- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- What the pager attack in Lebanon means for Israel-Hezbollah conflict

- Today’s news briefs

- Could Fed’s aggressive rate cut change the election?

- How an overlooked county landed the new FBI headquarters and tech jobs

- Latin America’s populist prototype: Peru’s Fujimori leaves divisive legacy

- A bittersweet farewell: I’m a New Yorker, but Mississippi has my heart

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A welcome return

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today, I want to draw your attention to a name we are very glad to see back on our pages. Dina Kraft has written for us before. It was a natural fit. She is deeply involved in building understanding across divisions in Israel. Several years ago, she participated in a Monitor webinar on respect in the middle of a rocket attack.

After working for an Israeli newspaper and on a book about Anne Frank for a few years, she is writing for us again. Today’s article follows her memorable collaboration with Ghada Abdulfattah to show the cost of the war in Gaza on both sides of the border.

She tells me, “Now, more than ever, as I look around myself in a region that feels so broken, I see the Monitor mission as a gift to pursue – to report on those people thinking differently about how to approach the seemingly intractable problems that surround us.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What the pager attack in Lebanon means for Israel-Hezbollah conflict

In Lebanon, exploding pagers and booby-trapped walkie-talkies – believed to be set off by Israel – have rattled Hezbollah and captured the world’s attention. What do they portend?

Hezbollah has blamed Israel for an attack on Tuesday in which pagers belonging to its members exploded across Beirut and southern Lebanon, injuring nearly 3,000 people. On Wednesday afternoon, another set of low-tech wireless devices including walkie-talkies exploded in Lebanon, reportedly killing nine.

Since Oct. 7, towns along Israel’s northern border have been under near-constant attack by the Iran-backed militant group, while Israeli airstrikes on Hezbollah positions in Lebanon are making life impossible for civilians there. Yet each side has been wary of full-scale war, instead maintaining an uneasy equilibrium.

Now, in the wake of this week’s events, people on both sides of the border are wondering what comes next.

The attacks exposed vulnerabilities in Hezbollah’s efficacy and disrupted communications. In theory, this would be a strategic time for Israel to launch a broader offensive in Lebanon, and, indeed, officials have suggested that Israel’s military focus is shifting north from Gaza.

But Eyal Zisser, vice rector of Tel Aviv University, remains skeptical.

“The [Israeli] government does not know what to do about Gaza,” he says. “Does one give them credit that they will know what to do with Lebanon?”

What the pager attack in Lebanon means for Israel-Hezbollah conflict

As news broke Tuesday that pagers belonging to Hezbollah members were exploding across Beirut and southern Lebanon, injuring nearly 3,000 people, Israeli TV drama writer Avi Issacharoff turned to the social media platform X.

The co-creator of the hit TV series “Fauda,” about undercover Israeli operatives, posted that writers were working on another season, but “Nothing comes close to what’s currently happening in real life.”

Hezbollah has blamed Israel for the audacious, technically impressive attack, unprecedented in its scope, impact, and complexity.

But the question exercising people on both sides of the Israel-Lebanon border is much simpler: What might come next? Heightened tensions, spiraling retaliation, a wider war?

The first indication that Tuesday’s operation was more than a one-off move came Wednesday afternoon, when another set of low-tech wireless devices, among them walkie-talkies, exploded in Lebanon, reportedly injuring over 100 people and killing nine.

“If this is the beginning of a series of moves, you could say it was done to prepare for a larger offensive” against Hezbollah by destroying one of its communications networks, suggests Yaakov Katz, a senior fellow at The Jewish People Policy Institute, a Jerusalem think tank, and author of “The Weapon Wizards: How Israel Became a High-Tech Military Superpower.”

If the goal is more limited, he argues, “You need to ask what it achieves. And what it potentially achieves is that it shows Hezbollah is vulnerable and weak, and hopefully it boosts deterrence” against retaliation.

For the past 11 months, villages and towns along Israel’s northern border with Lebanon have been under near constant Hezbollah rocket and drone attacks, launched on the heels of Hamas’ Oct. 7 assault on Israel. Forests are ablaze, and almost 70,000 residents of the north, evacuated to safer places, have been unable to go home. Pressure for their return is mounting, fueling advocates of an invasion of Lebanon to push Hezbollah forces back.

At the same time, Israeli airstrikes on Hezbollah positions in southern Lebanon are making life impossible for civilian residents. But to date, both sides have managed an uneasy equilibrium of tit-for-tat warfare, each wary of full-scale war that could prompt a catastrophic level of devastation.

Tuesday’s and Wednesday’s events not only are a “symbolic blow” to Hezbollah, a radical Shiite Muslim organization backed by Iran, said Peter Harling, a former analyst with the International Crisis Group, in a post on X. They also exposed vulnerabilities in what was thought to be the group’s “efficacy, and an almost airtight community,” he wrote.

“Such a moment of destabilization is not one in which Hezbollah is likely to escalate the war. You don’t raise the stakes when your communications are disrupted and your ranks disoriented,” he argued. “For Israel, however, this in principle is the best timing to broaden its scope.”

Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant indicated on Wednesday that Israel’s military focus is shifting north from Gaza, as negotiations for a cease-fire deal to release over 100 hostages appear to have stalled.

“The center of gravity is moving northward – resources and forces are being allocated” to the northern front, he said. “We are at the start of a new phase in the war – it requires courage, determination, and perseverance on our part.”

A division of the Israeli army has been withdrawn from Gaza and redeployed in the north, Israeli media reported Wednesday. On Monday evening, the Israeli Cabinet made the return home of displaced citizens an official war goal.

