- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- How to stop ‘forever chemicals’ from lasting, well, forever

- Today’s news briefs

- How US support for Ukraine and Israel grew shakier as key vote nears

- Can Israel embrace America’s vision of a ‘new Middle East’?

- Once-radical ideology could propel Modi to third term in India

- The Monitor’s 10 best new books of April

- Amid gritty Chicago reality, two friends embrace childhood

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Addressing root issues

Several stories today confront the difficulty of addressing root causes in very different circumstances.

Take PFAS – “forever chemicals’’ ending up in water supplies. The Environmental Protection Agency just issued new standards for drinking water. But tackling the problem at its source – before the water hits taps at home – is complicated amid scattershot state efforts. Meanwhile, on Capitol Hill, as the House debates aid to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan, our correspondent is finding that the conversation often skates over fundamental issues that would be much harder to take on.

And don’t miss our review of the film “We Grown Now.” Peter Rainer shares how his willingness, years ago, to reconsider an assumption he had made had a powerful impact on how he watched this film.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

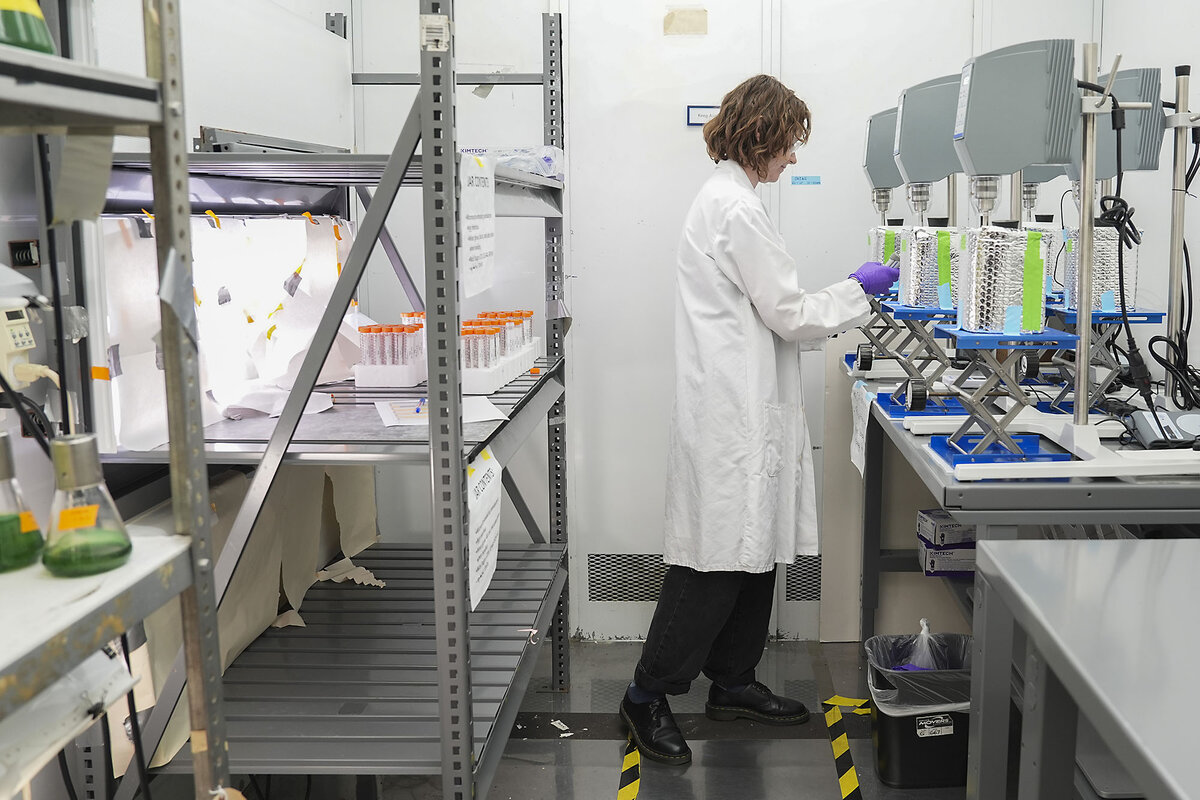

How to stop ‘forever chemicals’ from lasting, well, forever

The EPA recently strengthened regulations on so-called PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” in drinking water. A next step, some experts say, is reducing the creation of these chemicals in the first place.

The Environmental Protection Agency last week released stringent new standards for “forever chemicals” in U.S. drinking water.

Environmental advocates hope this will be the first step of a wider effort to study, remediate, and regulate the chemicals known as PFAS – shorthand for synthetic perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances – which are used in consumer goods from carpets to cosmetics, but do not break down in nature. They regularly end up in drinking water, food, and ultimately humans.

“While I welcome the new enforceable drinking water standards, we really need to look upstream,” says Judith Enck, president of the advocacy group Beyond Plastics. “How do we reduce the use of PFAS in general?”

Across the United States, there has been a wave of grassroots public health campaigns and state policies designed to reduce the risk of these chemicals, which have been linked to a slew of health impacts.

Currently, around a dozen states have some sort of regulation of PFAS. But a state-by-state approach is scattered, advocates say. They urge greater federal action.

Chemical companies object. The industry has already voluntarily regulated and monitored those PFAS shown to be dangerous, according to the American Chemistry Council.

How to stop ‘forever chemicals’ from lasting, well, forever

Long before the Environmental Protection Agency announced new rules this month about “forever chemicals” in drinking water, officials in the state of Vermont knew there was a problem.

Regulators there began looking into PFAS – shorthand for synthetic perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances – after residents near the town of Bennington complained that their water had been contaminated by a nearby factory, which for decades had produced fiberglass-coated fabrics. That was in 2016. Vermont officials eventually uncovered a public health crisis – which resulted in strict statewide PFAS regulations.

Recently, advocates say, this wake-up has been happening on a broader scale. Across the United States, there has been a wave of grassroots public health campaigns, state policies, and even burgeoning federal efforts designed to reduce the risk of these forever chemicals, which have been linked to a slew of health impacts.

