- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When strangers become neighbors

Sarah Matusek

Sarah Matusek

I rented apartments for years in New York City in near anonymity, never bothering to make friends in the building. Moving to a new apartment in Denver a couple of years ago changed that.

For the first time in a decade, I know my neighbors’ names.

I came to know them through their care.

Next door is George, who never fails to stop and say hello – and whose flowers I admire from my patio. A few doors down is Susana with the Siamese cat; she throws weeknight soirees. Estella, down the hall to the left, a building veteran of 30 years, will bring you chili just because.

My neighbors had welcomed me warmly at the start, which prompted a sharing of myself, too. We’ve traded meals and errands, cards and hugs, through sickness, grief, and joy.

The Monitor in recent weeks has also offered stories of neighborly care amid conflict. Whether it’s stockpiling socks and snacks in a Jerusalem basement or turning a Gaza Strip beauty salon into a shelter, strangers are improvising love in war.

Our 11th-floor community in Colorado faces much smaller stakes, of course. But I see the impulse as the same.

Estella makes big pots of chili because “I don’t know how to cook it any other way,” she says. “I wanted to share.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Besieged by all, Israeli Arabs preach message of coexistence

Members of Israel’s Arab community, perched precariously amid this latest round of violence in Gaza, say they grieve for both sides and have much to offer: a message of peace and coexistence. If only everyone would listen.

Variously describing themselves as Israeli Arabs or Palestinians, citizens of Israel with a Palestinian identity are suffering a twin tragedy from the escalating Israel-Hamas war. They are grieving friends and relatives killed by Hamas in Israel and by Israeli missile strikes in Gaza.

They say they cannot publicly share their pragmatic message of peace and coexistence without being attacked on every side, including facing arrest by Israeli police. But by their actions and expressions of solidarity, they say they hope to impart the values of “shared humanity” and the “equal value of life.”

“Whenever I post on social media, I face attacks from people in Gaza and Arab states. If I post about innocents being killed in Gaza, I can face legal action and harassment in Israel,” says Ghadir Hani, an activist with Standing Together, a progressive Jewish-Arab peace movement that has been fighting against hate speech targeting either community.

“If we say anything, the Arab world calls us traitors,” says David, a Nazareth art gallery owner who did not wish to use his real name. “We have a beautiful message to share because we know peaceful coexistence can work; we have lived it, but,” he mimes a zipping motion over his lips, “no one wants us to speak. Politically and legally, in many ways, we can’t.”

Besieged by all, Israeli Arabs preach message of coexistence

At a hotel perched on a hillside above Nazareth, fresh Israeli evacuees from northern kibbutzim near the Lebanese border sit for breakfast at tables next to Arab families.

On a breezy balcony overlooking the predominantly Christian-Arab town in the Galilee region, they laugh and chatter as their children play together in an adjacent courtyard.

“This is the way things should be. We are proof that coexistence is not only a possible future, but the only possible future,” says Ghassan, a server. “But we can’t make our voice heard.”

Variously describing themselves as Israeli Arabs or Palestinians – they are citizens of Israel with a Palestinian identity – they are suffering a twin tragedy from the escalating Israel-Hamas war, grieving friends and relatives killed by Hamas in Israel and by Israeli missile strikes in Gaza.

Pinned in by Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia in the north, a far-right Israeli government that is detaining anti-war activists, Israeli public pressure campaigns, Palestinian factions, and an enraged Arab street, these Arab and Palestinian Israelis say they cannot publicly share their pragmatic message of peace and coexistence without being attacked on every side.

Deepening their silence are ongoing far-right Israeli pressure campaigns pushing companies, schools, and universities to fire Arab Israelis or expel them from school for expressing solidarity with civilians in Gaza.

But by their actions and expressions of solidarity, they say they hope to impart the values of “shared humanity” and the “equal value of life.”

“We are in mourning”

Of the 2.1 million Arab and Palestinian citizens of Israel, many refer to Oct. 7 as a “black day.”

Among the 1,400 people killed in Hamas’ attack that day, 18 Israeli Arabs were killed and hundreds were displaced. Israeli Arabs say they all have friends or co-workers who were killed or kidnapped. And they say Israel’s war against Hamas and siege of Gaza, in which as of Wednesday 5,700 Palestinian residents of Gaza, including 2,000 children, have been reported killed, is a second, deep-cutting “tragedy” for the community.

“We are in mourning. Innocent Israeli men, women, and children lost their lives. And now the Israeli military is killing and starving innocent men, women, and children in Gaza,” says Ibrahim, who did not wish to use his real name. He spoke in Nazareth, hours after returning from a shiva mourning gathering for a Jewish friend and neighbor whose relatives were killed by Hamas. “For what?”

“It is a very difficult situation,” says Ghadir Hani, an activist with Standing Together, a progressive Jewish-Arab peace movement that has been assisting Israeli evacuees, renovating bomb shelters, and fighting against hate speech targeting either community.

Ms. Hani lives in the mixed Jewish-Arab town of Acre, north of Haifa, and has lost Jewish Israeli friends who were killed or kidnapped in the Hamas attack.

“Whenever I post on social media, I face attacks from people in Gaza and Arab states. If I post about innocents being killed in Gaza, I can face legal action and harassment in Israel,” Ms. Hani says.

