- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why military ‘drone swarms’ raise ethical concerns in future wars

- Today’s news briefs

- Hostage’s family: ‘Our country did not save him’

- How one NPR station is trying to win conservative listeners

- In Congo, embroidery artist stitches an archive of war

- Hot crabs and cold lemonade: A window into my Cajun childhood

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

An honest answer to despair

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Every once in a while, this is the perfect place to share something.

Just last week in this column, I pondered the depth of despair in Gaza and what that does to hope. Today, Australian musician Nick Cave offers an answer – not for Gaza, specifically. But Mr. Cave lost two of his sons in tragic circumstances. He has seen the darkness.

This video is his response. It is only two minutes long. You will be glad you clicked on it.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why military ‘drone swarms’ raise ethical concerns in future wars

Artificial intelligence-powered drone technology could eventually change warfare. But the autonomy of lethal machines raises serious ethical dilemmas around how, and whether, to regulate development, deployment, and use of AI.

-

Laurent Belsie Staff writer

As researchers apply artificial intelligence and autonomy to lethal aerial machines, their systems pose new questions about how much humans will remain in control of modern combat.

Intelligent “drone swarms” would represent a breakthrough in warfare. Rather than soldiers piloting individual uncrewed vehicles, they could deploy air and seaborne swarms to cooperate on missions “with limited need for human attention and control,” according to a recent U.S. government report.

The question going forward is whether the Pentagon can overcome the many technological challenges of drone warfare while also maintaining the ethics of a democratic state. There are fears that adversaries may exploit their own swarm technology in future conflicts, without ethical constraints.

How much human oversight is necessary or desirable is a key question. Humans, after all, don’t process information as quickly as machines, which may increase pressure to take humans out of the loop in order to stay competitive in battle.

“We need more people thinking about them in the context of the military, in the context of international law, in the context of ethics,” says Margaret E. Kosal, a former science and technology adviser at the Defense Department.

Why military ‘drone swarms’ raise ethical concerns in future wars

The proliferation of cheap drones in conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East has sparked a scramble to perfect uncrewed vehicles that can plan and work together on the battlefield.

These next-generation, intelligent “swarms” would represent a breakthrough in warfare. Rather than soldiers piloting individual uncrewed vehicles, they could deploy air and seaborne swarms on missions “with limited need for human attention and control,” according to a recent U.S. government report. It’s the “holy grail” for the military, says Samuel Bendett, an adviser to the Center for Naval Analysis, a federally funded research and development center.

It’s also an ethical minefield. As researchers apply artificial intelligence and autonomy to lethal machines, their systems raise the specter of drone armies and pose new questions about the role human control should play in modern combat. And while Pentagon officials have long promised that humans will always be “in the loop” when it comes to decisions to kill, the Defense Department last year updated its guidance to address AI autonomy in weapons.

“It’s a very high level of approval to even proceed with testing of a fully autonomous weapons system,” says Duane T. Davis, a senior lecturer in the computer science department at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. But it does “provide for the possibility of completely autonomous weapons systems.”

That’s largely because much U.S. military research is driven by fears of how adversaries may exploit their own swarm technology in a future conflict with the United States or its allies. The question going forward is whether the Pentagon can overcome the myriad technological challenges of drone warfare while also maintaining the ethics of a democratic state.

The concern is that China “is not going to wrestle with these same ethical decisions in the way that we will,” says Dr. Davis.

What makes a swarm

Current instances of uncrewed military group attacks over battlefields – as well as the drone light shows now popping up as entertainment in night skies over the U.S. – are not intelligent swarms. The former are essentially salvos of slow-moving aerial “missiles,” each one operated by a human, with no machine-to-machine coordination or communication. The latter – a high-tech alternative to fireworks – are preprogrammed displays in near-ideal conditions, which aren’t particularly useful in a military setting, since an adversary can figure out how to counter them.

“For an enemy, that just means I’ve got a pattern of things I can shoot at, or they’re operating similarly, so it’s easier to predict what they’re going to do,” notes Bryan Clark, senior fellow at Hudson Institute.

Swarms instead use an array of sensors to communicate drone to drone – and then switch to AI to plan and collaborate for attacks on the fly. They’re programmed to create a siege of overwhelming force from “a bunch of different angles – the way ants crawl all over a beetle, or whatever, to eat it,” says Zachary Kallenborn, a fellow at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government.

A big challenge for current drone operators on Ukraine’s battlefields is Russian jamming technology, which can prevent operator-drone and, thus, drone-to-drone communication. To address this challenge, some researchers are working on ways for drones to observe and infer what other drones are doing.

The fog of war complicates visual observation. That’s why Theodore Pavlic of Arizona State University recently began studying weaver ants in Australia at the behest of U.S. Special Operations Command. As the ants swarm and transport their prey up trees, they sense each other’s presence without constantly looking around.

They also cooperate and make decisions as a team. “If we can replicate that [with drones], you can basically hit go, and they will plan their own way,” says Dr. Pavlic, who also studies stingless bees and other types of ants. “If new challenges occur, then they can [set] temporary short-term goals to get around those challenges.”

Bang for the buck

Building smart drones, with more onboard intelligence and computing power, means bigger and more expensive machines, and that has a downside. “Computers can only be so small, and you can only put so much power and payload onto a drone,” says Nisar Ahmed, director of the Research and Engineering Center for Unmanned Vehicles at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Just for a drone to take off, for starters, requires roughly 10 times the energy that a world-class sprinter expends to run a 100-meter race, says Vijay Kumar, dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s engineering school. The result: Missions with aerial drones are currently limited in terms of distance and time. Since longer-range drones are expensive, cheaper drones that can stay aloft for an hour – or even 30 minutes – offer more bang for the buck.

Despite the challenges, researchers are making progress. Red Cat Holdings, a drone technology company in Puerto Rico, announced last year a system in which one person could operate four of its Teal drones, as opposed to today’s 1-1 ratio. The company aims to increase that ratio by pushing even more autonomy onto the machines themselves.

