- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Learning to have conversations

Ira Porter

Ira Porter

In the midst of a war between Israel and Hamas, American universities are witnessing extreme words and actions on campus – sometimes escalating into violence. At Columbia University, an Israeli student was beaten with a stick for hanging pro-Israel posters. At Harvard, pro-Palestinian students who wrote a social post were doxxed, which threatened their safety.

College students, faculty, and administrators have opinions on many hot-button issues, of course, and there are always disagreements. Debates over free speech are in high gear. But the highlight of studying at university is discovering new ideas, opening your mind to different ways of thinking – and learning how to communicate complex and competing views effectively. That can include protests and bullhorns. But it can also include sincere conversations that may not yield agreement, but at least demonstrate an ability to listen to one another.

As the Monitor’s higher education reporter, I have seen colleges trying to bridge the gap. Fordham University’s department of campus ministry, for example, organized an interfaith prayer service to bring different religious groups together. Manhattan College’s Interfaith Education Center did something similar. In lecture halls and online, universities are deploying professors to explain the complex history of the conflict to community members, giving them better tools to work with as they grapple with what’s happening.

In the coming weeks and months, the hope is that there will be more of this. College is where people go to figure things out, where some find their voice. These attempts at bridging the gap at universities show that students of different backgrounds and viewpoints can still be friends and see the humanity in each other. As more schools show up and prove that they can be thought leaders and facilitators of beneficial conversations, the true value of higher education will be on display.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How Mike Johnson went from ‘who?’ to House speaker

After a historic impasse, House Republicans Wednesday selected a new speaker, Mike Johnson of Louisiana. He is inexperienced in leadership and faces divisive and difficult issues – but he has the unanimous backing of his GOP colleagues.

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

After three tumultuous weeks of stalemate and infighting, House Republicans ended their speakership saga Wednesday by elevating a relatively junior member with strong conservative bona fides, an amiable demeanor – and perhaps most important, few enemies.

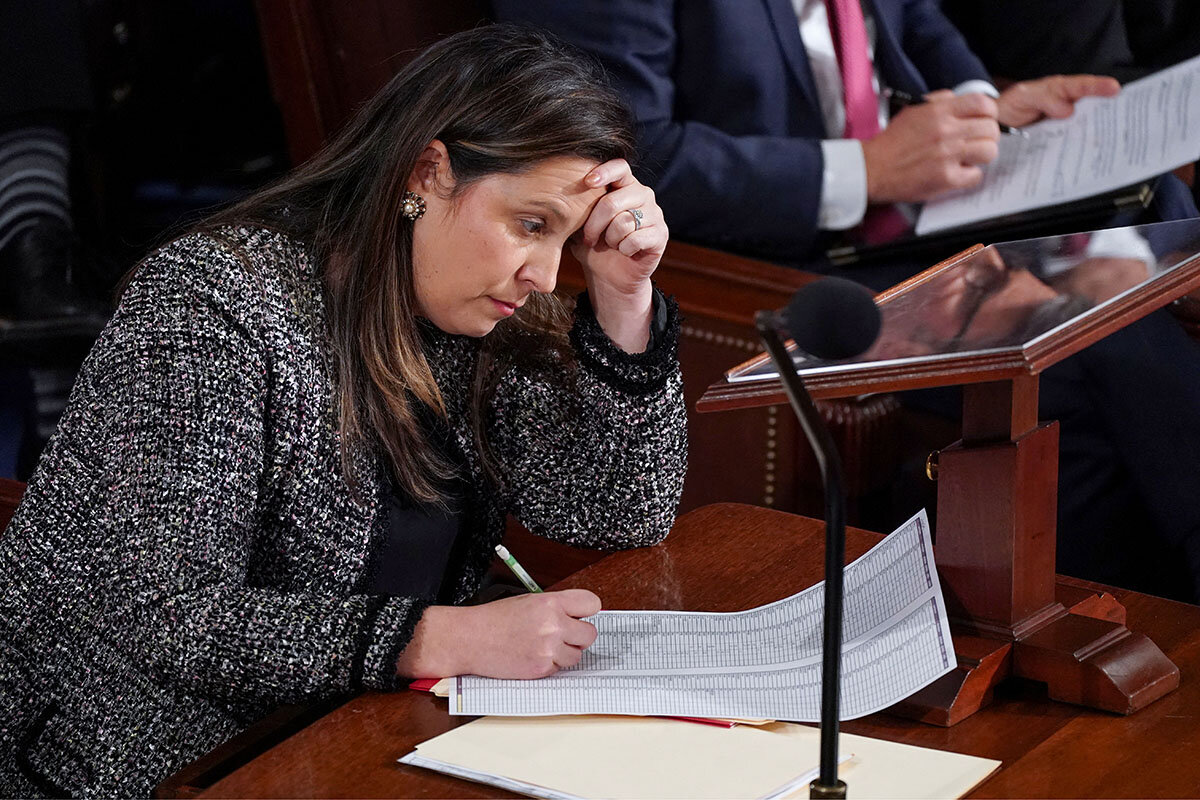

Louisiana Rep. Mike Johnson, now in his fourth term, is the least experienced member to become House speaker in more than 80 years. He was elected after a historic impasse in which three other GOP nominees tried and failed to win the gavel. His selection came with both a sense of relief and trepidation.

The new speaker, who stands second in line to the presidency after the vice president, will immediately have to contend with a series of divisive and difficult issues. They include a Nov. 17 deadline for funding the government and aid packages for Ukraine and Israel.

While Republicans rallied around the bespectacled Louisianian, who won unanimous support from his party, Mr. Johnson begins his speakership in a markedly weak position. With no leadership experience and no real relationships with his counterparts in the House and Senate, he will be trying to secure conservative policy goals from an exceedingly narrow and bitterly divided House GOP majority, while negotiating with a Democratic Senate and White House.

But at least for now, the right-wing members who took down former Speaker Kevin McCarthy are behind him.

How Mike Johnson went from ‘who?’ to House speaker

After three tumultuous weeks of stalemate and infighting, House Republicans ended their speakership saga Wednesday by elevating a relatively junior member with strong conservative bona fides, an amiable demeanor – and perhaps most important, few enemies.

Louisiana Rep. Mike Johnson, now in his fourth term, is the least experienced member to become House speaker in more than 80 years. His election, after a historic impasse in which three other GOP nominees tried and failed to win the gavel, came with both a sense of relief and trepidation. The new speaker, who stands second in line to the presidency after the vice president, will immediately have to contend with a series of divisive and difficult issues. They include a Nov. 17 deadline for funding the government and aid packages for Ukraine and Israel.

