- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 17 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

One email you won’t mind getting

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

I got a pleasant surprise in my email inbox last week: A newsletter from Monitor reader and friend Amanda Ripley. As a journalist herself, she’s written about her appreciation for what the Monitor does, and we’ve written about our appreciation for what she does.

Her newsletter is as lovely as you would expect – about how journalism can build dignity, agency, and hope. Her top story was close to my heart (I’m a former Afghanistan correspondent). It’s about the extraordinary achievements of a platoon of Afghan women. I hope you’ll give it a read.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Weed: Taking stock 10 years after legalization began

Ten years after individual states began legalizing marijuana, signs of a shift in perspective surface. Behind the growing commercial presence lie people’s preferences, states’ power – and unanswered questions.

In Denver, they queued for hours in sleet and snow, waiting to buy pot. It was Jan. 1, 2014, and Colorado had become the first state to legalize recreational marijuana for adults. For the people who waited in line that morning, it was a historic moment to savor.

Ten years on, the whiff of pot is pervasive in parts of Denver. And the stigma of shopping at the dispensaries that dot the streets has largely gone up in smoke, as cannabis takes its place alongside other legal intoxicants.

That sense of normalization extends beyond Colorado. More than half of Americans now live in jurisdictions that have legalized recreational cannabis, while 37 states and the District of Columbia provide access to medical marijuana. And a more than $30 billion legal industry has become a significant employer in some states.

Opponents say, among other concerns, that legalization leads to greater cannabis use by adolescents and a deterioration in mental health. Studies have found associations between habitual youth usage and mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and psychosis.

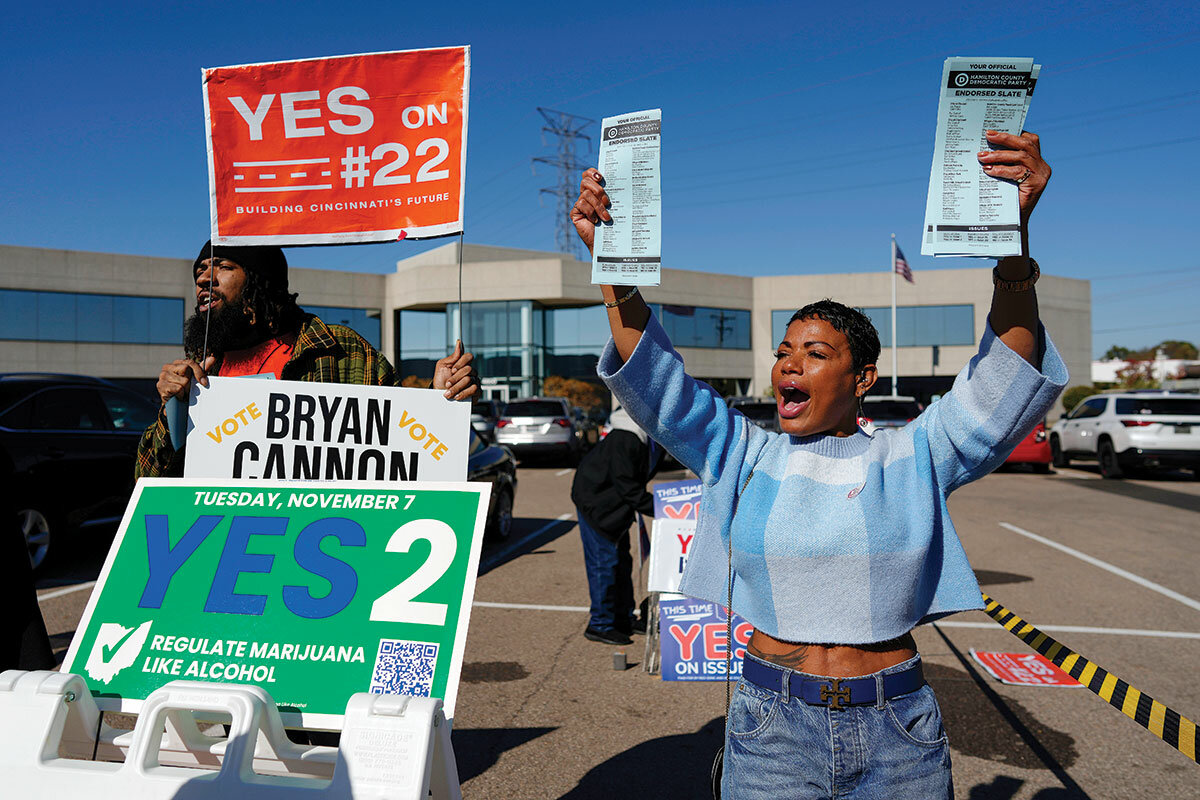

Yet, while a handful of smaller conservative states rejected pro-cannabis ballot measures in 2022, there’s no sign of a wider national rollback. In November 2023, Republican-run Ohio voted to become the 24th state to legalize pot. As Pat Oglesby, who teaches a cannabis policy class at the University of Virginia says, “I think the momentum is for a loosening, not a tightening, of state marijuana sales.”

Weed: Taking stock 10 years after legalization began

In Denver, they queued for hours in sleet and snow, waiting to buy pot. It was Jan. 1, 2014, and the unthinkable had happened: Colorado had legalized recreational marijuana for adults, the first state to breach the federal prohibition on nonmedical sales. For the people who waited in line that morning, it was a historic moment to savor.

But that didn’t make Ricardo Baca’s job easy. As The Denver Post’s cannabis editor – another first – Mr. Baca headed out to cover the first day of legal sales, trailed by a film crew shooting a documentary. When customers lined up outside newly licensed cannabis dispensaries saw the cameras, many pulled their sweaters and jackets over their faces to avoid being identified. “People were very uncomfortable going on the record,” says Mr. Baca.

Colorado state regulators had their own concerns about what the United States, including lawmakers in Washington, would see on TV during those first days. Licensed sales were now legal. But smoking pot in public wasn’t, and Coloradans were asked to respect the rules, which nearly all did after making their purchases, says Mr. Baca. “They weren’t lighting up on the streets.”

Ten years on, the whiff of pot is pervasive in parts of Denver, though the ban on public consumption remains. The stigma of shopping at the dispensaries that dot the streets has largely gone up in smoke, as cannabis takes its place alongside other legal intoxicants. “More professionals are using it,” says Brian Vicente, a lawyer who co-directed Colorado’s 2012 campaign for legalization via a ballot initiative. “People are not parking three blocks away from their store because they don’t want to have their license plate written down.”

That sense of normalization, of a page turning on an era of pot prohibition, extends beyond Colorado. More than half of Americans now live in jurisdictions that have legalized recreational cannabis, while 37 states and the District of Columbia provide access to medical marijuana, which was pioneered by California in 1996. A more than $30 billion legal industry has become a significant employer in some states; Mr. Baca now runs his own cannabis-focused public relations agency, Grasslands, in Denver.

This wave of state legislation has tracked public opinion on marijuana in a sea change comparable to the shift in approval of same-sex marriage. In 1991, only 17% of Americans favored the legalization of cannabis, according to Pew Research Center. In 2022, 88% of respondents told Pew it should be legal, either for medical and recreational use or for medical use only, while only 10% said it should be illegal.

Illegality is still federal policy: Cannabis is a controlled substance, and producing and trafficking it is a crime. But the Biden administration is reviewing the drug’s classification and has begun pardoning thousands of people convicted by federal courts for simple cannabis possession, citing racial disparities in arrests and prosecutions and the negative impacts of criminal records on offenders’ employment, banking, and housing prospects.