“They have to understand that we have relatives in Gaza, we have Israeli Jewish friends. Their humanity is our humanity. Why do we have to always condemn?” she says. “We are all hurting right now.”

Even anti-war expressions and calls to end the siege in solidarity with the suffering Gazan children have become sensitive.

“Chilling effect”

Israeli police broke up peaceful anti-war protests in Haifa and Umm al-Fahm last week and arrested six people despite their not raising Palestinian flags – deemed at times by Israeli police to be a symbol of incitement that far-right government ministers want banned – or chanting pro-Hamas or blatantly pro-Palestinian slogans.

Israeli Police Chief Kobi Shabtai said last week that police were following a “zero tolerance” approach and that there was “no authorization for protests” in wartime.

Legal advocates say Israeli law allows for peaceful protests even amid the war.

Sawsan Zaher, legal adviser at the Emergency Coalition of the Arab Society in Israel, says as of Tuesday Israeli authorities have arrested more than 60 Arab citizens for social media posts deemed to be “incitement,” “behavior that could harm public order,” or “terrorism” – for sentiments ranging from denouncing the killing of children in Gaza to posting the Palestinian flag. Israeli police say they have arrested 63 individuals “on suspicion of supporting or inciting terror.”

One recent high-profile arrest was of Nazareth singer Dalal Abu Amneh, who was detained and placed under house arrest for posting “there is no victor but God” alongside a Palestinian flag on her Facebook page, a post she has since deleted.

Several Nazareth residents cited the singer’s detention and the “tense atmosphere” in their refusal to speak on the record to the Monitor or provide their name. Multiple community leaders and Arab members of Israel’s parliament declined to be interviewed.

Although legal advocates say the arrests will not hold up in court, they say the pressure campaign by Israeli activists has resulted in private employers firing 50 Arab Israelis and universities expelling or suspending 100 Arab students.

“It is creating a huge chilling effect” in the community, says Ms. Zaher. “It is another reminder you are not equal, and it has a damaging effect on the social fabric.”

So too is the pressure from Palestinian factions and Arabs who view coexistence as “surrender” and “propaganda,” due to the power imbalance between Israelis and Palestinians in the conflict and, they say, in international media coverage.

“If we say anything, the Arab world calls us traitors,” says David, a Nazareth art gallery owner who did not wish to use his real name. “We have a beautiful message to share because we know peaceful coexistence can work; we have lived it, but,” he mimes a zipping motion over his lips, “no one wants us to speak. Politically and legally, in many ways, we can’t.”

Abu Youssef, a Nazareth baker, emphasizes the pressure from both sides. “Palestinian factions don’t want us to publicly criticize Hamas because they think that it means we support the war killing of Gazan civilians. Hamas are extremists; they don’t represent us. They didn’t ask us if we wanted to be dragged into war that makes all our lives miserable,” he says. “At the same time Israel pressures us to condemn and condemn like we are responsible, like we are constantly under suspicion.”

Northern residents warily await a ground invasion into Gaza and any Hezbollah response.

Should Hezbollah open a northern front, Arab communities would likely be in the line of fire of Hezbollah missiles. Still fresh in residents’ minds is the destruction in Haifa and Nazareth and deaths among Arab Israelis from the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war.

“We are waiting for the missiles to drop on us at any second,” Hamed, a Haifa falafel vendor, says calmly as he wipes the restaurant counter Monday evening, moments after serving sandwiches to two young Israeli soldiers. “This is our home and our community. We are in front of the firing line of these conflicts, but we have the least influence over events.” He shrugs. “We live our life and hope for the best.”

“When a missile comes at you, it doesn’t stop and ask, are you Jewish or an Arab?” adds Mohammad, a Nazareth driver.

“We don’t need more war”

Also fresh in the community’s memory is the Jewish-Arab intercommunal violence during the Gaza war in May 2021 that killed three people and injured hundreds, which Arab residents say they wish to avoid.

Grassroots activists such as those at Standing Together are working to defuse potential tensions and bridge gaps among Arabs and Israelis, despite the extreme rhetoric.

“In Israel there are extremists who say the land ‘from the river to the sea’ is theirs. On the Palestinian side there are extremists who demand ‘from the river to the sea,’” says Mohammad, the driver.

“At the end of the day, the only scenario is for us to live in peace and in equal rights with one another. We don’t need more war or bloodshed to realize it.”

On a Saturday in Nazareth, the markets were unusually empty, the vast majority of stores shuttered, the old market a ghost town.

Arab member of the Knesset Aymen Odeh said in an op-ed and posts on his social media accounts: “Israeli babies, Palestinian babies, they all cry the same, laugh the same. Regardless of their mother tongue, they all communicate in the same way, and want the same simple thing: to live a good life. As leaders, as adults, we have a responsibility toward our young ones to allow them to have a good life.”

Israel-Hamas information war challenges media, public

All wars are also information wars. False and misleading online images from Israel and Gaza have lit up social media. In the instant-news era, verification presents a dilemma for journalists.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As Israel steps up its military operations in Gaza against Hamas, the information war is also intensifying.

Military propaganda is nothing new. But following the mass killing and kidnapping of Israeli Jews on Oct. 7, a torrent of false and misleading online images from Israel and Gaza has become a visual cacophony. It has led many to question what is really happening and whether near-instant news is informing anyone.

