned vans used as shared taxis. And existing companies and institutions are putting down new roots outside of Port-au-Prince in communities that can welcome them. Quisqueya University, one of the capital’s top universities, moved its Agriculture School to Mirebalais in Central Haiti, and a renowned international music festival, the Port-au-Prince International Jazz Festival, left its namesake city and was held in the north for the first time in the festival’s 16 years.

Elys Ciane, a young professional, fled Port-au-Prince’s insecurity in June. “The decision to leave was difficult. I had to analyze all my possible options,” he says.

After a month of market research, he landed on Gonaïves, where he felt there was untapped opportunity. Mr. Ciane and a business partner opened a rooftop lounge, soft-launching the project in mid-July.

“Our aim is to offer a space that is calmer and has services that [everyone] can use. This will help promoters be more creative,” says Mr. Ciane. He would like to see Gonaïves host events that normally gravitate toward big cities, and that shift already seems to be underway. The Billboard-charting Haitian group Zafem recently launched an international tour, including a number of stops in Haiti’s provincial cities – but not in Port-au-Prince.

“Gonaïves isn’t perfect,” Mr. Byron says. Moving here meant looking beyond the life the couple had long envisioned for themselves. “Starting over in a new city was never going to be easy,” adds Ms. Azor.

Yet, she says, so far? “It feels promising.”

This story was produced with support from the Round Earth Media program of the International Women’s Media Foundation in partnership with Woy Magazine.

Why Dutch universities may teach less often in English

Dutch universities are having to balance their desire for international students against their need to protect limited resources – by using tools generally wielded by nationalists.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Dutch higher education draws 40% of its student body from abroad, due in part to the language in which many classes are taught: English. In the last few decades, however, the growing number of foreign students is threatening to overwhelm university facilities and cut off their accessibility to domestic students.

To address the issue, authorities have offered a controversial new proposal. It would require universities to teach more classes in Dutch and allow certain enrollment caps, thus effectively shrinking the number of students coming in from outside the Netherlands.

The proposal’s focus on Dutch-language education sounds like a byproduct of the rightward political shift happening all over the world. But most university representatives agree that the unfettered influx of international students needs to be controlled somehow.

Under EU law, universities cannot bar students coming from the European Union, and those students make up most of the foreign student population. That necessitates workarounds like changing the language of education to Dutch.

“There are a lot of people who are really happy with this proposal,” says Aziza Falal, a Dutch student. “The capacity of Amsterdam is really too small to have all the international students. ... Maybe in five to 10 years, it will be different.”

Why Dutch universities may teach less often in English

For Regina Huang, transporting her life from China to the Netherlands for an anthropology degree was a no-brainer.

Many Dutch university classes are taught in English, Amsterdam is one of Europe’s most international cities, and the study of anthropology thrives on a diversity of cultures. “And there are quite a lot of [nongovernmental organizations] and consultancies here that are open and value the work of anthropologists,” says Ms. Huang, who is studying for her master’s degree at the University of Amsterdam.

Yet a controversial new education proposal threatens to effectively roll up the Netherlands’ welcome mat.

It would require universities to teach more classes in Dutch and allow certain enrollment caps, thus effectively shrinking the number of students coming in from outside the Netherlands. Education Minister Robbert Dijkgraaf referred to the dire need to address the “unchecked pace of internationalization, both in education, and more broadly, in the workplace and the community.”

This proposal has everyone from foreign professors to international students rethinking their futures in the Netherlands.

“It’s a bit sad,” says Ms. Huang. “With my study background, I’m all for cultural diversity and intercultural communication, and it’s really helpful for people to understand differences between people. I do think this discourages people’s confidence to build a future after graduating here.”

Internationalization is becoming an ideological flashpoint as right-wing political groups gain influence across Europe, and in the Netherlands, international students have unfortunately become an easy target, say the proposal’s critics. But even universities are worried about being overwhelmed by quantities of international students beyond their ability to accommodate them – and are searching for ways to control their numbers.

