With the world focused on Iran and Gaza, Israeli settlers are stepping up attacks against Palestinian towns and villages in the West Bank. Feeling abandoned, many residents believe they should take matters into their own hands.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

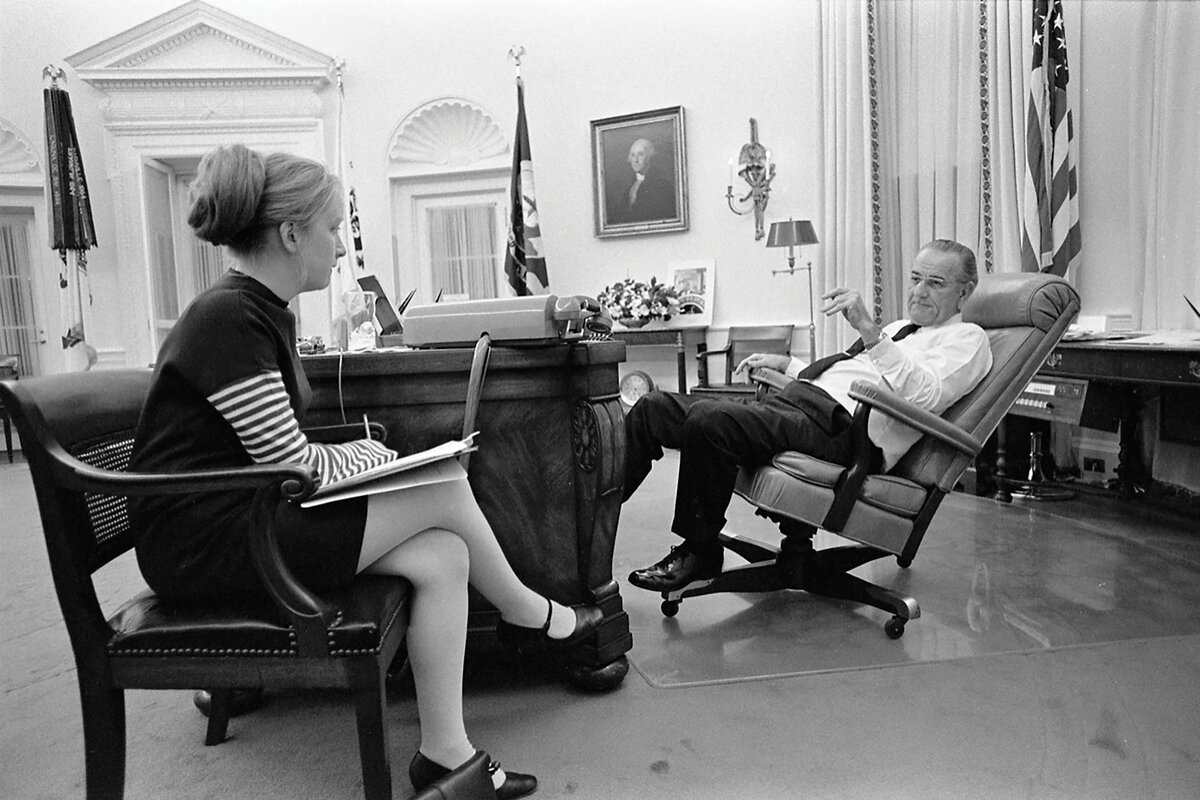

None of us should be shocked when Doris Kearns Goodwin says something profound. Reading Barbara Spindel’s Q&A today with one of America’s greatest historians is a must. At a moment when catastrophism is the dominant trend in political thought, it reminds us of the power and importance of context.

And therein lies wisdom. “The government is us,” she says. So a lack of trust in government is a “lack of trust in our own collective action as well.” By this measure, there is no enemy to defeat, no outcome to fear, only a bond of fellowship perpetually to rekindle.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 6 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Ukraine aid advances: The U.S. House of Representatives pushes a $95 billion national security aid package for Ukraine, Israel, and other allies closer to passage.

• New Title IX rules: The Education Department issues new Title IX regulations, which protect the rights of LGBTQ+ students by federal law and offer victims of campus sexual assault new safeguards.

• Iran sanctions: The United States announces new sanctions on Iran targeting its unmanned aerial vehicle production after its attack on Israel on April 13-14.

• Palestinian state vote: The United States stops the United Nations from recognizing a Palestinian state by casting a veto in the Security Council.