Embedding such autonomy in lethal machines, however, also poses ethical challenges about maintaining human oversight – particularly as the speed and complexity of drone decision-making increases. Humans, after all, don’t process information as quickly as machines, which may increase pressure to take humans out of the loop if, say, China or another adversary deploys AI-equipped drones capable of full autonomy.

The Pentagon hired an ethics officer in 2020 to grapple with precisely such challenges. Still, “We need more people thinking about them in the context of the military, in the context of international law, in the context of ethics,” says Margaret E. Kosal, a professor at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at the Georgia Institute of Technology and former science and technology adviser at the Defense Department.

A machine gun analogy

What is clear is that the technology will continue to develop at breakneck speed, even as researchers wrestle with challenges specific to the battlefield of the day. Drones will change war the way the machine gun did more than a century ago, says George Matus, chief technology officer of Red Cat and founder of its Teal subsidiary.

“Back then, a handful of gunners could defeat large numbers of even the mightiest cavalry. [Sometimes, even] today, a handful of drones can defeat a battalion of the mightiest armored vehicles before they even reach the front line.” In the future, intelligent swarms will prove even more effective, he adds.

While many researchers worry the technology is one more step toward all-out swarm warfare, Mr. Matus embraces the vision.

“The front line is going to become majority automated, if not fully automated,” he says. “There’s no doubt in my mind at least for the next couple of decades, this is going to be a very large part of the future of war.”

Others see it as an evolutionary step with more limited battlefield applications. “It is not fundamentally going to be a revolution in military affairs,” says Dr. Kosal. “That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried.”

Today’s news briefs

• Abortion rights: Voters in at least nine states will decide in November whether they want to enshrine abortion rights in their state constitutions.

• Mexico protests: Protesters have marched across Mexico in the latest opposition to Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s proposed judicial overhaul and other moves critics say will weaken democratic checks and balances.

• Grocery store merger: The largest proposed grocery merger in U.S. history is heading to court. On one side are supermarket chains Kroger and Albertsons, on the other are antitrust regulators from the Federal Trade Commission.

• Trump documents case: Special counsel Jack Smith has asked a federal appeals court to reinstate the classified documents case against former President Donald Trump after it was dismissed by a judge last month.

Hostage’s family: ‘Our country did not save him’

For months, every Saturday night, the families of hostages held in Gaza have gathered to demand that Israel secure their loved ones’ release. Last week, six bodies were recovered, fueling the families’ sense that they’ve been abandoned by the government.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Shoshanna Solomon Contributor

On Oct. 7, Hamas took the 79-year-old Abraham Munder hostage from his home on Kibbutz Nir Oz. Last week, the Israeli army retrieved his body from a tunnel in Gaza, along with the bodies of five others.

Addressing the weekly rally of hostages’ families and supporters in Tel Aviv Saturday night, Eyal Mor, Mr. Munder’s nephew, said the hostages had been abandoned. “The same state leadership that failed to protect them in their homes ... neglected them repeatedly, stubbornly missing every opportunity to bring them back in a deal.”

“What is frustrating, very frustrating, to us is the fact that, according to the army, he was still alive in March,” Mr. Mor tells the Monitor. “This means he had survived for five months, in all the terrible conditions.”

His family draws strength, he says, from the other hostages’ families. “We are ... in the same boat ... and we believe that together we have force,” he says. “We are angry because for five months we could have saved him, and our country did not save him.”

Yet he says that he and the rest of the Munder family will continue to go to the demonstrations and support the remaining hostages. “We have created a family. We continue to fight.”

Hostage’s family: ‘Our country did not save him’

Just days after the Israeli army extracted the bodies of six hostages from a Hamas tunnel in Gaza and brought them home for burial, the feelings of frustration and anger were palpable at the weekly rally of hostage families in Tel Aviv Saturday night.

Cries for the government to strike a deal to save the remaining hostages still alive seemed louder. The words “abandoned” and “betrayal” abounded, as did calls for the replacement of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has failed his people and the hostages, said the speakers addressing the restless gathering.

After 10 1/2 months of war, more than 100 hostages are still in Gaza, many of them already known to be dead. As a result, despair has given way to anger at the Hostages Square demonstrations in Tel Aviv.

“The same state leadership that failed to protect them in their homes [on Oct. 7] ... neglected them repeatedly, stubbornly missing every opportunity to bring them back in a deal,” Eyal Mor, the nephew of deceased hostage Abraham Munder, told the crowd.

Hamas militants took Mr. Munder hostage from Kibbutz Nir Oz, near the Gaza border. His body was retrieved last week in an overnight Israel Defense Forces (IDF) operation from a tunnel in Khan Yunis, along with the bodies of five others: Alex Dancyg, Chaim Peri, Yagev Buchshtab, Yoram Metzger, and Nadav Popplewell.

According to released hostages’ testimonies and a Hamas video, they were all alive when taken captive. Autopsy results released by Israel indicated that all six were shot while in Hamas captivity.

“We’ll never know what went through the minds of Chaim, Alex, Yoram, Nadav, Yagev, and Abraham during those months of physical and mental torture, but I believe any guess containing the words ‘abandonment’ or ‘betrayal’ would hit the mark,” Mr. Mor told the square thronged with people.

“All the hostages whose bodies were recovered this week could all have been saved alive,” said Gil Dickmann, cousin of Carmel Gat, who is still a hostage.

Family’s frustration

In an interview with the Monitor on the sidelines of the rally, Mr. Mor recounts his family’s emotional ordeal.

“What is frustrating, very frustrating, to us is the fact that, according to the army, he was still alive in March,” he says. “This means he had survived for five months, in all the terrible conditions.

“He was nearly 80. ... He was not a healthy person to begin with when he was kidnapped, but still, with these terrible conditions of no fresh air and no sunlight and disconnection from the external world and little food, little water ... still [he] survived for five months.”

