- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Pay was starting to outpace US inflation. Can it keep up?

- Today’s news briefs

- Israel’s retaliation dilemma: Listen to instincts or allies?

- Biden and Trump on border crossings and immigration

- ‘Stay gold, Ponyboy’ ... set to music? ‘The Outsiders’ comes to Broadway.

- Pulling up concrete and putting solar on renters’ roofs

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Missile strikes, retaliation, and the possibility for change

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Shoshanna Solomon’s first story for the Monitor is ostensibly about retaliation. How will Israel respond to Saturday’s missile attack from Iran? But more deeply, it’s really about the potential for change.

Can Israel not respond, or is retaliation too ingrained in its current mindset?

What makes the question interesting is the context. The missile strike largely failed, thanks in part to help from allies that include former enemies, like Jordan and (to some extent) Saudi Arabia. That, in itself, is an intriguing testament to the possibility for change.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Pay was starting to outpace US inflation. Can it keep up?

Gains in real wages often happen during relatively rare bursts. For a while, it looked like one of those accelerations in worker buying power was underway after the pandemic. But an uptick in inflation threatens it.

-

Leonardo Bevilacqua Staff writer

Persistent and stubborn inflation is not only upsetting investors, who are hoping for interest rate cuts from the Federal Reserve; it’s also threatening to undermine one of the most positive trends underway in the U.S. economy: the rise in workers’ real wages.

Real – or inflation-adjusted – pay took a tumble for a time during the pandemic, but a year and a half ago, that equation flipped and workers’ buying power began to rise again. By January, it looked as though their real wages were poised to resume a historic surge that started in the mid-2010s.

Now, that progress has stalled.

Soaring auto-insurance rates last month surprised many analysts. Housing costs pose an even bigger challenge for young workers. Average real wages, which hit $11.14 an hour in January, had eased slightly to $11.11 by March.

“We had some good progress being made,” says Mark Hamrick, an economic analyst at Bankrate. “In recent months, that progress has stalled.” That means the Federal Reserve may hold off cutting interest rates until it’s clear inflation will continue to fall.

Pay was starting to outpace US inflation. Can it keep up?

Stubborn inflation is not only upsetting investors, who are hoping for interest rate cuts; it’s also threatening to undermine one of the most positive trends in the U.S. economy: the rise in workers’ real wages.

Real – or inflation-adjusted – pay took a tumble for a time during the pandemic, as prices rose far faster than Americans’ wages and salaries. But a year and a half ago, that equation flipped, and workers’ buying power began to rise again. By this past January, it looked as though their real wages were poised to resume a historic surge that started in the mid-2010s.

Now, that progress is threatened. Average real wages, which hit $11.14 an hour in January, had eased to $11.11 by March. Whether that stagnation is temporary or more lasting is anybody’s guess. But one thing is clear: If inflation doesn’t fall, it will be harder for Americans’ real pay to continue rising.

“We had some good progress being made,” says Mark Hamrick, senior economic analyst at Bankrate, which tracks savings and lending rates that banks offer to consumers. “In recent months, that progress has stalled.” That means the Federal Reserve may hold off on cutting interest rates until it’s clear inflation will continue to fall.

One reason inflation isn’t falling: soaring auto-insurance rates. Last month, they jumped much higher than many analysts expected. One Connecticut resident was so shocked at the nearly 42% rise in her auto renewal quote that she’s switching insurance companies.

Unlike food and energy prices, which vary a lot from month to month, the cost of insurance and other goods and services like rent and health care makes up what’s known as core inflation. Economists keep a close eye on it. Since hitting an annualized high of 6.5% two years ago, core inflation has fallen halfway to the 2% annual inflation target that the Federal Reserve has set. While that’s impressive, it still may prove too high for Americans’ pay gains to keep up with.

In March, for example, a 0.3% monthly gain in average wages was swamped by a 0.4% rise in the core consumer price index (CPI), the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported last week. So while an average worker making $5,000 a month got a monthly bump of $15, it doesn’t cover the additional $20 that inflation added to their expenses.

Housing hurdles

A bigger reason for stubborn inflation: the rising cost of housing. Bryan Whittington left his dream job as a zookeeper for higher pay and more flexibility as a medical school coordinator at Tulane University. But a 25% rise in rent over five years has crimped his spending power. “It’s kind of disheartening,” he says. “There’s no way I can keep up with that pace with my job.”

Inflation is so persistent that some analysts suggest that the Federal Reserve may have to raise interest rates rather than lower them, as many investors are hoping for.

The post-pandemic outlook for real wages looks confusing, in part because two forces are competing for dominance: a persistent worker shortage that boosts wages, and an unexpectedly buoyant economy, which helps keep inflation high.

It’s “still to be determined whether or not we’re going to be back on that same trend we were before the pandemic,” says Chloe East, co-author of a 2023 Brookings Institution study on inflation and wages and an economics professor at the University of Colorado in Denver.

For much of the past four decades, this tug of war between wages and inflation has been a near stalemate, punctuated by short bursts of progress when Americans’ real pay went up. That happened in the mid-1980s, the late 1990s, and again around 2015, when the economy finally shook off lingering effects of the Great Recession. During the last year and a half of the Obama administration and the first three years of the Trump administration, average real wages went up by a dollar an hour – in half the time it took for the previous dollar-per-hour raise. Then the pandemic hit.