But some observers remain skeptical about Israel’s intentions.

“What would Israel do in a broader war with Lebanon?” wonders Eyal Zisser, vice rector of Tel Aviv University. “The government does not know what to do about Gaza. Does one give them credit that they will know what to do with Lebanon?”

“If you are thinking about escalating, you need a purpose, a political goal, and [the government’s] goal is to survive politically,” he says.

“It’s highly impressive, what happened” in Lebanon, he acknowledges. “But it is not how you win a war.”

Today’s news briefs

• Baltimore bridge collapse lawsuit: The U.S. Justice Department is suing the owner and manager of the cargo ship that caused the Baltimore bridge collapse in March.

• California AI law: Gov. Gavin Newsom signs legislation to protect Hollywood actors and performers against unauthorized use of artificial intelligence.

• Instagram teen accounts: The social media platform will offer separate accounts for those under age 18 as it tries to make the platform safer for children amid a growing backlash against how social media affects young people’s lives.

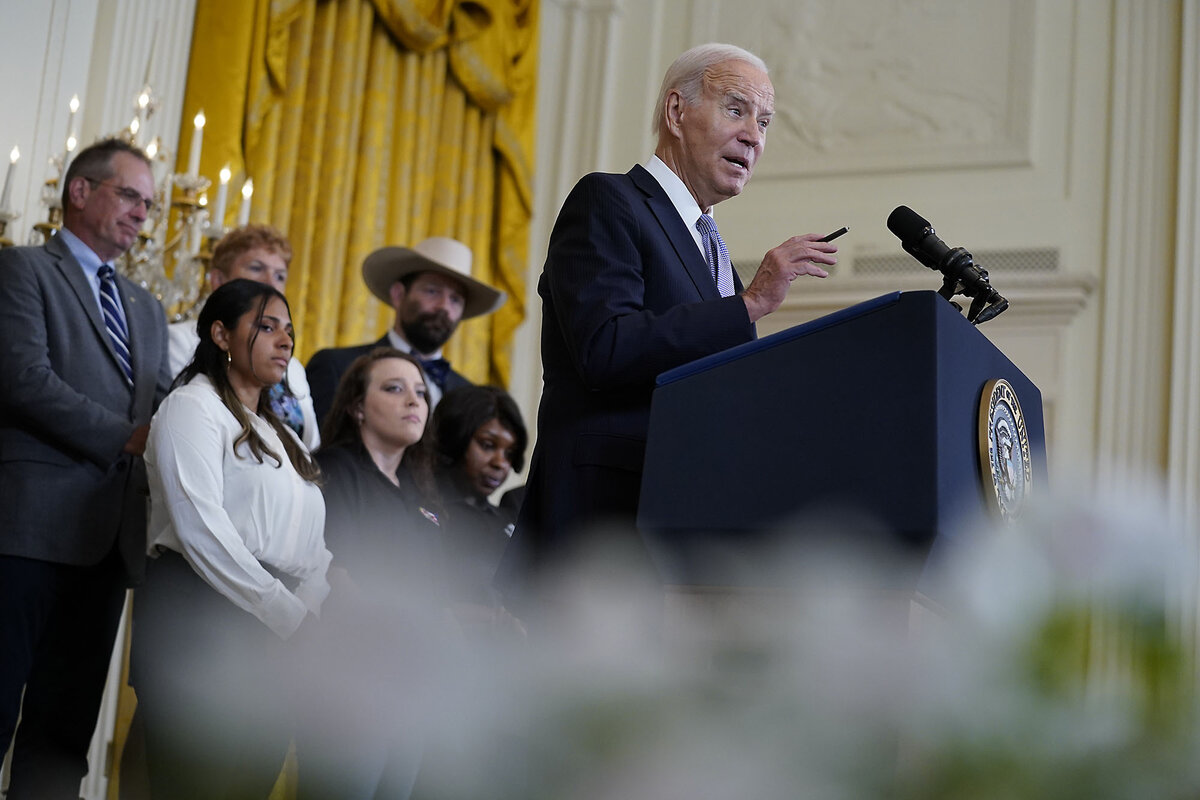

Could Fed’s aggressive rate cut change the election?

The state of the economy influences elections. Will voters look backward to inflation under President Joe Biden or forward to hopes of finding tamer prices and avoiding a recession?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

If the U.S. presidential race can be likened to a regatta, Vice President Kamala Harris’ sailboat just caught an extra gust of wind.

It comes courtesy of the nation’s central bank. On Wednesday, for the first time in four years, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates, promising to make it a little cheaper for Americans to borrow money to buy a car, finance some home loans, or start a business. Combined with other signs of a brightening economy, the Fed’s half-point move could spell the difference in a very close race for the White House.

The Fed says its rate cut and timing have nothing to do with politics or the election. But will voters look forward, and credit Ms. Harris with how inflation has improved this year? Or will they look backward to compare the economic records of Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden?

Voters do both. And both administrations have had mixed results on economic policy.

One of the paradoxes of this election year is that the economic data has so far proved more upbeat than consumer sentiments.

“There’s a lag,” says Michael Lewis-Beck, a University of Iowa professor who studies economic perceptions’ impact on voting. “It takes time for the numbers to sink in.”

Could Fed’s aggressive rate cut change the election?

If the U.S. presidential race can be likened to a regatta, Vice President Kamala Harris’ sailboat just caught an extra gust of wind.

