- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Florida woman kills wild boar with mango. (This is not a meme.)

- Today’s news briefs

- Boko Haram made them child soldiers. Will their communities take them back?

- UK’s fight against far-right hate goes online, but does it go too far?

- Tutoring is getting kids excited about school. Educators want to make it permanent.

- In sports, the arts, making room for mental health and disabilities

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Extending a hand to child soldiers

Can you ever really go home again?

Most of us like to think yes. But what if the reunion involved young fighters for the Nigerian insurgent group Boko Haram?

The Nigerian government has long urged these young soldiers, many of them violently kidnapped as children, to “come home.” In the past three years, growing numbers have. Can they find the fortitude to press through the suspicion and anger that meets them? Can those receiving them trust the power of forgiveness and redemption? Today’s story from Nigeria strikes a deep chord as it explores the unflagging commitment of those helping these former child soldiers find a peaceful path forward.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Florida woman kills wild boar with mango. (This is not a meme.)

Florida calls itself a bulwark of freedom. That’s one reason so many move here. Others find it repressive, and are ready to leave.

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

Florida has a certain reputation around the United States.

It’s a place where strip malls with gun ranges and gentlemen’s clubs might include storefront houses of worship. North of Tampa, mermaids hold government jobs as finned entertainers at Weeki Wachee Springs State Park. Not too far away in Land O’ Lakes, the annual Caliente Bare Dare 5K is billed as the largest clothing-optional race in North America.

Florida is also the place where 100 Miccosukee refused surrender during the Seminole Wars in the mid-19th century. Avoiding capture and the infamous Trail of Tears, these Indigenous people disappeared into the Everglades. Today there are about 600 free Miccosukee, many of whom still live in “chickees,” thatched-roof houses on stilts within the Everglades.

“The free state of Florida” has long been a beacon of free expression, thought, and action. The first chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union south of the Mason-Dixon Line was founded here. Other leading lights include the environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the novelist Zora Neale Hurston.

Florida elected the first Hispanic congressman, José Mariano Hernández, in 1822. It also sent the first Jewish man to the U.S. Senate, David Levy Yulee, in 1845. Representative Hernández was an enslaver, as was Senator Yulee, a secessionist who converted to Christianity.

“Florida is a paradox,” says Jack Davis, professor of history at the University of Florida.

“It is people reinventing themselves,” he says. “It offers tropical freedoms and dreams. But in certain particular behaviors and activities, there’s been a backlash.”

Florida woman kills wild boar with mango. (This is not a meme.)

Carol Etscovitz knows the exact moment she transformed into a Florida woman: the night she killed a boar with a mango.

She’d just been wandering through Promised Land, the name of the 300-tree, 40-acre property she owns with her husband, David. Their tract of land is tucked away in the subtropical vegetation of Pine Island, Florida, a massive, mangrove-ringed barrier island just off Cape Coral on the state’s Gulf side.

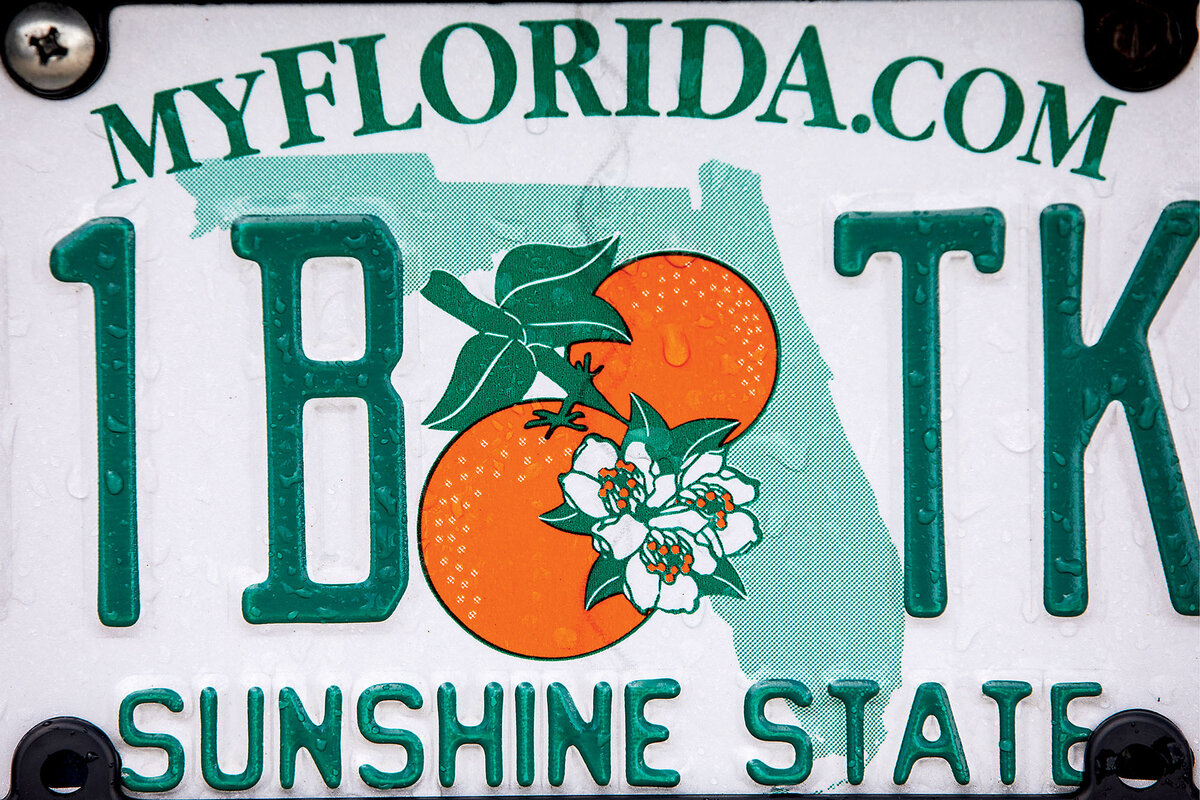

It’s full of razorbacks. Hundreds of boars and sows roam Pine Island, scrunching their snouts into burrows and feasting on fermenting fruit. Locals often patrol the island, sometimes shooting, sometimes trapping dozens of these feral pigs to get rid of them. (It’s legal to hunt and kill wild boars year-round in the Sunshine State.)

For the Etscovitzes, it’s just a hint of old Florida’s wildness – and just what they were looking for when they moved here from Hampstead, New Hampshire, in 2015.

But they were also seeking something less tangible, and harder to put into words: a sense of freedom.

Florida has emphasized its promises of freedom over the past few years. In July, the state unveiled new highway signs that read, “Welcome to the Free State of Florida.”

Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, too, often proclaims the state a “liberty outpost” when comparing it with others, particularly those led by Democrats. “While so many around the country have consigned the people’s rights to the graveyard, Florida has stood as freedom’s vanguard,” the governor said in his State of the State address in 2022.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that the Etscovitzes left New Hampshire, the “Live Free or Die” state. The libertarian Cato Institute ranks it America’s freest. The Washington-based think tank ranks Florida the second-freest state.

