- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Which country trusts institutions the most? You’d be surprised.

- Today’s news briefs

- Russia’s presidential election begins today. Here are 3 reasons Putin will win.

- In France, ‘defending the culture,’ but not all of its icons

- Brazil’s Lula wants to end Amazon deforestation. Why is it so hard?

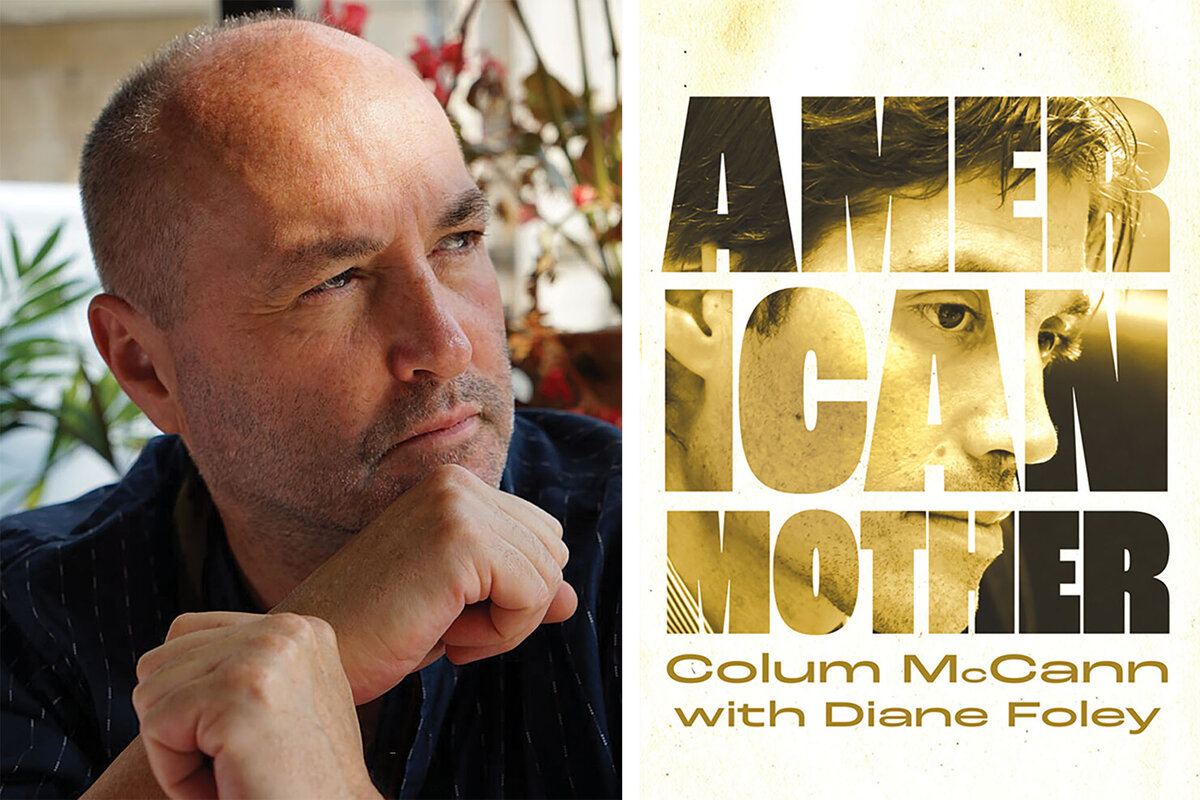

- Mother of James Foley embodies grace in new book ‘American Mother’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Would you run against Vladimir Putin?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

The Russian presidential election finishes this weekend. No, it will not be a nail-biter. Earlier this week, Fred Weir looked at how Russia has slowly choked many of its last vestiges of democracy. Today, he looks at who’s running. Who runs against Vladimir Putin?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Graphic

Which country trusts institutions the most? You’d be surprised.

Authoritarian China tops a recent survey, while the United States is nearer the bottom. The finding points to new dynamics in global trust. Here, we explore that trend and others in six graphics.

“All power is a trust,” British politician Benjamin Disraeli once said. Trust is the essential currency of free societies – the covenant to act honestly, respectfully, efficiently.

But at a time of global challenge and change, trust has been hard to build. As part of our ongoing Rebuilding Trust project, we look at several key indicators of global trust. In some cases, they show economically advanced nations struggling with trust more than the developing world, and a lack of trust in experts and officials. A fractured media landscape has given more fuel to populist frustrations.

