- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A majority of Americans no longer trust the Supreme Court. Can it rebuild?

- Today’s news briefs

- Russia tried to stay on good terms with Iran and Israel. Then they started fighting.

- US child care is in crisis – and hardest on moms without degrees

- Israeli protesters are back on their feet. Missing is a unified voice.

- Are cattle herders I met in Ethiopia a climate threat?

- Commentary on Columbia: History, protests, and humanity

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What we lose when we fall into the ‘winner take all’ trap

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Henry Gass highlights a fascinating shift in the Supreme Court of the United States. Where once its rulings allowed for recourse among the losers, rulings today are more “winner take all.” This is not just a Supreme Court thing. It fits the political spirit of the time.

And that is telling. If this trend has led to less trust in the Supreme Court (and it has), then it’s no wonder it has made politics more toxic, too. “Winner take all” is not consistent with the ideals of America’s founders. So when we talk about ways to improve politics, changing that mindset might be a good place to start.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A majority of Americans no longer trust the Supreme Court. Can it rebuild?

As the U.S. Supreme Court prepares to hear a case Thursday on whether presidents have absolute immunity, trust in the high court remains near historic lows. But there is a way forward.

Four years ago, the Supreme Court of the United States was, by far, the most-trusted institution in Washington.

Now, as the high court nears the end of another potentially seismic term, public trust in the court has eroded.

Americans’ trust in the court dropped 20 points from 2020 to 2022, according to Gallup, to a record-low 47%. For the first time, a plurality of Americans (42%) viewed the court as “too conservative.”

Cases this term could further break, or buttress, trust in the court. On Thursday, former President Donald Trump will argue – to a high court that includes three justices he appointed – that he should have immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct while he was in office.

There is a clear path toward rebuilding trust, however. The Supreme Court had been the most-trusted government institution for decades because it acted with humility and avoided dramatically reshaping the law, legal experts say. The justices also modeled civility and how to work across ideological divides. With another potentially seismic term concluding in the next three months, the court has an opportunity to rise above the partisan turbulence of Washington again.

A majority of Americans no longer trust the Supreme Court. Can it rebuild?

Four years ago, the Supreme Court of the United States was, by far, the most-trusted institution in Washington.

Now, as the high court nears the end of another potentially seismic term, public trust in the court has eroded.

Americans’ trust in the court dropped 20 points from 2020 to 2022, according to Gallup, to a record-low 47%. For the first time, a plurality of Americans (42%) viewed the court as “too conservative.”

Partisanship has been a principal driver of the loss of trust. Since late 2020, the high court has had a 6-3 conservative supermajority. It has delivered several high-profile decisions favoring conservative policies, including overturning the right to abortion, ending affirmative action in college admissions, and expanding gun rights. While Republican confidence in the court has remained steady, trust has cratered among Democrats and some independents.

But the court is also taking, or being forced by lower courts to take, a steady diet of high-profile, politically charged cases. Meanwhile, the overall size of its docket is the smallest it’s been since the Civil War. As a result, the controversial cases take up even more oxygen. And the justices themselves, with ethics scandals and their public rhetoric, have at times given the impression that distrust is merited.

Cases this term could further break, or buttress, trust in the court. On Thursday, former President Donald Trump will argue – to a high court that includes three justices he appointed – that he should have immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct while he was in office.

There is a clear path toward rebuilding trust, however. The Supreme Court had been the most-trusted government institution for decades because it acted with humility and avoided dramatically reshaping the law, legal experts say. The justices also modeled civility and how to work across ideological divides. With another potentially seismic term concluding in the next three months, the court has an opportunity to rise above the partisan turbulence of Washington again.

“We’ve seen this real partisan trust gap emerge,” says Matthew Levendusky, a political scientist at the University of Pennsylvania who has studied public perception of the court.

“If it seems like it’s just another conservative institution, then that will further erode trust. But if they can combat that perception, that will help to go a long way toward restoring at least some of that,” he adds.

Charting the decline in trust

Trust in the high court bottomed out in 2022 after it overturned Roe v. Wade. According to numerous surveys, however, the decline began before that.

In December 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that a Texas law effectively outlawing abortion could stay in effect, even though it conflicted with Roe, which was then still the law. The justices did not overturn the constitutional right to abortion until June 2022, in a 6-3 decision along ideological lines.

Such partisan rulings have become a feature of recent terms. The same month it overturned Roe, the conservative supermajority also expanded gun rights, weakened the federal government’s regulatory power, and reshaped the boundaries of the church-state relationship.

While the high court decides big cases every year, in recent years “they’re big cases with a political valence, and that has not always been the case,” says Linda Greenhouse, author of “Justice on the Brink.”

“People don’t read Supreme Court opinions. ... What matters at the end of the day is what the court does,” she adds. And because of what the court has done in the past few years, “the public has measurably lost confidence in, and respect for, the Supreme Court.”

In the past, the Supreme Court maintained a high degree of public trust by making a habit of never straying too far from the middle. This didn’t mean avoiding consequential cases. It meant, in a broad sense, not rocking the country too far in one direction or another. Like blind Lady Justice holding her scales, it appeared to strive for balance.

Over the decades, that balance has been determined by a series of moderate “swing” justices. Among the most influential was Justice Anthony Kennedy. From the early 1990s to his retirement in 2018, he infuriated Democrats and Republicans alike with his unpredictability. His vote proved decisive in finding an individual right to bear arms, as well as an array of LGBTQ+ rights.

The Supreme Courts of the past issued landmark rulings that still provided recourse for losers.

When the court legalized same-sex marriage in 2015, Justice Kennedy stressed in the majority opinion that the First Amendment still protected those with sincere religious objections. The court has since ruled consistently in favor of those accommodations.

“History suggests that when the court does that it’s able to protect its public standing,” says Aaron Tang, a professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law. After dropping to 53%, public trust in the court rose into the high 60s a few years later, according to Gallup.

“More big cases does not mean people are going to distrust the court,” he adds. But “in recent years the Supreme Court has been deciding big cases in ways that leave the losers with no other real options for protecting their interests.”

When the high court overturned Roe v. Wade, for example, women who needed an abortion but couldn’t travel to a state that still allowed the procedure had no options. Similarly, when the court expanded gun rights, it gave little guidance to lawmakers and lower courts as to what kind of gun control regulations would be permissible moving forward.

Lower courts and “judge shopping”

The recent decline in trust is not entirely of the justices’ making, experts say.

While the high court has become more conservative, lower federal courts have arguably become even more so. Mr. Trump appointed more federal judges in one term than any president in history, including just under a third of active appeals court judges and over a quarter of district court judges.

The result has been controversial lower court decisions requiring the Supreme Court’s attention. The high court will rule on several this summer, including a high-profile case concerning mifepristone, a widely used abortion pill.

An anti-abortion group filed the lawsuit in a district court where the case was almost certain to be heard by a Trump appointee with a track record of fighting contraception access. That judge issued an injunction, effectively pulling the pill off the market nationwide. His injunction was partially upheld by a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The panel included two other Trump appointees.

