- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In words and deeds, US seeks Israeli restraint after Iran’s attack

- Today’s news briefs

- Why Trump ‘hush money’ trial is really about more than that

- Large, long, expensive: What to know about India’s election

- Letter from Denver: Historic mint still coins a pretty penny

- Should you trust the Monitor? We asked one media watchdog to audit us.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A ‘trust test’ for the Monitor

Readers want to trust the news they consume – trust the ways in which stories are chosen, sourced, and put in context. In other words, they want the tools they need to draw their own informed conclusions. Yet we know that trust in the media has frayed badly – which is particularly concerning in a consequential year of elections; wars in the Middle East, Ukraine, and elsewhere; and profound societal divisions.

The Monitor aims every day to earn your trust. To help us do that, we asked outside experts to evaluate our work. You’ll find an article today from the group Trusting News, sharing what it’s observed. Take a read. Do you agree with its findings? Please share your thoughts with Editor Mark Sappenfield at editor@csmonitor.com.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In words and deeds, US seeks Israeli restraint after Iran’s attack

With a muscular and collaborative defensive effort to help deflect Iran’s missile barrage, the Biden administration is hoping its message of “ironclad support” for Israel can prevent the escalation of the Gaza war into a regional conflict.

As Iran launched its unprecedented aerial attack on Israel Saturday night, all present in the White House Situation Room were holding their breath. Would Israeli air defense systems – and the combined assets of the international coalition led by the United States that had been scrambled to defend Israel – be up to the task of thwarting more than 300 drones and missiles?

Israel came through almost unscathed, demonstrating Israel’s and its partners’ military superiority and coordination. The display of international solidarity included the United Kingdom and France, with assistance, remarkably, from some of Israel’s Arab neighbors, including Jordan and to some extent Saudi Arabia.

But President Joe Biden underscored to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that the same decisive, U.S.-led support would not be there if Israel decided to retaliate against Iran in a manner that risked a broader conflict.

That leaves Israel to weigh a historical inclination to show strength and retaliate forcefully against the importance of maintaining strong international support – which has been weakening over Israel’s punishing assault on Gaza following Hamas’ brutal Oct. 7 attack on Israel.

In words and deeds, US seeks Israeli restraint after Iran’s attack

For one excruciatingly tense moment in the White House Situation Room, all present from President Joe Biden to Cabinet members and senior aides seated around the large table were holding their breath.

As part of its unprecedented aerial attack on Israel Saturday night, Iran had simultaneously launched more than 100 ballistic missiles. Everyone present knew the weapon was capable with just one successful hit of causing tremendous loss and damage – and of turning the war in Gaza into a broader regional conflict of unforeseen consequences.

Would Israeli air defense systems – and the combined assets of the international coalition led by the United States that had been scrambled to defend Israel – be up to the task of thwarting more than 300 drones and missiles?

In the end, Israel came through Iran’s attack almost unscathed – a result that demonstrated both Israel’s and its partners’ military superiority and unrivaled coordination.

But above all, it was the thwarting of those ballistic missiles that underscored the critical nature of Israel’s support from international partners as it navigates heightened tensions in a hostile neighborhood.

Participating in that defensive umbrella were the U.S. and other partners, including the United Kingdom and France, with assistance, remarkably, from some of Israel’s Arab neighbors including Jordan and even to some extent Saudi Arabia.

And it is this display of international solidarity – and what President Biden calls “ironclad support” – that the U.S. and others hope Israel will weigh heavily as it contemplates how to respond to the attack from Iran and its proxies, including Hezbollah.

“Nobody wants to run up the escalation ladder,” a senior White House official told journalists in a briefing Sunday. Repelling Iran’s attack “was an extraordinary feat of military prowess and participation of coalition partners,” the official continued. “Going forward, we all need to take that into account and think that through.”

“Take it as a win”

Indeed, that is one part of the message Mr. Biden communicated to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the phone conversation they held as the attack appeared to be over. “Take it as a win,” the president said.

Iran had signaled for nearly a week that it was preparing to retaliate against Israel in some manner for the April 1 attack on Iran’s diplomatic mission in Damascus, Syria, that killed three Iranian generals – including Brig. Gen. Mohammad Reza Zahedi, a senior Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander charged with directing Iran’s proxies in the fight with Israel.

Iran’s failure to cause any significant damage to Israel constituted a loss for Tehran, some analysts say. Others say the Iranian regime accomplished what it intended by demonstrating that it could attack Israel from its territory, along with the participation of proxies in numerous other countries, including Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen (via the Iran-aligned Houthis).

But Mr. Biden also underscored to Mr. Netanyahu that the same decisive U.S.-led international support and participation would not be there if Israel decided to retaliate against Iran in a manner that risked plunging the region into a broader conflict no one wants.

That leaves Israel to weigh a historical inclination to show strength and retaliate forcefully in response to any aggression, against the importance of maintaining this “ironclad” international support. Before Iran’s attack, that support was weakening over Israel’s punishing assault on Hamas in Gaza and Palestinian civilians there.

Among the factors that diplomats and international analysts say Israel will have to consider are two key ones. First, can Israel afford not to respond in kind to Iran’s first-ever direct attack on Israel – an attack that, even if unsuccessful, demonstrated Iran’s ability and willingness to go head-to-head with its adversary?

“I think there’s no question the Israelis are going to be compelled to respond to what was the first direct attack by the Islamic Republic on the Israeli mainland,” says Andrew Tabler, a senior fellow in Arab politics at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy who served on the National Security Council of former President Donald Trump.

