- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Trump has rebounded steadily since 2022. What happened?

- Today’s news briefs

- Around the globe, the politics of war in Gaza is local

- Why the Supreme Court took this death penalty case

- In Greece, getting asylum can add to refugees’ burdens

- How a Muslim tailor and Hindu priest fought hate in India

- Wild seas and alien wonder: January’s best books

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Civil society

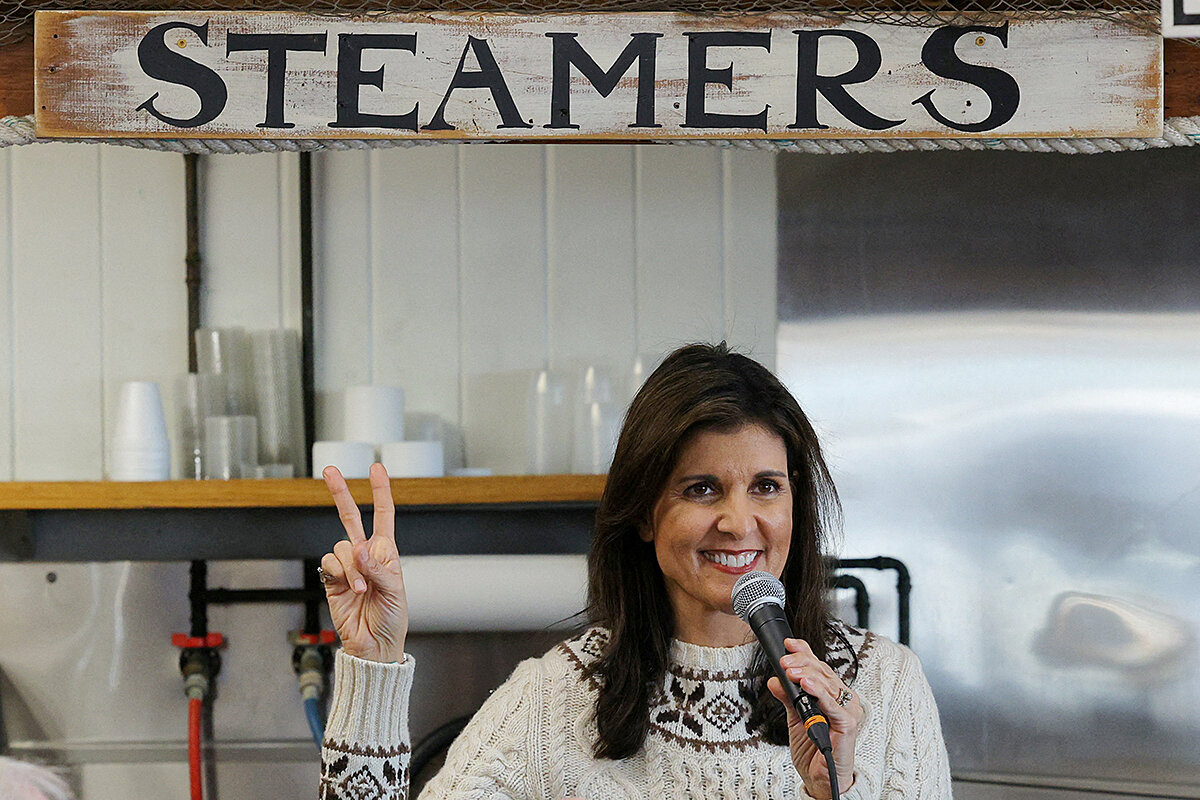

As New Hampshire prepares to vote in Tuesday’s presidential primary, the good-natured vibe is strong, says veteran political reporter Linda Feldmann. Locals and “political tourists” soak up the energy and stare down the cold. Haunts like Concord’s Red Arrow Diner, festooned with candidate pictures, draw crowds. Linda met a voter who always attends every candidate’s events. Democrats enthusiastically wave placards on street corners to encourage write-in votes for President Joe Biden. (He declined to be on the ballot because the Democratic Party awarded first-in-the-nation status to South Carolina, something New Hampshire is disregarding.) “For this short period,” says Linda, kitted out in layers of L.L. Bean wool, “New Hampshire is the center of the political universe.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump has rebounded steadily since 2022. What happened?

As New Hampshire votes, the departure of Ron DeSantis underscores how dominant Donald Trump has become in the Republican nomination race. Yet back in 2022, his rebound looked far from certain. What explains the shift?

Not that long ago, many Republican voters were uncertain about former President Donald Trump. Even self-identified Trump fans expressed interest in finding a “fresh face” – someone who could carry his policies into the future. Someone untainted by the riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Someone without all the legal troubles and the unfiltered mouth.

“Trumpism without Trump,” the mantra went.

For a time, Ron DeSantis looked like he might fit the bill. In the wake of the 2022 midterms, in which the Florida governor won reelection by 19 points even as many Trump-promoted candidates lost, he briefly led in GOP presidential primary polls.

Today, however, the Floridian is out of the race and has endorsed Mr. Trump. On the eve of the New Hampshire primary – now a two-person race between Mr. Trump and former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley – polls show Mr. Trump with a solid lead. A majority of Republicans appear ready to support him despite – perhaps even because of – the 91 felony counts he faces in four criminal cases.

A combination of factors appears to be in play. Polls suggest a circling-the-wagons response to the lawsuits. Ultimately, many Republicans may simply believe Mr. Trump is the strongest candidate to take on President Joe Biden in the fall.

Trump has rebounded steadily since 2022. What happened?

Not that long ago, many Republican voters were uncertain about former President Donald Trump.

In interviews and surveys, even self-identified Trump fans expressed interest in finding a “fresh face” – someone who could carry his policies into the future. Someone untainted by the riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Someone without all the legal troubles and the unfiltered mouth.

“Trumpism without Trump,” the mantra went.

For a time, Ron DeSantis looked like he might fit the bill. In the wake of the 2022 midterms, in which the Florida governor won reelection by 19 points even as many Trump-promoted candidates lost, he briefly led in GOP presidential primary polls.

Today, however, the Floridian is out of the race, having endorsed Mr. Trump after a dismal campaign that never could find its footing. And on the eve of the New Hampshire primary – now a two-person race between Mr. Trump and former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley – polls show Mr. Trump with a solid lead. A majority of Republicans say they support another Trump nomination, despite – or, for many supporters, because of – the 91 felony counts he faces in four criminal cases.

The former president’s resurgent hold on his party, as reflected in last week’s strong performance in the Iowa caucuses and a recent flood of high-level endorsements, can be attributed to a combination of factors. Polls suggest a circling-the-wagons response from voters after his criminal indictments. The passage of time may have softened some voters’ memories of the chaotic final months of his presidency.

At the same time, given the strength of Mr. Trump’s persona, for better or worse, “Trumpism without Trump” may never have really been a workable concept. Mr. DeSantis was hamstrung, too, by his reluctance to bash Mr. Trump, lest he alienate the people he hoped would migrate to him.

