- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Dianne Feinstein, a pioneering woman in politics

Dianne Feinstein, California’s senior senator, who died Friday, is being remembered for her three decades as a pioneering woman in the United States Senate – and before that, as San Francisco’s first female mayor.

Senator Feinstein was a prominent advocate for gun safety and civil rights, and a centrist Democrat who rose to become chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee and a key member of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Most recently, as the oldest member of Congress, she experienced cognitive struggles that led to calls for her resignation. In today’s Monitor Daily, our “Why We Wrote This” podcast examines the larger issue of age and politicians. But on Friday, Ms. Feinstein was remembered fondly from both sides of the aisle.

“Dianne made her mark on everything from national security to the environment to protecting civil liberties,” said President Joe Biden, a friend from their Senate days together, in a statement. “She’s made history in so many ways, and our country will benefit from her legacy for generations.”

“She was an incredibly effective person at every level on the way to the Senate,” Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell said in a statement. “Her name became synonymous with advocacy for women, and with issues from water infrastructure to counter-drug efforts.”

Perhaps Ms. Feinstein’s most iconic moment of leadership came in 1978, when San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and city supervisor Harvey Milk were assassinated at City Hall. Ms. Feinstein, as president of the Board of Supervisors, became acting mayor and led the city through a dark period, before winning the office in her own right.

She was first elected to the Senate in 1992 – the “Year of the Woman.” Now, California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, faces the task of naming a replacement to fill the rest of Ms. Feinstein’s term. He had earlier pledged to name a Black woman. But whomever he selects, the Feinstein legacy will surely serve as a guidepost.

[Editor’s note: This article was updated to correct the date of Ms. Feinstein's death.]

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Freedom Caucus: The Fight Club of Congress

The group designed to be a thorn in the side of GOP leadership has become too fragmented to agree on specific demands, reducing its influence as a bloc. But key individuals have more leverage than ever.

If the federal government shuts down at midnight Saturday, nearly everyone on Capitol Hill is ready to blame the House Freedom Caucus.

Yet hardly anyone here can articulate what, exactly, the right-wing group wants – or how it plans to get there.

The group has no website, no official roster, and definitely no cameras in the room where it happens.

You can only join if you’re “vetted and invited.” It’s all part of the mystique surrounding the ultraconservative group that often seems like Capitol Hill’s version of Fight Club. (First rule of Fight Club: You don’t talk about Fight Club.)

Founded to rein in spending and decentralize power in the House, it has long been a thorn in the side of GOP leaders. It has shut down government operations and careers before – and has made clear it isn’t afraid to do so again.

Today, the bloc’s members have more clout than ever, even as members are divided over tactics.

But some say it has departed from its founding ideals.

“It’s like, ‘Guys, you used to have actually a fiscal heart and soul, and now you’re just playing political games,’” says Freedom Caucus co-founder Matt Salmon, who left Congress in 2017.

Freedom Caucus: The Fight Club of Congress

If the federal government shuts down at midnight Saturday, nearly everyone on Capitol Hill is ready to blame the House Freedom Caucus.

Yet hardly anyone here can articulate what, exactly, the right-wing group wants – or how it plans to get there.

There isn’t even complete clarity on who’s in it. The group has no website, no official roster, and definitely no cameras in the room where it happens.

Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz, a key player in the shutdown drama, often appears with the Freedom Caucus. But he says he’s technically just an “admirer.” Georgia firebrand Marjorie Taylor Greene was a member, and now isn’t, under circumstances that remain unclear.

You can only join if you’re “vetted and invited,” says Arizona Rep. Andy Biggs, strolling back from the House last week after casting one of six GOP votes that blocked leadership from bringing the defense appropriations bill to a vote.

“Andy Biggs, my hero!” says Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, a fellow Freedom Caucus member, sidling up to him at the edge of the crosswalk leading back to House office buildings.

“Hey, what’s up,” he says, before turning back and declining to elaborate further on the caucus’s “internal workings.”

It’s all part of the mystique surrounding the ultraconservative group that often seems like Capitol Hill’s version of Fight Club. (First rule of Fight Club: You don’t talk about Fight Club.) Founded to rein in spending and decentralize power in the House, it has been a thorn in the side of GOP speakers from John Boehner to Paul Ryan and now Kevin McCarthy. It has shut down government operations and careers before – and has made clear it isn’t afraid to do so again.

Yet while Freedom Caucus members have more clout than ever, including key seats on committees and subcommittees, this latest standoff has also exposed cracks within the group itself. Members have been publicly divided over tactics, the desirability of a shutdown, and whether to accept a short-term fix.

One reason for the chaos is simple math. Republicans hold only a four-seat majority, which means that just a handful of lawmakers can gum up the works. That gives any holdouts outsize leverage, which disincentivizes banding together or compromising. As the government edges closer to the brink of running out of money, Speaker McCarthy isn’t negotiating just with the Freedom Caucus, but with a rotating cast of individuals, both inside and outside the group – all with seemingly disparate demands.

“Didn’t we sing kumbaya the other night?” jokes Rep. Ken Buck of Colorado, a Freedom Caucus member, when asked about the group’s internal divisions. Mr. Buck himself has publicly criticized Mr. McCarthy’s decision to launch an impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden, calling it a transparent attempt by the speaker to distract from the spending fight.

“We all held hands,” quips Representative Biggs, walking alongside him.

“It’s a big group. And it’s a group that’s going to disagree,” says Mr. Buck, more seriously. “People look at that and say, ‘That’s disorganized.’ I look at that and I say, ‘I’m learning a lot.’”

What, specifically, has he been learning?

“There’s a lot of conservatives that will vote for more spending.”

Conservatives were “getting rolled”

The Freedom Caucus was born during a secret January 2015 meeting of nine GOP members of Congress in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

During the Obama years, Republicans had retaken the House with the tea party wave of 2010, but many were frustrated that they hadn’t made much progress in exacting fiscal discipline. A 16-day shutdown in late 2013 over the president’s Affordable Care Act failed to extract any changes to the health care policy, and the GOP saw its approval numbers plunge.

Conservatives felt like they were “constantly getting rolled,” says Matt Salmon, a veteran representative from Arizona who was recruited to join the Hershey meeting. He and his co-founders saw a need for a new group that could harness the collective clout of right-wing members. Their goal: pressure Republican leaders to restore “fiscal sanity” and constitutional principles, and allow legislators to actually legislate – instead of making big spending decisions behind closed doors.

