- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Trump looks likely to lose immunity case – but in a way that gives him a big win

- Today’s news briefs

- Judges accuse Pakistan army of coercing the courts

- The world wakes up to Sudan’s civil war

- A Franco-Malian star, and who should sing at the Olympics

- Sam Schultz: A heart for service on the US-Mexico border

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Pakistan is on the verge of doing something enormous

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

In the three years I covered Pakistan, one thing became clear: The military calls the shots. Sometimes, it has been a stabilizing influence. Often, it has simply meddled in politics and law to get what it wants.

Now, Pakistan’s judicial system appears to be fighting back. Hasan Ali’s story today points to what could, if it gathers momentum, become the single most important development since independence. Nuclear-armed Pakistan is a key Western ally and a nation of both tremendous potential and peril. Its bid for freedom from military control would ripple around the world.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

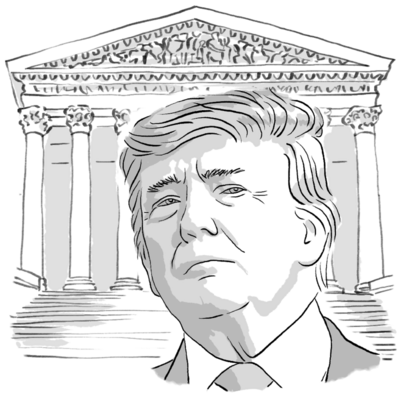

Trump looks likely to lose immunity case – but in a way that gives him a big win

Are presidents above the law? And what exactly constitutes an “official act”? The justices seem clear that the answer to the first question is no. But they appeared split on the second question in a case that explores how those in power are held to account.

Just how exceptional is the U.S. presidency? As the Department of Justice seeks to prosecute former President Donald Trump for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election, the Supreme Court Thursday weighed his claim that he has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts while he was in office.

Three years on from the Jan. 6 insurrection, the high court has begun wrestling with the legal fallout from Mr. Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of his 2020 defeat.

On Thursday, the court sounded skeptical of his claims of absolute immunity, but concerns about how it should rule instead augur a long, fractured final opinion that won’t arrive until near the end of the term. While it seems unlikely that Mr. Trump will prevail in this case, it does seem likely that he won’t stand trial before November’s election.

“If they do reject that broad theory of immunity, that is very important,” says Aziz Huq of the University of Chicago Law School. “But the way in which the court was talking about drawing the line was I think really troubling. The justices were just not attentive to the actual facts of the case in a quite astonishing way.”

Trump looks likely to lose immunity case – but in a way that gives him a big win

In the last case to be argued before the U.S. Supreme Court this term, the justices once again heard from former President Donald Trump, this time to consider a question that strikes at a foundational principle of American democracy.

Just how exceptional is the U.S. presidency? As the U.S. Department of Justice seeks to prosecute Mr. Trump for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election, the Supreme Court Thursday weighed his claim that he has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts while he was in office.

Three years on from the Jan. 6 insurrection, the high court has begun wrestling with the legal fallout from Mr. Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of his 2020 election defeat. There are clear implications for the presidential election this year, in which he is the front-runner for the Republican nomination.

In one case argued two months ago, justices quickly determined that Mr. Trump can’t be removed from state primary ballots. On Thursday, the court sounded skeptical of his claims of absolute immunity. However, concerns about how it should rule instead augur a long, fractured final opinion that won’t arrive until near the end of the term in June. While it seems unlikely that Mr. Trump will prevail in this case, it does seem likely that he won’t stand trial before the presidential election in November.

“If they do reject that broad theory of immunity, that is very important,” says Aziz Huq, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School. “But the way in which the court was talking about drawing the line was I think really troubling,” he adds. “The justices were just not attentive to the actual facts of the case in a quite astonishing way.”

Can presidents kill rivals? How about coups?

Thursday’s case concerns four criminal charges brought against Mr. Trump by Jack Smith, a special prosecutor for the Justice Department, related to the former president’s alleged conspiracy to overturn the 2020 election results.

Mr. Trump argues that he has absolute immunity from those charges. The Supreme Court has held that a former president is immune from civil liability over official acts, and he claims that immunity should be extended to criminal liability. Mr. Trump also claims absolute immunity, because a Senate impeachment trial on similar charges resulted in acquittal. (The vote was 57-43, less than the two-thirds needed to convict.)

The justices, particularly the court’s three liberal members, appeared skeptical that a former president should have blanket immunity from criminal prosecution.

“What you’re asking us to say [is] a president is entitled for total personal gain to use the trappings of his office ... without facing criminal liability,” said Justice Sonia Sotomayor to John Sauer, Mr. Trump’s lawyer.

Mr. Sauer agreed with a hypothetical, raised by Justice Sotomayor, that under his theory a former president could order the assassination of a political rival and be immune from prosecution. Justice Elena Kagan raised another hypothetical: What if a president ordered the military to stage a coup? Would that be an official act for which the president has immunity?

Mr. Sauer responded that other checks adopted by the Framers, such as guidelines prohibiting the military from following plainly unlawful acts, have “prevented that very kind of extreme hypothetical.”

“The Framers did not put an immunity clause into the Constitution,” replied Justice Kagan. “They knew how to give legislative immunity. They didn’t provide immunity to the president.”

“Wasn’t the whole point that the president was not a monarch and the president wasn’t supposed to be above the law?”

Several justices instead focused on what tests and boundaries the court should use to determine when a former president has immunity and when he doesn’t.

