- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What the border crisis looks like from the border

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

The mayor of Eagle Pass, Texas, was finally left with no option but to sign an emergency declaration Wednesday. Some 4,000 unauthorized immigrants had crossed the Rio Grande into his city in the previous two days.

Mayor Rolando Salinas Jr.’s declaration is the culmination of a crisis building for more than a year. Illegal border crossings in the area are growing dramatically, and Texas’ Republican governor, Greg Abbott, has responded aggressively. Two-year-old Operation Lone Star has brought in state law enforcement and taken controversial measures, such as putting buoys tipped with saw blades in the Rio Grande. On Wednesday, Governor Abbott vowed on social media to reinstall razor wire he said was cut by the federally run Border Patrol.

The Monitor’s Henry Gass was there last week, and he’s working on a story for next week. He tells me he saw echoes of what our Story Hinckley found at a different part of the border a year ago. Many in the area, including Latinos, want the government to take a tough stand. Some are turning to the Republican Party because of it.

Henry heard stories of houses broken into and hospitals unable to help citizens because they were full from the influx of border crossings.

Yet he also saw evidence of limits to the “get tough” approach. As other reports from Eagle Pass have indicated, he sees the initial enthusiasm for Operation Lone Star waning. What the people of Eagle Pass want is efficiency, not cruelty – especially cruelty that doesn’t seem to be deterring migrants.

“It’s complicated,” Henry says. “You hear a lot about the need for more enforcement – about immigrants coming to America the ‘right’ way. But some of these things, there’s a sense that it’s inhumane and going way too far.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Zelenskyy asks for more aid – now a tougher sell

The Ukrainian president’s U.S. visit comes as Congress heads toward a possible shutdown and 55% of Americans oppose additional aid to Ukraine.

Nine months after he got a standing ovation before a joint session of Congress, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy returned today – under notably different circumstances – to make a pitch for more U.S. aid.

Aware that America’s enthusiasm for the war effort had eroded significantly, President Zelenskyy said Ukraine was making progress and using U.S. aid effectively, but that further support was necessary to protect the global world order.

A strong bipartisan contingent of senators, along with President Joe Biden, agrees with him. If Russian President Vladimir Putin wins in Ukraine, they argue, his next target will be a NATO member – which America is treaty-bound to protect. That could draw U.S. forces into a direct conflict with Russia.

But the timing couldn’t have been worse. With funding for the U.S. government set to run out Sept. 30, Congress is locked in a stalemate over spending – and appears to be heading for a shutdown. Lawmakers, mostly on the GOP side, are balking at spending taxpayer dollars on a country that, 19 months into the fighting, lacks a clear path to victory and has a notorious history of corruption.

“I just don’t have much confidence that our money is being well spent,” says GOP Sen. Roger Marshall of Kansas.

Zelenskyy asks for more aid – now a tougher sell

Nine months after he got a standing ovation before a joint session of Congress, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy returned today – under notably different circumstances – to make a pitch for more U.S. aid.

Aware that America’s enthusiasm for supporting the war effort had eroded significantly, President Zelenskyy urged the U.S. to stay the course. According to senators who attended the closed-door briefing, he said Ukraine was making progress and using U.S. aid effectively, but that further support was necessary to protect the global world order.

Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut, a Democrat on the Foreign Relations Committee, summed up Mr. Zelenskyy’s argument as: “We have lived up to our end of the bargain, and we hope you see that and don’t choose this inflection point to abandon us.”

A strong bipartisan contingent of senators, along with President Joe Biden, agree with the Ukrainian leader. If the U.S. doesn’t help Ukraine against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion, they argue, his next target will likely be a member of NATO – which America is treaty-bound to protect. And that could draw U.S. forces into a direct conflict with Russia.

“It’s really pay now – or pay a lot more later to stop Putin,” says Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, who sits on the Armed Services Committee and has visited Ukraine four times.

But the timing couldn’t have been worse for President Zelenskyy’s in-person request. With funding for the U.S. government set to run out Sept. 30, Congress is locked in a stalemate over spending – and appears headed for a government shutdown. Amid ballooning deficits and record-high national debt, Republicans are scrutinizing every dollar in proposed budgets for domestic priorities. And more lawmakers, mostly on the GOP side, are balking at spending taxpayer dollars on a country that, 19 months into the fighting, lacks a clear path to victory and has a notorious history of corruption.

Mr. Zelenskyy’s firing of all six of Ukraine’s deputy defense ministers shortly before his visit, after sacking the defense minister himself earlier this year, was broadly seen as an effort to clean house.

A U.S. government oversight effort involving 20 different organizations said in a March report that despite receiving 189 complaints alleging misconduct involving U.S. aid to Ukraine, investigations had “not substantiated significant waste, fraud, or abuse.” However, it also noted that it was difficult to conduct “end-use monitoring” because of the lack of U.S. personnel in Ukraine. Senate Republicans are pushing to create a special inspector general position to oversee Ukraine aid.

“I just don’t have much confidence that our money is being well spent,” says GOP Sen. Roger Marshall of Kansas, who supported the initial U.S. aid package after Russia’s February 2022 invasion. Overall, the U.S. has appropriated $113 billion – only about 0.5% of GDP but far more than he and his colleagues have proposed spending to secure the southern border, an issue he says matters more to his constituents.

“Until we have a plan to secure the southern border, you can count me out for any more funding for Ukraine,” said Senator Marshall, one of six GOP senators and 23 House Republicans to sign a letter to the Biden administration today opposing its request for an additional $24 billion.

Kiel Institute for the World Economy

As he met with Mr. Zelenskyy this afternoon, Mr. Biden announced a new $325 million military aid package, which is to be drawn from existing Pentagon inventory and thus does not need congressional approval.

In the early days of the war, Mr. Zelenskyy’s courage in staying in Kyiv even as top U.S. military and intelligence officials predicted it would soon fall to Russia earned him great respect – and strong bipartisan support for two initial rounds of aid, at $13.6 billion and $40 billion respectively.