Like a lot of transplants from up north, they were seeking to escape the cold and snow. Mr. Etscovitz says he was tired of being “stuck watching the wall all winter.”

Taking on Promised Land – and a wild boar

They didn’t find Promised Land right away. The Etscovitzes first purchased a property in the unincorporated Myakka City area in central-western Florida.

The land was far enough inland so they could afford sufficient acreage to graze their goats, which they turned into an all-natural weed-whacking business. To their delight, they were just an hour from the beach. It was, almost, everything they ever wanted.

But Florida’s economy was churning, and the area began to change. Hundreds of homes sprang up nearby, changing the character of their dream spot. What had once been an easy jaunt to Gulf beaches became a traffic-choked slog.

After living in Myakka City for seven years, they sold the property even before they found a new place. With just days before they had to vacate their herd from the Myakka City property, they decided to cross the bridge into Pine Island on a whim.

They drove past the colorful fish shacks of Matlacha. They smelled the salt in the prevailing westerly winds. That’s when Mr. Etscovitz spotted a rutted road through the vegetation. He said to his wife, “Let’s go down here.”

They found the Promised Land property. When Mr. Etscovitz asked the owner whether he knew about any property for sale on Pine Island, he said, “Funny you should ask.”

“I knew we had found where we belong,” Ms. Etscovitz says.

After they purchased the mango grove in 2022, she loved to wander through their new property. A few months after they moved in, she had her first face-to-face encounter with one of Pine Island’s feral pigs.

She was taken aback by its size and lack of fear of her presence. “Whoa,” she remembers thinking. “What’s up with this thing?”

“It was fall. It was pitch-dark and I had a flashlight, and this was a big pig,” she says. “And they will kill you and eat you.”

But what she remembers feeling wasn’t so much fear. She almost felt insulted by its insouciance as it rooted in her grove.

“I was mad,” she says. “Here’s this thing that doesn’t belong here, and he should be running away from me. Dave’s inside; he can’t hear me. I’ve got to deal with this pig.”

So she grabbed a mango that was pretty solid. “I picked it up and whipped it,” she says. Bop. Her aim was true. Bell rung, the creature rushed headfirst into a pond. The next day they found the boar, dead, its hams jutting just above the water.

“I have the worst aim on the planet, so this was an inspired hit,” she says.

The Etscovitzes make a modest living selling mangoes, honey, and chutneys. They have 40 goats, a 31-year-old horse, and a donkey on the property, as well as tortoises and turkeys. They invite their guests to interact with them.

It’s a struggle, actually, but it’s part of the sense of freedom they were looking for. Indeed, as an emblem of freedom, Mr. Etscovitz says, the grove isn’t about perfection, but about living one’s life intentionally, without judgment or interference.

For all its faults, he says, Florida has provided that space for their understanding and self-exploration. Personal freedom is coupled with what he and his wife are practicing at Promised Land: stewardship of both a historic grove and a way of living.

And that, Mr. Etscovitz says, is rooted in a sense of ownership, responsibility, and self-awareness that stretches beyond one’s property and impacts society more broadly.

“When people get in their element, they get happy, whether it’s on the water or anything,” he says. “I see so many people come down here: They do this; they do that. The people who are really having a good time are the ones that keep going.”

“This is a slice of old Florida,” he adds. “I just hope we can keep it.”

Florida has a rich history – and a quirky reputation

Florida has a certain reputation around the United States.

In Florida, mermaids hold government jobs as finned entertainers at Weeki Wachee Springs State Park north of Tampa. Not too far away in Land O’ Lakes, the annual Caliente Bare Dare 5K is billed as the largest clothing-optional race in North America.

It’s a place where strip malls with gun ranges and gentlemen’s clubs might include storefront houses of worship.

Florida is also the place where 100 Miccosukee refused surrender during the Seminole Wars in the mid-19th century. Avoiding capture and the infamous Trail of Tears, these Indigenous people disappeared into the Everglades. Today there are about 600 free Miccosukee, many of whom still live in “chickees,” thatched-roof houses on stilts within the Everglades, and near the tribe’s village on the Tamiami Trail.

“The free state of Florida” has long been a beacon of free expression, thought, and action. The first chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union south of the Mason-Dixon Line was founded here. Other leading lights include the environmentalist Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the novelist Zora Neale Hurston.

Florida elected the first Hispanic congressman, José Mariano Hernández, in 1822. It also sent the first Jewish man to the U.S. Senate, David Levy Yulee, in 1845. Representative Hernández was an enslaver, as was Senator Yulee, a secessionist who converted to Christianity.

“Florida is a paradox,” says Jack Davis, professor of history at the University of Florida and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book “The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.”

“It is people reinventing themselves,” he says. “It offers tropical freedoms and dreams. But in certain particular behaviors and activities, there’s been a backlash.”

Governor DeSantis has turned what was a narrow mandate when he came into office “into a red bulldozer,” says Florida historian Steve Noll.

Taking a far more muscular understanding of the role of government, the two-term governor has in many ways helped redefine conservatism as he’s championed laws to limit access to books. He’s also taken on private businesses, signing into law restrictions on diversity, equity, and inclusion practices and critical race theory.

“DeSantis ... says that Florida is the freest state: You’re free to carry arms, free to move about with low taxes, all that stuff,” Mr. Noll says. “But for another set of people, it is definitely unfree.”

“People who come here don’t think that Florida has a history, that it starts with them moving across the state line,” says Mr. Noll, coauthor of “Ditch of Dreams,” a book about a failed cross-Florida canal. “That’s what makes this state so complicated.”

Florida’s history in many ways epitomizes the contrasting understandings of freedom that so divide the country as a whole today.

“I think a lot of this grandstanding against liberals – inviting them to leave if they’re unhappy with the state and of course not inviting them to come – is in fact working,” says Dr. Davis. “It’s turning the state of Florida increasingly red and moving away from the purple.”

For some residents, Florida’s brand of freedom has become stifling

For almost two decades, Paul Ortiz and Sheila Payne were two of the best-known community activists and scholars in Alachua County, Florida, and its largest city, Gainesville.

They’ve always thought a lot about the meaning of freedom. It’s their lifework, in fact.

Dr. Ortiz is a nationally recognized and award-winning scholar, and until this summer he was a professor of history at the University of Florida. He also directed the university’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, a position he had held since 2008.

Ms. Payne is a born-and-bred Florida woman. When she was 16 years old, she was the rodeo queen of Homestead, Florida. After years as a postal worker, she became a labor and fair housing activist, receiving recognition for her community service and winning numerous awards, including the 2022 Rosa Parks Quiet Courage Award.

The couple bonded after they were jailed together in 1995 during a farmworker protest in California. Dr. Ortiz jokes that the shared experience convinced them they could survive marriage together as well.