Plaintiffs have long brought lawsuits in friendlier courts. Legal challenges to Mr. Trump’s policies often came through the more liberal 9th Circuit, for example. But lower courts have more frequently been issuing rulings that affect the whole country.

“A lot of those cases the court has to take, it doesn’t have a lot of choice,” says Jonathan Adler, a professor at Case Western Reserve University School of Law. “But it does affect perceptions.”

“There would be fewer cases for the court to intervene in if there were fewer nationwide injunctions,” he adds.

The U.S. Judicial Conference, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, issued a proposal last month that would limit “judge shopping” and the ability to issue nationwide injunctions. But it’s unclear the degree to which federal courts will implement the policies.

Scrutiny over ethics

The steady output of major, conservative-friendly decisions has understandably made some on the left more suspicious of the court. But Professor Adler and many on the political right believe the sudden decline in trust is part of a concerted campaign to delegitimize the court because liberals dislike its rulings.

This is especially the case with the ethical scandals over the past year. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito in particular have faced media scrutiny over lavish gifts and vacations they received – but didn’t disclose – over the decades from right-wing donors and activists. While the gifts do not appear to have influenced how the justices voted, critics say the attention has helped manufacture a legitimacy crisis around the court. In the wake of the scandals, the court adopted its first ever formal ethics code. It is one that court watchers say will change little about its practices.

In an editorial last year, The Wall Street Journal described the ethics scandal around Justice Thomas as “really about setting up an apparatus that politicians can then use against the Justices.”

Ms. Greenhouse, who covered the court for three decades, agrees that court-watchers have also become more polarized, pointing specifically to criticism of what she calls a “quite reasonable” ruling to keep Mr. Trump on Colorado’s presidential primary ballot.

“We’re seeing the court be both a victim of polarization and a cause of polarization,” she adds. “People on either side of the street have lost the ability to see the court objectively or clearly.”

The view from the inside

The justices themselves have at times questioned the court’s impartiality. During oral arguments in the case to overturn Roe, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked, “Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts? I don’t see how it is possible.”

Five months later, distrust flooded the court itself when Politico published a leaked draft opinion of the decision overturning Roe. Speaking later that month, Justice Thomas described it as “kind of like infidelity.”

“When you lose that trust, especially in the institution that I’m in, it changes the institution fundamentally,” he added.

Three months after the court overturned Roe, Justice Elena Kagan, a member of the court’s liberal wing, used public appearances to argue that the court’s legitimacy was in danger.

“The thing that builds up reservoirs of public confidence is the court acting like a court and not acting like an extension of the political process,” she said at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island.

“People are rightly suspicious if one justice leaves the court or dies and another justice takes his or her place and all of sudden the law changes on you,” she said at another event in Montana.

“If the court doesn’t retain its legitimate function, I’m not sure who would take up that mantle,” said Chief Justice Roberts at an event in Colorado. “You don’t want the political branches telling you what the law is, and you don’t want public opinion to be the guide of what the appropriate decision is.”

A year later, though, Justice Kagan introduced Chief Justice Roberts at a legal event in May 2023, lauding him as “a consummate legal craftsman.”

The chief justice used his speech to reassure lawyers that the justices remain on good working terms.

“I am happy that I can continue to say that there has never been a voice raised in anger in our conference room,” he said.

“When I wander down the halls and see a colleague, I am always happy to have the chance to chat,” he added, before making a qualification. “Now, to be fair, there are many days where I don’t feel like walking down the halls.”

Rebuilding trust takes time

A year after overturning Roe, the high court faced another year of high-profile cases. Immigration, voting rights, religious freedom, and affirmative action were all on the docket. So were some surprises.

The court, predictably, ruled that a website designer could refuse services for same-sex weddings. But it also ruled against a Republican-led state in upholding a critical section of the Voting Rights Act. And it struck down a novel theory that would have given state legislatures unilateral authority to regulate federal elections. The court also struck down affirmative action. According to Gallup, about two in three Americans viewed the ruling as “mostly a good thing,” though most Americans of color did not.

A few months later, Gallup recorded that trust in the high court had ticked up to 49%, with a plurality of Americans (42%) viewing its ideology as “about right.”

That is still below where public trust has been as recently as 2020. And the justices are nearing the end of another blockbuster term that is certain to move that needle.

In one major case, being argued Thursday, Mr. Trump is claiming that he has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for acts during his presidency. If the court rules in his favor, “that would leave no option for the public to hold any American president accountable for criminal wrongdoing,” says Professor Tang, author of “Supreme Hubris: How Overconfidence Is Destroying the Court – and How We Can Fix It.”

The abortion pill case could be another. Last year, medication abortion accounted for almost two-thirds of all abortions in the U.S. During oral arguments last month, the justices sounded skeptical that the case should have reached them at all.

If the court is going to rebuild public trust, “it will have to be rebuilt over time,” says Professor Tang. “The court will have to avoid more decisions that leave losing groups feeling like there’s no other choice but to assault the integrity of the Supreme Court.”

Today’s news briefs

• Biden signs TikTok ban: After years of attempts to ban the Chinese-owned app, a measure to outlaw the popular video-sharing service wins congressional approval and has been signed by President Joe Biden.

• New abortion case: The Supreme Court is considering a case that will determine when doctors can provide abortions during medical emergencies in states with bans.

• Arizona abortion ban: A proposed repeal of Arizona’s near-total ban on abortions wins approval from the state House, clearing its first hurdle a week after a court concluded the state can enforce an 1864 law.

• Tennessee gun law: Tennessee House Republicans pass a bill that would allow some teachers and staff to carry concealed handguns on public school grounds, and bar parents and other teachers from knowing who was armed.

• Argentinian student protests: Hundreds of thousands of Argentines fill the streets of Buenos Aires and other cities to demand increased funding for the country’s public universities.

Russia tried to stay on good terms with Iran and Israel. Then they started fighting.

Russia has walked a diplomatic tightrope in the Middle East, working with all sides. But the new tensions have forced a shift.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Moscow has tried to maintain good relations with all the major players in the Middle East, including Iran and Israel. For more than a decade, it succeeded.

But with Iran and Israel exchanging salvos recently, the Kremlin’s outreach to Tel Aviv may become a casualty.

“Russia still wants to keep a balance, and has no interest in seeing a big conflict in the Middle East, but Israel has become the big exception,” says Dmitry Suslov, an international affairs expert in Moscow.

Despite strong personal ties between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel has fallen back on its traditional friends in the West for support. Meanwhile, Russia has moved into an even tighter embrace with Iran, which it is increasingly relying on for military and economic partnership.

Still, if the Mideast situation did worsen, that might work out in the Kremlin’s interests.

“While Russia is not in favor of an Israeli-Iran war, it probably is interested in the continuation of managed tensions,” says Mr. Suslov. “It distracts from Ukraine and forces the U.S. to divert resources to Israel.”

Russia tried to stay on good terms with Iran and Israel. Then they started fighting.

For a long time, the Kremlin has done a diplomatic dance in the Middle East to maintain equally good relations with all the major players. And for more than a decade, it had succeeded beyond expectations, keeping workable, if not warm, terms with Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Iran simultaneously.