Yet trust is on the rebound since the Great Recession and the pandemic, and trends point to a simple truth: When people feel things are getting better, trust improves.

Which country trusts institutions the most? You’d be surprised.

Trust has always made the world go round. Perceptions of honesty and reliability underpin how countries interact, how we choose our leaders, and where we get information about the world. And all these factors deeply influence how we feel about the future.

In an increasingly complex and interconnected world, trust is perhaps even more important – but harder to build. An outbreak in China can create a global pandemic. Disruptions in supply chains are felt from Atlanta to Amsterdam. And massive migration blurs national borders. The trends would seem to call on the world to draw together to find answers collectively. But disruptions often lead to the opposite – fear, mistrust, and isolation.

During this time of rapid technological and societal change worldwide, we have become less trusting. Political movements seek to wrest control from elites, and media have fractured from a handful of closely controlled voices to a kaleidoscope of opinions. That can drive positive change, but it has also given momentum to populist resentment and made truth a battleground.

As part of our Rebuilding Trust project, we take a look at several key snapshots of global trust.

Institutional trust is reviving

From corporations to governments, institutions shape our lives, but are often hard to get a grasp on. Surveys show that, in general, we trust institutions that we see as efficient and ethical – in short, that are running the way they should.

Integrated Values Surveys, Edelman Trust Barometer

Trust in institutions hit its lowest ebb in 2017, but has rebounded somewhat since. In its 2024 trust survey, the Edelman Trust Barometer found that business, government, nongovernmental organizations, and the media were all trusted by at least half of respondents globally. Business remains the most trusted institution, seen as competent and ethical. Trust grew in nearly every sector of business, including food, education, energy, manufacturing, health care, and technology. The lone exception was social media, which is still distrusted by 49% of people.

Governments gain trust

Some of this rebound appears connected to the world moving beyond the Great Recession and the pandemic. The 2010s saw trust in government reach its lowest point as wages stagnated, financial crises rocked the European Union, and corruption roiled developing nations. State-run economies such as in China and the United Arab Emirates were able to preserve government trust during this period. Trust in government remained less than 50% until 2021 but has grown in the wake of the pandemic. With a score of 79%, China ranks first in institutional trust among 28 nations in Edelman’s survey.

The trust divide

Yet new dynamics have emerged in the form of new divisions. The 15-point gap in trust between high- and low-income groups in 2023 was tied for an all-time high. Likewise, a similar divide between well-informed and uninformed groups has formed. In many places, the majority of a wealthier, better-read group feels trusting, while the majority of others do not. On a national level, developing countries are more trusting than developed countries. Among the least-trusting countries surveyed in 2024 were the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, Germany, and the United States.

Trust moves local

A key trend is the growing tendency to trust people we know as much as (or more than) experts and officials we don’t. In 2024, Edelman found that 74% of respondents trusted “someone like me” to tell the truth about new technologies and innovations, the same number who trusted scientists. Less than half of respondents expected journalists and government officials to tell the truth. In business, people’s employers were seen as more trustworthy than other business leaders. Support for multinational companies based in China, the U.S., and Germany fell significantly in the past year.

Integrated Values Surveys, Edelman Trust Barometer

Today’s news briefs

• Gaza cease-fire proposal: The United States has circulated the final draft of a United Nations Security Council resolution that would support international efforts to establish “an immediate and sustained cease-fire” in the Israel-Hamas war.

• Brazilian election plot reported: According to judicial documents, top Brazilian military leaders told police that former President Jair Bolsonaro presented to them a plan to reverse the results of the 2022 election he lost.

• Special prosecutor leaves Georgia case: A special prosecutor who had a romantic relationship with Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has withdrawn from the Georgia election interference case against former President Donald Trump.

• Aid nears Gaza: A ship carrying 200 tons of aid is approaching the coast of Gaza to inaugurate a sea route from Cyprus and could arrive March 15.

• Chuck Schumer calls out Netanyahu: U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer calls for new elections in Israel, harshly criticizing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as an obstacle to peace.

Russia’s presidential election begins today. Here are 3 reasons Putin will win.

Russia’s opposition once featured an array of political parties, and even some limited space for genuine critics of Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin. What remains of that today?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Barring the unforeseen, Vladimir Putin is certain to win Russia’s presidential election, which ends March 17. Given the lack of real competition, it’s become common to dismiss the whole process as a meaningless charade.