It comes courtesy of the nation’s central bank. On Wednesday, for the first time in four years, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates, promising to make it a little cheaper for Americans to borrow money to buy a car, finance some home loans, or start a business. Combined with other signs of a brightening economy, the Fed’s half-point move could spell the difference in a very close race for the White House.

Low gasoline prices, falling mortgage rates, and the rise in incomes even after adjusting for inflation suggest an Election Day win by Vice President Harris “by an eyelash,” forecasts Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, whose firm has been tracking the economies of swing states to predict the election. But economic conditions can shift suddenly before November, he warns. “These winds are very, very thin – again, a few thousand, tens of thousands of votes” in each of those key states.

The half-point rate cut comes as something of a surprise. Stock markets shot up immediately. As an independent entity, the Federal Reserve tends to move incrementally with quarter-point moves, and it has repeatedly stressed that its moves to keep the economy from growing too fast or too slow have nothing to do with politics or the election. It has made even bigger rate cuts in election years, most notably in October 2008 as the financial crisis deepened, and then again in March 2020 when the pandemic triggered a sharp recession.

But Wednesday’s move comes without an obvious economic emergency. Fed Chair Jerome Powell defended the move at a press conference, saying that as the risks of inflation have lessened, the risks of a slower economy and higher unemployment have risen.

“The upside risks to inflation have diminished and the downside risks to employment have increased,” Mr. Powell said.

Small changes in financial conditions matter because voters have consistently tagged the economy as their top concern. And while most voters long ago made up their minds, a sliver of the electorate has yet to make a choice. Their perception of the economy could seal the election.

Will voters look forward or backward on inflation?

A key question is, Will voters look forward, essentially, and credit Ms. Harris with how inflation has improved this year? Or will they look backward to compare the economic records of Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden?

Voters do both, of course, says Michael Lewis-Beck, a professor of political science at the University of Iowa who has studied economic perceptions and their impact on voting. But mostly they look backward, especially at what’s happened during the 12-month run-up to Election Day. And this is crunch time, because the period after the conventions is when many voters focus on the election and their views on the economy solidify, he adds.

One of the ironies is that voters tend to judge a president on things over which they have little control. Take gasoline prices, the most important determinant in voter perceptions of the economy, says Mr. Zandi. If gas costs $4 a gallon, Mr. Trump wins; if it’s closer to $3 a gallon, Ms. Harris wins. Nationally, gas prices sit at an average of $3.20 and look to be headed lower.

Presidents have almost no sway over gas prices. Even a release from the nation’s strategic oil reserve could be swamped at any time by a decision by OPEC.

The second most important factor for voters – mortgage rates – is influenced by the Federal Reserve, not the White House. But that influence can be indirect. In anticipation of a rate cut, mortgage rates have already fallen more than a percentage point since May, making it cheaper to borrow to buy a house.

Both candidates have mixed economic records

This election year is unusual because voters can compare the economic records of both candidates. And any objective look suggests mixed success. Mr. Biden and, by extension, Ms. Harris win on jobs and economic growth. But American households saw much lower inflation under Mr. Trump. And inflation-adjusted household income – voters’ third most important metric, according to Mr. Zandi – grew by about 4% under Mr. Trump before the pandemic. Under Biden-Harris, it only recently turned positive and has grown less than 1%.

The pandemic, however, complicates comparisons. Mr. Trump’s jobs record would look far less paltry if the pandemic hadn’t triggered a recession in the last year of his administration. Inflation, which reached four-decade highs under Biden-Harris, would have proved far tamer had Presidents Trump and Biden not pushed through trillion-dollar stimulus packages to stave off that pandemic-era recession.

Even signature economic achievements of both former President Trump and President Biden have met with mixed success. Mr. Trump’s 2017 tax cut package helped increase income for some 80% of households, even for many of those that don’t pay federal taxes, points out Kyle Pomerleau, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank.

But the biggest benefits went to rich people, who were helped not only by the fall in individual rates but also by the big reduction of the corporate tax rate, which benefited company owners and stockholders, he adds.

Tax cuts, tax incentives, and missed opportunities

While the cuts provided a short-term boost to the economy, they added $1 trillion or more to the federal debt, says Robert Bixby, executive director of The Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan organization that encourages federal fiscal responsibility.

By contrast, Mr. Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act – which among other things gave tax incentives to green energy projects, allowed Medicare to negotiate drug prices, and modernized the IRS – was designed not to add to the overall federal debt. But the benefits of its pro-growth investments have been offset somewhat by anti-growth tax increases, Mr Pomerleau says, which makes its long-term economic impact ambiguous.

Also, both presidents’ policies included wasteful excesses and didn’t take advantage of opportunities to use federal funds more efficiently, says Clifford Winston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

Polls give Harris an edge on economy

Until recently, more Americans trusted Mr. Trump than the current administration with the economy. In May, an Ipsos/ABC News poll found the Republican front-runner had a 14-point advantage over President Biden (46% to 32%).

But some polls suggest that in recent weeks, the Democrats’ nominee, Vice President Harris, has neutralized that advantage. A Financial Times/University of Michigan poll released Friday reported she had a slim advantage over the former president on the economy: 44% to 42%.

Similarly, polling firm Redfield & Wilton Strategies found that after trailing Mr. Trump on the economy by 6 percentage points or more in nine swing states in July, Ms. Harris now leads by slim margins in three of those states and is tied in two others.

One of the apparent paradoxes of this election year is that the economic data has so far proved more upbeat than consumers.

“There’s a lag,” says Professor Lewis-Beck at the University of Iowa. When “the growth rate comes out and the unemployment rate comes out, people don’t immediately get up in the morning and say, ‘Hey, the number went up!’”