Many advocates hope the new nationwide rules released by the EPA last week, which create stringent new standards for PFAS in drinking water, will be only the first step of a wider effort to study, remediate, and regulate the chemicals.

“While I welcome the new enforceable drinking water standards, we really need to look upstream,” says Judith Enck, president of the advocacy group Beyond Plastics. “How do we reduce the use of PFAS in general?”

PFAS are used in consumer goods from carpets to rain jackets, from cookware to cosmetics. They are resistant to heat, and repel stains, oil, and water, but they do not break down in nature. And they regularly end up in drinking water, soil, food, and ultimately humans.

The term “PFAS” refers to thousands of different substances, all containing a certain chemical bond; the new EPA water standards apply to six. While advocates praised the move, some water utilities criticized what it said would be a costly mandate – one study by an industry association estimated the new rules would cost upward of $3.8 billion nationally.

“The vast majority of these treatment costs will be borne by communities and ratepayers, who are also facing increased costs to address other needs, such as replacing lead service lines, upgrading cybersecurity, replacing aging infrastructure and assuring sustainable water supplies,” the American Water Works Association said in a statement.

A “wake-up call”

Others agree with the idea that it is a lot harder to try to clean up PFAS than to keep them out of the environment in the first place.

“The thing we realized was that trying to treat every wastewater treatment plant and every drinking water facility – it was going to be impossible,” says Matt Chapman, director of the waste management and prevention division at Vermont’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

Vermont’s experience with responding to PFAS may prove instructive as more consumers and politicians take note of forever chemicals.

Investigators in 2016 discovered Bennington’s groundwater had indeed been tainted with unsafe levels of perfluorooctanoic acid, a particularly dangerous variety of these industry-produced chemicals.

After the discovery in Bennington, the Department of Environmental Conservation scrambled to check other locations in the state, from wastewater treatment facilities to landfills to areas where another type of PFAS was used in firefighting foam. Although the levels varied, the contamination was across the state.

“That was the wake-up call for Vermont,” says Marcie Gallagher, an advocate focusing on environmental health with the Vermont Public Interest Research Group.

Vermont created its own drinking water standards in 2019, but also added prohibitions on PFAS being added to categories of consumer goods, such as carpets, clothing, cookware, and ski wax. (Regulators found high levels of PFAS contamination around cross-country ski centers, and then realized that the wax used for cross-country racing was high in the substances.)

Other states have banned PFAS in products such as artificial turf and cookware. In 2021, neighboring Maine went even further and passed legislation that would ban by 2030 all nonessential uses of PFAS in products. (That law was amended this year to provide exceptions.) Minnesota soon followed suit.

“It’s a way to limit consumer exposure to it,” says Sarah Woodbury, vice president of programs and policy for Defend Our Health, a Maine-based group that works on environmental health issues. “We’re phasing it out in a whole bunch of consumer products that people are exposed to on a daily basis.”

Currently, about a dozen states have some sort of regulation of PFAS, while a number of companies have pledged to phase out PFAS use in their products. In the Northeast, states have joined forces to create a regional response.

But a state-by-state approach is scattered, advocates say. They say the federal government should create rules around PFAS – including transparency requirements that let consumers know whether the things they buy and eat contain the chemicals.

“This really should be regulated at the national level,” says Ms. Enck. “Absent federal leadership, states try to step in and fill the vacuum. All the states are doing it differently.”

Regulation debate

Chemical companies object. The industry has already voluntarily regulated and monitored those PFAS shown to be dangerous, according to the American Chemistry Council. Grouping together the thousands of different substances that fall under the PFAS label is a mistake and threatens innovation, the council says.

“PFAS are a diverse universe of chemistries that are essential to modern life,” the group says on its website. “PFAS chemistries are also key to the resiliency of our nation’s critical supply chains, including semiconductors, cable coatings, building materials, fuel cell and lithium-ion battery technologies, and much more.”

Besides, there’s no proof that all PFAS are dangerous, the group says.

That’s true, advocates acknowledge. But they say there’s also no proof that all PFAS are safe – and a lot to indicate that they’re not. Chemical companies have been the target of thousands of PFAS-related lawsuits in recent years, including class action cases and those brought by state attorneys general. At the same time, research on the connections between PFAS and various health concerns is evolving.

“These are toxic forever chemicals that share carbon fluorine bonds,” says Katie Pelch, a scientist in environmental health at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Because all the chemicals in that class share that chemical group, we need to treat them as class. The one-at-a-time chemical regulation that we typically see just will not make a dent fast enough to actually protect public health.”

In the U.S., regulation tends to come after there is evidence of health risks. But that “innocent until proven guilty” approach, advocates say, shouldn’t be the case for this class of chemicals, with some of them already shown to be harmful.

“PFAS should be banned,” says Ms. Enck. “We should have no PFAS in packaging. We should have no PFAS in consumer products. Companies use it because it makes things slippery and water-resistant. But we have to turn off the tap.”

Today’s news briefs

• Antisemitism hearing: Lawmakers on a U.S. congressional committee accuse Columbia University President Nemat Shafik of failing to protect Jewish students on campus, echoing accusations leveled against other elite university leaders at a December hearing.

• Maine gun legislation: The state adopts a number of gun and mental health proposals nearly six months after an Oct. 25 shooting claimed 18 lives.

• Larry Nassar case settlements: The U.S. Justice Department has agreed to pay approximately $100 million to settle claims with about 100 people who were sexually assaulted by sports doctor Larry Nassar.

• Mayorkas impeachment update: The Senate dismisses all impeachment charges against Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, ending the House Republican push to remove the Cabinet secretary over his handling of the U.S.-Mexico border.

How US support for Ukraine and Israel grew shakier as key vote nears

Lawmakers face increasing political pressure from within their parties over aid to Israel and Ukraine as the presidential election approaches. Some say politics have obscured serious security debates.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

A bill to help Ukraine and Israel, along with Taiwan, has passed the U.S. Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support. But similar efforts have foundered in the House of Representatives, where the battle lines are drawn not only between parties but also within parties.

What happened?

Rep. Jared Golden, a Democrat from Maine, says he’s seen a “rapid change” in the Democratic position on Israel, and a Republican about-face on Russian intervention in Ukraine.