First, lockdowns pushed millions of low-wage employees out of work. When they began to trickle back to work, high inflation kicked in, reversing pay gains. Then in mid-2022, the average real wage began climbing again. Averages, however, miss important differences among Americans.

Rising costs hurt renters, help homeowners

For one, the rising cost of housing hurts renters, but it actually helps older, established homeowners, because home values go up while the real cost of mortgages goes down. In another twist, the rise in real pay that started in the mid-2010s has helped low-income workers far more than high-income ones, says Professor East of the University of Colorado.

That’s partly because low-paid workers have been in demand as restaurants, stores, and other services reopened after the pandemic. Low-paid workers have also been helped by minimum wage boosts. In January, minimum pay rose in 22 states and is expected to go up in three others later this year.

Higher pay helped lure Mitchell Redd from his native Mississippi to Atlanta, where he now works as a research analyst for the Judicial Council of Georgia. Just before he arrived in 2022, Georgia bumped up pay for all state employees and teachers by $5,000 a year. That pushed Mr. Redd’s income to $49,000 a year, far above anything he could find in Mississippi. “It’s kind of where I wanted to start my career,” he says.

Last month, Georgia passed an additional 4% raise for state employees, which the governor has been pushing to retain quality workers.

Still, rising prices cut into those pay gains.

In November, high rent forced New Yorker Eric Doce out of his apartment in Flatbush, Brooklyn, and into his grandmother’s home in Jackson Heights, Queens. A harpist by training, he works full time as an Uber Eats courier. After the city capped his hours and the company cut his pay, he figures he can clear over $30,000 a year. It is hard – with that salary – to make ends meet in one of America’s most expensive cities.

“I’ve just been here all my life,” he says. “Recently, I have seriously considered going to take a breather and move somewhere else.”

Today’s news briefs

• House speaker pushes foreign aid vote: Mike Johnson unveiled a plan to squeeze through aid for Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan despite the House’s political divides on foreign policy.

• Supreme Court obstruction case: The justices hear the first of two cases that could affect the criminal prosecution of former President Donald Trump for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

• Pro-Palestinian U.S. protests: Demonstrations temporarily shut down travel at the Chicago O’Hare International Airport and onto the Golden Gate and Brooklyn bridges.

• Famous Danish landmark burns: A fire in Copenhagen’s Old Stock Exchange causes the building’s iconic dragon-tail spire to collapse.

Israel’s retaliation dilemma: Listen to instincts or allies?

A deterrence doctrine is so entrenched in Israel that even moderate leaders will find it hard not to support some retaliation against Iran. But the success of a historic U.S.-led defensive alliance may offer a new approach.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Shoshanna Solomon Contributor

As Iranian drones and missiles flew toward Israeli skies late Saturday night, the decision before Israel’s government seemed straightforward – and in line with Israel’s military doctrine: when and how to retaliate.

But the success of the measures put in place to help Israel thwart the attack, including a U.S.-led international and regional coalition, has paradoxically made Israeli decision-making more complex. Government ministers convening for a third day Tuesday faced a dilemma: whether to heed pressures not to retaliate at all.

Experts say it’s most likely Israel will strike back in some way, though war Cabinet Minister Benny Gantz said Tuesday that Israel will choose the time and place to respond, suggesting it was at least weighing the calls for restraint.

Israel’s policy has traditionally been that of “deterrence and renewal of deterrence,” says Professor Eitan Shamir, director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University. “We see deterrence as a commodity, which has a shelf life and gets eroded,” he says. “That is why every now and then, you need to renew it by taking actions.”

Yet the thwarting of Iran’s barrage has already created a different kind of deterrence. “Israel should have strategic patience,” he says, and leverage the alliance to promote its interests.

Israel’s retaliation dilemma: Listen to instincts or allies?

As explosive drones and missiles flew toward Israeli skies late Saturday night in an unprecedented attack launched from Iranian soil, the decision before Israel’s government seemed straightforward – and in line with both Israel’s mindset and military doctrine.

When and how to retaliate.

But the overwhelming success of the measures put in place to help Israel thwart the attack – including an also unprecedented, U.S.-led international and regional coalition – has paradoxically made Israeli decision-making more complex. Government ministers convening for a third day Tuesday faced a dilemma: whether to heed international pressures not to retaliate at all.

Still, the more likely response, experts say, is that Israel will strike back in some way. That would follow the nation’s traditional policy of deterrence, even if this time, they say, it might be wiser to show strength via restraint.

Israel’s policy since its founding has been that of “deterrence and renewal of deterrence,” says Professor Eitan Shamir, director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University and a former senior strategic affairs adviser in the Prime Minister’s Office.

“We see deterrence as a commodity, which has a shelf life and gets eroded,” he says. “And that is why every now and then you need to renew it by taking actions, so the other side understands that you have not weakened, that you are not afraid.”

This deterrence doctrine is so entrenched in the nation’s DNA, he says, that even moderate leaders in Israel will find it hard to forge a different path.

Coalition defense

The attack Saturday from Iran, Iraq, Yemen, and Lebanon included some 350 drones, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and rockets, with about 60 tons of explosive materials, the Israel Defense Forces said.