But as their home state of Florida started to become one of the most aggressive in the nation, restricting books and banning ideas, they decided they should leave.

This summer, in a kind of reversal of migration patterns, they packed their possessions and moved to New York, where Dr. Ortiz accepted a position as professor of history at Cornell University in Ithaca.

“Florida is very complex,” Dr. Ortiz says. “I love Florida, the community. We hate to leave it. But Governor DeSantis has made it clear that he doesn’t think that sociology or women’s studies are valid majors.”

The DeSantis administration calls its efforts to restrict books and ideas, especially those that focus on human sexuality and the experiences of people of color, as “freedom from indoctrination.”

But Dr. Ortiz sees these efforts differently. “In Florida today, shutting the school library down [so it can be inspected for banned books] is a version of freedom – the freedom to dictate,” he says.

It’s like living in “the upside down,” he says, referring to a 2022 court ruling that referenced the Netflix hit show “Stranger Things.” Florida has given the government the freedom to dictate what people can say and teach, even in private institutions.

In July, a federal judge issued a final ruling on a large part of Florida’s controversial “Stop WOKE Act,” declaring it a violation of the First Amendment. The 2022 law had limited private companies from using diversity, equity, and inclusion practices, and from referring to racial issues during job trainings.

“This Court is once again asked to pull Florida back from the upside down,” wrote U.S. District Judge Mark Walker, an Obama appointee.

In 2018, the couple had felt a modicum of optimism after Ms. Payne spearheaded an effort in Alachua County to gather petitions to put a voting rights referendum on the ballot that year.

The referendum restored voting rights to those who have served a sentence for a felony. Not only did it make the ballot, but it was also approved by 64% of Florida voters.

“We talked to a lot of people who wore MAGA hats, who identified as Republicans,” says Dr. Ortiz.

“We didn’t convince everyone, but their thing was, ‘Look, these people, if they’ve done their time, they’ve paid their penalties to society; they should get their voting rights back.’ We could not have won that struggle and got it on the ballot unless we actually attracted a lot of Trump and DeSantis supporters,” he says.

As a Florida historian, he spent most of his career teaching students about Florida freedom struggles. His award-winning book “Emancipation Betrayed” explores the history of the struggles of Black people trying to find freedom in Florida.

Dr. Ortiz also studies the descendants of Black freedom fighters who fought in the Seminole Wars during the administration of President Andrew Jackson.

“Those struggles for freedom,” he says, “are exactly what Ron DeSantis and the state of Florida don’t want you to know about. They want you to believe that the U.S. was created equal, perfectly.

“But the idea that African American slaves would come to Florida and have to fight the U.S. government in the Second Seminole War – that was the second-most expensive U.S. war, per capita, and it was a war for freedom against the United States of America – [this shows] there has been a continuity in terms of Black and Native freedom struggles here,” Dr. Ortiz says.

But the pressure of living in a state becoming more and more hostile to such ideas – it was crushing his spirit. He had to leave.

“I’m not leaving just because of Florida,” Dr. Ortiz says. “I didn’t grow up in a perfect society. But I don’t remember librarians getting death threats. There’s something deeply wrong. It’s craziness.”

A conservative “utopia” that began with lockdown defiance

On the road connecting the dirt-poor farming communities of unincorporated Immokalee with the wealthy beach enclaves of Naples, Florida, there sits a 75,000-square-foot supermarket unlike any other.

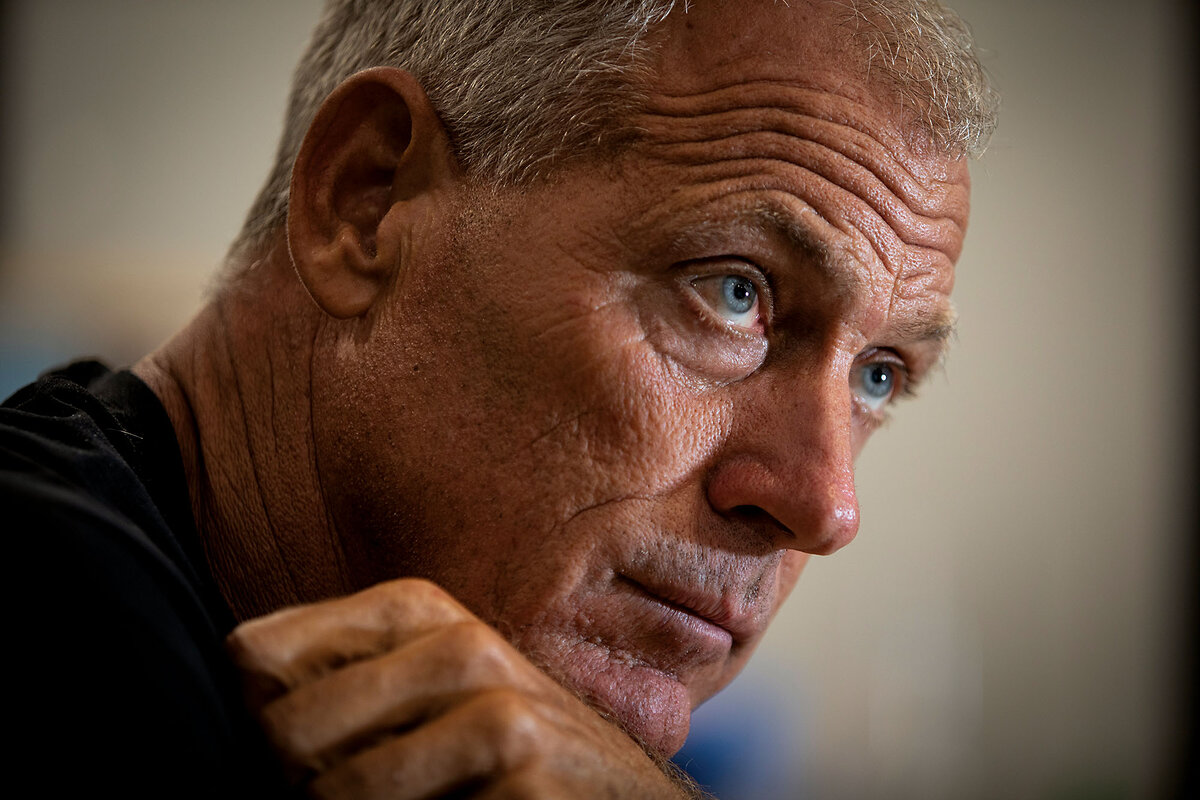

It’s called Seed to Table, and it’s the flagship store of Alfie Oakes, the entrepreneur and businessman in Collier County who owns and runs Oakes Farms, an operation that employs over 3,500 people and takes in around $25 million a year.

Mr. Oakes is also a controversial political firebrand and kingmaker in the Collier County chapter of the Florida GOP. And make no mistake, he is obsessed with freedom.