Many today insist the group’s mission remains unchanged. Freedom Caucus leaders say they are trying to draw a line in the sand, to get a bankrupt and broken Washington back on track before it’s too late.

“Our members are united on one thing, and that is to make sure that we cut spending in this government and that we fund things that the government should be doing – no more and no less,” says Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida.

Mr. Salmon, however, is dismayed over the group’s current state. He says the caucus abandoned its core principles to become a “cheering squad” for President Donald Trump, staying mum as the Trump administration ran up big deficits. (What members say in their defense: They weren’t in Congress yet, or the economy was much better then.) That, he says, created a credibility deficit that has undermined its power.

“Where were you during those four years when we were spending like drunken sailors on shore leave?” asks Mr. Salmon, who left Congress just before Mr. Trump took office in January 2017. “It’s like, ‘Guys, you used to have actually a fiscal heart and soul, and now you’re just playing political games.’”

Others on the right are less critical but agree the caucus is struggling to exert the influence it once had.

A more unified Freedom Caucus would actually be helpful in the current situation, argues Rep. Thomas Massie, a Kentucky libertarian who is not in the group but is a fiscal conservative. “If they were functioning as they were founded, where they consolidate ideas and plans among the most conservative portion of the party,” they could win some meaningful concessions, he says.

“The problem we have right now is that the Freedom Caucus is not leading” the dissent, Mr. Massie adds. “A lot of times when you find five or 10 dissenters, there’s no common objection. So it’s hard to get past that impasse.”

Fighting for the sake of fighting?

“Anybody seen a bald guy with a goatee?” asks someone in the bowels of the Capitol where journalists are milling around to get the latest scuttlebutt after a GOP meeting breaks up.

It’s a tongue-in-cheek reference to Rep. Chip Roy, an ideological heavyweight within the Freedom Caucus and one of the most prominent members pushing Speaker McCarthy to hold the line on government spending.

Mr. Roy knows all about government shutdowns, and the political risks they carry: He was serving as chief of staff for GOP Sen. Ted Cruz when the senator championed the 2013 shutdown over the Affordable Care Act. He doesn’t want another one now, and he’s chastised some of his more hard-line colleagues for flirting with danger.

But he’s also insistent that Congress needs to rein in “out of control” spending.

“The federal government will spend $2 trillion more than it takes in this year,” Representative Roy said at a Freedom Caucus press conference earlier this month, noting that the government had already added $1.5 trillion in debt since the “so-called debt deal” in June. “We’re now spending more on interest on the debt than we are on defending the United States of America.”

“Thank God for the Freedom Caucus,” chimed in Florida Sen. Rick Scott at the same presser. “We’ve gotta stop this insanity.”

Still unclear is how they plan to do that.

With Democrats currently in control of the Senate, and President Biden in the White House, nothing can pass without bipartisan support, which means, in the end, that some form of compromise will be required. The question for conservatives is how much pain they want to try to inflict in advance of that eventual compromise – and whether those efforts will actually help or hurt their cause.

Many are still irate over the debt ceiling deal Mr. McCarthy brokered with the president back in June. Others concede that the speaker’s hands were essentially tied. Some critics question whether the current holdouts can be placated by any concessions, or simply want to fight for the sake of fighting.

Rep. Ralph Norman of South Carolina, who withheld his vote for Mr. McCarthy to become speaker until the 11th of 15 rounds, says he’s fine with being one of only a handful of GOP members standing apart from the rest of the Freedom Caucus if that’s what it takes to achieve “economic security.”

“We’re going to fight for the country,” says Representative Norman. “I don’t care whether we’ve got four [members], or we’ve got more.”

Hanging over the negotiations is the threat that at any moment, a single disgruntled member could bring a “motion to vacate” the speaker’s chair – in other words, a vote on whether to kick Mr. McCarthy out of his job.

In a Sept. 12 phone call with reporters, Mr. Gaetz accused Mr. McCarthy of backtracking on promises he made to conservatives when trying to win the speakership – and threatened to bring such a motion “every single day” for as long as it takes.

Democrats have been watching this drama unfold with a mixture of frustration, schadenfreude, and even a touch of sympathy.

“We’ve all had friends in relationships where we say to them, ‘They’re not good for you, and they’re not that into you,’” says Democratic Rep. Derek Kilmer of Washington. “And this feels like that dynamic.”

The majority party has always had to deal with disgruntled factions, notes former House historian Ray Smock. But it’s unusual for a handful of people to wield such outsize power. Previous Speaker Nancy Pelosi managed to largely maintain discipline in the last Congress with an 11-seat Democratic majority.

“The fact that the leadership on the Republican side has not found a way to deal with their own hotheads, as I’m prone to call them, is kind of a mystery,” says Mr. Smock. “At some point they will have to be called to account.”

A temporary fix falls short

Over the past week, Mr. McCarthy began bending to some of the renegades’ demands. Mr. Gaetz and others have been insisting on 12 separate spending bills rather than one big “omnibus,” which has become the default for Congress and makes it difficult to influence funding levels in specific areas.

Earlier in the summer, however, some of those same members stalled that 12-bill process by bringing the House floor to a complete standstill in retaliation for Speaker McCarthy’s compromise on the debt ceiling. Conservatives said Mr. McCarthy had reneged on promises he made in January to win their backing for the speakership.

“What we ended up doing was sort of re-litigating January ... in July,” says Representative Massie. “It was sort of like, ‘OK, Kevin, you didn’t hold your end of the bargain, so we’re going to stop you from doing anything.’”

The speaker held votes Thursday on four of those 12 bills, and got three of them passed in addition to one that passed this summer. But he got little in return. On Friday, 21 Republicans torpedoed a GOP stopgap spending measure – known as a “continuing resolution,” or CR – that would have kept the government running in the short term.

The measure, which Representatives Roy and Donalds, along with Freedom Caucus chair Scott Perry, hashed out with other Republicans, provides for lower overall spending levels and provisions to improve border security. But more than 10 of their own Freedom Caucus colleagues, including Mr. Biggs, Mr. Buck, and Ms. Boebert, helped kill it.

Rep. Garrett Graves, who was the chief negotiator between the caucus and Mr. McCarthy during the debt ceiling standoff, said last week that walking away from the CR was a “big mistake.” The measure wouldn’t have passed the Senate as written, but it would have given Mr. McCarthy some leverage in his negotiations with Democrats. Now, they may be heading for a politically damaging shutdown that eventually forces Republicans to cave entirely.