Ultimately, however, many Republicans may have found their way back to supporting Mr. Trump simply because they do not want President Joe Biden to win reelection – and they believe Mr. Trump is the strongest candidate to take him on.

“Republicans believe [Mr. Trump] deserves another chance,” says Scott Jennings, a political adviser in the George W. Bush White House. “They believe he was treated unfairly, and they think [President] Biden is that weak.”

Haley and the party’s old-style wing

Ms. Haley, the remaining Trump rival still in the race, has offered a more direct contrast in both style and substance than Mr. DeSantis did. Much of her platform is a kind of throwback to old-style establishment Republicanism that stands for fiscal responsibility, American leadership in the world, and conservative values.

As United Nations ambassador for two years under Mr. Trump, Ms. Haley also represents a global perspective, in direct contrast to the “America First” posture of both Mr. Trump and Mr. DeSantis. And more than a few Haley fans, men and women, say that it’s about time the United States has a female president.

Ms. Haley frequently points to polls showing her beating Mr. Biden in a head-to-head matchup by double digits.

General election polls show Mr. Trump slightly ahead of Mr. Biden on average, which dampens Ms. Haley’s argument of electability – perhaps her strongest selling point. For many New Hampshire Republicans, polls showing Mr. Trump winning in November are all they need in deciding what to do Tuesday.

Mr. Trump is a “cad; we know that,” says Joe Hollen, a Trump supporter from Weare who works in information technology. But “with all these stupid lawsuits, yeah, they’re trying to get him. And I’d want him as a boss,” he adds. “He knows how to run things. He’s a fighter.”

Dueling views of Trump

There are many ways to look at Mr. Trump. In one view, he’s damaged goods, twice impeached, multiply indicted, and only a few years younger than the octogenarian Mr. Biden. Critics note his verbal gaffes, such as confusing Ms. Haley with former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. And critics say his rhetoric seems more unhinged than ever, replete with a verbal nod about being a dictator in a second term – but only “on Day 1.”

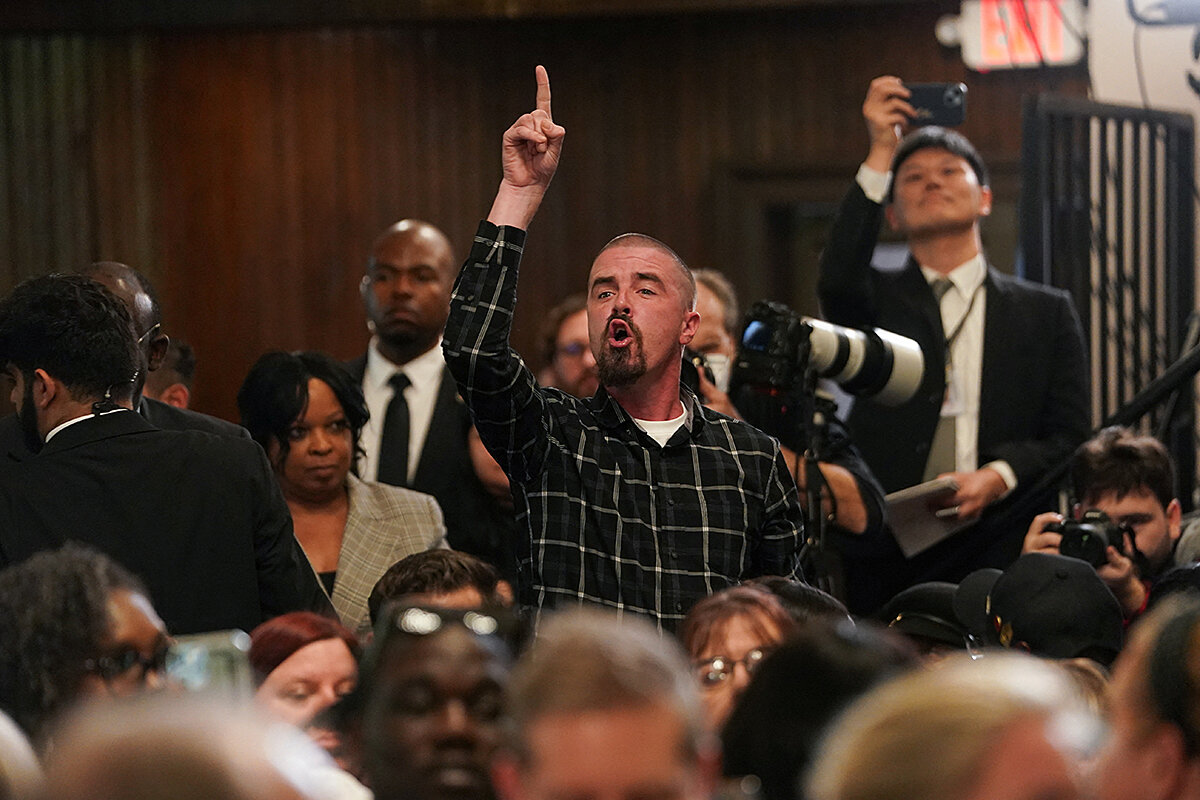

But go to a big Trump rally in a sports arena, like the one in Manchester last Saturday night, and it can feel like 2016 all over again. He draws an audience of thousands – far surpassing the mere hundred or so who show up for Haley events – and commands the stage for an hour and a half with vigor and, at times, entertainingly.

Some analysts say Mr. Trump has once again benefited from a divided opposition – with anti-Trump Republicans unable to settle on a single candidate early enough to create a competitive contest before it was too late.

“The party didn’t coalesce around one alternative to Trump, and that’s what the skeptics needed,” says Shana Gadarian, a political scientist and expert on voter psychology at Syracuse University.

But Mr. Trump’s early vulnerability in the polls, if it ever really existed, also presented his rivals with a deceptively difficult task: winning over Trump fans who may have been open to an alternative but also didn’t want to hear any criticism of the former president.

Certainly, there’s a small slice of the party, “Never Trumpers,” who won’t vote for him – and will either write in a different Republican, vote for Mr. Biden, or stay home.

But those in the dominant cohort of Republicans either have always been enthusiastic about Mr. Trump or say they will vote for him grudgingly if he’s the nominee – flaws and all.

They know what Mr. Trump is about and say they’re willing to live with those real or perceived flaws. The main goal is to defeat what they view as Mr. Biden’s increasingly left-leaning policies – including an “open” southern border and student loan forgiveness – and continuing economic challenges.

“People have to make choices, and can do mental gymnastics to justify voting a particular way,” says Ms. Gadarian.

A prime example: evangelical Christians who support Mr. Trump foremost because he appointed the Supreme Court justices who helped overturn Roe v. Wade – a long-held goal of opponents of abortion rights.

“You can say, for example, that character isn’t really that important; because the other side is so bad, we must fight fire with fire,” Ms. Gadarian says.

What next as New Hampshire votes?