Mr. Munder was kidnapped from his kibbutz home along with his wife, Ruth; his daughter, Keren; and his grandson, Ohad, then 8 years old. Keren and Ohad were visiting from Kfar Saba, in central Israel, to celebrate the Jewish festival of Simchat Torah together with the elder Munders and Roy Munder, Keren’s brother, who also lived on Nir Oz.

When the rocket alarms sounded early that morning, the elder Munders, Keren, and Ohad made their way to their home’s safe room. Soon they heard gunshots and shouts in Arabic, and then noise of destruction and shouting within their home.

Mr. Munder, who used a cane, quickly rose from his chair and seized the handle of the safe room’s door, in a desperate effort to stop the intruders.

“Keren said she saw her 79-year-old ... physically weak father fighting for the door handle, when the terrorists tried to open it,” recounts Mr. Mor. “He was fighting, fighting for the life of his family.”

When the attackers prevailed, they knocked Mr. Munder onto his knees, and rounded up and kidnapped his wife, daughter, and grandson. Mr. Munder was hauled into Gaza separately about half an hour later, by motorbike, Mr. Mor says.

Meanwhile, Roy was killed 500 yards from his parents’ home, in the yard in front of his burning house. About a quarter of the community’s 400 residents were killed or taken hostage Oct. 7.

“Our hope ... collapsed”

In November, Ruth, Keren, and Ohad were released in a prisoner exchange. While in Gaza, they heard on the radio that Roy had been killed. Only upon their release did they learn that Abraham was still alive and a hostage.

Now, they know he is dead.

“We have mixed emotions,” says Mr. Mor. “On one hand, our hope ... collapsed. We realize he is no longer with us. On the other hand, the IDF managed to bring him … to be buried in the fields, the land of the kibbutz he loved so much.”

At the funeral last week, two coffins draped with blue-and-white Israeli flags were laid on the ground, side by side: that of Abraham and of his son Roy.

Roy, who had been buried elsewhere because Nir Oz “was still a war zone” at the time, was reinterred to be with his father, Mr. Mor says. “The fact that we managed to bury both of them at the same time, it is like ... closure.”

“Munder,” as Abraham was called affectionately by his friends and wife, fought and was wounded in the 1967 Six-Day War. He settled in the recently established kibbutz after his military service.

He was a choir member who loved to sing and especially enjoyed songs by Nat King Cole and Israeli singer Arik Einstein. He played chess with his grandson.

In a video of Mr. Munder’s funeral, his wife, with her silver curls reflecting the sun, read with a steady voice from a white sheet of paper, her daughter Keren hovering close. “We have missed you for a long time,” Ruth said.

Keren asked her father and brother forgiveness for not being with them “in the darkest moments.”

“You were abandoned, again and again, by the prime minister and his ministers, to Hamas’ tunnels,” Keren was quoted as saying.

Community strength

The two women were sitting shiva, the traditional Jewish mourning period, in Keren’s home. They did not attend Saturday’s rally but sent a message of thanks to those who have faithfully shown support over the months.

Ruth is strong, says Mr. Mor. Keren is wracked with guilt. She feels she abandoned her father, because she focused on protecting her son that day, he says.

The family has now to “settle down and digest what happened,” he says. “It has been a roller coaster, up and down.”

What gives the family strength, Mr. Mor says, is the closeness of the hostages’ families.

“We are ... in the same boat, and we plan our actions together, and we believe that together we have force,” he says. “The power of the forum gives us the strength.”

“We are angry because for five months we could have saved him, and our country did not save him,” he says, adding that he and the rest of the Munder family will continue to go to the demonstrations and support the remaining hostages.

“We have created a family. We continue to fight.”

How one NPR station is trying to win conservative listeners

Many political conservatives increasingly distrust traditional media due to real – and perceived – media bias. A growing number of journalists hope to broaden their reach by reexamining how they do their jobs.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

This spring, veteran National Public Radio editor Uri Berliner sent shock waves through the media industry with an essay titled “I’ve Been at NPR for 25 Years. Here’s How We Lost America’s Trust.” Conservatives – more than a quarter of NPR’s audience in 2011 – had stopped listening, he noted. Moreover, according to a poll, only 3 in 10 people found NPR “trustworthy.”

But NPR’s leadership rejected his critique, and he soon resigned.

Meanwhile, in a largely conservative swath of Pennsylvania, an NPR member station has been taking a more deliberate approach to addressing the trust deficit.

WITF, based in the state capital, is trying to engage with an ideologically diverse range of listeners through in-person events, on-air conversations, and a weekly newsletter that pulls back the curtain on journalistic ethics and decision-making.

The station stands out amid a growing movement nationwide, as traditional outlets grapple with both a crisis of trust in news and fewer resources to produce thoughtful, thorough coverage. Winning back trust in an increasingly polarized nation is a huge challenge. But if successful, it could help journalism become a greater force for good in local communities – and more financially sustainable.

Key to the station’s approach? Humility.

How one NPR station is trying to win conservative listeners

Scott Blanchard was driving a Prius when he first came to work at a local National Public Radio member station here, and joked that the hybrid car – one that some conservatives have derided as a liberal virtue signal — was a requirement.

But Mr. Blanchard doesn’t live among the liberal urban elite. For the past 27 years, he has made his home in a rural Pennsylvania county where two-thirds of voters supported Donald Trump in 2020.

Amid a national crisis of trust in journalism, he and his colleagues at WITF have realized that they have significant work to do in engaging with the largely conservative swath of Pennsylvania where they broadcast. That is part of a broader effort to make their news coverage more trusted and relevant to communities by involving local listeners in helping determine what to cover, how to cover it, and whose voices to include.

“It used to be that we were on a hill transmitting down reams of information to people,” says Mr. Blanchard, WITF’s director of journalism. “But I think as an industry we’ve figured out that’s not really working.”

Simmering distrust has come to a boil in the Trump era, prompting critiques from several prominent journalists. Among them was veteran NPR editor Uri Berliner, who sent shock waves through the media industry in April with an essay titled “I’ve Been at NPR for 25 Years. Here’s How We Lost America’s Trust.”