While Republicans rallied around the bespectacled Louisianian, who won unanimous support from his party, Mr. Johnson begins his speakership in a markedly weak position. With no leadership experience and no real relationships with his counterparts in the House and Senate, he will be trying to secure conservative policy goals from an exceedingly narrow and bitterly divided House GOP majority, while negotiating with a Democratic Senate and White House.

For now, at least, some of the right-wing members who sparred with former Speaker Kevin McCarthy over spending and other matters before his historic ouster on Oct. 3 indicated they would give Speaker Johnson the benefit of the doubt as he gets his feet under him.

“You don’t blame the backup quarterback for the failures of the guy that just came out of the game,” Scott Perry, chair of the hard-line Freedom Caucus, told reporters ahead of the vote.

Mr. Johnson laid out an ambitious plan for accomplishing one of conservatives’ top priorities: passing all 12 appropriations bills, a process that has gotten logjammed more often than not in recent years. The goal is to avoid a massive “omnibus” spending bill that gives members little time to read what they’re funding or weigh in on funding levels for specific departments.

“I am confident we can accomplish that objective quickly, in a manner that delivers on our principled commitment to rein in wasteful spending, and put our country back on a path to fiscal responsibility,” wrote Mr. Johnson in a two-page memo to colleagues.

According to his proposed timetable, the House would vote on the remaining eight bills by the Nov. 17 deadline, or extend funding temporarily to January or April in order to complete the process. That, he said, would give the House the upper hand in negotiations with the Democratic-led Senate and avoid a Christmas omnibus.

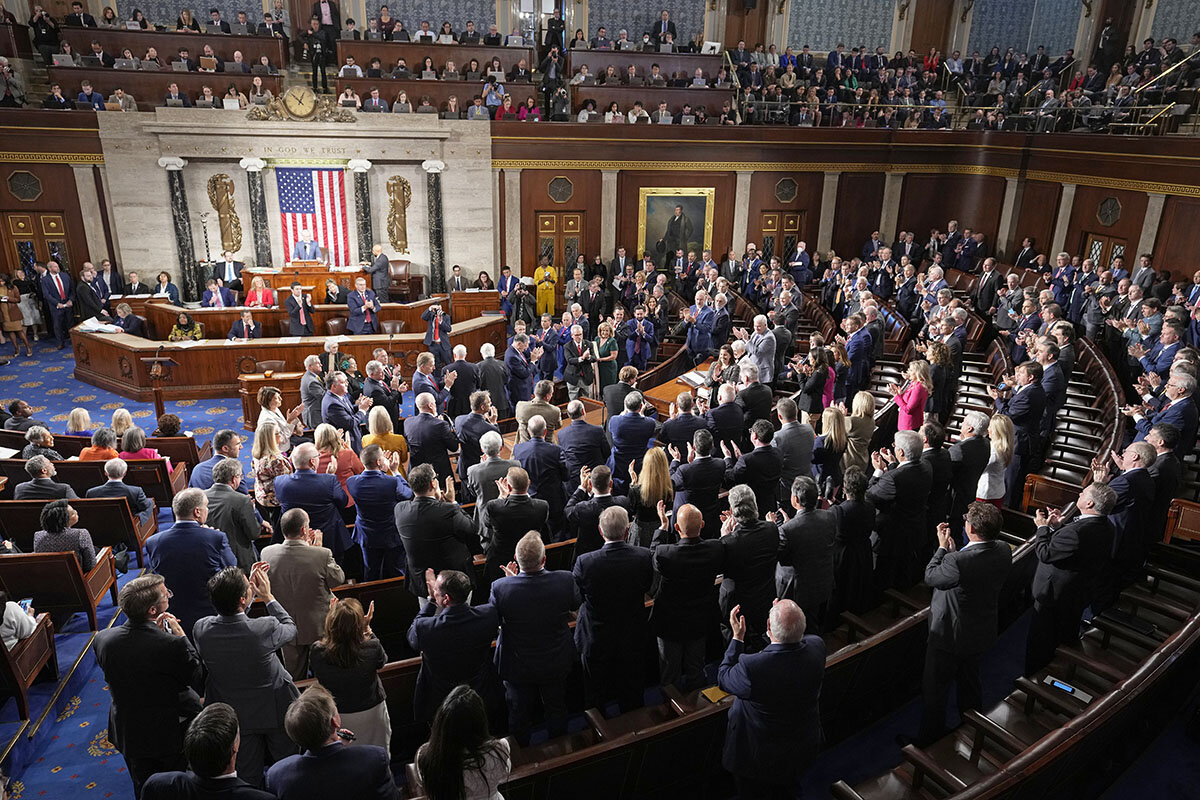

Mr. Johnson is known for his genial manner. Upon his election, he started his remarks by acknowledging the contributions of overworked House staffers, the families of members of Congress, and former Speaker McCarthy. He also extended an olive branch to Democratic Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries.

“I know that in your heart you love and care about this country and you want to do what’s right. We are going to find common ground there,” he said, receiving a standing ovation from both sides of the aisle.

Why everyone has to Google “Mike Johnson”

Despite serving as head of the conservative congressional Republican Study Committee, and vice chair of the GOP conference, Mr. Johnson was so little known that even prominent Republicans like Sen. Susan Collins told reporters they would have to Google him.

A southern Baptist and constitutional lawyer, he had long worked in support of conservative policy positions on abortion and same-sex marriage. He is seen as more of a policy wonk in the mold of former Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan. Among the eight other candidates for speaker in the second-to-last round, Mr. Johnson had sponsored 46 bills, and had the highest share of sponsored legislation passed out of committee. However, only a few of his bills had Democratic co-sponsors, resulting in just 13% passing out of the House.

Among the more controversial pieces of legislation he sponsored was the Stop Sexualization of Children Act of 2022, which critics dubbed a federal version of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law – but with expanded scope. The bill proposed limiting federal funding of sex education to children age 10 and older, noting that some school districts had introduced sex education for children as young as kindergarten that included discussions of gender identity.

Mr. Johnson is also controversial for his work limiting abortion access, which has earned him an A-plus rating from Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America. In 2019, he joined 177 colleagues in co-sponsoring a bill prohibiting abortion nationwide after 20 weeks.

Amicus brief to overturn 2020 election

But the issue Democrats and other critics highlighted most prominently was Mr. Johnson’s role in challenging the results of the 2020 election, calling him an “election denier.” The constitutional lawyer, educated at Louisiana State University, spearheaded an amicus brief signed by 126 House Republicans in support of a case against four swing states, brought by the Texas attorney general.

The case alleged that the sweeping electoral changes those states enacted in the run-up to the 2020 election circumvented the constitutionally designated role of state legislatures. The Supreme Court threw out the case, saying Texas did not have standing to bring it.