Analysts also say that concerns about the future of American democracy in a second Trump term are prominent to Democratic elites more than to everyday voters. Ask voters in New Hampshire what they care about, and responses include the cost of home heating oil, health insurance, and the flood of migrants at the southern border, not whether Mr. Trump is a wannabe dictator.

In tomorrow’s vote, one wild card is independents – the 40% of the electorate registered as “undeclared,” who can vote in either primary. Another wild card is the large pool of new potential voters: people who have moved into the state since 2020, plus young people now old enough to vote – up to 22% of the state’s electorate, according to a University of New Hampshire survey.

Mr. Trump may seem to have the nomination locked up, but New Hampshire has a history of surprises in its first-in-the-nation primary, and if Ms. Haley can come anywhere close to Mr. Trump, that may be enough for her to stay in the race.

But the South Carolina GOP primary on Feb. 24 could be tough for Ms. Haley, despite her status as a former governor. Mr. Trump has already locked up the endorsements of a slew of prominent Palmetto State politicians, including the current governor. Many appeared onstage with the former president at the Manchester rally last Saturday. And the day before, South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, a onetime rival for the GOP presidential nomination, endorsed Mr. Trump at a rally in Concord.

Today’s news briefs

• Palestinian death toll hits 25,000: A total of 25,105 Palestinians have been killed in Israeli strikes since Oct. 7, the Gaza Ministry of Health said.

• DeSantis drops out: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has suspended his Republican presidential campaign before the New Hampshire primary and endorsed Donald Trump.

• Harsh weather snarls Memphis: The 600,000 residents of Memphis, Tennessee, are on their fourth day of living under a boil-water notice after broken pipes caused low water pressure and left some residents with no water.

• Winningest NCAA coach: Stanford basketball coach Tara VanDerveer passed former Duke and Army coach Mike Krzyzewski with her 1,203rd career victory on Jan. 21.

Around the globe, the politics of war in Gaza is local

In what will be an extraordinary year of elections around the globe, the Israel-Hamas war could play an outsize role in a number of countries where global issues rarely have significant domestic political impact.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Around the world, politicians and voters are paying attention to the Israel-Hamas war.

That does not mean the war’s political ramifications have been uniform. Indeed, some see in the global impact a phenomenon that social scientists have dubbed “glocalization,” in which a global issue has differing impacts based on particular national interests and motivations.

Thus, in India, where Hindu nationalists have been demonizing Muslims for years as part of their pursuit of a unitary Hindu state, the focus has been on Hamas’ horrific attacks. But in Muslim countries and across much of the West, public attention has fixed more on the destruction of Gaza and the staggering Palestinian death toll.

In the United States, President Joe Biden’s reelection prospects have been hit by frustration among elements of his winning 2020 coalition with his unwavering support for Israel.

What the war’s impact on global politics suggests, some experts say, is an undying interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“There are a lot of wars, and many where a lot more people have been killed,” says Daniel Kurtzer, a former U.S. ambassador to Egypt and Israel, “but when it’s something involving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it seizes the world’s attention.”

Around the globe, the politics of war in Gaza is local

Shortly after Hamas fighters stormed across the Gaza border into Israel, killing and kidnapping hundreds of civilians and committing a range of atrocities, social media channels favored by India’s ruling Hindu nationalists lit up with dire warnings.

The common-thread message: Hindu-majority India, with its large Muslim minority, risked suffering the same fate as Israel.

Social media accounts associated with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party spun a scenario equating India’s Muslims with Hamas and jihadist extremism. Calling Israel’s war “our war,” some posts argued that the only way India could avoid a similar outcome would be to redouble support for Mr. Modi and the BJP in upcoming local and national elections.

“In the days since the Oct. 7 attacks, we’ve seen posts claiming that if Modi loses this year’s elections, there will be a genocide of Hindus in India,” says Praveen Donthi, senior India analyst with International Crisis Group in New Delhi.

“Of course such claims are baseless,” he adds, “but they demonstrate how these right-wing elements are using the events in Israel and Gaza to villainize Muslims and project their Islamophobic agenda.”

As it turns out, India is not the only country where the war in Gaza is having an impact on politics.

An undying interest in the conflict

In what will be an extraordinary year of elections around the globe – with as much as 40% of the world’s population casting a ballot – the Israel-Hamas war could play an outsize role in a number of countries where global issues rarely have significant political impact.

Those countries range from Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority state, to the United States.

In Indonesia, the war has forced candidates in next month’s presidential election to finesse a delicate two-step dance in which they support the widely popular Palestinian cause while rejecting Islamist extremism, which has afflicted the country.

And in the U.S., President Joe Biden’s reelection prospects have been hit by frustration among key elements of the coalition that delivered him to the White House – notably young voters, African Americans, Arab Americans, and other minorities – with the president’s unwavering support for Israel during its campaign in Gaza.

Those differences have bled into an argument over whether such criticism constitutes antisemitism.

What the war’s impact on politics across much of the globe suggests, some experts say, is an undying interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – when some had thought the decades-old issue was losing its global salience.

“We’re seeing it’s still true that anything related to Israel and the Palestinians is of outsized interest,” says Daniel Kurtzer, a former U.S. ambassador to Egypt and Israel who is now a professor of Middle East policy studies at Princeton University.

“There are a lot of wars, and many where a lot more people have been killed,” he adds, “but when it’s something involving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it seizes the world’s attention.”

An example of “glocalization”

That does not mean global reactions to the war or its political ramifications have been uniform. Indeed, some see in the global impact a phenomenon social scientists have dubbed “glocalization,” in which an issue of global interest has differing impacts depending on particular national interests and motivations.

Thus, in India, where Hindu nationalists have been demonizing Muslims for years as part of their pursuit of a unitary Hindu state, the focus has been on Hamas’ horrific attacks. But in Muslim countries and across much of the West, public attention has fixed more on Israel’s punishing destruction of Gaza and the staggering civilian death toll.

India’s dominant outlook on the war reflects a stark shift from a championing of the Palestinian cause under successive Gandhi governments to “a pro-Israel stance,” says Mr. Donthi of International Crisis Group.

“In the Hindu nationalists’ worldview, India should follow Israel’s example and become a Hindu-centric state in the way Israel is a Jewish state – and India should treat its Muslims the way Israel treats the Palestinians in Palestine,” he says.

“Officially the government supports a two-state solution,” he adds, “but politically there is tacit approval of Modi’s portrayal as the last bulwark against Islamist terrorism.”

Another unique response to the war in Gaza can be found in Germany, where an unquestionable dedication to Israel’s security – as atonement for its Nazi past and the Holocaust – has collided with growing criticism of Israel and a clamor to recognize other stains on German history.

“We’ve seen a spike in the last two years in discussions about how Germany remembers the Holocaust,” says Sina Arnold, a senior researcher and expert in antisemitism at Technical University Berlin’s Research Institute for Social Cohesion.