“But do they have to do something right away and big, like bombing Iran’s nuclear facilities? No,” he adds, “the Israelis have time on their hands.”

Second, does maintaining international support outweigh a tenet of Israeli defense policy since the country’s founding, which is to retaliate for every attack, sometimes with even greater force?

Israel weighing US request

There were some early signs that Israel was at least weighing Mr. Biden’s admonition as it considers its next steps.

Demands Sunday from some members of Israel’s war Cabinet to proceed to immediate retaliatory strikes against Iran were put off, according to Israeli press reports. The war Cabinet met again Monday and reportedly was reconvening Tuesday, suggesting any decision was not final.

Axios reported Monday that Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant told U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in their phone call Sunday that Israel would be compelled to respond – especially given that ballistic missiles were included in the munitions barrage.

But Mr. Gallant also said the moment presents an opportunity to create a strategic alliance to counter Iran, according to the report.

Israel could decide to take a path forward somewhere between launching a direct strike on Iran that would risk escalation and doing nothing, some analysts say.

“The Israelis don’t want to get into a spiraling tit-for-tat confrontation with Iran, especially given that they are already fighting one war in Gaza and giving it all they’ve got, so that may create some room for prudence,” says Benjamin Friedman, policy director at Defense Priorities, a Washington think tank promoting U.S. foreign policy focused on national security interests.

“They may have to say they’re going to respond, but then they might proceed with some of the same low-level actions they’ve carried out against Iran for years,” he says – such as targeting Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps officers and assassinating Iranian nuclear scientists.

Yet while Mr. Friedman says he was relieved to see President Biden temper his “ironclad support” with a warning that the U.S. would not support a direct strike on Iran, he also worries it may have been too little, too late.

“I would have preferred that the president make this conditional support clearer back in the bear-hug days” following Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack. Now an unwillingness to define the limits of U.S. support earlier, he adds, could leave Israel thinking that in the end it will have that “ironclad” support no matter how it responds to Iran.

Today’s news briefs

• Iran claims it warned of attack: Iran’s foreign minister said Sunday that Tehran gave neighboring countries and the United States 72 hours’ notice of its drone and missile attack on Israel. A White House official said the statement was “absolutely not true.”

• Top U.S. diplomat meets Chinese counterparts: The meeting to discuss Middle East developments, the South China Sea, and Taiwan issues is the latest effort by the two countries to stabilize rocky ties.

• Tesla plans layoffs: CEO Elon Musk detailed plans to lay off a tenth of its workforce as it tries to cut costs after reporting dismal first-quarter sales, media outlets reported Monday. The layoffs could affect about 14,000 workers.

• Poorest nations getting poorer: Half of the world’s 75 poorest countries are experiencing a widening income gap with the wealthiest economies for the first time this century, the World Bank said Monday.

Why Trump ‘hush money’ trial is really about more than that

The so-called hush money case has been billed as one of the less important lawsuits facing former President Donald Trump. But it’s the one that is underway – and it goes beyond payments over an alleged affair.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

It’s often described as “the hush money case.”

But former President Donald Trump would not be facing an unprecedented criminal trial – the first ever to involve a past and possibly future chief executive of the United States – if all he had done was pay porn star Stormy Daniels to keep quiet about their alleged affair. Paying hush money on its own isn’t generally illegal.

What Mr. Trump instead has been charged with is orchestrating a cover-up to hide payments via fake invoices, checks, and ledgers – all to ensure that Ms. Daniels’ story did not become public and affect votes.

“The allegations are, in substance, that Donald Trump falsified business records to conceal an agreement with others to unlawfully influence the 2016 presidential election,” reads the first sentence of Judge Juan Merchan’s description of the case for potential jurors.

Thus the unprecedented trial, which began Monday in a Manhattan courtroom, promises to be both more sweeping and factually drier than its “hush money” description might suggest. Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg has charged Mr. Trump with 34 felony counts of falsifying business records. The former president has pleaded not guilty and denied the allegations, as he has in other criminal cases against him.

Why Trump ‘hush money’ trial is really about more than that

It’s often described as “the hush money case.”

But former President Donald Trump would not be facing an unprecedented criminal trial – the first ever to involve a past and possibly future chief executive of the United States – if all he had done was pay porn star Stormy Daniels to keep quiet about their alleged affair. Paying hush money on its own isn’t generally illegal.

What Mr. Trump instead has been charged with is orchestrating a cover-up to hide those payments via fake invoices, checks, and ledgers – all to ensure that Ms. Daniels’ story did not become public and affect votes.

“The allegations are, in substance, that Donald Trump falsified business records to conceal an agreement with others to unlawfully influence the 2016 presidential election,” reads the first sentence of Judge Juan Merchan’s description of the case for potential jurors.

Thus the unprecedented trial, which began Monday in a Manhattan courtroom, promises to be both more sweeping and factually drier than its “hush money” description might suggest. Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg has charged Mr. Trump with 34 felony counts of falsifying business records. The former president has pleaded not guilty and denied the allegations, as he has in all the criminal cases against him.

“It’s a complex case and I think there hasn’t been enough attention on just how complex it’s going to be for the prosecution to prove,” says Paul Collins, professor of legal studies and political science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Delays in other trials

So far, the most notable thing about the New York election interference trial may be that it has begun. Mr. Trump and his lawyers tried everything they could to push back the start date, filing motion after motion to try to get Judge Merchan off the case and generally slow down pre-trial progress.