There seems to be “common ground,” said Justice Neil Gorsuch, that a president can be prosecuted for his private conduct after he leaves office. But “how [do we] segregate private from official conduct that may or may not enjoy some immunity?”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, meanwhile, suggested a former president could be immune from prosecution for acts related to “core” executive functions.

Here, a few of the court’s six conservative justices picked up on another of Mr. Trump’s claims: His warning that, if former presidents can be subject to criminal prosecution over official acts, it will have a devastating chilling effect on future presidents.

“If an incumbent who loses a close, hotly-contested election knows that [he] may be criminally prosecuted by a bitter political opponent, will that not lead us into a cycle that destabilizes the functioning of our country as a democracy?” asked Justice Samuel Alito.

Justice Sotomayor responded by calling her colleague out by name – a rare occurrence in the chamber.

“There is no fail-safe system of government. ... We fail routinely, but we succeed more often than not,” she said. “Justice Alito went through step by step all the mechanisms that could potentially fail. In the end, if it fails completely, it’s because we’ve destroyed our democracy on our own, isn’t it?”

“The case will not get tried before the election”

While all nine justices appeared to agree on the general principle that a former president doesn’t have absolute immunity from criminal prosecution, their comments seem to foreshadow a complex debate over how the case will be decided.

“You seem to worry about the president being chilled,” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson said to Mr. Sauer. “I think we would have a really significant opposite problem if the president wasn’t chilled.”

“I’m trying to understand what the disincentive is from turning the Oval Office into ... the seat of criminal activity in this country,” she added. “Wouldn’t there be a significant risk that future presidents would be emboldened to commit crimes with abandon while they’re in office?”

Later, she made the point that the case only requires the court to rule on whether Mr. Trump does have the blanket immunity from criminal prosecution that he claims.

“Even if we reject the absolute immunity theory, it’s not as though the president doesn’t have the opportunity to make [other immunity] arguments that arise,” she said. “We shouldn’t be trying to, in the abstract, set up those boundaries ahead of time as a function of sort of blanket immunity.”

However the Supreme Court rules, it’s unlikely to deliver the opinion quickly.

Even if the majority opinion limits its decision to the narrow question Justice Jackson described, if any justice wants to write a dissent then the opinion wouldn’t be released until the dissent is finished. The more likely scenario is that the justices will spend the next weeks and months debating what boundaries on presidential immunity the court should prescribe.

“The case will not get tried before the election,” said Mike Davis, a veteran Republican operative and founder of the Article III Project, in a statement.

Should Mr. Trump win that election, a Supreme Court ruling that allows for some degree of presidential immunity from criminal prosecution would prevent him from using the Justice Department to bring criminal charges against other former presidents.

That “is not a path we want to go down as a country,” he continued.

Some court watchers believe that the justices handed Mr. Trump a win just by agreeing to hear the case.

“Any delay to justice is at least temporarily providing immunity for him,” says Holly Brewer, a legal historian at the University of Maryland.

But that would avoid a worse outcome: a ruling “that creates a broad immunity for official acts.”

“Any new president coming in would feel like they have impunity for their actions,” she continues, “and that would be very scary.”

Today’s news briefs

• Weinstein conviction overturned: New York’s highest court overturns Harvey Weinstein’s 2020 rape conviction and orders a new trial.

• Haiti crisis: Ariel Henry resigns as prime minister of Haiti, paving the way for a new government to take power.

• Ukraine missile strikes: Ukraine has begun using long-range ballistic missiles, striking a Russian military airfield in Crimea and Russian troops in another occupied area, U.S. officials say.

• Arrests at pro-Palestinian protests: Arrests have been made in Massachusetts and California as universities have become quick to call in the police to end the demonstrations.

• Arizona election case: An Arizona grand jury has indicted former President Donald Trump’s chief of staff Mark Meadows, lawyer Rudy Giuliani, and 16 others in an election interference case related to the 2020 presidential vote.

Judges accuse Pakistan army of coercing the courts

At a pivotal moment for Pakistan, top justices are speaking out against military interference. Their courage – combined with a public still seething over what appeared to be brazenly rigged elections – could be a sign that the military’s grip is weakening.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Judges from the Islamabad High Court have penned an explosive letter alleging that Pakistan’s top spy agencies pressured them into giving decisions favorable to the country’s powerful military establishment.

Highlighting incidents of torture and abduction, the justices say they were forced to hear a case against former Prime Minister Imran Khan even after they had decided that it did not merit adjudication. Since the letter was published, the Supreme Court has initiated a case on the spy agencies’ judicial interference, and is expected to resume hearings later this month.

Pakistan’s army has historically relied on the courts to legitimize its intervention in the political sphere, including direct military takeovers and the toppling of governments that had fallen foul of the military high command. The current standoff also comes amid mounting evidence that Pakistan’s elections were rigged at the behest of the military establishment, and presents yet another challenge to the institution’s hegemonic influence.

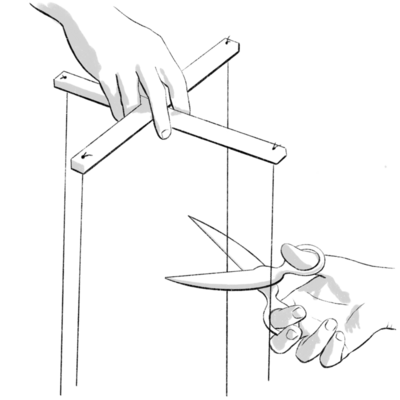

The letter “clearly lays out what we can call the ‘root of the root of the root’ of our issues,” says journalist Zebunnisa Burki, referring to the military’s political meddling. “It has turned whispers and closed-door discussions into an open complaint.”