He adds, “It takes time for the numbers to sink in.”

How an overlooked county landed the new FBI headquarters and tech jobs

Like many places, Prince George’s County, Maryland, struggled during the pandemic. As a majority-Black community, it has also faced historic discrimination. Yet it has emerged as an economic bright spot.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Vennard Wright promotes the two companies he founded in the past four years, he also touts how he’s developing tech talent in his home county – a place that’s overcome obstacles to establish itself as one of Maryland’s strongest growth engines.

The change in Prince George’s County is obvious to people who’ve long lived and worked in this majority-Black community bordering Washington, D.C., and the Potomac River. The county has nearly completely recovered from the considerable job losses caused by the pandemic and rebounded from the Great Recession, when it had the highest foreclosure rate in the state.

Signals of the county’s revitalization range from splashy announcements, like the FBI last year picking Prince George’s as the site of its headquarters, to ambitious infrastructure projects, like plans for 10 additional metro subway stations. Between 2011 and 2021, the county led the state in job growth. The county’s rapid recovery could provide some models for other communities.

“This growth is not by accident,” says David Iannucci, president and CEO of the Prince George’s County Economic Development Corp., pointing to efforts by the county and state to stimulate jobs, training opportunities, and federal funding.

How an overlooked county landed the new FBI headquarters and tech jobs

When Vennard Wright promotes the two companies he founded in the past four years, he also touts how he’s developing tech talent in his home county – a place that’s overcome obstacles to establish itself as one of Maryland’s strongest growth engines.

The change in Prince George’s County, Maryland, is obvious to people who’ve long lived and worked in this community bordering Washington, D.C., and the Potomac River. The county has nearly completely recovered from the considerable job losses caused by the pandemic and rebounded from the Great Recession, when it had the highest foreclosure rate in the state.

Prince George’s, with a population of almost 1 million people, is also America’s second-wealthiest majority-Black county – just recently surpassed by neighboring Charles County – but businesses and people here struggled during the pandemic, like the rest of the country. The county’s rapid recovery could provide some models for other communities.

“This growth is not by accident,” says David Iannucci, president and CEO of the Prince George’s County Economic Development Corp., pointing to efforts by the county and state to stimulate jobs, training opportunities, and federal funding.

Signals of the county’s revitalization range from splashy announcements, like the FBI last year picking Prince George’s as the site of its headquarters, to ambitious infrastructure projects, like plans for 10 additional Metro subway stations. Between 2011 and 2021, the county led the state in job growth.

A combination of federal dollars and the prevalence of solopreneurs – people who individually own and operate a business – created a renaissance in the county over the last several years, says Mr. Wright, a lifelong resident of Prince George’s. He has worked with a county workforce development group to help him hire interns and young people interested in working in information technology.

Emerging from setbacks

Coming out of the 2007-2009 recession, Prince George’s County faced the highest rate of foreclosures in the state and was recovering more slowly than its neighbors, says Mr. Iannucci. In the years that followed, county officials and community leaders, including the County Council, focused on a strategic plan that incentivized business growth, adding 50,000 new jobs throughout the 2010s. These efforts were propelled by a number of training programs – mostly paid for by federal funding – offered to county residents focusing on how to run businesses.

Resources have included artificial intelligence training, small grants toward marketing and technology costs, and specific trainings with focuses like navigating government contracting.

Prince George’s County has a lot of things going for it, from public transportation to an educated population to proximity to Washington, says Dan Reed, director of regional policy for Greater Greater Washington, a policy and news organization focused on the region. The broader region is expensive – the median home price in neighboring Montgomery County is $600,000 – and there’s only so much room to expand. But Prince George’s County also has development opportunities, says Reed, like a medical center that’s under construction.

Historically, many members of the community felt Prince George’s was often passed over for investment and development opportunities. Local organizers point to a long and complicated history of racist policies, including housing segregation and delayed school integration, as a partial explanation.

Prince George’s became a majority-Black county in the early 1990s as people with jobs in Washington looked to move out of the city to the suburbs, and the community is now 60% Black with a growing Hispanic population as well.

“Probably the majority of the county’s citizens would tell you that they don’t think that they’ve been fairly treated when it comes to quality retail, and when it comes to major employers,” says Mr. Iannucci. “There’s an investment gap in the Washington region when it comes to Prince George’s County.”

Maryland officials also raised equity arguments during and after their bid to woo the FBI headquarters across the border from Washington.

A 2023 report from Urban Institute found that investment has not been evenly distributed across the Washington region. In particular, average investment per household in Prince George’s County is significantly lower than in other area counties.

New business applications double

Leading up to the 1970s, the county’s economy was primarily agricultural, says Brittney Drakeford, an urban planner with the National Capital Planning Commission and county native. After reshaping as a residential community, a flood of initiatives and projects over recent decades have helped usher the county into a competitive economy.

One of the most prominent efforts, a waterfront development called National Harbor, opened in 2008, with a conference center, casino, hotels, retail shops, and a distinctive 180-foot Ferris wheel on the banks of the Potomac.

The number of new business applications in the county more than doubled between 2012 and 2022, according to U.S. Census data. That increase far surpassed that of neighboring Montgomery County, one of the state’s most affluent places, which saw about a 50% increase during the same period.

Prince George’s also continues to draw investment in business and infrastructure, said Angela Alsobrooks, the county executive, touting both points at a state of the economy address in June.

“These investments show that Prince George’s County is the economic engine of the state of Maryland,” said Ms. Alsobrooks, who is also Maryland’s Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate.