Foreign students now make up 40% of all incoming university students in the Netherlands, and Dutch classrooms and student housing are overloaded, with spaces becoming less accessible to locals. So universities are trying to improve access for Dutch students to access their services without turning off the international spigot so central to the Netherlands’ reputation in a global economy.

“Our top universities are playing in the international field – it’s like a Champions League for soccer,” says Jeanet van der Laan, a member of the Dutch parliament. “We have to be connected. Our country thrives on development and innovation, and we have a lot of big international companies. We can’t be too radical in the decisions we make for the future of the Netherlands. We don’t want to be caught up in a conservative agenda to restrict international students because some parties don’t want migrants.”

Too many students, too little space

While the obvious solution to Dutch concerns about too many international students may seem to be simply to cap the numbers, there’s a reason that’s not being considered: It would violate European Union law. Under EU strictures, non-Dutch EU citizens must get the same treatment as Dutch citizens. Thus, they can’t be barred from enrolling in Dutch universities. While a bar could be applied to students from outside Europe, “most of the international students come from the rest of the EU. We cannot discriminate between them,” says Wouter van der Brug, a political scientist at the University of Amsterdam.

That legal framework is what prompted the government proposal’s focus on English and Dutch languages instead of student citizenship. And Dutch student Aziza Falal understands how the proposal comes off to non-Dutch.

“We’re not nationalistic, absolutely not,” says Ms. Falal, who advocates for students’ rights as chair of a university student union. “We want to be a knowledge economy because we like inclusivity and we like to have other people to learn from.”

But after watching countless students – both local and international – struggle to access university spots and secure housing from an increasingly scarce supply, Ms. Falal says she sees the merits of pressing the pause button. Some 115,000 international students are enrolled in Dutch higher education, a proportion that increased by almost 50% from a decade ago. That translates to roughly 4 of 10 incoming students hailing from outside the Netherlands.

To Ms. Falal, the education minister’s proposal is about ensuring that a system bursting at the seams has enough resources for all.

“There are a lot of people who are really happy with this proposal,” says Ms. Falal. “The capacity of Amsterdam is really too small to have all the international students, get them a good education, and house them. Maybe in five to 10 years, it will be different.”

Yet teaching classes in Dutch and restricting international student numbers would be a tough balance to strike at Eindhoven University of Technology. It’s located in a hub of the Netherlands’ high-tech sector, in the city that birthed Philips and DAF Trucks. All Eindhoven University classes are taught in English, and the school is a magnet for computer scientists and engineers from all over the world. What happens when English becomes limited on campus?

“I have to find some Dutch[-speaking] professors, which we don’t find ... anymore in artificial intelligence, electrical engineering, 5G, and 6G,” says Robert-Jan Smits, president of the executive board of Eindhoven University of Technology.

For Ali Hamdan, a political scientist who relocated from Los Angeles to the University of Amsterdam only last year, the proposal feels like whiplash, or a possible reversal of fortunes.

“The fact that the university is in entirely English was a huge draw, and for equally obvious reasons, it is very stressful to imagine the system changing in such a dramatic way,” says Dr. Hamdan, who points out that non-Dutch speakers would need additional time and resources to reach teaching proficiency in Dutch. “At Dutch universities, the teaching load is already a bit higher than research-intensive universities in the U.S. What this could do is incentivize people who really prioritize research to leave.”

And the Netherlands is in dire need of workers – especially university students willing to stay and enter the job market – as well as academics and workers of all skill levels. Just considering the tech sector, only 1 or 2 Dutch students out of 10 go into STEM fields, which would mean a tremendous shortage of talent for an economy that prides itself on being an innovation hub.

“The Dutch are facing, like most European countries, an enormous demographic decline,” says Dr. Smits. “If we’re not overtaking that with top-notch talent from abroad, then of course we have huge problems for the academic system, but also economy.”

Not about the right

It’s easy to view the proposal as a byproduct of the rightward political shift happening all over the world. The Netherlands’ fragile four-party coalition government collapsed this summer over migration policy, with new elections slated for the fall. Though the proposal is in a waiting period now, most analysts do expect it to pass in some form no matter what coalition is formed after elections.