Judges accuse Pakistan army of coercing the courts

Pakistan’s political crisis is deepening as the country’s powerful military establishment becomes embroiled in a tense standoff with the superior judiciary.

Last month, six of the Islamabad High Court’s eight justices wrote an explosive letter alleging that the country’s top spy agencies had used coercive tactics to pressure justices into giving favorable decisions. Highlighting incidents of torture and abduction at the hands of these agencies, the justices say they were forced to hear a case against former Prime Minister Imran Khan even after they had decided it did not meet the legal provisions necessary to merit adjudication.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan has since initiated a case concerning the matter, asking bar associations and high courts across the country to submit proposals to counter interference in judicial affairs. Chief Justice Qazi Faez Isa, who made his reputation as an opponent of the military’s extraconstitutional meddling, has promised to join the front line in defending the judiciary’s independence.

The Pakistan army has historically relied on the courts to legitimize its intervention in the political sphere. In the past, the courts have justified direct military takeovers and helped topple the governments of political leaders who had fallen foul of the military high command. Experts note that intelligence agencies also meddled in the judicial process when Mr. Khan was prime minister, before he fell out of favor with the military.

The current standoff comes amid mounting evidence that Pakistan’s elections were rigged at the behest of the military establishment, and presents yet another challenge to the institution’s hegemonic influence at a time when it needs a pliant judiciary to keep Mr. Khan behind bars.

“The Islamabad High Court judges’ letter is significant in how it clearly lays out what we can call the ‘root of the root of the root’ of our issues,” says journalist Zebunnisa Burki, referring to the military establishment’s political puppet mastering. “Is it unprecedented or surprising? Not as far as the content goes. ... But what the letter has done is that it has turned whispers and closed-door discussions into an open complaint.”

The signatories say that they and their families were targeted by operatives from the country’s premier intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence, after the court questioned the admissibility of the Tyrian White case. This case sought to disqualify Mr. Khan from holding public office on the grounds that he had concealed the existence of his daughter, whose mother he was not married to, from his election documents. “One of the judges had to be admitted in a hospital due to high blood pressure caused by stress,” said the letter.

They also alleged that surveillance equipment was found in the private lodgings of one serving justice, and that the relative of another was picked up and tortured. The justices wrote that it was imperative to “determine whether there exists a continuing policy on part of the executive branch of the state, implemented by intelligence operatives ... to intimidate judges, under threat of coercion or blackmail, to engineer judicial outcomes in politically consequential matters.”

No government or military leader has publicly addressed the claims made in the letter, though one intelligence official reportedly described them as “frivolous” and “out of context.”

According to Abdul Moiz Jaferii, a lawyer and political commentator, this document does not necessarily amount to an open rebellion. He points out that without a compliant judiciary, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz would not be leading the government today, since it came in second in the general election even with the support of the military via alleged vote-rigging. “The letter is more about the [military] establishment breaking the camel’s back by exerting more pressure than could be borne,” he says.

The judges’ defiance has nevertheless added to the pressure on the Pakistan army, whose reputation has suffered a great deal after the Feb. 8 election, when it was accused of manipulating the results to prevent candidates affiliated with Mr. Khan’s political party from forming the government.

A report released Tuesday by the Free and Fair Election Network further alleged that during by-elections held on April 21, poll-watchers were barred from observing the count in 19 polling stations. “The establishment has sought to get itself back on the front foot after many months of turbulence,” says Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute. “These allegations will galvanize those critics that have been accusing it of overreach.”

All eyes are now on the Supreme Court, which is expected to resume hearing the case on judicial interference at the end of this month. “Any wishy-washy middle ground position by the court, and we will be in more trouble than we started with,” says Mr. Jaferii.

But some argue that the judges’ defiance will have far-reaching consequences for the military, regardless of the case’s outcome. That is the view of Ms. Burki, the journalist, who says that the letter represents an indictment of the entire system.

“The genie cannot possibly be sealed back into the bottle once it has been typed out, printed, and now adjudicated, too,” she says. “The more things become public, the less fear there remains.”

Patterns

The world wakes up to Sudan’s civil war

After months of indifference, Washington and its allies are making a new bid to end Sudan’s civil war. The humanitarian costs and geopolitical risks are too high, as genocide threatens and Russia makes inroads.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Veteran U.S. diplomat Tom Perriello could not have sent a clearer message: This war must end, he said. “We need to be seeing massive convoys of aid” for the desperately vulnerable civilians.

He was talking not about Gaza but about the east African state of Sudan. A yearlong civil war there between two rival military leaders has been brutal, and the humanitarian crisis even more devastating than in Gaza.

After many months of policy drift, Washington and some of its allies are now trying again to bring that war to an end – partly because of its appalling humanitarian impact, and partly because of Sudan’s geopolitical import. It lies directly across the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia and Yemen, and the war has drawn in Russia and Iran, who are supplying one side with weaponry.

Washington has named a special envoy for Sudan, an international conference last month raised $2 billion in relief aid, and Saudi Arabia is planning to host peace negotiations next month. Both rival generals have been invited.

The worsening situation, especially the risk of another genocide in Darfur, seems to have persuaded the United States that it cannot afford to let Sudan remain a “forgotten war” any longer.