Even if the case was brought by a state with standing, “it would still lack merit,” says Edward Foley, a constitutional law professor at The Ohio State University. For example, in lower courts there were “definitive rulings rejecting the claims that there was any basis for overturning the certification of the election in favor of President Biden in Pennsylvania,” one of the four swing states involved.

Even those who say that some of the arguments may have had merit say that such electoral changes would have had to have been challenged prior to Election Day; otherwise, voters would be unfairly disenfranchised.

“The time to bring most of these objections would have been before the election, while the violation was occurring – before all of the votes were accepted and tallied, rather than after the fact in terms of trying to change your election results,” says Michael Morley, a professor at Florida State University College of Law who is known for his work on post-election litigation.

Moreover, adds Professor Foley, there were not enough ballots in question to have overturned the election in Pennsylvania alone – and it would have taken at least three states to undo Mr. Biden’s election.

Mr. Johnson, who at the time also raised other concerns about the 2020 election, including the now-debunked issue of voting machines from Venezuela, did not address 2020 election concerns in his speech on the House floor today. But in a lengthy interview with The New Yorker in December 2020, he said that if such legal challenges failed, “and Joe Biden is the President, then what we do in America is work for the next election cycle” – something he outlined on his timeline for House GOP activity over the next year.

Warning to world’s “enemies of freedom”

In remarks before the full House on Wednesday, the newly elected speaker described himself as the son of a firefighter and the first in his family to graduate from college. He spoke of his conviction – rooted in his faith – that all of his fellow lawmakers have been “ordained” by God to serve the country at this critical time.

“A strong America is good for the entire world,” he said in his maiden speech, which received several bipartisan standing ovations. “We are the beacon of freedom and we must preserve this grand experiment in self-governance.”

He called America’s record debt its No. 1 national security issue, and called for a bipartisan debt commission to begin work immediately.

Last, Speaker Johnson addressed the world, which he noted had been watching this drama unfold over the past few weeks.

“We want our allies around the world to know that this body of lawmakers is reporting again to our duty stations,” he said. “Let the enemies of freedom around the world hear us loud and clear: The people’s House is back in business.”

Indeed, within an hour, Chairman Michael McCaul of the House Foreign Affairs Committee was on the floor introducing his resolution supporting Israel in “defend[ing] itself against the barbaric war launched by Hamas and other terrorists.“ The resolution passed 412-10.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to more accurately describe the McCaul resolution on Israel.

Gaza crisis: Iran pivots to preventing losses

Since the Hamas-Israel war erupted, Iran and its other regional allies have been arrayed against Israel and the United States, which has deployed forces. Iran’s balancing act now is to preserve what it has gained, without the costs of a wider war.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

An Oct. 18 broadcast on Iranian television shows every arm of Iran’s anti-U.S. and anti-Israel alliance using Iranian missiles and rockets to attack and swarm Israel. The portrayed offensive would build on the surprise Oct. 7 incursion by Iran-backed Hamas, which stunned Israel with its brutality.

The message aimed to deter Israel, which has massed its forces for a ground invasion of the Gaza Strip and has pledged to “destroy” Hamas in Gaza – a result Iran says is unacceptable.

While the Iranian broadcast seeks to project a sense of military readiness, it is only one side of Iran’s balancing act.

For even as Iran aims to continue hurting Israel with the calibrated use of its regional militia allies, it also seeks to avoid a regional war, which could reel in Hezbollah, Iran itself, and the United States – and jeopardize the deterrent power of Iran’s regional alliance.

Critical to Iran’s calculations may also be ensuring the survival of Hamas or risking appearing weak.

“The big achievement is there. ... You don’t need more,” says Hassan Ahmadian, an assistant professor at the University of Tehran. “But you also need to make sure that your allies are there, survive, and can continue. As the main party that supports Hamas, and others in the region, your credibility is also at stake – you can’t just turn a blind eye.”

Gaza crisis: Iran pivots to preventing losses

Iran’s stark warning to Israel about triggering a wider regional war – with Iran-allied militias attacking on three fronts, if Israel continues bombarding Gaza – came in the form of a special report on Iranian state-run television.

The Oct. 18 TV broadcast shows every arm of Iran’s anti-U.S. and anti-Israel alliance using Iranian missiles and rockets to attack and swarm Israel. The portrayed offensive would build on the surprise Oct. 7 incursion by Iran-backed Hamas, which stunned Israel with its savagery, and left 1,400 Israelis dead and more than 200 as hostages.

More than 6,000 people have since been killed in Gaza, Palestinian officials say, amid relentless Israeli airstrikes and shelling that have displaced hundreds of thousands of civilians. Israel has massed its forces for a ground invasion, and Israeli officials say it will “destroy” Hamas in Gaza – a result Iran says is unacceptable.

The Iranian broadcast intersperses scenes of carnage in Gaza with missile launches and shows Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, warning in a speech that Iran-backed fighters will “become restless” and “nobody will be able to stop them” if Israel does not stop its “crimes” in Gaza.

“If the Resistance Front loses patience and decides to take action against the Zionist regime, it will do so from as far away as 2,000 kilometers,” says the narrator on Iran’s state-run IRINN. Red arrows show Iran-backed Hezbollah targeting Israel from Lebanon in the north, Syrian and Iraqi militia from the east, and Houthis from Yemen from the south.

The graphic shows explosions rising repeatedly from Israel, which is depicted as a broken Star of David.

While the Iranian broadcast and state-run newspapers seek to capitalize on high emotions in Iran over Gaza and project a sense of readiness with headlines such as “Impatience for the Zero Hour,” it is only one side of Iran’s careful balancing act.

For even as Iran aims to continue hurting its archfoes Israel and America with the calibrated use of its regional militia allies, it also seeks to avoid an all-out regional war. Such a conflict could reel in Hezbollah, Iran itself, and the United States – and jeopardize the deterrent power of Iran’s regional alliance, its self-declared “Axis of Resistance.”

Analysts say Iran relishes what it terms Hamas’ “achievement” against Israel, and while Iran was instrumental in enabling the audacious Hamas attack – with cash, smuggled weapons parts, and shared asymmetric military know-how – Ayatollah Khamenei was also quick to deny any direct Iranian role in the assault.

Yet critical to Iran’s calculations may also be ensuring the survival of Hamas or risking appearing weak.

“The big achievement is there, which is rebalancing vis-a-vis Israel through more effective deterrence; you don’t need more,” says Hassan Ahmadian, an assistant professor at the University of Tehran. “But you also need to make sure that your allies are there, survive, and can continue. As the main party that supports Hamas, and others in the region, your credibility is also at stake – you can’t just turn a blind eye.”