But that was before Israel and Iran threatened open hostilities against each other. Now, amid tensions in the Middle East – somewhat eased since an Israeli strike in Iran over the weekend – Moscow’s long-standing outreach to Tel Aviv may become a casualty.

Despite strong personal ties between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel has fallen back on its traditional friends in the West for support amid the deepening crisis. Meanwhile, Russia has moved into an even tighter embrace with Iran, which it relies on for weapons to fight the war in Ukraine, growing trade and economic cooperation, and vital assistance in evading Western sanctions – apparently including a fleet of “ghost tankers” to move Russian oil to world markets.

And if the situation between Iran and Israel does spiral, it could become a major problem for Russia.

“Relations with Israel have deteriorated, though both sides retain contact,” says Vladimir Sotnikov, an expert with the IMEMO Center for International Security in Moscow. Ideally, he says, “Russia wants to maintain ties with Israel, while strengthening its strategic partnership with Tehran. A war between Israel and Iran would not be beneficial to Moscow. But Russia’s ability to influence events is quite limited. ... If it were to be drawn into such a conflict, it would divert significant resources from its operations in Ukraine.”

The big exception

After Israel attacked Iran’s embassy in Damascus, Syria, on April 1, killing several top Iranian officials, Moscow issued a stern condemnation. Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations, Vasily Nebenzya, called it a “flagrant violation” of international law and alleged that “such aggressive actions by Israel are designed to further fuel the conflict. They are absolutely unacceptable and must stop.”

But following a retaliatory Iranian attack, involving 300 missiles and drones fired at Israel, Moscow only called upon the two sides to exercise greater restraint. In a subsequent telephone conversation with Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, Mr. Putin emphasized improving relations between the two countries, and both leaders agreed on the need to avoid a new round of confrontations.

“Russia still wants to keep a balance, and has no interest in seeing a big conflict in the Middle East, but Israel has become the big exception” to traditional efforts to stay on good terms with everyone, says Dmitry Suslov, an international affairs expert at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

He says that Israel disappointed Moscow by condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, even though it declined to supply lethal weapons to Kyiv. But basic channels of communication, and even cooperation in Syria, remained until the present. “Russia still does not shoot down Israeli planes and missiles over Syrian territory, although it could,” says Mr. Suslov.

Meanwhile, Russia has supplied some advanced weaponry to Iran, including S-300 air defense systems. Unconfirmed reports suggest that it’s ready to greatly upgrade Iran’s military capabilities with advanced Su-35 fighter planes, S-400 anti-aircraft systems, submarines, and more. Russia has not yet begun major deliveries of modern weapons to Iran, which experts variously ascribed to the demands of the Ukraine war on Russian military industry and Iran’s failure to make payment.

Trade between Russia and Iran has expanded rapidly in the past few years, in a wide range of goods beyond energy cooperation and weaponry. One big item is Russia’s investment of almost $700 million in an Iranian railway that will complete the last section of the North-South Corridor, a long-discussed and much-delayed transport route that would connect Iranian ports on the Indian Ocean with Russia’s vast railway network. The completed line would help defeat efforts to sanction Russia and could potentially rival the Suez Canal as a trade route.

“The company Russia wants to be part of”

That said, some Russian analysts don’t deny that the outbreak of conflict in the Middle East has benefited Russian diplomacy and relieved international pressure on Moscow over its war in Ukraine.

“While Russia is not in favor of an Israeli-Iran war, it probably is interested in the continuation of managed tensions,” says Mr. Suslov. “It distracts from Ukraine and forces the U.S. to divert resources to Israel.”

It also dovetails with Russia’s growing investment in alternative international forums that represent mainly countries of the Global South, such as the BRICS group (originally Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), where condemnation of Israel’s war in Gaza is nearly universal and Western attempts to drum up support for Ukraine have largely gone unheeded.

“It’s vital that Iran has joined BRICS along with several other countries of the global majority,” says Mr. Suslov. “This is the company Russia wants to be part of. It’s existential for us, and for the future world order we hope is being formed.”

A wider geopolitical realignment has been underway for some time, in which Russia, in concert with China, is seeking to build alternative economic and political alliances to replace the existing Western-led ones.

It helps to have common enemies, says Sergei Markov, a former Kremlin adviser. “Russia and Iran had lots of differences in the past,” he says, “but in the situation where they both find themselves in opposition to the U.S. and its world order, they are drawn together out of common interest.”

US child care is in crisis – and hardest on moms without degrees

Women have reached historic highs in the workforce. But one group is lagging, and lack of affordable child care is to blame. The Education Reporting Collaborative kicks off its series “Fixing the Child Care Crisis.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Moriah Balingit Associated Press

-

Sharon Lurye Associated Press

-

Daniel Beekman The Seattle Times

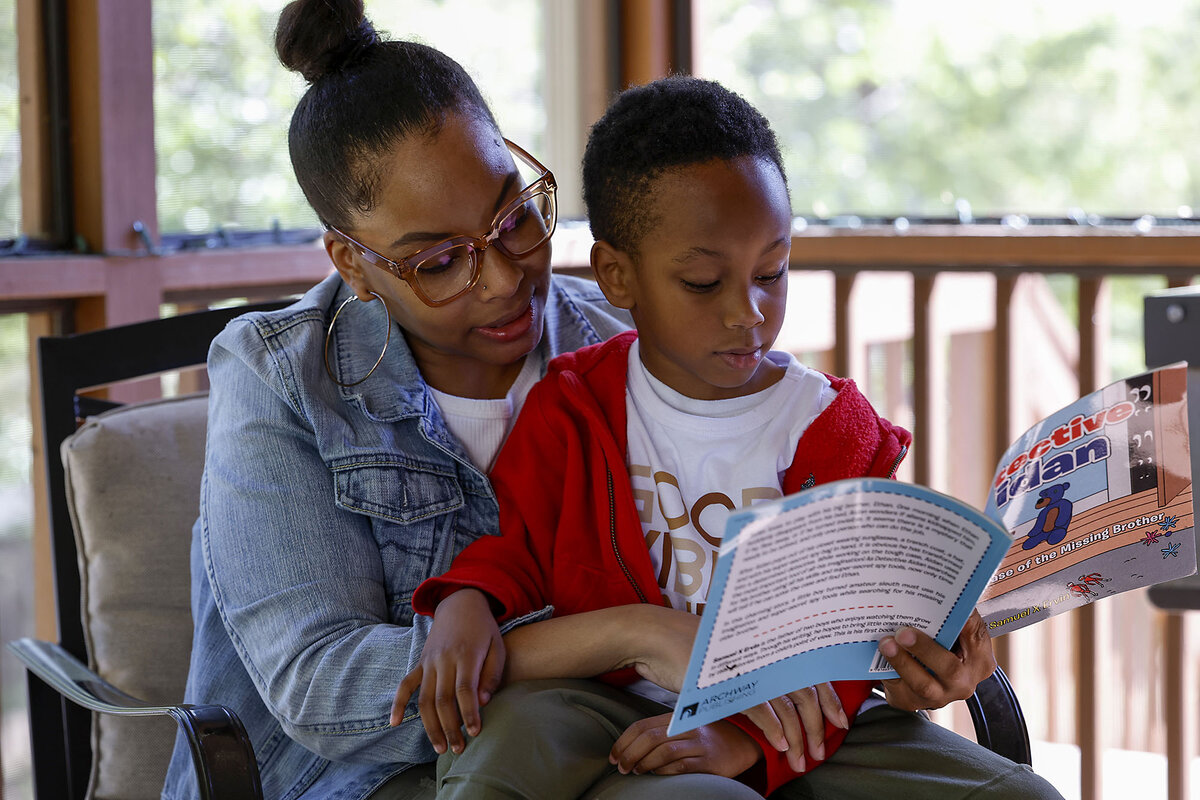

After a series of lower-paying jobs, Nicole Slemp finally landed one she loved.