The world wakes up to Sudan’s civil war

The American diplomat could not have been clearer: This war must end, he said. “We need to be seeing massive convoys of aid” for its desperately vulnerable civilians.

He was not talking about Gaza.

Veteran U.S. diplomat Tom Perriello was addressing another conflict, 1,300 miles to the south, in the strategically important east African state of Sudan. That civil war, between two rival military leaders, has been brutal, and the humanitarian crisis even more devastating than in Gaza.

Yet it has been largely forgotten, overshadowed by the Israel-Hamas war and Ukraine’s fight against Russia’s invasion.

Until now.

After months of policy drift, Washington and a range of international allies are showing signs of trying again to end the year-old war in Sudan.

They know it won’t be easy. But they also know that the humanitarian cost of failure is rising. About half of Sudan’s 50 million people are in “dire need” of assistance, the United Nations says, including more than 14 million children. More than 9 million people have been forced to flee their homes.

And, ominously, the same forces that committed genocide in the Darfur region 20 years ago now seem poised to attack the North Darfur capital of Al-Fashir, after reportedly razing villages in the region. The U.S. State Department said Wednesday that it was “alarmed by indications of an imminent offensive” by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which has launched a campaign of abductions, sexual assaults, and mass killings.

And the geopolitical cost is rising, too, unsurprisingly, perhaps, given Sudan’s location. It sits directly across the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

Several outside powers – including Iran, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates – have reportedly been arming the warring forces.

Russia’s role is of special concern to the United States, since Moscow is also providing armed support to a string of military regimes stretching westward from Sudan across Africa to the Atlantic. And Washington is particularly frustrated about the UAE, a key American ally.

But the stakes are highest for the Sudanese, especially those involved in the grassroots protests in 2019 that forced an end to nearly three decades of military rule by President Omar al-Bashir.

Both the warring leaders – Sudanese armed forces commander Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo of the RSF paramilitary force – served under General Bashir.

The RSF is made up largely of former members of the Janjaweed militia, which carried out the earlier genocide in Darfur and is now unleashing similar violence against non-Arab civilians there.

Aided by Russia and the UAE, the RSF also seems to be gaining the upper hand in the war. Its militias have wrested increasing control not only over Darfur and central Sudan, but also in Sudan’s Nile-side capital, Khartoum.

In the wake of the 2019 protests, Washington, the U.N., and regional mediators saw both rival military commanders as indispensable to negotiations on a transition to civilian democratic government. And they appeared to have accepted that process, albeit reluctantly, until they effectively ended it last April and turned their guns on each other.

The U.S. and other would-be mediators have since intervened only haltingly. But that is beginning to change.

Amid rising bipartisan concern in the U.S. Congress over the RSF’s renewed campaign of violence in Darfur, and the country’s humanitarian emergency, the State Department appointed a special envoy for Sudan in February, Mr. Perriello.

He has sought to bring the weight of America’s diplomatic and economic influence to a fresh attempt to end the fighting, and to ramp up the response to the humanitarian crisis.

At a conference in Paris earlier this month, international donor nations finally made a start on answering long-standing U.N. appeals for a major infusion of relief funds. The meeting ended with pledges totaling around $2 billion.

Afterward, Mr. Perriello confirmed that Saudi Arabia was planning to hold a conference next month in the port city of Jeddah, which he hoped would attract both of Sudan’s warring generals, to make a renewed effort to negotiate an end to the fighting.

Such meetings last year, backed by the U.S., ended without success.

But Washington seems to be putting new urgency into its latest diplomatic effort.

U.S. officials have moved beyond backdoor appeals, publicly calling out both the UAE’s support for the RSF and Iran, which has reportedly provided drones to the Sudanese army.

After the meeting in Paris, Mr. Perriello said both countries were complicit in atrocities being committed against Sudan’s civilians. “Providing weapons to either side ... will deepen and prolong the conflict,” he added.

Washington clearly lacks the kind of leverage in Sudan that it enjoys with its Israeli and Arab allies. But the hope appears to be that it can persuade the UAE to step back, and press for a de-escalation with support from the Saudis and from major African states that are keen to see stability restored to the continent’s third-largest country.

And the worsening situation, especially in Darfur, seems to have persuaded the U.S. that it cannot afford to let Sudan remain a “forgotten war” any longer.

A Franco-Malian star, and who should sing at the Olympics

Who represents France? It’s a question that has set off a political brouhaha, as far-right leaders complain about the idea that an internationally popular Black artist might sing an Édith Piaf song at the Olympics.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When French President Emmanuel Macron was asked who might be tapped for a leading role in the opening ceremonies at the Paris Olympic Games, it was perhaps natural that he would suggest the most listened-to French singer on the planet: Aya Nakamura.

After all, Ms. Nakamura has much in common with the woman whose songs she would likely end up singing, Édith Piaf. Both are the children of immigrants, grew up in poverty, but nonetheless became internationally acclaimed stars singing in French. But some people complain about Ms. Nakamura’s habit of salting her songs with slang from her native Mali, and with her own invented words.

Ms. Nakamura’s linguistic choices have spurred critique from the far right. Marine Le Pen said on French radio shortly after Mr. Macron’s endorsement that not only did the artist dress and act in a vulgar fashion, but that she didn’t sing in French. “It’s nonsense,” said Ms. Le Pen.

But for some fans, Ms. Nakamura’s ability to relate to them comes down, precisely, to the way she uses language.