Iranian “pushback”

For years, Iran had felt that Israel had been “inching closer to Iran, so a pushback against that and rebalance was expected,” says Dr. Ahmadian, noting growing Israeli influence in Iraqi Kurdistan and neighboring Azerbaijan, as well as Israeli actions targeting Iran – from Syria to inside Iran itself.

“Hamas’ priorities came in line with Iran’s interests. They called the shot, but the Iranians were happy about it; this is what they were after,” says Dr. Ahmadian. “The Iranians feel that consolidating the balance has already been achieved. In line with this, Iran’s allies should be saved as well.”

That is one reason Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian warned the U.S. Monday to “stop the war before it is too late” in a region that could “spiral out of control any minute.”

“The lines drawn in Tehran and in Beirut [by Hezbollah] are clear that [Israel’s] moving into Gaza would spark a major conflict, which means Hezbollah moving heavier toward a collision course with Israeli forces – not necessarily waging total war, but increasing the heat there,” says Dr. Ahmadian.

“The most visible scenario for me is that Hezbollah would increase the heat to a level that makes Israel really revisit its strategy against Gaza – then you could see attacks also from Syria, Iraq, and maybe from Yemen,” he says.

Already, Israel’s northern border with Lebanon has been rocked by multiple skirmishes with Hezbollah and led to the evacuation of Israeli civilians from the border region. U.S. troops on bases in Iraq and Syria have come under rocket fire and drone attack from Iranian-backed groups.

U.S. messages and maneuvers

The U.S. has promised Israel unwavering support in its response to the Hamas attack and has sent forces to the region, but it has also counseled Israel to delay its ground offensive to allow for the delivery of more humanitarian aid, the release of more hostages, and the deployment of key U.S. military units, including missile defenses.

A U.S. Navy destroyer in the northern Red Sea and a missile battery on Saudi soil last week shot down four cruise missiles and 15 drones that were launched by Houthis in Yemen and apparently aimed at Israel.

On Oct. 13, Secretary of State Antony Blinken delivered a message to Iran via Qatar that the U.S. did not want a wider war, and that Iran and Hezbollah “must exercise restraint.”

Yet on Sunday, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin cited “recent escalations by Iran and its proxy forces” across the Middle East when he ordered a second aircraft carrier strike group that was en route to the eastern Mediterranean and redirected to an area closer to Iran.

“Iran doesn’t have the desire to enter into a broader conflict itself, and most probably it also doesn’t want to see Hezbollah comprehensively involved in that,” says Hamidreza Azizi, an Iran expert at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin.

“In the eyes of Iranian leaders, what they could possibly achieve against Israel has already been achieved as a result of this Hamas attack,” says Dr. Azizi. “They have been under criticism by their own support base ... for not showing enough strength in the face of Israeli covert actions inside Iran, in Syria, and Iraq.”

He cites assassinations widely attributed to Israel of a number of key nuclear scientists and a top missile specialist, sabotage of Iran’s nuclear facilities by Mossad operatives, and frequent airstrikes against Iranian and allied militia targets in Syria and Iraq.

“Those ultra-hard-liners, who form the only support base left for the Islamic Republic, were getting more and more unhappy with the trend,” he says. “Now, after all these years of propaganda – and of course there is some reality in that – about this unified front supported by Iran, they can claim that they have already taken revenge for Israeli actions.”

For Iran, the “most desirable” outcome now is for clashes to stop and the status quo to remain, says Dr. Azizi. “Iran would not have a problem with a cease-fire because the damage [to Israel] is done already, and the so-called Resistance forces will have enough time to regroup and plan for the next phase.”

There are also significant domestic issues at play for Iran, such as an economy crippled by U.S.-led sanctions and government mismanagement, and deep unhappiness with the Islamic Republic, as expressed by months of women-led street protests that began last year.

The chant is often heard at protests: “Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, I sacrifice my life for Iran.”

Khamenei’s legacy

Avoiding a regional war may also be a personal issue for the octogenarian Ayatollah Khamenei, says Dr. Azizi.

“Khamenei obviously doesn’t want ... to be remembered for bringing the country into war and devastation,” he says. “All the other actors involved in the post-Khamenei transition do not want this process to be disrupted, or war to contribute to domestic unrest, and the situation to get out of hand.”

The challenge for Iran is made deeper by its recent outreach to Arab nations, which included reestablishing ties last spring after seven years with Saudi Arabia. A year of indirect negotiations with the U.S., brokered by Qatar, led to a prisoner exchange in mid-September.

Reports at the time indicated a further agreement for the U.S. to ease enforcement of sanctions, if Iran slowed down progress on its nuclear program and tempered the attacks by its allied regional militias.

“We are in contact with our friends Hamas, Islamic jihad, and Hezbollah,” the head of Iran’s parliamentary National Security Committee, Vahid Jalalzadeh, said last week. “Their stance is that they do not expect us to carry out military operations.”

An Iranian researcher contributed to this report.

As corruption costs lives, Ukrainians demand change

For many Ukrainians, the war they are currently fighting involves two foes. One is Russia. The other is their country’s chronic corruption, which can be deadly. But while war usually grows corruption, Ukraine is making headway against it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Tolerance for corruption has waned in Ukraine. With so many lives at stake amid the war with Russia, national and local spending priorities are under the magnifying glass.

This year started with corruption scandals related to war profiteering, including purchases of eggs and generators at well above their expected costs. In August, investigators revealed purchases of overpriced winter jackets and schemes to avoid military conscription.

This spurred the removal of the entire top brass of the Ministry of Defense, including the minister himself, as well as all the country’s regional recruitment heads. In recent months, anti-corruption protests have been held across Ukraine.

“Society became very intolerant towards any defense-related corruption,” says Olena Trehub, executive director of the Independent Anti-Corruption Commission. “People of course are much more sensitive to this particular matter.”

Ironically, Ukraine is improving its dismal corruption ranking in spite of the war. Though only 116 out of 180 in the 2022 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, Ukraine jumped up six spots from 2021.

“Countries in wartime conditions drop their score. We as Ukraine improved our score,” says Oleksandr Kalitenko, legal adviser at the Kyiv office of Transparency International. “We have the best score of the last 10 years.”

As corruption costs lives, Ukrainians demand change

Clad in black, Iryna Olyanska welcomes mourners to a memorial service for her only son, Artem, being held at a local restaurant 40 days after his death. He was shot by Russians while fighting on the front lines near Kupiansk. And Ms. Olyanska is angry.

Not just at the Russians, but also at the corruption that has beset defense procurement since the start of the war, with deadly consequences for men like Artem fighting for Ukraine.

There are many elements to her anger. Artem’s commander later told her that their unit had advanced behind enemy lines, but lacked a drone to support their mission with aerial reconnaissance. Russians, on the other hand, did have eyes in the sky and opened fire with deadly precision.