Yet the Kremlin takes it very seriously. So does the opposition. There are multiple candidates running against Mr. Putin, and the campaign is unfolding according to the terms of Russia’s constitution.

The three parties with candidates running against Mr. Putin in the presidential election all hold seats in Russia’s lower house of parliament and claim to have significant differences with the Kremlin. Those differences don’t include the war in Ukraine; the only potential anti-war candidate was excluded from the ballot in February.

Outside this “systemic” opposition, there are few others that have any capacity to pose a political challenge to the Kremlin. Many leading figures have been arrested on grounds of anti-war agitation. Others have joined an exodus into self-imposed exile in the West.

And while thousands risked arrest to pay final respects at the funeral of the best-known anti-Kremlin opposition figure, Alexei Navalny, experts point out that those were acts of individual conscience, not evidence of an organized movement.

Russia’s presidential election begins today. Here are 3 reasons Putin will win.

Barring the unforeseen, Vladimir Putin is certain to win Russia’s presidential election, which ends March 17. Given the lack of real competition, it’s become common to dismiss the whole process as a meaningless charade.

Yet the Kremlin takes it very seriously. So does the opposition, part of which urges people to boycott the polls and another part advises that people turn out to vote against the incumbent. There are multiple candidates running against Mr. Putin, and the campaign is unfolding according to the terms of Russia’s constitution.

The situation draws into question just what role Russia’s various opposition groups, permitted or otherwise, play in society – and how much influence they really have. And it explains, at least in part, why Mr. Putin is all but guaranteed to continue his rule.

Most of Putin’s opposition isn’t actually opposed to him.

Besides the ruling pro-Kremlin United Russia party, there are several parties who style themselves as opposition. This “systemic” opposition takes part in elections and sometimes wins seats in legislatures at various levels.

The three parties with candidates running against Mr. Putin in the presidential election all hold seats in the State Duma (Russia’s lower house of parliament) and claim to have significant differences with the Kremlin. Those differences don’t include the war in Ukraine; the only potential anti-war candidate, Boris Nadezhdin, was excluded from the ballot on a technicality in February.

The right-wing populist Liberal Democratic Party is actually further right than Mr. Putin on foreign policy issues, and generally votes the Kremlin line in the Duma.

The liberal-nationalist New People party surprised everyone in the last parliamentary election by hurdling the 5% barrier to gain representation in the Duma. But it has been accused of being a faux opposition project, one that talks about radical reforms but has so far made no waves.

The only one with a genuine opposition pedigree is the Communist Party, a traditional fixture of Russian politics with its own popular base and a program that sharply criticizes the Kremlin from the left. In the last presidential election in 2018, its candidate got 9 million votes.

But on the war and confrontation with the West, the Communists are also on the hawkish side. Yaroslav Listov, a Communist Party official, says the party is very satisfied that the Kremlin has “been shifting in the direction of our agenda. ... We advocated since 2014 for steps against the anti-Russia regime in Ukraine, which our authorities only adopted in 2022.”

And those that are actually opposed to him don’t have enough support.

For at least a decade, the Kremlin has been actively shutting down politically active civil society organizations that receive foreign funding. That includes most groups focused on human rights, the environment, democracy promotion, and LGBTQ+ issues.

More recently, the always fragmented and fractious political opposition has been hollowed out by arrests of many leading figures on grounds of anti-war agitation. Others have joined an exodus into self-imposed exile in the West.

For those who remain, any form of political activity or speech is increasingly dangerous. Dmitry Anisimov, press spokesperson for OVD-Info, a group that helps victims of political repression, says it’s becoming much harder to defend people accused of anti-war activity because the courts no longer listen to legal arguments that might exonerate them.

“Out of 110 cases we were involved in in 2023, we only managed to save 20 people from prison terms,” Mr. Anisimov says. “We consider that a great achievement.”

The death of the country’s best-known anti-Kremlin “nonsystemic” opposition figure, Alexei Navalny, struck another blow by removing the person who seemed able to unify Kremlin opponents of diverse views. Though thousands risked arrest to pay final respects at his funeral, experts point out that those were acts of individual conscience, not evidence of an organized mass movement.

Polls show Putin is still popular, even if they are questionable.

Public opinion polling is a difficult science in the best circumstances. But in wartime Russia, after more than two decades of hardening authoritarian rule, surveys should be read with skepticism.

The independent Levada Center is still conducting political polls, and it currently finds Mr. Putin’s public approval rating near an all-time high of 85%. Much of that may be down to a belief that there is no viable alternative – a situation the Kremlin has assiduously worked to create – or a fear that anything that replaces him might be worse.