The Oct. 17 explosion at al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza City was a case in point: Hamas claimed that an Israeli airstrike had killed hundreds of civilians, a claim that ricocheted across global media outlets. Israel quickly denied this claim and said a militant-launched rocket had misfired and landed on the site. In subsequent days, visual evidence emerged to support Israel’s version of events, which the U.S. Department of Defense also supported, citing its own intelligence. News organizations have tried to verify the source of the explosion by comparing videos and asking munitions experts to examine photos of the site.

The flood of unreliable information creates an ethical dilemma for news organizations, says Philip Seib, emeritus professor of journalism at the University of Southern California. Journalists have a responsibility to verify the facts and be cautious about amplifying unproven claims. “But they can’t postpone too long,” he says, “because the churn online will pass by and the public will be getting information that may not have any journalistic standards applied.”

Israel-Hamas information war challenges media, public

As Israel steps up its military operations in Gaza against Hamas, following the mass killing and kidnapping of Israeli Jews on Oct. 7, the information war is also intensifying. Both sides and their allies are competing for the attention of local, regional, and global audiences looking for the latest news from the conflict, much of it on social media platforms.

All wars are also information wars; military propaganda is nothing new. But a torrent of false and misleading online images from Israel and Gaza has become a visual cacophony that has led many to question what is really happening and whether near-instant news is informing anyone. The images include videos from past conflicts, scenes from action movies, fake posts and screenshots, and doctored statements and photos. Posts are then shared and promoted by partisans or others just seeking clicks and followers.

For news organizations trying to report accurately in a war zone, this flood of unreliable information delivered directly to our screens creates an ethical dilemma, says Philip Seib, emeritus professor of journalism at the University of Southern California. Journalists have a responsibility to verify the facts and be cautious about amplifying unproven claims. “But they can’t postpone too long because the churn online will pass by and the public will be getting information that may not have any journalistic standards applied,” he says.

The Oct. 17 explosion at al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza City was a case in point: Hamas claimed that an Israeli airstrike had killed hundreds of civilians, a claim that ricocheted across global media outlets. Israel quickly denied this claim and said a militant-launched rocket had misfired and landed on the site. In subsequent days, visual evidence emerged to support Israel’s version of events, which the U.S. Department of Defense also supported, citing its own intelligence. News organizations have tried to verify the source of the explosion by comparing videos and asking munitions experts to examine photos of the site.

But it’s easy to manipulate the news media with false claims, knowing that the pressure to be first with breaking news means a rush to report before the facts are clear, warns Peter Singer, a professor of practice in the Center on the Future of War at Arizona State University who studies cybersecurity. “Both the media and the social network firms (or at least their owners) seem to have learned too little when it comes to the deluge of online misinformation and deliberate disinformation that is now the norm in conflicts,” he says via email.

The claims of an alleged Israeli airstrike on a hospital – which is protected from military attacks under the Geneva Conventions – had immediate political and diplomatic consequences: Protests erupted in several Arab countries last week, and a planned summit between President Joe Biden and leaders of Arab countries was canceled. On Monday, The New York Times wrote in a substantial editor’s note that it “should have taken more care” with its initial reporting on the incident, which “left readers with an incorrect impression about what was known and how credible the account was.”

Fog of war – then and now

For much of human history, civilians have been poorly informed or misled about the course of conflicts, including at home. The use of propaganda during wartime, and warnings about its effects, also has a long lineage: English writer Samuel Johnson wrote in 1758, during the Seven Years’ War between Britain and France, that war falsehoods diminish “the love of truth.” In a similar vein, Sen. Hiram Johnson of California, an isolationist who opposed U.S. entry into World War I, was reported to say that “the first casualty when war comes is truth.”

Compared with a century ago, civilians have access to reams of online data and images that, in theory, offer a counterpoint to propaganda by governments and warring factions. Today, much of this information is disseminated by social media platforms owned and controlled by U.S. tech companies. In 2011, when anti-government protests began to spread across Arab countries, Twitter (now called X) and Facebook offered both an uncensored space to organize and a window for the world into the protests that became the Arab Spring.

But to follow the 2023 Gaza conflict on X is to peer into a “fun house mirror” in which almost nothing can be trusted, says Mathew Ingram, chief digital writer at the Columbia Journalism Review. “Most people felt that most of what they were getting through Twitter was credible information ... and the assumption now is that it’s not true.”

Under Elon Musk, who bought Twitter last year for $44 billion, the social media platform has disbanded teams who worked on combating misinformation and hate speech. It has also removed blue check marks from the accounts of politicians, celebrities, and other public figures whose identities had been verified and instead sold check marks to subscribers. Critics say these accounts, whose posts are amplified by X and are then eligible for payments if they go viral, have been among the most active spreaders of misinformation about Gaza, presumably for financial gain.

Using X as a news source “is a lot more work than it used to be,” says Mr. Ingram. “The account could be fake. The information could be fake. The photo could be fake.”

Last year X launched a crowdsourced fact-checking service called Community Notes that is designed to single out suspect posts. Its effectiveness and credibility had been questioned, though, even before the conflict in Gaza. Other social media platforms, such as Facebook and TikTok, have also struggled with misleading posts, as well as disinformation campaigns. An executive from Cyabra, an Israeli bot-monitoring firm, told Reuters that it had uncovered more than 40,000 fake accounts sharing pro-Hamas content and that many had been created long before the attack. “The scale suggests there was pre-prepared content and manpower into getting it out,” said Rafi Mendelsohn, Cyabra’s vice president.