“I think the closer we get to shutdown, the more and more leverage you lose,” he said.

When asked whether the stalemate reflects a breakdown in ideological cohesion, personalities, or just general dysfunction, he gave a tired smile.

“I’ve got a whole lot of reasons as to why that’s happening,” he said. Tapping his head, he added, “But I’m just going to keep them right there for right now.”

Government shutdown: How did we get here?

The start of a new fiscal year is a time to hash out budget priorities. But those seeking to exert maximum leverage sometimes undermine the whole process – including their own goals.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

Like a stone thrown into water, a government shutdown initiated in Washington will ripple out across America. Unless Congress can agree to an 11th-hour stopgap funding measure, the government will run out of money at 12:01 a.m. on Sunday, affecting millions of government employees and the citizens their departments serve.

Air travel, national parks, and some food assistance programs are among the things that would be affected. But not every government activity will stop. Social Security checks, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs benefits will still be distributed, for example.

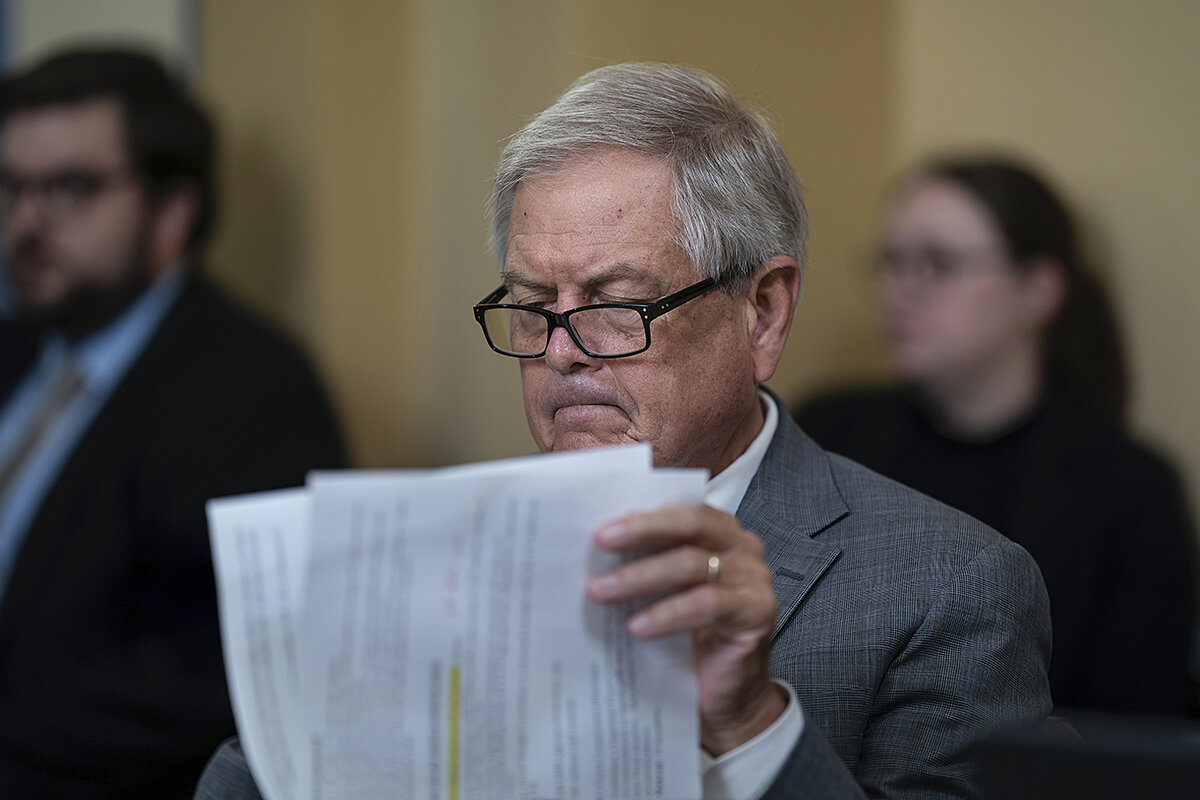

It didn’t have to be this way. Everyone knew the government would run out of money on Sept. 30. But in recent years, “Congress has gotten used to not getting its business done on time,” says Oklahoma Republican Tom Cole of Oklahoma, facing his fourth shutdown as a congressman.

While there’s plenty of partisan blame, the underlying fact is that Washington’s budget process is broken. Shutdowns have become showdowns, a last-ditch effort to underscore party objectives and spending priorities. But they rarely achieve their political objectives, instead gumming up the works, hurting citizens, and costing taxpayers.

“The tactic doesn’t work,” says Representative Cole. “I don’t see any upside.”

Government shutdown: How did we get here?

Like a stone thrown into water, a government shutdown initiated in Washington will ripple out across America.

Unless the House and Senate can agree to an 11th-hour stopgap funding measure, the government will run out of money at 12:01 a.m. on Sunday, affecting millions of government employees and the citizens their departments serve.

While not every government activity would stop, there would be significant disruptions, particularly if a shutdown lasts for more than a few days.

Social Security checks, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs benefits will still be distributed in the case of a shutdown, and Medicaid has funding to keep it operating for three months. Still, certain operations within these necessary services will be affected. Individual states, which administer Social Security claims, will have to determine if they have the funds to pay those employees during a shutdown. The issuing of replacement Medicare cards will be paused, regional Veterans Affairs offices will close, and there will be no grounds maintenance at national veterans cemeteries.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (or SNAP) has enough funds to continue serving 40 million Americans at least through October. But if the shutdown were to continue beyond that, there would be “serious consequences,” Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said earlier this week. He estimated he could keep WIC, the supplemental food program for women, infants and children that serves more than 6 million Americans each month, open for a day or two with a contingency fund. Some states may have their own WIC fund reserves, but if there is a shutdown, says Mr. Vilsack, “WIC shuts down.”

Americans’ air travel could also be affected. Air traffic controllers are expected to be on the job without pay, but security lines could slow or stall if Transportation Safety Administration workers call in sick to protest working without an active income, as they did during the last government shutdown in 2019.

The shutdown would even affect panda goodbye parties, as some Washington residents decry on social media. In the absence of government funding, all Smithsonian institutions – including the National History Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and the National Zoo will close. That includes a panda cam and sendoff soirees that have been planned for the zoo’s three pandas before they return to China in early December.