These disproportionate harms on minority communities sparked Mr. Vicente’s initial interest in the issue, he says. “But it did not poll well in Colorado in 2012 for us to talk about the drug war or racial discrimination and marijuana arrests,” he says. “Nobody really cared.”

So the pitch to voters was that legalization would allow Colorado to regulate, inspect, and tax a product that would be safer for adults to consume. A similar ballot initiative also passed in 2012 in the state of Washington, where the legal sale of pot began in July 2014.

Opponents warned that legalization would lead to greater cannabis use by adolescents, higher overall levels of abuse, a deterioration in mental health, and more impaired driving. A decade on, those warnings have continued as studies have found associations between habitual youth usage and mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and psychosis. High-potency concentrates, which have surged in popularity, appear to exacerbate these risks. Critics say these negative impacts are downplayed by politicians who talk up cannabis revenues and jobs.

“On every spreadsheet there’s two sides. We can talk about [tax] revenue all you want. ... But nobody wants to talk about the other side, the health cost and the mental health cost,” says John Jackson, the city manager in Greenwood Village, a wealthy Denver suburb.

Still, beating the drum about the dangers of cannabis can be tough when policymakers are battling an epidemic of overdoses on stronger drugs, primarily fentanyl, that took more than 100,000 lives in 2022. As a drug, cannabis is less deadly than alcohol or tobacco. Tens of millions of Americans already use it, both to get high and to treat anxiety, pain, and depression.

While a handful of smaller conservative states rejected pro-cannabis ballot measures in 2022, there’s no sign of a wider national rollback. In November 2023, Republican-run Ohio voted to become the 24th state to legalize pot. “Nobody has retracted or retreated,” says Pat Oglesby, a tax lawyer who teaches a cannabis policy class at the University of Virginia. “I think the momentum is for a loosening, not a tightening, of state marijuana sales.”

A century after the U.S. gave up on alcohol prohibition as a failed social and economic experiment, it may be edging closer to doing the same with cannabis. But it’s likely to be a zigzag path strewn with potholes.

Behind a papered-over storefront in a small shopping plaza, Christine Richardson pilots a wheelbarrow of discarded wallboard over an uneven floor. Dust floats in the air and clings to her black sweatpants and sneakers and to her bleached blond ponytail. On her way to the dumpster out back, she sways her hips to the Mexican pop music echoing off the bare walls.

When Ms. Richardson looks around the half-built store in Loudonville, a well-heeled suburb of Albany, New York, she pictures how it will look as a cannabis dispensary: wooden cabinets, artful lighting, granite countertops, elegant chairs. “I want it to be more than a pot shop,” she says.

In June she signed an initial lease. A month later, she received her provisional state cannabis license. Then in August she got a call from her landlord: The next-door unit, a former pizza restaurant, was available. Did she want it? She did, so the internal walls were knocked down to create a 4,200-square-foot retail space.

Her plan was to open by Halloween. But New York’s cannabis rollout was put on hold in August by a judge hearing a lawsuit that alleged discrimination in the licensing process, which meant that Ms. Richardson couldn’t open her store, even as the renovation bills kept coming. “Every time I turn around, it’s another 15 ... , 18 ... , $20,000,” she said last fall.

When the New York State Legislature voted in 2021 to legalize recreational pot, many foresaw a financial bonanza, with the state being second only to California in its potential market size. New York’s ambitions went further, though, as Democratic lawmakers in Albany vowed to prioritize social equity in awarding licenses and to invest in communities that had borne the brunt of criminal prohibition.

By doing so, New York joined a wave of blue states like Massachusetts and Illinois that set progressive goals for pot legalization in the form of preferential licensing for businesses run by racial and ethnic minorities, women, disabled veterans, and people with prior cannabis convictions. Some also provide support in raising capital and finding real estate – and even in pot cultivation, which has to be set up in each state, since interstate commerce remains illegal.

In keeping with New York’s preferential approach, Gov. Kathy Hochul had announced in March 2022 a pivot on store licensing: Applicants with past cannabis convictions would go to the front of the line.

Ms. Richardson was all ears. “The minute I found out about the program, I started looking” for retail space, she says.

As a child raised outside Woodstock, New York, in the 1970s, she was surrounded by pot. “I grew up on cannabis farms, not knowing any different,” she says. In 2009, she was arrested at her house, where she had been growing cannabis to sell. Convicted of a felony, she got five years of probation. That led to her losing her nursing license and her house, so she moved to Albany to start over. “You can’t get a job. No one will hire you as a felon,” she says. Eventually she got into real estate management, a career that gave her a leg up in opening a cannabis dispensary.

Once she was allowed to open, that is.

New York pretty quickly became a cautionary tale of political and regulatory missteps that ended up sidelining the very people who were supposed to benefit from progressive policies. “NY cannabis license system broken, say idiots who broke it,” fumed a New York Post editorial in November 2023.

The August lawsuit, filed by four disabled veterans, accused New York of violating its own law in licensing cannabis offenders before other social equity applicants. In late November, the state’s Cannabis Control Board agreed to settle the lawsuit, ending the injunction on approved dispensaries that were ready to open.

By early January, Ms. Richardson was waiting for inspectors to approve her finished store, which she has christened Royale Flower, so that she can open.

But the four-month injunction and previous bureaucratic delays in licensing have stunted New York’s legal cannabis industry: At the start of 2024, some 34 stores were open for in-person sales in a state of 20 million people. And by botching the rollout of legal pot stores, New York left a vacuum to be filled. To the frustration of license holders and anti-pot campaigners alike, well over a thousand smoke shops selling weed without permission have popped up, primarily in New York City.

Most consumers don’t know the difference between a licensed dispensary, whose cannabis products are tested and taxed, and the bootleg stores that have proliferated, says Debra Borchardt, executive editor of Green Market Report, a marijuana industry publication. “They don’t know, or they don’t care,” she says.

Authorities have been slow to crack down on these shops, which also sell tobacco, vapes, and pot paraphernalia. And the state doesn’t necessarily enforce regulations against the advertisement of tobacco and vaping products within 500 feet of a school. In 2022, photojournalism students at the Bronx Documentary Center began mapping the rule-flouting smoke stores in their neighborhoods. Some were only a block or two away from a school gate. “Every corner has a smoke shop,” says Itzel Robles, a student involved in the project.

The students also uncovered stores selling pot to Bronx high schoolers, despite the minimum age of 21 for purchasing marijuana. Educators have complained that more students are getting high before or during school. It’s also harder for teachers to detect the use of vape pens and cannabis edibles – gummies, candies, and drinks – compared with catching students smoking joints.

The reluctance of authorities in New York to strike hard against illicit pot stores is perhaps understandable. After all, the premise of legalization is that the war on cannabis, which began under former President Richard Nixon’s administration, was a misguided policy that was costly to enforce and unjustly executed.

Since legalization, states like Colorado have recorded sharp drops in cannabis-related criminal offenses. But the racial disparity in who is arrested has proven more sticky. Black people are still more than three times as likely to be arrested for possession than white people, who use cannabis at similar rates, according to a 2020 report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Michael Diaz-Rivera doesn’t know why he was pulled over by police in Colorado Springs in 2006, a stop that led to his arrest and a felony conviction for pot possession. But he suspects that a white teenager caught with weed in the same situation would have gotten away with a caution. “I’m a Black guy. I get pulled over with a car full of Black guys,” he says.

Mr. Diaz-Rivera, who is biracial, did have a reputation, though. He sold weed in high school and acted like a “knucklehead,” he says. The first tattoo he ever got, on his right bicep, reads “Money Mike,” his pot-dealer nickname.