“There is a very strong sentiment in parliament, especially among the more conservative parties, that we need to protect the Dutch language, Dutch culture, etc.,” says Dr. van der Brug, the political scientist.

But most university representatives agree that the unfettered influx of international students over the last few decades – driven by a host of push and pull factors such as skyrocketing U.S. college costs as well as the growing reputation of Dutch universities – need to be controlled somehow. Since the English-language curriculum became the norm at the University of Amsterdam, numbers have increased too rapidly for the university to adapt, says Dr. van der Brug. “You need lecture halls; you need facilities; you need staff. So we want to control the numbers. They have come up with something, but it’s not really what we asked for.”

Dr. van der Brug says limiting access to English-language tracks, while promoting Dutch-language courses and Dutch enrollment, is the best way to provide such control. But the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science isn’t allowing that, he says, and much else about the proposal is vague.

Overall, the danger is that the plan would result in unintended consequences.

“The Dutch always had a liberal, open country,” says Dr. Smits, the Eindhoven University board president. “It’s been a strength of the economy for centuries. The Portuguese Jews, when they were kicked out in the 17th century, came to the Dutch. The Huguenots, the Protestants when the French king kicked them out. The Flemish artists after the conquest of Antwerp. The Spaniards. They all came to Holland.

“Decoupling, to use a term of American politics, is a very bad idea because you are creating barriers,” Dr. Smits adds. “You are creating distances between countries, which is extremely dangerous in the long run, that there is no mutual understanding anymore, no exposure to each other’s cultures. We are creating walls again, and that’s not good for peace on this planet.”

Consumers conflicted over ‘out of control’ tipping

Surveys show Americans are souring on tipping, especially as technology permits more frequent requests. Consumers feel pinched, yet conflicted over how best to support service workers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Many consumers are feeling a double punch: squeezed by inflation and overwhelmed by near-ubiquitous tip requests known as “tip creep,” driven largely by electronic payments and the ease of requesting a tip. In a recent survey by Bankrate, two-thirds of Americans had a negative view of tipping and nearly one-third said tipping culture is “out of control.”

Customers are pushing back. The frequency of tipping has declined since 2019. For instance, those who say they always tip servers in a sit-down restaurant has dropped 12 percentage points. There are also measurable drops in how often customers tip hairstylists and taxi drivers.

Those percentages dip even more when focused on Generation Z and millennials. “A lot of people, especially young adults, say, ‘It’s not fair. We’d rather just pay higher prices. Let’s do away with the whole tipping thing,’” says Ted Rossman, senior industry analyst for Bankrate, a financial comparison website.

Alex Ellsworth, from San Francisco, would prefer pricing that does away with a gratuity. But peer pressure and habit are strong reasons to keep tipping, and he’s unlikely to stop unless the option disappears. “If we’re given permission not to [tip], we’ll be like, ‘Hey, that’s liberating.’ But if we are pressured to, then we’ll keep doing it.”