Similar delay tactics have been more successful in the three other criminal cases Mr. Trump faces: the federal case on retention of classified documents, the federal case on allegations of interference in the 2020 election, and the Georgia state case on election interference.

At one point, the Manhattan trial seemed set to be the final one in that series, chronologically. But delays in the schedules of the others have now made it the first – and possibly the only – criminal case the former president will undergo prior to the November election.

Initial proceedings Monday were quiet as the prosecution and defense teams discussed what evidence will be allowed and other points of law with Judge Merchan. They were sleepy enough that Mr. Trump’s head drooped and he appeared to briefly fall asleep, according to New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman.

The atmosphere became more charged when, after lunch, the first group of potential jurors entered the courtroom and the first criminal proceedings against a former U.S. president officially began.

Judge Merchan welcomed them, pointed out Mr. Trump, and described the nature of the upcoming trial, according to reports from the courtroom.

“The people are served by whatever verdict” the jury decides, the presiding judge said.

Over the next two weeks or so, the defense and prosecution will pick, choose, or strike potential jurors as they try to assemble a jury to their liking. Manhattan is a blue district where many potential jurors may not be politically amenable to Mr. Trump – but the former president only needs one committed juror to prevent a guilty verdict, which must be unanimous.

Events before Trump was president

Of all the criminal cases Mr. Trump faces, the Manhattan trial deals with the earliest events. Its allegations involve actions Mr. Trump took prior to his 2016 election, while the others cover actions he made while president, or an ex-president. In that sense, its proceedings may be something of a blast from the past – particularly when Mr. Trump’s former fixer Michael Cohen testifies for the prosecution, as he’s currently scheduled to do.

Mr. Cohen was at the center of the payment scheme that funneled $130,000 to Ms. Daniels, according to prosecutors. He has said he took out a home equity line of credit and paid Ms. Daniels in October, 2016, to keep her from discussing a sexual relationship she said she had with Mr. Trump in 2006.

Mr. Trump, who married his third wife, Melania Trump, in 2005, has denied having sex with Ms. Daniels.

Mr. Cohen also alleges that Mr. Trump agreed to pay him back $420,000 for his efforts, in $35,000 monthly installments. That sum included a bonus for him and the costs of arranging for some online polls to skew in Mr. Trump’s favor.

Mr. Trump made these payments via checks from the Trump Organization, noted as “legal services.” The number of checks, ledgers, and other business documents falsified in this effort is what accounts for the number of charges now pending against Mr. Trump.

Prosecutors thus will not have to prove that Mr. Trump had a physical encounter with Ms. Daniels to win their case. They will instead focus on proving that the former president broke the law in the methods he employed to cover up her account, and that he and his associates were motivated to do so by worries that the story would sway voters in November, 2016.

Among the other notable people who might appear as witnesses in the case, read out to prospective jurors by Judge Merchan, were Steve Bannon, Rudy Giuliani, Jared Kushner, and Melania Trump. Not all will end up being called, but their names alone give a sense of the atmosphere that could develop around the trial.

The prosecution will rely heavily on a paper trail of documentary evidence in the effort to prove their allegations of financial chicanery. Still, “it’s going to be almost a circus in terms of the potential witnesses in this case, this cast of characters,” says Professor Collins. “We’re talking porn stars, Playboy models, convicted liars.”

Large, long, expensive: What to know about India’s election

Indians head to the polls this week for one of the world’s largest, longest, and most expensive elections. Here’s what you need to know before it starts.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

Fahad Shah Correspondent

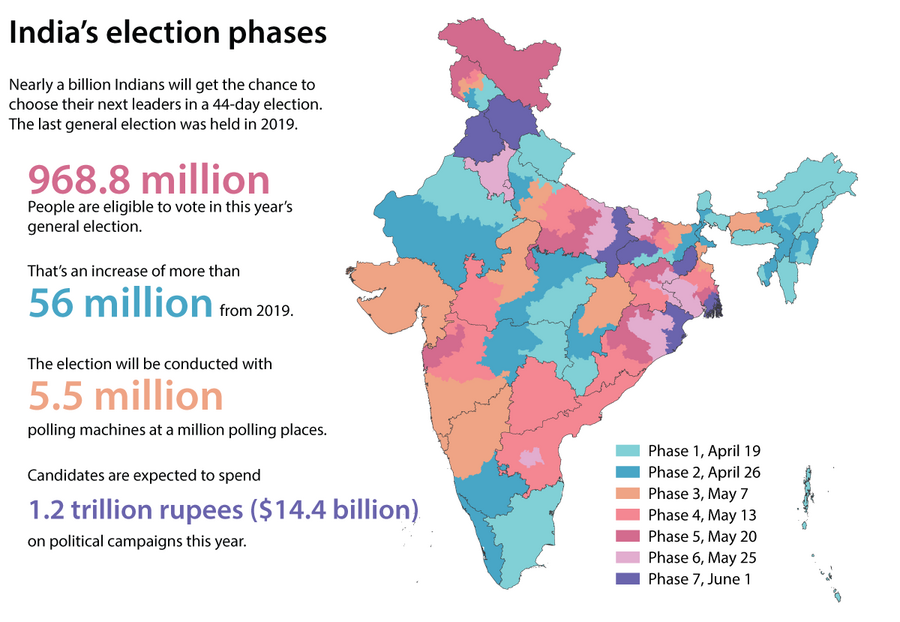

With 968.8 million registered voters – including 26.3 million first-time voters – India’s general election will be the largest in human history.