But experts note that two years of war has created a “rally round the flag” effect that benefits Mr. Putin, even as it has further alienated the minority of anti-Kremlin activists and war opponents, and subjected them to greater repression.

Mr. Putin also enjoys all the advantages of an incumbent in a heavily state-dependent society. And he has successfully steered his country through a barrage of Western sanctions that threatened to wreck Russia’s economy, and presently even appears to be taking the upper hand in the Ukraine war.

Podcast

In France, ‘defending the culture,’ but not all of its icons

The caricature of the libertine French male, practicing a form of predation masked as seduction, is one with deep roots and some social support. Our Paris-based writer looked at where trust in those pushing back has begun to stir. She joins our podcast to talk about her reporting.

It’s not about l’amour. It’s about “no more.”

French culture sometimes blurs the line between flirtation and harassment. Does that open a path, for some, to sexual abuse and rape?

Consider the auteur. Some Gallic cinema icons have pushed boundaries in ways that seem very familiar to those who watched the #MeToo movement simmer from the mid-2000s until its 2017 boil-over. This week’s U.S.-based lawsuit aimed at nonagenarian director Roman Polanski, based on new sexual assault allegations over actions from the 1970s, is the latest wrinkle in a long-running story.

“In France you have actors who of course have this celebrity status, but that has extended in the last century or so to directors as well,” says Colette Davidson. These men were lifted to a kind of demigod status, Colette says on the “Why We Wrote This” podcast, “able to … get away with things in the name of culture, of creativity in the way that maybe others wouldn’t be able to.”

Increasingly, the defense of these transgressors has people up in arms, Colette says. The story she reported became more than a justice story. As women who’ve been subjected to abuse speak out, some now gain a society’s trust.

“I think France is experiencing a second wave of the #MeToo movement,” Colette says, “and [French people] are starting to listen.” – Clayton Collins and Mackenzie Farkus

Find story links and a full transcript here.

#MeToo, French Edition

Brazil’s Lula wants to end Amazon deforestation. Why is it so hard?

Brazilian President Lula has put a big focus on protecting the environment, backing expensive operations to combat illegal mining and other crimes in the Amazon. But can political will come too late?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ana Ionova Contributor

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has put millions of dollars into protecting the Amazon since taking office for his third term. But the high-profile operations kicking illegal miners off protected lands and bringing aid to remote Indigenous communities have not had the desired outcome. The total area of the Amazon occupied by illegal mining was 7% larger last year than in 2022. Environmental bodies were so gutted by former President Jair Bolsonaro that they weren’t equipped to handle many of Lula’s operations, handing control to the armed forces.

The Amazon, often referred to as the “lungs of the world,” stores vast quantities of carbon, and its preservation is key to fighting global warming. Although protecting the Amazon has been a global talking point for decades, illegal activities from logging to ranching, and gold mining to drug trafficking, have put it at risk. The destruction increased under Mr. Bolsonaro, who encouraged illegal exploitation of the rainforest.

Even as Lula has vowed to eliminate deforestation by 2030, observers say money and political will, at this point, may not be enough on their own.

“We don’t have a plan for the forest,” says Márcio Astrini, executive secretary of the Climate Observatory, a coalition of nongovernmental environmental groups. “And we need one urgently.”

Brazil’s Lula wants to end Amazon deforestation. Why is it so hard?

The small plane hovers low above the scrappy forest canopy, with rivers below colored a murky yellow due to mining waste. On the ground, deep in the Amazon rainforest, an armed Brazilian government agent watches as a dredge used to illegally mine gold from the Yanomami Indigenous Territory erupts into flames – destroyed on orders from the Federal Police.

The scene unfolded during a government raid earlier this year, and was part of a government crackdown on the illegal mining that has ushered in deforestation, hunger, and conflict in Brazil’s Amazon. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva pledged millions of dollars for high-profile environmental protection operations, in which authorities destroyed 340 mining camps in the first four months of 2023 alone, and expelled invaders from 80% of the protected forest they occupied.

But many wildcat miners have since returned to the Yanomami territory, from which they have been legally barred since it became a federally protected land in 1992. In fact, the total area occupied by illegal mining was 7% larger last year than in 2022, reaching nearly 13,500 acres. The miners “were not intimidated” by the government’s high-profile and well-funded mission, says Edinho Batista, coordinator of the Indigenous Council of Roraima, where the Yanomami reserve is located.