“All this talk about grammar and the French language is an excuse for what is more of a political problem,” says Roxane Sebbagh, “the idea that a Black woman from the suburbs could possibly represent France.”

A Franco-Malian star, and who should sing at the Olympics

One of the most important roles at the opening ceremony at the Paris Olympic Games this summer is likely to be performing the songs of Édith Piaf. So when President Emmanuel Macron was asked who might be tapped for such a duty, it was perhaps natural that he would suggest the most listened-to French singer on the planet: Aya Nakamura.

But the thought of Ms. Nakamura, a pop and rap artist known for salting her lyrics with slang influenced by her native Mali and of her own invention, performing the work of the beloved Ms. Piaf did not sit well with everyone. Far-right leaders called Mr. Macron’s endorsement a “provocation,” complaining that she didn’t sing in French nor represent France.

But while Ms. Nakamura may not embody the beret-wearing, baguette-carrying France of the past, many say she is the face of the country today.

France is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Europe, and Ms. Nakamura represents several facets of the “new” France. As a Black single mother who grew up in the social housing projects of Aulnay-sous-Bois outside Paris, and is now idolized by fans around the world, she reflects a different sort of French experience – one that is growing more familiar to and common among the French citizenry.

“Aya Nakamura’s music symbolizes femininity, youth, what it means to be Black and working class,” says Gabriel Segré, a socio-anthropology professor at Paris Nanterre University who studies music and fan culture. “Her ability to ‘rise up from the bottom’ reverses the traditional codes of success and legitimacy in society. The French elite are having a fit about it.”

A different sort of French star

Born Aya Danioko in Bamako, Mali, Ms. Nakamura moved with her large family to France as a child, settling into La Rose des Vents, a huge public housing project built in the 1960s in Aulnay-sous-Bois. In 2014, at age 19, she quit high school to begin her singing career, adopting the stage name “Nakamura” from a character in the U.S. TV show “Heroes.”

In 2018, she released “Djadja,” which featured her now trademark invented, African-influenced slang – including the title, a word she said means “liar.” The song became an instant hit and catapulted her to nationwide success.

Since then, Ms. Nakamura has accumulated five No. 1 songs and a double-platinum album, “Aya,” in France. In July 2021, her album “Nakamura” surpassed 1 billion streams on Spotify. She is now the most listened-to French-speaking artist in the world.

Her style has vibrant, diverse roots.

“Nakamura gets her inspiration from various sources, from zouk to R&B,” says Marie Sonnette-Manouguian, a hip-hop expert at the University of Angers. “She uses rich and everyday language, playing with onomatopoeia and rhythm, to create an original lexicon that is easily picked up by her fans. It’s one of the factors in her success.”

But her linguistic choices have spurred critique from the far right. The National Rally party’s Marine Le Pen said on French radio that not only did the artist dress and act in a vulgar fashion, but she didn’t sing in French. “She doesn’t sing in a foreign language and it’s not a blended language either,” said Ms. Le Pen. “It’s nonsense.”

But it is precisely Ms. Nakamura’s use of language that enables her to relate to her fans, especially the young people with whom she is particularly popular.

“Aya uses slang and expressions ... and I sing along with her,” says Roxane Sebbagh, a Franco-Algerian resident of Aulnay-sous-Bois. “All this talk about grammar and the French language is an excuse for what is more of a political problem: the idea that a Black woman from the suburbs could possibly represent France.”

“Édith Piaf of her time”

But Ms. Nakamura does represent France, albeit a different sort of France from the one typically in the limelight.

Though the French authorities prohibit the collection of data about citizens’ race or ethnicity, studies put the Black population at around 4%. Ms. Nakamura, having spent most of her life in France, is also part of the immigrant community, which numbered about 7 million people, or around 10% of the population, in 2022 according to official figures.

Her status as a single mother is also representative of a significant portion of the public: 25% of families are single-parent and the vast majority of those parents are women. And the economic conditions in which she grew up in La Rose des Vents – deemed by the local government to be a “priority zone” suffering from inequality, economic, and social difficulties – are shared by 5 million French people today.

While some of her critics may take umbrage at a person from such a background taking on the task of honoring Édith Piaf at the Olympics, Piaf herself came from a similar background, as the child of immigrants who spent most of her youth in poverty. In a way, says Dr. Sonnette-Manouguian, that makes Ms. Nakamura a natural to sing Piaf’s songs.

“Aya Nakamura’s audience is a varied audience,” she says. “It is also a large audience.” Ms. Nakamura would be a “rational choice” to sing at the Olympics opening, she argues, because she is “not only the first woman to appear in the ‘top artist’ 2023 list but she is also the French woman most listened to abroad, the Edith Piaf of her time.”

Ms. Nakamura is not universally beloved in France’s minority communities. “Aya doesn’t represent France or me, she represents vulgarity,” says Vanessa O, who grew up in the Paris suburb of Gif-sur-Yvette in a first-generation West African family. “What kind of example is she setting for our young people? That you can not finish school, not speak correctly and still get ahead?”

But for many of Ms. Nakamura’s fans, it is the way she overcame challenges that makes her a role model. A recent study by a group of Black organizations found that nine out of 10 Black people in France experienced racial discrimination “often.”

“What I appreciate about Aya Nakamura is her determination and capacity to succeed despite the obstacles she had to face in her life,” says Sergio Ciccano, a diversity and inclusion consultant. “I think she’s an excellent representation of France for an international audience because she incarnates the diversity and dynamism of our country.”

