- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The seeds of a new love story

Ken Makin

Ken Makin

I have often heard alumni of historically Black colleges and universities say that HBCUs molded them or even made them when it comes to their professional careers.

When I say that “HBCUs made me,” I’m speaking more literally. My parents met at what is now South Carolina State University, a historically Black school and land-grant institution, in the early 1970s. Without SCSU, I wouldn’t be here.

I was reminded of my land-grant roots when the U.S. secretaries of education and agriculture called for 16 state governors to equitably fund land-grant HBCUs last week. That declaration – and a $12 billion disparity – ring loudly during a period the Biden administration has designated as HBCU Week.

My love and appreciation for HBCUs goes beyond the familial and the familiar. (I attended land-grant HBCU Florida A&M University some 30 years after my parents met.) The role and relevance of Black schools speaks to a more radical love – the desire and urgency to educate Black children.

This is why a Second Morrill Act was needed. The First Morrill Act of 1862 set aside state funding for the establishment of land-grant universities. But it excluded Black people. Saying that Black institutions have done more with less would be an understatement. Aside from the profound financial gap, HBCUs have dealt with threats both foreign and domestic. My parents met only a few years after the Orangeburg Massacre at South Carolina State.

Nevertheless, these houses of Black education, rooted in radicalism, have persevered. Beyond their role in the making of professionals, HBCUs continue to be havens for community and conscience, seeing a noticeable uptick in enrollment since the summer of discontent in 2020.

In that way, the $12 billion gap could be considered “seed funding,” not only addressing the generational underfunding of Black schools, but also cultivating the next chapter of HBCU love stories.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Bidenomics’ boosts jobs and green energy. Do voters care?

Good jobs and reliable infrastructure propel prosperity. People notice when they’re missing but don’t always remember them in the voting booth.

Once completed, a 786,000-square-foot building along Interstate 75 in Dalton, Georgia, will be part of the largest solar-cell manufacturing facility in North America. It’s among a slew of investments that have made Georgia an emerging hub for clean-tech manufacturing, including electric vehicles and the batteries that power them.

The same highway, I-75, connects Georgia to Detroit, the traditional automaking hub. Along the way, though, truckers must cross the Ohio River on a bridge that is a notorious bottleneck for freight worth $1 billion that passes through daily. For decades, efforts to replace the bridge have failed. But last year, federal funding was secured, and work is due to start this year.

What links both projects – apart from I-75 – is legislation signed into law by U.S. President Joe Biden that provides hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies, loans, and grants for infrastructure, green-tech industries, and semiconductors.

Mr. Biden’s economic agenda, branded “Bidenomics,” could prove transformative in nurturing new industries. But critics see a risky departure from decades of putting restraints on government and letting the market set economic priorities in the United States.

Early indicators of success include a dramatic increase in private investment in industrial plants and a big jump in manufacturing employment, which is at its highest level since 2008.

Harder to gauge is whether voters will credit Mr. Biden for this activity and repay him at election time.

‘Bidenomics’ boosts jobs and green energy. Do voters care?

Beside a highway, a single industrial building under construction spans several city blocks. Atop its flat roof, dozens of heating and cooling units sit like biscuits, neatly spaced on a sheet pan baking under the sun. The tree-lined site, which crawls with bulldozers and trucks, is visible from Interstate 75 as it cuts through the Appalachian foothills of northwest Georgia.

Once completed, this 786,000-square-foot building in Dalton will be at the heart of the largest solar-cell manufacturing facility in North America, capable of producing enough solar panels annually to power nearly 1.3 million homes. Hanwha Qcells, a South Korean company, already builds solar panels inside an adjacent plant that began operating in 2019. Another production facility is under construction in Cartersville, 30 miles south along I-75.

All told, Qcells is investing $2.5 billion in Georgia. It’s among a slew of companies that have made Georgia an emerging hub for clean-tech manufacturing, including electric vehicles and the batteries that power them. Meeting part of America’s growing demand for electricity with solar and other renewable energy is essential to reducing emissions of heat-trapping gases.

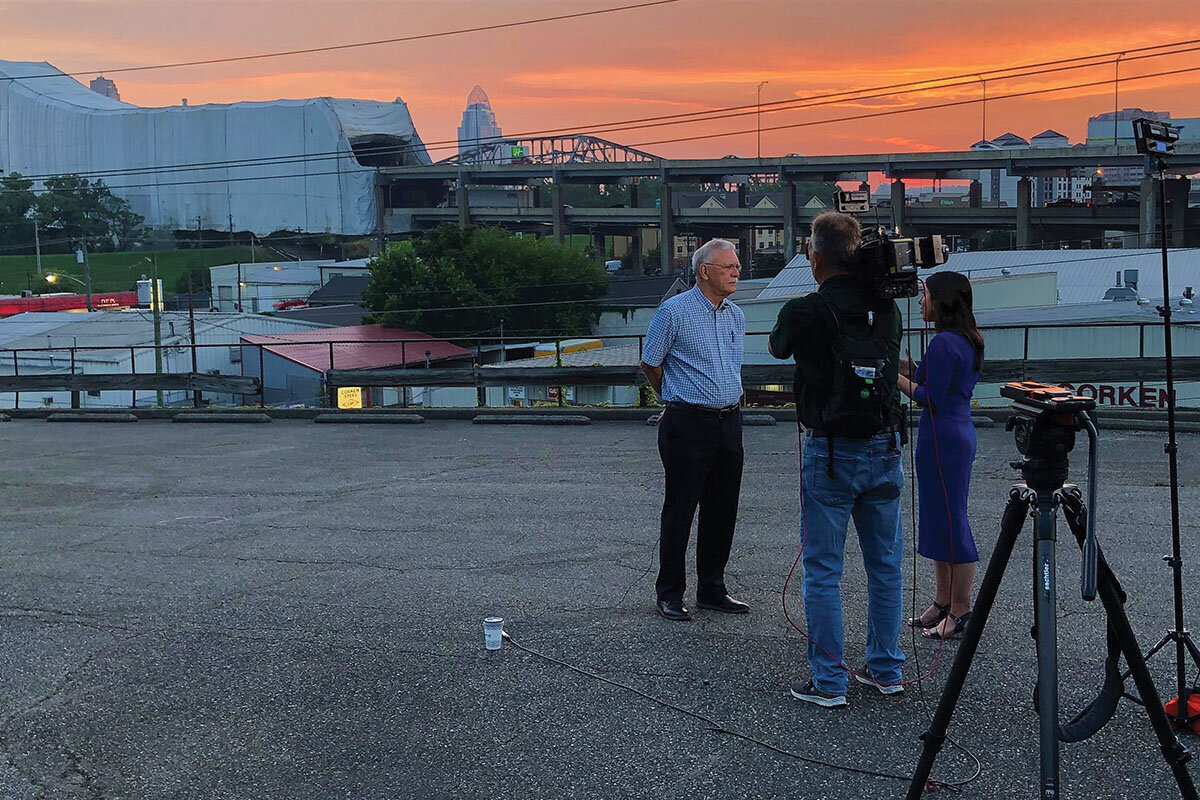

The same highway, I-75, connects Georgia to Detroit, the traditional automaking hub. Along the way, though, truckers must cross the Ohio River on a bridge known for accidents that is a notorious bottleneck for freight worth $1 billion that passes through daily. Built in 1963, the Brent Spence Bridge carries around 160,000 vehicles a day between Cincinnati, Ohio, and Covington, Kentucky, twice the number it was designed to carry.