Though there are promising signs of growth, county officials continue to face the tax revenue challenge stemming from Prince George’s historical identity as a bedroom community rather than as a part commercial, part residential community. And county leaders remain concerned that the commercial tax revenue lags behind other nearby counties.

Supporting Black-owned businesses

Funding dedicated to boosting business owners has fluctuated recently, says Mr. Wright, a chief information officer for the county before he started Wave Welcome, a technology and digital services firm in 2020 and, in 2023, PerVista, a business that uses AI to prevent school shootings.

As a majority-Black county, Prince George’s “was very affected by George Floyd,” says Mr. Wright, referring to the 2020 protests against police brutality. “Lots of money flowed down,” says Mr. Wright – including from a $49.5 billion collective pledge from America’s 50 largest corporations.

Over time, that influx of money petered out. Across the United States, about 3% of businesses are Black-owned, and venture capital investment in Black businesses dropped about 70% in 2023, reports the data firm Crunchbase. Maryland has the third-highest share of Black-owned businesses in the country, after Washington, D.C., and Georgia, according to Pew Research Center.

Though Mr. Wright doesn’t see much new investment in startups this year, there are plenty of consulting and government contracting opportunities in the county, he says.

County organizers see economic success as working in concert with social progress. And, Ms. Drakeford adds, current growth is “part of a long trajectory” that has ebbed and flowed through different county administrations.

“This isn’t just about a county catching up. This is about righting wrongs, in a way,” says Reed of Greater Greater Washington. “This region has this huge Black middle class that hasn’t always had access to the same simple things like retail opportunities or access to jobs that other communities take for granted” – all of which limited the potential for economic growth.

A growing tech sector

Among the sectors experiencing growth today is tech. Blink Charging, a company that sells and operates electric vehicle chargers, is one company that recently expanded in Prince George’s County.

After considering many different states, “Maryland and Prince George’s County was one of the few that was very, very welcoming to us in terms of providing some incentives and grants, but also in terms of where they would fast track some of our manufacturing capabilities,” says Harjinder Bhade, chief technology officer of Blink.

The company decided to build its headquarters in Prince George’s, and added a 30,000-square-foot manufacturing plant. Along with having space to grow in the future, says Mr. Bhade, the county offers proximity to government agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency.

Editor's note: This story, originally published on Sept. 18, has been changed to correct Brittney Drakeford's job title.

Latin America’s populist prototype: Peru’s Fujimori leaves divisive legacy

Former President Alberto Fujimori had been out of office for more than two decades when he died. But his legacy – from economic “Fuji-shocks” to human rights abuses – still divides Peru today.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Mitra Taj Contributor

Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, a prototype of a populist authoritarian leader that would be replicated in Latin America for decades, was buried in Lima with state honors over the weekend. He died on Sept. 11.

Mr. Fujimori is widely credited with rescuing Peru from a painful period of hyperinflation and hunger in the 1990s, and oversaw the dismantling of leftist insurgent groups that terrorized Peruvians with car bombs and brutal massacres for more than a decade.

Many of his supporters revere him for delivering aid and basic infrastructure to long-neglected rural regions. "Fujimori gave us electricity, and oh, what joy!” remembers Michael Santa Cruz, who grew up in northern Peru.

But Mr. Fujimori's hold on power was riddled with authoritarian power grabs, corruption, and human rights abuses.

“He died without asking for forgiveness from his victims,” says Rosa del Carmen Reátegui, one of hundreds of mostly Indigenous and poor women in Peru who say they were forced or tricked into sterilization by Mr. Fujimori’s family planning program.

Today, his legacy in Peruvian politics persists, with a right-wing political movement bearing his name still making waves.

Latin America’s populist prototype: Peru’s Fujimori leaves divisive legacy

He was a populist outsider who shocked the world by defeating the establishment favorite in a presidential election. In office, he ran roughshod over institutions and human rights, dividing a nation. And despite multiple criminal convictions, his legacy has continued to play an outsize role in politics.

Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, prototype of a populist authoritarian leader that would be replicated in Latin America for decades, was buried in Lima with state honors over the weekend. He died on Sept. 11.

During the three-day public wake in Lima, thousands of Peruvians lined up to get a last glimpse of a right-wing leader who marked a clear dividing line in Peru’s tumultuous history. Even today, some 24 years since he fled office amid widespread protests, his eponymous political movement, Fujimorismo, is influential at all levels of government.

While protesters shouted “assassin” and “corrupt” as his casket was escorted by police vehicles to the presidential palace for a red-carpet farewell from President Dina Boluarte, others queued for hours to bid teary goodbyes. “This is a demonstration of the gratitude the Peruvian people feel,” says Fortunato Lagura, a business administrator, as he waited for more than two hours for his turn to pay his respects.

The “myth” of Fujimori

Mr. Fujimori was born in Lima to Japanese immigrants and was a young child during World War II, when Peru’s large Japanese diaspora was persecuted. He became an agricultural engineer, then a university rector, and swept to power with left-wing support in 1990 after campaigning aboard a tractor with the slogan “Honor, technology, work.” He defeated Mario Vargas Llosa, a white free marketeer who would go on to win a Nobel Prize in literature.

He is widely credited with rescuing Peru from a painful period of hyperinflation and hunger, and oversaw the destruction of leftist insurgent groups that terrorized Peruvians with car bombs and brutal massacres for more than a decade.

He had a knack for showmanship that earned him the respect of Peruvians who were fed up with years of lawlessness and inaction – calmly announcing that he was sending the military to take over Congress and the courts in 1992, and proudly walking over the dead bodies of defeated insurgents who took hostages at the Japanese ambassador’s residence in 1996.