A human problem, not a technical one

While many blame Mr. Musk for weakening X’s guardrails against misinformation, the sheer volume of false and misleading content presents a stiff problem for would-be monitors. “Even if we had a million fact-checkers, I’m not sure we’d be able to solve this problem. It’s a human problem, not a technical problem,” says Mr. Ingram.

In Finland, media literacy is taught in elementary schools. And learning how to check online images to verify their provenance is fairly straightforward, notes Shayan Sardarizadeh, a BBC reporter who specializes in verification of online information. But even professional fact-checkers have expressed concern at how many falsehoods from Israel and Gaza have pinged around the world in recent weeks.

News consumers are often vulnerable to disinformation from war zones because they are primed to believe claims that fit their worldview, says Professor Seib, author of “Information at War: Journalism, Disinformation, and Modern Warfare.” Even if news organizations inject caution into their coverage and seek to set the record straight, however long it takes, they are competing with an unfiltered stream of digital information. “The public has to train itself to say, ‘Here’s what so-and-so says; here’s what the other side says. Let’s wait a minute,’” he says.

In Argentina, populist’s bid falls short

Widespread discontent seemed likely to give populist extremist Javier Milei the edge in Sunday’s Argentine presidential elections, but he scared too many voters. Going into a runoff, he is the underdog.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Amy Booth Contributor

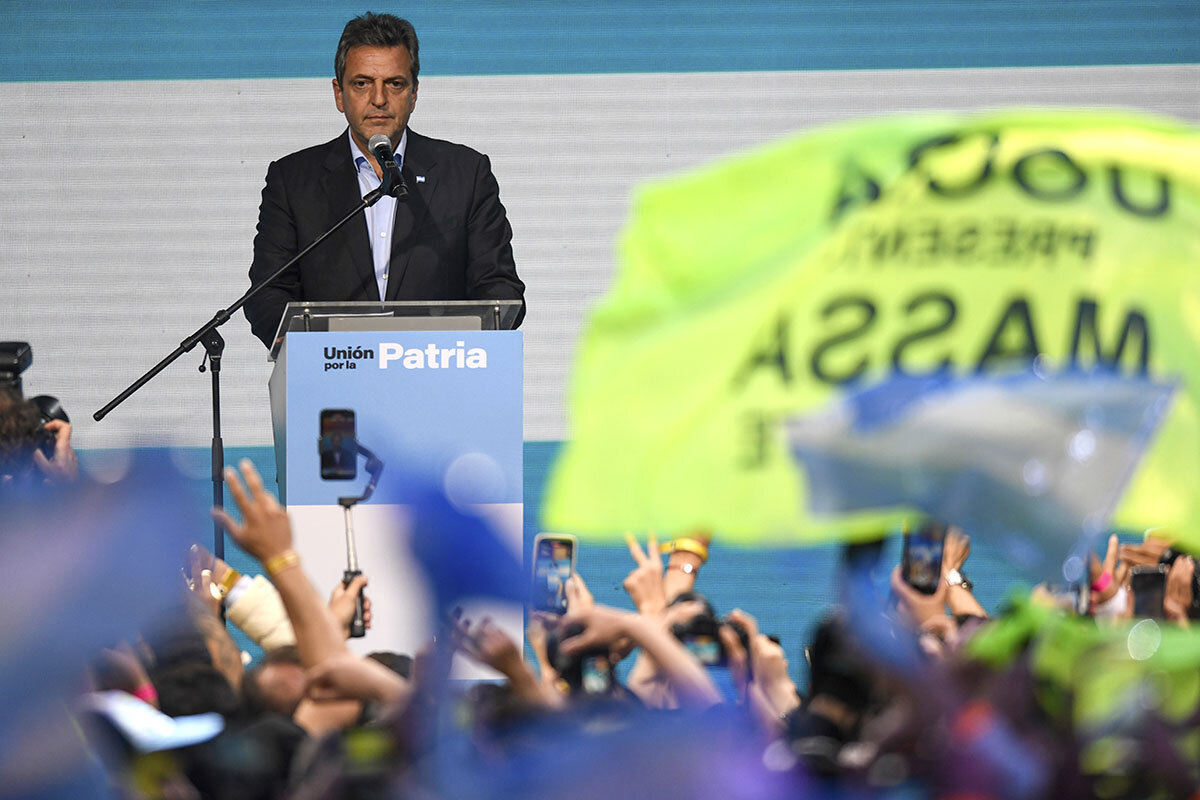

Until the votes were counted in Argentina’s presidential elections on Sunday, it was widely thought that Javier Milei, a populist candidate drawing on Donald Trump’s playbook, and then some, would come out on top.

But despite widespread popular discontent with establishment political parties, Mr. Milei’s radicalism (he wants to dissolve the central bank) and the way he plays down crimes committed by Argentina’s last military dictatorship seem to have prompted second thoughts.

Mr. Milei came second in the first round of the elections, behind the current economy minister, Sergio Massa. Those two will go to a runoff on Nov. 19.

“I think they scared people,” says one local political analyst.

But still, nearly a third of the electorate voted for Mr. Milei. “It has to be a strong call for the attention of Argentina’s political class that about 30% of the population thought they could vote for that sort of thing,” says politics lecturer Lara Goyburu.