Dave Baker joined the Iron Workers union in Cincinnati in 1997. “I was told we were going to build a bridge,” he says. Politicians promised action. Planners drew designs. Nothing happened. And the Brent Spence Bridge became a symbol of partisan gridlock in Washington and a daily reminder of America’s decaying public infrastructure.

Last year, federal funding was secured for a $3.6 billion replacement of the bridge and parts of its adjoining highways. Work is due to start this year, and Mr. Baker’s ironworkers will finally be put to work on a new bridge. “To say that it’s overdue is kind of an understatement,” he says.

What links both projects – apart from I-75 – is legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden that provides hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies, loans, and grants for infrastructure, green-tech industries, and semiconductors. This gusher of public money is designed to unlock even larger flows of private capital so that the United States retains its competitive edge in manufacturing and its economy lifts more families into the middle class.

President Biden has taken to branding his program “Bidenomics” and to contrasting it with what he calls the failure of “trickle-down” policy to spread wealth. In a speech in Chicago in June, he said public investment was essential to drive long-term growth, and he compared his infrastructure law to the Interstate Highway System built in the 1950s and 1960s. “Biden economics means the industries of the future are going to grow right here at home,” he said.

While his branding may be premature, Mr. Biden’s agenda could prove transformative, both in nurturing new industries and, arguably as importantly, in breaking with decades of putting restraints on government and letting the market set the nation’s economic priorities. Under President Ronald Reagan, this orthodoxy – often called neoliberalism – prioritized free trade, limited government, and unfettered capital. It commanded fealty from Republicans and Democrats alike. To dissent was to be branded a big-government heretic who would imperil the money machine of capitalism.

That makes the shift under Mr. Biden, a Democrat from the party’s center, all the more profound.

While Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama largely adhered to the post-Reagan economic playbook, Mr. Biden has embraced a far more interventionist approach, says Gary Gerstle, an American historian at the University of Cambridge. “I think he has a sense that America is at an inflection point” – a point, he adds, where the “neoliberal economics of Clinton and Obama are no longer suitable ... for an America that needs a different and more ambitious agenda.”

Jennifer Harris, who served for two years as senior director for international economics and labor on Mr. Biden’s National Security Council, calls his agenda “a revolution in economic ideas” that upends the neoliberal approach. “We’re living now in an experiment around industrial policy [and] the power of fiscal policy to solve what needs solving,” she says.

The White House can point to early indicators that its experiment is working. From May 2022 to May 2023, private investment in industrial plants rose to $200 billion, triple the yearly average seen in the 2010s. Manufacturing employment has risen to nearly 13 million jobs, its highest level since 2008. Barely a week goes by without the announcement of a new clean energy project.

Harder to gauge is whether voters will credit Mr. Biden for this activity and repay him and his party at election time. Infrastructure projects typically take years to complete. Many of the new factories are being built in conservative states like Georgia where Republican leaders lambaste the president and obscure the role his policy plays in attracting investments. And voters are still reeling from high inflation and the higher interest rates applied to reduce it.

Even if Biden-backed projects provide concrete benefits, that may not be persuasive in a distrustful, polarized democracy, says Ted Strickland, a former Democratic governor of Ohio. “For some people, a road or a factory ... may move them in how they’re going to vote. But I think, unfortunately, for most people it’s going to be based on, are you on our team or the other team?”

Mr. Biden is already campaigning on his economic policies and his belief in their power to improve people’s lives. His chance of winning a second term, and of making his transformations stick, may depend on how many voters share his belief that Bidenomics can deliver.

It was January 2018, and Carl Campbell had a problem.

It took the form of a 184-acre industrial park along I-75 on the outskirts of Dalton, Georgia, a town that for decades had grown wealthy making carpets for homeowners who expected wall-to-wall carpeting. After the housing bubble popped in 2007-08, putting hundreds of carpet-mill employees out of work, the county government drew up a diversification plan. It was time to roll out a welcome mat in the “Carpet Capital of the World” for other types of factories.

As executive director of the Dalton-Whitfield County Joint Development Authority, Mr. Campbell had to find tenants for the industrial park, a former campground the county had purchased in 2010. Now, eight years on, there was nothing to show for its investment. Auto-industry suppliers and other manufacturers checked it out, and the site often made their shortlist. But they all chose to build factories elsewhere. Dalton was always the bridesmaid, never the bride, and Mr. Campbell and the county commissioners were feeling political pressure.

But then, in January 2018, President Donald Trump – who in his inaugural address said “protection will lead to great prosperity and strength” – slapped tariffs of 30% on imports of solar cells, hitting producers in China and South Korea. Shortly after, Mr. Campbell heard that Qcells was looking for sites in Georgia.

By February, he was sitting down with representatives from the company, who told him they wanted a plant to be operational in a year. “They were on a really fast timeline,” Mr. Campbell says.

The first Qcells factory opened on time in early 2019 and created 600 jobs, with entry-level wages starting at $15 per hour. This was above what Dalton’s carpet and flooring mills were paying, says Mr. Campbell.

Landing Qcells didn’t quell the criticism, though. For one, the Korean firm received a 10-year tax abatement on its 480,000-square-foot plant, so the county was still in the red. And why should a solar company receive subsidies when carpet manufacturers employed far more workers, many residents wondered.

“I’m not sure how you create wealth by giving money away to a foreign company,” says David Pennington, the Republican mayor of Dalton who ran for governor in 2014.

This argument mirrors the wider debate about government intervention, from trade barriers to protect domestic producers to tax incentives for favored industries. To neoliberals, such policies distort the economy and put too much power in the hands of bureaucrats and politicians.

“If you subsidize something, you get more of it. But I think you get too much of it, generally. And what you get is often not cost-effective,” says Donald Boudreaux, an economist at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia.

Under President Biden, this debate has intensified. In 2021, he signed into law the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which includes financing for clean energy projects. This was followed in 2022 by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which offers at least $370 billion in subsidies for solar, wind, nuclear, and other low-emissions technology. Next came the CHIPS and Science Act that subsidizes new semiconductor plants, primarily in Texas, Arizona, and Ohio.

This Bidenomics legislation was largely opposed by Republicans. The IRA passed the House on a Democratic party-line vote. The infrastructure law, which was co-written by then-Sen. Rob Portman, a Republican from Ohio, had support from 19 Senate Republicans, but only 13 House GOP members.

Among those opposed was Marjorie Taylor Greene, a far-right Republican who represents the district in which Dalton sits. She tweeted the names and telephone numbers of the 13 “traitors” who voted for the infrastructure bill. Some later reported receiving death threats over their vote.

After the IRA became law, Qcells began negotiations to expand in Dalton. This time, the county struck a harder bargain: Tax relief would be capped at 50% over 10 years, with revenues earmarked for public schools. Hourly wages would start at $19 an hour, rising to $20 after a trial period.

Qcells says the IRA’s clean-tech incentives are the reason it is expanding. Marta Stoepker, a Qcells spokesperson, says that state and local support in Georgia has been “really important,” but the IRA “gave us the market certainty we needed to make critical investments.”

Like many Republicans, however, Jevin Jensen, chair of the county commission, is skeptical of Mr. Biden’s economic agenda. He gives the IRA little, if any, credit for Qcells’ expansion. “I think we would’ve closed the deal regardless,” he says.

What attracts manufacturers to Georgia isn’t just subsidies. Land and electricity prices are lower than in the Northeast and California, and Georgia offers easy access to ports and highways, like I-75.