The son of a lesbian peace activist, Mr. Berliner argued that NPR – the home of “All Things Considered” – had, in the name of diversity and inclusion, stopped considering all things. It had lost its curious, open-minded spirit, and focused on liberal themes. He cited data showing that many conservatives – more than a quarter of NPR’s audience in 2011 – had stopped listening. Moreover, according to a poll, only 3 in 10 people found NPR “trustworthy.”

He urged the organization to better serve the American public. But NPR’s leadership rejected Mr. Berliner’s critique, published by The Free Press without his employer’s approval. He soon resigned.

WITF, meanwhile, has been taking a more deliberate approach to addressing the trust deficit since the contentious 2020 election. It is trying to engage with an ideologically diverse range of listeners through in-person events, on-air conversations, and a weekly newsletter that pulls back the curtain on their work.

“WITF is leading the way in terms of being thoughtful and transparent about their mission, their ethics, and their practices,” says Joy Mayer, founder of the nonprofit Trusting News, who has worked with hundreds of newsrooms, including The Christian Science Monitor.

The station stands out amid a growing movement nationwide, as traditional outlets grapple with both distrust and declining resources to produce thoughtful, thorough coverage. Winning back trust in an increasingly polarized nation – where opposing sides increasingly disagree not only on facts but, more critically, on which institutions have the credibility to confirm facts – is a huge challenge.

But if successful, the efforts by WITF and other news outlets to rebuild trust could help journalism become a greater force for good in local communities – and more financially sustainable.

Mr. Blanchard is not defending journalism’s traditional place on the hilltop; he’s embracing something Ms. Mayer says is essential to rebuilding trust: humility.

“I cannot stress this enough: We are a work in progress,” he says.

In search of conservative listeners – and voices

As soon as Jonathan Brown walked into a WITF News and Brews event this spring, he realized he was vastly outnumbered.

He heard participants praising the Biden administration, criticizing conservatives as being against “reproductive rights,” and talking about the need to “fight against these extremists” showing up at school board meetings across Pennsylvania.

Mr. Brown, a longtime public-radio listener, had been thrilled to hear that WITF had recognized that to prove its trustworthiness to a wider range of listeners, they had to better understand conservatives like him.

But now he realized how hard this work was going to be: Not very many conservatives were engaging with those efforts.

“I think a lot of conservatives would have said, ‘This is exactly what I thought. I’m in a sea of blue, and they’re just going to attack my views. I’m all alone.’ And they wouldn’t come back,” says Mr. Brown, adding that he leaned on his faith in that moment. “I took a pause and centered myself with the Lord.”

He decided to stay – and came away impressed with the sincerity of WITF staffers, two of whom talked with him one-on-one. He resolved, he says, “to be even more engaged in the process and do my best to both provide my point of view and legitimately listen.”

Mr. Brown has since frequently engaged with Mr. Blanchard’s weekly newsletter, designed to spark conversations about everything from using anonymous sources to Mr. Berliner’s criticism. The latter led to Mr. Blanchard hosting a Zoom call with listeners and NPR public editor Kelly McBride.

The weekly missives have also touched on how WITF reporters are striving to use less polarized language and to include a range of perspectives – two things Mr. Brown has noticed them doing well. He says that he has increasingly seen WITF’s reporting become distinct from the station’s other public radio programming – particularly on hot-button issues, from banning school library books to transgender girls competing in girls’ sports.

While the newsletter is WITF’s main way to engage with conservatives, Mr. Brown has encouraged the station’s leaders to do more to welcome such people at their events.

But it’s been tough going. At another News and Brews event this summer, when Mr. Blanchard asked who in the room was right-leaning politically, the Monitor saw two attendees raise their hands. “Good, we’re glad you’re here,” he said.

During a breakout session, one of the attendees said he was there with friends and didn’t have much to say; the other, Don Portner, had brought a couple of friends after attending a previous event. But he and his wife sat in a corner with them and didn’t engage with staffers or other participants.

“If they come to me, I might drop a little hint,” Mr. Portner told the Monitor, expressing frustration with how one-sided news coverage has become, with opinion creeping in to how stories are framed and reported.

Recently Mr. Blanchard asked Mr. Brown to help him connect with fellow conservatives; he has found one so far.

Holding GOP officials accountable for “election-fraud lie”

Part of the challenge is Republican frustration with WITF’s “accountability policy.” In the wake of the Jan. 6 breach of the U.S. Capitol, WITF attributed the assault to then-President Donald Trump’s “election-fraud lie caus[ing] many of his supporters to believe incorrectly that the election had been stolen.”

Therefore, going forward, whenever it quoted or referred to U.S. representatives and state legislators who opposed certifying Pennsylvania’s Electoral College results when Congress met to review the count that day, the station would mention their actions.

“We believe consistently presenting the facts that reveal the lie will play a part in diminishing its power over those who believed and supported it,” WITF explained.

That approach, developed in consultation with NPR’s public editor and Ms. Mayer’s Trusting News organization, garnered national attention – including an interview on CNN. Today it is included in WITF’s broader election coverage guidelines.

WITF’s reputation for its democracy coverage, including its accountability policy, attracted Jordan Wilkie to a job opening as a democracy reporter earlier this year following a project to improve elections coverage in North Carolina. He has faced skepticism from GOP sources due to the policy, but has still been able to land interviews with some lawmakers on WITF’s accountability list.

“Something to be said for showing that you can shut up”

Mr. Wilkie has also embraced another pillar of the newsroom’s efforts to rebuild trust: listening sessions.

It’s a radical, almost counterintuitive idea for a profession that has long seen itself as gatekeepers, not only vetting information but also framing the public conversation by deciding which questions to explore.

“There’s really something to be said for showing that you can shut up,” says Mr. Wilkie.

In June, he convened a small group of Pennsylvania poll workers for a recorded discussion. He let them explore the issues most pressing to them – like how long it would take the constable to arrive if trouble arose, or what to do about a county solicitor reinterpreting a long-standing rule governing who is allowed inside polling stations.