The Amazon, often referred to as the “lungs of the world,” stores vast quantities of carbon, and its preservation is key to fighting global warming. In Brazil, which holds about 60% of this vast rainforest, it is home to endangered Indigenous cultures and countless plant and animal species.

Although protecting the Amazon has been a global talking point for decades, illegal activities from logging to ranching, and gold mining to drug trafficking, have long put it at risk. The destruction increased under former President Jair Bolsonaro, who welcomed and even encouraged illegal exploitation of the rainforest. Widespread human-made wildfires racing across the Amazon today underscore its fragile state as rains dwindle and the forest becomes drier.

President da Silva, popularly known as Lula, has doubled down on protecting the Amazon ecosystem and its Indigenous inhabitants, vowing to eliminate deforestation by 2030 and end illegal logging, mining, and ranching on Indigenous lands. Yet observers say money and political will, at this point, may not be enough on their own.

“We don’t have a plan for the forest,” says Márcio Astrini, executive secretary of the Climate Observatory, a coalition of nongovernmental environmental groups. “And we need one urgently.”

“Sabotaged” plans?

Violence, hunger, and disease have exploded in the Yanomami’s territory since 2019, spiraling into a crisis that has captured headlines at home and abroad. Indigenous people say armed miners threaten them, scare off wild game, and pollute rivers with mercury – poisoning the fish and their drinking water. Outsiders have also brought along drugs, alcohol, sexual violence, and diseases that pose deadly risks to Indigenous people, according to Mr. Batista.

Brazil’s health ministry recorded 363 deaths in the Yanomami reserve in 2023 – a death rate more than three times the national average – with many children under 5 years old sickened by malnutrition or malaria brought in by consequences illegal mining, such as standing water.

The situation is dire. And yet “when Lula took office, he set a different tone,” says Jorge Dantas, a spokesperson for Greenpeace Brazil. He’s made good on many of his environmental promises, with deforestation dropping by half during his first year in office, and the government expelling thousands of intruders from Indigenous reserves.

“The federal government showed it was willing to combat environmental crime and preserve protected areas,” Mr. Dantas says. But their “efforts have not proven to be enough.”

Indigenous advocates say that in the Yanomami territory, Lula’s environmental strides began to unwind when cash-strapped environmental agencies pulled back from the area following early operations, handing the reins over to Brazil’s armed forces to carry the work forward.

Federal environmental agencies are still reeling from deep cuts suffered under Mr. Bolsonaro, Mr. Dantas says. “You don’t have equipment; you don’t have aircrafts; you don’t have enough agents. ... You can’t stay there forever.”

The armed forces were tasked last year with blocking illegal miners from entering the Indigenous territory, as well as distributing aid to remote villages suffering the impacts of mining. But the army, sympathetic to Mr. Bolsonaro, failed to deliver thousands of food baskets to the Yanomami people, while allowing planes carrying supplies for illegal mines to fly over the region and land on illicit landing strips carved into the forest.

“The armed forces sabotaged the plan,” says Mr. Astrini. “So retaking control of the region became even more complex.”

The armed forces have denied allowing miners to return to the Yanomami reserve, maintaining that they are doing their best to contain the problem. But Lula has struggled to gain the loyalty of the military, which was implicated in the storming of Brazil’s capital in January 2023.

“This shows the government’s weakness” in the Amazon, says Mr. Batista. “And miners exploited it.”

New strategies

In addition, as organized criminals increasingly bet on illegal gold mining, they tap into the same air, land, and river routes to transport illegal gold, arms, and drugs through the rainforest, says Mr. Astrini. “The profile of environmental crime is changing,” he says.

“These forces ... require a much more powerful counterattack from the government,” Mr. Astrini says. “Today, crime in the Amazon is a highly organized, billion-dollar business. And it’s a crime that has a huge political influence.”

State and federal lawmakers have stifled efforts to bolster environmental laws and, in some cases, have even dismantled protections. Last year, Brazil’s Congress passed a law requiring Indigenous people to prove they occupied the ancestral lands they claim before Brazil’s Constitution took effect in 1988, something the Supreme Court has ruled unconstitutional.

Late last month, Lula pledged an additional $241 million for combating illegal mining specifically in the Yanomami reserve. His administration also created a new government base in the state of Roraima to serve as a departure point for humanitarian aid and multiagency operations that will aim to force out the miners once again. It will operate until the end of 2026.