“This doesn’t mean that they agree with it,” she adds. “But they’re so fed up with the lack of response to their problems that they’re willing to sacrifice common ground that seemed beyond discussion in Argentina.”

In Argentina, populist’s bid falls short

If anyone was worried about the expected results of Argentina’s presidential race, it’s the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. In the days leading up to Sunday’s election, this group of older women was gathering, their heads wrapped in triangular white headscarves as they have been for decades.

Since April 1977, a year into Argentina’s last military dictatorship, they have marched around the square every single Thursday, demanding to know the fate of their children whom the military disappeared. Their suffering symbolizes the struggle to restore democracy in Argentina.

And now, 40 years on, they are worried that anti-democratic sentiment is rearing its head again in the shape of candidate Javier Milei, a loud, volatile, and relentlessly confrontational far-right libertarian economist who minimizes the crimes of the military, under whose seven-year rule 30,000 people are estimated to have disappeared.

On Sunday, despite polling predictions, the controversial candidate who campaigned on a pledge to largely dismantle the state came in second. But Mr. Milei astonished the country last August by winning primaries that generally foreshadow general election results. And now he will be on the ballot again in a runoff. Even if Argentine voters appeared to have second thoughts about Mr. Milei, he represents a style of politics that shows sign of taking root.

Mr. Milei, of the Liberty Advances coalition, took 30% of the vote, but he was outstripped by the economy minister, Sergio Massa, who won 37%. That, though, was shy of the needed threshold, so the two leading candidates will face each other next month.

Mr. Milei is likely to pick up some votes from supporters of conservative Together for Change candidate Patricia Bullrich, who was knocked out of the contest on Sunday, but her more moderate supporters may opt for Mr. Massa. Observers are unsure which way the vote on Nov. 19 will go.

“I think Milei’s and [running mate] Victoria Villarruel’s appeal to the most anti-democratic values worked against them at the last minute,” says María Esperanza Casullo, a professor of political science at the National University of Río Negro. “I think they scared people.”

Lara Goyburu, a political analyst who teaches at the University of Buenos Aires, echoes that. “It would have really surprised me if Milei had won in the first round,” she says. “His focus on disputing the democratic consensus of 1983 over the past few weeks cut really deeply for a large percentage of the population.”

Career politician vs. populist outsider

Mr. Massa, by contrast, is a smooth-talking career politician who gained prominence as mayor of the picturesque town of Tigre, to the north of Buenos Aires. He shot into the limelight when he was made economy minister last year. He has spent much of his time since then renegotiating the terms of a $44 billion International Monetary Fund bailout loan in the face of severe economic difficulties.

Mr. Milei, at the head of the Freedom Advances coalition, has made his name with a populist campaign against what he calls a corrupt political class, espousing fundamentalist free market policies, arguing that taxation is theft, and advocating the closure of the central bank, the adoption of the U.S. dollar, and the abolition of most government ministries.

He has also disputed the official number of people who died at the hands of the last military dictatorship and chose as his running mate a woman closely associated with that dictatorship.

“It has to be a strong call for the attention of Argentina’s political class that about 30% of the population thought they could vote for that sort of thing,” says Ms. Goyburu. “This doesn’t mean that they agree with it, but they’re so fed up with the lack of response to their problems that they’re willing to sacrifice common ground that seemed beyond discussion in Argentina.”

That is largely because Argentina’s economy is in dire straits, struggling in and out of recession for years. Over 40% of the population lives below the poverty line, including many workers whose purchasing power has been devastated by inflation, currently running at an annual rate of 138%, the worst in 30 years.

This has left many voters feeling that neither the center-left coalition led by President Alberto Fernández, who has ruled since 2019, nor the conservative Together for Change bloc, which had been in charge previously, has been able to turn things around.

“There is discontent with the limitations of democracy to solve peoples’ problems, and ... that was shown at the ballot box,” says Ms. Goyburu. “The political elite’s discourse recently has been far removed from most peoples’ reality.”

For Dr. Casullo, Mr. Milei’s violent election campaign, which has included insulting the pope, openly insulting women journalists, and calling for liberalized gun ownership laws, marks the arrival of a contemporary far-right discourse familiar in neighboring Brazil but hitherto unknown on the Argentine political scene.

This, she believes, seems likely to persist. But despite voters’ frustration at the government’s failure to solve their economic and social problems, most are still unwilling to seek salvation in Mr. Milei’s extremism. “While Milei got 30% of the vote, 70% went to other parties,” Ms. Goyburu points out. “People are not going for these really argumentative discourses ... questioning democracy as a system.”

Why a striking UAW is so public about wanting more

The United Auto Workers union has gotten big concessions in its strike so far. Yet it’s demanding more – and publicly, rather than behind closed doors. Experts say it’s to impress nonunion autoworkers and win them over.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Contract talks between the United Auto Workers union and the three major U.S. automakers are more public than ever this year. It’s part of the union’s high-stakes strategy to win a contract so good that hundreds of thousands of nonunion autoworkers will sit up and take notice.

If the union succeeds, it could convince many of those nonunion workers to join their ranks.

“You kind of want to be with the winner,” says professor Tod Rutherford, who studies labor and the auto industry at Syracuse University.