The tourniquets Artem applied to the wounds he suffered could have saved his life. But they were cheap, Chinese-made items and broke on the spot. Fellow soldiers stepped in to replace them, but he died while being evacuated.

“How can we spend millions of hryvnia on roads when our sons are dying on the front line without proper tourniquets?” says Ms. Olyanska. “It’s both corruption and mismanagement. We want the government to know that we do not agree with current procurement dynamics. We want them to get their priorities straight. We are at war now.”

Tolerance for corruption has waned in Ukraine. With so many lives at stake, national and local spending priorities are under the magnifying glass of regular civilians, corruption watchdogs, and investigative journalists. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has tried to address corruption scandals head-on, even if it means firing allies and reshuffling the entire Defense Ministry to appease the public and reassure international partners.

“Society became very intolerant towards any defense-related corruption,” says Olena Trehub, executive director of the Independent Anti-Corruption Commission and member of a public anti-corruption council within the Ministry of Defense. “The Defense Ministry today is the biggest manager of public funds in the country. Their budget increased tenfold due to the war. People of course are much more sensitive to this particular matter.”

Corruption or betrayal?

Combat application tourniquets – the same ones used by the U.S. Army – and drones fill several boxes in a run-down warehouse used as the base of Corporation of Monsters, a charity foundation that helps supply brigades on the front.

“Every day we receive dozens of requests for these items,” says charity founder Kateryna Nozhevnikova. “Every day I hear about a soldier losing his life because he didn’t have four tourniquets like he is supposed to.”

Ms. Nozhevnikova organized protests outside the Odesa City Council in August and September against a project to renovate the Kyiv District Court to the tune of 106 million hryvnia ($2.9 million) just a few years after it finished another renovation. She was joined by dozens of like-minded citizens who want their tax money directed to benefit Ukrainian troops rather than superfluous projects.

“The government is unable to fulfill even 50% of the demands of the army. At the same time, we see a lot of government spending and procurement on irrelevant things,” Ms. Nozhevnikova says. “When your house is on fire, you buy a fire extinguisher, not curtains for the windows. ... Why buy cheap Chinese tourniquets over good quality U.S. ones? It is either high-level corruption or high-level betrayal. It is scary to think that, but such thoughts crawl into your head. They [officials] have years of experience in this.”

This year started with corruption scandals related to war profiteering. One, exposed by the Nashi Groshi (Our Money) investigative website, concerned a military catering deal to deliver food – including eggs sold per piece at three times the usual market price – to units well removed from front-line areas that could have supply line issues. Overpriced generators were another purchase that sparked outrage in a winter marked by darkness due to Russian attacks on energy facilities.

August marked a tipping point. Investigators brought to light the purchases of overpriced winter jackets and multiformat corruption schemes to avoid military conscription. This set the stage for the removal of the entire top brass of the Ministry of Defense, including Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov, as well as all the country’s regional recruitment heads. In recent months, despite martial law, anti-corruption protests have been held in many Ukrainian cities.

“The scandals became an activator”

Such upheaval is less than ideal during an active war, but it is a requirement for a country vying for membership in the European Union, as Ukraine is.

Ukraine ranked 116th out of 180 countries in the 2022 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). That is not a score to boast about, but it did mark a 6-point improvement relative to the previous year. And Ukraine stood out among 15 countries that had made the biggest progress.

“Our CPI shows that countries in wartime conditions drop their score. We as Ukraine improved our score,” says Oleksandr Kalitenko, legal adviser at the Kyiv office of Transparency International. “Even in wartime conditions, we have the best score of the last 10 years. And we have seen some positive changes in the public procurement system.”

Mr. Kalitenko is one of several experts to say that the fight against corruption has gained urgency not in spite of the war, but because of it. Positive signs include the adoption of the State Anti-Corruption Program for 2023-25 that includes over 1,000 anti-corruption strategies complete with a timeline and key performance indicators.

Ukraine has five specialized anti-corruption bodies, but their track record is checkered. “Ukraine’s anti-corruption bodies have been persistently challenged by the lack of independently selected, permanent leadership,” notes the U.S. State Department. But even here, there is progress. When the war broke out, only two of them had independently selected leaders; now four do.

In March, Ukraine launched a unified whistleblowing portal. Lawmakers in September agreed to restore asset-declaration obligations that had been lifted due to security considerations after the start of the war. The Ministry of Defense in April announced the creation of a new procurement agency tasked with reforming the systems in place relating to nonlethal purchases.

“The scandals became an activator,” says Yulia Marushevska, head of the Change Support Office at the Ministry of Defense. “The temptation of corruption exists in every sphere. The question is how we can build systems that protect us from corruption as much as possible.” One answer, she says, is digitized payment systems with clear control mechanisms.

Anti-corruption efforts are also underway at the level of institutions and companies. At Ukroboronprom, a state-owned manufacturer of weapons and military hardware, the recruitment process of top management has been overhauled. Candidates are screened by committees of 15 people and asked to take part in a polygraph test designed to flag a history of, or amenability toward, corrupt behavior.

“We ask about 50 questions about corruption,” says a representative of a Ukroboronprom facility who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. Examples include: Have you ever been given money in an envelope? Did you ever take bribes? Do you have income other than your official one? Have you ever done anything that resulted in other people receiving bribes?

What they want to avoid is people bribing their way into high-level posts – such as director of a specific plant – and then using that role to steal money or to make deals for overpriced goods in exchange for a kickback. “What we do, we try to change the system to take these risks away, so there will be no such possibilities,” he says. “And so that the appointment of these positions will not rely just on the decision of one person.”

A bigger threat than nukes

The key is leadership, according to Daria Kaleniuk, executive director and co-founder of the Anti-Corruption Action Center nongovernmental organization. “The largest risk to corruption in Ukraine is associated with the failure of President Zelenskyy to build a proper recruitment system for top positions in the government,” she says. “He appoints usually loyal people and not necessarily professional people; sometimes these people are low integrity. That is a big mistake ... [because they] are taking very high positions and are in charge of very important, crucial state resources.”

All the dismissals this year suggest that Mr. Zelenskyy read the room. An opinion poll commissioned by Transparency International found that 77% of Ukrainians see corruption as a major concern. Another poll found that Ukrainians see corruption as a high security threat – even higher than the threat of a nuclear strike by Russia.

“The reason is the following: The war reached every family in Ukraine,” says Ms. Kaleniuk. Every family has either a family member or friend fighting in the trenches. Everybody has a relative or friend who was either wounded or killed in action. About half the population faced the need for relocation as a result of the war or had relatives who had to move because of the war.