Iran said the attack was in retaliation for Israel's killing of senior Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commanders in an airstrike on Iran’s diplomatic mission in Damascus, Syria, on April 1. Iran also said its response to the killings was now concluded, but warned that should Israel retaliate, it could face a much larger attack.

Israel said 99% of the Iranian barrage was intercepted by Israel and the U.S.-led coalition, which included Britain, France, and some of Israel’s Arab neighbors, including Jordan and to some extent Saudi Arabia. It marked the first time such a group worked together against Iran and its proxies.

Voices counseling Israel to avoid escalation and preserve that coalition have been constant. They ranged from U.S. President Joe Biden urging Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu immediately to “take the win,” to German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock calling on all sides Tuesday to avoid widening the conflict, saying she would travel to Israel to convey “Germany’s full solidarity.”

Amid a whirl of reports that the Cabinet’s decision was tilting toward retaliation, the Israel Defense Forces chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Herzi Halevi, said Monday on a visit to the Nevatim air base, which sustained minor damage from the barrage, that “Iran will face the consequences for its actions.”

Yet Tuesday, war Cabinet Minister Benny Gantz suggested Israel was at least weighing the calls for restraint, saying Israel will choose the time and place to respond, and would work with the United States to build an anti-Iran alliance.

Regional concerns

Israel’s Kan public TV channel said Israel has sought to reassure its Arab neighbors that its response will not put them at risk for Iranian retaliation. Haaretz reported there was wide consensus amid the political and security leadership for an attack, albeit a measured one that would not set the region alight.

“It is very hard to know what Netanyahu will do,” says Amos Yadlin, a former Israeli air force general and a former head of military intelligence. “On the one hand Iran is his obsession, but he will also want to be very careful not to trigger a wider regional war.”

Even if the Iran attack was foiled and caused just minor damage, Iran sees its attack as a “victory,” Dr. Eyal Pinko, a senior research fellow at the Begin-Sadat Center, said in a webinar Tuesday. And that is why, he said, “many voices inside the Israeli government” see retaliation as essential.

Israel has a range of targeting options, says Professor Shamir. It could strike in Syria or Lebanon, as it has in the past, or target sites in Iran, the most ambitious and “extreme” being facilities affiliated with its nuclear program. But that is not likely, he says.

“The timing is not right,” Professor Shamir says. “The result would be a total war with Iran, and we are not ready for that. We are submerged in Gaza, we have the situation in the north that we have not resolved, and so to enter a war with Iran now would be entering a vortex from which we don’t know how we will exit.”

Hitting a major, nonnuclear target on Iranian soil would send a clear deterrence signal to Iran but would not provide Israel any great strategic benefit, he says. “The importance of such a kind of move is ... symbolic, raising Israeli morale, showing the enemy that you can reach them. The question is if at this moment it is worth the price, as the strategic benefit is not very large.”

Outside Mr. Netanyahu’s right-wing government, some political leaders counseled caution.

Thinking there must be a show of force is a “childish way of thinking,” says reserve Maj. Gen. Yair Golan, who is running for the leadership of Israel’s once-dominant but now nearly invisible Labor Party.

Attacking Iran will only be an “act of vengeance that brings us nowhere,” he says, leading to a war that “we cannot win,” a very risky undertaking after six months of a bloody conflict with Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in the north.

“Strategic patience”

There is a precedent of Israeli restraint in the face of an attack, with hawkish Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir in 1991 heeding a U.S. request to hold fire after a barrage of Scud missiles from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and enabling the U.S.-led coalition to respond.

If Israel does indeed attack, it should do so only in close coordination with the U.S., says Mr. Yadlin, the former air force general.

“Any unilateral action by Israel would have lower chances of success, harm President Biden’s coalition against Iran efforts, and escalate events also in the West Bank and the north of Israel,” he says. “All of this will boost [Hamas leader] Yahya Sinwar, who has sought from the very beginning of the war to make it a regional conflict.”

Instead of retaliating immediately, says Professor Shamir, Israel should play the waiting game and react as it has been doing until now with its shadow war with Iran.

“Israel should have strategic patience,” he says, and leverage the unprecedented regional alliance that has now emerged to promote its interests.

Israel and the alliance’s success against Iran’s barrage, he says, has already created a different kind of deterrence.

The alliance, and a moment of renewed sympathy for Israel, could help Israel resolve its conflict with Hezbollah in Lebanon and achieve its war aims in Gaza, he says.

“Israel must now capitalize politically from Biden’s support and the sympathy we have regained from the West,” says Professor Shamir. “In Gaza, Israel is seen as Goliath versus the Palestinian David. ... But against Iran, Israel is once again a David, garnering sympathy.”