The percentage of federal employees who will be furloughed or asked to work without pay varies by department. During the most recent shutdown in 2018-19, more than one-third of the 2.2 million federal workers were affected. But after the passage of the Government Employee Fair Treatment Act amid the 2019 shutdown, any furloughed federal employee who is required to work is guaranteed back pay. Still, this postponement of pay could affect workers’ ability to pay rent and other expenses.

While there’s plenty of partisan blame to go around, the underlying fact is that Washington’s budget process is broken – and has been for years. Shutdowns have become showdowns, a last-ditch effort to underscore party objectives and spending priorities. While sometimes nudging Washington toward fiscal restraint, in recent decades shutdowns have mainly gummed up the works, hurt American citizens, and cost taxpayers.

Obamacare is still here after Republicans shut down the government in 2013 to get rid of it. DACA, the program that would defer deportations for children of unauthorized immigrants, has still not been enacted after Democrats shut down the government in 2017. And the border wall is still only partially built despite a 2018 GOP shutdown over that issue.

“The tactic doesn’t work,” said Oklahoma Republican and Rules Committee chair Tom Cole, facing his fourth shutdown as a congressman. “I don’t see any upside.”

A familiar pattern

It didn’t have to be this way.

Everyone knew the government would run out of money on Sept. 30. But in recent years, “Congress has gotten used to not getting its business done on time,” says Representative Cole.

Indeed, it’s settled into a familiar pattern. First, Congress crashes through the main deadline at the end of the fiscal year. Then it passes a stopgap funding measure to keep the government functioning another two or three months. When that deadline looms, it puts all budget priorities into one gigantic bill, called an omnibus. At the 11th hour, everyone gets to vote yes or no on the entire package – likely without having time to read the whole bill.

House conservatives wanted it to be different this year. They wanted to go back to the way it used to be done: 12 different bills for 12 different parts of government, with time to read and consider each one individually, and debate specific programs and priorities. No omnibus.

But that process got stalled amid intra-GOP squabbling over how much to cut government spending amid record national debt. Some conservatives were aggrieved by a compromise Speaker McCarthy made with Democrats earlier this year to avoid a national default. They shut down the floor this summer in protest. Frustration at these members – who are now requesting lengthy debates after prohibiting action for months – was palpable in the halls of Congress this week.

“Those very same members who didn’t want to take votes in June and July are the very same members who are demanding votes in September,” says North Carolina Republican Congressman Patrick McHenry, chair of the Financial Services Committee and a key McCarthy ally. “That slowed down the whole process to build a consensus to produce bills.”

The renegades later blocked votes on appropriations bills, but Mr. McCarthy still let everyone go home for a 7-week summer recess. Now House Republicans have passed only four of the 12 bills – none of which are likely to be approved by the Democrat-run Senate.

Nor are the House and Senate anywhere close to agreeing on a stopgap measure, known in Washington-speak as a continuing resolution or “CR”, to keep the government running while they finish that process. The House tied theirs to providing emergency funding to bolster border security, with illegal crossings at record highs. Senate Democrats don’t like that. Meanwhile, the bipartisan Senate deal includes Ukraine aid – a dealbreaker for many House Republicans.

In a Friday vote, the House CR was torpedoed by 21 Republicans. That reduces any leverage Mr. McCarthy may have had to push the Senate to include more border provisions. The soonest the Senate could advance their CR would be Saturday morning. Even once it passed, the two chambers would have to bridge their differences.

Democrats were already blaming the GOP for the impending shutdown, and turning it into a campaign issue. New York Congressman Mike Lawler, a freshman Republican who just won a very competitive race, says Democrats have already started spending millions of dollars in his district – even though he’s against the shutdown.

The standoff is also likely to hurt whatever bipartisan goodwill remains in Congress. In the House, Democrats and even some moderate Republicans are frustrated with Speaker McCarthy for letting himself be held hostage by a handful of conservative renegades.

“It’s the same movie, with the same ending and we all have to sit through the credits,” says Rep. Dean Phillips, a Minnesota Democrat and member of the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus. Last week, the group’s 64 members endorsed a bipartisan framework for resolving the standoff. “It seems to me that the speaker feels he has to walk down this dead end, even though he knows it’s a dead end, only to then walk back to an intersection.”

Eventually, a resolution involving both parties

Given that Republicans control the House and Democrats the Senate and the White House, the eventual solution must be bipartisan.

And both sides are blaming the other for not recognizing that.

Rep. Pete Aguilar of California, who chairs the Democratic caucus in the House, called the Republicans’ proposed border security measures “fantasy land.”

Rep. Dusty Johnson, a South Dakota Republican who helped broker the House CR with border security provisions, faults Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York. Senator Schumer is showing “shocking little interest” in understanding the “needs” of House Republicans, he says.

“He continues to think he’s operating in a world of one-party government where the House is going to go along with the Senate’s plans,” adds Representative Johnson. “This House will not go along with that Senate’s plans.”

Eventually, House and Senate leaders will have to agree on a CR. This could mean the Senate adding some border security funding, which Texas Sen. John Cornyn this week called a “golden opportunity.” Support in the House will likely come from a bipartisan majority, as it did with the debt-ceiling deal, meaning the Ukraine aid provision would not be a dealbreaker.

Once that happens, Speaker McCarthy will be left to pick up the pieces and try to get the remaining eight appropriations bills passed before the CR runs out.

GOP Rep. Tim Burchett, a fiscal conservative from Tennessee, says that the Sept. 30 deadline is no mystery. The GOP could have made it by more methodically pursuing their goal of passing individual spending bills as they have this week.

Whimsically, he quotes a Democratic colleague from his days in the Tennessee legislature: “If we went a little slower, we would have gotten there a little faster.”

Podcast

Rejecting an easy narrative on age in politics

Isolated and magnified, incidents that seem to show politicians of both parties struggling with the effects of aging can feed a storyline that’s incomplete. In our weekly podcast, our D.C. bureau chief outlines how to deliver a fuller picture.

For the first time in American politics, age is emerging as a dominant concern in how the public views – and the press covers – political leadership. In recent polls, 75% of Americans say that President Joe Biden is too old to serve for a second term, and half say the same for his leading rival, former President Donald Trump.

“We’re talking about Joe Biden’s age more than just about anything else,” says Linda Feldmann, the Monitor’s Washington bureau chief. “And so it’s become the raging issue of the day.