Although large-scale environmental protection investments and the deployment of the armed forces might be a “quick, satisfying” solution to the problem, Mr. Dantas says, to keep invaders out for good, Brazil must look deeper, toward root problems. That could include investing in income-generating jobs that don’t harm the forest, such as in ecotourism or sustainable oil extraction, to give illegal miners alternative ways to earn a living.

“Everyone cheers when they see the tractor being set on fire or the dredger being blown up,” Mr. Dantas says, but that’s not creating lasting change.

While small-scale projects focused on the sustainable production of fruits or timber from the rainforest could point the way forward, they lack the financing to scale up. And, even as Lula calls attention to his green agenda, he is pushing forward megaprojects, like an oil-drilling operation near the mouth of the Amazon River.

The key, Mr. Astrini says, is investing in models that keep the forest standing. “The world is looking at the Amazon,” he says. “We just need to choose a different path forward.”

Mother of James Foley embodies grace in new book ‘American Mother’

True stories of courage give us hope. In this book, a mother’s grief and loss becomes a catalyst for helping U.S. hostages and their families.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

“American Mother” opens with an extraordinary meeting. Diane Foley, mother of James Foley, the American journalist who was beheaded by Islamic State militants in 2012, met with one of the men responsible for his killing.

“I wanted to try to build a bridge,” Mrs. Foley says in an interview. “I prayed to try to see him as a human being, a young man about the same age as one of our sons.”

The encounter took place in 2021, when the man was in U.S. custody; he was eventually convicted for his involvement in the hostage-taking and murder of several people, including Mr. Foley.

The meeting underscores Mrs. Foley’s depth of humanity, which is threaded through “American Mother,” a nonfiction book written by Irish novelist Colum McCann with Mrs. Foley. It follows her son’s life from his childhood through his reporting trips to conflict zones in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and finally Syria.

“She’s learned to turn this grief into something really powerful,” Mr. McCann says. “Nobody else has changed the landscape of American politics in relation to hostage-taking and wrongfully detained people as much as Diane Foley has.”

Mother of James Foley embodies grace in new book ‘American Mother’

Diane Foley remembers the moment she got the call: Would you like to sit down with one of the men involved in your son’s death?

“I knew I wanted to meet him,” she says in a video call. “I had no doubt. I knew Jim would not have wanted me to be afraid, and that Jim would have wanted me to hear his side of the story.”

Her son, James Foley, was an American journalist taken hostage in 2012 while reporting in northwestern Syria. After 22 months in captivity, he was beheaded by the Islamic State group (ISIS).

“American Mother” opens with the extraordinary meeting between Mrs. Foley and Alexanda Kotey in 2021. The nonfiction book, written by Irish novelist Colum McCann with Mrs. Foley, chronicles her son’s life and reporting. He was embedded with troops during the United States’ post-9/11 conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and was detained in Libya for 44 days during the regime of Muammar Qaddafi.

The book captures the family’s trepidation as Mr. Foley returned to the front lines, and the haunting fear they endured after learning he had been captured again. But the book’s most poignant moments, paradoxically, center on silence – the months that unfolded in which no news surfaced from Syria, and barely any support came from the State Department or the White House, according to those involved.

From that void emerged Mrs. Foley’s faith and her determination to bring her son home. Those qualities movingly paralleled Mr. Foley’s resolve in captivity, as conveyed later by fellow hostages who survived the experience, including one who memorized a nine-paragraph letter written by Mr. Foley to his family. Mrs. Foley continued to let that determination fuel her in the months and years after he was killed, working to drive changes in U.S. hostage policy and support the families of other Americans held overseas.

“What I want is people to feel what she felt, to understand why she does what she does, and to understand the pain of everything that she went through and how she’s learned to turn this grief into something really powerful,” Mr. McCann says. “Nobody else has changed the landscape of American politics in relation to hostage-taking and wrongfully detained people as much as Diane Foley has.”

Mrs. Foley allows readers into intimate moments, like her challenging conversations with then-President Barack Obama, and the phone call with an emotional reporter who told her to look at Twitter (where news of her son’s killing was circulating). But the meetings with Mr. Kotey, the captured ISIS militant who participated in Mr. Foley’s hostage-taking, best reveal Mrs. Foley’s depth of humanity.

“I wanted to try to build a bridge,” Mrs. Foley says. “I prayed to try to see him as a human being, a young man about the same age as one of our sons.”