In many ways, he’s a classic conservative businessman, decrying burdensome government regulations and the morass of bureaucracies that stifle economic growth and innovation.

But this wariness of big government has morphed into something deeper. He views government and health officials, especially, as mostly a bunch of freedom-taking tyrants. This would include most of the establishment of university-trained professionals who populate most American institutions.

Mr. Oakes’ company is one of the largest independent agribusinesses in south Florida, consisting of more than 1,800 acres of farmland, numerous aquaponics and greenhouse facilities, and a fleet of over 100 trucks for its wholesale and retail operations.

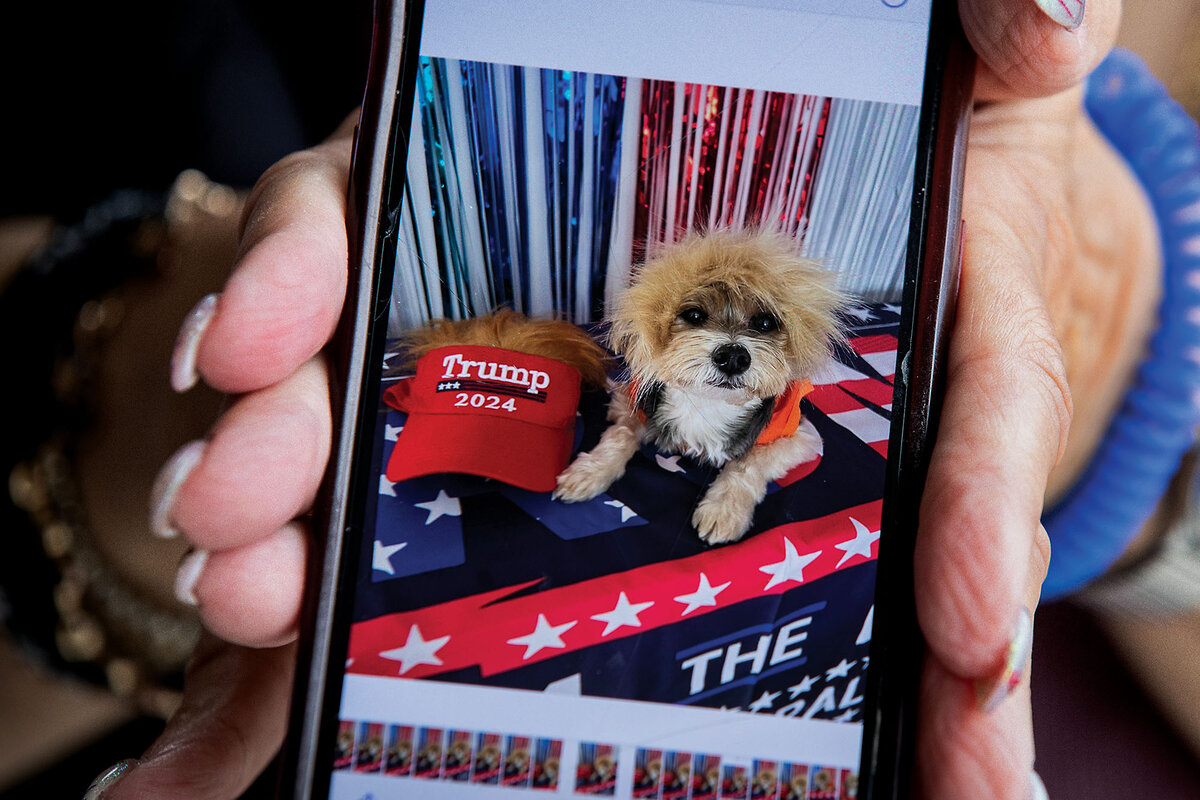

But Seed to Table – which has sprawling spreads of produce, a food court with restaurants and kiosks, and a two-story wine market and tasting room – has become a MAGA mecca, many say, a shrine to former President Donald Trump and Trumpism.

The Florida entrepreneur launched Seed to Table in 2019 with fanfare. Then the pandemic struck, and Florida, like the rest of the country, ordered most residents to shelter in place, and the global shutdown began.

Everything about the government-ordered shutdown infuriated Mr. Oakes. His reaction? Defiance.

As an essential business with essential workers, Seed to Table didn’t have to be shut down. But Mr. Oakes openly flouted restrictions on large gatherings, making his supermarket in many ways a place to party. In fact, it became a pandemic destination.

“People were looking for freedom when they came here,” says Mr. Oakes, who currently serves Collier County as a state committeeman for the Republican Party of Florida. “They fell on their knees and cried. They came from lockdown cities and couldn’t believe what they saw. They didn’t think a place like this even existed.”

As a result of his defiance, he and fellow Republicans have dubbed Collier County “Freedom Town USA.”

Mr. Oakes’ story fits into classic patterns of American mythology and ideas of self-won freedom. In the 1970s, his father, Francis Oakes Jr., fled to Florida, chased by creditors. He brought his family to a run-down part of Fort Myers, opening a small grocery market that struggled.

When the younger Mr. Oakes was a teenager, he decided to buy a truck and drive to Immokalee farms to buy tomatoes and watermelons in bulk. He sold them from the back of his truck on a road approaching the Cape Coral Bridge, which spans the Caloosahatchee River.

In 1986, when he was 18 years old, he opened his first market after leasing 40 acres of land to grow zucchini. He was brokering wholesale deals by the time he graduated from high school.

The elder Mr. Oakes’ legacy as a fierce champion of organic produce continues to impact his son. He calls his father’s efforts “a search for food freedom,” which he says goes to the core of health, awareness, and even identity.

Mr. Oakes is actually pretty crunchy for a conservative, if not necessarily a MAGA Republican. He’s proud to say he doesn’t use deodorant or sunscreen, saying they are potentially health-damaging.

He’s also building a clinic that will feature a newfangled hyperbaric oxygen chamber that simulates the pressure on the human body at 30,000 feet. This is said to increase oxygen to the body and help with health and longevity.

And while there have long been government restrictions on the sale of raw milk, Mr. Oakes believes raw milk is a cornerstone of health. After years of wrestling with health regulators, he bought his own small dairy farm that now supplies his store. The compromise with health officials is that his raw milk labels say, “Not for human consumption.” Most of his customers disregard what they see as the government’s wagging finger.

In February, he helped Collier County stop putting fluoride in its drinking water, which he believes is harmful.

“There’s an effort to shape a utopia here, and, honestly, I didn’t see it coming,” he says. “But so far, it’s working.”

But Mr. Oakes can be brash and aggressive in his political statements. He’s called George Floyd, who was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis, a “disgraceful career criminal.” During the 2022 midterm elections, he warned that if Democrats “steal” another election, “I have enough guns to put in every single employee’s hands. I hope it never gets there.”

His inflammatory rhetoric has made his company lose business. He has had numerous contracts supplying food for the Department of Defense and other federal agencies, as well as some local school districts. A few of these have been canceled.