“People just jump on every public sign they can get that he’s not mentally sharp,” Linda says on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast. “If the president trips going up the steps of Air Force One, that is captured on video and replayed mercilessly, particularly by conservative media.”

The death Thursday of California Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who was the oldest member of Congress, is another reminder of the age issue. She had recently faced calls to resign over questions about her mental acuity.

In the past, skillful politicians managed to disarm the notion that age equals frailty with a clever quip or self-effacing humor, as when Ronald Reagan told a 1984 debate audience he would not “exploit ... [his] opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

But given the capacity of the press and social media to amplify lapses, every stumble in the 2024 campaign risks owning the daily news narrative. If there’s a cellphone in every pocket, vulnerability on the campaign trail is hard to hide and any gaffe risks becoming a meme.

“There’s nothing that compares to being in the presidency of the United States,” Linda adds. “The entire world is watching. It just makes the age issue probably more important than it should be.” – Gail Russell Chaddock and Jingnan Peng.

Find story links and a full transcript here.

Rejecting an Easy, Ageist Narrative

Pakistan’s chief justice aims to restore court’s credibility

Pakistan’s new chief justice is breaking norms by pushing for transparency and accountability – values that bode well for the country’s democratic institutions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Pakistan’s Supreme Court has disqualified popularly elected politicians from holding office, legitimized military takeovers, and allowed the constitution to be abrogated on numerous occasions.

Now, its new chief justice has vowed to restore the court’s credibility.

Qazi Faez Isa has been described as a sort of legal “maverick” for his bold and sometimes controversial decisions, which often place him at odds with Pakistan’s politically influential army. He has consistently championed constitutional integrity and accountability in Pakistan’s legal system.

Restoring Pakistanis’ faith in the top court is no small task, especially considering the brevity of Chief Justice Isa’s term, which comes to an automatic end in October 2024, and the fact that he’s inherited around 57,000 unresolved cases. But his first weeks on the job have filled many with hope.

Within days of taking the oath of office, Chief Justice Isa opened the court to cameras and allowed his first hearing to be broadcast live.

“It was the best possible thing he could have done,” says veteran court reporter Abdul Qayyum Siddiqui, who hopes the practice will continue with other cases of public interest. “This is a first step toward transparency and a huge moment in Pakistan’s checkered judicial history.”

Pakistan’s chief justice aims to restore court’s credibility

Pakistan’s new chief justice has hit the ground running.

Since his swearing-in on Sept. 18, Qazi Faez Isa has heard several cases and, for the first time in the institution’s history, allowed cameras into the courtroom to broadcast hearings live. On Thursday, he harkened back to one of his most famous judgements, bemoaning the defense ministry’s failure to weed out military personnel who violated their oath through political meddling.

“The constitution emphatically prohibits members of the Armed Forces from engaging in any kind of political activity,” read the 2019 verdict, authored by then-Justice Isa.

That judgment sent shock waves throughout Pakistan’s legal landscape at the time, not least because the superior judiciary – with some notable exceptions – has historically sided with the country’s powerful military establishment. Over the course of its tainted history, the Supreme Court has disqualified popularly elected politicians from holding office, legitimized military takeovers, and allowed the constitution to be abrogated on numerous occasions.

Now, sitting at the pinnacle of the country’s legal system, Chief Justice Isa has vowed to restore the court’s credibility. He aims to boost transparency, attack the Supreme Court’s massive case backlog, and uphold the constitution. It’s no small task, but his judicial track record and first weeks on the job have filled many with hope.

“I just think he’s a man of his word; he’s a man for whom his reputation is very important,” says lawyer and political commentator Abdul Moiz Jaferii, who appreciates the chief justice’s clear and consistent position on issues like constitutional integrity and democracy. “If he does [fulfill his goals], it will be better for the court and better for the country.”

Respected reputation

Chief Justice Isa – who has been described as a sort of legal “maverick” for his bold and sometimes controversial decisions – has risen to the country’s highest judicial post at a time when many have lost faith in Pakistan’s democratic institutions. Despite an outgoing army chief’s promise that the military’s days of political meddling were over, analysts say that under the new caretaker government, generals have actually strengthened their grip on levers of power.

Yet Chief Justice Isa’s ascension is no surprise. In Pakistan, chief justices automatically retire at age 65, and the most senior colleague takes their place. He joined the bench in 2016, and prior to that he served as the chief justice of Balochistan High Court.

Throughout his tenure on both courts, the justice built a reputation for his commitment to progressive Islamism, fierce condemnations of those in power, and protection of religious minorities. It’s a career that’s often placed him at odds with Pakistan’s powerful army.

Within months of his incendiary 2019 judgment, the government of then-Prime Minister Imran Khan filed a reference against Justice Isa, alleging that he had acquired three properties in London in his wife’s name and failed to disclose them in his wealth statement. Mr. Khan, who has since fallen out of favor with the Pakistani military and is currently in prison after being convicted of illegally selling state gifts, said earlier this year that filing the reference was a mistake. He insinuated that it had been devised on the orders of the military officials.

“One of the first things Mr. Khan has said openly is that the prime minister is the person on the front line, but not the person who has the authority,” says Mr. Khan’s lawyer, Intazar Panjutha. “When this petition was filed, Mr. Khan was bypassed, and it was done without his consent.”

Mr. Panjutha remains optimistic, however, that Chief Justice Isa will succeed in restoring the credibility of the Supreme Court. “The most important thing is that he has always talked about civilian supremacy,” he says. “He has an image of standing up for human rights, and he talks about the supremacy of the constitution, so we hope he’ll find novel ways of improving the administration of justice.”

Cautious optimism

One of the justice’s early changes could prove seismic: Within days of taking the oath of office, Chief Justice Isa allowed his first hearing to be streamed live online. The session, which dealt with the question of whether parliament had the authority to curb the power of the chief justice, was also broadcast on most major news channels.

“It was the best possible thing he could have done,” says veteran court reporter Abdul Qayyum Siddiqui, who hopes the practice will continue with other cases of public interest. “People were glued to their screens. This is a first step toward transparency and a huge moment in Pakistan’s checkered judicial history.”

This checkered history became the subject of an aside from the new chief justice, who admitted during the televised session that the court had not always succeeded in delivering justice.

“The problem is that our egos have become really big,” he said. “We’ve made mistakes. I’ve made mistakes. Let’s admit them. ... Otherwise, the constitution has no value.”

Amid the general optimism surrounding the new chief justice, some are calling for Pakistanis to temper expectations. “Being an incurable optimist, one lives in hope,” says human rights defender Tahira Abdullah, “but there is a need to be realistic also.”