The conversations were challenging. Mr. Kotey, who at the time had pleaded guilty in a U.S. court to multiple charges related to hostage-takings and beheadings in Syria, was opaque on many topics. The British-born ISIS fighter disclaimed any involvement in Mr. Foley’s murder. (He is serving a life sentence in a federal prison for his involvement in the abduction and death of four hostages, including Mr. Foley.) He expressed remorse not for his actions but for the Foley family’s resulting ordeal.

Mrs. Foley persisted, though, returning to meet with him once more in 2022, probing him for a semblance of reflection. It’s telling how patiently she engaged, searching for a reason to keep seeking this connection.

“This is about the complications of being a mother,” says Mr. McCann, who joined Mrs. Foley for her meetings with Mr. Kotey. “This is a woman who sits down with her supposed enemy, the killer of her son, and says, ‘Let’s talk. Let’s try to understand each other. Because nothing will ever become good if we don’t try to understand each other.’”

The book crosses a threshold for Mr. McCann, best known for his work in fiction, including his National Book Award-winning “Let the Great World Spin.” Mr. Foley was once photographed reading it, one of many signals the writer says drew him to the family’s narrative.

“It picked me,” he says of the story. “The more I got into it, the more I felt that fate coincided with Diane’s faith, and that we were sort of destined to do this work together.”

Mr. McCann got his start writing for newspapers as a teenager in Dublin. That background helped him tap into Mr. Foley’s sense of purpose.

“He went in with that old dictum that John Berger talked about: ‘Never again will a single story be told as if it were the only one,’” Mr. McCann says. “He knew that the story of the wars that were going on had to be told from different angles.”

For Mrs. Foley, working on the book with Mr. McCann felt fitting. “One of the reasons Colum was able to capture the story so well is because he was like Jim in a lot of ways,” she says. “He knows how to tell a good story, and he knows how to listen well and is curious, like Jim was.”

The experience of writing it, she adds, lessened some of the silence she endured from 2012 to 2014. “I didn’t really know the man he became,” she says of her son. “It’s through the stories of others who knew him, kids whom he taught or other people, other journalists, and then finally the hostages he was with. It’s through those people we’ve come to know Jim.”

“American Mother” hits bookshelves at a time when understanding the experience of those held captive is a matter not only of empathy but also of public policy. Mrs. Foley continues to champion the issue through the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, which advocates for American hostages abroad and benefits from the book’s proceeds.

“There was no one to help us,” Mrs. Foley says. “So I’m hoping that some of Jim’s legacy is some positive change. Since his murder in 2014, more than 100 innocent Americans have come home. And that gives me great joy. More and more aspiring journalists are learning how important safety is. A lot of those things keep Jim alive for me.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Hoops of joy in March Madness

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Nothing stirs a human fluttering this time of year quite like March Madness, the annual college basketball championship tournament. Over three weeks, 134 games – 67 for men’s teams, 67 for women’s teams – will generate nearly $10 billion in economic activity in the host cities.

The tournament draws fans to places they otherwise might never go. Many have no direct connection to the teams they root for. They hop from city to city, drawn by those things that inspire joy and empathy – athletic grace, gallantry, community.

One explanation for the appeal of college athletics lies in the purity of its pursuit. Amateurism, wrote philosopher Heather Reid at Morningside University in Iowa, is rooted in the Latin word for love, or doing something out of intention and not for external reward. College sports teach “us to transform our love for an activity into excellence,” she wrote.

Games start Tuesday. On April 8, just one team will be left standing. During that three-week interval, the average fan will spend 36 hours engaging with college basketball – the stumbles, the Cinderellas, and the shots that beat the buzzer. It isn’t hard to see why. Love of excellence is a slam-dunk.

Hoops of joy in March Madness

In just a single weekend last March, the city of Albany, New York, received a sudden revenue bump large enough to cover nearly half of its annual budget for public works. Other small cities saw similar bursts in receipts. The reason: college basketball.

Spring migrations are underway – red-winged blackbirds to the north, baseball fans to the south. Yet nothing stirs a human fluttering this time of year quite like March Madness, the annual college basketball championship tournament. Over three weeks, 134 games – 67 for men’s teams, 67 for women’s teams – will generate nearly $10 billion in economic activity in the host cities.

The tournament draws fans to places they otherwise might never go. Many have no direct connection to the teams they root for. They hop from city to city, drawn by those things that inspire joy and empathy – athletic grace, gallantry, community. Every game risks it all. One team goes on; the other goes home.