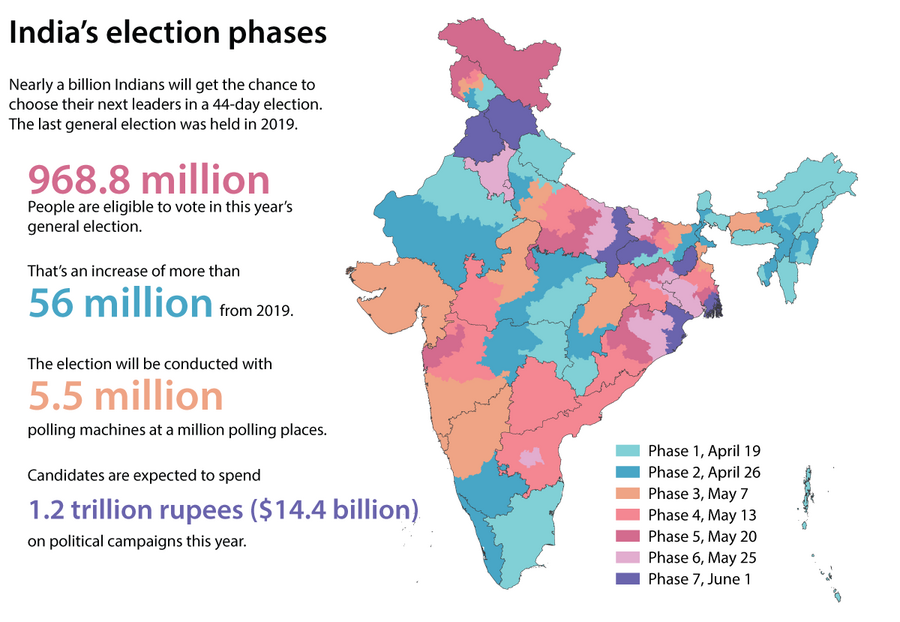

The seven-phase election starts April 19, and lasts 44 days. Facing off are the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, led by incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, a coalition of over two dozen opposition parties.

In 2019, the BJP won 303 of the 543 total parliament seats. In 2024, it aims to win 370. Political analysts say the BJP is well-positioned to do so, given its efforts to expand its voter base, as well as the massive amount of money it collected through India’s now-defunct electoral bonds system.

Still, opposition members are challenging the BJP over rising unemployment, policies targeting religious minorities, and India’s democratic backslide. In recent years, India has witnessed a crackdown on media freedom and civil liberties. Experts say upcoming polls will serve as a litmus test for its democratic values and commitment to upholding the principles enshrined in its constitution.

Large, long, expensive: What to know about India’s election

Nearly a billion people are eligible to vote in India’s general election, which begins Friday and lasts for more than a month. It will be the largest democratic election in human history.

Facing off are the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (I.N.D.I.A.), a coalition of over two dozen opposition parties. In 2019, the BJP won 303 of the 543 total parliament seats, while the main opposition party, the Indian National Congress, was reduced to only 52 seats.

In 2024, the BJP is aiming to win 370 seats – something political analysts say it’s well-positioned to do, given the party’s popularity and large war chest.

Still, I.N.D.I.A. members are challenging the BJP over rising unemployment, policies targeting religious minorities, and India’s democratic backslide. Indeed, in recent years, India has witnessed a crackdown on media freedom and civil liberties, and experts say upcoming polls will serve as a litmus test for its democratic values and the nation's commitment to upholding the principles enshrined in its constitution.

Election Commission of India, Reuters

With 968.8 million registered voters – including 26.3 million first-time voters – this election, if all goes smoothly, will be a major logistical feat.

The seven-phase election spans 44 days, commencing on April 19 with voting in 102 parliamentary constituencies. Results are expected on June 4.

More than 15 million officials will be called on to oversee the operation of over 5 million electronic voting machines in over a million different polling stations. Stringent security measures, including the deployment of the government forces, have been taken up to ensure a peaceful election.

Election Commission/State Bank of India

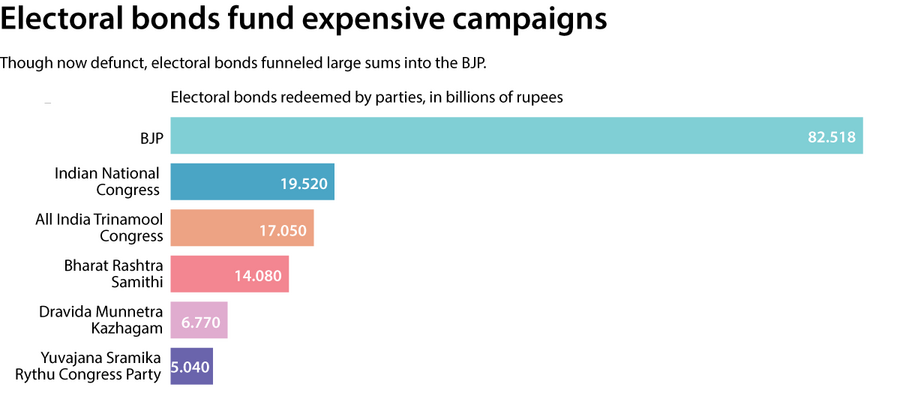

According to experts, these elections are also poised to become the most expensive globally, with money spent by political parties and candidates expected to exceed the $14.4 billion spent on the U.S. presidential and congressional races in 2020. Already $2 billion has been funneled through India’s electoral bonds system, a now-defunct program introduced by the BJP government in 2017, enabling anonymous donors – including corporations – to fund political parties.