Consumers conflicted over ‘out of control’ tipping

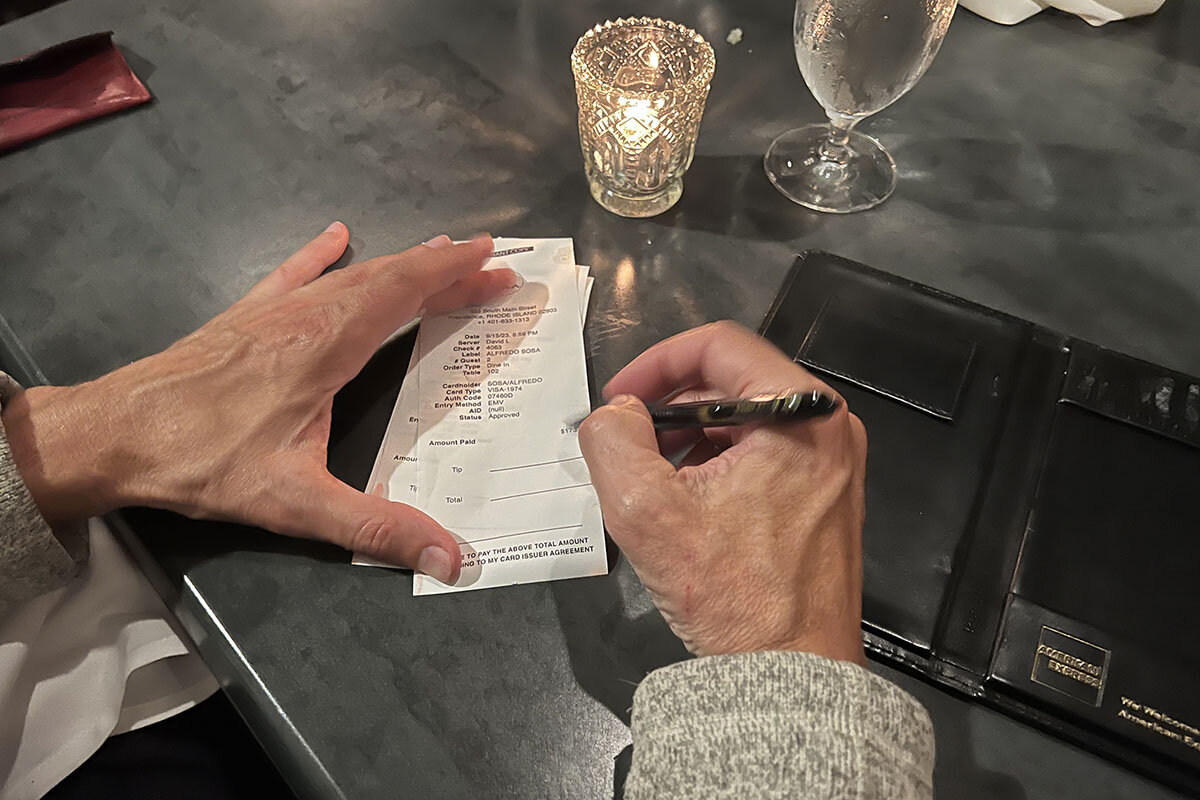

Alex Ellsworth planned for a special night out in San Francisco with his boyfriend. The restaurant he chose was a splurge, but the self-proclaimed foodie decided it was worth it. With a $70-per-person prix fixe meal, he thought he could control the budget – they refrained from ordering drinks and were careful about other add-ons.

Then the check came: In addition to tax, the restaurant tacked on a 20% service fee, plus 5% that goes toward health care for uninsured city residents. But with a tip section still on the receipt, Mr. Ellsworth felt compelled to tip. “I really felt sadness and regret as I filled in the receipt with a tip that was equivalent to my weekly food budget,” he says. He spent $100 more than he’d expected.

His experience is not unique. Surcharges have become common in restaurants, even with gratuities still expected. Electronics have also made it easier to request tips, which are popping up in fast-food restaurants, retail, and some places with self-service. The combination of increased costs and frequency is irking consumers.

Tipping persists despite the social inequities and economic insecurities it reinforces; at the same time, wage models are shifting as more states increase the minimum wage. “Writ large, this is exposing ... just how absurd tipping is and how we all try to rationalize it as money provided on a variable scale based on the service we’ve received,” says sociologist Eli Wilson at the University of New Mexico. “Increasingly we’re seeing how much that logic no longer flies, in the spread of ways that consumers are being asked to tip and who they’re being asked [to tip].”

Pushing back

Many consumers are feeling a double punch: squeezed by inflation and overwhelmed by near-ubiquitous tip requests known as “tip creep,” which is driven largely by electronic payments and the ease of requesting a tip. In a recent survey by Bankrate, two-thirds of Americans had a negative view of tipping and nearly one-third said tipping culture is “out of control.”

Customers are pushing back. The frequency of tipping has declined since 2019. For instance, those who say they always tip servers in a sit-down restaurant has dropped 12 percentage points. There are also measurable drops in how often customers tip hairstylists, taxi drivers, and other service providers.