“There are attacks from both the right and the left on Germany’s memorial culture: that things have gone too far, that the dominant attention to the Holocaust doesn’t leave room for acknowledging ... Germany’s colonial past,” she says. “But since the Oct. 7 attacks, this has all boiled over and this debate has turned really toxic.”

Germany right is conflicted

Even so, the Israel-Hamas war and the intense debate around national memory are unlikely to have a direct impact on state elections slated for the fall, according to Dr. Arnold. In part, she says, that’s because the German far right, which polls suggest could make big gains in some states, is divided over Israel.

“On one hand, Israel is seen [on the far right] as a bulwark against Muslims, and as an authoritarian ethnostate they see as a model Germany should strive for,” she says. “But there is another side that is more open about its anti-Jewish attitudes, that recognizes Israel is the land of the Jews – and the far right doesn’t like Jews.”

Perhaps the biggest test of the war’s political impact won’t come until November, when President Biden’s staunch support for Israel could effectively be on the ballot.

That’s not because Israel is likely to be a major national issue, some experts say, but because of “glocalization,” and how, in a system based on individual state vote-counts, the Israel-Hamas war could make a decisive difference in states where Mr. Biden won last time by very narrow margins: Michigan, Georgia, Wisconsin, and Nevada.

“It really seems right now,” says Ambassador Kurtzer, that President Biden “could lose reelection over this.”

Why the Supreme Court took this death penalty case

A majority of U.S. states no longer conduct executions, and a majority of Americans now say the death penalty is not fairly applied. The Supreme Court has been reluctant to take many death penalty cases. Richard Glossip’s is different.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In debates about the death penalty, one figure looms large: Richard Glossip.

Since being placed on Oklahoma’s death row in 1998, Mr. Glossip has been tried twice. He has had nine execution dates. He has eaten three last meals. He has been reprieved from execution three times.

In addition to celebrities like Susan Sarandon and Kim Kardashian, Mr. Glossip found an unlikely ally advocating for clemency: Oklahoma’s Republican attorney general. Gentner Drummond submitted a brief to the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that Mr. Glossip did not receive a fair trial.

On Monday, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Mr. Glossip’s case.

That likely doesn’t signal a shift in the court. But it implies that the uncertainties of Mr. Glossip’s case are too extraordinary to ignore. And it comes at a time when, for the first time, a majority of Americans say they no longer trust the death penalty. Only 47% of Americans say that capital punishment is applied fairly, according to Gallup.

“It sounds as if the court is willing to review this case carefully,” says Robin Maher, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. “It sends a really strong statement about how important innocence is in death penalty cases.”

Why the Supreme Court took this death penalty case

In debates about the death penalty, one figure looms large on the national stage: Richard Glossip.

Since being placed on Oklahoma’s death row in 1998, Mr. Glossip has been tried twice. He has had nine execution dates. The prisoner has eaten three last meals. He’s been reprieved from execution three times.

The former hotel worker was found guilty of allegedly masterminding the murder of his boss. Mr. Glossip has claimed that he’s innocent. A TV docuseries portrayed his trial as unfair. He’s become a cause célèbre for death penalty skeptics such as Susan Sarandon, Richard Branson, and Kim Kardashian. Mr. Glossip also found an unlikely ally advocating for clemency: Oklahoma’s Republican attorney general. Gentner Drummond submitted a brief to the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that Mr. Glossip did not receive a fair trial.

On Monday, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Mr. Glossip’s case. After a long deliberation, its decision to take up the case took observers by surprise. The conservative court has been reluctant to intervene in death penalty cases.

Mr. Glossip’s case likely doesn’t signal a shift in the court. But it implies that the justices believe that the uncertainties of Mr. Glossip’s case are too extraordinary to ignore. And it comes at a time when, for the first time since the death penalty’s reinstatement in 1976, a majority of Americans say they no longer trust it. Only 47% of Americans say the capital punishment is applied fairly, according to Gallup.

“It sounds as if the court is willing to review this case carefully,” says Robin Maher, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, a Washington nonprofit that does not argue for or against the death penalty. “It sends a really strong statement about how important innocence is in death penalty cases.”

Mr. Glossip’s is not the only capital case the justices are being asked to consider. On Thursday, Alabama is scheduled to execute Kenneth Eugene Smith with nitrous gas, a novel form of execution that has only been used on animals before now. In 2022, the state botched an attempt to execute Mr. Smith via lethal injection. His lawyers have petitioned the court, arguing Alabama’s attempt to execute him twice constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

Ms. Maher points to a Utah case that has the potential to play out in the courts. Utah is planning to execute Ralph Leroy Menzies by firing squad. Mr. Menzies’ lawyers say that the method of execution is identical to a firing squad protocol that was found to be unconstitutional by a South Carolina court.

These cases arise at a moment when a majority of states appear reluctant to carry out the death penalty. Twenty-three states have banned the punishment entirely, while it is effectively defunct in several others. Last year, just five states, including Mr. Glossip’s home state of Oklahoma, carried out executions. Twenty-four people were executed in 2023 – up from a low of 11 in 2021, according to the Death Penalty Information Center’s annual report, but still well below 30. That was the ninth year in a row the number of executions had slipped below that threshold, down from a high of 98 in 1999.

States also appear wary of creating new capital cases: Last year, for the first time, fewer people were sentenced to death – 21 – than were executed.

“Public confidence in the death penalty requires the highest standard of reliability, so it is appropriate that the U.S. Supreme Court will review this case,” Attorney General Drummond said in a statement. “As Oklahoma’s chief law officer, I will continue fighting to ensure justice is done in this case and every other.”

Mr. Drummond isn’t exactly soft on crime. In his first year in office, he’s overseen several executions. But the attorney general filed a brief with the Supreme Court to request that Mr. Glossip’s sentence be vacated so that the case can be retried. The unprecedented brief cited the destruction of evidence and false testimony by the state’s star witness. That witness is the man who actually killed the hotelier whose murder resulted in Mr. Glossip being sentenced to death.

In 1997, a hotel employee named Justin Sneed bludgeoned to death his boss, Barry Van Treese. Prosecutors allege that Mr. Glossip commissioned the murder. They claim that the two men then split several thousand dollars in cash belonging Mr. Van Treese. Mr. Sneed, who wielded the weapon, a baseball bat, is serving a life sentence. He received a lesser sentence in exchange for agreeing to be the state’s key witness against Mr. Glossip. Supporters of Mr. Glossip claim that Mr. Sneed lied under oath. And an independent investigation found that the state not only withheld Mr. Sneed’s records from the trial but also destroyed evidence. In addition, Mr. Drummond’s brief argues that Mr. Sneed’s mental health, and treatment for it – which wasn’t disclosed by the state – is a key point in the case.

Paul Cassell, a lawyer for the Van Treeses, told the Monitor that the family is disappointed.

“The court has granted review, which will probably delay the case for another year,” says Mr. Cassell, a former federal judge and a law professor at the S.J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah. “But at the same time, the family is confident that when the court digs into the facts of the case, they’ll see that the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals decided it correctly and that the death sentence should be allowed to move forward.”