The Indian Supreme Court decided to abolish electoral bonds in February over concerns of fostering corruption, and data revealed shortly after confirmed that the BJP was the primary beneficiary.

The Election Commission of India reports that the BJP received 82.5 billion rupees (nearly $1 billion) from a total of $2 billion worth of bonds sold between 2018 and 2024. In contrast, the main opposition Congress party received only 19.5 billion rupees ($2.38 million) during the same period.

Opposition leader Rahul Gandhi has criticized the BJP, asserting that it “made electoral bonds a medium for taking bribes and commission.” Despite the system’s abolition, concerns persist regarding the influx of unaccounted cash donations.

Pew Research Center

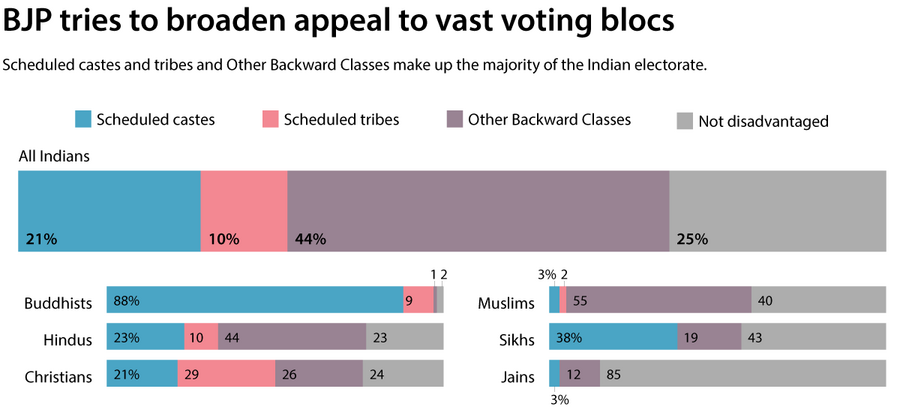

In India, caste and religious affiliations have historically influenced voting patterns.

The BJP's Hindu nationalist and pro-business platform, for example, has traditionally made it popular among upper-caste Hindus. But under Mr. Modi's leadership, the BJP has worked to broaden its electoral appeal, leveraging welfare programs to target lower-caste voters. Mr. Modi himself comes from an OBC (Other Backward Classes) background – an official umbrella term for castes the government defines as educationally or socially backward – which has helped his party make significant inroads into a key voting bloc.

India’s census data doesn’t show caste demographics, but according to estimates, more than 40% of the population identify as belonging to OBC.

The opposition is actively courting lower-caste voters as well, including advocating for a nationwide survey on the distribution and demographics of different caste groups. The caste census is a hot-button issue which critics deem discriminatory, but proponents argue would help address current-day caste disparities. At a recent public rally, Mr. Gandhi announced that if the Congress party is voted to power, it will immediately conduct a caste census throughout India.

Election Commission of India, Reuters

Letter from Denver: Historic mint still coins a pretty penny

The U.S. Mint at Denver cranks out $1 million a day in coins. In an era when “frictionless” payment implies distance from human touch, there’s still value in having cash “in hand.’’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Millions of Americans today live far removed from cash. Many have filed their taxes due this week as pixels on screens.

But here at the century-old Denver Mint, the physical legacy of money as well as its future for commerce and society are on display.

For some people, there’s comfort in something you can hold in your hands. Largely unchanged since production began around 600 B.C.E., the rounded form of coins is considered especially tamper-resistant.

Cash is also key for national emergencies, experts say, and vital for U.S. households without easy access to banking. In 2021, the “unbanked” share of the population stood at nearly 6 million households, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

But the coins aren’t without controversy. The unit costs of pennies and nickels continue to exceed their face value. Some Americans have asked legislators to retire them. Under Gov. Jared Polis, Colorado has recently allowed the payment of state taxes with cryptocurrency.

Adoption has been slow since the option began in September 2022. As of last week, the Colorado Department of Revenue estimates that state income taxes have been paid via cryptocurrency 28 times. The state receives more than 3 million income tax returns annually.

Letter from Denver: Historic mint still coins a pretty penny

The furnace glows a toasty 1,314 degrees Fahrenheit. The silvery disks inside aren’t meant to melt, just soften, ahead of being stamped. That’s when they turn from a mix of metals into currency – in this case, quarters.

The U.S. Mint at Denver, on average, cranks out 10 million coins a day (roughly $1 million). Along with special collections, this mint in the Colorado capital produces circulating coins used in everyday transactions. Unless those pennies, nickels, and dimes hide in the creases of your couch.

Millions of Americans today, who can afford it, live far removed from cash. Many have filed their taxes due this week as pixels on screens. At the vanguard of this digitization of dollars is Colorado, with an annual blockchain conference and a governor who openly promotes cryptocurrency. Coloradans can even pay their state taxes that way.

But here at the century-old Denver Mint, the physical legacy of money as well as its future for commerce and society are on display. For some people, physical currency is crucial for daily life.

In 2021, the “unbanked” share of the population stood at 4.5% of U.S. households – nearly 6 million, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Eliminating cash would further shunt those people out of the economy, says Bill Maurer, director of the Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion at the University of California, Irvine.