She expected to return to her job in Washington state’s child services department after having her son in August. But the best option for child care would cost about $2,000 a month, with a long wait list. The least expensive option was around $1,600, still eating up most of Ms. Slemp’s salary. Her husband earns about $35 an hour at a hose distribution company. Between them, they earned too much to qualify for government help.

Ms. Slemp, who lives in a Seattle suburb, felt like she had no choice but to quit her job.

That dilemma is common in the United States, where high-quality child care programs are prohibitively expensive, government assistance is limited, and day care openings are sometimes hard to find at all.

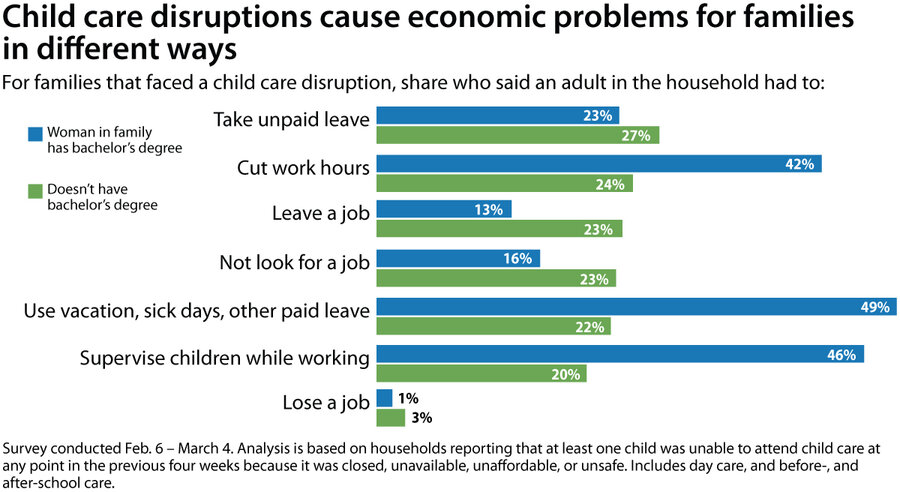

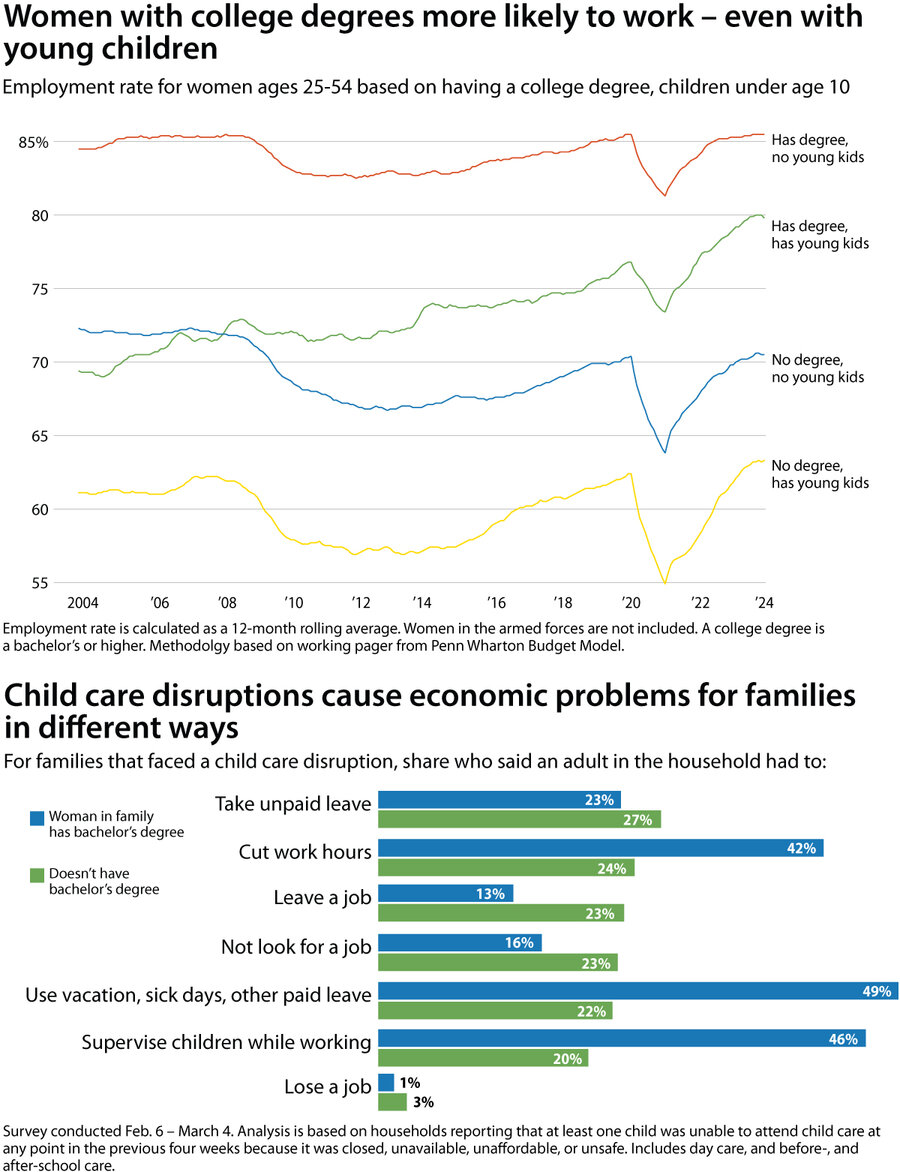

Women’s participation in the workforce has recovered from the pandemic, reaching historic highs in December 2023. But that masks a lingering crisis among women who lack a college degree: The gap in employment rates between mothers who have a four-year degree and those who don’t has only grown.

US child care is in crisis – and hardest on moms without degrees

After a series of lower-paying jobs, Nicole Slemp finally landed one she loved. She was a secretary for Washington’s child services department, a job that came with her own cubicle, and she had a knack for working with families in difficult situations.

Ms. Slemp expected to return to work after having her son in August. But then she and her husband started looking for child care – and doing the math. The best option would cost about $2,000 a month, with a long wait list, and even the least expensive option around $1,600, still eating up most of Ms. Slemp’s salary. Her husband earns about $35 an hour at a hose distribution company. Between them, they earned too much to qualify for government help.