But a year and a half later, with estimated war deaths exceeding 150,000 and a major Ukrainian counteroffensive failing to make much ground, the initial support seen in blue-and-yellow flags hung outside homes across America has weakened. A CNN survey in August found that 55% of Americans oppose sending more aid to Ukraine. Among the 45% in favor, older people and Democrats were the most supportive.

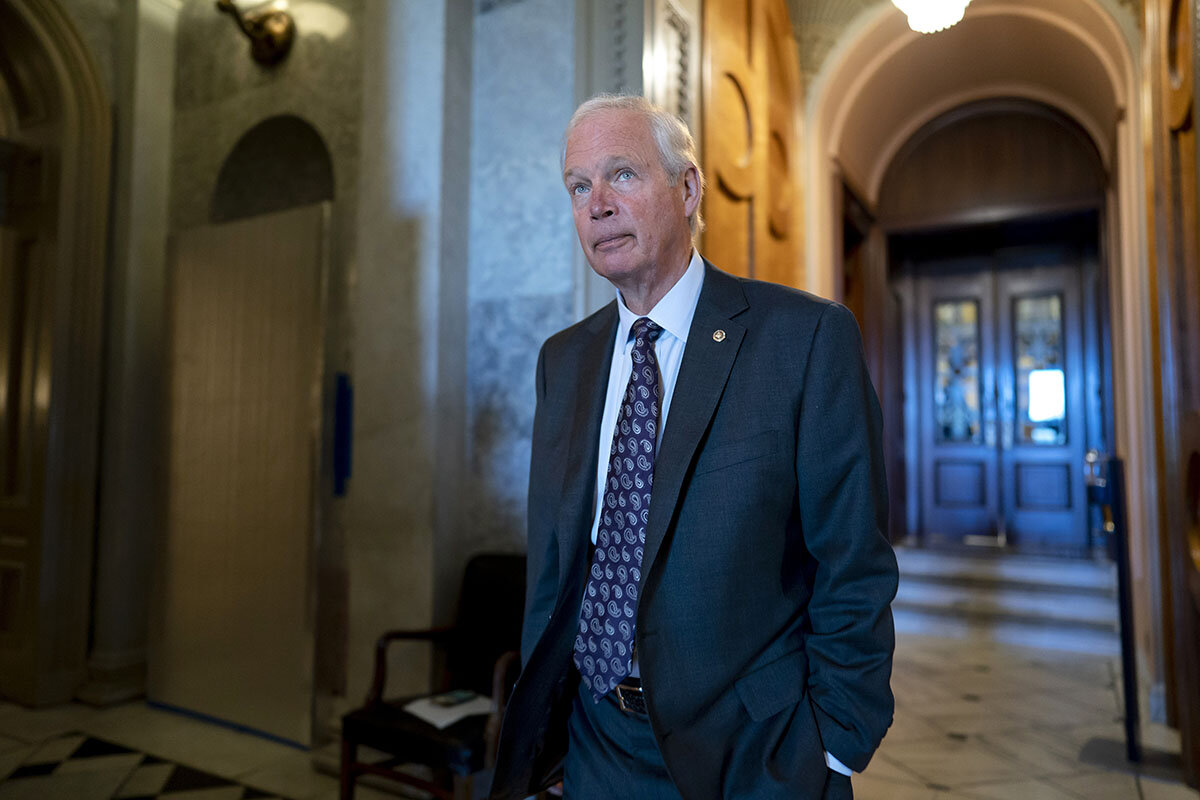

“They want to be supportive,” says GOP Sen. Ron Johnson of his Wisconsin constituents. But mounting U.S. deficits and the appearance of a stalemate in Ukraine make them hesitant, he adds. “I think they recognize reality.”

Senator Johnson voted for the $40 billion package in May 2022, hoping Mr. Putin would rethink his invasion and stop. Now he’s convinced the Russian leader will not under any circumstances lose this war, even if it means resorting to nuclear weapons. “What the Biden admin should be doing, quietly – and it should be quiet – is figuring out some way to bring this war to an end,” he says.

Most of the lawmakers registering objections are Republicans. But progressive Democrats have also voiced concerns. Of the House members who voted against the initial $13.6 billion aid package, 54 were Republicans and 15 were Democrats. Last fall, the Progressive Caucus released – and then retracted, amid a firestorm of criticism – a letter calling on President Biden to engage in direct diplomacy with President Putin to find a way to end the war.

Ukraine’s supporters say just because it’s getting harder to make the case to Americans doesn’t mean Congress shouldn’t try. It’s not only possible, but essential, to address Americans’ domestic concerns while helping Ukraine win its battle with Russia, they argue.

“We can do both, and we must,” says Senator Blumenthal. He has visited mass graves in Bucha and met with soldiers who lost limbs in the fighting and mothers who lost sons. “We are reliving the atrocities of the 1920s and 1930s,” he says.

Moreover, the U.S. is signatory to a 1994 agreement to protect Ukraine’s sovereignty in exchange for giving up its nuclear arsenal – at the time the third-largest in the world.

Some Republicans say the president needs to make a more forceful case to the American people that helping Ukraine is in the nation’s interest – and that walking away could be disastrous.

“This generalized talk about defending democracy around the world – it’s not wrong, but it’s not enough,” says Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, who sits on the Foreign Relations Committee. “I think if we were to walk away from Ukraine, our entire system of alliances around the world would collapse. It would reinforce the narrative being used against our country by our adversaries that we’re weak, that we’re hollowed out. It would be the Afghanistan withdrawal on steroids.”

Editor’s note: The story has been updated with the formal announcement by President Biden – later in the day of President Zelenskyy’s visit – of new aid for Ukraine that doesn’t require congressional approval.