No one mentioned the 2020 elections, despite Pennsylvania being ground zero for the debate over whether the results were fair and accurate.

The closest they came was when Mr. Wilkie asked: “How do errors happen? How do you fix it?”

“The errors are not in someone’s vote being cast,” replied Allison Meckley, a judge of elections in York County. “It’s on the clerical end of our side of it, to make sure all the numbers add up so people can feel there’s integrity in elections.”

Indeed, these poll workers – like journalists – are dealing with a crisis of trust in their field. To Mr. Wilkie, the twin crises are linked.

“I have to rely on the institutions to get my facts,” he says. “As people trust institutions less, they’re going to trust news less.”

Suzanne Fry, who has been a judge of elections for 19 years in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, told the Monitor that she participated in the listening session in hopes of informing voters, including about the checks and balances that ensure an accurate count.

“There’s a lot of misconceptions about the whole electoral process,” says Ms. Fry, who has increasingly seen voters show up “huffy” – something she attributes to the emotionally charged tone of some media outlets these days.

Many mainstream journalists say they wish people would make more informed choices about their news diets. But ultimately, Ms. Mayer says, the responsibility for addressing the trust deficit lies with journalists.

“We serve the public we have, not the public we wish we had,” she says. “Our role in democracy will be completely undermined and made irrelevant if we do not figure out how to earn trust.”

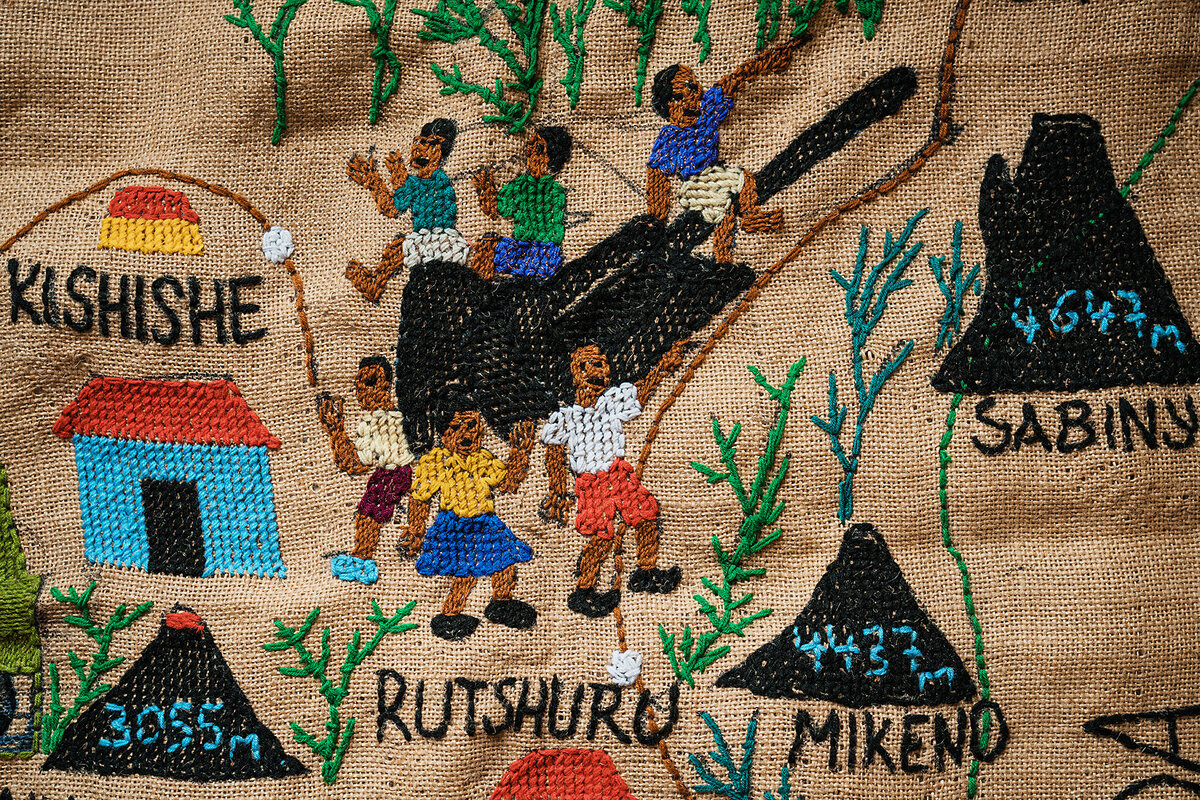

In Congo, embroidery artist stitches an archive of war

Embroidery artist Lucie Kamuswekera stitches vast tapestries depicting the human toll of Congo’s wars. She says she wants this history to be remembered so that it will not be repeated.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Sophie Neiman Contributor

-

Hugh Kinsella Cunningham Contributor

Needle grasped in her wrinkled fingers and tongue between her lips, Lucie Kamuswekera pulls a length of green string in and out of a piece of burlap, stitching a soldier’s uniform the color of pine needles.

From her small workshop in the city of Goma, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, she is working on a tapestry depicting a clash between Congolese soldiers and rebel fighters.

For 30 years, the artist has documented war in eastern Congo this way, with her needle and thread. Her works, which have been exhibited in museums and galleries around the world, depict the staggering human toll of a generation of unbroken conflict.

“I wanted to preserve [these moments] for the future,” she says. “People will come after many years, and they will see. They will learn the history of our country.”

But constantly reliving Congo’s conflicts has also taken its toll on the artist. One day, Ms. Kamuswekera says, she hopes to make art celebrating peace instead.

“Today I am making pictures of war, because we are in a war,” she says. “When the war ends, I will make pictures of peace.”

In Congo, embroidery artist stitches an archive of war

Needle grasped in her wrinkled fingers and tongue between her lips, Lucie Kamuswekera pulls a length of green string in and out of a piece of burlap, stitching a soldier’s uniform the color of pine needles.