With the Olympic Games three months away, nothing has yet been decided about who will open or close the event. A handful of artists are in the running and Mr. Macron has said he will leave the final decision to the ceremonies’ artistic director.

But for those who love Ms. Nakamura, the choice is obvious.

“When Aya’s music is playing, everyone gets up to dance,” says Ms. Sebbagh. “That’s what we need at the Olympics: someone who can get people on their feet, having fun and coming together.”

Sam Schultz: A heart for service on the US-Mexico border

“Giving liberates the soul of the giver,’’ said poet Maya Angelou. Sam Schultz, an aid worker who helps disaster victims, lives this message. Why the border crisis moved him from retirement to help those in need.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For the past year, Sam Schultz has been at the center of America’s fraught border situation. His tiny town of Jacumba Hot Springs is divided over his humanitarian work – some supporting it, others seeing it as aiding illegal immigration, and some staying out of it.

Squalid camp conditions spurred a lawsuit in February, with advocacy groups demanding better care for minors at camps, including Jacumba.

But Mr. Schultz, a Quaker, says he doesn’t care about immigration politics or policy, an outlook stemming from his pacifist roots and years working in Indonesia. The Monitor first met Mr. Schultz there as he delivered aid following a 2004 tsunami that killed some 230,000 people.

Mr. Schultz found a boat and a crew, then paid out of pocket for delivery runs of doctors, nurses, tools, and rice. He built 14 fishing boats to help villagers resume their livelihoods.

Recently, the Border Patrol stopped directing migrants to Mr. Schultz’s aid camp, taking them instead into detention after crossing the border. But that didn’t last long.

This past Monday, some 400 migrants passed through the camp.

“It’s been a really long day,” he says in a phone update. “It’s a confusing time.”

Sam Schultz: A heart for service on the US-Mexico border

A year ago, Sam Schultz was enjoying retirement in this remote, high-desert community that hugs California’s border with Mexico.

He, his wife, Gabrielle, and their two adult sons, nine dogs, multiple cats, chickens, and peacocks live on a compound that includes a 1923 landmark stone monument, the Desert View Tower. Mr. Schultz, a skilled carpenter, likes fixing stuff on the property, where he helps his brother, who also lives there, run the tower as a funky Airbnb with a stunning mountain vista.

But then migrants poured through gaps in the border barrier, just down from the compound. The human stream surged last May, ebbed, and then flowed into a river starting in September, churning up national headlines.

Mr. Schultz, known as a can-do relief worker, sprang into action. He organized volunteers to set up tents in three open-air encampments. His team supplied food, water, firewood, and multilingual information sheets as hundreds of migrants, including children, waited days for the overwhelmed Border Patrol to pick them up and process them. A GoFundMe page helped. So did a legal services group, Al Otro Lado, which pitched in with workers and equipment.

“I cooked for 450-plus a day, 60 days straight,” says Mr. Schultz, his wispy, white ponytail sticking out from a gray field cap. “The Red Cross isn’t going to come. I’m living next door.”

Quaker roots fuel acts of service

For the past year, this retiree has been at the center of America’s fraught border situation, which changes daily. The tiny town of Jacumba Hot Springs is divided over his humanitarian work – some supporting it, others seeing it as aiding and abetting illegal immigration, and some wanting to stay out of the debate.

Squalid camp conditions spurred a lawsuit in February, with advocacy groups demanding enforcement of the Flores agreement, which sets standards for treatment of children in immigration custody. On April 3, a federal judge in San Diego ordered the federal government to move “expeditiously” to safely house minors entering the country unlawfully.

Mr. Schultz, a Quaker, says he doesn’t care about immigration politics or policy. “I’m just helping people.” It’s an outlook stemming from his religious, pacifist roots and his childhood in San Diego followed by years on Bali in Indonesia.

On Bali, he earned a living as a contractor building luxury villas and hotels. That supported his young family – and his parallel life as a humanitarian relief worker. In that life, he organized aid deliveries to the beaches of East Timor during the violent crisis of 1999; assisted in the overloaded morgue during the 2002 Bali terrorist bombings; and set up triage stations after an 8.5 earthquake flattened a Jakarta hospital in 2007.

The Monitor first met Mr. Schultz shortly after a 2004 tsunami killed nearly 230,000 people, many in Indonesia. It was the deadliest disaster of the 21st century so far. Reporter Daniel B. Wood rode with this “regular guy” as he helmed a cargo boat loaded with supplies for those impacted by the tsunami on Sumatra’s denuded coast.

Mr. Schultz saw the news on TV and didn’t wait around for “the clipboard men” at giant aid organizations to get underway. Instead, he found a boat and a crew, then used his own money to help fund his delivery runs of doctors, nurses, tools, cook pots, and rice. He also built 14 fishing boats to help villagers resume their livelihoods.

“The Quakers’ real name is Society of Friends,” he told the Monitor reporter 20 years ago, “and we treat everyone we deal with as if they are our friend. My friends are in trouble. That’s it.”

This is Moon Camp

It’s the first week in April, and not sun, but snow is forecast for Jacumba. Mr. Schultz, his son John, and two young volunteers are pulling a tarp over the skeleton of a large tent structure. This seasoned aid leader lugs sandbags to help secure the sides of the tent. “In relief work, you lift a lot of heavy stuff,” he remarks.