Kiel Institute for the World Economy

In Lebanon, combating the ‘normalization of misery’

The resolve and optimism of Lebanon’s 2019 “revolution” have given way, for most Lebanese, to a grim struggle to survive, modestly bolstered by handouts of aid. Facing stubborn social inequities and nonresponsive elites, how do people manage?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Lebanon’s economic meltdown was brought on when the government defaulted on its debt and the currency collapsed in 2019. It triggered months of protests demanding political reforms and accountability from sectarian elites – protests dubbed a “revolution” by the thousands who took to the streets.

Yet assumptions on the street that the economic collapse would jolt the ruling elites into action proved not to be true, says David Wood, an International Crisis Group analyst. “The calculation has been made,” he says. “Lebanon’s elites have decided that ... it actually serves their narrow self-interest to do nothing.”

Despite the lack of reform, the crisis has significantly expanded one area of government that appears to be working: the provision of cash assistance, administered via two social welfare programs.

The United Nations World Food Program estimates that it supports one-third of all the people in the country, working largely through those government structures. Despite that support, a quarter of all those living in Lebanon are deemed “food insecure.”

Zuhair, a shoemaker, is embarrassed to give his name or be photographed. His profound poverty is obvious in his own shoes, tattered beyond repair. “I can’t even afford to buy shoes,” he says. “We are barely surviving. We don’t see a chicken; meat is off the menu.”

In Lebanon, combating the ‘normalization of misery’

Zuhair looks despondently down at his feet, where the shoemaker’s profound poverty is obvious in his own shoes, tattered beyond repair, which he wears without socks.

“I can’t even afford to buy shoes,” he says. “We are barely surviving. We don’t see a chicken; meat is off the menu.”

Zuhair, who has big hands, a mishmash of teeth, and thick veins protruding from overly thin arms, refuses to be photographed or to give his full name. He expresses shame at how dramatically his life has been degraded by the economic collapse that began in October 2019, in Lebanon – a nation once trumpeted as the Switzerland of the Middle East.

Lebanon’s economic meltdown, brought on when the government defaulted on its foreign debt and the currency collapsed, triggered months of protests demanding deep political reforms and accountability from corrupt sectarian elites. Dubbed a “revolution” by the thousands of those who took to the streets, it resulted in little positive change.

The financial crisis was deemed so severe that the World Bank, in spring 2021, said Lebanon could be among the top three “most severe crisis episodes globally” since the mid-19th century.

The Lebanese people have been the subject of dire predictions of malnourished destitution. The impact of their country’s economic collapse has been compounded by a perfect storm of the pandemic, the massive 2020 ammonium nitrate explosion in the Port of Beirut that caused billions in damage, chronic political deadlock, and a ruling elite that analysts say has settled into a strategy of “doing nothing.”

“I can’t take it anymore. Every time I feel depressed and sick to my head, I go sit on the beach,” says Zuhair of the impact of his weekly earnings dropping from $300 to $50. He works in a small factory that produces 32 pairs of women’s shoes a day.

“Things got worse after the revolution because the people who run the country are a bunch of thieves,” he says. Before the crash, he and his family “had it all, used to go on picnics,” and could pay for meat, food, and their own rent.

Now his two teenage children can’t go to school because he can’t pay their annual fees of several hundred dollars.

“This country is gone,” says Zuhair. “It’s a misery.”

Daily challenge of survival

So how do Lebanese get by every day, in a system so broken that citizens hold up banks to retrieve their own cash; where the lack of fuel limits the police response to crimes; and where, in the southern city of Sidon, local officials have asked for firefighting help from a Palestinian refugee camp?

For Zuhair and his family – among the more than half of Lebanese people who have fallen under the poverty line for the first time in their lives – survival today means living in a house on loan from a friend. Without running water, it was only recently hooked up with enough electricity to power a lamp donated by neighbors.

Incongruously amid the poverty, the Port of Beirut is clogged with new cars, and streets in more affluent neighborhoods are plied by the latest-model Porsche, Lamborghini, and Ferrari sports cars.

“In Lebanon, we are seeing two split economies: We are seeing the wealthy are not losing significant amounts of money, and in fact are probably getting richer,” says David Wood, senior Lebanon analyst for the International Crisis Group in Beirut.

He notes suggestions of “renewed prosperity” on the back of data that the value of Lebanon’s imports has reached pre-October 2019 levels, though more reportedly is spent on importing cars than medicine.

“It’s damning,” says Mr. Wood. “We’re seeing that people who do have disposable cash are spending it on cars and watches and assets ... while for the majority of people in Lebanon, we are seeing the normalization of misery.”

Elites’ hold on power

Change appeared possible after 2019, but assumptions on the street proved not to be true, says Mr. Wood, that either the economic collapse would jolt the ruling elites into action, or that inaction by those elites would lead to massive civil unrest.

“The calculation has been made,” says Mr. Wood. “Lebanon’s elites have decided that any reforms they need to accept, that would impact their grip on power, are unacceptable, and that it actually serves their narrow self-interest to do nothing, rather than to risk losing control over a system which has served them so well for so long.”

Despite the lack of reform and grim economic statistics for ordinary Lebanese, the crisis has significantly expanded one area of government that appears to be working: two programs that provide cash assistance, administered via two social welfare programs.

The United Nations World Food Program (WFP) estimates that it supports one-third of all the people in the country, working largely through those government structures. Despite that support, a recent U.N. food security review found that a quarter of all those living in Lebanon, some 1.4 million people, are “food insecure.”

“That means they are in crisis mode, or in emergency mode,” says Antoine Renard, the deputy country director for the WFP in Lebanon. He says 112,000 people qualify as being under emergency status. “The challenge you have with this crisis is that what used to be the middle class has been wiped away, and then you have those who were poor, even before.”

What started as an emergency WFP response to the Syrian refugee crisis – Lebanon hosts the largest number of refugees per capita in the world – has expanded exponentially in recent years to provide sustainable support to cushion the blow of the multiple crises for Lebanese people, also.