For others, in an era when “frictionless” payment implies distance from human touch, there’s comfort in something you can hold in your hands.

After all, coins are “history in your pocket,” says Tom Fesing, chief of public affairs at the Denver Mint.

He scoops up quarters to pour into my palm. They glint, still warm, like stones left in the sun.

A golden beginning

Established by Congress in the 1860s, the first federal mint in Denver tested the gold brought in by eager miners. Today’s boxy building downtown, in operation since 1906, is modeled on the Medici Riccardi palace of Renaissance Italy. Flanking the granite exterior is a spiked wrought-iron fence. Nearly a fifth of the country’s gold reserves sit inside, Mr. Fesing says.

A brisk-paced former tour guide, Mr. Fesing leads me beyond the arched salmon ceilings of the grand hallway, part of a route that the public can visit for free. We gather eye, foot, and ear protection for the production floor, which jangles and clangs like a metal hailstorm. During the pandemic, when consumers and their cash stayed home, the Denver Mint upped production from five to seven days a week to offset poor coin circulation.

Basically, circulating coins here begin as faceless “blanks.” Several steps later, a press stamps their heads and tails (at a swift 12.5 coins a second). Fulfilling monthly orders from the Federal Reserve, the mint sorts and ships money off to destinations generally west of the Mississippi River. The U.S. Mint at Philadelphia handles east of the Mississippi.

Coins aren’t without controversy. Though offset by more lucrative products, the unit costs of pennies and nickels continue to exceed their face value – 3 cents and 11.5 cents respectively, according to the U.S. Mint’s 2023 report. Some Americans, citing frustration over the cost and nuisance of the small coins, have called on the government to retire them.

Though their relevance is questioned, coins are “one of our most ancient technologies,” says Professor Maurer of the University of California, Irvine. “As a human invention, they’re a relatively successful one and a durable one.”

Largely unchanged since production began around 500 or 600 B.C.E., the rounded form of coins is considered especially tamper-resistant. Cash is key for national emergencies, he adds, and vital for U.S. households without easy access to banking.

Under Gov. Jared Polis, Colorado is minting history of its own with digital assets. Colorado has recently allowed the payment of state taxes with cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency is a type of virtual currency whose security comes from encryption. (Colorado receives digital assets converted into dollars via PayPal.)

But adoption has been slow since the option began in September 2022. As of last week, the Colorado Department of Revenue estimates that state income taxes have been paid via cryptocurrency 28 times. The state receives more than 3 million income tax returns annually.

At least for now, humans are still relevant at the Denver Mint, even among its maze of pale blue machines. One coin manufacturer, Carl Morgan, spot-checks a quarter that debuted this year featuring Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color elected to Congress. A hand-held device seems to assure him that the lettering is well aligned.

Employees here, and visitors like me, are subject to a no-coins-in, no-coins-out policy, and pass through security entering and exiting the building. Mr. Morgan puts the safeguards into simple terms.

“Any other job,” he muses, “if you ran across a pile of money on the floor, that’d be a good day.”

For all its rules, the place also has its quirks. A throwback to an older age, a mannequin guards the grand hallway, smirking in a sentry box. In his lap lies a replica machine gun.

He’s called Lefty Luger, says Mr. Fesing. “Because he’s left-handed.”

A real live police officer reviews my photos before I get to leave. All the shots seem to pass muster; I’d obediently avoided surveillance cameras and vaults. Exiting security onto the sidewalk, I’m as cents-less as when I arrived.

I can’t shake the sensation of a fistful of penny blanks: the smooth scales of a fish.

Should you trust the Monitor? We asked one media watchdog to audit us.

The Monitor has long respected the work of Trusting News, which aims to help news organizations build trust with readers. So as part of our Rebuilding Trust series, we asked them: Is the Monitor trustworthy? Here’s their response.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Joy Mayer Contributor

-

Mollie Muchna Contributor

We know identifying responsible, credible journalism in a sea of agenda-driven messages and misinformation can be exhausting and overwhelming. As people who study trust in news and train journalists to demonstrate credibility, we believe all people should have access to factual, evenhanded news that reflects their priorities and values.

That’s why we were thrilled when Editor Mark Sappenfield invited our team at Trusting News to do an audit of the newsroom’s trust and transparency efforts as part of the staff’s Rebuilding Trust series. We have held The Christian Science Monitor up as an example for the news industry to follow, and we were eager to take a deeper dive into the newsroom’s practices.

The short answer: The Monitor is a trustworthy news source, based on a foundation of solid ethics and a public service mission. They could make their credibility easier for the audience to detect, and we’re sending them suggestions along those lines.

Should you trust the Monitor? We asked one media watchdog to audit us.

We know identifying responsible, credible journalism in a sea of agenda-driven messages and misinformation can be exhausting and overwhelming. As people who study trust in news and train journalists to demonstrate credibility, we believe all people should have access to factual, evenhanded news that reflects their priorities and values.

That’s why we were thrilled when Editor Mark Sappenfield invited our team at Trusting News to do an audit of the newsroom’s trust and transparency efforts as part of the staff’s Rebuilding Trust series. We have held The Christian Science Monitor up as an example for the news industry to follow, and we were eager to take a deeper dive into the newsroom’s practices.

The short answer: The Monitor is a trustworthy news source, based on a foundation of solid ethics and a public service mission. They could make their credibility easier for the audience to detect, and we’re sending them suggestions along those lines.