For decades there was a strong bipartisan core that supported defending U.S. interests and allies abroad, including with military aid. But as long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan ended without clear victories, that political support started to erode. Meanwhile, Democratic politics have gravitated more toward championing downtrodden minorities – including Palestinians.

House Speaker Mike Johnson has broken the foreign aid package into several parts, aiming for votes on Saturday, but it’s unclear whether they will succeed.

Often lost amid the politics is a serious debate over America’s interests abroad, and what the costs of upholding them – or not – would be.

“The political debate here is lacking in real-world experience, and therefore lacks consistency,” says Mr. Golden, a former Marine.

How US support for Ukraine and Israel grew shakier as key vote nears

Rep. Jared Golden knows firsthand the toll of war. The Maine Democrat fought as a Marine infantryman in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Now he’s in the midst of a different battle, a political one. Congress is preparing to vote on sending U.S. aid to allies facing America’s three most powerful adversaries: Russia, Iran, and China.

Like many lawmakers, Representative Golden is getting pressure from constituents on how he should vote. They call his office upset that he’s not doing more to advance aid to Ukraine, which is locked in a stalemate with the Russian military and running out of ammunition. Some of the same people are also angry that he is supporting Israel as it retaliates against an Oct. 7 attack by Iranian proxy Hamas, and the Gaza death toll climbs to nearly 35,000.

A Senate bill to help both allies, along with Taiwan, passed the Senate with overwhelming bipartisan support. But similar efforts have foundered in the House, where the battle lines are drawn not only between parties but also within them. Speaker Mike Johnson has broken the foreign aid package into several parts in a bid to get them through with as little damage to his speakership and the razor-thin Republican majority as possible. The votes are expected Saturday, but it’s unclear whether they will succeed.

Often lost amid the politics is a serious bipartisan policy debate over what are America’s real interests abroad, and what the costs of upholding them – or not – would be.

“War is terrible, and sometimes necessary. So what I think is difficult is watching our politics lose sight of that,” Mr. Golden says. “The political debate here is lacking in real-world experience, and therefore lacks consistency.”

“It’s all gotten way too partisan” – and too wrapped up in presidential campaign politics, adds Mr. Golden, noting a “rapid change” in Democrats’ position on Israel and a Republican about-face on Ukraine. Ten years ago, GOP lawmakers lambasted the Obama administration for a weak response to Moscow’s annexation of Crimea from Ukraine.

Though there have always been outliers on the left and right on foreign policy, for decades there was a strong bipartisan core that supported defending U.S. interests and allies abroad with robust aid, including military aid. But as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wore on, and eventually ended – without clear victories and at a cost of thousands of American lives and trillions of dollars – that political support started to erode.

Democratic politics, driven in part by the rapid rise of the racial justice movement in 2020, started gravitating more toward championing downtrodden minorities – including Palestinians. And Republicans, animated by former President Donald Trump’s “America First” populism, have grown wary of intervening abroad.

Israel remains an exception on the right. Meanwhile, persistent concerns on the left that Mr. Trump is sympathetic to Russian President Vladimir Putin have perhaps added to the Democratic enthusiasm for rallying around Ukraine.

Republican divide over Ukraine

GOP Rep. Michael McCaul, who chairs the House Foreign Affairs Committee, says he has to explain the national security interest to colleagues, some of whom were born after the Cold War era. Their war memories are dominated by pointless stalemates in the Middle East more than victory in Europe or decades spent defending that victory against an expansionist Soviet Union.

“We can stop Putin here by letting Ukraine fight their own war” – with the help of U.S. weapons, says Representative McCaul, whose father fought in the D-Day invasion of 1944 to repel the Nazi forces, something that he says wouldn’t have been necessary if Hitler had been stopped earlier. Aiding Ukraine now would mean “saving a lot of blood and treasure down the road.”

But other Republicans don’t see a path to victory in Ukraine. They – and their constituents – don’t want to send any more “blank checks” to fund the effort, especially given record U.S. debt and concerns about securing America’s own borders amid a migrant influx.

“I don’t think we ought to be borrowing money we don’t have to send it to Ukraine with no plan and no limit to U.S. involvement,” says Rep. Bob Good, head of the right-wing Freedom Caucus that has been a thorn in the side of Speaker Johnson’s efforts to pass a foreign aid package over the past six months. He professed himself unmoved by a Trump-inspired tweak to make some of the Ukraine aid a loan, expressing doubt it would ever be paid back.

Even GOP Rep. Victoria Spartz, a Ukrainian American congresswoman from Indiana who understands better than most what is at stake, says she has reservations about sending Ukraine aid. She’s frustrated with the Biden administration’s lack of accountability for funds already sent and the inefficacy of his strategy so far, including the slow-walking of aid early on, which she says emboldened Mr. Putin and gave him time to regroup. “You do not deal with Putin ‘as long as it takes,’” she says, quoting the president’s 2022 vow. “You deal with him as fast as you can.”

Former U.S. Ambassador to NATO Kurt Volker, who served under the George W. Bush administration, points out that when Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, that GOP administration sprang into action – in concert with its European allies. But unlike Mr. Bush, President Joe Biden has been reticent to use force, calling instead for de-escalation in hopes of preventing wider conflagration between both Israel and Iran, and Ukraine and Russia.

“In my view, the problem with that is it produces the opposite result,” says Mr. Volker. “It basically gives an assurance to the aggressors that nothing is going to happen to them, so they keep going.”

Democratic shift on Israel

On Israel, the GOP has been in lockstep on aid, but Democrats have yo-yoed. Many rallied around it after the Oct. 7 attack, as well as after last weekend’s barrage of missiles and drones from Iran – the first direct Iranian attack on Israeli soil. But overall, wariness about U.S. support for Israel has grown amid a cloud of concerns. The Gaza death toll has mounted. The International Court of Justice has called on Israel to prevent genocide in Gaza and to enable urgently needed humanitarian assistance. And Mr. Biden has come under pressure from the progressive left, young voters, and Arab Americans in Michigan – a key swing state.