Many of his supporters revere him for delivering aid and basic infrastructure to long-neglected rural regions. “He was never just sitting here in Lima. He was in the provinces with the poor people,” says Michael Santa Cruz, a computer technician from northern Peru. Mr. Santa Cruz was 7 ears old when Mr. Fujimori strode into his elementary school and distributed food, clothes, and school materials. Soon, he says, his small town of Chongoyape had two new school buildings, paved roads, and electricity.

“We used to use kerosene lamps at night. Fujimori gave us electricity, and oh, what joy!” Mr. Santa Cruz recalls. “We could have refrigerators.”

But he also created an archetype for authoritarian populism in a democratic setting that is still emulated today, says Gonzalo Banda, a Peruvian political scientist. Long before Javier Milei promised austerity for Argentina or Nayib Bukele packed half-naked prisoners into a jail in El Salvador, Mr. Fujimori delivered the “Fuji-shock” that breathed life back into Peru’s economy and put insurgents in cages to display before the press.

“He was Milei before Milei. Bukele before Bukele. Chávez before Chávez,” says Mr. Banda, referring in the last case to Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. “He was a proto-populist, and that’s why his legacy will continue to be defended, especially by the right. They need his myth.”

Mr. Fujimori’s two terms in office were riddled with authoritarian power grabs, corruption, and human rights abuses. After videos of his spymaster Vladimiro Montesinos bribing lawmakers, businessmen, and journalists with stacks of cash were made public in 2000, Mr. Fujimori fled growing protests for Japan, sending his resignation via fax.

“Fujimori was a forerunner of a type of politician who comes to power through the democratic process, but who undermines institutions from the executive branch,” says Mauricio Zavaleta, a Peruvian political scientist. “He had to play by certain democratic rules, but he gradually broke” them.

In 2009, Mr. Fujimori was sentenced to 25 years in prison for the paramilitary massacres of 25 civilians during a ruthless counterinsurgency campaign. He was also convicted for corruption, embezzlement, usurpation of powers, espionage, and the kidnapping of a journalist. He was Peru’s first former president to be imprisoned in what were widely seen as fair trials, earning Peru international acclaim for fighting impunity.

A number of trials and investigations for other crimes were still pending when he died.

“He died without asking for forgiveness from his victims,” says Rosa del Carmen Reátegui, one of hundreds of mostly Indigenous and poor women in Peru who say they were forced or tricked into sterilization by Mr. Fujimori’s family planning program.

“He was never convicted for our sterilizations,” Ms. Reátegui says. “Fujimori has left us with endless trauma, pain, physical, and psychological suffering, and the continuous struggle to find justice and reparations for the harm caused.”

Peru’s divides

Part of Mr. Fujimori’s lasting political influence is due to the failure of other political leaders and parties to forge a lasting connection with voters in Peru. And many have been tainted with criminal probes of their own. Most of the presidents since Mr. Fujimori have come under investigation for corruption or human rights abuses.

“Fujimori was corrupt. I don’t doubt it,” says José Orizano, a taxi driver in Lima. “But so are all the rest. At least he did something for Peru.”

Regardless of individual opinions about the former president, Fujimorismo is still very much alive. The right-wing populist movement has reemerged as a political force in recent years, gaining influence in key institutions – Congress, the presidency, Peru’s top court, and the ombudsman’s office.

His daughter Keiko Fujimori came in second in the past three presidential elections, losing by a small margin each time. Today, her party is the best-organized political machine in the country, says Mr. Zavaleta. And the fact that Mr. Fujimori died at home, instead of in prison, was a reminder of that.

Mr. Fujimori served just 16 years of his 25-year prison sentence, thanks to a pardon granted in 2017 by former President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski to appease a faction of Fujimorista lawmakers who helped him survive an impeachment vote.

Mr. Fujimori was returned to prison in 2019 after a court found the pardon violated international law. Last December, Peru’s top court, whose magistrates were appointed by Congress with key backing from Fujimorista legislators, restored the pardon in defiance of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Current President Dina Boluarte, who despite first taking office as a leftist vice president, has since allied with right-wing Fujimoristas, authorized his release.

Political analysts say the pomp of Mr. Fujimori’s wake and funeral would have been unthinkable under previous administrations.

“The points on which there was agreement, that Fujimorismo was responsible for nefarious crimes ... are being challenged more and more,” says Mr. Banda. Peruvians who were once divided by their attitudes to the controversial former president, he says, are “like two countries that broke ties but now send ambassadors to each other and are courting one other.”

Essay

A bittersweet farewell: I’m a New Yorker, but Mississippi has my heart

How can we create a kinder world? Start on your front porch, as our writer does. Meet your neighbors, and learn their stories. Community breeds compassion.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

It took moving out for me to finally get to know my neighbors.

I was selling my belongings before heading back home to New York. Sitting on a roofed porch with a tea and a fan, I waited for customers. Maybe I’d glean some last bits of wisdom from a spot I’d soon put in the rear view.

First came a couple in a truck with an off-kilter carburetor. Their home had been destroyed in the recent tornadoes in the South Delta. I helped them load my futon and ice-maker. Next came a young dad in a big SUV. When he opened his trunk to load my headboard, colorful balls toppled onto the country road like plastic bubbles. An expectant mother whose car had gone kaput came for Styx, my beloved silver Corolla.

Families, both young and old, went down that same dirt road with stuff that ceased to be mine. But they gave me something valuable in return – their stories. I was happy to have played a small part in their own, adding a few more faces to this chapter of my life.