What our trust assessment found

We based our evaluation on 10 themes we have found are foundational when it comes to building trust between journalists and the public. We were able to find answers to some of our questions by taking a close look at the Monitor’s online content, and for others, we relied on interviews with staff members.

- A solid About Us page. The Monitor has a great About Us page that includes the organization’s mission, perspective, and voice, with a section dedicated to answering questions about the publication's name and its affiliation with the church. It could be improved by linking to a Contact Us page to invite input from readers and by including ethics policies.

- Ethics policies. The Monitor has many ethically sound internal policies and principles that guide its reporting, including a commitment to correct errors and a form for readers to submit corrections. However, many of its internal policies are not public-facing. Publishing ethics policies would invite important public scrutiny and accountability.

- Ownership and funding. The Monitor does get on the record about its name and relationship with the Christian Science Church in an FAQ on its About Us page. We recommend the Monitor go deeper in its transparency around its funding and ownership by explaining how that relationship does and does not influence coverage, and then regularly share that explainer back with readers.

- Daily transparency. While readers consume Monitor news, they can also learn how the Monitor operates. The newsroom already has several standard transparency practices that can serve as a model for the rest of the news industry. Staffers in the newsroom routinely insert explainers into stories sharing why they are doing the story and the values behind their coverage. The newsroom also produces an array of columns and podcasts that lift the curtain on its reporting processes and other behind-the-scenes work. As the Monitor publishes more information about ethics policies, we hope those are shared within and alongside daily stories as well.

- Audience engagement and input. The Monitor has a feedback form embedded on its website, which appears at the bottom of every article and prompts people to reply with feedback, corrections, or questions. It appears the staff also makes it a priority to be responsive to its readers.

- Opinion and commentary. It is vital for newsrooms to clearly delineate between straight news and opinion pieces so readers know what to expect. The Monitor does this, with stories that are part of the commentary or Monitor’s View sections being labeled as such. Those labels would be even more effective if they were written into headlines, so that if an opinion story is shared by a reader on Facebook, for example, it is clear that the piece is designed to share a perspective or opinion.

- Explaining the Monitor’s value. Telling the story of the values behind its news is one of the Monitor’s real strengths. It’s visible in the mission language on its About Us page, in staff columns, and through its values labels. We hope more newsrooms will follow this lead.

- Fairness in coverage. From talking to staffers and reviewing Monitor content, we can tell journalists at the Monitor care deeply about being fair and accurate. They want their coverage to feel fact-based and evenhanded to people who see the world differently. The newsroom could do a better job talking publicly about what that looks like day to day and pointing to specific stories of evidence of that commitment.

- Staff diversity. It sounds like there is a fairly diverse group of journalists at the Monitor, in terms of racial diversity, lived experiences, religious beliefs, and viewpoints. However, staff acknowledged that it could be more diverse and that leadership wants to move in that direction. At Trusting News, we often ask this question: Who would feel seen and understood by your coverage, and who might feel neglected or misrepresented? Some newsrooms are not interested in having that conversation in a meaningful way, or equipped to grapple with what they might find out if they examined it. Our impression is that the Monitor is more prepared than many other newsrooms to make that question and the resulting answer part of newsroom routines.

- Newsroom culture. Part of reflecting diverse viewpoints is creating a newsroom culture in which journalists with different lived experiences and perspectives feel encouraged to challenge the status quo or dominant assumptions that might be driving news coverage. This is hard for outsiders to assess, but our sense is that the Monitor has a stronger foundation than many other newsrooms in this area.

We shared more detailed recommendations with the newsroom team with the hope that they continue to evolve their trust and transparency practices.

What the public deserves

In a world in which news consumers are confused and exhausted by information, responsible journalists should be transparent and proactive about why they are worthy of trust. We believe all people should have access to journalism that works to earn their trust, is responsive to their needs, and reflects their diverse priorities and values.

The Monitor is a newsroom we’re proud to work alongside. We hope you will hold its journalists accountable for living up to the high standards they set for themselves.

We also hope that local newsrooms in your communities are working to earn your trust as well – regularly examining what they could do to strengthen their credibility and better reflect the communities at large. If they are, they will welcome your input and questions, and we encourage you to be in touch with them.

Joy Mayer is the director of Trusting News. She founded the project in 2016 after a 20-year career in newsrooms across the United States and teaching at the Missouri School of Journalism. Mollie Muchna is the project manager at Trusting News. She joined the project in 2019 after working as a reporter, editor, and producer in newsrooms across the Southwest. They can be reached at info@TrustingNews.org.

This article was not edited by the Monitor, apart from several style changes to make it consistent with the Monitor Stylebook.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why many in Iran root for Israel

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

This past weekend, when Iran attacked Israel directly for the first time, reaction among Iranians was not exactly what the regime in Tehran expected. Yes, many people rushed to buy gasoline and food, fearing a wider war. Some expressed a deep dread of war, recalling a 1980s conflict with Iraq. Yet one common response, expressed online and in street graffiti, was hope that Israel would somehow bring down the regime.

That sentiment was so prevalent that Iran’s rulers quickly issued a notice urging citizens to report any support of Israel, saying it was a crime.

For all the gloom among Iranians – about the economy, suppression of women, and Iran’s role in regional conflicts – they show an independent streak that’s evident in a constant redefining of their nation’s identity.

Years of protest by Iranians in favor of the freedom to choose their own government has led to a more inclusive nationalism. One prominent critic, the exiled soccer star Ali Karimi, uploaded a picture after the attack on Israel that stated, “We are Iran, not the Islamic Republic.”