Hadar Susskind, president of Peace Now, says when he and his organization called three years ago for conditioning aid to Israel, not a single member of Congress publicly supported that position. Now, the idea has entered the mainstream.

“This isn’t ‘the Squad’ or a handful of far-left members,” he says, citing recent supportive statements by House Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. “We’re talking about the establishment of the establishment Democrats saying what we’ve been saying for a long time – U.S. aid to Israel is important, but it needs to align with American values.”

Majority Leader Schumer gave a bracing speech last month that was widely interpreted as not only warning Israel but also addressing progressives’ frustration with Mr. Biden in an election year. He acknowledged the difficulty of fighting a foe that hides behind civilians and is still holding hostage 130 individuals, including some of his New York constituents. But, adding that the United States has an obligation to help its ally toward lasting peace and security, he also called on Israel to address the “humanitarian catastrophe” in Gaza and lay the groundwork for a two-state solution.

“We should not be forced into a position of unequivocally supporting the actions of an Israeli government that includes bigots who reject the idea of a Palestinian state.”

Rep. Ilhan Omar, one of the few Muslim members of Congress, a longtime critic of Israel, and one of the four progressive women originally dubbed the Squad, says there’s a shift in Congress toward recognizing the humanity of Palestinians but adds that there’s “still a long way” to go for people to see them as being worthy of dignity and safety.

As for the president, she acknowledges that there’s been a shift in rhetoric. “But I think people want to see action that follows that.”

Patterns

Can Israel embrace America’s vision of a ‘new Middle East’?

When Arab neighbors intercepted Iranian missiles aimed at Israel, they made Washington’s vision of a “new Middle East” a reality. Will Israel sign up for that new future?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

It’s decision time for Israel. And the question it faces goes beyond the immediate challenge of how to hit back against Iran’s barrage of missiles last weekend.

It is a choice about Israel’s future relations with its Mideast neighbors and the wider world, between permanent Israeli rule over the Palestinians and the lure of a historic, U.S.-mediated peace with Saudi Arabia.

Israel’s extraordinary success in fending off Iran’s unprecedented attack relied on a seamlessly coordinated response that involved the United States, Britain, and France, as well as Arab states including Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia.

It was a dramatic demonstration of what Washington’s much-touted “new Middle East” could mean in practice. As they ponder their response to Iran’s attack, Israel’s leaders now have real-world evidence of the benefit of coordination with Arab states.

The price to Israel of a peace deal has gone up with the war in Gaza. Arab states, and Washington, are now insisting on a firm commitment to a Palestinian state. But Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government depends on extreme right-wing coalition partners who would rather annex the Palestinian territories than give Palestinians statehood.

The prospects of reviving the idea of a peace deal seem very slim. Still, on both sides, incentives remain.

Can Israel embrace America’s vision of a ‘new Middle East’?

It’s decision time for Israel. And the question it faces goes beyond the immediate challenge of how to hit back against Iran’s barrage of missiles and drones last weekend.

It is a choice about Israel’s future relations with its Mideast neighbors and the wider world.

That decision – between permanent Israeli rule over the Palestinians of the occupied West Bank and the lure of a historic, U.S.-mediated peace with Saudi Arabia – is one Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was wrestling with through much of last year.

Until Oct. 7.

That was when Hamas breached Israel’s southern border to attack, abduct, and kill more than a thousand people, and Israel responded with an invasion that has left tens of thousands of Gaza Palestinians dead and hundreds of thousands homeless and hungry.

Last Saturday’s missile strike, however, put that choice back on the table, and underscored what’s at stake.

That’s because Israel’s extraordinary success in fending off Iran’s unprecedented attack was not merely a testament to its own sophisticated air defenses.

It relied on a seamlessly coordinated response that involved the United States, Britain, and France, as well as Arab states including Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia.

It was a dramatic demonstration of what Washington’s much-touted “new Middle East” could mean in practice.

The Arab leaders’ participation was especially significant, given growing grassroots hostility to Israel inside their own countries amid the humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

So alongside the web of other issues Israel’s leaders are weighing as they ponder their response to Iran’s attack, they now have real-world evidence of the benefit of coordination with Arab states. They know, too, that they could not necessarily count on similar help if Israel’s retaliation were to result in a second onslaught of missiles from Iran.

Yet even if Israel does find a way to respond without further escalating regional tensions, it still has to address the deeper, longer-term question: whether to buy into the U.S. vision of a formal deal with the leading power in the Arab and Muslim world, Saudi Arabia.

That question has become both more pressing and more difficult since Oct. 7.

It is more pressing because it goes to the core of a critical issue Israel will need to tackle once its troops have ended their operations against Hamas: how to rebuild Gaza and put in place political and security arrangements to safeguard the territory’s civilian population and Israel’s as well.

The Americans, and their international allies, see a key role here for the Arab states in the Gulf: helping fund reconstruction, encouraging a root-and-branch reform of the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority – readying it to take control – and providing a transitional security force in Gaza.

But the “new Middle East” framework has also become more difficult since Oct. 7.

The nature of the main political concession that Israel would have to make – a change in its policy toward the Palestinians – has gotten a lot harder for Mr. Netanyahu to swallow.

U.S. President Joe Biden met Mr. Netanyahu in late September 2023, two weeks before the Hamas attack, to outline his vision of a route to Middle East peace. It involved curbing Jewish settlements in the West Bank, expanding the areas under Palestinian control, and at least leaving open the door for an eventual two-state peace.

But that was six months ago.

Today, with international alarm deepening over the civilian suffering in Gaza, the Saudis, other Gulf Arab states, and Washington are convinced that a more explicit pathway toward Palestinian statehood is now essential. The Saudis, in particular, are unlikely to feel able to normalize ties with Israel without this.

But at home, Mr. Netanyahu would find such a commitment even costlier than ever.

The pair of small, far-right parties on which Mr. Netanyahu’s governing coalition depends have redoubled their drive to expand Israeli settlements and ultimately annex the West Bank. They want Israel to retake control of Gaza as well, once the fighting is over.

So at least for now, prospects of reviving the idea of a peace deal seem very slim.

Still, incentives remain on both sides.