When Colorado began to draft its rulebook for a legal cannabis market, nobody argued that former offenders like Money Mike should be invited to participate in the name of social justice, says Sam Kamin, a law professor at Denver University who served on an implementation task force under then-Gov. John Hickenlooper. “It wasn’t on our radar screen,” he says.

For one thing, Colorado wasn’t sure what the federal government would do when pot went on sale. But it knew that the legal market needed to be kept separate from the illegal trade, so it seemed prudent to license only operators with clean records, says Professor Kamin.

A decade on, Colorado’s cannabis industry is mostly white-owned, to the frustration of Black and Latino entrepreneurs. One challenge is that urban zoning rules make it hard to find a new retail site, which locks in the advantage of existing licensees. New entrants also face a saturated market: Cannabis sales in Colorado have fallen for the last two years.

In an effort to diversify, Denver overhauled its regulations in 2021 to reserve all new cannabis licenses for social equity applicants until 2027. That’s how Mr. Diaz-Rivera became the owner of a delivery company, Better Days, that partners with dispensaries in Denver. “Delivery was just the easiest entry because I didn’t have to have a retail location. I could jump in,” he says.

Social equity programs aren’t a sure bet, given the risk of starting any new business. Mr. Diaz-Rivera’s delivery license was the third issued in Denver; the first two delivery companies have gone out of business. So far, Denver has licensed 32 cannabis firms for social equity applicants, including cultivation and hospitality businesses.

But another justice-related reform holds more promise: expunging past convictions. States like Illinois offer automatic clearance for minor offenses, while others require offenders to petition courts. California has faced criticism, however, for failing to implement its expungement program. A 2021 Rand Corp. study found that racial and ethnic minorities stand to benefit most from these programs, far more than they could expect from preferential cannabis employment policies, given the difficulties faced by former offenders trying to find work, housing, and loans.

Mr. Diaz-Rivera’s state conviction has been sealed, though he’s still on an FBI database. For now, he’s focused on building his business. He has three young children and frets about how much time he’s away on deliveries. As to how he got into the business, and his identity as Money Mike, those aren’t topics he wants to bring up at home.

“If ... ,” he says, then pauses. “When the business is successful and they’ve realized all that I’ve been able to do for the family because of this cannabis business, I’ll be able to talk to them about my story and the felony,” he says.

He still smokes pot. When his children are older, he plans to talk to them about responsible use, reasoning that he can’t counsel abstinence. “But I don’t think I’ll be happy if my kids are smoking in high school. I don’t think I’ll want that,” he says.

Critics say legal cannabis sales to adults leads to greater teenage consumption. But while some studies support this claim, others have found no association between legalization and teen use. A biennial survey by Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment of over 100,000 high school students showed little change post-legalization, with around 1 in 5 admitting in 2019 to using marijuana in the past 30 days. This share declined to 13% in 2021 amid pandemic-related school closures, mirroring national survey findings.

What is clear, though, is a steady rise in consumption nationally by young adults over the last decade. A federally funded study in 2021 found that 11% of respondents ages 19-30 reported daily or near-daily use, up from 6% in 2011, while 43% reported use in the last 12 months. Residents in states where recreational cannabis is legal are more likely to consume.

Cannabis isn’t a killer like alcohol, which is responsible in the U.S. for 140,000 deaths a year. Citing the toll of alcohol consumption, advocates of legal pot seek a more moderate view of cannabis use. Society has normalized casual drinking, they argue, while framing pot as a binary choice between abstinence and abuse. “You can be functional under the influence of cannabis,” says Emma Thurston, who manages Cal Verde Naturals, a dispensary in Belmont, Massachusetts.

A former town board member and mother of three, she considers binge drinking in her affluent suburb of Boston a greater hazard than underage pot consumption. “Our role as parents is to talk freely and honestly about what the dangers are” of all intoxicants, she says.

But while alcohol’s risks are well understood, medical experts warn that habitual cannabis use by young people whose brains are still developing affects mental health in ways that researchers are only beginning to uncover. “What we’re worried about is what we call years of productive life lost,” says Sion Kim Harris, co-director of the Center for Adolescent Substance Abuse Research at Boston Children’s Hospital.

A large, long-term study in Denmark found that young men who became dependent on cannabis were at much greater risk of schizophrenia. Researchers estimated that cannabis use disorders among men ages 21-30 may have led to 30% more schizophrenia cases and noted that the proportion had risen in line with higher cannabis potency.

We don’t yet know the full picture for college-age Americans using cannabis today, says Dr. Harris. “It requires more time to see what happens to young people.”

One thing we do know is that pot is more potent today: Concentrations of THC, the primary psychoactive ingredient, average 15%, up from 4% in 1995, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. For some cannabis concentrates, which are vaporized or inhaled over high heat, THC levels can exceed 90%.

Ben Cort, who runs an inpatient treatment program in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, for men dealing with addiction and mental illness, has seen an increase in patients with cannabis disorders. He says that high-potency concentrates, which he compares to crack cocaine, represent “the industrialization of a plant” by producers focused on frequent users who are their best customers.

In 2021, Mr. Cort helped organize hearings in Colorado’s Legislature to lobby for a potency cap on cannabis. Lawmakers didn’t take up the proposal, though they enacted legislation to lower daily limits on medical marijuana as a curb on abuse. Other states, including Washington and California, are considering imposing caps on the strength of cannabis.

But the cannabis industry has pushed back. John Moynan, the CEO of Slang Worldwide, a Colorado-based manufacturer of cannabis products, says many consumers use THC levels as a proxy for quality since branding is so new. “The concentrates market does really well because it’s a very potent product” for the price, he says.

Mr. Moynan says regulators should focus on testing and labeling products, not on restricting what is available. “Everybody is able to be a fully informed and safe consumer,” he says.

Another policy tool is taxation. New York and Connecticut levy excise taxes on cannabis that increase with potency, just as liquor is taxed at higher rates than beer. But regulators have also found that high taxes on cannabis, while healthy for state coffers, can make illegal weed more attractive. A combination of high taxes, stringent regulations, and a lack of dispensaries has hamstrung California’s legal recreational market, while illegal producers are thriving.

California faces a law enforcement challenge in shutting down its entrenched illegal industry, says Mr. Oglesby, the tax lawyer, who has advised the state’s regulators. “Cops don’t want to arrest people,” he says. “And juries might not convict them.”

Even where legal pot wins out, states may struggle to regulate a fast-growing industry that, like alcohol and tobacco, makes the bulk of its profits from habitual users and is minded to resist public health measures, such as potency caps. “We don’t have a good model in this country for regulating a habit-forming drug being sold on a commercial basis,” says Professor Kamin.

Some states have mulled a public distribution model, similar to state-run liquor stores, so as to control pricing and availability. But none have put this into practice, instead letting the market lead the way. And that, says Mr. Cort, is a recipe for “Big Cannabis” and its lobbyists to bend policy to its ends and put profit before health, just as Big Tobacco did for decades. “We’re the country that supersizes our Big Macs,” he adds.

From Lupe Casias’ front door on the windblown main street of Sedgwick, Colorado, the town’s three cannabis dispensaries are easy to spot. Their bright colors and signage stand out on a street with limited amenities: a post office, liquor store, hair salon, bar, and town hall, along with Ms. Casias’ bed-and-breakfast in a renovated bank building.

That a sleepy town of 170 people on the plains of northeast Colorado has three pot stores is a function of geography, regulation, and desperation.