Since 2020, there have been nine instances in which the Supreme Court has overruled a lower court to allow executions to proceed, according to a report by Bloomberg Law. Mr. Glossip’s case is one of only two that the court has halted.

Since the documentary “Killing Richard Glossip” came out in 2017, Mr. Glossip has attracted several other unlikely advocates: GOP lawmakers in the Oklahoma Legislature.

For Oklahoma state Rep. Kevin McDugle, a Republican, the death penalty has always been a bedrock value. He says that foundation now has large chinks in it. He helped persuade 28 Republicans and six Democrats in the Legislature to ask the state to reexamine Mr. Glossip’s case.

“The reason this one is different is I don’t think I can name another case where the attorney general says, ‘We can’t kill someone. We can’t trust the first two trials that they’ve gone through. We need to have another hearing,’” state Representative McDugle told the Monitor in a phone call. “And the court systems ignore that and say, ‘No, we’re going to move to execution.’ I mean, that’s unprecedented.”

In Greece, getting asylum can add to refugees’ burdens

The asylum process is meant to offer a haven to those who are in danger. But in Greece, many of those granted refuge end up facing a new threat: hunger.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Many Afghans risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean to get to Europe in the hopes of being granted asylum. But for those awaiting a decision in Greek holding camps, formal refugee status can come as a burden rather than a relief.

The privilege means immediate loss of access to the camps’ food aid and housing in a country that offers little to facilitate integration. And that has led to a serious hunger crisis, particularly among those granted asylum.

Critics say that this is an intentional policy by the Greek government and the European Union to dissuade migration into the bloc. Authorities deny it, arguing they are caring for those eligible for aid. Regardless of what is intended, asylum-seekers are being pushed into a desperate situation by being deprived of basic aid just as they gain a legal foothold in Europe.

“[The camp is] like a prison – not just because of the fences but because of the lack of food. We don’t have money and we don’t have food,” says Davud Mohammedi, who arrived on the island of Lesbos with his family of five in August. “I spent all I had to come here.”

In Greece, getting asylum can add to refugees’ burdens

When Farzana and her family got asylum status in September, it should have made life easier.

After all, they had escaped the Taliban in Afghanistan and reached Greece via the Mediterranean route in early August at a moment when the Greek coast guard was being helpful to migrants.

But while her family feels safe now, the asylum decision created a new problem: hunger.

“People who get an asylum decision – positive or negative – stop getting food,” explains Farzana, who like many interviewed for this story gave only one name. “I’ve lost 5 kilos [11 pounds] since getting to Greece.”

Many Afghans risk their lives getting to Europe in the hopes of being granted asylum. For those awaiting a decision in Greek holding camps, formal refugee status can come as a burden rather than a relief. The privilege means immediate loss of access to the camps’ food aid and housing in a country that offers little to facilitate integration.

Critics say this is an intentional policy by the Greek government and the European Union to dissuade migration into the bloc. Authorities deny it, arguing they are caring for those eligible for aid. Regardless of what is intended, asylum-seekers are being pushed into a desperate situation by being deprived of basic aid just as they gain a legal foothold in Europe.

“[The camp is] like a prison – not just because of the fences but because of the lack of food. We don’t have money and we don’t have food,” says Davud Mohammedi, who arrived on the island of Lesbos with his family of five in August and now resides in the Ritsona camp, 43 miles from Athens. “I spent all I had to come here.”

Weaponized food aid?

In 2023, irregular border crossings at the EU’s external border reached approximately 380,000, driven by a rise in arrivals via the Mediterranean region. In Greece in particular, 48,563 people arrived via irregular means, over both land and sea.

Refugee aid organizations and human rights groups say the Greek government has weaponized food and is creating a hunger crisis to deter such arrivals. On June 15, nongovernmental organizations sent a letter to high-level Greek and EU officials in protest of the overnight decision to stop providing food and water to people outside of the asylum procedure living in a closed controlled-access center on the island of Lesbos.

“Food insecurity is part of the deterrence approach of the Greek government and of the EU,” says Lefteris Papagiannakis, director of the Greek Council for Refugees. “A small, but very significant part.”

The deterrence approach, he argues, expresses itself in many ways. In Greece, that includes the deportation of asylum-seekers across borders, making access to asylum difficult and complicated, and an EU-funded policy of putting asylum-seekers in remote locations on the Greek islands while their asylum claim is processed. At the European level, it is manifest in efforts to stem migration flows through bilateral deals like the EU-Turkey deal struck in 2016 or Italy’s recent agreement with Albania.

“It’s part of a larger political approach and a larger political choice,” argues Mr. Papagiannakis. “Whatever you can make difficult, you do it – directly or indirectly.”

In principle, he concedes, it makes sense that protection measures are stronger for asylum-seekers than for recognized refugees. They later theoretically gain the same rights and duties as Greek citizens. But when there is no pathway to learn the language, no access to the job market, and no housing, that logic no longer adds up.

The Greek Ministry of Migration and Asylum denies weaponizing food aid. It argues that only people applying for international protection are eligible for material aid, including food and water. It says it cares for the most vulnerable people by providing food and access to education to children, regardless of their status.

But Greece’s right-wing government has made a series of decisions that effectively strip refugees of the limited safety nets they had. In December 2022, it scrapped its support system for vulnerable asylum-seekers, even though the European Commission was willing to continue the funding. That impacted more than 6,000 refugees.

The European commissioner for home affairs has stated she has raised the issue of discontinuation of food with the Greek authorities on several occasions. But this month, she also said the EU needs an orderly migration policy, including swifter asylum processes like the ones Greece is implementing.

“The message is, ‘Don’t come’”

Doctors Without Borders teams working in Lesbos say they see the consequences of inadequate food. “Our team on Lesbos Island have come across different cases of patients affected by the food provision in the camp, whether it’s insufficiency of food or the quality of the food,” says Fouzia Bara, Doctors Without Borders’ medical coordinator in Greece and the Balkan migration mission.

The NGO is stepping in by providing iron supplements to pregnant women with iron deficiency, attributed to the bad nutrition and general conditions in the camp. It also treats children who have delayed growth, linked to lack of vitamins and access to nutritious foods because of long journeys and long stays in the camp.

And even with the support of charities, food shortages are common. Precious, who was smuggled from Nigeria to Greece, was forced to work as a pole-dancer for many years until she was able to pay off the €50,000 ($54,500) fee for her journey. She recalls a time when Greek charities gave enough that they would encourage her to come in a taxi to take back all the food aid. Now she bemoans getting no more than two pasta boxes during a recent food distribution.

“What we get now is very little, just enough for two, three days,” she says.

“There are many vulnerable cases, including cases of women resorting to survival sex – single and married women – for just €2 to €3,” says Apostolos Veizis, executive director of Intersos Hellas, which conducted 40 food distributions in Athens between February 2022 and October 2023. The bulk of recipients were migrants, asylum-seekers, recognized refugees, and undocumented individuals. Half reported having food just one to three times per week.