Those percentages dip even more when focused on Generation Z and millennials, who, according to research, are turned off by tipping’s inequities. “A lot of people, especially young adults, say, ‘It’s not fair. We’d rather just pay higher prices. Let’s do away with the whole tipping thing,’” says Ted Rossman, senior industry analyst for Bankrate, a financial comparison website.

The job isn’t worth doing without tips, according to some servers. “I don’t think most people would be servers. For sure,” says Julia, a server at a diner in Bakersfield, California, who declined to give her last name. “Servers don’t work 9-to-5 jobs,” she adds. “The tips are what make up for the rest of that.”

Tip percentages have risen over the last century. In the early 1900s, tip norms in restaurants and bars were 10% to 12%. Today, industry expectations are around 20% – although less than half of U.S. adults say they typically tip that much. “The recommendation and the action tend to be different,” says Mr. Rossman. “So I think that there is this pushback.”

Recently, customers have been annoyed by suggested-tip screens popping up in places where tips weren’t previously considered, like retail shops and online stores – sometimes suggesting tips as high as 35%. Starbucks made headlines last year when it rolled out tip screens for credit card transactions.

Tipping prompts will likely continue for the near future, experts say, as long as too many customers aren’t driven off.

Worker and employer interests “align here in seeing if they can get consumers to pay out a little bit more in gratuities,” says Professor Wilson, author of “Front of the House, Back of the House: Race and Inequality in the Lives of Restaurant Workers.”

Even if only half of customers are tipping, that still adds up to a lot, points out Mr. Rossman. “Customers may grumble, but if they’re not going to change their behavior and they’re not going to spend less ... we’re going to see more of this.”

Problematic then and now

Tipping as we know it in America normalized in the 20th century. Its roots go back at least 100 years earlier (some trace it to medieval times), when wealthy European clients would pass on small amounts of money to much poorer workers providing personal services. Even then, the arrangement was uncomfortable for some.

“It’s pretty much born out of unequal hierarchical social relations,” says Professor Wilson. When brought to America, tipping was viewed as undemocratic, and because of that “there was very, very strong resistance to tipping in the late 1800s and early 1900s.”

After the Civil War, American businesses like The Pullman Co. encouraged tipping to offset low wages. In Pullman’s case those workers were porters, many of whom had been previously enslaved. “They could pay them less and basically just hope that customers make up the difference,” says Mr. Rossman.

Today, tipping is entrenched in the wage model for certain services where transactions are based on human connection. “It has to do with creating an atmosphere where the guest or the consumer feels that the employee deserves it,” says Hicham Jaddoud, a hospitality and tourism professor at the University of Southern California.

Estimates place the number of tipped workers in the United States above 5 million. More than three-fourths are in the food industry; the rest are distributed among other services. Anyone whose occupation brings in at least $30 a month in tips qualifies as a tipped employee – and qualifies to make a tipped wage, which varies wildly from state to state.

The federal tipped wage – the minimum wage for tipped workers – is $2.13 an hour, where it’s been since 1996. Tips are earned on top of that. Fifteen states adhere to that minimum, but most states have raised it. Some add a few cents an hour, while a handful of states require employers to pay tipped workers a full minimum wage.

Those wage disparities reflect the varied power of workers across the country. “If you go to the Midwest, you will be surprised how low wages are versus California or even Texas,” says Dr. Jaddoud. “It all has to do with the state, the bargaining power, and how short staffing-wise that state is and how powerful the unions are.”

Rewarding a human connection

The service element is what customers are missing in transactions limited to takeout, retail, or online ordering – and that’s reflected in lower and less frequent tips.

In restaurants, where servers spend an hour or longer engaging with clients, or in salons or hotels where employees have highly personal interactions with customers, tips not only relieve the employer’s wage burden, but also incentivize workers with potential earnings.

That’s the case at Mamma Mia, a high-end restaurant in Bakersfield. Owner Bruno Garcia – who worked his way up in the industry, starting as a busboy – believes the tip system benefits everyone. Servers can make more money by providing excellent service, and clients enjoy that better service. “The tip is voluntary, and the customers ... will tip you depending on the effort.”