Sedgwick is the closest legal cannabis market for several nearby states. On busy days, drivers with out-of-state plates – many from Nebraska, which has no legal recreational or medical marijuana – wait for stores to open at 8 a.m.

After Colorado legalized marijuana in 2014, local communities could decide whether to opt in or opt out. In this rural corner of the state, there were almost no takers. Common arguments are that selling pot leads to an increase in social disorder, traffic fatalities, underage cannabis use, and demand for public health services.

But Sedgwick, a farming town fallen on hard times, was willing to consider the option because its finances were so dire. In 2013, it collected less than $20,000 in taxes. “We couldn’t pay our bills,” says Danny Smith, the current mayor.

So the first dispensary opened in 2015 in a building owned by Ms. Casias. By 2018, the town had annual revenues of $245,000. The next year it decided to issue two more retail licenses, and revenues have since exceeded $1 million.

Thomas Schmittinger, a former Army Ranger, opened his store in 2020 on the site of Sedgwick’s gas station that closed in the 1960s. Before cannabis, “the town was completely dead,” he says. Now the city is investing in water and sewage upgrades, while building its reserves, virtually all paid for by a 5% tax on cannabis sales. New residents are bidding up houses. “People are starting to have some pride in the town,” says Ms. Casias.

Some residents still complain about the pot stores. But a bigger worry is what would happen if Sedgwick had competition for its cannabis dollars, as border towns near New Mexico did after that state legalized pot in 2021. Should Nebraska end its prohibition on legal pot, many of Mr. Schmittinger’s regulars could shop closer to home. “There’s a timetable on this,” he warns. “We only have a short amount of time to make money in Sedgwick.”

Nebraska may not be the deciding factor. In September, the U.S. Senate Banking Committee approved a bipartisan bill to enable federally regulated banks to finance marijuana businesses, a victory for the industry. Some see this as a step toward eventually allowing interstate commerce, which would lead to consolidation across the industry and make border dispensaries dispensable.

But it’s also possible, say analysts, that cannabis follows the path of alcohol after federal prohibition ended in 1933, with state and local laws creating a patchwork of wet and dry counties that continues to this day. Mississippi was the last state to end prohibition – in 1966.

And just as legalizing pot doesn’t mean an end to illegal pot, the legacy of alcohol prohibition lingers. “They’re still making moonshine in Kentucky, and that’s after 90 years,” says Robert Solomon, co-chair of the Center for the Study of Cannabis at the University of California, Irvine.

For now, the availability of recreational cannabis is up to states and to local communities like Sedgwick. Tax revenues there have trended lower since 2021, but the town has plenty in the bank, and the visitors keep arriving for a taste of legal weed. “As long as we can milk the cows, we’re going to do it,” says Ms. Casias.

Today’s news briefs

• Supreme Court on immigration: The Supreme Court of the United States agrees to temporarily let Border Patrol agents cut the razor-wire fencing that Texas officials placed along part of the state’s border with Mexico to deter illegal border crossings.

• San Diego floods: Flash floods inundate homes and overturn cars in Southern California as a whopping 3 inches of rain falls near San Diego.

• California professors strike: A union representing 29,000 professors and staff at the California State University system reaches a tentative deal to call off a five-day strike after one day.

• Dixville Notch votes: The six voters of the New Hampshire community choose Nikki Haley. The town has a tradition of first-in-the-nation primary voting that dates back to 1960, with the results typically announced just a few minutes after midnight.

When your job interviewer’s initials are AI

Next, we have two stories about artificial intelligence and how it is changing hiring and learning. First, we look at the trend of companies embracing AI hiring tools despite flaws in machine-based interviewing and charges of discrimination. Can machines truly pick the best workers?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Everybody worries that smart computers will take over jobs and get people fired. What’s less visible, but perhaps equally important, is that they’re also playing a role in who gets hired.

Artificial intelligence is spreading into the hiring process despite widespread public skepticism. Innovations in automated interviewing are happening so quickly that governments are struggling to keep up with ground rules. Left unresolved are larger ethical questions, but even these are rapidly becoming moot as companies rush to embrace the technology.

For large organizations, the advantages are obvious. Swamped with applicants for beginner-level positions, large companies are eager to streamline the hiring process. Small companies can benefit from AI assistance, too. But while AI could prove to be less biased than human interviewers, it’s not foolproof.

Amazon disbanded an AI résumé-screening system in 2018 after finding the technology discriminated against women. Last September, iTutorGroup agreed to pay $365,000 to settle a federal lawsuit claiming its system automatically rejected older applicants for tutor positions.

“I think the positives outweigh the negatives in the big picture,” says Jeanine Dames, director of Yale University’s career strategy office. “It gives so many more people the opportunity” to be considered by quality employers.

When your job interviewer’s initials are AI

Everybody worries that smart computers will take over jobs and get people fired. What’s less visible, but perhaps equally important, is that they’re also playing a role in who gets hired.

Artificial intelligence is spreading into the hiring process despite widespread public skepticism. Innovations in automated interviewing are happening so quickly that governments are struggling to keep up with ground rules. Left unresolved are larger ethical questions, such as: Can we trust machines to judge human talent and potential? Will AI interviewers be less biased than human ones?

Such questions haven't stopped companies from rushing to embrace the technology, at least for entry-level positions and internships, despite drawbacks of machine-based interviewing and previous problems with discrimination.

“I think 100% of our students will encounter AI whether they know it or not” in the interview process, says Steve Rakas, executive director of the Masters Career Center at Carnegie Mellon University’s business school in Pittsburgh.

Among employers considering the technology, “it went from fear to FOMO, meaning fear of missing out,” says Patrick Morrissey, chief customer officer of HireVue. The talent-search technology firm in South Jordan, Utah, counts 60% of Fortune 100 companies and 13 federal agencies as clients.

For large organizations, the advantages are obvious. Swamped with applicants for beginner-level positions, large companies are eager to streamline the hiring process. For example, Goldman Sachs says it is now using AI to help screen the tidal wave of résumés it receives for its high-paying, entry-level spots. (In 2022, the bank says, it received 236,000 applications for 3,700 positions in its internship program.)

Small companies can benefit from artificial intelligence assistance, too.

In 2016, Michelle Zhou and her co-founder at Juji, an AI hiring startup in San Jose, California, spent 2 ½ weeks sifting through 700 applications for one intern position. Two years later, having molded their AI analytics into a full-blown, automated interviewing system, the pair used it to judge talent and pick candidates for follow-up interviews. The process was finished in a couple hours.

Juji’s text-based technology not only speeds up evaluation of candidates, but also is less biased, Ms. Zhou contends. Before the AI interviewing system was in place, she and her colleague used shortcuts to sort candidates, such as the reputation of the applicants’ alma maters. When they switched to the AI system, it chose “one of the people we would never have picked up, because they came from one school we had never heard of,” she says.

Several universities, already training students for live job interviews, now help them handle AI video interviews, too.

“The tricky part of the AI interviewing [is] a timer,” says Jeanine Dames, director of Yale’s career strategy office. So as a candidate is answering something like “tell me about yourself,” they are also watching the time tick away. When the counter reaches zero, the recording stops.

“It is really awkward to sit there and talk to yourself and a computer,” says Hank Michalik, a Yale student who had an AI interview for a finance internship last spring. “It is dehumanizing.”

The computer systems evaluate various skills of candidates, such as their attention to detail or their ability to work with others. If a company is looking for multitaskers, HireVue can introduce a game during the interview in which, while answering questions, the candidate has to watch a volume indicator on the monitor and click when it falls below 90%. The system is measuring what the company calls “human potential intelligence.”