“I really didn’t want to quit my job,” says Ms. Slemp, who is in her 30s and lives in a Seattle suburb. But, she says, she felt like she had no choice.

The dilemma is common in the United States, where high-quality child care programs are prohibitively expensive, government assistance is limited, and day care openings are sometimes hard to find at all. In 2022, more than 1 in 10 young children had a parent who had to quit, turn down or drastically change a job in the previous year because of child care problems. And that burden falls most on mothers, who shoulder more child-rearing responsibilities and are far more likely to leave a job to care for kids.

Even so, women’s participation in the workforce has recovered from the pandemic, reaching historic highs in December 2023. But that masks a lingering crisis among women like Ms. Slemp who lack a college degree: The gap in employment rates between mothers who have a four-year degree and those who don’t has only grown.

For mothers without college degrees, a day without work is often a day without pay. They are less likely to have paid leave. And when they face an interruption in child care arrangements, their families are far more likely to adjust by giving up work, according to an analysis of Census survey data by the Education Reporting Collaborative.

In interviews, mothers across the country shared how the seemingly endless search for child care, and its expense, left them feeling defeated. It pushed them off career tracks, robbed them of a sense of purpose, and put them in financial distress.

Women like Ms. Slemp challenge the image of the stay-at-home mom as an affluent woman with a high-earning partner, says Jessica Calarco, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“The stay-at-home moms in this country are disproportionately mothers who’ve been pushed out of the workforce because they don’t make enough to make it work financially to pay for child care,” Dr. Calarco says.

Her own research indicates three-quarters of stay-at-home moms live in households with incomes less than $50,000, and half have household incomes of less than $25,000.

Still, the high cost of child care has upended the careers of even those with college degrees.

When Jane Roberts gave birth in November, she and her husband, both teachers, quickly realized sending baby Dennis to day care was out of the question. It was too costly, and they worried about finding a quality provider in their hometown of Pocatello, Idaho.

The school district has no paid medical or parental leave, so Ms. Roberts exhausted her sick leave and personal days to stay home with Dennis. In March, she returned to work and husband Mike took leave. By the end of the school year, they’ll have missed out on a combined nine weeks of pay. To make ends meet, they’ve borrowed money against Jane’s life insurance policy.

In the fall, Ms. Roberts won’t return to teaching. The decision was wrenching. “I’ve devoted my entire adult life to this profession,” she says.

For low- and middle-income women who do find child care, the expense can become overwhelming. The Department of Health and Human Services has defined “affordable” child care as an arrangement that costs no more than 7% of a household budget. But a Labor Department study found fewer than 50 American counties where a family earning the median household income could obtain child care at an “affordable” price.

There’s also a connection between the cost of child care and the number of mothers working: a 10% increase in the median price of child care was associated with a 1% drop in the maternal workforce, the Labor Department found.

In Birmingham, Alabama, single mother Adriane Burnett takes home about $2,800 a month as a customer service representative for a manufacturing company. She spends more than a third of that on care for her 3-year-old.

In October, that child aged out of a program that qualified the family of three for child care subsidies. So she took on more work, delivering food for DoorDash and Uber Eats. To make the deliveries possible, her 14-year-old has to babysit.

Even so, Ms. Burnett had to file for bankruptcy and forfeit her car because she was behind on payments. She is borrowing her father’s car to continue her delivery gigs. The financial stress and guilt over missing time with her kids have affected her health, she says. She has had panic attacks and has fainted at work.

“My kids need me,” she says, “but I also have to work.”

Even for parents who can afford child care, searching for it – and paying for it – consumes reams of time and energy.

When Daizha Rioland was five months pregnant with her first child, she posted in a Facebook group for Dallas moms that she was looking for child care. Several warned she was already behind if she wasn’t on any wait lists. Ms. Rioland, who has a bachelor’s degree and works in communications for a nonprofit, wanted a racially diverse program with a strong curriculum.

While her daughter remained on wait lists, Ms. Rioland’s parents stepped in to care for her. Finally, her daughter reached the top of a waiting list – at 18 months old. The tuition was so high she could only attend part-time. Ms. Rioland got her second daughter on waiting lists long before she was born, and she now attends a center Ms. Rioland trusts.

“I’ve grown up in Dallas. I see what happens when you’re not afforded the luxury of high-quality education,” says Ms. Rioland, who is Black. “For my daughters, that’s not going to be the case.”

Ms. Slemp still sometimes wonders how she ended up staying at home with her son – time she cherishes but also finds disorienting. She thought she was doing well. After stints at a water park and a call center, her state job seemed like a step toward financial stability. How could it be so hard to maintain her career, when everything seemed to be going right?

“Our country is doing nothing to try to help fill that gap,” Ms. Slemp says. As a parent, “we’re supposed to keep the population going, and they’re not giving us a chance to provide for our kids to be able to do that.”

Carly Flandro of Idaho Education News, Valeria Olivares of The Dallas Morning News, and Alaina Bookman of AL.com contributed to this report. Moriah Balingit reported from Washington, D.C., and Sharon Lurye from New Orleans.

This article, the first in the series “Fixing the Child Care Crises,” was produced by the Education Reporting Collaborative, a coalition of eight newsrooms that includes AL.com, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News, The Hechinger Report, Idaho Education News, The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina, and The Seattle Times.

Israeli protesters are back on their feet. Missing is a unified voice.

Among the ingredients that successful protest movements need are unity and clarity. Huge pro-democracy demonstrations in Israel last year had that. Six months into the war in Gaza, the ranks of Israeli protesters are growing. But their agenda is overflowing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Shoshanna Solomon Contributor

Free the hostages. Hold elections. Share the burdens of war.

Protesters are filling Israel’s streets. Again.

But Israelis are dealing with so many issues simultaneously that the protesters – many of whom demonstrated last year to protect Israel’s democracy – don’t know what to shout loudest.

Before the war in Gaza, demonstrators had the “very concrete target” of preventing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from implementing his proposals to overhaul the judiciary, explains Professor Tamar Hermann at the Israel Democracy Institute.

But at demonstrations since the war began, she says, almost 80 different minor groups are calling for a variety of things, including Mr. Netanyahu’s ouster and the formulation of a day-after-the-war plan. The “overarching principle,” she says, is dissatisfaction with the government.

Still, this lack of focus, even guilt about demonstrating when soldiers are dying, is sapping the protests’ energy, participants say.

“We’re juggling so many balls; it’s hard to keep track of all of them,” says Uriel Abulof, a political scientist at Tel Aviv University. “What we are seeing ... is a deep fatigue, because we have been doing so much for such a long time. Many people are, simply put, tired.”

Israeli protesters are back on their feet. Missing is a unified voice.

At the intersection of Tel Aviv’s Kaplan and Begin streets, some demonstrators were putting up posters that called for immediate elections.

Thousands of others, wrapped in Israeli flags or beating drums, listened to a speaker urging the military conscription of the nation’s ultra-Orthodox religious population to share the burden of war.