A bittersweet farewell: I’m a New Yorker, but Mississippi has my heart

It took moving out for me to finally get to know my neighbors. It was the beginning of a long hot summer in the Mississippi Delta, and I was selling my belongings before heading back home to New York. Much of my furniture was already lined up on the porch. I waited outside in a folding chair with a cash box in my lap and my phone opened to Facebook Marketplace.

Earlier that day, I had found a home for my toaster and microwave. A café owner whom I finally got a chance to engage in long conversation with gladly took them off my hands for a discounted rate. She moved here from a city, too, she confessed. But she settled down with a mutt and met a man, building a radically different life. I always pegged her for a local in hunting gear and boots. But she was just like me.

Now, sitting on a roofed porch with a tea and a fan, I waited for more customers. Maybe I’d glean some last bits of wisdom from a spot I’d soon put in the rear view.

A direct message online came before the sound of the truck, its carburetor sluggish and off-kilter. I got up to greet the couple coming to fetch my futon and ice-maker. The tailgate was loaded up with plenty of furniture already, some of it worn and taped up. I anticipated a haggle. I also anticipated trouble after struggling to pin down an ETA with the couple all morning.

I was frustrated. They were supposed to pick up the items yesterday. There were plenty of bad-faith actors on the site trying to take advantage of sellers. So by the time they finally parked and the older man helped his wife from the passenger seat, I was scowling.

“We’re coming far. Sorry about it. From Rolling Fork,” the wife said. The two of them had clear, bright eyes in spite of their tired faces.

She strode forward in jean shorts and a rock T-shirt, a “Delta strong” pin clipped to the front. The pair’s home had been destroyed in the recent tornadoes in the South Delta. I let go of my reservations and helped out the pair with the sofa, sliding it into the back of their truck with a smile.

“How are y’all holding up?” I asked after the ice-maker had been placed behind the driver’s seat.

They had been together for nearly 30 years. Their wedding photographs and his football trophies were lost in the rubble. The wife told me about an outlook down by the river where they used to picnic on dates. He shared with me a restaurant that his sister still manages in the nearby town. At least they still had those places. And “all this,” she said smiling, gesturing to the big sky that superimposes itself on the flat Delta land like a lesser deity.

After I collected the cash, I waved goodbye as they pulled out of my driveway. I wished I could offer something in the way of a recommendation. I didn’t have the nerve to tell them where I was heading. That I was giving up on this way of life for the big city. At least my old treasures would stick around even if I wasn’t – pieces of me left behind.

Next, a young guy in a big SUV pulled up. His kid’s toys toppled out of the back when the trunk door lifted. He was here for my headboard. Colorful balls continued to fall like plastic bubbles onto the country road. I rushed to pick them up and greet the new dad.

“Wife and I are looking for a bigger place,” he said as if to explain the mess.

“Have you tried here? I don’t think anyone’s moving in to mine right now,” I replied.

I gave him my landlord’s number. He smiled and checked the back seat on instinct before pulling away. I was happy I could help. With each sale, I was finding another missed connection, another reason to stick around.

Next would be the hardest goodbye: my car. Styx had taken me over levees, across county and state lines, and in one case, through a monsoon. Its new owner was an expectant mother in need of more stable transportation after her last vehicle went kaput. It was a bittersweet moment to see Styx off.

“I work over at M.S. Palmer High. They have a farmers market, you know,” she said as I handed over the keys and registration.

I let her know I’d stop by before I left town. Her husband shook my hand and I walked toward my rental: a pickup. They pulled away in Styx, and I watched my silver Corolla chase a familiar sunset down through the cotton field with a new set of hands adjusting the gears.

Families, both young and old, went down that same dirt road with stuff that ceased to be mine. But they gave me something valuable in return – their stories. I was happy to have played a small part in their own, adding a few more faces to this chapter of my life.

That a nondescript futon could help a couple stranded after a disastrous tornado, or a safe ride could ease the burden of a young couple on the brink of starting a family, felt a greater gift than the cash I received in return.

In my rental, I put in the directions for the lookout point, but not before I checked out the nearby restaurant in town, calling to make sure they knew who sent me. Before I boarded my flight the next day, I made sure to check out the school farmers market, too. My house may have been emptied, but my last day’s itinerary was full.

With a heart warmed by the parting gift of my neighbors, I pledged to bring a bit of that community feel up North to my new neighbors.

I don’t want to wait till my next move to get to know them.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Reviving the spirit of giving

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The celestial start of autumn on Sept. 22 may remind Americans to prepare for the major end-of-year holidays tied to giving: Halloween (giving treats to costumed children), Thanksgiving (giving gratitude over shared meals), and Christmas (giving gifts to reflect unselfed love). Surprisingly, these annual expressions of affection are not counted in formal tallies of generosity.

Yet that accounting flaw might change with a broad-based report from leaders in the philanthropy sector. The report mainly focuses on the reasons fewer people are donating time or money to traditional nonprofits. Yet it does acknowledge that generosity has “found other venues and taken other forms.” And it suggests that “newly expanding forms of spirituality” are revealing “other expressions of generosity.”

Nearly 3 out of 4 Americans self-identify as “generous.” And measures of spirituality are growing, the report states. A 2023 survey found that 70% of U.S. adults “think of themselves as spiritual people or say spirituality is very important in their lives.” Other recent research ties spiritual thinking directly to charitable giving.

The report recommends that spiritual leaders along with other public figures speak “openly and proudly about how they seek to ‘give back.’”