At the same time, Ukrainians are emptying their pockets to donate to charity foundations and raise funds for specific brigades or units in the army. Ukrainians understand that if a soldier on the front line does not have tactical or medical equipment, she says, a reason for that is the failure of proper, timely procurement.

And Ukrainians pay taxes. When the Ministry of Defense cannot properly arrange the procurement of food for the army, it means money was wasted on overpriced eggs rather than spent on much-needed equipment. All of that is blamed on inefficiency, poor leadership, and corruption.

“We understand that during the wartime, the inefficiency of the Defense Ministry kills people,” she says. “The absolute majority of Ukrainians understand that in order to win, we need to be managed better; our army and our security and defense resources need to be managed better than those of our enemy.”

Reporting for this story was supported by Oleksandr Naselenko.

The Explainer

Could Ukraine take back Russian-occupied Crimea?

Ukraine has repeatedly attacked targets on the Russian-occupied peninsula of Crimea – which is of vital strategic importance to Moscow. These attacks are not just pinpricks, say experts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As their closely watched summer counteroffensive extends into autumn, Ukrainian forces struggling for a breakthrough have been stepping up attacks on the Russian stronghold of Crimea. Allies are hoping that the recent arrival of American long-range missiles could help bolster their efforts.

Invaded and illegally occupied in 2014, Crimea is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s prized strategic possession and the Achilles’ heel of his war effort, military analysts say.

Its geography as a peninsula makes it vulnerable to being isolated. But its warm-water harbor and access to the Black Sea make it vital to Russian fighting forces. It’s an attractive target, in other words, for Ukrainian war planners – particularly as home to a major Russian air base and the Black Sea Fleet, which docks at the deep-water port of Sevastopol. Severing Russia’s land bridge to Crimea has been a key objective of Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

The peninsula is also connected directly to Russia by the 12-mile-long Kerch Strait Bridge. Commissioned by Mr. Putin in 2016, it’s a vital supply line, and Ukrainian special forces have hit it repeatedly with everything from explosives to jury-rigged drones. Ukraine’s defense minister recently promised that his country would keep on doing that until the bridge is destroyed.

How serious are these attacks, and could Ukraine take back Crimea? The Monitor’s global security correspondent explains.

Could Ukraine take back Russian-occupied Crimea?

As their closely watched summer counteroffensive extends into autumn, Ukrainian forces struggling for a breakthrough have been stepping up attacks on the Russian stronghold of Crimea. Allies are hoping that the recent arrival of American long-range missiles could help bolster their efforts.

Invaded and illegally occupied in 2014, Crimea is Russian President Vladimir Putin’s prized strategic possession and the Achilles’ heel of his war effort, military analysts say.

Its geography as a peninsula makes it vulnerable to being isolated. But its warm-water harbor and access to the Black Sea make it vital to Russian fighting forces. It’s an attractive target, in other words, for Ukrainian war planners – particularly as home to a major Russian air base and the Black Sea Fleet, which docks at the deep-water port of Sevastopol. Severing Russia’s land bridge to Crimea has been a key objective of Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

The peninsula is also connected directly to Russia by the 12-mile-long Kerch Strait Bridge. Commissioned by Mr. Putin in 2016, it’s a vital supply line, and Ukrainian special forces have hit it repeatedly with everything from explosives to jury-rigged drones. Ukraine’s defense minister recently promised that his country would keep on doing that until the bridge is destroyed.

How has Ukraine attacked Russian forces in Crimea?

In one of the most high-profile missile strikes of the war, Ukrainian officials in September claimed to have killed dozens of officers as well as Adm. Viktor Sokolov, head of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Moscow denied these claims, releasing unverified videos of the admiral in meetings as proof of life.

What’s clear from satellite imagery is that the strike left the fleet’s headquarters in Sevastopol caved in and smoking. This happened, significantly, despite robust Russian air defenses and electronic warfare capabilities, notes a report this month from the Institute for the Study of War think tank in Washington.

Ukrainian long-range missiles also took out an amphibious assault landing ship and an attack submarine in Sevastopol last month. These were “incredible” hits, says retired Lt. Gen. Frederick “Ben” Hodges, former commander of U.S. Army forces in Europe – particularly since Russian ships are one of the main platforms Moscow uses to shoot its own missiles into Ukraine.

Kyiv has also continued to target the Kerch bridge. A July strike left a span dangling precariously, and a massive explosion last October shut down heavy traffic on it for months.

Are these attacks pinpricks or serious blows?

Though Russia routinely claims to have repelled most of the Ukrainian military’s attempted attacks – and it has – it is clear that defending Crimea is siphoning off its resources.

To protect the Kerch bridge from Kyiv’s tenacious naval drones, Russian forces built an extensive underwater barrier of submerged ships. They have also stationed missile defense batteries, attack helicopters, and even truck-mounted smoke generators there.

Recent missile strikes have also forced Moscow to move a number of ships out of Sevastopol. This has diminished the effectiveness of the Black Sea Fleet, including its ability to enforce blockades on Ukraine’s exports, according to a recent British defense intelligence report.

At minimum, analysts say, Crimea is no longer the safe harbor it once was. This is in large part because Western long-range missiles, which can travel up to 150 miles, are increasingly allowing Ukraine to strike “high-value targets” in attacks that are far from pinpricks, Mr. Hodges says.

As a result, although Russia’s extensive air defenses are still able to thwart most missile attacks, Russian ships and anti-aircraft systems that were once safely out of range are now in the crosshairs of Ukrainian forces.

At the same time, Ukraine has long been lobbying for the U.S. Army Tactical Missile System, known as ATACMS (pronounced “attack-’ems”). The Biden administration, in the face of growing congressional opposition to Ukraine aid, quietly greenlighted a small number of these long-range missiles in September. They turned up on the battlefield this month. But U.S. defense officials also warn that America’s stockpiles of the weapon are low.

Still, Ukraine had hoped this U.S. pledge would inspire Berlin to share its own long-range Taurus missiles. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in early October nixed this, however, reportedly expressing concern Kyiv might use them to blow up the Kerch bridge.

Could Ukraine take back Crimea?

To have a chance of this, analysts tend to agree that Ukrainian forces must fight their way to the Sea of Azov in order to cut off the land bridge to the Crimean Peninsula, which Russia now occupies.

This is a tall order, to put it mildly: Russians have dug in and fortified their front lines there with minefields and other heavy-duty barriers. It’s far tougher, military strategists know, for attackers to dislodge such positions than it is for defenders to hold them.

Tanks help with an offense, of course, which is why Kyiv lobbied so hard to get them last year. What delayed their arrival was in large part concern about Mr. Putin’s redlines: Crimea is sacred to him, and threatening it could push him to use his nuclear arsenal, the thinking goes.