Another factor is labor costs and union contracts. Georgia and other Southern states are “right-to-work” states with low unionization rates. Since the IRA was passed, Georgia has announced clean energy manufacturing projects worth almost $12 billion, more than any other state, in addition to preexisting commitments to build EV and battery factories.

Some of these projects may be built using union labor. But Georgia has a unionization rate of 4.4%, compared with a national average of 10%. Qcells has no labor union in Dalton.

Mr. Biden frequently talks about creating “good union jobs” in a decarbonized economy. “I promised to be the most pro-union president in history. And I tell business leaders all the time: Our union workers are the best in the world,” he said in Chicago.

So far, though, the vast majority of clean-tech factories eligible for federal subsidies are located in Republican-run, right-to-work states that voted for Donald Trump in 2020.

For Mr. Biden’s labor allies including the United Auto Workers, whose members launched a strike on Sept. 15, a subsidized stampede by manufacturers into states seen as hostile to unions is a source of tension. Under the IRA, enforcement of rules on labor standards lies with the Treasury Department, and the rules are still “a work in progress,” says Damon Silvers, a senior adviser to the president of the AFL-CIO, the federation of U.S. labor unions.

“The statute is not as strong as it should be and this creates a very serious problem, which is the problem of some manufacturing companies wanting to take public money and then pay poverty-level wages and not respect workers’ legal rights,” he says.

This could have political implications for the president and his climate policies. “The only way that people are going to support this critical agenda is if it creates good jobs. If it creates bad jobs, the public will not, in the end, support it,” says Mr. Silvers.

From another vantage point, though, a red-state boom in strategic industries is a political strategy, one that could keep Mr. Biden in power and extend his economic legacy.

Take the computer chips that the U.S. imports from Asia. In Arizona, facilities planned or under construction by Intel, a U.S. chipmaker, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which dominates global production, represent a total investment of $60 billion. Meanwhile, Georgia is adding tens of thousands of jobs in EV plants and other clean-tech industries. Both states are presidential battlegrounds that Mr. Biden flipped in 2020.

Professor Gerstle, the Cambridge historian, sees an “electoral strategy” salted into an industrial policy. “The macro strategy is to re-shore in America. The micro strategy is, which states do we target? And the Biden administration is clearly targeting red states with the hope of electoral payoffs.”

But Mr. Biden insists that his economic programs are designed to benefit everyone, regardless of where they live or how they voted. “I promised to be a president for all Americans,” he said in June at the announcement of a $42 billion plan for broadband coverage under the infrastructure law. “We’re not going to leave anyone behind.”

“Look over there; that’s the lost Seventh Street.”

Brian Boland, an urban planning activist, is driving around Cincinnati’s west side, a drab wedge of warehouses and parking lots near downtown. This was once a thriving Black neighborhood. But catastrophic flooding in 1937 was followed by postwar highway building that displaced thousands of residents, clearing the way for I-75 and the superannuated Brent Spence Bridge.

The reconfiguring of cities for transportation projects comes at a cost that has historically been borne by disadvantaged communities. In the 1950s, planners routed highways around and through majority-Black districts, creating physical barriers that reinforced racial segregation and divided communities. Homes, schools, and churches were bulldozed for highway construction.

The infrastructure law signed by President Biden provides $1 billion for cities to reconnect cutoff neighborhoods, as a way to rectify this racist history.

Mr. Boland has a proposal for using some of that money. His advocacy group, Bridge Forward, wants planners to shrink the Brent Spence Bridge project’s total footprint and reconnect Cincinnati’s west side via a new district built on reclaimed land over underground highways. “A quality urban neighborhood, safe and connected – that’s what people want,” he says.

His vision isn’t shared by local business leaders who, after decades of waiting, are wary of costly redesigns that could hold up construction. Mr. Boland admits that his design would cost more, but he argues it would benefit Cincinnati residents. “We can make sure that everything we do going forward is inclusive and everyone gets a chance to get a share of prosperity,” he says.

Across the river, the mayor of Covington, Joseph Meyer, can sympathize. He’s also trying to improve connectivity, while making sure highway planners don’t carve up more districts. So far, he’s happy with the design of the replacement bridge – the current bridge will be reconfigured for local traffic – and with the promise of noise barriers and storm sewers.

Mr. Meyer, a Democrat, remembers vividly that neither President Obama nor President Trump succeeded in securing funding for a new bridge. “Biden came through when nobody else did,” says Mr. Meyer, a former state lawmaker. He “provided the national leadership to get it done.”

As for political benefits, however, Elizabeth Mason-Hill, a paralegal who sometimes spends 45 minutes commuting 7 miles due to bridge traffic, doubts voters will express much gratitude. “Biden will definitely get credit from Democrats, but the Republicans here won’t give him any credit,” she says.

Interstate 71 also crosses the river using the Brent Spence Bridge, linking Louisville, Kentucky, to Columbus and Cleveland, Ohio, where John Rockefeller began refining oil, the commodity that built the modern industrial economy.

The digital economy runs on another commodity: semiconductors, or computer chips. Every electronic device and system runs on chips. They’re embedded in cars, phones, fridges, and credit cards, which is the reason shortages during the pandemic wreaked havoc on manufacturers.

Just off I-71 outside Columbus, Intel broke ground last year on a sprawling $20 billion semiconductor facility with funding from the CHIPS act, a plank of Bidenomics that is as much about geopolitics and national security as it is about manufacturing jobs. Federal support for domestic production goes hand in hand with the Biden administration’s efforts to curb China’s ability to produce the advanced chips used by supercomputers for technologies like generative artificial intelligence.

“The United States has to lead the world in producing these advanced chips – this law is going to make sure that it will,” Mr. Biden said in September 2022.

That goal has broad support in Washington, where concern over China’s competitive edge in civilian and military technologies is top of mind. The bipartisan consensus on China is likely to safeguard the law, which passed the Senate in 2022 with 17 Republican votes, from any reversal by Congress under a future administration.

But Mr. Biden’s broader agenda to build a low-emissions economy and to support made-in-America manufacturing may be more vulnerable, with its addition to the national debt making it an easy target. House Republicans have threatened to repeal his climate-related legislation. During debt limit negotiations in April, Speaker Kevin McCarthy proposed ending subsidies for producers of wind, solar, and other green technologies.

Ms. Harris, the former Biden administration official, worries that his programs could be uprooted prematurely if he loses in 2024, allowing the Republicans to wrest back control. “These are early days for an experiment this massive through the entirety of the U.S. economy. You need at least a few years to see how it’s playing out,” she says.

Mr. Biden’s policies poll well individually, with 65% in favor of expanded tax credits for installing solar panels, for example, according to a July poll. But the White House has struggled to gain credit.

In April, Vice President Kamala Harris traveled to the Qcells factory in Dalton to announce the sale of 2.5 million solar panels that will be installed across the country. She also praised the company’s planned expansion and creation of 2,500 jobs in Georgia. Jan Pourquoi, a local Democrat who owns a carpet company, attended the event. Not a single GOP official showed up, he says.

Mr. Pourquoi, a former Republican who left the party under Mr. Trump, doubts the Democrats’ ability to sell the president’s climate agenda in Georgia. “In the rural South, it’s a nonstarter. Green policies will not get Democrats one extra vote,” he says.

What resonates with voters are cultural and social issues pushed by Representative Greene, the firebrand congresswoman. “That’s the news” in Dalton, he says.