Reviving the spirit of giving

The celestial start of autumn on Sept. 22 may remind Americans to prepare for the major end-of-year holidays tied to giving: Halloween (giving treats to costumed children), Thanksgiving (giving gratitude over shared meals), and Christmas (giving gifts to reflect unselfed love). Surprisingly, these annual expressions of affection are not counted in formal tallies of generosity. Holiday giving is, well, a given. And too vast to total up.

Yet that accounting flaw might change with a broad-based report released Sept. 17 from leaders in the philanthropy sector. The report from the 17-member Generosity Commission mainly focuses on the reasons fewer people are donating time or money to traditional nonprofits. (Think the “bowling alone” phenomenon, red-blue discord, and the Great Recession.) Yet it does acknowledge that generosity has “found other venues and taken other forms.”

For starters, “The introduction of online fundraising and payment platforms expanded the practice and introduced generous individuals to an ever-wider swath of giving opportunities.” And younger people prefer giving directly to individuals rather than to institutions.

Yet that is not the only shift. The report suggests that “newly expanding forms of spirituality” are revealing “other expressions of generosity.”

Nearly 3 out of 4 Americans self-identify as “generous.” And measures of spirituality are growing, the report states. A 2023 survey by Pew Research Center, for example, found that 70% of U.S. adults “think of themselves as spiritual people or say spirituality is very important in their lives.” Other recent research ties spiritual thinking directly to charitable giving.

The report recommends that spiritual leaders along with other public figures speak “openly and proudly about how they seek to ‘give back.’” Perhaps most Americans are already ahead of them.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Shepherd, wash them clean’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Roberta Brooke

As we watch for God’s goodness in our neighbors and ourselves, we experience more peace in our interactions.

‘Shepherd, wash them clean’

Today there is an ever-growing need for us to be more loving toward one another. In public platforms, divisive rhetoric and false accusations are pervasive. In personal lives we see many relationships on edge. What will it take for us to learn to be more loving? The last verse of Mary Baker Eddy’s poem “‘Feed my Sheep’” offers a clue:

So, when day grows dark and cold,

Tear or triumph harms,

Lead Thy lambkins to the fold,

Take them in Thine arms;

Feed the hungry, heal the heart,

Till the morning’s beam;

White as wool, ere they depart,

Shepherd, wash them clean.

(“Poems,” p. 14)

What is it that washes away anger and hatred? When we are willing to set aside pride and self-righteousness and humbly seek God’s guidance, the true nature of God and His expression, man, is revealed in our hearts.

It might seem impossible to love in the face of hatred. It’s common to believe that to love someone is to enjoy being around them. But in calling us to love one another, was Jesus asking us to love a mortal personality, including one that is hateful and offensive?

The writings of Mrs. Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, bring out the distinction between human personality and the spiritual nature we each have as man, the image and likeness of God. Her main work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” states, “Personality is not the individuality of man,” “Man is idea, the image, of Love; he is not physique,” and, “Divine Love is infinite. Therefore all that really exists is in and of God, and manifests His love” (pp. 491, 475, 340).

Jesus’ example teaches us how to be more loving: by applying these truths in our daily lives and beholding God’s man or idea right where the mortal view sees only imperfection. It is this correct view of man as God’s expression that brings healing and enables us to love our neighbor.

At one point in my career, I was challenged by what I perceived as a colleague’s offensive personality. It seemed intolerable to continue working with this person. I found employment elsewhere, but no sooner had I settled into the new job than I was confronted with yet another offensive personality.

I began to realize that I needed to look more deeply into this issue from the Christianly metaphysical basis of divine Science. As I started to examine my own thought, I saw that I had been carrying around a view of man as mortal and material. By holding this mortal view, I was accepting the jarring testimony as real. Correcting this was my responsibility, not the other person’s.

I saw that when we take offense, we are acting from a material sense of things, which can foster pride, self-will, and egotism. We are viewing as mortal not only others but ourselves as well. This mistaken view is an imposition on our thinking, and that is where we must deal with it. This takes humility – a willingness to lay down a false sense of ourselves and others.

Holding ourselves to the higher standard of Christ, God’s spiritual ideal, we can affirm our oneness with our Maker, God. We can know that our true selfhood is fully spiritual and therefore impervious to material thinking, which has no source, no author, and thus no manifestation.

With a newfound willingness to be humble, I began looking for any positive traits others were expressing, such as an artistic flair, persistence, insight, loyalty, or kindness. Even if I found just one such attribute, I dwelt on it, knowing such qualities are not sourced in matter but are instead evidence of divine Spirit, God. Soon I began to see the Christ, rather than a mortal personality, in my neighbor.

Because God is All, there is nothing outside of Him. Nothing can taint God’s perfect expression, immortal man. In this light we can see all as God-expressing individuals, upright and pure. By doing so, we have let Love wash them clean in our thought.

As I did this, I began to feel the heavenly peace of divine Love with me everywhere. I no longer felt the need to escape from other people, but could love them and be undisturbed by off-putting behavior. I have even seen unpleasant behaviors diminish as I have applied these truths.

Whether in the home, church, business, or life in general, seeing others as God sees them is freeing – for us as well as others.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Nov. 30, 2023.

Viewfinder

Partial disappearing act

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for Ned Temko’s weekly Patterns column, which will look at how three European countries that used to criticize neighbors for their tough stances toward asylum-seekers are now starting to adopt them.

We also have a bonus read for you today: an explainer on elections in Kashmir, where India is allowing some democratic practices to return after years of control from Delhi. What has changed in the decade since elections were last held?