“Young children and babies suffer developmental consequences due to lack of food and poor nutrition. Greece is using access to food as a weapon to deter migration while Europe looks away,” Dr. Veizis says. “The message is, ‘Don’t come.’”

There are also collective kitchens like El CHEf in the district of Exarchia, which draws on the support of 40 to 50 volunteers who cook, pack, and serve meals six days a week.

“One of the big advantages of these collective kitchens is that you don’t need to have any documents to have food, whereas other actors do check documents,” explains Valia, a volunteer. “Here we offer solidarity. It is different from philanthropy. We might be in their position one day.”

Among those making giant pots of spaghetti that day is Katerina. Like her peers, she makes a strong distinction between the unwelcoming, vote-seeking policies of the government, and the more welcoming spirit of Greek grassroots communities.

“When you see all these people without access to food, water, home, and health, it is very sad,” she says. “It’s devastating to see Greece and other countries adopt policies that exclude people from life. When you have to survive, you don’t live.”

Jenny Tsiropoulou supported reporting for this story.

How a Muslim tailor and Hindu priest fought hate in India

As the inauguration of a controversial temple puts Ayodhya’s history of communal violence on center stage, a competing history gets less attention – one of olive branches, enduring friendships, and peaceful coexistence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Shweta Desai Contributor

On Monday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled an opulent new temple in Ayodhya, India – on the site where a Hindu mob leveled a mosque three decades ago.

The destruction of the Babri mosque, which right-wing Hindu groups claim was built over the birthplace of Hindu deity Ram, sparked months of violence and left deep fissures between the country’s Hindu majority and Muslim minority. The construction of the Ram temple became a rallying point for India’s growing Hindu nationalist movement, with Mr. Modi calling its inauguration “the beginning of a new era.”

Ayodhya’s Muslim community worries what that “new era” may hold for them.

But Valay Singh, author of “Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord,” says the city’s reputation as India’s “ground zero” of communal conflict overshadows its history as a heartland where different religious traditions have long intersected. For all of the violence Ayodhya’s seen, it’s also been the site of numerous Hindu-Muslim peace efforts and friendships – like that of Muslim tailor Sadiq Ali and high-ranking Hindu seer Mahant Gyan Das. Back in 2003, the pair hosted an interfaith feast that still inspires local activists today.

“Ordinary people here want to live in peace,” says Mr. Singh.

How a Muslim tailor and Hindu priest fought hate in India

The light blue walls of Sadiq Ali’s living room are adorned with photos of Hindu seer Mahant Gyan Das. The two have been friends since the 1980s, when Mr. Ali was a volleyball player and Mr. Gyan Das a wrestler. They bonded over their shared love of sports, and Mr. Gyan Das regularly visited Mr. Ali’s family tailoring shop to get his tunics stitched.

About 20 years ago, their friendship took on a new meaning. Days of violent riots had rocked the nation and left more than 700 Muslims dead. It tore open old wounds in Ayodhya, a north Indian city where the Muslim community was still reeling from the destruction of the historic Babri mosque by a Hindu mob in 1992.

Sensing the need for an olive branch, Mr. Gyan Das, then head priest of the city’s historic Hanuman Garhi temple, invited 1,000 Muslims to the temple premises during Ramadan to break their daily fast. Mr. Ali helped host the feast, which still fills its organizers with pride and nostalgia – especially as Ayodhya is once again in the spotlight for Hindu-Muslim tensions.

Monday afternoon, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled an opulent Hindu temple on the site where the Babri mosque once stood. Like the mob which leveled the mosque, Mr. Modi and his supporters in the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) claim that Babri was built over the birthplace of Hindu deity Ram, and the construction of the new Ram temple has become a rallying point for India’s growing Hindu nationalist movement. Indeed, Hindus around the world celebrated the temple’s inauguration, which Mr. Modi said marks “the beginning of a new era.” Ayodhya’s Muslim minority worries what that “new era” may hold for them.

In such polarized times, Mr. Gyan Das and Mr. Ali’s friendship offers a reminder of what Ayodhya could have – and perhaps still can – become: a symbol of multiculturalism and tolerance.

“Ordinary people here want to live in peace,” says Valay Singh, author of “Ayodhya: City of Faith, City of Discord.” He argues that the city’s reputation as India’s “ground zero” of communal conflict overshadows its history as a heartland where different religious traditions have long intersected. In fact, he notes, the land for the Hanuman Garhi temple was donated to the region’s Hindu community by Muslim ruler Shuja-ud-Daula in the 18th century.

“It was a common tradition for the religious establishments to receive patronage from the Muslim rulers,” he says. “This is how the two communities have been intricately linked.”

As the Ram temple saga draws to an apparent close, Mr. Singh hopes that Ayodhya’s legacy of interfaith harmony will survive.

A bond that inspires bravery

Hate speech, communal violence, and calls for genocide of Muslims have seen a rise in BJP-ruled states in recent years. But this religious strife has deep roots – several weaving back toward Ayodhya.

The destruction of the Babri mosque, for instance, came after decades of campaigning by right-wing Hindu groups, such as the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), and led to months of communal violence across India. In Ayodhya, Muslims and their properties were singled out. Mr. Ali’s shop was plundered multiple times.

“Nothing was spared, not even a spoon,” he says. “We just had the clothes on our body.”

Indeed, the mosque’s demolition and resulting chaos left deep fissures between the Hindu majority and Muslim minority throughout the country.

Those rifts grew during the 2002 Gujarat riots, which were sparked by a deadly fire on a train carrying Hindu pilgrims from Ayodhya to Godhra, Gujarat. Mr. Modi – then chief minister of Gujarat state – declared the fire an act of terrorism, prompting a wave of anti-Muslim violence in Godhra and beyond. More than 1,000 people were killed, and thousands more injured or displaced, over three days.

So the following year, Mr. Gyan Das approached Mr. Ali with his idea to organize an interfaith iftar fast-breaking meal at Hanuman Garhi.

At first, the tailor was baffled. He reminded Ayodhya’s most influential seer that after breaking fast, Muslims must offer the namaz prayers. Will the Hindu seers accept prayers to Allah on the temple’s premises?

Mr. Gyan Das was confident they would.

In November 2003, with fanfare and high security, saffron-robed priests from several local temples welcomed their Muslim guests, serving them fruits and yogurt. Around sunset, calls of “Allahu Akbar!” mingled with the sounds of conch shells and temple bells, as rows of Muslims bowed down to read the namaz. Both sides prayed together for peace and brotherhood to prevail across the country.

The Muslim community reciprocated. After the iftar, hundreds of seers marched to Mr. Ali’s home to break the Hindu Ekadashi fast with seviyan, a traditional sweet prepared by Muslims on festive occasions.

Many remember the event as an overwhelming success, but reactions in Ayodhya were split.