For decades, unions have been seen on the losing side of collective bargaining, either giving concessions at contract time or losing members. “If unions are now seen to be relevant actors and also ones that are winning good contracts for their membership, then that has a knock-on effect. It gives them greater credibility to start being able to unionize the Teslas and some of these other [nonunion] plants,” Dr. Rutherford says.

This helps explain the hard line that the leadership of the United Auto Workers union has maintained, despite substantial progress at the bargaining table. It’s part negotiating strategy, part theater.

Why a striking UAW is so public about wanting more

Contract talks between the United Auto Workers union and the three major U.S. automakers are more public than ever this year. It’s part of the union’s high-stakes strategy to win a contract so good that hundreds of thousands of nonunion autoworkers will sit up and take notice.

If the union succeeds, it could convince many of those nonunion workers to join their ranks.

“You kind of want to be with the winner,” says professor Tod Rutherford, who studies labor and the auto industry at Syracuse University.

For decades, unions have been seen on the losing side of collective bargaining, either giving concessions at contract time or losing members. “If unions are now seen to be relevant actors and also ones that are winning good contracts for their membership, then that has a knock-on effect. It gives them greater credibility to start being able to unionize the Teslas and some of these other [nonunion] plants,” Dr. Rutherford says.

This helps explain the hard line that the leadership of the United Auto Workers union (UAW) has maintained, despite substantial progress at the bargaining table. It’s part negotiating strategy, part theater.

“The union is using the public,” says Toby Higbie, professor of history and labor studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. “It’s taking its case to the public in the way that the UAW did in the 1930s and ’40s and ’50s, when they made big demands, made those demands very public, and tied their UAW demands to the broader aspirations of other working people.”

After a flurry of activity late last week, for example, when the UAW announced that all three automakers had agreed to a 23% pay increase for workers over four years, union president Shawn Fain made a speech on Facebook, saying there was “still room to move” and took Ford to task for “pretending” that there wasn’t.

Such blunt talk can overshadow the union’s strategic approach to the strike, which it has gradually expanded by staging walkouts at specific plants to goad automakers to make concessions. On Monday, for example, the UAW expanded its strike to include Stellantis’ Sterling Heights, Michigan, plant, where the automaker assembles its hugely profitable Ram pickups. And on Tuesday, it struck the Arlington, Texas, plant that makes General Motors’ highly profitable full-size SUVs.

“There’s been progress, but progress is uneven and Stellantis probably lags behind the others,” especially on core issues, says Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit who has written extensively on the history of the UAW. Those core issues include a cost-of-living allowance to protect workers from inflation, the speed at which lower-tier pay for newer union workers will be eliminated, and the conversion of temporary employees to full-time workers.

The challenge in bargaining simultaneously with all three automakers is that they may want different things while the union is going to push for uniformity, he adds. General Motors, for example, has made the huge concession – according to the union, anyway – that workers at its joint-venture battery plants would be covered by the UAW contract. That move would ensure the union would retain its leverage as the automakers move to electric vehicles. Ford and Stellantis, however, are not known to be ready to accept such a proposal.

The talks are complicated by the fact that the companies face an uncertain future. The move to electric vehicles is proving costly and there are growing concerns that consumers may not embrace them as quickly as automakers had planned. The strike itself is adding to those uncertainties.

On Tuesday, GM withdrew its forecast – or guidance – for its financial performance this year, in part because of the strike. In announcing better-than-expected $3.1 billion quarterly earnings, the company said the walkouts cost it $200 million in the third quarter and another $200 million per week so far in the fourth quarter. Ford will report its quarterly earnings on Thursday.

Although the hardline union rhetoric combined with the companies touting strike-related losses may suggest an impasse, many analysts say this sort of posturing is typical of the final stage of bargaining before an agreement.

“The UAW strategy is working,” says Susan Schurman, professor of labor studies and employment relations at Rutgers University. But “you have to have an end game. You have to know when enough is enough and trying to go further is going to create more downsides than upsides.”

“These negotiations are at a critical juncture,” agrees Thomas Kochan, emeritus management professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Financial pressures are rising for the companies and the union risks undercutting its broader appeal, he says, adding, “If the strike expands and goes on for a much longer time, it may cause nonunion workers to pause and ask: ‘Is this something we are prepared to endure?’”

Books

Courage, justice: Our favorite October reads

Where do we begin in a search for justice? In this month’s books roundup, characters and authors wrestle with this question as they navigate everything from spy craft to incarceration.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Monitor contributors

The meaning of justice can often feel impossible to crack. In prescient and engaging books, both fiction and nonfiction, authors weave moving narratives as their characters struggle against inequity.

In nonfiction, journalist Eva Fedderly makes a compelling debut with “These Walls,” which focuses on New York’s notorious Rikers Island jail complex, which is scheduled to be replaced with smaller institutions. She deftly considers the history and future of incarceration, and interviews people trying to design more humane jails, as well as prison abolitionists and incarcerated individuals.

And in fiction, Tananarive Due’s harrowing speculative thriller “The Reformatory” tells the story of Robert, who, for trumped-up reasons, is held in a segregated reform school for boys. Robert navigates sadistic administrators and ruthless peers while his sister races to free him from an institution known for abusing its students – particularly its Black ones.

Striking and engaging, these works pull vital lessons from difficult stories.