Despite the justice’s “undoubted bona fide intentions,” Ms. Abdullah sees some serious barriers to success. Chief among them is the brevity of his tenure, which comes to an end in October 2024 when the chief justice turns 65, as well as the backlog of around 57,000 unresolved cases that he has inherited.

Nevertheless, Ms. Abdullah has lauded the new chief justice for setting “a positive tone and direction for the Supreme Court of Pakistan to move forward.”

Longtime columnist Nusrat Javeed has also expressed cautious hope, while praising the way Chief Justice Isa handled “the vindictiveness” he faced under the Khan administration.

“Justice Isa’s conduct has always been pretty independent, and there’s no doubt he’s a principled man,” he says. “But how much can one individual change a system that has become corrupt to the core? ... That’s a big question. So we’ll just have to wait and see.”

Difference-maker

Young, Black & Lit steps up to fill gap in children’s books

What if you went to the bookstore and saw no one on the shelves who looked like you? One couple is addressing that deficit for young Black children, supporting literacy and identity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Anne Stein Contributor

Five years ago Krenice Ramsey was hunting for a gift for her young niece Kalaya. But even in a big-box bookstore in suburban Chicago, she couldn’t find children’s offerings with young Black girls as the main character.

After coming up short, she spent more time searching, found a few books online, and donated them to an Evanston community center. At the time, she was dating her now-husband, Derrick Ramsey, and he suggested she give books, about boys this time, to an Evanston barbershop.

“Folks responded, and the more we talked about it,” Ms. Ramsey says, “the more we realized that this might be a much bigger idea, so we grew it from there.”