The Saudis share Israel’s concerns about the Iranians and their regional proxy armies. Last weekend’s coordinated response to the Iranian attack will also have brought home the potential benefits to Saudi Arabia.

In 2019, a missile attack by Iranian-armed Houthis in Yemen caused major damage to a key Saudi oil installation. The kind of intelligence sharing and joint action seen last weekend could have thwarted it.

A more formal U.S. security guarantee and access to top-of-the-line American warplanes are also major attractions for the Saudis in a deal with Israel.

For Mr. Netanyahu, such an arrangement could not only ensure Arab support and participation in postwar Gaza. It could also strengthen his hand in seeking a demilitarized buffer zone in southern Lebanon to reduce the threat from Iranian-armed Hezbollah forces there.

And there’s a political incentive as well: At a time when most Israelis hold him responsible for allowing Oct. 7 to happen, he could claim credit for a long-sought Saudi peace deal, finally opening the way to Israel’s acceptance in the wider Arab and Muslim world.

Once-radical ideology could propel Modi to third term in India

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to easily win a third term during India’s general election. The engine of his popularity? A long-standing ideology that seeks to transform India from a secular nation into a Hindu one.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Armed with his highest-ever approval ratings, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems all but guaranteed to win a third term in elections that begin Friday.

Among supporters, he’s attained a godlike status in large part by leveraging Hindutva, a once-fringe political ideology that equates “Indianness” with “Hinduness.” First coined in 1922, Hindutva is based on a view of the subcontinent’s history as a Hindu land under constant invasion – by Islamic forces, Christian missionaries, and British imperialists. Indian independence, through the Hindutva lens, meant liberating Hindus from all these outside forces.

Historians criticize this interpretation as erasing centuries of religious coexistence and portraying Hindu culture as monolithic. The ideology was rejected by India’s founding fathers, including Mahatma Gandhi, who chose to establish India as a secular democracy that embraced religious pluralism.

But in recent decades, Hindutva groups have managed to enter the political mainstream.

Helmed by Mr. Modi, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party has swept recent elections, and policies implemented by the Modi administration have advanced the Hindutva goal of establishing cultural hegemony and resulted in the persecution of India’s large Muslim minority.

According to Professor Apoorvanand, from the University of Delhi’s Hindi Department, India “has become, in all practical senses, a Hindu-first state.”

Once-radical ideology could propel Modi to third term in India

Ramesh Singh had been waiting for this day for five years. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made it a tradition to kick off general election campaigns in Mr. Singh’s city, and this year was no different. So the sugarcane farmer joined the adoring throngs, who are all but guaranteed to deliver Mr. Modi a resounding third-term victory in elections that begin Friday.

“Modi is not just a leader for us; he is like our god. He is the savior of Hindus,” says Mr. Singh, who was at the front of the crowd, waving the flag of Mr. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), during the campaign rally last month. “I will make sure everyone in my family and relatives votes for Modi’s party.”

As the world’s largest election gets underway, Mr. Modi’s brand of nationalist politics is on full display, signaling even more division ahead for India’s diverse population. The prime minister reached near deity status among his supporters in large part by leveraging Hindutva, a once-fringe political ideology that equates “Indianness” with “Hinduness.” It thrives on the belief – credible or not – that Hindu culture is under threat, and aims to establish Hindu hegemony. Policies implemented over the past decade have resulted in the persecution of India’s large Muslim minority, and pushed the country, founded on democratic and secular values, on the path to becoming a Hindu nation.

Some experts say India’s already there.

“There are laws that the Modi government has made that are clearly discriminatory and anti-Muslim, and state policies for the allocation of resources are also [biased] against Muslims and Christians,” says Apoorvanand, a political commentator and professor from the University of Delhi’s Hindi Department, who, like many in India, uses only one name. “It has become, in all practical senses, a Hindu-first state.”

An ideology that predates modern India

The Hindutva ideology was first described by Indian political activist Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in 1922, while in prison for opposing British colonial rule.

It’s based on a view of the subcontinent’s history not as a crossroads of different religions and cultures, but as a Hindu land under constant invasion – by Islamic forces, Christian missionaries, and British imperialists. Indian independence, through the Hindutva lens, meant liberating Hindus from all these outside forces.

Many historians say this history is flawed, erasing centuries of peaceful coexistence between different religions and portraying Hindu culture as monolithic.

“The basic element in their ideology is that only those whose fatherland and Punya Bhoomi [land of worship] are in India are Indians, which means Christians and Muslims are foreigners,” says Aditya Mukherjee, professor of contemporary Indian history at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “This is what false consciousness is. You create a memory, and you create a consciousness that does not exist.”

Savarkar’s teachings inspired the creation of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu nationalist volunteer organization. Its members admired European fascism and were early supporters of the “two-nation theory,” which advocated for partitioning post-colonial British India into a state for Muslims (Pakistan) and a state for Hindus (Hindustan).

But India’s founders, including Mahatma Gandhi, “thought that this was an absurd and pro-colonial idea,” says Professor Mukherjee. The movement to create Pakistan succeeded, but in India, leaders instead established a secular democracy that sought to embrace religious pluralism, and Hindutva politicians were pushed to the fringes.

“In the first election [held 1951-1952], they got 6% of the votes,” says Professor Mukherjee. “Ninety-four percent of the Indian people said we don’t want … a mirror image of Muslim Pakistan. We want a secular India.”

In the following decades, India’s dominant political party, the centrist Indian National Congress, worked to limit the RSS’s influence. When a Hindutva activist and RSS member assassinated Gandhi during a multifaith prayer meeting in 1948, the government imposed a year-long ban against the group – one of several during the country’s early history.

But since then, Hindutva leaders have also been working – often quietly – to rebuild their power. RSS members have opened more than 20,000 schools that teach a Hindu nationalist version of Indian history. The BJP, founded in 1980 as the RSS’s political arm, brought Hindutva ideas back into mainstream politics by allying with various parties trying to dislodge Congress.

Helmed by Mr. Modi, who served as an RSS volunteer throughout his youth, the BJP has completed this mission. Last elections, the party swept votes, winning 303 out of 543 parliamentary seats, and Congress remains on the back-foot today. Over the past decade, the Modi administration has rallied Hindu nationalists and advanced the Hindutva agenda nationwide.