The Explainer

Biden and Trump on border crossings and immigration

Immigration is a top issue in the U.S. presidential race amid questions about the pace of illegal border crossings and candidate track records. Here’s what the available data tells us.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Caitlin Babcock Staff writer

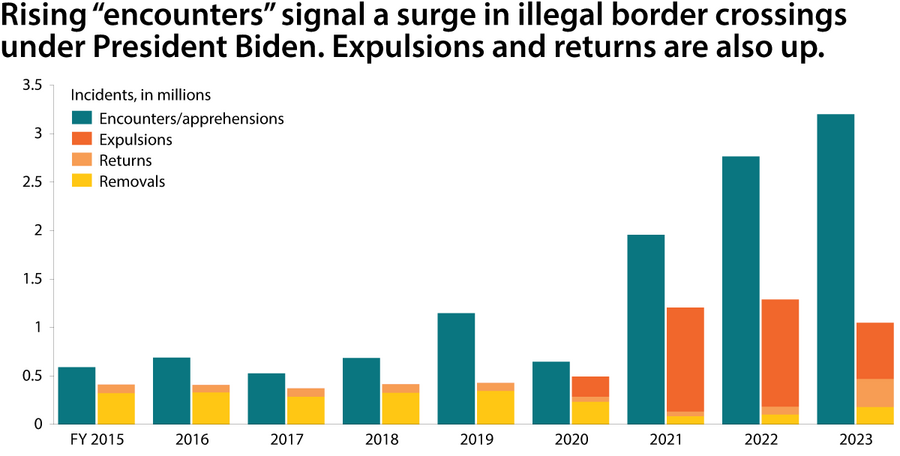

How does the rate of illegal immigration under President Joe Biden compare with that of his predecessor and likely opponent, Donald Trump?

Republicans blame the record levels of illegal immigration on President Biden softening U.S. border security and reversing Trump policies they say had been effective at decreasing flows. Democrats, who describe former President Donald Trump’s policies as inhumane, say the GOP is inflating both the numbers and the blame – and ignoring the impact of a rise in forced global migration.

A report last month from the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute says “the rapid increase in arrivals in recent years reflects ongoing crises in the Americas,” and instability elsewhere in the world. Other reasons cited include a strong U.S. economy, sophisticated smuggling networks, and the perception that the Biden administration’s policies are more welcoming.

Overall, illegal crossings have increased significantly during the Biden administration, but some Republicans are overestimating the net influx of unauthorized migrants.

Biden and Trump on border crossings and immigration

Immigration ranks in several major polls as the No. 1 national concern for voters leading into this year’s U.S. presidential election. That amplifies the question, how does the rate of illegal immigration under President Joe Biden compare with that under his predecessor and likely opponent, Donald Trump?

Republicans blame the record levels of illegal immigration on President Biden softening U.S. border security and reversing Trump policies they say had been effective at decreasing flows. Democrats, who describe former President Trump’s policies as inhumane, say the GOP is inflating both the numbers and the blame – and ignoring the impact of a rise in forced global migration.

A March report from the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute says that “the rapid increase in arrivals in recent years reflects ongoing crises in the Americas” and instability elsewhere in the world. Other reasons cited include a strong U.S. economy, sophisticated smuggling networks, and the perception that the Biden administration’s policies are more welcoming.

Republicans focus on another explanation. They say Mr. Biden has taken 64 actions, including revoking numerous Trump policies, that have incentivized illegal immigration and undermined border security.

Here we examine the available data, as well as key immigration and border policies under each presidency.

Q: How do the Trump and Biden levels of illegal immigration compare?

The U.S. government does not publish data on the net number of migrants who enter illegally and remain in the country. The main metric U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) tracks is how many “encounters” there are between its agents and migrants seeking to cross illegally. (This is a measure of individuals encountered, so if Border Patrol encounters a group of 10 migrants, that counts as 10 encounters.)

Under the Biden administration, there have been 6.4 million encounters outside official ports of entry along the southern border so far, with the yearly average more than quadruple that of the Trump administration, according to a Monitor analysis of CBP data.

In addition, CBP agents have registered more than 1.6 million encounters at official ports of entry with migrants deemed “inadmissible,” some of whom are allowed to temporarily enter the country.

Border Patrol also tracks “gotaways,” migrants seen crossing by border agents who are too occupied to respond, or picked up by cameras and sensors. Those totaled nearly 400,000 for the most recent fiscal year reported, 2021, which is more than double the highest annual total during the Trump administration. There is also an unquantifiable number of undetected gotaways.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

Some Republicans claim that Mr. Biden has let in as many as 8 million or 9 million migrants. However, it’s not accurate to simply add up encounters and gotaways as a proxy for illegal immigration.

One reason is that since the pandemic, more migrants have tried multiple times to enter, inflating the number of encounters. Also, many of the encountered migrants aren’t permitted to stay in the country.

Others gain legal status. Hundreds of thousands have claimed asylum and been allowed to remain while their cases are pending. Furthermore, migrants arriving at ports of entry are often participating in humanitarian parole programs, which the Biden administration expanded and considers a method of legal immigration. A federal judge upheld one such parole program in March.

Some groups have tried to gauge the net number of people who cross into the United States illegally and remain in the country, despite lack of government data. Last year, the Center for Immigration Studies, which supports tighter border control, gave a preliminary estimate that the number of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. rose by 2.4 million (to 12.6 million total) in the first 27 months of the Biden presidency. Recent research by investment bank Goldman Sachs said the rise in unauthorized immigration was a key factor in driving net immigration to its highest level in two decades last year.

The Migration Policy Institute, meanwhile, estimated the 2021 unauthorized immigrant population at 11.2 million and noted “larger annual growth than at any point since 2015.” The institute indicated that while that could increase the overall population of unauthorized immigrants, the net change depends on numerous factors, including emigration rates.