“It’s not about the degree that I got 30 years ago in university; it’s about what am I capable of,” says HireVue’s Mr. Morrissey. “So eliminating degree requirements and just focusing on skills and capabilities and competencies is very much where the world is going.”

While AI could well prove to be less biased than human interviewers, it’s not foolproof.

Amazon disbanded an AI résumé-screening system in 2018 after it found the technology discriminated against women. Last September, iTutorGroup agreed to pay $365,000 to settle a federal lawsuit claiming its system automatically rejected older applicants for tutor positions.

In 2021, the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission began monitoring AI interviewing systems for bias and last May issued a technical document to help companies avoid job discrimination. And this past July, New York City passed a law requiring companies to perform annual audits of their AI hiring and promotion systems for bias. In October, President Joe Biden issued a wide-ranging executive order on AI that called for principles and best practices to keep companies from “evaluating job applications unfairly.”

While the automated hiring systems have relied on other forms of artificial intelligence to analyze candidates for some time, the arrival of generative AI a year ago has accelerated innovation in interviewing technology. In December, for example, Juji unveiled a system that automated the interviewing of references given by candidates. The system not only judges whether the references offer an unbiased view of the person, but also summarizes all the interviews into a single document for companies to assess.

Now, a couple of Juji’s clients are trying out systems that would use the technology not just for entry-level positions, but also for higher ones. Companies emphasize that humans, not machines, make final hiring decisions.

The public remains skeptical of the technology. By a 71% to 7% margin, respondents to a Pew Research Center survey last spring opposed using AI to make final hiring decisions, and 41% opposed using it at all to review job applications. A September poll for the American Staffing Association found that just under half of employed people looking for a new job thought the technology would be more biased than human interviewers.

“I think the positives outweigh the negatives in the big picture,” says Ms. Dames of Yale. “It’s easier for a large organization to recruit from 200 universities around the world, even if they can’t visit 200 universities. [And] a small organization could use a large screening tool and invite applications from thousands of students. ... It gives so many more people the opportunity” to be considered by quality employers.

Why some teachers embrace AI in the classroom

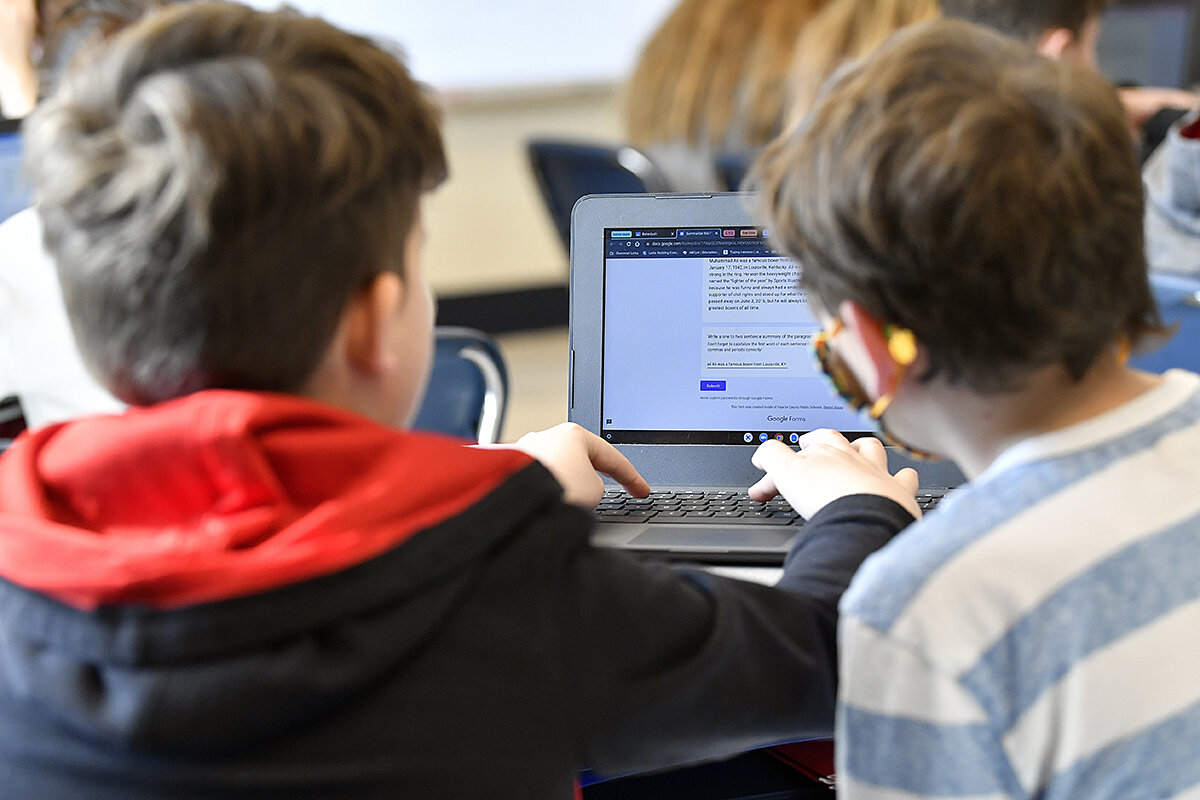

In schools, educators are trying to balance concerns about artificial intelligence with how to prepare students for using it in the future. What does teaching look like when AI is part of the curriculum?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In Georgia, educators are thinking more about what students should be learning about artificial intelligence. Their vision has started to become a reality. The youngest learners are having conversations about household appliances, such as Amazon’s Alexa. High schoolers can now take classes that culminate in using AI to solve real-world problems.

“What we’re really trying to do is teach our students how to be critical thinkers,” says Sallie Holloway, director of artificial intelligence and computer science for Gwinnett County Public Schools.

School-based computer labs once seemed futuristic. Now the internet is everywhere, and the next frontier – AI – is seeping into learning environments. ChatGPT’s debut more than a year ago brought ongoing concerns about cheating and the tool’s ability to mislead students. But some educators also see it as an opportunity for innovation.

Everything from smartphone apps to collision-avoidance systems on cars use AI, with experts saying that it will soon be embedded in daily life.

“It’s not just like textbook work,” says Carter Watkins, a senior at Gwinnett County’s Seckinger High School. “You’re putting your thinking cap on.”

Why some teachers embrace AI in the classroom

What if instead of being wary about artificial intelligence, schools were embracing it?

In Georgia, educators in a district near Atlanta are thinking more about what students should be learning about AI. Their vision has started to become a reality. The youngest learners are having conversations about household appliances, such as Amazon’s Alexa. High schoolers can now take classes that culminate in using AI to solve real-world problems.

“What we’re really trying to do is teach our students how to be critical thinkers,” says Sallie Holloway, director of artificial intelligence and computer science for Gwinnett County Public Schools.

School-based computer labs once seemed futuristic. Now the internet is everywhere and the next frontier – AI – is seeping into learning environments. ChatGPT’s debut more than a year ago brought ongoing concerns about cheating and the tool’s ability to mislead students. But some educators also see it as an opportunity for innovation.

David Touretzky chairs the Artificial Intelligence for K-12 Initiative, which began in 2018 after he realized computer science standards had barely mentioned the burgeoning AI field. The group has been developing instructional guidelines, establishing what students should know about AI, and how they should be able to use it.

Everything from smartphone apps to collision-avoidance systems on cars uses AI. And with the emergence of large language models like ChatGPT, which rely on vast amounts of data, AI will become even more embedded in daily life, Mr. Touretzky says, explaining the need for related education.