Level of service provided is the sole criterion for Jennifer when she leaves tips. “I think that’s the only way,” says the Bakersfield salon manager, who declined to give a last name. Tipped occupations are a lifestyle choice and “at the end of the day, it’s their decision to stay in that position.”

Ending tipping?

A movement to eliminate tipping in favor of higher hourly wages has some support, but experiments to do that have yet to prove successful. So far, most consumers haven’t shown willingness to pay higher sticker prices, even when they know it includes tips and fees.

Prices are more palatable when customers see the portion that goes to an employee. If prices do go up, customers want added value.

Mr. Ellsworth feels the pinch from inflation and California’s high cost of living. He also understands the importance of tips to low-wage workers: He previously worked as a hotel desk agent in Texas. Yet in San Francisco, where the minimum wage for everyone is over $18, tipping feels harder to justify on his tight budget, especially when he eats cereal every weekday so he can afford to go out on weekends.

Mr. Ellsworth would prefer straightforward pricing that does away with a gratuity. But peer pressure and habit are strong reasons to keep tipping, and he’s unlikely to stop unless the option disappears.

“[Customers] don’t want to be seen as awful people,” he says. “And so if we’re given permission not to, we’ll be like, ‘Hey, that’s liberating.’ But if we are pressured to, then we’ll keep doing it.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why a climate summit for mayors?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In June, Milwaukee became one of the latest cities to adopt an ambitious plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – by 45% in seven years. Each piece of the plan was designed to enable people to live out local values while also acting on climate change. A good example: Planners noted a strong desire among low-income youth for high-paying jobs, which led to a program to train electricians for new solar- and wind-generated power stations.

The city’s success – one that started with tapping into people’s values to enable them to see their role in climate action – helps explain a notable first at this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference. The gathering of nearly 200 countries, which starts Nov. 30, will include a formal summit of local government leaders, mainly city mayors.

“Cities are where the climate battle will largely be won or lost,” said U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres.

In less than three months, during the first summit for cities at a U.N. climate conference, mayors with climate plans well underway may show national leaders how to engage citizens with a spirit of listening. Understanding local values is a first step toward earning support for solutions to cool the planet.

Why a climate summit for mayors?

In June, Milwaukee became one of the latest cities around the world to adopt an ambitious plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – by 45% in seven years. Each piece of the plan was designed to enable people to live out local values while also acting on climate change. A good example: Planners noted a strong desire among low-income youth for high-paying jobs, which led to a program to train electricians; all the solar- and wind-generated power stations, as well as charging stations, will need more of them.

“This is not just a plan that’s going to just sit on a shelf,” said Milwaukee Alderwoman Marina Dimitrijevic. “This is going to live in everything that we do.”

The city’s success – one that started with tapping into people’s values to enable them to see their role in climate action – helps explain a notable first at this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference. The gathering of nearly 200 countries, which starts Nov. 30, will include a formal summit of local government leaders, mainly city mayors.

“Cities are where the climate battle will largely be won or lost,” said U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres. In fact, many cities have cut per capita emissions at a faster rate than their national governments.

In the United States, a recent survey of 20 urban areas by the Manhattan Institute shows why cities are adopting climate plans. On many local issues, says the institute’s senior fellow Michael Hendrix, residents easily cross partisan divides. “It’s hard to see that there’s a clear Democratic or Republican way for you to win on particular issues,” he told City Journal.

Many cities seeking climate action, especially at the neighborhood level, “are small enough to allow for high ambitions, community engagement and new approaches tailored toward local needs,” write urban experts Mark Watts and Claus Mathisen on the website SmartCitiesWorld.

One challenge in climate action is to avoid “unilateral imposition of measures – particularly those that will be expensive or require behavioral change,” writes David Simon, a professor of development geography at Royal Holloway, University of London, in Foreign Policy. Cities, he adds, must “understand residents’ anxieties and constraints and identify mutually acceptable ways forward.”