He says it’s the kind of targeted oppression that justifies some of Florida’s efforts to crack down on the ideas that fuel an oppressive Democratic-led society.

Desre Buirski sits outside Seed to Table, selling Trump paraphernalia. A self-described freedom fighter, she’s a conservative activist who agrees that sometimes freedom and authoritarianism are compatible. Efforts to restrict the ideas and actions of some can be done for the greater liberty of the tribe, she says.

The future is all that really matters. “We have a lot of patriots from all corners of the U.S. who live here,” Ms. Buirski says. “If you don’t look after freedom, you might lose it. And then you can’t get it back.”

Mr. Oakes sees it as a classic battle between two contrasting visions of freedom.

“Florida is a place where it’s individual freedom versus group freedom,” he says. “It’s the real question that divides us. Yes, we have common values. But we are evolving as Americans.”

“Collier County is the freest part of Florida, which makes it the freest place in the U.S.,” says Mr. Oakes. “I can’t think of anywhere else where I could be. It’s like we’re in freedom’s last corner.”

Today’s news briefs

• Ukraine advances, Russia responds: Ukraine’s army chief says troops control nearly 500 square miles of Russia’s Kursk region. Nighttime Russian drone and missile attacks on Aug. 26 struck across Ukraine. A day earlier, a heavy barrage pounded energy facilities.

• Immigrant spouses: A federal judge in Texas issued a temporary pause on the Biden administration’s protections that would allow immigrant spouses of U.S. citizens a path to citizenship.

• Telegram CEO arrested: French prosecutors have arrested Pavel Durov. He was detained in a judicial inquiry opened last month involving 12 alleged criminal violations.

• Sea levels: A report from the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organization says some areas of the Pacific are rising at twice the rate of the global average.

• British pop band reunion: Oasis, known for hits like “Wonderwall” and “Don’t Look Back in Anger,” will tour the British Isles next summer after its 2009 split.

Boko Haram made them child soldiers. Will their communities take them back?

Accepting Boko Haram’s child soldiers back into Nigerian society has been controversial. But advocates say this radical act of compassion is the only way their society can heal.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Abubakar Muktar Abba Contributor

For nearly as long as the Nigerian government has been fighting Boko Haram’s insurgency, which began in the northern part of the country in 2009, it has been urging the group’s fighters to lay down their arms.

But only in the last three years, as Boko Haram has splintered and lost ground, have its members begun to take up this amnesty offer en masse. Today, some 160,000 former fighters and their families have been “reintegrated” into Nigerian society, according to estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

The experiences of former child soldiers, however, point to how complex those efforts can be. Shunned by their communities, many have struggled to find a place for themselves outside Boko Haram’s orbit.

“How could we live alongside those responsible for such pain?” asks Bulami Goni, whose father was killed by Boko Haram.

But advocates for the former child soldiers say it isn’t impossible.

“Kindness always pays,” says Bulama Maina Audu, who works with a group helping these young men return home.

Boko Haram made them child soldiers. Will their communities take them back?

Abba Gana was only 10 years old when Boko Haram insurgents attacked his village in northern Nigeria in 2014. Along with the other boys his age, he was kidnapped and forced to herd the militants’ livestock.

By the time he was 15, Mr. Gana had joined the ranks of the group’s fighters, carrying out raids like the one on his own village.

“Growing up with them, I thought I was fighting for a greater cause,” he says of his time with the group, whose goal is to create a fundamentalist Islamic state. Gradually though, the life of fighting and hiding began to wear him down.

Then one day in 2022, he heard a government radio program urging Boko Haram members to surrender. “They said ... that we are welcome back [to our communities] if we repent,” he recalls.

For the first time, Mr. Gana says, he allowed himself to imagine that he might be able to go home.

For nearly as long as the Nigerian government has been fighting Boko Haram’s insurgency, which began in 2009, it has been urging the group’s fighters to lay down their arms.

But only in the last three years, as Boko Haram has splintered and lost ground, have its members begun to take up this amnesty offer en masse. Today, some 160,000 former fighters and their families have been “reintegrated” into Nigerian society, according to estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

The experiences of former child soldiers like Mr. Gana, however, point to how complex those efforts can be. Shunned by their communities, many have struggled to find a place for themselves outside Boko Haram’s orbit. But their supporters say it isn’t impossible.

“Kindness always pays,” says Bulama Maina Audu, whose nephew was abducted by Boko Haram in 2014, and who now works with a group helping former child soldiers return home.

The transition

In 2013, then-President Goodluck Jonathan announced that Nigeria’s government was offering amnesty to Boko Haram militants willing to leave the group. But it wasn’t until one of Boko Haram’s leaders, Abubakar Shekau, died in 2021, that a large number of fighters began to take up the offer.

Their departure weakened Boko Haram, but it also presented new challenges.

“It has been a struggle to even consider living alongside those responsible for my family’s suffering,” says Lawan Kyari, who lost both his parents and an uncle in attacks by Boko Haram and spent years displaced from his home.

“How could we live alongside those responsible for such pain?” agrees Bulami Goni, whose father was killed by Boko Haram, leaving him responsible for an extended family of 20 people.

For Modu Kura, who was 10 when he was abducted by the insurgents in 2013, the hostility he encountered when he left Boko Haram nearly sent him back to the group.

“Someone once said to me, ‘If you kill a scorpion, the scorplings will come for you, [so] you have to finish them all,’” Mr. Kura says. To his community, he was the baby scorpion that had to be destroyed.

Kindness pays off

Those working with Boko Haram’s former child fighters, however, see learning to live side by side as the only way their society can heal.

“The fears and concerns of the communities they are returning to are completely legitimate, but they can only be addressed through dialogue,” says Oliver Stolpe, UNODC country representative for Nigeria.

To that end, in 2021, UNODC started a program in Nigeria called Strive Juvenile, which helps children abducted by Boko Haram find their way back into society. To date, the organization – which is now run by the Nigerian government – has helped more than 2,500 children leave the militant group.

Former child soldiers must be accepted “without stigmatizing or insulting them,” says Hauwa Rawa Ngala, who once fled her home to escape Boko Haram’s reign of terror. She now works with Strive Juvenile helping the group’s former members return home.

Muhammed Ibrahim, a community leader and member of Strive Juvenile, recalls how Mr. Gana behaved when he first left Boko Haram in 2022.

“His mind was still fixated on Boko Haram; he was secluded and would sometimes start screaming and threatening to carry out attacks,” Mr. Ibrahim recalls.

When the organization realized that Mr. Gana was severely traumatized, members made sure he was never alone, says Mr. Ibrahim, enrolling him in school during the day and in evening Quran classes. Eventually, he made friends and began to feel comfortable in his new life.

“All we want is a peaceful future where we can all live in harmony,” Ms. Ngala says.

This article was produced in collaboration with Egab.

UK’s fight against far-right hate goes online, but does it go too far?