Courage, justice: Our favorite October reads

1 The Berry Pickers

by Amanda Peters

After their youngest daughter, Ruthie, vanishes during a summer of berry-picking in Maine, a Micmac family from Nova Scotia struggles to move forward. Indigenous Voices Award winner Amanda Peters delivers an un-put-down-able novel of identity, forgiveness, and insistent hope.

2 Tremor

by Teju Cole

Tunde, a Nigerian professor living in the United States, grounds Teju Cole’s novel of ideas, moods, views, and questions. A trip to Lagos amplifies a chorus of other voices; they’re quirky and ordinary, sometimes profane, always human. The result is probing – and often revelatory.

3 Beirut Station

by Paul Vidich

Lebanese American CIA agent Analise Assad joins a plot to assassinate a deadly terrorist holed up in Beirut in 2006. She and her partners – a Mossad agent, an old CIA hand, and a journalist – plan and parry. This well-plotted thriller deftly mixes spy craft with questions about identity and justice.

4 The House of Doors

by Tan Twan Eng

This atmospheric novel, set in 1920s Malaysia, tells of a famous author bent on uncovering secrets for storytelling fodder. Tan Twan Eng weaves love, duty, betrayal, colonialism, and redemption into the narrative.

5 The Other Princess

by Denny S. Bryce

A young Black African princess who was orphaned, kidnapped, and enslaved by a rival king goes on to become the goddaughter of Queen Victoria in England. Denny S. Bryce honors the life of the real Sarah Forbes Bonetta with meticulous storytelling, not shying away from the racism and oppression that Sarah encounters.

6 The Reformatory

by Tananarive Due

Tananarive Due’s harrowing speculative thriller – an homage to a family member’s experiences at the notorious Dozier School for Boys – tracks Black siblings as they search for safety and justice in 1950s Florida. Imprisoned in a brutal reform school on cooked-up charges, 12-year-old Robert must survive sadistic administrators, ruthless peers, and specters both benign and tormented, while his sister races to free him. Horrors abound; fortitude wins.

7 The Soul of Civility

by Alexandra Hudson

What can the world’s oldest book teach us about civility today? Alexandra Hudson’s thoughtful and eloquent treatise on how to live well together draws on literature from “The Teachings of Ptahhotep,” written 4,500 years ago in Egypt, to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

8 These Walls

by Eva Fedderly

Journalist Eva Fedderly’s compelling debut focuses on New York’s infamous Rikers Island jail complex, which is slated to be replaced by smaller penal institutions throughout the city. Using this initiative to consider both the history and future of incarceration, she profiles “justice architects” who design humane jails, prison abolitionists, and individuals who are incarcerated.

9 How To Say Babylon

by Safiya Sinclair

Acclaimed poet Safiya Sinclair’s searing and lyrical memoir describes her upbringing in Jamaica in a strict Rastafarian household ruled by her autocratic father. As his dreams of reggae stardom wither, he becomes increasingly rigid and violent; through poetry, she imagines a different life for herself.

10 Dwell Time

by Rosa Lowinger

In this inventive and engaging work, art conservator Rosa Lowinger considers how her professional expertise in repairing damage can be applied to life as well as to art. She traces her Jewish Cuban family’s history, including losses reaching back to the Holocaust and the Cuban Revolution, seeking to understand and to heal intergenerational trauma.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Mutual goals for Israelis, Palestinians

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Israel’s military operations in the Gaza Strip have raised urgent questions about what comes next if it succeeds in eradicating Hamas, the militant group that has governed the Palestinian enclave since 2006. Few see long-term Israeli administration as either viable or acceptable to the region’s Arab leaders. The answer may lie in an alignment of Israel’s security interests with the aspirations of Palestinians for honest and democratic governance.

That shift would be the most consequential outcome of the current conflict – and it has arguably already happened. The deadly Oct. 7 assault by Hamas on Israeli villages adjacent to Gaza undermined Israeli assumptions that the country’s safety depended on keeping Palestinian leadership divided and off balance.

Israeli and Palestinian civil society groups agree there is a basis for unity in shared values. Prior to the crisis over Gaza, the two societies were involved in separate, parallel struggles to preserve or restore their respective democracies. Yet they also have two common aims: to ensure judicial independence and uproot corruption. Increasingly, people on both sides see those movements not so much as parallel but as intertwined.

Mutual goals for Israelis, Palestinians

Israel’s military operations in the Gaza Strip have raised urgent questions about what comes next if it succeeds in eradicating Hamas, the militant group that has governed the Palestinian enclave since 2006. Few see long-term Israeli administration as either viable or acceptable to the region’s Arab leaders.

The answer may lie in an alignment of Israel’s security interests with the aspirations of Palestinians for honest and democratic governance.

That shift would be the most consequential outcome of the current conflict – and it has arguably already happened. The deadly Oct. 7 assault by Hamas on Israeli villages adjacent to Gaza undermined Israeli assumptions that the country’s safety depended on keeping Palestinian leadership divided and off balance.

“This entire strategy has one goal,” Noa Shusterman Dvir, an Israeli national security consultant, told The New York Times. “Weakening the Palestinian Authority and strengthening Hamas is designed to hinder peace efforts, to prevent the establishment of a Palestinian State.” Now, she said, “the concept of ‘managing the conflict’ is broken.”

Gaza and the Palestinian territories in the West Bank have been under divided leadership for nearly two decades. Attempts to reconcile and unify the separate governing factions have repeatedly failed. The last Palestinian elections were held in 2006. Since then, Palestinians have become increasingly discontent over corruption and lack of economic opportunity.