Needs surged after the 2020 port blast, which caused damages estimated at $15 billion and left some 300,000 people homeless, prompting the WFP to provide direct and immediate aid through food parcels. It also facilitated a system of cash payments via a late 2021 World Bank loan called the Emergency Social Safety Net, which monthly provides $20 per individual to families in need, topped up by $25 per family.

Together, the WFP estimates that those Lebanese support programs have scaled up 35-fold since their inception. Cash is now provided to 700,000 people and food to 300,000.

“This is a protracted crisis,” says Mr. Renard. “Now we talk more and more with key ministries [and] with many other crises around the world; we have to speak about an exit strategy,” as the WFP shifts focus to more sustainable support of Lebanon’s food and social protection systems.

How far does the cash go?

Mounir Kahil and his family, who live by candlelight in a hovel in Beirut’s southern suburbs, are among those benefiting from the cash handouts. The former bus driver – who lost his job when the private school he drove for closed due to the 2019 economic crash – pulls a card from his wallet that he uses to withdraw $105 per month from the WFP-World Bank program.

It is not enough to cover all their needs, including $250 in monthly rent, for which Mr. Kahil says he has sold pieces of furniture and even downsized the family stove.

But the cash helps, along with a similar card issued by Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shiite militia, which enables big discounts for poor people in areas it controls at specific Hezbollah shops and pharmacies. Mr. Kahil’s wife also earns $7 each day during the school year, as a school cleaner.

“Everybody in this area has to fight for their family, for food,” says Mr. Kahil, who uses a sawed-off broom handle as a cane. “Ten years ago, we never thought it would be this way. Now we can’t even buy a Pepsi.”

Also helping Lebanese people get by are remittances from relatives abroad, which have recently grown to 53.8% of the country’s gross domestic product – the highest remittance dependency in the world.

“Remittances are definitely a big part of the answer to how Lebanese survive each day,” says Jacob Boswall, the team leader of Mercy Corps Lebanon Crisis Analytics in Beirut.

Remittances have for decades played an important role in the Lebanese economy, but prior to the 2019 crisis they were traditionally used to invest in productive assets, which helped boost the economy.

“What’s happening now is usage is almost exclusively being put toward survival, and that’s buying basic items like food, fuel, and paying rent,” says Mr. Boswall. That significant change is “deeply, deeply unequal” and polarizing, with very little sharing or distribution of remittances.

Not receiving remittances, and unaware of any cash or food handout scheme, shoemaker Zuhair describes a lack of support – and 90-minute walks to the nearest beach, where he can use his fishing rod.

Gone are the days when he could pay for a bus to Jounieh, the town just north of Beirut, where he used to fish on weekends. Or even pay for a ride to the nearby beach from his home in Beirut’s southern suburb of Dahiya.

“I don’t get paid much to begin with,” says Zuhair. “We have no other choice but to work. If we stop work, we literally don’t eat.”

The Explainer

Why this Sikh activist’s killing has divided India and Canada

The diplomatic drama unfolding between India and Canada has roots in a decades-old movement for an independent Sikh state – a vision that sparked immense violence in the 1980s and continues to color India’s foreign politics.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Both Canada and India expelled senior diplomats and issued travel advisories for their citizens this week after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau accused Delhi of assassinating Hardeep Singh Nijjar, who advocated for a separate Sikh homeland in northern India named Khalistan.

India calls the allegation “absurd.” But it takes separatist activism seriously. The Khalistan movement has a long history in Punjab, reaching a violent zenith in the 1980s with a slew of assassinations, anti-Sikh riots, insurgent violence, and a harsh police crackdown that left thousands dead and drove many Sikhs abroad. Most militant factions collapsed by the mid-1990s, but the movement never fully died.

Shinder Purewal, a political science professor in Canada who has studied the movement’s evolution in Western liberal democracies, says that while there’s little public sympathy for its historically violent tactics, the desire for autonomy remains strong among the Sikh diaspora. And in recent years, the rise of Hindu nationalism has helped reinvigorate interest in Khalistan as a political idea, both domestically and abroad.

“In comparison with the past, the movement is smaller and weaker,” he says. “However, the social media hype and years of nurturing relations with the Liberal Party of Canada has given them a louder voice in higher echelons of power.”

Why this Sikh activist’s killing has divided India and Canada

Relations between India and Canada have turned stormy after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau this week accused India of assassinating Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Canadian citizen who actively advocated for a separate Sikh homeland in the north Indian state of Punjab.

Mr. Nijjar, who migrated from India in 1997, was shot dead outside a temple in British Columbia in June. The Indian government had declared Mr. Nijjar a terrorist in 2020, accusing him of leading the banned militant group Khalistan Tiger Force.

Authorities in India have denied Mr. Trudeau’s allegations, calling them “absurd,” and warned India’s nationals of “growing anti-India activities and politically condoned hate crimes” in Canada. Both countries have expelled senior diplomats in response to the allegation, and issued travel advisories for their citizens in a tit-for-tat move. India has also suspended visa services for Canadian citizens.

Meanwhile, the escalating tensions have brought renewed attention to Sikhs’ demand for their own state, known as Khalistan.

What is the Khalistan movement?

The Sikh community’s call for an independent ethno-religious state dates back to the tail end of British colonial rule, though the Khalistan movement began to formally take shape in the late 1970s. Across Punjab, armed insurgents launched attacks on Indian police and army soldiers, and were effectively running a parallel government in the region.

The insurgency reached a violent zenith in 1984, when the Indian army stormed the Sikhs’ holiest shrine, the Golden Temple, and killed movement leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, who had fortified the temple and made it his headquarters. While the Indian government puts Operation Blue Star’s death toll at about 400, Sikh groups have argued that thousands were killed, including pilgrims.