This is Moon Camp, at the base of rugged mountains on old Highway 80. It’s a desolate, open stretch of hard dirt where temperatures can fluctuate wildly and winds whip. The camp includes four portable toilets, a water tank, and an industrial-sized dumpster.

Migrants leave trash strewn about – transit documents, itineraries listing hotels and car rentals, clothes, empty water bottles. The detritus is global: a Russian pouch of dry milk, good for infants ages 6 to 12 months; a Chinese towelette; Mexican pesos. But the relief workers run a clean camp, filling countless trash bags and tossing dirty blankets into the dumpster. The good ones they spray with disinfectant for reuse.

In the middle of the camp is parked Mr. Schultz’s Ford F-150 Lightning pickup truck. The bed of the all-electric vehicle is loaded with bottles of water and lunch bags. Each contains a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and an orange. In recent weeks, about 100 to 200 migrants have arrived each day – about half from South America and the rest a mix of Turks, Africans, Indians, Chinese, and others, says Mr. Schultz.

Not far from the camp, down a dirt track, the steel-slat border wall abruptly ends at huge boulders – the base of a steep, mountainous area. Migrants cross over a mountain, descending on a trail in large groups. Border Patrol agents direct them to Moon Camp. After migrants eat their sandwiches, the Border Patrol separates the parents and children from the rest, and takes them to a facility for fingerprinting, background checks, a medical screening, food, and questioning.

A group of about 50 men, women, and children from countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and El Salvador, wear hoodies, jeans, and running shoes as well as looks of fatigue – and elation. “Woo-hoo,” yells one young man, on learning he is in the United States. “Gracias,” says another, hands pressed together in thanks. “I’m very tired,” says one woman, holding the hand of her husband.

Back in town at the library, Mitch, a resident who did not want his last name used, expresses frustration with illegal immigration under the Biden administration. He is also unhappy with Mr. Schultz’s relief work. “It’s a magnet.”

But the Schultz family isn’t buying it. “Like somehow people in China heard about our world-class PB&Js, and they’re like, ‘Yeah, that’s the reason we gotta come to the United States,’” says the younger Schultz, as he rakes out a tent floor.

Constant change on the border

Things can change quickly on the border. After an avalanche of media coverage and a trip by Secretary of State Antony Blinken to Mexico in late December, Mexico pitched its own tent camps and put guards on the opposite side of the fence from two camps that Mr. Schultz organized. The Mexicans’ gleaming white tents stand unoccupied; a gap in the border fence, unused. If migrants show up, the Mexicans will deport them further south.

That change eased things considerably for Mr. Schultz, his son, and his wife, who helps out. When the Monitor visited earlier this month, only the Moon Camp was operating. But migrants are still coming, says Mr. Schultz. They are being pushed west to a dangerous area in the Otay Mountain Wilderness – too far for the Schultz family to go. He says that volunteers who helped in Jacumba have since gone to San Diego to help orient migrants after the Border Patrol has processed them and dropped them at a public transit station.

After the April 3 ruling, the Border Patrol stopped directing migrants to Moon Camp, taking them into detention as soon as they walk down the mountain trail. That lasted about a week.

The migrant stream is again surging, and this past Monday, about 400 migrants passed through the camp. Some were facing their third night there, waiting for agents to pick them up. The water tank supplied by the Border Patrol was dry, prompting fights as Mr. Schultz scrambled to find more water – and slap together more PB&J sandwiches.

“It’s been a really long day,” he says in a phone update. “It’s a confusing time.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Opportunity knocks in Central Asia

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A historical term in geopolitics – the Great Game, or when big powers fought to control the heartland of the Eurasian supercontinent – may need to be retired. Over the past two years, many countries in Central Asia and the Caspian basin have seen a flurry of investments and friendly diplomacy from around the world, reflecting the region’s emboldened streak of independence from foreign intervention.

The latest example is an April 22 summit between Russia and Azerbaijan. The focus was mainly economic. That was in sharp contrast to news just days earlier when Russia, weakened by its war in Ukraine, started the withdrawal of some 2,000 peacekeeping soldiers from the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan.

“For the first time in 200 years, there will be no foreign soldiers or bases on Azerbaijani soil,” declared the Azeri news site Yeni Müsavat.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, along with the American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and Iran’s domestic troubles, has helped much of Central Asia to focus on trade and investment.

“The region, previously the theater of the Great Game in the confrontation of superpowers, is now trying to become an opportunity zone,” states a new report by the TALAP Center for Applied Research, a think tank in Kazakhstan.

Opportunity knocks in Central Asia

A historical term in geopolitics – the Great Game, or when big powers fought to control the heartland of the Eurasian supercontinent – may need to be retired. Over the past two years, many countries in Central Asia and the Caspian basin have seen a flurry of investments and friendly diplomacy from around the world, reflecting the region’s emboldened streak of independence from foreign intervention.

The latest example is an April 22 summit between Russia and Azerbaijan. The focus was mainly economic – how to finish building a road-and-rail corridor across Eurasia, one of several transportation projects in the region. That was in sharp contrast to news just days earlier when Russia, weakened by its war in Ukraine, started the withdrawal of some 2,000 peacekeeping soldiers from the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, a remnant of Moscow’s previous clout.

“For the first time in 200 years, there will be no foreign soldiers or bases on Azerbaijani soil,” declared the Azeri news site Yeni Müsavat.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, along with the American withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 and Iran’s domestic troubles, has helped much of Central Asia to focus on trade and investment.