Overall, illegal crossings have increased significantly during the Biden administration, but some Republicans are overestimating the net influx of unauthorized migrants.

USAFacts, Pew Research Center

Q: How have asylum policies changed under each administration?

Mr. Trump significantly limited the ability of migrants to claim asylum, or protection in the U.S. due to persecution or a credible fear of persecution in their home countries.

Under the Trump administration, migrants were deemed ineligible for asylum if, after leaving their home countries, they had traveled through one other country or more before reaching the U.S. without applying for asylum in at least one.

The Biden administration has kept a portion of that ban intact, but only for migrants who enter outside official ports of entry. It now allows asylum-seekers – regardless of whether they have applied in third countries – to make an appointment at a U.S. port of entry through the expanded use of a CBP phone app. Another key difference is that Mr. Trump also required some asylum-

seekers to remain in Mexico instead of the U.S. while their cases were pending, a policy that the Biden administration ended in 2022.

The number of people granted asylum per year dipped during Mr. Biden’s first year in office, after the global pandemic shutdown, but then more than doubled in his second year. While the number granted asylum is not yet available for 2023, the number of asylum applications U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services received that year was nearly double a record high from the year before, compounding court backlogs.

Q: What is immigration “parole,” and how have Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump used it?

The Immigration and Nationality Act has for decades granted presidential administrations discretion to temporarily allow entry to noncitizens via parole “only on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.”

Senate Republicans say President Biden has abused that provision to welcome immigrants en masse. In January 2023, his administration created a program that allows up to 30,000 total individuals each month from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to travel to the U.S. and seek parole.

Some 301,000 migrants were paroled at official ports of entry in fiscal 2023; the highest annual total under Mr. Trump was 75,000.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Syracuse University

Parole has traditionally occurred at official ports of entry, including airports. In a significant shift, the Biden administration has also granted parole in between ports of entry, allowing in nearly 290,000 such migrants during the first two years, according to government data compiled by Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a data research center at Syracuse University.

Q: What makes it difficult to tally the current number of unauthorized immigrants?

The most obvious reason is that Border Patrol doesn’t catch or even see every migrant who crosses illegally.

Second, many unauthorized immigrants came to the U.S. legally but overstayed their visa or other provision for legal residence.

Third, people flow out of the U.S. as well as in, with emigration fueled by migrants’ decisions to return to countries of origin or by enforcement policies.

Fourth, while the U.S. government publishes the number of encounters, it does not specify how many unique individuals are encountered, or how many of those encountered are allowed to remain in the country, making it impossible to calculate the precise scope of net illegal immigration.

Under the pandemic-era rule known as Title 42, in place until May 2023, Border Patrol agents could expel migrants on public health grounds. But migrants could try again without penalty, driving a fourfold increase in people trying to enter the U.S. illegally more than once per fiscal year. The rate rose to 27% in 2021, from 7% in 2019.

Bottom line: While we don’t know exactly how many unauthorized immigrants are added to the U.S. population each year, an array of different metrics signals a significant increase under Mr. Biden.

‘Stay gold, Ponyboy’ ... set to music? ‘The Outsiders’ comes to Broadway.

What does a nearly 60-year-old story have to say about today? Now a Broadway musical, “The Outsiders” speaks to a divided nation about the dangers of factions and the joys of found family.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

S.E. Hinton’s classic novel “The Outsiders” has been read by generations of American teens. The nearly 60-year-old story was turned into an iconic 1983 movie. Its narrative chops and cultural clout are undisputed. What might be more surprising is that its newest incarnation is a Broadway musical.

With previews all but selling out, part of the draw may be its star-studded creative and producing team, featuring award-winning playwright Adam Rapp, Tony Award winner Justin Levine, and Oscar winner Angelina Jolie.

But perhaps more important is the story’s relevance at a moment when people seem divided on everything. “The Outsiders” follows the constant conflict between two factions – the Greasers and the Socs – and succeeds in making the audience sympathize with both. It’s a hopeful reminder that those differences that seem so intractable might not be impossible to overcome after all.

Longtime fans of the story wondering about the prospect of Ponyboy and Sodapop bursting into song are definitely not alone. Mr. Rapp, who describes himself as “not a musical theater person – in fact, I openly dislike many musicals,” says he was surprised when he was asked to write the book for the show.

‘Stay gold, Ponyboy’ ... set to music? ‘The Outsiders’ comes to Broadway.

S.E. Hinton’s classic novel “The Outsiders” has been read by generations of American teens. The nearly 60-year-old story was turned into an iconic 1983 movie starring Matt Dillon, Patrick Swayze, and Ralph Macchio. Its narrative chops and cultural clout are undisputed. What might be more surprising is that its newest incarnation is a Broadway musical, which opened last Thursday.

With previews all but selling out, part of the draw may be its star-studded creative and producing team, featuring award-winning playwright Adam Rapp, Tony Award winner Justin Levine, and Oscar winner Angelina Jolie.

But perhaps more important is the story’s relevance at a moment when people seem divided on everything. The book has sold 15 million copies worldwide, and critics often credit it with inventing the young adult genre. Set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the late 1960s, “The Outsiders” follows Ponyboy Curtis (Brody Grant), an orphan eking out a life alongside his older brothers. It tracks the constant conflict between two factions – the Greasers and the Socs – and succeeds in making the audience sympathize with both. It’s a hopeful reminder that those differences that seem so intractable might not be impossible to overcome after all.