Three months later, in retribution, India’s then-prime minister, Indira Gandhi, was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards, triggering riots in Delhi and other parts of the country that left thousands more dead.

Jagtar Singh, a Punjab-based journalist who has written two books on the Khalistan movement, says the killing of Mr. Bhindranwale made him an icon of the Sikh resistance, spurring support for independence but also leading to a harsh crackdown by Indian authorities.

In the chaotic years that followed, thousands of Sikhs – those affiliated with the Khalistan movement and those who weren’t – moved abroad to places such as the United Kingdom and Canada, which today is home to the largest Sikh population outside India. Some, like Mr. Nijjar, brought the Khalistani ideology with them. He sought refuge in Canada in 1997, and after working as a plumber for some time, he became a vocal activist.

Back in India, the aggressive counterinsurgency, as well as movement infighting, led most major militant factions to collapse by the mid-1990s, but the movement never actually died, says Mr. Singh.

Is the Khalistan movement still active today?

While things aren’t always peaceful in Punjab, priorities on the ground have largely shifted. Amandeep Sandhu, a Punjabi writer and journalist who has been closely following the movement, says people “have moved away from the demand of the Khalistan movement” and now want better governance and jobs.

Yet experts note that the rise of Hindu nationalism, especially in India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, has helped reinvigorate interest in Khalistan as a political idea, both domestically and abroad.

“The [original Khalistan] movement was mainly an armed struggle, which is not there right now,” says Mr. Singh. “There are people who continue to raise the issue at the political levels, including in the Parliament of India. The way it is happening now – affecting the national political discourse – it certainly has gained momentum.”

However, separatist violence still occurs, and India sees Khalistan activism – especially anything that could be linked to the Khalistan Tiger Force or other present-day militant groups – as a serious national security threat. Its quest to prevent future insurgencies often bleeds overseas.

Mr. Nijjar is not the first prominent Khalistan advocate to be killed on foreign soil. Two well-known Khalistani militants were also shot this year in Lahore, Pakistan, for which Sikh activists have blamed India. And Indian consulates in London and San Francisco were vandalized by Khalistan supporters in March after India launched a massive search for separatist leader Amritpal Singh.

World Sikh Organization board member Mukhbir Singh told a news conference in Ottawa, Ontario, on Tuesday that the revelation about India’s alleged role in Mr. Nijjar’s death was no surprise. “For decades, India has targeted Sikhs in Canada with espionage, disinformation, and now murder,” he said, adding that Canada needs to take stronger measures to protect its Sikh citizens.

What lies ahead for the movement, and diplomacy?

While many credit the powerful Sikh diaspora with keeping the Khalistan issue alive, some are skeptical about the movement’s future.

“The average Sikh migrants living abroad work hard to earn money; they send some money back to the family in Punjab,” says Mr. Sandhu. “And once in a while they go to gurudwaras [Sikh temples], many of which keep talking about Khalistan, [but] they are not actively pursuing Khalistan.”

Shinder Purewal, a professor of political science at the Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Canada, who has been studying the evolution of the Sikh secessionist movement in Western liberal democracies, agrees that there’s little public sympathy for the Khalistan movement’s historically violent tactics. But that doesn’t mean the desire for autonomy has disappeared.

“In comparison with the past, the movement is smaller and weaker,” he says. “However, the social media hype and years of nurturing relations with the Liberal Party of Canada have given them a louder voice in higher echelons of power.”

Even still, many believe the current India-Canada tensions are temporary, both because of the lack of a proper road map among Khalistan supporters and due to India’s geopolitical importance for the West.

Professor Purewal says Canada’s accusation will “have an immediate impact on bilateral ties, although sane voices will prevail in the long term because the U.S. and the West see India as a strategic partner.”

But some experts do not see the Khalistan movement dying down, at least not until Delhi finds a peaceful solution to address the concerns of Sikhs in Punjab.

“You cannot kill a political movement through police methods. It has to revive at some stage,” says Mr. Singh. When it comes to the thousands of Sikhs killed during the height of the Khalistan movement, he adds, “there has to be some accountability.”

Patterns

The fight to keep a world body relevant

Joe Biden was the only leader of a United Nations Security Council member to attend this week’s U.N. General Assembly. Can the international body retain its relevance in a rapidly changing world?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As the United Nations General Assembly opened this week in New York for the 78th time, there was plenty going on in the world that called for the sort of global response that the U.N. specializes in.

Climate change, an economic and debt crisis in the developing world, tension between the United States and China. Europe’s largest armed conflict since the end of the Second World War.

But U.S. President Joe Biden was the only leader of a U.N. Security Council member nation to show up. Just when cooperation seems most needed, many world leaders have been turning away from the internationalism that the U.N. embodies.

Instead, they are focusing their attention on smaller economic, political, or security partnerships they view as less unwieldy – and more directly aligned with their own interests.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres is fighting to keep the world body relevant; in his speech this week, he focused on climate change and poverty in the Global South as two key challenges where the U.N. can harness energy and resources.

The United Nations is not about to disappear. But Mr. Guterres is aware that for the kind of coordinated international action the U.N. hopes to galvanize, he needs full-throated buy-in from all its member states.

And that has by no means been forthcoming.

The fight to keep a world body relevant

You might call it the Paradox of Turtle Bay.

And how it’s resolved could go a long way to defining the future of the increasingly fragile international order put in place in the aftermath of World War II.

This week’s 78th gathering of the United Nations General Assembly – at U.N. headquarters in New York’s Turtle Bay neighborhood, on the East River – comes at a time when an array of challenges seems to demand exactly the kind of worldwide response for which the U.N. was created.

The list is daunting: climate change, an economic and debt crisis in the developing world, tension between the United States and China. And Europe’s largest armed conflict since the end of the world war, provoked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The paradox? Just when cooperation seems most needed, many world leaders have been turning away from the internationalism that the U.N. embodies.