She is working on a tapestry depicting a clash between Congolese soldiers and rebel fighters. In the background, civilians flee beneath the spray of gunfire.

For 30 years, the artist has documented war in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo this way, with her needle and thread. Her works, which have been exhibited in museums and galleries around the world, depict the staggering human toll of a generation of unbroken conflict.

From colonial rule to attacks by armed groups, Ms. Kamuswekera stitches images of events that many around her long to forget. She does so, she says, because she believes ignoring the past will allow it to repeat itself.

“I wanted to preserve [these moments] for the future,” she says. “People will come after many years, and they will see. They will learn the history of our country.”

A vibrant archive

Ms. Kamuswekera, who is 80 years old, learned embroidery as a young girl in missionary school, when Congo was still a Belgian colony.

The nuns taught her to stitch delicate flowers and birds, and for decades, as she built her career as a nurse, that was all she thought to make.

Then, in the mid-1990s, violent conflict broke out in eastern Congo as rebel groups, supported by neighboring governments, fought to overthrow Congo’s longtime dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko. The war’s battlefields bled into the countryside, making the conflict extraordinarily dangerous for civilians. In 1997, Ms. Kamuswekera’s husband was killed while walking to their farm.

After that, she says, she didn’t want to sew flowers anymore.

“Today I am making pictures of war, because we are in a war,” she says simply. “When the war ends, I will make pictures of peace.”

Ms. Kamuswekera works from a small studio made of clapboard and cinder block, which juts out from the front of her home on the outskirts of the city of Goma. Dusty sunlight filters through holes in the corrugated metal roof, and the walls are covered floor to ceiling with her art. Brightly colored plastic sacks stuffed with more works clutter the floor, serving as both informal storage and additional seating in the cramped space.

The small room is a vibrant archive of recent Congolese history.

One of the largest works shows Congolese men with their hands bound and backs lashed, in punishment for upsetting the Belgian colonial authorities. Four others carry an official in a white hat atop a palanquin. It is a scene Ms. Kamuswekera says she witnessed herself.

On the opposite wall is a rendering of Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the former Congolese president, who took power in the war that killed her husband.

After that conflict, the First Congo War, ended in 1997, another began almost immediately. Since then, eastern Congo has endured repeated waves of violence, which have killed more than 6 million people.

Ms. Kamuswekera’s tapestries document these wars in detail.

Most recently, she has created artwork about the rebels from the March 23 Movement, or M23. Originally founded by disgruntled Congolese soldiers in 2012, the rebel group has grown more active over the last two years, allegedly backed by the governments of neighboring Rwanda and Uganda.

The latest of these tapestries were rendered as the rebels encircled Goma in recent months.

Some of Ms. Kamuswekera’s hangings have political messages. One, depicting women cowering behind bushes and trees, demands an end to sexual violence. In another, a man weeps below a banner decrying the sale of Congo’s mineral wealth, the text of which asks how the country can be so rich and so poor at once.

Ms. Kamuswekera embroiders from memory when she can. When she cannot, she questions other observers, fastidiously ensuring that each detail she stitches is accurate.

The artist also uses a stack of images given to her by a photojournalist, which provide a portal to places she has not seen.

Her work is painstaking. Stitching a human face takes five days’ careful embroidery, but selling the tapestries is hard.

“People don’t buy,” Ms. Kamuswekera says glumly, clasping her hands together. Even when she makes a sale, she anxiously wonders when the next customer will arrive.

Meanwhile, the conflicts she documents affect her daily life, too. The latest surge in violence has made roads in and out of Goma unsafe, driving up the price of food and other necessities.

Sometimes, she thinks about quitting embroidery altogether.

“The history will not disappear”

Constantly reliving Congo’s conflicts has also taken its toll on the artist. One day, she hopes to make art celebrating peace instead.

At the bottom of a wall, in the far back corner of her studio, is a tapestry showing people happily drinking and playing drums beside their thatched huts. Ms. Kamuswekera describes it as a celebration of Pan-Africanism. She wants to make more like it.

But at the age of 80, her concentration is beginning to ebb. Her eyesight is fading and her knees pain her. She finds it difficult to sit for long hours pulling her needle repetitively in and out of burlap.

Determined to ensure her craft lives on, the artist is now passing her skills on to her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

“Everybody in the family knows this art,” her grandson Jojo Lukongya says proudly.

These pupils sit watching as she works, their concentration as taut as the threads in Ms. Kamuswekera’s hands. Mostly, though, they learn by doing, quickly taking up tapestries of their own.

Because Ms. Kamuswekera cannot speak French, her family members sketch French titles atop each tapestry, which the artist carefully traces in yarn. “Non à la Corruption,” reads one. “La mort de Lumumba,” reads another that depicts the life and death of Congo’s first postindependence leader.

“We shall take it up and continue her work,” says her great-granddaughter Phenic Kahindo Musyanilya, while weaving images of different villages caught in battles between rebel factions in the M23 conflict. “The history will not disappear nor be forgotten.”

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Essay

Hot crabs and cold lemonade: A window into my Cajun childhood

Whatever is served – lasagna, biryani, or tamales – family dinners are a powerful means of connection, anchoring, and belonging. Our writer reminisces about the potent sense of kinship he felt during his Cajun country crab nights.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Claude Barilleaux Contributor

On sweltering Friday nights of my 1950s youth in Louisiana’s Cajun country, my family and I thumbed our noses at the humidity and sat down to a spirited supper of spicy boiled crabs, the peppered vapor from the boiling pot fusing with the sultry air.

My mother set the water to boil in large pots, and threw in rock salt, chunks of lemon, green peppers, onions, celery ribs, and cayenne pepper. Using sturdy tongs, she dropped live Blue Point crabs fresh from the Gulf into the water in an intricate pattern to get as many into the pot as possible.

As delicious as the crabs were, the freewheeling family discussion circling the table made the evening even more special. As we thumped and cracked, we discussed current events, sought advice, speculated on life, and listened to my parents’ stories of their own childhoods.