“It’s a good tale for right now,” says audience member Sue Miller after the March 30 preview, which garnered a standing ovation. “There are so many factions in our world right now, and I think we just really need to come together and try to get along.”

Longtime fans of the story wondering about the prospect of Ponyboy and Sodapop bursting into song are definitely not alone. Mr. Rapp, who describes himself as “not a musical theater person – in fact, I openly dislike many musicals,” says he was surprised when he was asked to write the book for the show. “When I go see musicals, it’s like, why are they singing?”

His interview with the Monitor staff writer Cameron Pugh has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you want to adapt “The Outsiders” into a musical? What drew you to the story?

It was kind of one of the early books that turned me into a reader. I would become a much more serious reader later. But I never forgot it.

What role do you think music plays in the story? Because I admit, when I saw that there was an adaptation, I was really excited. But I was surprised that it was a musical.

I think the main thing that I thought about was, these are wonderfully inarticulate kids. And I mean inarticulate in the way that, like, how kids today are sophisticated and how they emotionally process things. They’re sophisticated in how they discuss gender identity and sexuality and their feelings. These kids from this 1967 kind of era don’t have that ability. So what made sense to me was to honor that. But when they sang, it’s when they couldn’t articulate something. And that the singing part of it became a new voice, or a new form of expression, because they had no other recourse. And so the songwriters and I ... we always kept that as our North Star. Like, why? Why is he having to sing this? Why can’t he say it?

I thought a lot about the diversity of the cast. Particularly in that scene between Darry (Brent Comer) and Dally (Josh Boone) where they’re arguing. And Dally is sort of talking about how he thinks Darry thinks lesser of him. There’s sort of two ways to read that scene. And one of them is clearly racial. I was wondering if that’s something you were intentionally trying to bring into the story.

We didn’t want to author something that could only be done by a person with a certain skin type or a creed. ... We wanted it to be, “anyone can play the role.” So ... we’re not using the word “Black” or “African American” or anything like that. We’re using, “I see the way you look at me.” It could be like he’s looking at him because he’s lower, less than him. He’s poorer than he is. You know, we try to be somewhat generous with that so that if the play gets done in high schools and colleges and cities around the world, that anybody – white, Black, Asian – anybody could play the part. We were very sensitive to that.

But also it was important to Josh [Boone], while we’re in the moment, to like have him acknowledge the fact that he is a Black man playing that role with a white Darry and white Sodapop and a white Ponyboy. And that’s the truth. Like, we can’t deny that. And even, especially in Tulsa, where there’s so much history of racial violence and so much history of disruptions and those classes, of the haves and the have-nots. ... I feel like if we didn’t at least acknowledge it, and open it up a little bit, we’d kind of be lying, you know? And I’m glad that Josh, our actor, actually yearned for it.

I felt like a lot of the characters were explored almost more deeply than they were in the novel. In the novel, we’re getting Ponyboy’s perspective. We’re getting, “This is what I think Darry thinks.” And then in the show, we’re actually getting to see Darry sing about how he feels. And I’m just curious how you went about crafting those scenes and those character moments.

I felt really, really strongly that it’s an ensemble piece. I felt really strongly that Dally’s character was someone. ... And also the relationship between those three brothers, which is sort of the heartbeat of the story in some ways. All those people, to me, deserved real estate, narrative real estate, and deserved to be heard ... with songs and with good book scenes and good stuff to say.

I was also really struck by how much of the music in particular felt really joyful. I couldn’t help but smile at some parts of it, even though the story itself has a lot of darkness and a lot of tragedy.

Well, we knew how much sadness there is in the story. And as you said, sadness and tragedy. ... [The big three-minute rumble scene] is one of the most thrilling sequences I’ve ever seen in anything I’ve been involved with, you know? But I think because of that, like the counterpoint, you have to find the vitality and why these kids want to be around each other. You have to find the sort of notion of the chosen family, the joys of that, the goofing off, you know, the pleasures of life, even.

Points of Progress

Pulling up concrete and putting solar on renters’ roofs

In our progress roundup, a Portland, Oregon, group that digs up paved surfaces has inspired others to reap the climate benefits. And in sunny Australia, governments are encouraging landlords to install solar and help meet emissions goals.

Pulling up concrete and putting solar on renters’ roofs

More American students are learning Indigenous languages in public schools

During the 2022-2023 school year in Oklahoma, 3,314 students from elementary to high school took part in an Indigenous-language program, a threefold increase from two years prior.

Oklahoma schools, which enroll at least 158,000 Native American students, have taught tribal languages since 2014 – when the right to take Indigenous language for high school credit was made a state law. The Cherokee and Chocataw languages have the highest participation rates and are offered most often.

In June 2021, the Department of the Interior began acknowledging the United States’ role in 150 years of abuse of Native American children, who were punished for speaking tribal languages at federally funded boarding schools. For cultures around the world, the United Nations declared its decade of support for Indigenous languages in 2022, warning that all but a few hundred spoken languages out of thousands are endangered.