This includes revoking Article 370, which granted the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir special autonomy; advocating for a uniform civil code, which would bar people from using their own religious laws to govern issues such as marriage and inheritance, as is currently allowed in India; and criminalizing the conversion of Hindus into other faiths, particularly Islam and Christianity, despite limited evidence of wide-scale, forced conversions. Human rights groups have also sounded alarms over the introduction of religion-based citizenship laws.

Hub of Hindutva

Uttar Pradesh – the country’s most populous state, and typically a bellwether for national elections – offers a glimpse into what a Hindu-first India would look like.

Here, the last 10 years have been rife with incidents of Hindu majoritarianism. Authorities have bulldozed Muslim homes and businesses, Islamic religious schools have been banned, frenzied mobs have killed Muslims suspected of eating beef, and interfaith couples have been attacked by right-wing groups. All this has the tacit or direct support of the government, headed by Hindu clerk-turned-politician Yogi Adityanath.

Earlier this year, Mr. Modi traveled to Ayodhya, located across the state from Meerut, to inaugurate the controversial Ram temple, a major Hindu nationalist rallying point. The massive temple is built on the site of a centuries-old mosque that was demolished in 1992 by a violent Hindu mob.

“People thought it would be impossible, but Ram temple was built there,” the prime minister told tens of thousands of supporters during his recent rally in Meerut. At no point during his 45-minute speech did the prime minister reassure or acknowledge religious minorities, despite 36% of Meerut’s population being Muslim.

Just weeks later, 200 Muslims were booked by police officers for offering Eid prayers on the road.

“Modi can use the entire government machinery for building Hindu temples, but they cannot tolerate Muslims praying on the day of their most important festival,” says Abdul Samad, a resident of Meerut. “It has been clear in the last ten years that the BJP wants Muslims to live as second-class citizens.”

Anwari Begum, whose husband was one of the 17 people killed during the destruction of Ayodhya mosque, agrees. “The mission of Modi’s party is to punish Muslims,” she says. “They are humiliating us every day.”

It’s a sentiment shared far beyond Uttar Pradesh. Across India, but especially in states with BJP leadership, observers say religious divisions are growing as hardline Hindutva thought goes mainstream.

Vikas Verma, a member of the RSS-affiliated vigilante group Bajrang Dal in neighboring Uttarakhand, helped spearhead a campaign last May to drive out Muslim shopkeepers over an alleged case of “love jihad” – a common conspiracy theory accusing Muslim men of luring Hindu women into marriage in order to forcibly convert them to Islam.

“We believe that Muslims are deliberately increasing their population, and they want to take over the land of Hindus,” he says, arguing that Hindus must not allow Muslims in India to pray publicly or serve Halal meat.

“They should live like Hindus do,” he says.

Books

The Monitor’s 10 best new books of April

Tales of reinvention and courage are threaded through our reviewers’ picks for the 10 best books of April – including a globe-trotting adventure story and a history of the animal rights movement.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Staff

“’Tis the good reader that makes the good book; ... in every book he finds passages which seem confidences or asides hidden from all else and unmistakably meant for his ear,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson in “Society and Solitude.”

What was true in 1870 when Emerson penned those lines remains true today. Adventurous readers will find much that speaks to them among the Monitor’s 10 best books of April.

Our reviewers’ picks this month include a futuristic novel that, amid its harrowing adventure, unfolds moments of resilience and kinship. And an ambitious debut novel follows a Parisian girl in the 1880s who must keep traveling or risks death.

Among the nonfiction selections is Doris Kearns Goodwin’s “An Unfinished Love Story,” a tribute to her husband, the late Dick Goodwin, who was a speechwriter and adviser to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. She blends history with memoir in her account of the 1960s – a pivotal era that included the Civil Rights Movement.

The Monitor’s 10 best new books of April

Real Americans, by Rachel Khong

Rachel Khong’s dazzling second novel probes issues of class, race, genetics, and identity. Her gripping narrative encompasses several love stories, political repression, the promise and limits of science, and the reverberations of dark secrets through two intertwined Chinese American families.

I Cheerfully Refuse, by Leif Enger

In a rickety sailboat on storm-tossed Lake Superior, a grieving musician flees a powerful enemy. Set in a speculative future in which the supply chain has failed and a lethal drug holds sway, Leif Enger’s latest novel steers a harrowing course through a broken world. Yes, it’s grim, but in Enger’s capable hands it’s also a riveting story of resilience and kinship.

Clear, by Carys Davies

Weather whips and worlds collide as a Scottish minister recovers from an accident under the care of the solitary islander he’s been dispatched to uproot. Despite the harsh Shetland Islands landscape and the punishing realities of an 1840s Scotland undergoing transformation, gentleness – and even joy – seep through the murk of this evocative tale.

A Short Walk Through a Wide World, by Douglas Westerbeke

In Douglas Westerbeke’s imaginative debut, French preteen Aubrey literally has to keep moving: If she stays in one spot for more than several days, her body revolts. (Warning: There will be blood.) A life of globe-trotting adventure ensues, but also days marked by detours as she hunts for clues to her mysterious malady. The novel is a fleet-footed winner.

The Murder of Mr. Ma, by SJ Rozan and John Shen Yen Nee

Judge Dee, a lithe martial arts master struggling with PTSD after World War I, teams up with earnest scholar and budding novelist Lao She to investigate a string of murders around London in 1924. Amid the whirl of crescent kicks, rooftop chases, and snappy dialogue, characters confront addiction, defy prejudice, and deliver justice. It’s a cinematic ride.

The Paris Novel, by Ruth Reichl

Following the death of her difficult mother, Stella, a 20-something New Yorker, flies to Paris to find herself. From this familiar premise blooms a moving portrait of self-discovery and creativity complete with delectable dishes, haute couture, a painter from the past, and a famous bookstore sheltering eccentrics and poets. It’s a treat from a true gastronome.