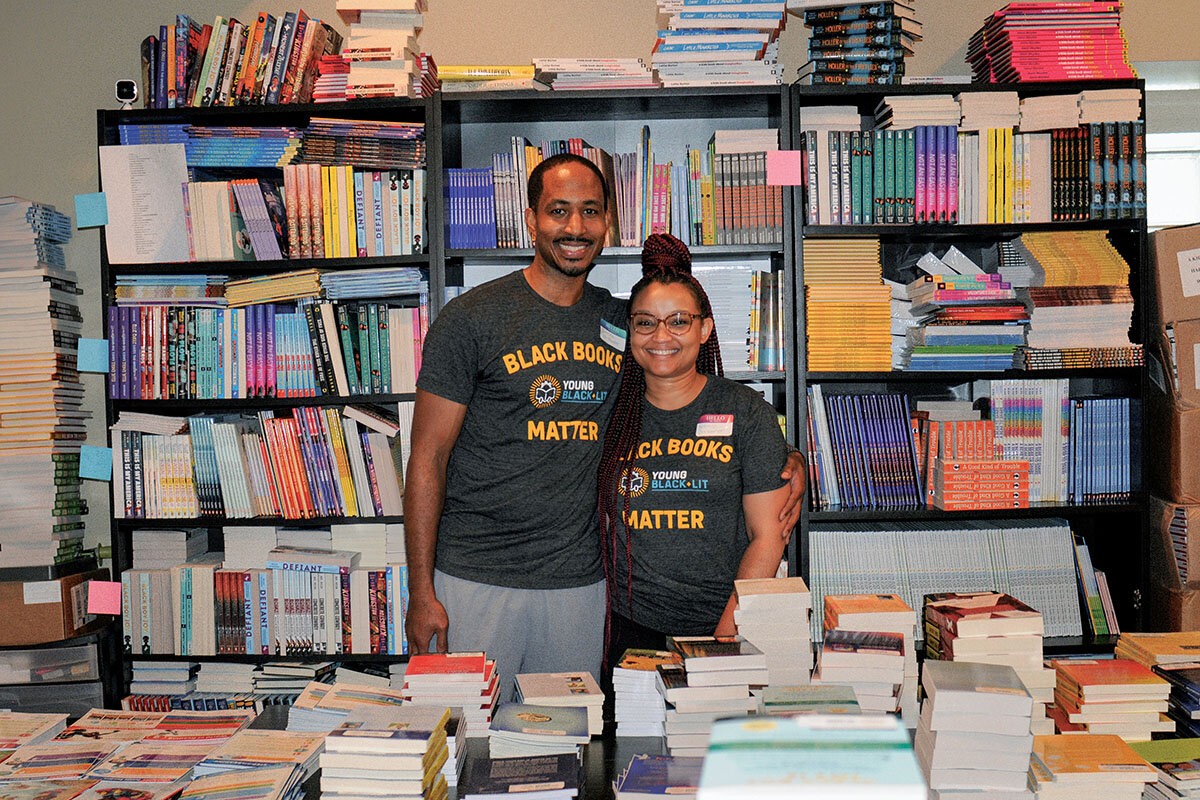

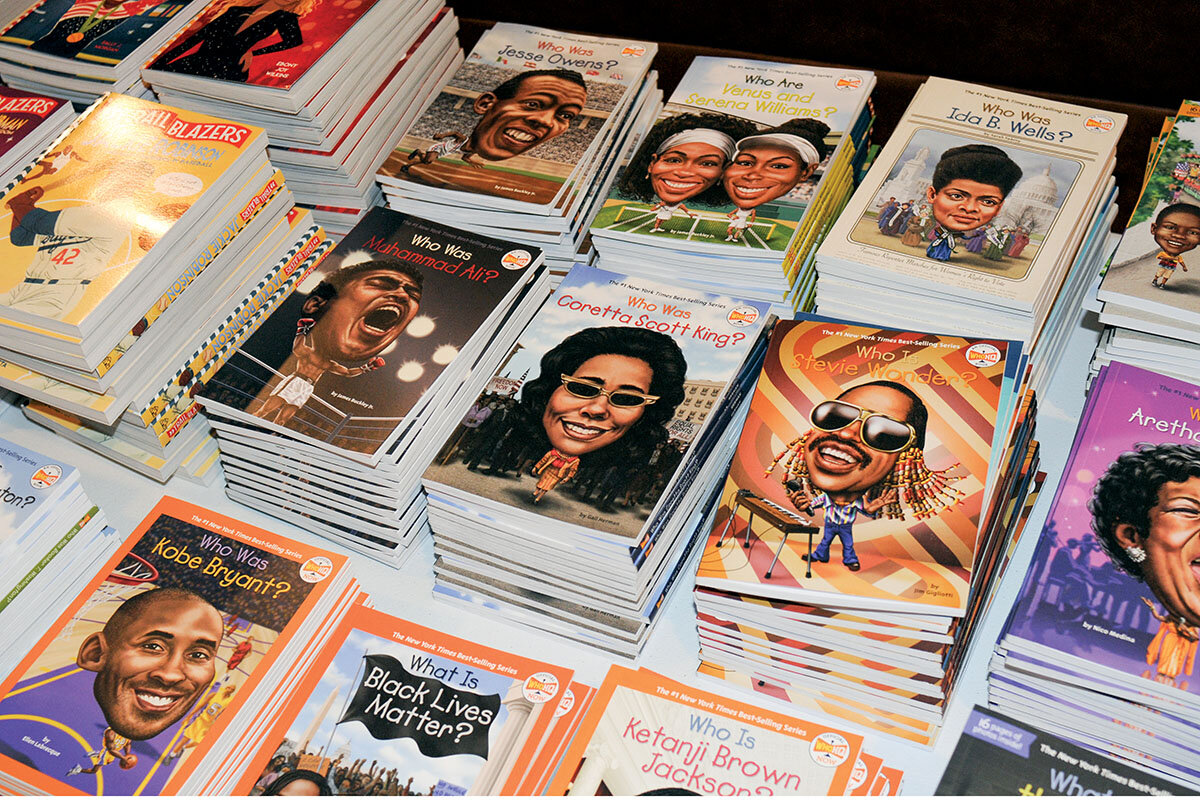

In 2018, the two co-founded Young, Black & Lit, a nonprofit whose mission is to provide new fiction and nonfiction books featuring people who are Black to schools and youth organizations across the United States. Since its inception, the group has distributed more than 75,000 books.

“We want Black children to think about being all the great things they can be in life,” says Mr. Ramsey. “When you don’t have a bunch of positive Black representation in the media, books can be a simple way to provide a view of life and opportunities, and seeing that is important.”

Young, Black & Lit steps up to fill gap in children’s books

Krenice Ramsey was a self-described book nerd growing up in Evanston, Illinois.

“I always had a book in my hand,” says Ms. Ramsey, an attorney at the Chicago office of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. “I loved reading anything and everything, and I continue to love books.”

Five years ago she was hunting for a gift – a book, of course – for her young niece Kalaya. But even in a big-box bookstore in suburban Chicago, she couldn’t find children’s offerings with young Black girls as the main character. “I was really struggling to find books that were culturally relevant and had characters that looked like and spoke like and had similar experiences to her,” she says.

After coming up short, she spent more time searching, found a few books online, and donated them to an Evanston community center. At the time, she was dating her now-husband, Derrick Ramsey, and he suggested she give books, about boys this time, to an Evanston barbershop.

“Folks responded, and the more we talked about it,” Ms. Ramsey says, “the more we realized that this might be a much bigger idea, so we grew it from there.”

In 2018, the two co-founded Young, Black & Lit, a nonprofit whose mission is to provide new fiction and nonfiction books featuring people who are Black to schools and youth organizations across the United States. Since its inception, the group has distributed more than 75,000 books.

“We want Black children to think about being all the great things they can be in life,” says Mr. Ramsey, who works in financial services. “When you don’t have a bunch of positive Black representation in the media, books can be a simple way to provide a view of life and opportunities, and seeing that is important.”

Given the current environment, he says, which includes “efforts to ban books telling Black stories and [to] diminish Black history,” the pair’s effort at increased access for young people “is even more important.”

“Books are a luxury”

As the couple’s relationship evolved, so did Young, Black & Lit, which initially started in Ms. Ramsey’s Chicago apartment. The two have since married, become parents to a toddler, and moved back to Ms. Ramsey’s hometown of Evanston, where the organization has an office.

In 2018, the two were distributing about 50 books a month aimed at children in pre-K through eighth grade. Today Young, Black & Lit gives away 3,000 books monthly nationwide – many to groups that help low-income children. The effort is funded by grants, partnerships, and individual donations. Books have gone to libraries, church camps, Girl Scout and Boy Scout troops, doctor’s offices, and back-to-school fairs.

“I grew up reading books, and in our house we have dozens of books, but in low-

income communities, books are a luxury,” explains Mr. Ramsey, who hails from Detroit and was a big fan of the “Goosebumps” series as a kid.

For older middle schoolers, says Ms. Ramsey, books tackle some complicated topics: about historical Black figures, about grief and empowerment, and about everyday life experiences, such as visiting with grandparents or playing with a snail in the backyard.

“Our stories aren’t monolithic,” she says. “They also expand the mind and give you language to express what you are experiencing.”

One of the organization’s first partners was Evanston’s Oakton Elementary School, which has a population that generally includes about 43% Black, 26% Hispanic, and 24% white students. Every child in kindergarten through second grade received two to three books a month to take home and keep.

“It was a year before the pandemic, and it was transformative,” says former Oakton Elementary Principal Michael Allen. “It allowed children to build their home library.

“I saw improved self-esteem among Black students,” says Dr. Allen, who adds that the books are equally valuable for all students. “The books helped defy stereotypes and helped children develop an appreciation for other cultures. If students don’t have authentic perspectives on other cultures, when they go out in the world and just have stereotypes, it puts them at a great disadvantage.”

Carrie Swan teaches fourth grade and Louise Rizio teaches fifth at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Literary and Fine Arts School in Evanston. Each year, the educators receive books from Young, Black & Lit for their classroom libraries.

“When I first started teaching 14 years ago, it was difficult to find children’s books with a child of color as the main character,” Ms. Rizio says. “I didn’t think of this metaphor but it really sums it up: Everyone should be able to pick up a book and have a doorway into another culture, or a mirror reflecting their own culture.”

“It builds empathy in children to read about different kids who have different experiences,” adds Ms. Swan. “It might make them think differently when they engage with other humans, and that’s a powerful thing that books can do.”

To get any kind of free book is a gift, says Ms. Rizio, “so to get these books that celebrate diversity is a treasure.”

A milestone year

To mark its fifth anniversary this year, Young, Black & Lit is putting 200 books in every Evanston elementary and middle school, and is also piloting the Direct to Home Lit Year Program. Up to 200 Evanston kindergartners through third graders who sign up will get 15 age-appropriate books for free, mailed to their homes.

The organization is also providing books to every Reach Out and Read site in Illinois. The nationwide program allows doctors (usually pediatricians) to give a book to every child at their well-visit appointment.