Reactions and legacy

Some of Mr. Gyan Das’ peers fiercely opposed the iftar, and the VHP held a 10-day demonstration accusing the priest of defiling the temple’s sacred premises. Religious hardliners filed a petition to ban such events in the future.

But many remember Muslims broadly welcoming the Hindu-led peace effort, with the horror of 1992 and the fallout of the Gujarat riots fresh in their minds. “Gyan Das took the bold initiative at great personal risk when the entire country was seething over the deaths” of the Godhra pilgrims, says Ram Shankar “Guddu” Yadav, a friend of Mr. Ali who helped host the seers.

The iftar also inspired Yugal Kishore Shastri, one of few outspoken Hindu priests who have left the far-right and put their faith in the spirit of Indian secularism.

Mr. Shastri says he split from the VHP after discovering that there was “no evidence of an ancient Ram temple under the mosque structure,” describing the theory as “an elaborate lie.” He has since dedicated his life to promoting communal harmony, organizing three interfaith iftars modeled after the 2003 feast and speaking out against the construction of the new Ram temple.

“Ayodhya’s seers have an obligation to maintain peace,” he says.

Although it’s getting harder for activists to cut through the vitriol and bring communities together – let alone find collaborative solutions to conflicts like the mosque-temple debate – he is confident that future generations of seers will walk in Mr. Gyan Das’ footprints. “There will always be a place for people who work for Hindu-Muslim peace,” he says. “Such initiatives will organically find ways to grow.”

In the meantime, Mr. Ali is still active in his shop, and Mr. Gyan Das has retired. Once a fierce opponent of the temple plan, the former priest has become reclusive after a brain hemorrhage in 2019 and largely avoids public interaction. Mr. Ali, of course, is an exception.

“He was here a few days ago,” Mr. Gyan Das said recently during a rare interview. “He will always be my friend.”

Books

Wild seas and alien wonder: January’s best books

Good stories transport. Great stories inspire. In our 10 picks for this month, characters face situations such as war and exile, offering insights into the strength of the human character.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Staff

People are often capable of enduring and, in some cases, triumphing over impossible odds.

In our book picks this month, characters do just that.

Bonnie Jo Campbell’s “The Waters” steeps readers in a fictional yet realistic portrait of rural Michigan and the women tough enough to live there. With lush and evocative writing, the book practically sprouts in your hands. Similarly evocative, Hisham Matar’s “My Friends” paints a picture of life under revolution through the eyes of a teenager exiled from Libya for protesting the Qaddafi regime.

In nonfiction, “The Survivors of the Clotilda” by Hannah Durkin sheds light on the stories of 110 enslaved people kidnapped from what is now Nigeria and taken to Alabama on the last slave ship to transport people to the United States. With a focus on the female survivors, the book reconstructs their lives after emancipation.

Rich and compelling, these books are sure to bolster the reader’s faith in the human capacity to persevere.

Wild seas and alien wonder: January’s best books

The Waters, by Bonnie Jo Campbell

Bonnie Jo Campbell is one of the chief practitioners of Midwestern Gothic, and the National Book Award finalist’s first novel in a dozen years is reason to rejoice. “The Waters” is an indelible portrait of rural Michigan and the women tough enough to live there, with writing so evocative it practically sprouts in your hands. Lush, brackish, and bracing, “The Waters” is not so much read as steeped in.

Wild and Distant Seas, by Tara Karr Roberts

This inventive historical novel is spun from a minor female character in “Moby-Dick.” Melville’s narrator, Ishmael, and his sidekick, Queequeg, are served chowder in Mrs. Hussey’s inn before they sail off on the Pequod with Captain Ahab. Ishmael’s short stay has lasting ramifications on the lives of the innkeeper and her female descendants.

The Curse of Pietro Houdini, by Derek B. Miller

Sheltering in a hilltop abbey southeast of Rome, a maverick and a 14-year-old orphan hatch a plan to save the abbey’s priceless paintings from the Nazis. Even as the pair endure war’s horrors, they refuse to abandon their crusade. Derek B. Miller delivers an irresistible story of defiance.

My Friends, by Hisham Matar

A teenager leaves his cherished family in Libya to pursue higher education at the University of Edinburgh. Protesting against the Qaddafi regime results in exile from his homeland. Hisham Matar provides insights into life under revolution and in exile.

Beautyland, by Marie-Helene Bertino

Adina, a human-looking alien growing up in 1980s Philadelphia, adores astronomer Carl Sagan. “He is looking for us!” she enthuses to her otherworldly superiors in a one of many life-on-Earth dispatches. Adina navigates human childhood while her single mom, unaware of her daughter’s true identity, struggles to keep them afloat.

The Wharton Plot, by Mariah Fredericks

In this mystery set in early 20th-century New York City, Edith Wharton, the arch, imperious novelist of “The House of Mirth” takes center stage. When an American writer gets shot, Edith agrees to shepherd his finished manuscript to publication. Censorship, corruption, and class privilege brush up against jealousy and regret in Mariah Fredericks’ pitch-perfect tale.

The Survivors of the Clotilda, by Hannah Durkin

Historian Hannah Durkin’s gripping account uncovers the stories of the 110 enslaved people kidnapped from what is now modern-day Nigeria and forced onto the last slave ship to transport captives to America. The Clotilda landed in Alabama months before the start of the Civil War; Durkin, with a focus on its female survivors, compellingly reconstructs their lives post-emancipation.

Our Enemies Will Vanish, by Yaroslav Trofimov

Yaroslav Trofimov, the Ukrainian-born chief foreign affairs correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, spent the early days of the war in Ukraine watching as ordinary citizens turned what looked like a certain defeat into a stalemate that inspired the world. Told with empathy and sensitivity, the story is both heartbreaking and inspiring.

The MAGA Diaries, by Tina Nguyen

Political journalist Tina Nguyen uses her own coming-of-age story to explain how conservatives play the long game by providing intellectual training and professional guidance to young people. Her chronicle is entertaining yet unsettling.

Everyone Who Is Gone Is Here, by Jonathan Blitzer

Jonathan Blitzer traces the roots of the immigration crisis back to what he terms America’s misguided Cold War-era interventions in El Salvador and Guatemala. The author’s powerful, compassionate account highlights individual stories, creating an epic portrayal of migration’s human stakes.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Gratitude as a global change agent

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, learned a valuable lesson last July. After he criticized Western allies a bit too much for not offering enough support against Russia, the United States openly advised him to show “a degree of gratitude” for the money and other aid already received.

Since then, Ukraine’s leader has shifted his narrative from one of gloom and grouse to one of tribute and thankfulness. He’s recently been on a gratitude tour, noticeably last week at the annual meeting of world leaders in Davos, Switzerland.

His turnaround – toward relying on gratitude to reinforce the generosity of others – reflects a shift in several other aspects of world affairs. Many experts working on problems such as war, poverty, and climate change point to the need to emphasize progress as a realistic antidote to what may seem like intractable situations.