To stop far-right rioting, the United Kingdom is looking to stamp out the sort of online activity that fostered the violence earlier this month. But the legislation that the government might use is under fire for being both too weak and overboard.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Katie Marie Davies Contributor

The persistence of far-right social media groups is a continual source of worry for the U.K. government. Earlier this month, they fanned misinformation about deadly stabbings in Southport, England, into countrywide Islamophobic, anti-migrant riots.

One tool the government is contemplating using to subdue this threat is the Online Safety Act. It requires social media platforms to remove posts containing “illegal material” under U.K. law, such as threats or hate speech. When the act comes into force next year, companies that don’t comply will face fines of up to £18 million or 10% of their global turnover – whichever is higher.

The bill is viewed by leaders dealing with the real-life consequences of online hate and disinformation as a silver bullet to curb the threat of future violence. But it has also been strongly criticized by all sides. Human rights groups warn that the act threatens user privacy and harms free speech. Others believe it does not go far enough.

“I certainly think at the moment there is not enough regulation,” says Isobel Ingham-Barrow, CEO of a think tank specializing in British Muslim communities. “But it has to be specific. ... You have to balance freedom of speech.”

UK’s fight against far-right hate goes online, but does it go too far?

When a wave of Islamophobic, anti-migrant violence swept the United Kingdom at the start of August, far-right social media groups fanned the flames of rioters’ anger. Today, the same channels continue to operate – this time tracing the riots’ aftermath.

“The regime is cracking down on patriots,” a poster on one far-right channel bemoaned, citing the case of a woman who was sentenced to 15 months in jail for telling her local community’s Facebook group, “Don’t protect the mosques. Blow the mosque up with adults in it.”

The persistence of such groups is a continual source of worry for the U.K. government, which is searching for new ways to tackle online extremism. One potential tool is new legislation passed last year with the power to police social media, known as the Online Safety Act.

Though it doesn’t come into force until next year, the bill is viewed by leaders dealing with the real-life consequences of online hate and disinformation as a silver bullet to curb the threat of future violence. But the same legislation has also been strongly criticized by all sides. Human rights groups have repeatedly warned that the act threatens user privacy and harms free speech. Others, such as London Mayor Sadiq Khan, believe the law simply does not go far enough. The result sees the government forced to walk a difficult tightrope above the unknown.

“I certainly think at the moment there is not enough regulation,” says Isobel Ingham-Barrow, CEO of Community Policy Forum, an independent think tank specializing in the structural inequalities facing British Muslim communities. “But it has to be specific, and you have to be careful because it can work both ways: You have to balance freedom of speech.”

Keeping users safe in the U.K.

The white paper that would eventually become the Online Safety Bill was drafted by legislators in 2019. It initially examined ways that the government and companies could regulate content that wasn’t illegal but could pose a risk to users’ well-being – especially children’s.

The effort was timely: When the pandemic hit less than a year later, politicians were able to watch the rapid spread of such disinformation – especially how social media could supercharge its reach – firsthand.

But as months passed, the bill’s remit grew in a bid to fight an ever-sprawling list of potential digital harms. In its final form, the act contains more than 200 clauses. It requires social media platforms to remove posts containing “illegal material” under U.K. law, such as threats or hate speech. When the act comes into force, companies that don’t comply will face fines of up to £18 million or 10% of their global turnover – whichever is higher.

While some of its reforms have been widely welcomed – for example, the legislation will outlaw spreading deep fake and revenge pornography – others are highly divisive.

In one case, websites will be compelled to verify the age of their users in a bid to avoid showing inappropriate content to minors – a requirement that the likes of the Wikimedia Foundation have already said they will be unable to fulfill without violating their own rules on collecting user data.

Another much-discussed clause demands that platforms scan users’ messages for content such as child sexual abuse. As well as being seen as an attack on user privacy, such a requirement, many experts say, is all but impossible for end-to-end encrypted services such as WhatsApp.

Yet concern also remains that the law does not go far enough, particularly if it is to tackle extremist rhetoric. Originally, the act required platforms to remove content seen as “legal but harmful,” such as disinformation that posed a threat to public health or encouraged eating disorders, but this was eventually scrapped.

Some now believe it’s time to reexamine whether requirements could be used to tackle rumors such as those that started August’s far-right rioting. Unrest began to spiral when posts on X falsely claimed that a teenager who killed three children in Southport, England, was a Muslim migrant. The killer was later confirmed to be British-born, with no connection to Islam.

“I think what the government should do very quickly is check whether the Online Safety Act is fit for purpose,” Mayor Khan said in an interview with The Guardian.

Not enough regulation vs. too much

Yet for human rights groups and campaigners who have rallied against the Online Safety Act, such calls to use the law as a one-size-fits-all solution are a cause for concern.

Campaign groups fear that the law’s already all-encompassing remit will cause social media platforms to overmoderate. British media regulator Ofcom, which will be responsible for implementing the law, has not yet released its guidance on how it will judge “illegal content.” Neither does the U.K. have a written constitution outlining free speech protections. The current atmosphere is one of uncertainty.

“If you don’t define what ‘illegal content’ is tightly, companies will err on the side of caution,” says James Baker, campaigns and advocacy manager at Open Rights Group, which promotes privacy and speech online. Because if a platform wrongly leaves something up, it is penalized, but “there’s no punishment in the act for wrongly curtailing free speech.”

Even trying to gauge content’s legality from the existing law throws light on inconsistencies.

“When looking at cases of racial hatred, U.K. law protects against abusive, threatening, or insulting words or behavior. [But] in cases of religious hatred, victims are only protected from threatening words or behavior. There is a disparity in the thresholds for different types of hate,” says Ms. Ingham-Barrow. “The lack of clarity surrounding the definition of harms – far from making the U.K. ‘the safest place in the world to go online’ for Muslims, this bill will do little to protect Muslim communities from Islamophobic abuse online.”

Ultimately, experts stress that they will not be able to assess the full impact of the act until it comes into force next year. “It’s foolhardy to call for the law to be changed before we’ve seen it practiced,” says Mr. Baker.

But legislation designed to crack down on disinformation or hate speech is just one piece of a far larger puzzle.

“So much of what makes people susceptible to disinformation is about both the online and the offline world,” says Heidi Tworek, associate professor of history and public policy at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “It can depend on age, gender, race, your political leaning, the things that a platform’s algorithm shows you and the community you find. We need to go beyond just regulation, and recognize that disinformation has many online and offline causes.”

Tutoring is getting kids excited about school. Educators want to make it permanent.

Educators knew tutoring could help with pandemic-related learning loss. With signs that it is also reducing absenteeism, some in education are wondering how the tool might have a more permanent place in the school day.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Education disruptions during the pandemic triggered a scramble to help students in the United States. Many school districts quickly zeroed in on tutoring – something typically only wealthy families could afford.

When Washington, D.C., schools launched intensive tutoring programs, student achievement improved. And more kids started showing up each day, too. Now, as far as some educators are concerned, results like those are bolstering the case for tutoring as an integral part of public schooling. A key challenge is finding funding.