At Bartlesville High School in Oklahoma, just minutes from the Osage Nation Reservation, tribal-language classes are popular among both Native and non-Native students. “There definitely has been an uptick in the last couple of years of just students wanting to know more about their heritage, the culture [and] the culture that is around them,” said Principal Michael Harp.

Sources: Oklahoma Voice, Solutions Journalism Network, Oklahoma State Department of Education

In the United Kingdom, African visa-holders are filling gaps in elder care services

A 2021 report from the U.K. government’s Migration Advisory Committee attributed growing worker shortages in Britain’s care system to the pandemic and the impact of the United Kingdom leaving the European Union, which ended the free movement of workers. With the addition of care staff to the list of occupations for which the government provides work visas, Africans now make up the majority of foreigners working in Britain’s care sector.

Some 57,000 Africans, mostly from Nigeria and Ghana, entered the U.K. on a health and care visa in 2023 – up from 20,000 in 2022. Rights advocates say that U.K. jobs are well paid relative to those in many African countries, but not by European standards. They also point out a recent decision to prohibit care workers from bringing their families to the U.K. But for workers facing high cost of living and unemployment in Africa, home to the world’s youngest population, health care jobs in the U.K. may represent better opportunities. Source: Semafor

Farm by farm, smallholders in Africa have reforested an area nearly seven times the size of New York City’s Manhattan

Africa loses 3.9 million hectares (15,058 square miles) of rainforest and dry forest each year, owing largely to industrial and subsistence agriculture. Lacking long-term support or the proper species, many tree-planting programs fail. The nonprofit Trees for the Future may be an exception: Since 2015, its “forest garden” initiative has restored more than 100,000 acres of degraded farmland in nine countries.

On the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya, farmers meet to train and access tools and seed banks to replace their monocultures with forest gardens. A plot’s outer perimeter is lined with trees that act as a living fence, and in the center are vegetables and orchards bearing fruits such as mangoes and oranges. Each plot can have around 5,800 trees. Harvests provide a food source for families, and any excess can be sold for a profit. Though the benefits provided by old-growth forests accrue over centuries and cannot be fully replaced by planting new trees, Trees for the Future says its agroforestry approach breaks cycles of poverty and benefits the land. The organization has reached about 340,000 people and was named a World Restoration Flagship by the United Nations.

Sources: The Guardian, Chatham House

More rental homes are getting solar power

Australia has the highest per capita solar capacity installed in the world, with photovoltaic panels providing power for about one-third of homes. But these benefits have been largely out of reach for the one-third of Australians who are renters or live in government-subsidized housing, with only 4% of rental households powered by the sun.

As the homeowner market for solar becomes saturated and the federal government pushes to meet clean energy targets, it is encouraging landlords to invest in rooftop solar. Federal programs offer incentives for solar technology such as rebates on panels and water heaters. State governments offer their own subsidies, including payments for excess solar energy sold to the grid. An Australian innovation, SolShare is a software and hardware solution that allows as many as 10 apartments to share solar energy from one rooftop system.

Though some renters worry that solar installations could justify rent increases, many see them as a cost-effective way of lowering carbon emissions. Australia hopes to generate 82% of its electricity with clean energy by 2030.

Sources: Context, Clean Energy Council

Cities around the globe are depaving

Stripping away unnecessary concrete and asphalt replaces impermeable paving with plant life. This can lower the urban heat island effect, allowing rainwater to soak into the ground; reduce runoff and flooding; provide sanctuaries for wildlife; and boost well-being for residents.

In Portland, Oregon, the nonprofit Depave and its volunteers have removed six football fields’ worth of hard surfaces since 2008. Depave targets disenfranchised communities, where fewer shade trees and more paved surfaces make the environment hotter on average than in other neighborhoods.

In the Canadian province of Ontario, the nonprofit Green Venture has planted 2,850 native plants in Hamilton to help prevent runoff into nearby Lake Ontario, the source of the city’s drinking water. Leuven, Belgium, is depaving a suburb of 550 people, Spaanse Kroon. The city’s “tile taxi” will come to residents’ homes so they can dispose of asphalt or cobblestones they’ve removed. A suburb south of Paris recently depaved 11 acres of parking lots in a forested area.

Proponents cheer community-led and small-scale depaving, but they say municipal governments must devote significant resources to greening cities. “It starts with people pushing their government and starting these conversations on a small, local level,” said Depave’s Katherine Rose. “That’s how it takes hold.”

Sources: BBC, Reasons To Be Cheerful, Green Venture

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Listening while on the stump

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For many voters around the world, trusting an election result matters almost more than who wins. A December poll in the United States, for example, showed that a large majority of Republicans and Democrats worry about inaccurate or misleading election information in 2024.

Recent state-level reforms in the U.S. could help assuage those concerns. But the main need, argues Lawrence Lessig, a Harvard Law School professor and author of the new book “How To Steal a Presidential Election,” is that people talk to each other about “our division and how we need to get beyond it.”

The idea of listening is seldom measured in global surveys. Yet that solution keeps cropping up. In Mexico, the ruling party’s candidate for a presidential election, Claudia Sheinbaum, has instructed campaign workers to “go and listen!” In India, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi walked the length of that country to listen to voters ahead of elections starting this month. Humility, he said, requires deep sacrifice and perseverance.