“As appalling as crises in Gaza, Ukraine, or Sudan are, the narrative of a world in greater humanitarian need than ever before is misleading and self-defeating,” wrote Elias Sagmeister, a program manager at Ground Truth Solutions, a nongovernmental organization in Austria that shapes humanitarian policy.

Gratitude as a global change agent

The president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, learned a valuable lesson last July. After he criticized Western allies a bit too much for not offering enough support against Russia, the United States openly advised him to show “a degree of gratitude” for the money and other aid already received.

Since then, Ukraine’s leader has shifted his narrative from one of gloom and grouse to one of tribute and thankfulness.

He’s recently been on a gratitude tour, noticeably last week at the annual meeting of world leaders in Davos, Switzerland. With a new U.S. aid package pending in Congress, for example, Mr. Zelenskyy told American officials, “Ukraine is grateful to the President of the United States, the Congress and the entire American people for their unflagging and powerful support for our country.” Many European leaders heard similar appreciation.

“Ukrainian initiatives are gradually becoming global initiatives,” he told Ukrainians in a video address from Davos. “I am grateful to everyone who helps us with this.”

His turnaround – toward relying on gratitude to reinforce the generosity of others – reflects a shift in several other aspects of world affairs. Many experts working on problems such as war, poverty, and climate change point to the need to emphasize progress as a realistic antidote to what may seem like intractable situations.

“As appalling as crises in Gaza, Ukraine, or Sudan are, the narrative of a world in greater humanitarian need than ever before is misleading and self-defeating,” Elias Sagmeister, a consultant at Ground Truth Solutions, a nongovernmental organization in Austria that shapes humanitarian policy, wrote in the news site The New Humanitarian.

“A closer look at global data reveals a more nuanced – and even a more hopeful – reality,” he stated, citing the fact that famine is in a long-term decline while deaths from disasters are low compared with previous periods.

“The humanitarian hyperbole might seem helpful for short-term fundraising purposes, but repeating a false narrative comes at a price in the long run,” he wrote. “The public will tune out from repetitive messaging.”

“Instead, humanitarian leaders should point to past successes while making demonstrable progress on the reforms they have rightly committed to.”

Other thinkers, such as Harvard professor Steven Pinker, have made similar arguments about the need to recognize positive trends, such as a centurieslong drop in violence. “Partly it’s a negativity bias baked into journalism: things that happen, like wars, are news; things that don’t happen, like an absence of war, that is to say peace, aren’t,” Dr. Pinker told Quillette, an Australian online magazine.

Charles Kenny, an economist at the Center for Global Development, contends that the “fact of progress makes us morally bound to make it happen more.” The world can build on recent progress, he told Vox in 2022, citing the examples of lower child mortality, higher literacy, and greater civil rights.

Gratitude for progress can also elicit gratitude, as the president of Latvia, Edgars Rinkēvičs, indicated this month. In noting how the Ukrainians are the first line of defense against Russian aggression in Europe, he said, “We are grateful to the Ukrainians ... more than perhaps they should be grateful to us.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Is perfection our enemy or our friend?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Looking to God, perfect Love, as the source of limitless good has practical, healing effects.

Is perfection our enemy or our friend?

“Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good” is common counsel nowadays. It urges us to settle for “good enough” rather than chasing an elusive perfection. This is reflected in a product-testing approach termed Minimum Viable Product – that is, crossing a threshold where a product has minimal functionality but is capable of working successfully.

In “projects” such as caring for our health, finding a life partner, and setting up home, we yearn for more than “minimum viable.” Yet picturing and pursuing perfection within a material framework can be like the cartoonish trope of a carrot hanging from a stick in front of a mule: It dangles enticingly before our eyes, a perfection we can never quite reach.

A far more trustworthy pathway to experiencing good is turning our attention away from what we don’t seem to have and developing the spiritual sense that Jesus exemplified. The textbook of Christian Science by Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” describes this spiritual sense as follows: “The Christlike understanding of scientific being and divine healing includes a perfect Principle and idea, – perfect God and perfect man, – as the basis of thought and demonstration” (p. 259).

This points us to a perfection already at hand: perfect Love, God, and the perfection of all as Love’s expression.

We each have the inherent capacity to grow in this understanding of “scientific being” and prove that this spiritual sense brings progress in suitable and satisfying ways. Primarily this means increasingly embodying spiritual characteristics – such as grace, wisdom, integrity, and forgiveness – by which we bless others. But basing thought and demonstration on “perfect God and perfect man” also meets our own needs practically.

Divine good is practical. We can’t help but see this when our thought is imbued with the spiritual sense of perfection, as evidenced in the healing that flowed to those whose lives were touched by Jesus, as recorded in the Bible. As Science and Health says in regard to “the perfect model” that we should hold in thought continually, “Let unselfishness, goodness, mercy, justice, health, holiness, love – the kingdom of heaven – reign within us, and sin, disease, and death will diminish until they finally disappear” (p. 248).

So when it comes to what we hold in consciousness, perfection is far from the enemy of good: It is essential to perceiving and experiencing goodness. We need to agree to disagree with thoughts that deny our real, God-reflecting consciousness and nature – for instance, thinking we’re defenseless or impulsive or believing ourselves beholden to a sensual view of ourselves and others. Listening instead for “the Christlike understanding” that Jesus exemplified, we increasingly see the perfection he saw in all. This right view reveals the good we need as already present.

But is the good revealed perfect? In the afterglow of regaining health, meeting the right companion, or finding an abode in this way, it can be tempting to think so. It’s certainly true that there’s an amazing precision and abundance to the blessings that arise from such understanding. Jesus proved this when his clear sense of God’s perfection brought to light food for thousands when provisions appeared to be scarce (see John 6:5-14) – to name just one example.

Yet perfection belongs solely to Spirit, God. Matter is incapable of perfection or permanence. A large crowd tracked Jesus down the day after he fed the thousands. He pointed them to “the meat which endureth unto everlasting life, which the Son of man shall give unto you” (verse 27). Surely that meat was the Christlike understanding evidenced in the wonderful works they saw Jesus accomplish – works he urged his followers to emulate.

We can gain a little more of this Christlike understanding daily. While we rightly feel ongoing gratitude for the good in our lives, it’s the spiritual understanding underlying that good that is perfect and permanent. Discerning this deeper truth doesn’t lessen our love for what we have; it heightens and stabilizes it. Time and again, I’ve seen how pausing to perceive the true, spiritual nature of some good in my life brings out the best in its present expression while also keeping my heart open to the growth and evolution of just how that good is expressed over time.

Perfection is our friend if we seek and find it where it forever exists, in our divine source, Spirit, God – as Jesus did and encouraged us to do. Then we can gratefully prove just how good the good is that flows from keeping those perfect models uppermost in thought.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Jan. 8, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Petal power

A look ahead

Before you leave, we have one more offering you might like. President Joe Biden’s name is not on the Democrats’ ballot in the New Hampshire presidential primary. For a quick read on why, click here.