In less than three months, during the first summit for cities at a U.N. climate conference, mayors with climate plans well underway may show national leaders how to engage citizens with a spirit of listening. Understanding local values is a first step toward earning support for solutions to cool the planet.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

You’ve got to want it

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tressie Armstrong

A heartfelt desire to know God as the infinite source of goodness opens the door to improved health and greater harmony.

You’ve got to want it

Recently as I was out enjoying the beautiful ocean on my surfboard, a wave began to crest. I turned to paddle and heard an enthusiastic friend encourage me, “You’ve got to want it!”

Well, the wave rolled under me and I missed it. But I got to thinking about my friend’s comment, and other aspects of life it could apply to.

In my study and practice of Christian Science, I turn to prayer throughout my day. It struck me that it’s useful to consider what it is that we’re really yearning for when we pray.

Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, states in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Desire is prayer; and no loss can occur from trusting God with our desires, that they may be moulded and exalted before they take form in words and in deeds” (p. 1). To me, this points to a willingness to let go of unhelpful modes of thought and fears, and to prayerfully seek the spiritual reality of God’s complete goodness.

If God is All and is all good, as the Bible conveys, then everything we need is already present. God provides abundantly for all of us, His spiritual offspring. From this perspective, all that’s left to desire is the understanding that God’s goodness is already present. From this flows better health, stronger relationships, needed resources, and a more permanent peace. So, is this understanding worth wanting? Absolutely!

There are countless instances in the Bible where people showed a deep desire and commitment to understand the truths that Jesus taught. Let’s take Zacchaeus, for one. A tax collector, Zacchaeus was seen as a sinner, unworthy of receiving attention from Jesus. But he had such a desire to know Christ, the eternal divine nature that Jesus expressed, that he climbed a tree to be able to see Jesus.

Jesus discerned this desire and told Zacchaeus to come down because that day he needed to stay at his house. Through this interaction, not only did Zacchaeus become a better man, but those around him benefited, too.

We can all seek a conviction of what Jesus proved to be the truth of our real being – that we are not mortals with problems, but entirely spiritual and good, created in the image of God. Science and Health defines God as “the great I AM; the all-knowing, all-seeing, all-acting, all-wise, all-loving, and eternal; Principle; Mind; Soul; Spirit; Life; Truth; Love; all substance; intelligence” (p. 587). The desire to know God, and to recognize His beautiful attributes as reflected in ourselves and others, brings great blessings.

There was a period when I struggled with painful shoulders. I chalked it up to age and overuse from years of swimming and surfing. But then I caught myself. Was this view of existence as fundamentally material and flawed what I truly wanted? The answer was an emphatic “No!”

So over a few months I prayed, fueled by a desire to know my true nature as God’s child, created to express abundant qualities that could never be lost in God’s infinitude. Qualities such as grace and freedom are inherent in our true being as the spiritual reflection of God.

Then one morning I felt inspired to go back out into the ocean. As I did, I found that there was no more shoulder pain. I caught a few beautiful waves and have not had a problem with my shoulders since. I continue to swim and surf regularly.

As God’s children, we all have an innate desire for goodness, health, harmony, and peace. God, divine Love, could never leave any of us in a dire circumstance or leave us to struggle on our own. We already have what we need – God’s infinite love for all. When we prayerfully nurture this inherent desire, we’re opening ourselves up to a better understanding of what already is.

As the sun disperses a mist, so a desire to understand the spiritual reality of existence disperses the mist that would make us think we can be lacking in good, and leads us into seeing the good that God bestows on us at every moment. We just need to want to see it. Then we find the metaphorical sun shining more brightly and waves cresting more perfectly, in a more joyful, grace-filled, and harmonious experience.

Viewfinder

Giving wellies the boot

A look ahead

Thank you for supporting the Monitor. Tomorrow, staff writer Ira Porter will look at colleges starting varsity and club esports teams – yes, video games as sports, including scholarships. How is the billion-dollar, worldwide esports industry changing campuses?