Western officials don’t want to be “irresponsible,” but believing this theory is to some extent also buying into Mr. Putin’s hype, says Iulia-Sabina Joja, director of the Black Sea program at the Middle East Institute in Washington. He has “said he really cares about Crimea – but so does he care about a lot of things that aren’t his,” Dr. Joja says.

Still, while ATACMS are manufactured to have a maximum range of some 180 miles, the ATACMS recently delivered to Ukraine from the United States have a shorter range of some 100 miles, in order to guard against the possibility that they could be used to strike across the actual Russian border and further escalate the war.

That said, Mr. Putin won’t lose leadership of Russia if he’s forced to surrender Crimea, argues Mr. Hodges. He adds that the exodus of Russian men fleeing conscription bears out a deep disinterest in fighting for the territory among Mr. Putin’s political base, even as Russian tourists continue to flock there for vacations.

At the same time, fighting spirit has achieved the near-impossible on the battlefield before, analysts note, and for this reason, it’s important to examine what Crimea means to Ukraine, too.

Specifically, Russia is determined to economically strangle Ukraine. It purposely built the Kerch bridge low enough, for example, to block 30% of Kyiv’s maritime cargo traffic. “Ukraine cannot survive economically” without Crimea, Dr. Joja says.

Officials in Kyiv know, too, that military campaigns are fought not just to achieve battlefield objectives, but also to set political conditions for peace. If Kyiv can demonstrate that it can credibly threaten Russian control of Crimea, Ukrainian forces not only alarm vacationing Muscovites and boost Ukrainian morale, but also can potentially strengthen Kyiv’s position in future negotiations.

To this end, Crimea is “decisive terrain,” Mr. Hodges posits. “Whoever controls Crimea is going to win this war.”

How US ambassador’s home in China got its name

Nearly half a century ago, George H.W. Bush and his wife helped usher in a new era of U.S.-China relations. Though China looks different today, the couple’s leadership and perseverance still hold lessons for present-day diplomats.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When U.S. Ambassador Nicholas Burns and his wife first arrived in Beijing in February 2022, he was surprised to learn that their house in the quiet embassy district did not have a name.

Then he thought of George H.W. Bush, who arrived with Barbara Bush in October 1974, having turned down prestigious postings in London and Paris to serve as head of the United States Liaison Office in Beijing. The experience would prove formative for Mr. Bush’s understanding of foreign affairs and consequential for U.S.-China relations. He became the only American ambassador to China to rise to the presidency.

The current occupants of 17 Guanghua Road recently celebrated that pioneering diplomatic couple by dedicating the house as “Bush House.” Despite vast changes, parallels exist between then and now: The two countries once again stand at a crucial juncture in their ties, are emerging from years with limited contacts, and struggle with fundamental differences even as they face the necessity to get along.

“I feel good about the progress we’ve made in the last five months,” says Ambassador Burns, noting that China and the U.S. are now cooperating well on issues of climate change, agriculture, and people-to-people exchanges.

How US ambassador’s home in China got its name

As dusk falls on a crisp October evening in Beijing’s quiet Jianguomenwai embassy district, guests flow into 17 Guanghua Road, the stately yet unassuming residence of U.S. Ambassador Nicholas Burns and his wife, Elizabeth Baylies.

Persimmons ripen on trees nearby, and magpies flit around the ancient Altar of the Sun park across the street, where early risers often perform tai chi. People cycle slowly by. A solemn-faced Chinese army guard stands at attention at the gate.

Indeed, the house and its immediate surroundings bear similarities to what then-U.S. Ambassador George H.W. Bush found when he arrived here almost exactly 49 years ago, assuming his post as head of the United States Liaison Office in Beijing. At that time, Chairman Mao Zedong’s radical Cultural Revolution was ongoing, and ties between the two countries – estranged from 1949 until President Richard Nixon’s historic China trip in 1972 – were in their infancy.

“We swung into the mission: nice, clean, great-looking U.S. seal, two PLA [People’s Liberation Army] guards at the gate,” Mr. Bush wrote in his diary on Oct. 21, 1974, his first night in Beijing. He asked his wife, Barbara, to “get a ping-pong table and a couple of bicycles” as soon as she could. Then, as the wind howled at the windows, reminding him of West Texas, he went to bed early.

Last Friday, the dramatic sweep of five decades of U.S.-China relations seemed telescoped in time as the current occupants of 17 Guanghua Road celebrated that pioneering diplomatic couple – dedicating the house as “Bush House,” in honor of President Bush and first lady Barbara Bush. Despite vast changes, parallels exist between then and now: The two countries once again stand at a crucial juncture in their ties, are emerging from years with limited contacts, and struggle with fundamental differences even as they face the necessity to get along.

“This is the house where America returned to China in 1973, 50 years ago this summer, after an absence of 24 years,” Ambassador Burns told the gathering. “So with our celebration this evening, we honor the return of the United States to China. And we are here to stay in China this time.”

Finding connection

Mr. Bush had surprised his boss, President Gerald Ford, by turning down offers of two prestigious diplomatic posts – London and Paris. “He said, ‘With all due respect, I want to go to China,’” says Alexander “Hap” Ellis III, chair of the board of the George and Barbara Bush Foundation and Mr. Bush’s nephew, who attended the dedication. “He had this instinct that China was going to be a hugely important country.”

The early Beijing posting would prove formative for Mr. Bush’s understanding of foreign affairs and consequential for U.S.-China relations, as he became the only American ambassador to China to rise to the presidency.

To be sure, daily life in Beijing for the Bushes held a stark contrast to that of Mr. Burns and Ms. Baylies. Mr. Bush rode a bicycle – with a makeshift “Texas George” license plate – all around the city, sometimes donning goggles during dust storms. Iconic photos show the couple touring around markets and mingling with ordinary people, seemingly with little security.

Mr. Bush commented in his diary about drab clothing and a general lack of “gaiety,” cabbages stacked high on windowsills, and ubiquitous mule-drawn wagons that he thought would clog roads if China wanted to mobilize conventional military forces. He oversaw a tiny mission with nine U.S. diplomats, deciding he needed an “agricultural person” but no military attaché.

Life at 17 Guanghua Road is not as free for its current residents. Arriving at the now heavily gated residence after a long commute on Beijing’s traffic-clogged highways, Ambassador Burns – who oversees several hundred U.S. employees from 47 government agencies – laughs when asked if he envies aspects of how the Bushes got around. “Yes,” he says, recalling how Mr. Bush and his mother casually biked down to Beijing’s Tiananmen Square – no bodyguards, no armored cars.