For Principal Akela Dogbe at Moten Elementary School two things made a difference: The tutors provided a steady presence in children’s lives, and they delivered tailored instruction. If data from the school’s i-Ready assessment software showed a student struggling with division, that’s what the tutoring would address.

At Moten Elementary, 52% of students were learning at grade level for English language arts by the end of this past school year, up from 13% in the 2021-2022 year. In math, grade-level achievement grew from 39% of students to 62%.

“That sense of belonging absolutely made our students feel loved, challenged, and prepared,” the principal says. “They had the adult that they needed to connect with outside of just their teacher.”

Tutoring is getting kids excited about school. Educators want to make it permanent.

When many Washington, D.C., schools launched intensive tutoring programs after the COVID-19 closures, staff observed a pleasant surprise: More kids started showing up each day.

The higher attendance rates – on top of improved math and reading skills – proved a welcome side effect of an initiative aimed at bridging students’ learning gaps.

Education disruptions during the pandemic triggered a scramble to help students in the United States who had fallen behind academically. Many school districts quickly zeroed in on tutoring – from online to in person. It put a strategy once considered a privilege for the wealthy few into the mainstream. Now, as far as some educators and researchers are concerned, results like those in Washington are bolstering the case for tutoring as an integral part of public schooling.

“This is most likely to happen if parents both want this and believe that they can get this – and deserve to get this – at school,” says Susanna Loeb, a professor of education at Stanford University in California.

Amid the flurry of activity in recent years, researchers and policy advocates are increasingly pointing to a specific kind of tutoring as the most effective. Known as “high-impact” or “high-dosage,” it generally refers to tutoring that happens at least three times a week for 30-minute sessions with groups of four or fewer students. And if it occurs during the regular school day? Even better.

“Done right, in-school tutoring raises academic results and builds student-adult relationships that help diminish the sense of isolation that has afflicted many students in the wake of the pandemic,” wrote Liz Cohen, policy director for FutureEd, an education think tank at Georgetown University, in a report released earlier this year. “It has the potential to become a valuable and lasting component of how schools teach students.”

With pandemic relief funds expiring this year, though, districts are left figuring out how to keep such tutoring afloat.

A November report from the National Student Support Accelerator, which Dr. Loeb directs, found that 40 states had provided funding toward tutoring programs. Pandemic-era federal money played a role. The Arkansas Tutoring Corps, for example, launched after state lawmakers passed legislation in 2023. Farther west, New Mexico began a tutoring program initially aimed at helping students in early algebra courses.

“We’ll need to be much more targeted, right, in who we’re serving and how,” says Lewis Ferebee, chancellor of District of Columbia Public Schools.

How has high-impact tutoring leveled the playing field?

In Washington, the high-impact tutoring initiative appears to have leveled the playing field. Tutoring no longer exists solely in the city’s wealthier core. Now, students in a broader geographic area are receiving the academic boost for free at school. The initiative partnered with schools serving a larger number of at-risk students.

Dr. Ferebee cited Moten Elementary School as a case study for how high-impact tutoring can be achieved, given its “baked in” schedule that mostly uses building-based staff members. Shortening transition periods between classes is one way the school carved out enough dedicated tutoring time within the school day.

As a result, every child in kindergarten through fifth grade receives the more intensive tutoring, says the school’s principal, Akela Dogbe. The plan requires an all-hands-on-deck mindset, drawing on the music teacher, librarian, dean, and principals, among others. The school also pulls in extra tutors from partnerships with nearby universities and nonprofits.

With the logistics in place, two things happened that Ms. Dogbe credits with making the difference: The tutors provided a steady presence in children’s lives, and they delivered tailored instruction. If data from the school’s i-Ready assessment software showed a student struggling with division, for instance, that’s what the tutoring would address.

“That sense of belonging absolutely made our students feel loved, challenged, and prepared,” she says. “They had the adult that they needed to connect with outside of just their teacher.”

More than half of D.C. schools, including Moten Elementary, have participated in a high-impact tutoring initiative that began during the 2022-2023 academic year. (A small-scale version started in some District of Columbia Public Schools the year prior.) The initiative involved a three-year, $33 million investment from Washington’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education. The school district also contributed $13 million over the past two years. Implementation differed slightly at each school, officials say, but the takeaway was the same.

Across the D.C. schools providing high-impact tutoring, including charters, students were nearly 7% less likely to be absent on days they had sessions, according to a report that looked at the program’s inaugural year. Additionally, the tutored students narrowed the achievement gap with their peers.

At Moten Elementary, 52% of students were learning at grade level for English language arts by the end of this past school year, up from 13% in the 2021-2022 year. In math, grade-level achievement grew from 39% of students to 62% in that same time frame, according to data from the school’s progress-monitoring i-Ready assessments.

“I have some real mathematicians in my building,” says Ms. Dogbe. She adds that students were requesting additional math problems and worksheets after their tutoring sessions.

The future of tutoring

The FutureEd report notes that spending trade-offs and the acquisition of new state and federal funding streams will be a key part of making tutoring sustainable. But Dr. Loeb of Stanford says she is hopeful districts will make every effort to keep tutoring alive.

“Everyone’s thinking about where they’re going to get the funds,” she says, “but they are really trying to get funds.”

Points of Progress

In sports, the arts, making room for mental health and disabilities

In our progress roundup, there’s more recognition that everyone from athletes to people with disabilities deserves to be accommodated. Sports fans are supporting stars’ taking care of their mental health. And formal venues – from ballet stages to classical music halls – are getting less stuffy to allow enjoyment by more patrons.

In sports, the arts, making room for mental health and disabilities

American fans are becoming more accepting of athletes who discuss their mental health

Though an estimated one-third of elite athletes have mental health concerns such as depression, many fear they could face rejection from fans, colleagues, and sponsors if they talk about their struggles.

In a 2022 study, researchers analyzed social media posts responding to tennis star Naomi Osaka’s decision to withdraw from the 2021 French Open for mental health reasons. They found that 51% of posts supported her decision, while only 19% were negative. More recently, a study found that fans felt just as favorably toward athletes who took time off to address mental health concerns as those who did so for physical injuries.

Stories shared by elite athletes “have helped the public recognize that these admired athletes are just as vulnerable to mental health conditions as anyone else,” wrote Professor Dae Hee Kwak of the University of Michigan. (Read more about Olympians advocating for broader public discussion and support of athletes’ mental health here.)

Sources: The Conversation, McLean Hospital

To protect animals raised for food, the U.K. Parliament bans live exports

Live farm animals intended for slaughter are often shipped on long journeys, enduring stress, overcrowding, and dehydration. European Union regulations had prevented the United Kingdom from passing a blanket ban. The law, enacted by former Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government, does not include Northern Ireland due to trade agreements following the country’s exit from the EU.