An Unfinished Love Story, by Doris Kearns Goodwin

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin was married for more than 40 years to Dick Goodwin, a speechwriter and adviser to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. In the years before Mr. Goodwin’s death, the couple went through hundreds of boxes of his memorabilia from those administrations. This affecting book, blending history, memoir, and biography, is a personal account of a pivotal era.

Our Kindred Creatures, by Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy

This fascinating history traces the shift in American attitudes toward animals in the decades after the Civil War. The authors describe the era’s widespread mistreatment of animals and profile the activists who convinced their fellow citizens that the prevention of animal suffering was a just cause.

Alien Earths, by Lisa Kaltenegger

Astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger, who directs the Carl Sagan Institute To Search for Life in the Cosmos, documents the quest for extraterrestrial life with winning enthusiasm. Explaining how she and her colleagues utilize cutting-edge tools like the James Webb telescope along with biological, geological, and computer-modeling methods, she makes the science accessible and fun.

There’s Always This Year, by Hanif Abdurraqib

Basketball as a metaphor for life is only a (quick) first step into this powerful memoir by Hanif Abdurraqib. The author’s words celebrate not only coming-of-age but also agelessness. His goal, like that within the sporting arena, is clear: Protect home court.

Film

Amid gritty Chicago reality, two friends embrace childhood

For the Monitor’s reviewer, the young boys in “We Grown Now” exude something that is often difficult to find believable amid tough surroundings: innocence. The new film, he says, honors “just being a kid.”

Amid gritty Chicago reality, two friends embrace childhood

Years ago I reviewed a movie set in a gang-ridden Black neighborhood in Los Angeles. I wrote that its portrayal of a young girl, whose innocence was undimmed by all the violence, seemed unbelievable.

Not long after the review ran, I was invited to be a guest on a popular radio show with a Black host. After the usual introductory pleasantries, he laced into me for assuming that, amid the brutality, the girl’s purity of feeling was an impossibility.

He was right.

I was reminded of this incident while watching “We Grown Now,” an affecting low-budget feature written and directed by Minhal Baig, whose previous film, “Hala,” drew on her coming-of-age as a first-generation Pakistani American in Chicago. “We Grown Now” is likewise set in Chicago, in 1992, and centers on the friendship between two 12-year-old boys who both live in the notoriously dangerous and run-down Cabrini-Green housing project.

The home lives of these best buddies are markedly different. Malik (Blake Cameron James), with his younger sister, lives with his watchful single mother (Jurnee Smollett) and doting grandmother (S. Epatha Merkerson). Eric (Gian Knight Ramirez) lives with his single father (Lil Rel Howery), of whom we don’t see much.

Despite the ever-present hazards of their surroundings, culminating in the shooting death of a 7-year-old boy from the projects, Malik and Eric exude an almost transcendent guilelessness. They are self-aware enough to know that, despite everything, this is a precious time in their lives – a time when they can exult in just being a kid.

“Flying” is what they call their favorite pastime. They haul mattresses from abandoned apartments onto the local playground and then, after a running start, alight on them with a thud after jumping high in the air. Baig films these interludes in slow motion, so that we, too, can capture the exhilaration.

The film is almost entirely shot from the perspective of Malik and Eric, and yet Baig also makes us pointedly aware of the world outside the boys’ bubble. Particularly in the scenes in Cabrini-Green, she fills the soundtrack with a cacophony of neighborhood noise, which functions almost like a major character in the film. It echoes the interconnectedness of all who live in this blighted landscape.

First-time actors James and Ramirez are naturals, giving maybe the best kid performances I’ve seen since “The Florida Project.” The adults in the film, particularly Eric’s dad, are sometimes too sketchily filled in, but the acting mostly makes up for the lack. There’s a wonderful moment when Merkerson, as the grandmother, reminisces about her young life in Tupelo, Mississippi – she misses the people, not the place. She says at one point that “there’s poetry in everything.”

Perhaps it is she who inspires Malik’s imagination. In one scene, he and Eric lie on their backs looking up at a cracked apartment ceiling and fancy they are peering at constellations. When they play hooky from school and duck into the Art Institute of Chicago, they gape in rapid-fire wonderment at the canvases. Through the fenced-in grating in Cabrini-Green, they exult in unison, “We exist!”

We feel as protective of these boys as does Malik’s mother, wonderfully played by Smollett. Aghast at their truancy from school, she cries out, “How am I supposed to keep you safe?” Her wail undercuts the boys’ spiritedness and keeps the film from devolving into a homespun childhood idyll. She is aware, even if the boys are not, that the world out there is a minefield.

Her decision to leave her low-paying office job for a better one in a safer place, in far off Peoria, will pry the boys apart. Malik and Eric are still too unformed to fully comprehend what this separation will mean to their lives. They turn on each other because they don’t really know how to say goodbye. The power of this film sneaks up on you. It glides from jubilation to heartbreak without missing a beat.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “We Grown Now,” which rolls out in theaters starting April 19, is rated PG for thematic material and language.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The joy in Mexico’s election

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Every now and then, an election draws back a curtain, revealing a society striving toward its higher ideals. Mexico is in the middle of such revelation.

On June 2, voters will elect a new president, Congress, and thousands of local officials. Their top concern is violent crime, polls show. It may be surprising, then, that violent intimidation is not the prevailing sentiment among Mexico’s 130 million citizens. In a survey by a social media tracker, Mexicans described their outlook for the country more with words such as “joy” and “trust” than with words such as “anger” and “fear.” After the first presidential debate last week, positive reactions outweighed negative reactions by as much as 80%.

One reason for that optimism is a sense of history being made. The two top presidential candidates are women. By a large margin (52% to 15%), voters said a female president is the best option for the future.

Mexico’s struggle against organized crime is also a chronicle of its growth into democratic maturity. The country broke free from single-party rule only in the late 1990s. Since then, it has been seeking models of law enforcement and political pluralism immune from the corrupting influence of the cartels.

The joy in Mexico’s election

Every now and then, an election draws back a curtain, revealing a society striving toward its higher ideals. Mexico is in the middle of such revelation.