From a few hundred yards away, one could hear the anguished and angry cries of “Deal now!” by the families of hostages seized by Hamas one horrible day in October, demanding the government negotiate their release.

The two demonstrations eventually merged, as the political rally joined up with that of the families.

Once the protesters got home that Saturday night, they watched on their TV screens the surreal unfolding and interception of Iran’s missile-and-drone barrage. On Sunday, everyone was back at work and in coffee shops.

Israelis currently are dealing with so many issues simultaneously that protesters, among them many of the hundreds of thousands who took to the streets last year against the Netanyahu government’s proposed judicial overhaul, don’t really know what to shout about loudest.

Before the war in Gaza, demonstrators had the “very concrete target” of saving democracy by preventing Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from implementing his reforms, explains Professor Tamar Hermann, a senior research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute.

But at demonstrations since the war began, protesters – generally older people – are from almost 80 different minor groups calling for a variety of things, including Mr. Netanyahu’s ouster and the formulation of a day-after-the-war plan.

The “overarching principle,” Professor Hermann says, is that of dissatisfaction with the current government.

Fatigue, focus, guilt

But the lack of focus, an immense tiredness, and even guilt about holding political rallies when soldiers are dying for the country are sapping the protests’ energy and participation, attendees say.

“We’re juggling so many balls; it’s hard to keep track of all of them,” says Uriel Abulof, an associate professor of political science at Tel Aviv University. “What we are seeing ... is an ongoing and growing exhaustion, a deep fatigue, because we have been doing so much for such a long time. Many people are, simply put, tired.”

From January 2023, Israel was roiling with protests against the proposed judicial overhaul, which detractors said would weaken the nation’s democratic checks and balances. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets on Saturday nights, in Tel Aviv and other cities.

The protests peaked in March that year, after Mr. Netanyahu fired his defense minister, Yoav Gallant, who called for dialogue and a pause in legislation that he said was endangering state security. Some 400,000 citizens and a general strike brought the country to a standstill.

Mr. Netanyahu blinked; Mr. Gallant was reinstated.

Then on Oct. 7, a stunned nation was thrust into mourning, and war against Hamas. The protests stopped in a show of unity, and many demonstrators were called up to fight.

The protest movement pivoted, mobilizing its network to set up an army of volunteers who fed, equipped, and transported soldiers; provided hot meals and clothing for evacuees from front-line communities; worked abandoned farms; and stepped in where state institutions failed.

“Sense of frustration”

Some two months into the war, however, anti-government protests resumed and have been gaining momentum since. Considering the scope of the government’s and army’s failure to keep citizens safe and to bring many of the hostages home, the demonstrations might be thought surprisingly mild.

South African-born Jonathan Schwartz, a lawyer and grandfather, has taken part in almost all the anti-Netanyahu protests – both before and after the start of the war.

The demonstrations are “totally lacking energy,” he admits. “There is a sense of frustration.”

Mr. Schwartz, whose son, daughter, and nephew were called up for military reserve duty after Oct. 7, says the fact that the war is ongoing is a key factor keeping people at home.

He goes to these rallies because he feels he has “no choice,” he says. “But I don’t think they will succeed.”

His brother-in-law, Maxie Garb, who used to march alongside Mr. Schwartz in the protests, hasn’t been attending the political rallies since the start of the war.

“I don’t feel comfortable going to political demonstrations while we still have hostages [in Gaza] and soldiers dying in the war,” Mr. Garb says. Demonstrating now will not make a difference, he adds, and the priority should be getting the hostages back. “Once the fighting is over, everybody will come out in force, and there will be very big demonstrations to change the government.”

To have an effective grassroots movement, says Professor Hermann, you need the power of numbers, which is not yet manifest at the recent demonstrations, because people “are focused on getting their life in order” amid the trauma of Oct. 7 and the exhaustion of war.

“People [are] coming back after many days in military service; there are those that were evacuated from their homes; people are focusing on their family, businesses, and their psychological situation,” she says.

The protest “muscle”

Nevertheless, the protests have been gaining momentum. Tens of thousands of people gathered in front of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, in Jerusalem March 31 at the start of a four-day demonstration, for which protesters and hostages’ families pitched tents.

On April 13, just before the Iranian strike, scores of thousands of people attended rallies in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

“It’s a muscle you need to stretch again,” says Lee Hoffmann Agiv, field operations manager for Bonot Alternativa. Her women’s rights advocacy group created the stunning displays of women dressed in red “handmaids” attire during protests against the judicial overhaul.

People will come out in full force once the time is right, she says, forecasting that that could happen in May, when the Knesset reconvenes and after the nation marks Memorial Day and Independence Day.

Others, like Tel Aviv University’s Dr. Abulof, think the trigger will be when opposition leaders Benny Gantz and Gadi Eisenkot leave the emergency wartime government.

“I believe we will have two very intensive months,” at the end of which “we’ll have to finish the job, make the government step down, and go to elections,” says Ms. Hoffmann Agiv. “We have no choice; that’s the money time.”

Are cattle herders I met in Ethiopia a climate threat?

A U.N. report suggests that pastoralism may be part of the global emissions problem. Some researchers see the climate math on herders differently. The debate could affect nomadic and pastoral cultures worldwide.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In early 2020, just before the world locked down, I was in Ethiopia as a journalist, documenting the challenges faced by a tribe of nomadic pastoralists that has made its home in the Danakil Desert for over 1,000 years.

About 1.5 million Afar tribespeople migrate across an area larger than Ireland with their camels, cattle, sheep, and goats to wherever grass happens to be growing at any given time. They increasingly face persistent drought and rising temperatures.

Today, their way of life is also coming under pressure in some quarters as a contributor to the global climate crisis, due to the methane emissions of their herds compared with newer livestock methods.

Some scientists, however, say there’s no environmental reason to turn away from pastoralism. “Pastoralism is basically a fossil-fuel-free, totally solar-powered production system,” said Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, a co-founder of the League for Pastoral Peoples.

Thinking back to my experiences in Ethiopia, I recall what one Afar woman told me after walking for 10 days with her cattle and donkeys in search of pasture. “I never dream of moving to town.”

Are cattle herders I met in Ethiopia a climate threat?

In early 2020, just before the world locked down, I was in Ethiopia as a journalist, documenting the challenges faced by a tribe of nomadic pastoralists that has made its home in the Danakil Desert for over 1,000 years. About 1.5 million Afar tribespeople migrate across an area larger than Ireland – and often called the hottest and driest place on Earth – with their camels, cattle, sheep, and goats to wherever grass happens to be growing at any given time.

I found some of the threats to their way of life to be region-specific, such as armed conflict with an aggressive neighboring tribe and locust plagues that decimated their already scant rangelands. But some of their other, even more intractable problems are shared by the estimated 200 million pastoralists around the world – the persistent drought, rising temperatures, and unpredictable weather patterns that scientists say are hallmarks of climate change.

“Life used to be good here. There was once so much grass, and it grew so high, that hyenas could hide in it and we couldn’t see them,” remembered Doge More, an Afar man in his 50s who didn’t know his exact age. “Now, there is no rain, so there are no grasses. We can’t keep cows anymore, and most people have very few animals at all. So what do we eat?”