While we had been boiling in the heat on those treasured Friday nights, the peppered family humor had brought smiles and laughter. And, for a little while, the sweltering summer air had seemed cooler.

Hot crabs and cold lemonade: A window into my Cajun childhood

It’s summer in New York, and hot, steamy air closes in around me even in the evenings. Not a time to think of large pots of water boiling on a stove. But I do. Summer takes me back to the near-tropically humid nights of my 1950s youth in Louisiana’s Cajun country. I remember sitting immobile before the sluggish gusts of an oscillating fan, the saturated air pressing down on my body. The sun’s setting had brought little relief, only a clammy listlessness.

Except on Friday nights. On Fridays my family and I thumbed our noses at the humidity and sat down to a spirited supper of spicy boiled crabs, the peppered vapor from the boiling pot fusing with the sultry air.

Friday was the night for crabs. My mother knew they satisfied the appetites of her five growing sons, and that my father found nothing more relaxing than hammering away the week’s aggravations on his favorite seafood.

Cajuns ordinarily boil crabs outdoors, but not my mother. Reasoning that a few more degrees of heat wouldn’t make much of a difference, she brought the outdoors inside.

Late Friday afternoon she set the water to boil in two old large pots, and threw in rock salt, chunks of lemon, green peppers, onions, celery ribs, and cayenne pepper. Using sturdy kitchen tongs, she lifted live Blue Point crabs fresh from the Gulf from a wooden basket at her feet and dropped them into the water in an intricate pattern to get as many into the pot as possible. She added small red potatoes.

Invariably, a bold crab made a sideways run for it, leaping from the basket and heading for open sea. But it never got far. She always apprehended escapees.

While my mother watched over the pots, an invisible cloud of peppery steam filled the house, tickling our noses and bringing on a happy sneeze or two. My brothers and I hurriedly laid out layers of newspaper on the dining table, placed rolls of paper towels at each end, and left a single table knife at each place setting. My family, like most Cajuns, used only one knife to open the crabs, not the mallets and nutcrackers Northerners might use.

As the last crabs turned from blue-gray to fire red, my mother called out final instructions. One brother would mix small bowls of mayonnaise and ketchup, a sweet concoction in which to dip the spicy potatoes, while another brother set out baguettes of crusty French bread and a pitcher of lemonade. My father would grab a cold drink from the ancient refrigerator on our screened-in back porch. When everything was ready, we helped my mother carry round trays piled precariously high with crabs to the table.

We sat down at our oval table, my father at the head, my mother to his left, my youngest brother next to her, then me, my left-handed older brother at the table’s foot, my second-to-youngest brother following the table’s turn, and my oldest brother completing the circle. It was a hard-and-fast seating arrangement. We bowed our heads, gave thanks for the bounty of the Gulf of Mexico and for my mother’s hard work, and then, ravenous, selected our first crabs to tackle.

My parents had taught me how to peel my own crabs at a young age. Peeling crabs for another person automatically qualifies a person for sainthood. My parents were saints, but they had their limits.

It isn’t difficult: Twist off the claws, hammer them open, extract the meat, pop it into your mouth, savor. Twist off the legs, separate the top shell from the bottom at the small tab under the crab, scoop the rich brown fat from inside the top shell’s corners, savor. Break the bottom shell in two, dig the white crabmeat from the honeycombed chambers with your fingers, then throw the emptied shell into a pile in front of you. Simple.

As delicious as the crabs were, the freewheeling family discussion circling the table made the evening even more special. As we thumped and cracked, we discussed current events, sought advice, speculated on life, listened to my parents’ stories of their own childhoods, debated politics. Arguments might erupt, but mostly we tried to best one another with humor. My family prized quick comebacks, funny ideas, irony, and bad puns. A deep groan was appreciated as much as a hearty laugh.

The meal did not end but casually petered out. I knew I was done not because I felt full but because I was tired of peeling crabs and had built a large pile of shells in front of me. I asked to be excused and thanked my mother. I washed the pungent crab smell off my hands and changed my shirt. My parents were the last to leave the table, my father continuing to pound away on the crabs while my mother kept him company. When they finished eating, my brothers and I returned to help clean up.

My mother stopped boiling crabs after my brothers and I left home and my father passed away. When I visited her, we went out for crabs at a seafood restaurant in my hometown. But it wasn’t the same. Restaurants had introduced stainless steel tables with holes in their centers where you would throw crab shells, and they even offered mallets and nutcrackers.

It was all sanitized and genteel. The casualness of home, free from polite table manners, was missing. The seasonings didn’t seem right. Without a pile of crab shells in front of me, I felt I had not accomplished anything.

I missed the intimacy of sitting around our dining table piled high with steaming crabs boiled by my mother. I missed the homemade sauces, the crusty French bread, the expected seating arrangement. I missed the easy family banter. While we had been boiling in the Louisiana heat on those treasured Friday nights, the peppered family humor had brought smiles and laughter and tested our mental agility. And, for a little while, the sweltering summer air had seemed cooler.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Attitudes shift for Arab women

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Violent conflicts in the Middle East have obscured an important step toward equality in the region. In Saudi Arabia, for example, women now make up 35% of the workforce, already exceeding the government’s target of 30% by 2030. In Kuwait, 58% of women are formally employed. Those changes represent a “seismic shift in women’s work opportunities over the past decade,” noted Jennifer Peck, economics professor at Swarthmore College.

Such efforts coincide with a wider reform in religious thinking. Last month, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation held a summit of ministers and scholars to advance women’s rights in Muslim societies. The gathering was based on a document adopted by the organization’s 57 member states in May that grounds gender equality in Islamic law.

Many other Mideast countries seek a more globally competitive workforce, causing changes in norms about female employment. Researchers have found one beneficial effect: A study by Arab Barometer reveals that having more women in the workplace raises their status at home.

The wars in the region – from Gaza to Yemen to Sudan – have imposed a disproportionate harm on women and girls. Yet the Middle East has another story to tell – of peaceful gains in equality and respect for its female citizens.