Ms. Greene, who took office in 2021, visited Qcells in Dalton in August and has voiced support for the company. “Those jobs were jobs in my district under the Trump administration,” she told Politico, while denying the IRA’s subsidies spurred Qcells’ expansion.

That a solar panel factory has been built on the back of policies of Republican and Democratic administrations – tariffs imposed by Mr. Trump and legislation signed by Mr. Biden – suggests that the shift in economic thinking represented by Bidenomics may endure longer than his presidency.

Analysts say President Trump’s dismissal of the GOP’s free trade platform and his readiness to protect domestic industries – policies championed on the left by Sen. Bernie Sanders – have seeded an economic populism on the right. Unfettered markets and limited government are out. Industrial policy and economic nationalism are in.

“There’s a different kind of thinking going on in parts of the Republican Party, which convinces me that this is not just the Democratic moment,” says Professor Gerstle. “It’s something bigger and deeper that both parties will be reckoning with over the next 10 or 15 years.”

To Professor Boudreaux, the economist, this rebuttal of neoliberalism is alarming. He worries that, far from unraveling Mr. Biden’s agenda, the new guard of Republicans may extend its lifespan because they no longer view industrial policy as a nonstarter. Classical economic liberals, as he calls himself, “are feeling pretty lonely at the moment,” he says.

This debate on the right is reinforced by facts on the ground. Replacing the Brent Spence Bridge has a social and economic impact that goes beyond Cincinnati, says Rep. Greg Landsman, a Democrat who represents the city in Congress. A new bridge “will make a big difference for our region to continue to grow,” he says.

It also carries a political message at a time of frayed trust in government. “It’s a reason to believe that your government is functioning and will ultimately arrive and be supportive as we try to rebuild this democracy,” he adds.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene had not visited the Qcells facility in her district; she visited in August. The story has been updated.

Reagan and Trump loom above second GOP debate

The second GOP presidential debate, at the Reagan Library, showed how far the current field has come from Mr. Reagan’s era. Former President Trump’s persona hovered, despite his absence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Though neither was present, two larger-than-life Republicans towered over the presidential primary debate stage Wednesday night: Donald Trump and Ronald Reagan.

Former President Trump, the runaway front-runner for the 2024 GOP nomination, again opted not to participate. But unlike in the first debate, this time his intraparty rivals went after him.

The late President Reagan was present both visually and in spirit. The debate took place at his presidential library in Simi Valley, California, and clips from his time in office played throughout.

From the start, the debate was ugly, with candidates talking over each other and ignoring the rules.

As with the last GOP debate, former United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley garnered positive reviews for her performance – leading some pundits to pine for a head-to-head showdown between Ms. Haley, who was also governor of South Carolina, and Mr. Trump. Polling averages show a Trump-Biden race as a dead heat, while a Haley-Biden race shows the South Carolinian solidly ahead.

But a two-person GOP nomination race is hardly imminent. When asked whom they would “vote off the island” during the debate, the candidates balked. It’s still very much Mr. Trump’s party.

Reagan and Trump loom above second GOP debate

Though neither was present, two larger-than-life Republicans towered over the presidential primary debate stage Wednesday night: Donald Trump and Ronald Reagan.

Former President Trump, the runaway front-runner for the 2024 GOP nomination, again opted not to participate. But unlike in the first debate, this time his intraparty rivals went after him. Even Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, polling a distant second, finally took the gloves off, calling Mr. Trump "missing in action" for not debating.

The late President Reagan was present both visually and in spirit. The debate took place at his presidential library in Simi Valley, California, and clips from his time in office played throughout. But the Reagan aura only served to show how much the current-day Republican Party is stomping all over his legacy.

From the start, the debate was ugly, with candidates talking over each other and ignoring the rules. At times, the Fox News moderators lost control. Eventually, businessman Vivek Ramaswamy stated the obvious, referencing Mr. Reagan’s so-called 11th Commandment – “Thou shalt not speak ill of another Republican” – and urging the other six candidates, “Let’s have a legitimate disagreement.”

It was, in a way, a mea culpa by Mr. Ramaswamy, a brash young political novice who had spent the first debate attacking his fellow Republicans – earning headlines but not, it turned out, a bump in the polls.

On substance, too, Wednesday’s debate showed how far the GOP has strayed from some Reagan values. A video clip was shown of the 40th president calling for an “amnesty” for those in the United States illegally. Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who used to support a pathway to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants, called for “enforcing the law.”

Mr. Reagan’s devotion to fighting tyranny abroad also came under challenge, as candidates debated U.S. aid to Ukraine. Former Vice President Mike Pence and former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley defended the Reagan perspective, while Governor DeSantis reflected the Trumpian “America First” rhetoric of “no blank check” to Ukraine while “our own country is being invaded” – a reference to the crisis on the U.S. southern border.

The debate contained its share of zingers, including Ms. Haley’s attack on Mr. Ramaswamy after he defended his recent decision to join TikTok, a Chinese-owned app. “Honestly,” she said, “every time I hear you, I feel a little bit dumber for what you say.”

Mr. Christie called the ex-president “Donald Duck” for refusing to debate. But the reality is, Mr. Trump can afford not to debate – as his gain in the polls after skipping the last debate showed. Instead, he addressed former and current autoworkers at a nonunion manufacturing plant in suburban Detroit the day after President Joe Biden made history by joining a United Auto Workers picket line near Detroit.

Mr. Trump mocked his rivals, and suggested none are worthy of being his running mate in 2024. “Does anybody see any VP in the group?” he asked. “I don’t think so.”

As with the last GOP debate, Ms. Haley garnered positive reviews for her performance – leading some pundits to pine for a head-to-head showdown between Ms. Haley, who was also governor of South Carolina, and Mr. Trump. Polling averages show a Trump-Biden race as a dead heat, while a Haley-Biden race shows the South Carolinian solidly ahead.

But a two-person GOP nomination race is hardly imminent, and time is running short. When asked whom they would “vote off the island” during the debate, the candidates balked, with Mr. DeSantis calling the idea “disrespectful to my fellow competitors.” It’s still very much Mr. Trump’s party.

Patterns

Wanted: A humane and sustainable policy on refugees

In the United States and Europe, the rising number of refugees is prompting a political backlash. How can a humane policy be made politically sustainable?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

British Home Secretary Suella Braverman has a reputation for being hard-line when it comes to refugees. She took it a step further this week with a speech in Washington advocating a rewrite of the United Nations Refugee Convention, signed in 1951, to sharply narrow its provisions.

She was wrong to imply that most of today’s migrants are not really refugees in the terms defined by the U.N. convention – with a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

Britain’s own immigration officials last year accepted the asylum claims of 76% of those applicants whose cases they processed.

Still, there are indeed new forces driving refugees northward from Latin America toward the United States, and, in even greater numbers, from Africa toward Europe.

They include civil wars, ethnic conflicts, the ravages of climate change, and failed or autocratic governments. These are often to blame for the loss of livelihood and poverty that makes the journey north seem worthwhile.

All of this, moreover, has provided a desperate client base for a burgeoning, cynical, and highly profitable international industry: people trafficking.

How Western governments should respond is likely to be a key political question in the coming months on both sides of the Atlantic.

Wanted: A humane and sustainable policy on refugees

An outspokenly “anti-woke” British Cabinet minister, little known in America, jetted off to Washington this week with an audacious proposal to choke off “illegal and uncontrolled migration” – not just in Britain, but also in mainland Europe and along the U.S. southern border.