“The region, previously the theater of the Great Game in the confrontation of superpowers, is now trying to become an opportunity zone,” states a new report by the TALAP Center for Applied Research, a think tank in Kazakhstan.

“These states have skillfully maneuvered the changing political landscape, adhering to a balanced foreign policy,” the report adds.

China recently eclipsed Russia as the region’s largest trade partner, while trade with Europe and the United States is rising. Last year, President Joe Biden held a summit with the leaders of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Yet with their eye on luring foreign investors, these authoritarian-minded states are also being reminded to move toward democratic rights and freedoms. They must strengthen the rule of law, enforce fair and transparent competition, and ensure independence of the judicial system, the TALAP Center report recommends.

Perhaps the most notable reforms have been in Kazakhstan, the region’s largest country. Mass protests starting in 2018 led to the ouster of a longtime ruler and brought in a new president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. He has distanced the country from Russia, raised the status of a human rights ombudsperson, and beefed up protections for women and children from domestic violence.

The spirit of the shift in the region was reflected in a commentary in Azerbaijan by the Minval news website on the day of the April 22 summit in Moscow: “Our country will not play the role of someone else’s bridgehead or outpost – no matter for whom or against whom.”

Great Game over.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Being a sheep, not a shepherd

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Larissa Snorek

In embracing a humble reliance on God as our Shepherd, we find comfort, strength, and a clear way forward.

Being a sheep, not a shepherd

Sheep often get a bad rap. Being a sheep normally connotes blindly following, being timid or weak, or generally not thinking for oneself.

But what if being sheep-like instead meant being meek, innocent, receptive to Truth, God? And what if expressing these qualities was actually the way to go in life – was how to live so as to bring healing to our and others’ lives?

King David’s well-known 23rd Psalm makes a case for this. Referring to God as our Shepherd, he wrote that we cannot be in want. We will be led to green pastures and beside still waters (to satisfy hunger and thirst) and comforted in the valley of the shadow (which can be dangerous for sheep), and goodness and mercy will follow us all our days.

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, illustrates this relationship to God as our Shepherd in her poem “‘Feed my sheep’”:

Shepherd, show me how to go

O’er the hillside steep,

How to gather, how to sow, –

How to feed Thy sheep;

I will listen for Thy voice,

Lest my footsteps stray;

I will follow and rejoice

All the rugged way.

(“Poems,” p. 14)

This poem expresses a yearning to know not where to go or with whom, but how. And the 23rd Psalm gives an answer: with stillness. When the human mind is quieted, divine direction is clearly heard. That’s because the comforting voice of the Shepherd is always speaking to us, but we don’t always hear it amidst the rumination in our thought. The goodness that results from letting ourselves be shepherded in this way breaks through any urgency of the human condition and calms anger, agitation, worry, or concern.

To follow God as Shepherd is to accept our own true nature – by listening and trusting God’s direction and seeking God’s guidance in all we do. As Mrs. Eddy states in “The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany”: “Remember, thou canst be brought into no condition, be it ever so severe, where Love has not been before thee and where its tender lesson is not awaiting thee. Therefore despair not nor murmur, for that which seeketh to save, to heal, and to deliver, will guide thee, if thou seekest this guidance” (pp. 149-150).

Seeking God’s guidance feeds a deep hunger for the things of Spirit. This puts off self-centeredness and enables us to discern the truth of being. Thought increasingly comes to rest in the substance and safety of spiritual understanding, ceasing rumination based on human analysis.

To progress in healing, spiritual understanding is required. A study of Christian Science moves thought from a material sense of things to the spiritual. When thought is anchored in God’s goodness, change happens. We yield any sense of personal goodness – whether as a burden or as self-satisfaction in thinking of ourselves as our own source of guidance and accomplishment – to the knowledge that man is God’s spiritual likeness.

Steadfastly beholding Truth in thought eliminates the belief that we are vulnerable mortals. Awareness of the substance of infinite Spirit continually ushers us into the house, or consciousness, of divine Love, God, where we dwell forever and move at the impulse of Love rather than human outlines.

Christ Jesus maintained this awareness of following God as the Shepherd. He made the spiritual fact of man’s unbreakable relation to God evident. His words and deeds sprang from the activity of the Christ, the true idea of God and man, which animated him and directed all his steps.

As we cherish the spiritual idea, the reality of God’s all-power and man’s natural and irrepressible receptivity to divine power, we proportionally lose fear and any sense of burden. To trust God’s shepherding is to relinquish a need to control outcomes and circumstances. We cannot consider ourselves in charge and also yield to divine guidance. We aren’t co-shepherds – we are the sheep!

Sheep represent meekness, gentleness, and obedience, and they find strength and comfort in the shepherd and the fold. To be a sheep is to follow the Shepherd, God – to reflect the divine activity that does not tire, the affection that is never absent or insufficient, and to relish the community of others striving to do the same. Christian Science transforms thought, revealing through spiritual truth the man and universe of God’s creating. In this holy fold, divine Love cares for its own, through each “rugged way.”

Originally published as an editorial in the Feb. 27, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Inspired to think and pray further about fostering trust around the globe? To explore how people worldwide are navigating times of mistrust and learning to build trust in each other, check out the Monitor’s “Rebuilding trust” project.

Viewfinder

The flowering of democracy

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for a gripping story from the French community where a teacher was beheaded for showing a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad. We look at how all sides – but especially teachers – have struggled to reestablish a sense of trust in the aftermath of the tragedy. It has led to deep introspection and honest conversations.