Though by 2012 only one British port still allowed live exports, the new legislation is the culmination of nearly 50 years of activism. In 1995, activists blockaded sea and air routes to halt the exports; fierce protests roiled the small English town of Brightlingsea for 10 months. Since 1960, nearly 40 million animals have been exported from the U.K.

This year, Australia began a four-year phaseout of the live export of sheep by sea.

Sources: Agence France-Presse, The Humane Society of the United States, Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

Solar power that depends less on public utilities is expanding in Africa

Some 600 million people on the continent, virtually all in sub-Saharan Africa, do not have electricity.

But in 2023, Africa added a record-breaking 3.7 gigawatts of photovoltaic power. While South Africa is notorious for rolling outages, or “load-shedding,” it leads the new charge, having increased its solar capacity from 2.8 gigawatts to 7.8 gigawatts in two years. The solar boom is driven in part by an ongoing drop in the cost of solar panels and the expansion of “minigrids” owned by private firms.

Minigrids also create jobs: In Kenya, such systems employ six times as many people as the largest utility, and in Nigeria, they have created nearly as many jobs as in oil and gas. In April, the World Bank and the African Development Bank announced a project to expand electricity access in sub-Saharan Africa to 300 million people by 2030.

Sources: The Economist, Africa Solar Industry Association

Thai officials use satellite and drone data to help farmers decide when it’s safest to burn fields

In a compromise between strict fire bans and the burns that sometimes make Chiang Mai the most polluted city in the world, local officials are encouraging use of a system that’s intended to exert some environmental control without jeopardizing livelihoods.

The need for this balance led to the creation of FireD, an app that allows farmers to submit requests to burn. Local atmospheric conditions are used to decide on a case-by-case basis if a blaze will have too much impact on pollution levels. In the most recent burning season, the number of days with dangerous levels of particulate matter fell by 24%.

Because some farmers lack internet access, they must submit written requests instead of using the specially designed app. Some avoid the system because it doesn’t allow enough scheduling flexibility. But local leaders are focused on increasing communication to encourage adoption by farmers. FireD received 14,000 burn requests in 2024.

Source: Grist

Fine arts organizations are putting on sensory-friendly shows to build audiences

From Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, to the Queensland Ballet, to the Philadelphia Ballet, companies are featuring modified performances and looser theater rules for neurodivergent children and people who would appreciate a “relaxed” format. Theaters lower sound volume, dim lights rather than darkening them completely, and allow people to move around as they need. Les Grands Ballets offers “quiet zones” where people can go if they’re feeling overwhelmed.

ROCO (River Oaks Chamber Orchestra) in Houston emphasizes multigenerational accessibility and innovation in classical music. It offers child care at certain shows so that parents can bring children who attend a portion of the performance. “We’re all about making ‘human-first’ decisions,” said Alecia Lawyer, artistic director for the orchestra. “The people who make the art and the people who experience it are at the core of our vision.”

Sources: Canadian Broadcasting Corp., ArtsHub, Queensland Ballet, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A familylike equality in Bangladesh

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One of the world’s most poignant scenes in August was that of students in largely Muslim Bangladesh guarding places of worship for the country’s religious minorities, mainly Hindus. A student movement, organized to bring about equality in job hiring, had ousted a dictator Aug. 5 and then extended its embrace of civic equality by protecting Hindus from violent persecution by radicals during a period of political chaos.

The attacks on Hindus have largely ended, but the head of the new interim government, Nobel Peace laureate Muhammad Yunus, has continued a drive for peace by visiting a Hindu temple Aug. 14. He delivered this message: “I am here to say we are all equal. ... In our democratic aspirations, we should not be seen as Muslims, Hindus, or Buddhists, but as human beings.”

As he prepares his South Asian nation for free and fair elections, Dr. Yunus – globally famous for creating a system of microloans for poor people – keeps setting a model of inclusiveness. So far, both he and the student antidiscrimination movement that brought him to power are getting it right: “Equality” is really a verb, not a noun.

A familylike equality in Bangladesh

One of the world’s most poignant scenes in August was that of students in largely Muslim Bangladesh guarding places of worship for the country’s religious minorities, mainly Hindus. A student movement, organized to bring about equality in job hiring, had ousted a dictator Aug. 5 and then extended its embrace of civic equality by protecting Hindus from violent persecution by radicals during a period of political chaos.

A new interim government also set up a hotline for people to report attacks on religious institutions. “Bangladesh is a country of communal harmony,” said a new religious affairs official, Dr. A.F.M. Khalid Hossain. “There is no problem in observing [Muslim] fasting and [Hindu] puja at the same time in this country.”

The attacks on Hindus have largely ended, but the head of the new interim government, Nobel Peace laureate Muhammad Yunus, has continued a drive for peace by visiting a Hindu temple Aug. 14. He delivered this message:

“I am here to say we are all equal. ... In our democratic aspirations, we should not be seen as Muslims, Hindus, or Buddhists, but as human beings.”

“Do not make distinctions among us,” he said. “Exercise patience and judge us later – what we were able to do and what we couldn’t. If we fail, criticise us.”

As he prepares his South Asian nation for free and fair elections, Dr. Yunus – globally famous for creating a system of microloans for poor people – keeps setting a model of inclusiveness, from the diverse makeup of his interim Cabinet to his assurance of support for the world’s largest camp of refugees.

An estimated 1.3 million mainly Muslim Rohingya who fled persecution in Buddhist-majority Myanmar live in a Bangladeshi settlement near the town of Cox’s Bazar. Dr. Yunus told foreign diplomats Aug. 18 that he will back ongoing humanitarian aid to the camp and work with other countries to eventually return the refugees to their homeland “with safety, dignity and full rights.” He has long been a champion for the Rohingya and is well known for urging people to break down the walls of prejudice based on religion, place of birth, or ethnicity.

He has also promised Bangladeshis that they would live as a family with no room for discrimination. So far, both he and the student antidiscrimination movement that brought him to power are getting it right: “Equality” is really a verb, not a noun.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Watered flower

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Kit Cornell Kurtz

As God’s children, entirely spiritual, we’re created to thrive, as this poem conveys.

Watered flower

O wilted flower

– ground so parched

you can no longer

lift your face

to the glory

of the sun –

realize the rain

has come.

God’s tender hand

has given floods

of love,

water for growth,

water for healing,

strength to lift

your head

and see

the ever-present

light of Life –

Spirit guiding,

Truth providing.

You’re not a flower

of earth and mud –

the myth of mortality.

A perfect seed,

by God conceived,

you’re planted by Love’s

gracious hand.

All spiritual,

you’re Mind’s idea,

by Life lit bright –

held fast and

blessed by Soul.

No need to face

the dirty ground.

Love is here – all around.

Let your beauty shine –

reflected glory

always thine.

Your ground is watered.

God’s blessings flow.

Grow!

Viewfinder

With the greatest of ease

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll look at a first-in-the-country project: a major public utility that has joined with environmental activists to create a geothermal pilot program.