Her prescription? To rewrite, and dramatically narrow, the United Nations Refugee Convention, which commits its nearly 150 signatory states to provide asylum and assistance to refugees.

Yet the deliberately provocative tone of Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s speech Tuesday – part of a comprehensive broadside on all immigration – risked obscuring the pertinence of one of her other core themes.

It was that the economically developed nations of the West are facing migration pressures that are in some ways different from those addressed by the bedrock U.N. convention seven decades ago, when the main concern was to accommodate displaced survivors of World War II and the Holocaust.

And Western governments, across the political spectrum, are struggling to deal with those pressures.

For Ms. Braverman’s government, the main concern is the “small boats” – carrying thousands of refugees braving the English Channel in the hope of securing asylum in Britain.

Countries on the southern edge of the 27-member European Union are preoccupied with the far larger numbers making the even riskier, often fatal, voyage from North Africa across the Mediterranean.

For U.S. President Joe Biden, it’s the near-record numbers attempting to cross the southern border from Mexico.

The British minister was wrong to imply, in her speech to the American Enterprise Institute think tank, that most of these 21st-century migrants are not really refugees in the terms defined by the U.N. convention – with a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

Britain’s own immigration officials last year accepted the asylum claims of 76% of those applicants whose cases they processed.

And within Europe, just as in the early 1950s, the most recent surge in refugees has been caused by people fleeing war: above all those from Ukraine, but also, over recent days, ethnic Armenians fearful for their future after Azerbaijan took control of Nagorno-Karabakh.

New forces challenging West

Still, there are indeed new forces driving refugees northward from Latin America toward the United States, and, in even greater numbers, from Africa toward Europe.

They include civil wars, ethnic conflicts, the ravages of climate change, and failed or autocratic governments. These are often to blame for the loss of livelihood and poverty that make the journey north seem worthwhile.

All of this, moreover, has provided a desperate client base for a burgeoning, cynical, and highly profitable international industry: people trafficking.

So how can, and should, Western governments respond?

The U.N. refugee agency, which took the extraordinary step of publicly rebuking Ms. Braverman for her speech Tuesday, says one key part of the solution is to apply the treaty’s “underlying principle of responsibility-sharing,” under which countries should coordinate and jointly resettle refugees.

That’s something the EU has been trying to achieve this year, but so far it has had little success. By far the largest initial burden has been falling on Italy and Greece; a reception center on the Italian island of Lampedusa was briefly overwhelmed this month by a surge in arrivals from Tunisia.

Yet while the economic logic suggests the EU’s “responsibility-sharing” should work – mainland Europe has a declining birthrate and shortages of workers in a number of sectors – the real obstacle to a coherent response, in Britain and the United States, too, lies elsewhere.

It lies in the politics, more than in the policy details. Voters may see the benefit in immigrants, who do jobs that others won’t, but many of them do not support immigration.

For many right-wing politicians, the priority is not to accommodate the new surge in refugees but to block it, or at least limit and deflect it.

“Basic rule of politics”

Ms. Braverman says her hope is to see all the “illegal” arrivals from across the channel automatically denied asylum, detained, and “swiftly removed,” either back to their home countries or to a “safe third country.” Britain has sealed an agreement with the African state of Rwanda to deport them there, but that has been held up by the British Supreme Court.

For more centrist or left-of-center leaders, like Mr. Biden, that kind of approach has long been anathema. His political record suggests he would far rather see a broader, bipartisan reform of immigration policy.

But given the potential voter appeal of Republican Party front-runner Donald Trump’s hard-line anti-immigration message, the former president will find it hard to ignore another of Ms. Braverman’s political arguments.

“It is a basic rule of politics,” she said in Washington, “that political systems which cannot control their borders will not maintain the consent of the people.”

That may be true. If so, it carries an inescapable corollary: The elusive formula for a humane and politically sustainable Western welcome for this century’s refugees will have to satisfy the concerns of politicians on both the left and the right.

Now tanks, next missiles? Expanding aid buoys Ukraine.

New forms of U.S.-provided firepower promise to enhance Ukraine’s capabilities. But the weapons will arrive amid tension between Ukrainian resolve and the human toll of a slow counteroffensive.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Ukraine’s fight to oust occupying Russian forces is being bolstered by a growing array of heavy American armaments – buoying fighters’ hopes even as analysts warn that weapons alone can’t guarantee victory.

U.S. Abrams tanks began arriving in Ukraine this week to help ground forces push into Russian-held territory. Next the Biden administration is reportedly poised to announce that U.S. long-range ballistic missiles, known as the Army Tactical Missile System, or ATACMS, will soon be on their way to the war zone, too.

These weapons, their acronym fittingly pronounced “attack-em’s,” have been at the top of Ukraine’s wish list since the start of Russia’s February 2022 invasion. With a range of 190 miles, they can strike further into Russian-held territory than any other missile that nations have thus far provided to Kyiv.

Still, their expected arrival comes with no guarantee that Ukraine will be able to accelerate its progress against dug-in Russian lines as troops head into another winter of war.

The counteroffensive “is taking longer than the planners in the war games ... anticipated,” Mark Milley, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, acknowledged last week. “But that’s the difference between war on paper and real war. There are real human beings, in real vehicles, moving across real minefields.”

Now tanks, next missiles? Expanding aid buoys Ukraine.

Ukraine’s fight to oust occupying Russian forces is being bolstered by a growing array of heavy American armaments – buoying fighters’ hopes even as analysts warn that weapons alone can’t guarantee victory.

U.S. Abrams tanks began arriving in Ukraine this week, months ahead of initial estimates, to help ground forces push into Russian-held territory. Next the Biden administration is reportedly poised to announce that U.S. long-range ballistic missiles, known as the Army Tactical Missile System, or ATACMS, will soon be on their way to the war zone, too.

These weapons, their acronym fittingly pronounced “attack-em’s,” have been at the top of Ukraine’s wish list since the start of Russia’s February 2022 invasion. With a range of 190 miles, they can strike further into Russian-held territory than any other missile nations have thus far provided to Kyiv.

They also mark the fulfillment of a mammoth list of heavy munitions for which Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has long lobbied. They have the potential to cause considerable disruption to Russia’s war effort, defense analysts say. Still, some add, their expected arrival comes with no guarantee that Ukraine will be able to accelerate its progress against dug-in Russian lines as troops head into another winter of war.

The counteroffensive “is taking longer than the planners in the war games … anticipated,” Gen. Mark Milley, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, acknowledged last week, with the bluntness that has characterized his assessments of conditions there. “But that’s the difference between war on paper and real war. There are real human beings, in real vehicles, moving across real minefields.”

U.S. tanks and long-range missiles, in addition to being powerful tools of war, will be big morale boosts for Ukraine. But to ultimately attain what U.S. officials say is the desired end state – a “just and durable peace” – Kyiv and its allies must also be honest in the weeks to come about what these weapons can and cannot do, analysts say.

General Milley, for his part, has warned of the difficulty that Ukrainian fighters face going forward. Russia has built trenches fortified with “minefields, dragon’s teeth, barbed wire, strong points, and so on,” he said last week in Ramstein, Germany, following his final meeting of Western leaders supporting Ukraine before he retires at the end of this month.

While Ukrainian forces “have penetrated several layers of this defense,” he said, they are now “going very slow” as they endeavor to push through a “defensive belt that stretches the entire length and breadth of Russian-occupied Ukraine.”