They are focusing their attention on smaller economic, political, or security partnerships they view as less unwieldy – and more directly aligned with their own interests.

That was dramatically illustrated by the who’s who of leaders who did not come to New York this week.

U.S. President Joe Biden was the only leader of a permanent Security Council member nation to attend. The other four nations – China, Russia, Britain, and France – sent government ministers instead. So did India, the world’s most populous country and fastest-growing major economy.

Their diplomatic focus, of late, has been elsewhere.

For China, it has been on the expanding BRICS economic alliance, which also includes Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa. Leader Xi Jinping envisions it as part of an alternative to the post-World War II order largely crafted by the U.S.

Russia’s focus has been closer to home, on its core Ukraine-war allies: China, Belarus, and the latest, North Korea.

Leaders of Britain and France, despite sharing Mr. Biden’s hope for a reinvigorated, more effective U.N., have increasingly prioritized other forums since the Ukraine war, such as NATO, the G7 group of the world’s leading economies, and the wider G20 economic grouping.

And Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent priority has been to assert his country’s leading role within the so-called Global South.

This week’s U.N. diplomacy showcased one of the world body’s unique strengths – gathering representatives from every nation on Earth to highlight issues on which joint action is urgently needed. But it came amid growing pressure on the institution to adapt to a changing world, in two ways above all: to give a greater voice to the Global South, poorer and middle-income nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and to free the U.N.’s top decision-making body, the Security Council, from the stalemating veto power of its five permanent members.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres has delivered a powerful twin message this week: Reinvigorated worldwide action is essential on climate change, economic development, and the Ukraine war – and the U.N. itself must adapt to a world that looks nothing like it did 80 years ago.

President Biden, addressing the general assembly, echoed both themes.

So did Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, with particular force, in the Security Council. As Russia’s U.N. ambassador looked on, he decried the “veto power in the hands of the aggressor,” adding that “Ukrainian soldiers are now doing with their blood what the U.N. Security Council should do with their votes.”

Yet it’s not just problems in the Security Council that are limiting the U.N.’s influence and effectiveness. It’s the competing attraction, for many nations, of other, narrower partnerships.

The United Nations is not about to disappear.

It still plays a uniquely important role on a range of issues – providing humanitarian assistance, peacekeeping, conducting nuclear inspection, and upholding international law. It is the only forum for all the world’s nations, bound by a shared charter of principles and human rights, and with the power to lend an international imprimatur to the use of armed force.

Mr. Guterres this week underscored two urgent policy challenges.

The first was climate change, for which he called to hold accountable the G20 states, China and the U.S. included, which are responsible for four-fifths of the world’s carbon emissions.

The second was the huge pressures on countries in the Global South, as the U.N.’s wealthier members lag badly on the 2030 sustainable development goals they agreed to in 2015.

On most of the goals – eradicating extreme poverty, ensuring secondary school education, ending gender inequalities, and improving environmental policies – things are far behind schedule. Some African states spend more on debt interest than on public health.

The U.N. chief has sought to enlist help from potentially competing diplomatic forums: the G7, for more debt relief to the world’s less developed nations, and the G20, to put more money towards funding the development goals.

But he is aware that for the kind of coordinated international action that the U.N. hopes to galvanize, he needs full-throated buy-in from all its member states.

And that has by no means been forthcoming.

Scholarships, friends: College students score with esports

Esports is offering U.S. campuses a way to attract more students – and to keep them by building a sense of belonging.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

During the pandemic, college sports lost many millions of dollars, resulting in schools having to shutter programs.

But that was not the case for collegiate esports, or competitive video game playing, which has been on campuses for about a decade and is thriving along with the billion-dollar industry it helps feed. For students, esports offers a way to earn scholarships – to the tune of $16 million in 2022 – and build community. For the hundreds of schools that participate, it is a pipeline for filling classes.

In Pennsylvania, the Arcadia University program has more than 50 players, with scholarships ranging from $500 to $10,000 per semester.

“From esports I get a sense of belonging with the community from everyone here,” says senior Corey Klevan, a computer science major.

In Idaho, Boise State University’s esports team started in 2017. The program’s first two years saw challenges from parents skeptical about its usefulness. But watching their kids get scholarships, as well as name, image, and likeness deals, helped change minds.

“Parents have figured it out fast,” says Chris “Doc” Haskell, the program’s co-founder. “Two years has been the distance between when they didn’t really trust it to now they come in as their child’s No. 1 advocate.”