The Artificial Intelligence for K-12 Initiative has been piloting an AI elective course in some Georgia middle schools that includes topics such as autonomous robots and vehicles and how computers understand language and make decisions.

“The way kids relate to AI is going to depend a lot on how large language models find their way into our society,” says Mr. Touretzky, who is a research professor in computer science at Carnegie Mellon University. “We don’t understand yet what that’s going to look like.”

Preparing for the future

In October, the Center on Reinventing Public Education found that only two U.S. states – California and Oregon – had issued specific guidance surrounding AI education.

Officials from Gwinnett County Public Schools liken the academic imperative to driving a car. Before people get behind the wheel, they need to know the rules of the road and the basics of vehicle maintenance. Artificial intelligence necessitates a similar education, they say.

An AI-ready student, as defined by the district, would be exposed to, if not well versed in, the areas of data science, mathematical reasoning, creative problem-solving, ethics, applied experiences, and programming. At a pilot group of schools, the district has embedded this learning framework in kindergarten through 12th grade classrooms.

“Students are hearing every day about how pervasive AI is and how it is in every industry,” says Ms. Holloway of the work she coordinates. “So I think they are interested to know more and really prepare themselves for their futures.”

Carter Watkins, a senior at Seckinger High School in Buford, part of the Gwinnett district, says the inclusion of AI throughout his core subjects has made him more eager to attend school. He particularly enjoyed a lab activity in a physics class, in which students leaned on AI to help determine which remote control car moved faster with different batteries.

“It’s not just like textbook work,” he says. “You’re putting your thinking cap on.”

As an aspiring business major who wants to go into sports marketing, Carter says the AI skills are helping him become a “more well-rounded individual.”

“AI is not all bad”

With or without official guidance, some educators are already displaying how it can be used for good.

At Highlands Ranch High School outside of Denver, Principal Chris Page Jr. used artificial intelligence to develop clues for a homecoming-related scavenger hunt. He drew inspiration from AI and tinkered with the suggestions.

After students solved the mystery, he let them in on his secret. Dr. Page says he wants his staff and students to know there are benefits to AI if it is used correctly – just like prior technology that seemed unnerving at first.

“AI is not all bad,” he says. “What we know to be true is there are always educational shifts, and a lot of those are technological shifts in education.”

Experts say weaving AI into lesson plans will be a gradual process, partly because teachers need to learn the technology, too. An Education Week survey conducted in the fall found that two-thirds of teachers had not used AI tools in the classroom. Of those, more than a third had no plans to use it, while about another third envision using it soon.

When educators at Dr. Page’s school use AI in the classroom, the lessons mostly familiarize students with its capabilities and drawbacks, he says. Teachers, for instance, may have AI generate a historical narrative and then have students dissect it to determine what’s true and false.

The “research-minded” project, he says, allows students to “truly become historians because that’s what historians do.”

In the Los Angeles area, a charter network called Da Vinci Schools has deployed AI in the form of Project Leo. The platform melds instructional standards with student interests, producing project ideas that personalize learning, says Steve Eno, who teaches mechanical engineering and is the director of Project Leo.

He says one student is devising a “trick analyzer” using AI technology that will offer recommendations about how skateboarders can improve their form.

“I don’t think every kid is going to be interested in using AI to build,” Mr. Eno says. “I do think students need to know how it works and what’s possible with it.”

Sometimes Project Leo spits out ideas either that are bad or that students don’t like. That’s OK, he says, because it’s showing them the imperfections surrounding AI. But when an AI-generated project idea sparks a student’s imagination, it leads to more engagement and, ultimately, a portfolio of work that can lead to future careers, Mr. Eno says.

“They need to be excited,” he says. “They need to be joyful, and then they’ll actually learn the stuff.”

Iran and Pakistan: Can trust be rebuilt?

It took only 48 hours and two rounds of missiles for trust to break down between Iran and Pakistan. Understanding why Iran struck its neighbor – and what each country can do to boost security – will help in working to restore lost trust.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Iran and Pakistan have announced that ambassadors of both countries will “return to their respective posts” this week. That marks the end of a diplomatic crisis that began when Iran launched an unexpected missile and drone attack Jan. 16 in Pakistan’s sparsely populated Balochistan province.

Iranian officials claimed the operation was aimed at neutralizing members of an obscure militant group, but commentators in Pakistan remain skeptical. “I think that it was a blunder from sections of the Iranian deep state who tend to be trigger-happy,” says Mushahid Hussain Syed, a Pakistani senator and foreign policy expert, noting that Iran is facing pressure from the United States and Israel over its support of Hamas in Gaza.

Mr. Syed says international and domestic security concerns led Tehran “to send a robust message that ‘look, we’ll not be trifled with.’”

The cost of that message was Pakistan’s trust and sense of security.

Although Iran and Pakistan “have sought to quickly reengage and de-escalate tensions, the relationship has been damaged,” says Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s former permanent representative to the United Nations. To repair it, she says Iran will need to “check smuggling and cross-border terrorism,” and ensure “Baloch militants don’t have a sanctuary in Iran’s border areas.”

Iran and Pakistan: Can trust be rebuilt?

After a week of hostility, including missile exchanges, there are welcome signs of a rapprochement between Iran and Pakistan. The two Muslim countries issued a joint statement yesterday announcing that the Iranian foreign minister, Hossein Amir Abdollahian, would visit Islamabad next week, and that the ambassadors of both countries would “return to their respective posts” by Jan. 26.

The statement marks the end of a diplomatic crisis that began last Tuesday, when Iran launched an unexpected missile and drone attack that killed at least two children in Pakistan’s sparsely populated Balochistan province. Iranian officials claimed that the operation was aimed at neutralizing members of the obscure militant outfit Jaish al-Adl, which Iran holds responsible for past attacks on its side of the border.

Commentators in Pakistan, however, remain skeptical about this explanation. “I think that it was a blunder from sections of the Iranian deep state who tend to be trigger-happy,” says Mushahid Hussain Syed, a Pakistani senator and foreign policy expert, noting that Iran is facing domestic pressure over recent security breaches inside its territory, as well as pressure from the United States and Israel over its support of Hamas in Gaza and the Houthis in Yemen.

These circumstances, according to Mr. Syed, led Tehran “to send a robust message that ‘look, we’ll not be trifled with.’”

The cost of that message was Pakistan’s trust.

“Although the two neighbors have sought to quickly reengage and de-escalate tensions, the relationship has been damaged,” says Maleeha Lodhi, Pakistan’s former permanent representative to the United Nations.

To repair it, she argues that Iran will need to “check smuggling and cross-border terrorism,” with a particular focus on ensuring that “Baloch militants don’t have a sanctuary in Iran’s border areas.”

Iran’s muddy motives

“People are having trouble figuring out what exactly was the motive for Iran to do this,” says political commentator Mosharraf Zaidi, who served as a policy adviser at Pakistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2011 to 2013. “The only plausible explanation that I’ve been able to manufacture for myself is the ability of Iran to signal to other actors, specifically the U.S. and Western actors, possibly Israel, that Iran is not afraid of escalating ... so beware.”

Where many believe Iran miscalculated was in its failure to anticipate the speed of the response. Within 48 hours of the initial attack, Pakistan fired at a village in the Sistan and Baluchestan province of Iran, with Iranian media reporting the deaths of nine people, including four children.