Why many in Iran root for Israel

This past weekend, when Iran attacked Israel directly for the first time, reaction among Iranians was not exactly what the regime in Tehran expected. Yes, many people rushed to buy gasoline and food, fearing a wider war. Some expressed a deep dread of war, recalling a 1980s conflict with Iraq. Yet one common response, expressed online and in street graffiti, was hope that Israel would somehow bring down the regime.

That sentiment was so prevalent that Iran’s rulers quickly issued a notice urging citizens to report any support of Israel, saying it was a crime.

For all the gloom among Iranians – about the economy, suppression of women, and Iran’s role in regional conflicts – they show an independent streak that’s evident in a constant redefining of their nation’s identity. Well before the weekend attack, for example, one poll showed more than a third of people have a positive view of Israel.

Years of protest by Iranians in favor of the freedom to choose their own government has led to a more inclusive nationalism. One prominent critic, the exiled soccer star Ali Karimi, who has 15 million Instagram followers, uploaded a picture after the attack on Israel that stated, “We are Iran, not the Islamic Republic.”

Perhaps the biggest critic who remains free in Iran is Shaikh Abdol-Hamid, the top Sunni leader in a country controlled by Shiite clerics. In a speech last month, he said, “Today, Iranians love each other more than ever.” He asked for an inclusive government that respects the will of all Iranians.

“We share common interests with all people of the world,” he added. “We respect and love all people.”

Iran’s strength over decades has been its ability to fuse the identities of many faiths, ethnicities, and languages into a plurality that embraces one country. The current Islamic regime, like the secular monarchy before it, has not been able to impose a singular identity from on high. If many Iranians extend a welcoming hand to Israel, that is simply part of their identity.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The discovery that brings personal growth

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Getting to know our spiritual nature as God’s children – and honestly striving to live consistently with that nature – empowers us to be and do good, and to know our God-given worth.

The discovery that brings personal growth

We all yearn for personal growth, yet may wonder about the best way to accomplish it. Many – myself included – have found it encouraging to step back occasionally to acknowledge any progress gained. Noting what has been right and good in one’s life can be substantially more conducive to personal growth than focusing only on regrets and failures.

I’ve also found that Christian Science takes this to the next level, offering an approach – a prayerful approach – that does quite a bit more than just patting ourselves on the back or giving ourselves a good pep talk.

It’s based on the premise that God doesn’t create us as flawed, material beings who hope beyond hope to become better someday, somehow. Rather, we are God’s children, entirely spiritual – and the spiritual perfection of God Himself is expressed in His offspring.

From that perspective, growth and progress in life aren’t about becoming better mortals; they’re about discovering, and demonstrating, our true, spiritual nature as the expression of God, good.

This is the basis on which Christ Jesus helped and healed so many. He taught, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48). Today, too, we can acknowledge in prayer God’s perfection shining within ourselves and others, as God’s spiritual offspring. This is not only loving, but constructive and healing.

In junior high school, I felt so far behind other people. It seemed everyone else was able to make meaningful contributions, but I didn’t see myself that way.

Thinking this way was like dragging a heavy anchor around. It was terrible to feel worthless. But as a Christian Science Sunday School student, I knew that there was help to be found in turning to God.

So I prayed to get to know myself better the way God knows us. I realized that God could never superimpose failings or limitations onto or around His precious children. In fact, our identity as His children isn’t intertwined with even a molecule of matter with its limitations, because God is Spirit, and there’s no limitation in infinite Spirit.

As I prayed with these ideas, my whole outlook and experience changed. From that point forward, things turned completely around – I was my joyful self again, as God made me.

The founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, makes this perceptive statement: “The divine demand, ‘Be ye therefore perfect,’ is scientific, and the human footsteps leading to perfection are indispensable. Individuals are consistent who, watching and praying, can ‘run, and not be weary; ... walk, and not faint,’ who gain good rapidly and hold their position, or attain slowly and yield not to discouragement” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” pp. 253-254).

In our unity with God, there are no gradations. Right in this very moment, our true state of being is “perfect, even as [our] Father which is in heaven is perfect.” Humbly acknowledging that we exist to show forth the nature of God, good, is a progressive step. God is the source of existence, and our true purpose is to glorify God’s good nature. God’s pure goodness is expressed in each of us now and always, and nothing can ever stop what God is doing. When we aim to live consistently with that spiritual reality, goodness and spiritual growth in our daily life naturally come to light.

So personal improvement isn’t about taking a journey from material imperfection toward spiritual perfection. It’s about an ongoing, inspired discovery of our one delightful, God-given state of existence. Whenever we pause to assess how things are going for us, we can recognize prayerfully that in God, we have been given not material life, but the pure, constant goodness of spiritual life in Him. This gives us confidence and courage as we move through each day.

Viewfinder

Blink and you’ll miss them

A look ahead

Thank you for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, staff writer Cameron Pugh will share an interview with a playwright about adapting the beloved young-adult classic, “The Outsiders,” into a Broadway musical.

And we have an editor’s note: An article from the April 10 Daily, “Exhibit with 700 artifacts aims to change Holocaust denial,” included a 2023 Economist/YouGov survey that said about 20% of young Americans were Holocaust deniers. The opt-in methodology used in the survey is flawed, a Pew Research Center study found. Young respondents to such polls are “far more likely to say the Holocaust was a myth than those surveyed by other methods,” The Economist said in a 2024 editor’s note.