“They are absolutely beautiful books, and the kids love them,” says Brooke Turnock, a pediatrician at a community health center on Chicago’s West Side. “I have kids who come in and ask me for a book, not a sucker!” Dr. Turnock has practiced medicine for 18 years and heads Reach Out and Read at her clinic.

“The concept of seeing yourself in a story can help the child develop a love of reading, and that’s key to neurologic and literacy development,” she says. “In the areas we serve, which are mostly low-income, a lot of the parents want their children to be highly educated but don’t know where to start or don’t have funds to purchase books.”

In the future, says Mr. Ramsey, Young, Black & Lit would like to be able to put books into the home of every child who wants to understand the Black experience, and to build home libraries for every kid across the country.

“For me, for both of us, this doesn’t feel like work,” says Mr. Ramsey. “We know we’re positively impacting some person or community. It’s a labor of love.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Migrant flows and self-governance

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Mass flows of migrants in parts of the world are adding new urgency to the international community’s focus on what compels people to risk perilous journeys in search of uncertain futures. Two countries of migrant origin in Central America are now showing that stemming the flight of their citizens starts with ending corruption and impunity.

In Guatemala, President-elect Bernardo Arévalo is butting heads with public prosecutors, judges, and lawyers bent on annulling his upset ballot victory in August. In neighboring Honduras, President Xiomara Castro is trying to transform a political establishment long implicated by graft, including ties with drug traffickers.

At each step, the public has been watching. “They are saying that we are coming to defend Arévalo,” Sandra Calel, an Indigenous activist who joined a protest rally against the attorney general in Guatemala last week, “but we are really coming to defend democracy, which is what the people elected. Because we are tired of so much corruption.”

Two points of migrant origin in Central America are charting new routes to the rights of the self-governed – and perhaps more reasons to stay at home.

Migrant flows and self-governance

Greece has seen a threefold increase in the number of migrants reaching its shores illegally this year. In Italy, illegal arrivals have almost doubled. Across the southern United States, nearly 9,000 people have been slipping through gaps in the border daily in recent weeks. These mass flows of humanity are adding new urgency to the international community’s focus on what compels people to risk perilous journeys in search of uncertain futures.

“We must recognize that solutions to irregular migration cannot solely rely on preventing departures, but also on ensuring that we are effectively addressing the various drivers of migration in countries of origin, transit and, oftentimes, in countries of initial destination,” Pär Liljert, director of the International Organization for Migration’s office to the United Nations, told the U.N. Security Council yesterday.

Two countries of migrant origin in Central America are now showing that stemming the flight of their citizens starts with ending corruption and impunity. In Guatemala, President-elect Bernardo Arévalo is butting heads with public prosecutors, judges, and lawyers bent on annulling his upset ballot victory in August. In neighboring Honduras, President Xiomara Castro is trying to transform a political establishment long implicated by graft, including ties with drug traffickers.

A World Bank study published this month shows the correlation between corruption and migration. Using a model based on four measures of corruption, the study found that every one-unit increase in a country’s overall corruption level resulted in an 11% increase in migrant outflow, “while the same increase in the destination country is associated with a 10% decline in in-migration.”

Those findings are confirmed by a deep desire among ordinary people in both Guatemala and Honduras for honest governance and the security and economic opportunities that flow from it. In the latest AmericasBarometer survey in Guatemala, conducted just before the August election, 76% of citizens surveyed said that more than half of the country’s politicians engage in corrupt activities. Mr. Arévalo promised a big broom. His victory marked a popular rejection of fear and resignation. “The first job was to defeat defeatism,” Sandra Morán, a once-exiled former member of Congress who voted for Mr. Arévalo, told The Intercept earlier this month.

That mental shift from within may be more powerful than any offer of help from outside the source countries of migration. “Corruption is the system,” Claudia Escobar, a former Guatemalan appeals court judge, told the Council on Foreign Relations last week. “And this will only change when the countries decide that they want to implement a different system.”

Both countries are showing that when the fear of corruption breaks, virtuous cycles begin to form. In Guatemala, judges – a professional class with deep alleged ties to corruption – have rejected efforts by the attorney general, herself the target of U.S. economic sanctions for “involvement in significant corruption,” to vacate Mr. Arévalo’s ballot victory. In Honduras, even Ms. Castro’s opponents in parliament have grudgingly backed legislative reforms meant to counter impunity.

At each step, the public has been watching. “They are saying that we are coming to defend Arévalo,” Sandra Calel, an Indigenous activist who joined a protest rally against the attorney general in Guatemala last week, told The Associated Press, “but we are really coming to defend democracy, which is what the people elected. Because we are tired of so much corruption.”

Two points of migrant origin in Central America are charting new routes to the rights of the self-governed – and perhaps more reasons to stay at home.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Overcoming impasses

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

Willingness to look past personal viewpoints and see the unity inherent in God’s children enables us to experience progress where it’s unexpected.

Overcoming impasses

We accomplish so much in cooperation with others – whether on a personal scale or on a global stage. But sometimes in trying to work together, it’s difficult to find a smooth path forward. Despite how things appear, however, God didn’t create us with irreconcilable differences. In truth, God’s children are at one with each other and harmonious, expressing the one divine Mind.

We’ve selected an assortment of pieces from the archives of The Christian Science Publishing Society that illustrate how embracing the truth of our innate goodness as children of God clears the way for us to advance toward noble goals.

There really are no bubbles into which we are divided in God’s universe. The author of “Pop the bubbles of division” shares how embracing the limitless thoughts that come to us from God enables us to overcome any standstill.

Knowing that each of us is governed by divine Love, with no roadblocks, we can find progress in our work together, as the writer of “The timeless basis for cooperation” experienced in the workplace.

We grow in our confidence that productive cooperation is the norm as we learn about a spiritual sense of unity, the author of “Unity, not division, is what’s natural” shares.

In “A spiritual response to political division and upheaval,” the Editor of the Monitor explores how holding to an understanding that there is only one God, and therefore one spiritual creation, helps us overcome the suggestion that we are opposed to each other.

The foundation for completing what we set out to do, the writer of “How to work together” shows, is discovering that the divine Love that is our source is absolutely unlimited.

And “How do we get things done together?” considers how the humility to follow God’s will propels us forward toward good results.

Viewfinder

A dance amid war

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. We hope you’ll join us again Monday, when Laurent Belsie will look at public debt, deficits, and the fiscal realities behind a government shutdown.