“Pakistan’s pushback has shown Iran the limits of its power and its strategy of calculated chaos in the greater Middle East,” says former Pakistani Ambassador Husain Haqqani, who is currently a scholar at Washington’s Hudson Institute and the Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

The Pakistan-Iran border, according to officials from both sides, is home to a number of separatist groups made up of ethnic Baloch fighters who operate in both countries as part of a long-running insurgency. The fact that these groups pose a common threat to Iran and Pakistan has left many perplexed by Tehran’s choice to take unilateral action.

“There is a security agreement in place between the two states, so why was that not operationalized?” asks Shireen Mazari, a foreign policy analyst and former minister for human rights.

For many in Pakistan, the unprovoked nature of the attack gave Islamabad no choice but to establish deterrence. It is “inexplicable why Iran behaved in such a reckless manner destroying goodwill in Pakistan, which had strengthened because of Iran’s position on Gaza,” says Dr. Mazari. “Pakistan gave a sensible response showing clearly that it can respond and prevail militarily.”

Restoring trust and security

The effectiveness of the military response notwithstanding, these tit-for-tat operations have left Pakistan on bad footing with three of its four neighbors. Only relations with China – which shares a short, 370-mile border with Pakistan – are stable. Pakistan’s relationship with India remains perennially troubled, principally because of the unresolved territorial dispute over Kashmir. More recently, Islamabad has also witnessed a souring of relations with Kabul, which it blames for protecting the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a group that regularly carries out suicide attacks along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

“The expectation in Pakistan was that with the return of the Taliban, the Pakistani relationship with Kabul would improve,” says national security expert Syed Rifaat Hussain. “But unfortunately, the spate of TTP-led attacks against security forces in Pakistan has defied that expectation.”

Now with the opening of a hostile theater with Iran, there is a sense in some quarters that Pakistan needs a strategic reset.

Mr. Syed argues that the only way for Pakistan to establish trust with its neighbors is through economic cooperation. “If our neighbors will have a strategic stake in our economic development ... I think then the issues of proxy wars and nonstate actors will be subordinated to the larger geoeconomic interest,” he says.

Others believe that Pakistan’s neighbors must shoulder the bulk of the blame. Mr. Zaidi, the political commentator, notes that Iran, India, and Afghanistan each deal with more border problems than Pakistan.

“I absolutely reject the idea that Pakistan’s disputes and issues with these three countries are entirely a product of Pakistani mistakes,” he says. “Those are three sovereign countries that make choices. Iran made a choice to attack Pakistan, Afghanistan every day makes a choice to support the TTP, and India has occupied Kashmir for over 70 years and continues to do so.”

Oscars go global with record international nominees

Hollywood used to act as a kind of chamber of commerce, handing out its golden guy to locally made movies. But great art doesn’t just come from one ZIP code, or one language. This year’s nominees for best picture are the most international in history.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Ever since Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” won best picture in 2020, non-American movies have become competitive across major categories at the Oscars.

This year’s nominees, announced this morning, include France’s “Anatomy of a Fall” and “The Zone of Interest,” which is in German, in the best picture category. It was the first time two international films have been nominated for best picture, according to the academy. Celine Song’s “Past Lives,” which is in Korean and English, also scored a best picture nomination, making it the most international lineup in academy history.

As a result of the increased acclaim for international films, the acting categories also feature more non-English-language performances. Sandra Hüller, who stars in both “Zone of Interest” and “Anatomy of a Fall,” was nominated for best actress for the latter.

And Lily Gladstone is considered a heavy favorite in that category to become the first Native American to win an Oscar for acting. She is one of several characters to speak Osage in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” about the murderous exploitation of that tribe in Oklahoma.

Oscars go global with record international nominees

In 2019, the director of the Korean movie “Parasite” jokingly called the Oscars a “very local” competition.

The Academy Awards, which had their inaugural ceremony in 1929, were originally intended as a vehicle to promote American studio pictures. There wasn’t even a category for international movies until 1957. The Oscars were to movies what the World Series is to baseball. Movies from overseas were mainly segregated in the best foreign language category. Only a handful were nominated for the grand prize: best picture. In recent years, there’s been a shift.

Ever since Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” won best picture in 2020, non-American movies have become competitive across major categories at the Oscars. This year’s nominees, announced this morning, include France’s “Anatomy of a Fall” and “The Zone of Interest,” which is in German, each with five nominations. Both are finalists in the best picture category. It was the first time two international films have been nominated for best picture, according to the academy. Celine Song’s “Past Lives,” which is in Korean and English, also scored a nomination, making it the most international lineup in Oscar history.

“There are more people in the academy who don’t define ‘movie’ as a Hollywood product,” says Michael Schulman, author of “Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat, and Tears.” “They have no investment in Hollywood as the center of the film industry.”

Janet Yang, the first Asian American president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, kicked off the televised announcements by describing the organization as “the home of global cinema.” She boasted that, this year, ballots were cast from 93 countries.

This year, every nominee for best documentary feature was international, which was another first.

“After the #OscarsSoWhite scandal, the academy made this big push to expand its membership and diversify who was voting for the Oscars,” says Mr. Schulman, a staff writer at The New Yorker. “And most of the attention went to the fact that they were bringing in younger people, more people of color, and more women. But one of the underappreciated effects was that the academy voting body got a lot more international. And I think you see the effect of that in a win like ‘Parasite,’ which was the first foreign language film to win best picture. I don’t think that would have happened in the old academy.”

That’s a big contrast with Hollywood’s golden age, which was tarnished by xenophobia. In the earliest years of motion pictures, foreign films dominated two-thirds of American screens. In 1922, U.S. studios formed a cartel in the form of the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America. They waged war on so-called immoral fare. “Such claims fell disproportionately on foreign films,” historian Kerry Segrave wrote in his 2004 book “Foreign Films in America.”

In 1949, there was a furor when Laurence Olivier’s “Hamlet” – a British movie – won best picture. Widely admired films by Federico Fellini and François Truffaut sometimes garnered nominations in categories such as best screenplay and best director. In 1973, Ingmar Bergman finally landed a best picture nomination for his Swedish drama “Cries and Whispers.”

Starting in the mid-1990s, a handful of international films vied for the best picture statuette. Credit the marketing acumen of now-disgraced Miramax heads Harvey and Bob Weinstein. They garnered nominations for “The Postman” (“Il Postino”) and “Life Is Beautiful.” In 2011, their French hit “The Artist” won best picture. (It wasn’t eligible for nomination for best foreign language film because, well, it’s a silent movie.)

Harvey Weinstein was, of course, convicted of rape and sexual assault, and his film company went out of business. Meanwhile, superhero offerings from Marvel and DC took over multiplexes, crowding out middlebrow fare once seen as irresistible to the academy. That’s opened the door for more non-English-language nominees. Often, it’s streaming services that have led the way. Netflix scored multiple nods for Alfonso Cuarón’s 2018 “Roma,” a best picture nominee. Last year, a new German adaptation of “All Quiet on the Western Front” was nominated for both best picture and best international film.

“The membership of the academy who are [in] Hollywood, who are in the industry, ... the movies that they generally are making are not the ones that they’re necessarily voting for,” says Pete Hammond, awards editor and columnist for Deadline Hollywood. “They’re voting for these things that come out from around the world, from these great filmmakers, and they’re finding these films that really, comparatively, don’t make much at the box office.”

Mainstream cinema chains are increasingly hosting non-English films. In part, it’s because Hollywood is producing fewer big screen movies, and so chains are looking for fare to fill multiplexes. But it also reflects audience demand. Moviegoers have been able to find the likes of “Anatomy of a Fall,” a marriage drama wrapped inside a murder mystery, at some Showcase Cinemas and AMCs. The Japanese release “Godzilla: Year One” – which garnered a nod for best visual effects – rampaged through multiplexes to rake in over $50 million in the United States.