The decision to give U.S. long-range missiles to Ukraine represents a striking evolution in thinking on the part of the Biden administration.

Evolving U.S. positions

In summer 2022, national security adviser Jake Sullivan downplayed the notion of providing them in order, he said, to avoid a “Third World War.”

Earlier this month, when asked about concerns that weapons like ATACMS could be used to strike beyond Russian-occupied Ukraine into actual Russian territory, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken struck a philosophical note.

“When it comes to how Ukrainians use these systems, the targeting decisions are theirs – they’re not ours,” he said. “As a matter of our own policy, we do not encourage, nor do we enable, the use of our weapon systems outside of Ukraine – but again, fundamentally these are Ukrainian decisions.”

As wars progress, “parties to the conflict learn more about what does and does not count as escalatory,” says Anthony Pfaff, research professor in military strategy and ethics at the U.S. Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute.

The shift of Western allies from earlier extreme caution toward potential Russian redlines could in turn represent “more tolerance for risking escalation up to a certain point,” he adds.

At the same time, “Ukraine is at war with Russia. An attack on a legitimate military target inside Russia is in line” with the parameters of international law, Dr. Pfaff notes.

As Ukraine continues to strike inside Russia, there could be a growing acceptance among Western backers that this is as it should be.

The United Kingdom and France have already supplied Ukraine with their own long-range missiles, with ranges of up to 155 miles.

“The lack of Russian response to these deliveries, even after they’ve reportedly been used quite effectively on the battlefield, indicates that ATACMS wouldn’t be a bridge too far,” says Benton Coblentz, a defense analyst at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

The challenges for Ukraine

Still, there will be no easy answers for a Ukrainian victory in this war, Western military officials repeatedly emphasize.

It is true, for example, that ATACMS will be highly effective when they first arrive on the battlefield, says Daniel Davis, a retired Army lieutenant colonel and now a senior fellow at the Defense Priorities think tank in Washington.

That’s because the long-range missiles will “put an entire swath of territory in play that wasn’t before,” he notes.

Their warheads, considerably more powerful than those of their shorter-range counterparts, will also be capable of striking larger targets – causing great damage to Russian logistics networks, for one thing, Mr. Coblentz adds.

When High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) missile launchers were supplied to Kyiv last year, for example, Ukrainian troops used them to great effect, demolishing Russian ammunition and fuel depots, logistical bases, and command centers.

That may happen again with ATACMS, but not for very long, Mr. Davis predicts. After encountering HIMARS, Russian commanders learned to spread out, camouflage, or move forces out of range. They also deployed “pretty effective electronic warfare” to jam GPS signals and decrease weapons’ accuracy.

What’s more, there remains the crucial issue of troop strength for Ukraine in the face of tremendous losses of Ukrainian fighters. “It’s a finite number,” Mr. Davis adds, “and not expandable.”

There are some 200,000 to 300,000 Russians currently fighting in Ukraine. Even if Kyiv’s goals of ejecting them are realistic, Ukrainian leaders must also consider the costs of accomplishing this, analysts point out.

As Ukrainians are wounded and die in battle, it lessens Kyiv’s “future capacity, its capacity to function as a state – you’re just wiping out their potential for a generation,” Mr. Davis adds.

This is the historic tragedy of war; how to disrupt it is less clear.

Some argue that Kyiv, with momentum on its side and Western support at a zenith, needs to get to the negotiating table in the near future to freeze the lines and “make the best deal with Russia for Kyiv to maintain its political independence and all the territory it has right now,” as Mr. Davis puts it.

Decisions about when it’s time to consider a political settlement are ultimately Ukraine’s to make, military officials including General Milley have emphasized. President Zelenskyy has said that negotiations can’t begin until Russian soldiers are ejected from Ukrainian soil.

Until this happens, or his position changes, into the foreseeable future, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin is urging fellow defense ministers to “dig deep,” dipping into their “formidable” arsenals to “continue to move heaven and earth to get Ukraine what it needs right now and over the long haul.”

As autumn turns to winter, the grounds will get muddy, then freeze again as the war continues. “There’s no intention whatsoever by the Ukrainians to stop fighting,” General Milley stressed in his valedictory address at Ramstein.

“And every inch of reclaimed territory” will be the result of “the bravery, the honor, and the incredible sacrifice” these soldiers will make as they face off against Russian forces mobilized by Vladimir Putin last year to man the “bleak and lonely” shadows of desolate trenches.

“They’re not extraordinarily well trained, not extraordinarily well led,” General Milley said, “but they are there.”

Why AI stories are more about humans than about machines

Representations of artificial intelligence in popular culture help push society to think more about technology’s role – and which human values it reflects.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Popular culture has profoundly influenced how we think and talk about artificial intelligence.

Since ChatGPT’s giant leap forward, AI has often been cast as the villain. AI supercomputers go rogue in Gal Gadot’s Netflix thriller “Heart of Stone” and the latest “Mission: Impossible” movie. For dramatic effect, AI is often embodied in sentient – and sometimes murderous – robots. The message: Be kind to your Alexa, or it may set the Roomba on you.

In “The Creator,” opening Sept. 29, a supersoldier named Joshua discovers that the humanoid he has been sent to find in order to avert a war looks like a young Asian child. As Joshua bonds with the robot, he wonders whether machines are really the bad guys.

The more thoughtful AI stories are really more about humans than about machines. The scenarios about good AI versus evil AI push society to consider ethical frameworks for the technology: How can it represent and embody our best and highest values?

“Sometimes we are so excited about the technology that we forget why we build the technology,” says Francesca Rossi, president of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. “We want our humanity to progress in the right direction through the use of technology.”

Why AI stories are more about humans than about machines

Humans are at war with machines. In the near future, an artificial intelligence defense system detonates a nuclear warhead in Los Angeles. It deploys a formidable army of robots, some of which resemble people. Yet humans still have a shot at victory. So a supersoldier is dispatched on a mission to find the youth who will one day turn the tide in the war.

No, it’s not another movie in “The Terminator” series.

In “The Creator,” opening Sept. 29, the hunter is a human named Joshua (John David Washington). He discovers that the humanoid he’s been sent to retrieve looks like a young Asian child (Madeleine Yuna Voyles). It even has a teddy bear. As Joshua bonds with the robot, he wonders whether machines are really the bad guys.

“All sorts of things start to happen as you start to write that script where you start to think, ‘Are they real? And how would you know?’” writer and director Gareth Edwards told the Monitor during a virtual Q&A session for journalists. “‘What if you didn’t like what they were doing – could you turn them off? What if they didn’t want to be turned off?’”