Today, their way of life is under threat not only from changing conditions on the ground. Pastoralist communities are also coming under pressure in some quarters as a contributor to the global climate crisis. A December 2023 report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, for example, seeks to provide “a comprehensive assessment of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from livestock agrifood systems.” Some researchers say the report, in effect, suggests that pastoralism is part of the emissions problem.

That idea may sound hard to imagine. Like other pastoralist communities I’d written about and photographed over the years – all of whom are experiencing impacts of climate change firsthand – the Afar rely little on fossil fuels. They eschew consumer culture – partly due to poverty, partly because everything they own, including their huts, must be portable.

But when researchers calculate the amount of greenhouse gasses generated by a livestock system, most compare the amount of methane and carbon dioxide that’s emitted to the amount of protein that’s produced. By that measure, animals raised by traditional pastoralists are less efficient than those raised with newer, more intensive methods, the report says.

This is partly because indigenous breeds of livestock, well suited to their often harsh environments, are less productive than so-called improved breeds that are raised on farms. Additionally, a diet of wild grasses causes livestock to create more methane than if they eat formulated feeds.

The FAO report stops short of condemning pastoralism outright. It notes that pastoralist emissions make up only a fraction of the world’s total methane output. And it recognizes that moving away from traditional grazing may be “unfeasible” for the world’s poorest countries due to “nutritional challenges and ... financial constraints.” But the report’s recommendations point away from pastoralism.

Is that pragmatism or a flawed narrative, like others that have pushed Indigenous and pastoralist peoples off their traditional lands?

The future of pastoralism may hinge on the answer. Climate policy experts widely agree that major changes are needed in agriculture, and notably the raising of livestock, to help tame the rise of heat-trapping gasses in Earth’s atmosphere. If policymakers believe traditional herds stand in the way of hitting methane targets, pastoralists may be pressured to stop herding. Age-old cultures could disappear, along with food systems that make resourceful use of marginal lands where crops won’t grow.

Already, for example, a 2021 policy brief by The Lancet has recommended that India, home to some 13 million to 20 million pastoralists, “needs to move away from the traditional animal husbandry practices” in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Some scientists, however, say there’s no environmental reason to turn away from pastoralism. The data behind the FAO report, and others like it, answers the wrong question, says ecologist Pablo Manzano, a fellow and rangeland expert at Spain’s Basque Centre for Climate Change.

Rather than looking only at methane levels produced by pastoralist herds, researchers should focus instead on how those compare with the emissions that would be produced by the same ecosystems if herds were absent, Dr. Manzano says.

“Many of those emissions are going to happen, whether or not livestock is there,” he says.

Should pastoralist herds be removed from their landscapes, the void that they leave would likely be filled by other herbivores, he argues, which would produce similar amounts of methane.

Additionally, responsible grazing keeps grasslands healthy, increasing biodiversity and providing a natural carbon sink, while reducing the risk of wildfires, Dr. Manzano says.

In an email response, FAO says it focuses on estimating methane emissions “from all livestock systems, including pastoral systems.” That approach leaves out the additional factors raised by Dr. Manzano.

Questions regarding pastoralism are just one piece of the larger puzzle about how human land use and food production should evolve to address climate change. But to those who live within pastoralist societies, the implications are particularly large.

“Pastoralism is basically a fossil-fuel-free, totally solar-powered production system that does not require feed inputs, fertilizers, or pesticides,” said Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, a veterinarian who has lived closely with the Raika tribe in Rajasthan, India, since 1990, and who is a co-founder of the League for Pastoral Peoples. “But it is under pressure worldwide, and has in many places already become extinct.”

Thinking back to my experiences in Ethiopia, I recall what one Afar woman told me, which echoed the sentiments of many of the pastoralists I’ve spent time with over the years. “Our life depends on animals. It’s all we know,” said Hasina Wegris Al-Mohammed, who had just walked for 10 days across the desert with her cattle and donkeys in search of pasture. Despite the hardships of her nomadic life, she expressed no interest in trading it for a settled one. “I never dream of moving to town,” she said.

Commentary on Columbia: History, protests, and humanity

After arrests at Columbia University and other schools, our commentator considers the legacy of civil disobedience. How and why does society’s lens on protests change over time?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

There was a political theorist who famously said there are decades when nothing happens, and weeks when decades happen. As someone who writes about history a good bit, I think we should take those decades when “nothing happens” to remember flashpoints.

When I saw students at Columbia University engaging in a pro-Palestinian protest last week, I thought about South Carolina State University, about Kent State, about Jackson State, and about Southern University.

When more than 100 students were arrested in New York City after said protest, my concerns went to the natural escalation that occurs when the people clash with the police, when people push back against war.

How will history remember the protests at Columbia and other schools? How do we feel about civil disobedience in the moment – and years later? Can protest movements be truly understood in their own time, or does it take the passage of years for the effects of civil disobedience on a society to become clear?

Commentary on Columbia: History, protests, and humanity

There was a political theorist who famously said there are decades when nothing happens, and weeks when decades happen. As someone who writes about history a good bit, I think we should take those decades when “nothing happens” to remember flashpoints.

When I saw students at Columbia University engaging in a pro-Palestinian protest last week, I thought about South Carolina State University, about Kent State, about Jackson State, and about Southern University. When more than 100 students were arrested in New York City after said protest, my concerns went to the natural escalation that occurs when the people clash with the police, when people push back against war.

I understand that pushback, because I never met my uncle, my dad’s older brother. A few days after his 20th birthday, he was killed in Vietnam. The presidential election year of 1968 was a harrowing one that hit close to home for my dad, who would later decide to attend South Carolina State. Only three months before my uncle died, a student protest ended in tragedy during the events that are now known as the Orangeburg Massacre. Students from SC State and Claflin University sought to desegregate a local bowling alley, which led to an eventual clash with police. It was the first instance of police killing protesters at an American university.

I asked my dad, who was a teenager in the midst of the profound protests of the 1960s and 1970s, if he ever thought he might see these types of campus movements again. He said no. Yet here we are.

Early Monday, in response to such resistance, dozens of students were arrested at Yale University. Columbia, meanwhile, moved its classes online amid the fervor. On Monday evening, protesters at New York University were arrested and their encampment cleared out. Cal Poly Humboldt in Arcata, California, is closed and having classes online due to protests.

How will history remember the protests at Columbia and other schools? How do we feel about civil disobedience in the moment – and years later? Can protest movements be truly understood in their own time, or does it take the passage of years for the effects of civil disobedience on a society to become clear?

Even calls for safety at this moment invite polarity – the clashes between pro-Palestinian protesters and the police, the statements from the Biden administration about “physical intimidation” and antisemitism toward Jewish students. This is the nature of civil disobedience – the urgent need for humanity, with tinges of controversy.

If history is any guide, ambivalence toward civil disobedience will evolve into appreciation over time. Martin Luther King Jr., one of the great champions of civil disobedience, was not appreciated in his time for his anti-war rhetoric about Vietnam. In fact, the NAACP voted to determine that it was a “serious tactical mistake.” Nor was his stance of nonviolence always appreciated – whether by segregationists or by activists who sought more direct action.