On June 2, voters will elect a new president, Congress, and thousands of local officials. Their top concern is violent crime, polls show. That is understandable. Some 200 armed groups operate throughout the country. The campaign is already on course to have the most assassinations or other acts of political aggression in history, the Wilson Center reports.

It may be surprising, then, that violent intimidation is not the prevailing sentiment among Mexico’s 130 million citizens. In weekly surveys by MilenIA, Central de Datos e Inteligencia Artificial, a social media tracker, Mexicans described their outlook for the country more with words such as “joy” and "trust” than with words such as “anger” and “fear.” After the first presidential debate last week, positive reactions outweighed negative reactions by as much as 80%.

One reason for that optimism is a sense of history being made. The two top presidential candidates are women. By a large margin (52% to 15%), voters said a female president is the best option for the future. That view is nearly equally held by men and women, polling by the Americas Society/Council of the Americas has found.

The qualifications of the two main candidates are a good part of their appeal. Claudia Sheinbaum, representing the ruling party, holds a Ph.D. in energy engineering. She served on a United Nations panel on climate change that won a Nobel Peace Prize. As mayor of Mexico City from 2018 to 2023, she oversaw a dramatic reduction in the capital’s homicide rate. Her opponent, Xóchitl Gálvez, is also a trained engineer. She lifted herself out of poverty to a distinguished career, first in business and now as a senator.

Mexico’s struggle against organized crime is also a chronicle of its growth into democratic maturity. The country broke free from single-party rule only in the late 1990s. Since then, it has been seeking models of law enforcement and political pluralism immune from the corrupting influence of the cartels.

This election marks an important step in that evolution. The two candidates – and a third, trailing further behind – differ on how to grow the economy. But their proposals for countering crime reflect similar degrees of compassion for people most vulnerable to violent crime, such as women and youth. Last month, the presidential candidates signed a National Commitment to Peace, organized by a coalition of interfaith religious leaders.

Ms. Sheinbaum emphasizes building schools and universities. Ms. Gálvez seeks higher salaries for police officers and their families. Ms. Sheinbaum talks about “the construction of peace.” Ms. Gálvez envisions “Mexico without fear.” One of them will be Mexico’s next president. A country weary of violence is already registering its approval with joy and trust.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A foundation for trust

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Lisa Rennie Sytsma

Looking to God, divine Love, for guidance empowers us to express and experience more integrity in our lives.

A foundation for trust

The tax collectors were asking for payment. Neither Jesus nor his disciple Peter had the cash.

Some Bible scholars believe Jesus felt that he, and possibly Peter as well, should be exempt from the tax, which was intended for the upkeep of the Temple in Jerusalem. In addition, some historians say that Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who later ordered Jesus’ execution, was appropriating Temple funds to build an aqueduct to bring water into Jerusalem. Public anger over this use of funds earmarked for something else caused riots.

To sum up: The tax collectors were asking Jesus for money he did not have to pay a tax he may have felt he didn’t owe that was possibly going to be misappropriated anyway.

Don’t we hear stories like this today? The term “trust deficit” may be fairly new, but the concept of people losing faith in each other, institutions, and the government is certainly not.

Christ Jesus is our Way-shower, so it’s helpful to look at what he did in circumstances such as these. Jesus didn’t respond to the tax collectors with fear, anger, ego, pride, or self-righteousness. He paid the tax with money supplied by divine Love. He told Peter to catch a fish, and a coin worth enough to pay taxes for them both would be in the fish’s mouth. And he told Peter the reason for paying was “lest we should offend them” (see Matthew 17:24-27).

That is, Jesus acted in love. He didn’t wait for a perfect government before loving and blessing everyone around him.

Of course there are legitimate reasons for governments to collect taxes. And on occasion, taxes become a flashpoint if enough people believe the money will be misused. But the issue of a trust deficit goes far beyond mere taxes. Individuals and communities might feel powerless in the face of institutional and governmental forces whose motives and objectives seem, or in some cases may actually be, hidden. Corruption may tempt those who hold power; suspicion may tempt those who don’t.

It’s useful to remember that acting out of love did not make Jesus either blind to or powerless before abuses of power. The love he expressed was the reflection of God, divine Love. Jesus understood that Love is the only power, the only creator, and created all things good. This understanding endowed him with wisdom, discernment, intelligence, and dominion. It endowed him without measure with Christ, the spiritual idea of the divine Principle, Love.

Because Jesus constantly expressed Love himself, he couldn’t help but see Love’s expression, true purity and goodness, in those around him. When individuals acted in deceptive and manipulative ways, he knew that deception and manipulation were no part of their true, God-given nature because they are no part of God. The Bible shows that this correct view healed.

Jesus expected us to follow his example. “If ye love me, keep my commandments,” he said (John 14:15). Love did not ask Jesus, and does not ask us, to give blanket trust to any person or human institution, though it does give us the wisdom and discernment to recognize when trust is warranted – or not. But whatever those around us are doing, Love demands that our own thoughts and actions be guided by the law of Love, blessing our fellows.

Obedience to Love turns our trust toward our Father-Mother God, who is forever worthy of trust. It teaches us to trust Love’s guidance and Love’s disposal of events and to act only as guided by Love.

Love provides abundantly. Her children never need to compete for scarce resources. Love upholds the unique and necessary contribution of every individual, destroying all desire for dominion over others. Countless individuals, and even communities, have been saved from abuses of power through the prayer that loves and refuses to accept as real anything but Love’s expression. There are also inspiring examples of those impelled by divine Love to express the highest integrity in government roles, even when under pressure to do the opposite.

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, writes, “Mankind will be God-governed in proportion as God’s government becomes apparent, the Golden Rule utilized, and the rights of man and the liberty of conscience held sacred. Meanwhile, they who name the name of Christian Science will assist in the holding of crime in check, will aid the ejection of error, will maintain law and order, and will cheerfully await the end – justice and judgment” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 222). That’s an outcome – and a government – we can all trust.

Adapted from an editorial published in the April 15, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Inspired to think and pray further about fostering trust around the globe? To explore how people worldwide are navigating times of mistrust and learning to build trust in each other, check out the Monitor’s “Rebuilding trust” project.

Viewfinder

We love that you’re here

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for our interview with Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin about her newest book.