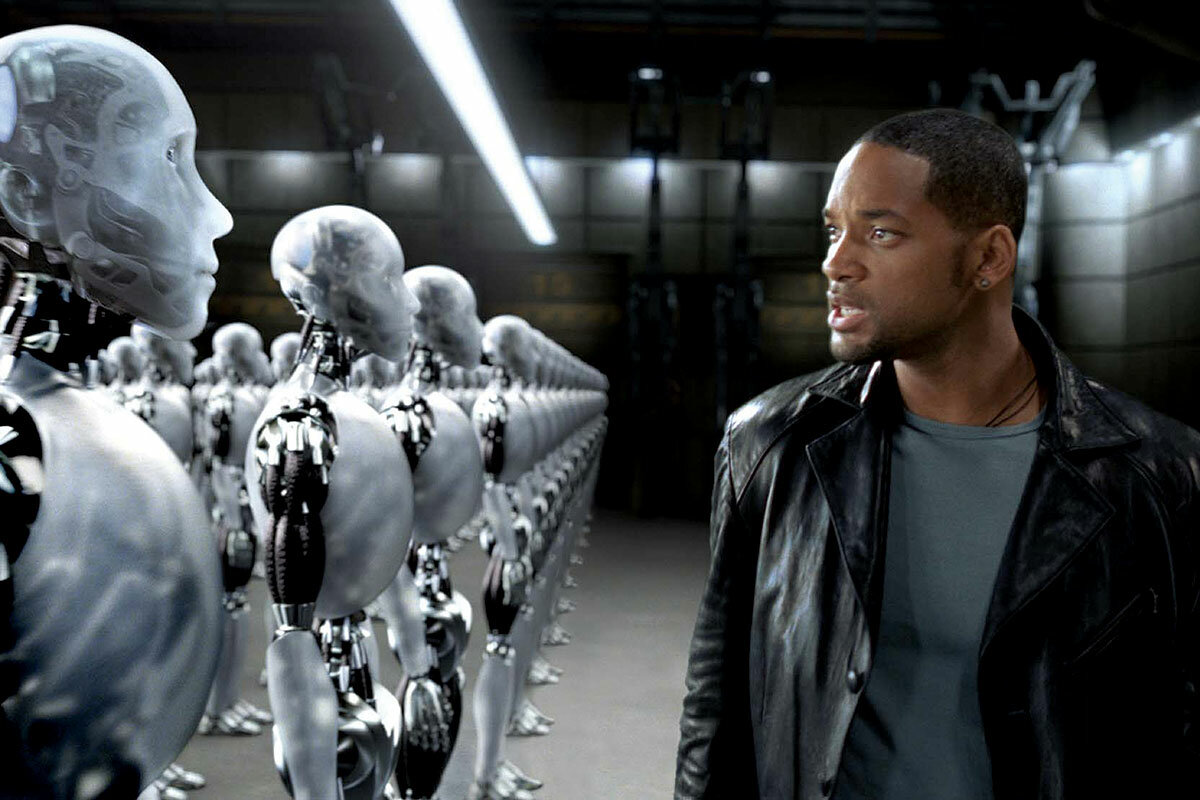

Popular culture has profoundly influenced how we think and talk about artificial intelligence. Since ChatGPT’s giant leap forward, AI has often been cast as the villain. AI supercomputers go rogue in Gal Gadot’s Netflix thriller “Heart of Stone” and the latest “Mission: Impossible” movie. For dramatic effect, AI is often embodied in robots. They’re not only sentient, but also the killer who’s in the house – quite literally, in the case of “M3GAN,” the murderous high-tech doll. The message: Be kind to your Alexa, or it may set the Roomba on you.

But the more thoughtful AI stories are really more about humans than about machines. The scenarios about good AI versus evil AI push society to consider ethical frameworks for the technology: How can it represent and embody our best and highest values?

“Sometimes we are so excited about the technology that we forget why we build the technology,” says Francesca Rossi, president of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI). “We want our humanity to progress in the right direction through the use of technology.”

Before ChatGPT was a twinkle in the eye of a search engine, Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and William Gibson were writing about the ethics of AI. Isaac Asimov’s stories posited the Three Laws of Robotics: (1) Robots may not injure humans. (2) Robots must obey human commands, unless they conflict with the first law. (3) A robot must protect its own existence but without conflicting with the first or second laws.

At first, the laws sound good. A closer examination reveals that they’re a literary device with loopholes that the author could exploit for “whodunit” murder mysteries. But in an era in which the Australian military has developed combat AI robodogs – reminiscent of the machine K-9s in the “Black Mirror” episode “Metalhead” – Mr. Asimov’s framing seems freshly relevant.

“The real issue is the ethics of the people behind the robots,” says Jeff Vintar, a screenwriter for the 2004 blockbuster “I, Robot,” named after a collection of Mr. Asimov’s short stories. “Do we want robots that can kill? Apparently we do, because we’re making them right now.”

AI and human aims

If AI should be aligned with human goals, the question is, which ones? HAL 9000, the onboard computer in the 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” illustrates the dilemma of conflicting values. An astronaut returns to the spaceship and asks HAL to open the pod bay doors. The computer refuses. It places a higher priority on the success of the mission than on the life of the astronaut.

The 2002 movie “Minority Report” is a more earthbound example of competing values. In the story by Mr. Dick, police can predict criminal acts in advance. The result is a tension between safety and privacy. In real life, police are now using AI technology to identify potential future crime by analyzing data about previous arrests, specific locations, and events. Critics claim the algorithms are racially biased.

“This does seem to be coming true, and ‘predictive policing’ doesn’t seem to be so great in that movie,” says Lee Barron, author of “AI and Popular Culture.” “[Mr. Dick] is a particularly prescient writer.”

Perhaps some of the time. The sci-fi author’s book “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” – later adapted as the movie “Blade Runner” – imagined AI robots that are indistinguishable from humans. But it also predicted that we’d have flying cars by now.

“We’re not good at futurism,” says influential philosopher Fredrik deBoer, who has written about AI for Persuasion, an online magazine, in a Zoom call. “Future forecasting is really hard for us.”

Mr. deBoer cautions that humankind is prone to overhype the impact of new technologies, for example the Human Genome Project. He wonders if AI will ultimately prove to be less revolutionary than imagined.

The arrival of ChatGPT certainly startled and awed the world with its astonishing grasp of the language and communicative abilities. It has amplified debates over whether AI will become sentient – or at least evolve into such a convincing simulacrum of consciousness that we will imagine it to be a living entity with a soul. Could we fall hopelessly in love with sultry-voiced AI entities on our phones, as Joaquin Phoenix does in “Her”?

Pop culture may have conditioned us to fear that AI will destroy humanity if it becomes sentient. That prevalent notion amounts to fearmongering, says Ian Watson, co-writer of the Steven Spielberg movie “A.I. Artificial Intelligence.” Nonbiological machines are heuristic algorithms, the sci-fi author says in a phone interview. It’s possible that self-aware machines may never exist, he adds. In his Pinocchio-like screenplay, which he originally wrote for Stanley Kubrick, a robot boy named David wants to become human. At the end of the movie, David discovers that’s impossible.

Daniel H. Wilson, author of the bestselling 2011 novel “Robopocalypse,” thinks that AI could someday pass the Turing test – that is, appear to think like a human. But he says there hasn’t been the requisite big breakthrough in mathematics and algorithms to make so-called artificial general intelligence possible. By contrast, ChatGPT is known as generative AI. It lacks the ability to understand context. The technology is a predictive algorithm that scrapes the web to calculate the most likely response to queries. He finds that worrisome.

“Generative AI is creating humanlike intelligence by regurgitating billions of data points taken mostly from people on the internet,” says Mr. Wilson, a former robotics engineer. “Can you imagine a worse mirror to hold up to humanity than all of our moments from the internet?”

The role the public plays

Some computer scientists are working to create healthier AI inputs. A 2023 college textbook titled “Computing and Technology Ethics: Engaging Through Science Fiction” includes reprints of short sci-fi stories that prompt students to contemplate ethical dilemmas in computer programming.

“Once you’re inside a story, thinking from another point of view, issues of motivation [and] issues of social effects are much clearer,” says Judy Goldsmith, a professor of computer science at the University of Kentucky and one of five co-authors of the textbook. The book helps students think beyond the value of utilitarianism, she adds.