Scholarships, friends: College students score with esports

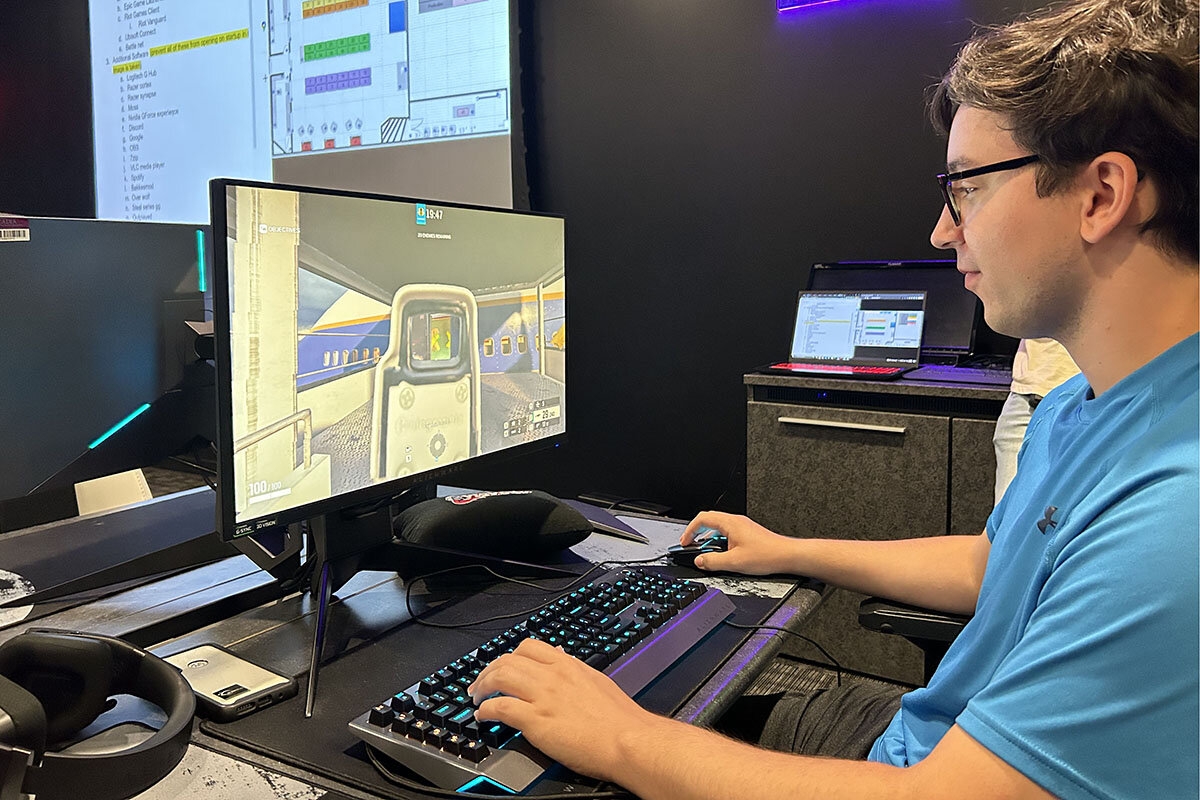

Sean Ey’s left hand clicks a computer keyboard with the adroitness of a court reporter taking notes. His right hand cups a mouse that his fingers tap with equal deftness.

He is playing a video game as a soldier hunting artificial intelligence-generated enemies inside an empty airplane. They trade fire with heavy machine guns until his avatar is felled. His PC screen taunts him with the words, “Mission Lost.”

Mr. Ey isn’t home playing among friends. He is at college, flanked by coaches who steer thousands of dollars toward his education each year to play video games for them. Mr. Ey, a junior computer science major at Arcadia University just outside Philadelphia, is part of the rapidly growing collegiate esports world.

“I’ve played video games since I was 4, so it’s been a massive part of my life,” he says. “I’ve met so many people, and to be able to do it in this style and play at such a competitive level, it’s great.”

During the pandemic, college sports lost many millions of dollars, resulting in schools having to shutter programs. But that was not the case for esports, which has been on campuses for about a decade and is thriving along with the billion-dollar industry it helps feed. For students, esports offers a way to earn scholarships – to the tune of $16 million in 2022 – and build community via club and varsity competition. For the hundreds of schools that participate, it is a pipeline for filling classes.

“The benefit of having an esports program at a university is obviously it’s going to drive enrollment,” says Nick Alverson, director of esports at Arcadia.

Michael Brooks, executive director of the National Association of Collegiate Esports, which governs esports – rather than the NCAA – says boosts in enrollment can be the gift that keeps giving for both students and universities.

Transferable skills that students gain from esports, he says, include familiarization with digital platforms, learning how to broadcast, and how to do graphic overlays, stream online, and manage online communities.

“These are the exact same skill sets that are incredibly in demand by companies right now,” he says, “with so few schools offering specific curriculum to develop those.”

The National Association of Collegiate Esports started in 2016 with varsity programs in six schools. Today, there are 217 campuses with varsity standing. In addition, the association oversees the Starleague in the United States and Canada, which is made up of more than 775 colleges, a majority of which don’t yet have varsity teams. It also tracks the overall amount of scholarships awarded for esports.

Championships are held for varsity and club teams at the end of every semester for 17 esports, including games such as Super Smash Brothers, Rocket League, Call of Duty, and Rainbow Six Siege. Games can include card games, war games, shooting games, racing, and one-on-one combat.

“A sense of belonging”

In Pennsylvania, the Arcadia University program has more than 50 players, with scholarships ranging from $500 to $10,000 per semester.

“From esports I get a sense of belonging with the community from everyone here,” says senior Corey Klevan, a computer science major.

His parents were skeptical about his recruitment out of high school to play Hearthstone, a multiplayer, strategy-based card game in which players can cast spells, fight in duels, and summon special characters to fight for them.

“I didn’t like reading and would refuse to read. And [my parents] would yell at me to get off the games. And then like, lo and behold, I’m getting a scholarship to play video games,” says Mr. Klevan with a laugh.

The past three years playing esports have helped him collect good friends and rack up memories. Mr. Klevan, who is the captain of the campus self-defense club, says esports helped him deal with confidence issues and socializing. He doesn’t see a professional career in esports in his future. His mother has gone from indifferent to on board with his playing video games in college. As for his father’s demand for good grades – well, he has a 3.77 GPA.

Traditionally, schools used to market their attractiveness with big-name sports programs, says Mr. Brooks of the esports association. But a burgeoning gaming population was being ignored. The internet was a game changer for multiplayer competition – no longer did people have to share the same physical space to play together.

“Finally the recognition came – and I think it was late, actually – that if that’s what our customers are identifying with, if that’s where their passion is, if that’s where they’re investing their time and energy, then we should provide value that matches with that interest,” Mr. Brooks says.

Sponsorships and advertising revenue have ended up funding esports programs at many colleges, including some schools partnering with game publishers for naming rights to esports arenas. The University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, for example, debuts a new arena this semester.

Gaming in style

In Boise, Idaho, 25 members of the esports team compete inside the 7,000-square-foot Boise State Esports Arena. In the three-story building – across from a hotel, a Trader Joe’s market, and various takeout and sit-down restaurants – battles are fought in Overwatch and Valorant, two first-person shooter games; and Rocket League, a vehicular soccer game. The main theater is decked out with leather seats for spectators, and the building offers a Battleground area for intramural use and for the general public.