And legendary Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki’s “The Boy and the Heron,” nominated for best animated feature, has netted $23 million in the U.S. That’s a record for an original anime feature. And subtitles no longer are considered a deterrent at the multiplex.

“More people want to go to the original foreign language version rather than the English dubbed version,” says Mr. Hammond. “A lot of the box office for that came from the subtitled version.”

As a result of the increased acclaim for international films, the acting categories also feature more non-English-language performances. Sandra Hüller, who stars in both “The Zone of Interest” and “Anatomy of a Fall,” was nominated for best actress for the latter. Lily Gladstone is considered a favorite in that category to become the first Native American to win an Oscar for acting. She is one of several characters speaking Osage in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” about the murderous exploitation of that tribe in Oklahoma.

The academy’s increasingly global outlook prompted it to rename the foreign language film category “international feature film.” Its diverse membership will continue to broaden the horizons of the big screen.

As Mr. Schulman puts it, “It’s going to continue to expand our perception of what a best picture is, what it looks like, what language it’s spoken in.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the number of Oscar nominations for “The Zone of Interest.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An open door on the world’s ore

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The world’s transition to green energy poses an inconvenient conundrum: how to avert one environmental crisis without creating another. To fuel that shift, mining for the ores needed in renewable technologies is set to expand rapidly over the next quarter century. Much of the current activity is happening in the absence of reliable data. A study published by Nature this month found 56% of mining areas visible by satellite have no known reported production information. That makes mitigating the impact of extraction more difficult.

Some in the industry are now aiming to correct that. The International Council on Mining and Minerals adopted what it hailed as a groundbreaking commitment to protect nature and communities near mines. Members promised to disclose the environmental risks of all projects by 2026 and ensure they cause no net loss of biodiversity by 2030.

Industrial greenwashing? Time will tell. But the council’s new rules neatly frame the start of a year in which transparency will become a critical tool in addressing climate change. The rules are an acknowledgment that, more than ever, permits to dig deep depend on cultivating higher ideals.

An open door on the world’s ore

The world’s transition to green energy poses an inconvenient conundrum: how to avert one environmental crisis without creating another. To fuel that shift, mining for the ores needed in renewable technologies is set to expand rapidly over the next quarter century – by as much as 50% for uranium and 500% for lithium, according to various estimates.

Much of the current activity is happening in the absence of reliable data. A study published by Nature this month found that more than half (56%) of mining areas visible by satellite have no known reported production information. That makes enabling the needed growth while also mitigating the impact of extraction more difficult.

Some in the industry are now aiming to correct that. The International Council on Mining and Minerals, a trade group representing more than 60 of the world’s largest mining companies and mining associations, adopted what it hailed as a groundbreaking commitment to protect nature and communities near mines. Members promised to disclose the environmental risks of all projects by 2026 and ensure they cause no net loss of biodiversity by 2030.

Industrial greenwashing? Time will tell. But the council’s new rules neatly frame the start of a year in which transparency will become a critical tool in addressing climate change. By December, all 195 signatories to the 2015 Paris Agreement must submit their first biennial transparency reports measuring their progress toward meeting the shared goals of the climate accord.

That coincides with efforts by a growing number of governments to strengthen the accountability of mining companies through data transparency and engagement with local communities – particularly Indigenous peoples – whose lands abut their worksites. In a workshop on transparency at the United Nations climate conference in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, last month, experts asked participants to describe what the term meant to them in practice. Responses included “common understanding,” “empowering communities,” and “building trust.”

To accelerate solutions to climate change, “transparency issues must be resolved,” notes Christopher Martius, an energy expert at the Center for International Forestry Research in Bogor, Indonesia. “Better data coherence can increase trust and accountability, as can improved participation and access to data,” he argued at the Dubai gathering.

On another front, the mining industry faces many anti-corruption investigations. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that 1 in 5 foreign bribes involve an extractive project. Now the industry faces demands for higher standards of environmental care. Its new rules are an acknowledgment that, more than ever, permits to dig deep depend on cultivating higher ideals.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

All that really exists

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Considering the nature of existence as spiritual, rather than physical, opens the door to healing.

All that really exists

Typically, people look to the physical senses to assess their condition, good or bad. After all, if matter is the basis of existence, it makes complete sense to address problems such as illness, lack, and injury physically.

Let’s consider, however, whether there is more to existence than meets the eye. Throughout Earth’s history, humanity has been greatly benefited by notable individuals who questioned what people commonly believed. One such deep thinker was Mary Baker Eddy, a follower of Christ Jesus and the discoverer of Christian Science. In her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” she states, “All that really exists is the divine Mind and its idea, and in this Mind the entire being is found harmonious and eternal” (p. 151).

This doesn’t suggest that we’re physical beings possessing some intermittent mental and spiritual aspects. It omits matter entirely from the equation underlying life.

This is a radical way of describing the basic foundation of the universe. Divine Mind isn’t something that came into being as a result of a big bang or other physical phenomenon. This Mind, God, is entirely spiritual and eternal. It’s the ageless, matterless Principle underlying all true existence.

Divine Mind doesn’t produce physicality; Mind produces ideas. That includes each of us, in our true nature, as Christian Science teaches. As the creation of Mind, or God’s spiritual offspring, we reflect God, proving Mind’s presence. Matter is the counterfeit of God’s creation. Christ Jesus, whose healing works demonstrated the supremacy of Spirit rather than matter, said, “The Father that dwelleth in me, he doeth the works” (John 14:10).

This timeless observation applies to us today, too. We have a God-given capability to prove that the divine Mind’s perfection, abilities, and pure goodness are what constitute existence, and that nothing can stop us from expressing God to the fullest.

Some years ago, when I was in college, I was doing a backflip at a party when I landed on a slippery spot on the floor. My feet went out from under me and my face hit the floor. It was clear that my nose was broken.

Rather than seeing myself as a material machine, I considered the situation from a spiritual perspective. Since the harmonious, eternal divine Mind is the source of existence, no physical surface can affect or alter our true being. It would have to disrupt the harmony of Mind before it could change the harmony Mind expresses in us. God, Spirit, being infinite and good, this is impossible. There is no material aspect to God, who is perpetually expressing His purity and peace in us. As God’s loved, spiritual ideas, we mirror Mind’s wholeness and goodness.

This fresh perspective was a result of Christ, Truth, working in my thoughts, and I felt a growing confidence as a result. The reality of perfect Mind – and of everyone as this Mind’s perfect, invulnerable idea – made significantly more sense to me.

This glimpse of how all things, as a result of the allness of Mind, are permanently whole, spiritual, and good healed me. By the next day there was no discoloration, no pain, no evidence of any accident.

It’s worth it to look beyond what the physical senses convey and explore the spiritual makeup of existence. “Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth: for I am God, and there is none else,” explains the Bible (Isaiah 45:22). That doesn’t leave us out, though. We exist perfectly as what Mind is doing, what Mind is expressing. It’s beautiful how gaining even a slight awareness of this heals and restores.

Viewfinder

A cool 70

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Before we let you go, we want to make sure you know about the online event we’re holding on Thursday, Jan. 25, at 7 p.m. Eastern time.

It will be a deeper dive on how young people whose lives have been shaped by climate change are now leading the charge to find solutions. These are remarkable stories of innovation and determination that can change the way you see the issue.

You can find the Facebook Live page here. Be sure to bookmark it and come back Thursday.