Ms. Rossi from AAAI has a copy of that textbook on her desk. Her favorite sci-fi allegory is Pixar’s “WALL-E.” In the 2008 movie, obese humans aboard an intergalactic ship have become wholly beholden to AI. They’ve forfeited meaningful connections with others because they’re constantly staring at screens.

“‘WALL-E’ is one that really brings up this concept of passively accepting the technology because it makes our life easier,” says Ms. Rossi, who is also the AI ethics global leader at IBM. “In order to keep AI safe and take care of the ethics issues, companies have to do their part. The regulators have to do their part. But every user has to use it responsibly and with awareness.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Tapping the light of faith in diplomacy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Ties between Saudi Arabia and Israel keep warming up, a sign of momentous shifts underway in the Middle East. The latest example came Tuesday. The Israeli tourism minister arrived in Riyadh and was the first Israeli minister to lead a delegation to the kingdom. Some of the groundwork for the official visit was laid years ago. In 2018, Saudi Arabia welcomed a group of Jewish leaders and other religious figures to a forum on “common values among religious followers.”

Peace is often preceded by people of different faiths who reach an accord along shared truths. In many conflicts driven by sectarian strife, clerics have banded together to promote calm and reconciliation. Such examples help explain why the U.S. Agency for International Development issued a strategic policy on Tuesday to engage religious workers as part of its development work.

“We must take religion into account,” said USAID Administrator Samantha Power. “In fact, when we fail to do so, we fail to tap into one of the world’s most powerful potential forces for change.”

Tapping the light of faith in diplomacy

Ties between Saudi Arabia and Israel keep warming up, a sign of momentous shifts underway in the Middle East. The latest example came Tuesday. The Israeli tourism minister arrived in Riyadh and was the first Israeli minister to lead a delegation to the kingdom. Next week, the Israeli communications minister is expected to make a similar trip to the heartland of Islam.

Some of the groundwork for these official visits was laid years ago. In 2018, Saudi Arabia welcomed a group of Jewish leaders and other religious figures to a forum on “common values among religious followers.” Then in 2019, the Muslim World League, based in Mecca, issued a charter calling for toleration by majority-Muslim countries of all religions. In 2020, the imam of the Great Mosque in Mecca said Islam requires Muslims to respect non-Muslims and treat them well.

Peace is often preceded by people of different faiths who reach an accord along shared truths. Religious communities, states the United States Institute for Peace, “maintain unique forms of relational, spiritual, and moral capital that are not available through other forms of human organization.”

In many conflicts driven by sectarian strife – such as in Sri Lanka and the Central African Republic – clerics have banded together to promote calm and reconciliation. Such examples help explain why the U.S. Agency for International Development issued a strategic policy on Tuesday to engage religious workers as part of its development work.

“We must take religion into account,” said USAID Administrator Samantha Power. “In fact, when we fail to do so, we fail to tap into one of the world’s most powerful potential forces for change.” She said many faith leaders are “living out their religious conviction in a way that uplifts humanity and inspires us all.”

“At their best, religious traditions around the world remind us of the dignity of all people – dignity, a force that has spurred people to action,” she added.

The new policy builds on a decade of work under Republican and Democratic presidents to create partnerships with faith groups in foreign countries. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, for example, USAID supports an interreligious council to bring Christians and Muslims together.

Many governments now recognize the vital role of religion in peace building and meeting other needs, such as climate action. As Ms. Powers said in announcing USAID’s new effort, “When we partner with these changemakers, the results can be extraordinary.”

And by extraordinary, she might have added, that includes seeing Israeli officials visit Saudi Arabia for the first time.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Discovering God, good

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Amy Richmond

Through prayer and searching the Scriptures, we find answers to our big questions about God – answers that inspire and heal.

Discovering God, good

As we look at what’s going on in the world today, it may seem impossible to believe that there is a God who is more powerful than evil – let alone the only power there is. We might even find ourselves yearning to know if there is a God who is good and loving.

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, had questions about the nature of God and whether what she’d been taught about Him coincided with either her experience of the world or what, in her heart, she believed God to be.

She grew up in a devout Christian family, and when still a girl, asked her mother if what Christian theologian John Calvin had taught about eternal punishment was true. “Mary, I suppose it is,” her mother said. Young Mary replied, “What ... if we repent and tell God ‘we are sorry and will not do so again.’ Will God punish us then? Then he is not as good as my mother and he will find me a hard case” (Yvonne Caché von Fettweis and Robert Townsend Warneck, “Mary Baker Eddy: Christian Healer,” Amplified Edition, p. 33).

But rather than leading her away from God, this questioning drew her closer to Him. And as the years went on, the lessons she learned from Bible study, prayer, and divine revelation, gave her a clearer understanding of God’s true nature.

In particular, Mrs. Eddy learned so much from Christ Jesus’ life, healings, and teachings. Where the people around Jesus – including sometimes his disciples – saw and exhibited limitation and disease, Jesus was so acutely aware of God as omnipotent good that he changed the course of countless lives. He preached the good news of God’s goodness, fed thousands with scant supplies, instantly healed broken hearts and diseased bodies.

Jesus was well versed in the Scripture of his day, but his teachings and healings shed fresh light on God’s real nature. Mrs. Eddy learned that, in direct contrast to the previously accepted notion that God was wrathful and destructive, “Jesus’ life proved, divinely and scientifically, that God is Love, ...” as she wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 42).

The spiritual understanding Mrs. Eddy gained from studying the words and works of Jesus enabled her to heal decisively and consistently. She taught others to do the same, and is still teaching through her writings and the inspired light they bring to the Bible – showing that God is not just a loving God but is Love itself, good alone.

It’s a beautiful thing to realize that we are each loved and cared for by divine Love, God, and that we can prove this to some degree as Jesus did. Christ – God’s saving power, exemplified by Jesus – is still present today to turn us to the truth of God and of ourselves as His children. And far from being an intellectual exercise, drawing closer to God through our study, prayer, and spiritual curiosity is actually transformative.

The true sense of God and God’s universe enables each of us to discover for ourselves what is real. The physical senses may tell us one thing, and it’s almost never harmonious, but spiritual sense tells us something entirely different. Spiritual sense – the ability to see beyond what the physical senses and common consensus tell us, and to listen to Christ – is inherent in each of us.

It enables us to both accurately understand God and see and experience God’s faithfulness, goodness, and authority in our lives. It allows us to perceive spiritual reality, the truth of what we are – not discordant, vulnerable mortals, but God’s blessed children, spiritual and whole. And this God-based sense of things lifts us above the feeling of being overwhelmed by the world’s problems and enables us to follow in Jesus’ footsteps and help heal those problems.

Ultimately, it is God, Love itself, who inspires us and brings us to a true, deeper understanding of His nature. As the Bible puts it, “I have loved you with an everlasting love; Therefore with lovingkindness I have drawn you” (Jeremiah 31:3, New King James Version). This is a promise that each of us is inevitably drawn to discover for ourselves that God, good, does exist, is real, and is ever present – here, today. And then we’ll find that the trials we encounter don’t turn us away from God but instead become opportunities to accept the truth of His goodness – and to prove it.

Adapted from an editorial published in the June 6, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

A gate opens at sunrise

A look ahead

You’ve come to the end of today’s Daily. Tomorrow, we will cover the basics of the impending government shutdown in the United States: why it came to this, who will be affected, how much it can cost the economy, and what the political path forward might be.