Such qualities help instill trust in elections and improve civic participation. With dozens of national elections worldwide in 2024, more politicians may be catching on that listening may be as critical to winning as speaking.

Listening while on the stump

For many voters around the world, trusting an election result matters almost more than who wins. A December poll in the United States, for example, showed that a large majority of Republicans and Democrats worry about inaccurate or misleading election information in 2024.

Recent state-level reforms in the U.S. could help assuage those concerns. But the main need, argues Lawrence Lessig, a Harvard Law School professor and author of the new book “How To Steal a Presidential Election,” is for something softer. Dissolving distrust, he told NPR, requires that “people face to face, one to one, begin to just talk to each other and engage on – about – this reality of our division and how we need to get beyond it.”

The idea of listening to those with whom we disagree is seldom measured in global surveys on democracy. Yet that solution keeps cropping up around national elections this year. In Mexico, the ruling party’s candidate for the presidential election in June, Claudia Sheinbaum, has instructed her campaign workers to “go and listen!” In South Korea, President Yoon Suk Yeol said after his party lost an April 10 parliamentary election that he would listen to the public “with a more humble and flexible attitude.”

In a February survey of 24 countries, the Pew Research Center found that 74% of people say their elected officials don’t care what they think. That desire to be heard underscores a democracy’s requirement that citizens be treated with equality.

“If democracy is to function well, listening must also be supported and defended – especially at a moment when technological developments are making meaningful listening harder,” filmmaker Astra Taylor wrote in The New Yorker in 2020. “Deciding to listen to someone ... accords them a special kind of recognition and respect.”

Listening may not always change the course of elections, but it can replace enmity with empathy across social and political divides. In Britain, during the run-up to local elections on May 2 that may force a change in national leadership, two mayors from opposing parties have formed a close friendship over infrastructure plans. One praised the other as “decent and caring and compassionate.”

In India last year, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi walked the length of that country to listen to voters ahead of national elections starting this month. Humility, he said in a speech at the University of Cambridge, requires deep sacrifice and perseverance.

Such qualities help instill trust in elections and improve civic participation. With dozens of national elections worldwide in 2024, more politicians may be catching on that listening may be as critical to winning as speaking.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Healed of bipolar disorder

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Andy Crump

Recognizing that we are created by God to experience joy and peace, not instability, opens the door to healing.

Healed of bipolar disorder

My freshman year of college, I learned about some major world problems and was really disturbed by them. Feeling that I’d lost all hope, I suffered a mental breakdown and threatened to end my life.

Over the next few months, I transferred among several different hospitals and housing situations. I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and was prescribed various medications to treat the aggressive symptoms. Though I was sometimes required to take the pills, I resisted, because I didn’t like how they made me feel, and I only ended up taking them for a short period of time before stopping altogether.

I grew up attending Christian Science Sunday School, so I turned to Christian Science for help at various times during this period. On the several occasions when I called a Christian Science practitioner, they were very helpful. But I wasn’t always receptive.

Then I moved back home, and went back to my local Christian Science Sunday School. My teacher was shocked by the way I was acting – so unlike myself. He knew me well, and he refused to believe that the Andy he remembered could exhibit this disturbing behavior.

I’m convinced that his commitment to seeing me as I really am – seeing my true, spiritual nature and character – accelerated my progress. By the next Sunday, I was calmer and more receptive to spiritual ideas. This was a turning point.

One idea that kept coming to thought during this time was something Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, said: “If you wish to be happy, argue with yourself on the side of happiness; take the side you wish to carry, and be careful not to talk on both sides, or to argue stronger for sorrow than for joy” (“Christian Healing,” p. 10).

Sadness seemed so appealing at the time because it allowed me to be a victim and blame the world for my problems. I realized, though, that I did want to be happy, and that I needed to actively argue for – spiritually stand up for – my own happiness.

God, who is all good, made each of us in His image (see Genesis 1:27). Joy isn’t a temporary emotion; it’s a quality that permanently belongs to us as God’s spiritual reflection.

The more I thought about this, the more light I could see through the darkness. I realized that I wanted to go back to school, be with my friends, and finish my degree – and I knew that was possible.

The improvement didn’t happen overnight, but by the end of the summer I was completely free from the symptoms, and I have been ever since – over a decade now. I was admitted back to my college and was even able to graduate with my class.

“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mrs. Eddy explains, “It is ignorance and false belief, based on a material sense of things, which hide spiritual beauty and goodness. Understanding this, Paul said: ‘Neither death, nor life, ... nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God.’ This is the doctrine of Christian Science: that divine Love cannot be deprived of its manifestation, or object; that joy cannot be turned into sorrow, for sorrow is not the master of joy; that good can never produce evil; that matter can never produce mind nor life result in death” (p. 304).

Sorrow is not more powerful than joy, and nothing can separate anyone from God’s love. If we find ourselves feeling sad or overwhelmed by events in the world, we can remember that God is permanent and infinite good. So the spiritual reality of things – the goodness of God’s creation – is always present. We can see it by turning to God in prayer.

Adapted from an article published in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, Jan. 16, 2024.

Viewfinder

A torch begins its Olympian journey

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at schools in the United States seeing an influx of migrant students. How are teachers looking at the challenges and the opportunities?