“Libby and I actually walked, in our second or third month here, from here to Tiananmen, and I think we went through 13 police checkpoints,” he says. “We were stopped at one for about 20 minutes because they really couldn’t figure out what the American ambassador was doing walking through Tiananmen.”

Still, the couple find ways to connect with people. Like the Bushes before them, they are both studying Chinese. They strike up conversations on second-class train rides and go to local sporting events, such as a recent Beijing soccer match. “We were seated with all sorts of people around us,” he says. They sported green scarves, the color of the local soccer club, which earned them high-fives from other spectators. “It was good,” he says.

Righting the ship

More broadly, some fundamental challenges remain similar for both ambassadors. Mr. Bush said he came to China “in spite of great warnings of isolation.” When Mr. Burns and Ms. Baylies arrived in February 2022, China was largely cut off from the world by its strict COVID-19 prevention regime, which kept out most foreign visitors for three years.

“We had that 21-day quarantine,” says Ms. Baylies. “We were lucky enough to be quarantined in this house.”

Exploring their new home during those wintry days of isolation, she says, “Nick was surprised that this house did not have a name,” and lit upon the idea of Bush House.

Mr. Bush labored to try to form personal connections with Chinese leaders, starting with soon-to-be paramount leader Deng Xiaoping. Years later, President Bush wrote that his longstanding friendship with Mr. Deng helped prevent Sino-American relations from “derailing.” Similarly, Mr. Burns has worked to rebuild high-level contacts severed by both pandemic policies and political tensions. In a positive turn, a string of U.S. Cabinet members, lawmakers, and other senior envoys have arrived in Beijing since June.

Even as they compete as “rivals” in key realms such as technology, China and the U.S. are now cooperating well on issues of climate change, agriculture, and people-to-people exchanges, he says.

“I feel good about the progress we’ve made in the last five months,” says Ambassador Burns.

The Chinese balloon crisis in early February “was kind of rock bottom in the relationship,” he adds. “We’ve righted the ship.”

One critical exception is military-to-military ties, which have yet to be restored.

“It’s frustrating,” he says. “There ought to be very close military-to-military contacts. We are working this issue with the Chinese as hard as we can, and it’s up to them. That’s one way you drive down the probability of any conflict,” which “would be catastrophic for both countries and the world,” he adds.

Mr. Bush also voiced many frustrations, but some notes of nostalgia entered his diary as he neared his departure. In July 1975, he wrote that he would not forget the sound of “early morning singing in the park” or “the jingle of bicycle bells.”

At Friday’s dedication, Chinese Executive Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Ma Zhaoxu spoke of Mr. Bush’s belief in the ability of China and the U.S. to resolve their differences, and of his reluctance to leave Beijing in December 1975. Overall, Mr. Bush would make dozens of trips to China in his lifetime.

“I may forget the four tones of Mandarin I learned here,” Mr. Ma, speaking through a translator, quoted Mr. Bush as saying. “But I will never forget the warm hospitality of the Chinese people. Maybe no more than three weeks after I return home, I will already be wanting to come back to No. 17 Guanghua Road.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Bulgaria gavels in rule of law

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For the past six years, rule of law has declined in nearly 4 out of 5 countries – including the United States – according to surveys by the World Justice Project. Yet in 2023, one country has notably bucked this trend: Bulgaria. Once dubbed the most corrupt member of the European Union, the Black Sea nation of 7 million people ranked first this year in making the most progress in reforms such as greater equality before the law.

Why Bulgaria? After mass protests in 2020 and 2021 against corruption, the country went through five elections in two years. Last spring, the upswelling of public support for honest governance finally brought an anti-graft party, We Continue the Change, to power.

Despite the world’s downward trend in rule of law, Bulgaria has shown what can happen when more citizens, as one survey found last year, “believe that by their own actions they can change things for the better.” Such progress in rule of law points to the possibility of a universal law of progress for all nations.

Bulgaria gavels in rule of law

For the past six years, rule of law has declined in nearly 4 out of 5 countries – including the United States – according to surveys by the World Justice Project. Yet in 2023, one country has notably bucked this trend: Bulgaria. Once dubbed the most corrupt member of the European Union, the Black Sea nation of 7 million people ranked first this year in making the most progress in reforms such as greater equality before the law.

Why Bulgaria? After mass protests in 2020 and 2021 against corruption, the country went through five elections in two years. Last spring, the upswelling of public support for honest governance finally brought an anti-graft party, We Continue the Change, to power. Party co-leader Kiril Petkov promised “ministers who will work for Bulgaria without stealing."

Since then, many prosecutors deemed corrupt have been fired. Constitutional reforms in the judiciary are in the works. There is now more competition for the promotion of judges. Legal aid for defendants has expanded.

The new government has ushered in greater transparency. In October, after an inspection of major roads, it said 50% had been built with deficient materials. Another probe found delays and violations in more than 70 proceedings against officials.

By September, the European Commission decided to end its special monitoring of Bulgaria for meeting EU legal standards, citing progress in anti-corruption measures and judicial reform. That decision comes as more Bulgarians are eager for the EU to allow them visa-free travel and to have their country join the eurozone.

Despite the world’s downward trend in rule of law, Bulgaria has shown what can happen when more citizens, as one survey found last year, “believe that by their own actions they can change things for the better.” Such progress in rule of law points to the possibility of a universal law of progress for all nations.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Good news

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Joan Kohler

God’s limitless, universal goodness and peace is a promise for everyone, at every moment.

Good news

Who owns today, and every day?

Influencers? Pundits? Disrupters?

Purveyors of catastrophe and doom?

Or You, God?

Divine Love, encircling one and all,

divine Life, animating good,

I trust myself, I trust us all,

to Your living Word.

Your Word of the day, Your Word every day

is good – the Gospel’s good news

of liberation, of restoration.

This is the truest “news cycle” – morning, noon, and night –

and Yours is the only voice.

Your infinitely stable self-containment knows

no uncontained violence, no overspill of flood,

unquenchable flame, or jarring quake.

Vicious warring over whose way should win

concedes the one true way –

Your good-for-all way, God –

not one, but all of us, are Your elect,

spiritual and responsive to Your law.

Your glorious, endless day sees good alone unfolded,

not life and hope imploded;

Your economy of love yields glad prosperity, never bleak austerity;

the harvest of Your good that feeds and keeps us never fails;

revelation and progress are the order of Your day.

With fearless expectation we tune in to Your news

and Your views, as reported by Your Christ,

announcing Truth’s always equitable rulings,

celebrating the all-inclusiveness of Your love

and how Your measureless resources supply all needs.

And with this good news, we find peace in Your day.

Viewfinder

A home for a diva

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at what it means for former President Donald Trump that several high-profile and valuable allies have reached plea deals with prosecutors. Please join us!