Those frustrations have erupted repeatedly before and since the Hamas attacks – particularly in the West Bank. Palestinians blame the Palestinian Authority, their main governing body, of failing to protect them, especially as attacks by Israeli settlers on Palestinians have increased in the West Bank.

A September report by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research found that Palestinians attribute their declining trust in their leaders to their financial dependency on Israel. That has exacerbated other grievances. The center also found that Palestinians strongly admired the mass demonstrations by Israelis against their government’s attempts to weaken judicial independence.

Those attitudes point to common cause. Israeli and Palestinian civil society groups agree there is a basis for unity in shared values. Prior to the crisis over Gaza, the two societies were involved in separate, parallel struggles to preserve or restore their respective democracies. Yet they also have two common aims: to ensure judicial independence and uproot corruption. Increasingly, people on both sides see those movements not so much as parallel but as intertwined.

As Shir Nosatzki, an Israeli activist, noted late last month, if the Israeli “protest movement builds a new agenda while Arab society is not sitting at the table, we won’t be able to call whatever it is we are building ‘democracy.’ I do think that the fact that Israeli Jews are starting to talk about what democracy is, has to bring us towards the fact that we are occupying another [people’s land].”

The hostilities in Gaza have deepened a crisis of confidence among Israelis and Palestinians in their leaders. They may be seeing similar paths toward restoring that trust.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Praying when there’s conflict

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

As we keep alert to news of hostilities, we can contribute a healing influence by recognizing that the only valid power and presence is God, who is entirely good.

Praying when there’s conflict

Between each bit of news about war, is there room to think? To pray? It’s always important to keep up to date on the news, yet we also need to take time to step back from the jarring details. I’ve found that, in order to rise above the cycles of dismal reports of doom that may run through my head, I need to be still and pray. Prayer isn’t something to hide behind; prayer lifts my thought beyond what I see physically and brings to light the goodness and allness of God.

So lately, I’ve carved out time to consider the simple fact that God is good and, as Jesus proved in his life and healings, God is always completely good. As explained in Mary Baker Eddy’s textbook on the Christ-healing practiced by Jesus, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “In the Saxon and twenty other tongues good is the term for God. The Scriptures declare all that He made to be good, like Himself, – good in Principle and in idea. Therefore the spiritual universe is good, and reflects God as He is” (p. 286).

As I study more about the nature of God, I am emboldened to learn how God’s spiritual universe is the one and only universe. In the final analysis, since we live in a universe of God, we live in a universe of good, in which we, too, are spiritual and good, despite how things may appear. In contrast with today’s cacophony of discouragement and violence, this is such heartening news.

Recognizing this opens our eyes to God’s presence as tangible. No matter what we are facing, God is with us, guiding both what we think and what we experience.

As a child, I remember being bullied and beaten one day by an older student. But I found that what I’d been learning in my Christian Science Sunday School class – and what I had put into practice outside of it – kicked in. Rather than feeling afraid or angry, my whole heart overflowed with a palpable awareness of God’s love – both for myself and the other student. Later, this individual looked right into my eyes and apologized, and I found that I didn’t even need to forgive him – I already had.

To stop, be still, and behold the fact that God is always present and solely good shows us the harmony that’s really going on. As we go forward into each day, we all actually remain within the ever-present realm of divine Love, which isn’t just semi-powerful; Love is omnipotent, all-powerful. We can pray to see how, in full authority, Love rules every scene, every moment, everyone. God’s goodness is actually measureless – it never comes to a conclusion.

Even before we commence praying, God’s goodness is infinite and ever present. At a time when violence was prevalent, an individual in the Bible prayed with joy, “Oh that men would praise the Lord for his goodness, and for his wonderful works to the children of men!” (Psalms 107:8). It’s helpful to pause and praise God in that way.

God deeply loves the goodness He sees reflected in each of us as His spiritual offspring. In fact, God says this about His children: “They shall be as the stones of a crown, lifted up as an ensign upon [God’s] land” (Zechariah 9:16). From God’s perspective, each of us, in our reflected, divine perfection, is like a jewel in a crown.

Just consider that! God truly loves us beyond measure. And God’s love and goodness correct whatever doesn’t align with this true view of ourselves and others, and they guide us.

We are basking in God’s love, being strengthened in it, being steered by it, being kept whole as a result of it. Jesus proved this when a violent mob attempted to kill him: “But he passing through the midst of them went his way” (Luke 4:30).

Despite reports coming across our screens about the delicate state of world unity, prayer reveals that, in God’s love, all we possess is goodness that comes from God. Our very existence not only depends on, but is made to represent, God’s love.

It matters for the world that we know deeply and solidly that God, divine Love, and God’s creation are good – and good only. The way to move forward is to be consistently conscious of God’s presence and love, here and now. As we pray in this way, we can be comforted to know that our quiet efforts are contributing greatly to the healing of conflict around the world.

Interested in reading inspiration shared by some of the countless individuals praying about the Israel-Hamas war? Check out “How I’m praying about the Israel-Hamas war...” on sentinel.christianscience.com.

Viewfinder

Stone mail

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. We hope you’ll also check out this story about the impact of artificial intelligence on math and computer science classes. The piece is the final installment of The Math Problem, a collaborative series documenting challenges and highlighting progress.