The broadcast control room, with its assortment of screens, looks like the command center for a NASA shuttle launch. It is complemented by the Studio, a designated space with furniture and a large projector screen where players can be interviewed.

Chris “Doc” Haskell co-founded the program in 2017. He was an educational technology professor and games researcher. Today Boise’s esports program makes top 10 lists, such as a recent one from esports promoter nerdstreet.com, and another from BestColleges.com.

“I was doing some research for a keynote I was going to give on other ways to use games,” Dr. Haskell says. He realized that esports had the potential to really take off. “I discovered it was going to get massive, like, oh my gosh, this is going to be huge. And we should do something about it.”

Boise State University’s esports program started on a shoestring budget, which has grown to $500,000 annually. It now offers $150,000 in scholarships each academic year, ranging from as little as $500 to $1,000 per semester to full rides, Dr. Haskell says. Advertisers and local businesses have flocked to its broadcast operation, which reaches more than a million eyes per month and broadcasts 30 to 40 hours of live content weekly.

Students benefit in a plethora of ways, Dr. Haskell says.

“We are a platform for other departments to inject their curriculum into, so communications, athletic training, athletic leadership education, computer science, cybersecurity, all have elements that they can bring in and use,” he says.

Varsity members on BSU’s esports team must keep a 3.0 GPA to play. That is a selling point to parents. The program’s first two years saw challenges from parents skeptical about the program’s usefulness. Now, watching their kids get scholarships, and name, image, and likeness deals, is all the empirical evidence needed to make them do an about-face.

“Parents have figured it out fast,” Dr. Haskell says. “Two years has been the distance between when they didn’t really trust it to now they come in as their child’s No. 1 advocate.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The balm after the blow in Libya and Morocco

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

When a catastrophe exposes a society’s poor governance, personal anguish can turn to anger. In recent days, Libyans have gathered in protest following last week’s disastrous flooding in the eastern city of Derna and other coastal towns. Their demands for accountability give voice to enduring aspirations for public integrity. “We feel this is a moment of change,” said Elham Saudi, director of Lawyers for Justice in Libya.

One institution in Libya showing such civic spirit is the Boy Scouts. Since the flooding, caused by the collapse of two dams during a massive storm, roughly 500 Scout leaders and their troops have arrived in Derna from around the country. They have filled an essential gap, distributing relief supplies, helping families, and organizing games for children.

Selflessness in Arab societies has a centuries-old tradition in the practice of hospitality. A similar warmth has been evident in Morocco in the two weeks since an earthquake struck outside the historic city of Marrakech.

The work of rebuilding from disasters starts not with bricks and mortar, but with countless unheralded acts of sacrifice.

The balm after the blow in Libya and Morocco

When a catastrophe exposes a society’s poor governance, personal anguish can turn to anger. In recent days, Libyans have gathered in protest following last week’s disastrous flooding in the eastern city of Derna and other coastal towns. Their demands for accountability give voice to enduring aspirations for public integrity. “We feel this is a moment of change,” Elham Saudi, director of Lawyers for Justice in Libya, told The New York Times.

The basis of that change, however, may reside less in the outrage than in quieter ways. One example from the past is how New Orleans recovered from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. “If people can rally themselves to cross social barriers, ... [they] can ... cause institutions to do the same,” one study found. Its authors, Drew University English professor Amy Koritz and Carol Bebelle, a community arts supporter, wrote that the greatest challenge in post-disaster rebuilding is “of imagination, faith, and spirit.”

One institution in Libya showing such civic spirit is the Boy Scouts. Since the flooding, caused by the collapse of two dams during a massive storm on Sept. 11, roughly 500 Scout leaders and their troops have arrived in Derna from around the country. They have filled an essential gap, distributing relief supplies, helping families, and organizing games for children. They were welcomed because the Scouts are largely apolitical and have “a culture of selflessness,” Emadeddin Badi, an analyst on Libya at the Atlantic Council, told Middle East Eye.

Selflessness in Arab societies has a centuries-old tradition in the practice of hospitality, which is defined “as an act of unconditional surrender to the needs of others,” according to a scholar of Islam, Snjezana Akpinar.

A similar warmth has been evident in Morocco in the two weeks since an earthquake struck outside the historic city of Marrakech. “People’s hospitality is inspiring,” Hana Elabdallaoui, an Islamic Relief aid worker, said of residents in the village of Douar Tedcharte. “They have lost almost everything but are still willing to share what little they still have. In the villages people offered us cups of tea. It’s an example for all of us that no matter how hard life is, you can always find a way to be kind to others.”

In Derna, protesters have not only demanded the resignation of public officials they blame for the collapse of the dams. They have also chanted, “All Libyans are brothers.” That cry marks a rejection of the factional divisions that have destabilized Libya for more than a decade. As Noura Al Jerbi, a Libyan women’s rights activist, told the United Nations just weeks before the flooding, the basis of the country’s renewal resides in forging a path “where every voice is heard, every life is valued and the bonds of our shared humanity are unbreakable.”

The work of rebuilding from disasters starts not with bricks and mortar, but with countless unheralded acts of sacrifice.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Embracing peace

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

In learning more about the universal God of peace and letting divine inspiration guide us, each of us can play a part in nurturing unity, healing, and harmony – on the International Day of Peace, and every day.

Embracing peace

The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance: against such there is no law.

– Galatians 5:22, 23

Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you.

– John 14:27

Through divine Science, Spirit, God, unites understanding to eternal harmony. The calm and exalted thought or spiritual apprehension is at peace.

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 506

Viewfinder

Let the games begin!

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. Please come back tomorrow for our look at the autoworkers strike in the United States. It is about fairness and regaining the promise of strong middle-class lifestyles, but there’s tension over how much the workers can gain, with car prices already high.