( 5 min. read )

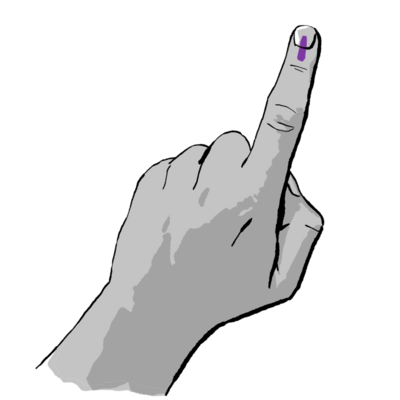

New concerns about the integrity of India’s elections are bubbling up to the surface. But as the world’s largest election gets underway, an enduring faith in the power of each vote is still driving people to the polls.

( 7 min. read )

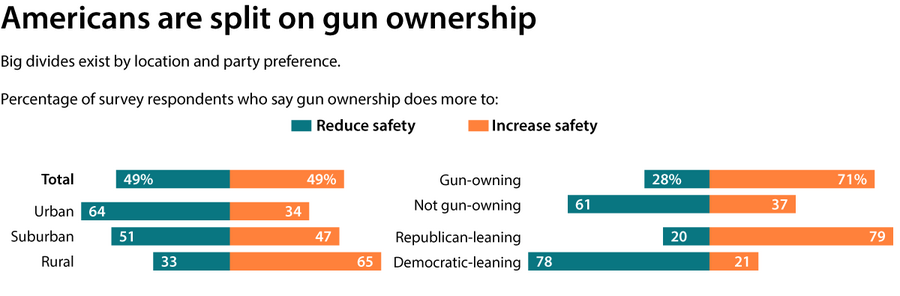

It’s been 25 years since the Columbine High School shooting. Americans continue to square off over the interplay of guns, safety, and health – with a trust gap hindering compromise.

( 5 min. read )

Globally, the vast majority of park rangers are men. But one gritty, determined group of female rangers in Kenya is shattering stereotypes and showcasing the particular skills that women bring to wildlife conservation.

( 4 min. read )

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s husband, Dick Goodwin, worked for President John F. Kennedy. She helped President Lyndon B. Johnson write his memoirs. Theirs was a marriage of deep respect and love, in the presence of history.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Despite nearly seven months of war between Hamas and Israel, and lately attacks between Iran and Israel, both Jews and Muslims living in Israel have not forgotten their religious holidays – and the meaning attached to them by prayer and ritual.

On Monday, Jews begin the seven-day celebration of Passover. In early April, Israeli citizens who are Arab Muslims ended the monthlong Islamic observance of Ramadan. These days of spiritual introspection, in their own ways, may be contributing to peace.

Israeli Arabs, who represent about a fifth of the country’s population, have been remarkably supportive of Israel during the war. More than half told a pollster that the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas does not reflect their values or those of Islam. And while they worry about the plight of Palestinians in Gaza, nearly two-thirds believe Hamas bears a great deal of responsibility. At the end of Ramadan, some 120,000 Muslim worshippers from both Israel and the West Bank prayed peacefully at the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem – despite calls by Hamas for violence.

For decades, many Israeli Muslims and Jews invited each other to celebrate their respective celebrations. During this latest war in Gaza, however, such visits have been canceled or diminished. “The feeling is that everything is sensitive and complicated,” Ilanit Haramati, program manager at Shared Paths, an organization that conducts walking tours for Jews in Arab communities, told Haaretz.

Despite that, some Muslims still invited their Jewish neighbors to help them break the daily fasts of Ramadan. In early April, as Ramadan ended, Israeli President Isaac Herzog hosted Arab mayors for a dinner at his residence, asking them to “join hands together against hatred and extremism.”

“Even if it seems distant, difficult, and impossible, I believe that peace will come,” he said.

The relative lack of violence between Israeli Jews and Arabs does not make much news. Yet the peace “is a cause for hope that religious faith may henceforth play an enhanced role in ending the horrible warfare presently ravaging a land sacred to all the Children of Abraham,” wrote Marc Schneier, president of the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, in The Jerusalem Post. Despite the tensions of war, the power of prayer, fasting, and even togetherness may be making a difference.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 2 min. read )

Prayer can open wide horizons of comfort, boundless love, and healing.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today, and we hope you have a lovely weekend. Among the stories we’re following for next week: A relative resurgence of the protest movement in Israel, President Joe Biden increasing his public visibility, and America’s trust in the Supreme Court.