“I more often than not, find myself rooting for the underdog team,” wrote Jillian Brown, an innovation consultant at Peer Insight. “One big reason is that we can see ourselves in this team. We’ve all been confronted with uphill battles, where we’re not expected to succeed but with passion and grit, we do.”

One explanation for the appeal of college athletics lies in the purity of its pursuit. Amateurism, wrote philosopher Heather Reid at Morningside University in Iowa, is rooted in the Latin word for love, or doing something out of intention and not for external reward. College sports teach “us to transform our love for an activity into excellence,” she wrote. They engage “uncommon character virtues.” Team sports are a “shared commitment to excellence.”

Nearly half of the NCAA teams make it to the national tournament by winning their regional championships. The rest are chosen by the National Collegiate Athletic Association on Selection Sunday, which happens this weekend. Then come the brackets, as fans fill in charts predicting winners and losers from the first round to the final game.

In the 85-year history of the tournament, no one has ever filled out a perfect bracket. But the brackets amplify the unique affections nourished by sports. Former Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama no longer debate policy in public. Now they playfully prod each other over their tournament predictions.

Games start Tuesday. On April 8, just one team will be left standing. During that three-week interval, a new survey by OnePoll found, the average fan will spend 36 hours watching, talking, and thinking about college basketball. About the stumbles, the Cinderellas, and the shots that beat the buzzer. It isn’t hard to see why. Love of excellence is a slam-dunk.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Judgment-free, of you and me!

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karyn Mandan

Seeing ourselves and each other the way God made us opens the door to interactions filled with joy, rather than judgmentalism.

Judgment-free, of you and me!

Maybe this has happened to you too. Have you ever been anxious about how others might see you and judge you? I had an experience where I felt anxious about what a friend might think of me, having not seen me for quite a while. What I soon learned, through deep, soul-searching prayer, was that the anxiety was rooted in judging myself!

I hadn’t seen this friend in a while. In the meantime, I’d gone through a difficult experience, and I didn’t feel the same – or look quite the same – as the last time she’d seen me. I believed I wasn’t measuring up to what I thought she expected of me – and, frankly, to what I expected of myself. While I waited for my friend to arrive for our visit, my anxiety compounded. Would she judge me?

I have learned that whenever I feel afraid or doubtful, it is always better to look at the situation from a spiritual perspective. So, right there in my living room, I reached out to God in prayer for a more inspired view.

Through my study of the Bible, illumined in the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, I’ve learned that God is the all-knowing and all-loving divine Mind. This Mind has created each of us spiritually as the manifestation of the divine nature. God sees us as purely good.

Referring to “man” as including everyone, the book of Genesis in the Bible puts it this way: “God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; ... And God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good” (1:27, 31).

Built into our spiritual individuality, which is one with the Divine, are Godlike qualities such as unselfishness, kindness, patience, understanding. Because of our unity with the one infinite divine Mind, we each have God-given spiritual intuition and discernment to recognize and express spiritual qualities and to see and appreciate them in one another. None of us can truly be held captive or be impelled by limited personal human opinions, expectations, or judgments.

Through Christ, Truth, we all have an unlimited, God-empowered capacity to know and experience something of this reality – to see the unchanging good that God manifests in everyone. As I realized that my friend had this capacity, too, my outlook brightened.

Mrs. Eddy writes in “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” referring to the spiritual reality explained by Christian Science, “The sweet, sacred sense and permanence of man’s unity with his Maker, in Science, illumines our present existence with the ever-presence and power of God, good” (p. 196).

As I glimpsed the spiritual unity that we each have with our divine source, and the fact that we’re empowered to see each other as God sees us, as wholly good, I gained a new view – a judgment-free view – of my friend and myself. When my friend arrived, our eyes met with genuine affection, because that is all we could see in each other. We threw our arms around each other in pure joy.

During our visit I discovered even more how unlimited good – originating in the divine Mind – is expressed in each of us as divine Mind’s reflection. I felt completely free of anxiety and enjoyed all of our activities together.

God, the infinite divine Mind, pours good through each of us – and in every circumstance is present to inspire views of ourselves and others that are free of personal judgment and full of joy.

Viewfinder

Before there was Burning Man ...

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with us this week. We’ll start next week by looking at two thorny foreign policy questions. If the United States stepped back, could Europe defend itself? And why does President Joe Biden seem so reluctant to use his leverage with Israel? We hope you’ll check back in Monday.