Attitudes shift for Arab women

Violent conflicts in the Middle East have obscured an important step toward equality in the region. In Saudi Arabia, for example, women now make up 35% of the workforce, already exceeding the government’s target of 30% by 2030. In Kuwait, 58% of women are formally employed. Women now hold positions as ambassadors, ministers, university presidents, and judges. Those changes represent a “seismic shift in women’s work opportunities over the past decade,” noted Jennifer Peck, economics professor at Swarthmore College, in Foreign Affairs recently.

Such efforts coincide with a wider reform in religious thinking. Last month, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation held a summit of ministers and scholars to advance women’s rights in Muslim societies. The gathering was based on a document adopted by the organization’s 57 member states in May that grounds gender equality in Islamic law.

Many other Mideast countries seek a more globally competitive workforce, causing changes in norms about female employment. Researchers have found one beneficial effect: A study by Arab Barometer reveals that having more women in the workplace raises their status at home. “If more men have wives and daughters who have held a job, it appears that support for the male household head unilaterally making family decisions is likely to decrease,” it found.

In Morocco and Mauritania, the study stated, “regardless of whether society has traditionally viewed decisions as a ‘man’s job’ or ‘woman’s job’, being related to a woman who has held a job encourages gender neutral views. We see movement towards shared responsibility.”

That insight, based on research in seven countries across North Africa and the Middle East, adds evidence that opposition to gender equality may yield more readily than assumed – even in traditionally male-dominated societies. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research of perceptions of gender norms in 60 countries, revised in February, found that men and women more often align in their support for equality.

“Misperceptions of gender norms are ubiquitous around the globe,” one author of the study, Stanford economist Alessandra Voena, said in a Stanford interview last year. “Simply informing people that their perceptions of those norms are wrong could be a very effective way to make meaningful progress far more quickly.”

Gains in the workplace for Mideast women are raising expectations of further social change. Kuwait, for example, acknowledged that an “empowering environment” for women must include an end to the traditional forms of violence they endure, such as honor killings.

The wars in the region – from Gaza to Yemen to Sudan – have imposed a disproportionate harm on women and girls. Yet the Middle East has another story to tell – of peaceful gains in equality and respect for its female citizens.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What to do when you don’t know what to do

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

If it seems we’re at a crossroads of uncertainty about how to move forward, prayerfully opening our hearts to divine inspiration is a powerful starting point for peace of mind and next steps.

What to do when you don’t know what to do

I took modern dance in college, and although that was a long time ago, something the dance teacher said still comes back to me often. She told us that if you forget your next move and don’t know what to do, just keep dancing.

I have found this advice – “just keep dancing” – very transferable to life’s many situations since then. Over the years, when at times I have felt at a loss to know what to do, it has been my first inclination to pray to God. The willingness and commitment to “just keep praying” has always brought needed answers.

The Apostle Paul – a follower of Jesus’ teachings – was met with a number of very difficult situations. It’s easy to imagine him facing the question of what to do. And he offered this counsel: “Pray without ceasing” (I Thessalonians 5:17).

Once, Paul and his companion Silas were thrown in jail and their feet put in the stocks because of objections to their Christly, healing teachings. Their response was to pray and sing praises to God. Everyone in prison heard their rejoicing. I like to think of it as a celebration of absolute trust in the protecting presence of God, who loves and cares for all.

It is recorded that suddenly there was an earthquake that caused all the doors to open and all the prisoners’ chains to break. The jailer, seeing the doors open, was ready to take his own life for fear of being blamed for everyone’s escape. But the prisoners had not fled, as Paul assured the jailer – who soon became a follower of Jesus’ teachings (see Acts 16:19-36).

Although I can hardly compare myself to Paul and the scale of the difficulties he faced, I’ve found encouragement in his example.

I recall an experience years ago when I was at a crossroads about what to do. I had decided to leave the university I had been attending for a year and a half. It had become clear that it wasn’t the right place for me – but it was not clear what was.

I’d begun to study Christian Science shortly before attending this university, and it had become very close to my heart. I was learning that God is Spirit – completely good and perfect – and that He created everyone in His image, wholly and solely spiritual and good, lacking nothing.

This spiritual truth filled me with a sweet sense of God’s guiding presence, which I felt all through this experience, even when I had no idea how to proceed. In the following months, as I continued to pray to understand more deeply our true, spiritual identity, I felt irresistibly drawn to apply to a particular college.

So I did – but when September rolled around, I hadn’t heard anything from anyone at the school. A doubting dread blanketed my thought. Questions swirled – not only as to what to do if I was not accepted, but as to what to do at that moment to gain a much-needed sense of peace.

I considered this statement on page 506 in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science: “Spirit, God, gathers unformed thoughts into their proper channels, and unfolds these thoughts, even as He opens the petals of a holy purpose in order that the purpose may appear.”

This became my ceaseless prayer, and those ideas of gathering, unfolding, and opening took on a deeper meaning for me. This is what God does for us at every moment! Our life and purpose – to joyfully reflect God’s goodness in unique and abundant ways – are always active, even when we don’t feel we can see exactly what that looks like.

Peace came as I felt lifted to a steady expectancy of good that outshined fearful wondering about what I should do. I knew God was always taking care of me.

I felt the clear directive to patiently wait. And shortly thereafter I very happily received the news that I had been accepted to the college, which ended up being exactly what I needed for going forward personally and spiritually. Even greater than my delight at the acceptance was my gratitude for what this experience taught me about the spiritual joy and uplifting of thought that comes from “praying without ceasing.”

If it seems as though we don’t know what to do, we can always “just keep praying” for divine inspiration and guidance. And we’ll discover that forward steps and goodness are always close at hand.

Viewfinder

Red sea

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with the Monitor today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow to hear about one success story in overcoming the learning loss that happened during the pandemic. High-impact tutoring has helped close post-pandemic student gaps and led to higher attendance rates. It is increasingly seen as an integral part of public schooling.