What softened society’s stance? Was it loss of life? King paid for his beliefs with his life, as did the young adults during the 1960s and 1970s who lost their lives on college campuses. If that is the case, then it is a cost too great to pay.

This is why the current escalation on college campuses pulls at my heartstrings. The anti-war message is cogent, as are the calls for colleges to divest from the war on Gaza.

The anti-war protests come after 26 million people took to the streets after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in 2020 – the largest protest movement in U.S. history. And after young people across the country campaigned for gun safety laws after the Parkland massacre in 2018. And after millions of women turned out for reproductive rights after the election of President Donald Trump in 2016, who went on to keep his campaign promise to appoint Supreme Court justices who would overturn Roe v. Wade.

Sometimes, it seems the only acts that seem to cut through the nation’s conscience are violent ones.

When police opened fire at SC State in Orangeburg, in February 1968, they killed three teenage students – Samuel Hammond Jr., Henry Smith, and Delano Middleton (a high schooler). At Kent State, Allison Krause, age 19; Jeffrey Glenn Miller, 20; Sandra Lee Scheuer, 20; and William Knox Schroeder, 19, were gunned down by National Guard members.

Eleven days after the Kent State shootings, a Jackson State student and a high school student were shot and killed by police at Lynch Street, a familiar site for protests – Phillip Gibbs, 21, and James Green, 17. The close proximity of the events led to presidential action by Richard Nixon, who established the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest. Part of the commission’s report included this chilling commentary:

One of the most tragic aspects of the Jackson State College deaths ... is that – despite the obvious existence of racial antagonisms – the confrontation itself could have been avoided. The Commission concludes that the 28-second fusillade from police officers was an unreasonable, unjustified overreaction.

There are few people today who argue with the moral aptitude of the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s. We revere the sacrifices of the everyday people who participated in the Montgomery bus boycott, the folks who marched on Washington. Columbia University has historically been a house of protest, and student movements have changed the world since the life and times of Ella Baker and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

With the ultimate respect to the sit-in movements that made SNCC legendary, the time is now for people of conscience to step up. My uncle’s name is forever inscribed on a wall that remembers the sacrifices of the people who fought for a better world.

In a different world, I might have gone to Uncle Woodrow’s house to watch cartoons or play catch. That would have saved my dad, his mom, and younger brother a great deal of heartache. Much like the anti-war sentiments between 60 years ago and now, I appreciate the similarities between my uncle and me, even though we never met.

My prayer is that we can have the same appreciation for champions of civil disobedience – in the present, as well as the future.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

West Africa’s model of ballots over bullets

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In early April, the military-run regime in the West African country of Mali banned all political activity. The reason given? For the sake of “public order.” Yet the timing suggests another factor. In neighboring Senegal just the month before, citizens voted out an incumbent president after his unlawful attempt to stay in office. This peaceful transfer of power through democracy did not go unnoticed in a region overrun in recent years by military coups and violent jihadism.

In Mali and neighboring states, militaries have seized power and turned to such patrons as China, Russia, and Iran to help them fend off growing popular discontent. “That is why Senegal is so important,” says John Kayode Fayemi, a visiting professor at King’s College London and former governor of the Nigerian state of Ekiti.

The new government in Senegal has kindled new hope among citizens and civil society groups across the region. Through peaceful protest and judicial independence, the Senegalese people and their institutions thwarted antidemocratic moves by then-President Macky Sall to stay in power.

Bassirou Diomaye Faye’s victory, the United States Institute of Peace noted, “signals that young leaders can win power through ballot boxes and not through bullets.”

West Africa’s model of ballots over bullets

In early April, the military-run regime in the West African country of Mali banned all political activity. The reason given? For the sake of “public order.” Yet the timing suggests another factor. In neighboring Senegal just the month before, citizens voted out an incumbent president after his unlawful attempt to stay in office. This peaceful transfer of power through democracy did not go unnoticed in a region overrun in recent years by military coups and violent jihadism.

In Mali and neighboring states, militaries have seized power and turned to such patrons as China, Russia, and Iran to help them fend off growing popular discontent. “That is why Senegal is so important,” said John Kayode Fayemi, a visiting professor at King’s College London and former governor of the Nigerian state of Ekiti, during a webinar by Africa Confidential.

Since 2021, six countries along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert known as the Sahel have fallen under military rule. For a while the rebellious officers won hearts with promises of greater security, corruption reform, and eventual elections. Those promises weren’t kept. Extremist violence has spread, curtailing the movement of goods and people. Trade and food production have fallen sharply.

Those challenges coincide with strategic realignments. Once a key partner with the West in countering terrorism, Niger expelled French troops last July and last month broke its security pact with the United States. Encouraged by Moscow, it has also left the regional trade and military bloc along with Mali and Burkina Faso.

The new government in Senegal has kindled new hope among citizens and civil society groups across the region. Through peaceful protest and judicial independence, the Senegalese people and their institutions thwarted antidemocratic moves by then-President Macky Sall to stay in power. Jailed opposition leaders were released. Voter participation soared for the election.

At his inauguration on April 2, new president Bassirou Diomaye Faye pledged “to govern with humility and transparency, and to fight corruption at all levels.” His election may reset the balance of foreign influence. Mr. Faye hosted European Council President Charles Michel this week for talks on trade, fisheries, and economic development. “We share a common ambition ... based on two key principles: respect and trust,” Mr. Michel said.

Elsewhere in the region, from Guinea to Cameroon, people are taking note. “Senegal has given more power and solid arguments to pro-democracy activists in ... the rest of West Africa to say there are no other ways to follow but the democratic way for stability and development in our countries,” Ibrahima Diallo, a human rights activist in Guinea, told the Voice of America.

Mr. Faye’s victory, the United States Institute of Peace noted, “signals that young leaders can win power through ballot boxes and not through bullets.” No wonder Mali’s generals are worried.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What stillness brings

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

When we pause to let divine Soul inspire us, we find greater peace and harmony, as this poem conveys.

What stillness brings

When I need to sit on my mental

hands, my prayer reaches for

stillness, like that of a glazed lake

where no ripples fragment the

motionless replica of trees and sky;

but what if the blustering tempest

of what-ifs just keeps swirling?

Deeper, we can accept with joy God’s

shepherding of us to the stillness

of Soul – palpably felt-in-the-storm

serenity – supremely unmoved,

unstirred by hollow human currents

of fear and winds of worry; the limitless

calm only God, Spirit, can give – forever

expressed in His profoundly loved,

wholly spiritual children – all of us,

whose Soul-derived divine nature

truly rests in sacred stillness.

Prayerful stillness wakes us to our

unity with pure good, urges us to take

in its reality, makes us alive to its

constant presence.

Quietly attuned only to God, good, no

wonder we hardly notice the storm’s end.

Viewfinder

Inundated

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. I hope you’ll come back tomorrow for Ned Temko’s column about Sudan, which is a conflict the world should not lose sight of. Ned is seeing new sparks of engagement from the United States.